Alessandro Nannini has two great passions: cars and girls. A master in the curves, he is crazy for those of beautiful women. He was happy when the pits were full of girls.

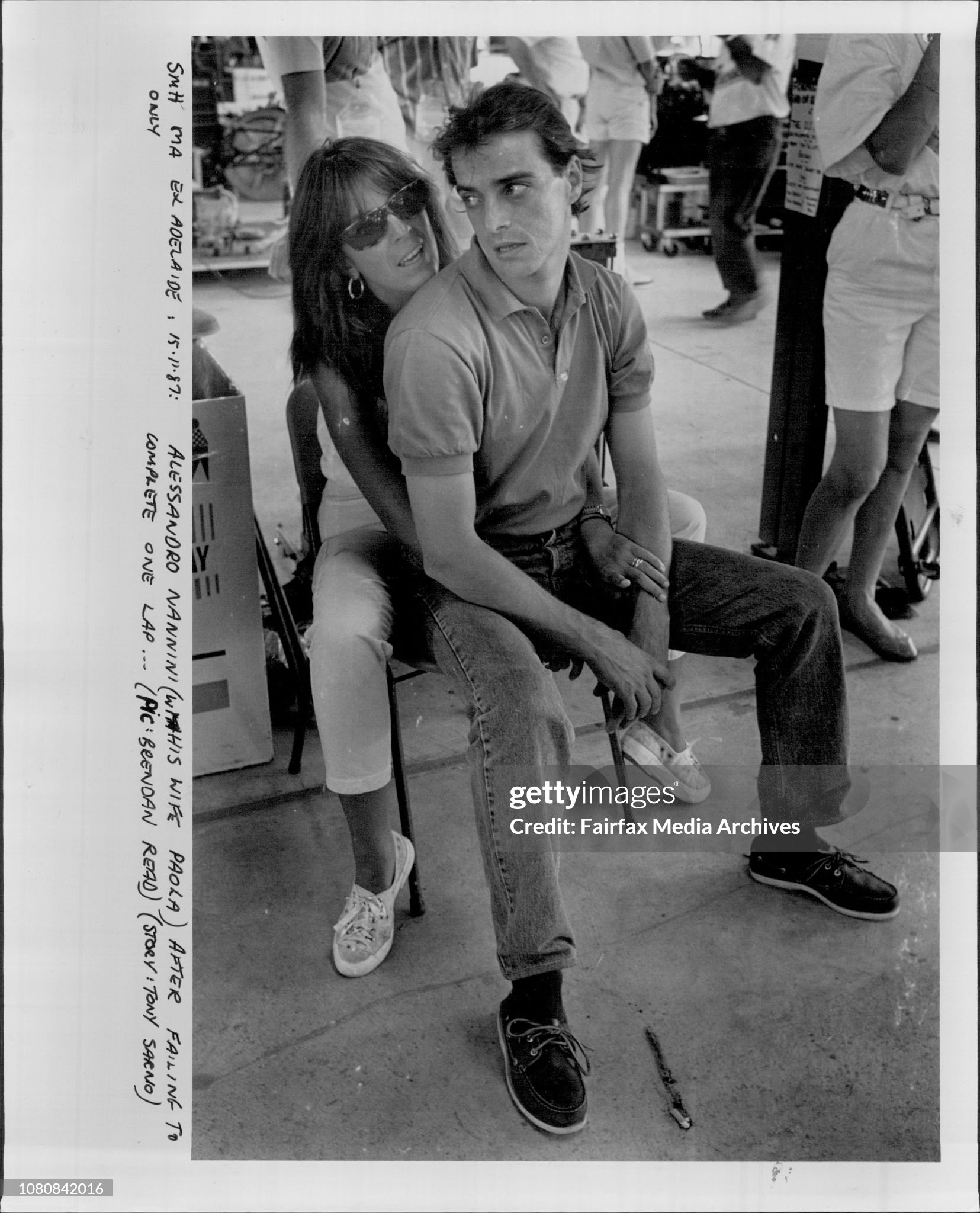

Alessandro Nannini with his wife Paola after failing to complete one lap. November 15, 1987. Photo by Brendan Read/Fairfax Media via Getty Images.

At seven he already knew how to drive, at nine he destroyed the first car, at eleven the second one and then his father seized the keys until he was fourteen. He has always liked racing in a car. In Siena they still remember when he ran around the streets of the center, terrorizing passers-by with his battered Dyane. The traffic police also knew him well. They were often forced to chase him but it was a serious business to be able to catch him.

Alessandro was a “discolaccio” (a naughty boy) and he made at least half of the Sienese girls lose their minds. Cheerful, lively, open, one of those who talk in no uncertain terms but always say everything outspoken, he had this minor weakness of cars that kept everyone worried. When Alex arrived in Formula One, behind the wheel of the Minardi, the family surrendered. His father Danilo's hope of having an heir to take care of family matters seemed definitively vanished. And instead, precisely with his first successes, Alessandro proved to be much more suited to the need in organizing family things, in inventing new activities. Slowly the dispersed family gathered again in front of the large fireplaces of the Certosa.

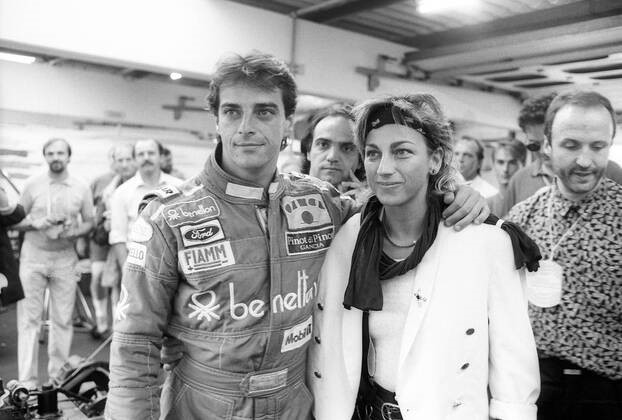

Gianna and Alessandro Nannini.

Gianna also returned more often than before, Guido has left Switzerland and Alessandro is absent only for racing. Then, the love at first sight in the family: Alessandro Nannini leaves Benetton to go to Ferrari. A week of celebrations, everyone is happy for the return of an Italian driver to the greatest team in the world. And finally a sympathetic driver, one of those who speak with their heads even before that with their mouths. Then, the cold shower. Nannini says no to Ferrari, tears off the contract they offer him and leaves. And like a great gentleman, a polite son of a good family, he renounces to make controversies, he doesn’t tell the background of this no which in any case makes him a kind of national hero.

In 1990 Italian F1 ace Alessandro Nannini loses part of his arm when his helicopter crashes on landing near his family villa in Siena (Italy). Nannini was the only one seriously injured and, even though his limb was reattached and he kept racing, the accident ended his F1 career.

And then the helicopter crash, which Alessandro remembers in this way on 2 October 2014: "I remember being scared of the accident for just three or four seconds, then it's all over; but it is also true that, when you stare death in the face, many things pass in front of you like in a flash and there you realize that you would like to live again. Apart from this, there is a question that I still ask myself regularly: how is it possible that, after almost 19 years, there are still people around who are convinced that that day it was me and not the pilot who was driving the helicopter?"

Giorgio Teruzzi says of Alessandro Nannini: “only one victory, right in Suzuka, on the day of the first Prost-Senna duel. He deserved so much more. When I meet him, now that we are "almost" elderly, I find his beautiful smile sticking out of his wrinkles, that unmistakable Tuscan accent, the old habit of teasing, of a ready wit. It's a moment, every time. Which allows you to travel through time, to return to smell the scent of a distant era, full of adrenaline and passion. Of that magnificent wind that leads to accelerate, challenging the future”.

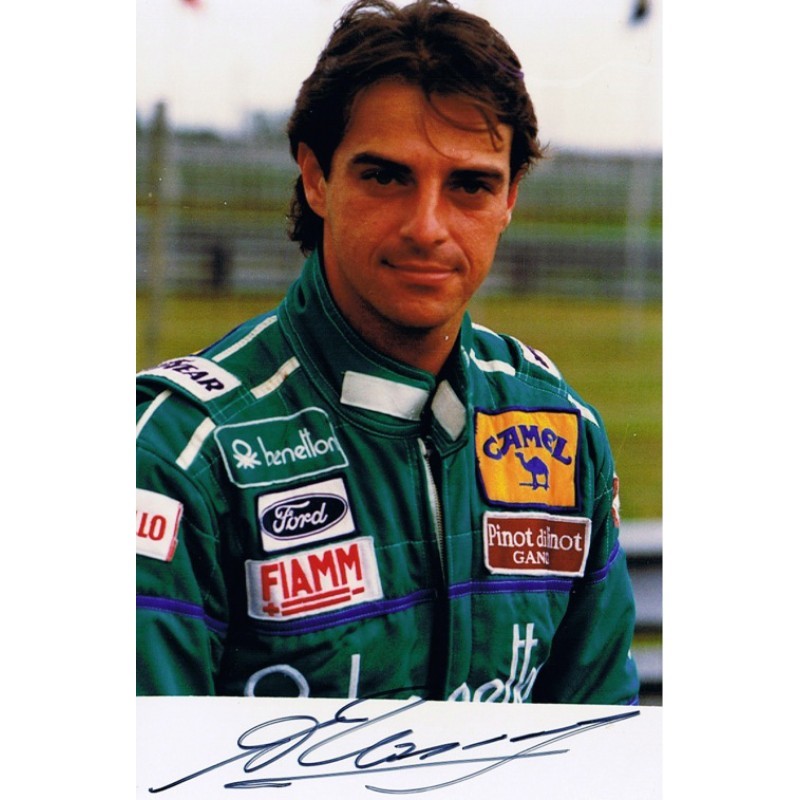

Alessandro "Sandro" Nannini, born 7 July 1959, is a former racing driver from Italy. He is the younger brother of singer Gianna Nannini. His five-year F1 career resulted in his one and only win at the 1989 Japanese Grand Prix but ended less than a year later after a helicopter crash severed his right forearm.

Nannini was born in Siena. He began racing in a Lancia Stratos at national rally events before switching to Formula Italia in 1981. From 1982 to 1984, he raced for Minardi in Formula 2, attracting some attention for his speed in the uncompetitive car.

Alessandro Nannini with Riccardo Patrese and Michele Alboreto.

Though his best season saw him only seventh overall in 1983, he was signed by Lancia to drive their fast but fragile LC2 prototype in the World Sportscar Championship, setting fastest lap at the 1984 24 Hours of Le Mans where he finished eighth with Bob Wollek and later that year winning the 1984 1000 km of Kyalami with Riccardo Patrese. For 1985, Giancarlo Minardi wanted Nannini to drive his new F1 car, but Nannini was controversially denied an FIA Super Licence with his former F2 teammate Pierluigi Martini taking the drive instead. Nannini continued with Lancia instead, his best result being third in the 1000km Monza.

For 1986, Nannini was finally granted a Super Licence and signed up with Minardi's Grand Prix team, where he stayed until 1987.

Brands Hatch, United Kingdom, British Grand Prix, Sunday, July 13, 1986. Alessandro Nannini with Carlo Chiti. Photo by Ercole Colombo.

The car was uncompetitive and unreliable (Nannini was classified only four times from 30 starts with the team), largely due to its disappointing Motori Moderni V6 engine. However, Nannini's speed was noticed by many, especially after he largely outperformed experienced teammate Andrea de Cesaris in 1986.

Alessandro Nannini, Andrea de Cesaris, Riccardo Patrese and Michele Alboreto at Suzuka, Japan, on November 01, 1987.

The Minardi M187 used by Nannini for the 1987 season.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton B188-Ford 1988. Poster by Paul Oxman.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton B188, at Monaco Grand Prix on 15 May 1988.

Alessandro Nannini, driving for Benetton, at the Japanese Grand Prix on 30 October 1988.

Benetton signed Nannini for 1988 to drive alongside Thierry Boutsen. He generally performed very well, often out-pacing the highly regarded Belgian if not matching his consistency. He scored his first point in his second race for the team and took two third places on his way to tenth overall in the championship.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton-Ford B189, Grand Prix of Hungary, Hungaroring, 13 August 1989. Alessandro’s hands in the cockpit. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images.

With Boutsen leaving for Williams Nannini was promoted to team leader at Benetton alongside young Englishman Johnny Herbert and delivered a number of strong performances, especially at Suzuka. There he lay third behind the two McLaren cars of Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost when they collided, giving Nannini the lead. Prost retired whereas Senna rejoined after being push-started and pitted to replace his front wing, trailing Nannini in the race. Alessandro was eventually passed by Senna who went on to cross the finish line first, however, the Brazilian was subsequently disqualified for missing the chicane following his collision with Prost. The disqualification handed Nannini what proved to be his only F1 win.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton-Ford, Australian GP - Adelaide, 5 November 1989.

He rounded off the season with an impressive second place in torrential rain at Adelaide, moving him to sixth overall in the championship.

Alessandro Nannini sits aboard Benetton B190 Ford HB 3.5 V8 during practice for the Canadian Grand Prix on 9th June 1990 at the Montreal Circuit Gilles Villeneuve on the Île Notre-Dame in Montreal, Canada. Photo by Pascal Rondeau/Getty Images.

For 1990, he was joined in the team by Nelson Piquet and reverted to being the number two driver.

Alessandro Nannini drives the #19 Benetton Formula Benetton B190 Ford HB 3.5 V8 during the San Marino Grand Prix on 13th May 1990 at the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari in Imola, San Marino. Photo by Pascal Rondeau/Getty Images.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton, Monaco, 24-27 May 1990.

Alessandro Nannini, Benetton, Monaco, 24-27 May 1990.

Ayrton Senna da Silva, McLaren MP4/5B - Honda RA100-E 3.5 V10 (finished 2nd), hits Alessandro Nannini, Benetton B190 - Ford HBA4 3,5 V8 (RET), at the Hungarian Grand Prix, Hungaroring, on 12 August 1990.

Alessandro Nannini on the podium at Jerez, Spanish GP, on 30 September 1990.

However, he impressed by largely matching the pace of the three-times World Champion. At Hockenheim he led the race by deciding against stopping for tyres, resisting Senna for 16 laps before fading grip dropped him to second. He also challenged at the following Hungarian Grand Prix, hounding leader Boutsen until being controversially pushed off by the following Senna.

On 12 October 1990, the week after the 1990 Spanish Grand Prix, where he had finished third, Nannini was involved in a helicopter crash over his Siena wineyard, suffering a severed right forearm. The injury healed thanks to microsurgery but it ended his F1 career. Nannini had been reconfirmed by Benetton for 1991 but Ferrari had a long-standing interest in the driver and were considering him as a replacement for the departing Nigel Mansell.

Nannini driving for Alfa Romeo at Donington Park during the 1994 Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft season.

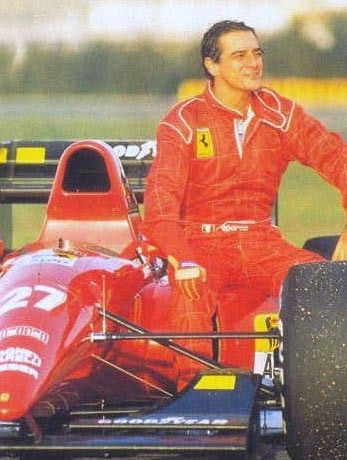

Once sufficiently recovered, Ferrari offered Nannini a test drive on its private Fiorano Circuit in 1992.

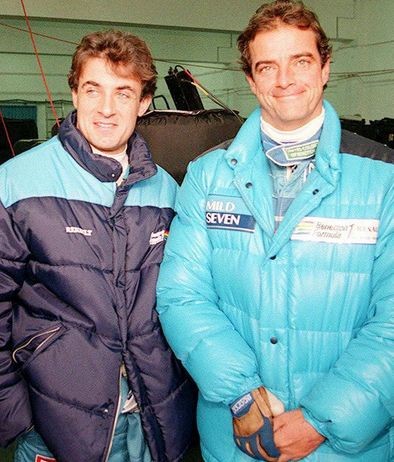

Nannini did get back behind the wheel of an F1 car again, testing the Ferrari F92A in 1992 at Fiorano, then tested the Benetton-Renault B196 at Estoril in 1996.

He completed a total of 38 laps driving Jean Alesi's Ferrari F92A, which featured a specially modified steering wheel.

Alessandro Nannini tests for his old team, Benetton, at Estoril, Portugal, on 25 November 1996. Photo by John Marsh.

In 1996, Benetton's Flavio Briatore also honoured the promise of a test drive, which took place at Estoril aboard a B196. Despite only regaining partial use of his right hand, Nannini was able to carve out a career in touring car racing with Alfa Romeo in the 1990s, placing fourth overall in the 1994 DTM championship and third in the 1996 International Touring Car Championship.

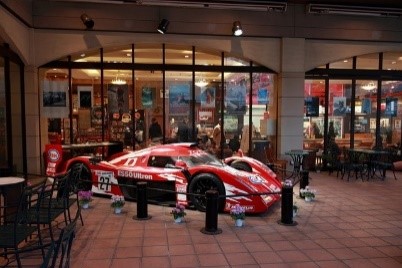

Nannini competed for Mercedes in the 1997 FIA GT Championship, finishing sixth overall and winning a race at Suzuka, before hanging up his helmet.

He now runs a chain of upmarket cafes bearing his name, with branches as far flung as Indonesia.

2007 saw Nannini's return to the track after a decade in retirement. He agreed to take part in the short-lived Grand Prix Masters championship for F1 veterans, alongside drivers including his former Benetton teammate Johnny Herbert.

He is a member of the Italy–USA Foundation.

Alessandro is married to Roberta and has three children, Isabella, Gianmaria and Andrea.

Nannini's second nephew Matteo Nannini is also a racing driver, currently racing at Formula 2 level.

Italian auto ace Nannini injured in helicopter crash. UPI Archives. October 12, 1990.

Siena, Italy - A helicopter carrying Italian auto racing driver Alessandro Nannini crashed in a field outside his parents home Friday and police said Nannini lost his right forearm in the crash.

The pilot and two friends of Nannini suffered injuries in the crash, but doctors said their condition was not serious.

The crash happened in front of Nannini's wife, parents and brother, who were watching the helicopter land in a field outside their country villa at Bellosguardo, between Florence and Siena in central Italy, shortly before 3 p.m.

Aboard the helicopter with Nannini were the pilot and two friends, Federico Federici, 31 and Giuseppe Brancadori, 27.

Brancadori told police the helicopter touched down in the field, but for some unknown reason, rose again some 65 feet and fell back to Earth.

Ambulances rushed Nannini to the main surgical hospital in Florence and the other three injured to a hospital in Siena.

Nannini's wife, Paola, traveled in the ambulance with him and his father, Danilo and brother Guido followed the ambulance to Florence in a separate car.

At the hospital doctors said Nannini's right forearm was severed just below the elbow, but otherwise he was not in bad condition.

Witnesses said Nannini remained conscious all the time. But after he was put in the hospital bed he jumped out of it again, screaming with pain.

His wife immediately tried to make arrangements to have the forearm reattached, in a move that could salvage the Italian ace's driving career.

Doctors said she telephoned Paris to try to contact French Professor Le Tournell, who successfuly reattached a severed foot of French driver Didier Pironi some years ago. The Florence doctors counseled against Nannini's being transferred to Paris immediately, but the family was considering asking the French surgeon to come to Florence.

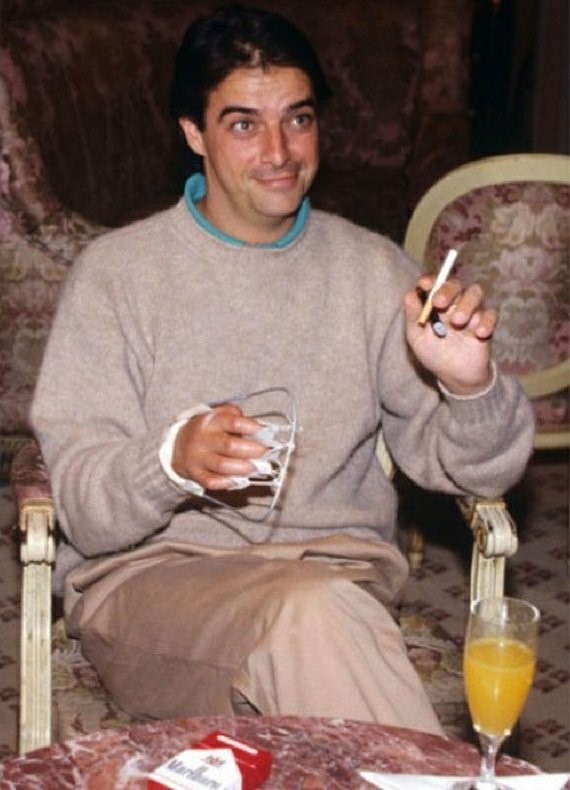

Racing toward a miracle: Italy’s Nannini making a steady recovery from helicopter crash that severed an arm. By Ken Shulman. June 21, 1991.

The hand is not totally inert, although even an untrained eye can recognize the signs of atrophy. At best, it resembles a branch that may or may not have been grafted in time, the fingers withered and slightly shrunken.

With great effort, 31-year-old Italian F1 driver Alessandro Nannini can produce a barely perceptible twitch in his fingertips. He explains that the circulation is sufficient and that the nerves are growing back at a rate of a millimeter a day. Too slow for a man used to tearing along the track at more than 160 m.p.h.

“I still can’t feel anything above the wrist,” he says, pinching at the base of his thumb to illustrate. “There’s no (sensitivity).”

It is more than six month s since Nannini’s right forearm was severed in a helicopter accident near his Siena home and seven since last year’s Grand Prix in Jerez, Spain, Nannini’s last race. Today, Nannini has come to the Benetton trailer in the paddock of the Imola track to wish his former racing team luck during the time trials for the next day’s Grand Prix. It is his first visit to a race course since the accident.

“It’s strange to be here as a visitor,” says Nannini, who finished third at Imola the past two years. “The scene is still the same, the same crowds, the same chaos. It made me happy when I heard the sound of motors revving. I heard it while we were walking up from the parking lot. With that and the smell of the exhaust and the rain, it makes me realize how much I miss all of this.”

Alessandro Nannini was not Italy’s most successful driver, but he was and remains the country’s favorite. He is the youngest of three children in a widely known Siena family.

Alessandro with his sister Gianna.

Nannini’s father runs the family’s industrial bakery best known for its traditional Siennese panforte dessert and his older sister, Gianna, is the popular rock star who sang the “Un’estate italiana” theme song for last summer’s Italia ’90 Soccer World Cup.

Alessandro made his Formula One debut in 1986 with the Minardi team, after having raced go-karts, motorcycles and rally cars. On the track, he won hearts with his all-out, fearless style. In person, he earned respect for his honesty and his well-honed Tuscan wit.

“What was I thinking?” he said after the 1989 trials at Hockenheim, Germany, miraculously unscathed after he and his Benetton car had flown off the course, spun through the air and crashed into a guardrail.

“Once I realized that I’d left the ground, I said to myself, ‘well, you’ve got to come down sometime.’ I didn’t recall hearing that they’d annulled the law of gravity.”

Last October 12, on its maiden voyage from Florence’s Peretola airport, Alessandro’s brand-new French ‘Ecureuil’ helicopter crashed in a field a few hundred yards from the Nannini family’s Belriguardo villa. Nannini had wanted to show his “new toy” to his parents before leaving for Tokyo, where he had won his first Grand Prix race the previous year.

A farmer working in a nearby vineyard said that the aircraft touched down, shot back up 25 yards into the air, then plummeted to the ground. As were the pilot and his two friends on board, Nannini was hurled out of the cabin. During his fall, the helicopter’s rotor blade cut off his right arm just below the elbow.

Nannini’s family arrived on the scene at 2:30 p.m., a few minutes after the crash. They found him still conscious, screaming: “the arm! The arm! Give me back my arm!”

Alessandro’s wife, Paola, fainted. His father, who also had raced cars in his youth, tied his belt around Alessandro’s arm to stop the bleeding, then searched for and found his son’s severed arm among the wreckage.

With his forearm packed in a refrigerated aluminum container, Italy’s most popular race driver was taken by ambulance to the Tuscan Trauma Center in Florence. The waiting room and lobby were packed with friends, family and journalists. A throng of fans crowded outside in the parking lot. At 6 p.m., Nannini went into surgery. He came out at 4 in the morning.

The accident and tragedy echoed far beyond the Formula One circuit. Italians who had never followed the sport were moved by the story and sight of the Nannini family pulling together to confront their tragedy. While Alessandro’s parents, brother and close friends paced in the waiting room--their anxious vigil lasted nearly 48 hours--the country suffered along with them.

In the recovery room, Alessandro slipped into and out of consciousness.

“I won’t race again,” a nurse heard him murmur. “I’ll go on vacation.”

The day after the accident, Nannini’s sister Gianna arrived from Berlin, interrupting a European tour. For once out of patience, she shoved past the hundreds of teen-age fans mobbing the hospital entrance. Alessandro is her favorite brother and her only thought was to reach him.

“Knock it off,” she told him, when he started to moan about the pain. “It happened to me as well. Remember when I lost two fingers in the dough kneader? It hurts for a while. And then it goes away.”

The day after the accident, Carlo Bufalini, the surgeon who had operated on Nannini, offered his first prognosis.

“It was a more difficult operation than we’d anticipated,” he said, explaining how his surgery team had painstakingly reattached Nannini’s arm, in some areas reconstructing the driver’s torn muscles, blood vessels and nerves.

“Unfortunately, it was not a clean cut,” the doctor said. “The arm was literally ripped apart. There was a lot of reconstruction to do. Alessandro is out of danger. He can go back to being a normal young man and do all the things that normal young men do. I think it will be very hard for him to return to the Formula One. It will be enough if he can drive a passenger car.”

Here at Imola, with his wife at the wheel, it takes Alessandro nearly an hour to drive through the traffic that separates their hotel from the race track, a distance of a little more than a mile.

It takes him nearly as long to walk the 150 yards from the VIP parking lot to the Benetton trailer in the paddock. Everyone wants to say hello. Everyone wants to pat him on the back. Every three steps, someone stops him to embrace him.

He wears a synthetic lambskin mitt to protect the injured hand from the unusually cold rain.

“All these people,” he says, grinning. “It’s not like I won the world championship or something.”

At the Benetton trailer, he finds Nelson Piquet, his former teammate and Roberto Moreno, the Brazilian driver who has replaced him this year. He has to be coaxed to visit the team in the pits.

“I didn’t want to be in the way,” he says. “During the trials and during the race, it’s best to leave the drivers and the mechanics alone. They’ve got enough to do.”

Nannini has had two more operations since the emergency surgery in October. He spends two weeks each month outside of Vienna, undergoing physical therapy with Willy Dungl, the Austrian “wizard” who helped former Formula One world champion Niki Lauda return to racing after he was critically burned in a crash in 1976.

Alessandro’s other time is divided between his family and his public relations job with Ford Motor Co. A series of television commercials Nannini filmed for Ford last year, before the accident, have returned to the airwaves.

“They asked me if I had any objections,” he says. “I thought it was a little strange. But I guess they realize that, for the moment, I’m even more marketable now than I was before the accident.”

His face is pale and lined, a face that tragedy has aged well beyond its 31 years. Speaking softly, Nannini tells how Ford is building a special car for him, with automatic transmission, with a spinner knob on the steering wheel and with all other controls on the left side. He confesses that he has even driven a passenger car, on occasion, at night outside his home.

“At least I won’t need for Paola to drive me every time I want to go somewhere,” he says. “But there’s a big difference between driving a passenger car and driving a Formula One race car.”

A crowd has formed outside the trailer. Standing beneath a steady rain, people jostle to catch a glimpse of Nannini. Inside, scores of photographers elbow for shooting room. Everywhere he goes, the questions are the same. “How’s the hand? When will you come back to race? September? October?”

“I never said I’d be back at any specific time,” he says, his smile fading as he slips the injured hand back into the white mitt. “I said that I’d try to come back”.

“The muscles in my forearm have just come alive. For the muscles in my hand, it could take two weeks, or it could take six months. In a few months, my doctors will be able to tell me whether it’s possible. But don’t forget, we’re talking about a miracle here.”

He rises to go. The Benetton team has asked him to watch tomorrow’s race from the pits. Italy’s state-owned RAI-TV has invited him to do color during its telecast. But Alessandro declines, saying that he would prefer to watch the race on television in his hotel, or in his home. He doesn’t want to be a hanger-on. He doesn’t want to live on past laurels. He doesn’t want sympathy.

“Of course I’d like to drive again,” he confesses on leaving. “I’d like to compete for the world championship. But just being here, being able to face the best and the worst, is a victory. In a way, I won my own world championship in the months after the accident.”

Siena, Italy, Italian F1 driver Alessandro Nannini underwent a 10-hour operation Saturday to reattach his right forearm severed in a helicopter crash. Doctors described the surgery as "technically successful" but cautioned that it was too early to say whether Nannini would regain use of the arm. Published Oct. 18, 2005

Nannini, who also fractured his left hand, was listed in guarded condition at the CTO Hospital of Careggio.

The chief surgeon, Carlo Bufalini, said it will take a week to determine whether the procedure was a success.

Even if the reattachment proves successful, Nannini will not regain full use of his right hand, the doctor said. The prospects for his return to racing will not be known until after at least a year of rehabilitation, Bufalini said.

Alessandro Nannini. Interview conducted by Richard Jenkins at the GPM event at Silverstone on the 13th August 2006. Thanks to Alessandro Nannini for his time and fluency in English.

RJ: Sandro, you’ve been away from racing for a while now.

Nannini, left, shares a joke with Riccardo Patrese. Spanish GP, Jerez, Spain, 1 October 1989.

AN: it’s great to be here, see all the drivers, back like in the old days and be with Riccardo (Patrese). I have been round with him and others this weekend as a guest. I’m enjoying myself. Seeing the guys I used to race with – and beat (broad grin), it’s very nice – I haven’t had the chance to do this kind of thing lately. I’ve got a lot of work and in Italy, as well, so work has been busy, but now, not so much, so maybe I will be able to go to these things more.

RJ: Can I ask you about your touring car career and your career after Formula 1?

AN: yeah, sure, I was with Alfa Romeo and then I stopped in 1997. That was the last year I did racing. I liked it very much and, after that, I looked at other things. After the helicopter (crash in 1990, when Nannini’s arm was severed), I was out for a long time and forgot about racing and, in any case, I had a lot of problems with how I could race. But the right people came along, they put me in a car, with a gearbox – a special gearbox, I mean, for the hand controls, for steering and I found I was still as competitive as before, so I returned to racing. But then, I have family, I have children and now work, so I decided not to continue in racing from there on.

RJ: Finally, going on to your business interests now – your cafes and vineyards are doing fantastically well – you’ve broken into the Far Eastern market – any plans for further expansion and how did you get involved in this industry?

Alessandro Nannini Café. Photo taken on September 25, 2009.

AN: yes, yes. Well, (re. expansion), I don’t know. Maybe we could be ready in a year for that, but not now. At the moment, I have time for it (the business), but we’ll see how it goes, it’s going well though. It… the family have always been interested in this and so have I. After 1990, I had time to think about things and I have a passion for it and some money, so I decided to make it work!

Former F1 driver Alessandro Nannini did not let tragic helicopter crash ruin his life. Nannini's right arm was severed by chopper blades. By Anthony Peacock. March 9, 2016.

Forget for a moment the traditional on-track stats that are used to define a race driver’s career. Former F1 driver Alessandro Nannini’s favorite statistic is one that he lives with every day.

Nannini won just one Formula One Grand Prix in his F1 career that spanned from 1986 to 1990. Many thought he was destined to be a Ferrari driver and maybe even a world champion, before fate intervened in the form of a dramatic helicopter crash that changed everything.

“I’ve seen the facts,” Nannini says. “Ninety-five percent of people involved in incidents similar to mine die. That’s why every day I wake up and I say to myself, ‘thank God! Life is beautiful!’”

He was Italy’s most promising driving talent until Oct. 12, 1990, when his helicopter pilot attempted to land in a muddy field close to Nannini’s home in Italy. The chopper came down tail first, dug into the mud and flipped onto its roof, rotors whirring. Nannini stuck his hands over his head for protection and as the canopy collapsed, his right arm was severed by the rotors.

Nannini remembers wondering how he was ever going to go sailing again—a great passion of his—and then he remembers little else, until he woke up in hospital several days later with a re-attached arm.

Alessandro Nannini in his cafe and bakery in Italy, enjoying some of his favorite things.

Today, Nannini, 56, looks after family business concerns in Siena, Tuscany. The Nannini bakery and café business was founded by his grandfather and their ornate shops are a familiar sight.

He’s still a heavy smoker (“the worst part of my rehabilitation was learning how to smoke with my left hand”) and still enjoys fine wine, food and women: everything that Italy does best.

The accident also derailed any chance that Nannini would be able to pursue a Ferrari contract for 1991.

Alessandro Nannini with Jean Alesi. Photo by Ansa.

During the negotiations between Nannini and Ferrari in 1990, Frenchman Jean Alesi was bursting onto the scene with some great drives such as the famous Phoenix Grand Prix, when he held off Ayrton Senna for most of the race. With the French market being particularly important to Ferrari, the Scuderia wanted to get Alesi into one of their cars, if possible.

Alesi’s success changed Ferrari’s plans for Nannini. The Ferrari contract floated to Nannini offered him a chance him to drive for any Ferrari-engined team (including Minardi, with which he had made his debut in 1986). It was a classic case of Ferrari hedging its bets, so Nannini tore up his contract and opted to stay at Benetton: the team that had given him his first (and only) Grand Prix win.

That win came at the controversial 1989 Japanese Grand Prix, where Alain Prost and Senna collided at the chicane in Suzuka. Following their tangle, Senna extricated himself, came into the pits for fresh rubber and then started hunting down the race leader, Nannini.

Nannini celebrates a victory on the 1989 Japanese Grand Prix podium. It would be his only F1 win. Getty Images.

There was nothing the Italian could do about Senna’s McLaren-Honda on new tires and Nannini finished second. But the race result was reversed a few hours later in Nannini’s favor when the stewards disqualified Senna for having received assistance to get back on track.

That’s not the way he wanted to win it.

“I’m still annoyed about that now,” says Nannini. “As far as I knew, I had a big lead: nobody actually told me that Senna had changed tires and was catching me at the rate of five seconds per lap. I was deliberately lapping two or three seconds off the pace because I thought there was no threat. When I saw Senna in my mirrors, I was shocked. Had I known he was there, I could have lapped a bit quicker and kept him behind me. So I won from a disqualification unnecessarily when I could have beaten him on the track. I was much more proud of my second place in Adelaide, which was the following Grand Prix.”

That race in Australia was held in torrential rain, to the extent that there were at least two drivers who didn’t want to start, despite pressure from race organizers who were conscious of their live TV commitments. “They told us just to get in and drive because we were paid to die, as well, if necessary. Some people were shocked, but I didn’t have a problem with that,” recalls Nannini. “In fact, I agreed. I got in and drove as hard as I could. It was like something out of a movie”.

The podiums kept coming right up until his final Formula One race, the 1990 Spanish Grand Prix, where he finished third. Then came the helicopter crash a week later, about which Nannini philosophically suggests: “might just be the best thing that ever happened to me. I’ve had so many friends die in racing accidents: what if it was going to be my turn next? I prefer to think about what I have rather than what I didn’t have. Maybe I could have been world champion one day if things had worked out differently.”

Nannini did test Formula One cars again, but by then the moment had passed and he was busy in DTM — Germany’s touring car championship — helped by an Alfa 155 with a specially adapted semi-automatic gearshift.

Nannini and Alfa had a great chance of winning the DTM title in 1994. “Can you imagine what it would have been like if us spaghetti-eaters had socked it to the Germans on their home territory?” he says. “It would have been like them coming over to us and beating up the Pope.”

But it didn’t happen because Nannini was taken out of the race and the championship at the hairpin in Singen by Roland Asch. That move gave Asch’s Mercedes teammate the championship.

Nannini was livid. He took the Alfa back to the pits, took on fresh tires and pursued Asch just as Senna had pursued Nannini himself in Japan five years earlier. When he found his target, he waited until the same hairpin and then punted Asch off so hard that the Alfa burst into flames.

“I’m probably not as excitable now as I was back then,” he says, despite drinking what is probably his 15th espresso of the day. “But I still don’t give a shit about what anybody else thinks.”

Alessandro Nannini: “Formula 1? It's different now The driver is less decisive today."

The memories of the great ex put out of action by a helicopter accident. By Mauro Corno on January 18, 2019.

How would you feel in this Formula 1?

"Badly, with only one hand and with all these buttons to press” (he laughs). Talking with Alessandro Nannini is a privilege. Not only because he was a great champion of the four wheels, but for his ability to disembarass the interlocutor when touching delicate topics. His story is well known: when his career was still at a very high level and he could still have achieved many goals, a terrifying helicopter accident - it was October 12, 1990 - did not cost him his life only by miracle but caused the amputation of his right forearm. With a very delicate surgery, his limb was reimplanted but nothing was as before, despite a long and painful rehabilitation: functionality was compromised to be able to still be competitive in Formula 1, but not to try his hand at a profit in the covered wheels and bring the 'Alfa Romeo to a series of successes, also in the Dtm and therefore in the home of the Germans. Sienese, 60 years old, younger brother of the singer Gianna, after having debuted in rallies he then moved to Formula Abarth, to land in Minardi and, after a practicum in Formula 2, to make his debut in Formula 1 in 1986 with the team of Faenza. In 1988 the landing in Benetton and the first podiums, with the success in Japan in 1989. In 1990, just before returning to Suzuka and after three other podiums, the intersection with destiny.

How much has Formula 1 changed since your time?

"Very, very much. When I was racing there were maybe 100 people working for a team, now in some cases we have ten times as many of them: it is an industry in the industry, with costs that have risen in an incredible way and that have led to even more fierce competition among the top teams”.

And now, what can happen to it?

"At this moment it is not easy to understand what can happen to Formula 1: the sale by Bernie Ecclestone to the Americans of Liberty Media was an epochal operation. And now we can't even rule out an hypothesis that would have been science fiction only a few years ago: the merger with Formula Indy. From the point of view of costs, presumably, it would lead to a lowering. On the technological level, instead, I don't know. Over the past fifty years Formula 1, with the evolution of its models, has also been towing the production of "normal" cars, making them more efficient and safer."

On a human level, how are we doing?

“People like Gian Carlo Minardi are missing. I like him regardless and maybe I don't count because we are friends, but it should be noted that he has pulled many drivers up from nothing or almost nothing: the list that could be done is very long. An eye like this in discovering budding talents is no longer found. For me the years spent in his team have been wonderful, also because I was able to give everything I had to repay him for his trust”.

Let's go back to the original question?

“Agree (he laughs). “Now there is the power steering and the single-seaters are much lighter. Technology reigns supreme, when we were racing in Monte Carlo we reached the finish line with our right hand bleeding for the continuous use of the gear lever, the physical effort was terrible. Those were years in which I learned a lot and grew up as a driver. Now it is much easier to go fast, but in a race the value of the car can reach a level of up to 90%, leaving only 10% to the ability of those behind the wheel. It's not always like this, but it happens and it's really very different from when I was in Formula 1 too".

You, in Benetton, have raced for instance with a great champion like Nelson Piquet.

“It is no coincidence that he won the world title three times. And then he was really an ace in setting up the car”.

Is it a good year for Ferrari?

“It's early to tell. Two years ago it could have won with Sebastian Vettel, but from the middle of the championship onwards it was missing something and Lewis Hamilton has put together a series of consecutive wins that have made a difference. In 2018, the German from the Red team got off to a strong start but then Mercedes made a great comeback and proved to be always very performing. It will be these two teams, once again, to fight for the title. I think we will be able to get an idea from the very first outings but, before we see the cars on the track, it is really difficult to make predictions".

When will we see a Formula 1 with twelve Italian drivers at the start again?

“It is very hard to even have more than one of them. A lot of work would have to be done at the school level to nurture the talents of our home. Also, when I started, they had me working with highly experienced drivers and, to go faster than them, I had to quickly learn the tricks of the trade. Otherwise I would have stayed behind. We would also need more help from the most important Italian companies in the sector, together with a more perspective vision than the search for an immediate return”.

Speaking of returns: we will see Robert Kubica at the start again, in a Williams.

“He has always liked rallies, as have I. And he has always been very fast. But he also had a very bad accident that affected his career in Formula 1. Now, after a year as a tester, he comes back there to all effects. And I'm sure he will go very fast, because he has never lacked talent”.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment