Sergey Bubka has climbed onto the roof of the world. He was the best in his sport, a legend. Sergey the frosty who allowed a few formal words for every record. He always won everything, he always set records: thirty in ten years, three in a week. And almost always making his way with arrogance: three jumps in all and go, on top of the world. Without much preparation or warm-up, without wasting time with low measures, with the aperitif. As if the others didn't exist, they didn't count. Never a false return, never a failure. They measured the altitude he could jump in many ways: two and a half times the height of the goal of the football pitch, almost double that of a typical English bus, only 4.39 meters high. There was something for all tastes: in the end, discouraged by the fact that they no longer found comparisons, they had also involved the giraffes. Bubka was now a myth, indeed a Martian.

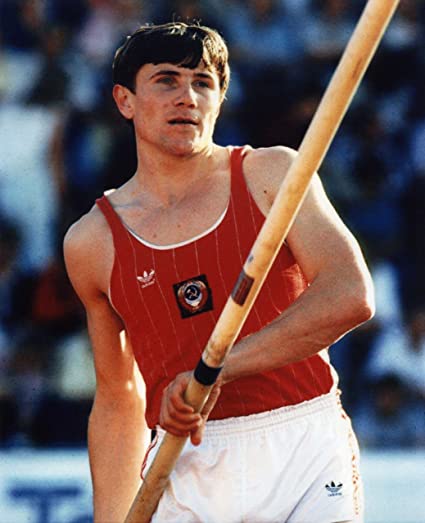

He streaked the sky. Twenty years ago in Paris. He opened it wide. At six meters. There were no more barriers, you could go up, over the horizon. Sergei was 22 years old, long socks, red shirt of the USSR, but he came from Ukraine. He was alone in the race, there weren’t his great opponents, Vigneron and Quinon, he shouldn't have been there either. Vitali Petrov, his coach, recalls: «we had arrived to participate in the Nice Grand Prix three days later. We had taken the plane from Moscow in the morning. Arrived in Paris at the airport we find an organizer: 'Sergei, there is a race today at three o'clock, do you want to do it? I first think it's better not, but I change my mind. Sergei passes 5.70, 5.85, then asks for the bar at six meters. Third attempt, not a good run-up, but he makes it out. He just needed 5.95 for a new world record, but him and me wanted more. To be the first to reach six meters. The birth of his first child helped him, gave him an extra boost that day. We didn't even celebrate, we had other races to prepare. And we didn't have any money either, it came in the 90s." Six meters of solitude. 17 centimeters scaled in a year. A $ 150 reward. "It's the refund they gave him in Moscow." The USSR accepted that Bubka, who grew up in the middle of Soviet empire, jumped with fiberglass and carbon rods that came from the other continent. From Carson, Nevada, Usa. A 5.20-long rod, Bubka held it towards the end, at 5.18. Nobody in the world could afford it. It took strength in the arms and speed in the legs. It was told about his preparation: he runs carrying an iron tube vertically, strengthens the front muscles by making track laps raised on his arms, upside down, in short. With the rod he flew at 6.11 meters and said that 6.20 was possible. For him Nordic, a new US company, had studied a particular rod: very rigid, 5 meters and 20 centimeters long, but also very heavy, five kilos. While the previous one weighed three and a half kilos. But there were also many contraindications: a too high handle and the fact that such a special rod needed an athlete of 95 kilos and not of the 80 of Bubka. Judged too few. The Nordic computer had given the last word. Indeed it was a verdict: "not adapted to humans". To humans, in fact. But not to Bubka. Who immediately thanked them with a record, never mind if some new rods had broken.

There are two ways of interpreting the rod: it can be considered an artificial limb, an extension of oneself, or a foreign body, a means to be raped with all possible strength, in practice a catapult. Bubka always liked this second way, he was among the few who could afford it. Against every opponent and in all conditions. As Petrov explains in Elisa Chiari's beautiful book «L’altra faccia della medaglia»: «our plan was: first jump, to enter the race. Second jump, to win. Third jump, world record. Sergei set 35 of them, he stopped at 6.14 outdoors and 6.15 indoors. He could have reached 6.30 if he had had the time, if he had been young longer. He alone has jumped 49 times over six meters, the rest of the world just 31." Petrov explains why Bubka was unique. «I told him to do the exercise in a certain way, he did it better. Improving the records one centimeter at a time was our strategy, so there is more surprise and they remind you more." Bubka has held the scene for thirteen years with his records set inch by inch, city after city. Methodical, he did not chase a limit for the joy of improving himself. He was the accountant of the epic that he wrote. His roadmap coincides with the ranking of the best earnings. Forty, fifty appearances per year. Endless journeys, a thousand cities to go, between Donetsk and the western world ("and I go home, it takes 28 hours"), between the house in the south of France and the two hemispheres, in order to cover an athletic season that ran from January to September. Always perfect in speed, always absolute the technique (dozens of biomechanical studies testify it), always dealing with accidents. In strength training, he mainly favors the legs, "because without those there is no jump of the rod, the legs and femoral biceps are more important than the busts and the arms, because if there is no strength underneath, the rod doesn’t bend." Which is pure truth, absolutely and in relation to him. Just look at him: Bubka has no powerful shoulders, no arms that burst under the t-shirt; on his body there are few traces of the weight barbell and none, at least so it seems, of supporting drugs. He says that the abs play a big role in his preparation.

In the great business of athletics show, only Lewis (and perhaps Burrell) made more money than he did. This man is the first millionaire Soviet athlete, well before the national team football players. Last year he got rid of the last tie that held him back, of that bond by which the cachets passed from the federal offices of Moscow and arrived at the athlete shorn quite a lot.

Bubka, the farewell party of the angel of the platforms, 05.02.2001. By Emanuela Audisio.

It was the Tsar's last time. That’s why he chose Donetsk, his home, where in '93 he had flown to the indoor world championship. Those like him don’t care about gravity, they try to go as high as they can. He did not want official celebrations, dampish grips on memories, backwards run-ups. A jump and four friends are enough to say goodbye.

And the face of an old general, who doesn’t need to open his coat to show the medals: six consecutive world titles, 49 times over six meters. Sergei Bubka after twenty years has said no more, no more rod. "I'm sad because I quit, but happy to stay in the sport." In the sports hall, in front of six thousand people, the Ukrainian president gave him the title of hero of the country, Shevchenko, the IAAF and other personalities sent him a video of good wishes. The race was won by the Israeli Averbakh, with 5.80. Now Bubka, who is in the IOC executive committee, will take care of his sport as an executive. A couple of Christmases ago he had tendon surgery and for four months he had to sit still and limp. The doctors had told him that he could choose: to be an ordinary man and escaping the surgery or to be an athlete, but then they had to intervene, the infection was eating his bone. He had had no doubts: "open." Mister world championships is 37 years old, he has improved the world record 35 times, and in his life he has seen many skies and changed many shirts. He started with that of the USSR, moved to that of the CSI, to end with that of Ukraine, his country. He experienced the great season of the empire, the immense confusion of dismemberment, the difficulty of birth of the new Republic. «It was a trauma, even for us sportsmen. With the USSR we were used to a certain education, we didn't have to worry, the roles were clear, the philosophy of sport also, when we passed under the banner of the independent republics everything changed, we no longer understood anything, we didn't know to whom we had to pay attention, everyone had his own programs, his own hierarchies. It was the worst, the most uncertain, most difficult moment to endure for those who are athletes and need calm, safety.» They nicknamed him, Bubka, in many ways: tsar, emperor, Sputnik, terminator. Also for his habit of giving the world at least one world record per year. From ‘83 to ‘90 never a defeat in a world championship, the first man to fly over six meters, to believe it. Bubka, since he showed up on the platform at the age of 19 in ‘83, was not the best, the one who went higher, only for six minutes. When in Rome, on a late August 1984 night, a long-haired French pole vaulter, a platforms playboy, stole his record at 5.91 and then happily went to smoke a cigarette, Gauloise bien sur, thinking that the world would never move again that evening. He didn't know Bubka, who rose to 5.94 late at night and took back the sky forever. Ah yes, they said he was more interested in money than breaking down borders, otherwise why every time he ate an inch more, instead of taking a greedier jump? For him, Soviet and enemy, an American company studied very rigid rods, which no one else could use for lack of strength in the arms and speed in the legs. Bubka jumped, but he also ran the 100 meters in 10 '3 "and in the long jump he pushed himself to 8 meters. As a kid he had been a lively child: at three years old he had run away from home, at four he had risked drowning in a barrel, at five he had fallen from a tree and had not broken his neck just because a branch had softened the fall. As an adult he was not afraid to go around to challenge opponents, in their land, to jump, even with an ankle infiltration, as at the World Championships in Tokyo in '93, just as the coup was staged in Moscow and tanks occupied the streets. Only with the Olympics he was unlucky: the boycott prevented him from going to Los Angeles, the tsar mentality from the others, he won in Seoul in ’88 with 5.90, but seriously risked ending up eliminated. He only did it in the final jump, when he had nothing in front of him, if not the abyss. It was a nervous, desperate, humble run-up that ended in a nice and clean jump. In his life he has flown more than the Concorde, he has made more than 13 thousand jumps a year, he has been in the air two thousand times, he has spent a lifetime fighting and winning against the bar. He is now rich and well-organized, home in Monte Carlo and Berlin, he has a Ferrari and a Mercedes, he has two children, Vitaly (in honor of his former coach) and Sergei, who plays tennis well. Bubka returns to earth, the sky is no longer his. Here from below, thanks: for letting us touch it.

Serhiy Nazarovych Bubka, born 4 December 1963, is a Ukrainian former pole vaulter. He represented the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. He won six consecutive IAAF World Championships, an Olympic gold medal and broke the world record for men's pole vault 35 times. He was the first pole vaulter to clear 6.0 metres and 6.10 metres. He held the indoor world record of 6.15 meters, set on 21 February 1993 in Donetsk, Ukraine for almost 21 years until France's Renaud Lavillenie cleared 6.16 metres on 15 February 2014 at the same meet in the same arena. He is the current outdoor world record holder at 6.14 meters, a record he has held since 31 July 1994. Born in Luhansk, Bubka was a track-and-field athlete in the 100-meter dash and the long jump, but became a world-class champion only when he turned to the pole vault. By 1992, he was no longer bound to the Soviet system, and signed a contract with Nike that rewarded each world record performance with special bonuses of $40,000.

Sergey Bubka quotes:

“I love the pole vault because it is a professor's sport...”

“First do it, then say it.”

“I think that, generally, you need to live with your sport 24 hours a day.”

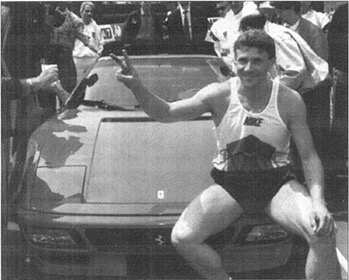

Bubka jumps in a Ferrari.

Setting a record at 2,033 meters above sea level in Sestriere in the 1990s meant returning home in a Ferrari. There was a Testarossa at stake and legends like Carl Lewis and Ben Johnson were coming to try to win it.

On July 31, 1994, happy as a child, or rather as his two children who sat next to him, Sergey Bubka moved the gear shift into first gear without scratching and pushed on the gas on the athletics track, as gas, at least for this time, had been paid by somebody else.

The car as well, of course: the famous Ferrari that had been at stake for the aspiring recordmen of the world for six years, and which found its owner on Berger's day, on the day of the other Ferraris, on the day of destiny, in the day in which the reds win, yes they win and a little also make them win, as in the case of the bet of the organizers of the mountain meeting. And let's say that, if their idea was to reward a champion with a super car, well, justice was done: Bubka jumped 6.14, improving his previous outdoor record, dated 1992. Renaud Lavillenie was eight years old and it will take twenty years for him to beat that measure. How could the record-breaking man fail to accept the gracious invitation of his little children, Vitalj and Sergey junior, who had told him before the race: dad, do your best today, as you have to give us the Ferrari? Seeing Sergey senior accelerate and caress his children glued in front of the dashboard of the flaming Testarossa, let us think that perhaps the decline that was so much talked about, the alleged end of Bubka's ability to regulate his athletic talent to achieve record on command, maybe it was just a story. Sorry, but 30 years are few to say that I am finishing, he must have thought while he was attacking the platform pushed by a friendly wind, while planting his stiffest rod, while flying over 6.14 just stroking, but respecting it, the rod, which in fact didn’t fall. It was the first attempt to the quota record, probably already passed in the previous jump, a 5.90 passed by leaving a window of light between his body and the bar that would herald the feat: "I only had problems at 5.70, on the first attempt. But the conditions were fabulous, I felt good, nice wind, nice platform, nice people around. So I made the record, but without a perfect jump, let's say it was a normal jump. If I were physically the one of '91, I would jump 6.20 - 6.30." And he was smiling, and go with the spider, with the pats on the shoulder of envious colleagues, with the hugs of his wife Lilia. On the other hand, Ferrari aside, Bubka was keen to silence the skeptics and insinuators. "It’s that, when you are someone like me - he explained after the jump - one who has won four world championships and made 35 records, who is a nice piece of athletic history, every meeting becomes an obsession, everyone is waiting for the primacy, everyone wants, almost pretends that you go higher and higher. But I am a human being, you know? And sometimes humans get tired." They get tired inside, he means. Because those of the head, of motivations, are fragile mechanisms even for those who have gained and won since eleven years, having only themselves as an opponent. In Barcelona, Olympics' 92, Bubka missed the three entry jumps, at 5.70 (the third at 5.75), and went home saying that psychological pressure had crushed him. For this reason, to save his mental tank, this year he decided to compete less, not to go to the European Championships ("competitions with the titles at stake are too stressful, I can no longer do one of them a year"), in short , to "rest". For this reason, in March he had gone alone to a wooden refuge in the woods in Sweden: a week to chopping wood and reading books. "I felt the physical need for solitude," he said and, in the end, in this there is everything, because even the champions, if they don’t brake, end up clashing with life.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment