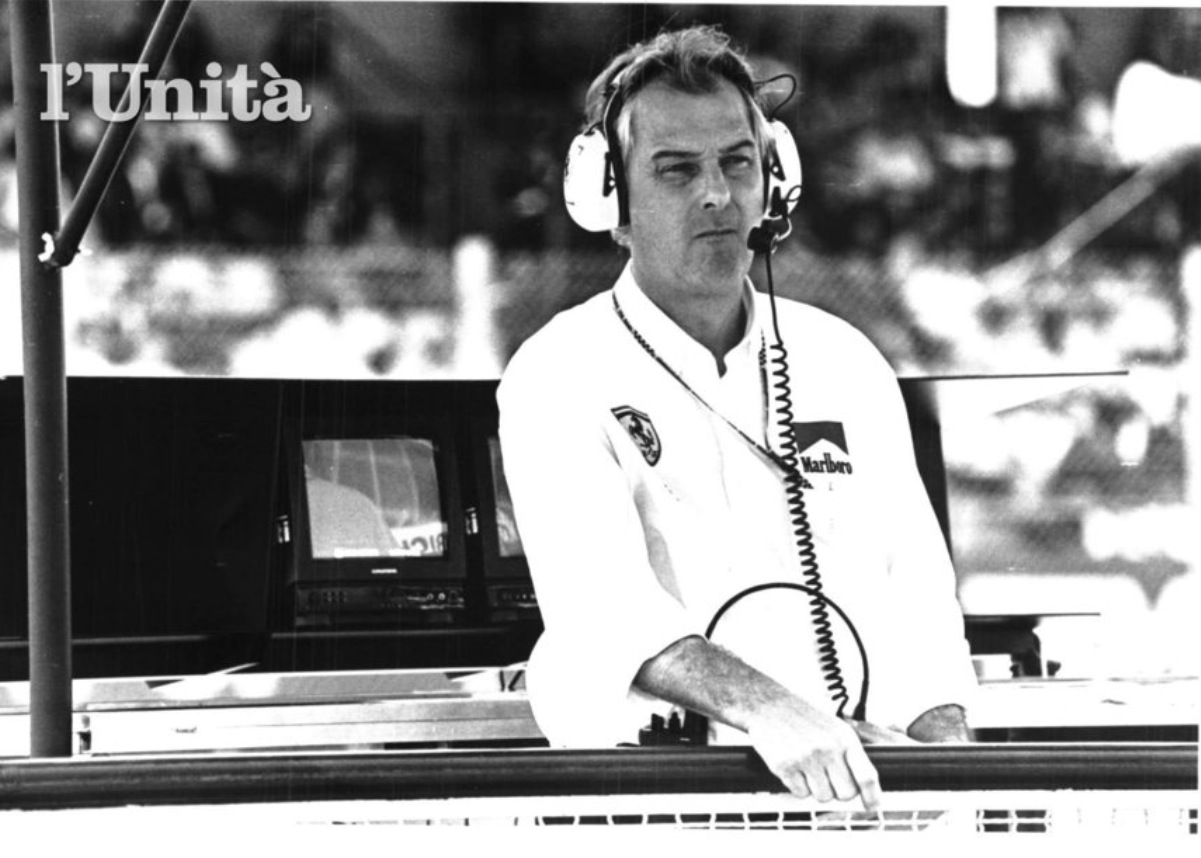

Remembering Harvey Postlethwaite 20 years on. He was another great who has contributed to the splendor of Ferrari. The engineer of Villeneuve and Pironi, the father of the very fast 1982 Ferrari turbo, the red missile that would have won the championship hands down without the accidents of its two pilots. Brilliant and visionary Harvey, intolerant of the horrendous Ferrari bureaucracy, was able on his own to relaunch entire teams even with very small budgets. And he would have continued to do so for a long time if his heart had not stopped prematurely. Now perhaps he can speak directly with Gilles and Didier, without unnecessary unproductive meetings with dozens of people. The magnificent Ferraris of his time will lead us to keep on recalling him.

He was a British engineer and one of the most respected technical director of several F1 teams during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. In terms of F1 car designers, few have managed to become absolute giants of their field. Contemporary men like Adrian Newey & Ross Brawn may be household names at this point but, twenty years ago, Harvey Postlethwaite (4 March 1944 – 15 April 1999) enjoyed a reputation to rival theirs. After leaving the Royal Masonic School for Boys, he attended the University of Birmingham, England, to study mechanical engineering and graduated with a BSc and then a doctorate during the 1960s. He was a keen follower of motor sport, competing in a Mallock at club level for a while until he ran out of money. After graduation he joined ICI as a research scientist but, bored by this, he soon began to pursue a career as a race car engineer, joining March in 1970, then aged just 26.

|

|

He worked on the fledgling company's F2 and F3 cars but, in 1974, he became part of one of the great romantic episodes in British F1 history, the Hesketh F1 adventure. The Hesketh team was well known for an unconventional approach to F1 — Postlethwaite was himself considered 'eccentric': "The Doc's explanation of his move to Hesketh was that 'they got me drunk'." Financed solely by the extroverted Lord Hesketh, managed by "Bubbles" Horsley, the team launched the career of the late James Hunt. From being the laughing stock of the pit-lane they gained credibility, largely due to the simple and extremely effective car designed by "Doc" Posthlethwaite on a budget that never exceeded eighty thousand Pounds. Working to modify and improve the novice team's March731 chassis, Postlethwaite elevated the team into serious contention and the following year designed the team's car from scratch. 'Doc' Postlethwaite's 1974Hesketh 308 secured a number of podium positions. The following year he further developed the car's unusual rubber spring suspension and saw his creation take victory at the Dutch GP in the hands of James Hunt. This win, defeating the might of Niki Lauda and Ferrari, marked more than just the only win the team was ever to achieve, but the debut triumphs for both Hunt and Postlethwaite. There were to be many more for both but the first was always the sweetest. At the end of the year the team finished 4th in the constructors' championship and Hunt scored points in every race he finished.

By 1976 Lord Hesketh could no longer afford to run the team and sold out. Postlethwaite went with his cars to the newly founded Wolf–Williams Racing, headed by the oil magnate Walter Wolfand Frank Williams, but the results were poor and the owners soon went their separate ways. Postlethwaite remained with Wolf, designing the team's 1977 challenger, the WR1. Success was immediate with Jody Scheckter taking victory at the season's opening race. Two more wins and a number of podium results followed and Scheckter eventually finished second in the Drivers' Championship. Although Postlethwaite remained with the team until 1979, they were never to repeat their 1977 success.

|

|

|

When Walter Wolf closed the team down at the end of 1979 he transferred, along with the Wolf cars and driver Keke Rosberg, to the Fittipaldi Automotive team. He produced a new design, the F8, for the latter half of 1980 but left to join Ferrari in early 1981. At the time the Italian team were considered amongst the best engine builders in the sport, having quickly mastered the turbo technology pioneered but not perfected by Renault. What they lacked was the chassis to go with the power. Renowned for his abilities to eke out performance from small budget cars, Postlethwaite was selected personally by Enzo Ferrari to rectify this problem and, by the following year, everything was in place for success. The Ferrari, during a disastrous 1980 with the outdated 312 T5, had decided to focus everything on the turbo engine and abandon the aspirated 12-cylinder boxer which, due to its dimensions, was not compatible with the aerodynamic requirements of the ground-effect cars. After Renault led the way and, after the initial difficulties, it proved to be competitive, it was decided to bet everything on the supercharged engine. The experimentation of the car had already begun at the end of 1980: during the free practice of the Italian Grand Prix at Imola, a workshop car had made its debut. For the supercharging were initially developed both the classic turbocharger and the Comprex (denomination 126 CX), a mechanical "pressure wave" compressor by Brown Boveri which, being connected to the crankshaft, annulled the turbo- lag typical of turbo. The tests continued throughout the winter and spring before the championship but, after the first two races of the World Championship, the choice definitely fell on the more reliable turbocharger. The volumetric proved too difficult in tuning and reliability. Ferrari had designed the engine with the supercharging system included between the two cylinder banks, widened to 120°, thus accepting a slight increase in the center of gravity. This distinguished Ferrari from Renault, which had the V of 90° and the turbos that littered the sides outside the cylinder banks. The reason for the choice was to free up space in the sides to allow the air from the underbody to flow out better and maximize the ground effect. The large side bins also housed the heat exchangers for the compressed air destined for the engine. The 126 CK will therefore be the first Maranello supercharged single-seater with two turbines. The car designed by Mauro Forghieri continued to have its Achilles heel in the chassis: it was the classic aluminum tube which had caused so much to suffer in previous seasons, especially in 1980. On the 126 CK there were some modifications in the rear, as the turbo was much less bulky than the aspirate. The traditional front suspensions with the rocker upper fin that activated the internal spring, while the rear ones with a wishbone layout with adjustable arms. To complement it all, the more than tested transverse gearbox with 5 or 6 speeds. Alongside Gilles Villeneuve, to replace the demotivated Scheckter, the ambitious transalpine Didier Pironi arrived. The car demonstrated chronic problems from a chassis point of view and, beyond expectations, the 126 CK made better on medium-slow circuits, also due to the driving characteristics of its drivers, in particular Gilles Villeneuve. The Canadian managed to win two Grand Prix that remained in the collective memory, also thanks to his incredible skills: Monte Carlo, overtaking Alan Jones in the final and in Spain at Jarama, resisting for over 50 laps to the assaults of Reutemann, Laffite and Watson. Villeneuve then accomplished another major undertaking in Canada, finishing third by driving with the crumpled aileron that prevented his view and then ending without wing, all under pouring rain. The 126 CK was the last Ferrari entirely designed by Mauro Forghieri. The next model, the 126C2, will in fact be designed by Harvey Postlethwaite. When the latter arrived in Maranello, he was kindly nicknamed "Postalmarket", given the difficulty in pronouncing his surname. His employment at ICI also earned him another nickname, that of "the chemist". With the arrival of the Briton and a complete overhaul of the car in time for the 1982 season, things looked better. The turbo engine was further developed and reliability found. Harvey brought to Ferrari the then new carbon-fibre construction techniques for their monocoques, that had already become standard for most British teams and the chassis was completely redesigned, featuring Ferrari's first genuine full monocoque chassis featuring honeycomb aluminum panels for the structure. Smaller and nimbler, the 126C2 handled far better than its predecessor. Villeneuve and Didier Pironi posted record times in testing with the new car and began the season promisingly with several solid results. Then came the infamous race at San Marino, after which Villeneuve accused Pironi of having disobeyed team orders. The fallout from the race preceded Villeneuve's death in an horrific accident during qualifying at the next round in Belgium, which left Pironi as team leader. Pironi himself was nearly killed in a similar accident in Germany, putting an end to his motor racing career, but this didn't stop Ferrari from winning the constructors' championship that year. The 126C2 was further developed during the season, with new wings and bodywork tried and the engine's power boosted to 650 bhp (485 kW; 659 PS) in qualifying trim and around 600 bhp (447 kW; 608 PS) in races. An improved chassis was designed and developed mid-season, that was introduced for the French GP, which changed the rocker arm front suspension to a more streamlined pull-rod one. A thinner longitudinal gearbox was also designed and developed to replace the transverse one, to promote better undisturbed airflow from the underside of the ground-effects chassis's side-pods. Mandatory flat bottoms for the cars were introduced for 1983, reducing ground effect and the 126C3 was designed with this in mind. Postlethwaite designed an over-sized but effective rear wing which clawed back around 50% of the lost downforce, whilst further compensation came from the engineers who boosted the power of the engine even further, to around 800 bhp (597 kW; 811 PS) in qualifying and over 650 bhp for racing, generally regarded as the best power figures produced in 1983. Patrick Tambay and René Arnoux scored four wins between them and were both in contention for the world championship throughout 1983, but late unreliability cost them both. However, Ferrari took the constructors' title for the second year in a row. After 1983, Ferraris took several more wins but were unable to compete with McLaren and Williams for title victory. The 1984 season was not as good as McLaren introduced their extremely successful MP4/2 car, which was far more effective than the 126C4 and dominated the year. Although the 126C4 won only once in 1984, fittingly it was at the Belgian GP at Zolder where Villeneuve had been killed in 1982 and it was Italian Michele Alboreto driving the #27 (as Villeveuve had done) who won his first race for the team. Alboreto also scored the team's only pole position of the season at Zolder. Ferrari ultimately finished as runner up in the constructors' championship, some 86 points behind the dominant McLarens and 10 points clear of the Lotus-Renaults. The 126C series cars won 10 races, took 10 pole positions and scored 260.5 points. In 1985, Ferrari competed with the 156-85, scoring two wins with Alboreto in Germany and Canada, where the Maranello company made a double with Stefan Johansson's second place. The 156-85 was also the first Ferrari of the top series that, after 23 years, did not see the name of Mauro Forghieri among the project leaders. In fact, Forghieri had left the Maranello team in late 1984, leaving Harvey Postlethwaite and his staff the complete authorship of the new car. With this car Michele Alboreto fought for the drivers' world championship but, in the final part of the season, Ferrari introduced a new engine with more power and new internal fluid dynamics. It was a real disaster, so much so that Alboreto, then fighting for the world championship, could no longer finish a race, giving Prost the final victory. Above all, the turbines and the reliability of the Tag-Porsche engine affected the result.

Postlethwaite remained with Ferrari until 1987. With the arrival in the same year of John Barnard, Harvey was "confined" to the management of cars on track and, after differences with new technical chief, he moved to Tyrrell, where he worked for four years. He would return for a two year stint in '92-'93 but then finally gave up the unequal struggle with Ferrari bureaucracy for good. "I was beginning to find the whole thing a little too cumbersome for my taste," he admitted. "I'd had some good times with Ferrari, especially when the old man was alive, but by the end I had too many memories of sitting in planning meetings with some 40 other people, all talking, all getting nowhere." During his tenure as technical director Tyrrell's results improved noticeably, culminating in the 1990 season opener in Phoenix, where Jean Alesi was able to challenge Ayrton Senna's McLaren for victory and finished second in a Tyrrell 018. Alesi repeated the feat in the Postlethwaite's novel 019 – the first of the 'high nose' F1 cars – at Monaco. At the car's launch Postlethwaite proved the structural integrity of its unusual front 'gull wing' by standing on it. While at Tyrrell Harvey employed Mike Gascoyne, who became his assistant and protégé.

In 1991 Postlethwaite was signed as technical director of the Sauber team, that planned to enter F1 in 1993. Taking Gascoyne with him, Postlethwaite relocated to Switzerland and designed the team's first car. Despite leaving Sauber before the start of 1993, the designer's car went on to considerable success in the hands of JJ Lehto and Karl Wendlinger regularly scoring points.

Postlethwaite moved back to Tyrrell in 1994, where he remained until 1998 when the team was sold to become British American Racing.

Although, by the late 1980s and 1990s, Tyrrell was a small and largely uncompetitive team, the designer remained well respected within the sport and was hired as technical director of the abortive in-house Honda F1 project in 1999.

Although Honda had not committed to race in F1, the project produced an evaluation car, designed by Postlethwaite and built by Dallara and it was during testing of this car at the Circuit de Catalunya, Barcelona, that he suffered a fatal heart attack. The Briton complained of chest pains at the track and, after returning to his hotel, was admitted to hospital where he died. The project was subsequently discontinued, although Honda began supplying engines again from the 2000 season onwards, eventually taking over the BAR team for 2006. Harvey was married to Cherry and had two children, Ben and Amey.

Universally liked and respected, the 55 year old had spent nearly all his working life in GP racing. Many tributes stressed though his human qualities and not just his design abilities. Former team owner Lord Hesketh, for whom Postlethwaite designed the winning Hesketh 308, said: "he was a great man with a young family, some of the best years of my life were spent in his company. He had charm, sense of humour, real ability and talent and was a great lateral thinker. He took us from nowhere to being a front-running team. He was a tremendous guy. It's appalling news."

|

|

Mike Gascoyne, Jordan's chief designer, was another who was quick to pay tribute and to acknowledge the role Postlethwaite had played in his career, having worked under his direction for some seven years at Tyrrell: "Harvey was, above anything, a great friend and also a defining figure in my career and the careers of many other young engineers. His infectious enthusiasm for engineering and motor sport was an inspiration to all those who worked with him."

|

|

It was in the mid 90s that Clare Topic became personal assistant to Harvey. Working in close company with him for several years, Clare explained that her job didn’t feel like an ordinary office job, thanks to his presence: “in many ways it should have been an ordinary office job but it wasn’t. It was out of the ordinary because Harvey was such an extraordinary person. It’s true, he could be vague; there was the interesting morning when, after reviewing the diary and the post and as I was about to get up to leave, he gave me a slightly sideways look which meant that he was a little embarrassed by what he was about to say: “Clare, when I was at the Experts Advisory meeting yesterday afternoon, I think I agreed to go to Canada with Sid [Watkins] and I don’t know why. I think it’s for a conference on head injuries. Can you phone Sid and ……………………..” “Find out what it is you have agreed to do?” “Exactly!” “Other times, however, the vagueness was a complete act. After listening to him talk to one member of staff about a subject expertly for about 10 minutes, he completely reverted to vague Harvey when another member of staff from another department asked him about the same thing not 5 minutes later. Catching my amused smile, as the second person left, he stared at me with all his intense brilliance shining like lasers from his eyes and said quietly “Clare, I know you know I know, but if they know I know, they’ll want me to do it and I don’t have time.” “It’s how I most often remember him, working with him in his office. I remember the slight smile that appeared when an idea occurred to him. I remember the stare over the top of the glasses. No two days in that office were ever the same. He was actually incredibly easy to work for as he always knew what he wanted to happen, he was clear in his instructions and, if I had an opinion on the matter, he listened to what I had to say. He could sometimes be infuriating, with his ability to completely disappear. His engineering zeal to test machines to their limits was occasionally directed at the photocopier and the office shredder, leading to much frustration from other members of staff sometimes! Most of the time he was cheerful, funny and very kind. Any kind of bad mood wasn’t tolerated in that office, because there was always another race next week to look forward to.” “I think what made working with Harvey so enjoyable was that he genuinely loved his work. When we worked on documents together, it felt more like a collaboration rather than taking instructions. The work could be difficult but, as he always said, if F1 were easy everyone would be doing it. Writing this piece takes me right back to sitting at his desk, working on his computer. I can almost sense him looking over my shoulder reading the screen.” While Clare has since moved on to roles outside of F1, she said that her few short years working with the influential designer left an indelible mark on how she approached her work, including setting up her own business: “the best thing I took away from working with Harvey was that he was not only someone who inspired confidence in himself, but he inspired me with confidence in myself. He was and remains an inspiration.”

Harvey Postlethwaite was a "racer" and the product of a racing industry that is gradually changing. A man of the highest principles and integrity, he will be sorely missed on the F1 pit-lanes he has graced for over 20 years.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment