Williams Racing marks 750 Grands Prix in Formula 1. 10 May 2021.

Williams Racing will celebrate a landmark moment at the fifth race of the 2021 Formula One season, as the iconic British team becomes only the third in the sport’s history to participate in 750 Grands Prix.

This significant achievement is being marked in the run up to the Monaco Grand Prix with a multi-channel campaign planned to highlight the incredible journey of the organization founded by Sir Frank Williams and Sir Patrick Head in 1977.

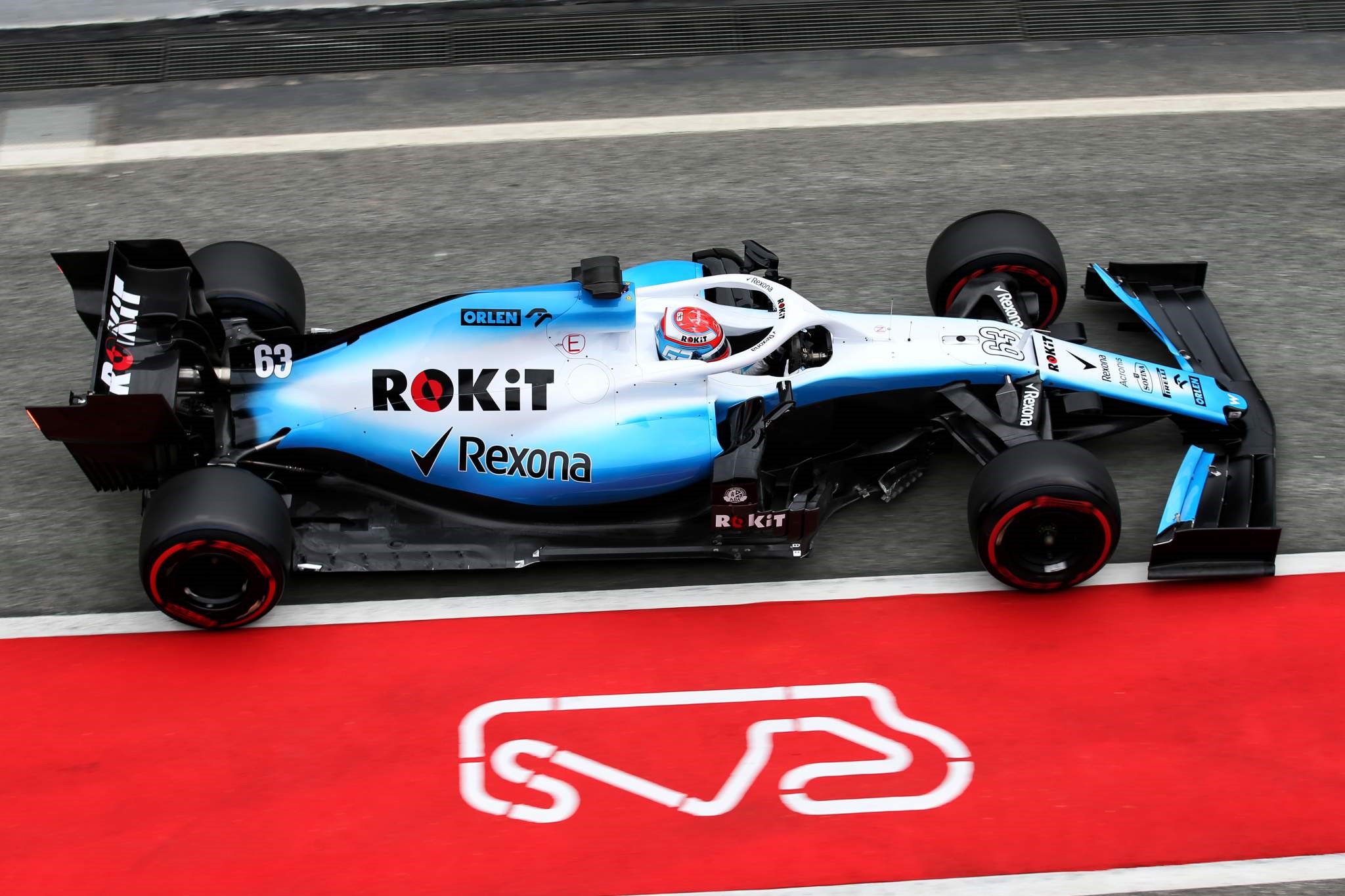

George Russell at Monaco GP in 2021.

Since its inception, a core foundation of Williams Racing has been its people. When you join the team as a driver, a staff member, or a supporter you become a part of the Williams story. With only Ferrari and McLaren having participated in more Grands Prix events, Williams will celebrate the anniversary by encouraging supporters, employees and other sporting personalities to remember the race or the moment in their lives they began following and supporting Williams and then asking a simple question: what’s your race number? After finding out their race number using a bespoke calculator on the Williams website, 100 lucky fans will see their name carried on the halo of the FW43B over the Monaco weekend.

Jost Capito, CEO of Williams Racing, commented: “Williams has always been about people; those that work for the team, along with our fans from all across the world. This milestone is about celebrating everyone that has been on this journey to 750 Grands Prix and will continue to be on this journey with us, as the team heads into a new era. We’re excited to share some of the incredible stories that have made the team what it is today and hear from supporters who have their own amazing tales of what Williams means to them.”

Supporting content will be available to watch that will draw out some of the inspirational stories from the people that have made the team such an iconic sporting brand.

For a limited time, fans will be able to purchase celebratory Williams Racing Umbro 750 Grands Prix merchandise as well as a special Automobilist poster that will be on sale to mark the occasion.

At the Monaco Grand Prix itself, the FW43B will carry a special ‘750 Grands Prix’ logo, whilst each team member’s race count will feature on their individual kit.

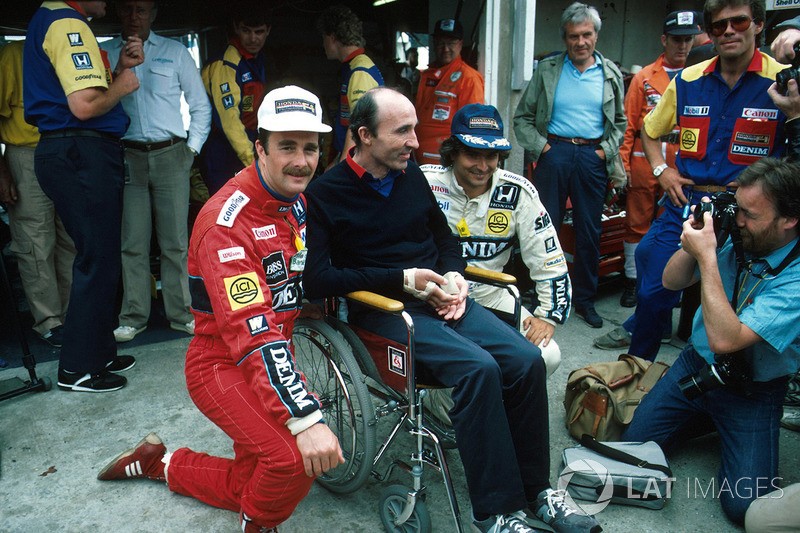

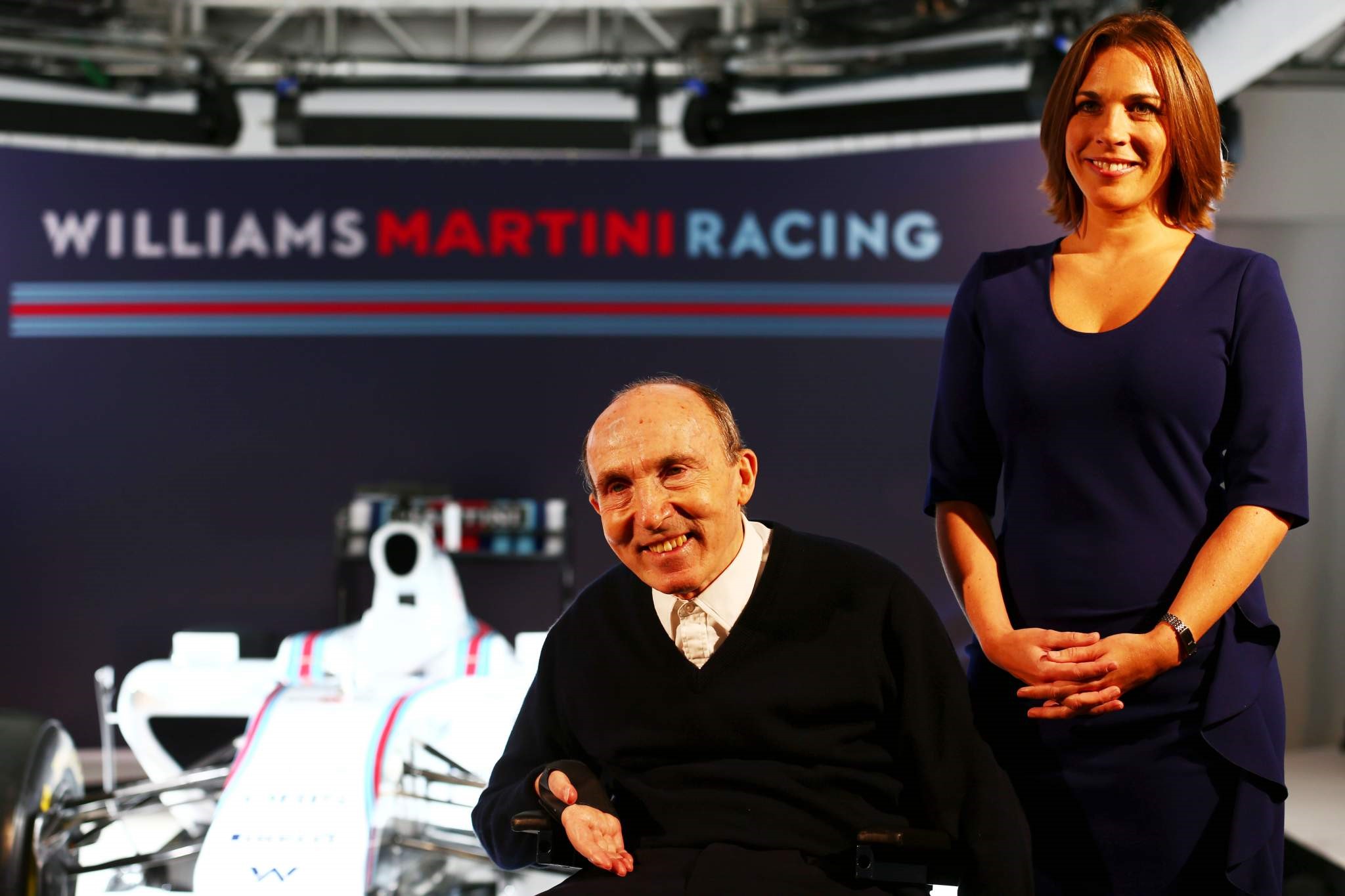

All this seemed over 35 years ago. It was March 1986 and Frank Williams was on his way to Nice airport to return home after witnessing his team’s tests at Paul Ricard. That day he paid dearly for his love of speed and found himself miraculously alive, but in a wheelchair. Enough with running, the hobby he loved so much, but not with racing.

He couldn’t use his legs anymore, Frank, but he could still count on his extraordinary willpower.

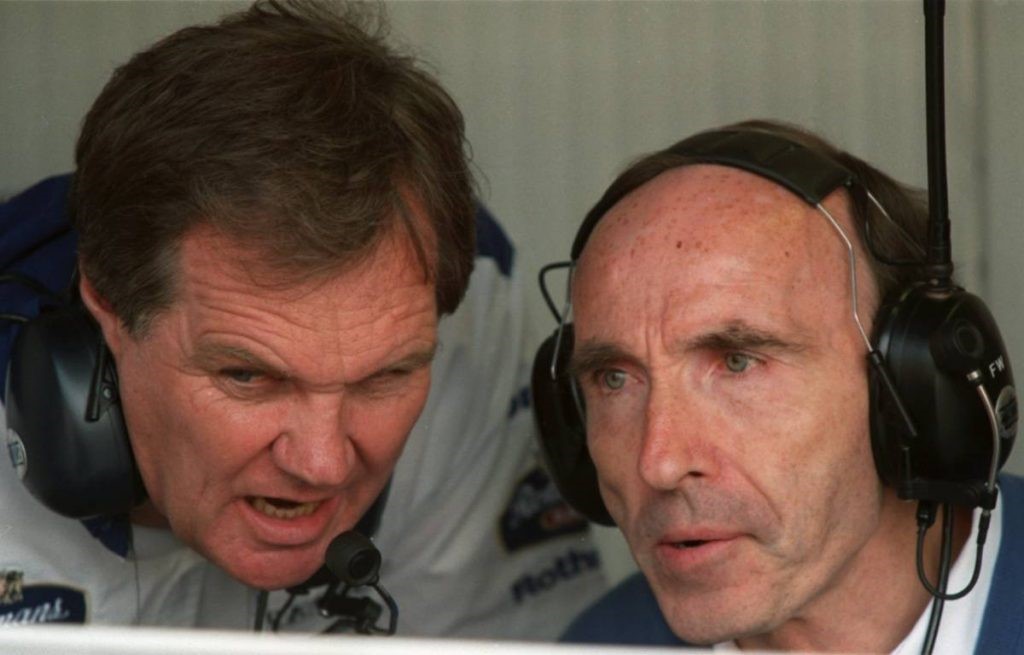

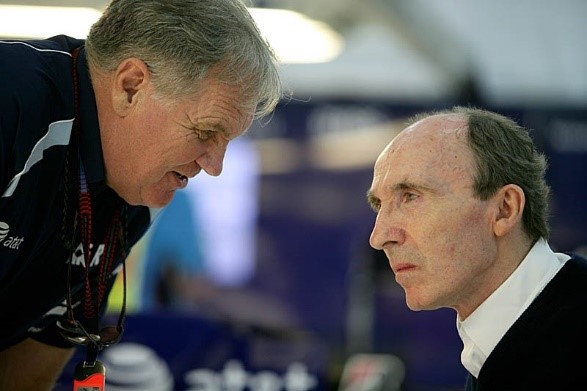

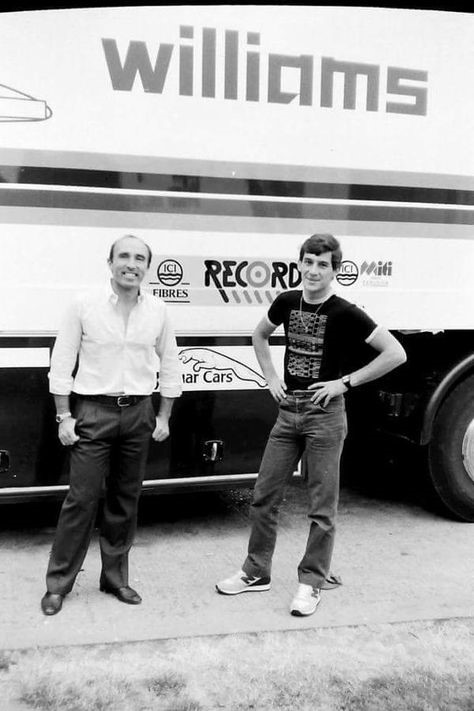

Frank Williams and Patrick Head.

His stable, in his absence, went on thanks to an extraordinary woman, Virginia, his wife and a sincere friend, Patrick Head, “his” engineer. She thought of feeding her husband’s dream by staying close to him while waiting for him to recover, while Patrick took care of the whole team practically alone.

Frank Williams made it, to continue writing the stories of a story that that day, without him, seemed to have to finish. Today Sir Frank watches everything from his home in England, with his daughter Claire, which failed to give prestige to one of the most successful teams ever in the history of Formula 1. It’s almost strange to say it today but, before it arrived Dorilton Capital with the money needed to keep the team alive, there was a time when Williams Racing was synonymous with excellence and victory.

Williams is a 2017 documentary film directed by Morgan Matthews starring Tim Prior and Emily Bevan.

It is a story that deserves a documentary, that of Frank Williams, who in fact has already ended up in film with “Williams”, the docu-film dedicated to him inspired by the book “A different kind of life“, written by his wife, who retraced their stories. Today, the regret of not being in the pits anymore is however contrasted by the pride of seeing the Williams name still on the track, even if with different capital and people to command. The same people who are trying to give a future that Frank and Claire’s family was no longer able to guarantee, on pain of the definitive closure of a team that, despite the difficulties of the present, cannot miss on the starting grid.

The current Grove team has a history of successes, triumphs, falls and ascents. And it is not a way of saying, but the chronicle of the facts. Since the fatal accident of Ayrton, it has been a slow decline, perhaps imperceptible in the early years but increasingly rapid in more recent seasons. The 2003 was the last year of the world dream, with Juan Pablo Montoya and Ralf Schumacher not to take advantage of a delicious FW25 and a great engine supplied by BMW, while the latest success is the work of Pastor Maldonado, Barcelona 2012. The latest of 114 wins, useful for reaching an incredible number of titles: 16 in all, 7 Drivers and 9 Constructors. For almost two years the team has not been able to score any points, but for the future there is a little more confidence: Jost Got it is the name that Dorilton Capital has relied on to restart, a 750 GP long adventure that does not want to finish yet.

‘Frank was horrified when he first saw me’ – Patrick Head reflects on Williams' origins as they reach 750th GP landmark. Lawrence Barretto. 18 May 2021.

Patrick Head and Frank Williams.

At Monaco this year, Williams will become the third team in Formula 1 history to participate in 750 Grands Prix – and Sir Patrick Head was a part of the iconic British team for the vast majority of those, having co-founded the squad with Sir Frank Williams and played a key role in steering the ship before retiring at the end of 2011.

And it all was made possible because he was building a boat in the Surrey Docks – while working for Lola in his first stint of F1 – when he ran out of money. He’d heard Frank was looking for someone, so thought he’d work for him for six months to earn enough cash to finish his boat and then get back to building it.

His life, though, took a very different turn. Over the course of 36 years, he built a Formula 1 team into one of the most successful operations in the sport’s history, winning nine constructors’ championships, seven drivers’ titles and 113 Grands Prix.

“I had a £40 Renault R4 van which was brush painted,” Head recalls when we talk ahead of F1’s return to Monaco. “Frank had said to meet at the Carlton Tower, so I turned up, smelling of resorcinol resin, which is very strong wood adhesive and in a jersey and pair of jeans. I strolled in and there was Frank in a Dougie Hayward suit. I think he was rather horrified when he saw me.

The origins of Williams

“We talked for a short while, not longer than 30 minutes and he told me I started on Monday as Chief Designer. I have always held Frank in good regard. His energy and enthusiasm were his most outstanding points. I was strong on the engineering side and that’s why we made a good combination.

1976 United States Grand Prix West, Long Beach, California, USA. Frank Williams with Jacky Ickx (BE), Williams FW05.

But, at end of 1976, Frank was shown the door after selling the team to Walter Wolf. I stayed on because I was in charge of the test team and things were starting to move on for me there.”

But then he got a phone call, while out in South Africa testing with Jody Scheckter at Kyalami. It was Frank. He had a proposition. “‘I’m starting my own team, chap, do you want to come and join me?’ I replied ‘I can’t give you an answer now, I’ll think about it on the plane back and give you a call’. I thought, if I’m going to make a move, I better do it now, so I did it. We got Patrick Neve as a driver and he brought £100,000, Frank put together nearly £100,000, so we had nearly £200,000 for the whole of our first year. With that, we had to buy the car, the engines, employ the people, get the factory, buy a few machine tools – everything. I think we did 10 out of 16 Grands Prix with just one car, which you could do at that time, because that’s all we could afford. Now you wouldn’t be able to start in the way we did.”

And so Williams Grand Prix Engineering was born, starting out of an old carpet factory. Frank was responsible for finding the money and running the team, Head was responsible for the design and operations. Between them, they made quite a splash – and quickly.

“We opened the doors of the factory, or rather broke the doors down, on March 28 1977,” said Head.“The factory had the most filthy floor; it had been a carpet warehouse or something. It had no machinery, no equipment, nothing. It needed everything setting up and we were just desperate to get going.

Patrick Head and Frank Williams at British Grand Prix in 1980.

We won our first Grand Prix in 1979, two years later and we won the World Championship in 1980, three years after we started. The world was quite different then, of course. You could go to Cosworth and the engines were pretty cheap, around £7,500 per unit. We paid Max Mosley around £15,000 for a March, which came with a gearbox and just ran one car. We bought a spare gearbox too, just in case. But, ahead of 1978, it became clear we needed our own car. So I set about working on that.”

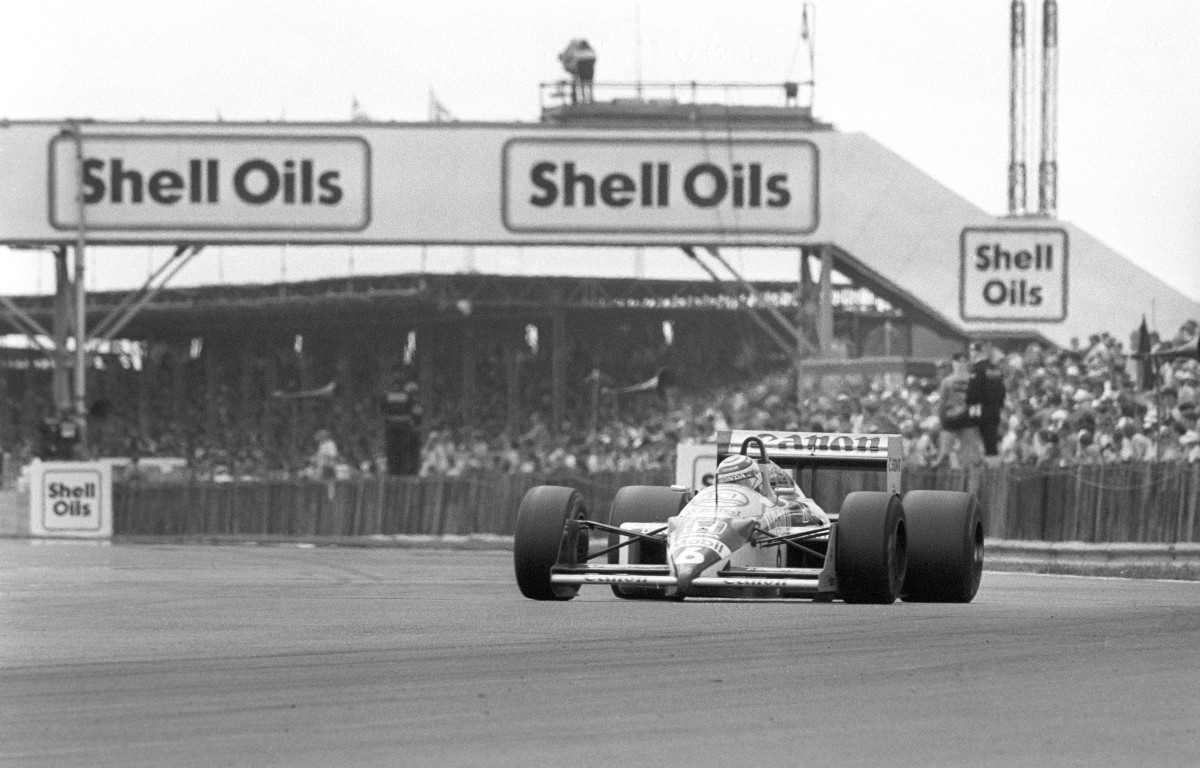

Alan Jones en route to the 1980 drivers' title.

It was Head’s car that Alan Jones steered to both titles in 1980, as Williams announced itself as a force to be reckoned with.

F1 British GP 1986, winner Nigel Mansell with team boss Frank Williams and team mate Nelson Piquet.

"The first big difference between Lotus and Williams is the minimum percentage of nonsense that Williams does. They want to know all the causes of the breakdowns, or the explanations of the mistakes; they have never wasted time screaming or crying. My relationship was therefore perfect from the start. When I first tested with Frank's team, it felt like I went back in time: because you work like at Lotus in the Chapman era." Nigel Mansell

He then took over the running of the team when Frank had his accident in 1986, with the outfit winning the constructors’ that season and both championships the following year. “The way Frank and I had set the team up, everything was in place to continue running when he had his accident,” said Head. “But the team naturally missed his energy and enthusiasm. We were working with Honda at the time and, with Frank in hospital, I dealt with them and flew to Japan 16 times that year – and also went to every race and every test so, by the end of the year, I was exhausted. It wasn’t the easiest of years, but we won the constructors’ championship.”

Patrick Head, Nelson Piquet, Grand Prix of Austria, Osterreichring, 16 August 1987. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

When Honda left at the end of 1987 to hook up with McLaren because they wanted to link up with Ayrton Senna, Williams were in a bit of a bind. Head says Honda offered to carry on with them – but they turned the offer down. “They wanted us to keep Nelson Piquet and get rid of Nigel Mansell and take on Satoru Nakajima. Frank and I sat down and thought about it. Ultimately, it put us in a position where we would be number two to McLaren. There was no way were we going to accept that.”

Williams made hay with Honda in 1987.

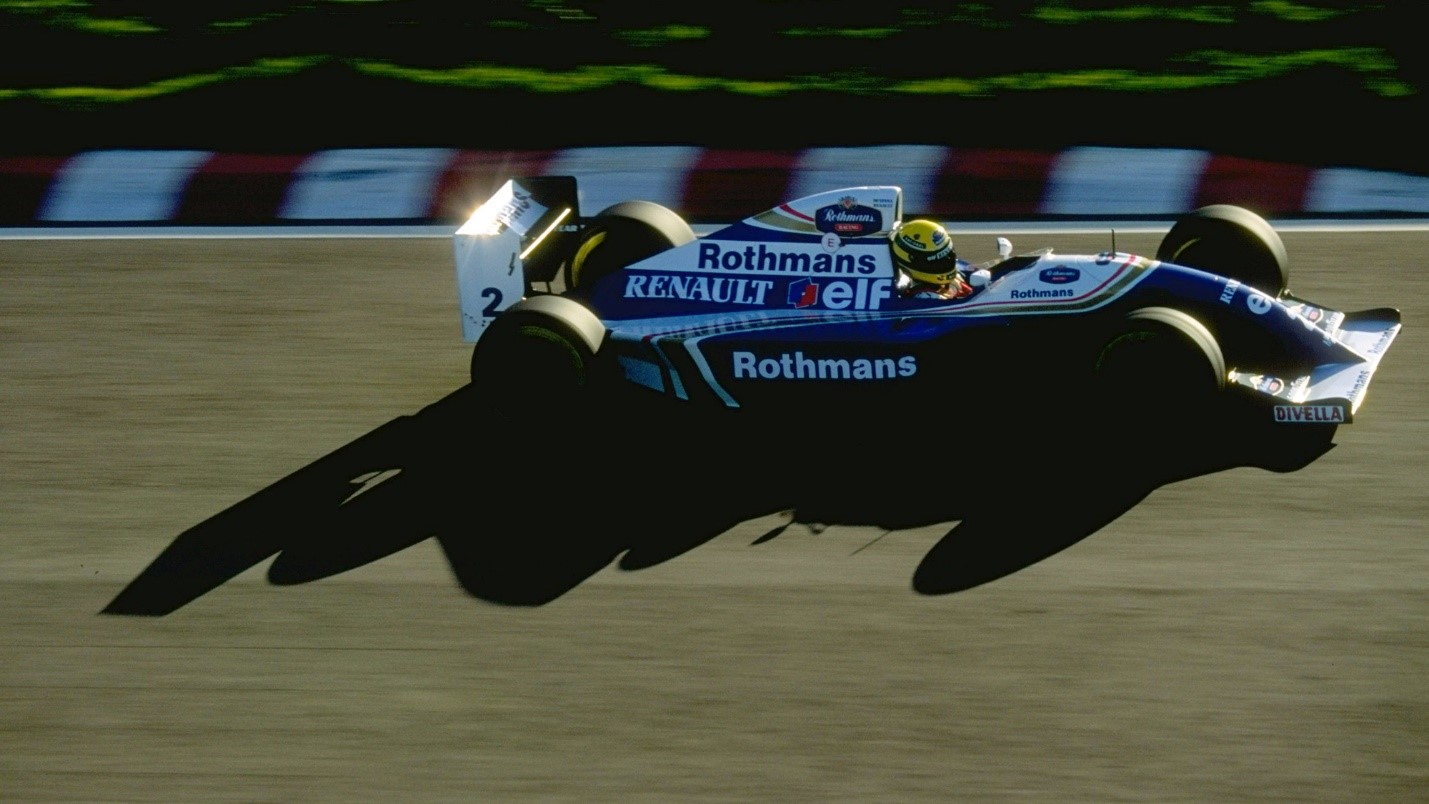

They spent a year with Judd engines, before snapping up an offer from Renault to join forces. In terms of performance, this was a hugely successful period, with the team winning four drivers’ and five constructors’ titles before Renault left at the end of 1997 – but it was also a dark time, with the death of Senna at Imola in 1994 at the wheel of a Williams.

Frank Williams and Ayrton Senna.

“Although that period was successful on track, in my mind that day at Imola coloured any retrospective pleasure looking back on those days,” says Head, who four years prior to the Imola crash had recruited Adrian Newey – who has gone on to be one of the sport’s most successful design gurus. “It was real psychological struggle for both Adrian and I. We both had private moments about whether we should carry on in the business.”

After flitting between engine manufacturers and paying for them as a customer, having lost the Renault works deal, Williams joined forces with BMW for 2000 and, over the next six years, they won 10 races together. But Head says the relationship started to struggle when it became clear BMW wanted to start their own team – and ultimately they split at the end of 2005. Since then, life for Williams has been very tricky, with just one win – Pastor Maldonado triumphing in Spain in 2012 – over the next 14 full seasons.

Head says Ayrton Senna's death in 1994 tainted his memories of Williams' most successful period.

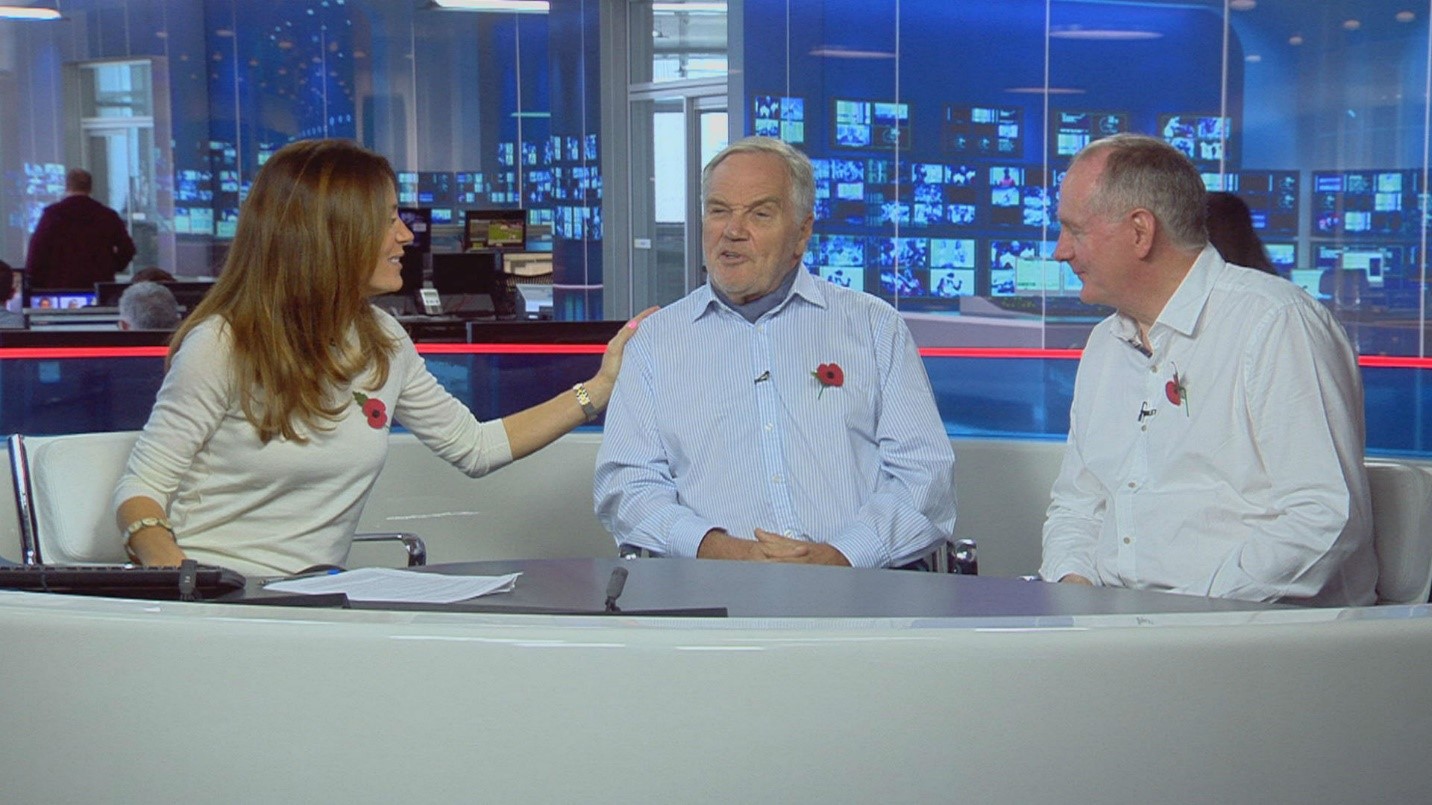

Head called time on his career at the end of 2011 and, though he came back briefly in 2019 as a consultant, has since largely been focusing on enjoying his retirement, splitting his time between Sardinia and the UK.

Interlagos, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 27th November 2011. Ron Dennis, CEO McLaren, on the grid with Patrick Head. Lat photographic.

While times are much tougher for Williams right now, things have turned around with new owners Dorilton Capital pumping investment into the team and this year they’ve already proved they are no longer at the back of the pack.

When Head looks back on his time at Williams, as the team he co-founded approaches an incredible 750th Grand Prix, his memories are overwhelmingly positive. “I’ve only got good things to say about Frank,” said Head. “We’ve had short-term barnies but we always sorted them out. We got on very well and made a good team. Frank and I tried to keep some of the atmosphere of the team from the early days throughout our time in charge. If anyone had a problem, they could walk into Frank or my office.

“The team had a very nice feel about it – and I think we had a very good relationship with people. Many of them I’m still in contact with and they look back on their time at Williams fondly, as do I. And I wish them all the best for the future.”

Adam Cooper traces the story of one of Formula 1's great constructors.

Piquet became the third Williams World Champion in '87, here overtaking Pascal Fabre in Brazil. Gilles Levent/DPPI.

Where it all began: Neve drives to a 12th place finish at Jarama in 1977. Bernard Cahier / Getty Images.

On the team’s debut Spain Neve qualified a humble 22nd and finished 12th, four laps down on winner Mario Andretti.

“The budget was supposed to be £200,000,” says Head. “Neve was supposed to bring £100,000 and Frank was supposed to put in £100,000. We ended up having £180,000 because he only got £80,000 together, but in those days it was quite a lot of money.

“I didn’t actually poke my nose into too much of the budgeting, but we were spending almost nothing. We were on cheap flights and staying in some of Frank’s cheap deal hotels. At that time it was all good fun, but I’m not sure I’d be too happy about some of those places now! At each circuit we just rented a little caravan as our motorhome.

“That year we did 10 races and I think there were three when we didn’t qualify. That really gets through to you; when you are packing up and leaving on Saturday evening and everybody else is staying around and preparing their cars for the race, it hurts. It really does …”

Neve scraped into the top 10 four times, including a lucky seventh at Monza, but he did little to capture any headlines. However, in January 1978, new signing Alan Jones sat on the grid in Argentina in the Head-designed, Saudia-sponsored Williams FW06.

Patrick Head, Frank Williams and Alan Jones in Argentina in 1980. DPPI.

“We had about £350,000 in ’78, which a workable budget for one car,” says Head. “But Frank still had us staying in his cheap hotels! The 06 was a nicely balanced car and it suited Alan Jones very well. He liked throwing a car around. But he used to say to me all the time, ‘I tell you Patrick, those bloody Lotuses just don’t slide!’”

Williams attracted more sponsorship and hired Clay Regazzoni as second driver for 1979, while Head set to work on designing the FW07. The target was obvious – design a better and more effective Lotus 79.

The FW07 made its race debut at Jarama, and it immediately impressed.

Williams at Monaco Grand Prix.

Jones showed well, but retired in his early races with it and then Regazzoni finished a superb second in Monaco.

The team made a crucial aerodynamic breakthrough at the Silverstone test, just before the British GP. Come the race Jones gave the car its first pole, but he retired due to a water leak. Regazzoni saved the day by earning a first-ever victory for Williams. Jones made amends by winning four of the season’s remaining six races and the FW07 was the car to beat.

Silverstone ’79 win for Regazzoni was Williams’ first. Jones would pick up four more that season. Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

Head sums it up thus: “going to outboard rear brakes, having a sound structure for the car, long sidepods that meant that we didn’t have to run big front wings and a skirt system that worked. Those things meant that the 07 was the car it was.”

The team had momentum on its side heading into 1980 and Jones won the opening race in Argentina with a standard FW07. He subsequently scored four more wins with the B-spec car, which featured upgraded aero, on his way to claiming the team’s first World Championship. New team-mate Carlos Reutemann added a success in Monaco and his consistent scoring helped Williams to claim the constructors’ crown.

FW07 gave Williams its first World Championship with Jones. Grand Prix Photo.

The 1981 season saw a ban on skirts and controversy over hydraulic suspension systems. Jones and Reutemann shared four more wins with the revised FW07C, which had a stiffer chassis and Williams earned a second constructors’ crown. The Argentine driver missed out on the title after a lacklustre showing in the Las Vegas finale.

By the end of 1981 it was clear that turbos would be dominant in the coming seasons and, in the absence of a suitable engine deal, Williams began to look for ways of getting more shelf life out of the Cosworth engine. Head designed an all-new FW08 six-wheeler, only for it to be made obsolete when it was decided that F1 cars could only have four wheels.

“We had the rug pulled out from under us even before we decided if we were going to race it. For a while I thought we’ve got to make the 07 last longer, then we’d bring out something much later in the year. I probably spent a month thinking about it.”

In the end he decided to keep the FW08 design and fit a standard 07 rear end, resulting in a car that had a relatively short wheelbase, as the chassis has been designed to ensure that the six-wheeler wasn’t too long. Keke Rosberg scored only one victory, at Dijon.

However, he managed to win the 1982 title.

“It was a very simple little car. Keke had such quick steering movements and I think it just suited him very well. He loved driving it. It was a car that Keke could use.”

Rosberg (here at Zandvoort) claimed the 1982 season with a single win, in a tragic year for Ferrari. Grand Prix photo.

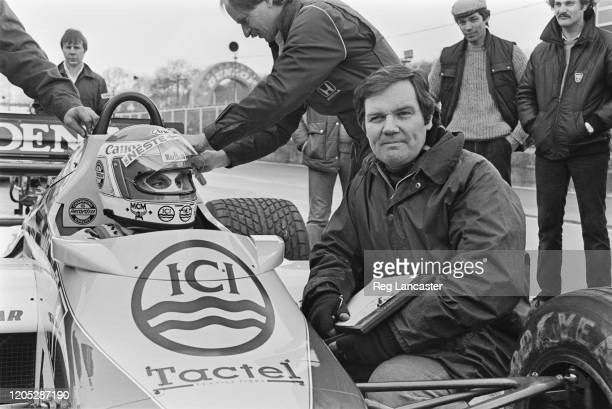

For the 1983 flat bottom rules, Head created the FW08C, distinguished by its stubby sidepods. By now turbos were unbeatable except on street circuits and Rosberg scored a memorable win in Monaco. In September the car was involved in a little bit of history when Williams gave Ayrton Senna his first-ever F1 test at Donington.

By then the team had a new relationship with Honda, inspired in part by a recommendation from Ron Tauranac. The FW09 made its race debut late in the 1983 season and heading into 1984, there were still lots of reliability issues.

Keke Rosberg, Patrick Head and Frank Williams in 1984.

However, the Williams-Honda scored its first win in Rosberg’s hands in Dallas in 1984. For 1985, the package was much improved and it gave Nigel Mansell his first GP victories.

In a 1986 season that began with the terrible road crash for Frank in France, his new signing Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell won most of the races – but they lost the title to McLaren’s Alain Prost in the season finale.

Williams had championship pace in ’86 but Mansell - here at Brands Hatch - and Piquet lost out to Prost. Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

“We won a lot of races but not the drivers’ championship. Frank was really not involved for the whole of that season, he had his accident and had broken his neck in March 1986 and, although he did appear in a wheelchair at Brands Hatch, he wasn’t involved or at the company at all. And, looking back on it, probably I should have been more authoritarian.

“We didn’t have anything in contracts that said that one driver had to be favoured over the other. And so it was a bit awkward early in the year when Frank was not able to communicate with us.”

In 1987 Williams and Honda were again the dominant force and Piquet beat Mansell to the World Championship. However, by the end of that year, Williams and Honda had agreed to part, essentially after a disagreement over taking Satoru Nakajima.

Williams used uncompetitive Judd engines in 1988 and got lost as it tried to develop an active ride system that Mansell hated: “in the aftermath of losing Honda we tried too hard really and gave ourselves too many engineering challenges,” says Head. “We had the débâcle of active ride in 1988, when we had to take it off the car for all sorts of reasons.”

Head insists that he never felt frustrated as McLaren scored success after success with Honda: “I was up to my eyeballs in work and I’ve never been one to look backwards and say something’s not fair. I think if I ever had any of that in me as my character, my father would have kicked it out of me when I was 16 or something, because he was a fairly tough character!

“And so I didn’t sit and look back, it was just get on with the future. And we signed up with Renault and I think we won a couple of races with Renault in the first year. The belt drive was pretty unreliable. So it wasn’t really a championship potential engine in 1989. It took us ’89 and ’90 and then we started getting serious in ’91.

“And I accept full blame for not winning the championship in 1991. It was our first semi-automatic gearbox and, for the most stupid of reasons, it was unreliable. But, after three or four races, we considerably outscored McLaren, but we weren’t able to catch up with them.”

“And, by that time, the active car was beginning to do better lap times than the passive car and delivering the promise that was always seen theoretically.”

In 1991 Williams had perfected the active suspension system on the FW14 and the FW14B of 1992 was to be dominant, helped by the input of the brilliant Adrian Newey, who became a huge influence on the team.

Unstoppable: Mansell and the FW14B. Grand Prix photo.

“In 1991 Nigel and Riccardo Patrese were very close together on performance but, in ’92, Nigel stepped up relative to Riccardo,” says Head. “The main reason was the feeling and feedback from the active system. Nigel worked out that providing you could persuade yourself to trust it, it would be there once you had got into the corner. Nigel adapted to it, but Riccardo always wished it was a standard car.

“The good work was done over the winter and then it was a question of just running the car. I think, by the end of the year, McLaren were beginning to make good progress with their active system and they were getting it to work pretty well.”

Alain Prost, Williams FW15, in 1993.

Mansell left at the end of the 1992 season and, in 1993, Alain Prost dominated the World Championship in the FW15.

“We started work on the 15 towards the end of ‘91 and it was intended to be the ‘92 car, but we decided to start the season with the 14B. With the 14B it was a relatively straightforward conversion from off to on, whereas the 15 was a committed active car, with no either/or. However, we seemed to be so strong and thought, ‘maybe we don’t need to bring the 15 in this year.’

“The FW15 in 1993 wasn’t a bad car, but I don’t think it was a particularly significant step better than the FW14B. There could have been an argument that we might have done better to develop the 14B and run that in ’93, but your tendency is always to do a new car.”

Prost retired at the end of 1993, as his old nemesis Senna joined the team. Then 1994 brought tragedy when the Brazilian was killed at Imola.

“I must say, undoubtedly, Ayrton was a very, very special driver,” says Head. “He left McLaren expecting to climb into a perfect car and the car wasn’t perfect. The unfortunate thing is, by the time we started the Grand Prix at Imola, the car was a lot better and he was absolutely convinced that he was going to win the race.”

Senna testing the 1994 Williams: Imola was the third race of the season. Mike Hewitt/Allsport via Getty Images.

Damon Hill challenged for the 1994 title, but he lost out to Michael Schumacher at the final race. Hill continued to be a race winner with the FW17 in 1995, but made too many mistakes and again lost to Schumacher.

“We finished the 1995 season with the general feeling that we should have won the championship. We were probably not very good at driver psychology. I think Damon felt that we felt that he should have won the championship. I have to say I admire how he responded. I think there was a suggestion that Michael was fitter than he was and Michael could operate like a qualifying lap every lap, more so than Damon had.

“But Damon got himself enormously fit and he lost the feeling of inferiority to Michael, I think he felt he was just as fit as Michael. So he turned up in 1996 as the same basic personality, but a much more self-confident, focused, ‘let’s do this job’ person than we had finished with in ‘95. The car was good and, apart from one or two little hiccups early in the season, we started scoring and looked as if we could take the championship that year.”

The title contenders, ’94-’96. Grand Prix photo.

Hill duly beat new team-mate Jacques Villeneuve to the 1996 World Championship. At the end of that season Newey left, but Villeneuve went on to win the 1997 title. That was to be the last year with works Renault power: “the ’97 car was mapped out by Adrian, who stood down at the end of ’96. We had people good enough to deal with any problems. I don’t think the development rate was that fast year-to-year at that time.”

A new works deal was agreed with BMW and, meanwhile, the team had two difficult years with Mecachrome/Supertec engines. In 2000 Williams gave Jenson Button his debut and raced with BMW power for the first time and, as with the early days with Honda and Renault, there were lots of reliability issues.

“The BMW was a very big, bulky, rather heavy engine. But it was powerful, no doubt about that. I think BMW were up to their eyeballs keeping engines going. We always used to change the engine for the race, but we had engine changes in the middle of practice, we had engine changes on Friday night. We had a lot of engine changes. And for BMW just keeping up with it was a massive effort.”

By 2001 Williams and BMW were winning races and challenging pacesetters Ferrari and McLaren and, in 2003, Juan Pablo Montoya and Ralf Schumacher were potential title contenders with the FW25, but the crown slipped away.

“We could very easily have won the championship. There was complete and total animosity between Montoya and Ralf. I couldn’t believe how childish the two were in the latter part of that season. But we were definitely the fastest car, aided by a very powerful BMW engine.”

Head says animosity between Montoya and Schumacher, here in Monaco, cost Williams the 2003 title. Grand Prix photo.

It was around that time that Head reduced his day-to-day technical responsibilities.

“I stepped down from being technical director and handed over to Sam Michael in 2004, after we sort of got ourselves competitive in 2003 but, for stupid reasons, blew the last three races. And we started 2004 with that dreadful short nose with two fins on it. I was by that time living in London and commuting and I didn’t feel I was keeping enough control over what was going on.”

Meanwhile BMW had ambitions to own an F1 team: “they offered to buy Williams, for a very, very low sum. And we said no, so they then went off and later on they did their deal with Sauber. I think if we’d been cleverer, we could have avoided that split.

“But it would have meant literally having them at Grove telling us what to do. And I don’t think I was prepared for that. I would say that, from 2001 to 2005 when we had a decent engine, we won 10 Grands Prix. From 2006 until they pulled out, four years, they only won one Grand Prix!”

As the decade progressed, Head remained involved with Williams but with reduced responsibilities. The team gradually slipped from competitiveness as it moved from BMW to Cosworth to Toyota back to Cosworth. In 2011 Head sold the majority of his shares and reduced his involvement further.

Rosberg retires his Williams-Toyota at Indianapolis in 2007. Eric Vargiolu / DPPI.

In 2012 there was a reunion with Renault. Pastor Maldonado scored a shock pole and win in Spain that year – it remains the most recent success. There was a return to form with Mercedes power in the early days of the hybrid era, with Felipe Massa and Valtteri Bottas, but then the team went into a slump. By then Head was no longer directly involved, but in 2019 he made a brief return as a consultant.

Head sold the remainder of his shares as part of the recent purchase by Dorilton that saw the Williams family formally leave. With Jost Capito at the helm, the team is making solid progress – and the German has made it clear that the new management has enormous respect for Frank and Patrick.

“Frank and I were a good pair,” says Head. “Would I have started a Grand Prix team? No, I never would have done on my own. Frank had the blind confidence. He was a person who put his head on the pillow and went to sleep and slept 10 hours every night. And I was a worrier, completely opposite. But we were a pair that worked well together.”

Patrick Head: 'Williams struggling to stay alive without technical leadership'. June 26th 2020.

Patrick Head, speaking in the latest Motor Sport podcast, has said that Williams cannot afford a repeat of the past two seasons where it finished last in the F1 Constructors' Championship. By Motor Sport.

Eric Vargiolu / DPPI.

Patrick Head has warned that Williams is in a fight for survival, after years without the technical leadership that it needs.

In the latest Motor Sport podcast, the co-founder of the team says that Williams cannot survive by running at the back of the grid as it has done in the last two seasons and that it needs to compete in the midfield this year.

Earlier this month, Williams announced that it is looking for additional funding, which may include selling the entire company.

George Russell, Williams.

Head describes the team’s current situation as “sad”. “You cannot run an F1 commercially finishing tenth out of ten consistently,” he says. “For this year it’s very important they get back in the hunt. I’m not naive enough to think they will be battling with the top three teams but I hope they will be in amongst what would be called the lower midfield. From there they have to work their way back and upwards.

Head returned to Williams in a short-term consultancy role last season. He praises deputy team principal Claire Williams for the work that she has done in “putting together a significant budget for this year”, despite the results of the past two seasons and blames a lack of technical leadership for the current woes.

“There are some fantastic and good people there,” he says. “For various reasons, without necessarily wanting to say that the people are bad, they have had a stream of technical leaders, some of whom had skills but have not been appropriate for leading a company like Williams and, steadily, they are struggling to stay alive at the moment.

“They need technical leadership there.”

After years of stability and success, Williams has struggled to find a long-term technical director in the past decade. Mike Coughlan had only been in the role for two years when he was replaced by Pat Symonds, mid-way through a 2013 season in which the team scored just five points.

Symonds oversaw a resurgence in its fortunes, as new regulations and a switch to Mercedes engines saw the team finish third in the championship in 2014 and 2015.

He left at the end of 2016 and Paddy Lowe’s term as chief technical officer began, following success at Mercedes.

In 2018, the team slumped to last place in the championship with seven points. Lowe left in 2019, shortly after the new car was late to the first testing session of the season.

Head praised two hirings announced earlier this year, describing them as “good guys”. David Warner has joined from Red Bull as chief designer, along with Jonathan Carter, formerly at Renault, who is deputy chief designer.

For 27 years from 1977 Sir Patrick Head, born 5 June 1946, was technical director at Williams Grand Prix Engineering and responsible for many innovations within F1.

Patrick Head was born into motor sport, his father Michael racing Jaguar sportscars in the 1950s and was privately educated at Wellington College. After leaving school, Head joined the Royal Navy but soon realised that a career in the military was not how he wanted to spend his life and so left to attend University, first in Birmingham and later, after failing his first year exams, at UCL. Head graduated in 1970 with a Mechanical Engineering degree and immediately joined the chassis manufacturer Lola in Huntingdon. Here he formed a friendly relationship with John Barnard, whose Formula One designs for McLaren, Benetton and Ferrari would later go on to compete against Williams. Head was involved in a number of new projects all trying to become established as car builders or engineering companies and it was during this period that Head and Frank Williams met. Finally, becoming disillusioned by his lack of success, Head quit motor racing to work on building boats but was lured back by Williams to join his team, which Head did during 1975.

In 1976 thirty-four-year-old Frank Williams decided that the time was right to re-form his own team and promptly set about luring Head back into Formula One.

After one abortive attempt, on 8 February 1977, Williams Grand Prix Engineering was founded with Williams and Head taking seventy and thirty percent of the company respectively. In 1977 the team raced a customer March chassis but, in 1978 with backing from Saudi Airlines and having signed Australian driver Alan Jones, the Head-designed FW06 made its first appearance. Despite having no money and with Williams himself frequently forced to conduct business from a telephone box, Head still managed to design a respectable car.

In the 1980s Head began to move away from designing the cars himself, effectively creating a role of Technical Director, a person who oversaw the processes of design, construction, racing and testing, bringing together all the different disciplines.

F1 Italian GP 1981. Frank Williams, Frank Dernie and Patrick Head.

Frank Dernie took over as chief designer. During the 1980s he is also credited with many revolutionary concepts, including a six-wheeled car which tested in 1982 and continuously variable transmission, which replaced the car's conventional gearbox and allowed the engine to remain at optimum RPM during the entire lap. Neither system made it into racing due to rule changes, which many attribute to pressure from other teams, who were worried about the time required to develop similar systems of their own.

In 1990 Williams hired Adrian Newey, recently sacked as technical director of Leyton House Racing.

In a seven-year period, between 1991 and 1997, Williams had fifty-nine race wins, won five constructors titles and four different drivers won world championships. However, Newey also had ambitions to succeed to technical director, but this was blocked as Head was a founder and shareholder of the team. With Williams securing both the drivers and constructors titles in 1996, McLaren managed to lure Newey away though he was forced to take gardening leave for the 1997 season.

Since the departure of Newey, Williams often appeared a spent force, able to win occasionally, but unable to mount a consistent challenge.

Mr & Mrs Head at a luncheon in West Sussex on 13th July 2003.

In 2004, Head moved to the position of Director of Engineering, as Sam Michael became Technical Director.

San Marino GP, Patrick Head and Ayrton Senna in the Williams garage.

In April 2007 the Italian newspaper Gazzetta dello Sport reported that a court in Bologna had concluded that a technical failure was responsible for Ayrton Senna's fatal accident at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1994. Under Italian law, the responsibility for such an accident has to be proved but no action was taken against Head or Williams' Chief Designer Adrian Newey, neither of whom attended the court hearing. The court's findings were made public 13 years after the accident and the case was closed. The Italian Court of Appeal, on 13 April 2007, stated the following in the verdict numbered 15050: "it has been determined that the accident was caused by a steering column failure. This failure was caused by badly designed and badly executed modifications. The responsibility of this falls on Patrick Head, culpable of omitted control." Even being found responsible for Senna's accident, Head was not arrested because in Italy the statute of limitation for manslaughter is 7 years and 6 months and the final verdict was pronounced 13 years after the accident.

In 2012, Head resigned from his position in the Williams team.

London, UK. 29th January 2014. Patrick Head and his wife attend the Hall of Fame 2014 charity auction. Credit: Keith Larby / Alamy Live News.

He continued his involvement in Williams Hybrid Power Limited until it was sold to GKN in April 2014.

Natalie Pinkham is joined by former head of Cosworth F1 Mark Gallagher and Patrick Head to look back on the US Grand Prix in 2015.

In 2015, he received a Knighthood for his services to motorsport.

In March 2019, Head returned to Williams Racing for the first time in eight years. He returned in a consultancy role.

Patrick Head.

Many of the top engineers in Formula One - such as Adrian Newey, Neil Oatley, Ross Brawn, Frank Dernie, Paddy Lowe, Eghbal Hamidy, Geoff Willis and Enrique Scalabroni - have worked under Head's supervision early in their careers and all have moved on to senior positions within other teams. Brawn in particular has had success as Head's opposite number at Benetton, Ferrari, Brawn GP and Mercedes. Adrian Newey has also had success at McLaren and, more recently, Red Bull Racing and he is considered one of the most successful engineers in Formula One.

Williams’ top 10 moments in F1. Date published: May 21 2021. By Finley Crebolder.

With Williams celebrating their 750th grand prix, we have picked out some of the best moments from their time in Formula 1.

With a team that has such a rich history and has achieved so much, it is of course impossible to include every great moment, but here are 10 of the best…

Win number one

As the saying goes, you never forget your first…

Heading to Silverstone in 1979, Williams had only been around for two seasons but had started to impress, scoring one podium at the end of 1978 and two in the first half of the 1979 campaign. However, that first victory eluded them. If they could take it on home turf, it would be a real fairytale story.

They looked capable of doing so from the start of the weekend with Alan Jones taking pole position. In the race, things continued to go well with Jones staying in the lead and team-mate Clay Regazzoni sitting close behind him in P2.

That proved crucial as, when Jones retired with an engine issue with 30 laps to go, Regazzoni was ready and waiting to pick up the pieces and give the team their first ever victory.

It well and truly put the team on the map and signified the start of their enormous success as they went on to win races in each of the next eight seasons.

On top of the world

For an F1 team, winning your first race is big, but winning your first title double is even bigger – and that is just what Williams did in Montreal the following year.

With the Constructors’ Championship already secured, Jones entered the race a point behind Nelson Piquet with two rounds left. With the Brazilian taking pole by almost a second, Jones and Williams were very much the underdogs, but everything changed when Piquet retired from the lead with an engine issue on lap 24. Suddenly, the World Championship was within reach. All Jones had to do was win.

Doing so looked unlikely though, with the Australian struggling to hold off Didier Pironi after picking up damage at the start. However, the Frenchman was then given a one-minute time penalty for jumping the start, so Jones let him through and stayed close enough to take the win and the title.

What’s more, the other Williams driver, Carlos Reutemann, ended up finishing in P2 after some late chaos. A win, a 1-2 finish and the team’s first two titles in the bag. The perfect day.

Keke masters Monaco

Three years on, the team were not nearly as dominant, failing to score a podium in the first four races of the season. In round five though, they tasted victory again thanks to an absolutely stunning drive from Keke Rosberg in Monaco.

The Finn had been feeling ill all weekend and, with rain covering the streets of Monte Carlo, finishing the race seemed unlikely for him. Winning it, especially given he started in P5, was unthinkable. Despite not being in peak condition though, he opted to take a risk and start on slick tyres and it proved to be a masterstroke.

He flew off the line to move straight up to P2 and was leading by the end of Lap 1. After that, the only time he would be anywhere near another car was when he was lapping them. He was quite simply on another level to the rest of the grid.

With him crossing the line around 20 seconds clear of Piquet and lapping all but four cars, it was one of the most dominant displays ever seen at Monaco and still one of the team’s greatest victories.

Piquet vs Senna

There are many iconic images and clips from over the years featuring a Williams car and right up there with the best of them is Piquet passing Ayrton Senna in Budapest.

Driving for the team he had once been such big rivals with, Piquet was keen to prove he was still Brazil’s best and this was his chance to do so as he and his compatriot battled it out for the win.

He had already passed Senna twice but found himself trailing with 20 laps to go. He was not going to settle for P2 though. The double World Champion pulled out of the Lotus’ slipstream on the pits straight, dived through a near non-existent gap and flew around the outside of Turn 1, locking up but somehow keeping his car under control.

It proved to be the move that decided the race as he managed to stay ahead and take victory. To this day, few overtakes have been spoken about more.

The inter-team battle of Britain

Piquet was involved in another titanic battle the following year, this time with the other Williams driver, Nigel Mansell, as the two spent the British Grand Prix weekend in a league of their own.

The Brazilian took pole position ahead of his team-mate by just 0.07sec – nobody else was within a second of him – and, after Alain Prost had briefly passed both at the start, they got back ahead and pulled away from the rest of the field.

However, with both wanting to win and team orders not being issued, it was not going to be a relaxing race for Frank Williams by any means.

The pair set a blistering pace, quickly lapping the rest of the field, with Mansell staying close behind the leader. Disaster struck for the Briton though when he was forced to pit after reporting vibrations. Upon rejoining, he was around 30 seconds behind with 30 laps to go.

However, he closed the gap again and with just three laps remaining he pounced, making a move at Stowe and sending the home crowd wild as he took the lead and crossed the line just ahead of Piquet … and a long, long way ahead of everyone else.

The entire race weekend was a display of the team’s dominance over the rest of the field and, with a British driver winning, they had well and truly become a national treasure.

Mansell Mania

Patrick Head and Nigel Mansell.

For most drivers, a win such as that one in 1987 would be the best of their career, let alone clearly the best at that track. The fact that is not the case for Mansell shows just how dominant he and his team were in 1992.

He took pole at Silverstone by 1.9 seconds with a mind-blowing lap, with only one non-Williams car being within three seconds of him and crossed the line 40 seconds clear of the field on race day. He was simply excellent and driving an equally excellent car, shown by the fact his team-mate Ricciardo Patrese comfortably finished in P2.

What makes the race even more memorable is the scenes that followed afterwards, with ecstatic fans invading the track and mobbing him as he became statistically the most successful British driver ever.

Of all the iconic images associated with Williams, Mansell in a sea of fans trying to make his way to a transit van is right up there with the greatest.

At long, long last

Mansell won eight of the first 10 races that year. He was so dominant it was only a matter of time before he secured the title but, given how long he’d had to wait to become a World Champion, it was still a wonderful moment nonetheless. It came in Budapest and all he had to do was finish in the top three. Easy right? Wrong.

He dropped down to P4 at the start, got back into P3 five laps later, dropped back down to P4 after going wide and then ended up in P6 after having to pit due a slow puncture. With 15 laps to go, he had to make up three places to secure the title.

His life was made easier by the fact Michael Schumacher got stuck in the gravel and he made easy work of the others ahead of him, charging his way past Mika Hakkinen, Gerhard Berger and Martin Brundle to secure P2 behind Senna.

At the age of 39, Mansell had finally become World Champion, after finishing as runner-up on three occasions. Don’t you just love a happy ending?

Lumps in throats

In terms of raw emotion, few races compare to the 1996 season finale in Japan, in which Damon Hill finally became a World Champion in his last race with Williams.

It was going to be a great day for the team regardless as one of their drivers, Hill or Jacques Villeneuve, was guaranteed to win the title but, with it most likely being his final chance to ever do so, there was arguably more support for the former both within and outside of the team.

Everything fell into place for him on race day ultimately as, while he did not put a foot wrong, Villeneuve retired after losing a wheel, meaning Hill was to be the title winner regardless.

He became the sixth driver to become World Champion for Williams and his triumph was undoubtedly one of the most emotional, shown by Murray Walker’s commentary.

The showdown with Schumacher

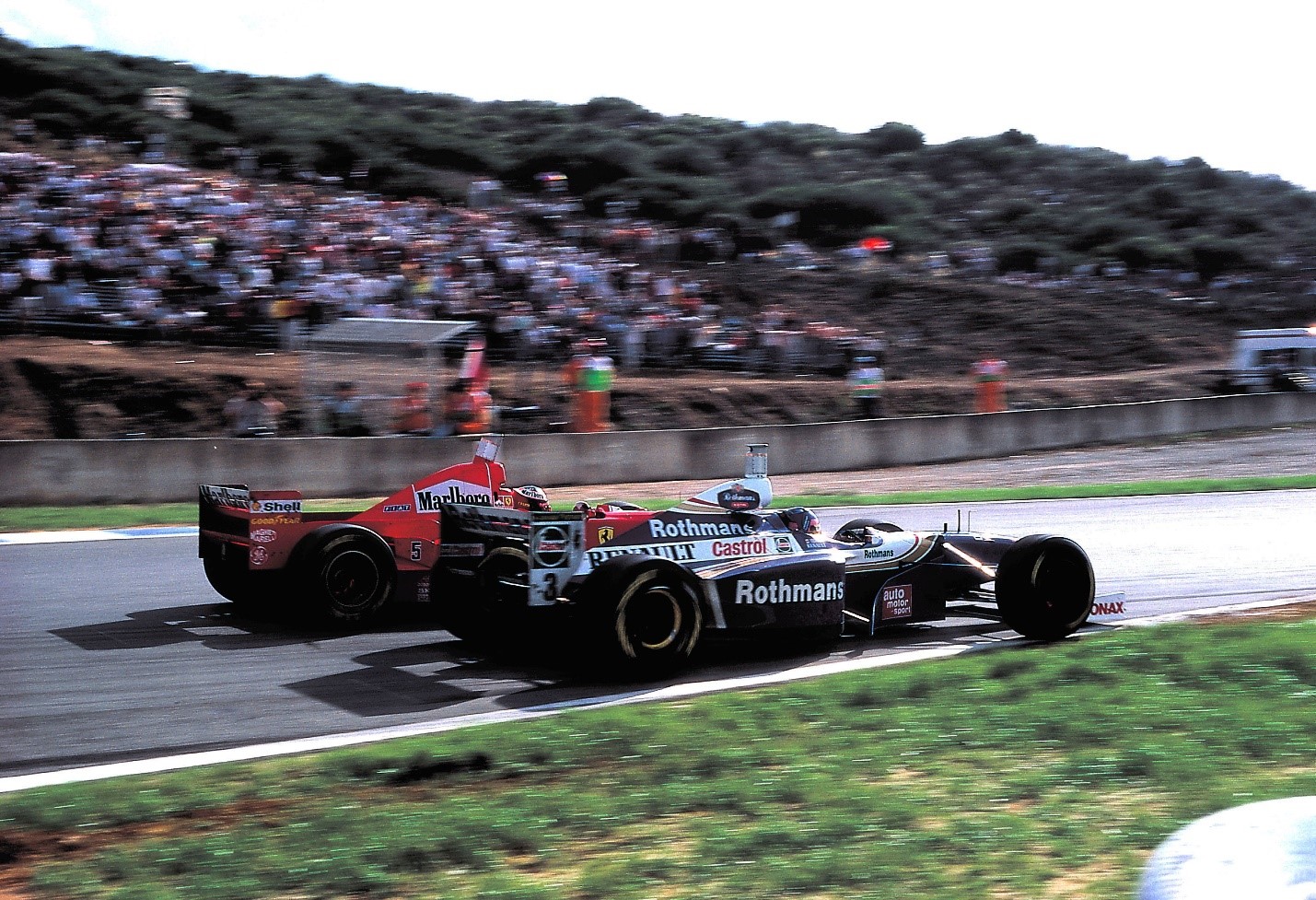

Hill’s triumph may have been one of the best emotionally for the team, but Villeneuve’s a year later was perhaps the most dramatic, ending with a final-race showdown with Michael Schumacher, the man who had stopped Hill and Williams from winning the title in 1994 with a hugely controversial move.

The Canadian was one point behind the German ahead of the race in Spain and there was nothing to choose between them that weekend from the off. Literally. They set the exact same time in qualifying, along with the other Williams of Heinz-Harald Frentzen.

Things proved to be equally as tight in the race as, after Schumacher took and held the lead for the first 40 laps, Villeneuve began to catch him and was less than a second behind by lap 48. He made his move and, like with Hill in 1994, Schumacher defended aggressively, hitting the Williams man and ruining his own race.

With damage, Villeneuve managed to hold on and finish P3 to secure the title, with the Ferrari man retiring and being disqualified from the championship. By also winning the Constructors’ Championship, Williams became the second most successful F1 team ever and have not enjoyed such success since that day.

Maldonado’s masterclass

While they did not win any titles, Williams did claim victory in plenty of races in the early 2000s, but that soon dried up as they went seven years without one. And then along came the Maldonator.

The team entered 2012 on the back of one of their worst seasons in history as they only scored a mere five points. They needed a lift more than ever and, at Barcelona, they got one.

With the team seemingly finding the perfect set-up, Maldonado looked rapid from the off and shocked the world by claiming P2 in qualifying but starting on pole following a penalty for Lewis Hamilton. Still, surely he would not win …

As expected, he lost the lead at the start with Fernando Alonso passing him, but had enough pace to stay close and pull off the undercut which ultimately gave him back the lead. He was flawless for the next 30 or so laps and crossed the line to win in one of the sport’s biggest ever shocks.

Frank Williams and the rest of the team were beside themselves with joy and the celebrations were truly heartwarming. It would prove to be the last victory for the team with the Williams family at the helm, which makes it a truly great moment in the team’s history.

Our highs and lows from Williams’s 750 F1 Grands Prix.

The Williams Formula 1 team celebrates 750 Grands Prix in Monaco this weekend – a stretch that has covered absolutely everything from dominant championship glory to tragedy and all points in between.

Objectively speaking, the titles won are the outright highs while the life-changing injuries suffered by team founder Frank Williams in 1986 and then the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994 are of course the lowest ebbs.

But a team with a history like this inspires a lot of emotions. To mark Williams’s latest milestone race, our writers reflect on their personal best and worst Williams moments from their time, both following it as F1 fans and covering it as journalists.

HIGH: Montoya shakes up F1. Matt Beer

By the early 2000s Williams was the insurgent underdog, its dominant eras a fading memory.

But, for a team in that role, the combination of a monster BMW engine and the monster raw talent of Juan Pablo Montoya was ideal.

While never realistically likely to beat Michael Schumacher and Ferrari to a championship (though it did come relatively close in 2003), the Montoya/Williams-BMW combination pretty much single-handedly provided entertainment in F1 across 2001/02, before Fernando Alonso/Renault and Kimi Raikkonen/McLaren got into a position to share that load in ’03.

Montoya was probably the last ‘classic Williams’ driver, embodying that spirit that Sir Frank loved so much. It was a shortlived relationship full of missed opportunities, but the highlights – mostly bold moves that got under Schumacher’s skin, but also wins of the calibre of that brilliant Monaco ’03 drive – were worth it.

LOW: PRE-SEASON 2019. Scott Mitchell

Williams’s failure to get its car ready for the start of pre-season testing in 2019 is the worst thing I’ve seen in professional motorsport.

Williams produced a car that was unfinished, awfully slow and illegal (parts had to be changed rapidly between testing and the first race).

Prior to that, the dubious dishonour of ‘worst thing I’ve ever seen’ was held by the Trulli Formula E team, which turned up to the first two races of the 2015/16 season without a working powertrain. A bizarre pantomime act was orchestrated whereby Trulli insisted it would be able to compete in Beijing and Putrajaya, to avoid breaching its contract by withdrawing, only to be denied entry because its car failed scrutineering each time.

But this was still in FE’s chaotic stage with a threadbare organisation led by an ex-F1 driver (hi Jarno!) who really, really didn’t look like he wanted to be involved anymore.

Williams’s 2019 shambles surpasses that for three reasons. First, it’s a much more serious operation. Second, there was no massive technical exercise that should’ve caught it out. Third, this is F1 – the pinnacle. What happened in pre-season 2019 was amateur-hour stuff.

It’s been a delight to see how much the team has recovered from that nadir, which is comfortably the lowest ebb I’ve ever seen a professional outfit at – and stands as Williams’s worst competitive moment in its glittering history.

HIGH: THE 1979 BREAKTHROUGH. Mark Hughes

I attended the 1979 British Grand Prix at Silverstone as a fan, drove my Hillman Avenger down from the north-east, very excited at the prospect of the insane speeds the new ground effect cars had been lapping Silverstone during testing – which was about six seconds faster than when the track had last hosted the raced two years before.

The Avenger may have been rusty, but what it had going for it was reclining velour seats. Because this was to be my bed for the weekend. Parked in a tree-secluded lay-by within walking distance of the track, driving down to Towcester in the evening and using the courtyard showers of a local hotel (50p for five minutes), just opposite Lord’s Hesketh estate, the workshops of which were no longer building F1 cars, but were still busy doing rebuilds on Cosworth DFVs for several F1 teams.

There were so many prospects to be excited about in the F1 of that summer. This was such a different season to those preceding it, ground effect was shifting the ground itself. A new competitive order was becoming apparent and even such proud old names as Lotus, Tyrrell and McLaren were at risk of being washed up by the new wave coming through.

Ligier had dominated the first two Grands Prix of the season and won another since. Renault’s crazy turbocharged gamble was beginning to pay off and, just two weeks before Silverstone, Jean-Pierre Jabouille had given the team its first win, almost unnoticed amid the dice-of-the-century just behind him for second place between Gilles Villeneuve and Rene Arnoux.

Then there was Williams, for so long just a backmarker name in F1, but no longer. It had begun looking serious with that beautiful little FW06 that Alan Jones had manhandled around the tracks in ’78, sometimes to thrilling – but so-far unfulfilled – effect.

Now the team had Patrick Head’s ground effect weapon, the FW07, it looked even more serious. Jones had led at Zolder in the car’s second race and Clay Regazzoni had taken a charging second in Monaco. Was it conceivable that Williams could win a Grand Prix? That was such a thrilling prospect.

To a later generation of fan Williams might be associated with crushing dominance in the ‘90s or mid-80s. At the time of that ’79 Silverstone weekend, it was an underdog with the thrilling potential of bursting the competitive establishment apart. It was even better that Regazzoni – at 39 years old and long after it looked like his frontline career was over – was along for the ride.

So we sat in the yellow seats at Woodcote and watched them practice, the summer crop on the infield adding hay fever to the fever of the event. We wandered up to Copse. The approach speed into there of Jones in the FW07 defied belief. He got braver and braver through there, the car ever-further out-of-line between turn-in and apex until, inevitably, he lost it, hit the banking hard.

Ground effect cars, we’d been led to believe, had to be cornered on rails. Not so, it seemed. There was a whole new territory to explore once a driver became attuned to the insane leap in grip. And Jones was ground effect’s Christopher Colombus.

Come qualifying the next day and Jones was even bolder. His final lap of 1m11.88s – car seemingly almost on top of the chicane before he braked – was a freeze-frame moment of history, when it became apparent that there was actually a whole new dimension of performance as ground effect was becoming aggressively exploited and that Lotus had just been tentatively nibbling at the edges of it in ’78 (Jones’ lap was 6.6s faster than James Hunt’s pole time from ’77). But that lap also made the scale of Williams’ challenge to the establishment crystal clear.

Two years earlier, the last Grand Prix Silverstone had hosted, Williams qualified its customer car March 26th. Now this. That’s how suddenly it came after years on the margins. Frank Williams later recalled other team personnel up and down the pitwall looking across at them, almost mouths agape. It actually felt that way in the split-second moment of that laptime being announced, from up in the Woodcote yellow seats. It put Jones on pole by 0.6s.

Surely, he’d be unbeatable on race day. Actually, not so. A dodgy weld on a water pump lost him what would have been a pulverising victory. But … here was good old Regazzoni – with the non-works DFV prepared by Hesketh and therefore not having the latest water pump – doing the perfect back-up job and delivering Williams’ first Grand Prix victory. It was to be his last, so poignantly bridging the eras.

We’d no idea where this crazy wind was about to take F1, what with turbos and ground effect coming along all in a hurricane hurry and bursting open the performance bottleneck. But boy was it going to be exciting – and Williams was for sure going to be right in the centre of it all.

During the drive home in the Avenger that summer evening we talked and knew we’d seen something special, something significant.

LOW: Adelaide 1994. Glenn Freeman

The combination of Williams and Damon Hill didn’t deserve the world championship more than Michael Schumacher/Benetton in pure sporting terms – putting all unproven suspicions about Benetton that year to one side.

But with everything that Williams went through in 1994, it would have made for an incredible fairytale ending if Hill won the title even Schumacher declared would have been Senna’s if he’d survived after Imola.

The championship being decided by Schumacher taking Hill out, rather than just a case of the best man winning on the day, made the defeat all the more painful.

It’s no surprise Williams didn’t want the post-season fuss of a protest. By then everyone just wanted to forget 1994.

HIGH: Brands Hatch 1986. Sam Smith

It’s quite difficult to adequately describe just how fast Nelson Piquet’s Williams FW11 approached Paddock Hill Bend on his pole lap in July 1986.

Such was the constant pull of its grenade-like Honda RA166-E that a miasma of black smoke added to the truly alarming sight of Piquet cresting the dip into the braking area on his all-or-nothing qualifying lap.

This slight haze was caused by toluene deposits in the special Mobil 1 fuel used by Williams-Honda at the time. It was derived from a tar-process residue which added a bonkers chemistry-set buzz to what is believed to have been around 1150 bhp qualifying power available to Nigel Mansell and Piquet in qualifying trim.

As an 11-year-old, I crouched with my dad at Paddock and, amid the scaffolding beneath it – which gave a ground-level view, we waited for Piquet.

Such was the sight of the FW11 barrelling into the right-hander that, for a fleeting moment, the old man grabbed me by the scruff of the neck ready to throw me out of the way as he believed Piquet’s throttle had stuck open and he was heading straight for us.

In the blink of an eye and a shower of sparks he twitched through the corner up to Druids before completing a mesmerising lap of 1m06.961s, 0.4s faster than team-mate Mansell.

The race has been well documented as Mansell went from driveshaft disaster to second-chance hero, thanks to Jacques Laffite’s tibia-shattering accident against the callous railway sleepers at Paddock.

This was peak Williams. A demonstration of complete superiority with Mansell and Piquet making it a race between them and them only.

The gap to third-placed Alain Prost’s McLaren at the end of the 75-lap race was almost two minutes and Mansell’s fastest race lap was almost 1.3s faster than the McLaren-TAG Porsche.

With Mansell then leading Prost in the title and Williams 16 points ahead of McLaren in the constructors’ cup, the Didcot decimation of its opposition would be absolute, or at least so it seemed on that unforgettable sultry summer afternoon in Kent.

A HIGH AND A LOW: SPAIN 2012. Edd Straw.

Pastor Maldonado’s win in the 2012 Spanish Grand Prix was a rollercoaster of emotions for the Williams team, hence it stands both as the best and worst memory of the great team for me.

As a fan of Damon Hill, in particular in my youth, it’s tempting to pick something from that era but, having the privilege to be at the 2012 Spanish GP to cover that unlikely victory and witness what unfolded after the race, gives it the edge.

Maldonado’s victory puzzles many to this day, but the various elements that led to it were clear. Lewis Hamilton losing pole position because he had insufficient fuel to provide a post-session sample promoted Maldonado to the front row. From there, he was able to undercut his way past Fernando Alonso’s Ferrari and hold on to take arguably the most unlikely triumph of 21st century Grand Prix racing.

Many factors were at play. Firstly, Maldonado was a driver capable of a searing turn of speed on occasion and it was clear that, if the stars aligned for him, he could do something like this. It just seemed unlikely the stars ever would align so spectacularly!

Secondly, the Williams-Renault FW34 was an extremely good car, far better than its patchy results and frankly criminal eighth in the constructors’ championship suggested. You just need to look at some of Maldonado’s other occasional stellar qualifying laps to see that – although Bruno Senna in the other car, while effective in the races, struggled badly to get his head round the tyres for a single lap.

Thirdly, this was a period of what became known as the ‘tyre lottery’. That doesn’t mean Williams had magic sets of tyres, simply that the FW34 happened to work the capricious Pirelli extremely well that weekend. The team had also put a huge amount of work into the tyre science, but having the tyres so well in the performance window was a major contributing factor.

The conspiracy-theory-minded suggest there was some trickery at play, occasionally citing the fact it was team founder Frank Williams’s 70th birthday. But, while it’s true there was a celebration of this on that weekend, his birthday had actually happened almost a month earlier. Instead, it was a web of myriad contributory factors coming together. Unlikely, yes. Impossible? No.

Even so, it was a surprise to see Maldonado execute the race so well, especially after losing the lead at the start. Improbably, he got the lead back and this famously error-prone driver did not put a foot wrong under pressure from Alonso.

This was that rare thing, a Maldonado weekend close to perfection – and the timing was perfect. Given it seemed Williams might never win again, to witness the venerable team’s 114th win – over seven years since the last – was a privilege.

But things took a darker turn after the race. A mishap while draining the fuel from Senna’s car in the garage post race led to fuel vapour in the feed pipe igniting, which then almost instantly made its way to the refuelling rig. This sent a burst of flames into the garage, which at the time was full of team personnel being given a talking to by Frank Williams himself.

Witnessing that unfold from the Williams motorhome, which had the live TV coverage of the fire on every screen, was unforgettable, with team personnel powerless to help and with no idea whether everyone had been able to get out safely. That tense uncertainty is familiar when a serious accident occurs, but nobody expects it to happen after the race.

Thankfully, everyone escaped and the Williams team – as well as those from rival teams – managed to get the flames under control. At one stage, it seemed a distinct possibility that the conflagration might spread and consume the entire building …

The image of the victorious Maldonado carrying 12-year-old cousin Manuel Maldonado – today a racing driver in his own right – from the smoke became iconic.

LOW: The family’s departure. Rob Hansford

While it was ultimately the right decision in order for the Williams name to continue in Formula 1, it was extremely sad to see the family sell their beloved team and depart from the series completely.

It’s not just the team that has been a staple of F1 for so many years, but so too has Sir Frank Williams. Of course, he wasn’t as hands-on during the last few years of his reign, but it was still his team, his creation, meaning Williams was the only true old school privateer team on the grid.

Seeing him and the rest of the family leaving while the team was confined to the back of the grid and stuck in an uncompetitive state was not how their wonderful history with it should have concluded.

HIGH: JEREZ 1997. Glenn Freeman

While this is chosen for personal reasons that will be familiar to listeners of our Bring Back V10s podcast, its significance in the Williams story has grown over time given it remains the team’s final world championship.

The race is remembered for the Jacques Villeneuve/Michael Schumacher collision that decided the world championship and the bizarre Williams/McLaren agreement that resulted in Villeneuve giving up his last chance to win an F1 race. It was also the beginning of a Williams drought that stretched all the way to Ralf Schumacher’s victory in the San Marino Grand Prix early in 2001.

Before all of the shenanigans, the straight fight between Schumacher and Villeneuve was one of the best we’ve ever seen in a title decider.

Williams has never reached the heights of its Renault-powered era since and, with the French manufacturer leaving after Jerez, the end of 1997 marked the curtain coming down on the team’s 1990s purple patch.

LOW: 1988. Sam Smith

Barely 12 months after the Brands domination I’ve relived above, Williams had lost Honda engines to McLaren and Piquet to a fat-cheque-beckoning Lotus.

Yet it still had Mansell and the vast majority of the team that had created the FW11 and FW11B race winners and, for Piquet in 1987, a title-winning package.

The dawn of the atmospheric era was upon F1 and Williams chose to reconnect with John Judd after he had been an integral engineering ally in the old Cosworth DFV days.

Now set up on his own, Judd provided his new ‘CV engine’ while Williams pursued its ‘reactive suspension’ system with a young Paddy Lowe involved in one of his first big racing projects.

In truth, 1988 was always going to be a stop-gap until Renault came in for ’89 but what started out in testing with great promise soon crumbled into a horrible litany of poor reliability.

Engine issues, confused feel for drivers of the suspension and a demotivated and Ferrari-bound Mansell conspired to produce a miserly 20 points from 16 races.

It had all started so well with Mansell a heroic second on the grid at Rio, but a soggy Silverstone apart – when Mansell reverted to a conventionally sprung FW12 and netted a hard-fought second – the season was a debacle, reaching a nadir at Monza when Riccardo Patrese was 3.5s off Prost’s pole and an F1 cameo making Jean-Louis Schlesser was an eye-watering 5.6s off the pace!

The FW12 was not a complete disaster but, in the context of what had come before from 1985-1987, Mansell and Patrese finishing in the top six on just seven occasions between them was a paltry return for a team of Williams’s stature in the decade that established its legend.

HIGH: AN F1 TEAM RUNNING LAGUNAS. Scott Mitchell.

My best Williams memory is my first one. And, a little awkwardly given the milestone we’re celebrating here, it’s not from one of its 749 prior grand Prix Starts. But it did play a part in me understanding the scope of Williams’s success.

Time tends to make a mockery of such memories so I don’t know when this would’ve been, but my dad brought back BTCC season review video tapes from 1994-1998 and I binge-watched them. All I know is I watched those seasons on delay by a few years!

The blue-and-yellow Williams Renault Laguna from the 1995 British Touring Car Championship must be among my first ‘favourite cars’. It was quickly replaced by the yellow-and-blue Lagunas from ’96 and ’97! Learning that the Renault BTCC team/cars were run by Williams F1 made it sound so BIG. Like the others didn’t stand a chance.

I’m pretty confident I had no idea what Williams was before falling in love with those Lagunas. I’d have paid little attention to F1 before I started karting myself in 2002, by which point Williams would have been sniping at Ferrari in its BMW era – but a few years past its peak.

So my first association with Williams was as a slightly mythical, giant operation that built/ran my favourite cars.

By the time F1 itself actually mattered to me and I started following some of those 749 Grands Prix, Williams wasn’t nearly as successful as it had been previously.

But, as an organization, it had already had a pretty big impact on my early life as a racing fan.

LOW: Zanardi’s failure. Matt Beer

Having spent 1996-98 mostly cheering for Jacques Villeneuve + Williams in F1 and Alex Zanardi + Ganassi in CART (with a side order of cheering for Greg Moore in CART too, doing some A levels and making it into pubs), I naturally liked the concept of Zanardi + Williams in F1.

Alessandro Zanardi.

But as much as I, frankly, worshipped Zanardi in those years, I wouldn’t say I was absolutely convinced it would be a success. With Renault’s works support gone, Williams was waning by the time Zanardi arrived for 1999. I hated the narrow cars/grooved tyre F1 rules and had a feeling Zanardi might too. A string of evocative David Tremayne articles in Autosport through ’98 swayed me into believing that Zanardi’s combination of technical intuition and racing spirit would revitalise Williams and bring wheel-to-wheel entertainment back to F1. But it was still more hope than expectation.

I still never imagined that it would be as bad as it was. Zero points. Perhaps even worse, zero moments where Zanardi looked anywhere near as enthralling as he had in America. Floundering so desperately he was swapping carbon brakes for steel ones trying to find some kind of affinity with the car. Sacked at the end of the year in favour of Jenson Button.

Zanardi + Ganassi + mid-90s CART rules was a perfect right person, right package, right time combination that created beautiful magic. Zanardi + Williams + late-90s F1 rules was the painful opposite.

HIGH: HILL’S 1996 TITLE. Rob Hansford

For me, seeing Damon Hill win the 1996 world championship was the ultimate Williams high point.

They’d had to endure a bitter battle with Schumacher and Benetton for the two seasons prior and they came off second best both times. And, while Schumacher was clearly the fastest driver in 1995, the nature of the ’94 defeat was painful.

But in 1996 Williams hit perfection in a similar manner to 1992 and completely controlled the season.

It won the constructors’ title by 105 points and, while it successfully defended that crown in 1997, it was in a far less comfortable fashion.

Williams never dominated in that manner again after ’96. In my mind it was the last true major achievement for Williams and the image of Hill crossing the finish line at Suzuka to clinch his one and only world championship title is still etched vividly in my mind to this day.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment