Romain Grosjean saw the grass from the roots side in the last year of his daring Formula 1 career.

The French driver leaving Grand Prixs with a spectacular crash seemed about right, but even he couldn’t imagine an ending like this, a fatal accident without fatality.

He has had all sorts of accidents without ever sustaining physical consequences or having learned the lesson. And he didn't intend to change his attitude even in his last year in the major formula. And then fate wanted to remind him that he is a very lucky man. And that the time to drive a racing car was over. Five seconds and he couldn't have told it. Because luck cannot last forever but for him it could. Many drivers died for much less. He has to thank the Halo, which he did not want ("I wasn't for the Halo some years ago but I think it's the greatest thing we've brought to Formula One and, without it, I wouldn't be able to speak to you today,"), the engineer Dallara for the carbon cell that saved him and his quick reflexes. But this time Romain had quite an experience. And he will never forget that Sunday in Barhain.

Grosjean was engulfed for 27 seconds in the flames of his Haas with the cockpit wedged in the middle of the guard rail of Turn 3. The accident occurred on Sunday, during the Bahrain Grand Prix. The driver was saved after a collision at 220 km per hour. An escaped danger thanks to the Dallara Automobili chassis - the Haas VF-20 is built in Varano, Italy - and the Halo system. With increasingly severe crash tests, the Dallara-made chassis withstood the tremendous impact.

The survival cell requires the car to break between the engine and gearbox: the part where the driver is has much higher safety criteria. The fireproof suit must instead withstand at least 11 seconds at a temperature of 800 degrees. The Halo system, introduced in 2018 and supplied to teams by external manufacturers, is the titanium structure that protects the driver's head: it is able to withstand forces of 125 kN (equal to the weight of 12.5 tons) even lateral.

What could have been a tragedy ended in a miraculous escape when Grosjean was seen, appearing out of the flames like a Terminator, jump over the barrier and, with the help of doctors and stewards, get on an ambulance to receive medical treatment.

Romain "Houdini" Grosjean. His accident brought us back to Simoncelli's for emotion and to Williamson's for similarity.

It literally looked like an airplane accident. There was an explosion behind his back and he survived that.

If you have driven past burning cars on the freeway you could feel the heat from them from the other side, even at 70mph and the windows up, you could feel it as you zoom by.

We haven't seen a F1 crash that bad in a long time. He got a whole army of angels watching over him. He was literally in the middle of this fireball, the fact that he didn't panic, was able to find a way out of this mess when he probably couldn't see anything is incredible. You could see him moving in the burning car. Romain, you are badass.

We've never seen a driver walk away from an accident that bad, a man running for his life. His longest 30 seconds ever. Everyone truly witnessed a miracle today. He used up his 7 lives all at once right there. We don’t want to know what was going on in his head. When he left the car his body language was out of this world. He was in shock.

Some people weren't around when cars were bursting into flames like that. That's something we didn't think could really happen anymore. That was like a throwback to the old days of the 60's and 70's when so many drivers died in fiery crashes. Back then that would have been an instant death. Go and see Roger Williamson crash in 1973 after seen this, the unprepared Marshalls killed him.

Dr Roberts – who, in a practice first initiated by F1 safety guru Professor Sid Watkins, had been following the pack around on lap 1 in the Medical Car driven by van der Merwe – described the scene that had confronted him when he got to Grosjean’s stricken car at Turn 3. “The first lap, as normal following them around and just [saw] a massive flame and as we arrived, a very odd scene where you’ve got half a car pointing in the wrong direction and just across the barrier, a massive heat. I could see Romain trying to get up. We needed some way of getting to him. We’ve got the marshal there with an extinguisher and the extinguisher was just enough to push the flame away as Romain got high enough to then reach over and pull himself over the barrier.” According to van der Merwe, he and Dr Roberts rehearse theoretical medical scenarios that they may be confronted with ahead of each day of action on a race weekend. But van der Merwe, a former racing driver who took over the Medical Car job in 2009, said that what he saw in front of him in Bahrain was unlike anything he’d ever witnessed. “A lot of this is preparation, but when you get to something like this – we’ve not seen this combination before,” he said.

“I’ve not seen fire like this in my stint as a Medical Car driver, so a lot of it is new and unknown territory and we can only be as prepared as our own ideas. We do a lot of checklists and a lot of scene prep, talking about scenarios, but this was crazy. Honestly, to get there and see half of the car and the other half nowhere to be seen and a huge ball of flame, you have literally seconds, you’re thinking on your feet. So preparation only gets you so far and, after that, there’s a lot of sort of instinctive and quick thinking. I could see obviously he was very shaky and his visor was completely opaque and melted,” said Dr Roberts. “It was a matter of getting his helmet off just to check that everything else was okay. He’d got some pain in his foot and on his hands, so from that point, we knew that it was safe enough then to move him around into the car, just a little bit more protection, get some gel onto his burns and then get him into the ambulance and off to the Medical Centre. “Nothing went up into his helmet,” he added. “Looking at him clinically, we’re quite happy with him from a life-threatening injury point of view and then it was just trying to make him comfortable from the injuries that we could actually see.” Meanwhile, with Dr Roberts joking that he’d “got a good tan” from getting as close as he did to the flames, van der Merwe went on to praise his colleague for his actions in helping Grosjean get away from the fire, as well as lauding Grosjean himself. “Honestly, that was some bravery there,” he said of Dr Roberts' actions. “It is team work and, ultimately, sometimes Ian has to rely on me and vice versa and today everybody just kind of did their bit – even Romain. Romain did a huge amount. The fact that he was able to get out of that himself partway, the fact that his shoe came off and just all of these small things; one of those things changed and it could have been a very different outcome. So today, all the teamwork, all the prep, feels worthwhile. On a day like today, I am thankful to be working with Ian and to be standing on the shoulders of giants like Charlie and Sid. So happy that Romain is well. It makes all the preparation (and sitting around!) worthwhile for those 30 short seconds. Formula 1 can be proud today.”

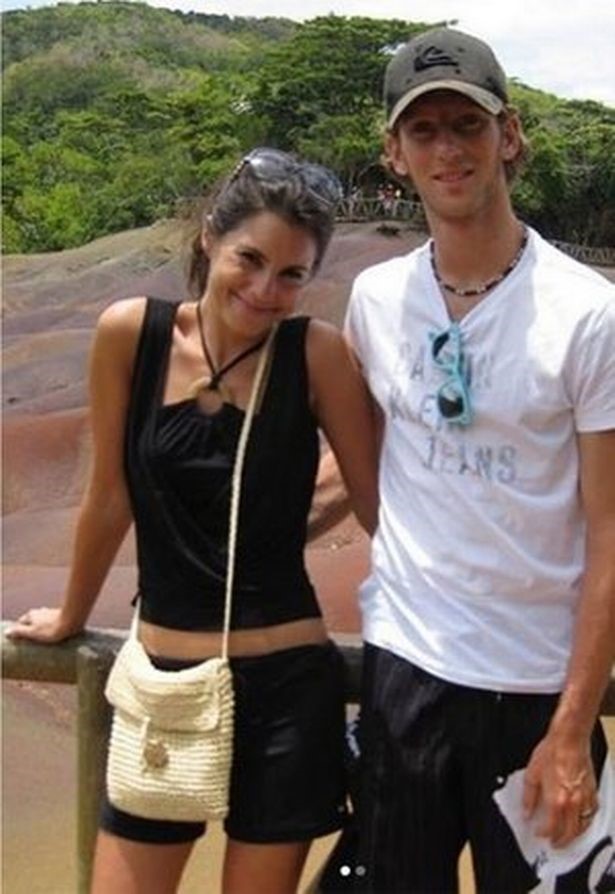

Marion Jolles, girlfriend of Romain Grosjean.

Marion and Romain Grosjean.

“Of course, I didn’t sleep last night. It didn't take one miracle but several yesterday. I embrace you all'; Marion Grosjean posts heartfelt tribute on Monday after Romain Grosjean's horrifying crash at the Bahrain GP. Marion, with whom the Haas driver has three children, watched the Sakhir race from home.

This is how Romain Grosjean survived. By Fred Smith. Nov 30, 2020.

Romain Grosjean walked away from a horrific, fiery wreck at the Bahrain Grand Prix. Here's what led to the crash and what allowed Grosjean to escape it without serious injury.

Clive Mason - Formula 1 Getty Images.

Romain Grosjean started Sunday's Bahrain Grand Prix from 19th on the grid. A poor start by second-placed Valtteri Bottas slowed the entire rest of the field, creating chaos and an opportunity for Grosjean to make up spots in a car that has struggled for outright pace for the past year. He was already making up positions heading into Turn 1 and light contact between a Ferrari and a McLaren on the exit of Turn 3 created even more opportunity. Grosjean saw the opportunity to take another position, maybe even a few, heading into Turn 4, so he dove to the inside line and prepared to out-brake the cars that had exited Turn 3 with far less momentum. This is when his right-rear corner struck the right-front corner of Daniil Kvyat's AlphaTauri entry, forcing Grosjean off track at a high speed.

On an ordinary Formula 1 track, Grosjean would have collided with a wall at a forgiving diagonal, spreading the impact out over the nose and sidepod of the car as it slid along the wall or guardrail. Bahrain's Turn 3 exit, however, is a temporary guardrail, one that juts out into the paved off-track area meant to allow drivers to recover from exactly this sort of collision. Grosjean's trajectory just so happened to put him nearly perpendicular to the wall. The nose of his car seemed to hit precisely at a seam in the three-layer guardrail, splitting the barrier open. Rather than absorbing the impact, the wall halted Grosjean's car immediately.

This is when the car split in two.

The car bisected at the point where the driver's protective carbon fiber "tub" connects to the powertrain and rear bodywork. The cockpit hit the guardrail with such force, Grosjean and the remainder of the car went clear through to the other side.

This is where the fireball erupted.

Formula 1 cars carry a full fuel load at the start of every race, a safety measure designed to eliminate in-race refueling that can lead to fires in the pit lane. While most of Grosjean's fuel seemed not to ignite, the immediate and sustained fire implies that at least some fuel seeped out and caught flame. The fireball was enormous and explosive, engulfing only the cockpit area on the infield side of the barrier, the side Grosjean was sitting in.

Seconds later, Grosjean emerged from the flames on his own. A safety team began putting out the fire and Grosjean leaped over what remained of the barrier and walked to the waiting medical team.

Romain Grosjean with Jean Todt.

He spent an overnight in a hospital in Bahrain, but preliminary scans show no broken bones. Aside from burns on the backs of his hands, Grosjean escaped the horrific crash without major injury.

Grosjean suffered the ultimate nightmare of any racing driver, a perfect storm of cascading catastrophes. Everything that could go wrong did, all at once and each component of the crash was meant to be controlled by a specific safety measure. Grosjean not only lived, he walked away from one of the most harrowing racing crashes imaginable without a single broken bone.

This is how it happened.

To understand what went right, we also need to understand what went wrong. This starts with the collision itself, a simple result of on-track jockeying for position at the cramped center of a chaotic standing start that left a car careening off the line at a high-speed section of track. All of this is relatively routine and would traditionally be countered by a flat wall or guardrail positioned to slow an out-of-control car with a glancing blow. Grosjean's car would hit such a barrier at an angle and slide along its length, dissipating energy and shedding speed. Instead, this particular wall juts outward, covering an access road made from existing runoff area. This positioning created a nearly head-on collision, the first thing to go wrong.

Grosjean struck the wall at a reported 137 mph. A three-piece steel guardrail, colloquially known by the brand-name Armco, is designed to deform on impact, absorbing momentum and keeping the car from piercing through the barrier. The guardrail that Grosjean hit ended up splitting between the first and second bars, the forceful impact of the car's nose seeming to break the bars in two. This led directly to the worst elements of the incident.

BBC Sport's Andrew Benson reported that the 137-mph impact had a force of 53 g. That energy had to go somewhere. With the driver's survival cell suddenly stopped, the impact force pounded through the car, splitting the chassis in half at the point where the cockpit connects to the drivetrain and rear of the car. This splitting off is by design — the car is built to protect the survival cell by dissipating the impact elsewhere and a violent crash can cause the drivetrain to snap off. But Grosjean's high-speed separation seems to have released fuel that was then ignited, creating a towering fireball — the third and most dramatic of the catastrophic failures that contributed to this crash.

Dan Istitene - Formula 1 Getty Images.

After the nose of the car pierced the guardrail, the next thing to hit would have been Grosjean's helmet. This was the fourth catastrophic failure of the crash and the point where we get to see up-close the life-saving power of recent safety changes.

It was just three years ago when Formula 1 mandated the introduction of the "halo" safety device that adds a secondary protective structure around the driver's helmet. Grosjean's halo made direct contact with the top portion of the barrier, a collision that should theoretically be impossible in the controlled conditions of a live race. It was not impossible, of course and the halo ended up absorbing some portion of the impact.

Grosjean likely survived the impact thanks to the halo; without it, his helmet would have been directly in the line of the impact. It meant he could escape the fire on his own, in under 30 seconds, avoiding more serious injury — and disproving some early fears that the halo would impede a driver's ability to get free of a burning wreck. Had he not been able to escape, Formula 1's professional safety team was able to get to the car almost immediately.

Fire protection gear is only effective for so long and Grosjean was able to get out of the car before coming close to those limitations. Series doctor Ian Roberts, who spoke with the Sky F1 broadcast team after the race, arrived at the crash so quickly, he was able to help Grosjean over the guardrail as crews were still putting the fire out. Formula 1's professional rescue team, like the IndyCar team that saved James Hinchcliffe's life in 2015, is a fully-dedicated group, led by Roberts since 2013, with extensive training in extracting, diagnosing and treating drivers immediately at the scene of a crash. The rescue team's performance at Bahrain was a shining bright spot in this incident, with the safety car arriving mere seconds after Grosjean's car came to a halt. Thankfully, their role was minimal, but had things gone differently — had Grosjean been knocked unconscious in the crash, or had his tub been trapped within the mangled guardrail instead of piercing through — the rescue team would have been tasked with a difficult extraction under urgent time pressure.

TOLGA BOZOGLU. Getty Images.

Make no mistake, this was not a proud day for Formula 1. Like so many harrowing wrecks, this incident was the result of a cascade of failures both catastrophic and banal. Racing safety is made up of two components: the car and the track. The Bahrain International Circuit is responsible for the design of the guardrail Grosjean hit as well as its positioning relative to the direction of travel. Formula 1 regulations dictate the height of the car's nose, which seemed to allow the n. 8 Haas to split through the guardrail, as well as the design and positioning of the fuel system, which was clearly compromised in some way when the car split apart, turning a violent crash into a fiery one. And Formula 1 approved the track and those walls — along with another, faster track layout for a race next weekend.

All of these individual decisions contributed to the scale of the crash. If the guardrail that angled toward the track had instead been designed as a reinforced barrier running away from the racing line, Grosjean might simply have had an unremarkable crash and retired from the race. If the guardrail was in its current position, but built from a more modern impact-absorbing structure — like the SAFER barriers used in the U.S. or the recently-updated TecPro barriers used in high impact points at multiple Formula 1 tracks — Grosjean might have suffered an unusually painful hit, but the car likely would not have split in two and there would likely be no impact to the halo. If the car hadn't broken in half, there likely would have been no fire. Thankfully, other safeguards were in place and Grosjean was able to survive all four of these catastrophic unexpected problems.

There was also considerable luck involved. Had this crash happened further away from the pit lane, the recovery team would have taken longer to arrive. Had the car gotten tangled in the guardrail rather than piercing all the way through, Grosjean would have struggled to free himself from the wreck. Most importantly, had Grosjean lost consciousness, this could have been a tragedy. A number of things had to go right for everyone involved to get this lucky, but none of that would have mattered without the decades of safety improvements that allowed Grosjean to survive the impact in the first place.

There are failures here that need to be investigated and changes that will need to be made quickly. The FIA will spend the next few months investigating Grosjean's crash and will eventually share its findings. Hopefully, what's learned will make Formula 1 even safer for future generations of drivers and participants. Until then, all we can do is be thankful that auto racing is at a point where so many of these safety features have been implemented already. These findings should lead to real safety improvements, ones that will mean a driver won't need such improbable luck to survive so many things going wrong. Constant safety improvement has allowed Formula 1 and modern auto racing in general, to reach this point of safety. It can't stop here simply because Grosjean walked away from what could have easily been a fatal crash. His survival is nothing short of miraculous and it would have been impossible if Formula 1 ever gave up on getting safer.

Speaking to French broadcaster TF1 a few hours after being discharged from the Manama Military Hospital, Grosjean said a lot of things raced through his mind whilst sitting in the wreckage. He described his experiences in the immediate aftermath of the crash, as he was in the cockpit of the burning car, which had broken in two and become lodged in a barrier.

“Physically, it's fine but I've seen death too closely. You can't live it and be the same person. I don't know if the word miracle exists or if it can be used, but in any case I would say it wasn't my time [to die]," the 34-year-old said.

“The impact was not the most violent I have ever known in my career, even if the Gs indicated it”, the transalpine continued. “This was because the deceleration was 53 times my body weight. It felt much longer than 28 seconds. I saw my visor turning all orange, I saw the flames on the left side of the car. I immediately unfastened my seat belt, tried to get out of the car but I felt stuck and decided to wait. I thought about a lot of things, including Niki Lauda, that it wasn't possible to end up like that, not now. I couldn't finish my story in Formula One like that. I tried to go out again, it didn't work, I sat and saw death, not up close, too close. It was a feeling that I would not wish on anyone. I wondered where I'll start to burn, if it will hurt. And then, for my children, I told myself that I had to get out and there I found the resource to get myself out of the cockpit. I was more afraid for my family and friends, obviously my children who are my greatest source of pride and energy, than for myself in the end. I put my hands in the fire, so I clearly felt them burning on the chassis. I got out, then I felt someone pulling on the suit, so I knew I was out. When I went out I felt a great relief, I will live”, the driver recalled.

Now I follow the directions of the doctors to recover as quickly as possible. I don't have nightmares, thoughts, flashes or fear, but that doesn't mean they won't come and that's why I think there's going to be some psychological work to be done, because I really saw death coming. There is the need to get back in the car, if possible in Abu Dhabi, to finish my story with Formula One in a different way, to know what I'm capable of doing, if I still want to do it, if the passion is still there and if I'm not afraid”, he added. Grosjean described his escape from the accident as "almost like a second birth". He said: "to come out of the flames that day is something that will mark my life forever. I have a lot of people who have shown me love and it has touched me a lot and, at times, I get a bit teary-eyed."

Romain, I know what you're thinking … Yeah, accidents would be cool with that ... No, Bruce Wayne won't lend it to you ...

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment