The more you investigate and document yourself about F1 the more you discover exceptional photographs and information, realizing how immense the material about the sport is, all there, motionless forever in time and at your disposal. It transmits the teachings that the racing world gives us and which are the priceless treasure for posterity. There are no places on this planet freed from life and no defense is granted to us to escape our human destiny. However, you can avoid taking risks, extending your life and making it more comfortable.

This is not what those drivers did, they chose to live without filters facing death directly every day. They knew they couldn't live long but that didn't hurt them, they wanted more. This attitude involved very different human relationships than those of conventional people. They gave everything of themselves at all times and in all their activities. Everything was magnified, mysterious, romantic. This approach made those men magnetic, very fascinating and very fascinating was that Formula 1, daughter of that time, of a time that will never come back. And then that historical moment will remain an island that will never be reached again, just like its reckless inhabitants.

All that remains for us, who can see it through their testimonies, is the arduous task of handing down these wonderful deeds so that they are never forgotten. So that those crazy heroes of the steering wheel remain present at least in our thoughts. Then, perhaps, they won’t have died in vain.

“The history of Formula 1 is made by cars but the luck of Formula 1 depends on the champions, people, men on the verge of disaster, exposed, gifted, distant. Yet suddenly mysteriously similar to each of us." Giorgio Terruzzi

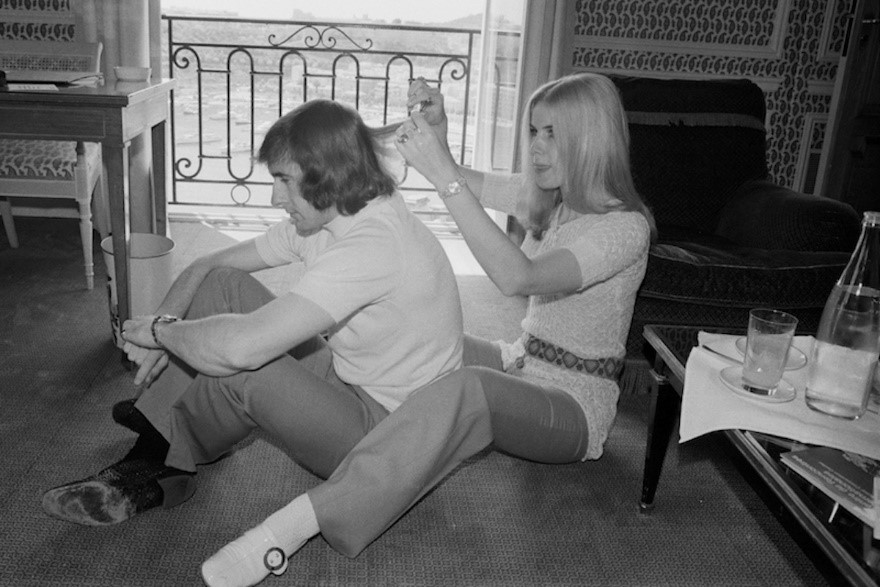

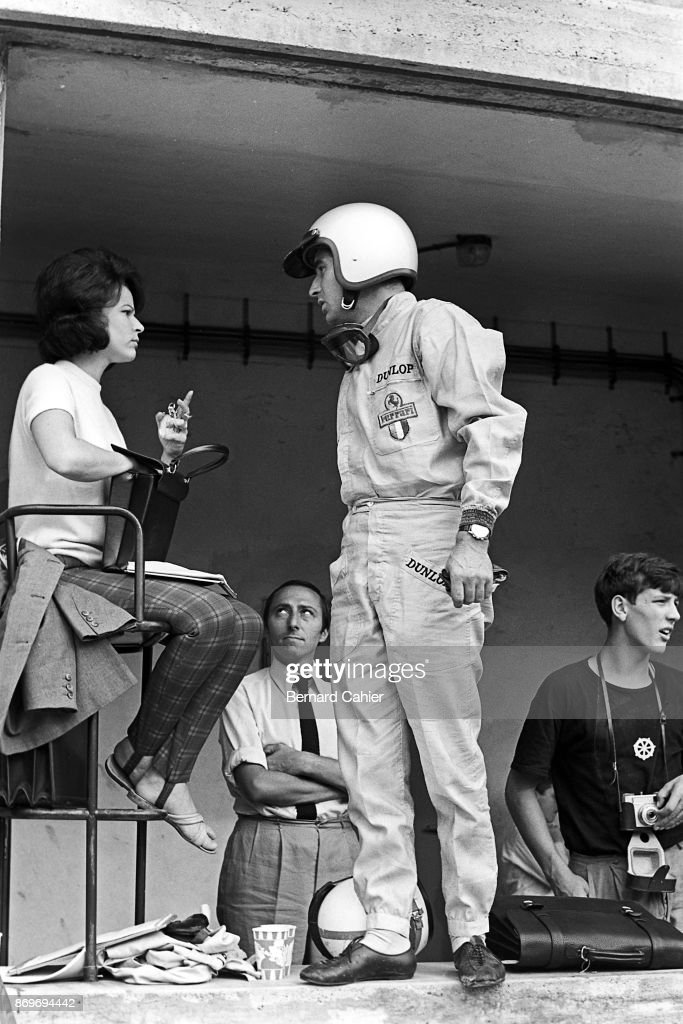

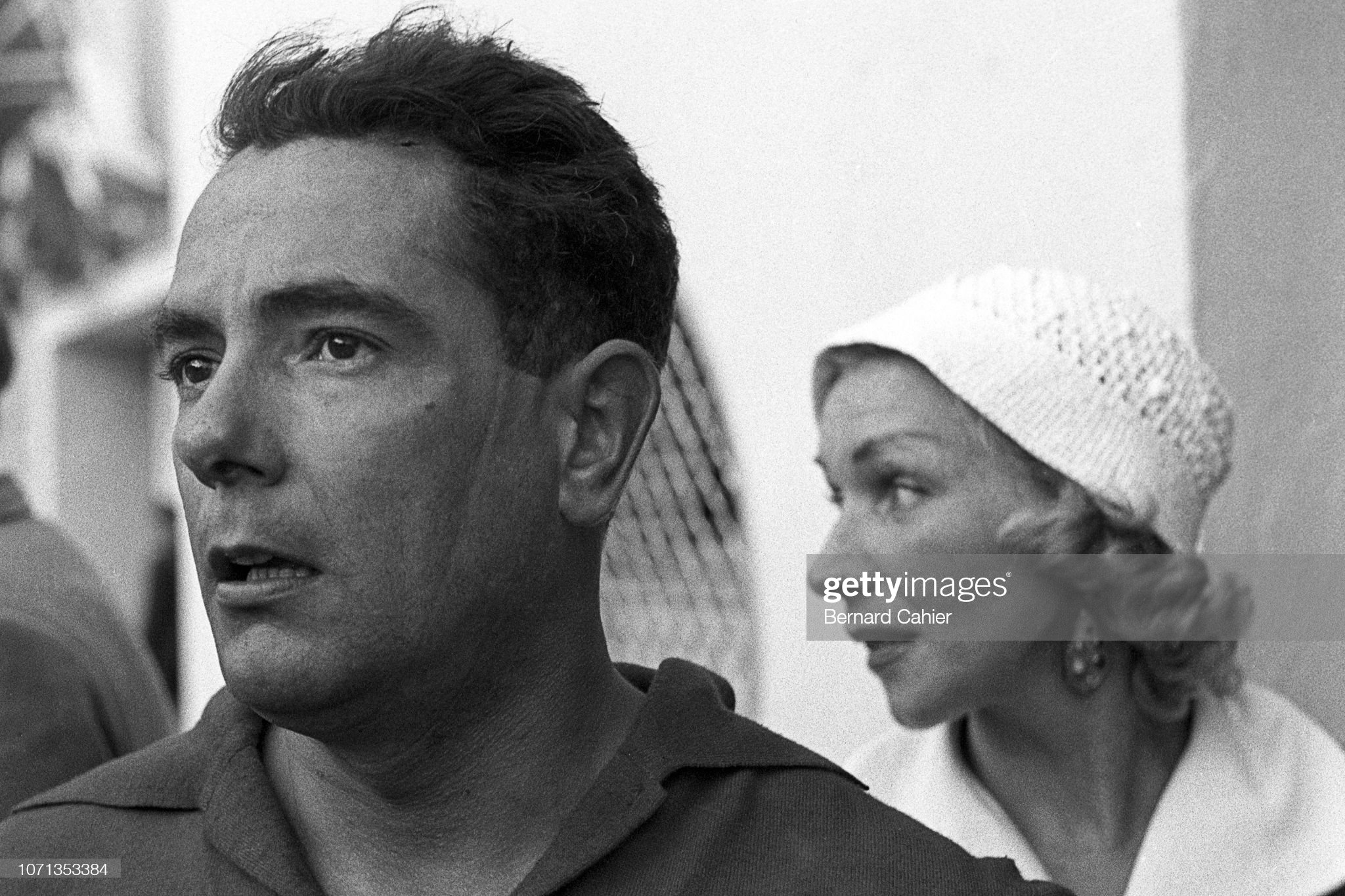

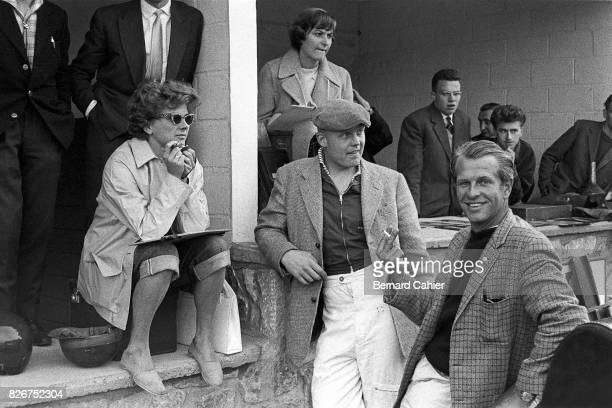

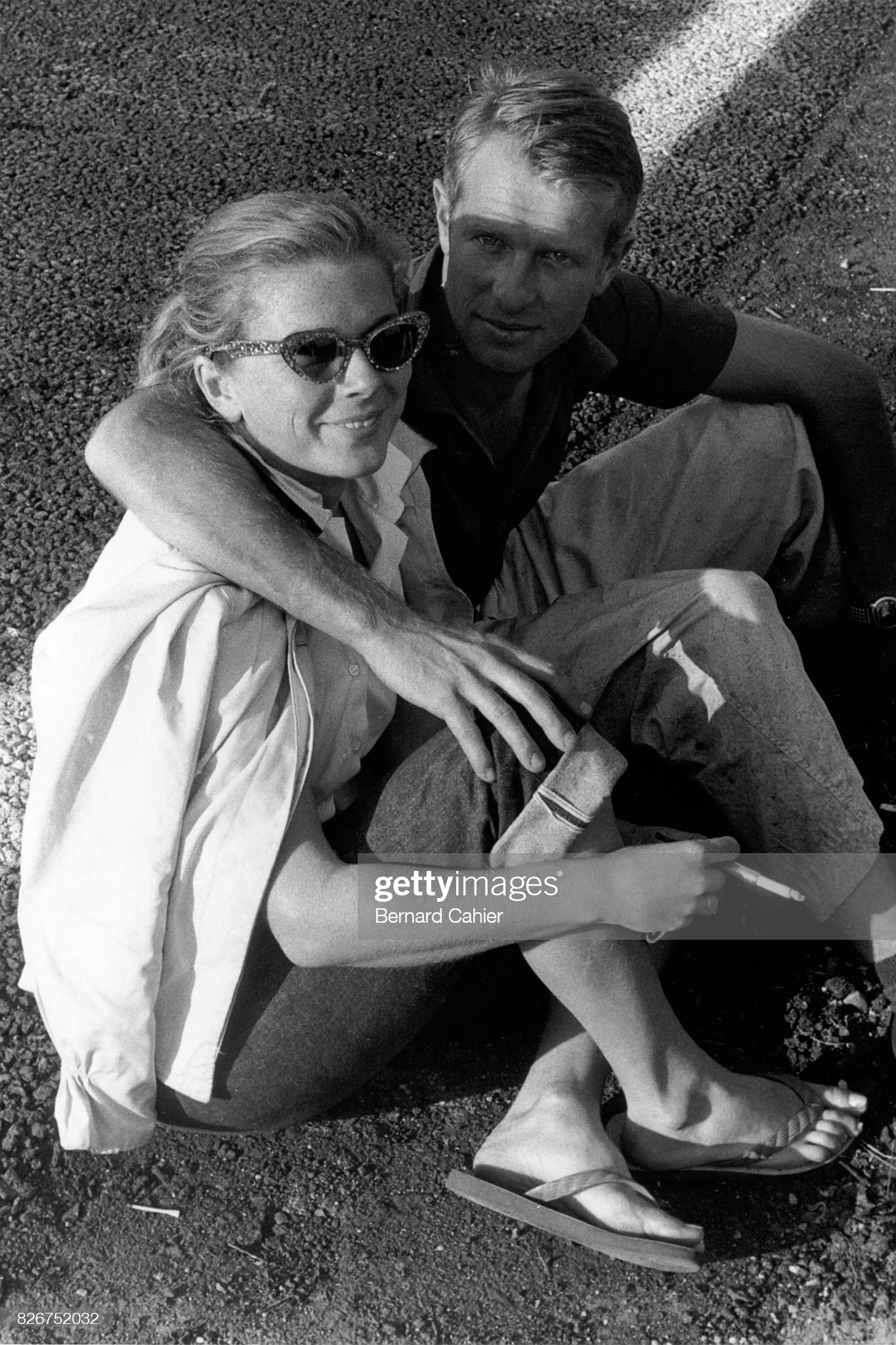

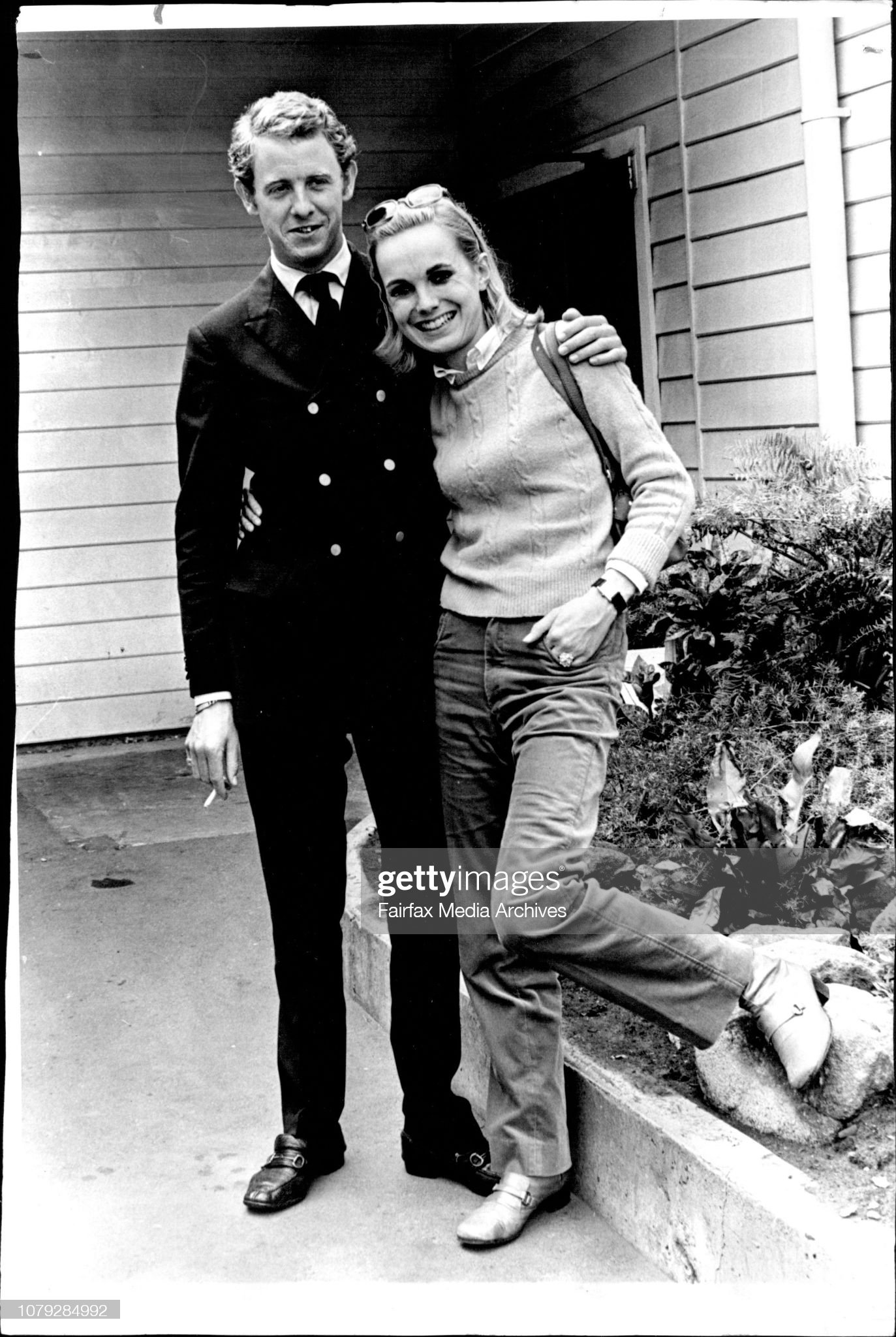

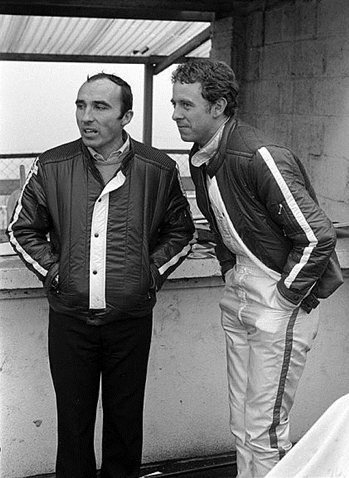

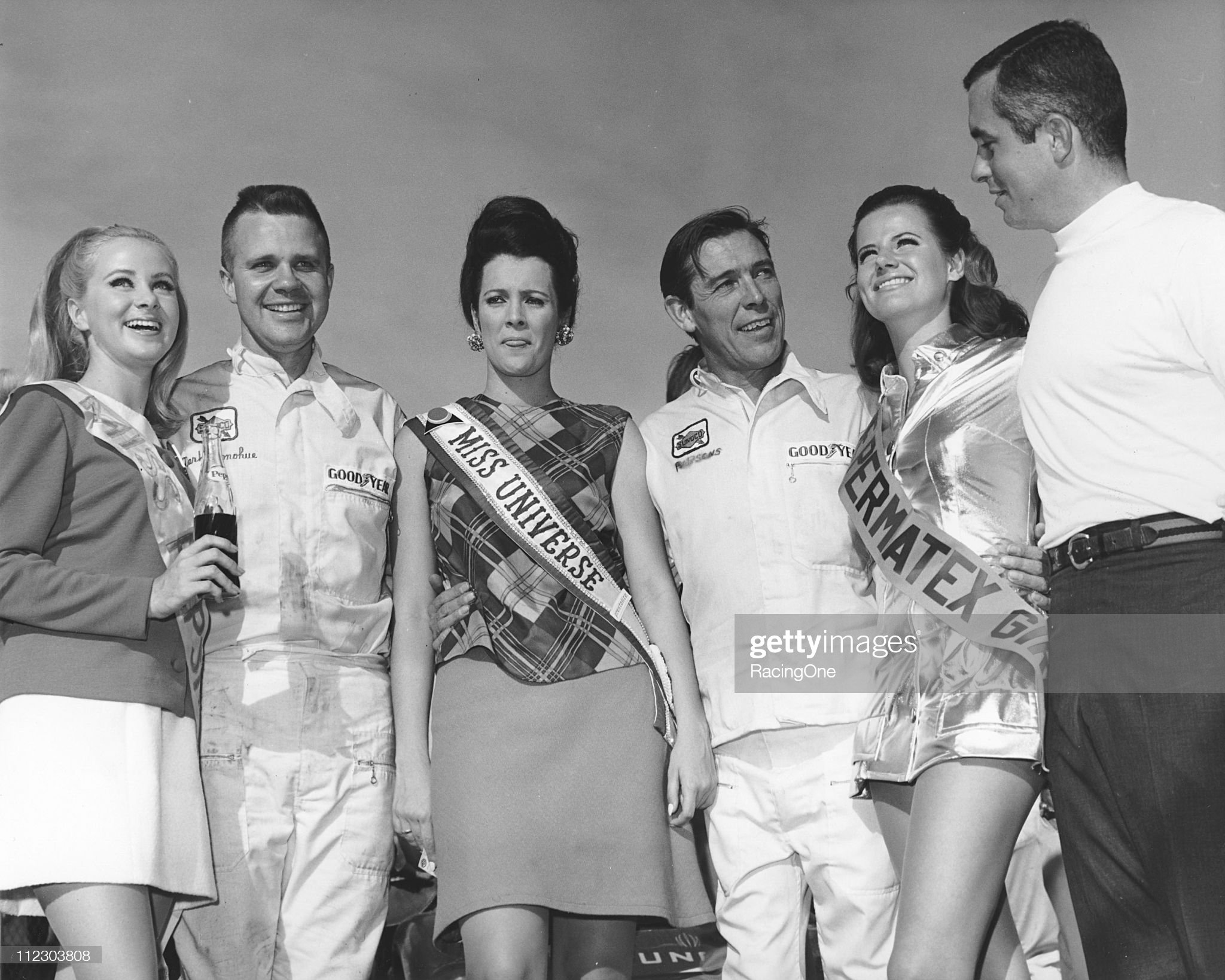

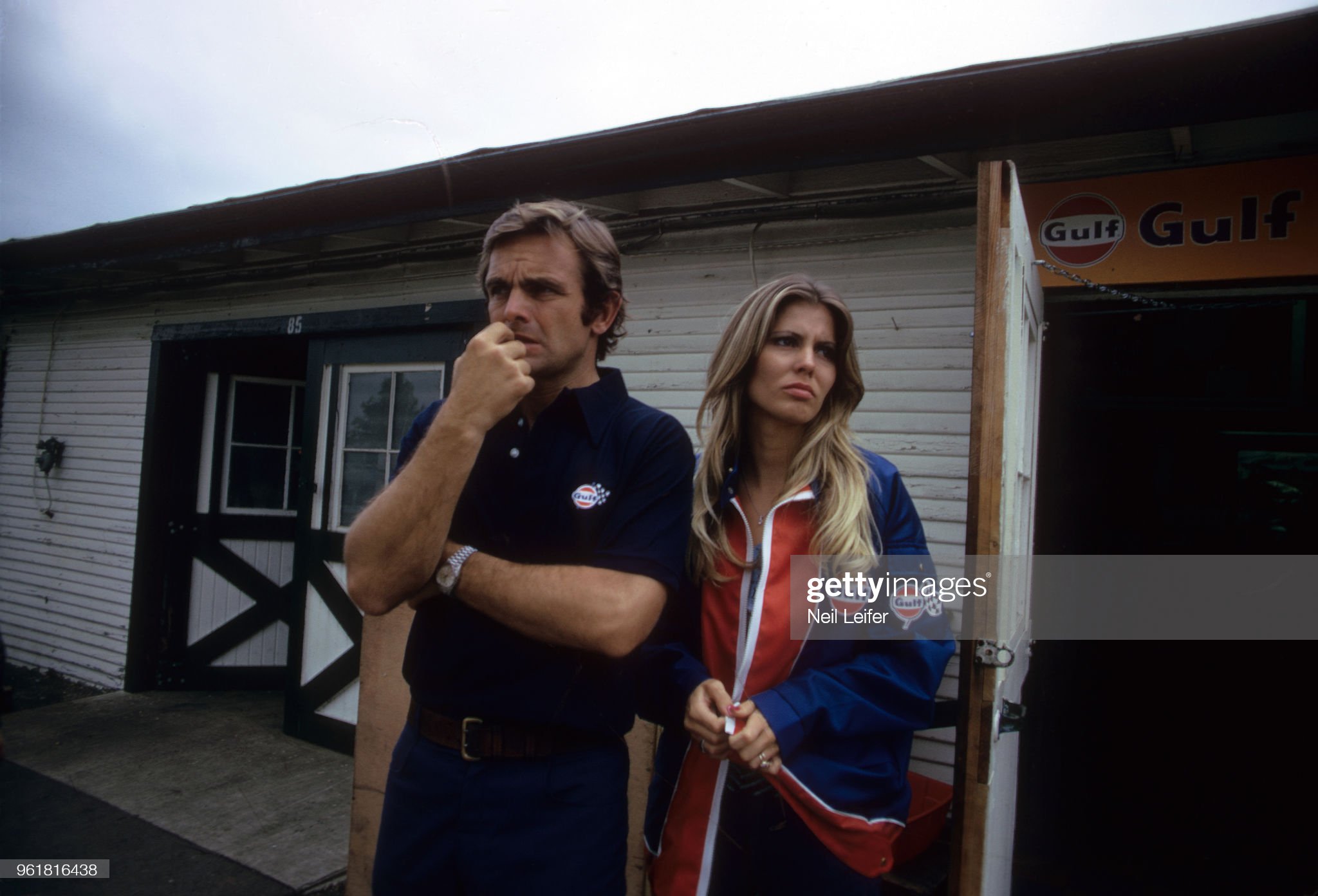

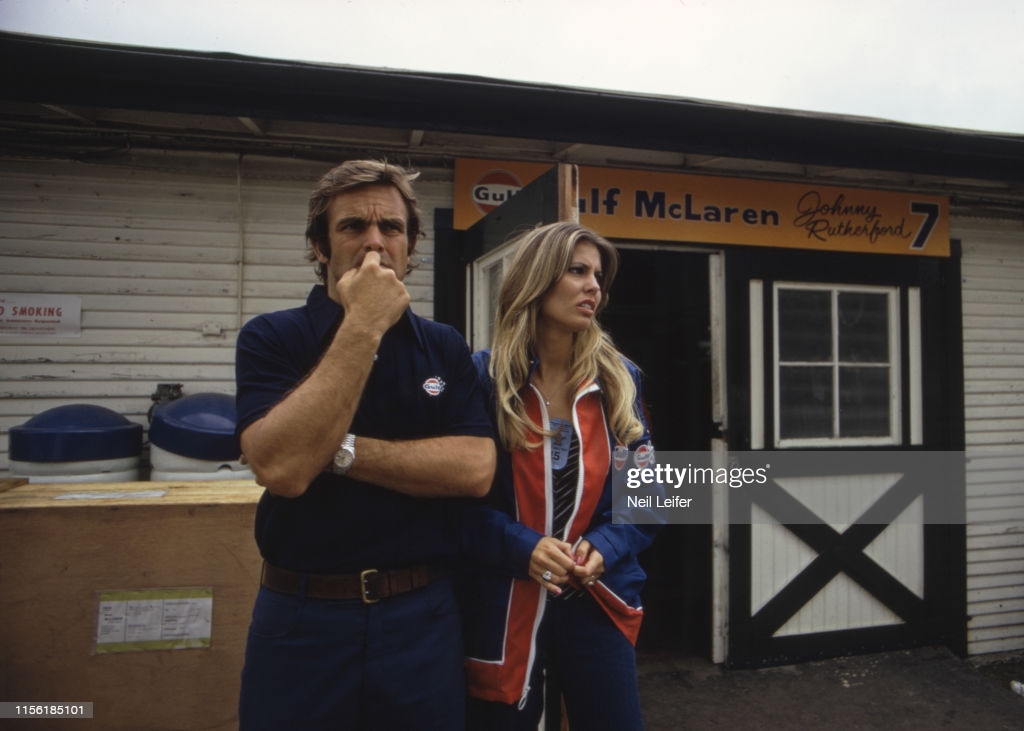

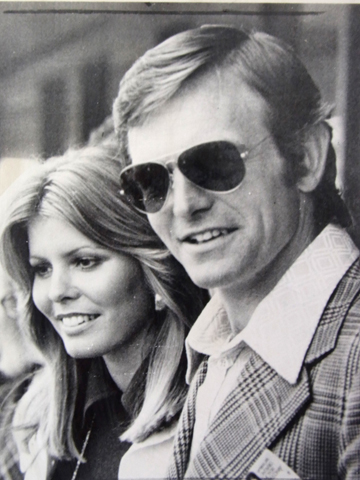

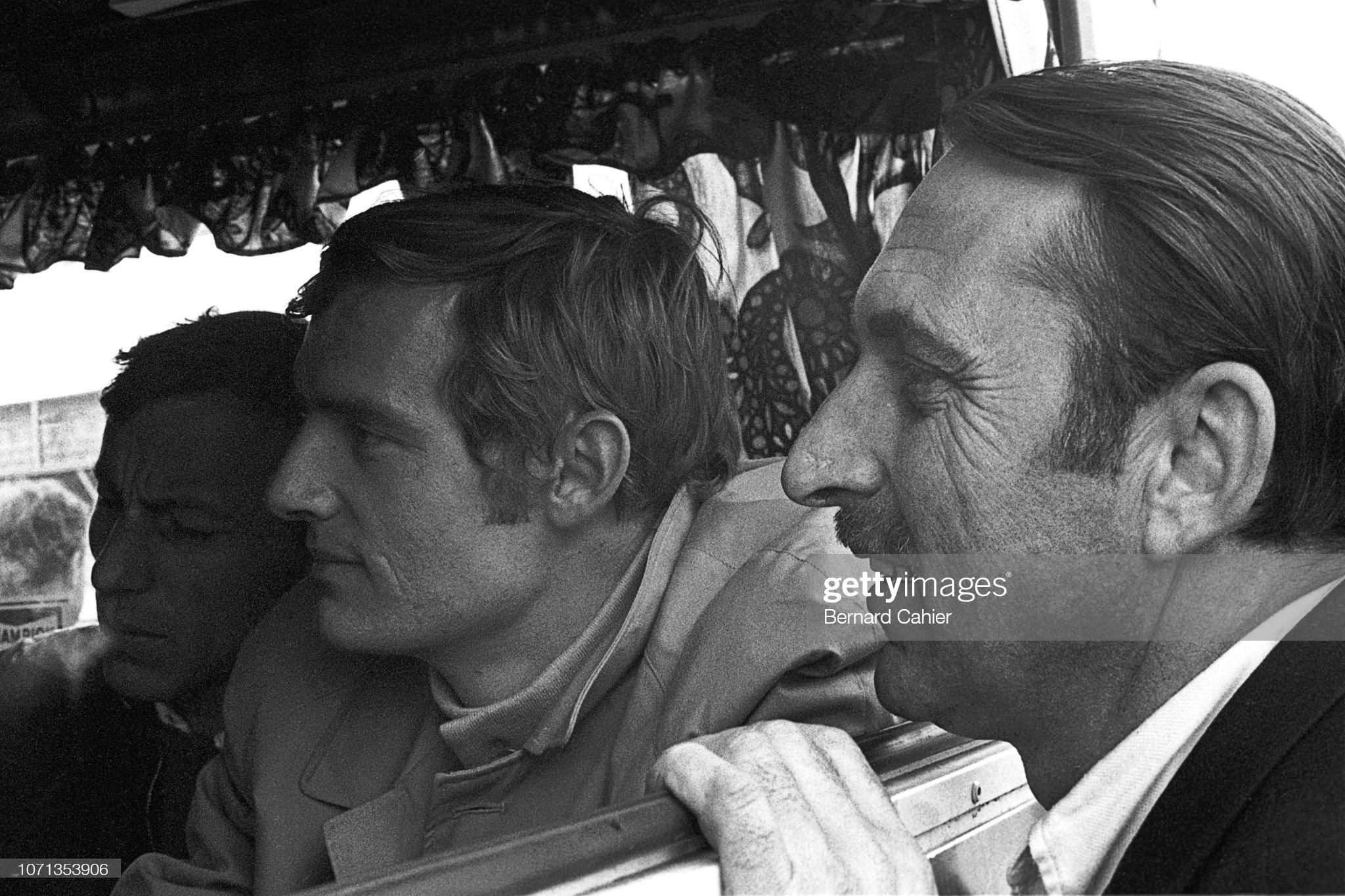

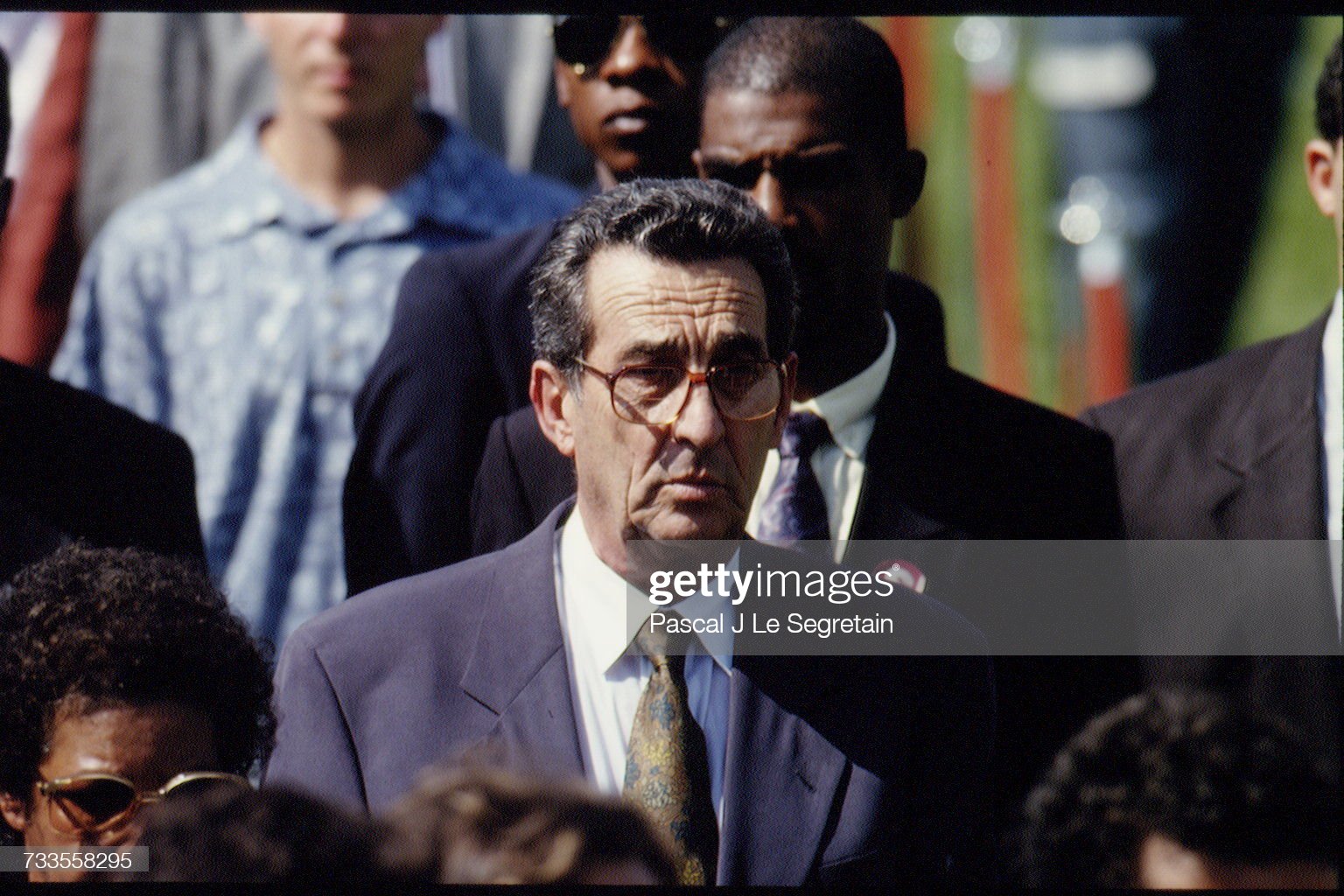

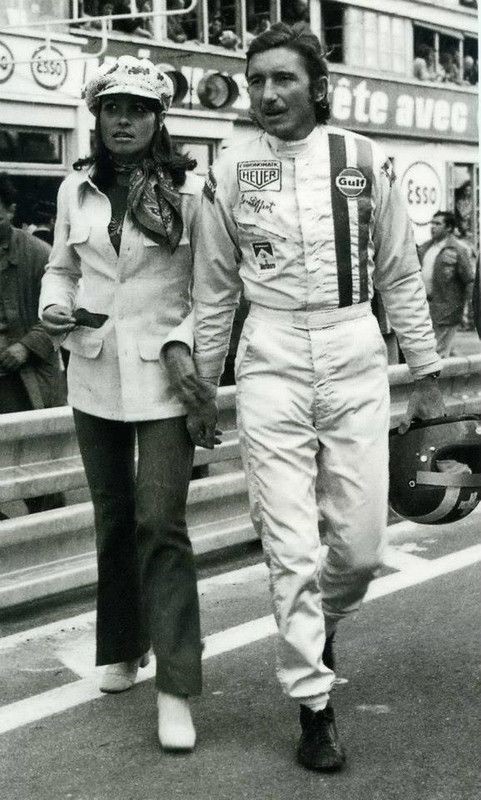

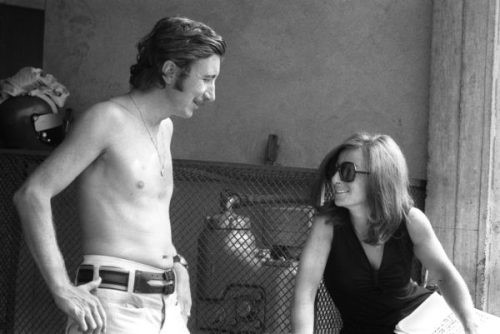

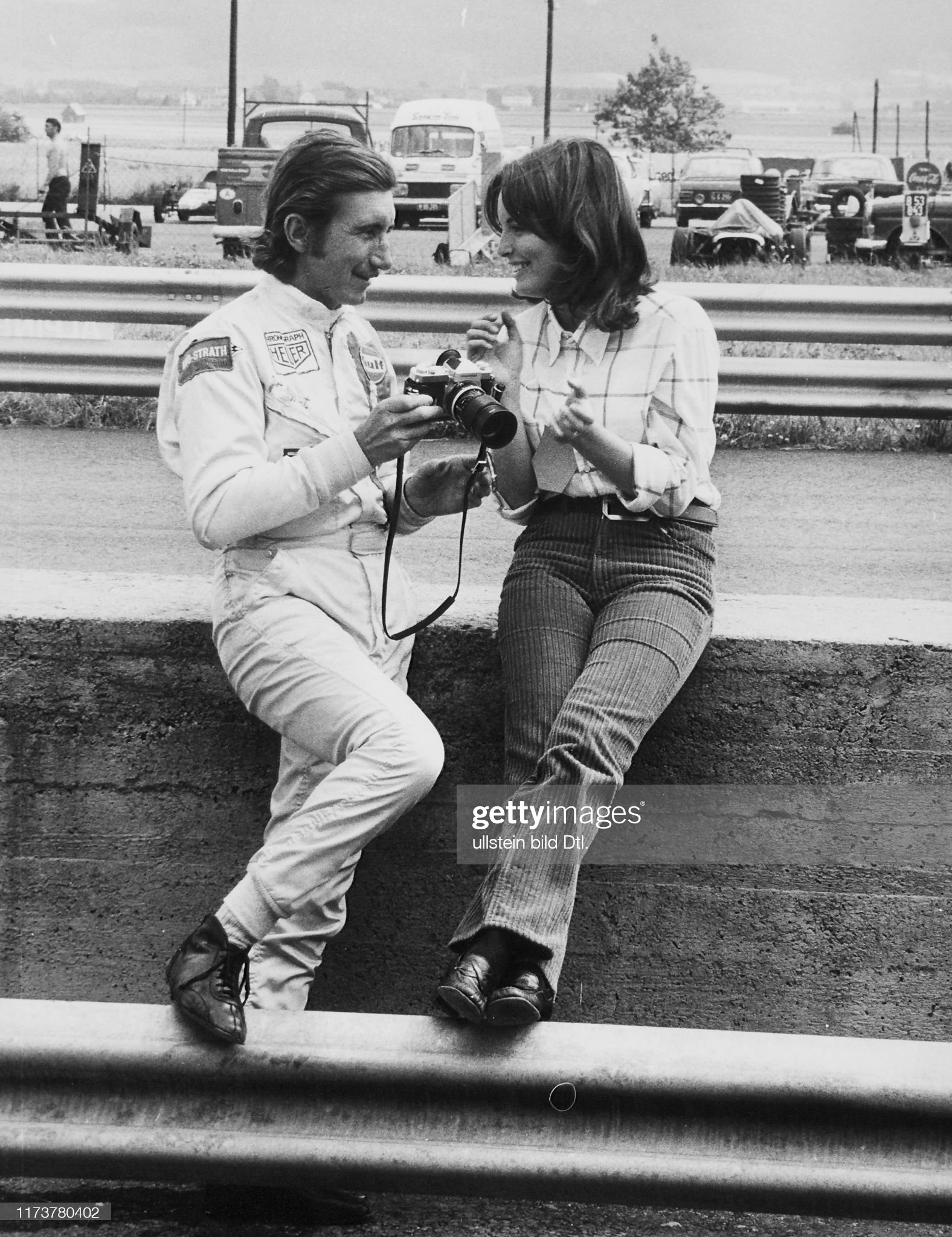

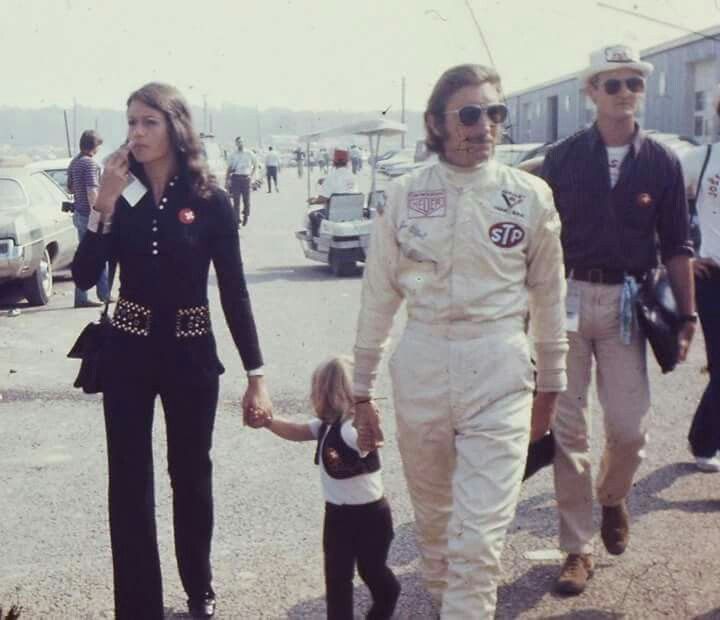

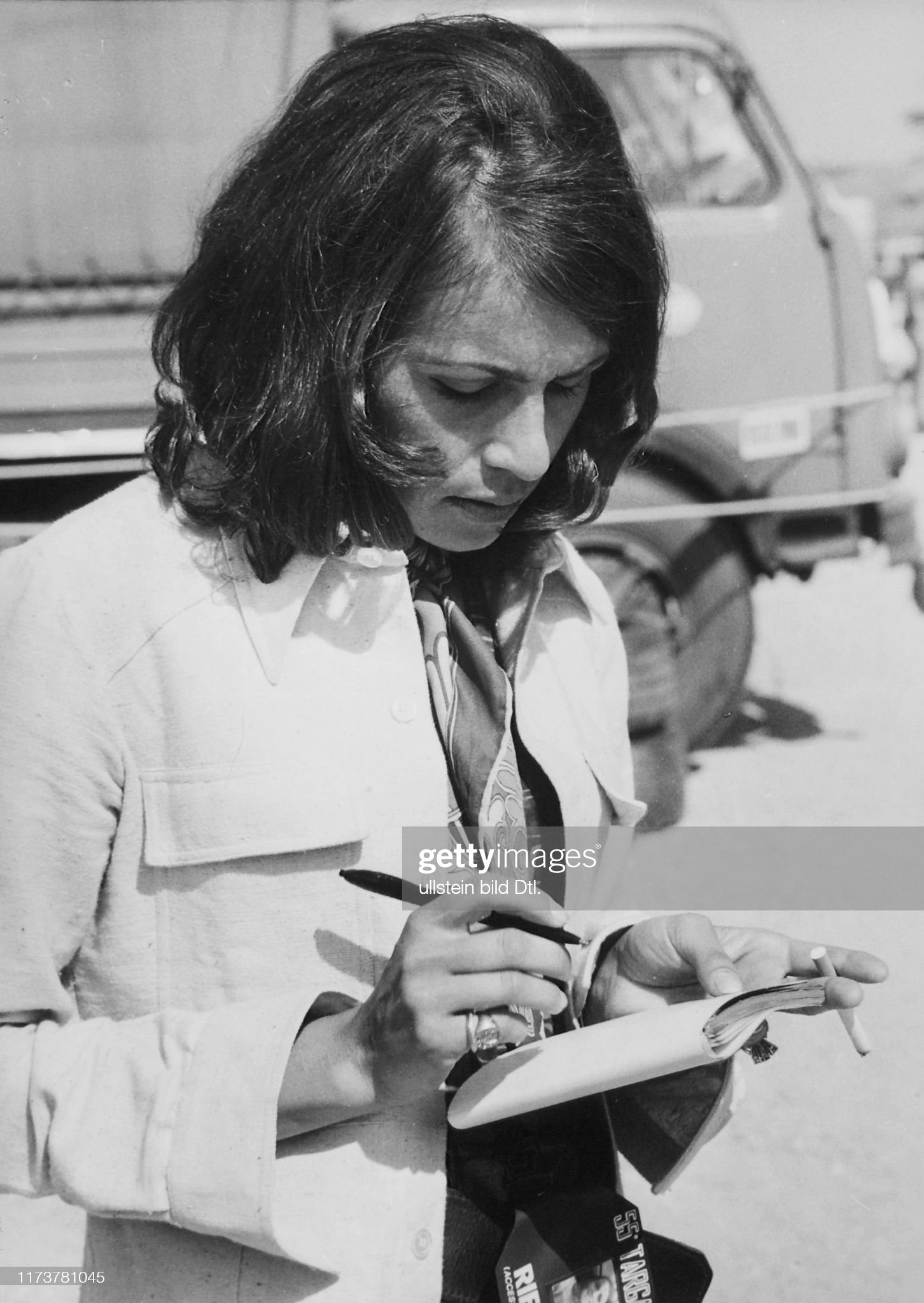

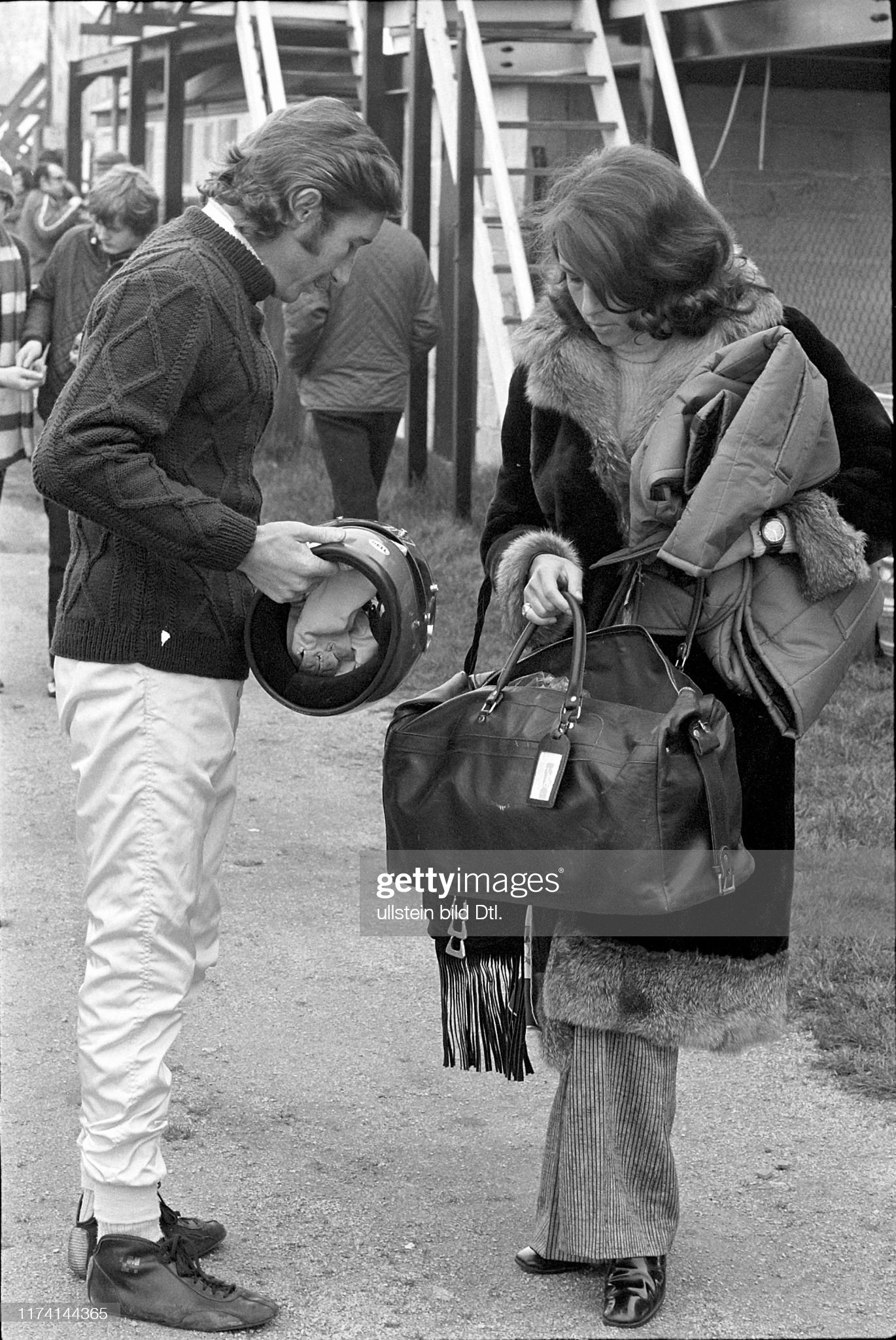

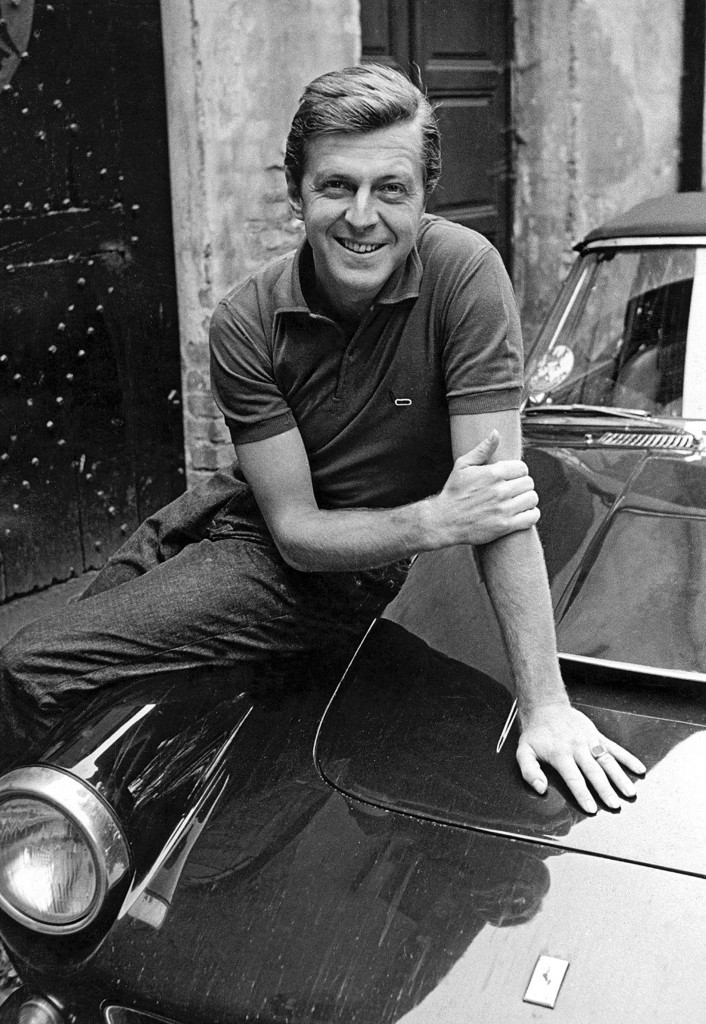

Jackie Stewart and his wife. Getty Images.

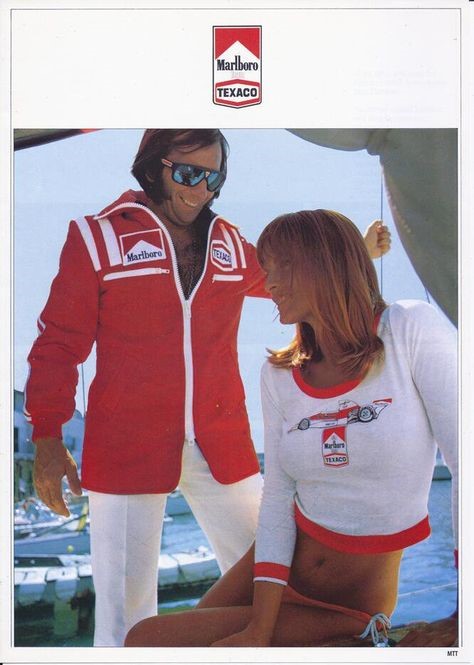

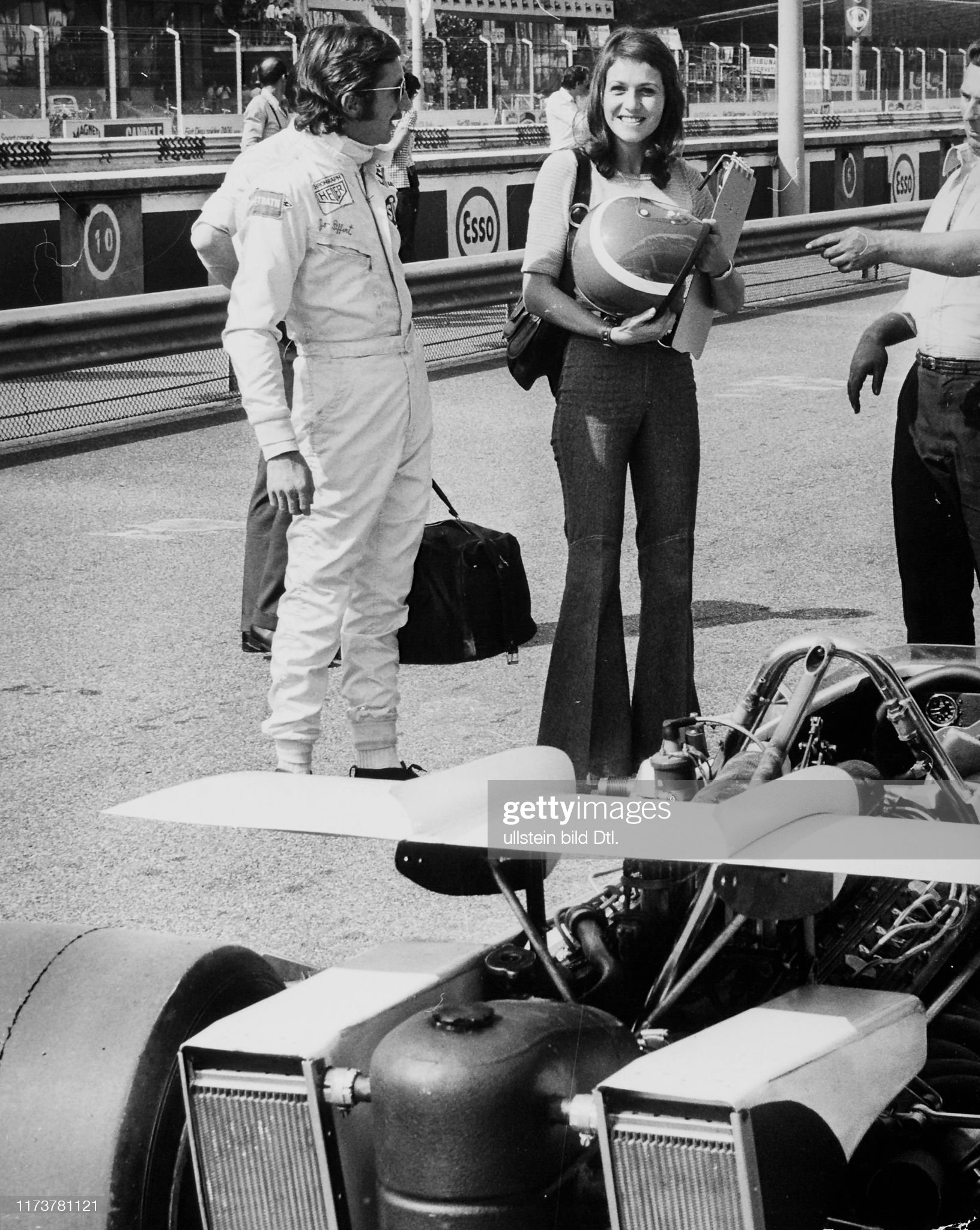

The high-octane world of F1 is a pinwheel of risk, danger and skill. It magnetises a likeminded, thrill-seeking audience who relish in the glitz and glamour that is a derivative of the consequence of the sports wide-ranging lucrative appeal. Picturesque racetracks, fast luxury sports cars, generous sponsors and royalty involvement is just a few of the sports ingredients that manifests hedonism, splendour and indulgence. Now commercialised on a stratospheric scale, the top tier of the single-seat sport has always been synonymous with style, particularly through the audacious and charismatic drivers who perform the unthinkable on and off the track. It is why the crème-de-la-crème of the stylish elite, from Hollywood, royalty, politicians and corporators want to join in for the ride.

"For Enzo Ferrari it was essential to do prototype races and win them, after which it was possible, almost like a prize, to dedicate to F1. Because, according to the Commendatore, working in F1 was a prize for the technicians. They had fun, he said …" Mauro Forghieri

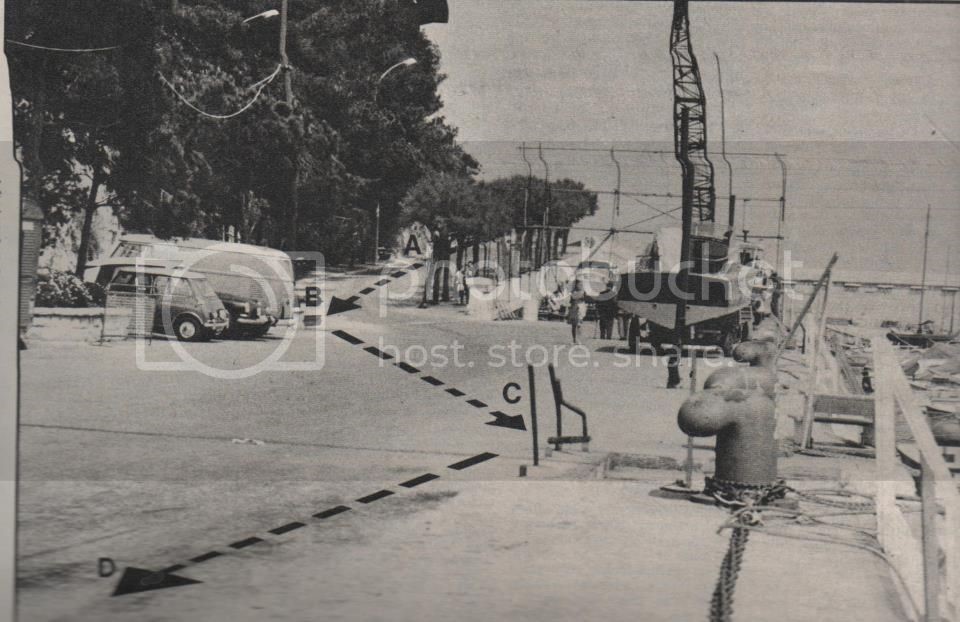

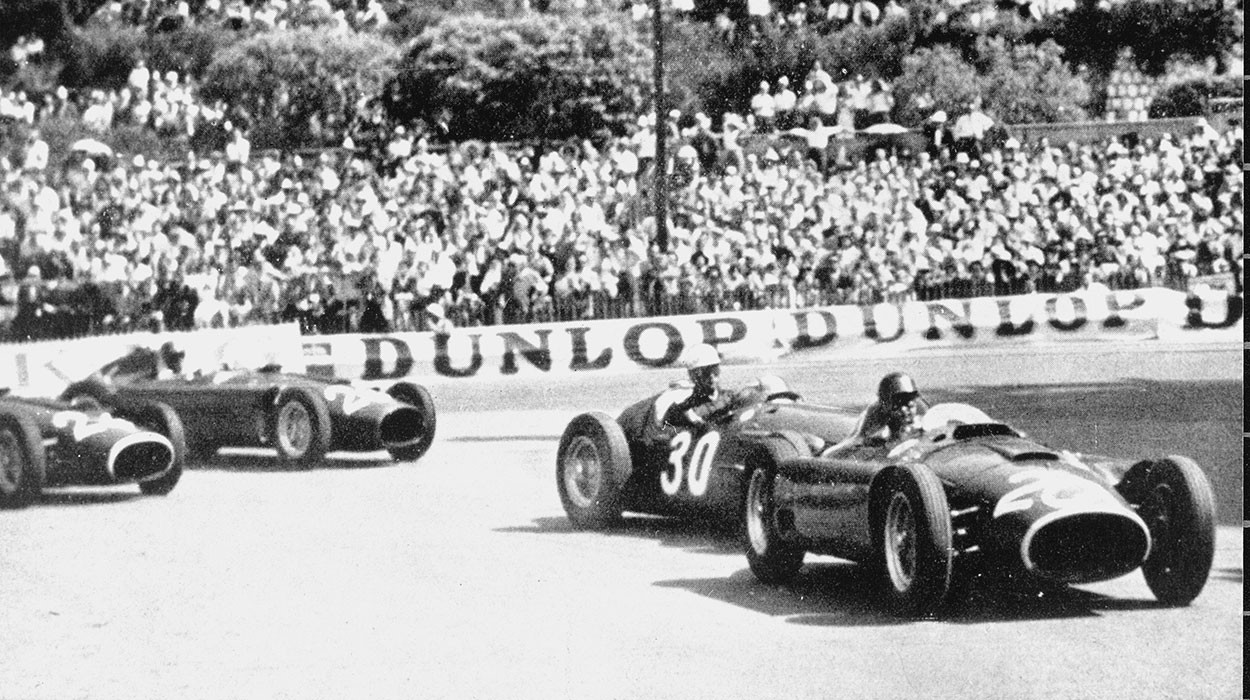

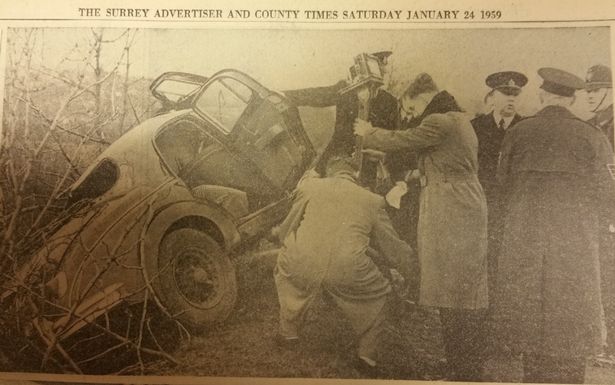

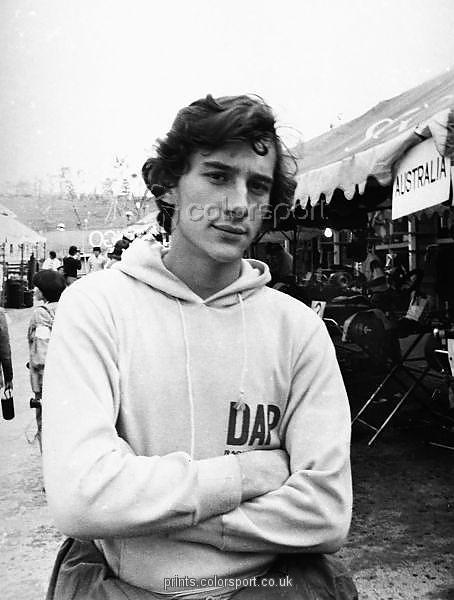

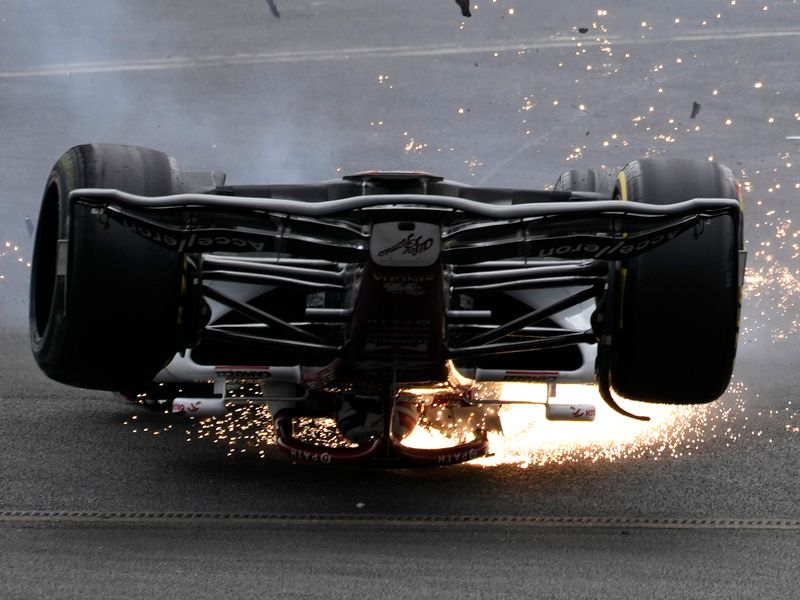

Australian Paul Hawkins flies into the harbor in the F1 race in Monaco in 1965. He survived.

But Formula 1 is not just champagne and beautiful women but also hospital beds and funerals. And this is also confirmed by the statements of the drivers or those who have lived directly or simply heard of the roaring years of the top formula.

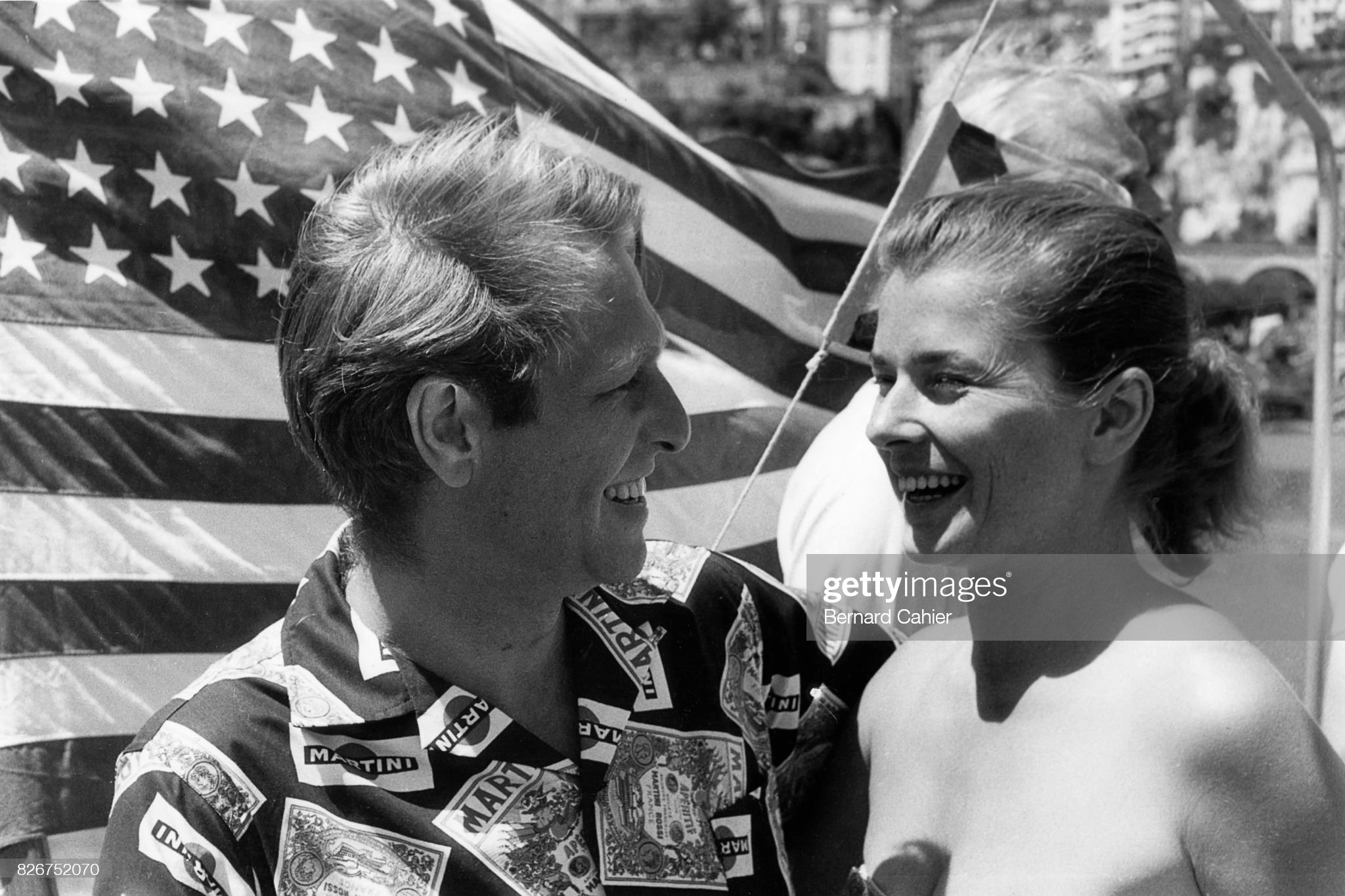

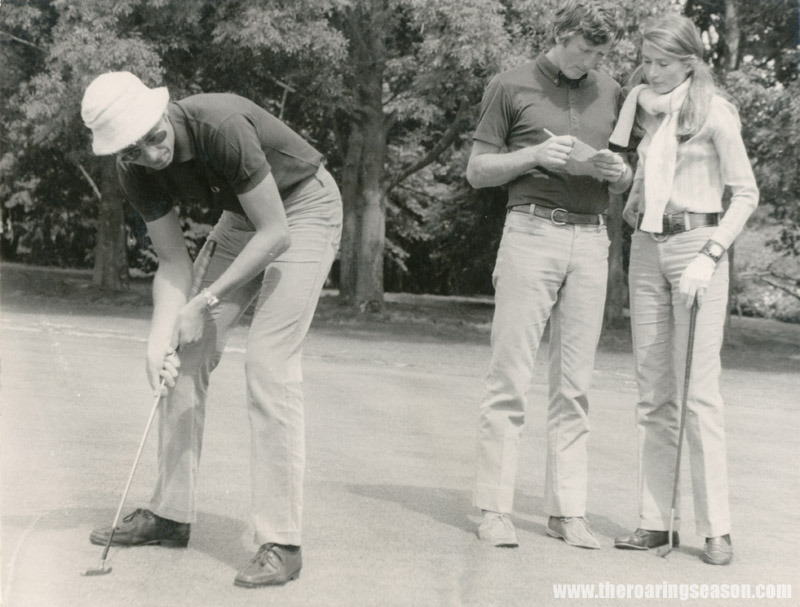

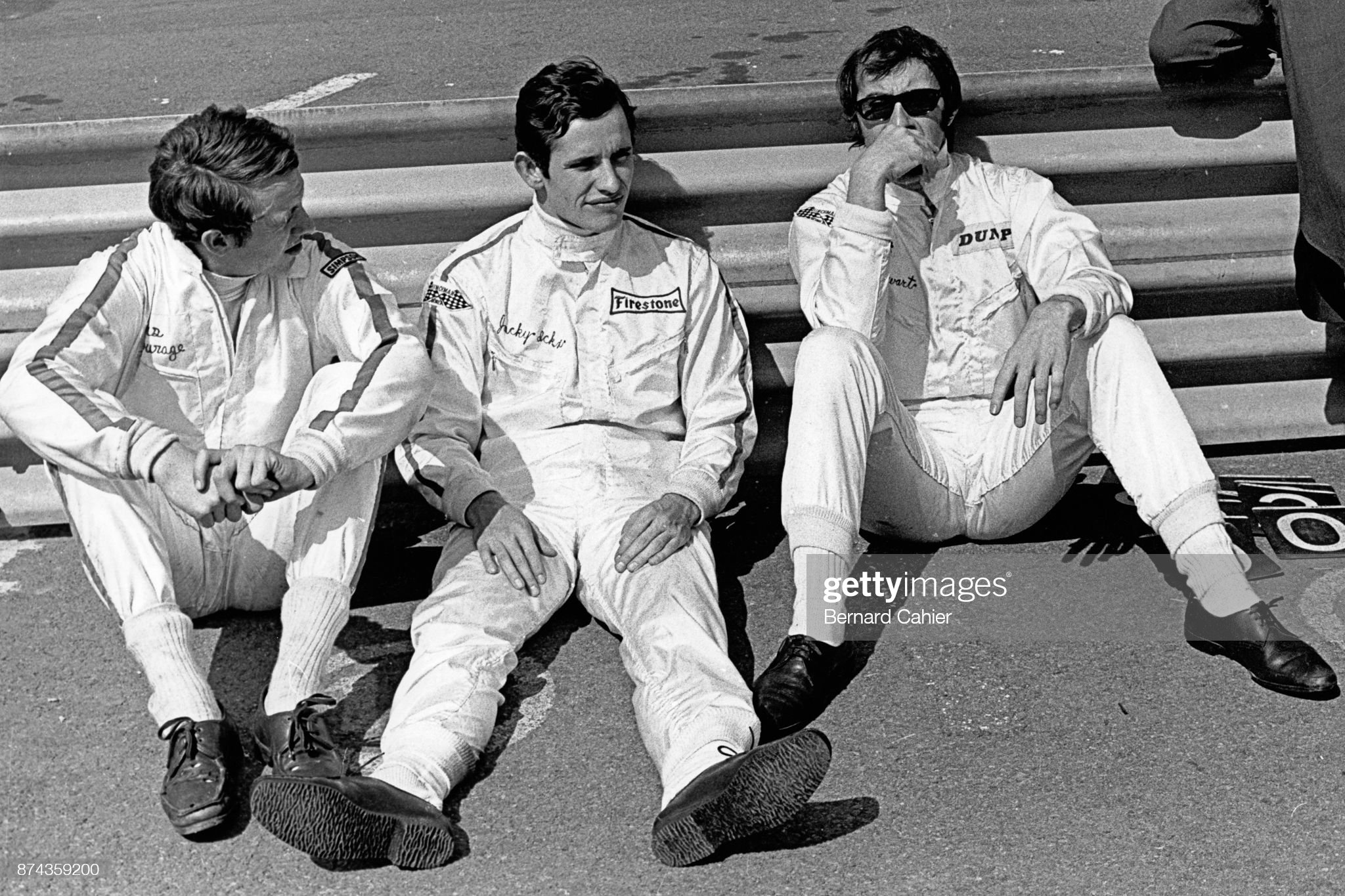

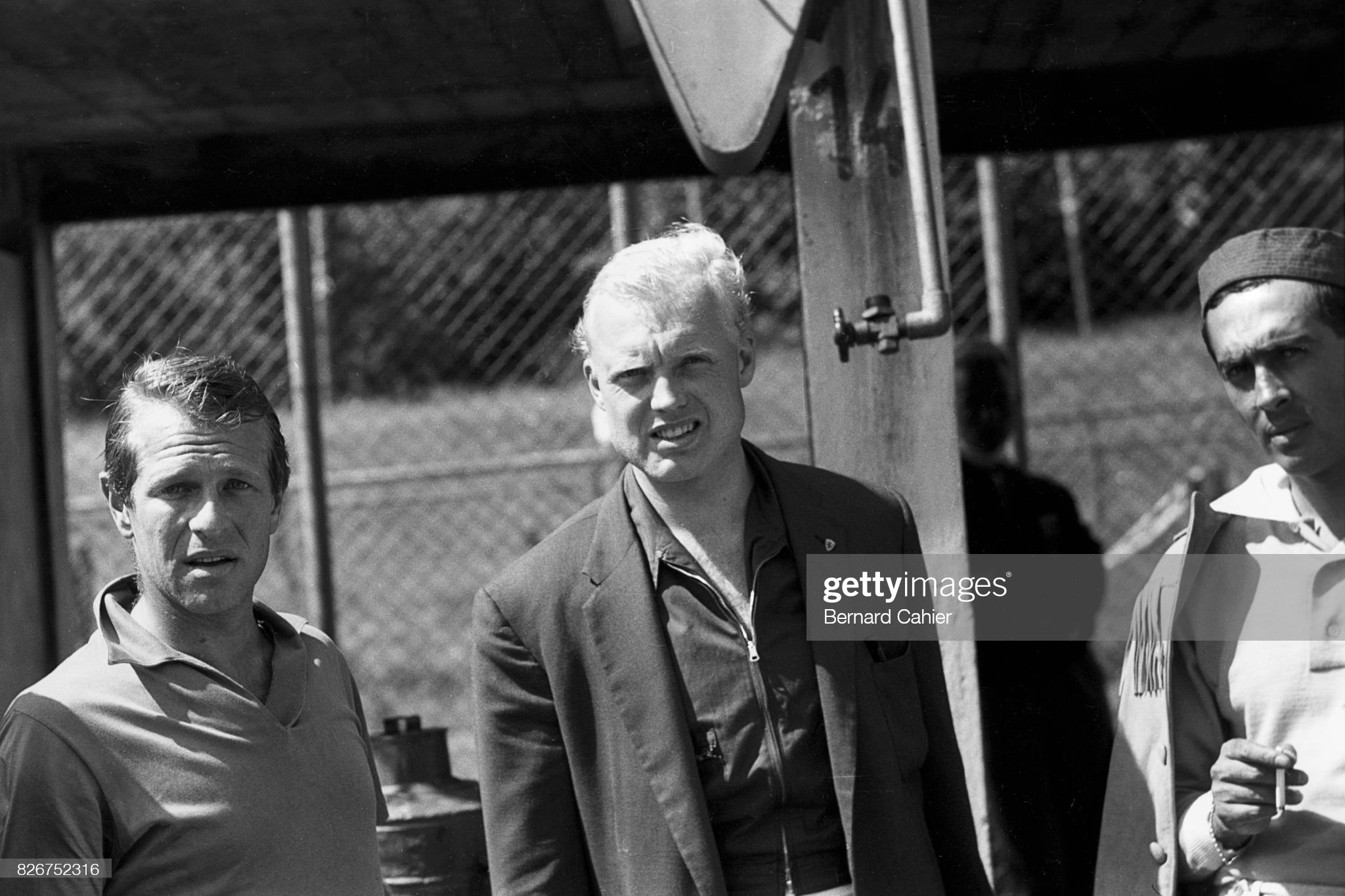

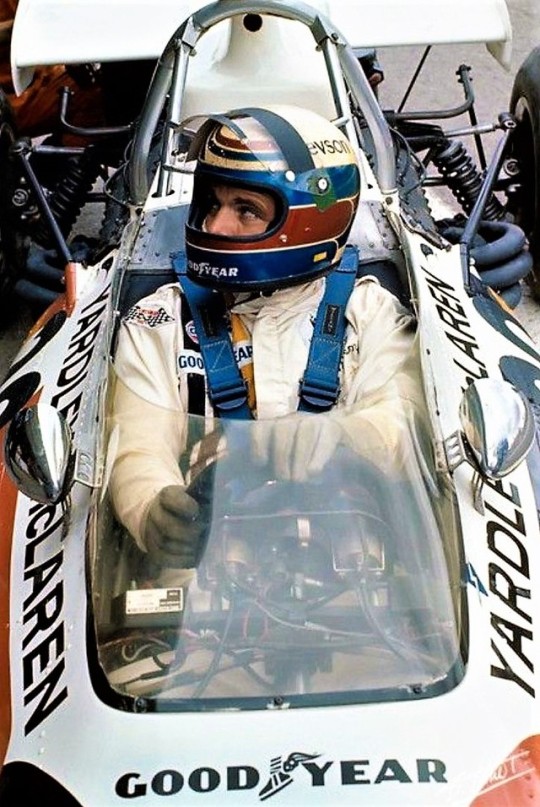

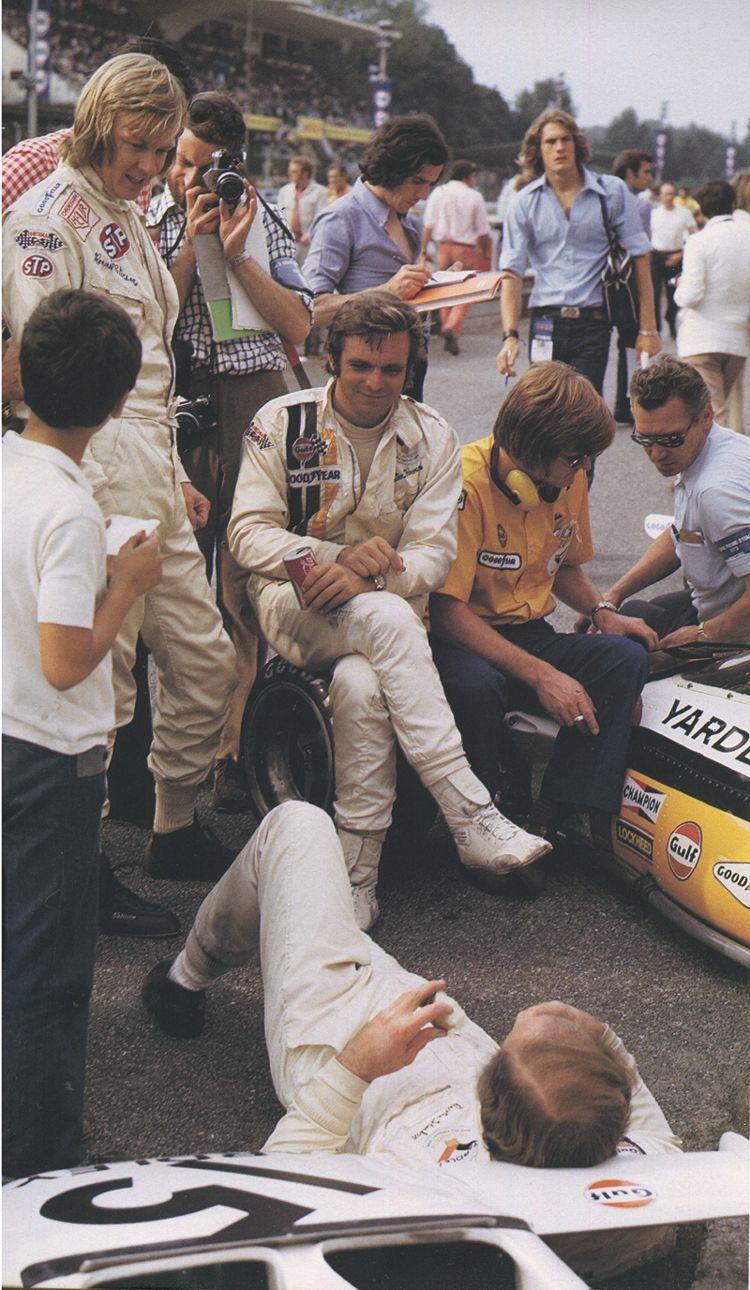

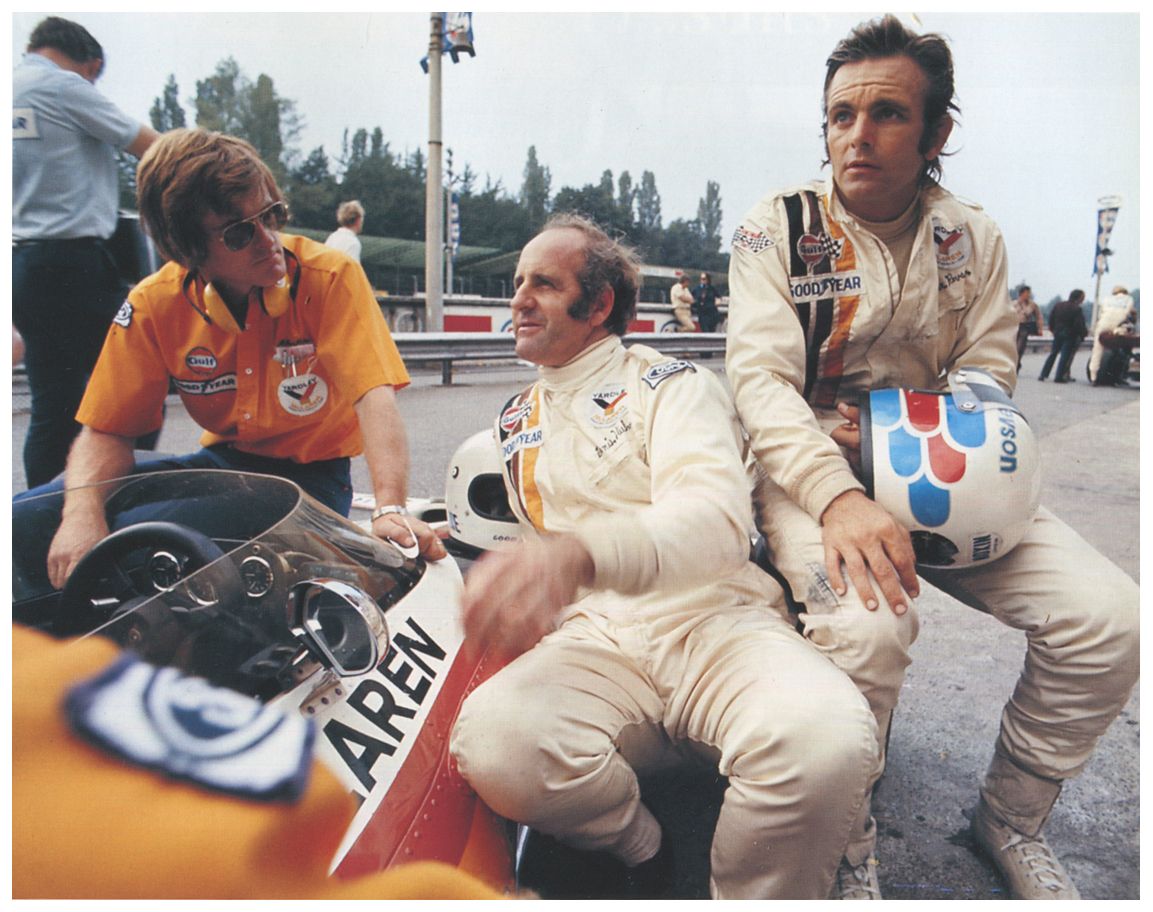

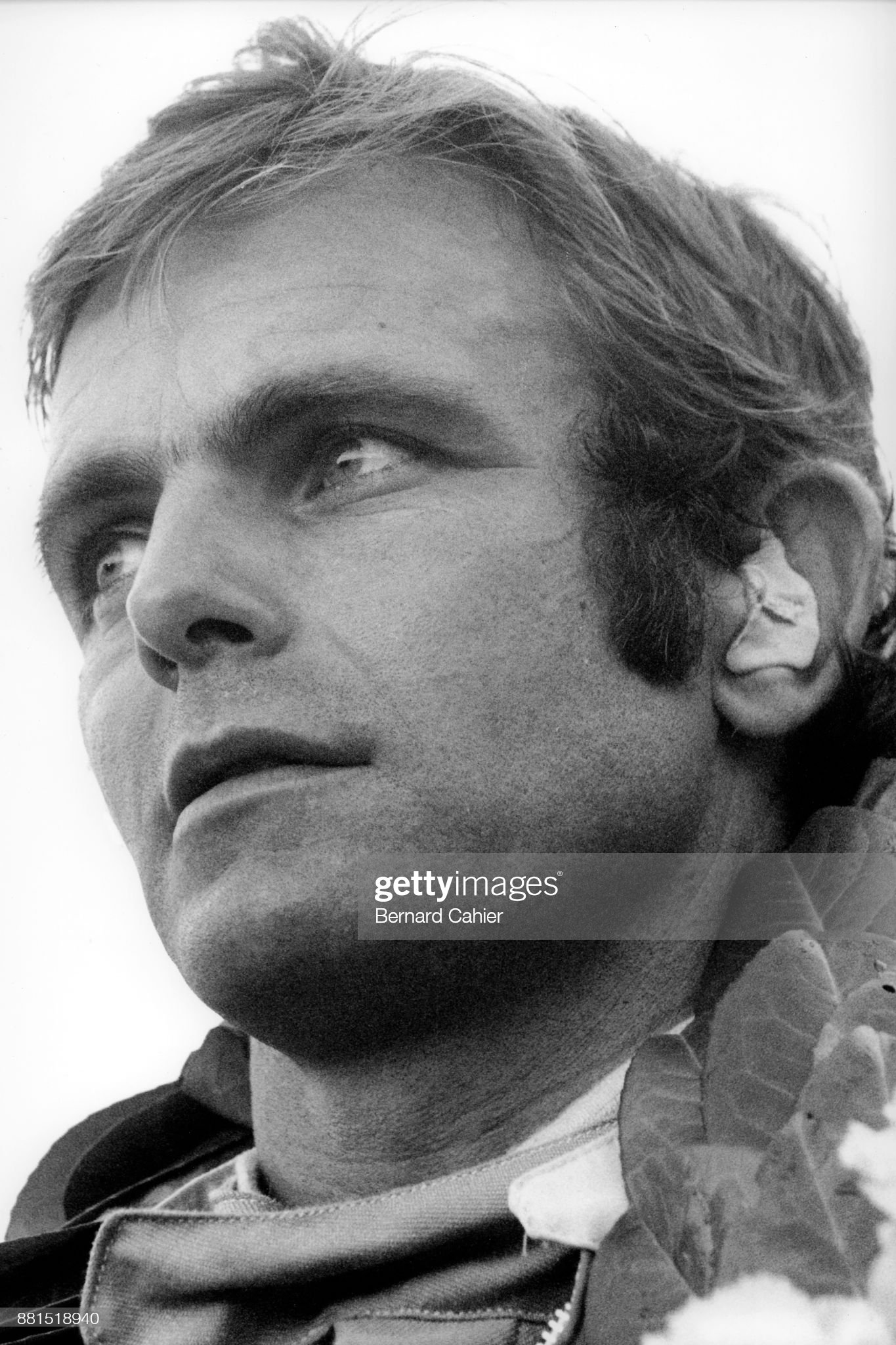

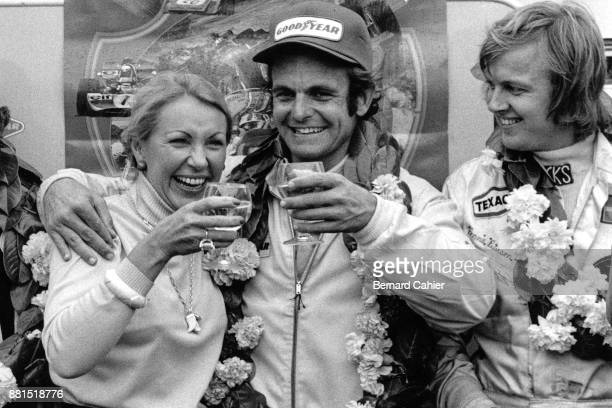

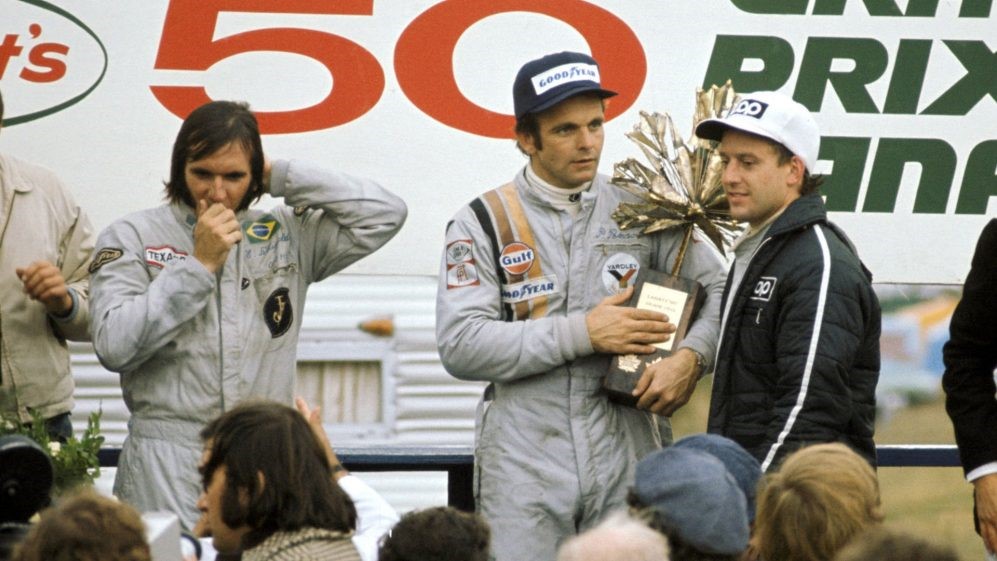

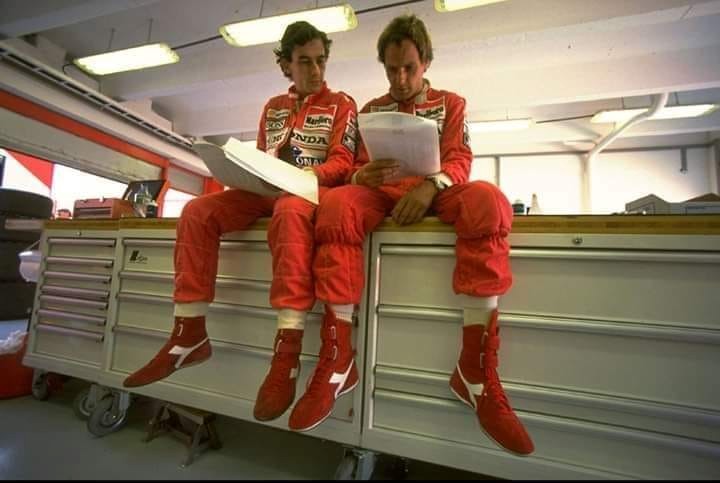

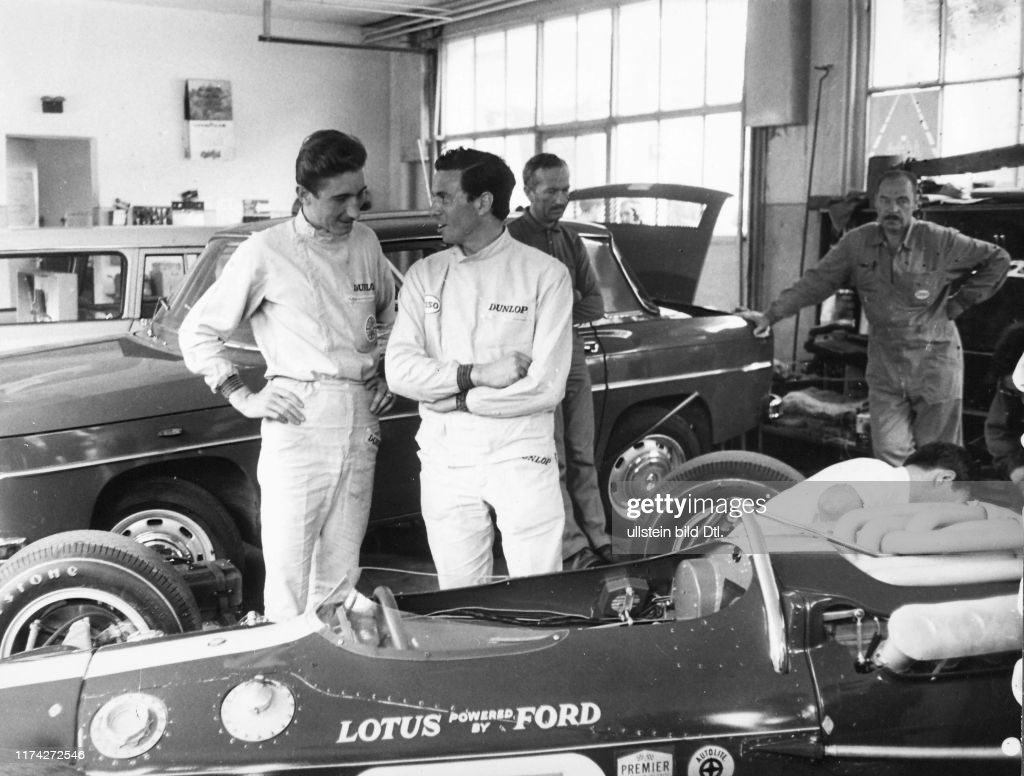

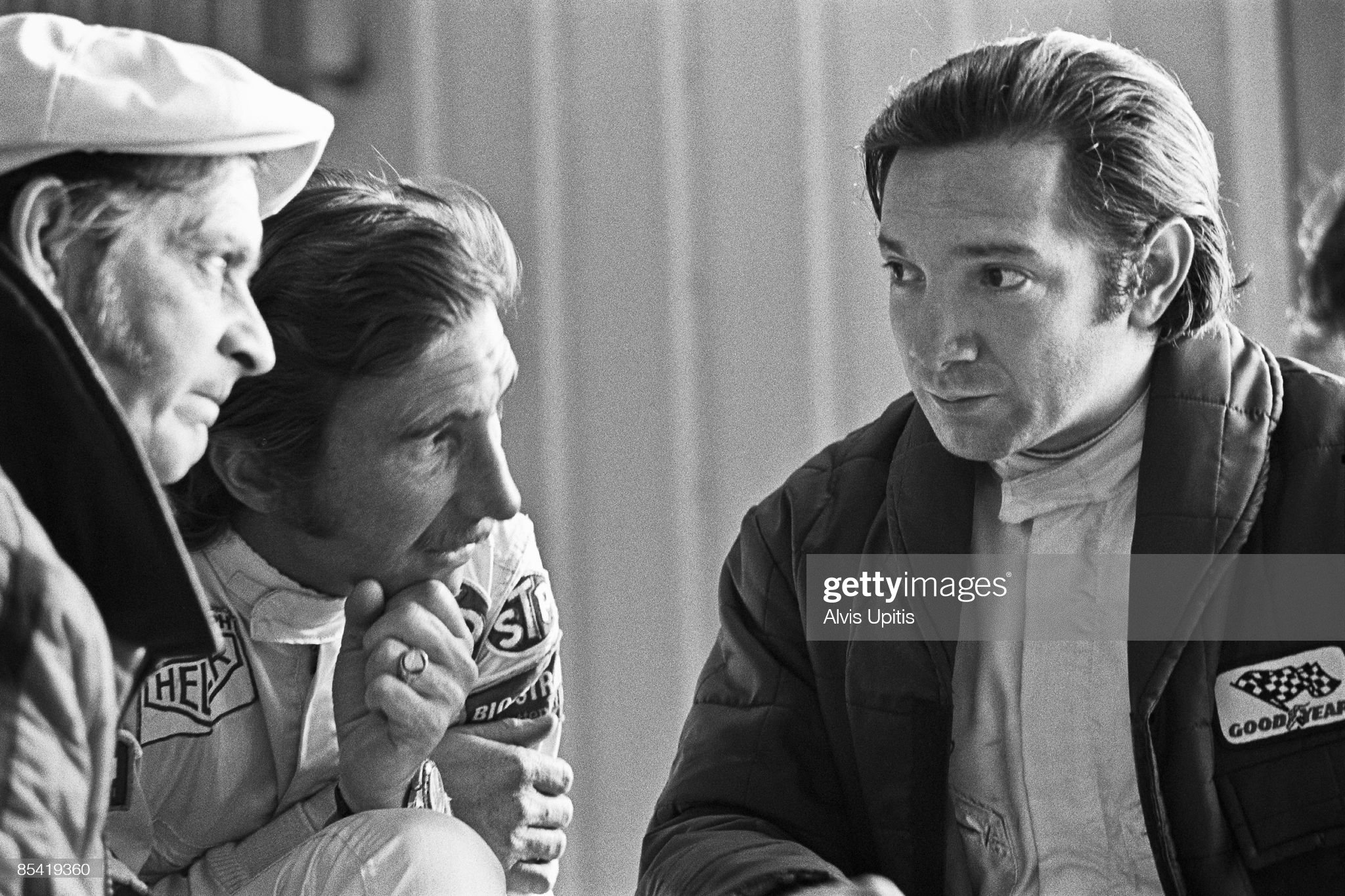

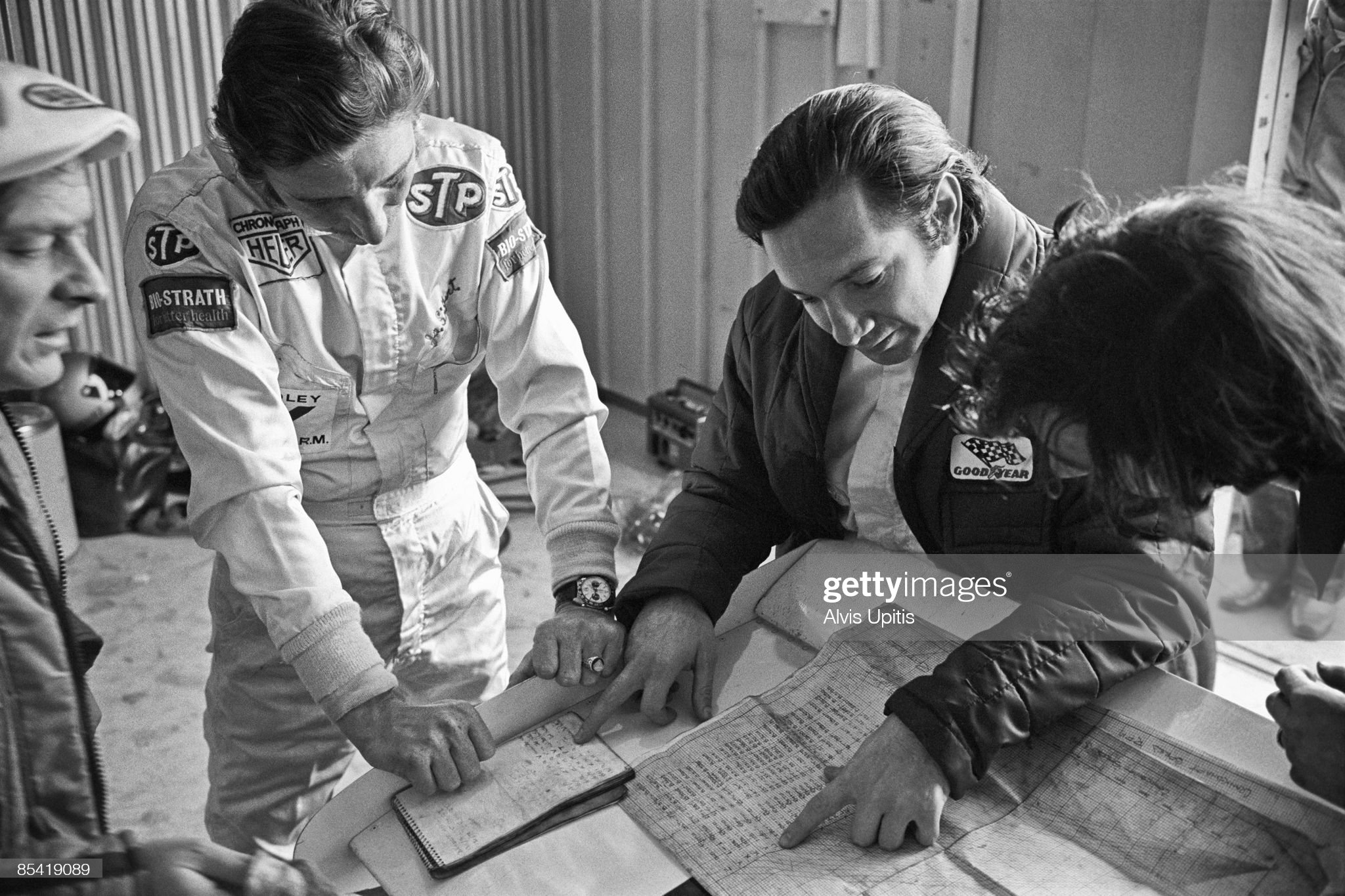

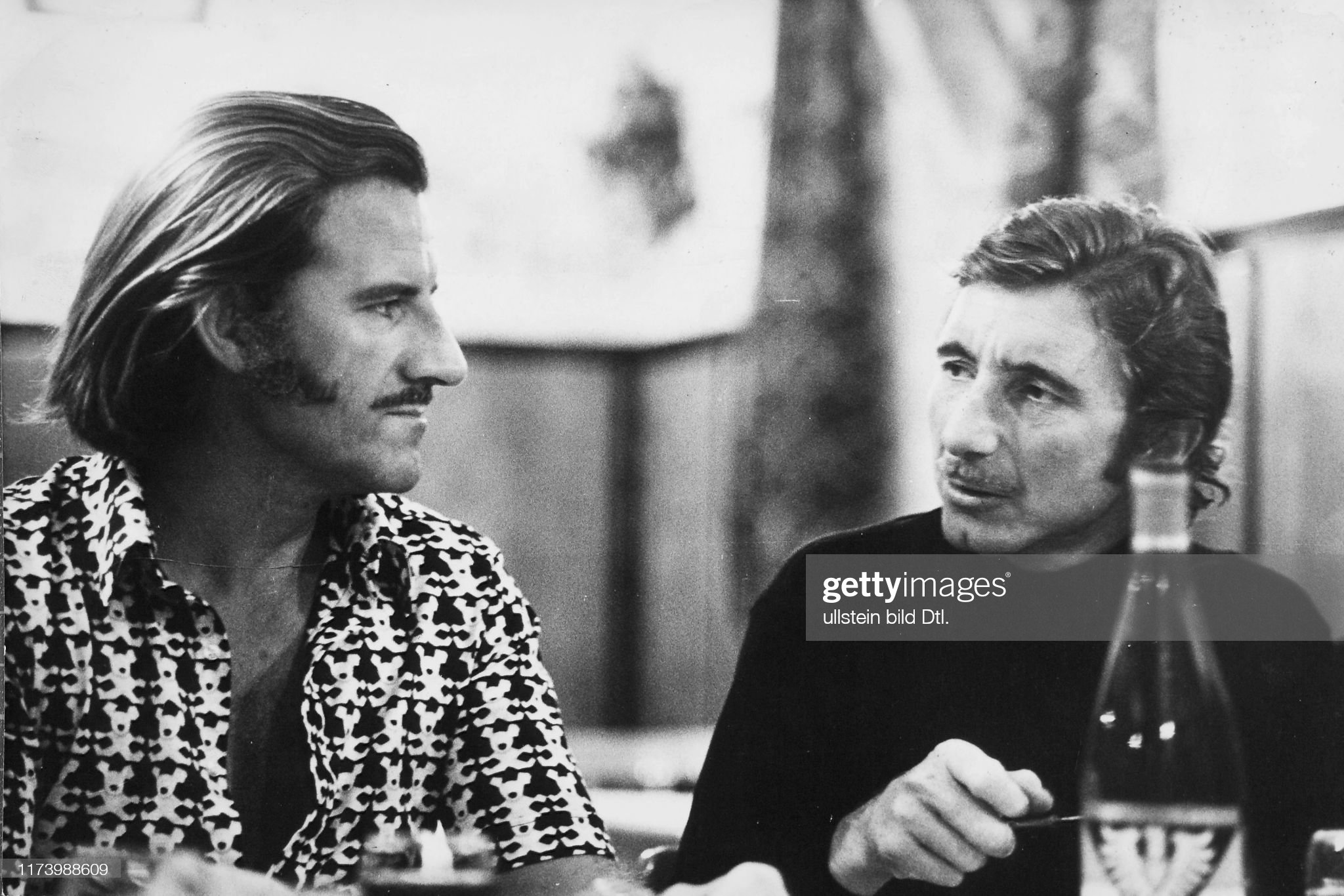

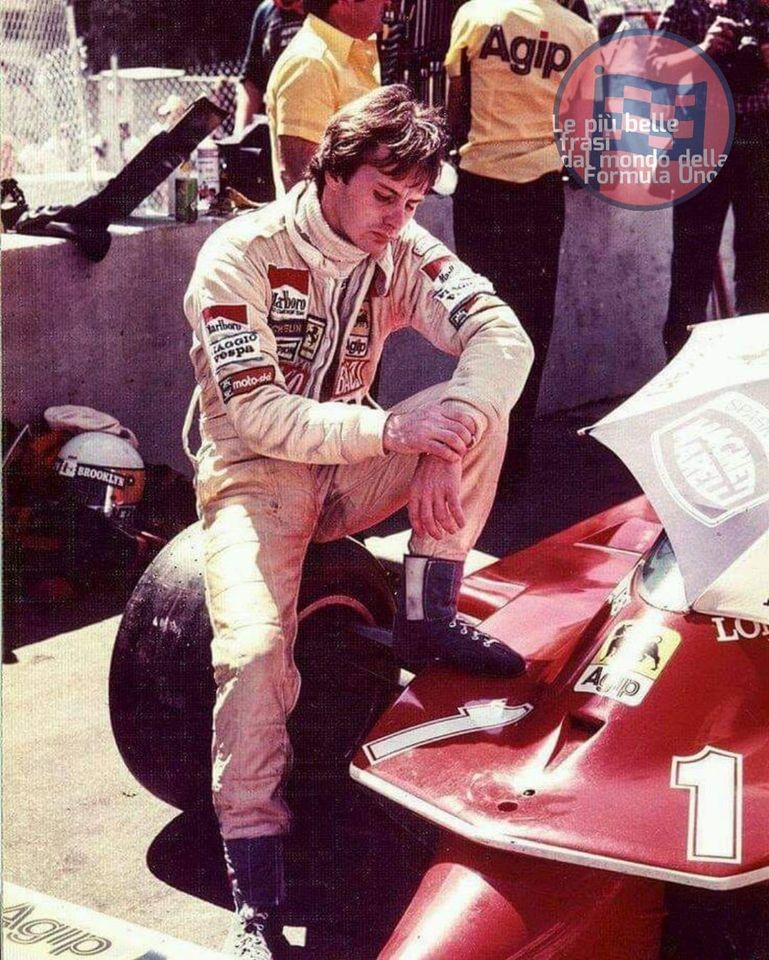

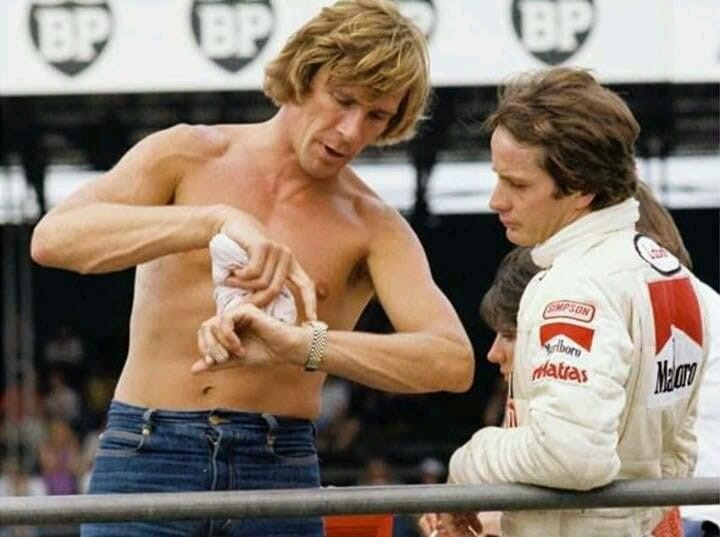

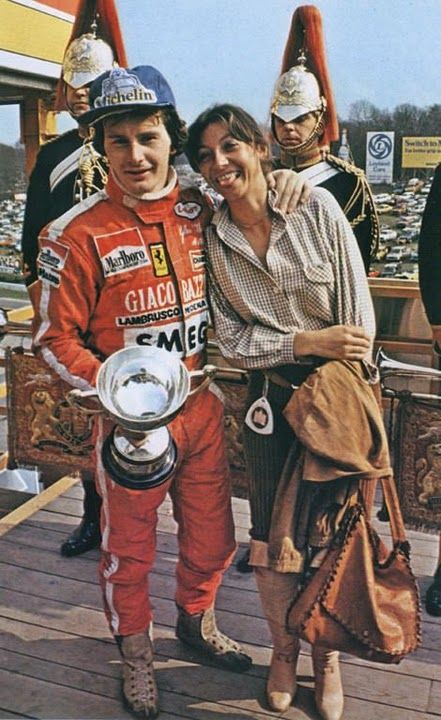

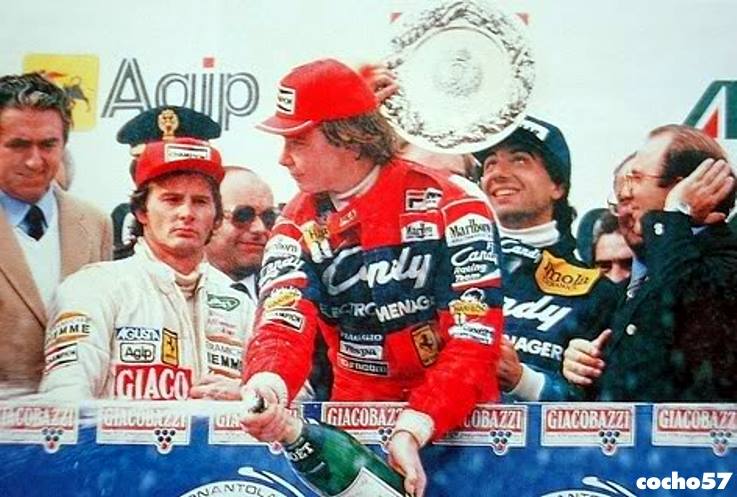

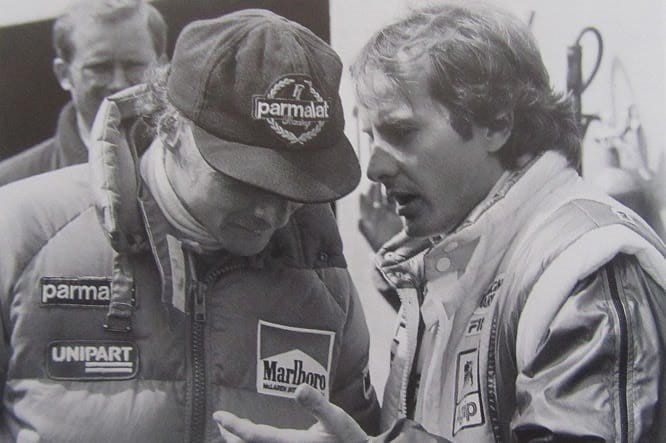

Niki Lauda with James Hunt.

"Every year 25 drivers take part in the Formula 1 world championship and every year two of us lose their lives. Who can choose such a job? Not normal people, that's for sure. Rebels. Crazy people. Dreamers. People who would do anything to make their mark and who are willing to die to succeed. My name is Niki Lauda, and, in the racing world, I am famous for two things. The first is my rivalry with James Hunt. I don't know why it became such an important story. We were just two drivers pissing each other off. I don't find anything freaky about this but the others obviously didn't see it that way and, in whatever happened between us, they saw something deeper [...]. The other thing I am remembered for is what happened on August 1st, 1976, while I was chasing him like an idiot." Niki Lauda

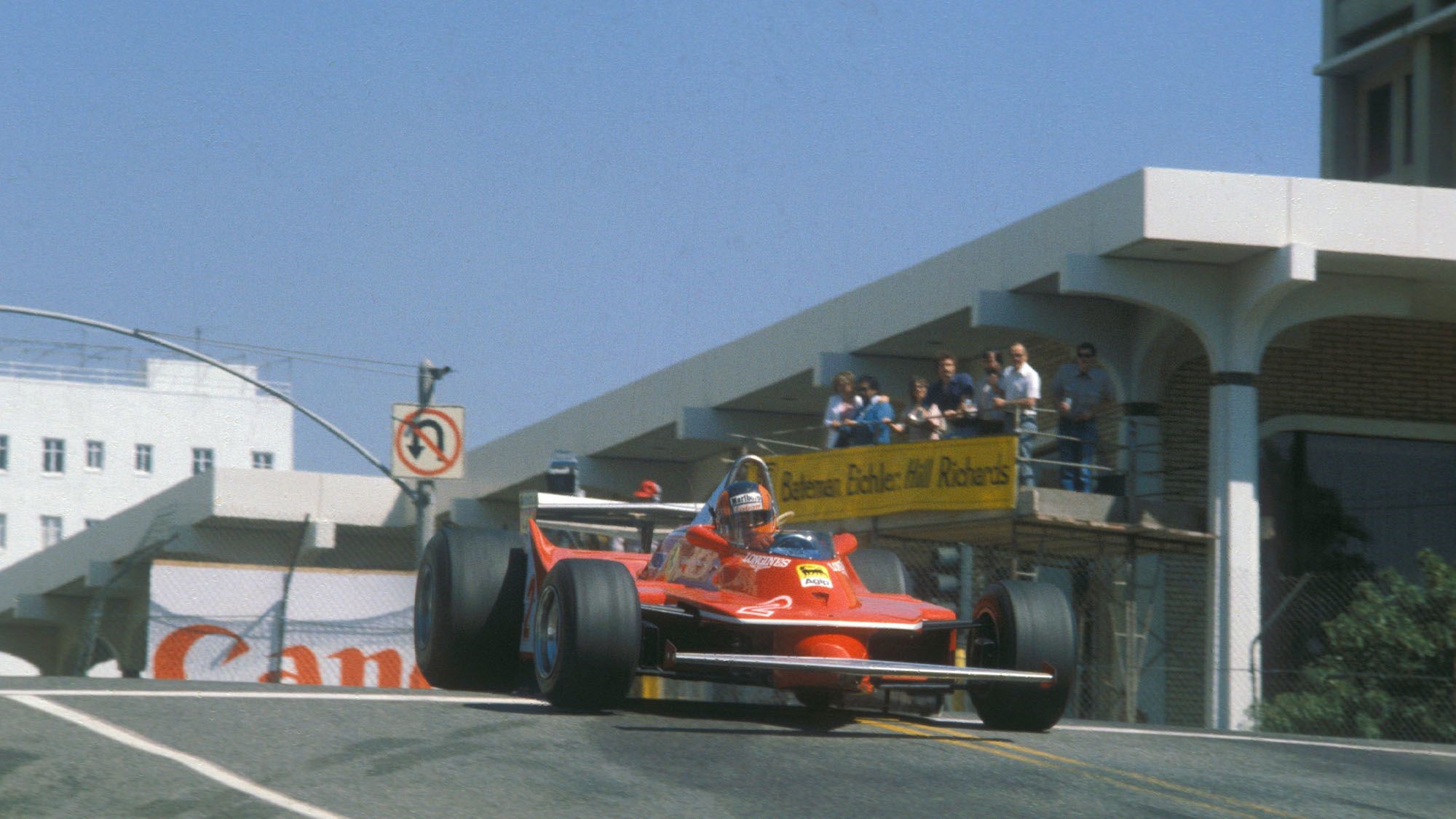

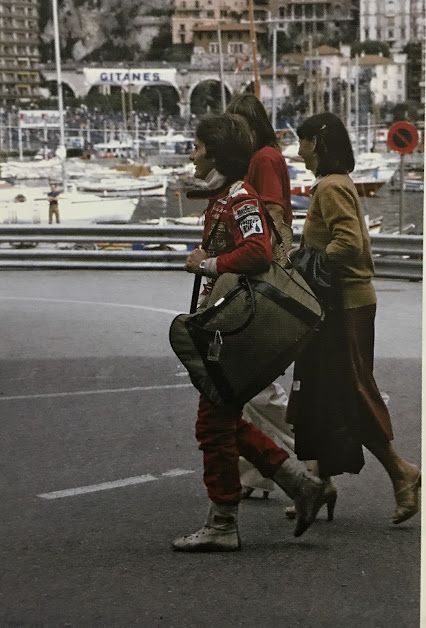

Kimi Raikkonen, Lotus E20 Renault, wore the black helmet design used by James Hunt, world champion in 1976, at the Monaco Grand Prix in Monte Carlo on May 24, 2012. It's not the first time Raikkonen has acknowledged the legacy of Hunt. Copyright: Andrew Ferraro / LAT Photographic.

"In Hunt's time there was greater respect among the drivers. Back then, if you hit someone you could lose your life, because the petrol tanks were placed on both sides of the car. Today, when everything is under the banner of safety, you can do even foolish things. It wasn’t like that back then. We respected each other a lot because everyone knew that life was hanging by a thread. Today, if you cut off a car’s route, nothing happens. The drivers, in those days, spent much more time with each other and they went out together. Certainly that sense of solidarity was the son of the common fear of dying." Kimi Raikkonen

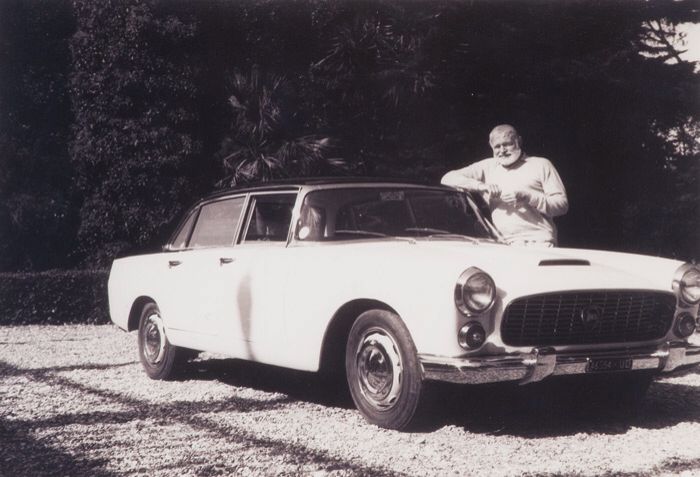

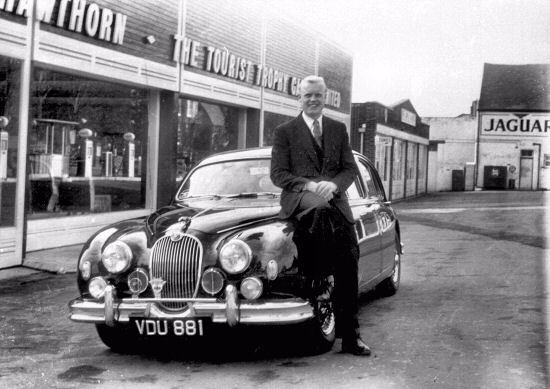

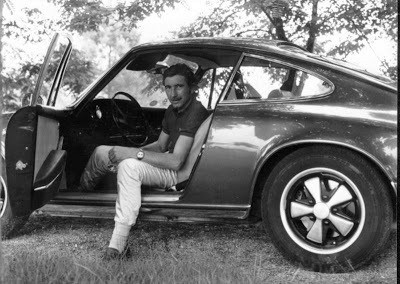

Ernest Hemingway and his Lancia Flaminia.

“There are only three sports: bullfighting, motor racing and mountaineering; all the rest are merely games.” Ernest Hemingway

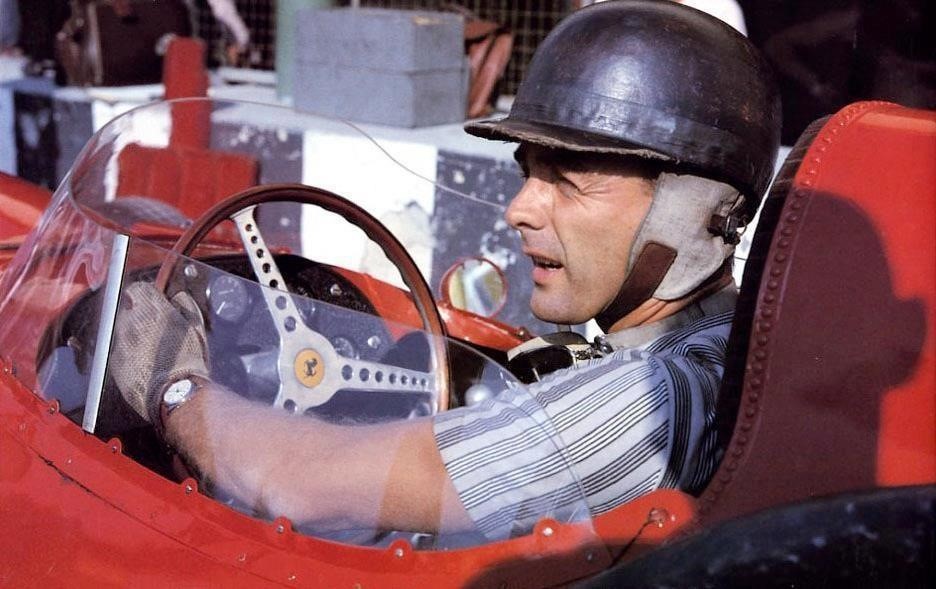

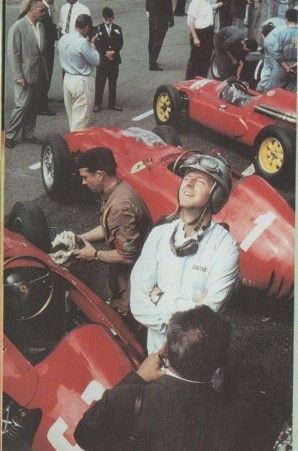

Juan Manuel Fangio in the new Mercedes-Benz W196 streamliner at the French GP in Reims on July 04, 1954. Photos by Louis Klemantaski.

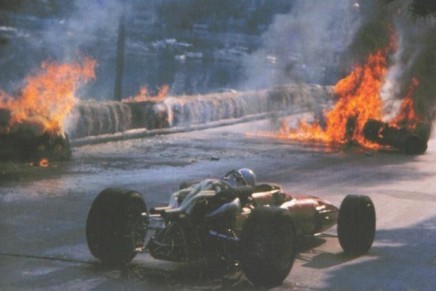

Monaco 1966 crash.

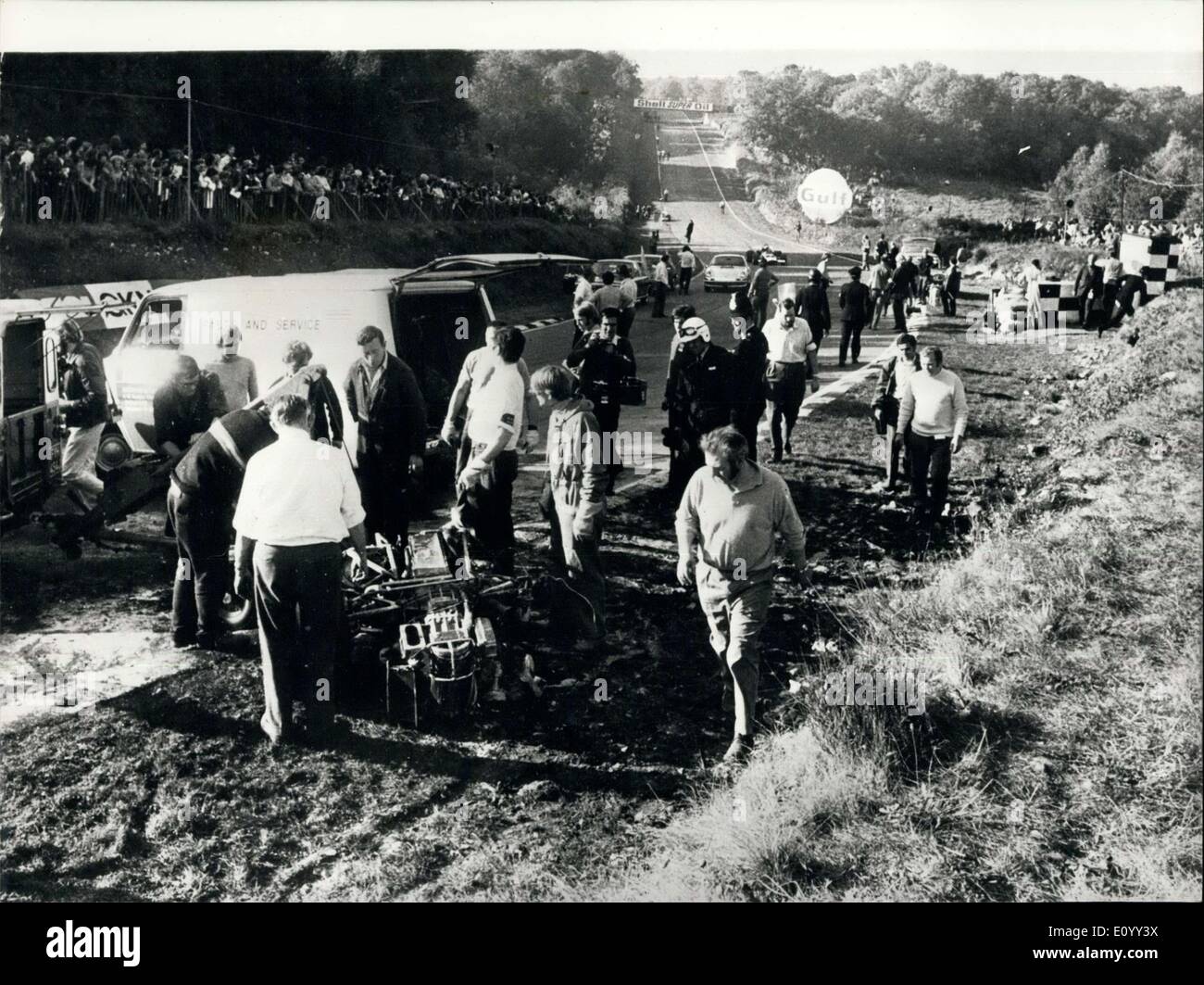

This photo by Trevor Legate that he captured at Brands Hatch in October 1967 shows that roll bars aren’t just for rolling. As I understand it, no injuries.

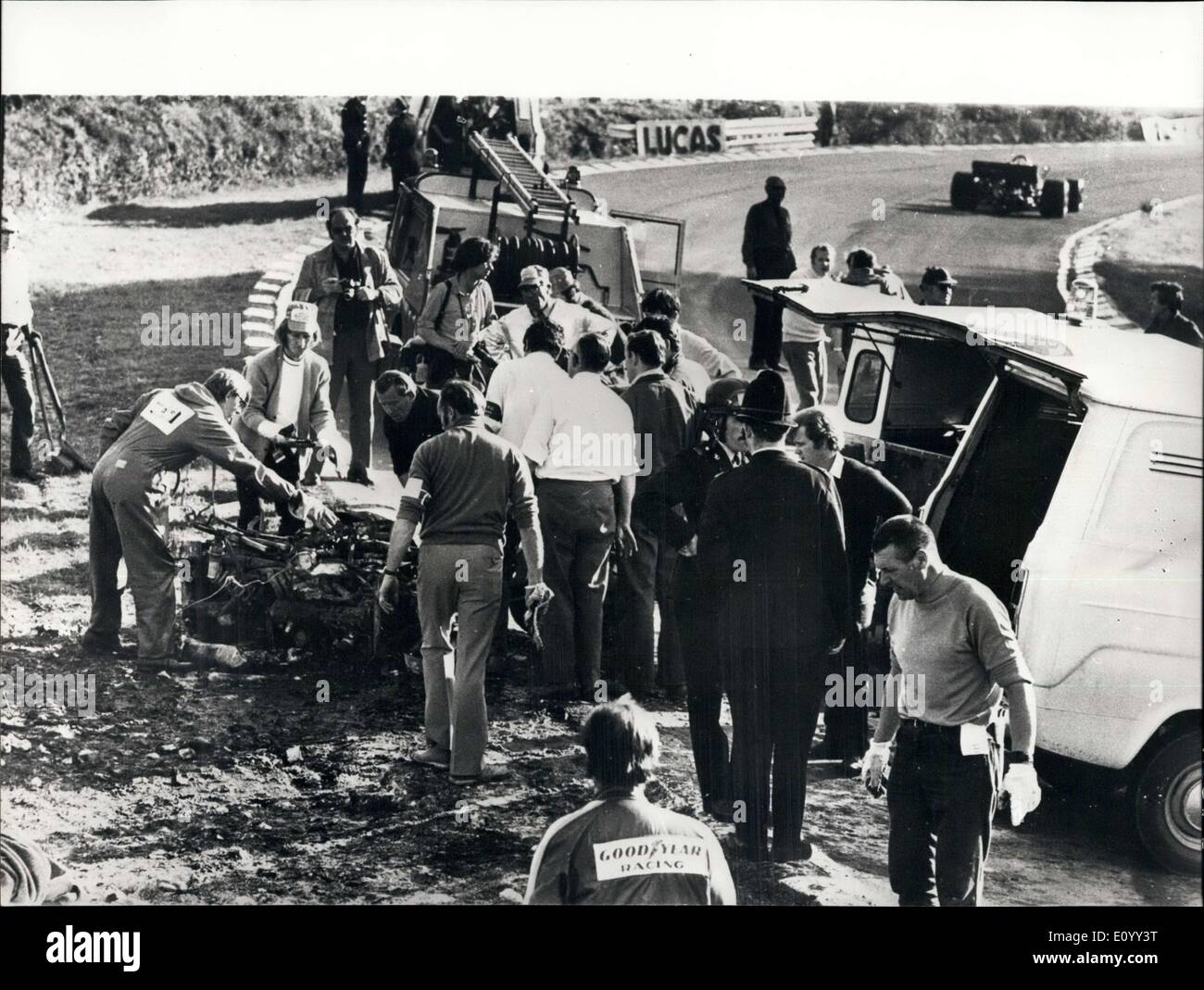

Aftermath of Mauro Bianchi's crash at Le Mans in 1968.

The picture speaks volumes. Racing was a very hazardous profession not too many decades ago. Foto di Nigel Smuckatelli.

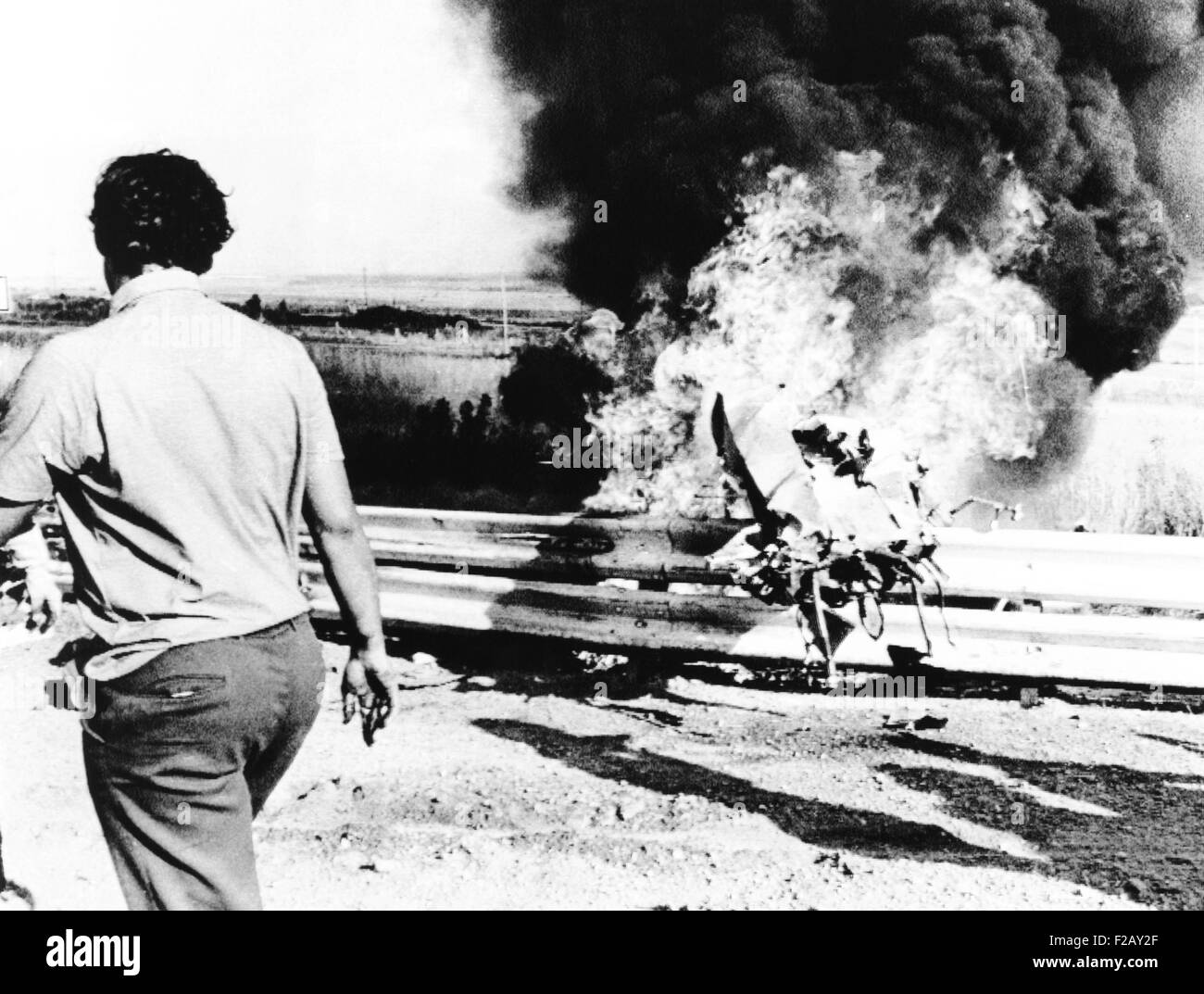

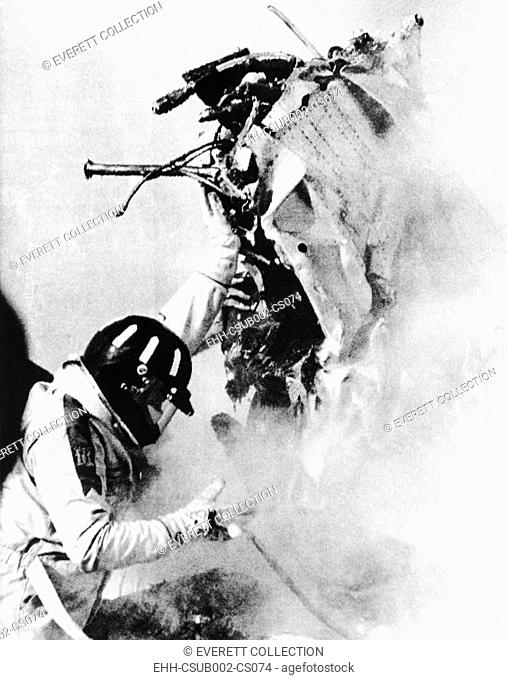

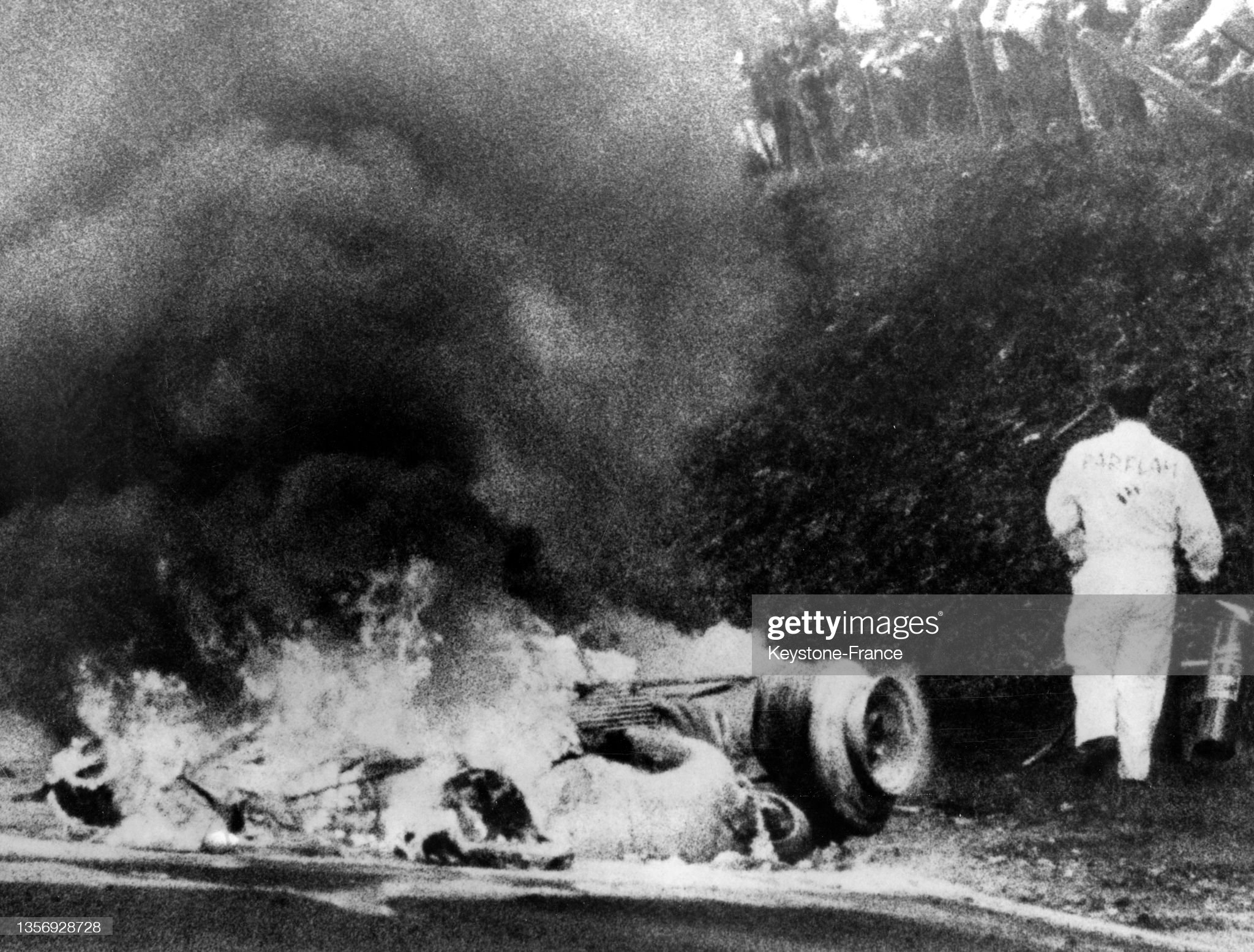

N.2 Ickx’s Ferrari 312B and Oliver’s white BRM P153, inside an inferno. ‘Bag type’ safety bladder fuel tanks mandated from the start of the 1970 season. Unattributed.

Jackie Oliver has punched the release on his Willans 6 point harness and is jumping out of the BRM, Ickx is in the process of popping his Britax Ferrari belts. Johnny Servoz-Gavin’s Tyrrell March 701 Ford 5th passes. Unattributed.

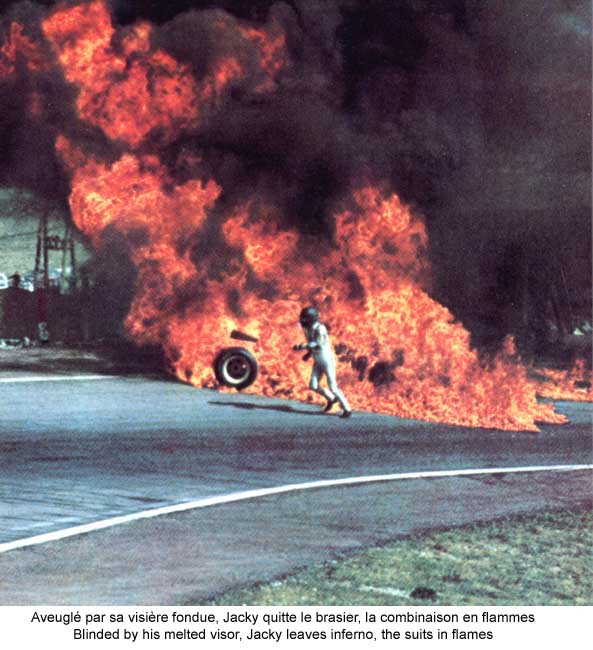

Ickx disoriented and on fire in search of a marshall.

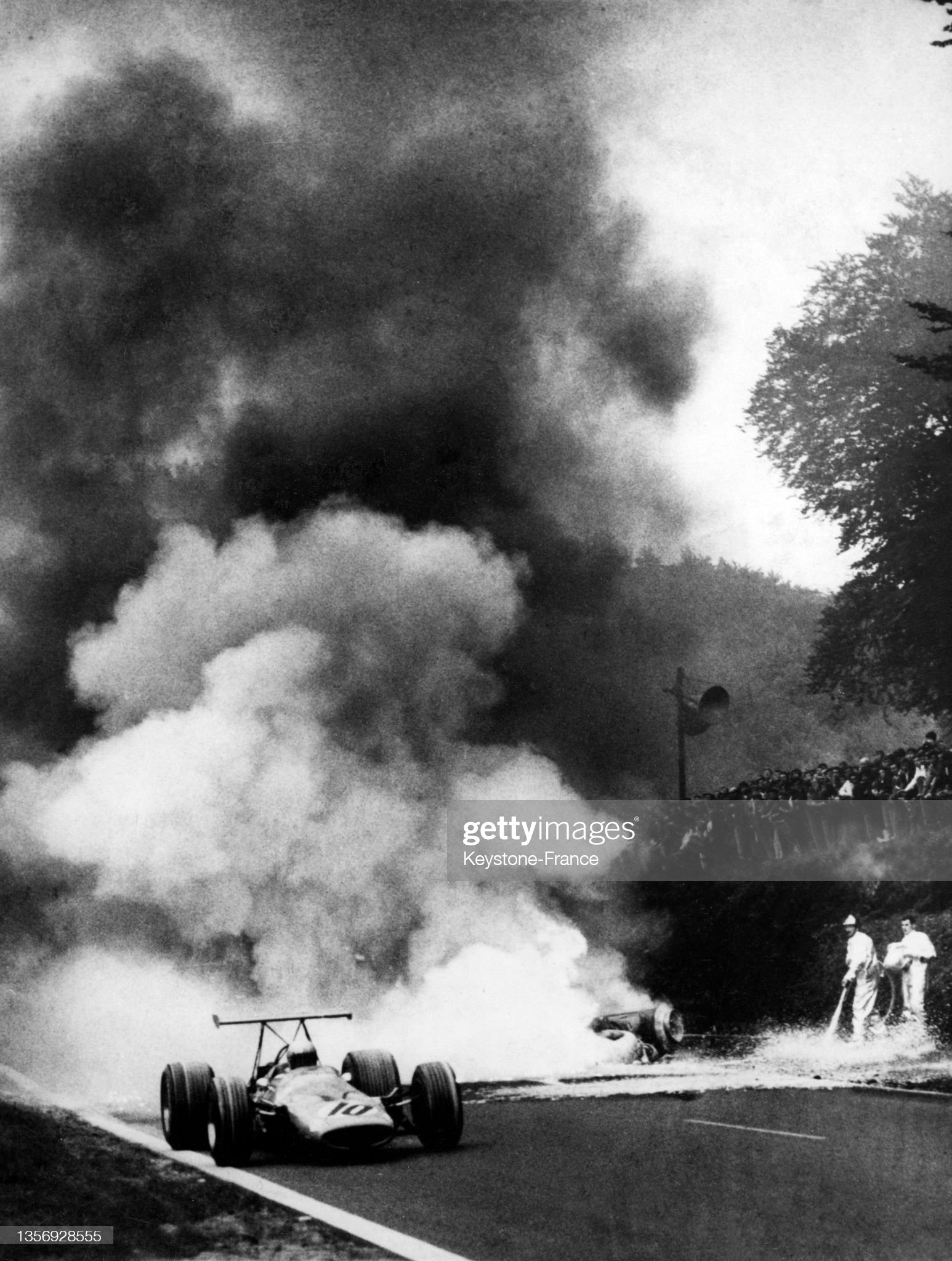

Jackie Stewart, March-Ford 701, GP of Spain, Jarama, April 19, 1970, on his way to victory passes by the flaming debris of the cars of Jackie Ickx and Jackie Oliver. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

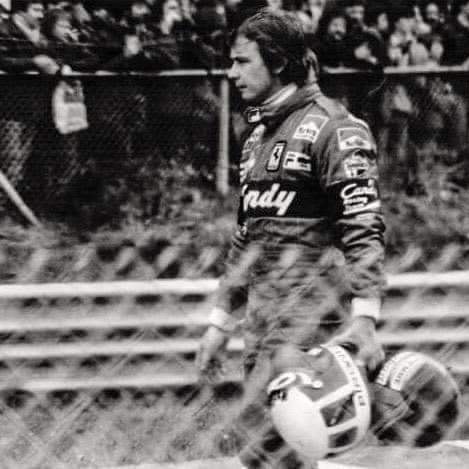

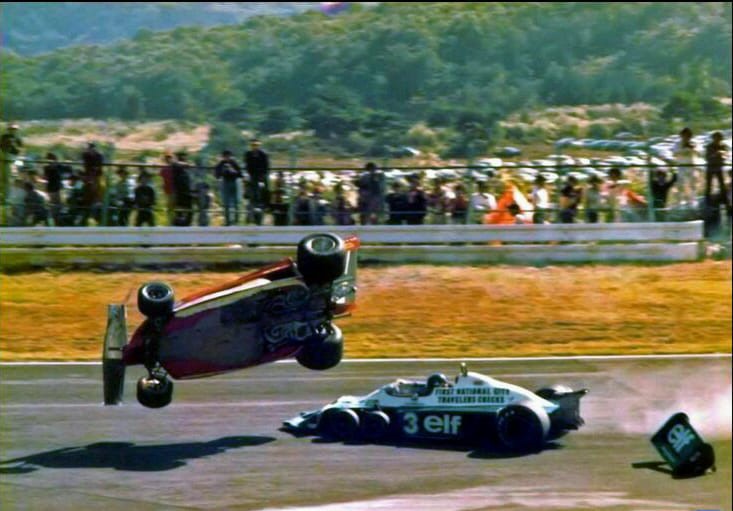

Crash Formula 1, John Watson in a Brabham.

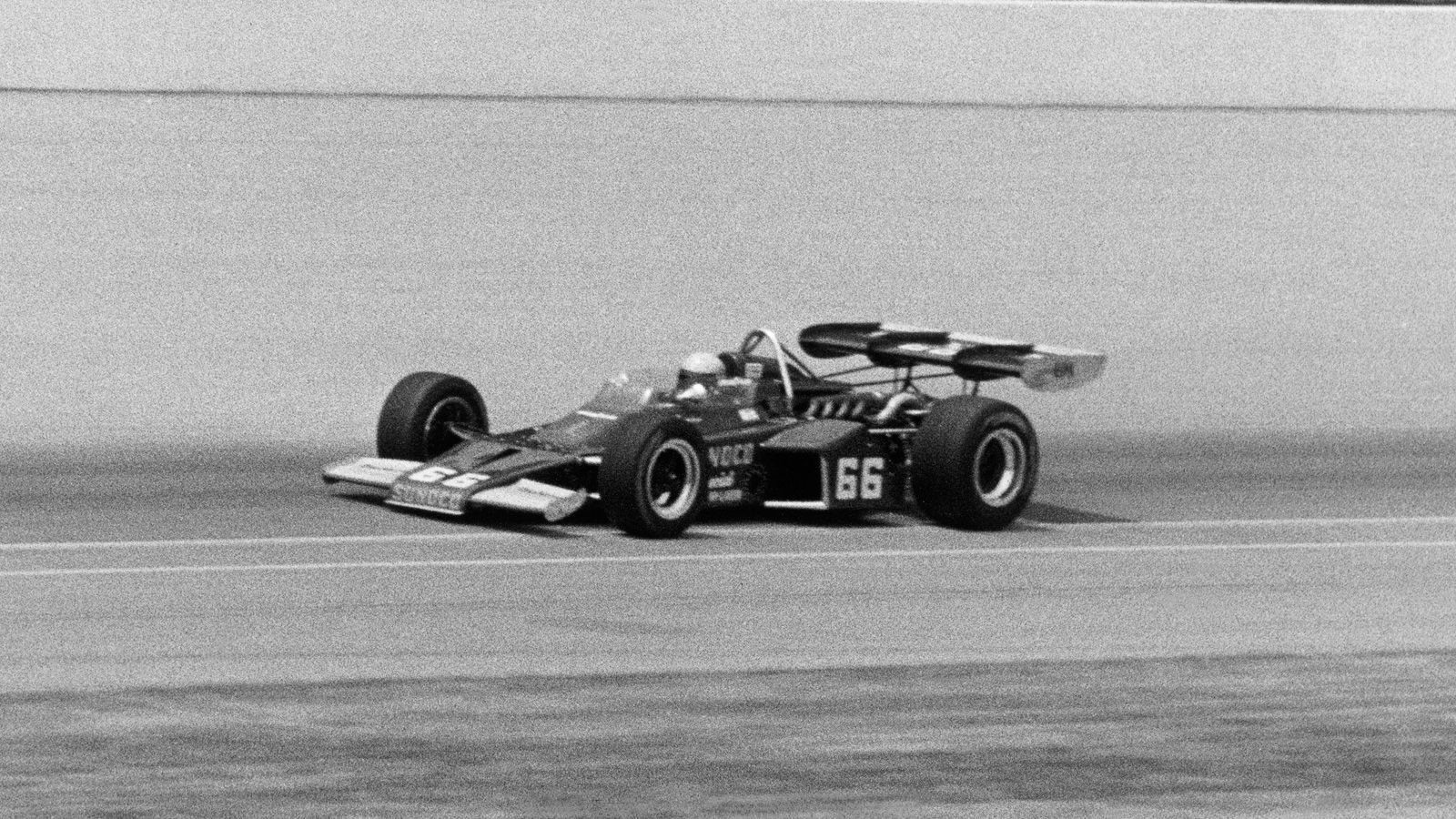

Indy.

Stan Fox.

Perhaps one of the most iconic images of all time as the Mercedes CLR of Mark Webber flips at Le Mans in 1999.

The families of the drivers hit by a violent turn of fate never gave up, never gave up, keeping intimate accounts with pain.

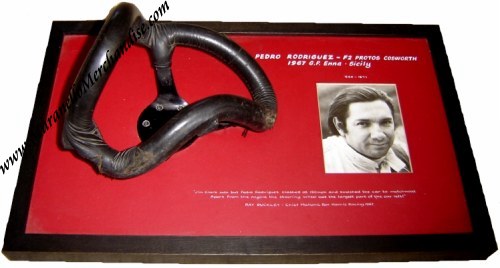

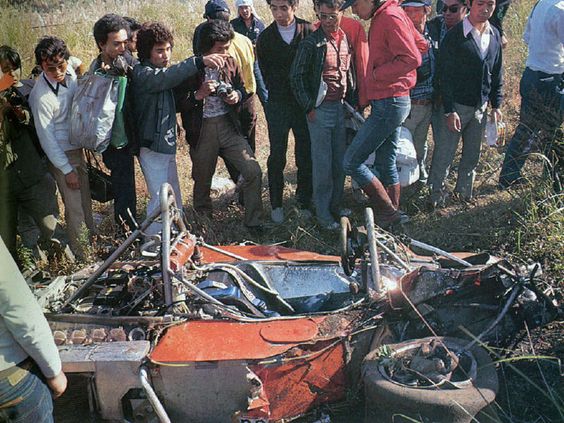

And many have been the deaths of F1 drivers caused by accidents, which occurred during tests or races in Formula 1 or other racing series. Some drivers did not die in their car but a few days or even months after the accident. In addition to those we have talked about on this web site in previous articles, those that we will list in this article and others that we do not mention, we count among the F1 drivers who died tragically Charles de Tornaco, Onofre Marimon, Louis Rosier, Luigi Fagioli, Stuart Lewis-Evans, Giulio Cabianca, Mario Alborghetti, Chris Bristow, Alan Stacey, Carel Godin de Beaufort, John Taylor, Bob Anderson, Helmuth Koinigg, Riccardo Paletti and Jules Bianchi, who sadly closes the list. Our fond memories and thanks go to all of them for sacrificing their lives on the racing altar.

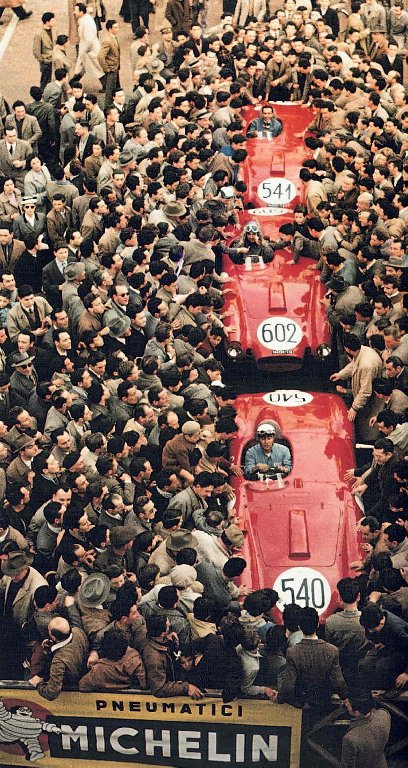

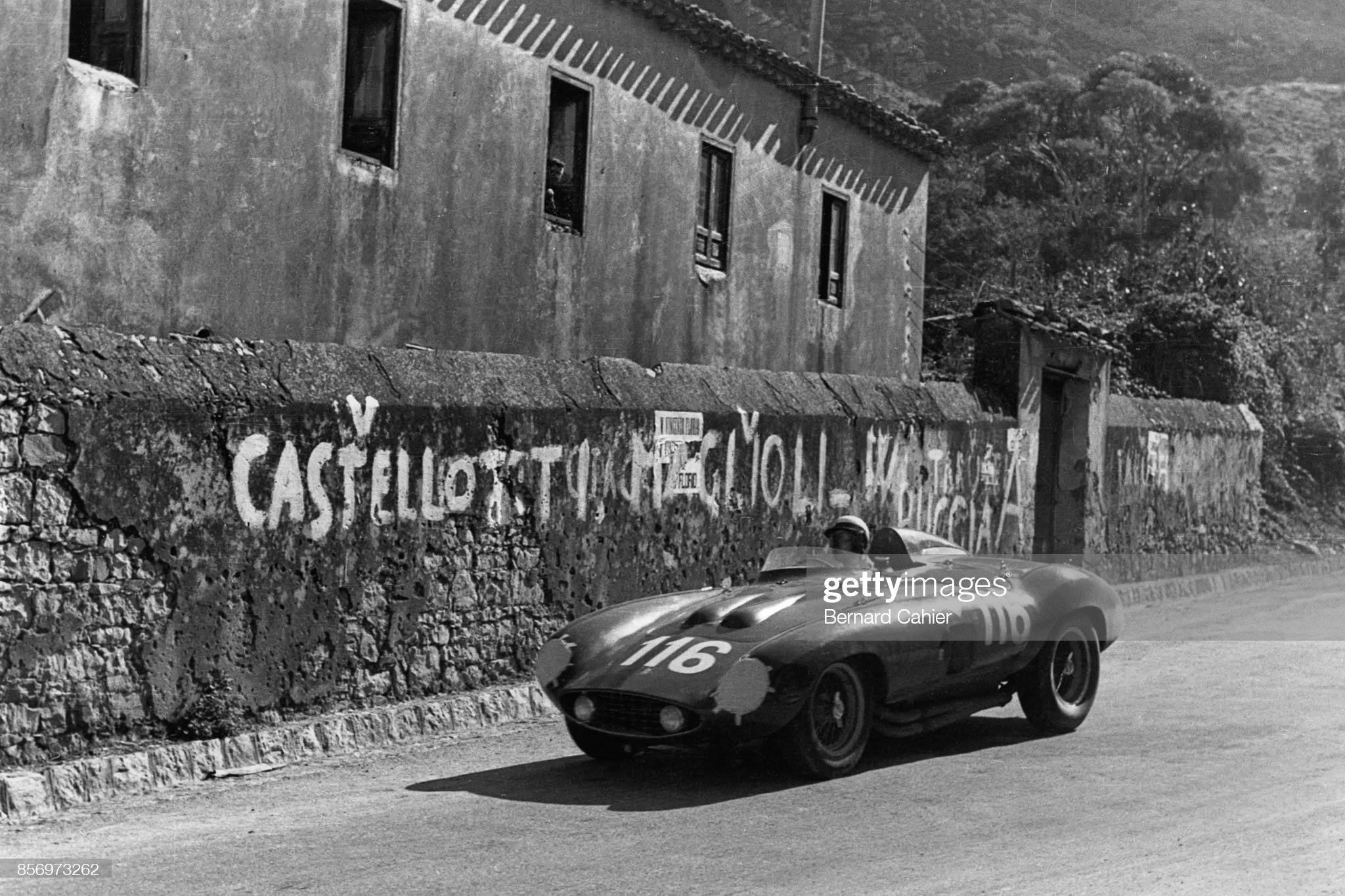

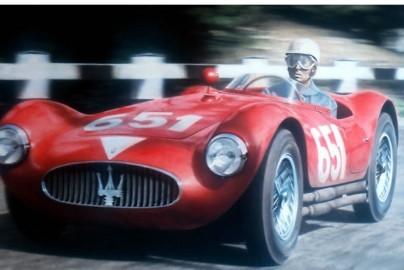

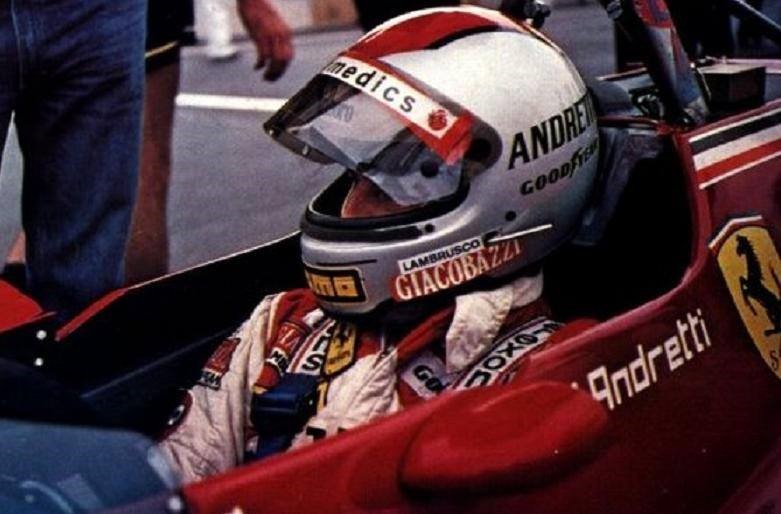

The deeds of some of these daring drivers who died tragically - and precisely Castellotti, de Portago, Musso, Collins and Hawthorn - have been admirably described by Luca Delli Carri in his book “The undisciplined: living and dying in a Ferrari: five stories of young drivers". At the time of the facts mentioned in the book, Fangio asked for a salary that the Commendatore "cannot" pay him (12 million) and "emigrated" for his last World Championship to Maserati which, however, will close the Racing Department two years later. Without a real team leader, Ferrari drivers are free to race for themselves. Four of them lost their lives, with the only Hawthorn able to bring the world championship laurel crown to Maranello. The world title will be the last for a pilot driving a single-seater with a front engine. Thus Delli Carri writes of that period. “Half a century ago, in a handful of years between 1957 and 1959, five young Ferrari drivers lost their lives in their car. Their names still live today in the memory of some and in the imagination of many. They were called Eugenio Castellotti, Alfonso de Portago, Luigi Musso, Peter Collins, Mike Hawthorn. They were great, better than their cars. They were bold, they snubbed fear. An Italy insatiable of heroes worshiped them, waiting for them for hours on the side of the roads. They darted like missiles, simply risking everything behind the wheel of a vehicle that was much more powerful than safe, launching the car towards that breaking point that was not related to the engine but to the sum of circumstances that we usually call fatality. This search for a contact with fate, the race at three hundred kilometers per hour following the unexpected, gave them a precious and inimitable aura, detached them from the ground and made them visible to the crowds. And to the crowds they also appeared beautiful, as well as damned. Superb women surrounded them, to be loved and abandoned, but in any case to conquer themselves a biographical note on the sidelines of their lives. In contemplating their luck and their beauty, but above all in evaluating the madness price paid for them, the spectators transformed motoring into a mass sport: because the distance of the normality of the people from all this made the daily life of the excluded perfectly understandable, habitable, shareable. Still, the five young heroes had a daily life of their own, just as the accidents that led to their death have a technical explanation. The book speaks of this background and of nothing else. It does not attempt only an academic reconstruction of the human side of the drivers, nor does it limit itself to investigating the dynamics of those disasters. Looking for the traces of people in the rubbles of the characters, “Gli indisciplinati” also tries to analyze that myth-making process that, in the world of motors, created from the beginning immense and ephemeral champions. And it wonders about the role that, in the construction / destruction of these fragile Gods, had the most unfathomable of men: Enzo Ferrari.”

We too want to pay tribute to all these wonderful men who have made us love Formula 1 and Ferrari so much, in the hope that their extreme lives can be a lesson for all of us.

Alberto Ascari

Ascari used to go by car with a friend on the Milan-Como road, but only when there was fog, to test his reflexes, causing great fear in his friend.

The son of one of Italy's great pre-war drivers, Alberto Ascari went on to become one of Formula One racing's most dominant and best-loved champions. By Gerald Donaldson.

Noted for the careful precision and finely-judged accuracy that made him one of the safest drivers in a most dangerous era, he was also notoriously superstitious and took great pains to avoid tempting fate. But his unexplained fatal accident - at exactly the same age as his father’s, on the same day of the month and in eerily similar circumstances - remains one of Formula One racing’s great unsolved mysteries.

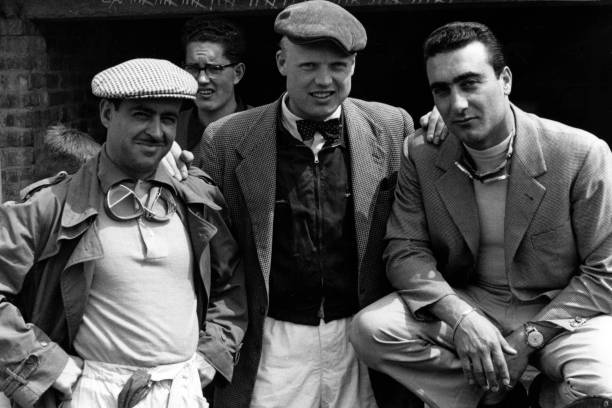

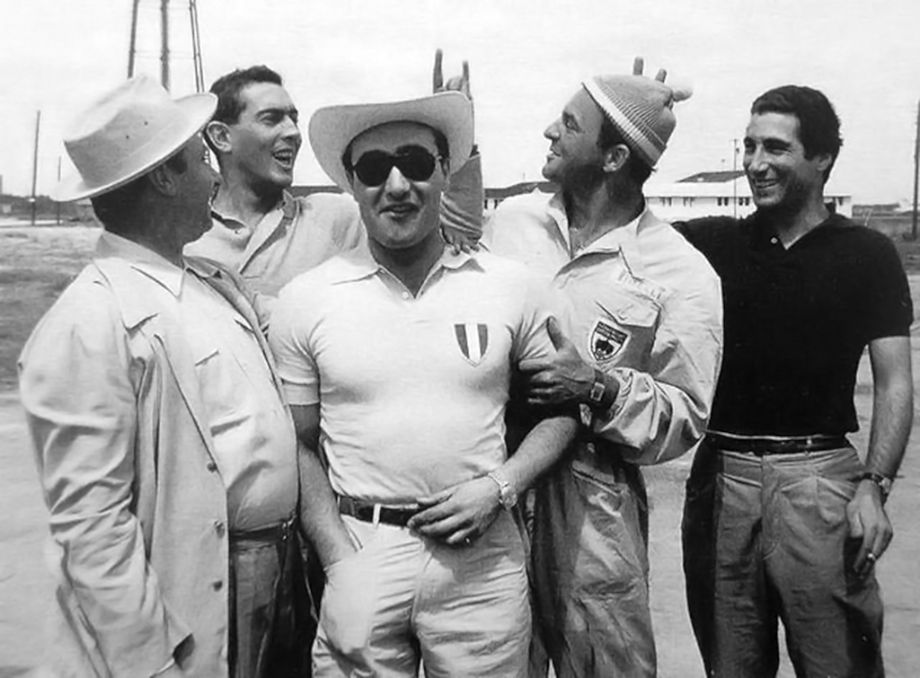

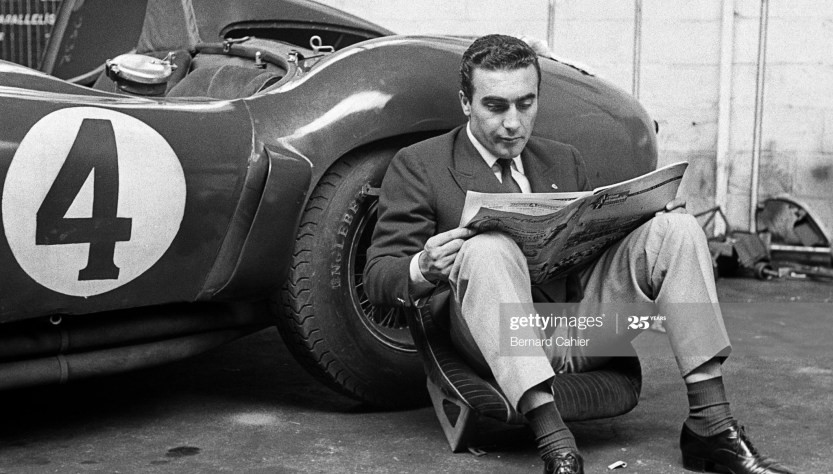

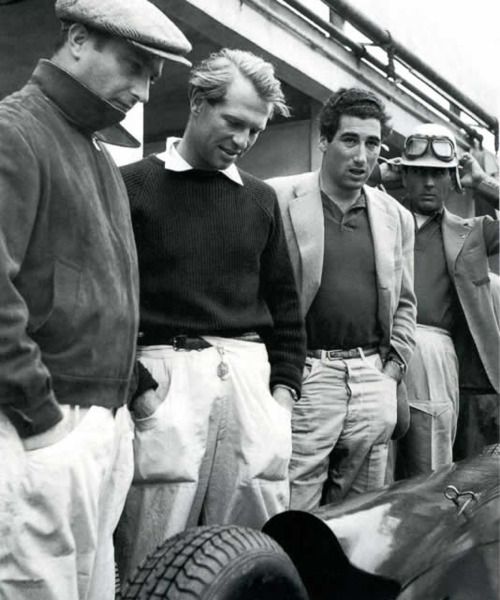

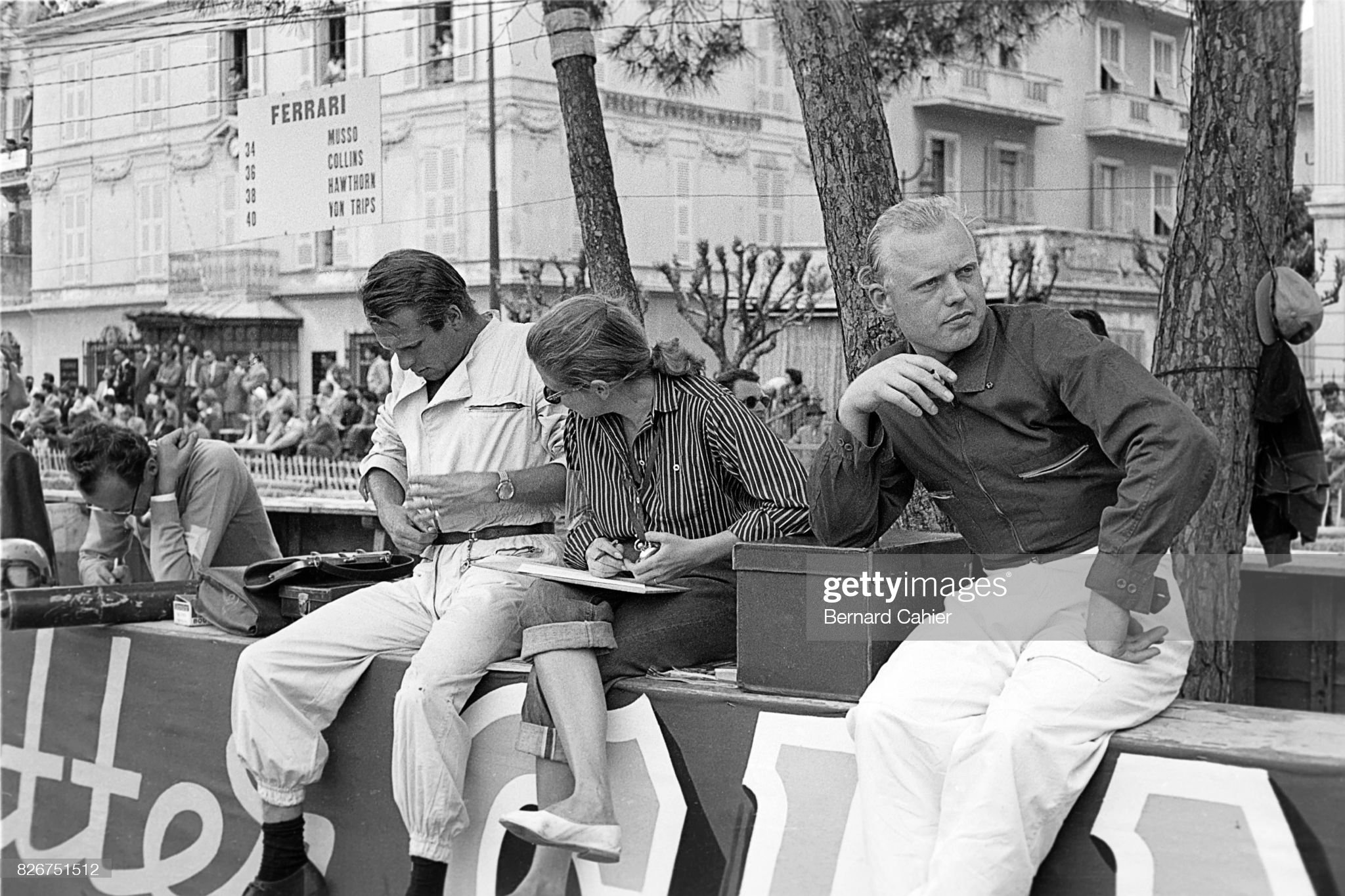

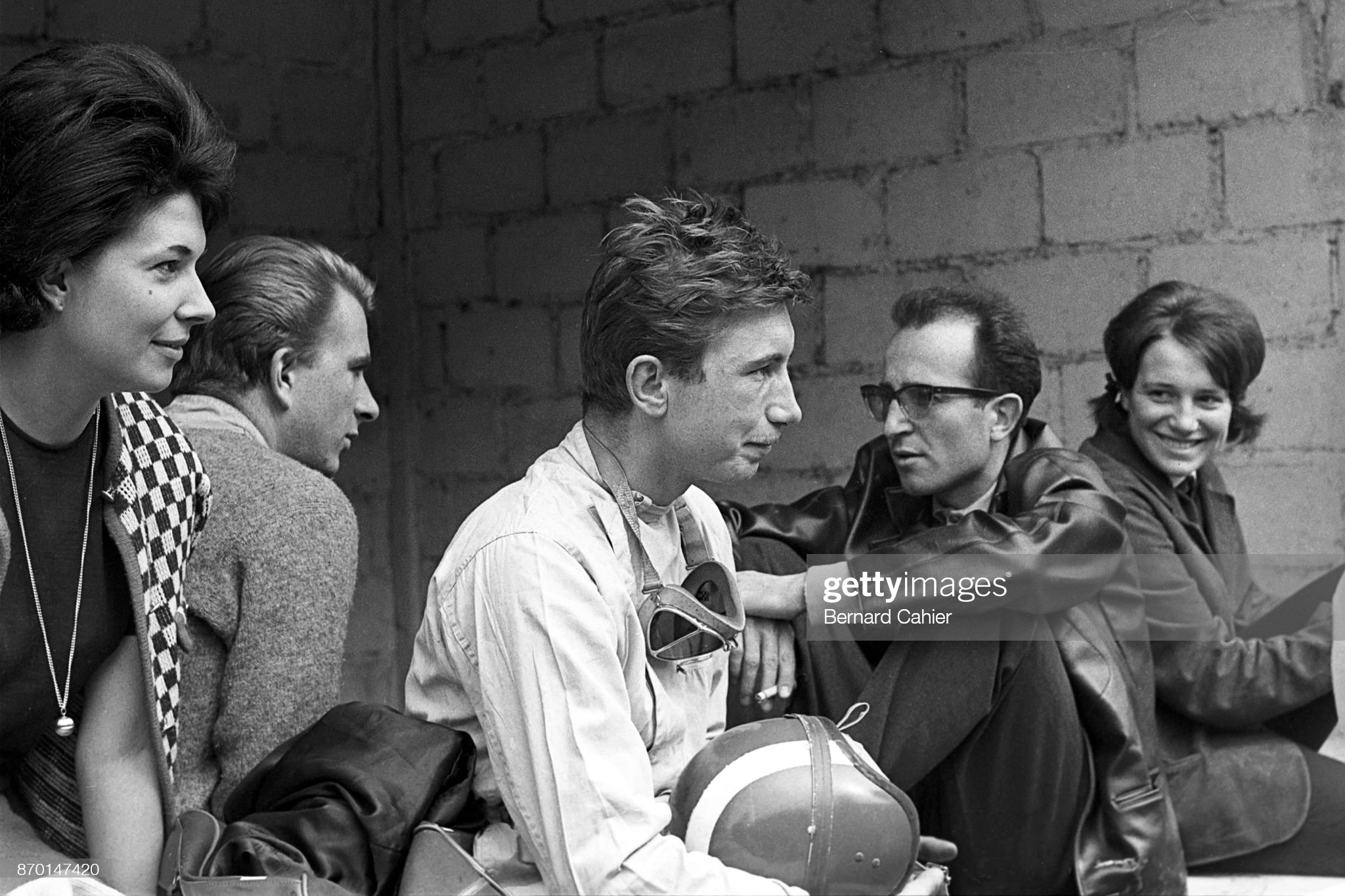

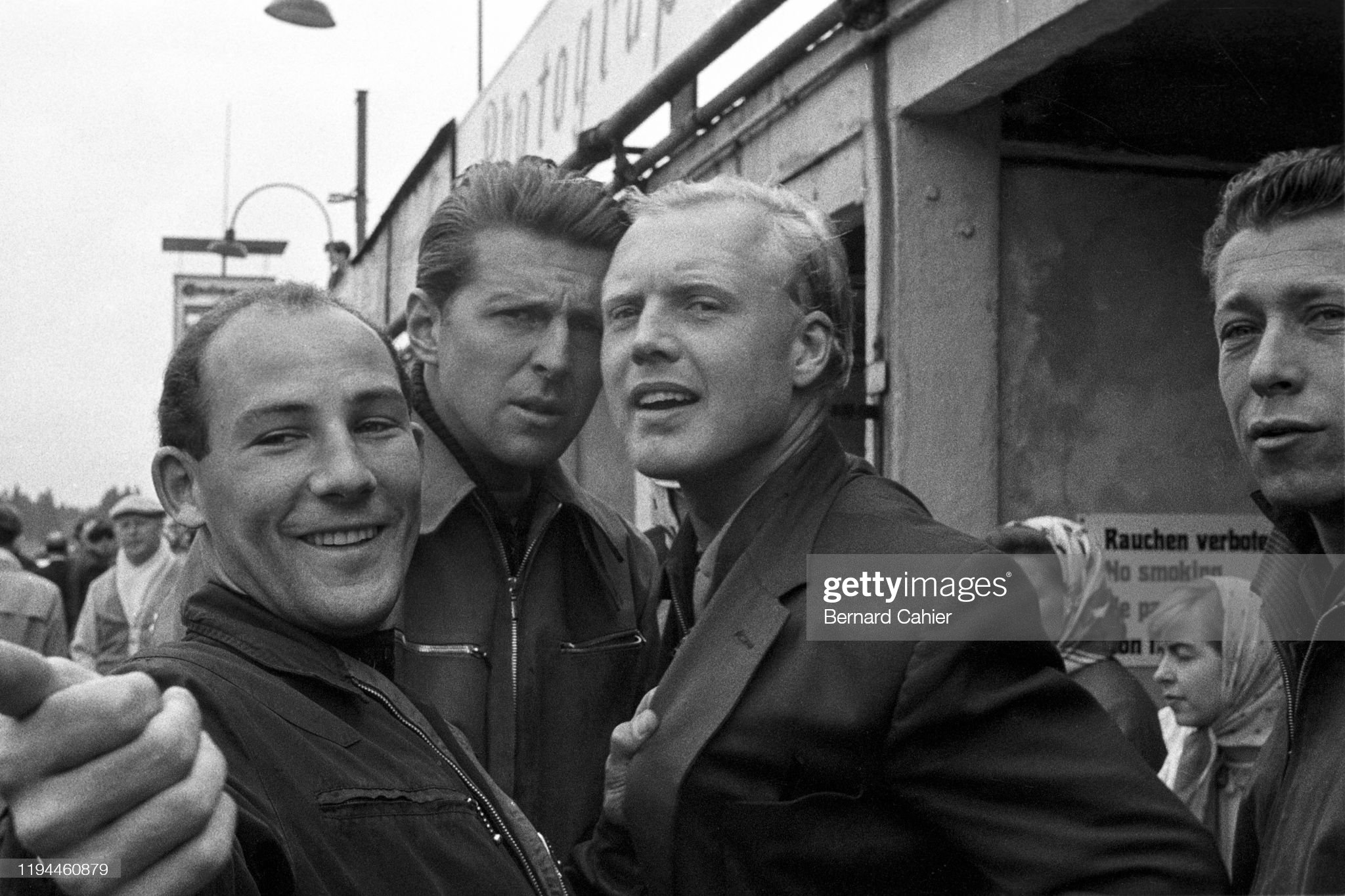

Silverstone, July 1953: the four Ferrari drivers discuss tactics ahead of the British Grand Prix, along with French journalist / photographer Bernard Cahier. From left: Alberto Ascari, Guiseppe Farina, Bernard Cahier, Mike Hawthorn and Luigi Villoresi. Credit: Sutton Images.

Silverstone, October 1948: from the pre-world championship era – Alberto Ascari on his way to second place in the British Grand Prix. Maserati team mate Luigi Villoresi won the race. Credit: Sutton Images.

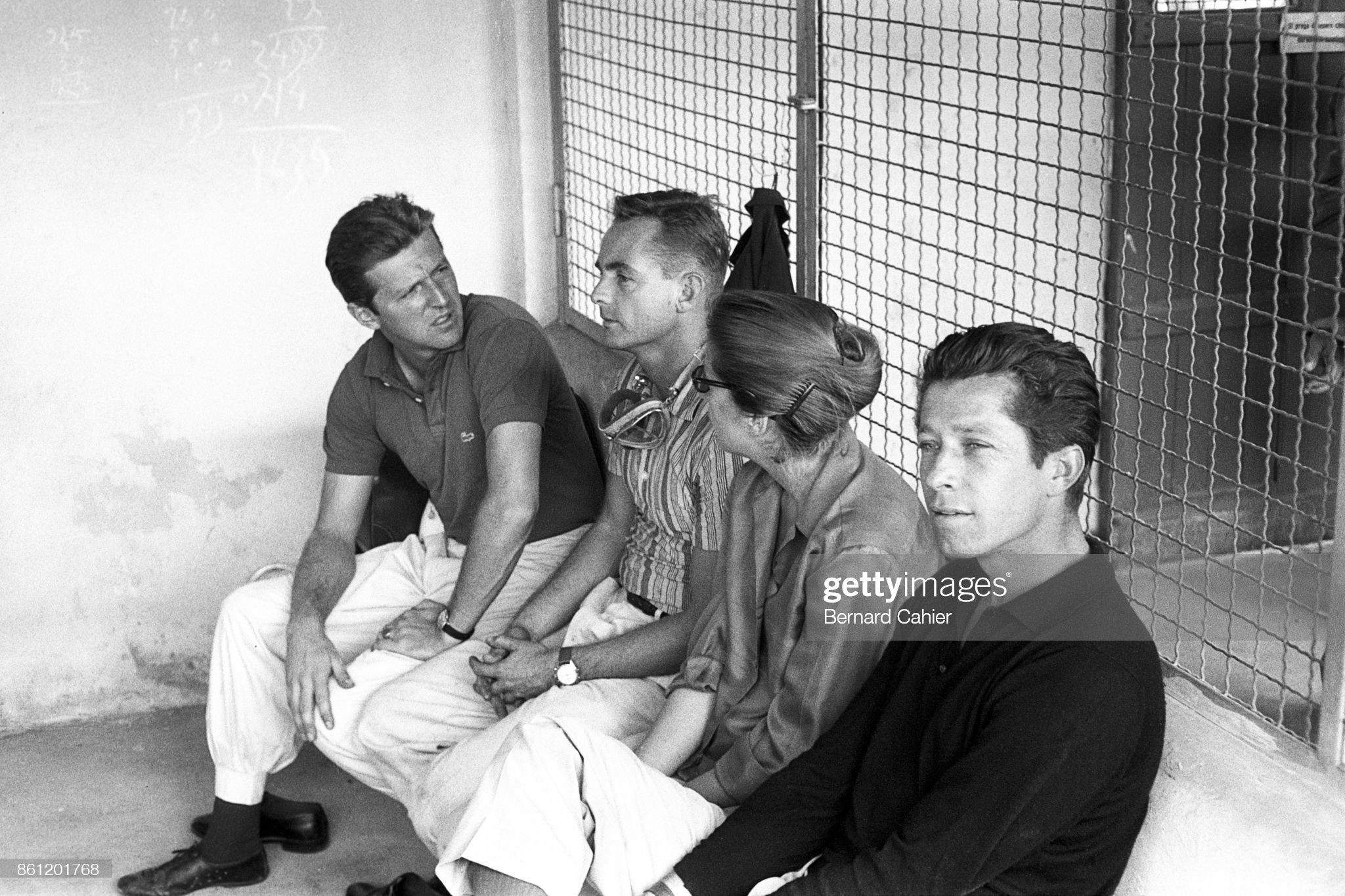

Silverstone, July 1952: Ascari’s British Grand Prix victory was the third in a nine-race winning run for the Italian. Here he chats with fellow Ferrari drivers Piero Taruffi, left and Giuseppe Farina, centre. Credit: Sutton Images.

1952: Alberto Ascari at the wheel of the Ferrari 500 on the way to the first of his two world championships. Credit: Sutton Images.

Silverstone, July 1953: reigning champion Alberto Ascari prepares for qualifying at the British Grand Prix. He went on to take pole position in his Ferrari 500 from the Maserati of Jose Froilan Gonzalez. Credit: Sutton Images.

Alberto Ascari with his father Antonio.

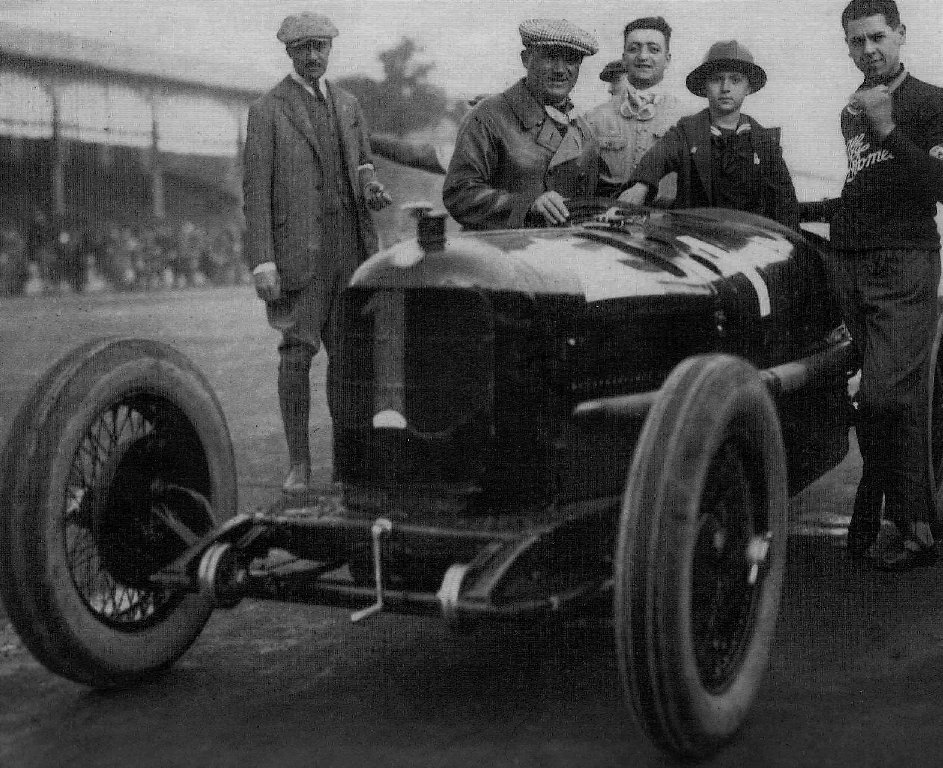

October 10, 1924, Antonio Ascari, Alfa Romeo P2.

Antonio Ascari in an Alfa Romeo P2 in 1925.

Alberto Ascari, born in Milan on July 13, 1918, was just seven years old when his famous father Antonio, the reigning European champion, was killed while leading the French Grand Prix at Montlhery.

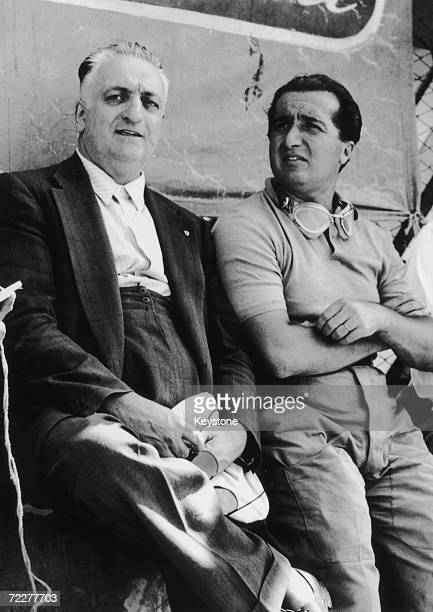

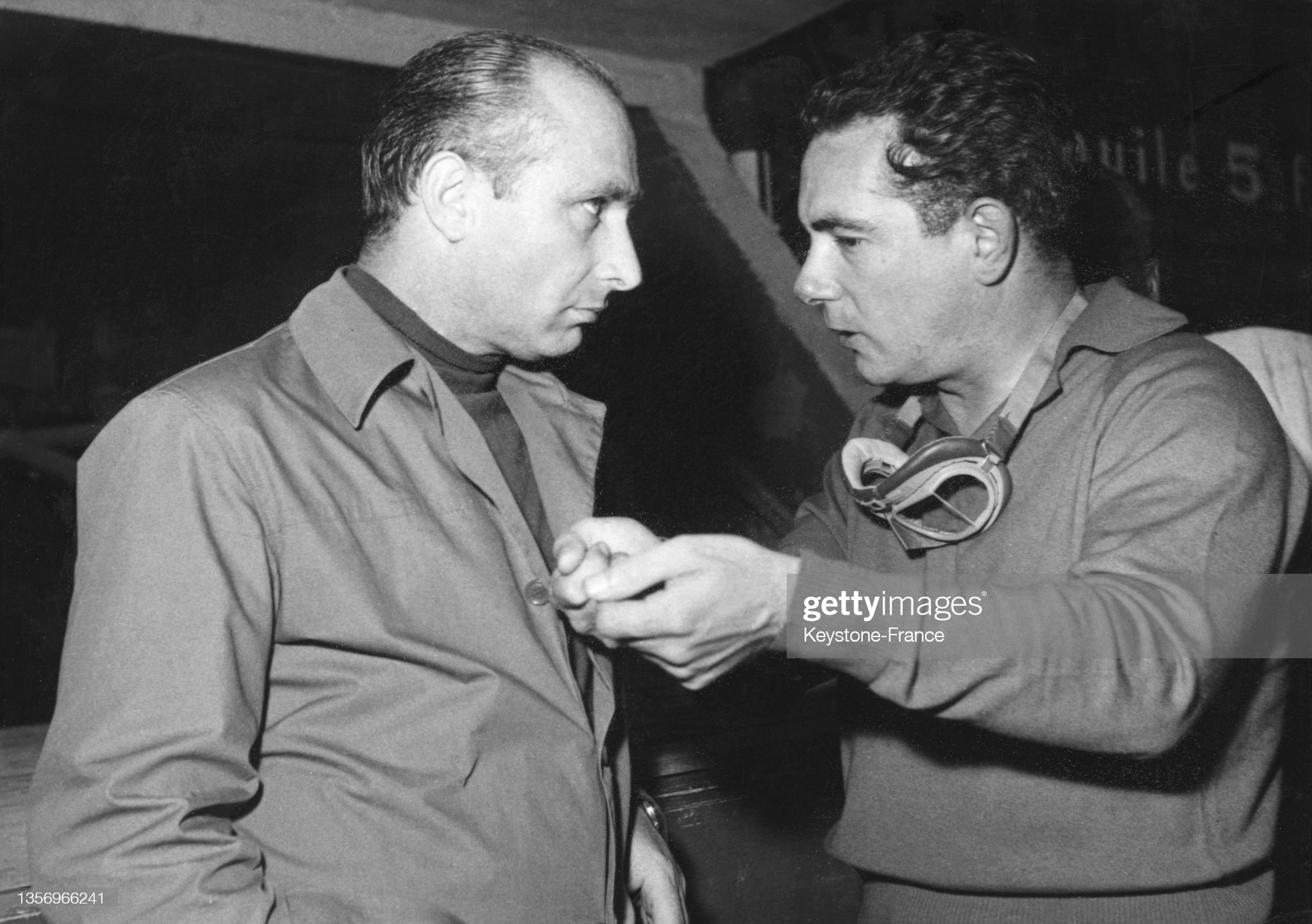

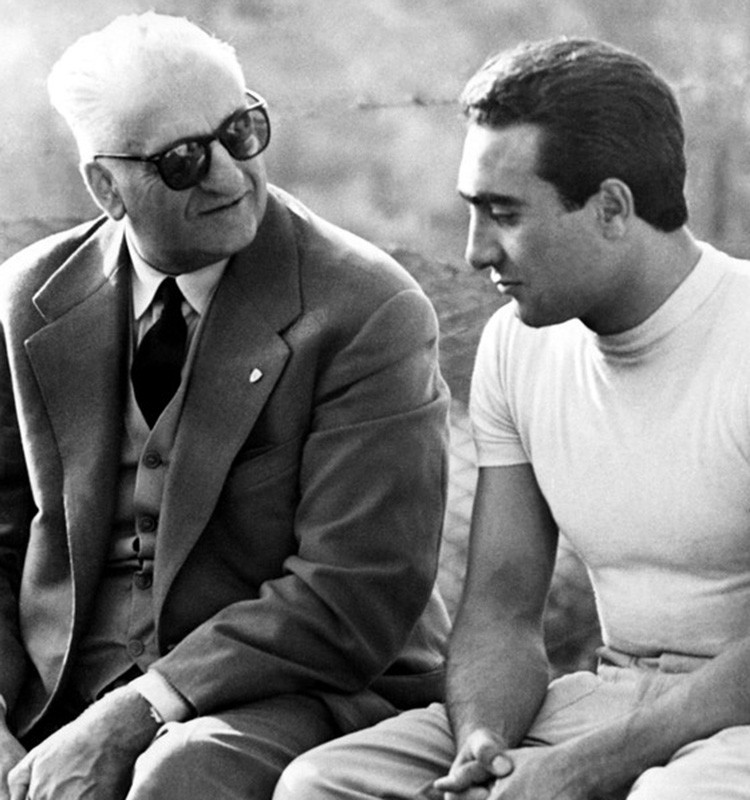

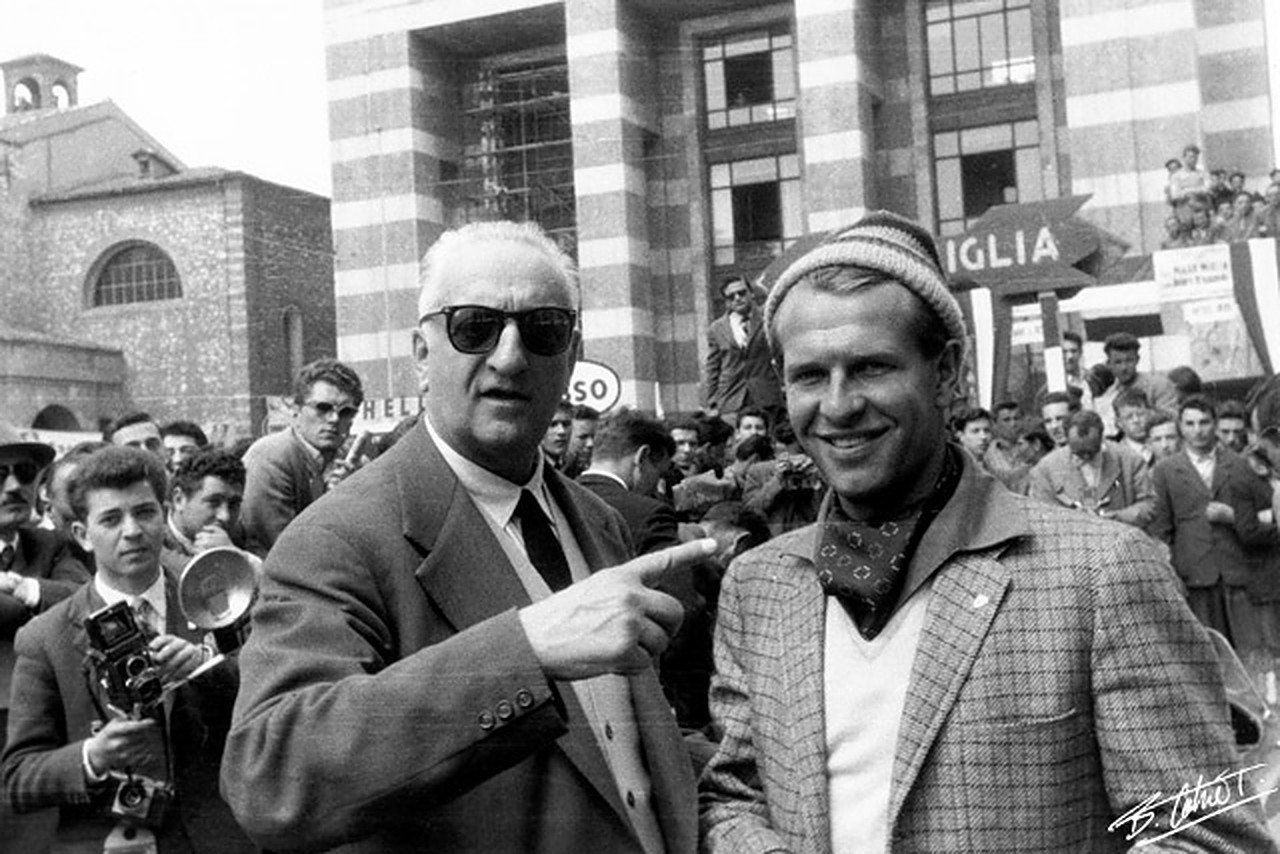

Enzo Ferrari, (left) and one of his drivers, Alberto Ascari talk over their strategy for the Italian Grand Prix in the pits at Monza, 1st September 1950. Photo by Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

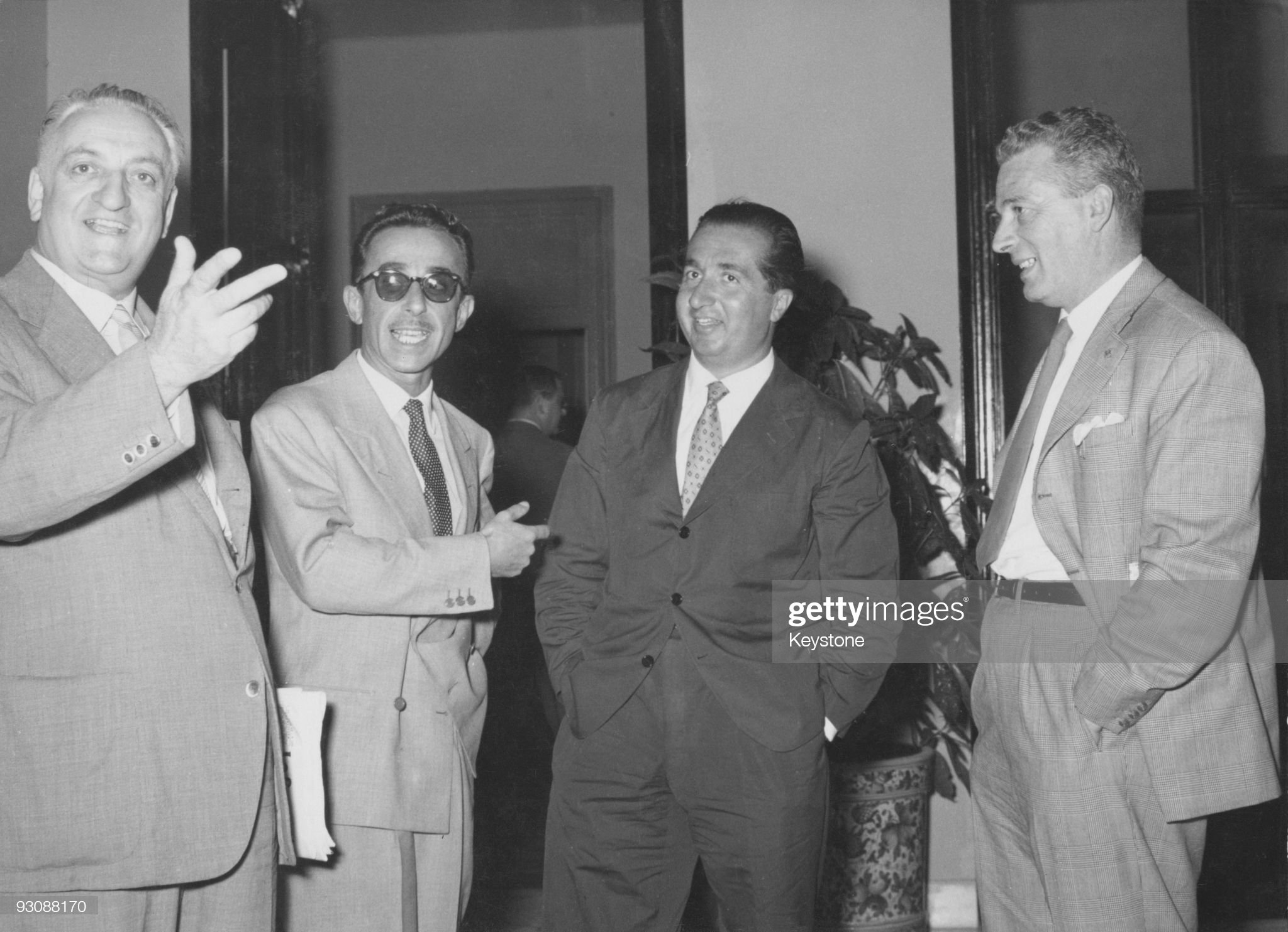

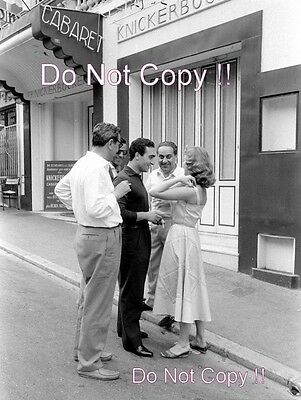

Gigi Villoresi, Enzo Ferrari and Alberto Ascari around 1953. Photo by Keystone – France / Gamma - Keystone via Getty Images.

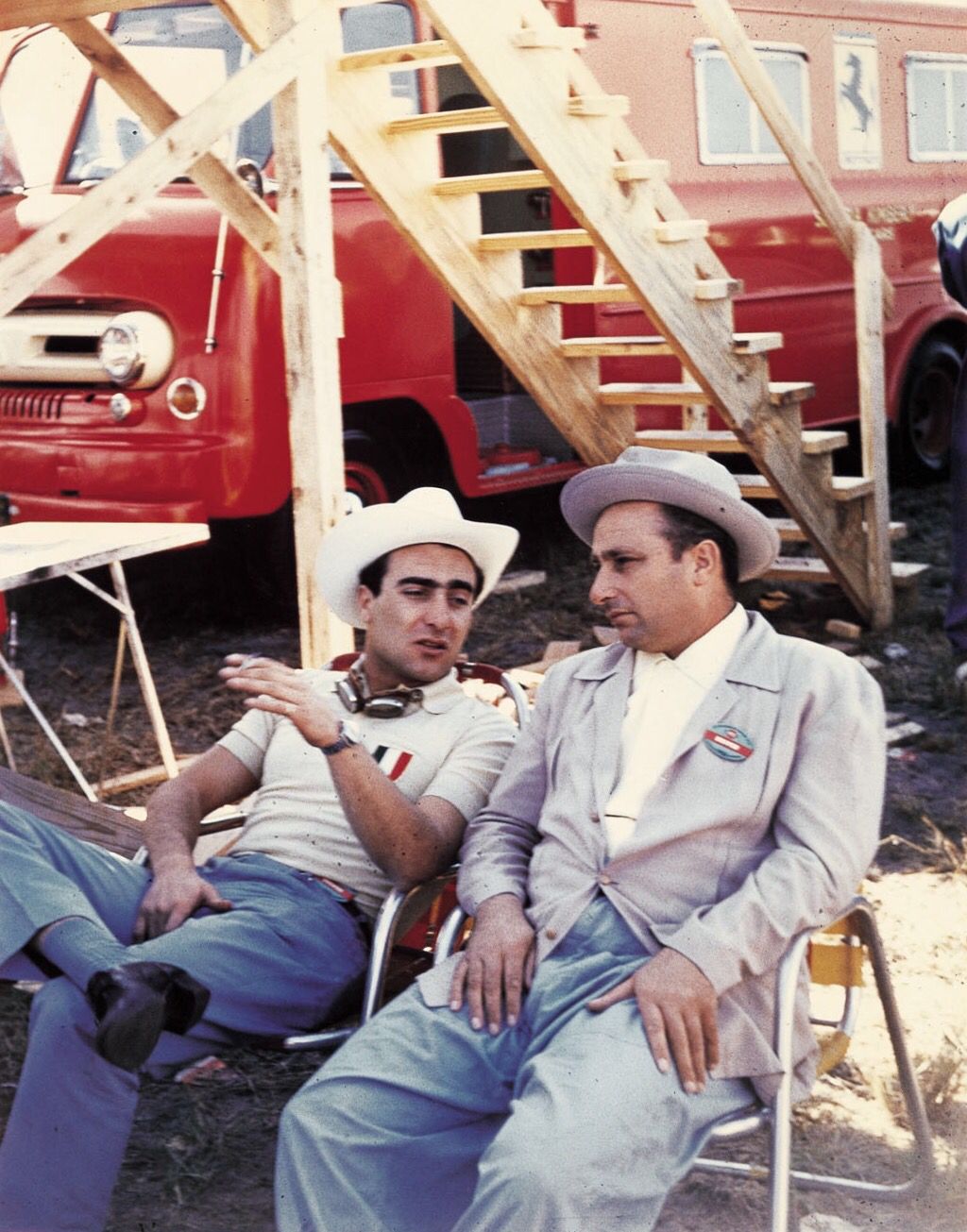

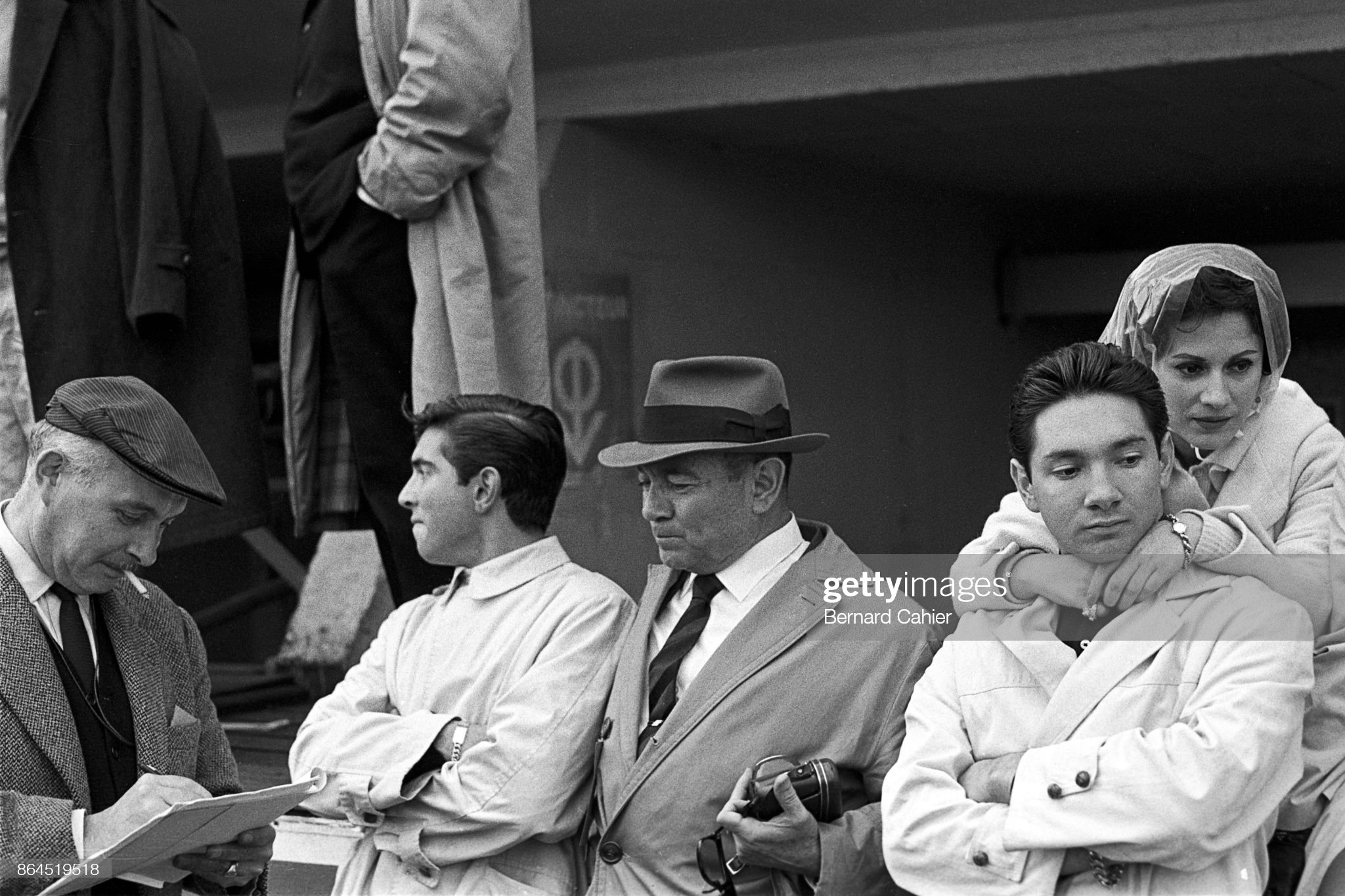

Enzo Ferrari meets up with champion racing driver Alberto Ascari at a hotel in Salsomaggiore Terme, Italy, 28th August 1954. They are discussing Ascari's potential participation in the upcoming Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Ferrari is on the left and Ascari is second from the right. Photo by Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

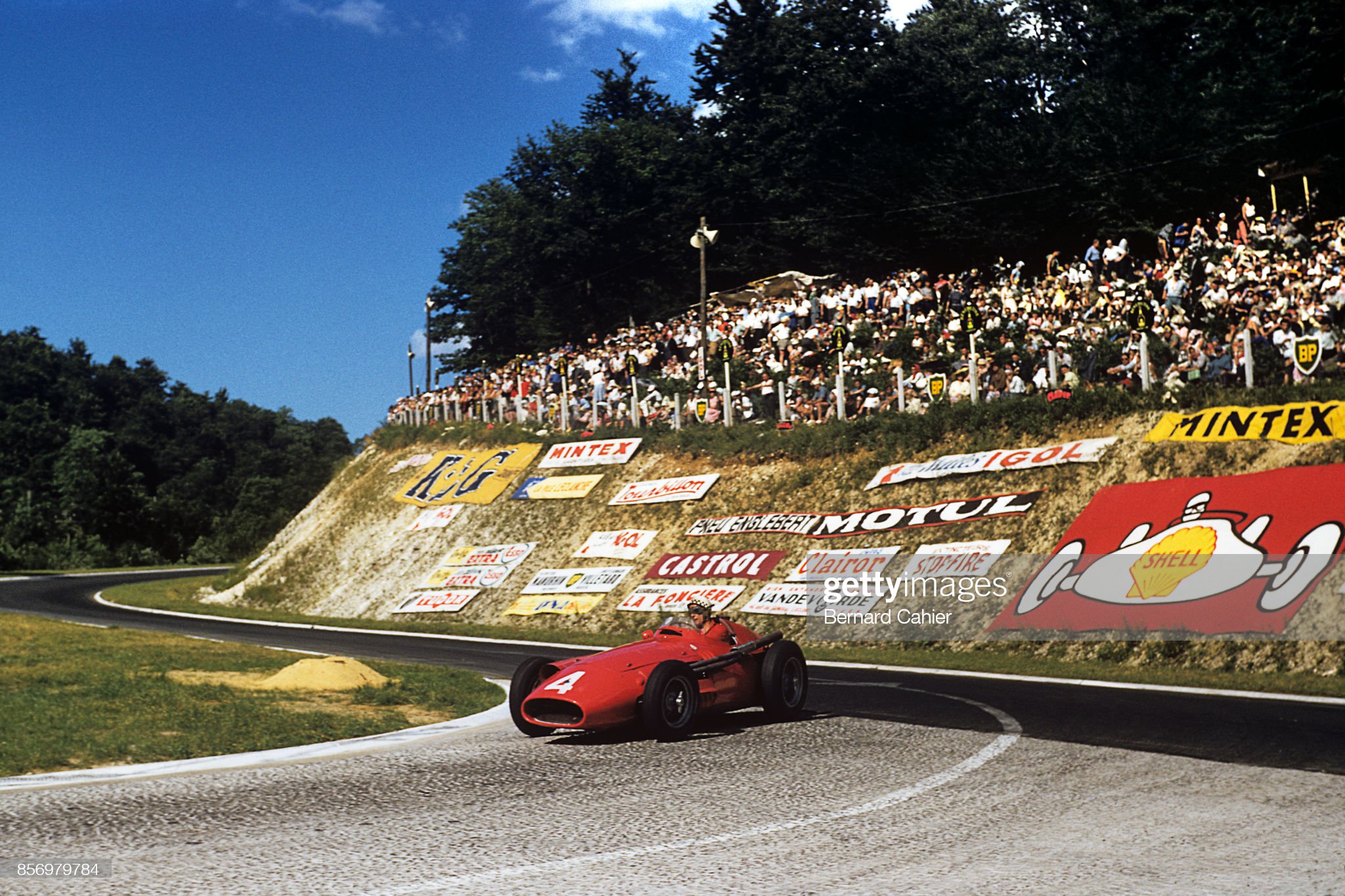

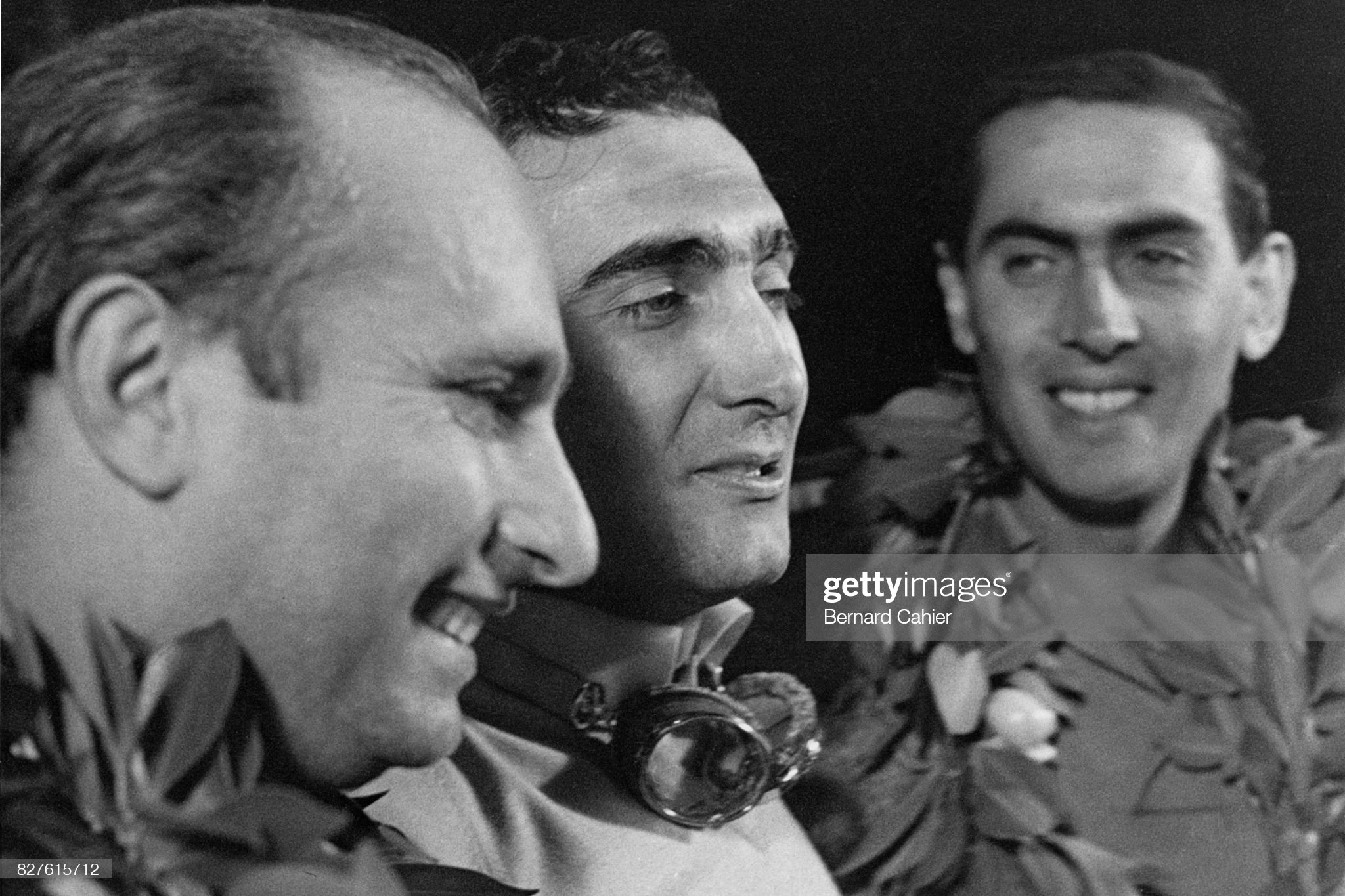

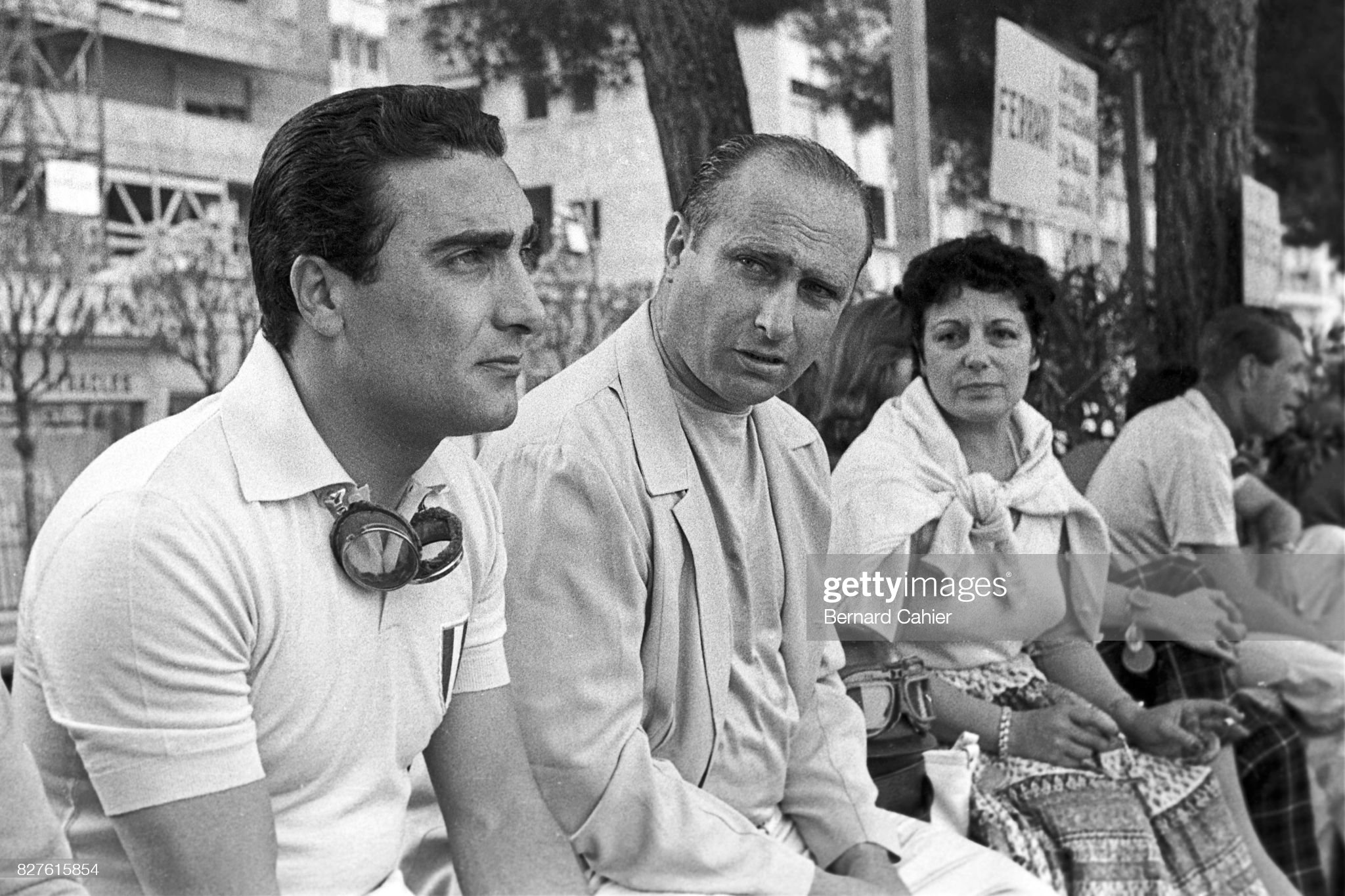

Nino Farina, Alberto Ascari, Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 05 September 1954. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Museo Nicolis, Alberto Ascari.

Alberto Ascari and his fellow drivers.

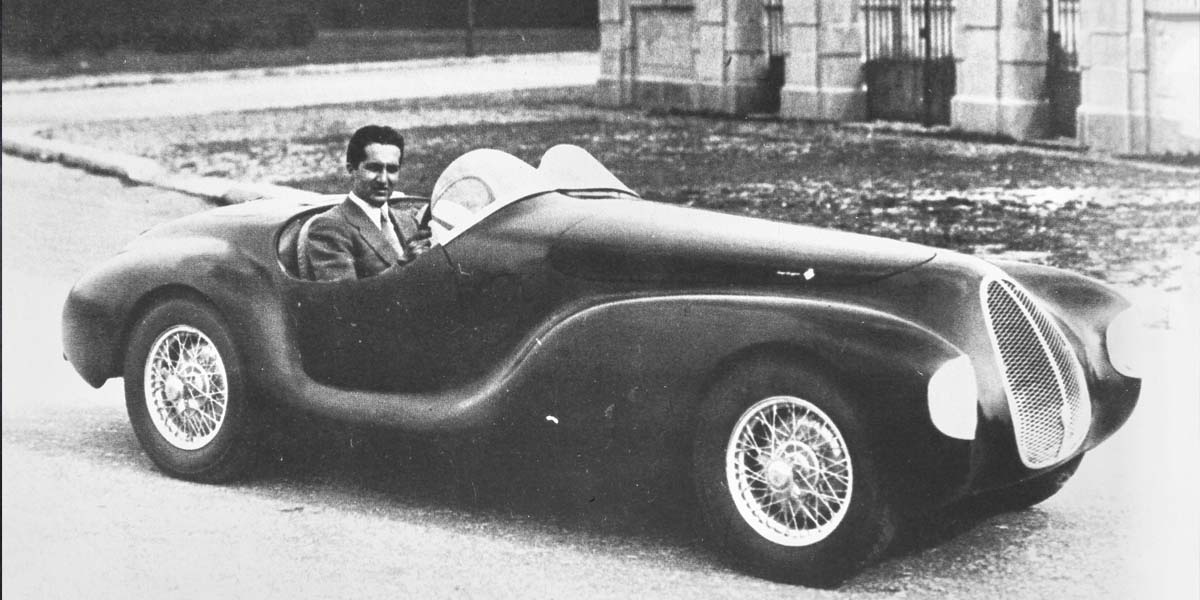

By that time little Alberto was already immersed in his father's milieu, having met the many big names in racing, including Antonio's close friend Enzo Ferrari, who frequented the thriving Ascari Fiat dealership in Milan. Despite the tragic loss of his beloved father Alberto succumbed to the lure of racing. His famous name helped get him started, though it was on two wheels, not four, when, as a 19-year-old he was hired to ride for the Bianchi motorcycle team. His first four-wheel foray came in the 1940 Mille Miglia, where Enzo Ferrari gave him a ride in a Tipo 815 Spyder. When Italy entered World War II the Ascari garage in Milan, now run by Alberto, was conscripted to service and maintain military vehicles. During the war years he also established a transport business, supplying fuel to Italian army depots in North Africa. His partner in this enterprise was Luigi Villoresi, a racing driver with whom he developed a father-son relationship.

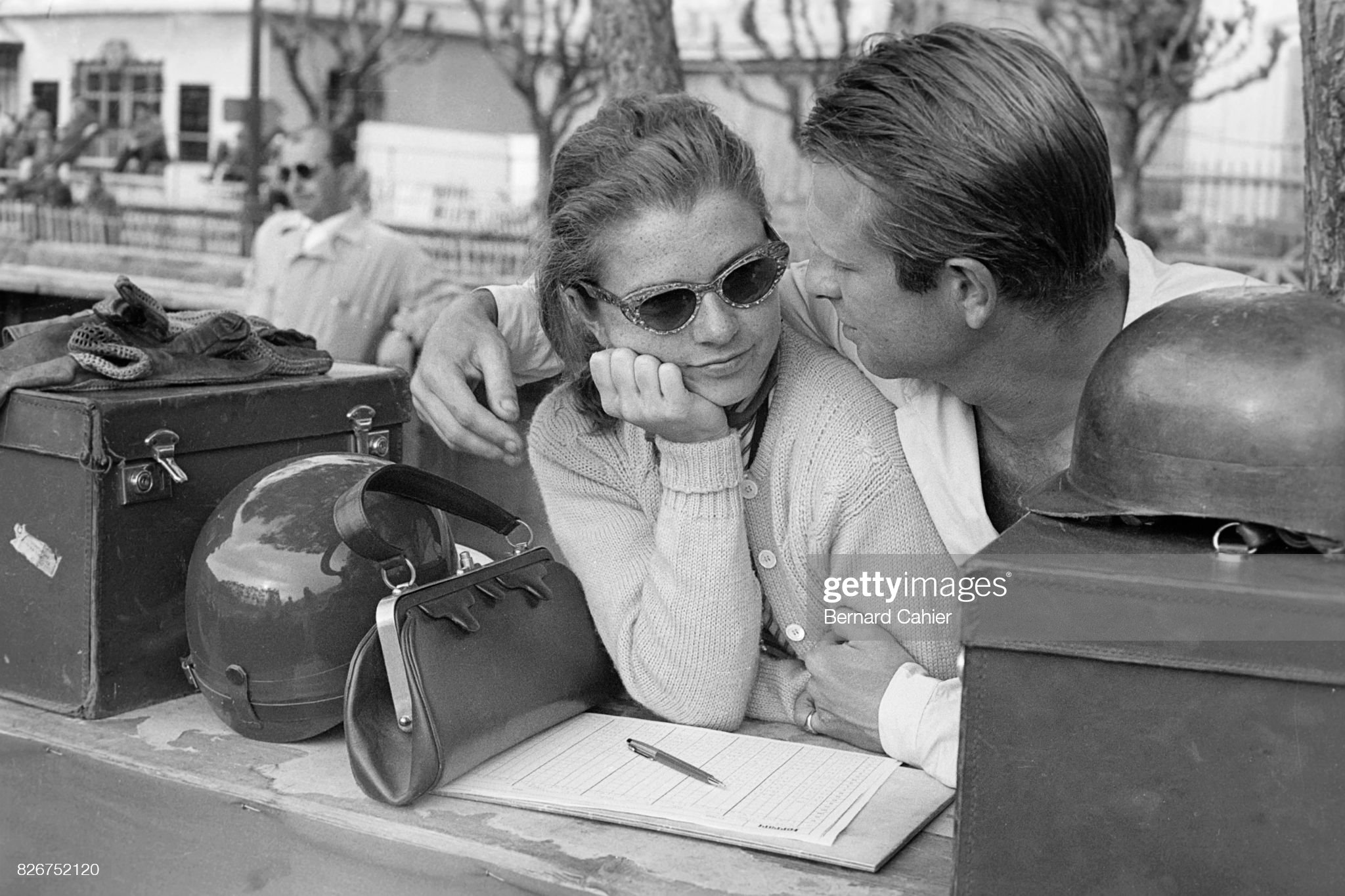

Alberto Ascari with his wife Mietta.

By the end of the war Alberto was a family man, having married Mietta and become the father of Patrizia and Antonio, who was named after his celebrated grandfather.

Alberto Ascari.

Alberto Ascari.

Alberto Ascari drinks from a bottle in 1948. Photo by Maurice Jarnoux / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Given his family responsibilities Alberto was prepared not to race again, but Villoresi persuaded him to continue. In 1949 they became team mates in Enzo Ferrari's team, where Ascari's dominance would make him Formula One racing’s first back-to-back champion.

Ascari gets the flag as winner of the Gen. San Martin Trophy Auto Race at Mar Del Plata on January 20, 1950. Photo by Getty Images.

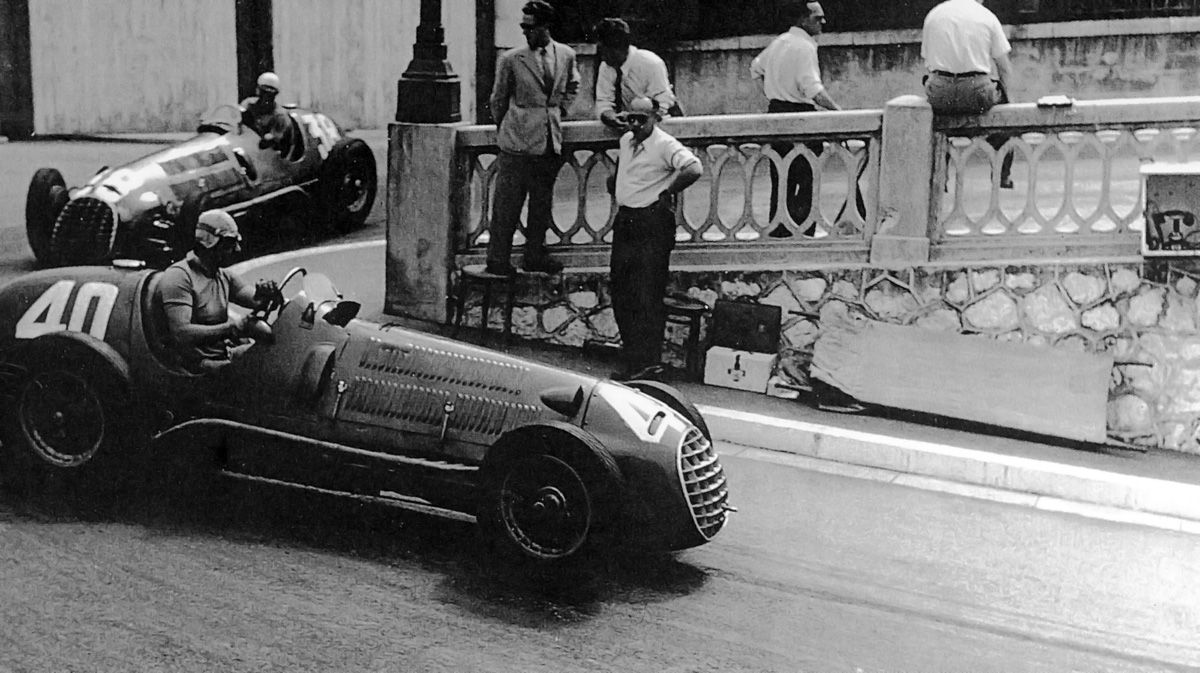

Alberto Ascari in Monaco on 21 May 1950.

Alberto Ascari in a Ferrari at the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring on 20 August 1950. Photo by Ullstein Bild / via Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari being chaired after victory at the Penya Rhin Grand Prix in Barcelona October 27, 1950. Photo by S&G / PA Images via Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari, Ferrari, Indianapolis 500, May 30, 1952.

The Ferrari team of 500 F2 cars: number 26 Luigi Villoresi, number 20 "Nino" Farina (plus a spare car), number 22 Alberto Ascari and number 24 André Simon, Monza Autodromo, June 07, 1952. Photo by Corrado Millanta / Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

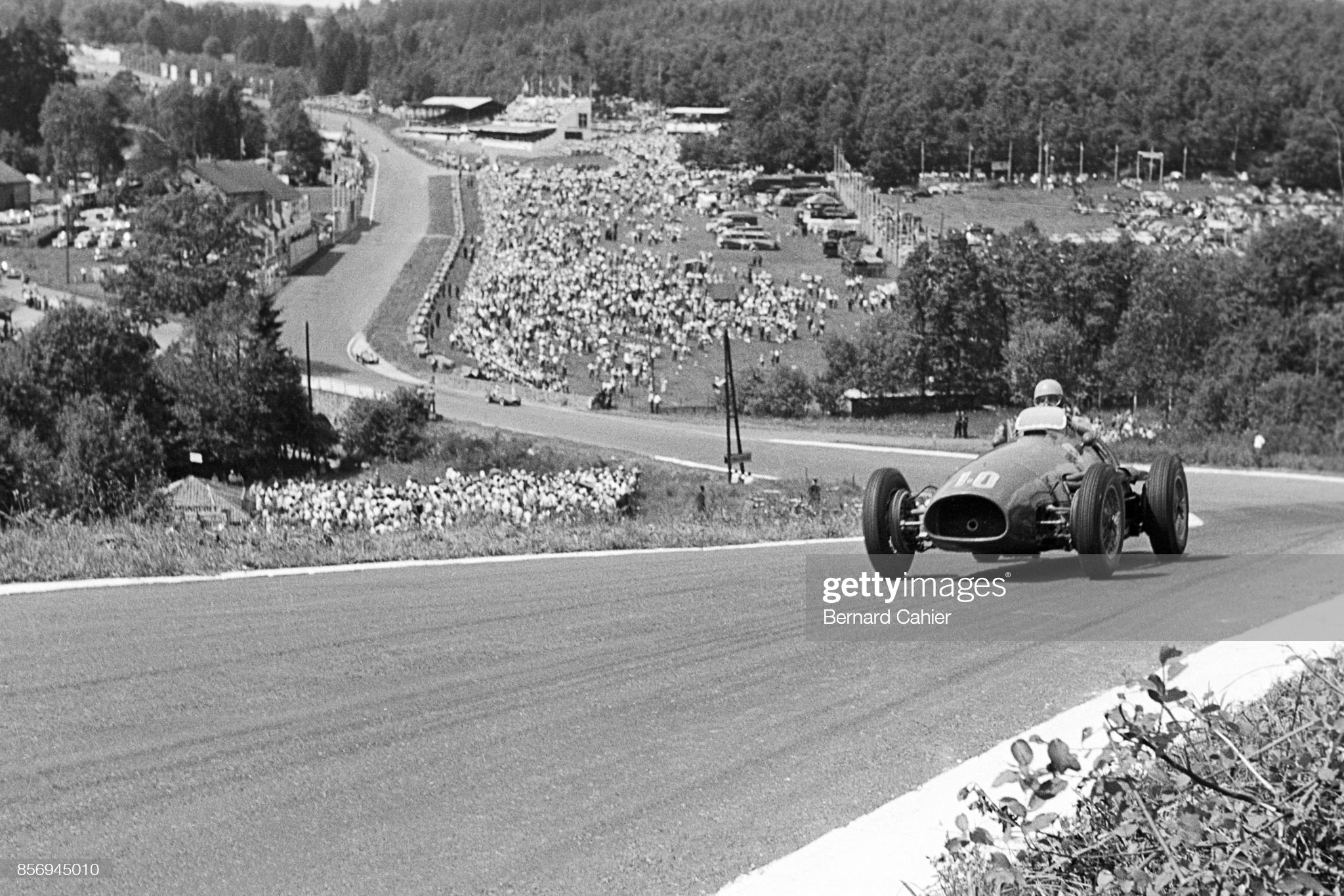

Alberto Ascari at the wheel of his Ferrari on the Francorchamps racing circuit in Belgium in 1952, training in view of Europe's Grand Prix, which he won. Photo by Keystone-France / Gamma -Keystone via Getty Images.

In 1952 he drove his Ferrari 500 to victory in six of the seven championship races.

Alberto Ascari at the wheel of a racing car in 1953. Photo by National Motor Museum / Heritage Images / Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari in a Ferrari in 1953, being photographed with a female fan and a young driver. Photo by National Motor Museum / Heritage Images / Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari, Ferrari, in 1953.

Alberto Ascari's wrecked car in the non-championship VI GP dell'Autodromo di Monza in 1953 after being forced off the track by Maria Piazza's Ferrari 250MM. Reports suggested the shunt was "minor" but the damage to his Ferrari was severe. The car, 0428MM, was later rebuilt with Scaglietti bodywork.

World Champion Alberto Ascari won for the second time the Grand Prix of Pau, France, on April 07, 1953, breaking records. The picture shows (from right - left), the second place, who was the British Hawthorn, the third Harry Shell and the first one, Ascari, next to Madame Bournac, wife of the President of the A.C.B.B. and Madame Delaunay after Ascari's victory.

Alberto Ascari, Ferrari 500, Grand Prix of Belgium, Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps, 21 June 1953. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari, Ferrari 500, Grand Prix of France, Reims-Gueux, 05 July 1953. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Alberto Ascari during practice of the Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 13 September 1953. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

In 1953 he again overpowered the opposition, winning five times and cruising to a second successive driving title. A great driver admired by his peers, Ascari was also a charming man idolized by a legion of admirers. His illustrious heritage helped, as did his superlative driving skill, but his winning persona also contributed to his huge popularity. It was easy to like a hero who was so obviously no prima donna, the driver with the plump physique whom the Italian fans nicknamed 'Ciccio' (chubby) and whose open and friendly disposition was apparent from his genial smile. Even his idiosyncratic superstitions were endearing, an entirely human response to the dangers of racing. He avoided black cats like the plague, had a horror of unlucky numbers and never allowed anyone else to handle the briefcase that contained his racing apparel: the lucky blue helmet and T-shirt, the goggles and gloves.

But perhaps he also had inner demons, for he was a chronic insomniac and prone to stomach ulcers.

Alberto Ascari at the sea in Santa Margherita Ligure in company of the sons Tonino and Patrizia on July 01, 1952.

Enzo Ferrari, who knew Ascari was deeply devoted to his family, once asked him why he didn't demonstrate his affection. "I prefer to treat them the hard way", Alberto said. "I don't want them to love me too much. Because they will suffer less if one of these days I am killed."

Such an eventuality seemed most unlikely for a driver who always strictly observed self-imposed safety margins, who studiously avoided exceeding the limits of his car or himself and whose relaxed and smooth style looked so effortless as to suggest he would have plenty of skill in reserve to correct any rare mistake.

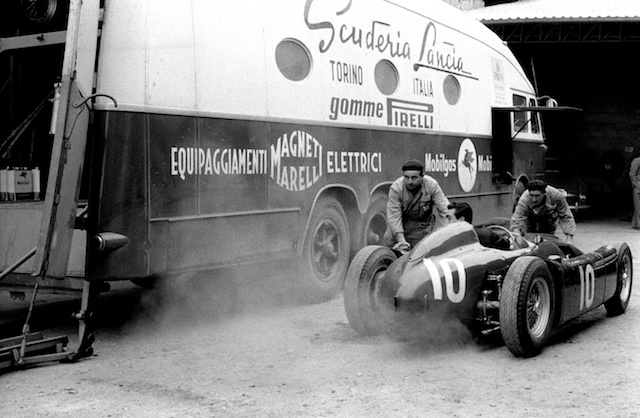

Following his runaway championships he moved to Lancia for, he admitted, more money than Ferrari was prepared to pay him.

Brescia, the eve of the 1954 Mille Miglia. Eugenio Castellotti, Alberto Ascari and Piero Taruffi.

Having been sidelined for most of 1954 because the Lancias were not yet raceworthy, he embarked on an ill-fated 1955 campaign.

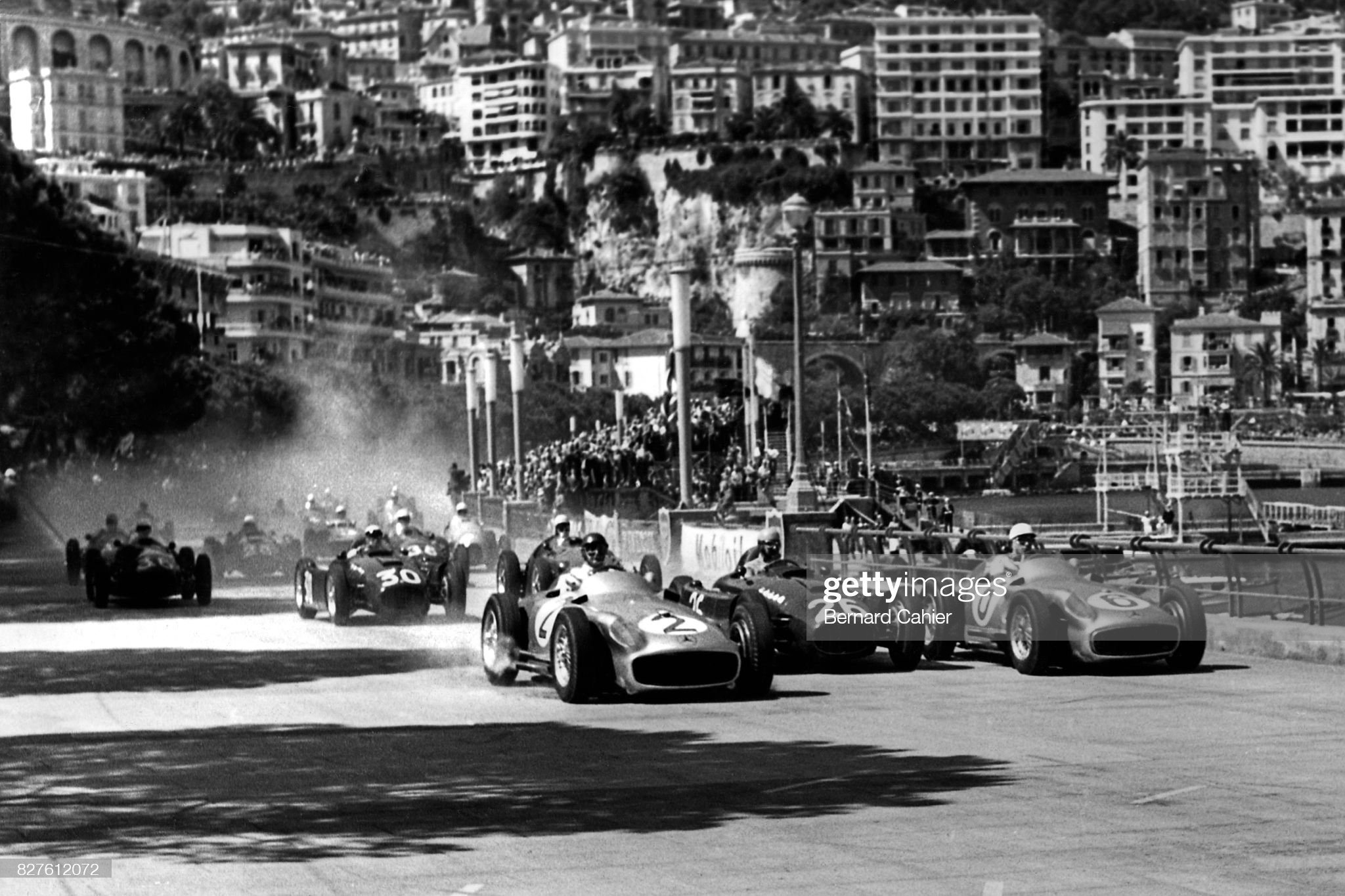

Juan Fangio (Mercedes W196), Alberto Ascari (Lancia D50) and Stirling Moss (Mercedes W196) in the front row, Monaco Grand Prix, Monte Carlo, May 21, 1955. Photo by Yves Debraine / Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

Juan Manuel Fangio, Alberto Ascari, Stirling Moss, Grand Prix of Monaco, 22 May 1955. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

The D50 in 1955 at Monte Carlo whizzes past the sign reminding you to go slow and make no noise. Perfect!

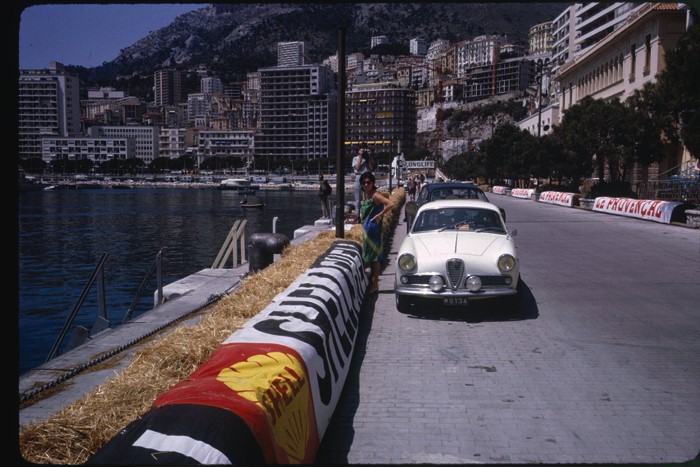

Nice picture of Monaco in 1955.

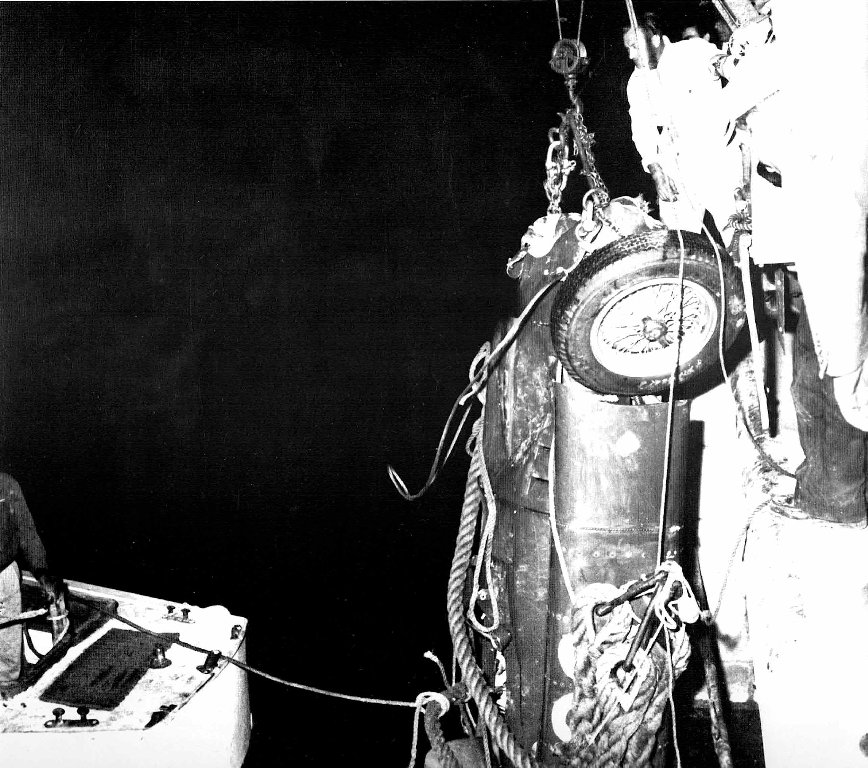

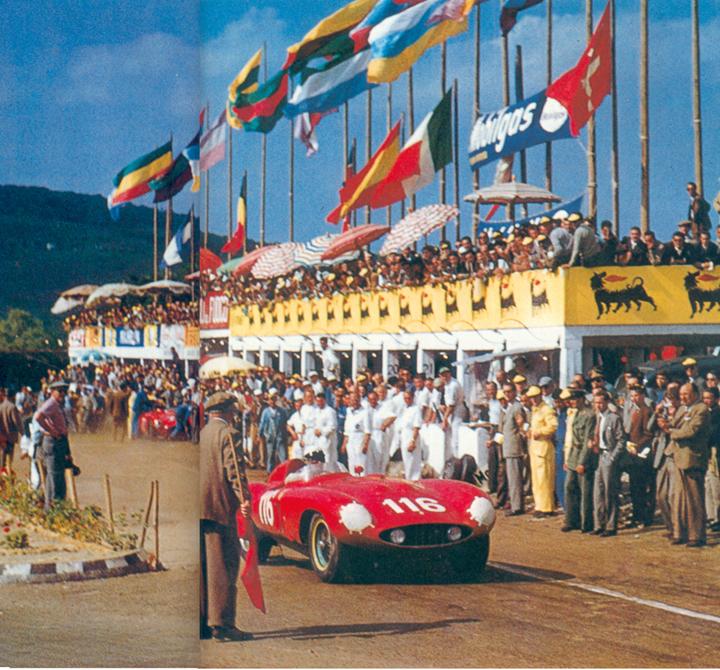

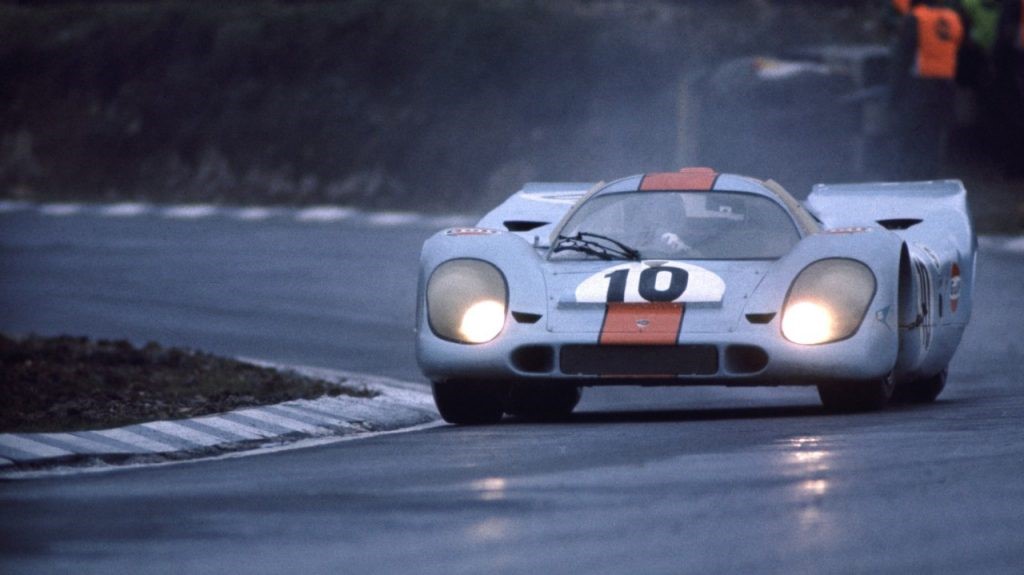

In the Monaco Grand Prix Ascari's leading Lancia D50 suddenly swerved out of control in the harbour chicane, flew into the Mediterranean and sank, its disappearance marked only by a stream of bubbles and an oil slick. Half a minute later, the familiar light blue helmet bobbed to the surface and Ascari was hauled aboard a rescue launch manned by frogmen.

Alberto Ascari's Lancia recovered from the waters of the port of Monte Carlo, following the accident that occurred during the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix.

Monte Carlo, 22 May 1955. The wreck of Ascari’s Lancia D50 after the accident.

In the Monaco hospital, where he was treated for a broken nose, bruises and shock, Ascari seemed as embarrassed as he was thankful for his miraculous escape.

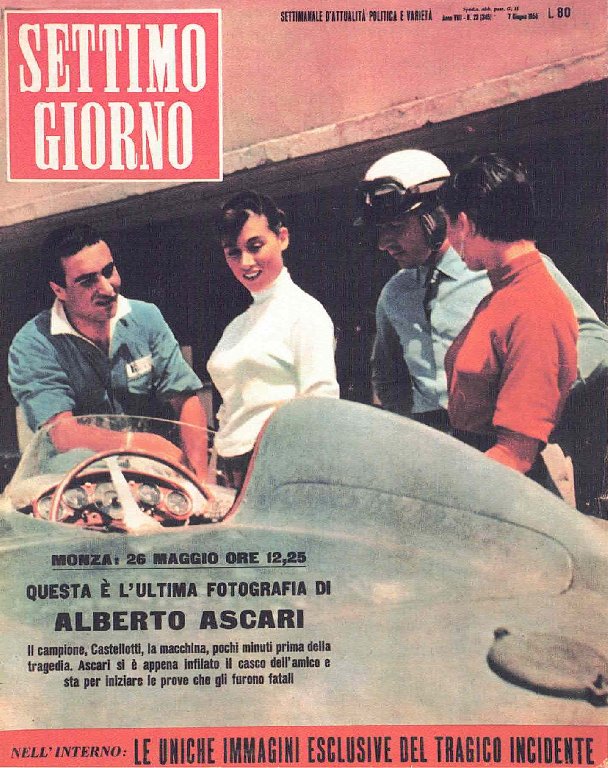

Four days later he unexpectedly appeared at Monza to watch a practice session in which Eugenio Castellotti was testing a Ferrari sports car they were scheduled to share in a forthcoming endurance race. Ascari surprised everyone by announcing he wanted to do a few laps to make sure he had not lost his nerve. He was wearing a jacket and tie and had left his lucky blue helmet at home, so he borrowed Castellotti's white helmet and set off around Monza.

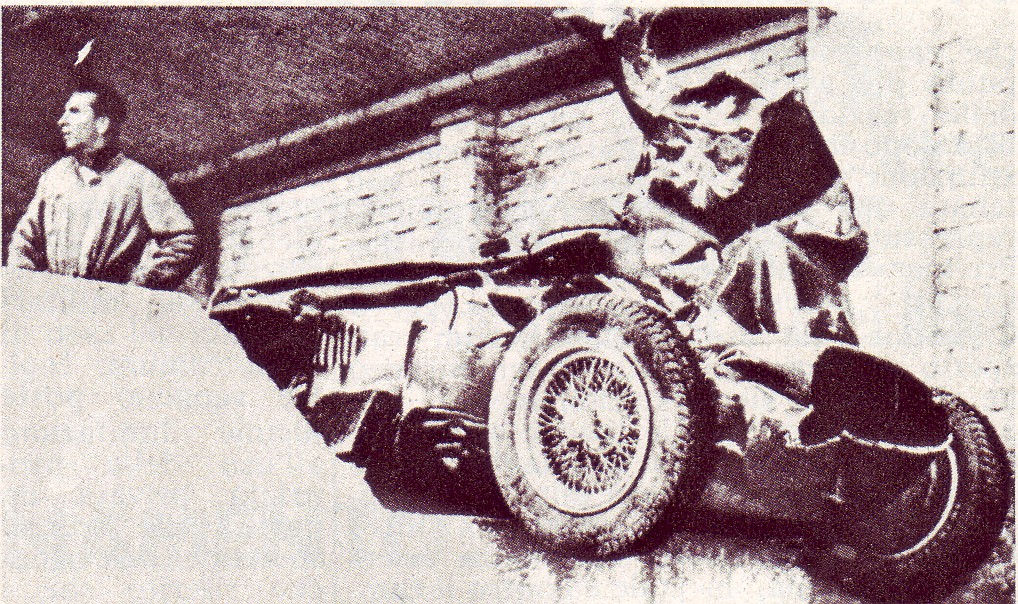

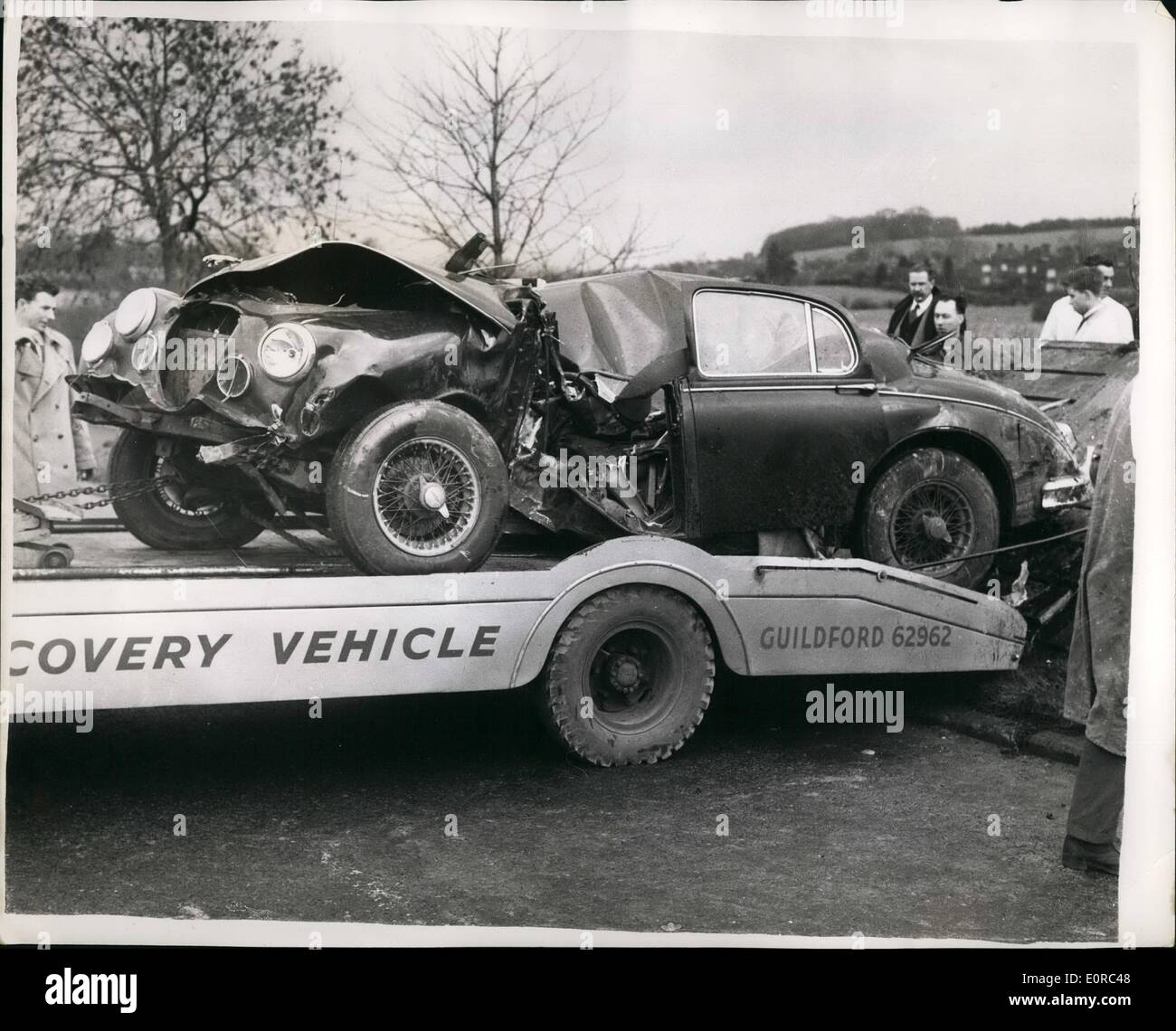

26th May 1955, Italian motor racing ace Alberto Ascari died when this Ferrari car he was testing skidded and somersaulted throwing him from the car. Photo by Paul Popper / Popperfoto via Getty Images.

26th May 1955, Alberto Ascari died when this Ferrari car he was testing skidded and somersaulted throwing him from the car.

On the third lap the Ferrari crashed inexplicably and Alberto Ascari was killed.

Had he suffered a blackout, a legacy of his Monaco accident? Was there a sudden gust of wind, had his flapping tie momentarily obscured his vision? Had he swerved suddenly to avoid a wandering track worker, or an animal, perhaps a black cat?

The eerie certainties were that Alberto Ascari died on May 26, 1955, at the age of 36. Antonio Ascari was also 36 when he died, on July 26, 1925. Both father and son had won 13 championship Grands Prix. Both were killed four days after surviving serious accidents. Both had crashed fatally at the exit of fast but easy left-hand corners and both left behind a wife and two children. A distraught Mietta Ascari told Enzo Ferrari that were it not for their children she would gladly have joined her beloved Alberto in heaven.

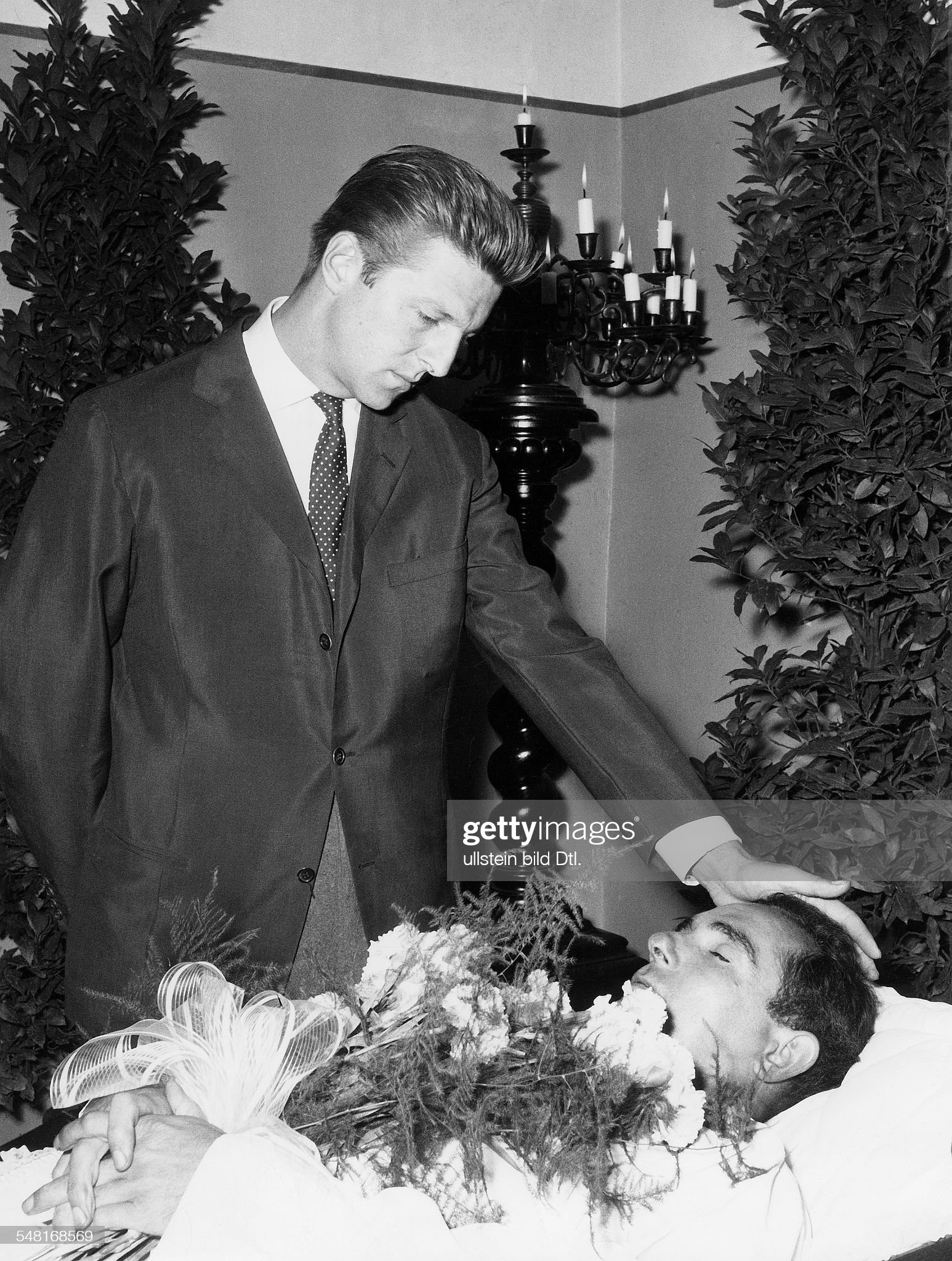

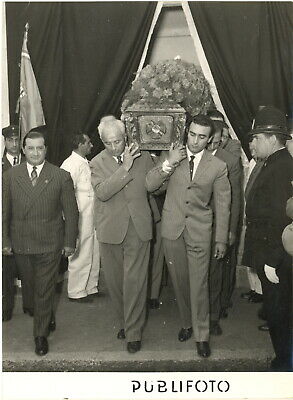

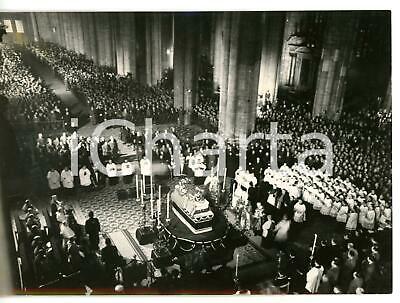

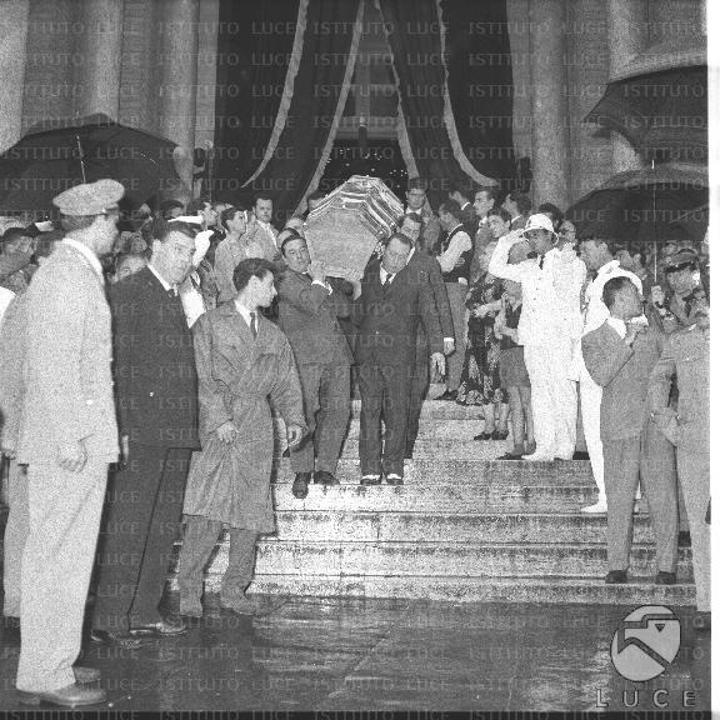

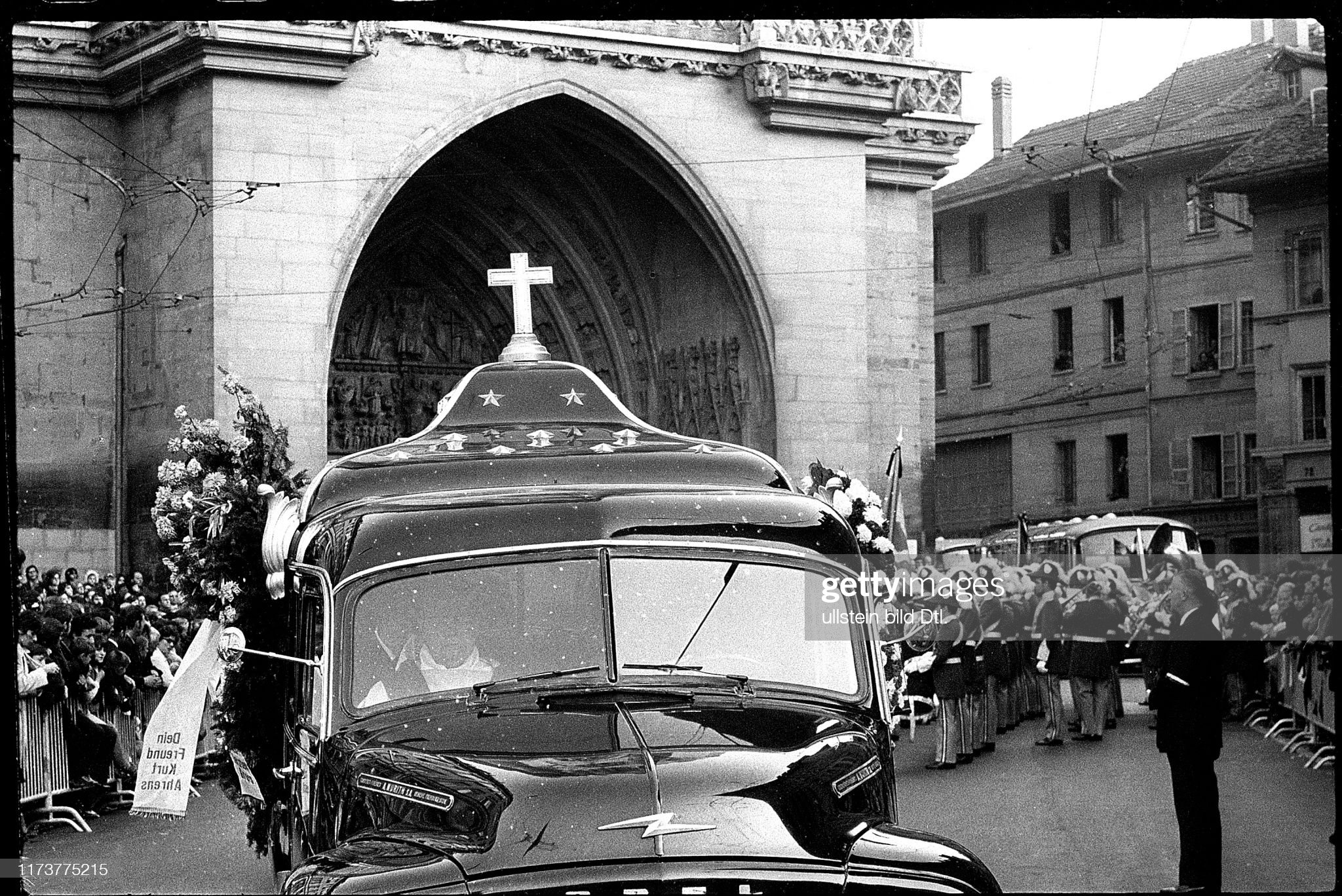

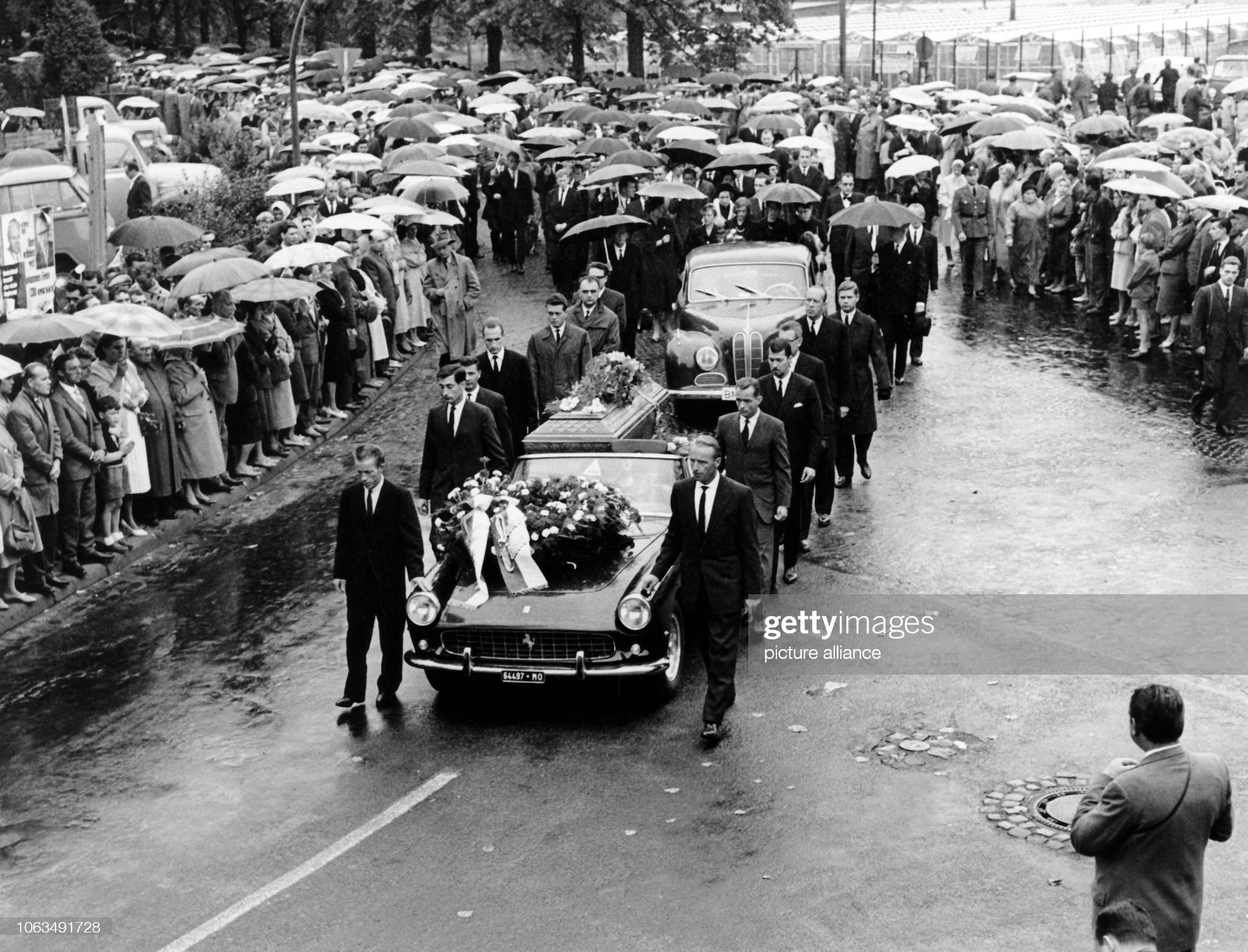

27th May 1955, the coffin of Alberto Ascari in Milan. Photo by Popperfoto via Getty Images.

27th May 1955, the body of Alberto Ascari in Milan.

27th May 1955, the funeral of Alberto Ascari in Milan.

All of Italy mourned the loss and, on the day of the funeral in Milan, the whole city fell silent, as a solemn procession carrying the fallen hero moved slowly through the streets lined with an estimated one million silent mourners dressed in black. It required 15 carriages to carry the profusion of wreaths and flowers and in the hearse, drawn by a team of plumed black horses, his familiar light blue helmet lay on top of the black coffin. And in the Milan cemetery Alberto Ascari was laid to rest next the grave of his father.

The June 07, 1955 cover of ‘Settimo giorno’ magazine.

September 06, 2018, Turin, Piedmont, Italy. The pit lane where Alberto Ascari won the 1955 Valentino Grand Prix.

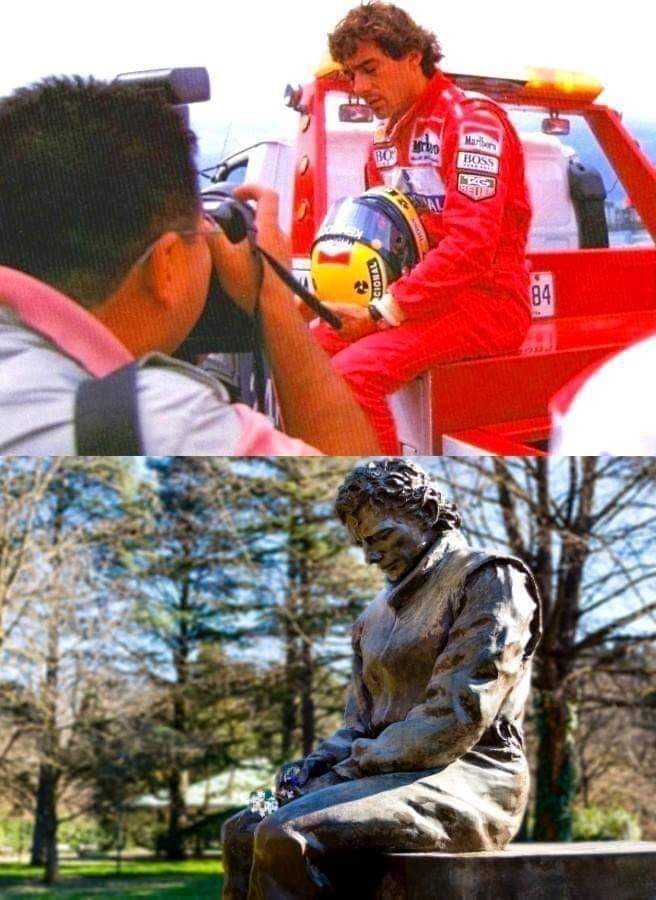

Inauguration of the monument dedicated to Alberto Ascari at the presence of Veronica and Selvaggia Ascari, respectively nephew and great-granddaughter of the champion, Milan, Italy, 11 Jun 2021.

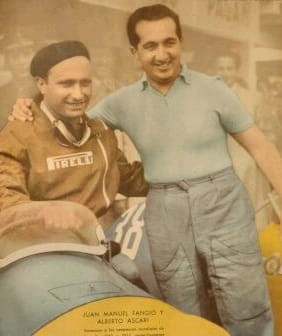

He is one of the two Italian Formula 1 world champions along with Nino Farina, he is the last to have succeeded. After him, we are still waiting for a tricolor F1 world champion driver. He is remembered as the only driver at the level of Juan Manuel Fangio.

To race Ascari challenged and fought tenaciously the maternal resistance, starting with races in Monza, paid with the Greek vocabulary that he sells. His mother buys it back for him several times, thinking that his schoolmates are stealing it, until she finds out everything and lets him do it, resigned. Alberto Ascari, just seven years old when he is orphaned, decides that he will follow in his father's footsteps and, in 1936, starts with motorcycle racing. He made his debut on four wheels in 1940. He drives the first Ferrari in history, when it still did not bear the Prancing Horse logo: the Auto Avio Costruzioni 815 with which he raced the 1940 Mille Miglia. He then raced with Cisitalia, Maserati, Alfa Romeo and, obviously, Ferrari, with which, in 1952 and 1953, he became F1 world champion.

A formidable driver, one of the greatest Italian pilots of the twentieth century, he was the friend of the mechanics in the pits, the champion who after each victorious race climbed the stairs of the building in Viale Abruzzi in Milan, then the temporary post-war headquarters of Pirelli, visiting his trusted technological partner.

He was nicknamed “Ciccio”, as Gianni Brera called him because of his not exactly slim physique. Or again, for the same reason, he was “The mountain that breathes”. His wife Mietta confirmed this to the journalist Nino Nutrizio in the article published in the Pirelli magazine in 1951, dedicated to the rest of the champions: "the mountain is over there sleeping and breathing. Good sign, it means that everything is fine."

Ascari was the first driver to bring an absolutely scientific method in personal and car preparation, probably due to his deep superstition. He thought that the worst could be avoided with the method. So he never raced with race numbers 13 and 17, never on day 26, never with the overalls, underpants and socks used in practice. And he always used the same helmet and the same gloves.

Alberto was for many people also "Ascarino", as he was Antonio's son. Only four days before his death, during the Monaco Grand Prix on Sunday 22 May, Alberto Ascari, driving the Lancia, is second and is trying to overtake Moss' Mercedes which precedes him. On lap 81, Moss abruptly abandons the race due to an engine problem. Ascari doesn’t know it and continues to race. He accelerates to the exit of the tunnel, gets distracted because he sees the audience cheering. He loses control of the car, breaks through the barriers and flies out to sea, into the port. Ascari frees himself from the car that has ended ten meters under the waters of the Mediterranean and comes out almost unscathed. After leaving the hospital after the accident, he returns home to Milan with his wife Mietta. While he is there, on Thursday 26 May he receives a phone call from Villoresi and Castellotti, two top-level drivers who are also two friends. They invited him to test a Ferrari 750 Sport, an absolutely playful test on the Monza track. Ascari joins them, borrows the Ferrari from Castellotti and also the equipment. He renounces all superstitious habits: one among many, never picking up a steering wheel on the 26th. Especially after his friend Silvio Vailati had also died on the 26th, in May 1940, in a race in Genoa. Before having lunch with friends, he gets on board. Alberto only wants to do three laps, the third is fatal to him. We hear a roar. Nobody sees him, nobody knows what happened. Skidding in what was at the time the Vialone curve, now called the Ascari variant in honor of the driver, the car overturns, there is nothing to do. Alberto's body is thrown fifteen meters away. Friends are incredulous. On the asphalt there is the sign of a braking, inexplicable. He dies instantly from the chest breakthrough, crushed under his Ferrari. Lancia decides to leave racing.

«I only obey a passion. The races. Without them, I wouldn't know how to live." Alberto Ascari

"At the start I look Ascari in the eyes and I often understand that I will have to finish second." Juan Manuel Fangio

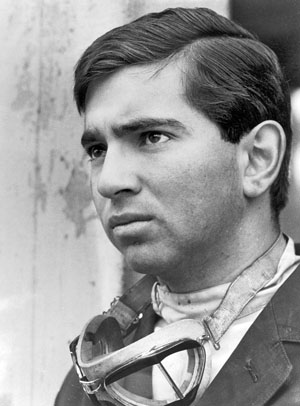

Lorenzo Bandini

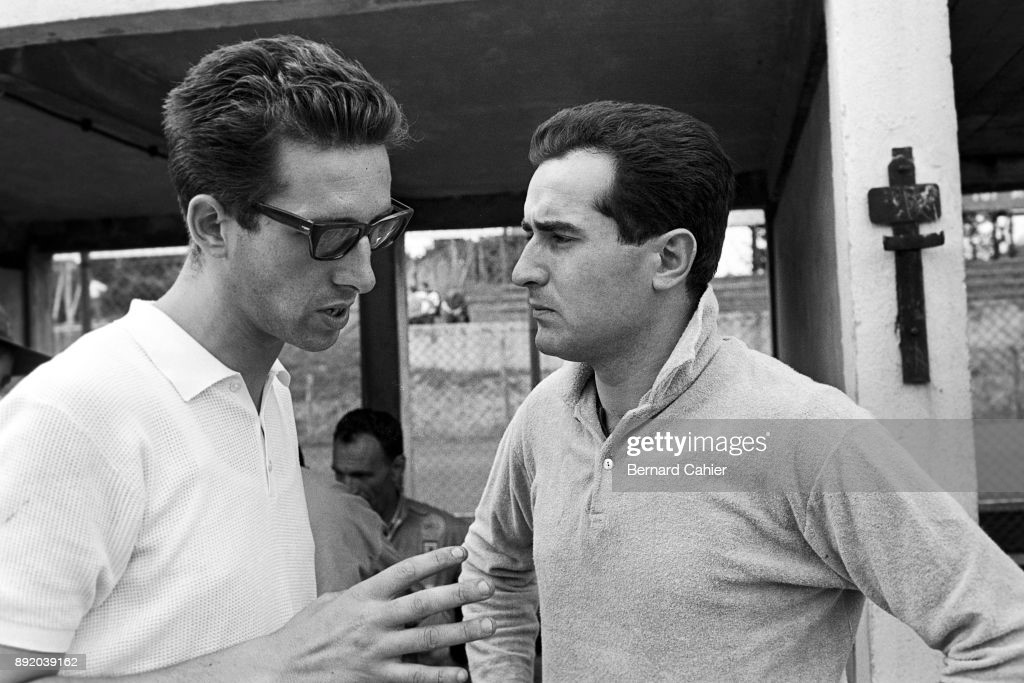

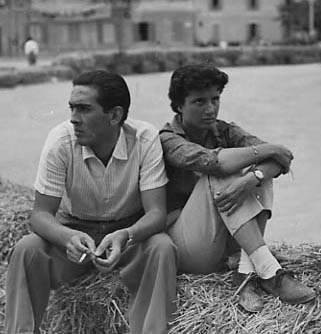

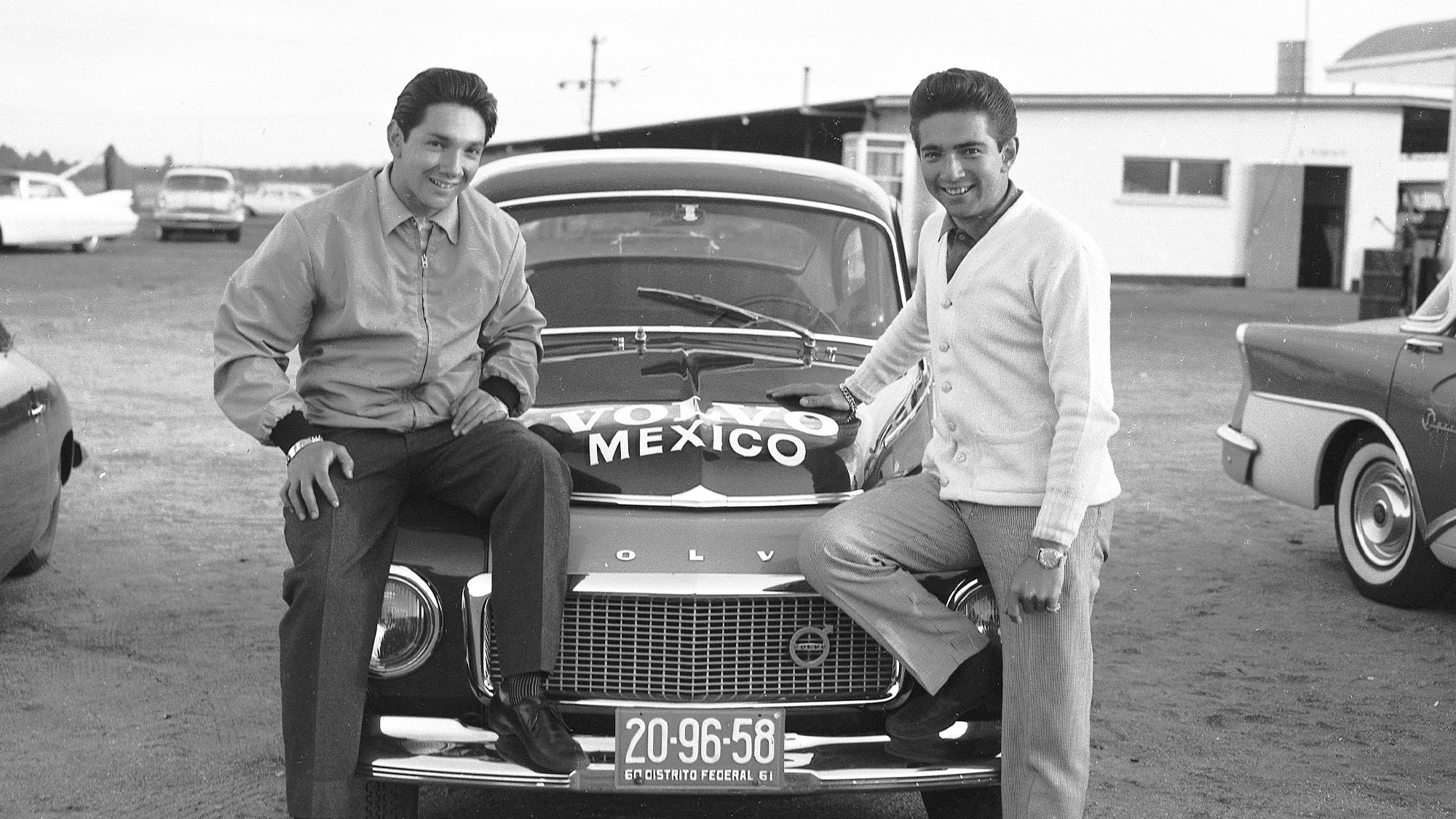

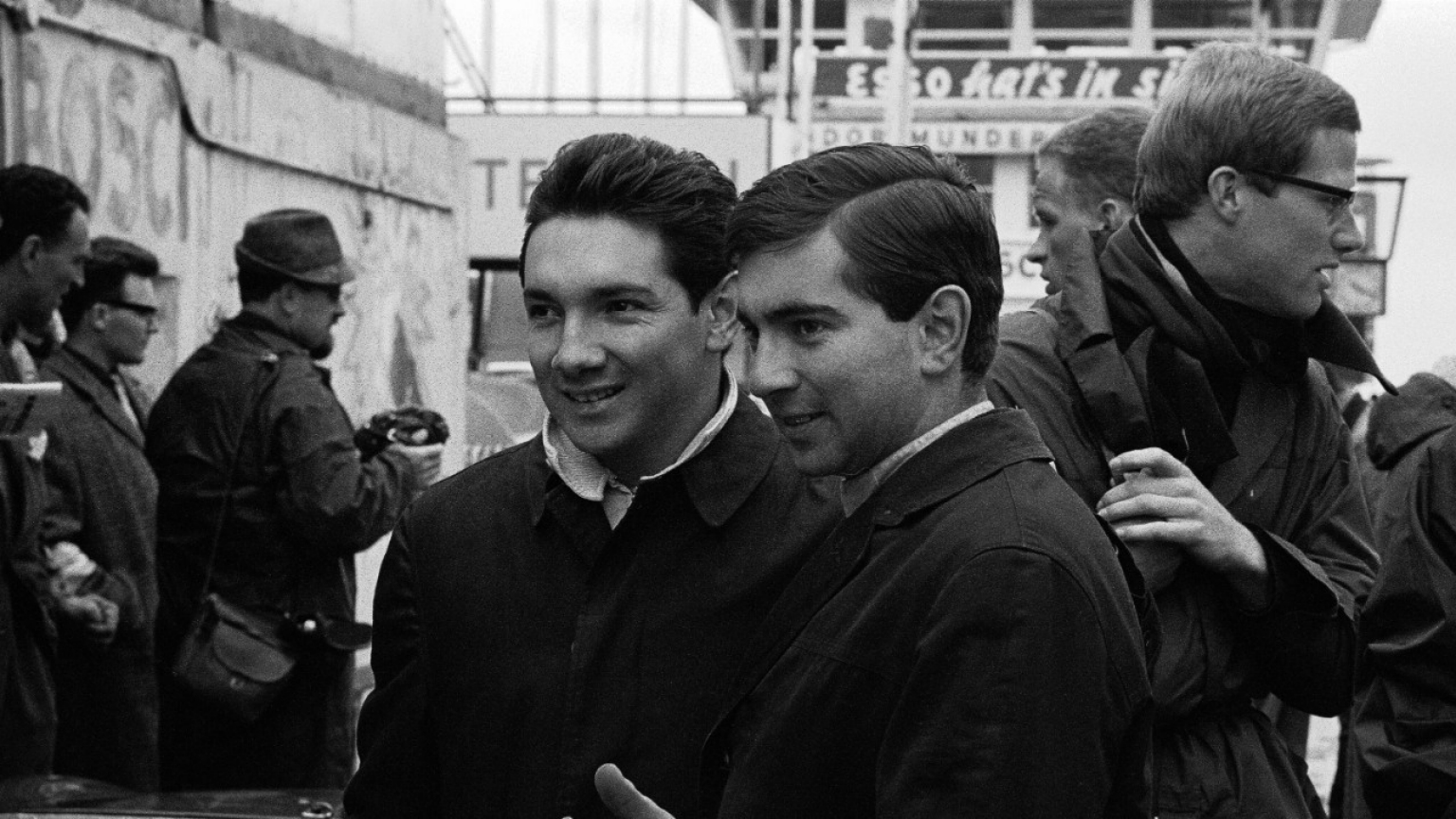

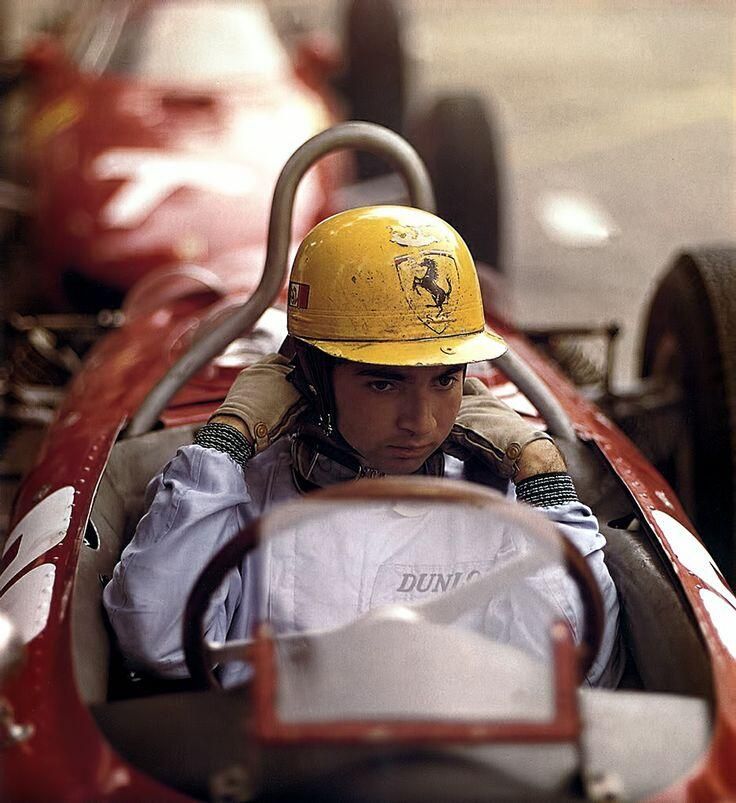

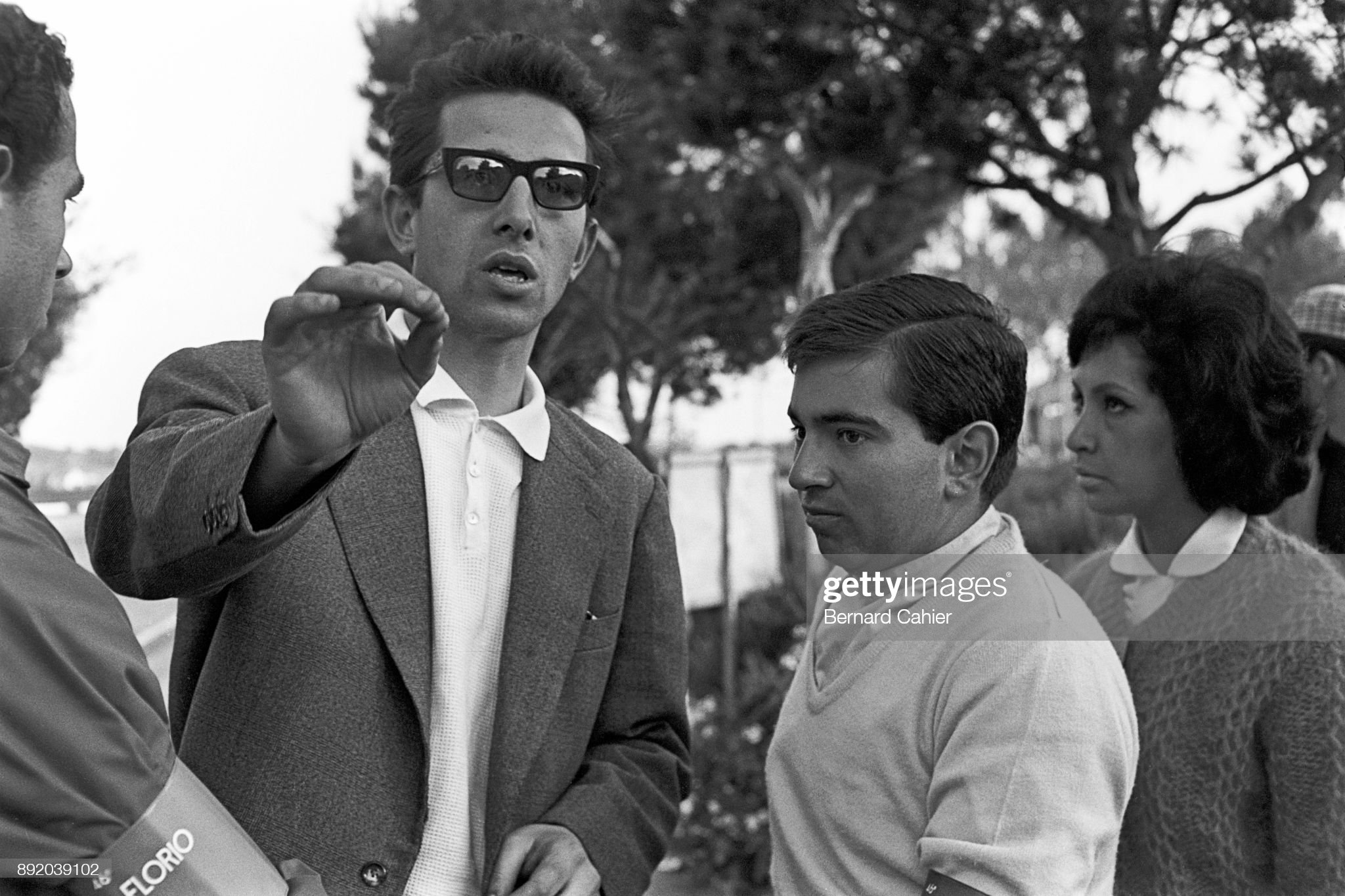

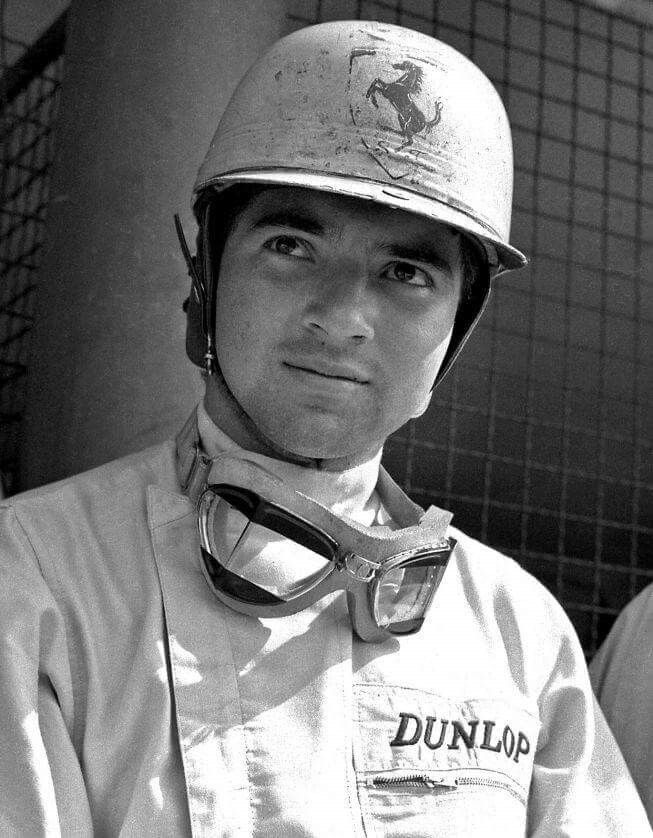

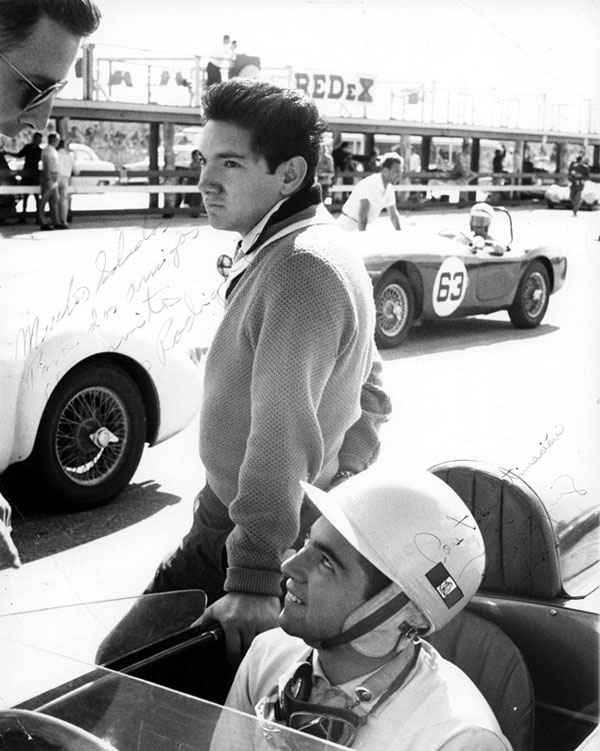

Giancarlo Baghetti and Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari 156, Grand Prix of Belgium, Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps, 17 June 1962. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Lorenzo Bandini with Mauro Forghieri, Grand Prix of Germany, Nurburgring, 05 August 1962. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

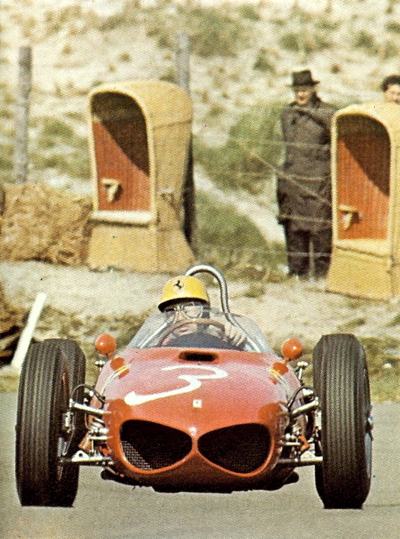

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari 156, Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 16 September 1962. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

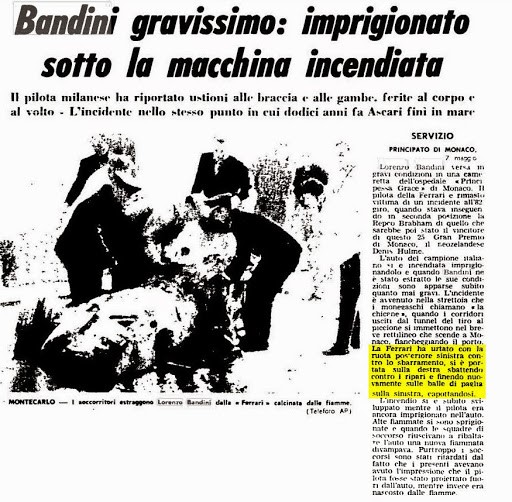

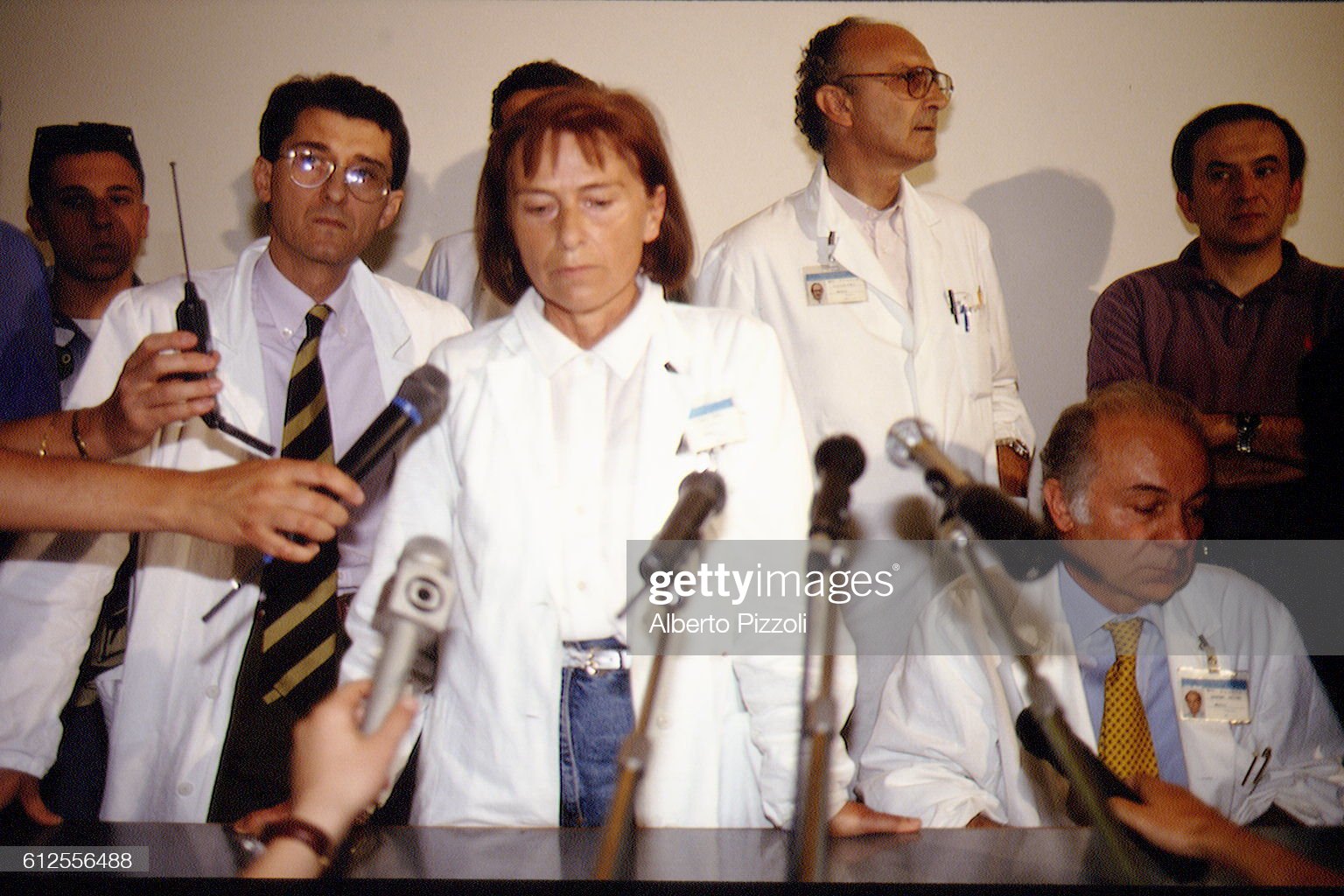

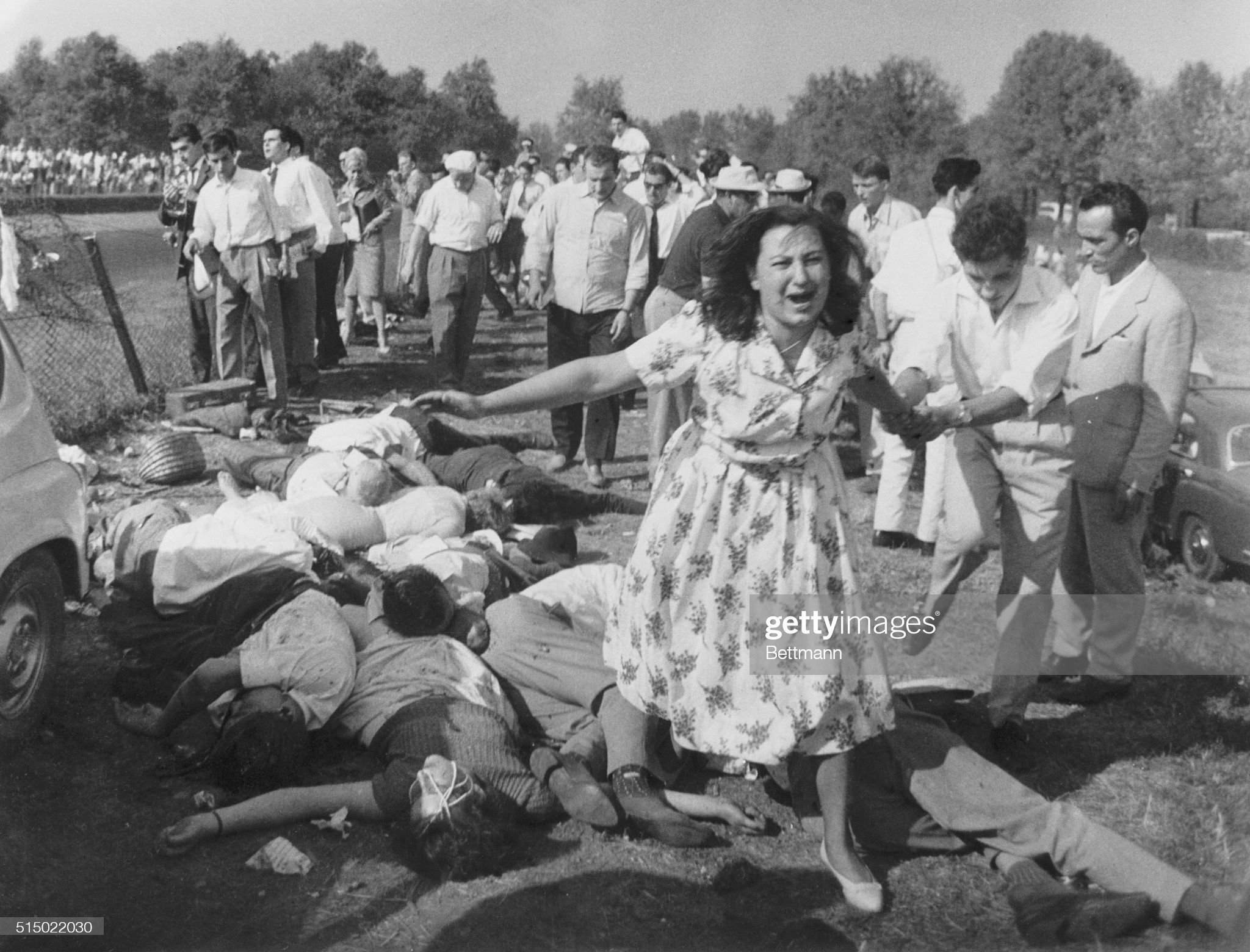

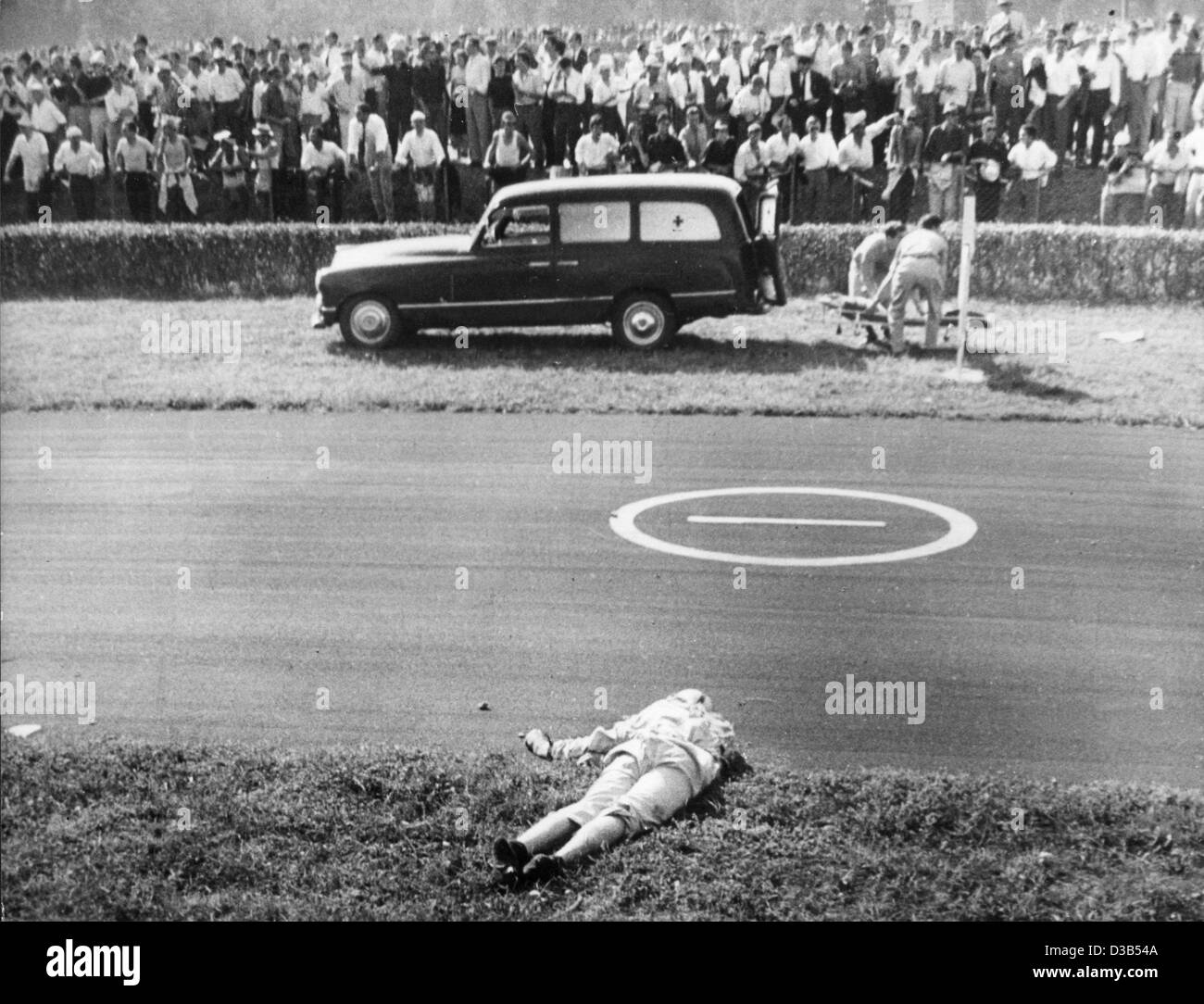

Lorenzo Bandini dies. Monte Carlo. Italian auto racing star Lorenzo Bandini died today of the severe burns and injuries he received when his Ferrari crashed and burst into flames during Sunday’s running of the Monaco Grand Prix. He was 32. Bandini died despite the night and day efforts of leading French and Italian specialists to save his life. Only hours before his death, doctors had said his condition appeared “slightly improved.” He underwent a four-and-half-hour operation following the accident which marred the 25th running of the Monaco classic. The accident, which took place during the 82nd lap of the race at the tricky chicane near the Monaco harbor, has once more raised the problem of the safety of automobile racing. The basic problem what can be done to prevent accidents and, once they have taken place, what measures should be taken to make them as miner as possible. The race was nearing the end of the 100 laps of the 1.95-mile track with Bandini in second place, behind New Zealander Dennis Hulme driving a V-8 three liter Repco Brabham car and was beginning to close in on the leader when he touched the straw bales at the chicane. Bandini’s car bounced on the bales and was thrown into an electric light pole which richocheted it back upside down on the track in the middle of the bales. The car burst into flames and also set the straw afire. From then on it was chaos. The firemen on hand had no anti-fire equipment, their carbon extinguishers were small, nobody in charge took over the situation. It was a photographer, a doctor and an automobile fan, the prince of Bourbon-Parma, who rushed to try to put the car back upright and pull out the driver who was screaming with pain under the blazing car. When they finally managed to pull Bandini out, the wind blew back the flames from the straw bales and swept them over Bandini and his helpers. The state-owned French television service said flatly the Monaco firemen “walked away from the fire."

Terruzzi tells: Lorenzo Bandini. Like an older brother, a symbol of a time full of collective energy and dreams. By Giorgio Terruzzi. Published on 28.03.2017.

His smiling face, simple and clean, appears and reappears in my memory. Since, as a kid, I spied on him when he went to visit the Scuderia Centro Sud, which was then a beautiful villa near the Monza park.

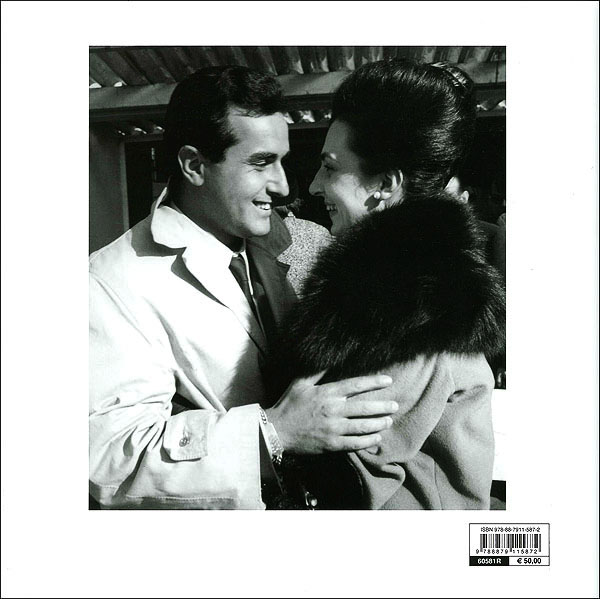

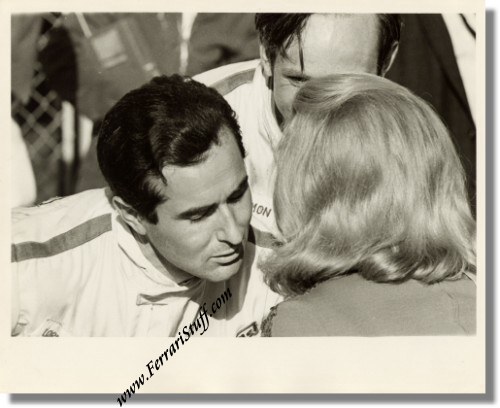

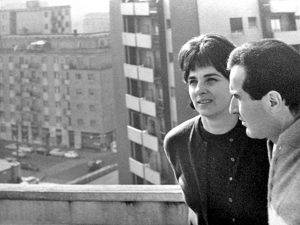

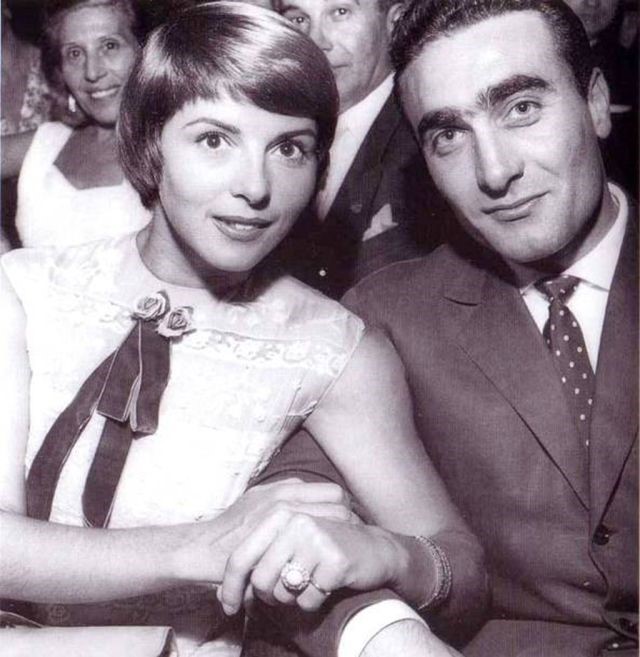

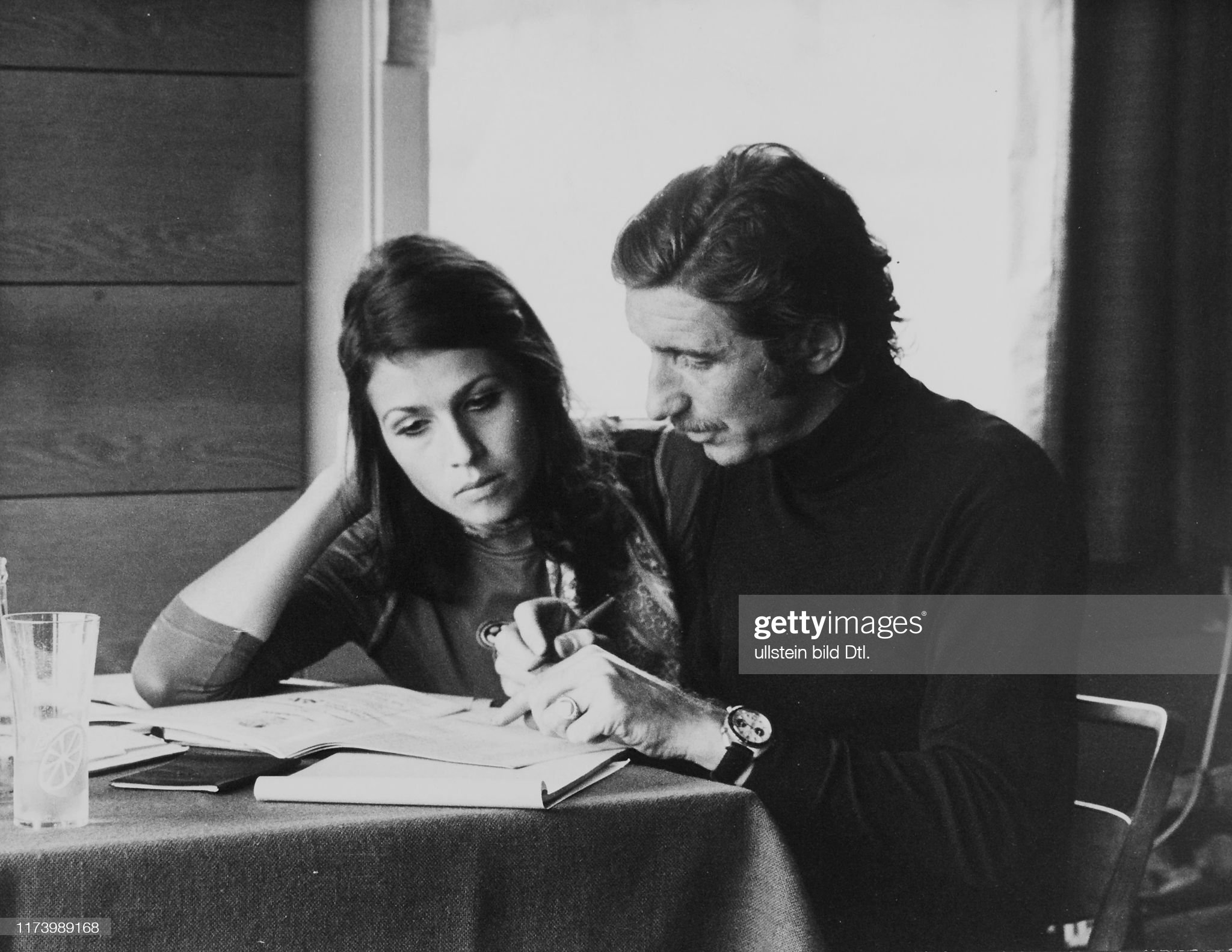

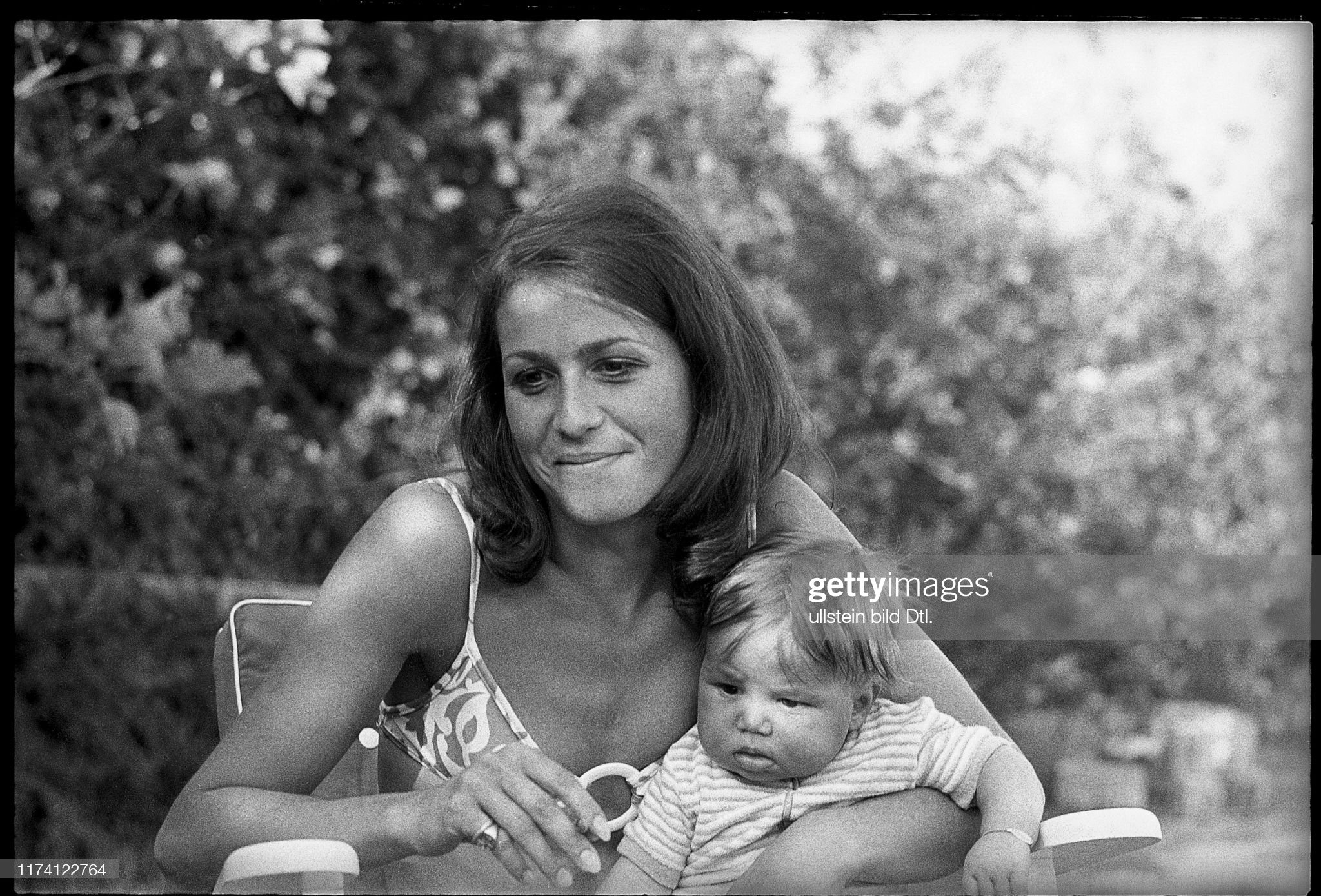

Lorenzo and Margherita Bandini.

Lorenzo and Margherita Bandini.

Lorenzo and Margherita Bandini.

Lorenzo and Margherita Bandini.

Elegant as he was simple, with his Margherita at his side, beautiful and very young too. So, I tell here with pleasure and melancholy of Lorenzo Bandini, the protagonist of a magnificent and poignant adventure in the heart of the Sixties.

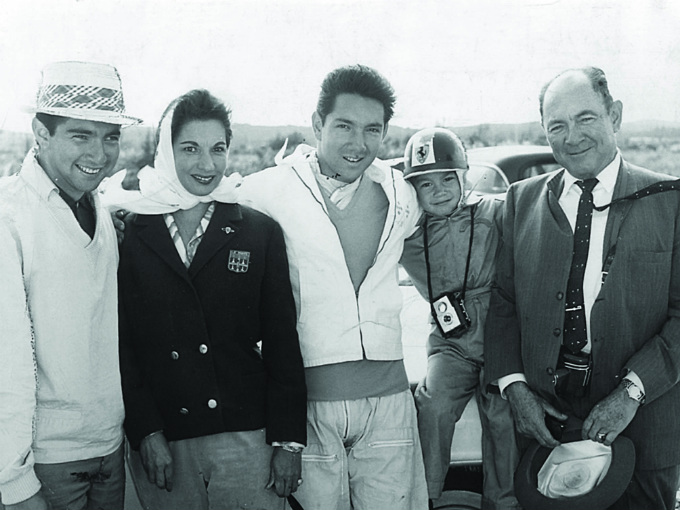

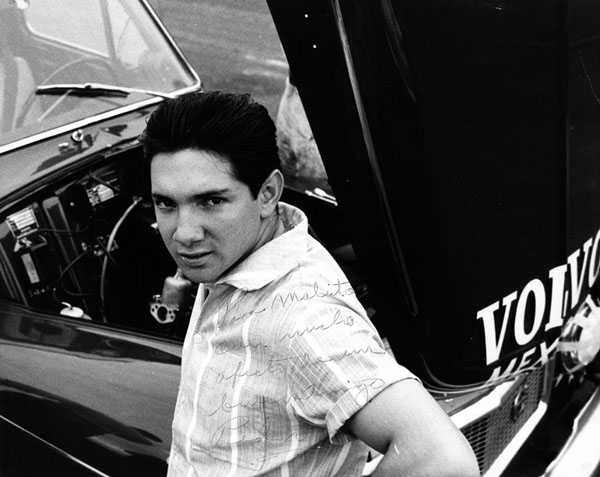

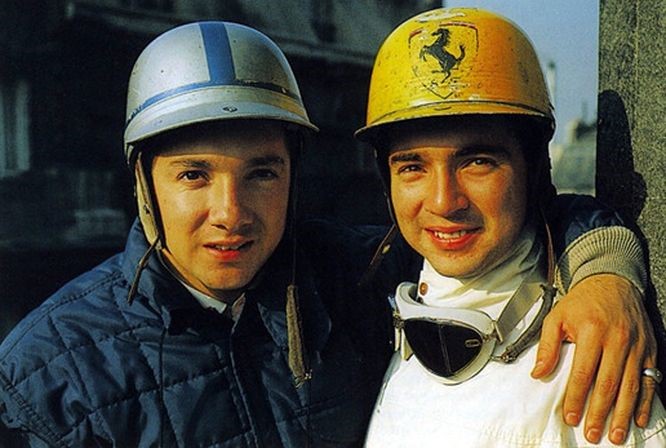

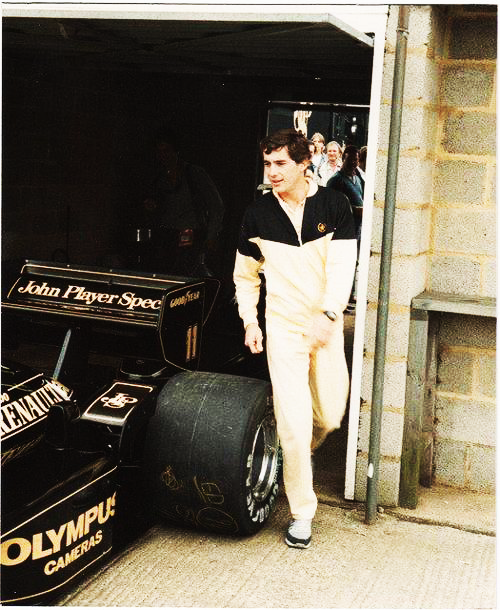

He was born in Libya, in Barce, on December 21, 1935, when Libya was an Italian colony. Not rich, a mechanic, as a boy, in Italy, he moved to Milan in 1950 to work in Mr. Goliardo Freddi's garage. The father of Margherita, in fact, his future wife. A beautiful lady still today, while she walks on life with that wound, a pain that does not go away. Lorenzo, to tell those who don't know, is young, he was like an older brother, a tender son, a loved one. For this reason we cheered for him in many. Including Piero Ferrari, Enzo's son, who still finds himself with something in his throat touching on the topic. Because Bandini, after a typical apprenticeship including Formula Junior, Mille Miglia, bread, salami and some frustration, arrived in Formula 1, debuting in Belgium in 1961.

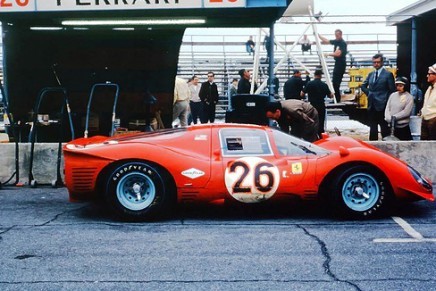

Mimmo Dei, Scuderia Centro Sud, as mentioned. Enough to signal that he is ready, even for a Ferrari. Formula 1, Sports and Prototypes, with a memorable victory at the 1963 24 Hours of Le Mans, paired with the other half of the Italian firmament, Ludovico Scarfiotti.

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari 158, Grand Prix of the Netherlands, Circuit Park Zandvoort, 24 May 1964. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari 158, in Rouen-Les-Essarts in 1964.

Lorenzo Bandini, British Grand Prix, July 09, 1964. Photo by Colin Waldeck / Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

Lorenzo Bandini with Pat Surtees, John Surtees' wife, Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 06 September 1964. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

In the Drivers' World Championship he won only once, in Austria, 1964, the year in which his captain, John Surtees, took the title.

He continued to do great things with covered-wheeled cars, to chew bitter with Grands Prix, between unlucky races and cars that were not winning at all. He smiled, with that very fine tenderness that signals good people, good men. He wanted to do better, more, he was convinced he would take a lot of revenge in 1967, a year that opened with a success in the 24 Hours of Daytona, paired with Chris Amon. Nope, damn it. The accident happened at the chicane.

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari, at the Targa Florio.

Lorenzo, second, perhaps arrived too quickly, the Ferrari hit a bollard, overturned, caught fire, all thinking that he had ended up in the sea. He was in the car, however, trapped in the flames. The images are heartbreaking, as is his agony, the end. While everyone realized that they had lost a part of themselves, something that accompanied a collective dream, a time full of energy, a fresh hope. Date of death: May 10, 1967. There is a sentence from Margherita that counts as a dramatic and final photo: "the number 7 cannot have killed him, but it recurs too often…. It happened on May 7, 1967, he had been racing for 7 years in Formula 1, at 17.07 minutes he was in the wake of Hulme, 17 seconds behind him, there were 17 laps to go when the fact happened. It took them 17 minutes to take him to the hospital, he spent 72 hours of agony in room number 7, he was taken to Milan with a Boeing 727, flight 607, the family tomb was not ready and he had to stay in the Monumentale depot for 17 days, then he was buried in camp 7, niche 7, death certificate from the Princess Grace Hospital of Montecarlo number 7747.”

December 21, 1935: Lorenzo Bandini. 85 years ago one of the most beloved Italian drivers of all time was born, who died following a tragic accident that occurred during the 1967 Monte Carlo GP. Published on 21 December 2020.

Lorenzo Bandini was born on 21 December 1935 in Barce, in the Libyan colony of Cyrenaica, from Italian parents who had gone so far as to seek fortune abroad in the colonies of the reign of Vittorio Emanuele III. After the outbreak of the Second World War Bandini returned to his homeland and, with his family, settled in San Cassiano di Brisighella, a small town near Faenza. Lorenzo spent the first few years in Italy peacefully, as his family, owner of two houses and a hotel run by his father, lived in fairly well-to-do economic conditions.

To ruin everything, in 1940, was the outbreak of the conflict that forced his father to leave his loved ones to go to the front. The hardest moment came in 1944 when Lorenzo was just nine years old: his father suddenly disappeared, only later it was discovered that he had been taken prisoner and shot, while the bombings destroyed that hotel which had costed years of work and sacrifices. The Bandinis suddenly fell into disrepair and the mother, desperate, decided to transfer everyone from San Cassiano to Reggiolo, where she could at least count on the support of several relatives. It was at that time that Lorenzo began working as an apprentice in the workshop of Elico Millenotti, a motorcycle mechanic. After the difficult period of the war, at the age of only 15, the young Bandini already felt ready for the big leap: he wanted to go and seek his fortune in a large northern city. So it was that, in 1950, Lorenzo decided to join his sister Gabriella in Milan. Thanks to his audacity, he immediately managed to find work in the Garage Rex in via Plinio.

In many ways, this opportunity represented one of the most important turning points in his life. The owner of the garage, Goliardo Freddi, the father of his future wife Margherita, represented for him that father figure that fate had taken away from him in the difficult years of the war. Goliardo Freddi began to love him like a son and to take him with him to the races that were held in Monza. It was thanks to him that Lorenzo began to love the world of motors. In that period he began to know the great names of motoring, from Alberto Ascari to Juan Manuel Fangio, up to the legend of Tazio Nuvolari. For a few years Bandini continued to work as a mechanic and became increasingly good at his job but, over time, his passion for racing made him develop a great conviction: that of starting to race and imitating those great myths that, from time to time, occasionally he went to admire in Monza. Goliardo Freddi never hindered him in achieving his goals, on the contrary he was always present in times of difficulty and proved to be a great support for him.

In 1956, when Lorenzo firmly decided he wanted to start competing, Freddi did the best he could to help him. He lent him his car, a two-tone Fiat 1100 TV, to sign up for the Castell’Arquato – Vernasca race. This is how Lorenzo Bandini's competitive career began. A career that, like the first competition he raced, would have been all uphill. In fact, Lorenzo, unlike other great drivers of the time, did not immediately have the opportunity to get noticed by important circles and only reached the major categories after years of training and many sacrifices. In his first race he finished fifteenth, but he was not discouraged because he understood that it took time before he could achieve success. So he started racing in all the races in which he could participate not worrying too much about the result, but with the aim of learning and gaining experience. After the twenty-third place at the Bolzano - Mendola and the second position at the Garessio - San Bernardo, the first long-awaited success came at the Lessolo - Alice. They were two years full of competitive commitments in which he participated in time trials of a certain importance and began to make a name for himself, managing to weave a dense network of acquaintances and friendships. At that time, after taking part in the Trento - Bondone and Pontedecimo - Giovi races, he started racing with a Fiat 8V, a wonderful 2-liter which was then considered one of the most beautiful racing cars.

The first really significant success came two years after the start of his career, in 1958, when, driving a Lancia Appia coupé, he finished first in class, in the 2000 Gran Turismo, at the Mille Miglia. After participating in the prestigious endurance marathon, Bandini was on the lowest step of the podium at the Sicilian Gold Cup with a Volpini Junior. 1959 was perhaps the most intense year in terms of races he attended because Lorenzo, driving a Stanguellini, did not miss a single appointment throughout the season. He once again came third in the gold cup in Sicily and was first in the category in the "Madunina" Cup and in Innsbruck. Later he again participated in the "Sant'Ambroeus" Cup, the Sassari circuit, the Junior Cup in Monza, the Pontedecimo - Giovi, the Catania - Etna, the Shell Cup in Rome, the Montecarlo Junior Grand Prix, the Grand Prix of Pau and in the Crivellari Junior Trophy. They were tough races, at times marked by unfortunate retirements while, on other occasions, they were embellished with good placings. But Lorenzo's goal was to keep racing and accumulate as much experience as possible.

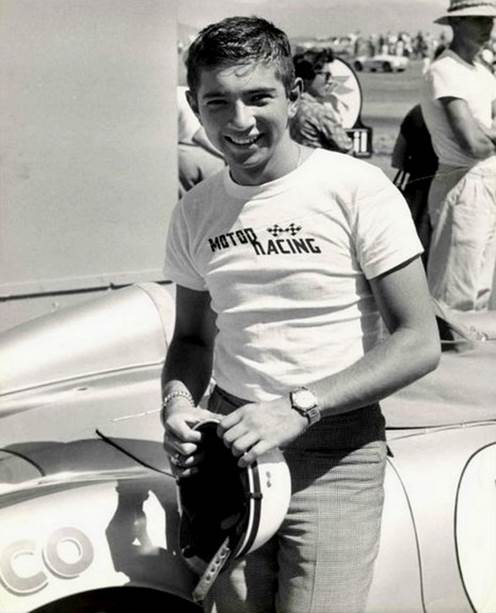

His tenacity was finally rewarded in 1960, when he became an official Stanguellini driver. Two great victories immediately arrived, at the Grand Prix of Freedom in Cuba and at Monza, where he met another young motor enthusiast, Giancarlo Baghetti. The season continued like this between ups and downs and it was at that time that Bandini realized how difficult it was, despite his commitment, to be able to distinguish himself from the immense group of good gentleman drivers who tried their hand at car racing. However, the big opportunity came in 1961. Ferrari would have made one of its cars available to a promising young man who proved to live up to the prestigious name of the Maranello team. For Lorenzo that place became the main goal, the dream to be realized, perhaps the only way to be able to reach the golden world of Formula 1. The commitment was enormous and, once again, it was rewarded because Bandini got the first place absolute in Monza on the occasion of the Junior Cup. Shortly after the announcement of the name of the lucky driver who would sit in a Ferrari, that victory gave Bandini great hopes. Unfortunately, the dreams of glory turned out to be in vain because Enzo Ferrari's chosen one was Giancarlo Baghetti, who would later prove to be Bandini's eternal friend and rival in the years to come. The disappointment for the young Lorenzo was burning but, if the Commendatore had preferred another one, there was still someone who had noticed him. That someone was called Mimmo Dei, owner of the Scuderia Centro-Sud. It was he who offered Bandini a seat in one of his single-seaters, a rear-engined Maserati Cooper 1500.

The debut in Pau was very good, with third place behind the almost unbeatable Lotus Climax driven by Jim Clark and Joakim Bonnier. Given Bandini's more than positive performance, Dei decided to enroll him in the first Formula 1 Grand Prix that would be raced in Belgium on the Spa-Francorchamps circuit. Thus, on June 18, 1961, the young Italian made his debut in the top open-wheel category. However, it was not a lucky debut, because Lorenzo was forced to a sad retirement. Just after that race, Mimmo Dei decided to entrust the front-engined Ferrari 250 Testarossa that Enzo Ferrari kindly granted to the Centro - Sud team to the talented Brisighella. With that car Lorenzo, paired with Giorgio Scarlatti, won a fantastic victory at the 4 hours of Pescara and that success, one of the many arrived in the long years of apprenticeship, finally represented the right opportunity and consequently numerous teams began looking for him. Enzo Ferrari himself who, without saying anything had followed him throughout 1961, began to take him seriously in order to offer him driving one of his cars. The call came in December of the same year and Lorenzo finally made his own that seat he had dreamed of for years. On that occasion Mimmo Dei proved to be a great man even before being an excellent manager and, realizing how important an offer of that kind was, he let Lorenzo leave despite the contract binding him to the Centro - Sud again for the whole following year.

Bandini became an official Ferrari driver for 1962 and it was a very positive season. His debut took place at the Pau Grand Prix, where he finished fifth, while at the Targa Florio he finished second paired with Giancarlo Baghetti. Lorenzo had an incredible desire to show Enzo Ferrari all his value and his results did not prove him wrong. He won the Mediterranean Grand Prix and the Enna Grand Prix, finishing third at the Monte Carlo Grand Prix. Needless to say, Bandini's new goal had become to be an official Cavallino driver in the top flight, that is in Formula 1. Ferrari, despite his efforts, showed that they still did not have full confidence in him and this was confirmed in 1963 when the team, looking for a man to work alongside John Surtess, preferred Willy Mairesse. Unfortunately, only an accident involving the latter would have opened the way. Lorenzo did not yet feel the full support of the team and the period was characterized by various ups and downs, with Bandini who divided himself between the Mondiale Marche raced with Ferrari and that of Formula 1 where he gained experience driving the Cooper-Maserati and the BRM. It was precisely in that difficult phase of his life that a prestigious and extremely important success for his future arrived. In 1963, driving a Ferrari 172P and paired with Ludovico Scarfiotti, he won one of the most important car races, the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Reassured by such a sparkling success, things began to take a decidedly positive turn. In fact, good placings followed one another, in the Reims Grand Prix, the Auvergne Trophy, the Silvertone Grand Prix, the Solitude Grand Prix, Pergusa, the United States and South Africa. All these performances earned him the important title of "Absolute Italian Champion" at the end of the year.

At that point Ferrari could no longer remain indifferent to Bandini's performances and, therefore, Lorenzo became the official driver of the Cavallino in Formula 1, alongside John Surtess, for the 1964 season. The first year in the World Championship proved to be very positive and, on 23 August 1964 at Zeltweg, Bandini won his only career Grand Prix. Another equally important performance for Ferrari came in the final race of the season, in Mexico, when Lorenzo was able to keep behind Graham Hill, teammate Surtess's main opponent in the championship, throughout the race. Also thanks to the contribution of Bandini, the former English centaur managed to graduate for the first time Formula 1 World Champion. At the end of 1964, all these feats earned him the second consecutive title of "Absolute Italian Champion".

1965.

1965 was not a very brilliant year, in which the only positive result remained the victory obtained at the Targa Florio paired with Nino Vaccarella. It was a difficult season in which the Lotus-Clark duo proved unapproachable for anyone, with Lorenzo not going beyond the second place in the Monte Carlo Grand Prix. His second best result came in Monza, when he finished fourth in the Italian Grand Prix in a championship that saw him finish only sixth in the overall standings. At the end of a year that was not very encouraging in itself, also came the heavy judgement against him from Enzo Ferrari, who probably at that moment considered him no different from one of the many young talents present on the national motoring stage: "for now we have a driver and a half: given that the test engineer Parkes works with us, bound until 1967 and also assuming that we have a driver, John Surtees, now unfortunately injured and who is engaged with us until December 1966, we declare ourselves available to train, as we have already started, Italian drivers. Bandini is like another, we will continue to make him race, we will continue to try him. If Bandini goes faster than the others, obviously he will always race. When you have two cars you have to entrust them to the two who go faster: with this I don't mean to underestimate Bandini, but I don't mean to create immovability for anyone who races in a Ferrari either. We will put above those who will give us greater trust.”

So, for Bandini, all those races and victories were not enough to be considered a staple in the team. But, for the umpteenth time in his life, Lorenzo did not give up in the face of the first difficulty and responded in his own way, that is on the track.

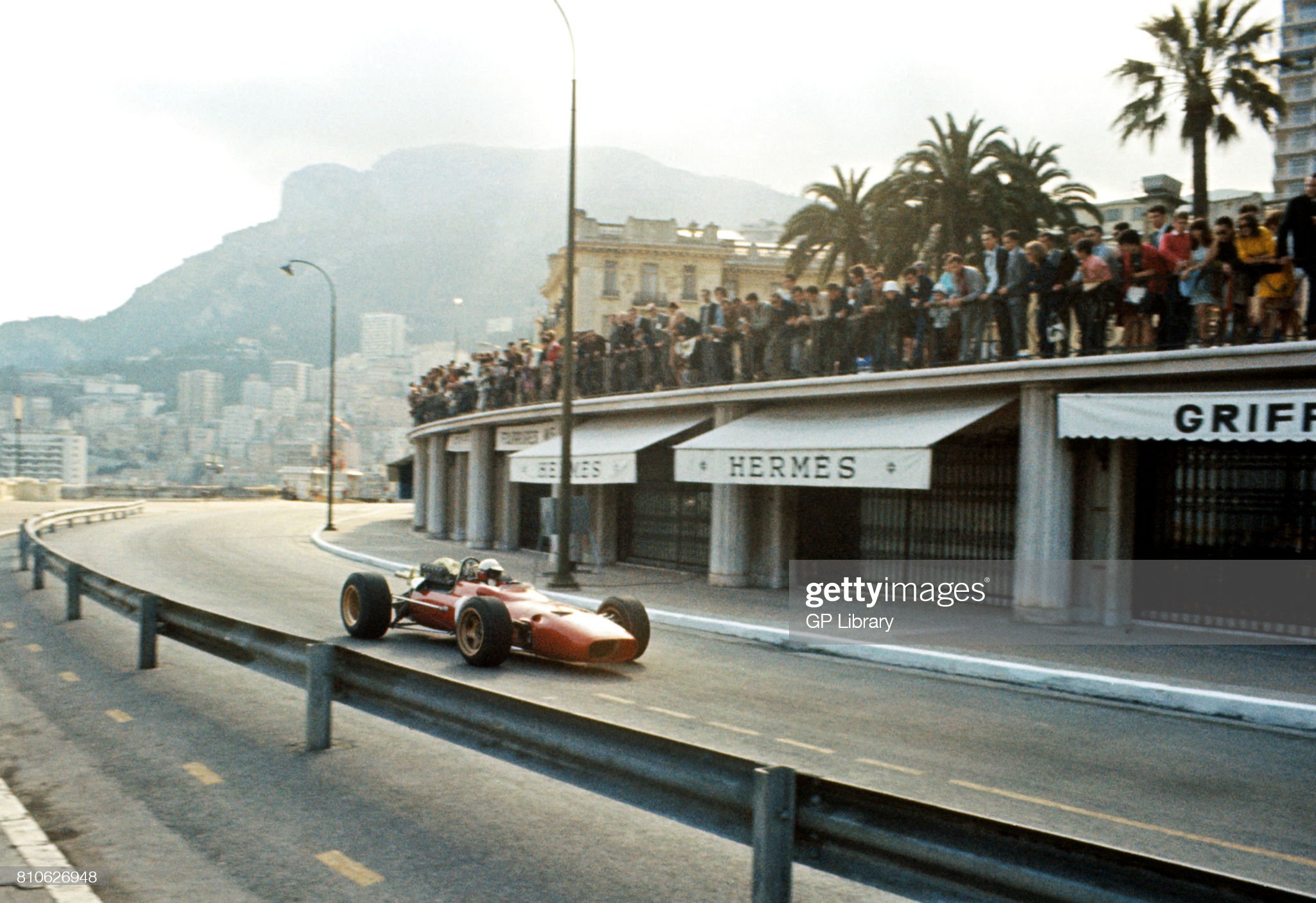

Lorenzo Bandini driving a Ferrari 312 at the 1966 Monaco GP. Photo by: GP Library / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

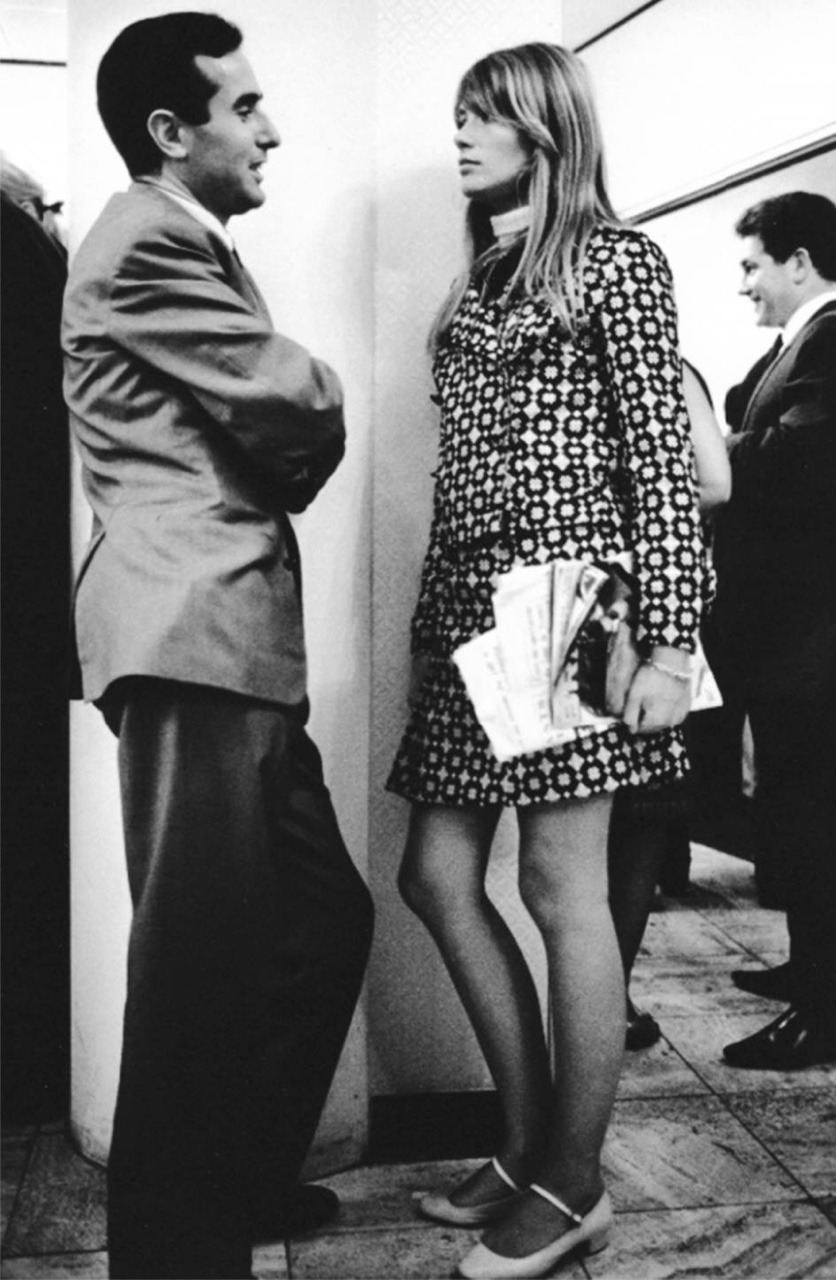

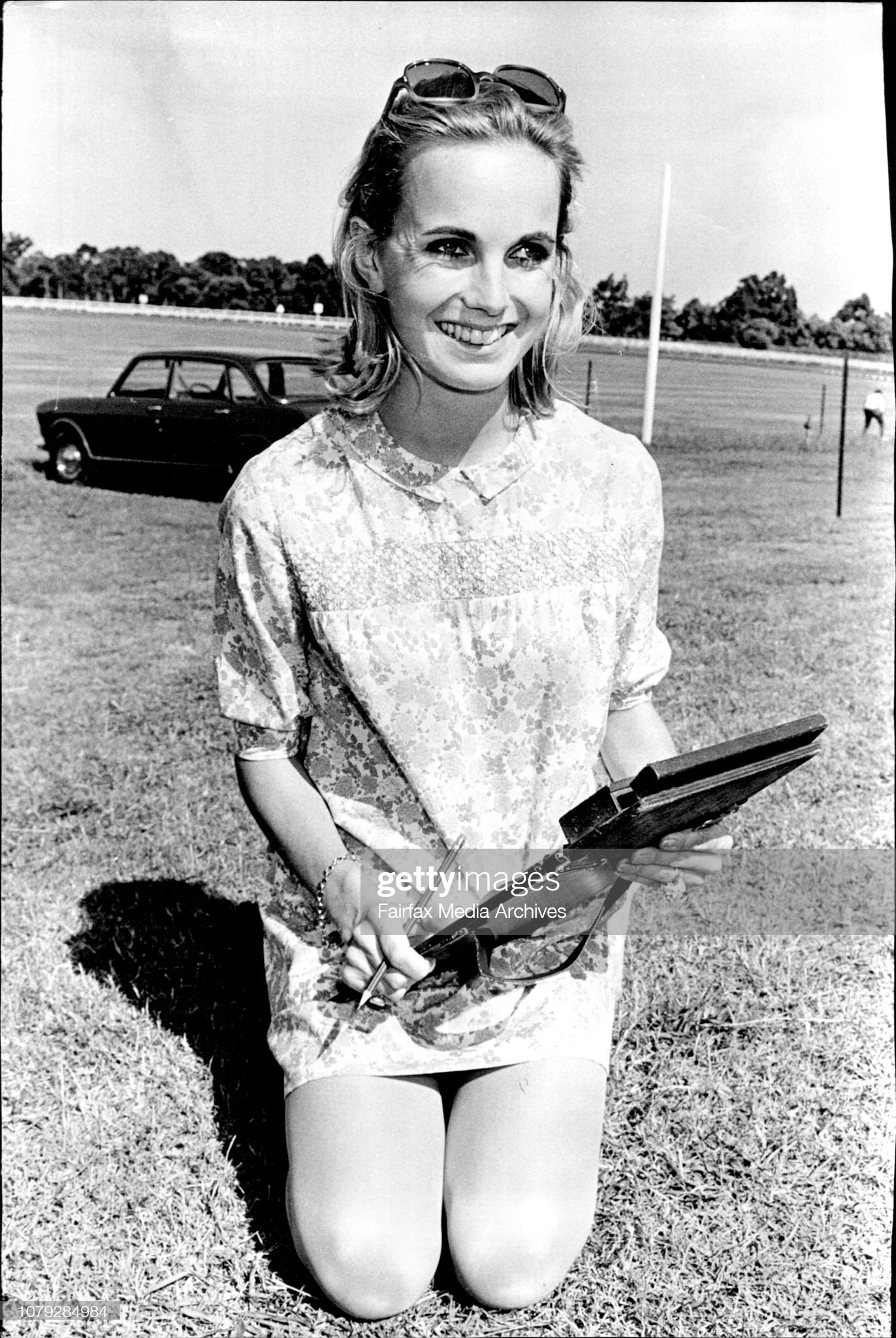

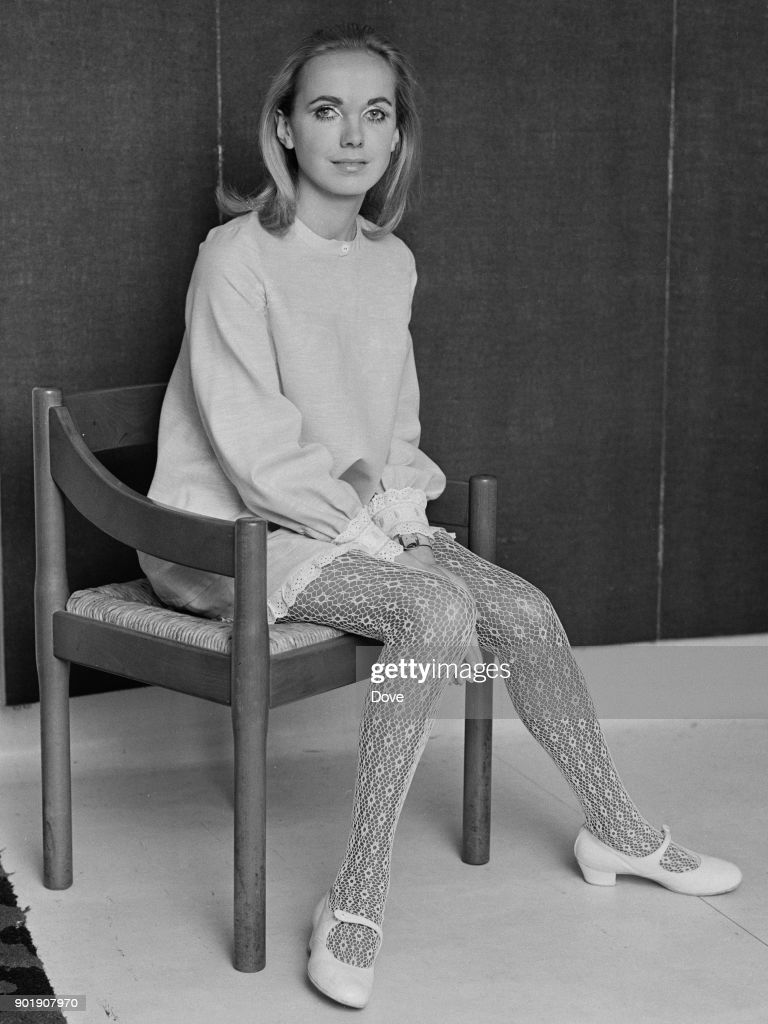

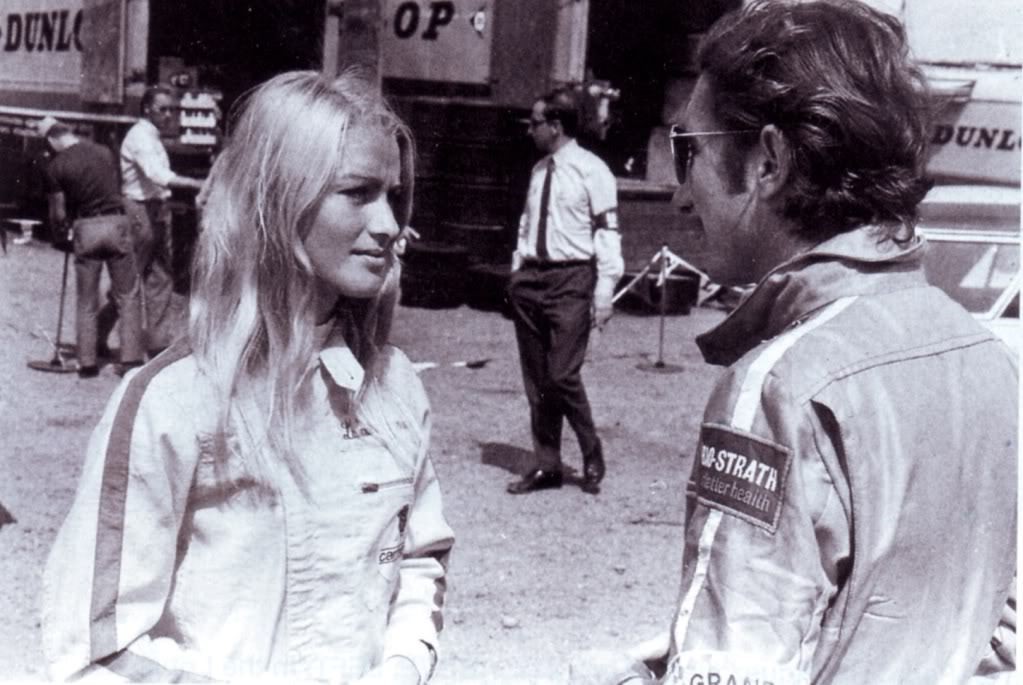

Lorenzo Bandini and Françoise Hardy at the Bouwes Palace Hotel, Zandvoort, in July 1966.

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari, at Nurburgring in 1966.

In 1966 the third place in Monte Carlo and the second in the Belgian Grand Prix suddenly threw him at the top of the world rankings making him one of the main favorites for the title, even if a bad result at the Reims Grand Prix affected him negatively. In the end the championship went to the expert Jack Brabham and for Lorenzo even that season ended "only" with yet another victory of the title of "Absolute Italian Champion".

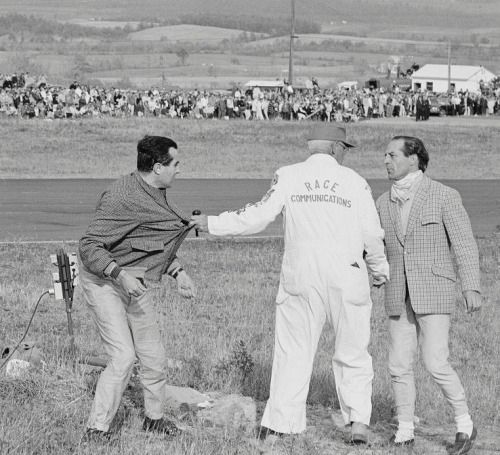

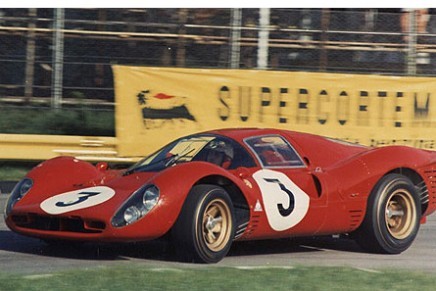

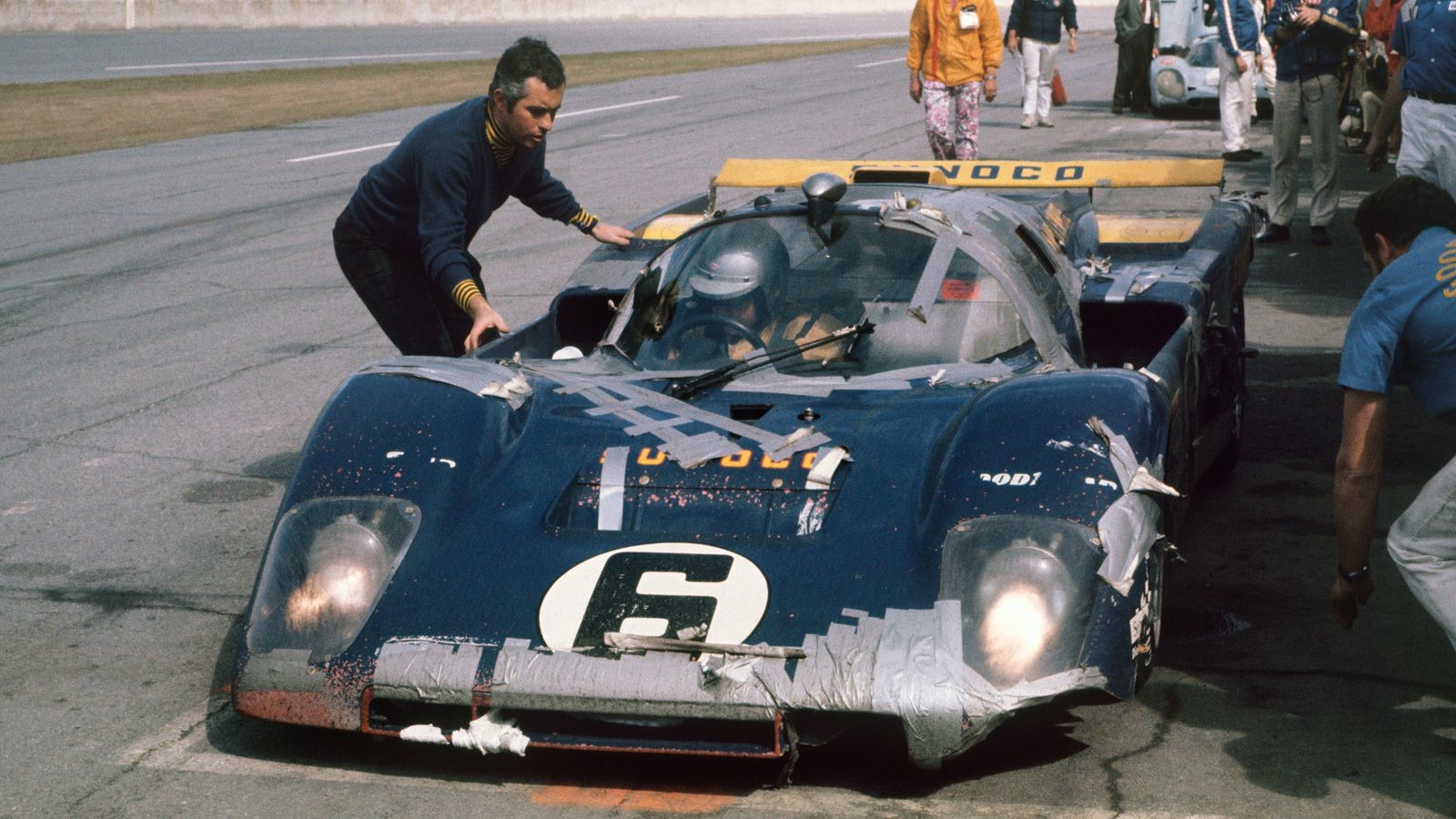

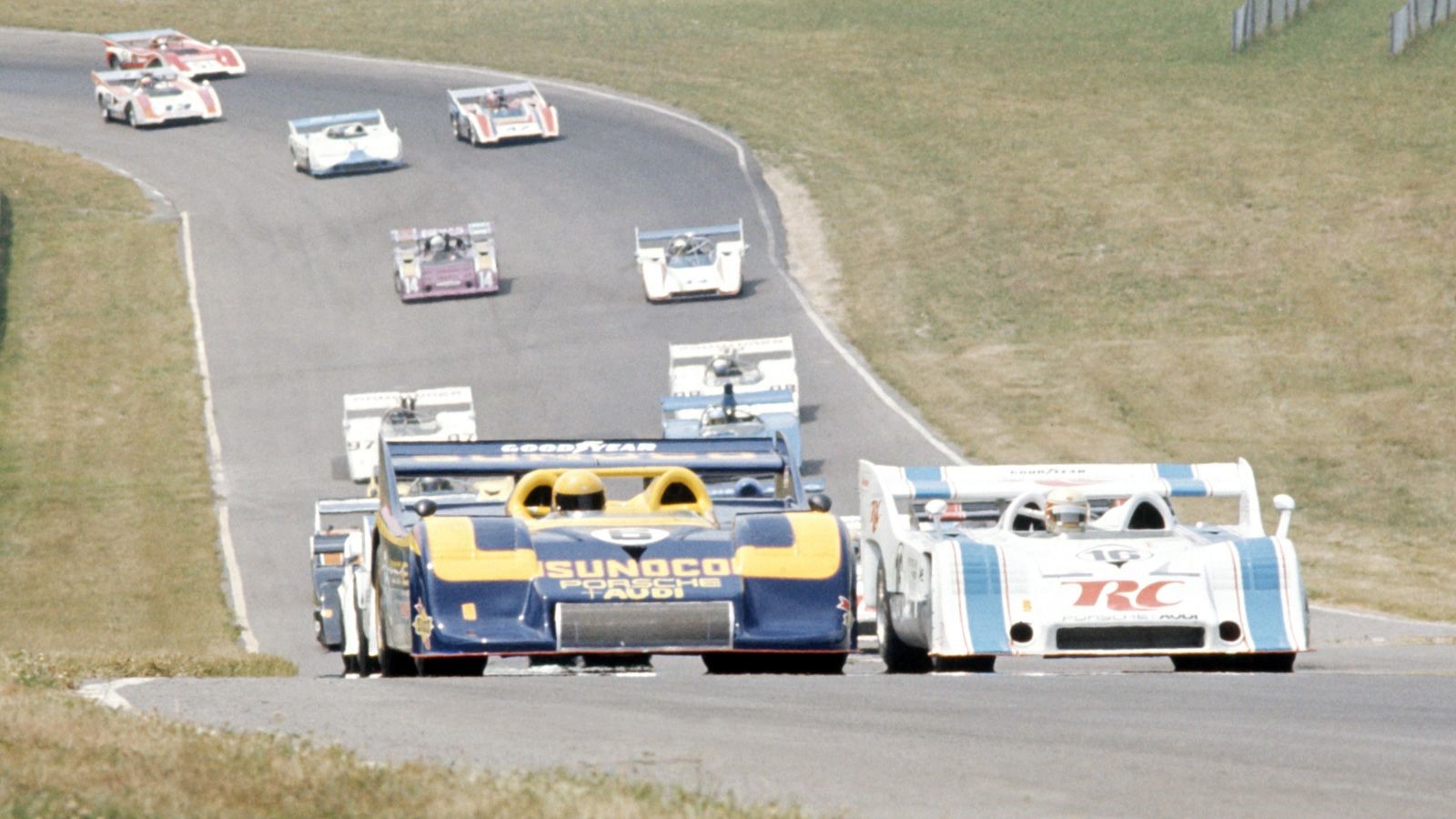

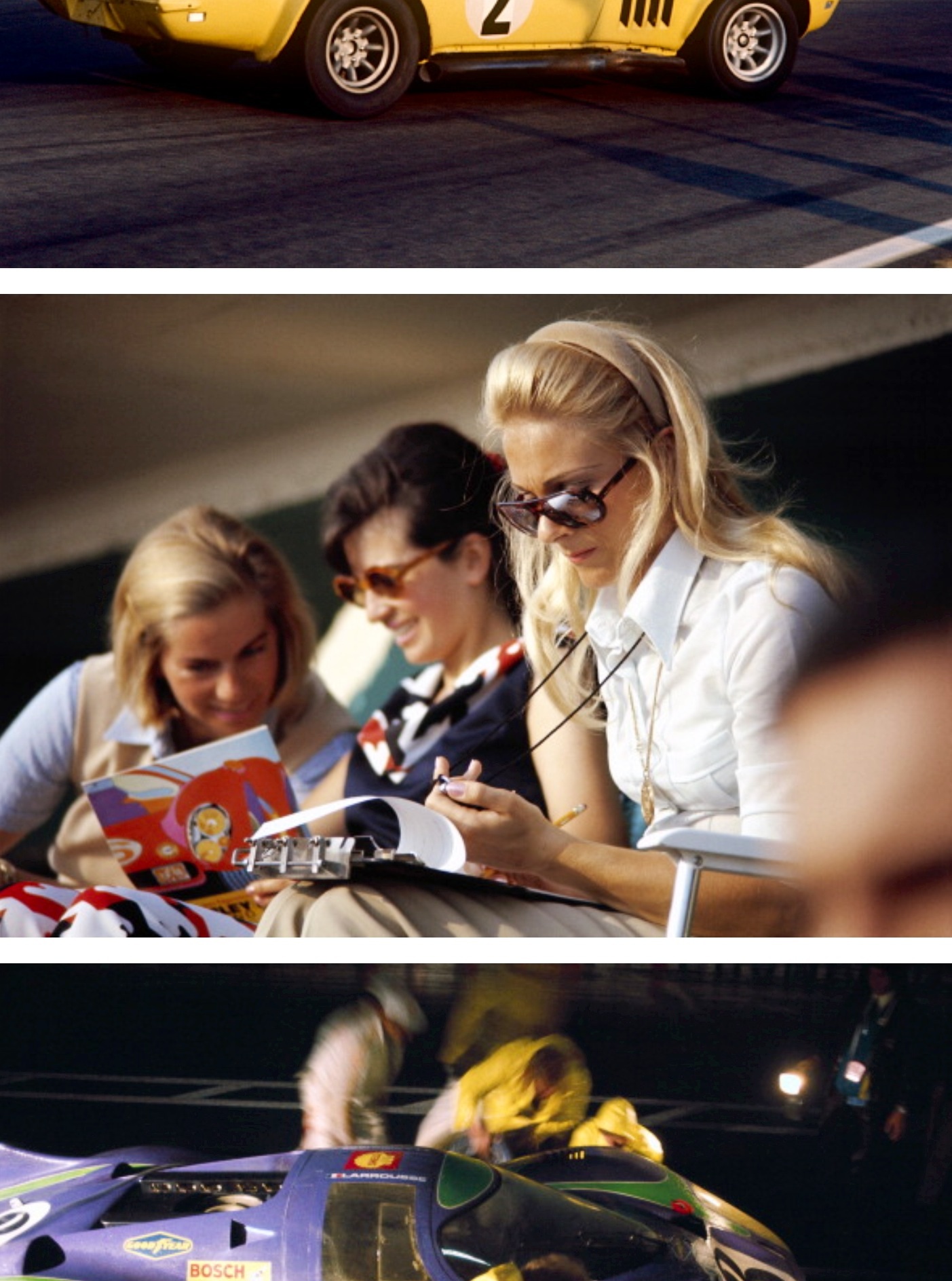

United States, February 05, 1967, Daytona 24-Hour Race. Race winners Chris Amon and Lorenzo Bandini of Ferrari celebrate their victory. Amon and Bandini started the race fourth on the grid and did 666 laps in the 24 hours in their Ferraris 330 P3. Photo by Bob D'Olivo / The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images.

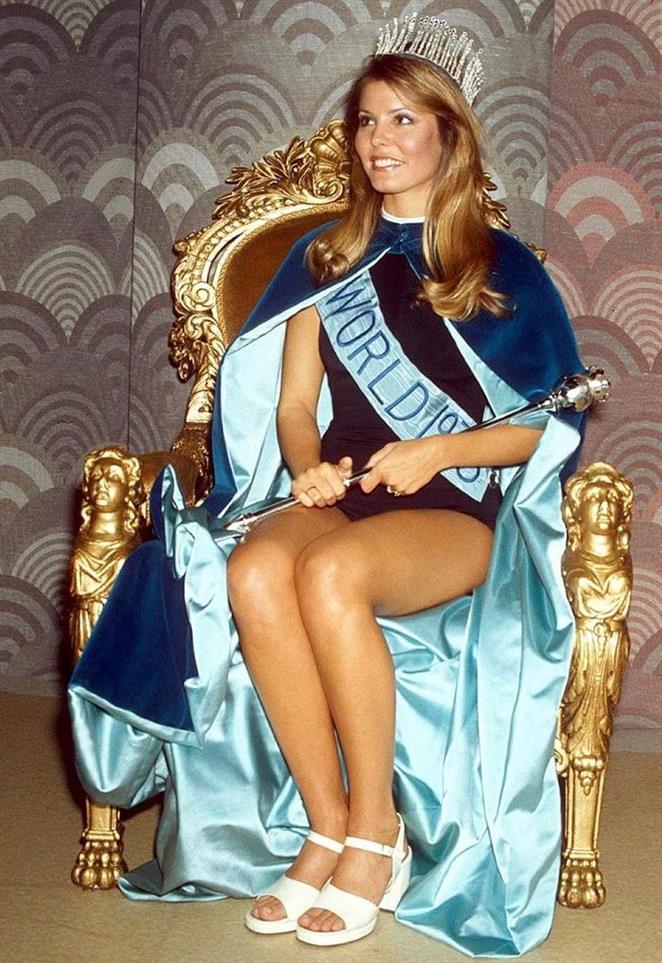

Daytona Beach, Florida, February 05 1967. Lorenzo Bandini (left) and Chris Amon won the Daytona 24 in a Ferrari 330 P4. The trophy queen is Winkie Louise. Photo by ISC Archives / CQ - Roll Call Group via Getty Images.

Lorenzo Bandini and Chris Amon being congratulated by Miss Firebird 1967, Edwina “Winkie” Louise, at the Daytona 24 Hours on 05 February 1967.

Even by today's standards of beauty Miss Edwina "Winkie" Louise would be considered a beauty. When the legendary Linda Vaughn decided to abdicate her title of Miss Firebird and become Miss Hurst Golden Shifter Winkie Louise stepped in and assumed the title. The picture was taken at Daytona in 1966, almost 50 years ago.

Lorenzo Bandini in February 1967.

For Bandini 1967 got off to a great start with two resounding victories. The first at the 24 Hours of Daytona and the second at the 1000 Km of Monza, both paired with Chris Amon, at the wheel of the beautiful Ferrari 330 P4. Lorenzo became the first Ferrari driver and realized that, after years, he had finally won the trust of the whole team and of the Commendatore. At that moment he was the top man of the Red team, the driver who had become the darling of all the Cavallino fans. It seemed to be finally the right year, the season of his consecration. Bandini did not feel inferior to any rival of the other teams and the only one he seriously feared was the second Italian in the team, Ludovico Scarfiotti, especially after the latter's victory the year before in Monza. As Enzo Ferrari would later declare, Bandini saw in Scarfiotti everything he had missed in his youth. Scarfiotti came from a wealthy family and had always been able to face his career in a calm, autonomous way, without too many worries. On the contrary, Lorenzo came from the mess tin and had sweated the much-needed Ferrari seat. With that climate and pressure on him, Bandini turned up at the highly anticipated Monaco Grand Prix, the first race after a long break following his debut at Kyalami. The only street circuit left on the Formula 1 calendar together with that of Pau in France.

That day, May 07, 1967, the Principality track was packed with people. Over one hundred thousand spectators arrived in Monaco to follow one of the best races of the season. Bandini's start was perfect and the Italian immediately took the lead, gaining almost two seconds over Denis Hulme in the first lap. However, Lorenzo remained at the head of the Grand Prix for only a few laps because, after a few laps, he lost several positions following a spin on the oil left on the track by Jack Brabham, himself a victim of engine problems. Lorenzo was passed by Hulme and Jackie Stewart and slipped to third place, managing to stay ahead of a fierce group formed by Surtess, McLaren and Clark. That unfortunate and apparently harmless episode would have been paid dearly by Bandini. In fact, from that moment on, Lorenzo began to go faster and faster, convinced that he could catch up with that victory that no one would have been able to snatch from him without that wildfire. Later, thanks to Stewart's retirement, the Cavallino driver climbed back to second place, just over seven seconds from the top. To divide him from Hulme, however, there were also two lapped drivers, Rodriguez and Graham Hill. The former immediately stepped aside while the latter, who perhaps had not yet forgotten the incident that occurred in Mexico a few years earlier, hindered him for two laps making the gap from the leader rise to 12 seconds. After having overtaken the English driver Bandini appeared visibly tired, so much so that the delay continued to rise, passing between the 65th and 80th laps from 12 to 20 seconds. Lorenzo was driving down lap 82 when his Ferrari arrived at the chicane after the tunnel at an inexplicable speed, far exceeding that with which one would normally tackle that corner. The driver could do nothing more to control the car, which began to bounce several times from one side of the track to the other before rising into the air and capsizing. The car, already in flames and upturned, continued to crawl on the asphalt for over thirty meters and everyone immediately realized the severity of the accident.

8th May 1967, Monte Carlo, France, Monaco Grand Prix, Lorenzo Bandini loses control of his Ferrari and crashes into a lamp-post in a dreadful accident. Photo by Paul Popper / Popperfoto via Getty Images.

9th May 1967, Lorenzo Bandini in a Ferrari crashes and the car begins to roll over after hitting the straw bales after losing control at the chicane, The straw from burning oil and the car became a fireball. Bandini survived the crash but had severe burns, also the overturned car had crushed his chest and he succumbed to his injuries and died 3 days later. Photo by Bentley Archive / Popperfoto via Getty Images.

The Monaco Grand Prix, Monte Carlo, May 07, 1967. Chris Amon in the remaining Ferrari passes the horrifying crash of his teammate, Lorenzo Bandini. Bandini had clipped the chicane and his car was thrown across the track into the straw bales in front of the harbor which caused it to overturn and catch fire. The well-liked Italian succumbed to his injuries and burns three days later. Photo by Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

9th May 1967, Italy's Lorenzo Bandini in a Ferrari crashes after losing control at the chicane and the car ignites the straw bales causing a fireball, A man can be seen trying to retrieve a wheel which had broken away in the accident. Photo by Bentley Archive / Popperfoto via Getty Images.

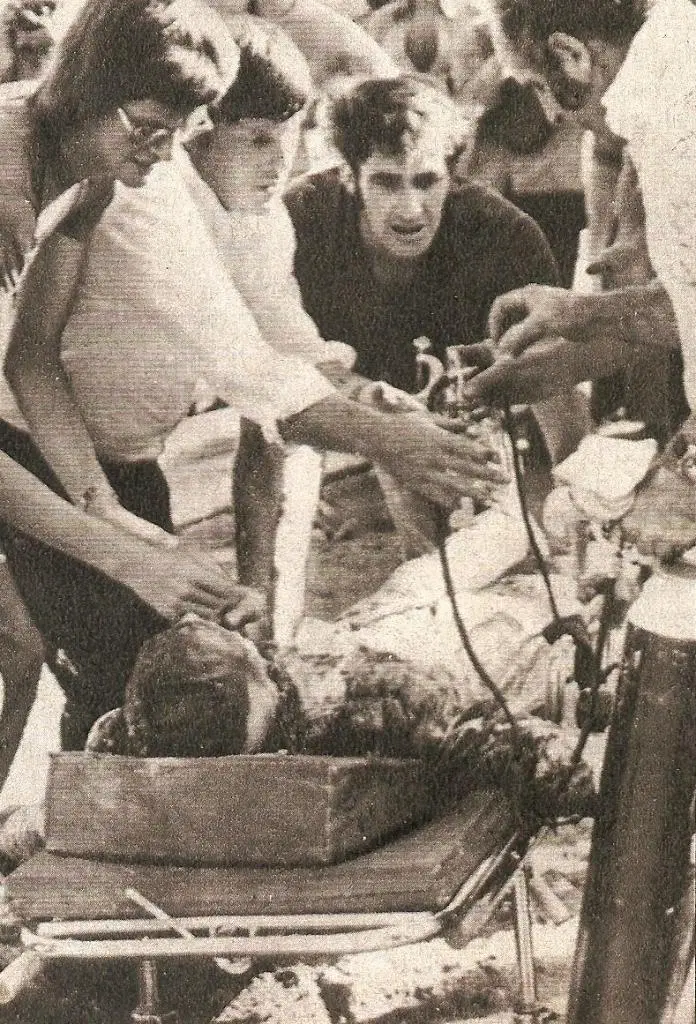

The commissioners immediately tried to understand where the Italian driver was, convinced that he had been thrown out of the cockpit during the crash. A completely legitimate fear because, at that time, there was still no obligation to use seat belts. They immediately looked inside the quay and checked that he had not ended up in the sea as had happened to Alberto Ascari several years earlier. Only after about three minutes, which were needed to put out the flames, they noticed the state of things. Bandini was still inside the cockpit, with his face completely disfigured and his suit full of burns. The Ferrari n. 18 was immediately overturned by two commissioners and two civilians, the Prince of Bourbon in a white silk shirt and Lorenzo's friend, Giancarlo Baghetti, who immediately rushed to the scene of the accident.

Lorenzo Bandini being removed by his car. Shutterstock.

The pilot's body was immediately extracted and transported urgently to the hospital in Monte Carlo.

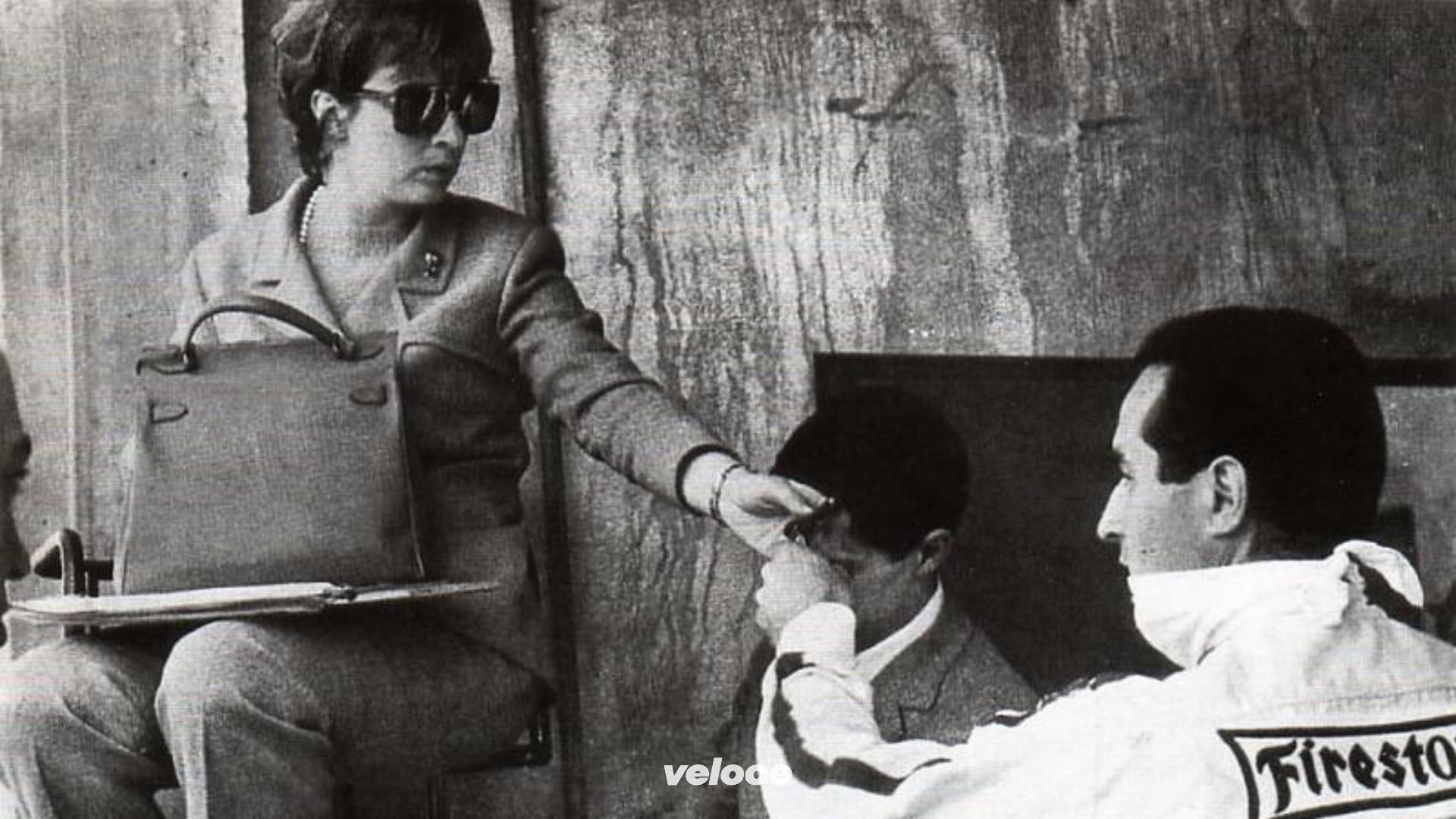

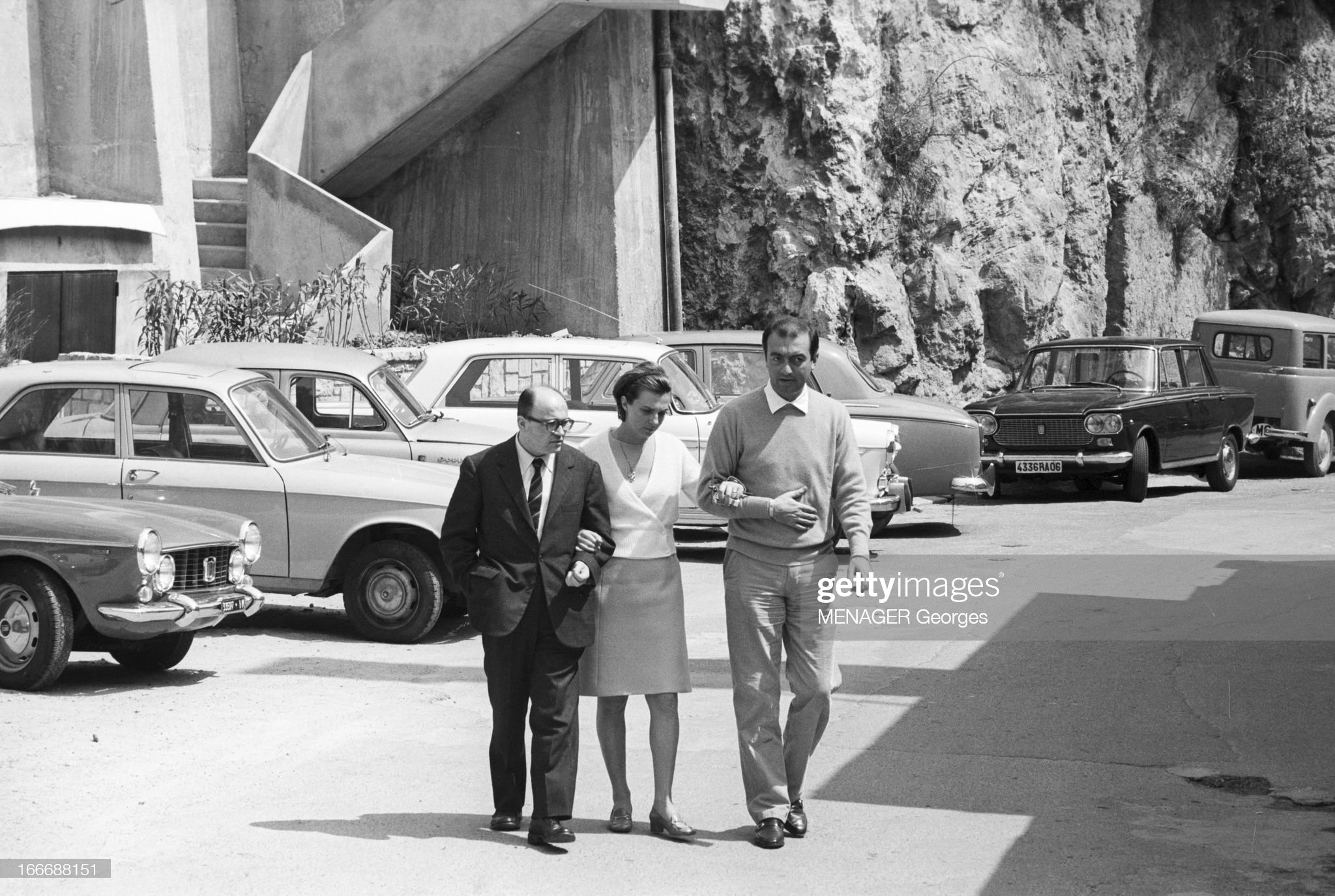

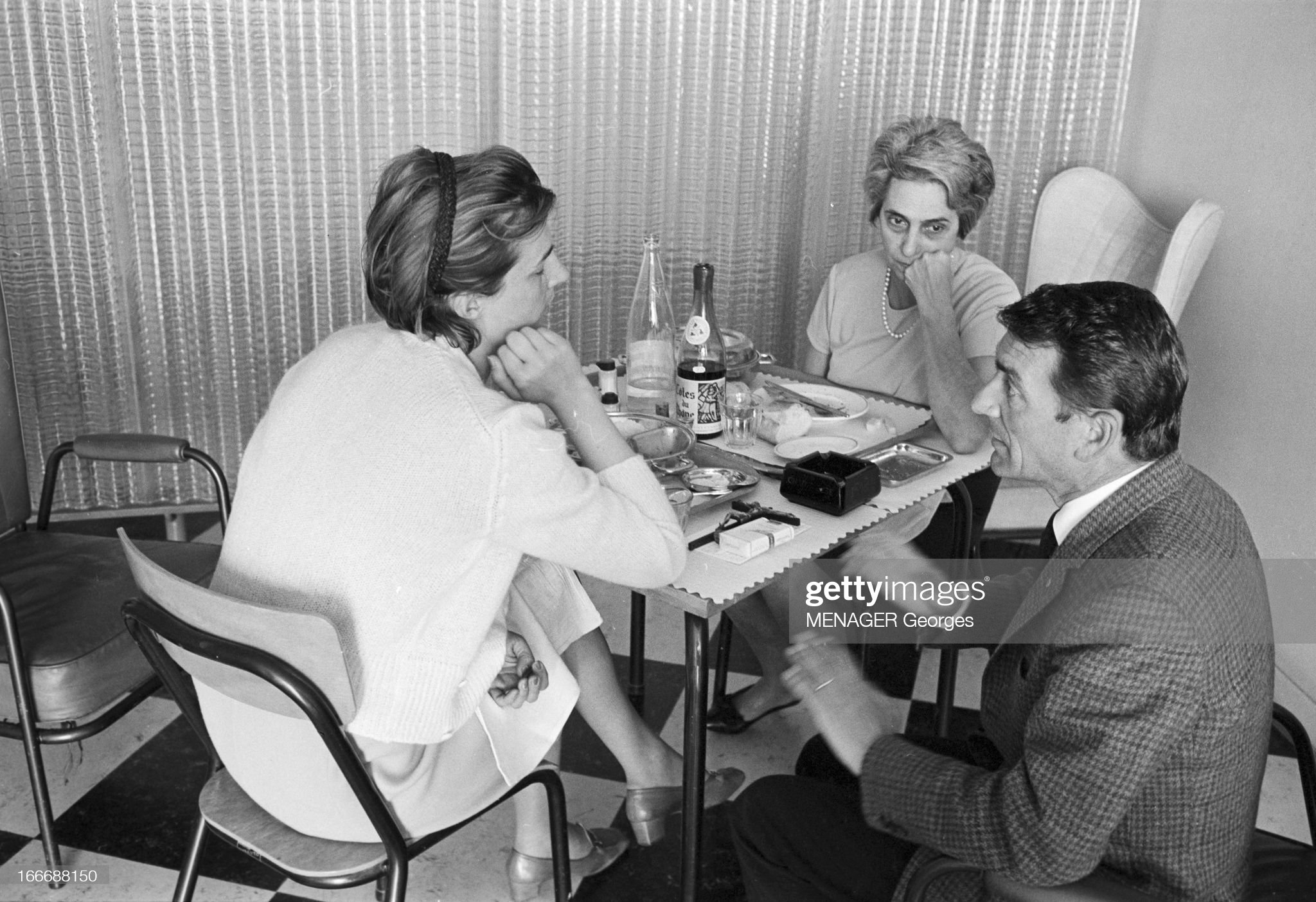

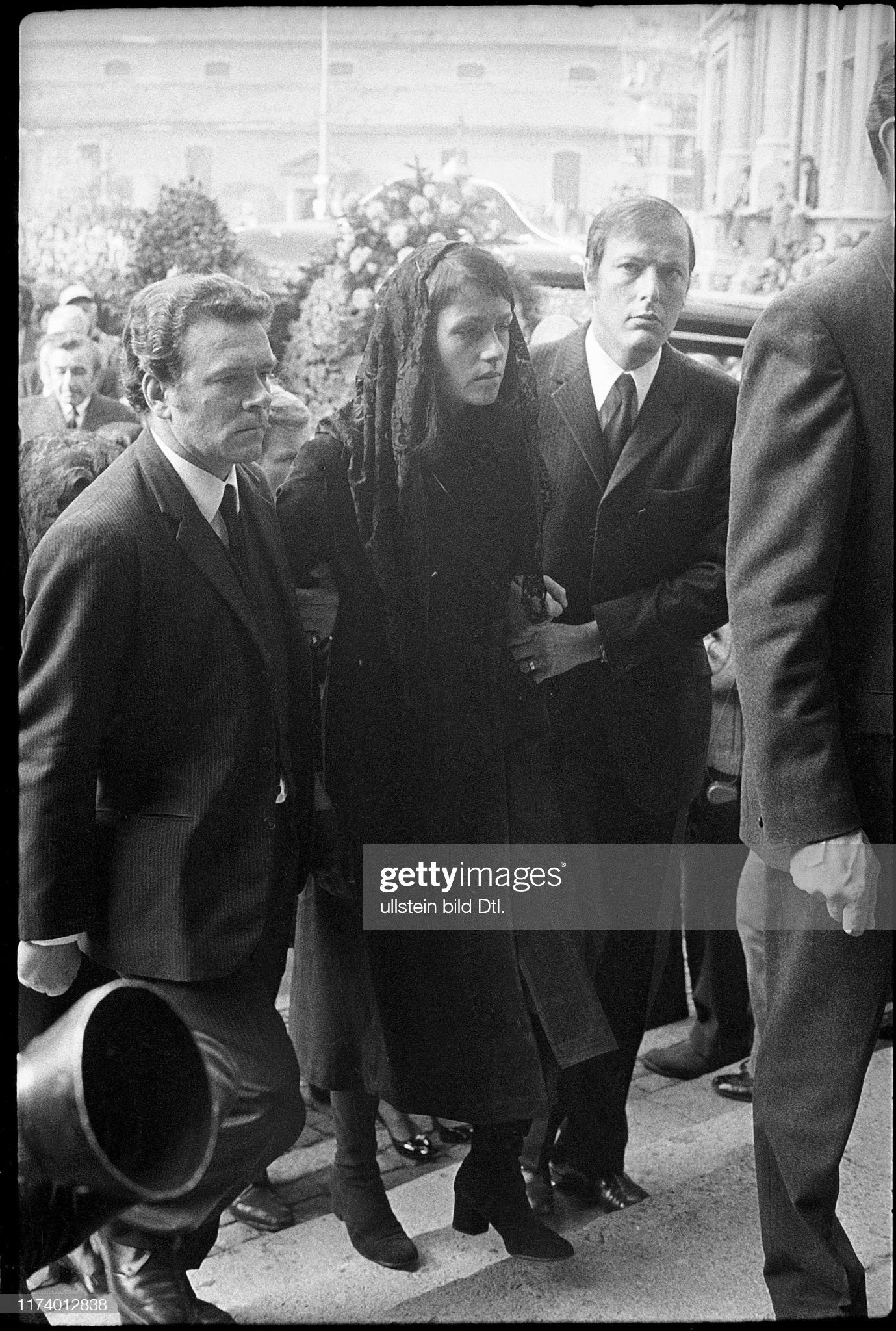

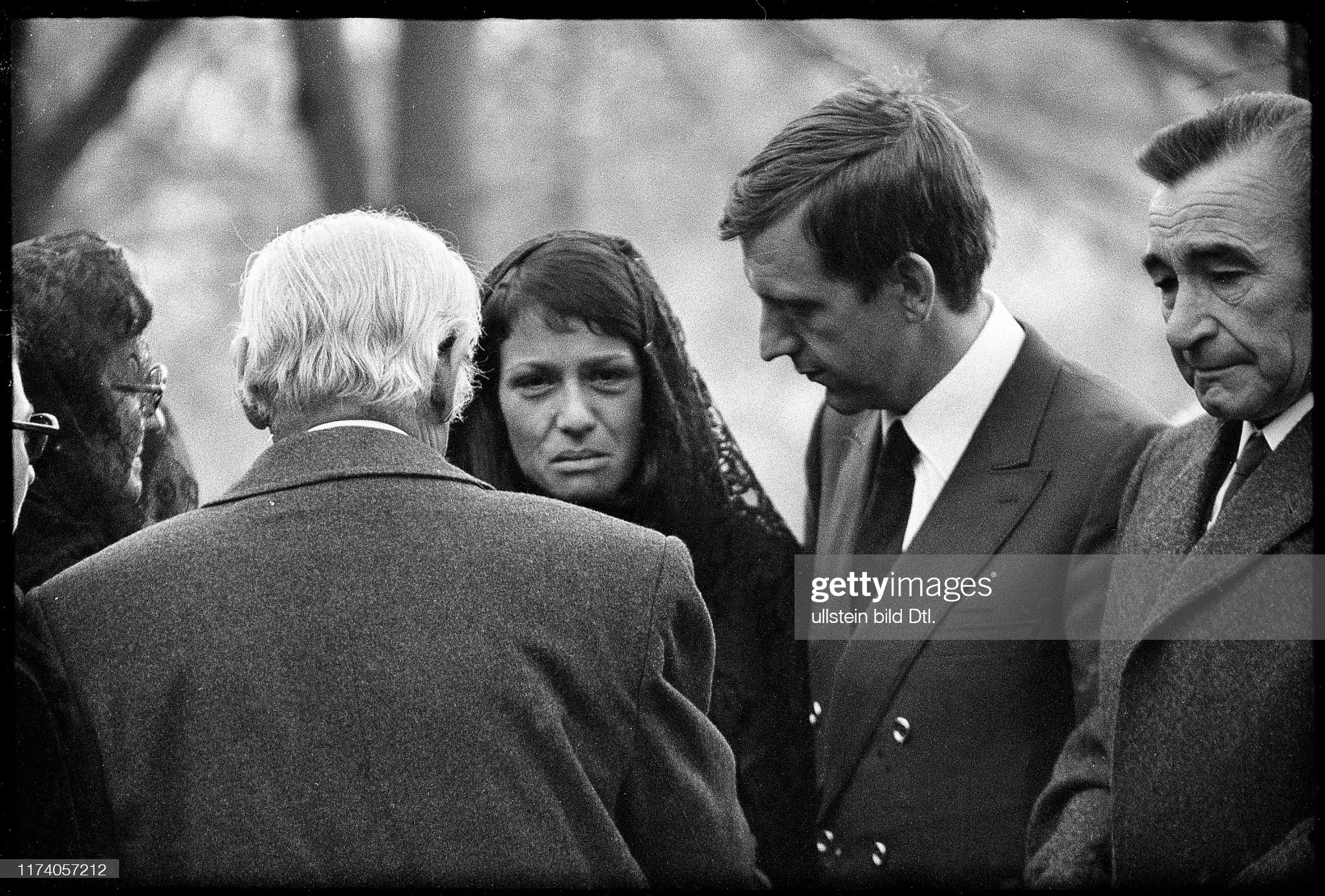

In May 1967, during the Monaco Grand Prix, the Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini, in a Ferrari 321, had an accident in the Principality and was transported to the Princess Grace Hospital where his wife Margherita came to visit him supported by friends. Photo by Georges Menager / Paris Match via Getty Images.

In May 1967, during the Monaco Grand Prix, the Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini, in a Ferrari 321, had an accident in the Principality and was transported to the Princess Grace Hospital. His wife Margherita anxiously awaited the doctors' verdict. Photo by Georges Menager / Paris Match via Getty Images.

In May 1967, during the Monaco Grand Prix, the Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini, in a Ferrari 321, had an accident in the Principality and was transported to the Princess Grace Hospital. His wife Margherita anxiously awaited the doctors' verdict. Photo by Georges Menager / Paris Match via Getty Images.

In May 1967, during the Monaco Grand Prix, the Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini, in a Ferrari 321, had an accident in the Principality and was transported to the Princess Grace Hospital. His wife Margherita anxiously awaited the doctors' verdict. Photo by Georges Menager / Paris Match via Getty Images.

In May 1967, during the Monaco Grand Prix, the Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini, in a Ferrari 321, had an accident in the Principality and was transported to the Princess Grace Hospital where his wife Margherita came to visit him supported by a friend. Photo by Georges Menager / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Upon arrival at Princess Grace's emergency room, the gravity of the situation was immediately understood: the metal sheets had entered his left side causing injuries to his spleen and lung, while over 60% of his body was covered with severe burns. Bandini underwent emergency surgery to remove his spleen, but it was mainly due to the damage caused by the flames that the unfortunate Italian driver was unable to survive. Lorenzo died after about 70 hours of suffering and agony on May 10, 1967. During the checks following the crash the car was found in fifth gear in a section that is usually travelled in third. Even today, almost fifty years later, the main cause of the accident is attributed to physical fatigue that could have led him to make a mistake. Furthermore, the security measures of the time certainly did not help.

The metal bars used for mooring boats, which paradoxically prevented the car from falling into the sea but whose absence would perhaps have caused less serious consequences, the bales of straw present at the edges of the circuit that were the first to fuel the flames, as well as the lack of fireproof suits and of a sufficient number of fire extinguishers for the commissioners, amplified a dangerous situation that was already out of control. Elements that, following the death of Bandini, sparked fierce controversy on the issue of racing safety. In the meantime, that May 10, 1967, a great champion and a man everyone loved had gone. A young man like many who was seen as the classic example of someone who, thanks to his tenacity, had managed to reach the Olympus of motorsport. Bandini perfectly embodied the stereotype of the good guy who, after years of sacrifice and a lot of sweat, had managed to make a dream come true. His life and career broke apart when he was just over thirty years old and no one will ever know if he, the son of a humble mechanic from Emilia, would have really won the world title in 1967. One thing is certain, Lorenzo Bandini had managed to break through the hearts of millions of Italians as few others would have been able to do in the following decades and this is probably still the reason that keeps the memory of his exploits alive.

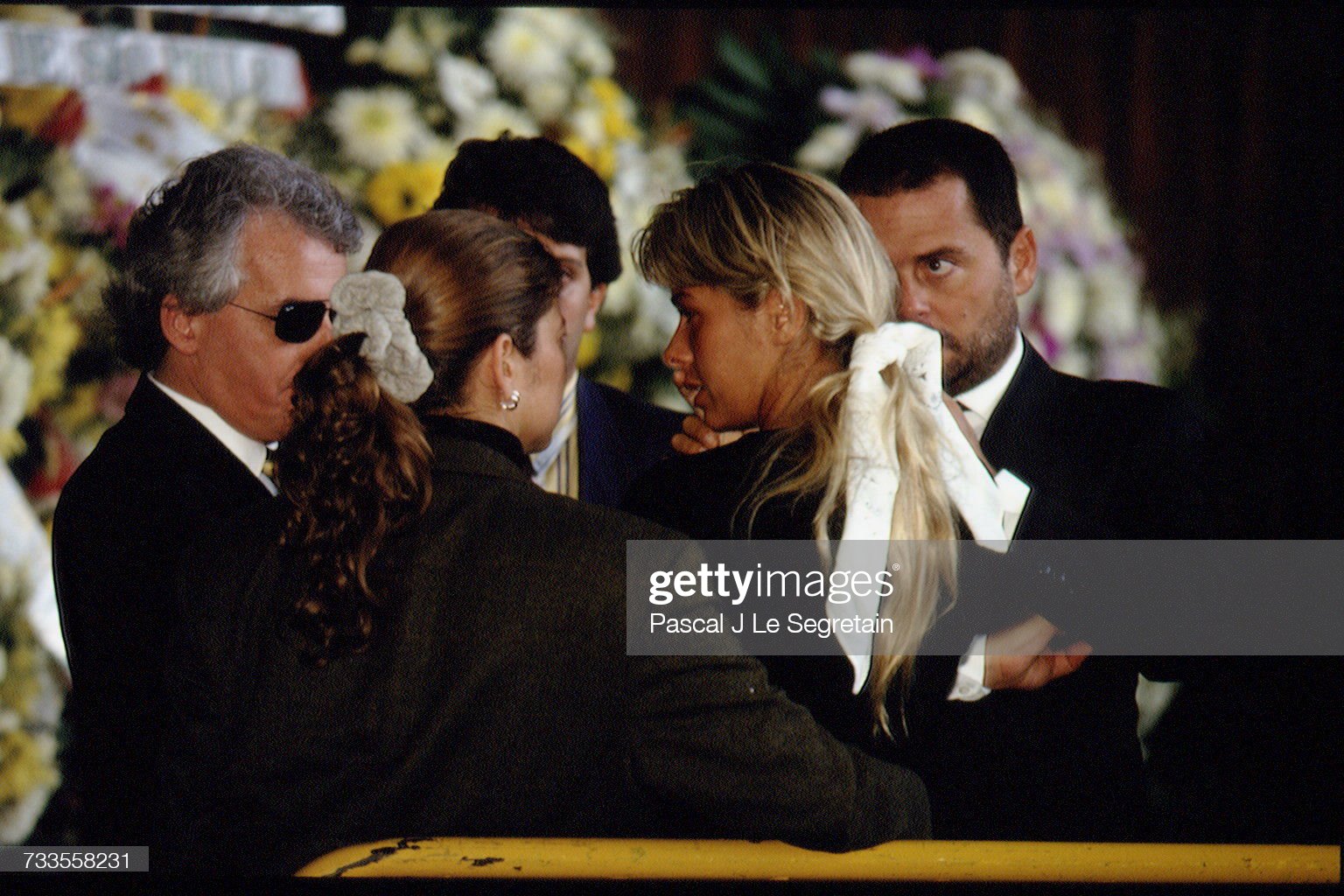

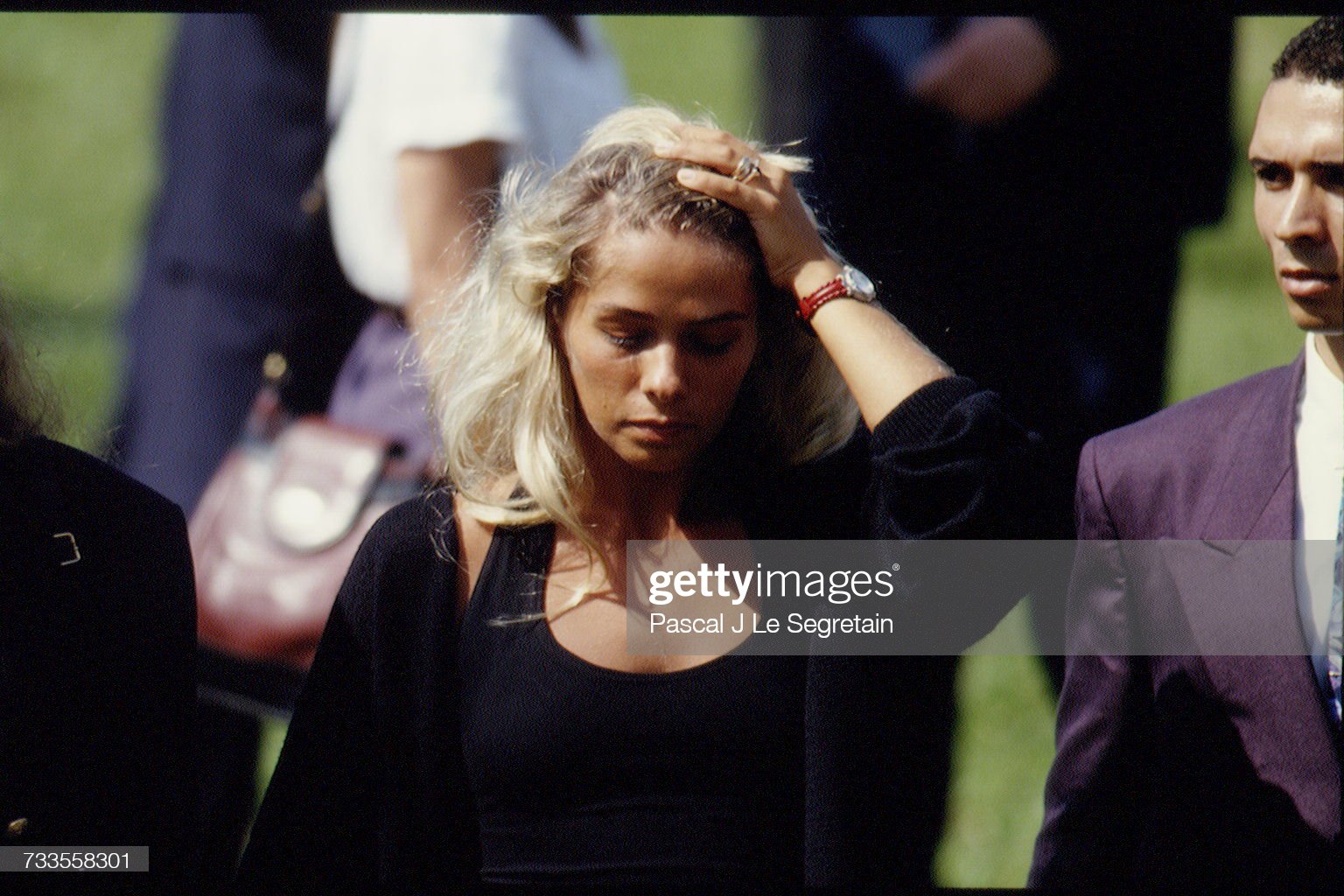

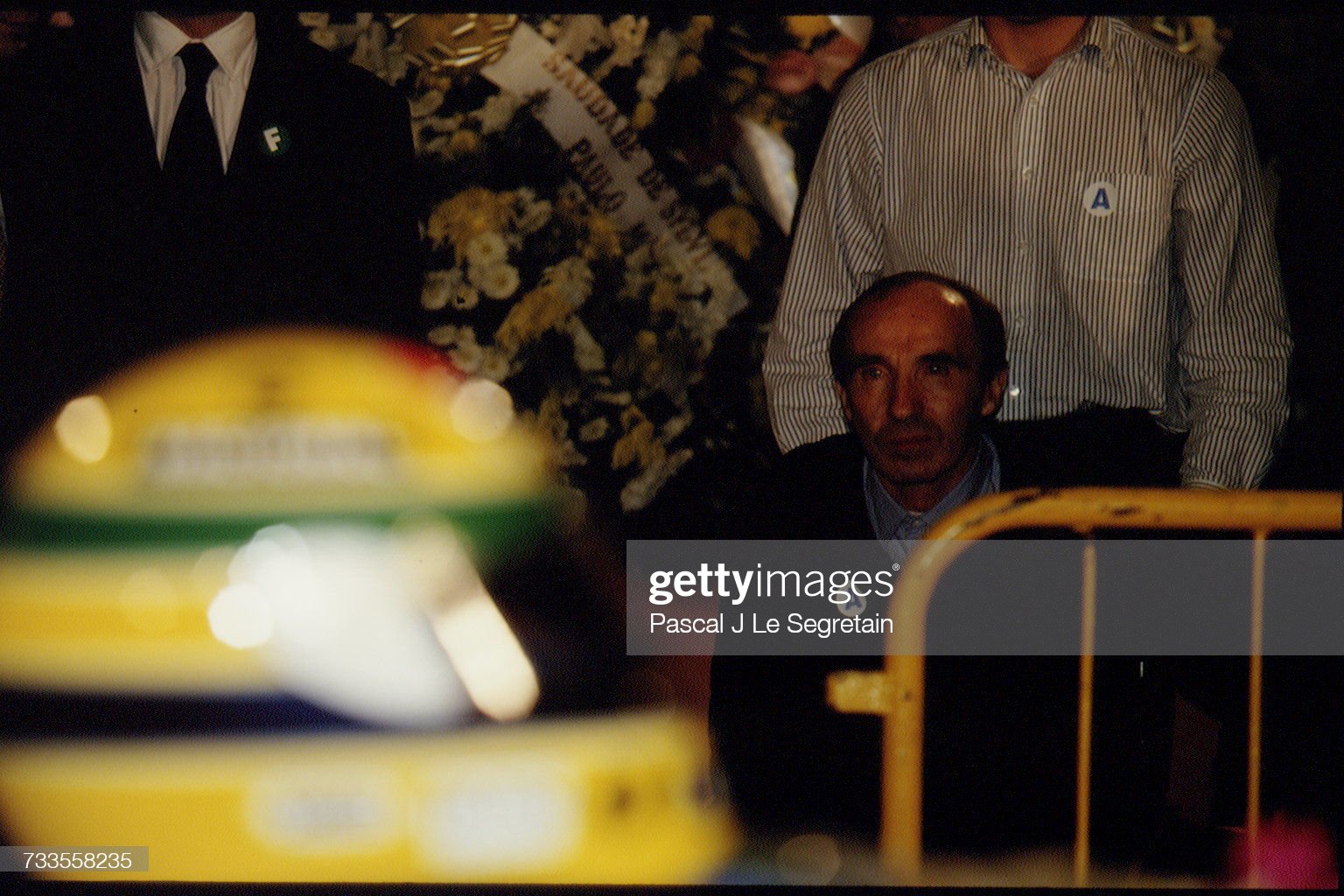

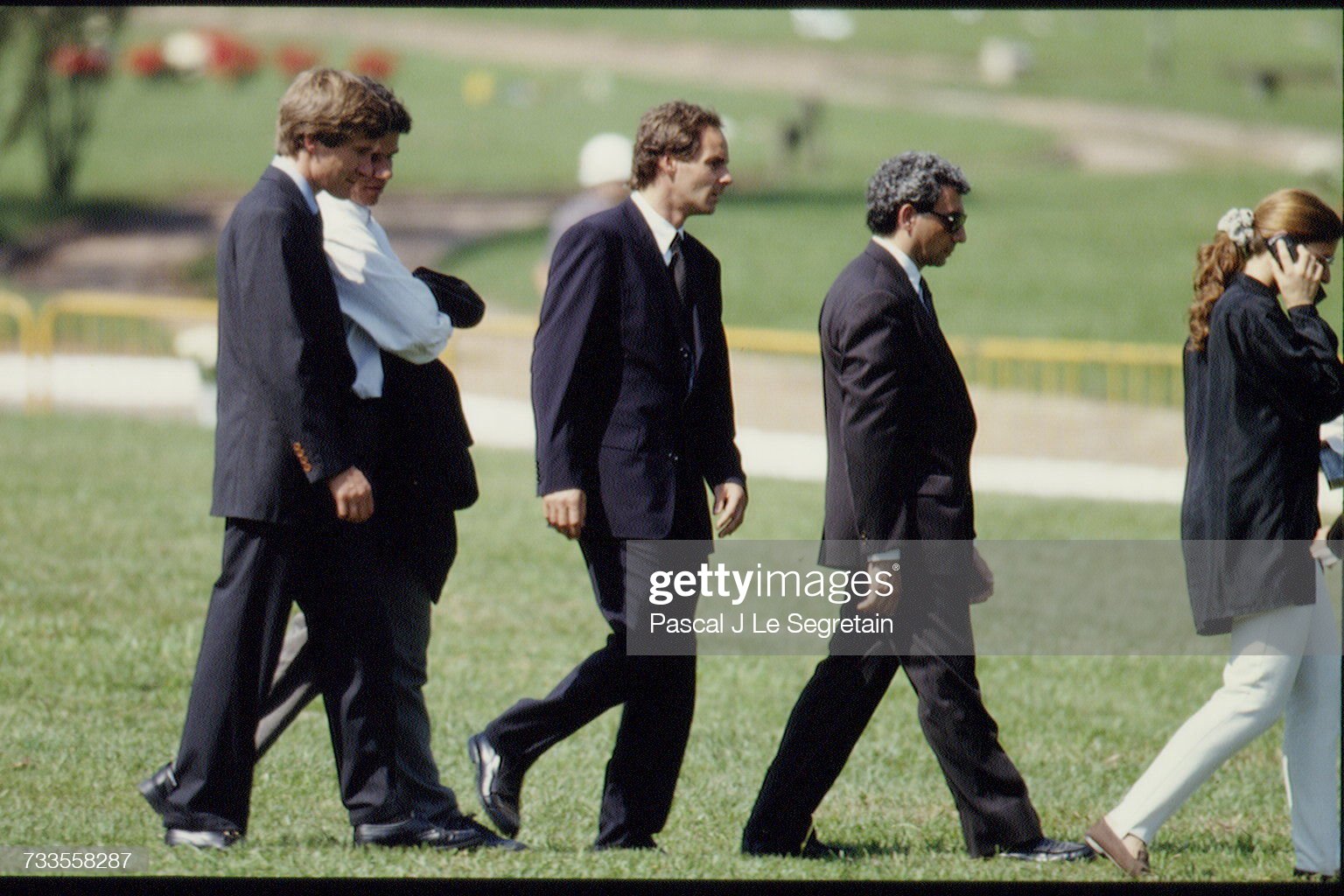

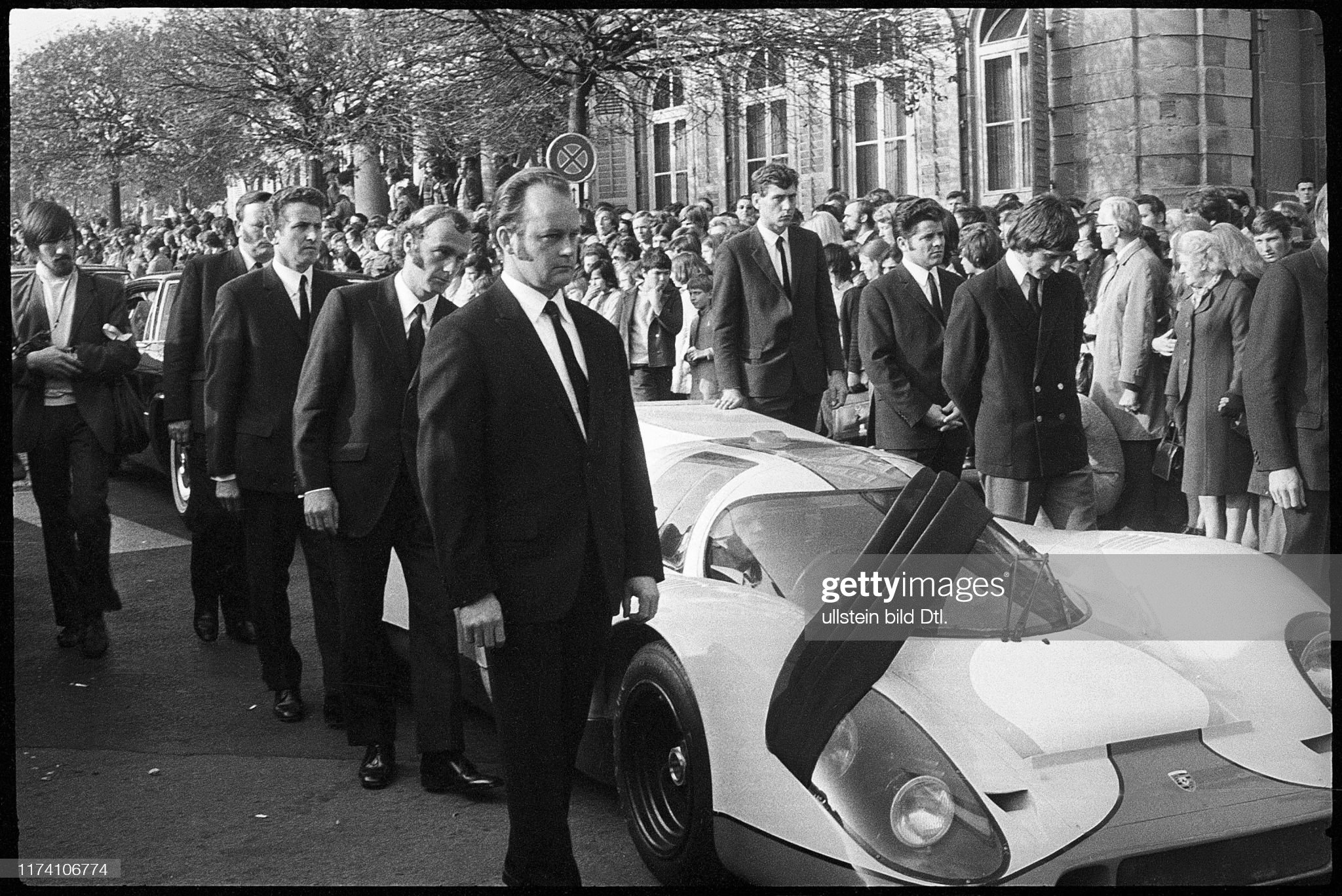

Lorenzo Bandini’s funeral.

On the day of his funeral in Milan his wife Margherita, daughter of the first man who believed in him when he was still a complete stranger, was accompanied by thousands of people who came to the Lombard capital to pay their respects to the most beloved driver.

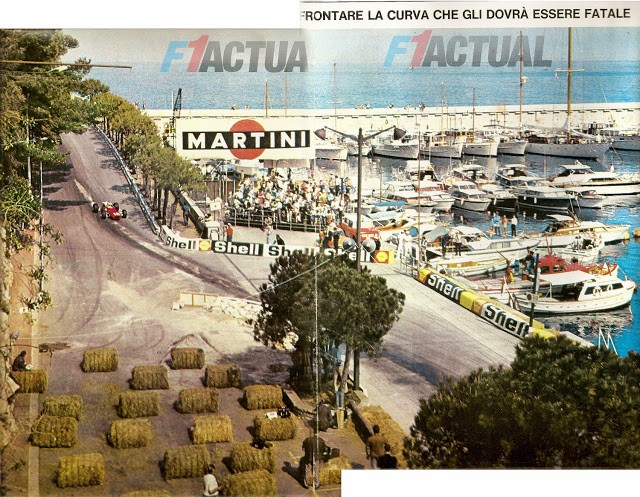

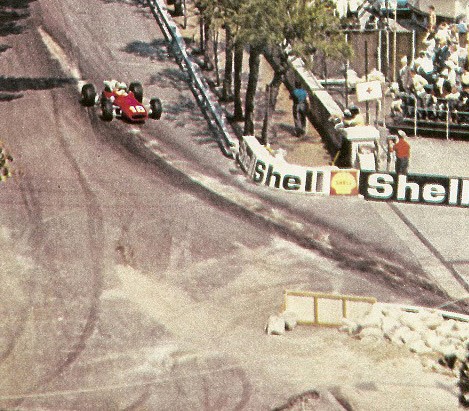

In my opinion we are right in front of the offending pole. Behind, we see a bollard and some very inclined handrails. It should be noted that the sea is much further down, I would say 3 meters below. Further ahead you can see the strip of asphalt (already present) and the railing (you can see the bollards). Warning: it is small, but it is clear that the offending point is the same. Here, in 1965, Paul Hawkins went overboard, passing straight between the pole and the bollard. Bandini will be much less fortunate. Image taken during the film Grand Prix, with a re-presentation of the dynamics of the Hawkins accident. It gives us the proportions between the road and the sea. The "handrails" can be seen hanging.

Even Borsari's statements were not always clear: ".... from the pits we exchanged conventional signs, then Lorenzo began to stop responding but, the lap before the accident (or the lap before that), Lorenzo widen his arms as to say ‘more than this I can’t do ...’"

The newspaper l'Unità of 08 May 1967.

One last contribution, thanks to Google Maps 1967: two mosaics of frames from films reconstructing the scene of the accident that has just occurred.

In this you can see the whole area starting from the chicane.

In the enlargement it is easy to see the two offending points, the pole and the railing. In particular, you can see very well the famous staircase to the sea and elements of the protective railing torn up.

That Bandini was tired is plausible but everyone was tired. Hulme came out of the car destroyed and, during the GP, he had also touched the straw bales almost in the same place where Lorenzo hit them.

Among the images of "L'Europeo" of 18 May 1967, there is an exceptional panoramic photo. The title, although cut, refers to the moment before the accident. Let’s see the image gradually enlarged.

The position of the car is out of the ideal line, too far inside. And, above all, the driver's head is shifted to the left and looks to the right, towards us, instead of to the incoming curve, just like in the grainy photo, even if a few meters before. It is not hazardous to assume that the two photos were really taken almost simultaneously and that they refer to the crucial moment. And, perhaps, they contain clues to trace the causes. It is obvious that something unexpected is happening and the driver reacts in an unusual way. But what could have caused such a "rash" movement? What is it that can turn the driver's gaze away from the corner he is about to face and even force him to an unusual position in the car, all shifted to the left?

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari 312, Grand Prix of Monaco, 07 May 1967. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Lorenzo Bandini at Monaco in 1967.

“A car was burning near the harbor section and it was Lorenzo's. But I couldn't know more. After a few laps I punctured a tire passing over his debris and was forced to a pit stop. I have before my eyes the shocked faces of Forghieri and the mechanics, as white as sheets of paper. Something terrifying was happening to my friend Lorenzo and I couldn't do anything about it. I've been troubled for a long, long time. So much so that in Spa, when the accident happened to Parkes, my other teammate, the unthinkable happened. I thought it was over for him too. So it was that, from the pits, to reassure me they displayed the sign with the words “Parkes OK”. Mike had a broken leg, yet that signal meant "Parkes will survive." At that time it was a great reason to try to break the lap record right away. I lapped three seconds faster. The psychological support therapy had worked ... I still have a photo of the winter of 1966, with me, Bandini, Scarfiotti and Parkes. United, smiling, happy. A few months and I was the only one who could hope for a career as a driver.” Chris Amon

"I'm writing a book and I was thinking of devoting a chapter to dead friends. But, after a couple of minutes, I realized how long the list was." Chris Amon

Spada Amphitheater of Brisighella, July 2012. The driver Bruno Senna with the mayor of Brisighella Davide Missiroli and Gabriella Bandini, the sister of Lorenzo. Photo by S. Cantoni.

Lorenzo Bandini said, "if you have to go, if it's written that your moment is that day, you will die whether you race or not. In case of an accident, don't make any drama." But that day it was impossible not to despair, because that day went away, as well as a great man, the hope of an entire nation.

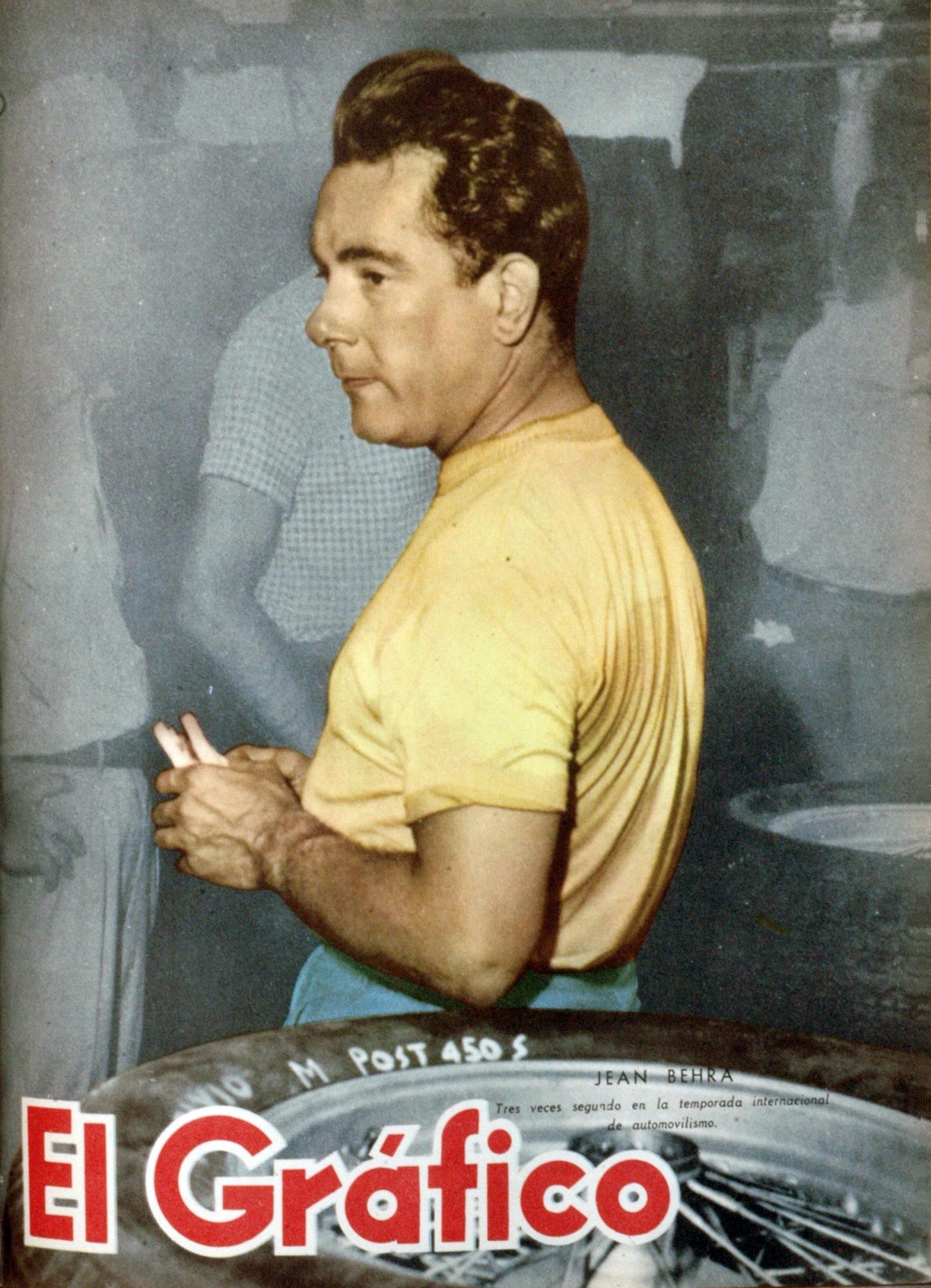

Jean Behra

Jean Behra: 'he never knew the meaning of fear'. Fifty years after his death, Jean Behra is still remembered by his contemporaries as one of Grand Prix racing’s bravest souls. By Nigel Roebuck.

Behra at the wheel of his Maserati 250F in the 1958 Argentinian Grand Prix. Grand Prix Photo.

Back in June 1980 I interviewed Patrick Depailler at Brands Hatch. He was a lovely fellow, a man out of his time, I always felt, very much a throwback to motor racing’s heroic age.

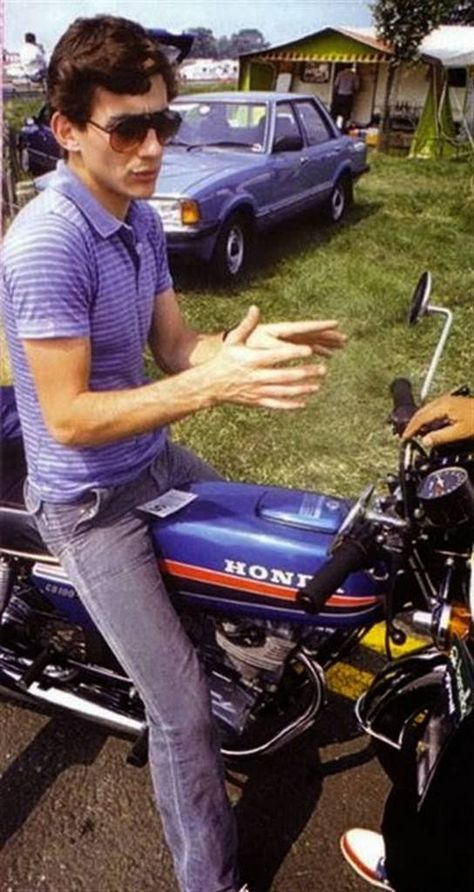

At the time tennis was fashionable in Formula 1 circles and often at airports – most of them flew ‘commercial’ in those days – you’d come across a driver with a briefcase in one hand, a racquet in the other. Depailler would snort at that: he loved skiing and sailing and overpowered motorcycles. His heroes were Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx, five-time winners of ‘Le Tour’.

And there had been another. When I mentioned that my childhood life had revolved around Jean Behra, Patrick’s face lit up: “no, really? I was the same …”

A few weeks later I spent a morning at the Williams factory. It was August 1, the date of Behra’s death and I was thinking about him as I drove to Didcot. On the way back I heard of Depailler’s fatal accident during testing at Hockenheim.

Now we are far on from there and Behra has been gone 50 years. I happened to be alone in the house that Saturday afternoon, watching Grandstand, when the newsflash came in: ‘the French racing driver Jean Behra has been killed in an accident in Berlin …’

I will never be able to explain why ‘Jeannot’ so dominated my young life and perhaps that’s as it should be. One shouldn’t, after all, seek a rational explanation for everything; an element of mystery is surely essential in a hero.

Behra (red shirt) in 1957. Grand Prix Photo.

It didn’t matter that there were greater drivers, that he was never World Champion or whatever. What appealed to me primarily about Behra was his utter fearlessness – that and his dedication. Raymond Mays once related to me an anecdote revealing of Jean’s love affair with his job.

“He was a magnificent driver and a charming man, but terribly temperamental in a French sort of way. Sometimes he’d get a bit demoralised, but it never lasted long and I asked him how he kept his spirits up. “When things were bad, he said, he would get his passport out: ‘I look at all the stamps, the places racing has taken me and then at the first page. Name: Jean Behra. Profession: Pilote. And I remember how lucky I am to have this life.’ I found that rather moving – and somewhat different from most racing drivers I’ve known.”

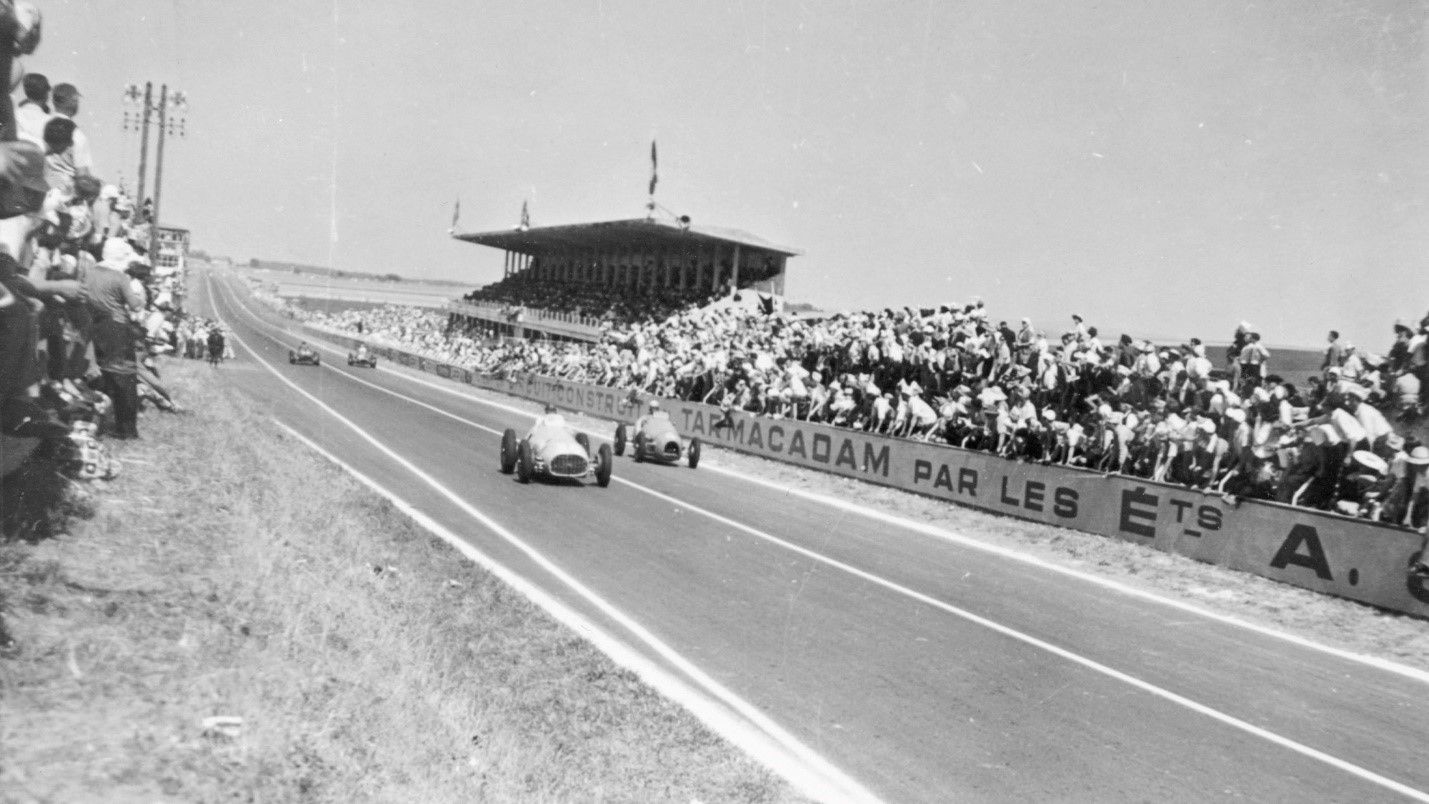

1952 Grand Prix de la Marne at Reims, Jean Behra's Gordini defeats Ferrari. August 1952 Issue.

Behra, born in Nice in 1921, was one of life’s natural competitors, racing bicycles, then motorcycles, in his teens until the war intervened. Afterwards he carried on as before, champion of France for several years on his red Moto Guzzi. A move to cars, though, was increasingly in his thoughts: by the end of 1951 he had turned his back on bikes and headed to Paris, to 69 Boulevard Victor, where resided the team of Amedée Gordini, whose cars were sometimes fast, always fragile. A contract was signed.

The following June Behra broke into the national consciousness and he would remain an idol in France for the rest of his life. At Reims, totally against expectations, he defeated the Ferrari team in the Grand Prix de la Marne, fighting off even Alberto Ascari.

“It was impossible,” said Jabby Crombac, “to overstate the importance of that victory in France. It was only two weeks after Le Mans, where [Pierre] Levegh tried to drive the whole race on his own and failed at the very end – leaving victory to the Germans! This was not so long after the war, you know …

“Wimille and Sommer were gone, so when Jean – who was new in car racing – won at Reims, he was instantly a national hero. Beating the Italians was almost as good!”

Louis Rosier leads Jean Behra, who would go on to win, at Reims in 1952. Heritage Images / Getty Images

Crombac adored Behra: “he was like Jean Alesi – lovely guy, looked the part, tremendous guts, too emotional, drove with his heart …” Shortly before Jean’s death, indeed, he asked Jabby to become his manager: “I didn’t go to Avus – we were to have dinner in Paris the week after to discuss it, but he never came back …”

Jean Behra in 1953.

Jean Behra (left) with Fritz Huschke von Hanstein, Richard von Frankenberg and Edgar Barth.

Behra stayed with Gordini for three years, but the cars rarely lasted and his frustration mounted. There were, however, occasional successes, as in the 1954 Pau Grand Prix, where he defeated Maurice Trintignant’s factory Ferrari.

On Sportsview, a BBC programme of the time, a clip of the race was shown and I was captivated by the battle between the dapper, fastidious Trintignant and the stocky, charismatic Behra. Right there I was hooked and a few months later, in the Oulton Park paddock, gazed endlessly at Jean’s light-blue Gordini. It had qualified second for the Gold Cup, but disappeared after a couple of laps.

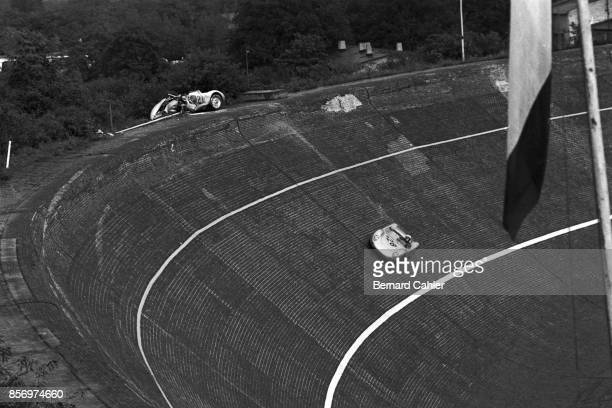

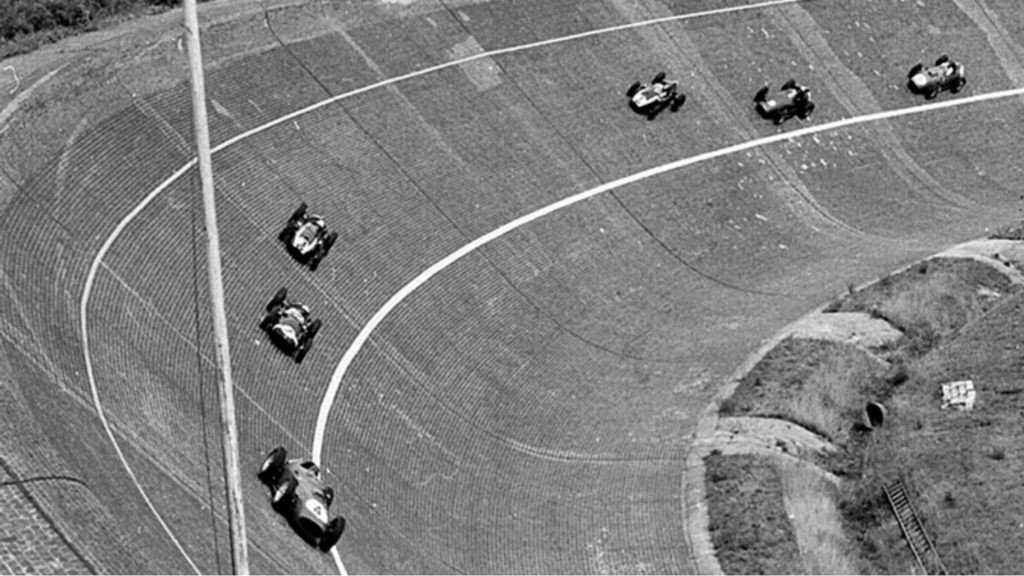

Soon after there was a non-championship race at Avus, put on as a showcase for Mercedes. Karl Kling was allowed to win at home and the only happening of note was that Behra’s Gordini clung on to the three streamlined W196s, achieving speeds unthinkable without a tow.

Needless to say, the Gordini expired after 15 laps, but Denis Jenkinson was ever after inclined to cite Behra’s drive as the quintessential example of what he called ‘tiger’, this an indomitable refusal to give in.

Behra’s tiny Gordini hangs on to Mercedes streamliner trio at Avus in 1954. Daimler-Benz.

Jean Behra, Andre Simon, Roberto Mieres, Luigi Musso, Maserati 250F, Grand Prix of Great Britain, Aintree Motor Racing Circuit, 16 July 1955. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Jean Behra, Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 11 September 1955. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

For 1955 Behra moved to Maserati, but how different his career might have been had he stayed his hand on the contract a little longer, for Alfred Neubauer, needing support for Fangio, was looking around: “I thought of Behra – but he had already signed for the opposition …” Eventually, of course, he signed one Stirling Moss.

As it was, Jean found at Maserati his spiritual home and his three years there were to be the happiest of his racing life. Through another Mercedes summer the 250F was unable to trouble Fangio and Moss, but Behra was invariably ‘best of the rest’ and won non-championship Grands Prix at Pau and Bordeaux, as well as several sports car races.

At the end of the season, though, he crashed in the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod, suffering a broken arm and torn tendons in his right hand. As well as that, his right ear was severed and this was to be his most celebrated injury. Thereafter he would wear a plastic ear, which he was wont to remove when the occasion demanded, as in a crowded restaurant. “There’s always a table available then,” he would grin. “Sometimes several …”

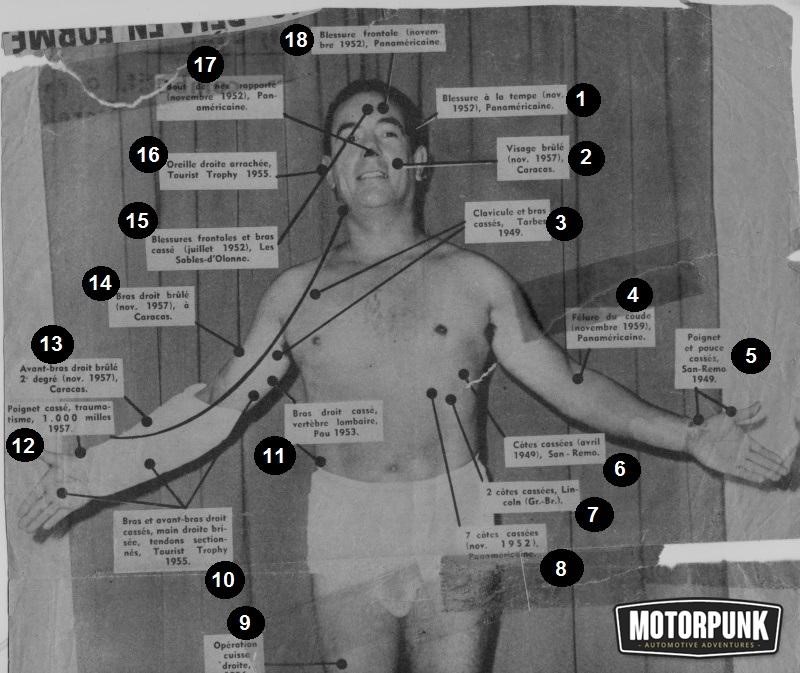

In the course of his career Behra did indeed have an enormous number of accidents and this was long before the advent of proper helmets and fireproof overalls, let alone seat belts and rollover bars and gravel traps.

In 1949 he came off his Guzzi at Tarbes (broken arm and collarbone) and the following year at San Remo (broken kneecap); in ’52, while leading the Carrera Panamericana, his Gordini went off the road and into a ravine (seven broken ribs) and then he crashed at Sables d’Olonne (broken arm); in ’53 there was an accident at Pau (broken arm, displaced vertebra); in ’55 came the Dundrod accident and in ’57 shunts during Mille Miglia testing (broken wrist) and at Caracas (serious burns to arms and face). The list went on.

‘Jean Behra’, wrote DSJ in September 1959, ‘had more guts than the majority of today’s drivers put together. He never knew the meaning of fear and in consequence tended to drive over the limit more often than not. The way in which he would recover from injury and return straight away to racing was remarkable. A lot of people, drivers included, openly disliked Behra for no other reason than that they were secretly envious of such a tough little man, who would have the most almighty accident, climb out of the wreckage and come back for more.’

In the ’50s Jenks was frequently in Modena, where Behra was an almost permanent resident at the Albergo Reale. “What I liked most about Jean,” he said, “was his pure love of racing cars. He was a good mechanic, but he never worked on cars for the fun of it: what mattered was making them faster. They loved him at Maserati, because he was happy to ‘live above the shop’. There was no bullshit about Jean. He was a racer’s racer.”

Behra accepted Moss as number one at Maserati. Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

At the end of 1955 Mercedes withdrew from racing and Fangio signed for Ferrari, while Moss joined Behra at Maserati. Plainly Stirling was the best driver in the team, the accepted number one, but Jean welcomed him and had an untypically consistent season, finishing fourth in the World Championship and again winning a number of sports car races, including the Nürburgring 1000 Kms.

“Behra was one of the greatest fighters I ever came across,” says Moss. “If you passed Castellotti or Musso or Collins or Hawthorn, that was the end of it, but with Jean there was no way you could put him out of your mind – you had to keep your eye on your mirrors, boy!

“He was an incredibly tough competitor, you know and that made him unpopular with some of the drivers, but I thought it was his greatest strength and I very much identified with it. He was always fair, too – I mean, he wasn’t about to say ‘after you’, but he’d never do a Farina on you! I’d always feel quite happy going into a corner alongside him.

“Fangio, I believe, said Behra was ‘too brave’, but I’m not sure I’d say too brave – not in the way that Stuart Lewis-Evans was, for example. I always liked Jean: he was there to get on with what he was doing and he did it bloody well …”

Jean Behra, Maserati 250F, Grand Prix of Monaco, Circuit de Monaco, 13 May 1956. Jean Behra drove a fine race and finished on the podium in third position. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Behra shared victory with Fangio at Sebring in 1957. Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Cockpit of the Maserati 450S which will be driven by Jean Behra and Andre Simon in the 24 Hours of Le Mans race, Le Mans, June 1957. Behra challenged for the lead, but the transmission eventually broke in the third hour. Photo by Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

Juan Manuel Fangio and Jean Behra, June 21, 1957, Le Mans. Photo by Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Jean Behra, Maserati 250F, Grand Prix of France, Rouen-Les-Essarts, 07 July 1957. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

For 1957 Moss left Maserati for Vanwall, but any hopes Behra may have had of regaining his number one status were dashed when it was announced that Fangio was coming aboard for what would be his last season.

Jean revered Juan Manuel and in point of fact had the finest year of his career. The pair shared the winning Maserati 450S at Sebring and, in a similar car, Behra won the Swedish GP, partnering Moss. Clutch failure kept him from winning the British GP, but there were F1 victories at Pau, Modena and Morocco and a couple more – in a BRM, no less – at Caen and Silverstone.

Financial problems drove Maserati out at the end of 1957, whereupon Jean signed for BRM. But the following season was unsatisfactory, for the car, while sometimes quick, was lamentably unreliable and frequent brake failures – one of which pitched him into the Goodwood chicane wall – did nothing for his confidence.

Jean Behra, Giorgio Scarlatti, Tony Brooks, Maserati 300S, Grand Prix of Cuba, La Havana, 23 February 1958. Photo by Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

Jean Behra at Rennes in 1958. Photo by Ullstein Bild via Getty Images.

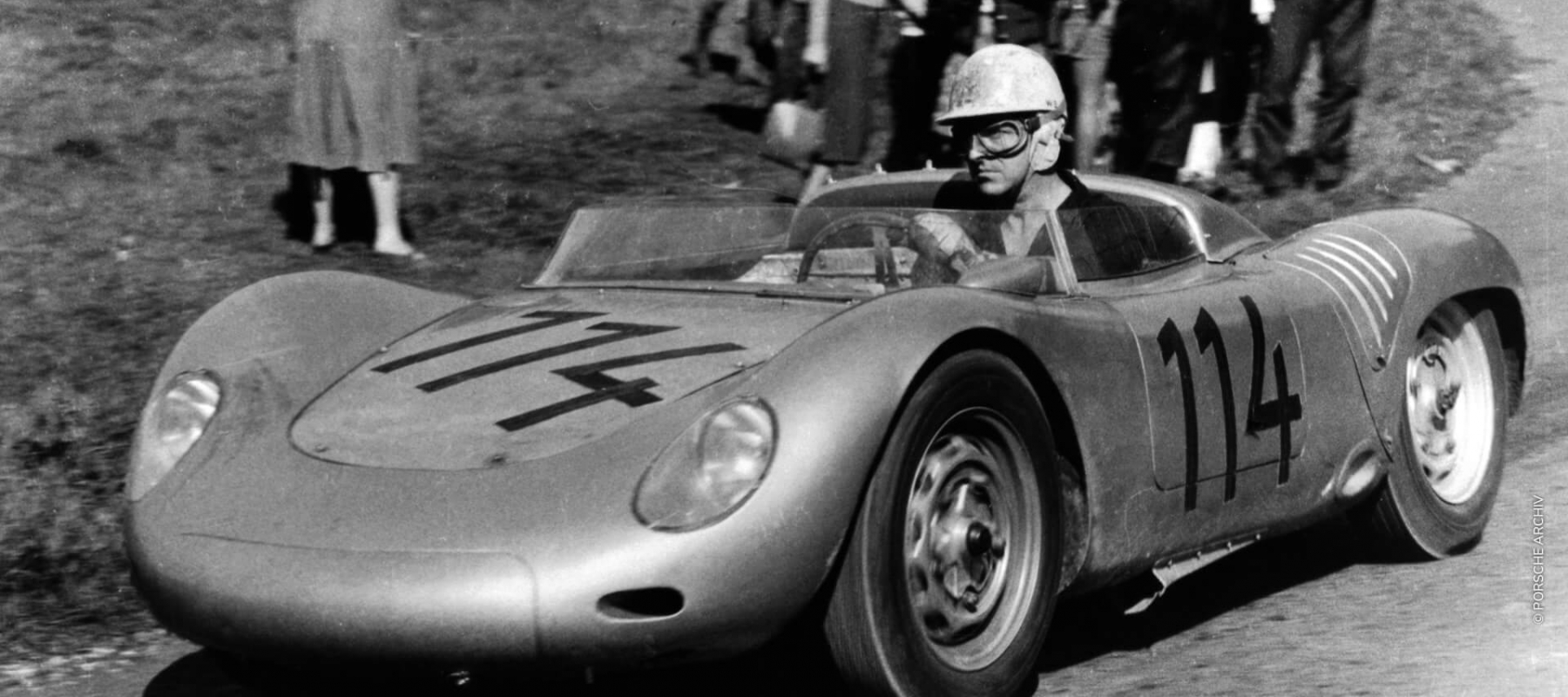

What kept Behra going in 1958 was a new relationship with Porsche, for whom he was consistently brilliant in the little RSK sports cars, finishing second at the Targa Florio and third at Le Mans, as well as winning events as disparate as the Mont Ventoux hillclimb and the Berlin Grand Prix – at Avus.

By general consent Avus was a singularly stupid race track, comprising two flat-out autobahn blasts, with a hairpin at one end and the notorious steeply-banked curve at the other.

To Behra, though, a race was a race. When the USAC brigade came over in 1957 for the Trophy of Two Worlds at Monza, the Europeans had little enthusiasm for a banked track which Tony Bettenhausen’s Novi would lap at 177mph! Maserati, though, built up a special car and Jean was mortified to find it too slow to compete with the Americans. I could always readily picture him in a roadster at Indianapolis.

Behra, at the Nürbirgring in 1958, found little success with BRM. Grand Prix Photo.

Fundamentally, Behra had enjoyed the BRM team, if not sometimes its cars and he would probably have stayed on in 1959 – had not there come a call from Maranello.

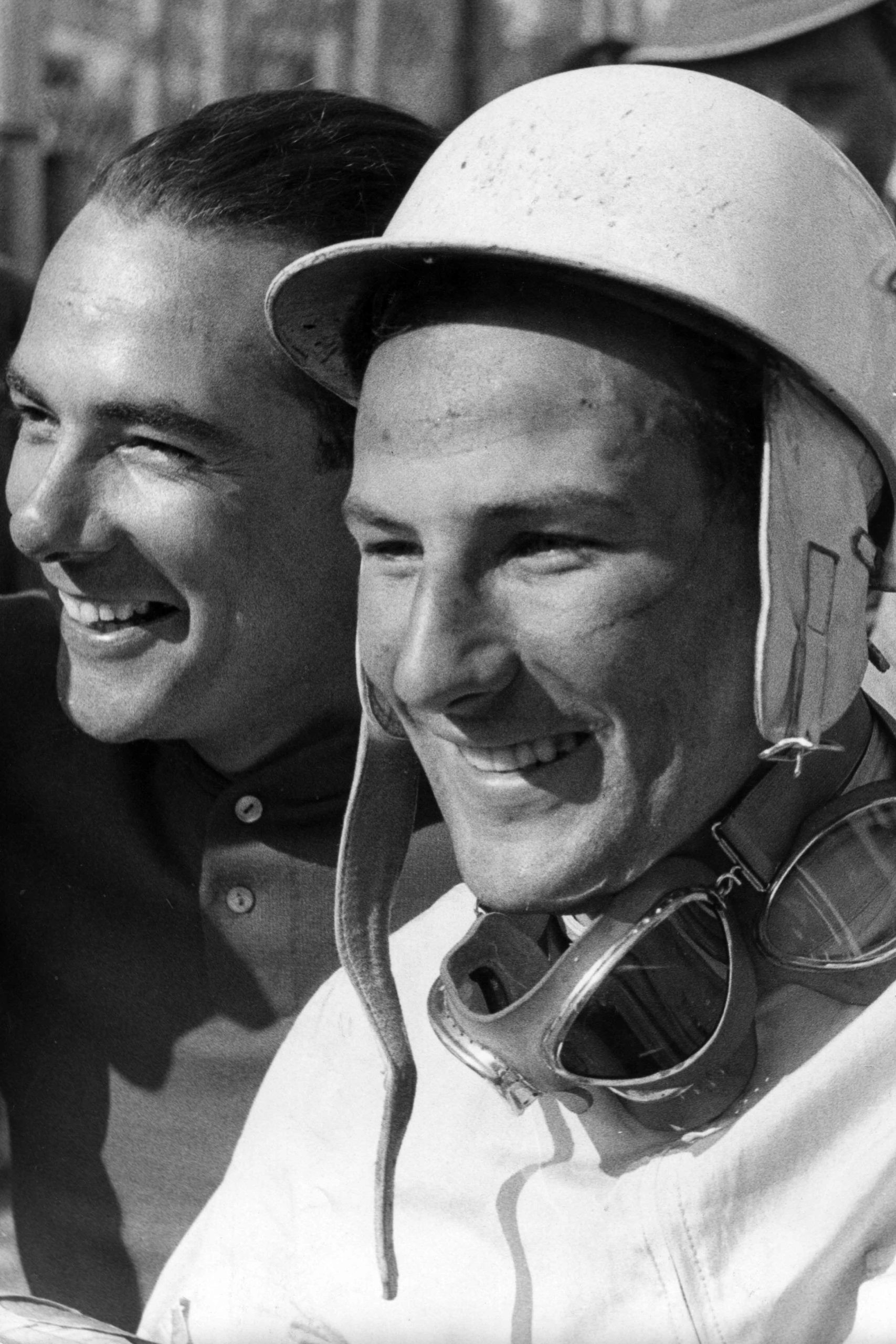

This was like coming home – Modena, the Reale, ceaseless testing – and the new association began well: in the Dino 246 Jean won the Aintree 200 from team-mate Tony Brooks.

“I rated Behra very highly as a driver,” says Brooks. “In a decent car he could give anyone a run for their money. Mind you, although we were team-mates I didn’t know Jean that well – he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak French. ‘Ciao’ and ‘bonjour’ was about as far as we got!”

“We shared a Testa Rossa a couple of times. At the Targa he started the race and rather modified our car – by rolling it down a mountainside! He crawled out from underneath it and got some Sicilian peasants to help him right it and push it back to the road. When he brought it into the pits I thought, ‘well, that’s ready for the knacker’s yard’, but Jean had different ideas and so did [Romolo] Tavoni, the team manager. I said something along the lines of ‘you’ve got to be joking’, but they weren’t! I went out, but the steering was all over the place and eventually the car went straight on – fortunately at a slow corner …”

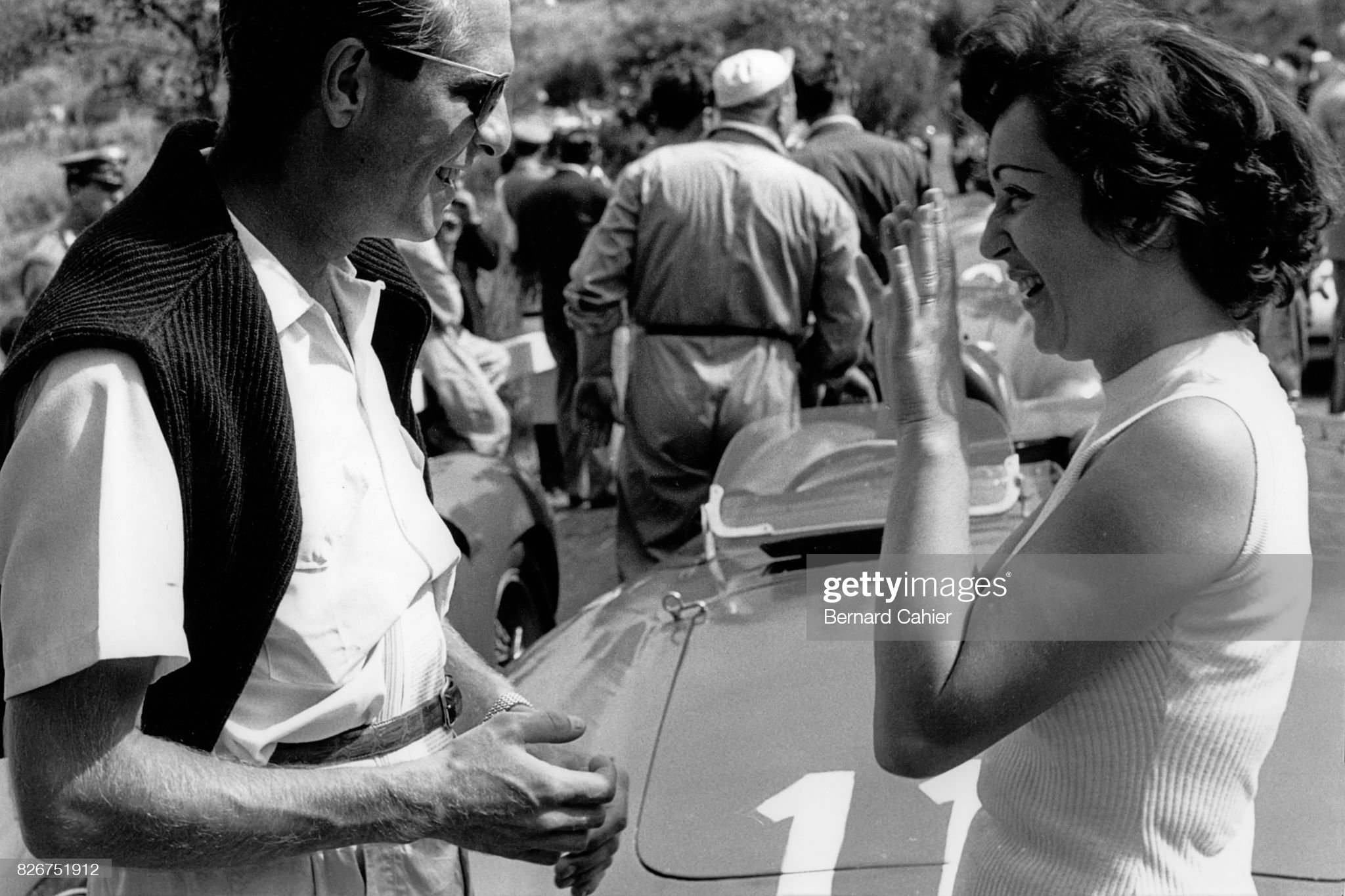

The start: (left to right) Stirling Moss (Cooper T45), Jean Behra (Ferrari 256F1) and Jack Brabham (Cooper T51) form the front row, Monaco Grand Prix, Monte Carlo, May 09, 1959. Photo by Edward Eves / Klemantaski Collection / Getty Images.

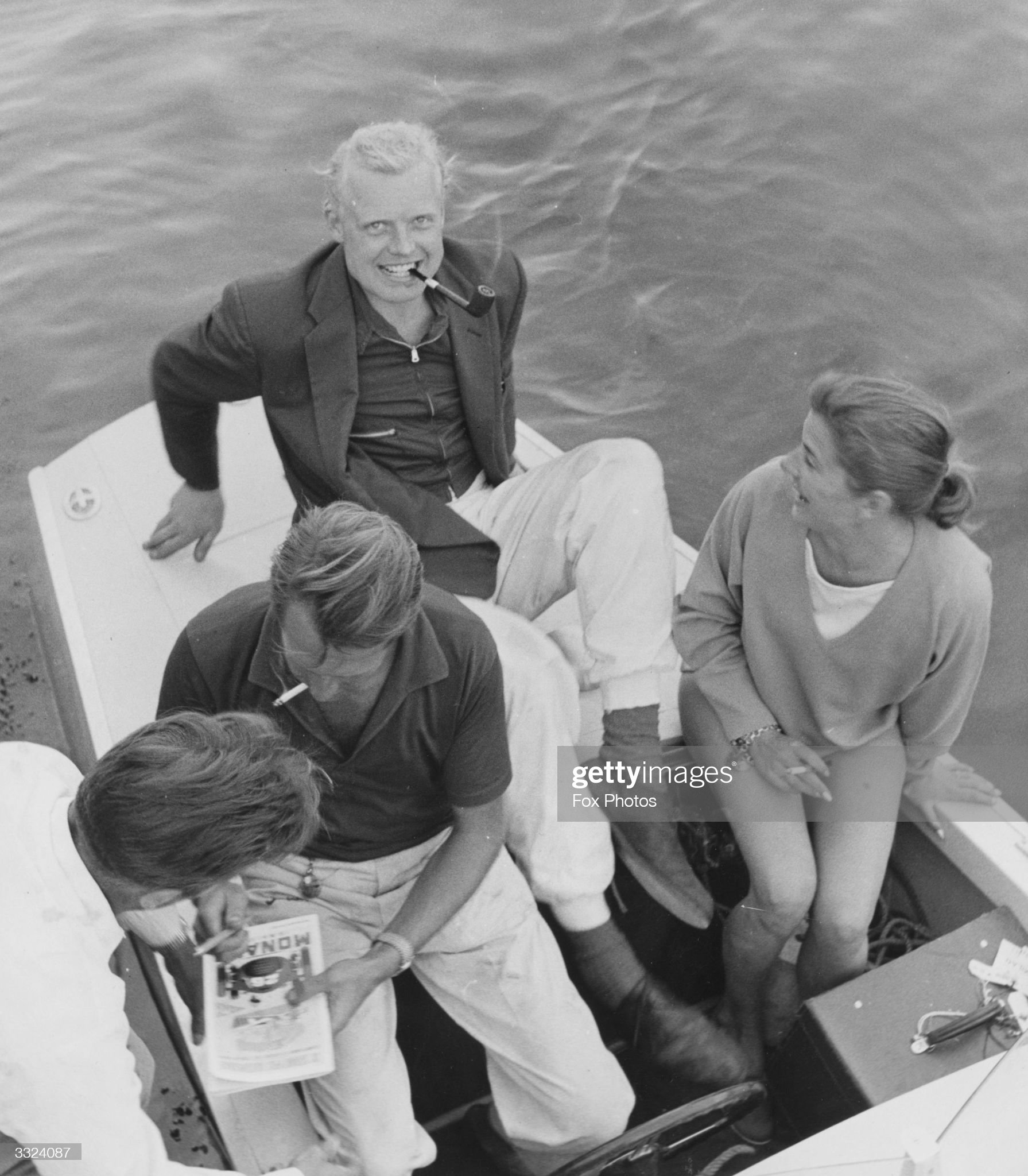

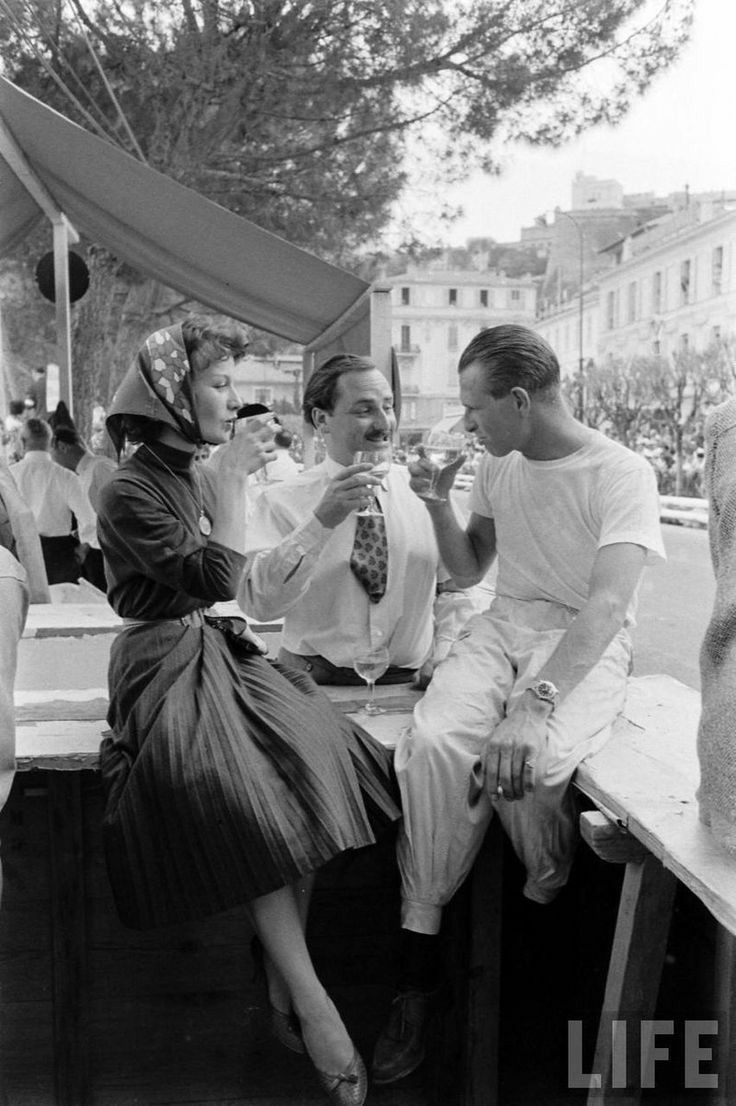

Juan Manuel Fangio, Jean Behra and Maria Teresa de Filippis at the 1959 Monaco Grand Prix. Photo by Maser.

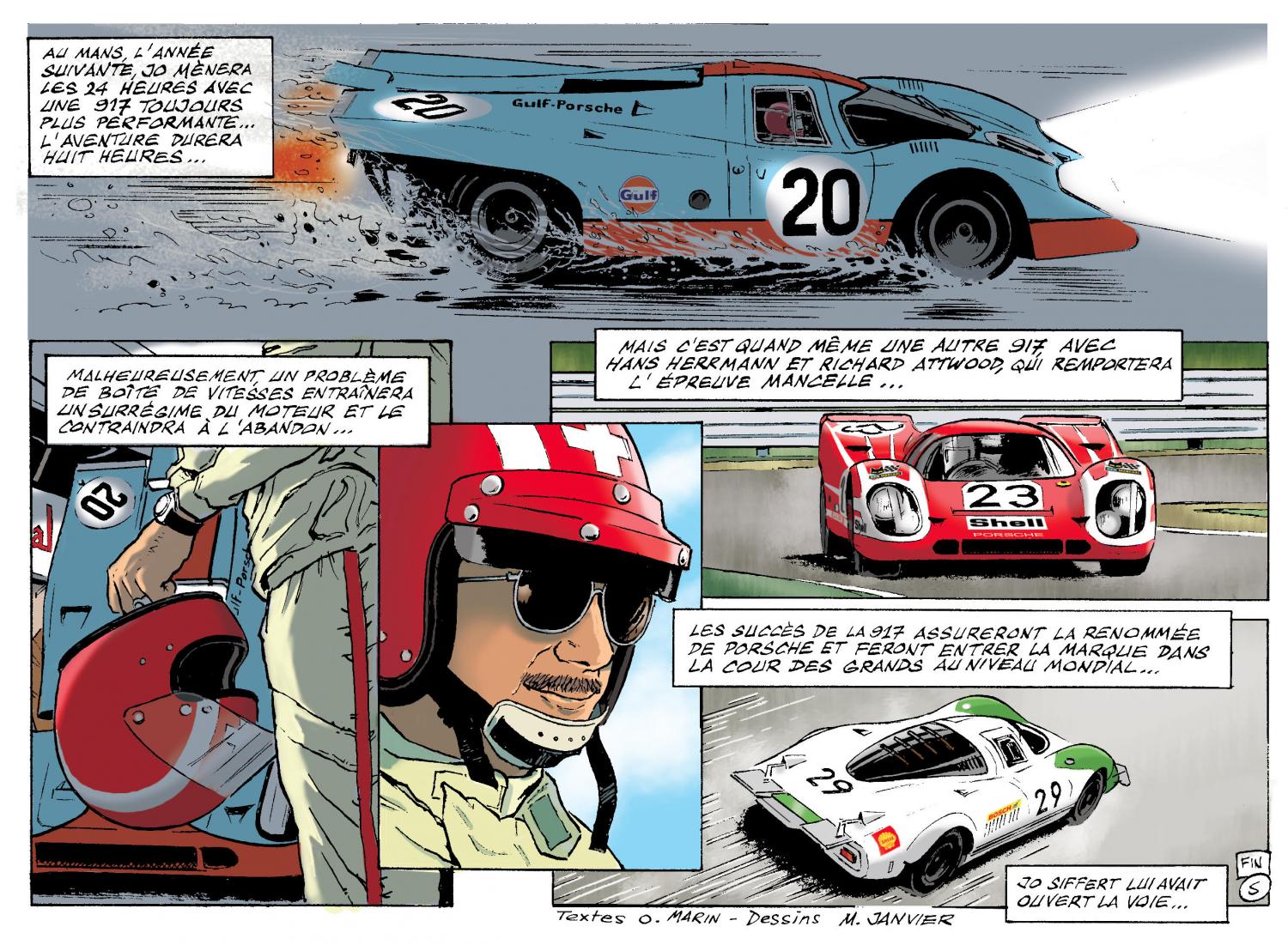

At Le Mans Behra was paired with Ferrari’s newest recruit, a youthful, crew-cut American named Dan Gurney, but although fastest in practice he was almost the last man away, his car reluctant to fire up. After an hour or so, though, the TR59 was leading; as a piece of sheer driving brilliance Behra’s performance that day stands comparison with any ever seen at the Sarthe.