The taste of danger, the terrestrial limit of the passion. Who won here won twice as he wasn’t dead. Nestled in dense forests of Western Germany it’s the most legendary, arduous and dangerous automobile racetrack of the world, the Nürburgring.

Seductive cocktail between man, car and nature, is characterised by one of the worst climates we will find on a circuit.

Jackie Stewart followed by Graham Hill at Nurburgring.

"I was always relieved when it was time to leave ... The only time you felt comfortable thinking about the Ring was when you were very far away, huddled in the house in front of the fire on a winter evening. I never did one more fast lap than absolutely necessary." Jackie Stewart

In the photo the 1976 edition, with the smoke behind the trees coming from Lauda's burning car.

"At the Nurburgring you have to drive overcoming every instinctive fear or common sense. Everyone says it is their favorite circuit, but they say it in front of the fireplace at home. 20 terrifying kilometers of madness, The car kept coming off the ground. Every Sunday afternoon after the race in the Ring, I told myself that I would never go back there." Jackie Stewart

Considered the greatest and most challenging circuit ever devised, the original Nurburgring (permanent road course: 22.835 km (1967-76 version)) – infamously nicknamed the “Green Hell” by Jackie Stewart – was a 160-turn behemoth that wound its way through the Eiffel Mountains of western Germany.

24h Nuerburgring 2012 girls.

The Nordschleife takes the cake as far as epic old school tracks go … an incredibly high speed roller-coaster ride. 15 miles of pure folly. As soon as you leave the circuit where Formula 1 ran and enter Nordschleife’s amazing world, you feel teleported in another place. Kerbs rise and become untouchable, the street becomes narrow and trees, grass and guard rail appear, asphalt constantly changes colour and adhesion level as well. It starts quite an adventure, with slope changes, jumps and hollows. Your breathing slams to a stop, the stomach gets tight. It’s difficult to be surprised in seeing Augusto Farfus, after near a decade from his first 24 hours of Nürburgring, still crossing himself whenever he starts a new lap. There was a version of the Nurburgring that included the Sudschleife (South Loop) that brought the total length to 28km. This was pre-war grand prix racing. Cars racing out in the countryside on a beautifully smooth piece of track, and nothing but fields and farm land in the distance. No spectators anywhere. Totally surreal.

Lauda crashed in his Ferrari coming out of the left-hand kink before Bergwerk, for causes that were never established. He was badly burned as his car was still loaded with fuel in lap 2. Lauda was saved by the combined actions of fellow drivers Arturo Merzario, Guy Edwards, Brett Lunger, and Harald Ertl, rather than by the ill-equipped track marshals. Today the Austrian says: “a kid today doesn’t know anything or not very much of what happened in that 1976. A kid today in the ‘70s wasn’t even born. If you can’t understand that era you cannot appreciate what we were doing. We were risking our life every day. Have you seen the new circuit? Have you been through doing a lap of the old one instead? (the old circuit is the Nordschleife, the 23 Km of hell and turns where Lauda was about to die). There are differences that go beyond the circuit. The old track was pure risk. And that risk was what we had to face on a daily basis. Today that track, and I say thanks God, is much safer, and represents what Formula 1 became today. Today you can have an accident and nothing happens. Then, instead, you died. But, believe me, the real difference it’s not even exactly that. Even today on the track anything can happen. The problem is that it would be a bump. Then it was normal: we had to continuously face with the probability of dying somehow. It was almost all we could think about. That idea is the actual difference. You say that modern drivers are risk employees? I don’t know. But I think that if you don’t have such idea in mind, as due to Formula 1 progress you don’t need it, then everything changes: it’s useless to expect a modern Formula 1 driver to have the same character of me or James Hunt, because it’s just impossible as it all changed. But of course a Formula 1 like the modern one seems fascinating to me, I would turn towards such a sport, as if I’d have competed now I’d have made ten times that and above all I would still have my ear.”

Nürburgring is a 150,000-capacity motorsports complex located in the town of Nürburg, Germany. It features a Grand Prix race track built in 1984, and a much longer old "North loop" track which was built in the 1920s around the village and medieval castle of Nürburg. The north loop is 20.8 km (12.9 mi) long and has more than 300 metres (1,000 feet) of elevation change from its lowest to highest points.

Nurburgring, road, woods, cars.

Originally, the track featured four configurations: the 28.265 km (17.563 mi)-long Gesamtstrecke ("Whole Course"), which in turn consisted of the 22.810 km (14.173 mi) Nordschleife ('North Loop') and the 7.747 km (4.814 mi) Südschleife ('South Loop'). There also was a 2.281 km (1.417 mi) warm-up loop called Zielschleife ('Finish Loop') or Betonschleife ('Concrete Loop'), around the pit area. Between 1982 and 1983 the start/finish area was demolished to create a new GP-Strecke, and this is used for all major and international racing events. However, the shortened Nordschleife is still in use for racing, testing and public access. In the early 1920s, ADAC Eifelrennen races were held on public roads in the Eifel mountains. This was soon recognised as impractical and dangerous. The construction of a dedicated race track was proposed, following the examples of Italy's Monza and Targa Florio courses, and Berlin's AVUS, yet with a different character. The layout of the circuit in the mountains was similar to the Targa Florio event, one of the most important motor races at that time. The original Nürburgring was to be a showcase for German automotive engineering and racing talent. Construction of the track, designed by the Eichler Architekturbüro from Ravensburg (led by architect Gustav Eichler), began in September 1925. The track was completed in spring of 1927. In 1929 the full Nürburgring was used for the last time in major racing events, as future Grands Prix would be held only on the Nordschleife. Motorcycles and minor races primarily used the shorter and safer Südschleife. Memorable pre-war races at the circuit featured the talents of early Ringmeister (Ringmasters) such as Rudolf Caracciola, Tazio Nuvolari and Bernd Rosemeyer.

Nurburgring, Nordscheife.

After World War II, racing resumed in 1947 and in 1951, the Nordschleife of the Nürburgring again became the main venue for the German Grand Prix as part of the Formula One World Championship (with the exception of 1959, when it was held on the AVUS in Berlin). A new group of Ringmeister arose to dominate the race – Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio, Stirling Moss, Jim Clark, John Surtees, Jackie Stewart and Jacky Ickx. By the late 1960s, the Nordschleife and many other tracks were becoming increasingly dangerous for the latest generation of F1 cars.

Nurburgring 1967.

In 1967, a chicane was added before the start/finish straight, called Hohenrain, in order to reduce speeds at the pit lane entry. This made the track 25 m (82 ft) longer. Even this change, however, was not enough to keep Stewart from nicknaming it 'The Green Hell' following his victory in the 1968 German Grand Prix amid a driving rainstorm and thick fog. In 1970, after the fatal crash of Piers Courage at Zandvoort, the F1 drivers decided at the French Grand Prix to boycott the Nürburgring unless major changes were made, as they did at Spa the year before. The changes were not possible on short notice, and the German GP was moved to the Hockenheimring, which had already been modified. In accordance with the demands of the F1 drivers the Nordschleife was reconstructed by taking out some bumps, smoothing out some sudden jumps (particularly at Brünnchen), and installing Armco safety barriers. The track was made straighter, following the race line, which reduced the number of corners. The German GP could be hosted at the Nürburgring again, and was for another six years from 1971 to 1976.

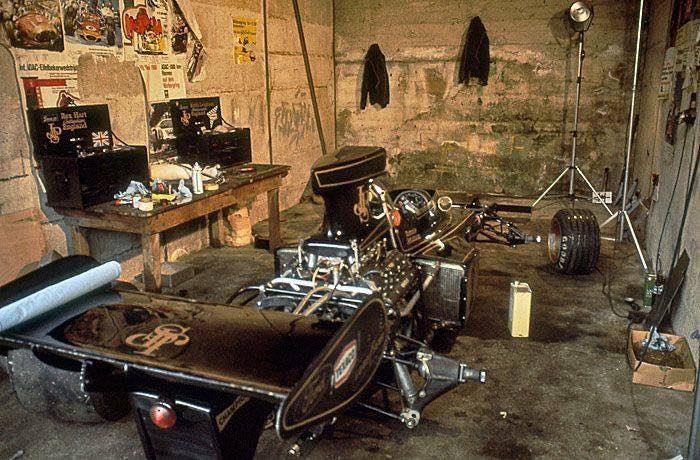

Lotus pit box at the Nurburgring in 1973.

In 1973 the entrance into the dangerous and bumpy Kallenhard corner was made slower by adding another left-hand corner after the fast Metzgesfeld sweeping corner. Safety was improved again later on, e.g. by removing the jumps on the long main straight and widening it, and taking away the bushes right next to the track at the main straight, which made that section of the Nürburgring dangerously narrow. Later on it was decided that the 1976 race would be the last to be held on the old circuit. The old Nürburgring never hosted another F1 race again, as the German Grand Prix was moved to the Hockenheimring for 1977. By its very nature, the Nordschleife was impossible to make safe in its old configuration. It soon became apparent that it would have to be completely overhauled if there was any prospect of Formula One returning there. With this in mind, in 1981 work began on a 4.5 km (2.8 mi)-long new circuit, which was built on and around the old pit area.

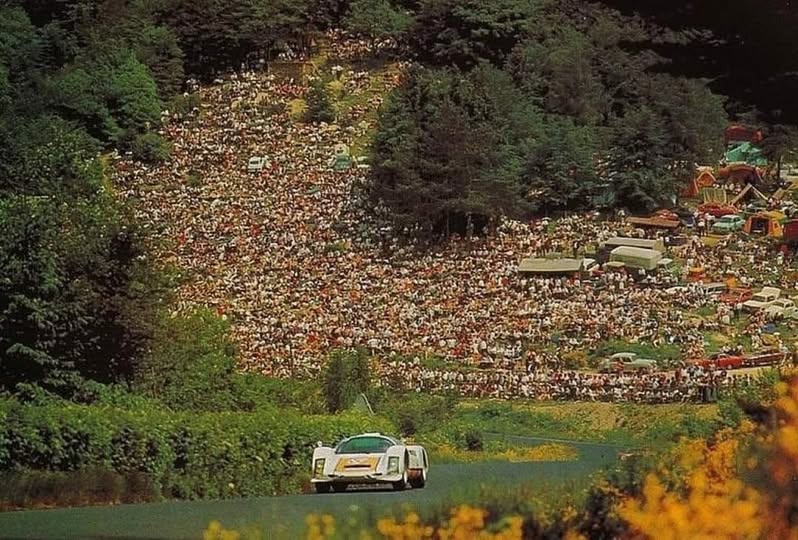

Gorgeous crowd at the Nurburgring 1000 km in 1966.

At the same time, a bypass shortened the Nordschleife to 20,832 m (12.944 mi), and with an additional small pit lane, this version was used for races in 1983, e.g. the 1000 km Nürburgring endurance race, while construction work was going on nearby. Meanwhile, more run-off areas were added at corners like Aremberg and Brünnchen, where originally there were just embankments protected by Armco barriers. The track surface was made safer in some spots where there had been nasty bumps and jumps. Racing line markers were added to the corners all around the track as well. Also, bushes and hedges at the edges of corners were taken out and replaced with Armco and grass. The former Südschleife had not been modified in 1970/71 and was abandoned a few years later in favour of the improved Nordschleife. It is now mostly gone (in part due to the construction of the new circuit) or converted to a normal public road, but since 2005 a vintage car event has been hosted on the old track layout, including part of the parking area. The new track was completed in 1984 and named GP-Strecke (German: Großer Preis-Strecke: literally, 'Grand Prix Course'). It was built to meet the highest safety standards. However, it was considered in character a mere shadow of its older sibling. Some fans, who had to sit much farther away from the track, called it Eifelring, Ersatzring, Grünering or similar nicknames, believing it did not deserve to be called Nürburgring. Like many circuits of the time, it offered few overtaking opportunities. Prior to the 2013 German Grand Prix both Mark Webber and Lewis Hamilton said they like the track. Webber described the layout as "an old school track" before adding, "it’s a beautiful little circuit for us to still drive on so I think all the guys enjoy driving here." While Hamilton said: "it’s a fantastic circuit, one of the classics and it hasn’t lost that feel of an old classic circuit." To celebrate its opening, an exhibition race was held, on 12 May, featuring an array of notable drivers. Driving identical Mercedes 190E 2.3–16's, the line-up was Elio de Angelis, Jack Brabham (Formula 1 World Champion 1959, 1960, 1966), Phil Hill (1961), Denis Hulme (1967), James Hunt (1976), Alan Jones (1980), Jacques Laffite, Niki Lauda (1975, 1977), Stirling Moss, Alain Prost, Carlos Reutemann, Keke Rosberg (1982), Jody Scheckter (1979), Ayrton Senna, John Surtees (1964) and John Watson. Senna won ahead of Lauda, Reutemann, Rosberg, Watson, Hulme and Jody Scheckter, being the only one to resist Lauda's overwhelming performance who – having missed the qualifying – had to start from the last row and overtook all the others except Senna. Besides other major international events, the Nürburgring has seen the brief return of Formula One racing, as the 1984 European Grand Prix was held at the track, followed by the 1985 German Grand Prix. Following the success and first world championship of Michael Schumacher, a second German F1 race was held at the Nürburgring between 1995 and 2006, called the European Grand Prix, or in 1997 and 1998, the Luxembourg Grand Prix. For 2002, the track was changed, by replacing the former "Castrol-chicane" at the end of the start/finish straight with a sharp right-hander (nicknamed 'Haug-Hook'), in order to create an overtaking opportunity. Also, a slow Omega-shaped section was inserted, on the site of the former kart track. This extended the GP track from 4,500 to 5,200 m (2.80 to 3.23 mi), while at the same time, the Hockenheimring was shortened from 6,800 to 4,500 m (4.23 to 2.80 mi). Starting with the 2007 Formula One season, Hockenheim and Nürburgring will alternate for hosting of the German GP. While it is unusual for deaths to occur during sanctioned races, there are many accidents and several deaths each year during public sessions. It is common for the track to be closed several times a day for cleanup, repair, and medical intervention. While track management does not publish any official figures, several regular visitors to the track have used police reports to estimate the number of fatalities at somewhere between 3 and 12 in a full year. Jeremy Clarkson noted in Top Gear in 2004 that "over the years this track has claimed over 200 lives." The Nordschleife was formerly known for its abundance of sharp crests, causing fast-moving, firmly-sprung racing cars to jump clear off the track surface at many locations. Although by no means the most fearsome, Flugplatz is perhaps the most aptly (although coincidentally) named and widely remembered. The name of this part of the track comes from a small airfield, which in the early years was located close to the track in this area. The track features a very short straight that climbs sharply uphill for a short time, then suddenly drops slightly downhill, and this is immediately followed by two very fast right-hand kinks. The Flugplatz is one of the most important parts of the Nürburgring because after the two very fast right handers comes what is possibly the fastest part of the track: a downhill straight called Kottenborn, into a very fast curve called Schwedenkreuz (Swedish Cross).

Grid girls.

Drivers are flat for some time here. Right before Flugplatz is Quiddelbacher-Höhe (peak, as in "mountain summit"), where the track crosses a bridge over the Bundesstraße 257. The Fuchsröhre is soon after the very fast downhill section succeeding the Flugplatz. After negotiating a long right hand corner called Aremberg (which is after Schwedenkreuz) the road goes slightly uphill, under a bridge and then it plunges downhill, and the road switches back left and right and finding a point of reference for the racing line is difficult. This whole sequence is flat out and then, the road climbs sharply uphill. The road then turns left and levels out at the same time; this is one of the many jumps of the Nürburgring where the car goes airborne. This leads to the Adenauer Forst (forest) turns. The Fuchsröhre is one of the fastest and most dangerous parts of the Nürburgring because of the extremely high speeds in such a tight and confined place; this part of the Nürburgring goes right through a forest and there is only about 7–8 feet of grass separating the track from Armco barrier, and beyond the barriers is a wall of trees. Perhaps the most notorious corner on the long circuit, Bergwerk has been responsible for some serious and sometimes fatal accidents. A tight right-hand corner, coming just after a long, fast section and a left-hand kink on a small crest, was where Carel Godin de Beaufort fatally crashed. The fast kink was also the scene of Niki Lauda's infamous fiery accident during the 1976 German Grand Prix. This left kink is often referred to as the Lauda Links (Lauda left). The Bergwerk, along with the Breidscheid/Adenauer Bridge corners before it, are one of the series of corners that make or break one's lap time around the Nürburgring because of the fast, lengthy uphill section called Kesselchen (Little Valley) that comes after the Bergwerk. Although being one of the slower corners on the Nordschleife, the Karussell is perhaps its most famous and one of its most iconic- it is one of two berm-style, banked corners on the track. Soon after the driver has negotiated the long uphill section after Bergwerk and gone through a section called Klostertal (Monastery Valley), the driver turns right through a long hairpin, past an abandoned section called Steilstrecke (Steep Route) and then goes up another hill towards the Karrusell. The entrance to the corner is blind, although Juan Manuel Fangio is reputed to have advised a young driver to "aim for the tallest tree". Once the driver has reached the top of the hill, the road then becomes sharply banked on one side and level on the other- this banking drops off, rather than climbing up like most bankings on circuits. The sharply banked side has a concrete surface, and there is a foot-wide tarmac surface on the bottom of the banking for cars to get extra grip through the very rough concrete banking. Cars drop into the concrete banking, and keep the car in the corner (which is 210 degrees, much like a hairpin bend) until the road levels out and the concrete surface becomes tarmac again. This corner is very hard on the driver's wrists and hands because of the prolonged bumpy cornering the driver must do while in the Karrusell. Usually cars come out of the top of the end of the banking to hit the apex that comes right after the end of the Karrusell. The combination of a recognisable corner, slow-moving cars, and the variation in viewing angle as cars rotate around the banking, means that this is one of the circuit's most popular locations for photographers. It is named after German pre-WWII racing driver Rudolf Caracciola, who reportedly made the corner his own by hooking the inside tires into a drainage ditch to help his car "hug" the curve. As more concrete was uncovered and more competitors copied him, the trend took hold. At a later reconstruction, the corner was remade with real concrete banking, as it remains to this day. Shortly after the Karussell is a steep section, with gradients in excess of 16%, leading to a right-hander called Hohe Acht, which is some 300 m higher in altitude than Breidscheid. A favourite spectator vantage point, the Brünnchen section is composed of two right-hand corners and a very short straight. The first corner goes sharply downhill and the next, after the very short downhill straight, goes uphill slightly. This is a section of the track where on public days, accidents happen particularly at the blind uphill right-hand corner. Like almost every corner at the Nürburgring, both right-handers are blind. The short straight used to have a steep and sudden drop-off that caused cars to take off and a bridge that went over a pathway; these were taken out and smoothed over when the circuit was rebuilt in 1970 and 1971. The Pflanzgarten, which is soon after the Brünnchen, is one of the fastest, trickiest and most difficult sections of the Nürburgring. It is full of jumps, including two huge ones, one of which is called Sprunghügel (Hill Jump). This very complex section is unique in that it is made up of two different sections; getting the entire Pflanzgarten right is crucial to a good lap time around the Nürburgring. Pflanzgarten 1 is made up of a slightly banked, downhill left hander which then suddenly switches back left, then right. Then immediately, giving the driver nearly no time to react (knowledge of this section is key) the road drops away twice: the first jump is only slight, then right after (somewhat like a staircase) the road drops away very sharply which usually causes almost all cars to go airborne at this jump; the drop is so sudden. Then, immediately after the road levels out very shortly after the jump and the car touches the ground again, the road immediately and suddenly goes right very quickly and then right again; this is what makes up the end of the first Pflanzgarten- a very fast multiple apex sequence of right hand corners.

Grid girls.

The road then goes slightly uphill and then through another jump; the road suddenly drops away and levels out and at the same time, the road turns through a flat-out left hander. Then, the road drops away again very suddenly, which is the second huge jump of the Pflanzgarten known as the Sprunghügel. The road then goes downhill then quickly levels out, then it goes through a flat-out right hander and this starts the Stefan Bellof S, which was known as Pflanzgarten 2 prior to 2013.

A grid girl at the Endurance 24 hours of the Nurburgring in 2014.

The Stefan Bellof S is very tricky because the road quickly switches back left and right—a car is going so fast through here that it is like walking on a tightrope. It is very difficult to find the racing line here because the curves come up so quickly, so it is hard to find any point of reference. Then, after a jump at the end of the switchback section, it goes through a flat-out, top gear right hander and into a short straight that leads into two very fast curves called the Schwalbenschwanz (Swallow's Tail). The room for error on every part of the consistently high-speed Pflanzgarten and the Stefan Bellof S is virtually non-existent (much like the entire track itself)—this is why it is such a difficult part of the circuit.

Grid girls 24h Nuerburgring 2017.

The road and the surface of the Pflanzgarten and the Stefan Bellof S moves around unpredictably; knowledge of this section is key to getting through cleanly. The Schwalbenschwanz is a sequence of very fast sweepers located after the Stefan Bellof S. After a short straight, there is a very fast right hand sweeper that progressively goes uphill, and this leads into a blind left-hander that is a bit slower. The apex is completely blind, and the corner then changes gradient a bit; it goes up then down, which leads into a short straight that ends at the Kleines Karussell. Originally, this part had a bridge that went over a stream and it was very bumpy; this bridge was taken out and replaced with a culvert (large industrial pipe) so that the road could be smoothed over. The Kleines Karussell is similar to its bigger brother, except that it is a 90 degree corner instead of 210 degrees, and is faster and slightly less banked. Once this part of the track is dealt with, the drivers are near the end of the lap; with two more corners to negotiate before the 2.135 km long Döttinger Höhe straight.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment