Imola is like Ferrari, it cannot be described, you have to live it. Each curve tells us a story and the music is that of the Ferrari V10. Imola kidnaps you, hugs you in its own way. It is a treasure trove of memories of an ancient world, which no longer exists. A silent witness to such touching, moving events. It is impossible to escape its melancholy charm. Time stopped at 1994, everything that happened after seems to be clouded by a dull light. It is the only place in the world where you can greet Ayrton, the only place where he can hear you. Imola cradles him lightly in its safe arms, shelters him from the passing of time.

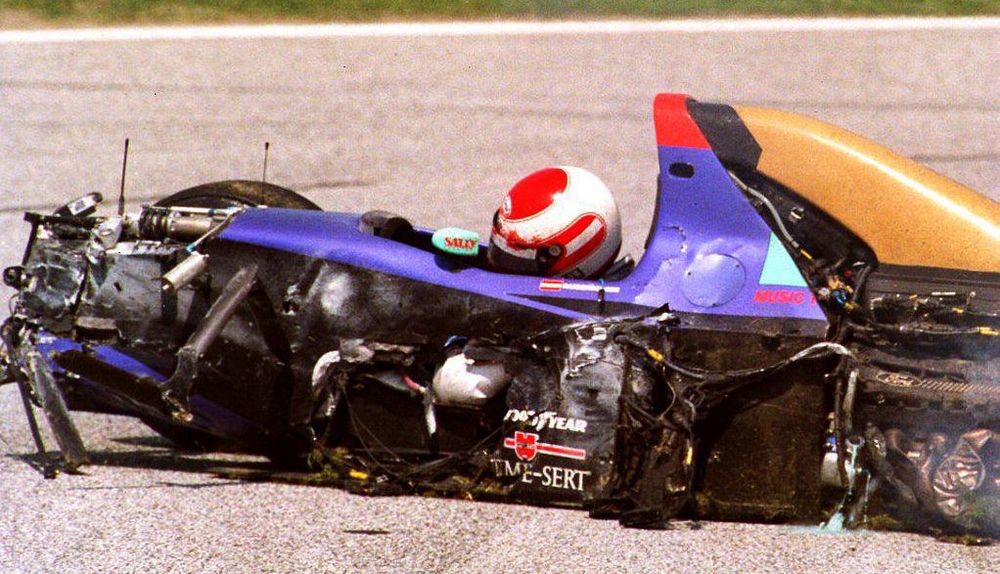

F1 San Marino GP 1994. Ayrton Senna, Williams FW16.

I was there that day in 1994, I saw Ayrton Senna’s last lap. Only after the race the severity of the accident was understood, no one could believe it. It was a discreet but equally inhumane farewell. The awareness of life.

“There are no small accidents on this circuit.” Ayrton Senna, talking about Imola.

"If the crash at Imola '94 did not happen, we all will be fighting for second place." Michael Schumacher.

An awesome track with significant history, Imola is a myth of engines. It let you miss your childhood. It is one of the few circuits that run counterclockwise and the charm of this unexpected stage of the 2020 world championship lies more in memories than in actuality. It's hard not to fall in love with these curves. It is impossible to forget who raced here.

Photo Gubellini.

The circuit is very fast, located in a magnificent area inside a park and, in the days of the race, it is filled with a very lively crowd, all in "red" color.

Photo Gubellini.

Once the glories of Formula 1 have vanished, Imola experiences a new relationship with the circuit, less hectic and more intimate.

Photo Gubellini.

Photo Gubellini.

The track has become an extension of the city, a meeting and aggregation place.

Even the monuments, which arose along the track and are dedicated to the sad events of 1994, have become spaces fully experienced by the citizens.

May 01, 2019. Thousands of fans in Imola commemorated Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger on the 25th anniversary of their death.

There are many generations of Imola boys who have grown up on the track. Over time, many ways of experiencing this strip of asphalt have been created.

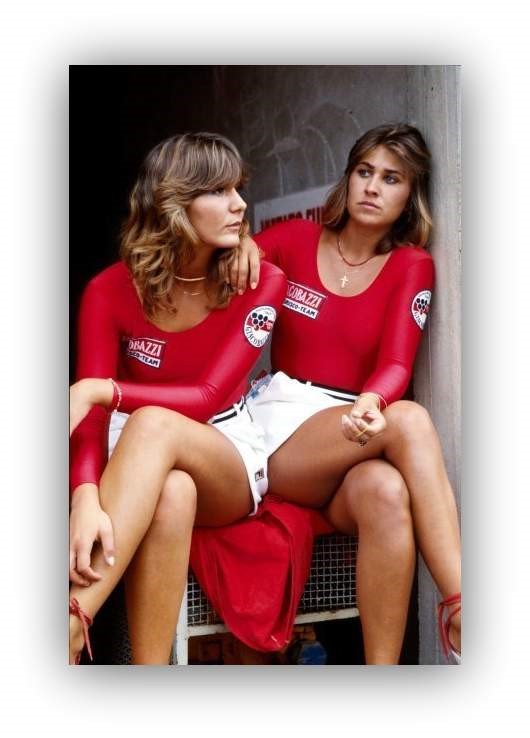

Grid girls.

There were the boys climbing on the walls and on the nets to watch the races and others who worked in the rear, between refreshments, checkpoints and parking lots.

Each person lived this relationship in his own way.

The idea of the circuit came to four friends from Imola, passionate about car racing: Alfredo Campagnoli, Graziano Golinelli, Ugo Montevecchi and Gualtiero Vighi, who combined their enthusiasm with the resourcefulness and managerial skills of Checco Costa. On March 22, 1950, the first stone of the construction site was laid, but the works proceeded slowly and only on October 19, 1952 the track had the real test with a Ferrari 340 sport specially sent by the Drake. The following year there was the sporting baptism with a motorcycle race called Gp Coni. In 1954 it was the turn of the cars with a Ferrari-Maserati duel in the "Conchiglia d'oro Shell" which opened the season of great challenges on four wheels.

Formula One lands in Imola in '63 with an untitled race, won by Jim Clark with Lotus: a day of celebration, ruined by the absence of Ferrari, which had also ensured its presence. In 1965 the track began to take the form of an autodrome, with the construction of the covered grandstand on the finish straight. The circuit, towards the end of the seventies, becomes permanent.

The time has come for the F1 world championship, which debuts on September 14, 1980 with the denomination of Italian GP, one year after the consecration with the name of San Marino GP anticipated to May 3.

It was Enzo Ferrari himself who baptized the track. "I assessed from the first moment that that hilly environment could one day become a small Nurburgring due to the natural difficulties that the construction of the road belt would summarize, thus offering a truly selective path for men and cars. The promoters of Imola felt comforted by my opinion. In May 1950 they began to build… A small Nurburgring - I repeated to myself that day as I looked around me - a small Nurburgring, with equal technical resources, spectacular and an ideal path length. This belief of mine has been realized through the decades that have passed since then».

Imola is one of the most iconic tracks in Formula One history, it has a past steeped in jubilation and tragedy.

Austrian Formula one driver Roland Ratzenberger’s accident.

The circuit, in fact, was made notorious by the events of 1994, when Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were killed in separate crashes during a single weekend.

Those traumatic days prompted changes throughout the sport and to the track, which was slowed by the addition of several chicanes.

The popularity of Ferrari ensured more than sufficient interest to sustain two races in Italy. Imola’s circuit was twice renamed in honour of the family. When Enzo Ferrari’s son died, the track was titled the “Autodromo Dino Ferrari”; after the father’s death in 1988 it became and remains, the “Autodromo Enzo and Dino Ferrari”.

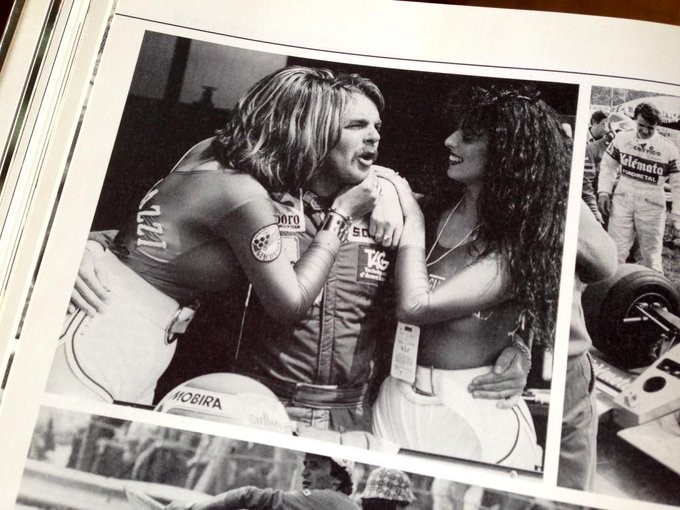

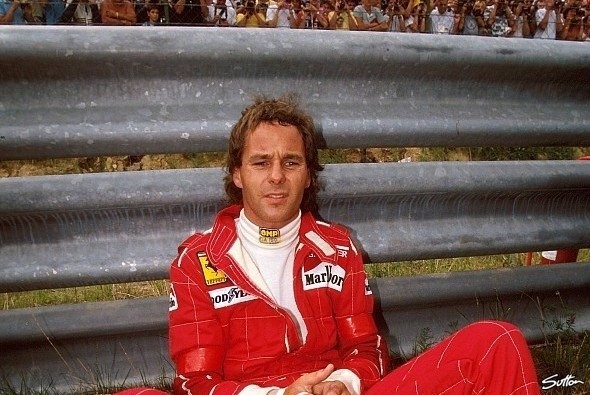

Rio de Janeiro 1982. Gilles poses with Giacobazzi Lambrusco Girls. Photo by Jonathan Giacobazzi.

In 1982, Gilles Villeneuve, a driver to whom a variant of the circuit is dedicated, disputed his last race on this track. "I'll never talk to that guy again," the Canadian said about Didier Pironi, who stole his victory at Imola. A promise sadly kept.

After the terrible events of 1994, the track was heavily revised and made considerably slower. Both the Tamburello and Villeneuve corners, where Senna and Ratzenberger were killed, were replaced by chicanes. The Acque Minerali bend was also reprofiled.

F1 continued to visit the track until the mid-noughties. The Variante Alta chicane was reworked and tightened for the 2006 race, but this was also the final running of the San Marino Grand Prix.

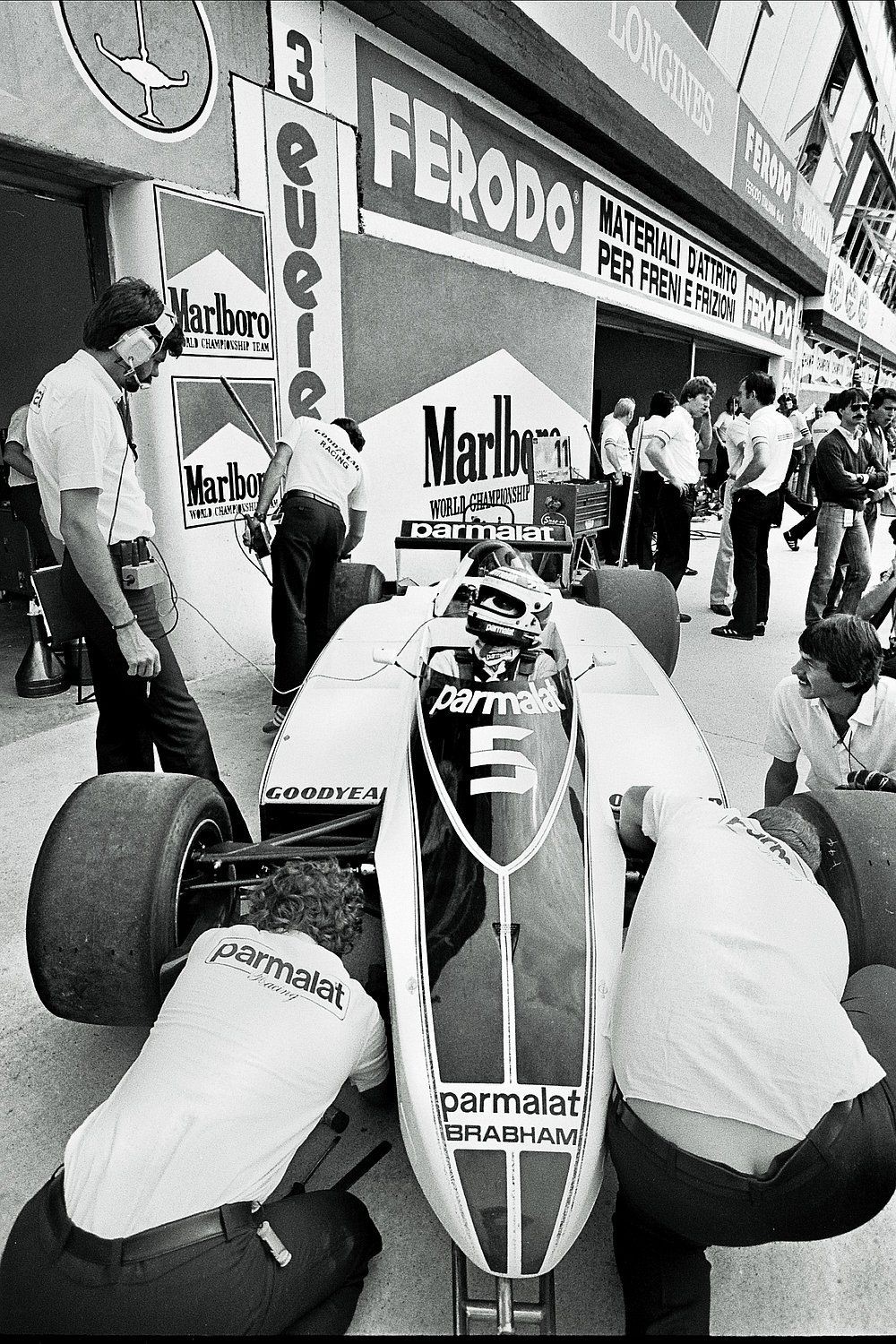

Nelson Piquet, Brabham. Imola, 12.02.1980.

In Imola it was raced from 1981 to 2006, first winner Nelson Piquet in a Brabham, last one Michael Schumacher in a Ferrari.

San Marino GP at Autodromo “Dino Ferrari”, Imola. 1 May 1981, free practice.

Imola GP, 01.05. 1981.

René Arnoux with a blonde female fan in the Ferrari motorhome at Imola in 1988.

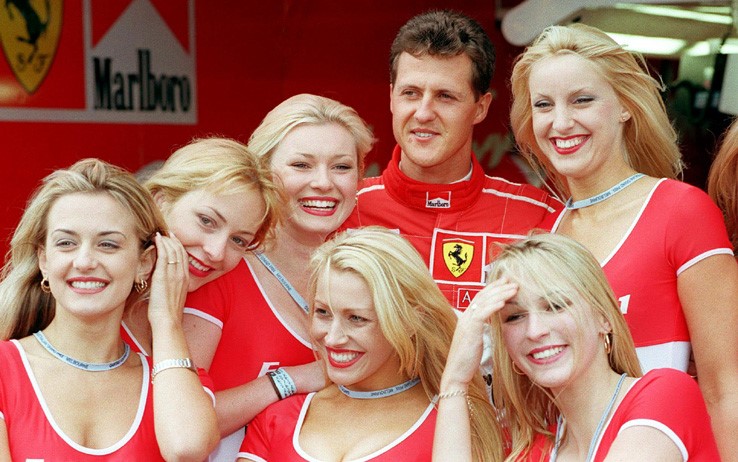

Michael Schumacher appears for the driver parade before the San Marino Grand Prix at Imola on 25 April, 2004.

Michael Schumacher, Imola 2004.

Imola, 24.04.2005.

Imola, 24.04.2005.

No driver has enjoyed more success at the circuit than Michael Schumacher.

Schumacher hostess. Getty.

He did a stunning lap that clinched pole for him in 2006. “You wanted your girlfriend to hug you like Schumacher hugged Rivazza”, some people said at the time.

Jean Todd: "Michael, what does the Tachometer say about the RPM?" Michael: "IT’S OVER 9000!"

Back when also Ferrari strategy was smart.

One moment that should be also mentioned is 2003, Michael Schumacher winning after him and his brother lost their mother after qualifying the day prior to the race.

A piece of the history of motor racing is no longer there. With explosive microcharges the old pits of the Enzo and Dino Ferrari circuit in Imola have been blown up. Photo Gubellini.

After F1 left, the old Imola pit building was demolished and a new start/finish complex built. This allowed for the removal of the Variante Bassa chicane, restoring some of Imola’s lost high-speed nature.

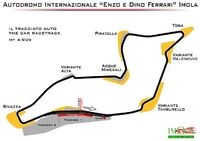

The Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari is universally recognized as an extremely technical track, difficult to read, with complex curves: traveling at a high pace requires a professional skill level.

The circuit and the annexed structures have been part of a redevelopment and modernization plan that began in November 2006 and ended in September 2007. It was curated by the renowned German architect Hermann Tilke, who specialized in the construction of motor racing circuits.

In the summer of 2009 the Nuova Variante Bassa was created, in order to meet the homologation requirements set by the International Motorcycling Federation. This addition, designed to neutralize the slight right-hand bend characteristic of the track for cars, is located in front of the pit lane. In August 2011, the circuit was the subject of the resurfacing work on the road surface, an operation that involved 70% of the track.

Formula 1 2020 at Imola, qualifying session.

During the 2020 F1 season, which was heavily disrupted due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the championship announced it would return to Imola as one of a group of new events arranged to replace cancelled races.

Imola, paddock girls, December 2020.

The first F1 race at Imola after 14 years would be called the Emilia-Romagna Grand Prix.

A city and its racetrack. That is, Imola and the Enzo and Dino Ferrari circuit. On the day when Formula 1 racing cars return along the banks of the Santerno river, photographer Fabio Gubellini dedicates a long reportage to the almost umbilical relationship between the city and the engines. Not only - he writes - from the city center it is possible to hear the noises of racing, but "it is possible to distinguish whether cars or motorcycles are racing. And the most trained ears can understand the type of engine. In addition to the sound, a second thing that strikes you when approaching the track is the smell of racing oils and fuels. We can say that these are Proust's “Madeleines” that link the people of Imola to their racetrack".

Formula One rediscovers Imola and its curves, Rivazza and Tosa and its variants, Tamburello and Acque Minerali. Compared to the nineties it is a revised circuit in terms of safety.

Charles Leclerc got to know the circuit in the minor Formulas, like Stroll and a few others. «I raced in Imola only once when I was in Formula Renault. I really like the track and driving here is exciting: there are very technical passages, especially some corners that don't allow for any margin of error. I think drivers who don't know it will love Imola right from the start».

Charles Leclerc after 2020 qualifying. "I love this track, especially in quali, when you get to ride the kerbs a lot more. We struggled quite a bit today with the balance of the car, everyone is very closely matched but looking at the gap to P4 it’s disappointing to see we are three places down. Tomorrow will be tricky, as it’s going to be difficult to overtake. We are starting on a set of soft tyres that has already done two laps in Q2, but after the first stint things should be fine. The race is tomorrow and that’s when the points are scored."

Lewis Hamilton after 2020 qualifying. “This circuit is unbelievable, it’s a classic with amazing history and the speeds that we are going round it are pretty mind blowing; I’m so grateful to be here and to have the performance that we have, which is really remarkable.”

Imola circuit, 1972.

Imola is like Monza, Monaco or Spa, too much F1 history happened on this track to be forgotten and moved on. It deserves to return to the calendar permanently.

An "old-school" circuit, tarmac, grass and gravel, that's all you need.... It really separates the men from the boys, it tests the best and everyone else!

Imola has offered us both incredible excitement and pain. This sacred, mad, dangerous track which has claimed more than a life, is the holy Graal of Formula 1.

GP Imola 2003.

Imola 24.04.2005. Foster's grid girl for Renault.

We loved how the cars would slide on those kerbs at the last chicane in a dance-like fashion, between 1995 and 2006.

Imagine before Senna and Ratzenberger crashed, the track had three less chicanes and you went almost half a lap without lifting off. Once upon a time F1 was an exciting sport.

It’s such a demanding track, where drivers skills are required to survive and it produced a lot of memorable moments.

Lots of F1 fans nowadays only remember Imola as “the track that killed Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger” but they need to understand that it is a fantastic track, the history of Formula 1...

Back in time when even the trophies where beautiful... not the todays garbage. Those trophies were proper ones, well aside from the dinner plate. Although saying that you'd still prefer that over most of the current-gen F1 trophies.

1983-84. Keke Rosberg enjoying Giacobazzi Lambrusco girls in Imola. Autocourse1.

I know the safety, I know the technology I know everything..., but the F1 of the 80s and early 90s with this track were the pure essence of racing.

Vintage Giacobazzi grid girls at Imola circuit.

With these modifications done to the circuit, your grandfather can race on it. The Tamburello could have been "softened" in the event of a going off. Same can be said of the Villeneuve curve. This is why F.1 doesn't excite anymore. More than 90% of the original tracks have disappeared or have been modified to the point of being ridiculous.

It would be cool to see the original Tamburello corner again, but I understand why that will never happen. It was the only corner that was arguably more dangerous than Eau Rouge/Radillon at Spa.

On today's Imola there is a mixed feeling due to the changes designed by Tilke. People used to go to the “Dino Ferrari” to watch car and motorcycle races, when it was still a semi-permanent circuit, with the Acque Minerali curve still an integral part of the internal roads of the park, with the Rivazza curves that were attached to the fence wall because just incorporated into the circuit which, in its development, reached the Tosa with the turns of Tamburello and Villeneuve (until the accident of Gilles it did not even have a name...). Pits have been built where there was the low variant and now it is difficult to read the signs when driving by and it is dangerous for those who signal. The lane is ridiculously long and nothing can be seen from the grandstand of the finish line. The "go" is given in a "dead" area with respect to the pits. They created the podium area in an absurd place, Tilke having rejected the suspended podium (later adopted in Monza and envied all over the world and which will also be replicated in Vallelunga). In the wake of the emotion of Roland Ratzemberger's accident they massacred the track: if they adopt the variant at Tamburello, the variant at Villeneuve is not only useless but is unnecessarily harmful even for Tosa, disheartened by the slowdown and which does not allow for a duel in the braking section. The Minerali were hard and difficult, you had the embankment wall on the left, then moved away from the new design which integrated a chicane and had also created a sufficient slowdown area. Now you can go flat on the way out, since between the track, curb and "run-off area" the trajectory no longer matters. The pits are badly served because there is only the entrance from via Emilia (Rivazza) while the entrance of Viale Dante is always busy. A service bridge should be built from the Marinai d’Italia roundabout, which would solve most of the problems. Jim Clark found the first track fascinating (the little Nurburgring) and Lauda, Senna and Prost, Piquet and Mansell, liked it. Now much of the circuit's charm is lost and those who have in mind the track as it was regret the changes that have denatured it. The low variant brought the cars on the inner side of the track, that is to the left, allowing a clear reading of the warning signs during acceleration and, despite the problems related to performance, traveling the Tamburello flat out was a challenge and a pleasure. However, if you create a variant at the Tamburello, you leave the Villeneuve as it is or, at most, you redraw it closer to the right side, where you have space. Creating a variant there is a shame. After all, they had created a variant at Eau Rouge - a vomit. Luckily they restored the old track...

Passion and Risk Coursing Through the Imola Circuit. May 12, 2016. Alexander S.

The Imola circuit, or the Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari which is its official name, is one of the best known racing circuits in the world, even though it never assumed the position of one of the top venues.

Over the decades, layout stayed almost the same.

Located at the outskirt of the town of Imola, some 40 km from the city of Bologna in the Emilia-Romagna region, this venue is named after Enzo and Dino Ferrari. The famous Ferrari factory is located some 80 km from the circuit, in the town of Maranello.

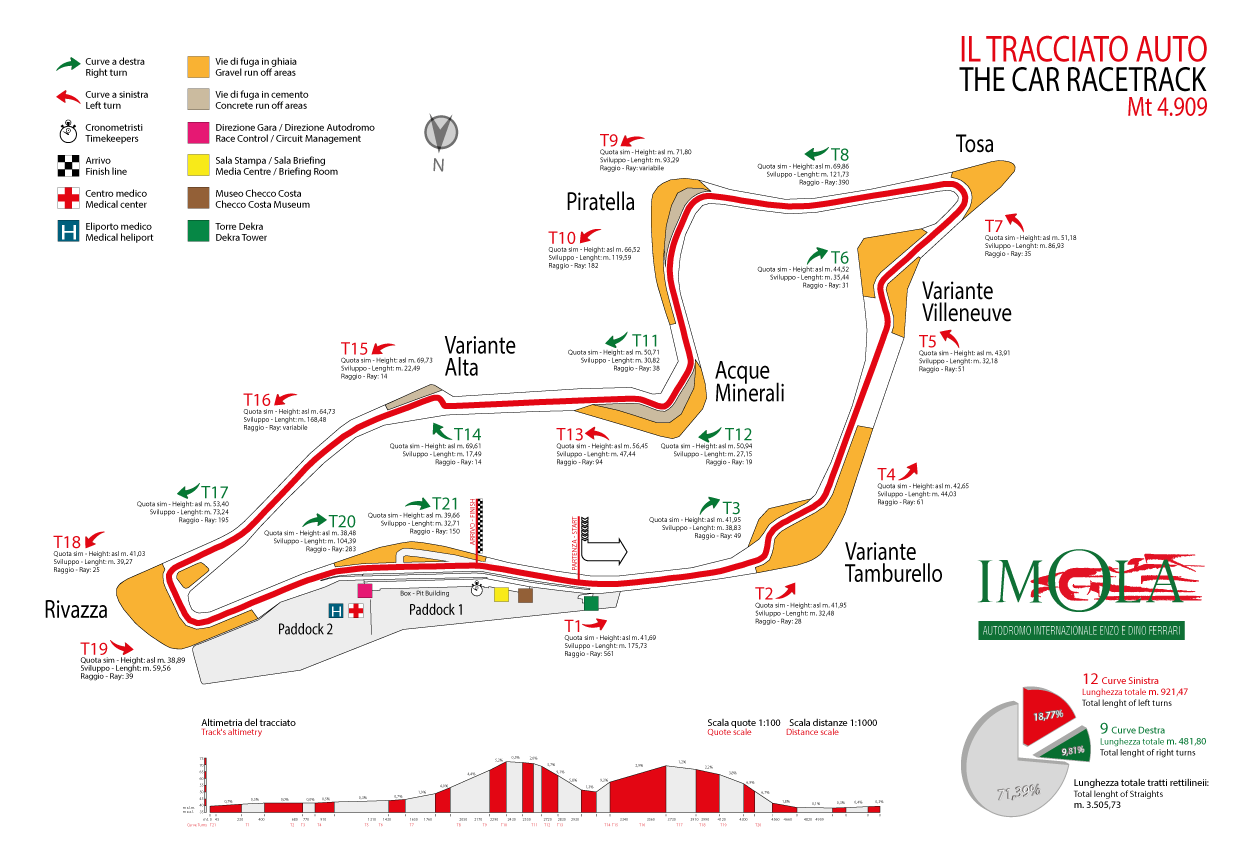

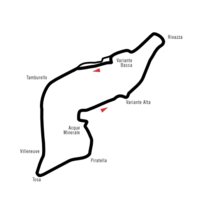

The current layout is 4.909 km long and has 17 turns while the motorcycle circuit is 27 meters longer. Some parts of the track, like Tamburello, Acque Minerali, Variante Alta or Rivazza, have a legendary status among the drivers and the fans. The stands capacity is around 60.000, which is a relatively small number compared to the newer tracks.

Long but inglorious history.

Imola circuit has a long and not so glorious history, after many crashes out of which some were fatal. Interestingly, the area of the circuit has long connections with racing. In the Roman time, there was an amphitheater for the gladiatorial chariot races. The idea of building a modern venue for motorsport was promoted in the 1940s by a group of local enthusiasts. Foundation stone was laid in March 1950 and two and a half years later, the first testing at the new circuit was made by Ferrari and motorbikes manufacturers – Moto Guzzi and Gilera.

Name change.

Since the first day, this circuit was one of the few counter-clockwise ran tracks. Originally, the circuit was named Santino after the river which goes by the paddock side. In 1970, the venue was renamed to Autodromo Dino Ferrari, after Enzo’s son who had died in 1956, while in 1988, Enzo’s name was added after his death. The circuit is also known as Autodromo di Imola.

Safety always was an issue at the Imola circuit.

The first car race was held in 1954, while the first Formula 1 Grand Prix was held in 1963. It was a non-championship race won by Lotus’ driver Jim Clark. After that race, some improvements were made to the facilities.

Grandstand with a roof was built at the start/finish lane, parts of the track were widened and resurfaced. Over the years, many safety measures were implemented, but the layout never was significantly changed.

First Formula 1 Grand Prix.

Finally, in the mid-1970s, the decision was made to make this circuit a permanent racing track. Splice of the public roads and racing sections was merged into a properly surfaced course. The barriers were put all around the track, more stands were built as well the new pit building. In 1979, Imola circuit hosted another Formula 1 Grand Prix, but again it was a non-championship race, won by Brabham driver Niki Lauda. In the following year, Italian Grand Prix was held at Imola for the first time and Nelson Piquet was the winner.

F1 left Imola in 2006.

Since 1981, this circuit hosted Formula 1 San Marino Grand Prix. The race was named after the nearby state of San Marino, because the Italian Grand Prix was held at Monza circuit. The last San Marino Grand Prix was held in 2006 and the event was since dropped from the F1 calendar.

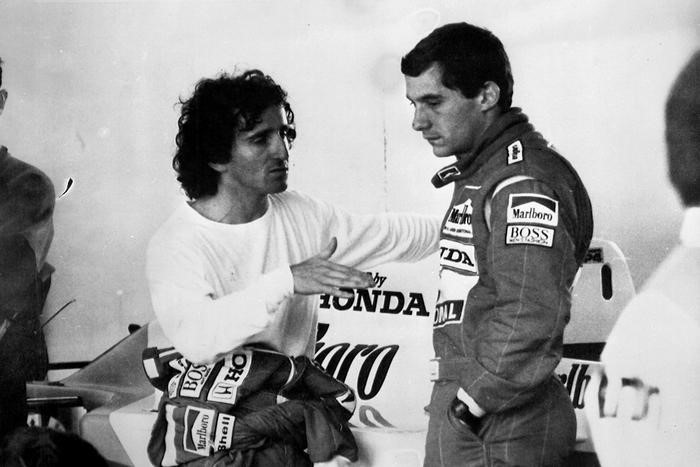

First outing of Prost's new McLaren on test at Imola circuit in 1988. Ansa circuit.

Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna at Imola on March 23, 1988.

Michael Schumacher is the most successful Formula 1 driver at Imola as he scored seven wins while Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna won the race three times.

Sadly, one of the reasons that Imola is so famous is probably the darkest weekend in the history of Formula 1. Two fatal crashes had happened at 1994 San Marino Grand Prix when Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna lost their lives. The Austrian was killed in the accident when he smashed into the wall driving approximately 300 km/h.

A day later, during the race, the legendary Brazilian driver was killed when his car went straight through Tamburello and hit the wall almost at the same place as Ratzenberger. Their deaths caused many safety improvements of the track and, after that, there wasn’t any accident with a fatal outcome during F1 races.

Piquet and Berger were lucky enough.

Even before that black weekend, huge crashes were seen at Imola, a circuit that was always a subject of safety concerns. Tamburello corner always was problematic and Nelson Piquet had a heavy crash there in 1987, while in 1989 Gerhard Berger’s car went on fire and, thankfully to the quick reaction by the track stewards, he was saved but with some burns on his hands.

Modernization and a hope for better days.

Formula 1 had left Imola in 2006, mainly because of the outdated and unsuitable pit and paddock facilities. The venue was modernized and developed since 2007. Pit lane was widened and resurfaced while the garages were rebuilt to meet higher standards of the FIA. Since 2011, the track has the FIA grade 1 licence but the San Marino Grand Prix never was reinstalled to the calendar. A glimmer of hope appeared in 2015 after it was announced that Monza circuit can lose the race after 2016 when the contract with F1 expires.

Except Formula 1, Imola circuit hosted and still hosts various competitions, like WTCC, Le Mans Series, TCR International Series, as well Moto GP and World Superbike Championship. The circuit is also well suited for other purposes and regularly hosts concerts of the Italian and international music stars.

The Imola circuit in Emilia Romagna and, in the background, the city center.

The legendary Imola race circuit. Last update: 28 March 2019.

Among the gentle slopes of Imola hills, it runs the race track of the Enzo and Dino Ferrari Circuit. An asphalt strip that, thanks to its fame and history, has become legendary for fans of motor racing competitions all over the world and becoming a cornerstone of the Emilia-Romagna’s MotorValley.

History.

Italian Gp, 1970 – Jackie Ickx and Pedro Rodriguez at the start. Photo Wikipedia.

In 1950 four Imola-based motor racing enthusiasts finally realized the dream of building a stable circuit close to the city of Imola. The area chosen at the time was the one enclosed between the right bank of the Santerno river, the Acque Minerali’s Park and the first hills, given the presence of some country roads and the special shape of the land.

The story still tells us that the owners called Enzo Ferrari and the Maserati’s brothers to express an opinion on the brand new circuit and that they were thrilled to have such a circuit close to their factories – Ferrari even called it “our small Italian Nurburgring“.

The inauguration took place in October 1952. The first car that had the honor to shoot on the new Imola track was a Ferrari 340 sport and, from that moment on, Imola became synonymous with motor racing.

The Formula 1 World Championship arrived finally on September 14, 1980, first with the name of GP of Italy, one year after with the name of San Marino GP; it will remain there for 26 seasons, making the fortunes of young drivers and marking also the history of Formula 1.

San Marino GP, 1989 – Alain Prost & Ayrton Senna fighting for the win. Ph. Wikipedia.

To mark the history of the circuit also some incidents that still remain in Formula1 history. In 1989, on April 23rd, the Ferrari number 28 of Gerhard Berger goes straight to the Tamburello and crashes at over 280 kilometers per hour. Immediately it is enveloped by flames, but in a matter of seconds (14.98) the men of the security services saved the Austrian pilot. It goes much worse in 1994 during the weekend between April 30th and May 1st: when Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna lost their lives. Following the two fatal accidents, the track was largely modified and the Tamburello and Villeneuve curves disappear, replaced by two variants.

After the loss of Formula 1, followed by that of the MotoGP dating back to 1999, the Circuit was largely modernized for the first time in 2006, with the construction of the structure of 32 boxes, the 50,000-square-meter paddock and the realization of the multimedia project concerning the Checco Costa Museum.

Since 2009, the Enzo and Dino Ferrari circuit in Imola is also a regular leg for the SBK World Championship.

The Imola Race Circuit.

Map. Photo Imola Circuit.

The track presents a layout for both cars and motorcycles and has a length between 4,909 and 4,936 meters, depending on the configurations.

Imola circuit open for pedestrians. Photo Imola Circuit.

During the year, the Imola Circuit hosts plenty of motoring events and provides the opportunity to participate Free Practice Days for cars and motorcycles through registration on the official website.

Among the many other activities of the Circuit, we point out the presence of the Checco Costa Museum, which hosts exhibitions and events on the history of motoring and the Open Days, special days in which the circuit is open to pedestrians and non-powered vehicles.

1992. "Ecological" grandstand of the Enzo and Dino Ferrari Autodrome.

10 Imola F1 facts you might’ve forgotten. Jul 29 2020. By Glenn Freeman, Edd Straw and Matt Beer.

Earlier this year we selected some of the lesser-known tales from the track’s F1 history.

The announcement that Imola will definitely be part of the gaggle of returnees and newcomers Formula 1 brings in to create a full 2020 calendar adds a venue with huge F1 heritage back into the world championship.

The n. 27 Ferrari in action at the ‘variante bassa’ before the pits during the 1982 San Marino Grand Prix.

No consideration of Imola’s place in F1 history can avoid the tragedies with which the circuit will always be linked – the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger at the 1994 event and also the 1982 fallout between Ferrari team-mates Didier Pironi and Gilles Villeneuve a fortnight before Villeneuve’s fatal accident at Zolder.

Senna’s death was also far from the first horrific crash at the now much-changed Tamburello circuit, with the warnings from Nelson Piquet and Gerhard Berger’s fortunate escapes in 1987 and ’89 not heeded.

But Imola has been the scene of many happier F1 occasions too and some very unusual ones.

We’ve selected some lesser-known memories to mark the track’s return to the F1 scene.

McLaren’s late-1990s recovery began here.

McLaren led just 14 laps in the first two years following the departure of Ayrton Senna. In one stint of the San Marino Grand Prix in 1996, David Coulthard surpassed that total.

Coulthard jumped into the lead with a rocket start, fending off Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari and Damon Hill’s Williams until he made his first pitstop.

Even though Coulthard probably would only have finished third if his car had made it to the end, it felt like a significant moment in McLaren’s mid-1990s rebuilding process and it was the first legitimate spell in the lead of a grand prix for the McLaren-Mercedes partnership.

A pre-qualifier made it to the podium here.

During F1’s pre-qualifying era, simply making it onto the grid was often a big achievement for drivers in the teams forced to battle their way in even before practice.

San Marino, 1991.

At the 1991 San Marino GP – famous for Alain Prost spinning his Ferrari and retiring on the formation lap – Scuderia Italia had a tough time on Friday with Emanuele Pirro failing to escape pre-qualifying.

But team-mate JJ Lehto did make it through and put the team’s remaining Dallara-Judd a solid 16th on the grid.

Then in a race of high attrition, Lehto came through to finish an amazing third behind the McLaren-Hondas of Senna and Berger.

While apart from the McLarens only one driver who had qualified ahead of Lehto – Minardi’s Pierluigi Martini, who finished fourth – made the chequered flag, it was a big result for the team on home soil.

It was also the only podium appearance of Lehto’s F1 career and the only time apart from Stefan Johansson’s 1989 Estoril podium for Onyx that a driver came from pre-qualifying to a top-three finish. – Edd Straw.

Prost and Senna animosity really began here.

Without Berger’s fiery crash in 1989, who knows where the Senna/Prost feud would have truly ignited? It wouldn’t have taken long.

Senna’s start/finish chop at Estoril in 1988 is sometimes considered the catalyst for the rivalry truly exploding, but the relationship wasn’t particularly damaged by that. Imola ’89 wasn’t as dangerous, but in Prost’s eyes it represented betrayal.

At Senna’s suggestion, after he was caught up in a Turn 1 collision in the season opener in Brazil, the McLaren drivers agreed before the race that whoever got away best off the line wouldn’t be challenged into the first braking zone at Tosa. Senna got away well and Prost followed, although unless he lifted on the run through Tamburello it’s hard to say it was his choice not to attack.

The race was red flagged following Berger’s crash on lap four, with a restart from the grid. This time Prost got away like a rocket and moved into the lead. He assumed the original agreement with Senna was still intact, only for Senna to sweep alongside on the approach to Tosa to retake the lead.

A frustrated Prost spun later in the race and didn’t attend the post-race press conference, where – unprompted – Senna mentioned that he’d had to attack on the restart because he feared being overtaken by Mansell’s powerful Ferrari – which was running fifth…

Team boss Ron Dennis took the matter into his own hands by getting the drivers together in private during a test at Pembrey.

Prost’s account of the tense meeting was that he sat quietly while Dennis interrogated Senna. Prost claims that while Senna admitted there was an agreement in place, it only applied to the first start, not the second.

“But more important,” adds Prost in the book ‘Alain Prost – McLaren’, “Ayrton said I had overtaken him! I said, ‘I don’t know how many million people had seen what happened on television’. It took maybe 20 minutes before Ayrton would accept what happened. It was unbelievable.”

While Dennis then told the world the matter was resolved at the next race in Monaco, quotes Prost claimed were given off the record appeared in French newspaper L’Equipe saying he would no longer “have any business” with Senna, who he called “not honest”.

Senna hit back, declaring their relationship “finished”. The war was on. – GF

Williams-BMW’s first win came here.

Williams and BMW didn’t have to wait long to achieve their main goal for 2001. After Juan Pablo Montoya was taken out of the lead when lapping Jos Verstappen at the previous race in Brazil, Ralf Schumacher delivered the partnership’s first win next time out in the San Marino GP.

As well as being Williams’s first win since 1997, it was the younger Schumacher’s maiden victory, sealed in commanding fashion by leading every lap.

The race signified Williams’s return to being a major player in F1. Its upturn in fortunes was the result of a much more ambitious engine from BMW for its second season back. It was also the first win for Michelin, just four races into its own F1 comeback.

Ralf was disappointed his brother Michael couldn’t join him on the podium, having retired from the race, sending large swathes of the tifosi for the exits even though the second Ferrari of Rubens Barrichello was third. But Michael was waiting for the winner in parc ferme afterwards.

The race should also be remembered for a bizarre moment in the early weeks of Kimi Raikkonen’s F1 career. The Finn was initially granted a superlicence on a provisional basis and, in just his fourth race, he slid into the wall at Tosa in strange fashion. It later emerged his steering wheel had come off in his hands.

Afterwards he shrugged: “as far as I’m concerned I put it on correctly.” – GF

One of 21st century F1’s least impressive careers ended here.

Yuji Ide was a driver with victories in Formula Nippon, Super GT and Formula 3 in Japan to his name when he got his F1 break in the second entry of the hastily-assembled Super Aguri team in 2006. But it was his final outing in the San Marino GP at Imola that gained him F1 infamy.

On the first lap of the race, he stuck his nose up in the inside of the Spyker of Christian Albers in the left-hand second part of the Villeneuve chicane. The move was never on and sent Albers rolling through the gravel trap. Albers escaped injury, while Ide continued until a suspension problem put him out.

The stewards took a dim view and hit him with a reprimand, with the FIA subsequently advising the Super Aguri team to bench Ide until he could be given greater test mileage to be better prepared for F1. He was replaced by Franck Montagny, but the FIA subsequently revoked his superlicence. – ES

Hakkinen crashed out of the lead here but didn’t cry.

Mika Hakkinen was rocketing away at the front in 1999 when he lost control on the exit of the final corner and his McLaren speared left into the barriers.

It was the first of two high-profile blunders on Italian soil that year, as he’d also throw it off the road at Monza, again to the delight of the Ferrari home crowd.

Unlike at Monza later in the season there were no tears from Hakkinen, just a matter-of-fact acceptance that he’d made a mistake.

Years later he would compare the two mistakes, saying both were a symptom of him trying too hard to build a lead before the pitstops. Given he was already nearly 13 seconds clear at Imola, it was a needless error. – GF

Mansell’s McLaren career ‘peaked’ here.

Imola was the setting for Nigel Mansell’s long-awaited McLaren debut in 1995. Mansell sat out the first two rounds of the year while McLaren made a wider chassis that he’d fit into and, ahead of its arrival, McLaren boss Ron Dennis joked there was room for a stereo inside it.

Mansell knew from his experience with the tight-fitting MP4/10 in testing that it was a bad car, saying after he’d left McLaren: “if I tried to go 10-tenths, the chances of having an accident were very high.”

He played down expectations publicly for the Imola debut, but later admitted to being “dismayed” that the wider B-spec car “had all the same characteristics and defects as the original”.

Quite what he expected when development time had been dedicated to simply making the car wider rather than faster is another question.

He qualified ninth, just two tenths of a second slower than team-mate Mika Hakkinen and ran as high as fifth. But his race unravelled after a clash with Eddie Irvine and he came home two laps down in 10th.

Amazingly, that was to be the peak of the Mansell-McLaren partnership, which would last just one more race.

Button’s first F1 pole came here.

The 2004 season was comfortably the high point of BAR’s short but eventful time as an F1 team before morphing into first Honda, then Brawn and ultimately Mercedes.

Having steadied its ship since the embarrassment of its 1999 debut and benefiting increasingly from Honda’s involvement and progress, in 2004 the combination of its own gains and the likes of Williams and McLaren in particular going off-course with their designs meant it emerged as the most competitive Michelin runner for the majority of the season.

The unfortunate thing for BAR and its lead driver Jenson Button was that this was a year when Ferrari and Bridgestone were a league apart. BAR may have been second in the constructors’ championship, but it went winless all year – Renault, McLaren and Williams managing to capitalise on the three occasions all season when Ferrari left a chink of light for the opposition to slip through.

But at Imola in round four, there was real hope for Button and BAR as they stormed to their first pole by 0.258s over Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari.

The two cars left the rest of the field standing through the opening laps, before the suspicion that the BAR may have benefited from a lighter fuel load (in the era when qualifying was done with first-stint race fuel) was proven by Button coming in two laps before Schumacher.

The Ferrari, which had lurked on Button’s tail in the opening laps, was then fully unleashed and rejoined with a lead Schumacher turned into another unchallenged victory. But second from pole for Button still made this the high point of the season when he proved beyond doubt he could cut it in F1 after the stumbles that had followed his sensational rookie campaign. – Matt Beer

25% of Arrows’ F1 podiums happened here.

When asked to think of venues synonymous with Arrows F1 success (not a question asked often, admittedly), you might go for Kyalami – where Riccardo Patrese nearly won in the team’s controversial first season in 1978 – or the Hungaroring, scene of Damon Hill’s heartbreaking near-miss in 1997.

But actually Imola ranks as a – relatively – happy hunting ground for F1’s long-term underachiever, with two of its eight podiums happening here.

The first was in an era where it was a regular threat for victory. Arrows made an excellent start to the 1981 season, leading from pole with Patrese in Long Beach and taking third behind a Williams 1-2 at a very wet Rio.

At Imola, Patrese was the main threat to the early Ferrari 1-2 in another damp race and once leader Villeneuve had made a disastrously premature switch to slicks it was the underdog Arrows chasing Pironi for the lead.

Ultimately eventual champion Nelson Piquet’s Brabham overcame both as Piquet recovered from an early ninth place to victory. But Patrese finished under five seconds behind in second place, fending off Carlos Reutemann’s Williams as Pironi’s tyres faded.

That placed Arrows third in the constructors’ championship. But Imola was as good as it got – big teams finding their feet (and getting their turbos sorted) plus an unsuccessful mid-season switch from Michelin to Pirelli tyres meant Patrese’s third place was the last time the team scored all year.

Four years later, Arrows finally returned to the podium at the same track – though this time much further from victory. Thierry Boutsen was lapped by both on-the-road winner Alain Prost’s McLaren and the Lotus of Elio de Angelis, which picked up victory when Prost was disqualified for being underweight, which elevated Boutsen to second.

This race was the point at which the fuel limits of that part of F1’s turbo era reached an almost comical point. Cars running dry or slowing dramatically had been a regular feature of the rules since they arrived for 1984, with Imola’s uphill charges out of slow corners making it a tough one on consumption.

Both Senna’s Lotus and Stefan Johansson’s Ferrari ran out of fuel in the closing stages while leading (from 16th on the grid in Johansson’s case) and even Boutsen pushed his car across the line on foot as its BMW engine ran dry. – MB

Frentzen actually won in a Williams here.

Coloured by furious fans’ perceptions of Williams’s actions in sacking 1996 champion Hill to make way for him, Heinz-Harald Frentzen’s Williams stint was not as bad as it was portrayed at the time. And at Imola it looked like it was about to blossom into what Frank Williams and Patrick Head had hoped for when they signed Frentzen from Sauber.

After the embarrassment (1.7s off team-mate Jacques Villeneuve in qualifying) and misfortune (brake failure in a much more encouraging race) of Melbourne and the huge embarrassment of Interlagos (a very distant ninth place finish), Frentzen actually looked set for his Williams breakthrough at Buenos Aires – where his clutch failed as he hassled Villeneuve for the lead.

Then at Imola he shadowed Villeneuve and Michael Schumacher through the first stint, jumped both by running longer at his first stop then held the Ferrari at bay for a very assured race win that proved to be a complete one-off.

In between episodes of bemusement at the Williams and the Goodyear tyres, mechanical misfortunes and hapless first-lap tangles, Frentzen did show promising form on other occasions in 1997. But Imola was the only place where he pulled everything together, his luck held and he actually won for Williams. – MB

Remembering the last time that Formula 1 raced at Imola. By Károly Méhes. October 27th, 2020.

San Marino GP at Imola in 2006. Károly Méhes looks back on his last visit to Autodromo di Imola, a circuit he visited regularly for the San Marino Grand Prix. Imola is making an unexpected return to the F1 calendar as the host of the 2020 Emilia Romagna Grand Prix on November 1. Images © Károly Méhes.

From my first visit in 1993 to my last in 2006, my Formula 1 year nearly always started with a trip to Emilia Romagna. My yearly routine was the same: I would leave my home in the south of Hungary at around 6am and drive through Croatia and Slovenia, crossing the Italian border at Trieste before hammering down towards Bologna and Imola. If the traffic wasn’t too bad, I would be strolling into the Paddock around 3pm. Always held in April, the San Marino Grand Prix opened the European Formula 1 season and often attracted celebrities and big names – it was not unusual to bump shoulders with Piero Ferrari or Luca di Montezemelo in the overcrowded Paddock.

Remembering Gilles Villeneuve.

Aside from the usual Formula 1 activities, my days were busy at the final San Marino Grand Prix in 2006 – starting with a ceremony at one of the main squares in the nearby town of Imola. The square was being renamed after Gilles Villeneuve, the French-Canadian driver who lost his life in 1982 and achieved the status of legend. Perhaps even more so in Italy than his native Canada. Among the invited guests was Gilles’ widow Joanna and his son Jacques, who was still racing with Sauber. The Ferrari management duo of Jean Todt and Stefano Domenicali also turned up to pay their respects to one of the team’s most well-known drivers as a large crowd gathered around Gilles’ Ferrari 126CK, which he had taken to victory at Monaco and Jarama in 1981.

After paying my respects, I made my way to the nearby town of Brisighella, where the late Ferrari ace Lorenzo Bandini had been born in 1935. It was that time of year when the Trofeo Lorenzo Bandini (established by his sister Gabriella) was presented to the most promising driver of the previous season. Mark Webber took the honors in 2006, while Scott Speed was also recognized. The presentation of the trophy is always a big event in the town, attended by the mayor and other dignitaries. After the speeches, we retired into the mild spring evening for pasta and Lambrusco.

Italian drinks company Martini also made a welcome return to Formula 1 as a minor sponsor of Ferrari in 2006 after more than 25 years out of the sport. To celebrate, they organized a party in the Paddock and invited along the former management of Brabham – the team for which they had been the title sponsor in the mid 70s. Bernie Ecclestone, Gordon Murray, Herbie Blash and Charlie Whiting (the latter two were then part of the FIA) were presented with a light blue jacket commemorating the Brabham-Martini partnership, which they proudly wore throughout the evening. But past was nothing compared to the present when Michael Schumacher and Felipe Massa appeared! The Brabham folks were immediately forgotten as everybody pushed forward for a handshake with the current Ferrari stars.

As for the town of Imola, I have to say I like it a lot. The Autodromo di Imola was constructed in 1953 on the outskirts of the pretty town. Just a 15-minute walk from the Paddock, you’ll find yourself in the heart of the town centre, surrounded by cosy trattorias and bodegas. Most of the shop windows featured some kind of Ferrari-related decorations on race weekend and the atmosphere was electric. It’s a special place that holds a lot of dear memories and I’m excited to see it back on the Formula 1 calendar in 2020.

The Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari is a race track near the Italian town of Imola, 40 kilometres (24.9 mi) east of Bologna. The circuit has a FIA Grade One license.

It was the venue for the San Marino Grand Prix. For many years, two Grands Prix were held in Italy every year, so the race held at Imola was named after the nearby state. It also hosted the 1980 Italian Grand Prix, the Italian Grand Prix usually takes place at the Autodromo Nazionale Monza. When Formula One visits Imola, it is seen as the home circuit of Scuderia Ferrari, and masses of supporters come out to support the local team.

The Imola circuit is basically a road following a small river, the Santerno, with a return looping over a couple of small hills. At almost no point of the original layout was the track truly straight, with made it challenging and a favorite for both drivers and spectators.

The original layout of the Imola circuit featured several flat-out sections connected by tight hairpins. At first, the run from Rivazza and Tosa was flat out, as was the run from Acque Minerali to Rivazza. This meant that drivers reached very high speeds through Tamburello and Villeneuve. From the start line, the circuit ran through a quick left-hander (Tamburello) which was taken flat-out. From here, a short straight leads to a flat right-hander (Villeneuve) and tight left (Tosa). Following a short straight and a quick sweeping left hander lies Acque Minerali, a tight right-left-right chicane. Over a crest is the right-left chicane, Variante Alta. Then down the hill to the double left hand Rivazza turns. Then back up the hill for a quick right-left and slower left-right (Variante Bassa) and on to the finish line.

The venue returned to the Formula One calendar during the 2020 season to help the sport fill calendar gaps caused by cancellations of other races due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the race at the circuit being named the Emilia Romagna Grand Prix in honour of the region where the circuit is located. This also meant the venue hosted a World Championship race under a third different name having hosted the 1980 Italian Grand Prix and the San Marino Grand Prix from 1981 to 2006.

The track was inaugurated as a semi-permanent venue in 1953. It had no chicanes, so the runs from Acque Minerali to Rivazza and from Rivazza all the way to Tosa, through the pits and the Tamburello, were just straights with a few small bends; the circuit remained in this configuration until 1972.

In 1980 Imola officially debuted in the Formula One World Championship calendar by hosting the 1980 Italian Grand Prix. It was the first time since the 1948 Edition held at Parco del Valentino that the Autodromo Nazionale Monza did not host the Italian Grand Prix. The race was won by Nelson Piquet and it was such a success that a new race, the San Marino Grand Prix, was established especially for Imola in 1981, remaining on the calendar until 2006. The race was held over 60 laps of the 5 kilometre circuit for a total race distance of 300 kilometres.

Imola has hosted a round of the Superbike World Championship from 2001 to 2006 and later since 2009. It hosts the final round of the FIM Motocross World Championship since 2018.

The World Touring Car Championship visited Imola in 2005 for the Race of San Marino, in 2008 for the Race of Europe, and in 2009 for the Race of Italy. The venue hosted a round of the International GT Open from 2009 to 2011. The TCR International Series raced at Imola in 2016.

The 6 Hours of Imola was revived in 2011 and added to the Le Mans Series and Intercontinental Le Mans Cup as a season event until 2016. Since 2017 it hosts the 12 Hours of Imola, a round of the 24H Series.

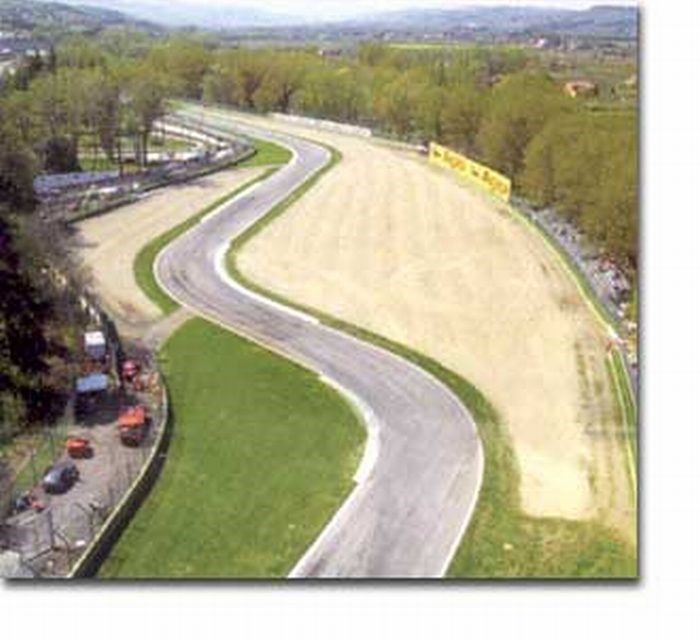

Tamburello curve, Imola.

Tamburello.

Despite the addition of the chicanes to several parts of the lap, the circuit was subject to constant safety concerns, mostly regarding the flat-out Tamburello corner, which was very bumpy and had dangerously little room between the track and a concrete wall which separates the circuit from the Santerno river that runs adjacent to it.

In 1987, Nelson Piquet crashed heavily during practice after a tyre failure and missed the race due to injury.

Gerhard Berger.

Gerhard Berger, Ferrari, Tamburello crash in 1989.

Marshals carry away the rear bodywork of Gerhard Berger’s Ferrari 640 after a crash. Photo by Ercole Colombo.

In the 1989 San Marino Grand Prix, Gerhard Berger crashed his Ferrari at Tamburello after a front wing failure. The car caught fire after the heavy impact but thanks to the quick work of the firefighters and medical personnel Berger survived and missed only one race (the 1989 Monaco Grand Prix) due to burns to his hands. Michele Alboreto also had a fiery accident at the Tamburello corner testing his Footwork Arrows at the circuit in 1991 but escaped injury. Riccardo Patrese also had an accident at the Tamburello corner in 1992, while testing for the Williams team.

The death of Ayrton Senna on 1 May 1994 sealed the fate of the corner being run flat out ever again. To make Tamburello safer, it became a left-right-left chicane instead of a flat out left hander to slow down cars.

1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

29.04.1994, Imola, Barrichello accident.

In the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, during Friday practice Rubens Barrichello was launched over a kerb and into the top of a tyre barrier at the Variante Bassa, knocking the Brazilian unconscious, though quick medical intervention saved his life. During Saturday qualifying Austrian Roland Ratzenberger crashed head-on into a wall at over 310 km/h at the Villeneuve corner after his Simtek lost the front wing, dying instantly from a basilar skull fracture.

The tragedy continued the next day, when the three-time World Champion Ayrton Senna lost control of his car and crashed into the concrete wall at the Tamburello corner on Lap 7. Senna died in hospital several hours after his crash. In two unrelated incidents, several spectators and mechanics were also injured during the event.

The circuit's layout at the time of the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

In the aftermath, the circuit continued to host Grands Prix, but revisions were immediately made in an attempt to make it safer. The flat-out Tamburello corner was reduced to a 4th gear left-right sweeper and a gravel trap was added to the limited space on the outside of the corner. Villeneuve corner, previously an innocuous 6th gear right-hander into Tosa, was made a complementary 4th gear sweeper, also with a gravel trap on the outside of the corner. In an attempt to retain some of the quickness and character of the old circuit, the arduous chicane at Acqua Minerali was eliminated and the Variante Bassa was straightened into a single chicane. Many say that the new circuit configuration is not as good as it used to be as a result of the new chicanes at Tamburello and Villeneuve.

Another modification made to the Imola track is that of Variante Alta, which is situated at the top of the hill leading down to Rivazza and has the hardest braking point on the lap. The Variante Alta, formerly a high-kerbed chicane, was hit quite hard by the drivers which caused damage to the cars and occasionally was the site of quite a few accidents. Before the 2006 Grand Prix, the kerbs were lowered considerably and the turn itself was tightened to reduce speeds and hopefully reduce the number of accidents at the chicane.

The Grand Prix was removed from the calendar of the 2007 Formula One season. SAGIS, the company that owns the circuit, hoped that the race would be reinstated at the October 2006 meeting of the FIA World Motor Sport Council and scheduled for the weekend of 29 April 2007, provided renovations to the circuit were completed in time for the race, but the reinstatement was denied.

Recent developments.

Since 2007, the circuit has undergone major revisions. A bypass to the Variante Bassa chicane was added for cars, making the run from Rivazza 2 to the first Tamburello chicane totally flat-out, much like the circuit in its original fast-flowing days. However the chicane is still used for motorcycle races.

The old pit garages and paddock have been demolished and completely rebuilt while the pitlane was extended and resurfaced. The reconstruction was overseen by German F1 track architect Hermann Tilke.

In June 2008, with most of the reconstruction work completed, The FIA gave the track a "1T" rating, meaning that an official Formula One Test can be held at the circuit; circuits require the "1" homologation to host a Formula One Grand Prix. As of August 2011, the track received a '1' FIA homologation rating after an inspection by Charlie Whiting.

In June 2015, the owners of the circuit confirmed they were in talks to return to the Formula One calendar should Monza, whose contract was scheduled to run out after the 2016 season, be unable to make a new deal to keep hosting a round of the world championship. On 18 July 2016, Imola signed a deal to host the Italian Grand Prix from the 2017 season. However, on 2 September 2016, it was announced that Monza had secured a new deal to continue in hosting the race and Imola's officials took legal action against this decision questioning the legality of government funding awarded to Monza. On 8 November 2016, they withdrew their case. In February 2020, the owners at Imola submitted a bid to replace the 2020 Chinese Grand Prix pending its cancellation as a precaution in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Current layout.

On 24 July 2020, it was confirmed that the circuit would be added to the calendar for the 2020 Formula One World Championship. In a break with Formula One tradition the event at the circuit took place over two days instead of three from on 31 October and 1 November 2020.

Pierluigi Martini and Giancarlo Minardi.

"It's my home track, I was hosting Ayrton". Pierluigi Martini lives next to Rivazza and at Imola he collected a fourth and a sixth place. "Real circuit: what breakings at Tosa". By Mattia Grandi, 17.04.2021.

For Pierluigi Martini, the Formula 1 Grand Prix at Imola continues to be, simply, the home race. Romagnol blood in the veins and residence a stone's throw from the legendary Rivazza curve for the former driver who has been the protagonist of over a decade, from the mid-80s to that of the 90s, in the specialty. The long partnership with Minardi, the joy of a fourth and sixth place on the banks of the Santerno river in the two-year period 1991-1992 and the pain of the untimely death of his friend Ayrton Senna.

Martini, April and Formula 1. It’s an amarcord eve for Imola.

"The period is precisely that of the golden times. I close my eyes and see Tosa and Rivazza overcrowded with people. April was truly the month of Formula 1 in Imola."

The Imola track is in the hearts of the drivers. Can you tell us why?

"An original, authentic track. Always different curves that do not give constant references to the driver. You work on the curbs and with continuous braking uphill and downhill. A beautiful circuit because it is varied, technical and complete".

Pierluigi Martini in a Dallara Ferrari at the San Marino GP. Imola, 17 May 1992.

As a former driver of the specialty, what’s the most difficult point to deal with inside the car?

"The old Tamburello with wet asphalt was crazy. Then the Piratella curve, the descent of the Rivazza and the entry of the fast low variant before the straight. In the current configuration, instead, I say the first variant after the straight because it has a not very linear trajectory. In practice you brake with the car crooked".

What gave you the most satisfaction?

“The attempt to brake for last at Tosa”.

In which sector of the circuit would you watch the Grand Prix?

"At Rivazza".

Joys and sorrows for you on the banks of the Santerno.

"A fourth and sixth place in Formula 1. Lots of successes and podiums in the other categories in which I took part. A bad accident with a broken leg in 1990 and the immense tragedy of the death of my friend Senna".

You opened the doors of your home in Imola to the Brazilian champion.

"During the competitive weekend in the city he arrived at my house not before eleven in the evening. Until then he worked incessantly in the pits. The next morning we were leaving in two different cars, one behind the other. A short ride to reach the entry of the circuit. Indelible memories".

Your ideal format for the Imola racetrack?

"The one that unites history and tradition to young people, in the two and four-wheeled motorized field. Just as in the past, motoring events accessible to all and not only for a select few. It is necessary to recompose the mentality of a possible collective protagonism to also favour the induced".

The opening race of Formula 1 in Bahrain. Mercedes and Red Bull never so close.

"It was only the first round. From Friday to Sunday I saw a Mercedes in constant progression that will grow even more. Red Bull has a great engine and an extraordinary Verstappen. It will be a more balanced world championship than in 2020".

Ferrari has a duo of young drivers.

"A well balanced couple. I really like Sainz."

The return of Alonso.

"Never take champions for broken. With these cars you can be competitive up to 45 years old. But I have a predilection for Raikkonen, an authentic driver, a character".

The young driver who impressed you?

"Tsunoda of Alpha Tauri. I had already guessed it during the pre-season tests at Imola. He drives well, he's mature, fast and consistent."

We conclude with a game. Your podium at Imola?

"Verstappen, Hamilton and Leclerc".

Jean Alesi: "Imola is unique, the South Curve of the fans".

Jean Alesi, Ferrari F92A, Grand Prix of San Marino, Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari, Imola, 17 May 1992. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images.

Jean Alesi drives his Ferrari during the final qualifying session in the San Marino F1 Grand Prix in Imola on 29 April 1995. Mandatory Credit: Ben Radford/Allsport.

"Imola, in the Ferrari tradition, is the meeting place with the red people, the south curve of the cheering, while Monza has always been the North Curve: as soon as you leave the pits you find yourself in the middle of the trees, like racing in a forest. Just after, at the Tosa, it's like entering a full stadium. You hear the screams coming from the hill while you drive, I heard them with the 12-cylinder, let alone now with these less noisy cars. A roar at every lap. At Rivazza, even better. As you come down from the Variante Alta, you see houses, windows and balconies and you feel like you are in a strange place, in the middle of a city. Then, when you enter the Rivazza 2, you see the overcrowded hill and you understand that Imola is unique".

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment