Gian Paolo Dallara, an Italian businessman and motorsports engineer, owner of Dallara Motorsports, said: “Forghieri is the most complete designer ever existed. There are plenty of designers but he made engines also, all kinds of engines, and then he made Formula 1, Formula 2, and then the endurance races and even uphill races, and he competed with Porsche. The maximum”.

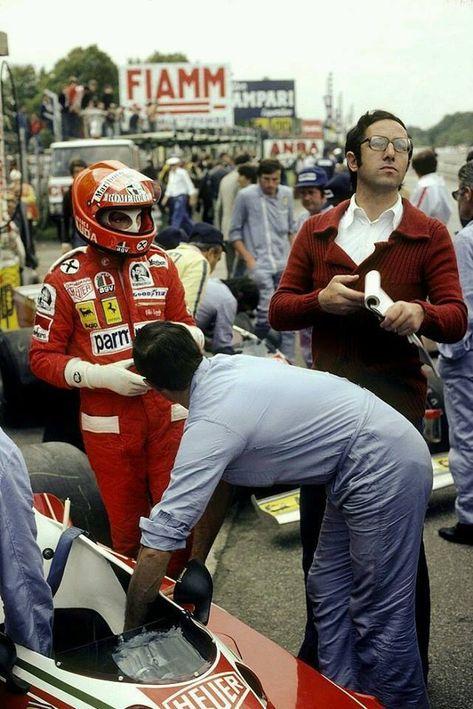

Mauro Forghieri at Vallelunga.

Mauro Forghieri, a lifetime for Ferrari, needs no introduction for those who know just a bit of Formula 1. He is one of the mythical characters of this sport and of the whole auto world. His life, before devoting himself to balsamic vinegar, golf and good readings, has been an adventure. To his ideas the most successful Ferrari from the ‘70s were born.

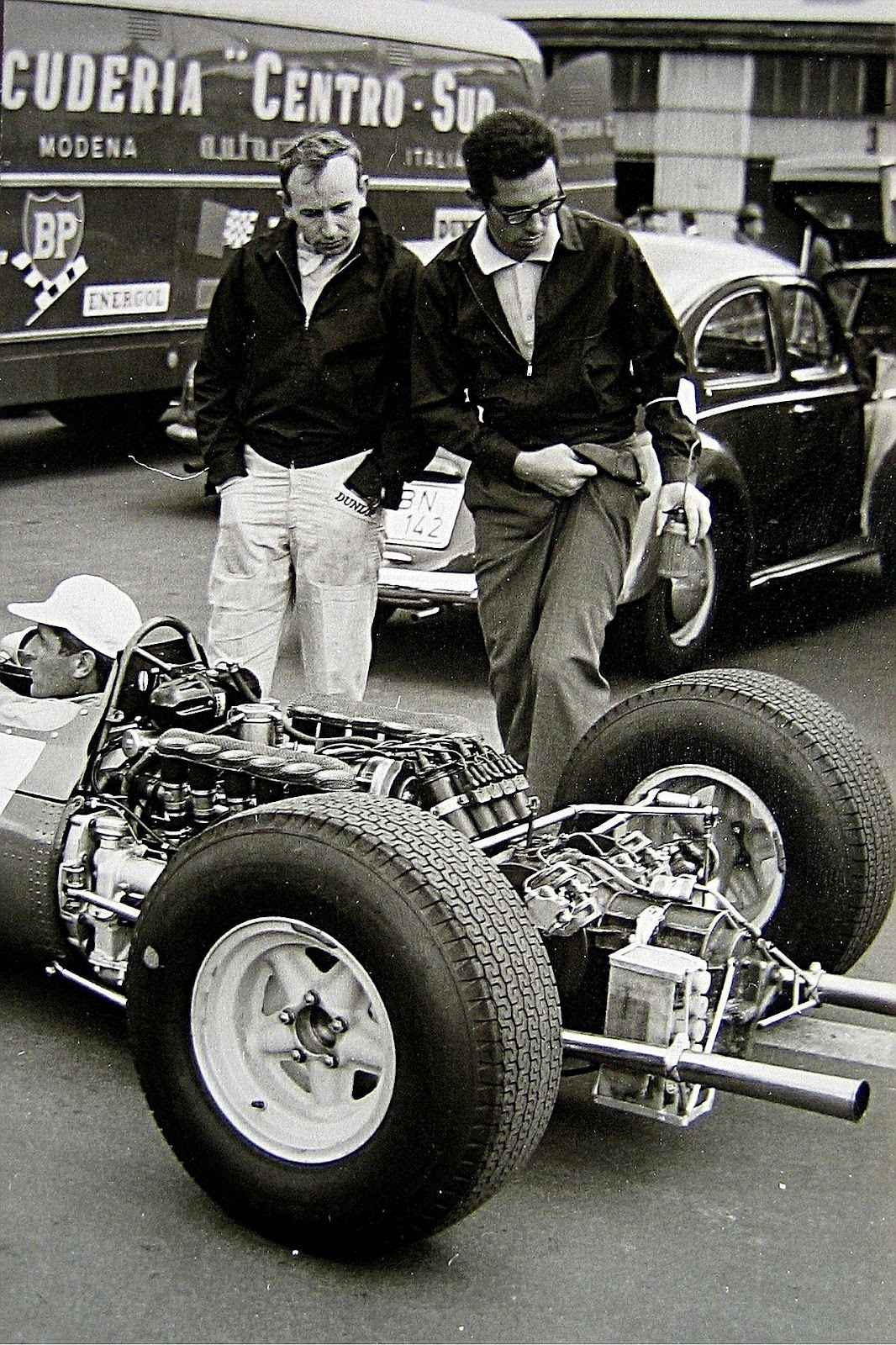

Forghieri (right) with John Surtees inspecting a Ferrari 1512 in 1965 at the Nürburgring.

Under his guidance Ferrari won 54 Grand Prix and the driver's F1 world championship title four times, with John Surtees (1964), Niki Lauda (1975 and 1977) and Jody Scheckter (1979).

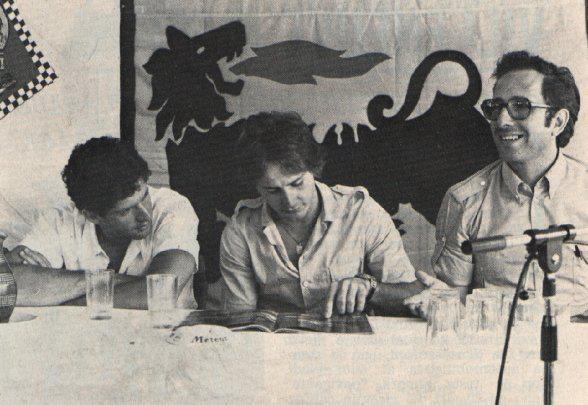

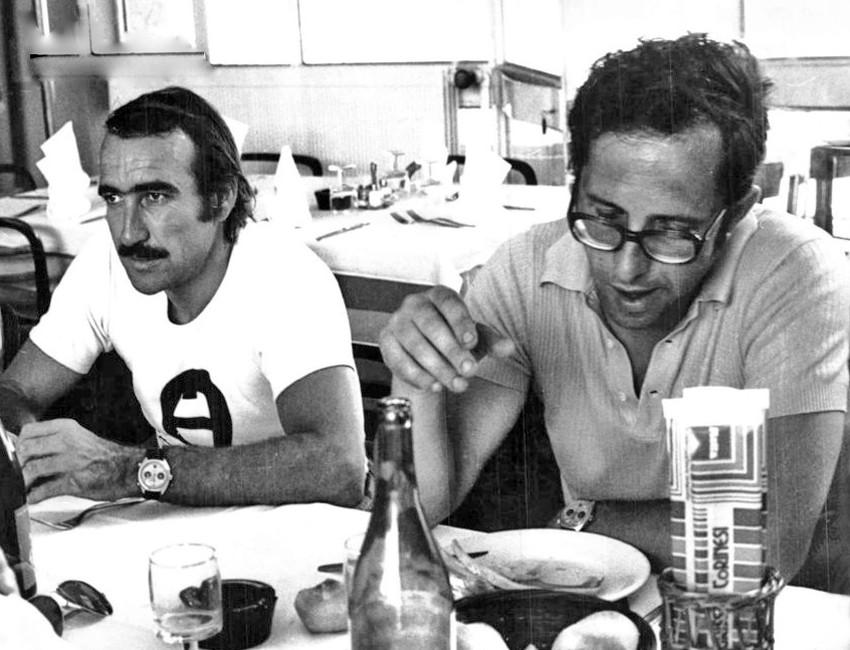

Jody Scheckter, Gilles Villeneuve and Mauro Forghieri.

Ferrari also won the constructors F1 world championship title eight times. In short, a palmarès that ranks him as one of the greatest designers ever. Not an icon of Ferrari legend only, an heritage of the Modenese history and identity. By age 82, a young 82, Mauro Forghieri also reveals a self-mockery and a friendly attitude not very common.

Mauro Forghieri with Gilles Villeneuve.

He was born in Modena on 13 January 1935, the only child of Reclus and Afra Forghieri. His father, a turner, did war work during World War II for the Ansaldo mechanical workshops of Naples. After the conflict, he took up work in the Ferrari workshop in Maranello. Meanwhile, Forghieri completed the Liceo Scientifico and obtained a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Bologna.

Mauro Forghieri and Enzo Ferrari.

Despite his initial interest in aviation design, he accepted an offer from Ferrari, where he had been introduced by his father. He became part of the racing team in 1962, by age 27, with the position of Chief of the Technical Department for racing cars after the departure of Carlo Chiti.

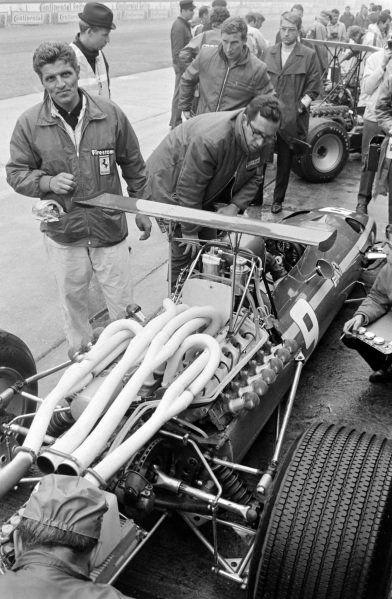

Mauro Forghieri at the 1968 German Grand Prix.

He was later promoted to Technical Director of the Racing Department. In 1970, Forghieri designed the Ferrari 312 series (consisting of the 312 and 312B formula one cars and 312P and 312PB sportscars). He also designed the first transversal automatic gear and Ferrari's first turbo-compressed engine.

Initially Forghieri is responsible for engines but, as time goes by, is involved on other mechanical areas also: he’s the one who, for instance, improves the stability of the legendary 250 GTO in the fast sweepers, working on the rear axle.

Mauro Forghieri at Zandvoort in 1968 with Carlos Reutemann. Photo by Verhoeff, Bert / Anefo.

In 1968 the Modenese engineer’s ideas start to bear fruit even in F1: at the Spanish GP was mounted for the first time on a single-seater car a rear alleron, a technical revolution that was going to revolutionize the motor sport world. Ferrari crisis in F1 leads to his temporary ouster, at the end of 1972 season. Within months, however, following the failure of the 1973 312B3 single-seater car, Forghieri was back at command of Technical Department for racing cars, and a long winning streak in F1 started. In 1984, because of some disagreements with Fiat management, he leaves the Ferrari racing department for the research office, to be in 1986 CEO of Ferrari Engineering. In 1987, after an almost 30 years long career at Ferrari, Mauro leaves Maranello. He was a 360-degree designer, engines, chassis, mechanic and also aerodynamics, the longest-serving and fruitful director of Ferrari’s racing department. And even today he still deals with cars and engines.

“Managing to recreate a Ferrari like the one of our time, particularly thanks to Schumacher, a professional as they come. When he understood that the way of working was very different compared to the one at Benetton, with which he had already won two world titles, he took Rory Byrne, Jean Todt and especially the great organizer Ross Brown with him”. The problem of the last seasons, then, was the shortage of another Shumacher? “I’d say yes. If the car has the same problems for three or four seasons in a row, it means it doesn’t develop in the right direction, and it’s driver’s fault. Alonso is a great driver, not a good tester. Every year, when he was given a car, he said everything was perfect, then a few months later he started to speak ill of it. The true champion is the one who manages the team. You can have state-of–the art simulators and the most advanced computers, but who really judges the car is the driver on track”.

Mauro Forghieri, the man of Ferraris. “Ours was a socialist family, we often lived in France, as before the war being socialists wasn’t that funny. My father also had a Franch name: Reclus. He was a man of Ferrari. Before the war it was a group of people, my father, Ferrari himself, Giberti, Luigi Bazzi, to build all the components of Alfetta Alfa Romeo’s engine. They designed and built in Modena, in Ferrari’s place”. “The passion for engines was born when I was a kid, around 10 years old, the war was just over, a severe poverty around, I was particularly in love with pirates sailing ships, in line with the influence of Salgari, Mompracem, etc. There was a friend, carpenter, who’d give me the wood, and I with the knife, the file and various tools, was practising to build. Then, little by little, I started to fall in love with aeronautical engines: turbines and similar. An American sentence concerning the bumble bee, that has a big body and small wings, struck me; it said “according to the theory of aerodynamics he couldn’t fly but as he doesn’t know it he flies anyway”. I had the idea to go to work at Northrop. When I graduated in mechanical engineering in Bologna, after some time Ferrari said to my father: why does your son mess, bring him here, in the meantime he learns. The relationship with the Drake was dialectical. He was there for me even in times of trouble, he did nothing but support me, even when I was probably wrong. I looked a bit too up to the future, as well as my mechanics and designers. When we built a bit too much cutting-edge solutions, that possibly didn’t work, Ferrari didn’t use to back us into a corner. He said: you did it honestly, it’s part of our heritage of attempts, of experiments. I loved him, I consider him an extremely positive page of my life, even though it was a period of terrible sacrifices. Now they say that that was the Golden Age of Ferrari and I’m pleased to have taken part in it. At Ferrari I had to manage great mechanics and great drivers. I let them see that I got angry, but there was even some theatre. A good driver, unfortunately, is not always a good tester. I had some of them who were great testers. One of them was Chris Amon, New Zealander. He never won a GP but was capable to select tens and tens of tires, channelling engineers on their way out.

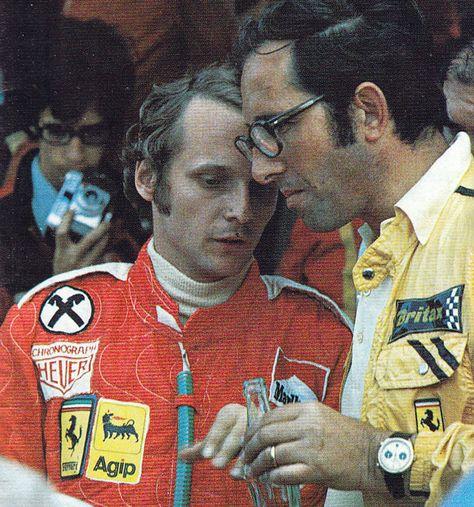

Mauro Forghieri with Niki Lauda.

“Lauda was a great tester, Jody Scheckter became. Even Gilles in tests was not the same we saw in race. He always ran over car’s chances, he was a force of nature. He was all about the race itself, not the championship. For that he probably would never become a world champion, because he didn’t make calculations”.

Mauro Forghieri with Lorenzo Bandini on board his Ferrari 312F1.

“Lorenzo Bandini much more than a driver, a friend. After the disaster in which he lost his life, it was realised that 100 laps at Monte Carlo were insane. When Bandini slid off the track, the car was gutted by a rail that was for getting on a boat. You wouldn’t believe it! Monte Carlo was reduced to 70 laps and tried to become a safe race. Today I don’t go on tracks anymore, I refuse it. I watch races on TV, I record them, I look through them in slow motion, to me is fundamental to exercise my mind, going to take some information”.

Mauro Forghieri, mythical designer of the “Rossa” at Maranello for 40 years, perhaps in her most intensely and exciting time, remembers above all the urge of rebirth of the Austrian pilot, returned to his car after just 40 days since the incident: “Niki was badly beaten, the face scarred, the blood dripping from the gauzes, was struggling to fasten his helmet. He had this amazing fortitude. He came to Fiorano for the test, than at Monza he ran the Italian GP. And he came in fourh”.

Mauro Forghieri and Niki Lauda.

The public was absolutely crazy for that juggernaut renaissance, even though in the end Lauda lost that championship: “yes, in the flood of Japan, at the last race. Actually, they stiffed him”, Forghieri said, remembering the protest of drivers that didn’t want to race and the decision to make a lap anyway for the TV rights. “Drivers instead, that’s just the way they are, when they close the visor of their helmet it’s all about the competition. But Niki knew it, he was expecting it. Only a Brazilian stopped, Carlos Pace”.

Mauro Forghieri and Niki Lauda.

And then Lauda also gave up: “I immediately moved closer to the cockpit. I thought a malfunction”. He said in his basic Italian: “Mauro, I fear, I not racing, I finished”. I answered with a sentence that was a tribute to his courage: “Niki, we’ll say to the press the car broke down”. I wanted to save his act.

Mauro Forghieri and Niki Lauda.

But Lauda was strict: “No, you say truth, I fear”. “He lost the championship by one point, for the benefit of James Hunt”.

By age 27 technical responsible of the most famous team in the world, to make you weak in the knees. “You simply have to do your job, the technician. Do your job, I’ll take care of the rest”, the commendatore Ferrari said, obviously in Modenese dialect, at the time the official language of Maranello’s world. “There were no English back then and, if there should have been one he’d have seen like a rare fish”. Known or unknown events have filled thousands of pages written by the greatest journalists, such as Enzo Biagi and Enrico Benzing, always searching for some unknown implication to look at news of the “Scuderia”, that is more newsworthy, perhaps, when it loses. “We were 167 back then, including Ferrari and his chauffeur Peppino and had to stand up to all and in all areas, because races were advertising the road cars, the GT brought money to race; everything was down to the bone, expenses inspected up to the last dime, everybody went along on the mission, a big family, rowing in the same direction. There was an innate feeling of belonging to the team, to the factory. No incentives were needed, we did our best to win, ready to console each other in defeat”. We ate sandwiches and, secretly, a bit of Lambrusco, are we from Modena or not?” His nickname, when into the pits he was passing by discussions with drivers, to orders to mechanics, to men working on tires and then timekeepers, wives and girlfriends of drivers to manage, battles on regulations with the stewards, was “Furia”. Great worry the small staff, restricted budgets, while competitors started to have more and more resources: “even to have a pot to cook spaghetti in the back of the pit was an achievement, awarded because of the money saved on traveling expenses”. There’s a day no one could forget: on 8 may 1982, at Zolder on board his Ferrari, the little big guy Gilles died.

The man in blue standing is Mauro Forghieri, the chief designer of the 312 Series.

Actually Villeneuve died 2 weeks ago, at Imola, when his team mate Didier Pironi stole the victory from his grasp in front of a crowd that cheered the Canadian, also because from Ferrari sporting director, at the time Marco Piccinini, weren’t passed on to drivers precise information concerning the behaviour on track. Piccinini? Withering and trenchant judgment: “Ferrari was now an old man, he became a sort of caretaker of the Commendatore and told him what he wanted. Ferrari would have never allowed “his” Gilles to be treated like that, but Piccinini was ambiguous and ambiguous were plenty of his decisions”. To Forghieri succeeds as leader Harvey Postlethwaite, as talented as humanly amazing and for the first time, except the idea monocoque Thompson proposed by Sandro Colombo in 1973, a foreigner is allowed to work on conception and structural implementation of a Formula 1 Ferrari. From that point on there will be plenty of foreign scientists to manage the technical fate of Ferrari. First and foremost John Barnard, from 1987 to 1990 and from 1992 to 1996, who committed two acts of sacrilege in one shot, moving the technological antenna of the Red to England and preventing mechanics to drink wine at lunch at GP. In between there were the brief kingdoms of Pier Giorgio Cappelli, coming from Fiat Research Center, in 1988, of Enrique Scalabroni in 1990 and 1991 and of the Austrian Gustav Brunner from 1986 to 1987 and from 1993 to 1997. Then the golden age started, the one long-awaited by Montezemolo and Todt, with Ferrari’s technical galaxy in which stars of Benetton provenance shine such as the designer Rory Byrne (“he doesn’t leave Thailand to go to Italy not even for one week-end“, Forghieri said) and the supervisor Ross Brawn, who doesn’t design since Arrows and Jaguar Endurance, but can handle great. With the cycle over, with Byrne who enjoys Asian heavens, remaining as a consultant, Nik Tombazis is Chief Designer since 2006, while Mario Almondo is technical director in 2007, getting the operational direction a year later, while Aldo Costa, at Ferrari since 1995, works as project responsible from 2008 to 2011. Pat Fry in 2010 becomes the new technical director and in 2013 manages engineers, even though in progress arrives, from Lotus James Allison, who quits on 27 July 2016, passing the baton to Mattia Binotto. He’s the first big shock in view of Ferrari renaissance, eagerly desired by Sergio Marchionne (“Marchionne acts like my father”, says Piero Ferrari, Drake’s son).

Any technician of Prancing Horse won as much as Forghieri did. A prankster who for 27 years and 5 months was the other symbol of Maranello, beside Enzo Ferrari. Both Modenese headstrong, bloody, brilliant, complementary, because Ferrari accepted Forghieri’s extensive expertise and the engineer agreed to give his boss the final say. A diabolical synergy that brought Ferrari to dominate in F1 as well as in the fierce battles Sport, with covered wheels, at Le Mans, Daytona, Sebring, against giants such as Ford and Porsche. “Ferrari, Forghieri says, was a man of intuition. He created me and, as opposed to what happened to others, he didn’t destroy me. An exceptional man, hanged on the reality of our land. We had heated discussions. He screamed and I more than him, but in the end we got along well. He gave his collaborators maximum freedom, urging on innovation. I am a technician who thinks straight on data, he did it on feelings, however being often right. He taught me you should never admit defeat, certainly not in advance …”. From 1962 to 1984 Forghieri’s legend was an history of great champions. “Most of all I admired Amon, because of his extraordinary driving skills: he was never lucky but was the only one at the level of Jim Clark.

Mauro Forghieri with Clay Regazzoni.

Then obviously Lauda and Regazzoni, both excellent drivers and testers”. The most complicated relationship with Niki Lauda, in order to lead him as is right and proper. The F1 cars to witch I’m attached are many: the 312 T of Lauda’s titles, Scheckter’s T4 with transversal gear, the 126 C2 of the first world constructors championship of a turbo in 1982 with the fabulous Villeneuve’s victories in Monte Carlo and Jarama”. The greatest technological advance in the history of F1 I think it was, in general, the aerodynamics development. As for me the transversal gear. A life that is a novel. Dogged also by tragedy: “Lorenzo Bandini’s death in Monaco caused me a lot of pain. The same the one of Giunti years ago or the one of Gilles in 1982. I lost plenty of friends”. Very demanding in work, adorated by mechanics, Forghieri wasn’t so highly payed like the designers came up to Ferrari after him or today’s technicians. That’s why he always had other part time jobs, in between a F1 and the other. For instance, he designed diamond cuts, water pumps, furnitures. And among his hobbies he even retouched (well) frescos of Villa Clementina, close to Modena, an inherited house from the 1700s, where he lives for years.

And, at the age of 82, says: “golf and sea help me to relax, but as long as I am physically able I will search for translate into action the things spinning around in my head. Because the computer became master of the world, but without man’s ideas not a thing is stirring. And I have a lot of ideas …”. During the period when Forghieri worked, both the figure of designer and driver were very different from today’s. It was much more valuable the intuition, the pure genius, than the plenty of software and simulators we have today. Who thought of brilliant ideas emerged …. but that’s not true these days. Nowadays there’s a regressive flattering of Formula 1, so that it gets to have kids-drivers, unbelievable in the past, cars controlled from the pits through computers and software ….. The brilliance has been weakened by machine, the driver has not much to do, he’s a human robot …. There’s shortage of genius of improvisation like it was Senna among the drivers and Chapman and Forghieri among the designers.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment