Honda is the history of F1 and in the suitcase of its farewell to the ultimate racing category it takes away an incredible series of touching memories.

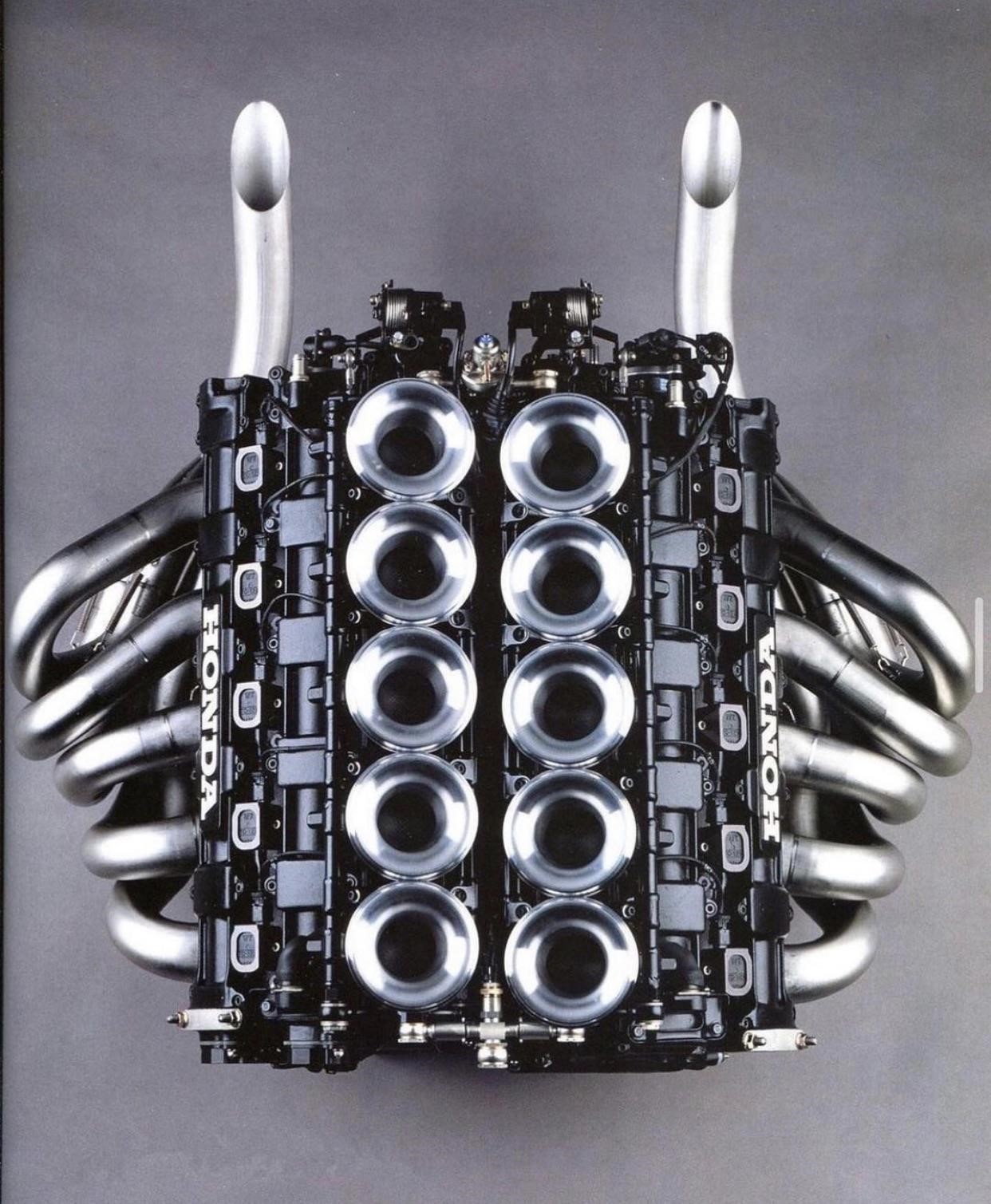

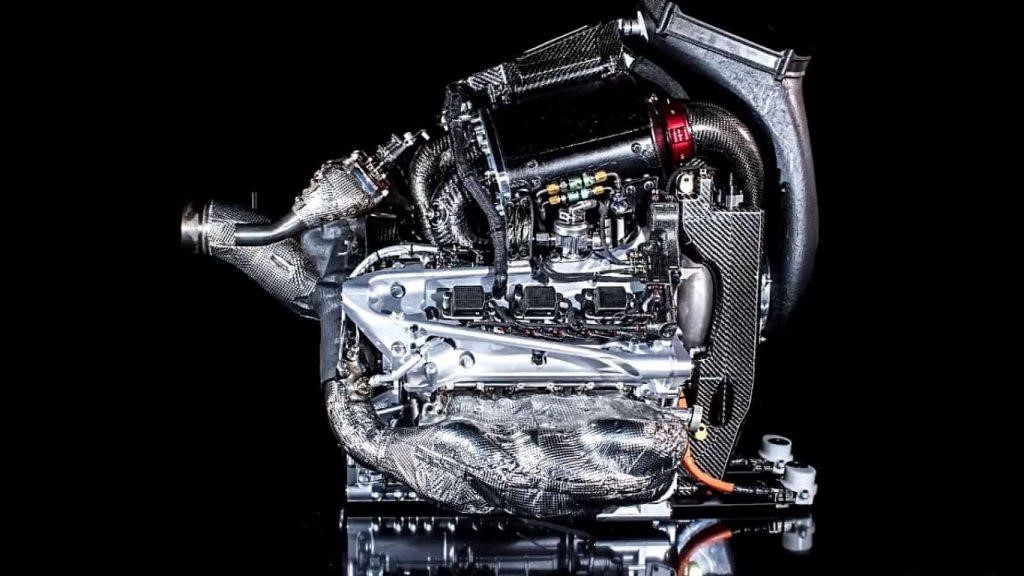

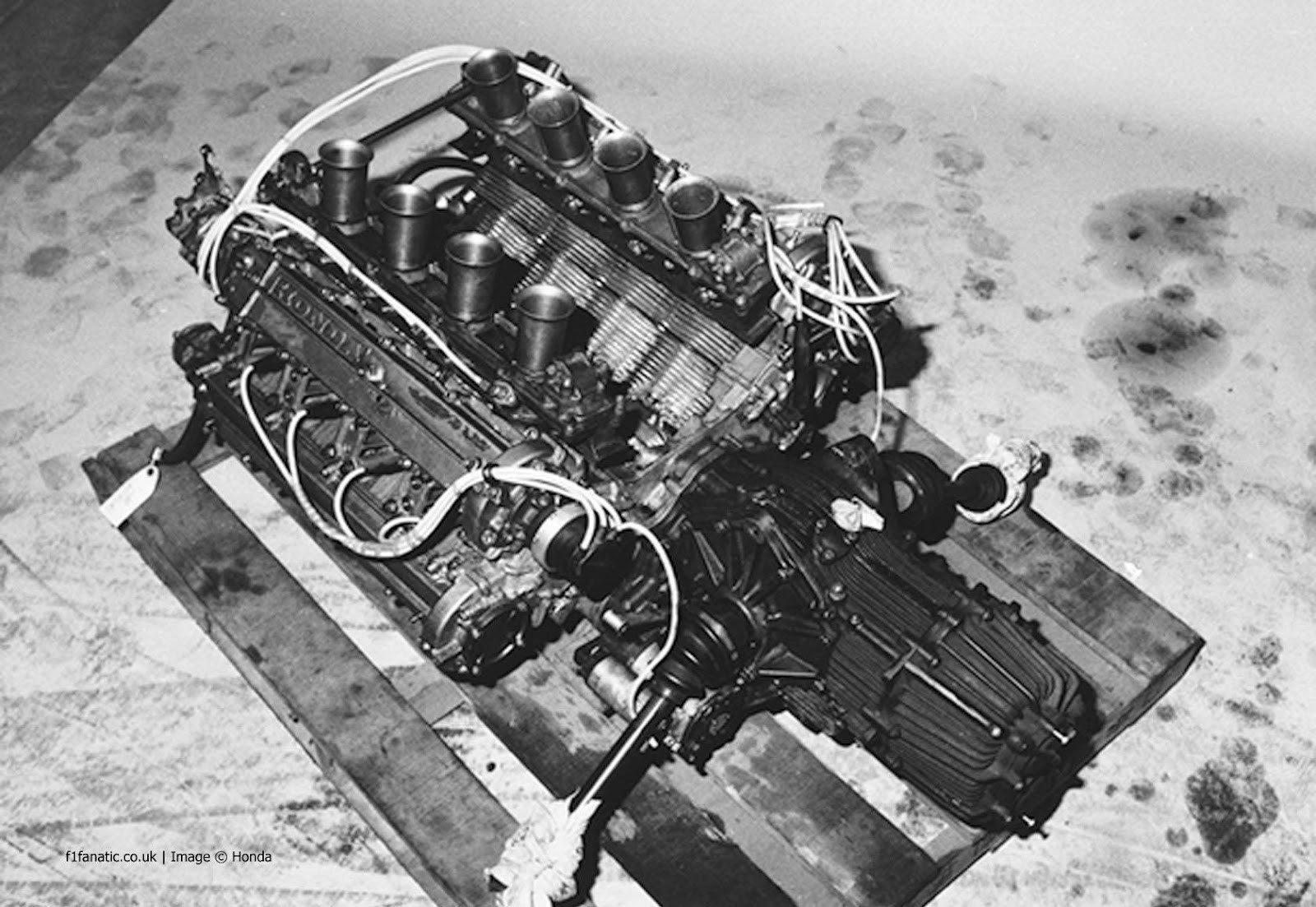

Honda F1 V10 engine, absolute beauty.

And not only in F1 but also in our everyday life, this multibillionaire company and its great founder have left an indelible mark.

1972 Honda CB350 Four motorcycle.

1973 Honda CB350 Four motorcycle.

How much genius, how much dedication, how much self-denial in building such fascinating objects.

Honda is the Land of Toys for those who love engines.

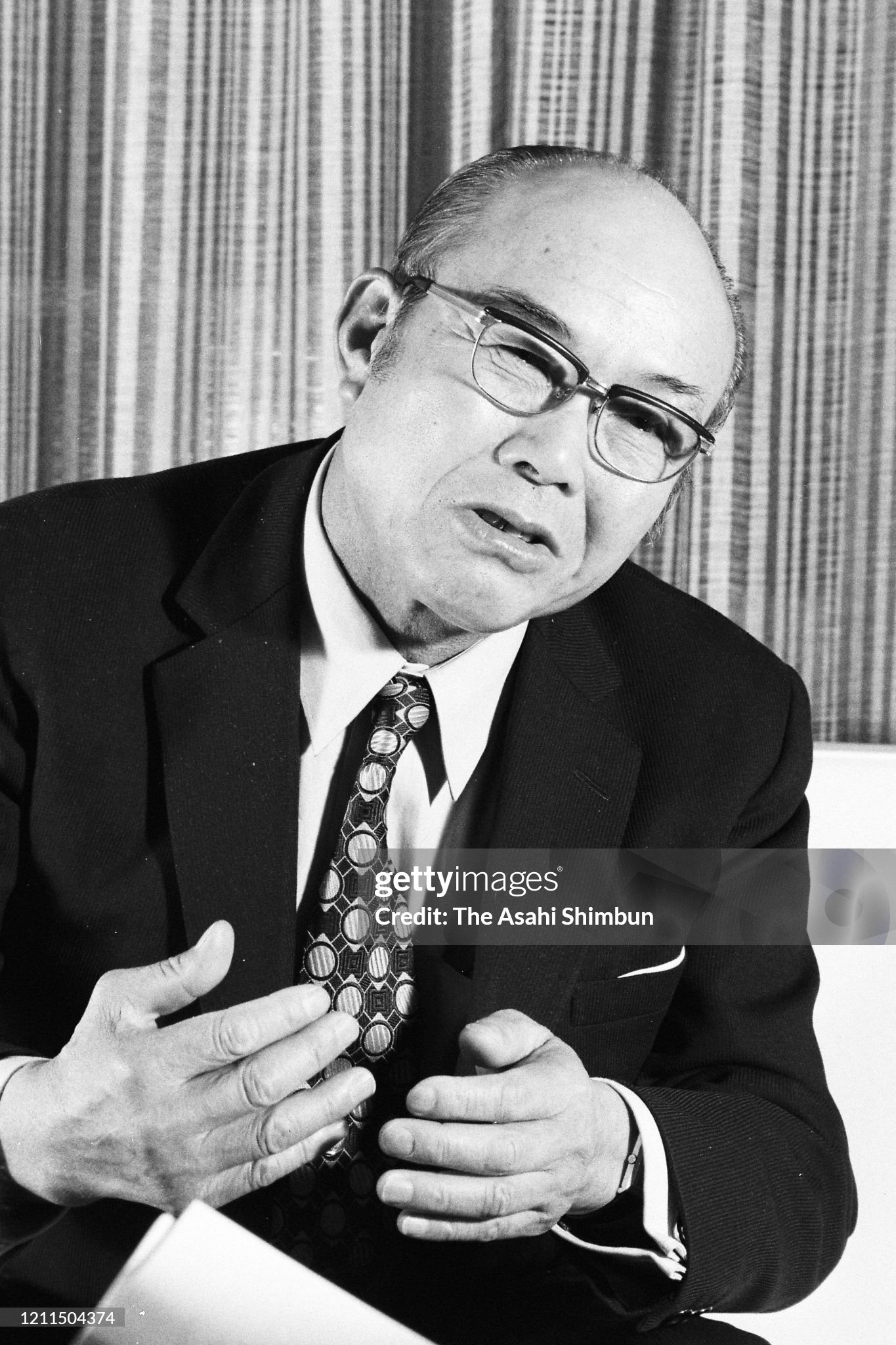

Honda Motor Co President Soichiro Honda speaks during the Asahi Shimbun interview on 07 February 1973 in Tokyo, Japan. Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images.

The story of Soichiro Honda, a famous industrialist and founder of Honda Motor Company Limited, is the story of a never-say-die fighter who was never enslaved by circumstances, nor the odds of life. Lack of money or education, physical injury or destruction caused by a natural disaster, lack of resources or lack of technical knowledge, the disappointment of rejection or competition stress – any inaccessibility is on the path of success. It could not be an obstacle.

Honda to leave Formula 1 at the end of 2021. 02 October 2020.

Red Bull and AlphaTauri are on the search for a new power unit supplier after the shock announcement that Honda will withdraw from Formula 1 at the end of 2021.

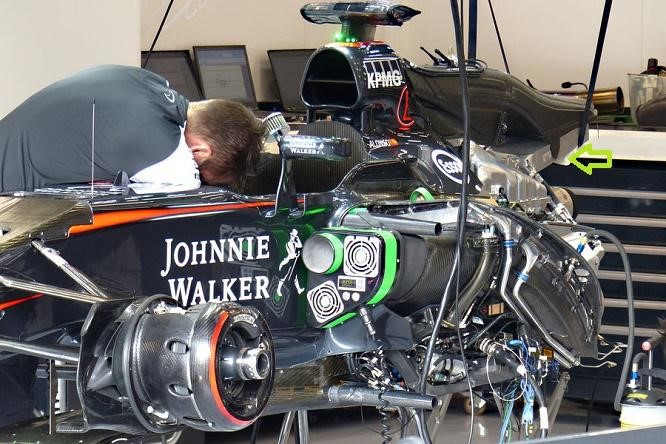

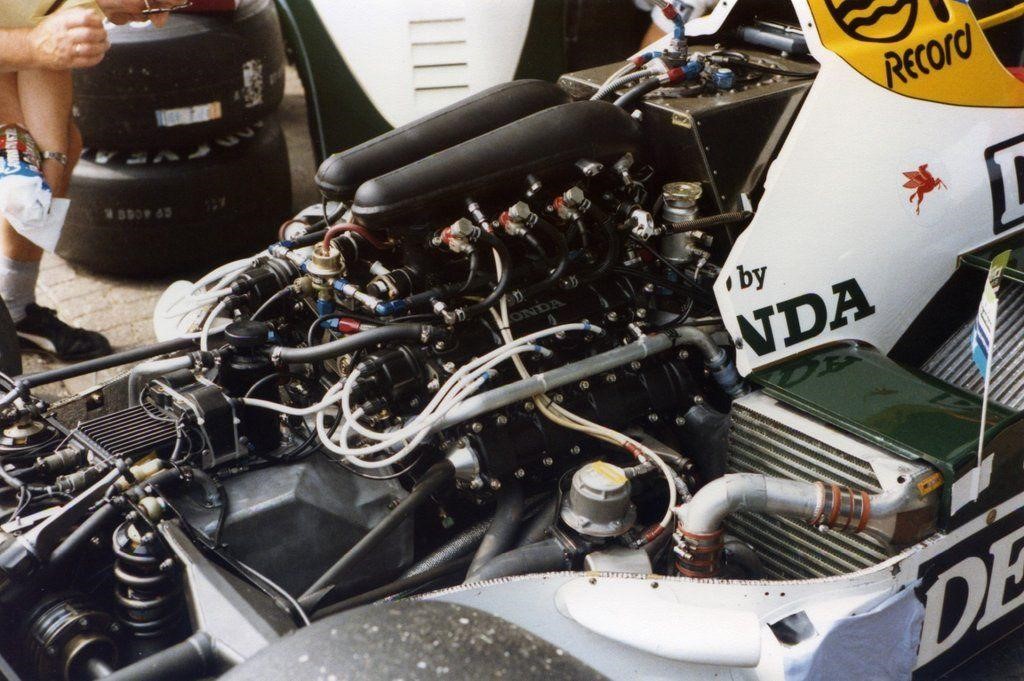

McLaren power unit Honda at 2015 Belgian GP.

The Japanese engine manufacturer returned to the championship in 2015 with McLaren, having been inspired by the new breed of power units that focused on hybrid and energy recovery technology.

Honda F1 2018 engine RA618H.

They suffered a difficult and unsuccessful partnership, culminating in them splitting up and Honda joining forces with Toro Rosso for 2018, before taking on Red Bull as a works team the following year.

Across the two teams, they have clinched five race victories to date in their two-and-a-half-year partnership with the Red Bull family.

However, Honda have decided not to continue beyond their current arrangement with Red Bull and AlphaTauri, which exists until the end of next year.

Honda said the decision had been made because the automobile industry was going through a "once-in-one-hundred-years period of great transformation" and that they'll leave having been "able to attain its goal of earning victories".

"Honda will work together with Red Bull Racing and Scuderia AlphaTauri to continue competing with its utmost effort and strive for more victories all the way to the end of the 2021 season," the Japanese company added in a statement.

The decision will leave Formula 1 with three power unit suppliers – Mercedes, Ferrari and Renault. Under the current rules, Renault would be obliged to supply Red Bull and AlphaTauri with engines as they currently have the fewest customers, unless the teams can convince Mercedes or Ferrari to provide a supply.

Red Bull – on behalf of both their works team and AlphaTauri – have recently committed to the new Concorde Agreement, which binds them to the championship until the end of 2025.

"We look forward to embarking on a new era of innovation, development and success," said Red Bull boss Christian Horner, who said he understood and respected Honda's decision.

"As a group, we will now take the time afforded to us to further evaluate and find the most competitive power unit solution for 2022 and beyond.”

Honda's presence in Formula 1 has always been part of its research and development strategy and, after its retirement, the resources currently committed to racing will be deployed elsewhere. In addition, the engineers who worked on the F1 project can capitalize on the experience gained in the avant-garde motorsport.

The key distinction that doomed Honda’s F1 comeback. Oct 17 2020. By Scott Mitchell.

If Formula 1 is to find a replacement for Honda to boost its manufacturer contingent, it will not be a like-for-like change. At least not on current terms, which make being an engine supplier and nothing else an unrewarding endeavour.

Maybe it was the only way for Honda to rejoin the F1 grid, as a works team was not considered when it struck a deal to reunite with McLaren and build an engine to F1’s new V6 turbo-hybrid regulations. But it probably meant Honda’s comeback was destined to be a short-lived affair.

Success as an engine supplier gives Honda little in tangible benefits. If it was immensely valuable the board would not have got cold feet. Had Honda gone the whole hog and entered a works team alongside its new engine programme (briefly setting aside the question of whether that was ever possible!) there’s a good argument to be made that it wouldn’t be withdrawing from F1 now.

The challenges faced by automotive manufacturers are unignorable and, as we’ve explored before, Honda’s claim that a shift in company priorities is behind its F1 withdrawal is not untrue, it’s just not the whole story. But there are also many reasons to be involved, otherwise Mercedes, Ferrari and Renault wouldn’t be.

The key distinction is that Mercedes, Ferrari and Renault all get big slices of F1’s revenue because they have teams entered as well, they sign up to the Concorde Agreements and they can maximise their branding on their cars. Yes, those manufacturers are having to put more in at certain points. But they get much more in return. And they can begin to offset their financial input through prize money and sponsorship.

The prime example is Daimler’s net contribution to the Mercedes F1 team dropping below €30million. Meanwhile, Honda is spending hundreds of millions building an engine in return for some small stickers, no prize money and a regulated sale price of €15m per season.

“We saw more marketing value, a better return on investment by owning a team,” says Mercedes F1 boss Toto Wolff when asked by The Race about whether being an engine supplier only has purpose now. “And so we’ve seen those both sides”.

“How the business case went for power unit manufacturers is certainly not how it should continue in the future. When I joined Formula 1 with Williams in 2009 I remember the power units cost $20 million and more. And today we have an obligation to supply at the price that is much below that.

“The hybrids, it was an engineering exercise, what kind of fantastic hybrid engine can be actually developed. We started to message around it in 2014 with the chief Bernie [Ecclestone] that this is really all not good for Formula 1 and the noise is not enough. And somehow you can’t sell your product by talking negative about it.

“We’re still lacking the messaging that these engines are fantastic hybrid technology. But they are much too expensive. So we need to introduce a spending cap for power units, that’s clear, like we’ve done on the chassis side, in order to make it more sustainable and in order to attract other OEMs in the future.”

It’s therefore easy to pity Honda, given it committed to F1’s new engine rules – the only new manufacturer to do so – then was immediately stung as it entered a formula being publicly condemned by its own and was hamstrung by F1’s awfully flawed financial model. Perhaps the main takeaway from its exit is that F1 enshrines ‘value for engine suppliers’ as a core part of the next-generation engine rules for 2026.

But, returning to Honda’s specific plight, if it wanted to it could have had a works team as well. Mercedes committed to it. And having a team alongside an engine programme is “no question” for Ferrari. “Certainly we believe it’s an important value,” says team boss Mattia Binotto.

The best example is Renault, which shortly after Honda joined the grid decided to up its participation from engine supplier only to fully-fledged works team, taking over the struggling Lotus outfit (that Renault had previously owned and sold).

“It’s exactly the situation that we experienced in 2015, when we asked whether to get out completely or to get back in completely as a works team,” says Abiteboul in response to The Race’s question.

“Because for us at that time, that’s not get any better. There is simply no business case to support the position of engine supplier only, given the cost of the technology and the very poor marketing reward that you can get out of that whether you do a good job, or a bad job.”

That’s a damning indictment of F1’s engine ecosystem.

Yasuhisa Arai, Honda's chief motorsport officer and McLaren CEO Ron Dennis, with vintage McLaren-Honda F1 cars. Handout Getty Images.

OK, Honda’s faith in the McLaren partnership was absolute, so perhaps the dream of a late-80s/early-90s repeat seemed so achievable that powering one team and sweeping all before them was worth its weight in marketing gold, in addition to the technological benefits of participating in such an intense engineering exercise.

But Honda managed to get into a position of winning races with Red Bull and is the only manufacturer in this engine era to taste victory with two teams. Yet its board is still pulling the plug.

Perhaps the consequence should be no surprise. Manufacturer participation in F1 can be boiled down to a numbers game very quickly. And as we’ve discussed, being isolated as an engine supplier makes Honda’s F1 programme a burden.

“I believe it’s always a ratio of risk versus return at the end of the day,” says Wolff. “Each of us needs to provide our return on investment that makes sense.

“So, whatever capital you deploy for the investment in Formula 1 needs to guarantee or needs to return sensible marketing value.

“And, if that is not the case, I can understand that somebody says ‘we’ve tried it and it didn’t function’.”

Which is how Honda’s board has clearly viewed the current project. That turns the commitment to F1 lukewarm and that is fatal to being successful in F1.

Honda has achieved a great deal in turning around its failing project to become a multiple race winner with Red Bull and may yet mount a title challenge against Mercedes next year. But it’s a long, long way from the achievements Mercedes has enjoyed in this engine era, or the longevity of Ferrari or even Renault. Because Honda doesn’t stick around long enough.

In the space of 13 years (2008-2021) Honda will have withdrawn from F1 twice and won five races. In the same time, Mercedes’ works team has been revived (taking over the Brawn team that was one Honda’s works outfit) and won seven consecutive title doubles.

Patience and investment pay off. The 2009 Brawn success could have been Honda’s. It didn’t have the commitment. Red Bull’s 2022-onwards success, should it take over Honda’s engine programme as its own, could be Honda’s. But it doesn’t have the commitment.

“The sport is not only about investment,” points out Wolff. “All the investment doesn’t buy you success because it’s a long term commitment that you need to provide”.

Who could take on Honda engine development for Red Bull?

“We’ve seen it with Mercedes, we had a couple of really painful years [2010-2012] and managed to turn it around. In the past, OEMs came and left. Many of them including Honda, BMW, Toyota and many more. And that’s unfortunate.

“F1 needs a stable grid, it needs a stable commitment from all of us. It needs to have the buy in from the board saying ‘OK, we will launch ourselves into this, it might be difficult, we’re setting our expectations low but at a certain time, we will turn this around’.”

Honda deserves credit for not leaving F1 with its tail between its legs in 2017 when the McLaren programme fell apart so disastrously. It opted to stay and fight. And it has been rewarded for that by becoming a race winner again. But sticking around any longer so see how that far that turnaround could really go, bizarrely, doesn’t appeal.

This era of F1 engine regulations has a few major flaws and chief among them is that building one makes no commercial sense. It is something that F1 will need to address to make those outside the bubble buy into the value that those within insist is there.

“We know that Formula 1 is anyway in a good period, it will grow,” says Binotto. “We’re very positive on what’s happening in the growth of F1, towards the business, towards sustainability.

“It’s certainly not great news [that Honda is leaving] but we need to keep positive. For F1, we’ve got a great future ahead and it’s down to us to even try to improve it and to attract new manufacturers.”

First F1 needs to decide what it wants. If three engine manufacturers aren’t enough then serious thought needs to go into making a standalone engine project worthwhile. Right now it isn’t. Honda has felt the consequences of that.

While it seems easy to say so now, Honda’s fourth F1 entry going the same way as its previous three iterations can be no great surprise given its position as an outlier against its fellow engine manufacturers. The other three have factory teams for a reason, even if it took Renault a little longer to recognise the need.

Maybe a works Honda team would have been as big a failure as the McLaren partnership and not had the potential of the Red Bull tie-up that has followed. Maybe a works Honda team would have never made it to the grid in the first place because it would have required a bigger initial financial investment that the board would never have bought into.

It’s impossible to say and far too easy to get bogged down in hypotheticals. What’s certain is Honda’s commitment did not match that of its fellow manufacturers. Its chance of establishing a worthwhile return on its investment had a clear risk attached. Especially as F1 created an ecosystem in which simply being an engine builder is arguably worse value than ever before.

It’s too late for Honda and its doomed comeback, but it’s a vital lesson to be learned for the next big decision F1 makes about its engine future.

Formula 1's managing director motorsports Ross Brawn has declared optimism that new power unit regulations will entice Honda back to the sport in the future. October 14, 2020.

The Japanese manufacturer made clear that its announcement to exit F1 is to pursue its own carbon neutrality goals by 2050, indicating that F1's plans for such a target by 2030 fall short in its estimation.

But with new PU rules due to be introduced in 2026, Brawn would like to believe they will prove attractive to Honda, particularly as they have been invited to work on shaping the proposals.

"It is unfortunate Honda are leaving Formula 1 at the end of 2021. It’s the fourth time in my racing career they stepped back and come back again," said Brawn in his F1.com column.

"I’m optimistic when their situation changes and when F1 evolves, we can engage them again as Honda have always been important and welcome members of the F1 community in the past and hopefully for the future."

Recognising the difficulties being faced by the likes of Honda in the current Covid climate, Brawn added: "all automotive companies are facing massive challenges at the moment.

"We as F1 need to respond to that and make sure F1 meets those challenges, stays relevant and becomes more relevant to provide automotive partners with viable challenges within F1 which can provide support with their objectives away from F1.

"I hope a new power unit formula, which will be introduced no later than 2026, will encourage them to come back again.

"We’ll also be encouraging them to be part of new FIA working groups, which will recommend what sort of power unit we will adopt in the future.

"They have been great partners in F1 and I look forward to working with them in future."

World of Honda. Honda Racing Stars.

The fire that burns the brightest is the will to win, but it’s the will to prepare – and to learn – that makes the difference.

Total commitment.

"If Honda does not race, there is no Honda." - Soichiro Honda.

Learning the lines.

Honda racing to the front.

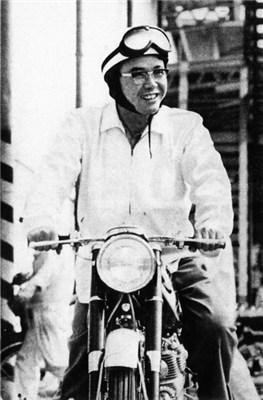

Soichiro Honda loved racing. In the 1930s he competed in events with his brother, driving a home-modified Ford.

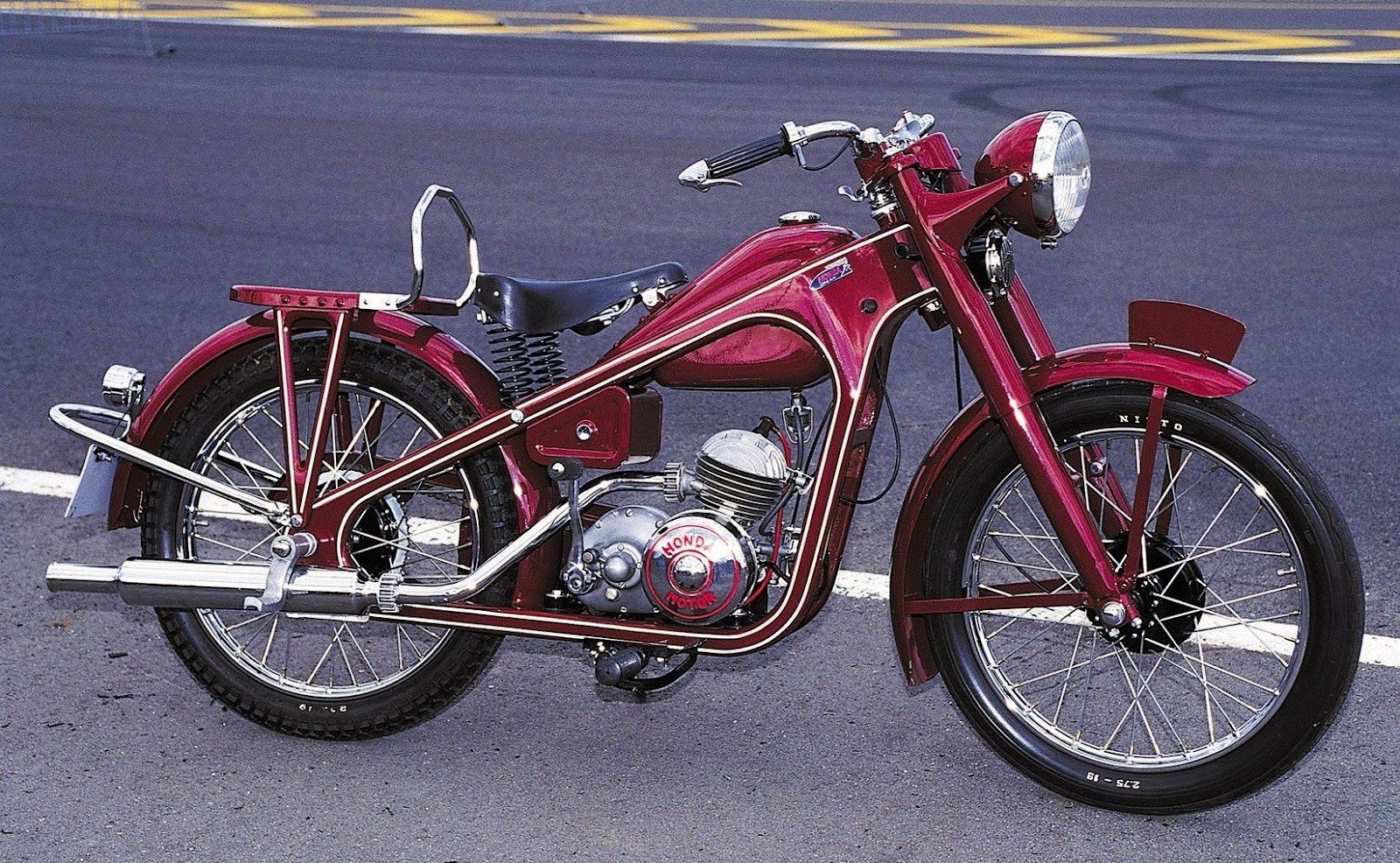

1949 Honda Type D Dream, 98cc, single cylinder, two stroke, 2 speed, air cooled engine.

Soon after establishing the Honda company, in 1949, he took us motorcycle racing where we quickly notched up a number of famous victories. Soichiro didn’t stop there: he had an ambition to become a champion in a car he’d make himself: engine and chassis. The first steps towards this dream were taken in 1964 – in no less a forum than motorsport’s top division, F1.

Honda becomes an F1 winner.

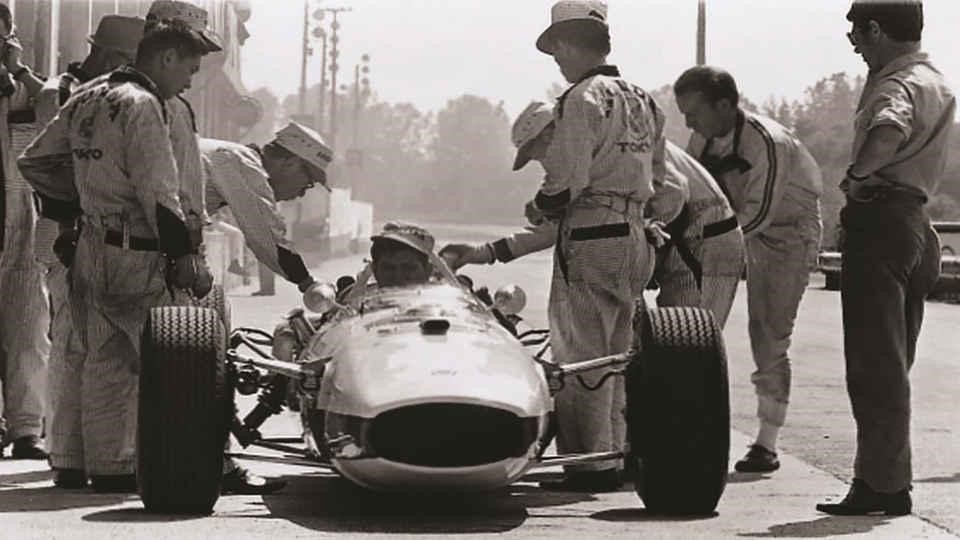

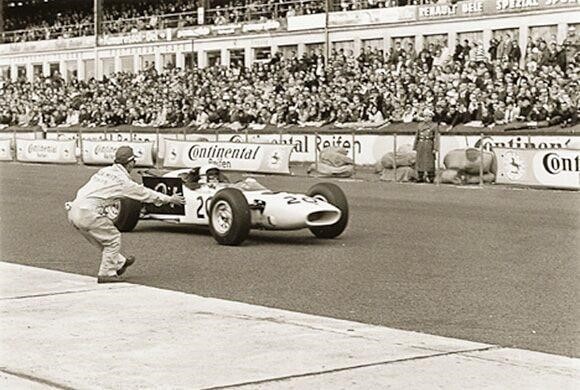

The Honda RA271 first appeared at the 1964 German Grand Prix, becoming more competitive with every race. The 1965 season seemed to be having more downs than ups until Richie Ginther, driving the RA272, claimed our maiden victory in Mexico. Barely a year after the team's debut, Soichiro had realised his dream.

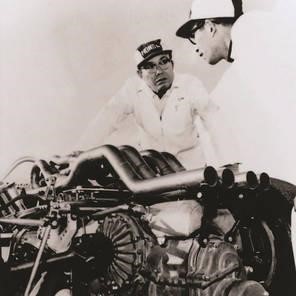

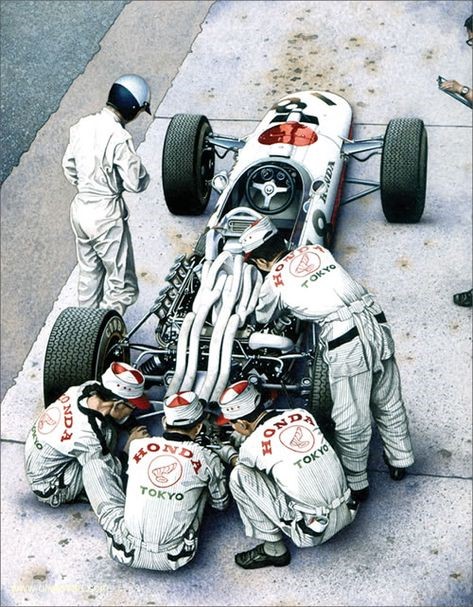

Hands on.

Soichiro would never sit back and watch, he wanted to see and feel his racing dreams happen.

Our Honda engineers worked hard to become top-level F1 winners during the 1960s.

A champion's drive.

World champion John Surtees drove for the team in 1967 and scored a memorable victory at the Italian Grand Prix - winning with the new RA300 in its first race.

1968 Honda RA302 engine.

The team withdrew from motor racing after the 1968 season, to concentrate their energies on developing new road cars, having cemented the Honda name in the motorsport hall of fame.

Finding the formula.

Our golden age.

After a 15 year absence we came back to F1 as an engine-supplier in 1983.

1984 Netherlands, Williams FW09B.

At the final race of that season, Keke Rosberg’s Williams Honda finished fifth and he won our first race of the turbo-era a year later.

1987 Honda RA167-E turbocharged V6 (William FW11B and Lotus 99T).

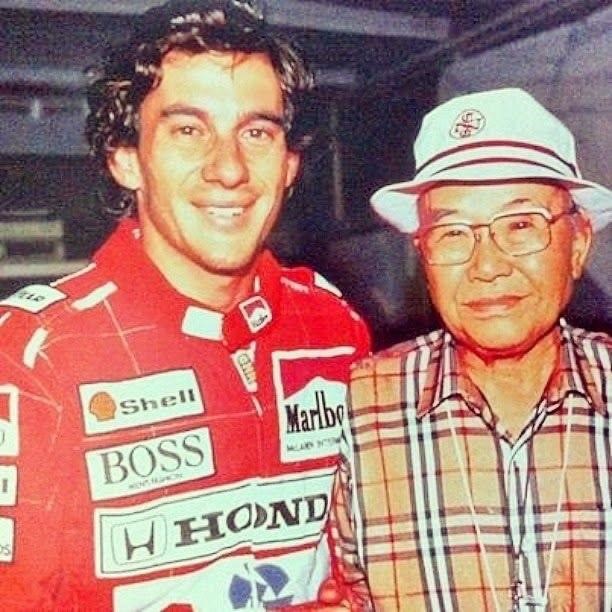

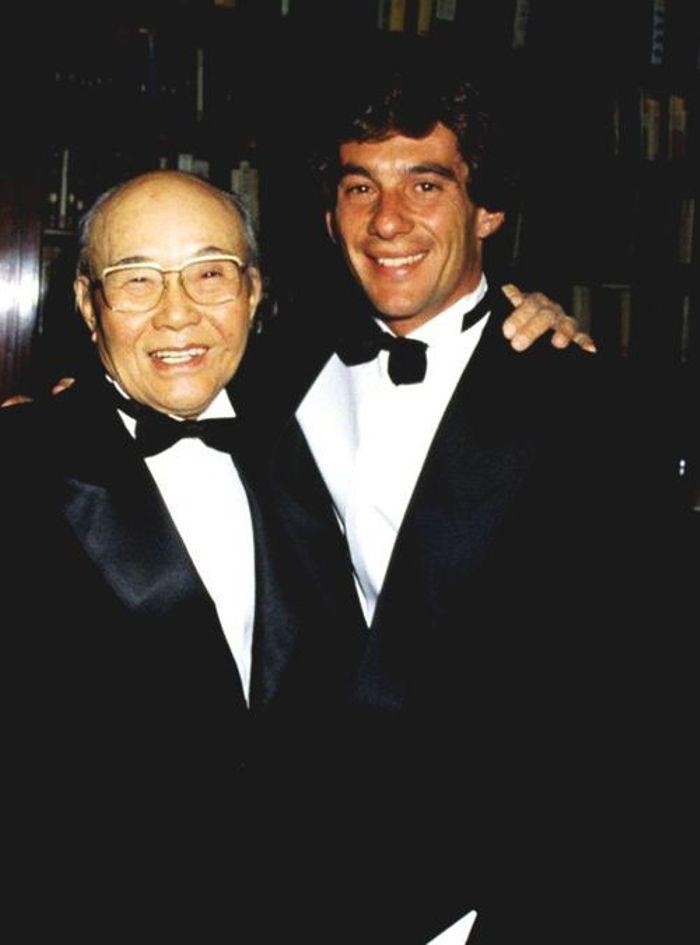

We won our first F1 World Championship title with Nelson Piquet in a Williams in 1987. At this time we were also supplying engines to Team Lotus with their up and coming driver Ayrton Senna – in that year’s British Grand Prix, Honda engined cars finished first, second, third and fourth!

Honda dominates F1.

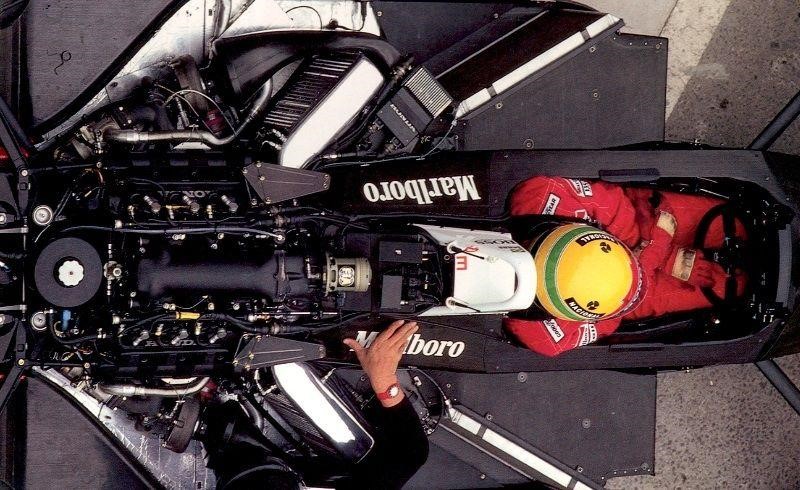

Ayrton Senna in a McLaren MP44 - Honda RA168E, 1.6 V6 twin turbo 2.5.

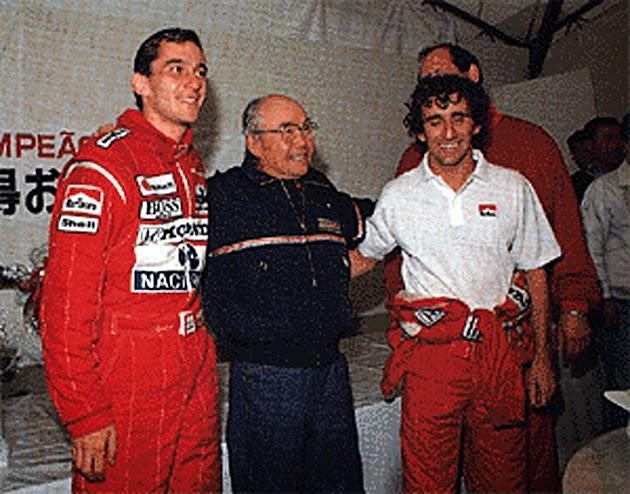

In 1988, we began our relationship with McLaren and won 15 out of 16 races, taking the title with Ayrton Senna. Alain Prost won the championship with McLaren Honda in 1989, then Ayrton took our engines to consecutive titles in 1990 and 1991. We were virtually unbeatable.

Reigning F1 World Champion Nelson Piquet drove the Honda-engined Lotus 100T during the 1988 season.

Honda racing green.

My Earth Dream.

Gerhard Berger's win for McLaren-Honda at the 1992 Australian GP, the final race of the year, brought our second F1 era to a close. We remained involved through subsequent seasons in a low-key capacity with our partner Mugen Motorsports.

Back to the top step.

As the new century came into view, we considered re-entry with our own car before choosing to supply engines to the BAR team from 2000 onwards. We were runners up in the 2004 season and in 2006 the team, now renamed Honda F1 Racing, won the Hungarian Grand Prix. It was at this race that Jenson Button claimed his first victory in Formula One.

2007 witnessed the start of our 'Earth Dreams' engine programme. Results were patchy but, under the inspired leadership of Ross Brawn, we made progress until the global economy crashed when, in order to concentrate on our core businesses, we pulled out of F1.

Button is F1 champion.

Ross Brawn and team principal Nick Fry bought out the Brackley-based team and, with some support from Honda, finished off the development of the new car in time for the start of the 2009 season. The now renamed Brawn GP team retained the services of Jenson Button and together they won, not only six of the first seven races, but also went on to clinch the driver's and constructor's title.

Back where we belong.

Because racing improves the breed.

Honda cannot stay away from racing for long. Relishing the potential to learn from the hi-tech hybrid F1 era, we rejoined the F1 grid in 2015, with the McLaren team providing the chassis.

A baptism of fire.

Soichiro Honda said that ‘success is 99 percent failure’ and we’ve experienced more than our fair share of challenges in recent years. This year we’re supplying and working with two ambitious race teams: Red Bull Scuderia AlphaTauri, with Pierre Gasly and Daniil Kvyat driving the AT01 and Aston Martin Red Bull racing, with Alex Albon and Max Verstappen driving the RB16.

After testing these distinctive, eye-catching cars in Barcelona, our enthusiastic teams look forward to moving up the grid and making strong progress during 2020.

Honda Racing F1.

"There has been a colossal effort from both sides over the winter and progress has been made on all fronts”. Christian Horner, Team Principal Aston Martin Red Bull Racing.

“Our priority for this season is to close the gap to the front runners, with the target of helping both our teams to achieve better results”. Katsuhide Moriyama, Chief Officer for Brand and Communication Operations, Honda Motor Co., Ltd.

The finish line is never the end.

From racetrack to road.

They say racing improves the breed. It certainly improves Honda. Everything we’ve learned from motor racing has always gone into our road cars. The circuit is our automotive test lab.

Pushing the boundaries in racing takes us to the cars of tomorrow. Win or lose, we never give up. The finish line is simply the start of another race, powering us towards our dreams.

Honda, a story that began in the 60s. By Emilio Deleidi. Published on 17/02/2020. Honda has a long history in Formula 1, which we want to retrace here.

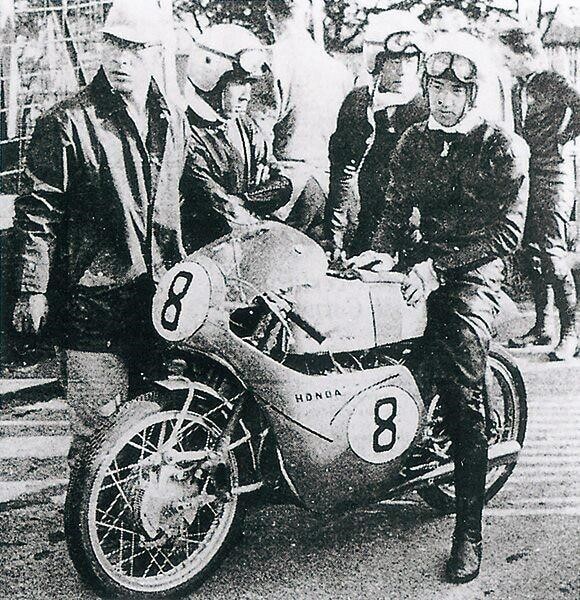

The first Honda race at the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy, ended with victory in the constructors' team standings in the 125 class.

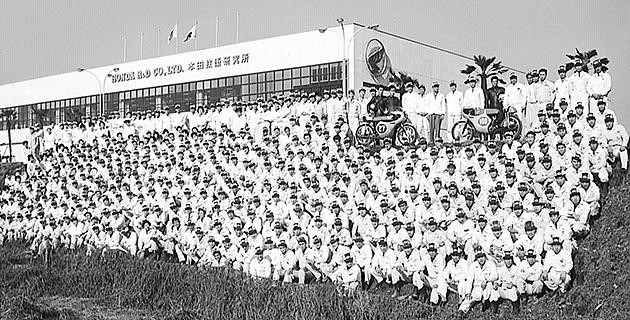

Once upon a time. To understand how a world-class industrial group such as Honda has come to be, with a leading role in motorsport (let's not forget the dominance in the motorcycle field either), we need to take a few steps back. And come back to 1948, to be precise 24 September, the day on which Soichiro Honda (born in 1906 and already since 1928 dedicated to the production of pistons and piston rings, thanks to his great passion for mechanics) founds in Hamamatsu, a town about 200 kilometers from Tokyo, Honda Motor Co, with a capital of one million yen. A year later, Takeo Fujjisawa, who will forever become a trusted collaborator of Mr. Honda, joins the company. The aim of both is to bring the Japanese manufacturer to the elite of world motorcycle production. Something that occurs punctually ten years later, with the start of sales of the Super Cub 100, a motorcycle destined to remain in production for decades, recording sales of tens of millions of units. But the passion for racing has been present in the DNA of the brand and its founder right from the start: and it is no coincidence that, as early as 1958, a Honda took part in a motorsport competition for the first time. It is the Tourist Trophy, which is still run today on a road circuit on the British Isle of Man: destiny is sealed.

The 1962 Honda S500 spider.

Four wheels. Honda's adventure in the world of cars began in 1962 and already has a sporty flavor: in fact, at the ninth edition of the Tokyo Motor Show, the Japanese manufacturer is present with three models: the S360, the T360 and the S500. While the formers will never go on sale, the S500 is destined to reach the market: it is a pleasant spider, with a front 4-cylinder engine of 531 cm3 and a power of 44 HP; the transmission, clearly inspired by motorcycling, includes a chain for each of the two front wheels. Thus began an adventure that will continue, from model to model, up to the present day. But that's not all: a few months pass and Honda gives a new shock to the car world, announcing its intention to participate with its own car in the Formula 1 World Championship, instituted for the first time in 1950 and, until then, dominated above all by the sacred monsters of motoring, such as Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati and Mercedes. After all, Soichiro Honda's credo is clear: there can be no improvements for the brand's models if the company is not present in racing. Furthermore, we need a track where car and motorcycle drivers can take them to the limit in safe conditions and on which the company can carry out its own tests to perfect the products: the dream of its own circuit, capable of hosting even competitions of international level, became a reality in Suzuka in September 1962.

Soichiro Honda and the first Honda F1 prototype that recalls the Cooper-Climax.

Ronnie Bucknum's Honda RA271 at the debut race, the 1964 German GP.

The first GP. The official announcement of Honda’s participation in the F1 World Championship comes in January 1964: the team is entrusted to the leadership of Yoshio Nakamura. In reality, operations have been underway for some time, because the manufacturer initially explored the possibility of relying, for the chassis, on an expert European partner, Lotus: an agreement that was not reached, however and that pushed Honda to decide to proceed on its own. The order to build a single-seater for the highest category came, in May 1962, through the chain of command to Hideo Sugiura, quality manager of the Saitama plant, whose first statement on the matter was: "what is Formula 1?" The inspiration comes from a Cooper-Climax, acquired some time before and the project proceeds rapidly, with the recruitment of young engineers fresh from university. In February 1964, tests began on a prototype with a gold body, driven by the same Nakamura: it was the RA270, designed above all to develop the engine. The project then evolves into the RA271, which starts its first race on 2 August 1964, the day of the German Grand Prix. A bold choice, given that we are racing on the terrible Nürburgring circuit… And the first steps are not easy. At the wheel of the single-seater, which is fitted with a 1.5-liter 12-cylinder V with approximately 210 HP of power, is a little-known Californian driver, Ronnie Bucknam, chosen to gain experience while maintaining a low profile. The debut was unfortunate: in qualifying the car was unable to complete even one lap without problems and in the race Bucknam went off the track after just two laps, while he was in ninth position, due to a steering failure. The race was won by John Surtees, who will play - as we will see - a leading role in Honda history. Over the course of the season, however, the RA271 will be deployed in all three Grands Prix, without being able to finish any of them: but that of Formula 1 is a difficult job...

Rochie Ginther gives Honda its first F1 victory with the RA272 at the 1965 Mexican GP.

The day of glory. To emerge in such a competitive world you need experience and a leading driver. To secure the first, Honda decided to develop a Formula 2 single-seater in 1965, initially with poor results; for the second, the choice falls on another American, Richie Ginther, also a native of California where, before devoting himself to racing, he studied engineering. In his past there is also Ferrari, for which he obtained an excellent second place in the Monaco GP in '61, behind Stirling Moss in the Lotus-Climax. Honda entrusted him with the task of honing the qualities of the new single-seater, called RA272, lightened in the chassis with the use of an aluminum alloy. Brought to its debut in the second race of the season, the Monaco GP, the car did not initially give Honda much satisfaction, finishing only two races, one of which (the Belgian GP) in sixth place. Problems with lubrication and engine overheating often stop the car, but the day that will give Soichiro Honda the greatest joy is actually not far off. The last race of the championship was held on 24 October 1965 and dominated by Jim Clark in a Lotus-Climax. The Mexican GP is special because it takes place at an altitude of over 2,000 meters which undermines the power of the engines. But the Honda V6 does not seem to suffer and Ginther, who in qualifying was unable to grab the front row (prerogative of Clark and Gurney, on the Brabham-Climax), still managed to take the lead from third position on the starting grid and not to lose it until the end, controlling the attacks of Gurney who ends the race with a 2.8-second gap. Honda thus savors its first victory in Formula 1, entering the restricted Olympus of total builders (of chassis and engine) capable of establishing themselves in the top category of motorsport.

When Honda brought a 1.5-liter V-12 to Formula 1.

New rules.

Richie Ginther stands beside the 1966 F1 Honda in preparation for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza.

In 1966 Formula 1 changes its face, introducing a modification for the engines destined to last for a long time: the maximum displacement became 3 liters for the aspirated engines and 1.5 for the supercharged ones. Few manufacturers, apart from Ferrari, are ready for such an important change: the English teams rely, as usual, on external suppliers, Maserati for Cooper and the Australian Repco for Brabham (a choice that will prove to be a winning one). Honda, used as the firm of the Prancing Horse to do everything by itself, creates a new 3-liter V12 which, however, does not fall within the absolute priorities of the Japanese engineers, committed as they are to developing road cars and a Formula 2 that, in '66, gets results, scoring eleven consecutive victories.

The Honda F1 team at Monza in 1966. The driver should be Richie Ginther. Note the beautiful car design and the cutest stripy pit crew uniforms ever seen.

The F1 RA273, on the other hand, will only be ready in the second part of the season, with Ginther leading it to its debut at Monza. The engine is powerful (it delivers 400 HP), but the car is heavy (the chassis exceeds 700 kg) and the results are hard to come by. Ginther still manages to get a fourth place in Mexico, a track that is obviously his friend.

For 1967, Honda secured a very high level driver, that John Surtees who won the '64 world championship with Ferrari, a manufacturer with whom he broke off relations following a disagreement at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966.

1967. John Surtees in a Honda RA273.

The season starts again with the RA273, which allows Surtees to get a third place in the inaugural race, the South African GP, until the debut of a new single-seater: it is the RA300, whose chassis is the work of an English specialist, Eric Broadley, founder of Lola.

Surtees wins the 1967 Italian GP with the Honda RA300.

Much lighter, equipped with the same V12 with power increased to 420 hp, the car made its debut at the Italian Grand Prix in 1967, a race that will go down in history. The practices, for Surtees, do not go very well: he qualifies only in the fourth row, with a time almost 2 seconds slower than that of poleman Jim Clark, on the inevitable Lotus.

But luck is not on the side of the Scottish champion: on lap 13, in fact, Clark has to stop in the pits to change a tire, losing an entire lap. Once back on track, Jim sets record laps, recovering the gap and regaining the lead: but when the victory seems to be no longer able to escape him, his Lotus falls silent, running out of petrol. In the lead there are then Brabham, with his Brabham-Repco and Surtees, who come out paired from the Parabolica: the audience holds its breath, the Australian has a slight advantage but comes out of the curve too wide and Surtees manages to precede him on the finish line by just two tenths of a second. For Honda it is the second triumph in Formula 1, for Surtees a great satisfaction, caught right in the house of that Ferrari from which he left slamming the door. At that moment, an idea was also born that would bring excellent results to the Japanese manufacturer: that of concentrating on the construction of excellent engines, leaving the task of designing the car to others. The 1967 season will see Surtees also get a good fourth place in Mexico and Honda close fourth among the Constructors, on equal points with Ferrari.

Surtees with the Honda RA300 at the 1968 Monaco GP.

The choice. The results obtained in the last part of the '67 World Championship, in particular with the resounding victory in Monza, make Honda confident for the following season. Soichiro, however, asks his engineers to develop an air-cooled F.1 engine, to emphasize the success achieved with a road model that adopts this solution, the N360 (which became a best seller). Thus, the team decides to develop two different engines for 1968: the water-cooled one is mounted on the RA301, which competes in all the races getting some good placements. Surtees is in fact second behind Ickx's Ferrari in the French GP in July; he gets pole position in Monza, where he has to retire; he is fifth in Great Britain and climbs to the third step of the podium at Watkins Glen, in the USA. With another Honda, the Swiss Jo Bonnier is fifth in the Mexican GP. On the other hand, the fate of the RA302, equipped with an air-cooled engine and completed on the eve of the French GP, is tragic. Who’s driving it is the French driver Jo Schlesser, who qualifies in the last row and who, on the 3rd lap of the race, goes off the track losing his life. At the end of the season, Honda decides to abandon Formula 1 to focus on the development of production cars. However, it will only be a long pause for reflection: "racing is part of Honda's corporate culture", declared Kiyoshi Kawashima, president of the company, at the press conference at the beginning of the year in 1978, adding that "it doesn't matter if you win or lose, because we want to show our best technology to Honda car customers in the form of a show”. For this reason, he will conclude, “our company has decided to return to competitions”. A new chapter in the history of racing will be written from that moment on.

The "Joy of Manufacturing" / 1936.

Soichiro Honda was born on November 17, 1906, in Komyo Village (now Tenryu City), Iwata County, Shizuoka Prefecture, as the eldest son of Gihei Honda and his wife Mika. Gihei was a skilled and honest blacksmith and Mika an accomplished weaver. The family was poor but Soichiro’s upbringing was happy, even though his parents were insistent about the need for basic discipline. It was thanks to the thorough education he received from his father that Mr. Honda, despite his freewheeling, irrepressible personality, hated nothing more than inconveniencing others and was always punctual about keeping appointments.

He also inherited from his father his inborn manual dexterity and his curiosity about machines.

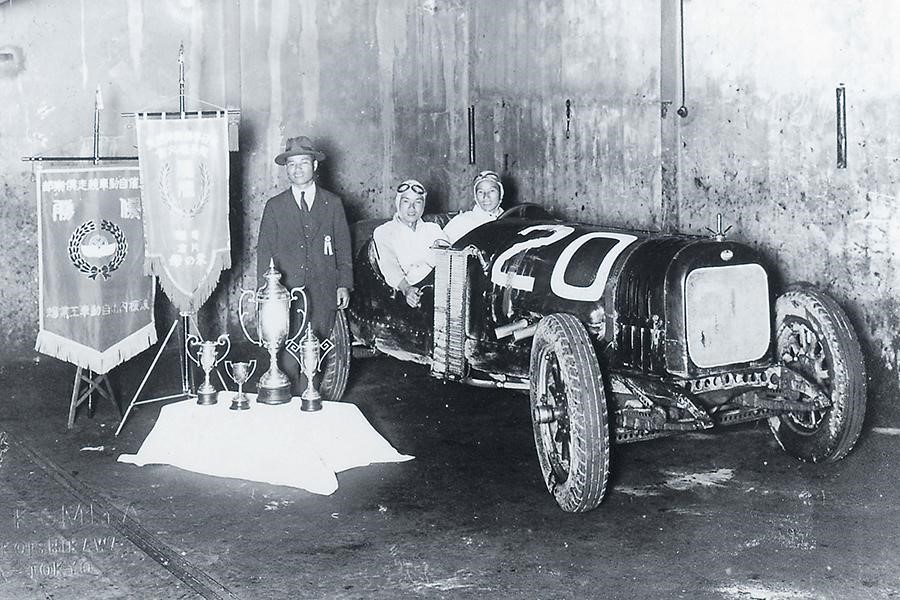

After winning the Fifth Japan Motor Car Championship in November, 1924 with the Curtiss-powered car. On the left is Yuzo Sakakibara (the proprietor of Art Shokai), to the right is the driver, Shinichi Sakakibara and in the middle is the riding mechanic, young Soichiro Honda.

When Honda was an apprentice at Art Shokai, he assisted the company’s owners, the Sakakibara brothers, in building a Curtiss racer. He accompanied them as their riding mechanic at races and they won the fifth Japan Motor Car Championship on November 23, 1924.

After a while Gihei opened a bicycle shop. Bicycles were at last starting to become really popular in Japan and when people asked Gihei to repair their machines, he sensed a business opportunity. As well as working as a blacksmith he put his natural skills and willingness to learn to good effect, repairing second-hand bicycles and re-selling them at competitive prices. From this moment his business began to be seen as the best bicycle store in the neighborhood.

When he was about to leave higher elementary school, Soichiro Honda saw an advertisement for Tokyo Art Shokai, an automobile servicing company, in a magazine called Bicycle World (Ringyo no sekai). The ad itself was not for bicycles but for "Manufacture and Repair of Automobiles, Motorcycles and Gasoline Engines". Even as a toddler Honda had been thrilled by the first car that was ever seen in his village and often used to say in later life that he could never forget the smell of oil it gave off. So it is easy to imagine that, when young Honda saw the ad, he immediately decided that he had to work at Art Shokai.

Judged by the number of ads it placed in automobile and bicycle magazines, Art Shokai must have been one of Tokyo’s top automobile repair workshops and there were probably any number of young men eager to become apprentices there. Even though the ad Soichiro Honda saw was in fact not a recruitment ad, he plucked up the courage to submit a letter asking to become an apprentice. There is no way of knowing exactly what he wrote, but in any event it was very fortunate that he received a positive reply.

Soichiro Honda left elementary school in April 1922 at the age of fifteen and joined Art Shokai as an apprentice in the Yushima area of Hongo, Tokyo. Employment in those days was a world apart from what we now expect. Juniors were given board, lodging and a little pocket money, but they received no real wages. Mr. Honda’s books and biographies include many stories about his time at the company but the important point is that his experiences there exercised an enormous influence on his later life.

Enthusiasm for hard work, a quick appreciation of the need to improvise, thinking for oneself, the ability to come up with a wealth of new ideas, a good feel for machines. The owner of Art Shokai, Yuzo Sakakibara, soon spotted the young man’s star qualities and began to take notice of him. Soichiro Honda, too, learned from his boss, not just how to do repairing work but how to deal with customers and the importance of taking pride in one’s technical ability. Sakakibara was the ideal teacher, both as engineer and as businessman. As well as understanding repair work he was also skilled in more complicated processes such as the manufacturing of pistons.

Whenever Honda was asked who he respected the most, he would always mention his old boss Yuzo Sakakibara. It is important to remember that Art Shokai’s repair work included motorcycles as well as automobiles. At that time ownership of automobiles and motorcycles was restricted to a limited social class and most automobiles were foreign-made. Compared to today, there were hosts of automobile manufacturing companies, large and small, all over the world and their output ranged from mass-produced models to high-quality vehicles with small production runs, sports cars and highly unusual collector’s items, all of which were imported to Japan.

All kinds of cars were brought to Art Shokai for repair, making it an ideal place for Honda to work and study, eager – even greedy – as he was in his pursuit of knowledge.

As Kawashima says, Mr. Honda worked so hard to extend and deepen his understanding of automobile engineering that he amazed everyone by the extent of his expertise. He was well versed in every sort of mechanism. "When he was an apprentice at Art Shokai and when he was manager of the branch in Hamamatsu, the Old Man learned so much by doing real work with real machines," said Kawashima. "He didn’t just have theoretical knowledge – he was an expert at all sorts of practical tasks like welding and forging. Those of us who had only studied the subject on paper from an academic standpoint just couldn’t compete."

Sakakibara also encouraged Honda’s interest in the world of motor sports. Motor sports in Japan goes back to the early years of the Taisho Era (1912–1926), around the beginning of World War I. It began with motorcycle racing but soon developed into full-scale car racing, which became popular back in the 1920s.

That was not all, because the automobile magazines carried amazingly detailed information about motor sports abroad. Japanese motor racing fans were aware, for example, that the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT) was the world’s greatest two-wheel event and that the greatest car races were the Grand Prix (GP) and the Le Mans 24-hour in Europe and the Indianapolis 500 in the United States. Of course, Honda knew this as well.

In 1928, the automobile magazine "Motor" contained an advertisement for Art Shokai that mentions the Hamamatsu branch managed by Honda. The automobile and motorcycle magazines of this period contained detailed articles about the Isle of Man TT Races.

In 1923, the company started to make racing cars under Sakakibara’s leadership with the help of his younger brother Shin’ichi, Honda and a few other students. The first model was the "Art Daimler," fitted with a second-hand Daimler engine. The second was the "Curtiss." This car is still preserved in the Honda Collection Hall in operable condition. This consisted of a second-hand engine from an American Curtiss "Jenny" A1 biplane fitted to the chassis of a Mitchell, an American car. Mr. Honda was particularly keen to help with the development of this special machine, encouraging Sakakibara with his skill in fabricating spare parts. On November 23, 1924, the "Curtiss" took part in its first race at the Fifth Japan Automobile Competition and won a stunning victory with Shin’ichi Sakakibara as driver and Soichiro Honda as accompanying engineer. After that experience the seventeen-year-old Honda would never lose his enthusiasm for motorsports.

At the age of twenty, Mr. Honda was called up for military service, medically examined and found to be color blind. Thanks to this diagnosis he managed to avoid spending any time in the military.

In April 1928, he completed his apprenticeship and opened a branch of Art Shokai in Hamamatsu, the only one of Sakakibara’s trainees who was granted this degree of independence. Mr. Honda was 21 years old and from this moment he devoted himself to making the most of his youth and skill. He was not just admired for his ability to repair machines, but gave free rein to his talent as an inventor, later earning the title "the Edison of Hamamatsu" and starting to do all kinds of work that went far beyond the narrow bounds of a repair workshop.

A photograph dating from about 1935 shows the Hamamatsu works and Art Shokai Hamamatsu Branch Fire Engine, fitted with a heavy-duty water pump. The company also made dump trucks, and converted buses so that they could carry larger numbers of passengers. At the right of the photograph there is a lift-type automobile repair stand, another of Honda’s inventions. Mr. Honda had said that "a human being should not have to do his work crawling around underneath a car" and made the stand himself. The low vehicle at the left of the photo is the "Hamamatsu" racing car and the figure to its right, wearing sun glasses and with a small mustache, is Mr. Honda.

The Hamamatsu branch of Art Shokai around 1935. The car on the left is "The Hamamatsu" and standing beside it with sunglasses is Mr. Honda. Fifteenth from the left is his younger brother, Benjiro Honda. Visible on the far right is a lifting-type automobile repair stand, which was rare then. This was another of Honda’s inventions.

By this time the staff of the Hamamatsu Branch, only one person when it was founded, had grown to more than thirty.

Soichiro Honda and wife Sachi, Tokyo, Japan in 1967.

Honda’s wife Sachi, whom he had just married in October of that year, joined in running the business, making meals for the live-in staff as well as helping with the accounts.

On June 7, 1936, Soichiro Honda had an accident at the wheel of the "Hamamatsu" in the opening race at the Tamagawa Speedway, Japan’s first racetrack, when he could not avoid hitting another car that was making its way back onto the track after a pit stop. Mr. Honda’s car did a roll and he was thrown clear: he was not seriously hurt but his younger brother and mechanic Benjiro was badly injured, fracturing his spine. Undaunted, Mr. Honda took part in just one more race in October of the same year.

According to Mr. Honda, "when my wife cried and begged me to stop I had to give it up," but she said that the true story was slightly different: "did he stop because of something I said? I think it was a lecture from his father that made up his mind!"

Times were changing as Japan entered the dark, militaristic chapter of its history. War with China broke out in 1937. During the so-called "national emergency," pastimes like racing were out of the question and motor sports died out in Japan for a time.

In 1936, the same year the accident occurred, Mr. Honda became dissatisfied with repair work and began to plan a move into manufacturing. He took steps to turn the Hamamatsu branch into a separate company but his investors opposed his wish to start making piston rings. Since he was making good money through his repair work they could not see the need to embark on an unnecessary new venture. Mr. Honda did not give up but sought the help of an acquaintance by the name of Shichiro Kato and set up the Tokai Seiki Heavy Industry, or Tokai Seiki for short, with Kato as President. He threw himself into this new project and started the Art Piston Ring Research Center, working by day at the old Art Shokai and developing piston rings at night.

Following a series of technical failures he enrolled as a part-time student at Hamamatsu Industrial Institute (now the Faculty of Engineering at Shizuoka University) so as to improve his knowledge of metallurgy. Nearly two years went by during which he worked and studied so hard that his facial appearance completely altered. At last his manufacturing trials were successful and, in 1939, he handed over Art Shokai Hamamatsu branch to his trainees and joined Tokai Seiki as president.

Production of piston rings started as Mr. Honda had intended but he was still beset with difficulties. This time his problems had to do with manufacturing technology. Mr. Honda had a contract with Toyota Motor Co., Ltd., but out of fifty piston rings he submitted for quality control only three met the required standards. After nearly two more years of visiting universities and steelmaking companies all over Japan in order to study manufacturing techniques, he was at last in a position to supply mass-produced parts to companies such as Toyota and Nakajima Aircraft. At the height of the company’s success it employed more than 2,000 people.

However, on December 7, 1941, Japan rushed headlong into the Pacific War. Tokai Seiki was placed under the control of the Ministry of Munitions. In 1942, Toyota took over 40% of the company’s equity and Honda was "downgraded" from president to senior managing director. The male employees gradually disappeared as they were called up for military service and both adult women and female students began to work in the factory as members of the "volunteer corps." Mr. Honda would calibrate the machines himself and took pains to ensure that the manufacturing process was made as safe and simple as possible for these inexperienced female workers. It was at this time that he devised ways of automating the production of piston rings.

At the request of Kaichi Kawakami, President of Nippon Gakki (now Yamaha), he also invented an automatic milling machine for wooden aircraft propellers. Kawakami was very impressed with Mr. Honda’s ingenuity: Previously it had taken a week to make a single propeller by hand, but now it was possible to turn out two every thirty minutes.

Air raids on Japan became increasingly intensified and it was clear that the country was headed for defeat. As the air raids continued, Hamamatsu was smashed to rubble and Tokai Seiki’s Yamashita Plant also was destroyed. The company suffered a further disaster on January 13, 1945, when the Nankai earthquake struck the Mikawa district and the Iwata Plant collapsed.

This was followed by Japan’s defeat on August 15. The country had undergone tremendous change, and Mr. Honda’s life, like that of Japan itself, was about to be totally transformed.

Neighborhood Workshops and Super Factories always have "Dreams and Youthfulness" / 1959.

In January 1959, Honda dropped in by himself at the Yamato Plant and called out Takao Shirai, the head of the Production Engineering Division. Shirai had just resolved an early problem arising with the Super Cub at the end of the previous November and he had just finished setting up for expanded production at the end of the year.

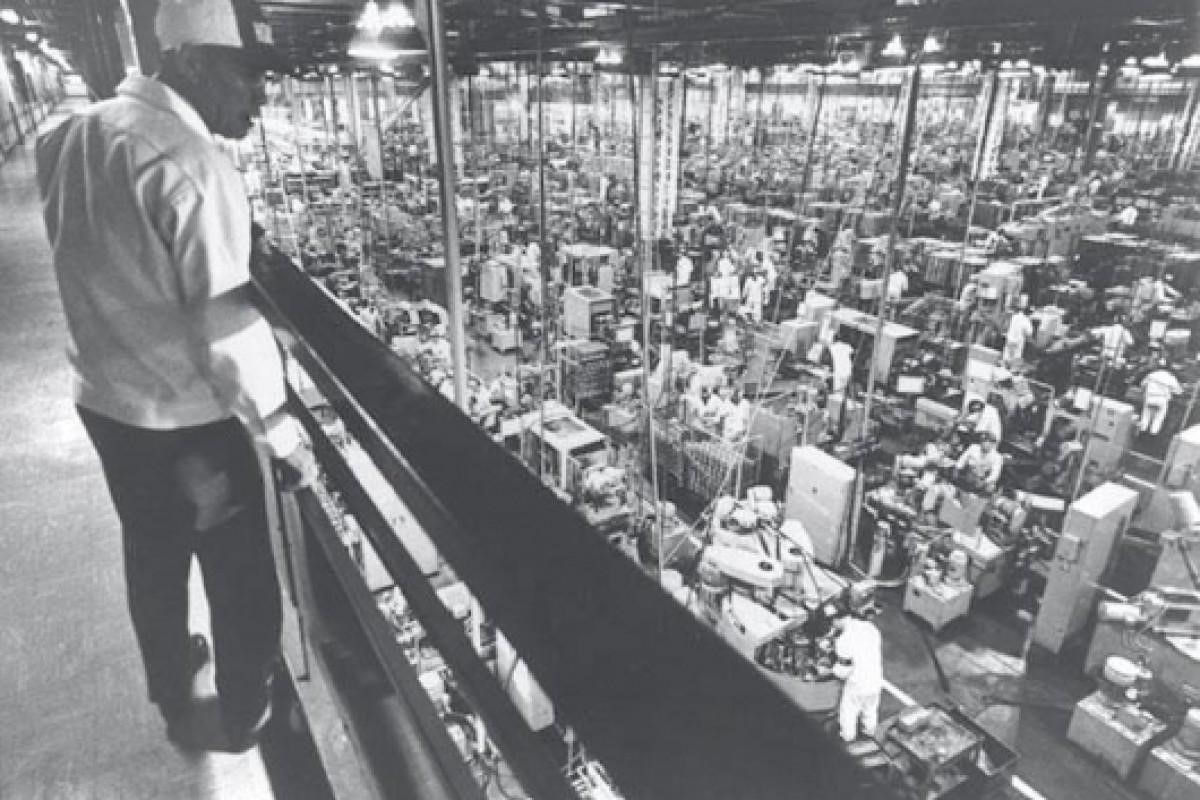

Thirteen years after that crude, barrack-like Yamashita Plant, Honda completed its Suzuka Factory with the mass-production capabilities they had dreamed of. This was the most advanced plant of the time, and visitors streamed in not only from the motor vehicle industry but from other industrial sectors as well, to observe it in operation.

He remembers the occasion:

"I could hardly forget it. It was in the evening of January 19. All of a sudden, I was told, 'you're going to Europe for a while.' I asked what for and was told, 'just go. You can figure out a purpose on your own. You also can decide how long you want to stay over there.' That was all he told me, without a word of explanation.

"The Super Cub was selling and selling. However, that was during the period that people called 'the pan-bottom economy' because of the deflationary recession going on. Foreign currency reserves were low, so it was difficult to get both a travel permit and a foreign currency allowance. Later in the same year, Mr. Kiyoshi Kawashima made our first entry in the TT Races and Mr. Kihachiro Kawashima established American Honda, so there was a lot going on. In any event, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry turned me away twice. They looked at my resume and flatly refused, saying, 'why should someone with a degree in economics who is neither a salesman nor an engineer get to use our country's precious foreign reserves to go overseas for no particular purpose?' The third time around, I told them, 'Honda is certain to be earning foreign currencies in the near future; we are now making motorcycles that can be exported to the world and if it doesn't work, I'll kill myself.' After this most unconventional approach, they finally gave permission, but only for travel. Mr. Kihachiro Kawashima sold plenty of Super Cubs in America, so I didn't have to commit suicide," he said, laughing.

Without a single dollar of foreign currency, but only a round-trip air ticket, Shirai set off to Europe. For his expenses in Europe, Honda had requested a trading company there that was importing machine tools to advance him funds. Shirai recalled:

"anyway, my work was production engineering, but I wanted to be able to answer any questions that might come up when I returned, so I went all over and listened to everyone and looked at everything, including plant facilities, of course and personnel management, pay systems, traffic conditions, parking practices, fashions, everything. I did this in Germany, Switzerland, Italy and England. Germany was the most advanced in manufacturing plants, so I went back there again. A while later, on June 20, a letter came to me from one of my colleagues at the Yamato Plant, Mr. Enomoto.

He wrote, "actually, there's a plan to build a new Super Cub plant. They've selected several prospective locations and are waiting for you to come back. 'The Honda Way’ has alleged that I had been told about the project before going to Europe, but in fact, I really hadn't been told anything about it."

After being away for three months, Shirai hurried back to Japan. This was because he knew very well that once a project had been decided on, Honda would move with lightning speed, no matter what, to set it in motion. Shirai remembers:

"just as I had thought, the president had been waiting for me to show up. 'Starting tomorrow, I'm going to go look at the prospective sites. You come with me.' The president drove his own car and the passengers were Managing Director Kensuke Takahashi, myself and Mr. Shiozaki. We set off to tour the locations."

The major candidate sites were two locations at Takasaki in Gumma Prefecture, Utsunomiya in Tochigi Prefecture, Inuyama in Gifu Prefecture and two locations at Suzuka in Mie Prefecture. Shiozaki recalls how he actually got left behind during one trip to a potential site:

"the Old Man's criteria for site selection included more than just building conditions and inducements. 'Before land and water and electricity, see, it's people. We'll choose the people who live in the location.' This is a direct expression of the Old Man's idea of the value of the human being. His idea was that no matter how good the other conditions might be, what came first was a place that had sincere, honest people. This includes the people in the local government. At one prospective site, a long line of cars belonging to prefectural assemblymen or something followed along right behind us. On finishing a presentation about the site, somebody from City Hall said that we would move on to hold the rest of the discussion at a restaurant where they had made reservations. The Old Man said, 'I'm leaving!' and jumped in his car and drove away," said Shiozaki, laughing.

"Mr. Shirai and I ended up taking the train back. The Old Man was still angry the next day and said, 'I didn't go there to get treated to a fancy meal!'

Their experience at Suzuka was in complete contrast, as Shiozaki recalls:

"at Suzuka, everything surprised me from my first impression forward. First of all, the City Hall was different. Government offices wherever you go have desks piled high with papers, or at least that was our preconception. However, at Suzuka City Hall, everything was neat and orderly without a thing out of place. When we went into the reception room, someone quickly brought us oshibori hand towels. They brought us those and chilled green tea. It was not hot tea. This was in July, at the height of the summer heat. Then there was the Mayor, Ryuzo Sugimoto, who was waiting for us wearing not a suit but work clothes and he had on gaiters."

The Honda party was quickly taken to see the site. Shiozaki further remembered:

"Mayor Sugimoto made a quick signal. At that moment, a line of flags rose up all at once in the distance. 'From there to there is the candidate property,' he said. We could see the whole thing at a glance. I said to myself, they're pretty good. I was impressed. That moment is still vivid in my memory even now."

Mayor Sugimoto also explained the inducement conditions himself. According to Shirai:

"it was beautifully done, that's all I can say. We were scheduled to visit another strong candidate site on the next day, so for my part, I didn't feel that I could say anything hinting at a decision. However, when we returned from the site to City Hall, we again were given oshibori towels and green tea, but not a single tea cake was to be seen. They must have just served what they had, without getting in anything special for us. This was the kind of mayor they had running the city government. I thought, if we come here, we'll be all right, no doubt about it. That much I felt sure of."

The prospective sites were studied thoroughly and quickly.

"I examined the two Suzuka locations, sites A and B," said Shirai. "I compared them with the other prospective sites and reached my own conclusions. Returning to Tokyo, I spoke to Mr. Honda, Mr. Fujisawa and the other board members in a meeting. I told them that I thought site B at Suzuka was the best. Site A was 400 m wide from north to south and 1500 m long from east to west. A long, narrow property like that is not suited to a manufacturing plant. Considering future expansion, I said, site B is the best. Mr. Honda said, 'I think so, too' and Mr. Fujisawa said, 'then let's settle on that site.' With that, the location of the present Suzuka Factory was decided."

However, the board meeting then proceeded to developments that Shirai had not expected:

"Mr. Fujisawa went, after that, to say: 'the new plant in Suzuka will be of a kind never seen before anywhere in the world and we're going to put young Shirai in charge of building it.' I thought, what? After all, I knew very well that this was a major project that might determine the company's fate. I had learned something in Europe and I had been expecting to participate in this project, but I had never once considered that I might be given that responsibility. Then Mr. Fujisawa went on: 'considering the magnitude of this job, I want all of our operations to agree unconditionally to any personnel requests that Shirai might make. ' Mr. Fujisawa asked every one of the board members for his reply. They had no choice. 'Good,' he said, 'everyone concurs, so you can set your mind at ease and go to work.'"

Shirai can still remember the tension he felt then as though it happened yesterday:

"then, Mr. Fujisawa looked at me and said in a very loud voice, 'however, there are two conditions. One is that you use as much money for this as you want. The other is that the money you use must be recouped within two years. There are no other conditions at all. Apart from these, you do as you like.' The president nodded in agreement and looked straight at me."

Shirai was 39 years old at that time. Naturally he was not a member of the board, but a plain section head. Here, again, the company was choosing a youthful contender.

In June, Honda underwent its eighth capital expansion. Its capitalization was now 1,440 million yen.

It is not known how early Honda and Fujisawa had been talking over this new plant construction project. It is certain that the project was already in motion when Honda ordered Shirai to go to Europe. The products made by Honda were on the verge of becoming acceptable around the world. What was needed next was a production plant capable of producing them in large quantities.

Honda's previous investment in imported machine tools had been a major gamble, but this new plant construction project was an even greater undertaking and the company's future was on the line.

"The board officially presented me with three basic requirements," Shirai recalled. "The first was 'that this be a mass production plant utilizing rational methods of a kind that have never been realized before.' The second was 'that no limit is set on the amount of money to be invested, but the investment must be recouped within two years.' The third requirement was 'that the plant be harmoniously integrated into the local community.' The second condition that Mr. Fujisawa laid out to me during the board meeting was the pure expression of his approach to plant operation grounded in his unique business experience. The first and third conditions for my taking on the plant were likewise the pure expressions of Mr. Honda's ideals and philosophy. So, you see, the various conditions clearly express the personalities of these two men. Mr. Fujisawa very firmly put a lid on any further discussion by the members of the board and so made it possible to set conditions that would allow me to do everything I would need to do. At first I felt stiff all over, but then I settled down with the strong sense of determination that I would repay their confidence in me."

Toward the end of July, a Suzuka Construction Project Office was established. The four members who first gathered at the office in the Saitama Factory were Takao Shirai, Sadao Shiozaki, Kotohito Takahashi and Tsuneko Oshima. They set up a liaison office in the Kanbe area of Suzuka City to serve as a local base.

They moved into action immediately. The first order of business was to apply for permission to convert agricultural land to industrial use. Shirai recollects:

"Japan during that period was still trying to expand agricultural production, so the kind of reduction in agricultural use of land we see today was unthinkable. The primary purpose for land was agriculture, so we knew that the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry would not easily approve our application. Ten years earlier, soon after I joined Honda, I had worked very long and earnestly on the report to go with the company's application to the Ministry of International Trade and Industry for a subsidy. Since then, however, I had grown rather shameless. This time, I decided to put on a flamboyant show of what we had. Nothing concrete had even been decided yet and we didn't know just what kind of plant it was going to be, but I went ahead and wrote the application as if we did. So I gave them a pretty big show, about 33,000 m2 in size," he added, laughing. "I made it so that the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry would understand that Honda was using the large parcel of land for this kind of purpose and accept that the application was valid. I took that over to the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and to the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, and the application was approved."

The next order of business was to get down to concrete work on the actual project itself. Shirai remembered:

"we were deadly serious about this. I would have to decide on the basic layout myself. For this, I had to think carefully about many different issues in combination, including how the plant should first start operating and what stages of expansion should be planned for at how many years in the future. With a view to future expansion, I would need to ask the city whether a junior high school located on the property slated for later acquisition could be rebuilt on a nearby hill at Honda's expense. I went to talk with Mayor Sugimoto, explaining our desire to expand the plant later and obtained his definite approval. We grew even more intensely busy."

Decisions were made to have the Kintetsu train line extended to Hirata-cho and to purchase property for water supply facilities.

Meanwhile, it was also necessary to make plans to satisfy Fujisawa's condition that "the investment will be recouped within two years." Shirai says:

"The period was two years, but we could never make that time limit if we waited until the plant was completed. What we could get started moving most quickly was an engine assembly line. Our idea was to set up a temporary plant at the parts receiving center and bring that on line in April 1960. Our production plan called for finished vehicles to start coming off the line in the main plant from August."

Shirai's team had to move quickly to realize the dream-like vision of "a mass production plant utilizing rational methods of a kind that have never been realized before." Shirai went on:

"we made this plan on the basis of a reverse concept starting with recouping of the investment. After all, this was our greatest concern. It seemed unlikely that we could manage to recoup the investment within two years by running just two shifts. If we were dealing with three shifts, then it would be better to build a windowless, totally air-conditioned plant so that weather conditions, differences between night and day and differences in temperature would not affect our employees. The notion of plant construction commonly accepted in Japan at that time, meaning a steel-frame structure with a slate roof, would not work for us. We needed a ferroconcrete steel-beam structure. Construction costs would be higher, but we were aiming for a plant that could function ten and twenty years into the future. So we went ahead. I reached the conclusion that we would not work from the usual Japanese sense of scale."

Then there was one more major issue, "that the plant be harmoniously integrated into the local community." Shirai further reminisces:

"A plant that is not bound to the local community is not a plant for the future. We thought about the people who would be coming to tour the plant and decided to build an observation corridor on the second floor. However, Mr. Honda's idea of harmonious integration with the community meant much more than that. Ever since the Shirako Plant was built, he had been very fastidious about not allowing Honda plants to disturb the surrounding community. As we would put it today, a plant should harmonize with the area and with the local environment. However, Mr. Honda's ideas on this were more than just a facade. He truly believed that we have to get along well with our neighbors. The question was, how to make this happen at the Suzuka Factory. This was another major assignment for us."

Shiozaki had himself experienced Honda's care and concern for the local community on various occasions. As he recalls:

"an eel restaurant proprietor who lived near the Shirako Plant came to us and complained that the engine durability tests made so much noise that he couldn't sleep. The engines were running 24 hours a day, so it was no wonder that someone complained. Then one day the Old Man heard about it and he said, 'I want you to be working, but I don't want it in such a way as to trouble our neighbors. Do something about it!' So we said, please stop the engines so we can do sound-proofing work and, 'idiot!' he said, 'if it was just a matter of turning off the engines, I wouldn't ask you! ' So then there was nothing else we could do. We built another large structure right on top of the building containing the engine testing laboratory, to cover it," said Shiozaki, laughing. "We stuffed fiberglass into the space between the two structures. While we were doing this, all we heard from him was, 'do it soon. Do it fast. Do it today.'"

The employees were also encouraged to submit ideas for the new plant. Many suggestions from the shop floor were incorporated into the designs.

Shirai gathered a carefully selected group of employees in the Suzuka Construction Project Office. At the core of the management section was Masami Suzuki. The cost that Fujisawa had specified for the Super Cub to be built at Suzuka was about 20% lower than the Saitama Factory's production cost. The total construction cost at Suzuka, including company housing, dormitories and so on, would require 4,500 million yen.

"I had Mr. Suzuki thoroughly calculate our cost projections," Shirai recalled. "The bottom line was that we would have to produce 60,000 units a month. Two years would still be nearly impossible, but I judged that we could recover the investment in two years and four months. This would extend four months past the deadline set by Mr. Fujisawa, but I concluded that expenses should not be reduced for that reason alone."

In September, construction work began at a rapid pace. On the 26th of that month, however, that area of Japan was assaulted by Typhoon Ise Bay, which was said to have been the most powerful in the history of meteorological measurement. Shirai remembers:

"the first report came in from Mr. Shiozaki. The gravel that was especially vital for foundation work had all been taken to repair flooding damage and they couldn't get any more. I replied that delay was unacceptable and construction could proceed if they could obtain 70% of the total amount required. Then Mr. Shiozaki managed by extremely hard work, which hardly allowed him any sleep at night, to obtain gravel from the Yasu River in Shiga Prefecture and from as far away as Kyoto. Despite the occurrence of a problem of this magnitude, the project schedule was not delayed. This was thanks to the people on the spot."

Shiozaki implemented thoroughly unconventional ideas in order to speed up the work. Shiozaki recollects:

"the construction company's architectural blueprints for the plant were delayed. If they were going to be one month late, we would either have to pour concrete now or face another month's delay. So they drew up just the blueprints of the foundation for us. We decided on a column interval of nine meters and proceeded rapidly with the work. About the time that the concrete had dried, the building blueprints were ready, so we were able to go ahead and start the construction work. This is the kind of idea you come up with when you follow the Old Man's way of thinking. You won't find it coming out of someone who thinks conventionally," he laughed.

A number of suggestions and ideas for the project had been collected from Honda's various workplaces. Shiozaki worked these into the foundation laying that had already begun and created a layout drawing for the 36,300 m2 plant. He then turned that into a three-dimensional rendering from an aerial perspective that would allow the entire layout to be grasped readily.

In January 1960, the building blueprints and layout were completed. They depicted a windowless, fully air-conditioned plant of an advanced kind never before seen in Japan's motor vehicle industry or any other industry. Shirai says:

"before we started on the layout, Mr. Fujisawa told us, 'I expect you to make this a plant exclusively for Super Cubs.' I replied that no, we were thinking of automobile production in the future. When he heard that, Mr. Fujisawa got very angry. He said, 'I've never considered having anything whatever to do with four-wheeled vehicles. Just confine your thinking to the Super Cub.' I could understand that, too. However, I had been working together with Mr. Honda continuously ever since the Hamamatsu days and the cherished hope of his life covered more than just motorcycles. I was sure that his dream extended to automobile manufacturing. I wanted to realize Mr. Honda's dream for him on this site and in this plant. No matter what Mr. Fujisawa said, this was one thing I intended to accomplish."

As it turned out, he did not deviate from his professed aim.

Nor did Fujisawa issue further orders for him to stop.

The Suzuka Factory was designed to be an optimal mass-production facility for the Super Cub. However, it was from the very first given the flexibility to make automobile production possible there, if the time came for that.

Honda looked at the layout and listened to the detailed explanations by Shirai and other members of his team. The die casting plant had been located with consideration for the people living in the area and so, had even included research on prevailing summer and winter winds. The company housing and dormitories were not placed all together, but were dispersed throughout the community. No cooperative store just for company employees would be built. Apart from a clinic in the plant, employees needing medical care would be directed to local hospitals. And, beyond these and other, similar measures, the plant did not have a wall surrounding it to separate it from the outside world. Instead of a wall, trees and greenery would be planted.

This plant held resolutely to the concern for harmonious integration with the community that Honda had wanted to see.

The Suzuka Factory entered into operation in April 1960. As Shirai had forecast, the initial activity was engine assembly. The Super Cub C102 with a self-starter also appeared in April and the bike's popularity grew yet greater. Its sister bike, the Sports Cub C110, made its debut in November.

In May, Honda underwent its ninth capital expansion. Its capitalization was now 4,320 million yen.

In July, Honda's R&D Center was given an autonomous status to become Honda R&D Co., Ltd.

In December, the company launched the CB72 Super Sports bike (a sister to the C72 put on sale in February). This motorcycle would go on to define the new category of sports bikes in Japan.

Super Cub production grew rapidly, passing the one million units mark as early as June 1961. In August of that year, production of all Super Cub models was transferred from Saitama to the Suzuka Factory, which continued in operation at full capacity as a mass production plant on a hitherto unprecedented scale.

The Suzuka factory in 1971, just 13 years after the first factory was built.

Honda had taken its first step toward mass production at the Yamashita Plant, just 330 m2 in area, in 1948. Now, thirteen years later, the full reality of its cherished idea had been achieved.

During those years, the company had consistently held to a course of self-determination and independence. Now, looking back at that period of time, it was revealed as an unending series of challenges. For that reason, it had been an era of dramatic change filled with repeated failures and successes. Nevertheless, the dreams embraced by Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa were brought to fruition by young people who pursued the same dreams with them.

However, Honda had not reached its final goal. Its unfulfilled dreams are to unfold boundlessly.

The generation of those who lived through the events of that period join their voices in unison, saying: "the young people of today will probably not have the same experiences that we did. Although the times may change, the basic Honda philosophy holds true. As we did in the past, the people of Honda today and in the future inherit it and pass it on to the ensuing generations. So long as this continues, Honda will not be just a major corporation. It will always go on being Honda. After all, youthfulness and dreams exist in every age."

Soichiro Honda quotes

“I enjoy working and it isn’t because I’m president that I would deprive myself of that pleasure!” Soichiro Honda.

“There are… qualities which… lead to success. Courage, perseverance, the ability to dream and to persevere.” Soichiro Honda.

“I got myself completely absorbed in my job as apprentice inventor. I let no one disturb my concentration, not even my friends with whom I enjoyed spending time and doing a thousand things. ‘Time for supper!’ My mother had to force me to come to the table, since my mind was elsewhere, my ears blocked. ‘I’m coming!’ I would answer politely and then get back to work. So she ended up by respecting my work and letting me finish what I had to do. Even hunger could not disturb me.” Soichiro Honda.

“When you fail, you also learn how not to fail.” Soichiro Honda.

“Success can be achieved only through repeated failure and introspection. In fact, success represents 1 percent of your work which results only from the 99 percent that is called failure.” Soichiro Honda.

“When I take stock of life, I realize how important the personal contact is, how much more they are worth than the invention of machines, because [people] allow us to expand our view of things and open up thousands of experiences which we would otherwise be unable to understand.” Soichiro Honda.

“I don’t regret the thousands of times I came home empty-handed, having lost all my ammunition and bait. When the days get as gloomy as that, then you know you will soon find the treasure…” Soichiro Honda.

“Hope, makes you forget all the difficult hours.” Soichiro Honda.

“In the lab, 99 percent of the people are working on lost causes. The modest percentage of success, nevertheless, serves to compensate for all the rest of the effort.” Soichiro Honda.

“A company is most clearly defined not by its people or its history, but by its products.” Soichiro Honda.

“I’d sooner die than imitate other people… That’s why we had to work so hard! Because we didn’t imitate.” Soichiro Honda.

“If you hire only people you understand, the company will never get people better than you are. Always remember that you often find outstanding people among those you don’t particularly like.” Soichiro Honda.

“You direct a garage or a business like you drive a bus. It does its round, stopping to pick people up, but it can’t make a long distance trip. Of course you can be happy driving the same route all your life. But I wanted to drive bigger and faster buses and see other places.” Soichiro Honda.

“If I’d had to manage my company myself, I would have very quickly gone bankrupt.” Soichiro Honda.

“I finally became an independent man, a real man, master of his legs, head, destiny, of his timetable and the risks he knew he should take.” Soichiro Honda.

“A diploma is less useful than a ticket to a movie.” Soichiro Honda.

“My biggest thrill is when I plan something and it fails. My mind is then filled with ideas on how I can improve it.” Soichiro Honda.

“There is a Japanese proverb that literally goes ‘raise the sail with your stronger hand’, meaning you must go after the opportunities that arise in life that you are best equipped to do.” Soichiro Honda.

“We only have one future and it will be made of our dreams, if we have the courage to challenge convention.” Soichiro Honda.

“Instead of being afraid of the challenge and failure, be afraid of avoiding the challenge and doing nothing.” Soichiro Honda.

“Many people only dream about success, while for me success is to overcome permanent failures.” Soichiro Honda.

“I could not understand how it could move under its own power. And when it had driven past me, without even thinking why I found myself chasing it down the road, as hard as I could run.” Soichiro Honda.

“The value of life can be measured by how many times your soul has been deeply stirred.” Soichiro Honda.

“Enjoying your work is essential. If your work becomes an expression of your own ideas, you will surely enjoy it.” Soichiro Honda.

“Never let your failures go to your heart or your successes go to your head.” Soichiro Honda.

“Pursue your own dreams.” Soichiro Honda.

“The day I stop dreaming is the day I die.” Soichiro Honda.

“Profound belief in something allows every individual to find an immense inner force and to overcome his or her failings.” Soichiro Honda.

First Customer for the Honda NSX.

The Honda Motor Company Ltd. is a Japanese public multinational conglomerate corporation primarily known as a manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles, and power equipment. Honda has been the world's largest motorcycle manufacturer since 1959, reaching a production of 400 million by the end of 2019, as well as the world's largest manufacturer of internal combustion engines measured by volume, producing more than 14 million internal combustion engines each year.

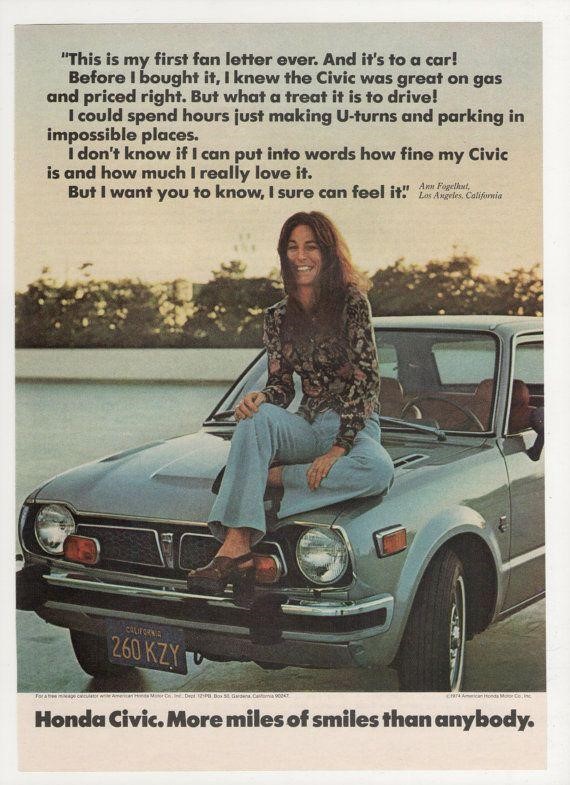

1974 advertisement Honda Civic 70s woman testimonial fashion style sports car.

1974 anti-sexism advertisement for the Honda Civic.

Honda became the second-largest Japanese automobile manufacturer in 2001, the eighth largest automobile manufacturer in the world in 2015 and the first Japanese automobile manufacturer to release a dedicated luxury brand, Acura, in 1986.

The F150 series brought the Honda cyclone to farming villages.