The golden era of racing, when men were men and everything was simultaneously much more and far less tacky than it is now.

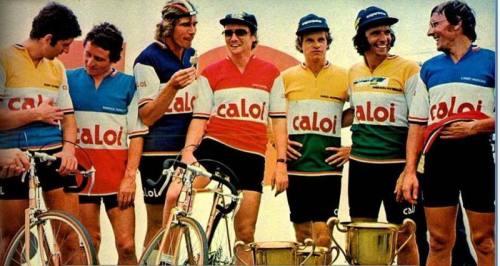

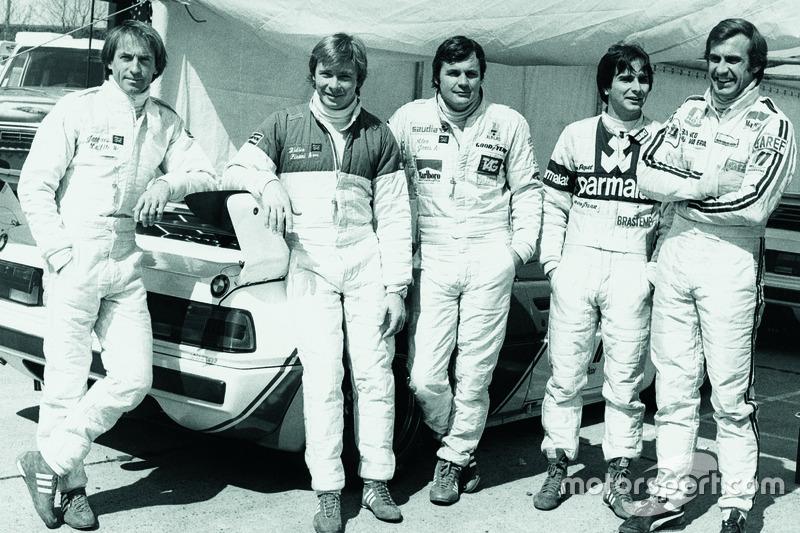

Left to right: Jody Scheckter, Patrick Depailler, James Hunt, Niki Lauda, Ingo Hoffmann, Emerson Fittipaldi, Larry Perkins. Source: pedal.com.br.

Nelson Piquet, one of the most successful drivers of all time, was a gypsy driver who lived on a boat that was driving him around the Mediterranean.

Nelson Piquet with his seven children on December 30, 2017, at Brasilia-DF International Airport. Behind, Geraldo and Pedro. Seated, Marco, Kelly, Laszlo, Nelson, Nelsinho and Julia. Personal photo of Julia Piquet.

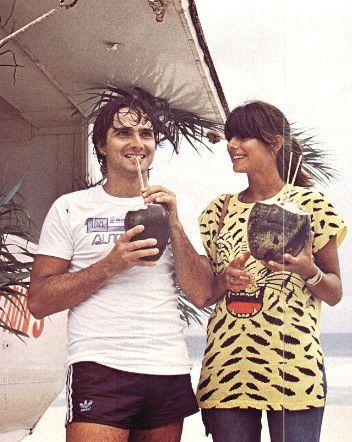

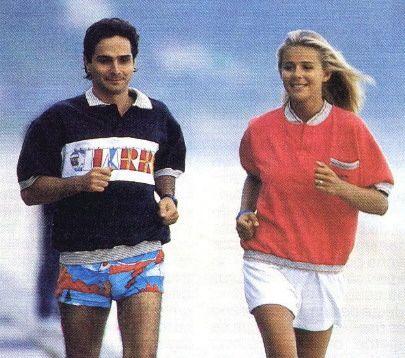

Nelson Piquet and his former Dutch wife Sylvia Tamsma.

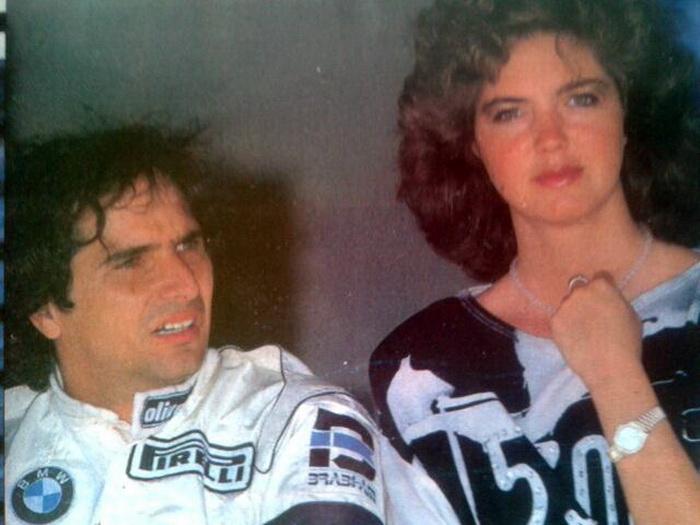

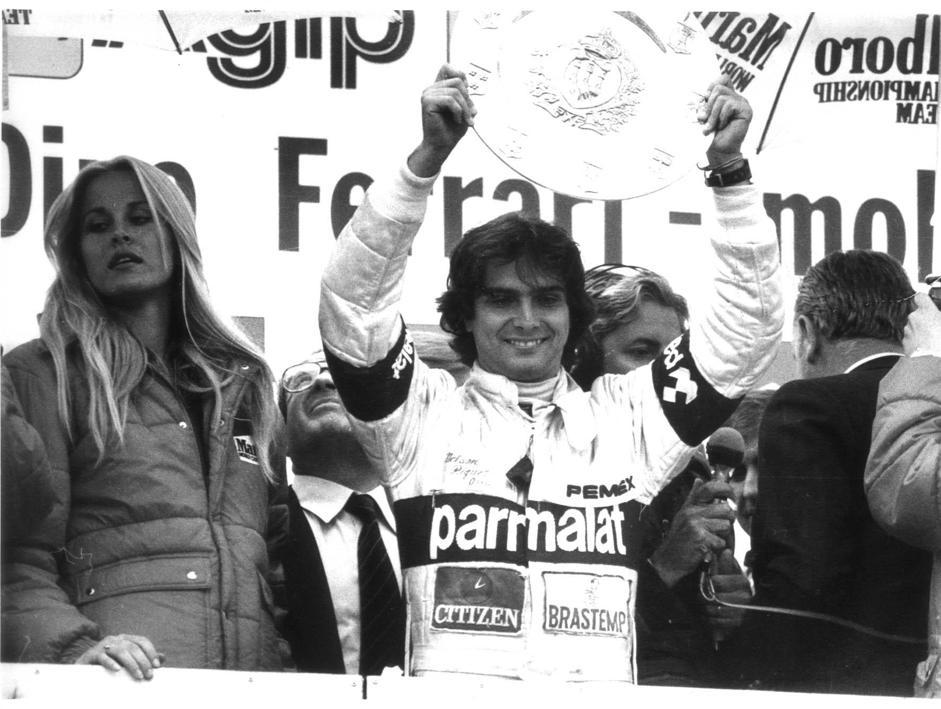

Nelson and Sylvia Piquet at 1982 Monaco Grand Prix, Brabham box.

Nelson and Sylvia in 1983 at Detroit.

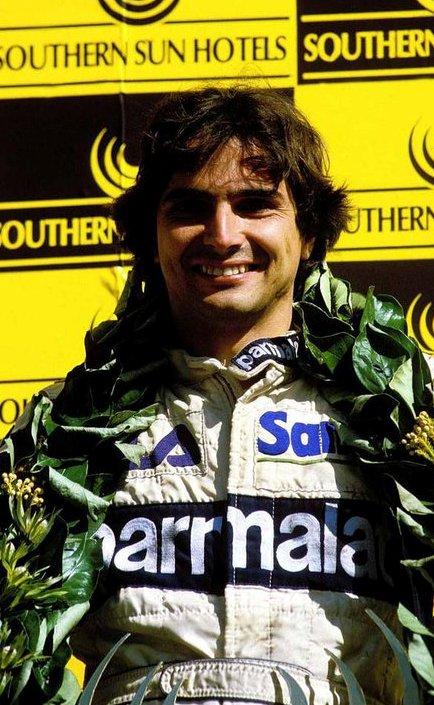

1983 South African Grand Prix at Kyalami. Nelson and Sylvia Piquet.

Very charming, full of fans, playboy, wives and kids scattered all everywhere.

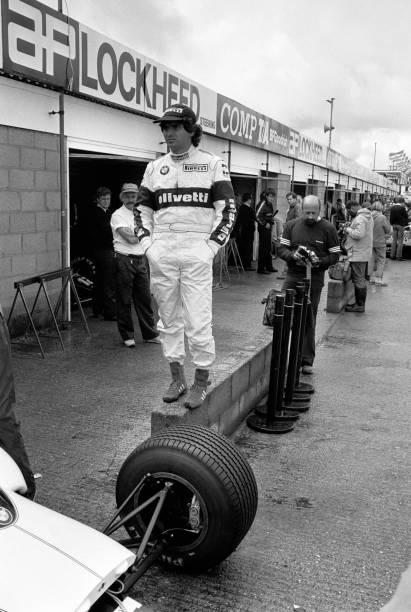

1984 British GP, Brazilian racing driver Nelson Piquet of team MRD International.

Smart, careful, made very few mistakes, not reckless as Mansell or calculating as Prost, a mix of the two, as well as an excellent test pilot.

Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell.

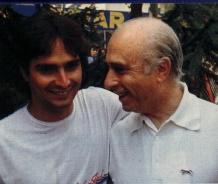

Nelson Piquet and Niki Lauda.

Gascon but also scathing, inelegant, rough. A potential 5 times world champion;

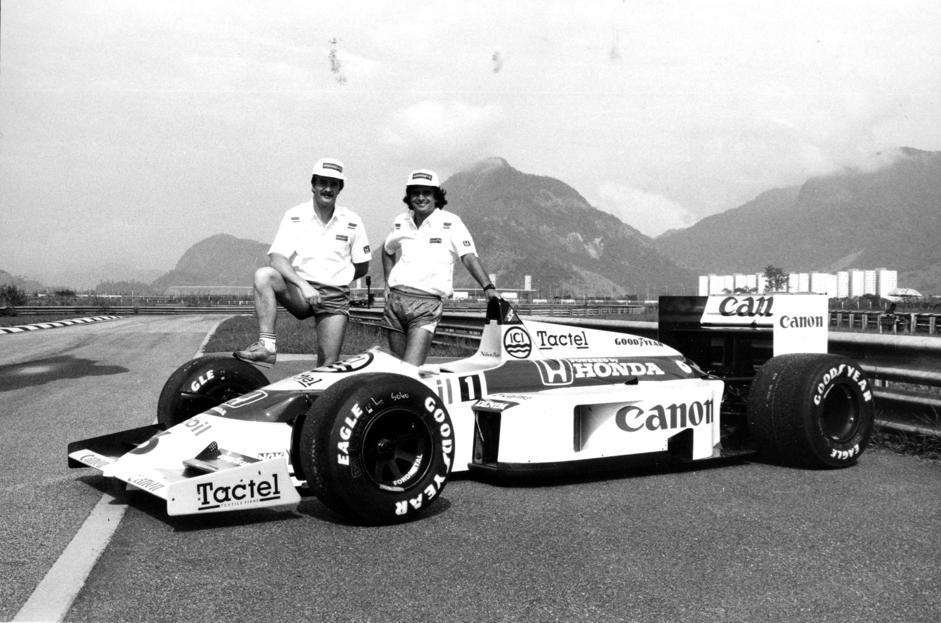

Williams Honda 1986, Mansell and Piquet.

in 1980 he lost the championship due to the car and in 1986 because of problems with the team that favoured Mansell, who however was often faster than him.

Nelson Piquet at Jacarepagua in 1986.

He deserved all three world titles, being capable of winning two of them at the last race. Great driver and great character off the track; not much of a good manners specimen, he loved to enjoy life not just thinking about cars. He might’ve won much more if he concentrated more on his driver’s career but at that time pilots were aware of their lucky and risky profession and between races they were messing. How Forghieri wrote, Lauda too, prototype of calculator, after the first world title started thinking about something else. Can you imagine Schumacher showing up late for a training session at a gym? Piquet, maybe, wasn’t beyond the cyclette ……

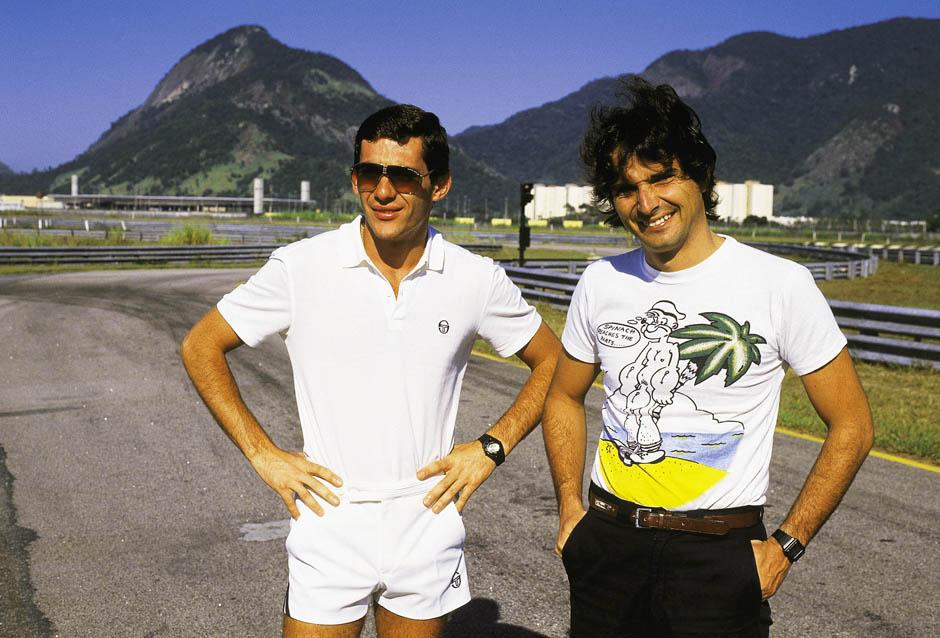

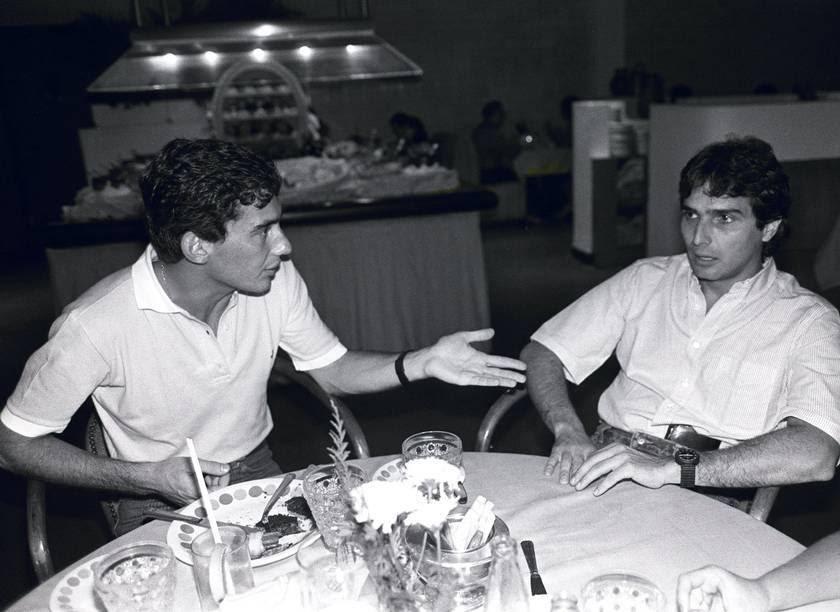

1980, Ayrton Senna and Nelson Piquet model some casual looks in Brazil. Nelson’s t-shirt and pants combo wouldn’t look out of place on a hipster today. Ayrton’s tennis-inspired outfit, not so much.

Overtaking Senna was one of the best pass ever but seasoned, as he said in an interview, by the bellow “get the hell out”.

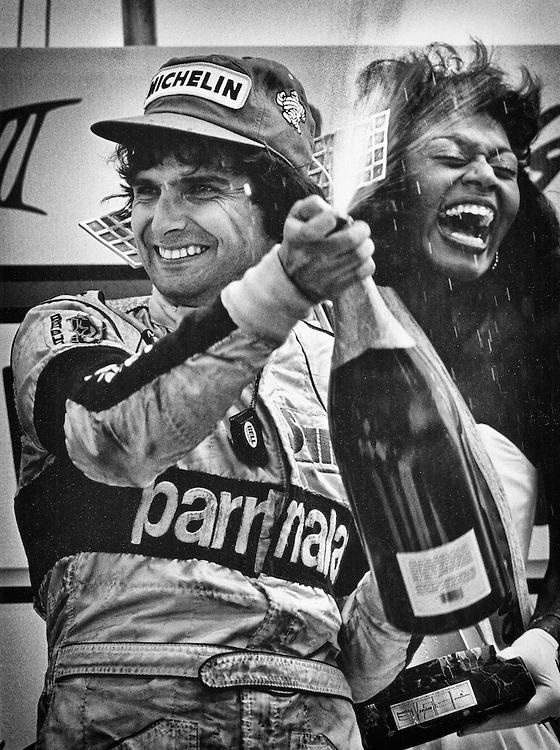

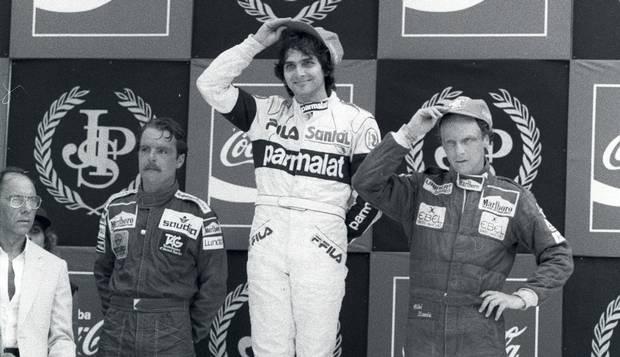

Two-time Brazilian World Driving Champion Nelson Piquet celebrates his victory in the 1984 Detroit Grand Prix, driving the Parmalat- MRD-Brabham-BMW BT53. Copyright Richard Kelley Photography.

Piquet was capable of remarkable feats such as the pass in Hungary in 1986 or the win at Detroit in 1984 despite the oil radiator on the front of his Brabham that burned his foot.

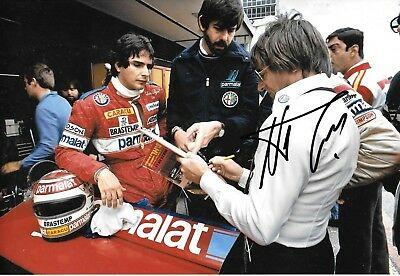

In 1984, Charlie Whiting, head of mechanics at Brabham (in white gloves), alongside South African designer Gordon Murray. They work on the settlement of Nelson Piquet's Brabham-BMW. Photo Reproduction.

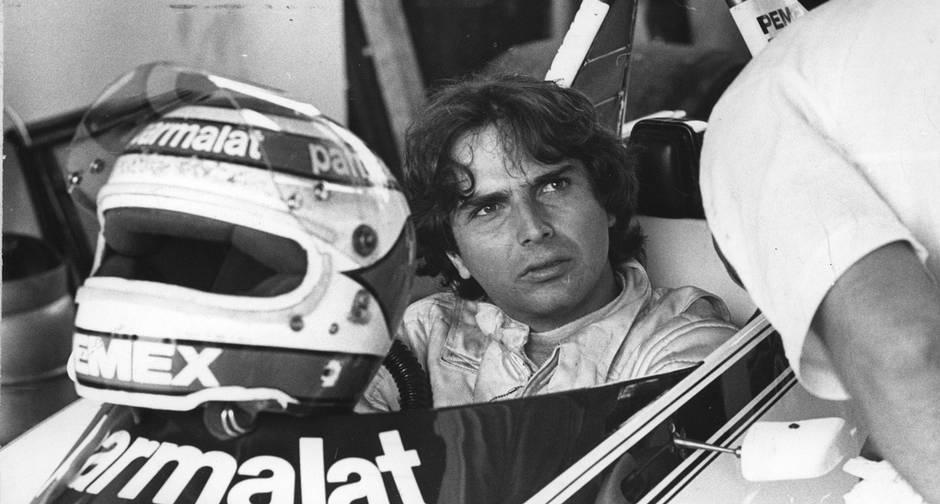

Capable of tame and get the most from the monstrous and wild 1300 horsepower BMW turbo engine with whom he won the 1983 world title and achieved nine pole position in 1984 (then GP were far fewer than today).

Nelson Piquet in 1983.

He always speaks up and sometimes his statements were exaggerated by the press (like his arguments with Senna and Mansell) and came back on him.

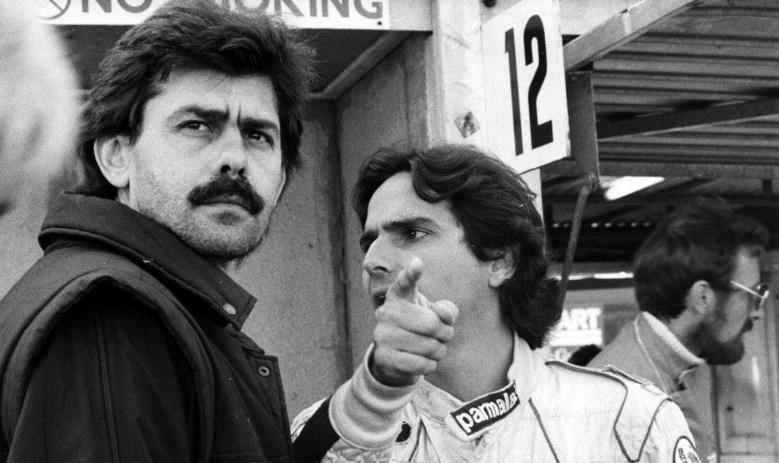

Gordon Murray and Nelson Piquet in 1981, one of the years they worked together at Brabham. Photo Disclosure.

Nelson Piquet with Bernie Ecclestone and Gordon Murray in 1983.

He didn’t like Montecarlo circuit “absurd, like riding a bicycle in the living room” but, despite this, he was there second in 1983 and risked to win in 1981.

San Marino Gp 1981.

He was very popular in Italy and when he won Ferrarista public always applauded him enthusiastically under the podium (3 wins at Monza and 1 at Imola) even when, in 1983, he won beating Arnoux who, driving a Ferrari, found himself fighting for the title with him and Prost (booed) in a Renault.

Nelson raced in Formula 1 from 1978 to 1991 dueling with some of the best drivers of all time and his world titles are heavier for that.

Pierluigi Martini, Stefan Johansson, Nelson Piquet, Jacques Laffite, Michele Alboreto, Alain Prost and Philippe Alliot.

Keke Rosberg, Nelson Piquet and Niki Lauda.

Nelson Piquet rides on John Watsons McLaren.

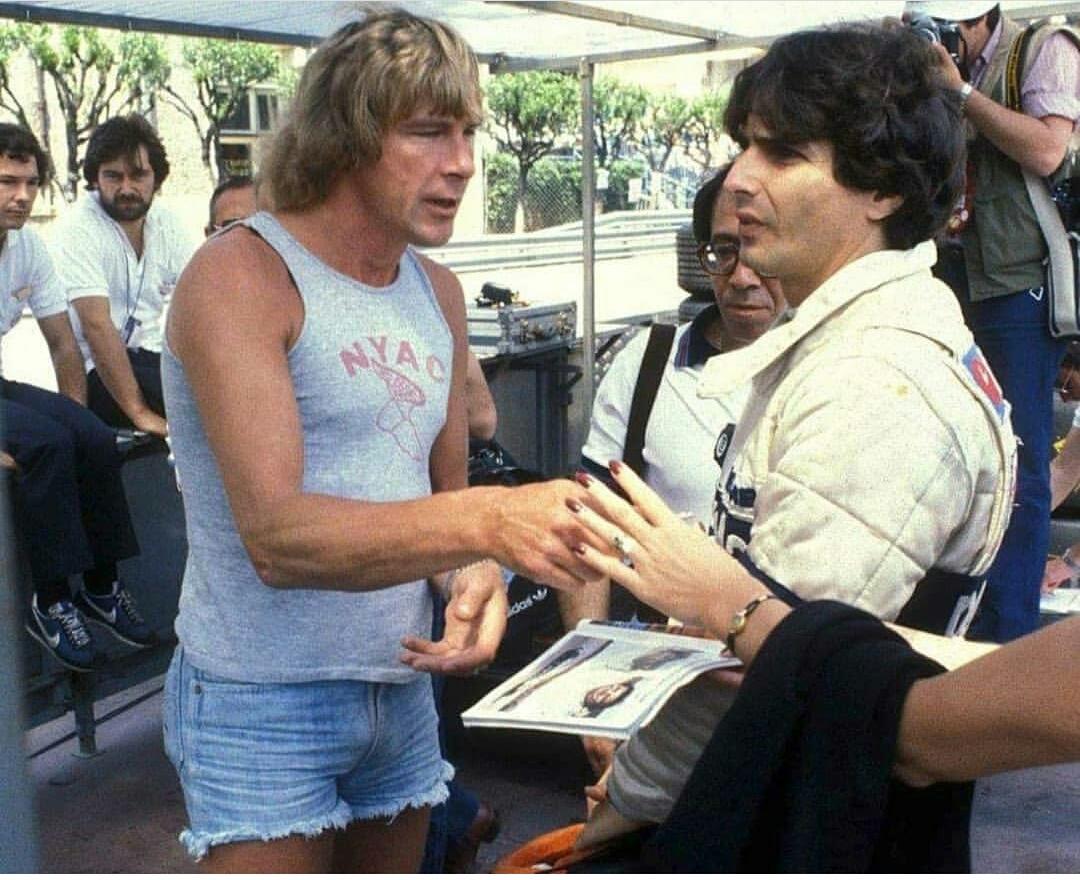

James Hunt with Nelson Piquet.

Stefan Johansson, Mclaren, Nelson Piquet and Ayrton Senna.

Lauda, Prost, Andretti, Pironi, Villeneuve, Depailler, Laffite, Senna, Mansell, Alboreto, Jones, Reutemann are just a few of aces he found in his way.

Nelson Piquet at the 1987 Monaco Grand Prix.

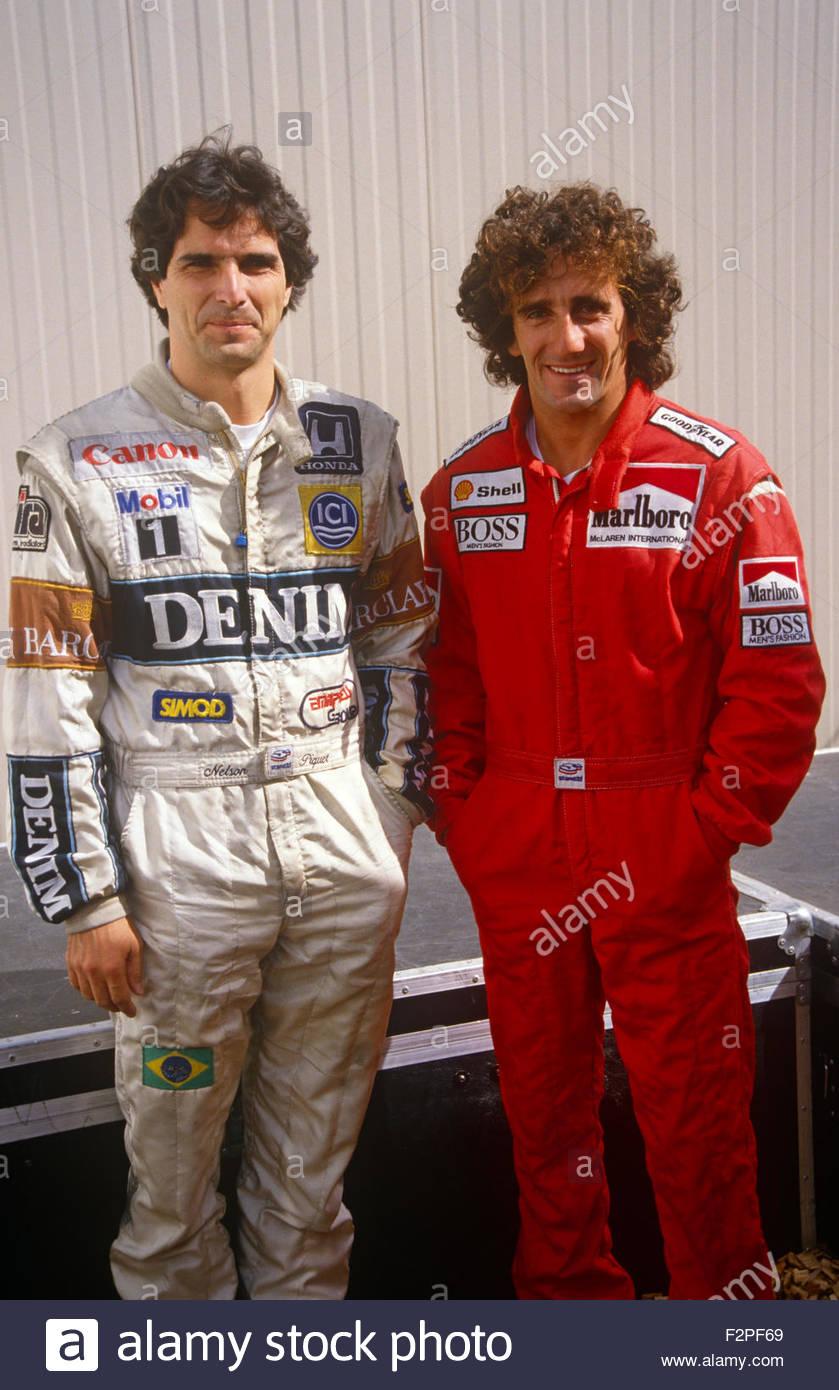

Nelson Piquet and Alain Prost in 1987.

In 1986-1987 only he was given a car far superior to others but he had a team mate like the lion Mansell: memorable duels! Nelson and drivers of his era had a more difficult life than Schumacher’s one. The German, great champion indubitably, didn’t really have many competitors (Hakkinen and Hill) up to 2005 (Alonso arrives) and could take advantage of an unbeatable Ferrari and a whipped by contract team mate. A serious accident with no apparent physical consequences in 1987 at Imola into Tamburello turn tainted him; he stayed up nights for several months but despite it he managed to beat his team mate Mansell, who suffered as well a big accident in Suzuka.

Michael Schumacher passes team mate Nelson Piquet in the 1991 Spanish Grand Prix.

As it was for Lauda when Nelson joined Brabham, even for Piquet it had got to stop when in 1991 a young team mate let him gone to a great deal of trouble to hold him off. He was Michael Schumacher! In 1992 Benetton would call him back at the side of Michael in place of Brundle as the two had problems to develop the car but unfortunately Nelson had just smashed his legs at Indianapolis. Despite this terrible crash he showed up the next year, although limping and in pain, to race the Indy 500, that he didn’t finish due to an engine failure. The Brazilian was quick, brilliant, capable to improve a car and motivate the team, while maintaining a Latin temper that put him in the hearts of polemics. He was one of the kings of ‘80s. Winning three world titles and with plenty of accomplishments achieved fighting against Prost, Lauda, Senna and all the other champions gives a sense of how, in a different era, Piquet’s career would have been different in terms of numbers. Compared to champions of Schumi’s era and following, drivers of the time couldn’t disregard experience, and to manage to successfully drive so difficult cars needed years of training in minor teams before approaching the top ones. For some years now, however, due to plenty of pit stops, we see mini GP of about 20 laps each and cars always on top in terms of weight, efficiency and performance of tyres. This is why we see today baby drivers who win right away and possibly in a top team from the first year of Formula 1. Piquet fought for the title from 1980 to 1987 and in those years Senna, by age and car available, didn’t compete for the world championship.

Senna with McLaren-Honda and Piquet with Lotus-Honda, in 1988. Ayrton won his first title, while Piquet had a difficult year, in Lotus in complete decline. Nelson ended the season in sixth place.

Having seen the Piquet post 1987, considering him among Senna’s competitors seems like a stretch.

Prost, Mansell and Piquet.

Piquet, Prost and Mansell.

His real rivals were Prost and Mansell. Probably less good than the first, certainly smarter than the second. To his detractors Piquet won more and not less than he would have merited. However, intelligent, incisive and no sufferer of fools, he commanded deep loyalties that remain firm to this day.

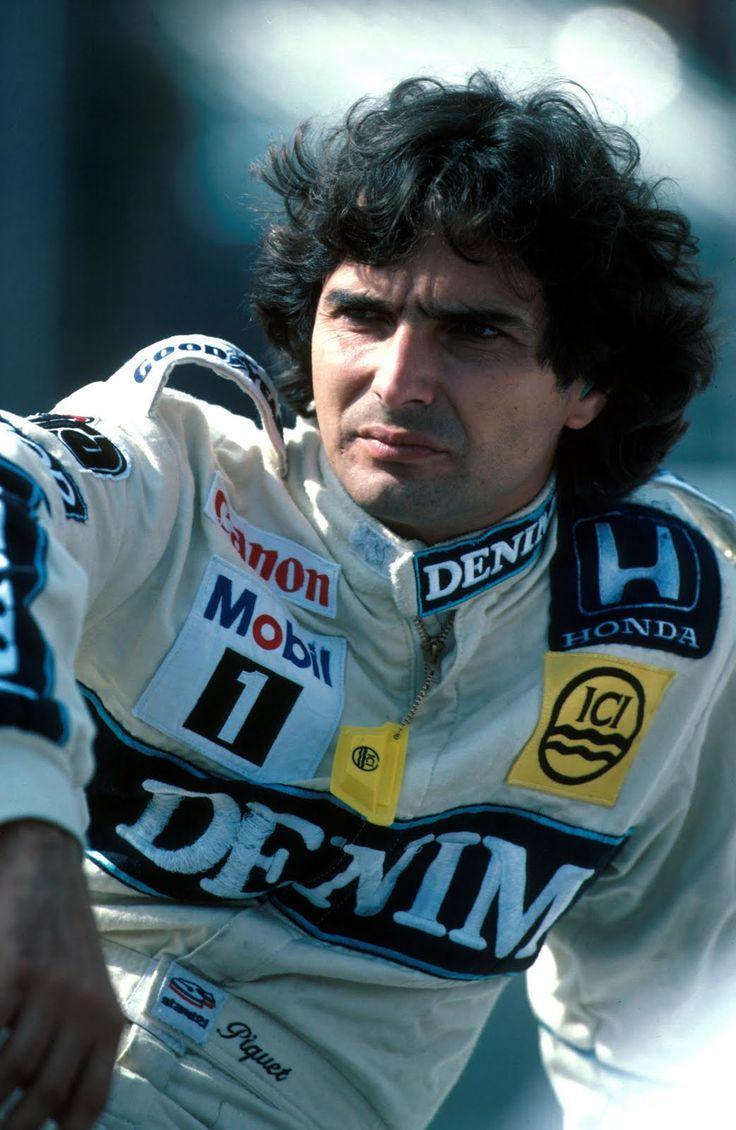

Nelson Piquet in a Williams.

Piquet says while driving for Williams in 1985 and 1986 as Mansell's teammate, 'I discovered that the Englishman (Mansell) knows absolutely nothing about setting up a car'. Piquet said when he found ways to make the Honda-powered Williams run faster, he waited until the last minute before a race to make the change, to prevent Williams designer Patrick Head from passing the information to Mansell. 'The difference between me and Mansell is that I've won three world championships (1981, 1983 and 1987) and Mansell has lost two', Piquet said.

Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell clash in the 1988 Japanese Grand Prix.

He thought Mansell made little effort to take part in the final two races of the 1987 season not because of an accident in Japan but because he already knew he would lose the title. 'I don't say he's a coward, but he saw that it would look better losing the championship this way (sitting out the final races) than getting worked over on the track', Piquet said. 'Mansell is argumentative, he's rude and he's got a really ugly wife. He's arrogant, and after he started winning races he started treating everyone really badly. Besides which, he's written off piles of cars. No one wanted him to win', Piquet said. Nigel Mansell would have felt a vague sense of injustice for he had clearly won more races than Nelson throughout the season when Piquet won the 1987 driver’s title by winning only three races to Mansell’s six. Piquet was less harsh with Senna. 'Ayrton is very dedicated, he's very quick and if he hasn't been champion yet it's because he wastes more time and breath trying to arrange excuses for his defeats than he spends working on his car'. The world champion said that in 1985 and '86 Senna blamed his lack of wins on the Lotus Renault engine, but then failed to again in 1987 when Lotus used the more powerful Honda unit. 'The problem was in the chassis and not the motor, but Ayrton couldn't see that', he said. Piquet said of his Lotus teammate Satoru Nakajima of Japan: 'Even someone driving a Formula One racer for the first time wouldn't be as bad as Nakajima, although he'd be almost as bad'.

Love him, hate him... He didn't give a damn. And he still doesn’t. Notorious Nelson Piquet stoked both anger and admiration on his way to three F1 titles. Images linger of a crass troublemaker – but lest we forget, he was defiantly talented too, as well as F1's funny man. He won three world titles and always took motor racing very seriously. However, he’s perhaps better known as a practical joker, always pulling funny faces and always game for a laugh.

Nelson Piquet Souto Maior, known as Nelson Piquet, is a Brazilian former racing driver and businessman. Since his retirement, he has been ranked among the greatest F1 drivers in various motorsport polls. Born August 17, 1952 in Rio de Janeiro, then the capital of Brazil, Piquet is the son of Estácio Gonçalves Souto Maior, a Brazilian physician. His father moved his family to the new capital, Brasília, in 1960 and became Minister for Health in João Goulart's government (1961–64). Piquet had two brothers, Alexis, and Geraldo and a sister Genusa. He was the youngest of the children. Born in a well to do family but had to fight a lot of battles to race competitively. His father wanted him to be a professional tennis player and after he did well in the junior circuit in Brazil, he was sent to California. Piquet matured to be a good player but not a great one and he soon realized that tennis did not excite him as much as racing did, so he decided to return to Brazil.

Roberto Pupo Moreno and Nelson Piquet, struggling hard to go karting in the early 70s.

Piquet’s dad did not approve of him kart-racing and so he had to use his mother’s maiden name ‘Piquet’ when he was just 14 to conceal his identity from his father. He made good strides in the national karting circuit, winning the National Championships in 1971 and ’72, and soon people were beginning to take notice of this wonder-kid. His parents tried packing him off to a University two years into an engineering course in 1974, hoping philosophy and engineering would distract him. It didn't. He dropped out after just a year and was subsequently employed in a garage to finance his career, since he had no financial support from his family.

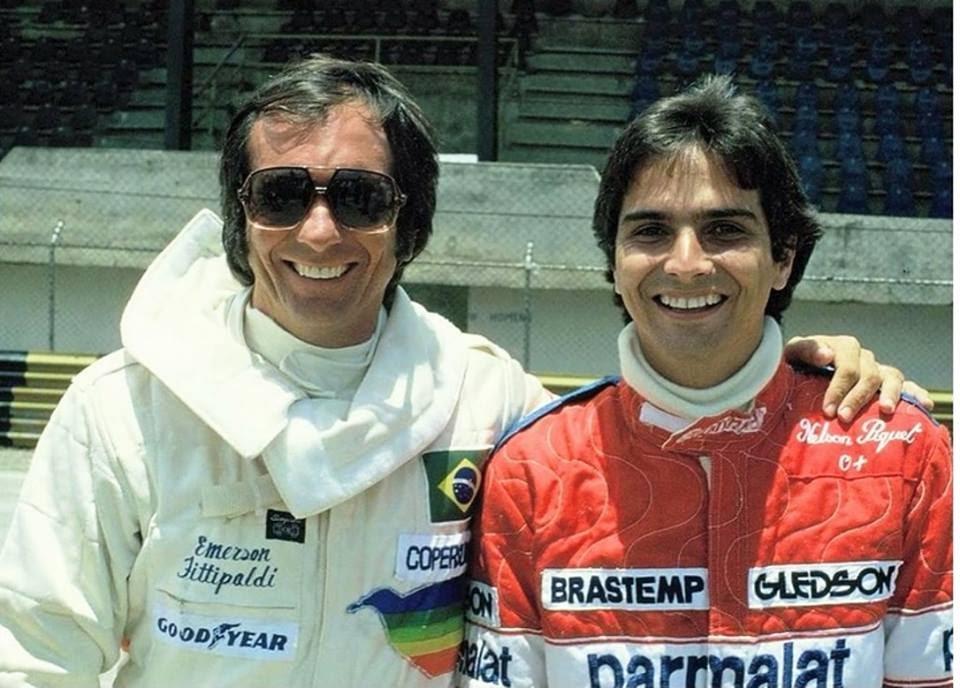

Emerson Fittipaldi (then at the Copersucar-Fittipaldi team) and Nelson Piquet, Brabham, at Interlagos, in 1979. Foto Facebook Cersersucar Fittipaldi.

Upon the advice of the legendary Brazilian driver Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson left Brazil for Italy in 1977 at the age of 24 and, after a year of acclimatizing, took to Formula 3 where he was hugely successful while living in his truck, then moved to England to contest the (two) British titles breaking Sir Jackie Stewart’s record of most wins in a single season in 1978. The British F3 campaign, in which he beat Derek Warwick by a handy margin in the BP championship, attracted attention not only through Nelson’s successes, but also for his dedication to testing. Those cash bonuses allowed him to run a test car, with which he covered twice as many miles as he would do in the whole season’s racing and he spent as much time under the car as in it. Rather than use the Toyota-Novamotor engines supplied from the UK agent’s pool, he was also in the habit of delivering his own units to the factory in Novara, which is a long haul in a clapped-out Cortina estate. He would take a couple of litres of British fuel, too, to ensure a perfect tune on the Italian dyno. Nelson had learned that being minutely prepared in advance was the best way to avoid having to take risks in races. While this was a policy that would serve him equally well on the Grand Prix circuits, it has also led to ill-advised accusations about his level of commitment as a driver. Nelson had the knack of finding good men to support him. Managing the F3 campaign for him in England was Greg ‘PeeWee’ Siddle, a tall Australian whom he had met at the Ralt factory, where he had rented workshop space from Ron Tauranac in 1978. Siddle was drawn by the Brazilian’s astuteness (they are devoted friends to this day) and ability to think on his feet. His F1 dream grew closer when he bought a Formula Vee racing car and went on to become the Brazilian champion in 1977.

Piquet receiving advice from Emerson Fittipaldi, before a Super Vee test. Photo Lemyr Martins.

Fittipaldi then advised the young Piquet to test his skill in the Formula Three programme in Europe, so he did. He won 13 out of 26 races, earning him the championship in 1978.

Piquet rented a car from the Ensign team and made his first race in Formula 1 on July 30, 1978, at the Hockenheim circuit in Germany.

He made his Formula 1 debut in 1978, vaulting any intermediate category, at the German Grand Prix with Ensign and qualified 21st. Piquet made an impressive start to the race but his engine broke down.

Nelson Piquet, McLaren, Austria 1978.

Piquet signed with the Brabham team for the last race of the 1978 season, which was owned by current F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone. His team-mate was the legendary Niki Lauda, winner of two F1 world championships. While popular lore records that Ecclestone took advantage of his new driver’s lack of business acumen to impose harsh conditions, Nelson insists that he never felt exploited by his new boss. “Bernie came with the contract and said, ‘can you understand English?’ I said yes, so he made me sign a paragraph stating I had read the contract and understood it. After I signed it, he said, ‘don’t you want to know how much I’m going to pay you? I’ll pay you $50,000 for the next three years and 30 per cent of the prize money.’ That was fantastic. I was in Formula 1! I didn’t care about the money, all I ever wanted was to be in Formula 1. And I had signed a contract”. “I was very happy with it. In the first year I made close to $800,000, because I won the [BMW] Procar series, there was a lot of money for racing those cars. Then, every time I found a sponsor in Brazil and gave the cheque to Bernie, he put it in the bank and gave back half to me. We had some big companies, domestic appliances, beer, stuff like that and they paid $80,000, sometimes $200,000.”

Nelson Piquet, Gordon Murray and Bernie Ecclestone at Brabham.

At Brabham, Nelson would find himself working alongside Gordon Murray, the fast-rising South African engineer whose left-field genius has provided F1 with some of its cleverest, most stunningly attractive designs. “Nelson was bloody clever, in ways of setting up the car and driving it”, he said. PeeWee says. “At the time he went to Brabham Gordon was already working on things like a cockpit-operated brake-balance adjuster for his F3 car and that was a godsend to Gordon because Niki Lauda wasn’t interested. ‘It’s just one more thing to break’, he said, but Nelson pushed ahead, insisting to Niki that “Gordon was the right guy to make sure the clever bits would not break”.

1979 Belgium GP. Jaques Lafitte, Didier Pironi, Alan Jones, Nelson Piquet and Carlos Reutemann.

Although Piquet could only finish four out of the fifteen races he took part in that season, it still bettered the result of his team-mate Lauda, who could finish only two. Piquet did not have a single podium finish to his credit that season but that was largely due to the unreliable Brabham car at his disposal. The partnership with Murray didn’t fully blossom until 1980, by which time Ecclestone had finally been persuaded to ditch the disastrous engine deal with Alfa Romeo and return to Cosworth power.

Nelson Piquet in action, driving a Brabham BT48 with an Alfa Romeo V12 engine for the Parmalat Racing Team, during the Monaco Grand Prix on 27th May 1979. Piquet retired from the race during the 68th lap with transmission problems. Photo by Leo Mason / Popperfoto via Getty Images.

Murray’s nifty Brabham-Ford BT49 was blessed with such effective aerodynamics that the only circuit where it would need even a smidgen of front wing to perfect its balance was Monaco. It would give Nelson a maiden F1 victory, at Long Beach, with only two other cars finishing on the same lap. On the way to setting pole, a delighted Nelson noted that all four Goodyears blistered at exactly the same moment. By now he was part of Brabham’s devilishly ingenious band of British and Commonwealth mechanics, led by Murray, whose respect for the fine print of the rules tended to go AWOL whenever an opportunity arose to defeat them. In the years to come there would be reports of lightweight qualifying cars that were craftily ballasted before officials could get them to the weighbridge. There were lead-reinforced nose-cones, special (40 kg) seats, even heavyweight wheels and it can be remembered Murray doing a poor job of denying that he’d built a lightweight qualifying car. Of course, the Brabham gang was not alone in these unsporting subterfuges, but nobody else was in the same class.

In 1979, when Niki Lauda was his team-mate, Nelson wasn’t averse to such shenanigans in his search for an advantage over the Austrian. “At Silverstone, the car was 18 kilos overweight and before qualifying I got the mechanics to take out first gear, because I didn’t need it for a flying lap. I got them to take out the fire extinguisher, too, which put my car just on the minimum weight. But Niki saw the car on the scales and went to complain to Bernie; he wanted to know why his car was 15 kilos heavier than mine. After that, my mechanic was taken off the job and I was not allowed to visit the Brabham factory anymore, because Niki realised I was spending my days there doing these things”. Far from souring the relationship with Lauda, the incident cemented a great and enduring friendship. “What I learned with Niki was how to communicate with the team”, he says. “Before I drove for Brabham, I never ran with any engineer. I had my own car and I made all my decisions about the set-up, I just told the mechanic what to do. Niki could describe what the car was doing, whether it was rolling or understeering or oversteering. I tried to feel the same things to tell the engineers. That was a good thing I learned. But the most important thing was that when I came into the team, Niki never left me by myself. He would take me with him to the restaurant at night and I don’t think today there is any relationship between team-mates like that. Usually when drivers are new in the team, no one wants anything to do with them. But Niki was so helpful on this point. He also gave me horizons in other directions. We started to talk about flying, he helped me to understand about aeroplanes, he convinced me to buy a plane, he told me what to do. All these things I got from Niki were very good for me”.

Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Nelson Piquet, Renault RE20, Brabham-Ford BT49, Grand Prix of France, Circuit Paul Ricard, 29 June 1980. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

1980 was a breakthrough year in Piquet’s Formula one career; with Lauda retiring at the end of the previous season, he was the main driver. Throughout the course of his career, it was seen that Piquet thrived when he had the team’s undivided attention – having a challenging partner was not something he preferred. He started the year well and finished second at the Argentina GP behind the eventual champion Alan Jones. Piquet’s form improved as the season went on and it was at the United States Grand Prix that he won his first competitive F1 race. He led the standings going into the final two races but lost out to Jones due to engine failures. It was disheartening to see the young man lose from such a comfortable situation but as it turned out, it made him more resilient and focused and was only a small bump in his climb to greatness. 1981 was the season that saw Piquet win his first Formula 1 Championship. With a few adjustments in the car setup (some of which often drew criticism from the FIA and fellow teams), Brabham appeared as the fastest car on the circuit and Piquet the driver to beat. Things, however, were not that straightforward and abject engine failures had Piquet trailing Carlos Reutemann by as many as seventeen points at one stage of the season. He, however, staged one of the greatest comebacks in F1 history when he clinched the title at the last race in Las Vegas after finishing fifth, winning by a solitary point over Carlos. So exhausted was Piquet by the heat and the tension at Vegas that at the end of the race, he had to be lifted out of his car. A lifelong dream had been accomplished for the Brazilian, whose only ever goal in life was to drive fast. “I don’t want to make friends with anybody. I don’t give a s*** for fame. I just want to win”. Piquet had tasted glory and was now enchanted by it.

Nelson Piquet left his Brabham to help Didier Pironi during qualifying for the 1982 German GP in Hocheinhem. Pironi crashed his Ferrari against the guardrail after touching Alain Prost's Renault. Pironi never again competed in F1 after having undergone more than 30 surgeries on both fractured legs. Photo Disclosure.

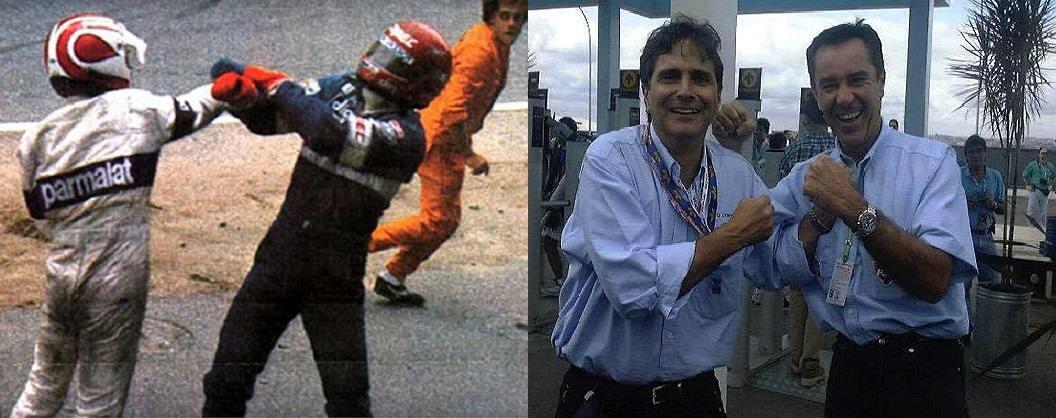

He now wanted more but 1982 was an up and down year for him. Brabham had made an alliance with BMW and introduced turbo-charged engines to the car, but they were too unreliable and as a result, Piquet suffered. He won the Brazilian GP but afterwards, again fainted on the podium. The car also had an on-going battle regarding its weight and was constantly questioned by Ferrari and Renault. This led to his disqualification from the Brazilian GP and his only win of the season came at the Canadian GP. It was also in 1982 that he laid into the hapless Chilean driver Eliseo Salazar at Hockenheim for causing him to crash.

He was involved in an on-track fist-fight with fellow driver. As Nelson walked back to the pits a van pulled up to drive him back. Salazar was inside. The Brazilian flared up again and when Salazar and the driver stepped out of the van to calm him down, Nelson jumped into the driver's seat and sped off, leaving them to walk back! He was on course for his second win of the season. He finished a disappointing eleventh in the driver standings.

Fun moment between Piquet and Salazar in 2012, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of their epic fist fight at the 1982 German GP.

Nelson Piquet, Brabham BT52. Photo by Jay Penrith.

The 1983 season saw Piquet win his second Formula 1 title and the first with a turbocharged car, the BT52, after a long battle with Alain Prost. He won races in Brazil and South Africa and backed it up with strong finishes at Italy and Monaco as well. The season also saw the arrival of the young Frenchman Alain Prost, who would be his chief rival in the years to come. The following years were not so fruitful for Nelson as the repeated unreliability and technical problems of the team made it difficult for him to gain a level of consistency.

Nelson Piquet, driving for Brabham-BMW, stands on a wall in the pit lane as drivers compete in a qualifying session for the 1985 British Grand Prix at the Silverstone Circuit, near Towcester, Northamptonshire, U.K., on Saturday, July 20, 1985. Photo by Bryn Colton / Getty Images.

Towards the end of the 1985 season, he decided to move on after a seven-year stint with the team which yielded two drivers championships. He left Brabham and considered retiring, having grown tired of the constant travelling involved in the sport. However, Lauda convinced him to buy a private jet to make life easier, if somewhat costlier. He also bought a huge yacht and began living the life of a playboy, fathering several children from a series of gorgeous women along the way. He then joined new teammate and fierce rival Nigel Mansell at Williams in 1986 (for a then-record $3.3 million), and so began two fascinating years. One of the greatest F1 rivalries between him and the Briton. The car was a winner but Mansell and Piquet hated each other. They were the most talented drivers on the circuit and pitting them in the same team was a disaster waiting to happen. And it eventually did, costing them both a driver’s championship at the hands of Alain Prost who won the championship despite possessing an inferior car. Piquet was furious with the Williams team for not giving him the number one driver status in the team and instead allowing both of them to go for the win. Incidentally, this was the most successful season for Piquet as he ended the year winning four races, the most he ever would. “Piquet is just a vile man” – Nigel Mansell. Although Nelson had a handsome win in his first outing with Williams-Honda, in Rio, the team had been weakened by the car accident that so grievously injured Frank only a few days earlier. Nelson’s driving also seemed to have lost some of its consistency: by season’s end he had won four races to Mansell’s five and also suffered a number of untypical retirements, albeit not as many as those so carelessly racked up by Mansell. The now-celebrated climax to the season at Adelaide, where the two Williams boys in their Honda-powered FW11s were in contention for the title, ended when a tire failure eliminated Mansell and Piquet was forced to stop for fresh rubber after he felt one of his own Goodyears about to fail. Prost took the crown. 1987 saw more fireworks between the two and it was in this season that Piquet applied his famous “percentage driving policy”, which saw him rack up a staggering ten podiums in sixteen races and confirmed his third and final F1 championship. This was undoubtedly the best championship win for him after he suffered a crash at Imola early on and then had to withdraw in the Belgian GP. He made a strong return, going on a run of nine successive podiums. At Imola, during qualifying, another tyre failure sent Nelson crashing at Tamburello. Still concussed, he was back two weeks later for the Belgian GP, well under par. “That was bad”, he admits. “I had lost 80 per cent of my depth of vision, and I only told anyone at the end of the year. Otherwise, they would not have let me race. That’s the reason why I was so bloody slow!” Did Mansell ever try to take advantage of his lack of sharpness? “He didn’t know! Nobody knew! In the first race after Imola I was one and a half seconds a lap slower and I somehow managed to hide it”. At Silverstone in July Nelson suffered defeat at the hands of ‘Our Nige,’ who had made an early and unexpected tire stop after a wheel balance weight came off. Mansell fought back, memorably tracking down his team-mate and selling him what appeared to be a crafty dummy at Stowe to snatch the lead with three laps to go. Unknown to the public and TV commentators, however, Nelson was paying close attention to his fuel read-out, which was showing a worryingly negative figure. Knowing that his team-mate’s fuel management skills were consistently inferior to his, Nelson was confident that Mansell’s tanks would run dry before the flag appeared. What he didn’t know was that the Honda engineers had made an untypical pre-race miscalculation. “Mansell was a long way under on the fuel, so he took a chance. He knew he was going to run out of fuel and he did ... 400 metres after the line”. The Briton’s victory that day, which owed as much to Honda’s mistake as his own derring-do, is held up as one of his greatest. I’ll leave readers to make their own judgment on that. Not that Nelson has ever shown any resentment about having come so close to securing what would have been a sensational win. “I was doing my job, exactly, using the power only when I could and so on. I didn’t push harder, because I knew how stupid it would look if I ran out of fuel. He gambled, he won”. Three victories for Nelson in late-season races, two of them at the expense of the luckless Mansell, would clinch his third title. The most satisfying of the trio was at Monza, where he was allowed to use the active suspension system he had been testing exhaustively for more than a year. Mansell, who had bad memories of a similar computer-controlled system that had failed under him when he was a Lotus driver, had refused to take part in most of the ‘active’ testing and had to make do with conventional springs. His feelings can only be imagined as the ‘active’ car and its tyre-sparing limousine ride carried the Brazilian to a seemingly effortless win. Despite the Imola concussion and Mansell’s six inspired wins throughout the 1987 season, Nelson had employed his innate sensitivity to exploit the speed of the all-conquering Williams-Honda without stepping over its mechanical limits as boldly as his English team-mate was inclined to do. His three wins might appear to naysayers as something less than inspiring, but then he also picked up seven second places. How differently things might have turned out if only Nigel hadn’t picked the silly fight with Senna that knocked him off the road in Belgium, or hadn’t hurt himself in Japan in a completely unnecessary qualifying crash that eliminated him from the last two GPs of the season ... in both of which his team-mate was destined not to finish. The poisonous atmosphere at Williams had taken all the fun out of racing for Nelson, and he started to enquire about openings elsewhere. But rumours were circulating that Honda, whose management was inclined to blame the loss of the 1986 title on Frank’s infirmity, might bring its contract with Williams to an early end. Because Honda also placed a high value on the Brazilian, Nelson knew that Williams stood an even higher chance of losing Honda if he departed. His response was admirable. “When I heard that if I left Williams there was a chance that they would lose the engine, I told Patrick Head, ‘It’s OK, I [will] put up with the shit and will stay, because I don’t want to be the reason for you losing the engine’. Patrick believed that Williams had the Honda engine for sure in 1988, it was not important what I did. So I went straight off to talk to Lotus”. One month after the news of Nelson’s Lotus deal had been released in Hungary, Honda casually offered its “thanks” to Williams for its help and announced that it would be supplying only Lotus and McLaren in 1988. Frank and Patrick, now without both Piquet and Honda, were left in the cold with a race-winning car that had a big empty space behind the cockpit. “As I have pointed out [many times],” Nelson says, “we should have won [the title] in 1986, that first year with Williams and if I had continued with Williams and with Honda, we could have won four years in a row, no problem”. Nelson would race on in F1 for another four years.

Monaco GP 1988, Nelson Piquet in a Lotus 100T Honda.

His two seasons with Lotus in 1988/89 were financially rewarding but a sporting disaster, finishing sixth and eighth respectively: he says the car was so seriously lacking in torsional stiffness that it wasn’t worth even attempting to sort it out. By now, another Brazilian, Ayrton Senna, had taken the mantle as the Number one driver in Brazil from him and his rivalry with Prost was what had millions attracted to the sport. For the final two years, at Benetton, he had to accept the payment-on-results scheme offered by Flavio Briatore.

Benetton team mates in 1991: Nelson Piquet and Roberto Moreno. Photo By Rainer Schlegelmilch.

Two wins in 1990, in Japan and Australia, paid off handsomely, to be followed in 1991 by a famous ogre-slaying in Montréal. Mansell, who had a comfortable victory in hand with less than a lap to go, somehow managed to stall his Williams’s Renault V10 while waving to the fans at the hairpin and stuttered to a stop within sight of the flag. The ‘92 season turned out to be his last with the emergence of Michael Schumacher on the scene and Piquet quit at the end of the year after nearly fourteen years in the sport, aged 40. The farewell to F1 was not the end of Piquet the racing driver.

In 1992 Nelson Piquet suffered a very serious accident while training for the Indianapolis 500. His Lola Buick of the Menards team crashed head-on into the wall at turn 4. He suffered head and chest trauma, as well as multiple fractures in his legs and feet.

He had two attempts at the Indy 500, sorely injuring his feet in a heavy crash while practising for the first, in 1992. “I’d retired from full-time racing, but there were two things I still wanted to do, Indianapolis and Le Mans. At Indianapolis, they also paid me a lot of money. Actually, the car [a Lola-Buick] was very easy to drive, it was flat everywhere. Everything there is aerodynamics – and the stagger of the tires. I really loved the place. The problem is that when you’re testing there, every 16 laps you have to stop and come into the pits to refuel. If you lose just 20 minutes, you have to start all over again, because with the temperature changes and all the aerodynamics, everything is very sensitive when you’re doing 400kph. So I was very frustrated when they showed a yellow [flag]. I calculated very quickly that if I could get in, I could stop and still do one run. I was in Turn 4 when I lifted off, to be able to go into the pits and, when I lifted, I went off. The hit was very hard”. So hard, in fact, that the resulting leg injuries left his surgeons contemplating amputation. After several painful interventions, he went home with his feet intact, but not as useful to him as they had been. Walking downstairs is now a serious trial for him. But still he persevered with his non-F1 ambitions: he was back at Indy in 1993, only to have an engine failure, and was equally luckless in two outings at Le Mans that gave him just four hours at the wheel. He initiated a category of sports car racing in Brazil, took part in the Nürburgring 24 Hours and finally knocked his career on the head at Interlagos in 2006, sharing an Aston Martin DBR9 with three other drivers, one of whom was his son Nelson Ângelo Piquet.

Part of Nelson Piquet's fantastic collection of vintage cars in Brasilia.

He lives happily in Brasilia, where he went on to earn a fortune with his Autotrac, the hugely successful satellite tracking company he set up in 1994 after seeing a truck fitted with a similar system in the US back in 1992. The company provides mobile data messaging and tracking of customers' trucks by satellite (GPS tracking). This business concluded quite successfully as the pioneer because the freight transportation of Brazil depended on trucks. Since 2000, he has supported the career of his son, Nelson Piquet Jr. During the Crashgate scandal, Piquet pledged to use his wealth to find out why his son had been ordered by the Renault team to crash deliberately during the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix. He and his son were eventually paid a six-figure sum for costs and libel damages. Known as a practical joker, Piquet lived a stereotypically playboy racing driver lifestyle, earning and losing and earning again a series of small fortunes in his business dealings.

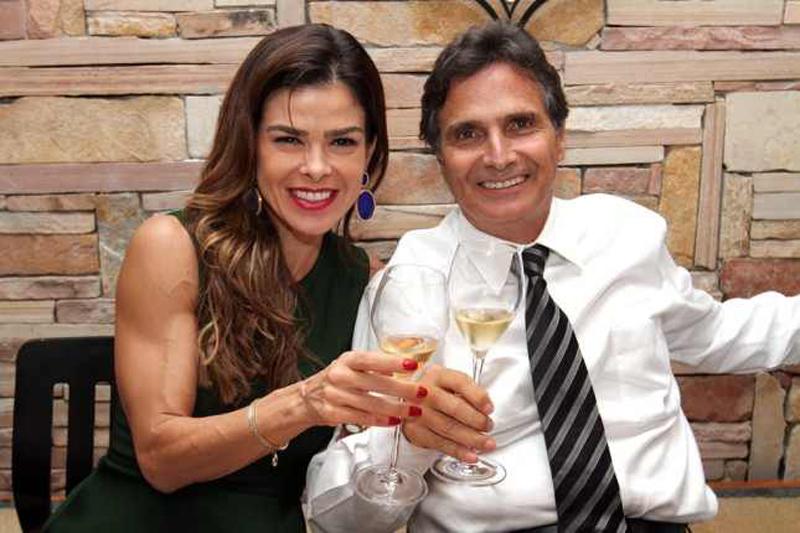

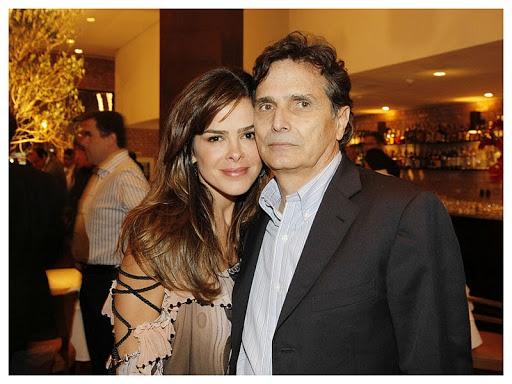

Viviane de Souza Leão with Nelson Piquet.

F1 Brazilian GP 2006, Nelson Piquet with his family.

Nelson Piquet with his fourth wife Viviane on November 11, 2015 at Espaço Bosque, site of the 19th edition of the Golden Helmet. Photo by Marcos Júnior, Portal T.

The days of relentless womanising are long behind him now and he has been happily married since 1998 to Viviane de Souza Leão, whose two sons with him have brought the Piquet brood up to seven.

Piquet entered into a first marriage with Brazilian Maria Clara in 1976 with the marriage lasting for one year.

Nelson Piquet and Katherine Valentin.

His second marriage was to the Belgian model Katherine Valentin.

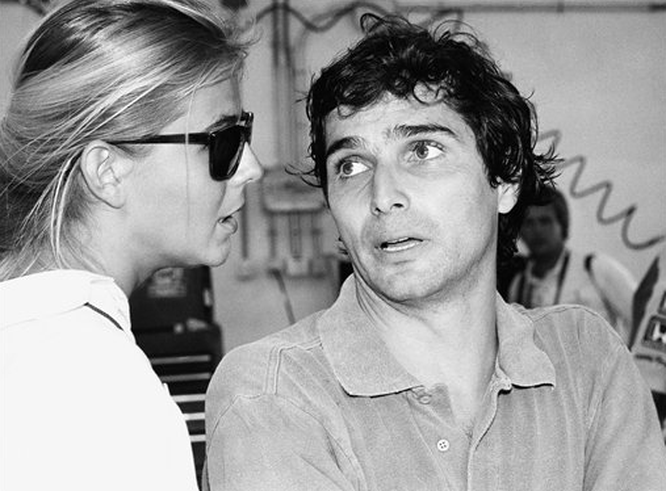

Sylvia Tamsma.

Third marriage to the Dutchwoman Sylvia Tamsma, who had previously dated Elio de Angelis. In a 2012 interview on Brazilian TV with himself and former Williams teammate Nigel Mansell, Piquet revealed that he had never been right after his accident at Imola in 1987. The crash caused him to lose some 80% of his depth perception and saw him secretly visit a hospital in Milan every two weeks through the season fearing that if he told his team they would not let him drive.

Nelson Piquet with his 1987 championship-winning Williams FW11B hanging on the wall of his home in Brasilia.

He went on to say that he should have won the championship in 1986 and Mansell should have won in 1987 and that after 1987 he drove for the money as due to his condition he was no longer able to lead races from the front (each of his six wins following his Imola accident were inherited from others dropping out late).

Chichester, England. Former F1 World Champions Nelson Piquet (left) sits in the cockpit of the Brabham BT52 from 1983 as Sir Jackie Stewart looks on at Goodwood Festival of Speed on July 14, 2013. Photo by Andrew Hone / Getty Images.

On 11 November 2013, Piquet underwent heart surgery from which he is recovering well.

Nelson Piquet in his personalized office in Brasília, recovering from cardiac surgery, on December 2, 2013. Photo Facebook by Nelsinho Piquet, son of Nelson.

For all the extremes of affection and hostility that Nelson Piquet attracted during 14 years in the F1 spotlight, he is left with no regrets. “I didn’t go racing in Europe for glory or to make a big name for myself”, he once said: “I came because a couple of friends thought it was a good idea and they found the sponsorship for me to do a season of Formula 3. I would have been quite happy to go home at the end of 1977 with a bit of Italian and some nice memories. But it all worked out differently...”.

Photo by Getty.

Piquet was always an eccentric driver who lived a playboy’s life. He had a house in Monaco with a boat that was always ready with a crew and he married women for fun, fathering a lot of children in the process. And yet, Piquet will forever be remembered for his consistency rather than his dominance in motorsport and to this day he remains the most successful Brazilian driver alongside Ayrton Senna. He was inducted into the International Motorsport Hall of Fame in 2000. He has two circuits in Brazil named after him. In 2012, BBC Sport ranked him 16th in the list of greatest F1 drivers.

On January 6, 2017, taking a speedboat ride in the Caribbean, in Saint Barths. Personal photo archive of Julia Piquet.

“Through F1, I bought my own boat. I learned to fly my own plane and helicopter. And my job with my company is a reflection of everything motorsport taught me”.

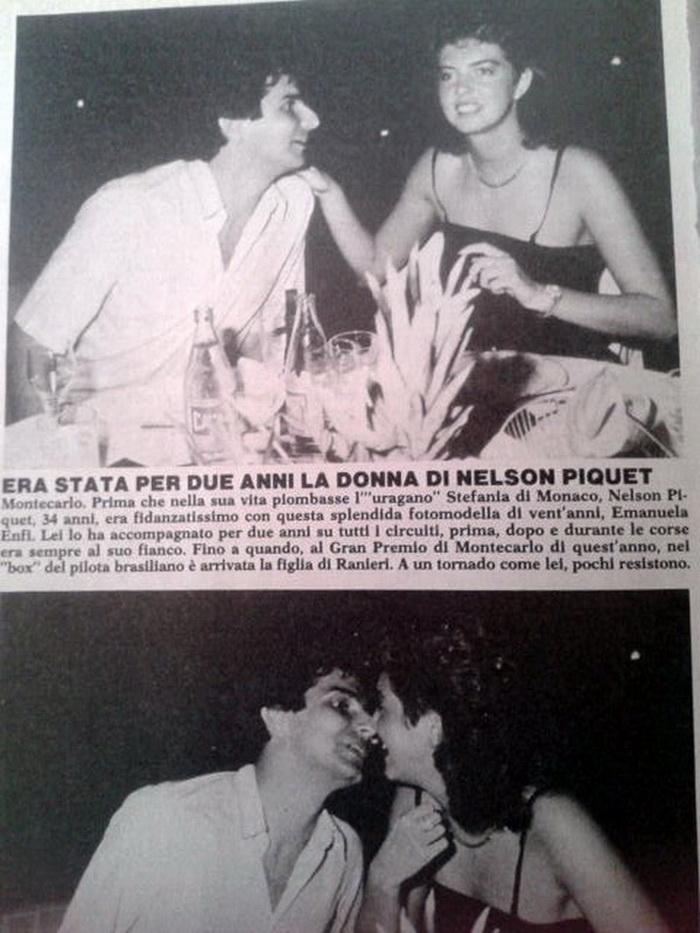

The supposed blots on his character would have to include suspicions about the legality of several cars he drove, doubts about his commitment to the job with the two F1 teams (Lotus and Benetton) that employed him at the end of his career and a long list of scurrilous and personal insinuations he slung at rivals. Not least among his targets stand the saintly figures of Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell. There is scant chance of Nelson, with his gruff contempt for self-appointed moralisers, ever achieving that sort of holiness, although he is an expert at knocking haloes askew. To get the full flavour of Nelson, it is essential to puncture the widely held myth of his ‘laziness’ and to demonstrate just how dedicated he was to making his way in the sport, even if it flagged briefly at the end. This is a man who built his first single-seater (a Super Vee) virtually single-handed, from the ground up. Yet such was his confidence in his own abilities, when he left Brazil for Europe, that the deals he had done with sponsors at home were based solely on outright wins, a scheme that would net £4000. “Here in England we did the same with BP and Champion: only to get money for winning. Instead of just a little bit of money for carrying the stickers, I got £600 from each of them for every win. And I won 14 races ...”. The British F3 campaign, in which he beat Derek Warwick by a handy margin in the BP championship, attracted attention not only through Nelson’s successes, but also for his dedication to testing. Those cash bonuses allowed him to run a test car, with which he covered twice as many miles as he would do in the whole season’s racing and he spent as much time under the car as in it. Rather than use the Toyota-Novamotor engines supplied from the UK agent’s pool, he was also in the habit of delivering his own units to the factory in Novara, which is a long haul in a clapped-out Cortina estate. He would take a couple of litres of British fuel, too, to ensure a perfect tune on the Italian dyno. Nelson had learned that being minutely prepared in advance was the best way to avoid having to take risks in races. While this was a policy that would serve him equally well on the Grand Prix circuits, it has also led to ill-advised accusations about his level of commitment as a driver. Nelson had the knack of finding good men to support him. Managing the F3 campaign for him in England was Greg ‘PeeWee’ Siddle, a tall Australian whom he had met at the Ralt factory, where he had rented workshop space from Ron Tauranac in 1978. Siddle was drawn by the Brazilian’s astuteness (they are devoted friends to this day) and ability to think on his feet. Riccardo Patrese, who joined Brabham in 1982, earns rather fewer points from Nelson as a valued team-mate. “Well, he was a crying boy”, Nelson says. “He was always complaining about the car, saying that BMW would not give him equal treatment. But he was just plain bloody hard on the car. There was no way he could drive on the limit for 70 laps: the gearbox and driveshafts would not take it. If you are in front you have to take care of the car. How many drivers get in front and blow the engine or the gearbox like he did, or just crash out as he did when he was leading at Imola in 1983? Only the useless ones ...”. This is the abusive stance Nelson adopted towards some of his toughest rivals and it has kept certain journalists’ self-righteous rebukes tumbling down on him ever since. For Alain Prost, however, he has always had admiration. In the lead-up to his 1983 title showdown with the Frenchman, Nelson frustrated the media’s plans to beat it up into a personal grudge-fight by inviting ‘the Professor’ to have lunch with him on his yacht in Monaco, ensuring that there were photographers there to record the meeting. Then, after Prost had retired from the deciding race at Kyalami, Nelson spoke out in his rival’s defence. “It was not Prost who lost the championship”, he told a bunch of French reporters post-race, “it was Renault who threw it away”. Not that Prost escapes unharmed from Piquet’s uncompromising wrath. In particular, he spoke out bitterly against his rival’s behaviour at Adelaide in 1989, when the circuit’s virtually non-existent drainage failed to cope with a pre-race monsoon. Following some worrying incidents on the puddles during a special set-up session, several leading drivers, among them Prost, solemnly told TV commentator Barry Sheene that they intended to boycott the race. “Usually I never say anything bad about Prost, because I like him”, Nelson told me at the time. “But he was the one who screwed us completely at Adelaide. We were a very strong group: we had six or seven drivers who said, ‘we will not start this race.’ But Prost turned around, without saying anything, went to his car and sat in it. After that, everybody was dead, everybody went to their cars. Then he did one lap and stopped. Why? Because he had already won the championship and had nothing to prove. That was very brave of him …”. That is an over-simplification of the alarming events in Adelaide, because the race was actually red-flagged after two laps and Prost didn’t so much quit as decline to take the restart. But Nelson’s assessment is still valid, because his worst fears were confirmed when both he and Ayrton Senna, blinded by the spray, escaped serious injury by inches in separate collisions. Piquet hit Piercarlo Ghinzani’s Osella in the watery gloom and he was lucky to get away with nothing worse than concussion. It is the toxic rivalry with Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell that is most clearly recalled by Nelson’s detractors, and so great was the conflict with his countryman back home in Brazil that it commanded the headlines and even the makings of a bitter court case. Although the two men had been trading disobliging remarks ever since Senna’s debut season in 1984, TV Globo’s veteran reporter Carlos Galvão Bueno says that the antagonism was essentially light-hearted, at least until 1986. Throughout that season Senna had been accompanied to most of the races by a younger fair-haired man known to all as ‘Junior,’ whose only official function appeared to be helmet guardian. In the off-season a reporter from the Jornal do Brasil informed Nelson (who has always deliberately avoided reading newspapers) of some comments about him that Senna had made in print. Senna had probably only been teasing, but Piquet, for whatever reason, responded with a barbed insult (“Just ask him why he doesn’t like women”) that instantly found its way on to front pages across the country. Galvão Bueno, always a close and trusted friend of Senna and the family, is a respected journalist with his nose close to the ground. He was therefore well aware that Junior’s presence so close to Ayrton, and perhaps the fact that they sometimes shared a bedroom, had raised questions about the driver’s sexual orientation. “I know Piquet claims that I suggested to the family to ‘get rid’ of Junior”,he told me recently,“but it’s not true. What I can say, though, is that I advised them to be careful”. Today, of course, the sexuality of anyone in the public eye is of little concern to most of us, but that was not the case 30 years ago, and even less so in Brazil’s often intolerant, macho environment. While it is easy to condemn Piquet’s remark to the journalist as ugly and prejudiced, Senna in turn seems to have been desperately anxious to dispel any doubts about his sexual orientation. It became known that he had contracted an attractive female model to accompany him to some races and sponsorship appearances. Later, the Brazilian press drew attention to numerous other outings where he was photographed arm-in-arm with female celebrities who weren’t seen with him again. For what it’s worth, the evidence that has emerged suggests that Senna, though cautious about making friends from the racing world, nevertheless formed close and sometimes intimate relationships with people, male and female, who were not involved in the sport. Despite strong evidence to support this supposition, it is emblematic of the loyalty he inspired that in the 20 years since his death only one or two of the people with whom he was involved have sought to benefit materially from their intimacy with him by talking to the press.

Piquet came to the track locked in Bernie’s boot. Date published: March 30 2020. Ex-Formula 1 boss Bernie Ecclestone has recalled his first memories of Nelson Piquet arriving into the sport, 40 years on from his Formula 1 win.

Nelson Piquet celebrates his first F1 win at Long Beach in 1980.

Monday, March 30, 1980, saw Piquet record his first career win for Ecclestone’s Brabham team at Long Beach. He would go on to win another 22 races and land three World Championship titles in process.

Bernie Ecclestone, owner of the Brabham Grand Prix team, left, talks with Nelson Piquet as he sits in his car on the starting grid for the Dutch Grand Prix as Piquets wife, Sylvia Piquet, right, looks on at the Zandvoort circuit in the Netherlands, on Sunday, August 28, 1983. Piquet was married to Sylvia Piquet (maiden name Tamsma), the mother of F1 GP driver Nelson Piquet Jnr. Photo by Bryn Colton / Getty Images.

Ecclestone has always had plenty of stories to share about all 33 drivers who became World Champions and, with Piquet, he was given a very early indication of just how committed the Brazilian was to reaching the pinnacle of motorsport.

“When we found Nelson in Brazil, he came to the track locked in the boot of my car,” Ecclestone told PA Sport.

“We didn’t have any passes for him but Nelson didn’t care. He was old school. He would clean the car. He would pitch in with the mechanics”.

“He was willing to sleep on the floor if he had to. He would do whatever you wanted. He was desperate to be in Formula One.”

“When he came to England, he didn’t know where he was going to stay, so he told me he would happily sleep under the truck”.

“So, on the first day of testing in 1979, I said to one of our mechanics, Bob Dance: ‘put a sleeping bag under the truck and tell Nelson that is where he is sleeping. Then we will see if he is really that keen.’

“He had no problem with it!”

“Nelson suddenly discovered a good English sense of humour. He was special. He was a super competitor. He wanted to win.”

Ecclestone, who lives in Brazil, says he is still in contact with the 67-year-old.

Kelly Piquet.

Kelly is the daughter of F1 legend Nelson Piquet.

On December 4, 2017, being interviewed by his daughter, Julia Piquet, during an event in which he was honored, in London. Personal photo archive of Julia Piquet.

“He is in good shape,” Ecclestone added.

Finn Valtteri Bottas, on June 30, 2018, shortly after taking pole at the Austrian Grand Prix, taking the Pirelli trophy for his achievement from Nelson Piquet. Photo FIA Dissemination.

“Normally we would have caught up with each other, but with how the world is now it is not easy to do that.”

Nelson Piquet's striking phrases

About Nigel Mansell:

"he's a fast idiot."

"There’s a big difference between us: he likes ugly women, I like beautiful women."

"When I discovered something different in my car (Williams), I spoke to the engineers at the last minute, so there was no time to copy to his car."

“I almost had an orgasm when I saw Mansell stopped" (when the Englishman let his Williams "die"), celebrating in advance on the last lap of the Canadian Grand Prix of 1991. The race was won by Piquet, who was second.

About Rubens Barrichello:

“he can sometimes do fast laps, especially in training, but at a race pace he is usually a second slower than the best.”

Cordial dinner in the 80's between Ayrton Senna and Nelson Piquet.

About Ayrton Senna:

"Senna, the best driver? No, Prost was a four-time Formula One champion."

"Who's better, me or Senna? Me, I'm alive!"

About Formula Indy:

"It's a category for retirees, like me."

About death:

"Afraid of dying? I'm not. I'm afraid of being crippled, that's what."

About Gilles Villeneuve:

"Gilles wore a helmet that was smaller than the size of his head, so the helmet compressed his brain.

Nelson Piquet, Brabham.

Curiosities

Before a Formula 1 race, the mechanics noticed a supposed leak in Piquet's car, minutes before the start, already on the grid. They asked the Brazilian if he had noticed any problems when he drove the car from the pits to the track (installation lap) and Nelson said no. Piquet, too lazy to go to the bathroom, had peed in the cockpit and the "leak" ran down the chassis.

Nelson Piquet and Juan Manuel Fangio.

Zico, Nelson Piquet and Pelé in the 80s. Photo by Reprodução.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment