Gordon Murray. Those who are passionate of engines know that this name is linked to automotive innovation, Formula 1 and a car that has become legendary, the McLaren F1.

Murray is a genius of design and much more, possessing a vision of the future and a romantic spirit that allows him to create extraordinary objects that have a soul. One of the greats of motoring, who enjoyed winning and hanging out with others like him. He attended Formula 1 school, populated by the brightest, most passionate and goliardic minds.

The McLaren years were memorable for Gordon but at Brabham he had a fantastic time, along with Bernie Ecclestone. Two geniuses, two big boys of the F1 that was.

Bernie & Brabham – The Grand Prix Pirates. By John Brooks - TheSpeedhunters. 4th January 2010.

Bernard Charles Ecclestone…………. OK most of you might have heard of him, he's that rich guy who effectively runs Formula One's business and has done for the past 35 years.

The Brits amongst you might also know him as the Bad Guy who has made the British Racing Drivers' Club jump through hoops just to keep a British Grand Prix on the calendar and at Silverstone. Those who have to toil in the outdated facility might take a different view.

Actually this only tells a small part of the story. At his core Bernie is - and always was - a racer. During the 70's and 80's he owned the Brabham Grand Prix team. I am sure that back then, on any given day, you could have driven down Cox Lane, Chessington, past the factory and seen the Jolly Roger flying proud. They were the Jack Sparrows of the Formula One. Rock and Roll Racing, the Devil take the hindmost. In their pomp in the early 80s Bernie's Brabham crew were mavericks to a man.

The story of how Bernie acquired his gang of outlaws in 1972 had its roots back in the 50's. BCE was a pretty handy F3 racer who also had enough brains to realise that he would not make it to the top. He did try and qualify for the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix, having purchased the assets of the Connaught F1 team, he did not make it nor did he ever attempt it again. Aside from his many other business interests he managed the careers of drivers Stuart Lewis-Evans and, later, 1970 World Driver's Champion, Jochen Rindt.

Brabham was a constructor of racing cars founded in 1960 by Aussies Ron Tauranac and Jack Brabham. Brabham had won two World titles in 1959 and 1960 and wanted to capitalise on the growing market for single seaters. They did so very successfully becoming the biggest constructor in the world. The company also went into F1, winning titles for Jack in 1966 and for Kiwi, Denny Hulme, in 1967. Brabham retired after the end of the 1970 season and Tauranac soldiered on 1971 but the financial risk of running a race team at the top level was not something he was comfortable with. He sold out to Ecclestone and soon left the company. He eventually set up the Ralt operation which dominated Formula Two and Three for many years.

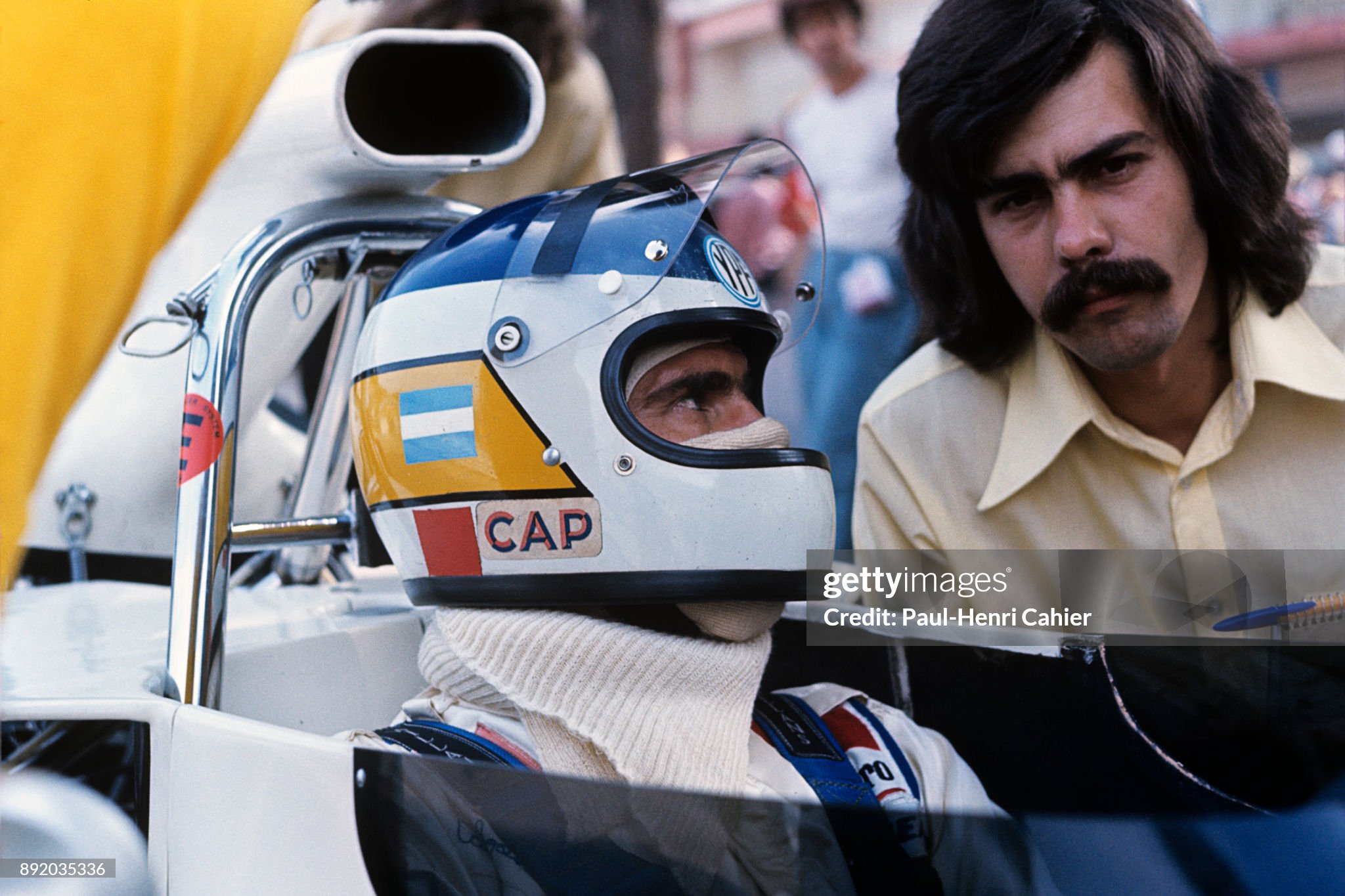

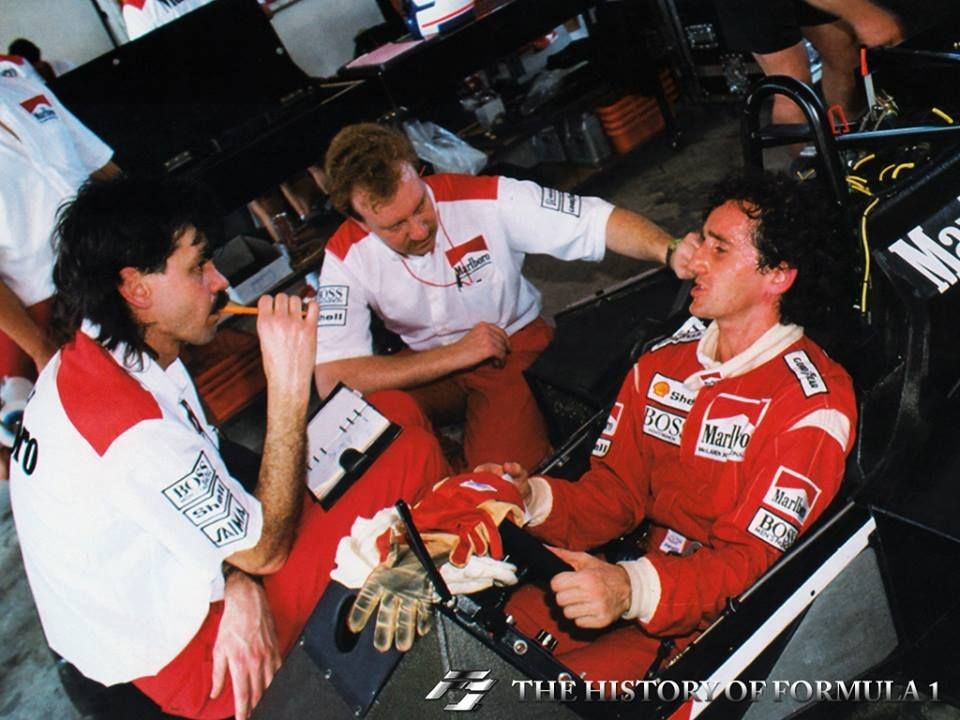

Monaco GP, 03 June 1973. Gordon Murray with Carlos Reutemann, Brabham-Ford BT42. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

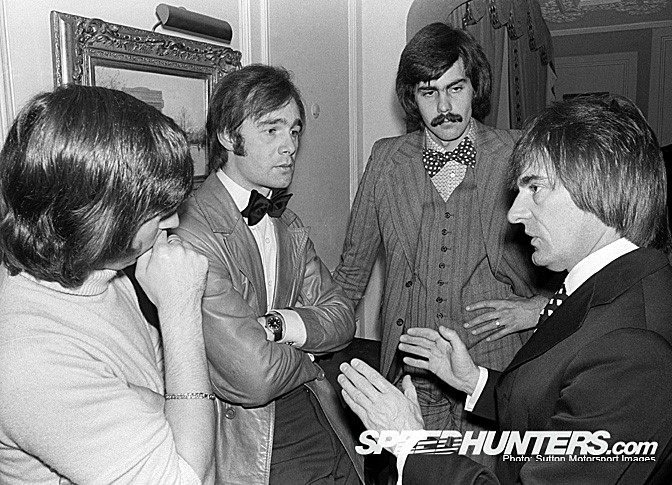

For 1973 Bernie beefed up the team by bringing in two men who would take the backmarkers right back to the top of the tree. Gordon Murray, one of the greatest car designers of the past 25 years and Mike "Herbie" Blash, who would manage the process. Above, Murray and Blash listen to the Bolt explaining to a scribbler the exciting plans for 1974. Did we really dress like that back then? Oh dear.

Murray's first design was the Brabham BT42 which was an improvement over the previous rag bag of cars and designs but even back then it took time to develop up a race winner.

In 1974 the breakthrough came, Carlos Reutemann took full advantage of a top line Gordon Murray design, the BT44 to win three races. The first here at Kyalami.

1974 Brabham BT44.

More success followed at Zeltweg and Watkins Glen and the team looked poised to take the fight to Ferrari and McLaren in 1975 for top honours.

Despite a revised car and sponsorship from the Count Rossi's Martini drinks company, Brabham did not live up to their potential. A win apiece for the two Carlos, Pace and Reutemann was not representative of the where the project should have gone. To be fair that year the combination of Niki Lauda and Luca di Montezemolo had inspired Ferrari to heights not seen in over a decade. For a change the Italians did live up to their potential and the church bells rang out often in Maranello.

It was around this point that the story became personal. Living in Surrey back then, there were three Formula One teams that were local to me………. McLaren at Woking, Tyrrell at Ockham and Brabham at Chessington. It will surprise some of you to learn that I used to drink in a pub in Shepperton at that time. The King's Head was a bit of a motor racing mecca, the landlord, Dave Cameron, having a long racing background. Herbie Blash started also frequenting as did WSR supremo Dickie Bennetts. Soon we had a good number of Brabham employees downing pints such as Harvey Spencer, Robin Day, Roly Vincini, Jerry Bond, Charlie Whiting and a whole bunch of other faces I can still see but whose names have slipped into the ether. Maybe a few less beers might have helped.

So Brabham became our team, we were a proud bunch of piss-artists, cheering on our heroes. Herbie, Harvey and the rest would bring back tales from around the globe and during the next ten years we followed the exploits of Watson, Lauda, Piquet etc. rejoicing in their successes and commiserating in their defeats.

Until I joined the sport full time I did not appreciate the effort that Herbie would go through to get us passes and tickets. With the responsibility of running a Grand Prix team he would always find a way to get us somewhere special during the races. He would also listen politely in the pub while we repeated the latest rubbish from Autosport or Motoring News, all the while knowing the real story. We have much to thank him for.

The team were always trying something different, here is the motorised pit trolley they built for the 1974 season.

No private jets back then, Bernie sits in cattle class with the rest of the boys on the way to America. There seems a bit more room than exists now, progress don't ya know? And that appears to be my old mate, Alex, lighting up a tab, how did the plane not plunge into the waters? The Stewardess is sporting branding from both Brabham and Ensign, she would have earned her money on that flight.

Hollywood came calling on Brabham during the making of the film, "Bobby Deerfield". Here Sydney Pollack, director of the movie, oversees some in car footage. Stars like George Harrison and Rod Stewart were regular visitors to the Brabham pits.

Even Royalty paid a visit to see Bernie and the Boys. HRH The Duke of Edinburgh swings by Silverstone back in 1975.

The exploits on the tracks were not the reason for the attention paid to Ecclestone. Since joining the F1 Circus he had become de facto leader of the pack. With March boss and ex-barrister, Max Mosley assisting, Bernie formed the Formula 1 Association. The aim was to create a package for the tracks and ultimately spectators, they would know in advance what they were going to see. The organisation would speak with one voice to the FIA on regulations.

Bernie could also see the potential revenue streams down the line if the Show was right. Sponsors, television and manufacturers all would come in time but it was the foundations that he laid in the mid-70s that allowed that to happen. He recognised that safety standards had to improve, drivers had to survive the initial impact of a crash and then should receive all the immediate assistance necessary to live. The manner of the deaths of drivers like Roger Williamson and Ronnie Peterson could not be tolerated, aside from the human cost, sponsors would simply walk away. Together with Professor Sid Watkins he ruthlessly pushed aside vested interests and other opposition to safety protocols, introducing measures that have saved the lives of many drivers right to this day. He brought a sense of organisation to the shambles that was race promotor's traditional approach. Common timetables for each event, control of passes and access would bring a sense of discipline to Grand Prix.

Ecclestone did not do all this with a sense of altruism, he could see the potential of the exciting, glamorous way of life and that with the right approach everyone connected with it could become rich, not least himself.

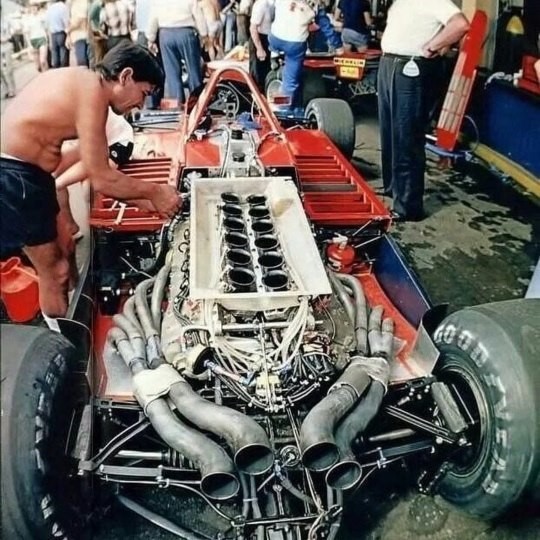

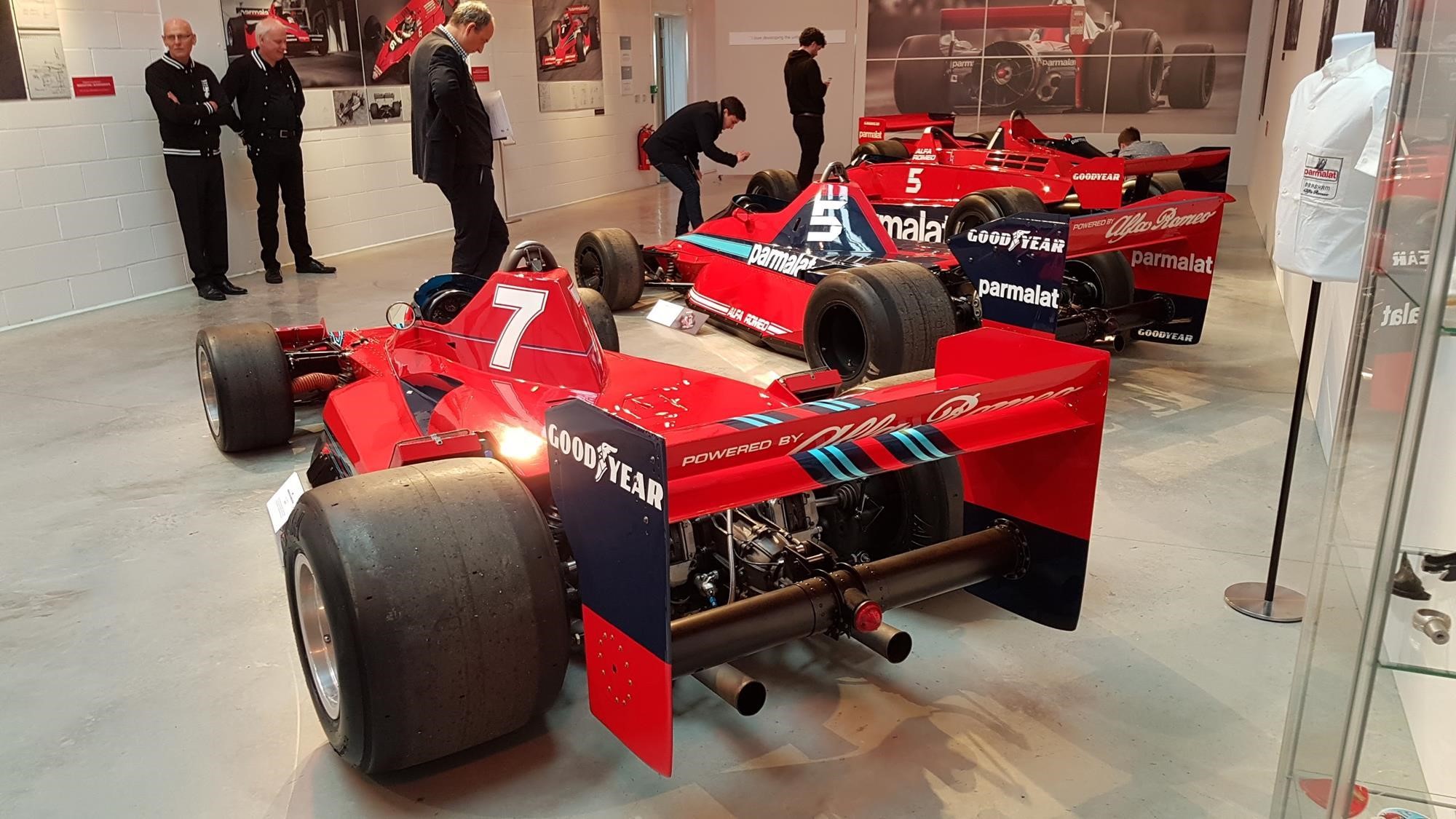

Back on track Brabham looked to get an unfair advantage by dropping the Cosworth DFV and getting Flat 12 power from Alfa Romeo. The deal meant free engines but there were hidden costs in terms of weight and fuel consumption that negated the extra horses.

The size and layout of the Flat 12 Alfa motor was increasingly a problem as the era of ground effects came into F1. Poor reliability in 1976 and 1977 hampered progress as did the death of team leader Carlos Pace in a plane crash.

For 1978 there were wholescale changes to the Brabham team. The leading driver of the time, Niki Lauda was recruited and Gordon Murray produced the radical BT46. Uniquely the initial car featured heat exchangers instead of radiators.

But in the real world they did not work so were replaced by conventional radiators after the first race. Reliability issues continued to plague the project with Lauda having a total of 11 engine failures alone.

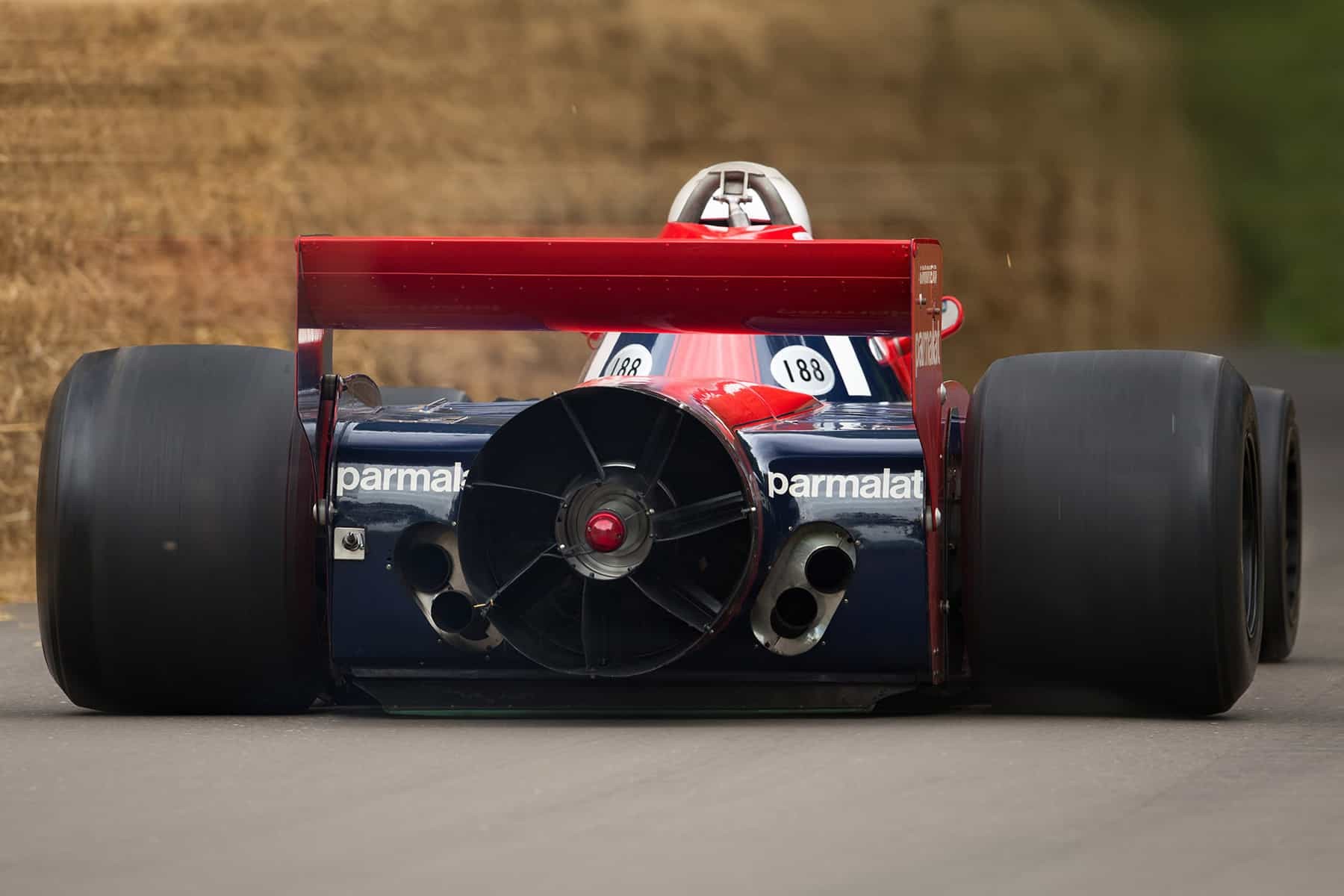

1978 was the year of the pure ground effect Lotus 78 and it was evident to all that Lotus would dominate the season. All the designers up and down the pit lane scrambled to copy the new technology, well, all except Gordon Murray. He looked to an earlier concept from the great Jim Hall and the Chaparral 2J which featured two fans at the rear to suck out the air from under the chassis, creating a pressure differential and thus downforce. Murray was forced down this route by the layout of the Flat 12 Alfa which precluded the creation of any significant Venturi tunnels under the car.

The BT46B appears at Anderstorp for the Swedish Grand Prix. It featured a large fan at the back of the car driven by the engine, thus the faster the engine revved the faster the fan went and the more air it blew, the greater the downforce.

The whole thing was justified as a means of drawing air over the rear mounted surface radiators but no one was fooled. The engine bay was sealed and there were Lotus style sliding skirts underneath. It had re-written the design book.

In the race Andretti in the Lotus retired so Lauda just drove off into the distance.

In the paddock there was mayhem and all the other teams protested the legality of the BT46B and the unity of the Formula One Constructors' Association was threatened. Ecclestone, with an eye on the long game, forsook the short term advantage of the Fan Car. The victory was allowed to stand but it never raced again.

With the Lotus 78 rampant and the era of ground effect on hand, Brabham persuaded Alfa Romeo to build and produce a new V12 engine to allow them to match the advances in aerodynamics.

The new engine layout meant that Murray could pen a full ground effect car, the BT48.

Gordon Murray and Niki Lauda stand beside BT48 racing car at Brabham factory.

This was the first car to have a reliable carbon braking system, this development is used by virtually all racing cars today.

There were other changes to the team with future star Nelson Piquet being signed up and then dramatically Niki Lauda walked away from the Brabham and the Grand Prix arena during practice for the Canadian race.

The relationship with Alfa Romeo was also at an end. Reliability issues still dogged the team and then Alfa decided to build their own chassis, DFV power was back.

Murray's elegant and effective BT49, combined with Piquet's developing talent, meant a Driver's Championship in 1981. Controversy followed this title as the team installed hydropneumatic suspension system to get round the FIA's minimum ride height rule of 6cms. This was measured in the pits but as soon as the Brabham was on track and at speed the system pushed the car back on to its skirts and voila ground effect was back but in a dangerous and unpleasant form. In a strange ruling the system was passed as legal by the FIA and everyone followed this practice. There were other whispers that Piquet's BT49 was seriously underweight on the track but nothing official was done. More piracy.

When Nelson Piquet won his first of three F1 championships in 1981 it also restored a Brabham car to the top of the pile following a 14-year hiatus. Murray and his colleague David North developed a hydro-pneumatic suspension system, which automatically held the car low once the natural aerodynamic forces had pushed it down, neatly circumnavigating a new rule banning driver-operated systems that had the same effect. That meant when the car was stationary it complied with minimum ride height measurements but would then compress at high speed.

I recall seeing Nelson take the title in Las Vegas that year. I was in Herbie's flat in Shepperton, courtesy of the delightful Lynne. They had the right TV station and were within walking distance of the King's Head after chucking out time on the Sunday night. So a mob of us were invited to cheer on our team, not sure what the neighbours made of it, nor am I sure that I was particularly productive the next day at work.

In parallel to the disputes on the track there was also an almighty row between the FIA in the form of the choleric President, Jean-Marie Balestre and FOCA, represented by Bernie and Max. After the FISA/FOCA war it was agreed that the FIA would set the rules and that FOCA would handle the commercial arrangements. This contract was known as the Concorde Agreement and it and its successors have governed the conduct of Grand Prix racing since. Never has the maxim “Follow the Money” been so apt. Control of that aspect meant eventual control of everything. Ask Max about it this year. Bernie still controls the money.

Gordon Murray and Bernie Ecclestone in 1982. Shutterstock editorial. Stock Image by Martyn Goddard.

Money, ah yes, it was clear that the days of chucking a DFV into the back of a chassis and going racing with a view to win had passed. Brabham and Bernie formed an alliance with BMW. Piquet embraced the turbo powered car, the BT52, to take the 1983 title.

This was the zenith for the Brabham team as they made a late charge for the Championship overtaking Alain Prost and Renault at Kyalami, the last race of the season. The car was arguably one of the most elegant designs in Grand Prix history, allied to the powerful BMW M12/13 4 cylinder. Renault were mightily embarrassed to see their German rivals take honours after having pioneered the modern era of turbocharging in Formula One.

More innovation from Brabham. The BT52 was designed with pit stops in mind. The fuel tank was marginal for most races and the car featured pneumatic on board jacks and quick-change wheel fixings. Pit stops were coming to Formula One, now they are commonplace but back then they pushed the pit crew into the limelight, able to change the course of a race. Who else but Bernie's Boys? Why risk problems in the pits? Wheels sticking, fuel lines catching fire, that sort of thing.

Simple really, the team had worked out it would be faster. Tanks were limited to 250 litres in 1983, refuelling meant that higher boost with an attendant rise in fuel consumption could be contemplated. Higher turbo boost led to more power and higher speeds, these 1.5 litre engines produced over 1000bhp. Lower weight meant softer, grippier tyres could handle the massive power output, a virtuous circle. Piquet driving like a real Champion produced the goods, so did the Pirates in the Pits. It was a great time to be a small part of all that. The celebrations back in the King's Head were prodigious.

1984 Brabham BT53 BMW.

Reliability problems blunted Brabham's efforts to retain their titles in 1984. In any case the game had moved on with a ban on refuelling eliminating one of the key cards in the 1983 triumph. Signing up with Pirelli in 1985 may have been financially sound in 1985 but the tyres were not truely competitive. Three wins in two seasons were poor reward for Piquet and so in his opinion was his retainer offer for 1986 from Bernie. He left Brabham for Williams.

It was good timing as for Brabham 1986 was a disaster. Elio de Angelis was killed at Paul Ricard while testing. The radical low slung BT55 was simply not up to the job and the team only scored points once, a long fall from the heady days of 1983.

Gordon Murray left for McLaren at the conclusion of the season. The spell was broken.

1987 was scarcely better. Ecclestone was pre-occupied with running FOCA and had lost interest in the team. BMW departed from Formula One back to sportscars. Bernie sold the team to a Swiss financier, Joachim Luhti, who was arrested on tax fraud charges in 1989.

Ownership of Brabham then passed to Middlebridge Racing but they too were involved in shady financial dealings with the notorious Landhurst Leasing company. In the middle of the 1992 season Middlebridge defaulted on their loans of £6 million from Landhurst Leasing. After a Serious Fraud Office investigation two directors of the finance company were jailed for accepting bribes for making further loans to the team. It was an ignominious end to the good ship Brabham.

Modern Formula One has no respect for past glories and Brabham joined such luminaries and former champions such as Team Lotus, Maserati, Alfa Romeo and Cooper Cars as now only existing as part of the heritage of Grand Prix racing.

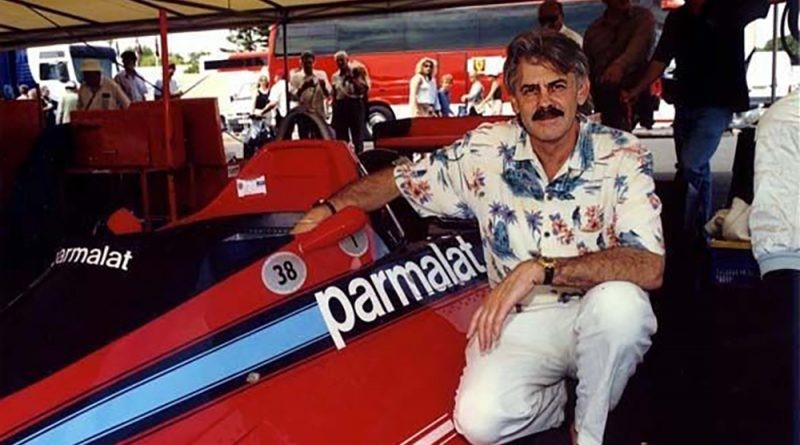

Gordon Murray and Bernie Ecclestone in 1980s.

Gordon Murray in the pits at Brands Hatch when he was design chief of Brabham F1 in 1980s.

For a few years the pirates down at Cox lane danced to a different beat to the rest of the grid, we could with more than a little of that spirit today.

Photos copyright and courtesy of Sutton Images www.sutton-images.com.

Gordon Murray Interview-1990. October 8, 2016.

Specification

Engine: “large” — “Naturally aspirated”

Cylinders: “lots”

Power output: “plenty”

Suspension, brakes and steering: “Formula 1 standard”

Availability: from 1994

Price: “more than anything in view today”

Manufacturer: McLaren Cars Limited, South-east England

If the specification for the forthcoming McLaren “supercar” looks decidedly vague, it’s not because the directors are trying to keep dark secrets. We have the assurance of technical director Gordon Murray on that; “when we’ve got something to tell you, we will. We may announce the name of the car at the end of the year. We may show you the concept at the end of next year.”

“What we will not do is give a load of hype, ‘we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that’ and we’ll go to great lengths to avoid it. Sure we’ll talk to you about what we aim to do, but we won’t give you any information that might turn out to be wrong.”

What strikes you in a conversation with Murray, the leading Formula 1 car designer of the 1970s and 1980s, is a nice mixture of futuristic concepts and old fashioned virtues. He, principal directors Ron Dennis, Mansour Ojjeh and commercial director Creighton Brown are jointly dedicated to producing the best sports car that modern techniques will allow, at a price that has no label. The McLaren will be hand-built, more expensive than anything envisaged today (certainly in excess of £500,000) and will be produced only as long as there are enough wealthy people to buy it, but on the other hand it won’t be a limited edition model.

And yet, while designing an esoteric car that will guide the volume manufacturers for the next decade, Murray has put his roots down in the past. He’ll emulate Henry Royce, Ettore Bugatti and Henry Leyland in their desires to make the finest cars of their era and he just might use some of their techniques as well, blending traditional materials inside the cockpit with carbonfibre and composite materials used for the chassis and body.

“The quality of the engineering will be Formula 1 standard,” Murray insists. “We’ll be putting a massive amount of work into vehicle dynamics, noise and vibration control, suspension compliance, outstanding performance and driver satisfaction. Above all, the McLaren will be designed to give maximum satisfaction to the driver.”

When all is said and done, though, the McLaren will also be a classic. “I don’t think that any cars in production today are destined to be classics. Let’s just say, though, that someone found a Mercedes 500SEL in a barn somewhere, in 50 years time. All the plastic mouldings are split and cracked, so how would you restore them? You couldn’t, unless you had the original moulds! The dashboard, the headlining, the underfloor covers, they’re all injection moulded.

‘The cars I admire were built in the 1930s, things like the Bugatti Royale I suppose. They were built from the real stuff, trees, leather, metals that you could reproduce. I don’t know how much of that we can use, but I’d like to try because I want the McLaren to be a classic for ever, if that’s possible.”

Mansour Ojjeh is the principle of Techniques d’Avant Garde (TAG), responsible for the V6 engine made by Porsche for McLaren Racing. He made a bit of folklore along the way by ordering the most exotic Porsche Turbo ever produced for road use (at the time, in 1983), half way between a road 911 Turbo and a 930 racer. “It had to be the most technically advanced, luxurious and fastest 911 Turbo ever” reported Rolf Sprenger, head of Porsche’s customer department in Stuttgart.

The spirit lives on today and it was mirrored by Ron Dennis, head of the McLaren International group. He and Ojjeh have determined that they’ll take the same path as Ferrari in establishing a manufacturing company, McLaren Cars, that will move to the centre of the group before the end of the Nineties. The group HQ will be based somewhere in south-east England and will have a test track alongside, as Dennis announced to a surprised audience some 18 months ago. Not surprisingly there are serious planning difficulties attached to the track and Murray and Brown have even considered running it underground.

McLaren Cars, with a staff of 29, occupies the same new building in Old Woking, Surrey, as TAG Electronics (staff of 80), which will soon be seen to provide an advanced engine management system to Mercedes for the C291 sports-racing car. It is reasonable to suppose that TAG Electronics will also supply the management system for the McLaren, though Murray won’t say so in as many words. There are lots of things he won’t say, in as many words. The concept of the engine was decided some months ago, but we wait to be told (a) the capacity, (b) the number of cylinders and (c) the power output. “What has been taking the time is talking to the people who’ll actually make it. I can’t even tell you if it’ll be made in England, but it’s an option.

“One of the options we’re considering is that it could be someone else’s design that we build, here. It will not be turbocharged, so it follows that it’ll have a reasonably high capacity because it’s got to have lots of power! The car’s power to weight ratio will equal that of a Ferrari F40, so you can get some idea of what I’m saying.”

This engine, definitely located ahead of the rear wheels, might be placed transversely in the style of the Lamborghini Miura (“that would be telling …. but think of the problems with the exhausts on the forward bank”). It will drive through a McLaren gearbox, perhaps with semiautomatic control.

The suspension will be conventional, it’s thought, brakes will be exceedingly powerful, the steering high geared, all to give the driver the feeling of handling a Formula 1 car on the road. Four-wheel drive has been ruled out, mainly on the grounds of weight and complexity, but also because Murray feels it shouldn’t be needed in such a car. If the owner wants to go out in the snow, he’s got an off-road vehicle in the garage. How about active suspension? “No, I’ve rejected that. I could look at electronic dampers, maybe, but not active suspension. It’s too complicated and too heavy. The McLaren will be very exciting dynamically and all the active cars I’ve driven have been the exact opposite”.

“They’re fine over bumps, that’s what they’re good at, but there’s no feel at all when you try to hustle them along, they actually feel unsafe. There’s no feel of contact patch at all. Active suspension’s valid in the same way as flying to the moon was valid, strictly from an engineering point of view.”

Compactness and intelligent use of the car’s overall dimension, is a gospel for Murray. For family transport he swears by a Renault Espace, while for fun it’s a toss-up between his Ducati motor cycle and his pristine, 1960 Lotus Elan which was built, as a matter of a fact, a year before he arrived in Britain from his native South Africa.

“Ordinary passenger cars are getting bigger and heavier and that’s an awful trend. If everyone drove around in Volvo 760s there’s be no room on the road for you and me! It’s ridiculous making these massive cars for people to travel around on their own.

“Sports cars should be dynamically exciting and enjoyable and to me that means compact, light and powerful. I have set a weight target, which I’m not telling you exactly and the McLaren will be very light … but it’ll be a hell of a lot safer than the big and heavy cars. You’ll see, one day, the amount of effort we’ve put into things like visibility and controls. We’re on our third pre-production buck at the moment and we’ve had several people working on controls for seven months now.”

The choice of wheels and tyres could be a major headache for Murray and for styling chief Peter Stevens, who joined McLaren earlier this year after completing the new Lotus Elan. Ultra-wide wheels, as Murray knows all too well, are the enemy of everything he wants the McLaren to be. They reduce comfort, they increase rolling resistance, drag and unsprung weight, they cause problems with suspension geometry and camber change control, they increase the turning circle.

“However, a car with such high power to-weight ratio needs a lot of rubber on the road. If there isn’t enough you’ve got problems. You’d have to go to a harder compound and that means you’d lose grip.”

Murray’s ideal sports car, the original Lotus Elan, managed brilliantly on 4½ inch rims, the same dimension as on the Austin A35 saloon, but while the future McLaren won’t go down to that dimension, it certainly won’t have full-size Formula 1 wheels either. Small really is beautiful in his book. Looking to the future, Murray agrees that there will be a successor to the `supercar’ and it may not be a sports car at all. “I’ve got a very, very good design team here, hand-picked guys and I never want to let them go. Once we’ve designed this car we’ve got to go on to the next. So yes, we will have to have another programme and soon we’ll have to start talking about it”.

“The way the world’s going, this might be the ultimate and final statement in supercars. Personally I’d like to build a proper town car. Building a sports car is fine, but sports cars are for fun. We should learn something from Japan, with the micro car. A small sports car is highly efficient and a town car is a logical progression.”

After spending 20 years in Formula 1 racing, Gordon Murray has no withdrawal symptoms at all. “I have found this entire exercise very fascinating. The design of the car is only one small part of setting up an operation like this. We’ve been talking about marketing, servicing, customer requirements and the like for the past three years and I’m immersed in that. We’ve got some unique ideas in these areas, and the whole thing is very refreshing”.

“The best market researchers in the world couldn’t tell us anything we don’t know already, because Creighton and I have been mixing with our potential customers for the last twenty years. We know their profiles, we know what they want and what they don’t want. It’s not always the things you’d expect. It’s more often the little things they’d like to see included, or left out. Basically, the McLaren will be hand-built, in the way that a Formula 1 car is hand-built. Everything you can see and touch will be designed and made specifically for this car, even door handles and locks. Things you can’t see, like windscreen wiper motors, we’ll look around and buy the best available. We’re not going to be bloody-minded about making everything ourselves, we’re not going to re-invent the wheel, but there will be no compromises whatsoever”.

“Ordering and owning a McLaren is going to be a very personal experience, going back to the 1930s again I suppose. It it’s going to be the best car that money can buy, we’ve got to match that in every way. There can be no breakages, no things falling off and our service has got to be second to none.”

Within a few weeks McLaren Cars will announce the name of the supercar. At the same time, or soon after, more information will be released about the engine, when a contract has been signed. At the end of 1991 we may see the concept, a year later the first working prototype, while the first customer car should be completed by the end of 1993. It all sounds rather relaxed, but in reality there’s an enormous amount of work to be done in a fairly short space of time. The whole concept of the McLaren supercar would sound like dreamland to anyone in the motor industry, yet the project has a simple beauty; if only one customer, possessed of almost infinite wealth, wanted to purchase the unique machine, McLaren would make it then turn the page, get on with something else. They’re in another world.

Gordon Murray: the genius lent to Formula 1. 20 August 2018. By David Bianucci.

Formula 1 designers are people with extraordinary preparation and ability. The best of them are paid millions of euro a year, like the designers of the America's Cup boats, like the top football coaches.

The technical director decides the basic lines of the project, the idea of how to solve the main problems of the definition and positioning of the fundamental components of the car. It’s easy to imagine them as nerds, perpetually sitting at the desk or intent on looking at mechanical means of all kinds, in search of the brilliant solution. Instead, they are often bizarre personalities, with many interests, of which perhaps Formula 1 is not even the most lively, simply capable of going beyond the limits and thinking completely new "things".

The image of the absolute genius of the 1980s is certainly represented by a tall and lanky South African, with long hair and a mustache, more like a rock band bassist than a distant drawing board animal. The South African in question is called Gordon Murray, now he has his own consulting firm of sports cars design (a passion that has supplanted that for single-seaters for quite some time) but, between the end of the 70s and the 1980s, he conceived the most innovative cars on the grid with ingenious, futuristic solutions, more often winning than being an end in themselves but, almost always, “beyond” what others had imagined.

Let's see some of them. The '78 Brabham BT46, powered by Alfa Romeo and driven by Niki Lauda, fleeing from Ferrari. Murray designs a sharp car, with a reduced front section, in which the side pods simply do not exist and the radiators (usually mounted, in fact, in the side pods) are "touch-sensitive" and do not impact the resistance to progress. Unfortunately, in the same year, the discovery of the ground effect explodes, that is the use of the surface under the car to accelerate the flow of air and increase downforce and the ground effect works better if the side pods are big. Murray tries to oppose a brilliant fan, passed off as a gimmick to cool the engine and instead mounted behind the rear wheels to suck air from the bottom of the car and recuperate downforce. His idea was rejected for safety reasons after only one Grand Prix, Sweden '78, won by Lauda.

In 80 and 81 Murray's car wins grand prixs after grand prixs and even a world title, with Piquet, but at the end of 82 the ground effect created thanks to the skirts was banned. The side pods, again, are no longer needed and Murray invents the Brabham BT52, one of the most beautiful cars in history. The radiators are just in front of the rear suspension, V-mounted, the side pods no longer exist, the suspensions are push rod instead of pull rod like on most other cars. The car is a real arrow. The power of the BMW 4-cylinder turbo (finally also reliable) and the skills of Piquet do the rest and it is again the world title.

In the following two years the project changes little, but the McLarens of Lauda and Prost dominate and, in 1986, Murray decides to create something really new. The BT 55, called “sole”, is the lowest car in history. The low center of gravity, obtained thanks to the lying down on one side of the BMW engine and the lying down position of the driver, should allow a very low roll sensitivity and a much lower aerodynamic penetration than other cars. At the moment of presentation the car leaves everyone speechless. In the starting grid the BT55 disappears behind the other cars, so much it is reduced in height. In Monte Carlo, if you put yourself in a position to see the climb towards the Casino, on one side you see the cars pass by but of the Brabham you only see the rear wing pass, everything else disappears under the guard rail. Impressive. Unfortunately the car is a failure: the "lying down" position creates many problems for the BMW engine and the German manufacturer is abandoning Formula 1 and doesn’t really want to solve them. In May Elio de Angelis dies during practice (the shape of the car has nothing to do with it) and the team falls into drama. The project dies slowly and Murray leaves Brabham at the end of the year.

Gordon is hired by McLaren where, in 1988, he redeems himself by designing the most successful car in the history of the top flight. Stubbornly convinced of the goodness of the idea, Murray actually reintroduces the BT55, but this time the engine is the Honda and there are no engine problems.

Alain Prost describes the behaviour of his McLaren with Gordon Murray (left) and engineer Neil Oatley. Formula 1 history pictures.

The drivers are Senna and Prost. Everything is just perfect. The McLaren MP4 / 4 wins all the grand prixs of the year, except Monza, where Senna is rammed by a lapped when he is first with a large advantage and few laps to go. The '88 McLaren is the pinnacle of Murray's career. More and better than that, honestly, it can't be done, especially since McLaren wins with the same car (apart from minor modifications) until 1991.

Gordon, who has been around for about twenty years, decides to devote himself to road cars. And he still does. With excellent results, given that his creations are real works of art intended for millionaires who can buy them.

I have a curious memory of Murray: at the awarding of the “Autosprint gold helmets”, in Bologna in 1983. He is also on stage to receive the prize for the world championship just won. A fan hands him a very nice model of his BT52 from under the stage, to show it to him. Murray begins to look at it from behind and in front, from above and below and, even before the interview is over, he greets everyone and takes it away, considering it a gift to be analyzed. The poor fan has to chase Murray behind the scenes to get it back.

Journal: F1 and road car design legend Gordon Murray receives CBE from Prince William. By News Desk. May 2, 2019.

F1 and road car design legend Gordon Murray receives CBE from Prince William.

Formula 1 and road car design legend Professor Gordon Murray has been presented with a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) by the Duke of Cambridge, Prince William. The ceremony at Buckingham Palace recognized Murray’s contribution to motorsport and the automotive sector over the last half century.

Murray began his F1 career with Brabham in 1969 and went on to design some of F1’s most iconic and often beautiful cars there, such as the multiple race winning BT44, the BT46B ‘fan car’, the 1981 championship winning BT49 – which that year benefited from Murray’s hydraulic suspension to get around rules intended to eliminate ‘ground effect’ and the cult classic dart-shaped BT52 that took 1983’s drivers’ title. Murray was also responsible for reintroducing planned mid-race refueling and tire change pitstops to modern F1, bringing them in from mid-1982. Murray left Brabham in 1986 and joined McLaren the following year for a spell of extraordinary success. The famous McLaren Hondas won drivers’ and constructors’ championship doubles every year from 1988 to 1991 inclusive, with in the first of those years the MP4/4 winning 15 of the season’s 16 races. In total Murray’s F1 cars won 56 grands prix, three constructors’ championships and five drivers’ championships.

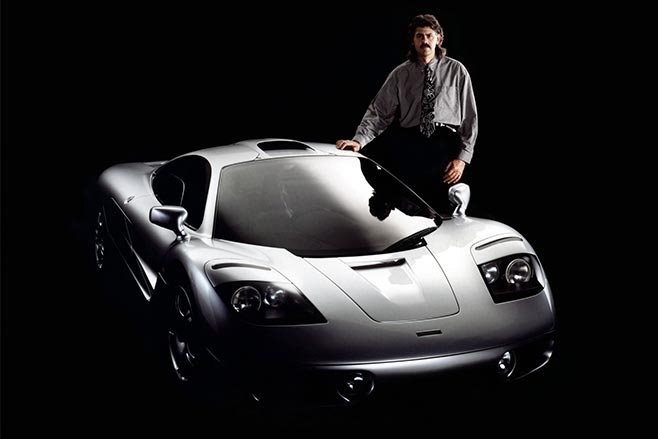

In 1989 Murray switched his attention to road cars and began work on the McLaren F1 as McLaren Cars Limited’s first project. And, although Murray initially had no intention for the car to race, a racing version of the machine called F1 GTR won the 1995 Le Mans 24 Hour race as well as took two world sports car championships; the car later morphed into the Mercedes SLR McLaren. In 2007 Murray formed his own new company for the design, engineering, prototyping and development of vehicles, called Gordon Murray Design Limited. The company has a global reputation as one of the finest automotive design teams in the world and is responsible for an innovative and disruptive manufacturing technology called iStream, which aims to cut carbon dioxide emissions using technology derived from F1 and using it Murray plans to revolutionize high-volume car manufacturing. Murray also shortly, on May 14, will launch a new book titled ‘One Formula’, in which he charts his distinguished career in detail.

“Receiving a CBE from Prince William is one of the highlights of my life – right up there with Formula 1 world championship wins or creating the world’s fastest production car,” Murray said. “The Gordon Murray Group is about to embark on an exciting new chapter, with ground-breaking innovation once again driving our growth. Energized by this accolade I can’t wait to continue the journey, supported by a dedicated and hugely talented team.”

Images courtesy of Gordon Murray Design Ltd.

“Gordon's thinking outside the box also revived refuelling pit stops and pioneered a trick suspension that legally defeated the rules. It was that thinking that took him to McLaren, to produce not just a succession of Championship-winning Grand Prix cars but, in my opinion, the greatest road car of all time and winner at Le Mans, the fabled McLaren F1 three-seater.” Murray Walker CBE

Gordon Murray: “I need Mercedes to lose two races this year”. May 14, 2019.

McLaren MP 4-4.

Gordon Murray, the Formula 1 design legend who oversaw the sport’s most successful car to date, hopes for purely personal reasons that someone can beat Mercedes at least twice this season.

The South African was technical director at McLaren in 1988 when Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost won all but one race, 15 of 16, with 10 one-two finishes, 15 pole positions and 10 fastest laps.

That achievement remains the closest any team has come to a perfect year, although Mercedes almost did it in 2016 with 19 wins and 20 poles out of 21.

Even three decades later 72-year-old Murray, who also designed the 1990s McLaren F1 supercar and is now promoting a flat-packed plywood-bodied vehicle for the developing world, still feels a proprietorial pride.

“I need Mercedes to lose two races this year,” he told Reuters laughingly at the Royal Automobile Club launch of a two-volume, 948-page opus that covers in detail his 50 years of car design. “Every season I go: please don´t win two races. It doesn’t look like it this year.”

In 1988 McLaren lost only at the Italian Grand Prix, an emotional victory by Ferrari’s Gerhard Berger a month after the death of Enzo Ferrari.

“Alain Prost had an electrode fall off a spark plug, which I´ve never had in all my years in racing and Ayrton (Senna) tripped over a backmarker in lapping,” recalled Murray. “Otherwise it would have been a clean sweep.”

Mercedes have won the first five races in one-two formation this year, with five times champion Lewis Hamilton leading Valtteri Bottas three times and looking a cut above the rest.

They have been on pole four times, with a fastest lap each and people are increasingly asking if they can go all the way.

The closest Mercedes have come to losing so far was in Bahrain, when Ferrari’s Charles Leclerc led from pole position but was denied victory by a late engine problem.

“They (Ferrari) threw the race away,” said Murray. “They should have won that one. But they (Mercedes) need to lose two races (for me) to keep my record. So I´m watching. They´ve got a good chance to do it, I have to say.”

Steve Nichols was chief designer of the McLaren MP4/4 car but Murray can claim significant ownership, having brought plenty of ideas from Brabham where he also produced the unique and highly controversial BT46B with a large fan at the rear.

The MP4/4 was 1-1/2 seconds a lap quicker than rivals but Murray said the year stood out also for work done behind the scenes.

“I went through a failure list from the previous era before I arrived and found out why things were failing and fixed that and introduced post-race meetings and analysis tools… they didn´t have anything,” he said.

“So it wasn´t just the design of the car and the drivers. We had the perfect year. I made the cars very reliable.”

Murray still follows Formula One and was at the Bahrain Grand Prix, but feels it needs to do “something fundamental” to create more excitement and better racing.

“They really have to,” he said. “It´s a drivers´ championship first and foremost.”

Murray would like to see less downforce, with tiny wings front and back and more design freedom in the centre of the car. “We just had so much fun in the days when you could think of an idea, build the parts the next week and go a second and a half a lap quicker at the next grand prix,” he said.

“These days its hundreds and hundreds of hours in the wind tunnel and then a tiny little front wing change and you find two-tenths of a second. I find that really difficult to get excited about.”

Can Gordon Murray — one of the most innovate formula one engineers in history — create an exciting city car? Piero Che Piu. September 11, 2019.

Gordon Murray in an Exhibition of his Formula One cars.

In Durban, the largest port in South Africa, a teenager skinny as a flagpole walks through its streets waiting for the weekend. Those are the years of apartheid: even the beaches are divided by skin color, yet that discussion about race doesn’t interest him. The only thing worthwhile in that place happened on Saturdays. An event worthy of his attention. A challenge of speed. A car race.

His father was a Peugeot mechanic that helped to transform streetcars into beasts of persecution. Every weekend his son accompanies him to saw the drama that occurs when a group of cars steps on the accelerator at the same time. Isn’t the mechanics of the vehicles what make his heart pound. In a country where buying a car was a luxury — and even more, a racing car — the teenager Ian Gordon Murray didn’t just want a vehicle to impress girls. He wanted to become a racing driver.

The Ford Anglia his very first custom made car. One Formula - T.1 Exhibition.

Gordon Murray - One Formula - T.1.

In the course of his life, he will face similar hardships. Impossible-to-solve problems that for others are more than a reason to quit, for Murray was the fuel he needs it to start working. At seventeen, the mechanic’s son decided that the most reasonable thing to do was building a car made with spare parts. Well, scrap pieces. Before he turns twenty-one, Murray’s car will make him the South African champion of the category.

Fifty years after his first car, Gordon Murray has retired himself for professional car driving and has become the most celebrated car designer of the past century. A mechanic engineer behind each of the nuts and bolts of the race cars that made Nelson Piquet and Ayrton Senna champions of Formula One. The craftsman who designed the best streetcar ever put into production: the Mclaren F1 (and even wrote the manual by himself). The son of a mechanic, for his project number 25, decided to be inspired for another impossible problem. While most manufacturers try to sell us the cars of the future, Gordon Murray would create the first one with a future. That difference between both types of vehicles is so abysmal that if Murray’s T25 get mass-produced, he would be placed at a similar height of Henry Ford. Like the T model from the beginning of the last century, the T25 has the potential to change city transportation.

Road test of the T25. The first model of the city cars series.

The T25 prototype doesn’t have an engine that runs on hydrogen, nor is it so smart that it drives alone or works on electric batteries. It is the smallest, comfortable, light, crisp and cheap gasoline model ever designed. Murray calculates that if the planet’s automotive fleet became only 10% lighter, the impact in the next decade would be higher than all the alternative solutions presented so far. It is not the wild claim of someone who promotes their product as salvation against the greenhouse effect. It is a simple logic of Formula 1, something lighter saves more and pollutes less.

Gordon Murray and his team (many of whom work with him since McLaren’s 1) took 18 months to create the perfect commuter car: cheap and a cool enough to don’t look like a miser. They disarmed several vehicles on the market and weighed each of their pieces to find some way to make it lighter part by part. Its result was so original that at the moment it was revealed to the public caused a massive wave of people scratching their heads. What is this? Smaller than the smallest cars in the market yet it is for three seats. Thin enough to park three in one single spot, has also ended the debate between having three or five doors: it only has one and it opens forwards. The T25 can ready to sell on both sides of the Atlantic without modifications: the wheel installed in the middle. James May, the presenter of the Grand Tour, test it and reviewed as a weird comfort. The frame was solid and it was nothing but fun. In the speed testings results, the T25 leave behind their Nissan adversaries. It’s a car… it doesn’t look like a car.

The 25 has sprung a collection of city cars that are ready for production.

While motor shows offer increasingly clean, smarter and fully equipped versions of cars every year, they continue to be built with heavy steel panels. The only thing that has changed the assembly lines since Ford is its gigantic size and the location of its workforce. Often, city cars look like summaries of bigger models, because it is the only way to make as profitable as an SUV. The factory does not distinguish between a city car that one prepared to discover the unexpected in a dune. Murray thinks that the problem of pollution not only is also a manufacturing issue. How do we build small, tremendous and profitable cars for crowed and polluted cities?

Being in need is fertile territory for the imagination. Where common sense saw a shattered Ford Anglia, half a century ago Gordon Murray selected the front of his first car. He also learned to weld while shaping the bird-shaped chassis of English brand Lotus that also inspired the vehicle of the anime “Speed Racing.” Murray imagined and built his pistons, his gearbox, his exhaust pipe. He created a device which allowed a flow of air to enter to the engine granting him more horsepower. Those were innovations born of necessity. We only deserve the things we can dream of. His car would be fast, or it wouldn’t be. It took a couple of years to finish it. He called IGM by its acronym. That car was the first chapter in Murray’s design philosophy: if you run into something that doesn’t exist yet, you should get in a good mood. Suddenly you are Neil Armstrong walking on the moon.

The offices of Gordon Murray Design in Surrey, England, are a mix between a mechanics garage and a design studio. A place where engineers, mechanics and designers coexist to build four wheels masterpieces. Across the office, pinned on walls and boards, are plans of the car printed in real size. Rather than see them in screens, he prefers this analog solution that focuses on real-life experience rather than a look created by computers. This method allows the team to see the future car with the eyes of someone who stops in the parking lot and take a closer look at the neighbor’s new car.

Murray’s office has a scientific process to pinpoint the key issues and a hands-on approach to solving them. Before getting to the drawing board, his team had dismantled the bests city cars in the market while evaluating design, weight, performance, building process. After that, they build a prototype that suffers change after change after a few test laps. Then Murray enters the kingdom of details. Big car markers are often designed in one country to be built in another. Although robot arms can be precise, they don’t take an afternoon discussing the best way to build a door. That’s what makes all the difference. While designing a car, it may be reasonable to discuss the right placement of a window or the correct height of the driver’s seat. Murray’s goes further convinced that even the tiniest modification would change the experience of the car. “A window twenty millimeters taller can make you sit in a more spacious cabin,” explains Murray as if it was the more obvious in the world.

McLaren F1 is part of the exhibition. Behind a photo of the original team.

The origin of many of his design decisions comes from intuition. Is this felt good? Was it horrible? Every detail is an opportunity to improve the experience of the car. In the end, the accumulation of those minimal, almost imperceptible details, creates the experience of a supercar. However, Murray never forgets that the primary purpose of a car is to be on the road. Often, many of those design details also improve the performance of a vehicle. This duality is something he learned in the efficiency school of the old Formula One: looks may get attention but is performance what motorheads remember. For many fans of his work, the Mclaren F1 is the most elegant expression of this car design principle. An illustration of quality and originality, without any previous model to base the designer got a carte blanche. Murray designed the car along with only seven people. Small teams are easier to handle, yet it also reveals that this man who wears flowery shirts is a perfectionist who does not delegate easily. For many, it is the best streetcar ever built. The McLaren F1 goes at 241 miles per hour, 627 horsepower and it’s so light that eight people could lift it. It is a car that in its race version, occupied the first five places of the 24 hours of Lemans, the most famous resistance championship in the world. Jay Leno, one of its owners, teases to say that driving a McLaren F1 is like having sex with an aerobics instructor. You go one hundred an hour and she will ask you if you’re done. It will always be better than one. Can he replicate that kind of success in a car for the city?

The T25 is an invitation to think from the side of a problem that arises every time we stop at a traffic light. There are too many cars in this world. It is ridiculous to think that in the short term we will stop using them. Ninety-five vehicles are produced every minute around the world, 50 million in a year. But the most painful thing is not the bottleneck that causes that production. It is 80% that is made up of large models — the majority occupied by loners trying to get somewhere.

Workers of Murray Desing, carrying the frame of a new prototype.

“This has stopped being fun,” declared in a documentary dedicated to his years at the top of Formula One and the development of T25. He meant that if things went on like this, a motorized world would not be sustainable. However, his idea should excite car fans and manufacturers. Because Murray does not plan to build the T25, but the license of a lighter car factory.

It’s called iStream and it will be the only car factory that doesn’t use steel plates to create the chassis. The cars will be constructed from steel tubes, which are cut and folded with relatively cheap machinery. New parts will be working with recycled carbon fiber, a material that has passed the European safety tests. Painting and assembly do not require robotic monsters that take up space and consume energy. According to Murray’s calculations, the factory would have an extension of 14,500 square meters, just a fraction of an automotive city and produce about thirty cars per hour. Reduces the carbon footprint of each car, but at the same time makes the manufacture of this type of vehicles profitable. By having moving parts, it also makes spare parts cheaper by increasing their resale value. It also generates more work, with a low impact on the environment. Cities will have cars that pollute less, Murray imagines a range of models that fulfill functions of cargo, public transport and even sports. However, the best idea does not always come true.

Gordon Murray is a challenge hunter. Tired of winning in South African competitions, he wrote a letter to his hero Colin Chapman. The founder of Lotus, who dominated the first years of Formula 1, not only answered the message but also offered him a place. Chapman was one of the first people to take advantage of the union of design with engineering. Perhaps he saw in Murray a unique prospect. Someone who naturally turned efficient mechanical solutions into pieces that looked attractive.

The newcomer Gordon Murray would achieve great height with the Brabham motor team at the beginning of his career in Formula One. One Formula - Brabham BT44b.

A December 1969 the fairy tale became a horror. When Murray arrived in Norwich where Lotus was left only to discover that he would not work for Chapman. Lotus was firing staff. For many months I lived in a cold and unemployed apartment. He had no money to live, less to drive. One day he decided to go through the Brabham headquarters, which was still run by its founders. One of them Ron Tauranac confused him with a drawing applicant and hired him. But the team was more focused on selling cars for smaller categories than conquering Formula 1. In the early 1970s, it was bought by Bernie Ecclestone, one of the few suggestions he received from Tauranac was to fire Murray. Ecclestone dismissed the entire team and left Murray with twenty-five years as head of the Formula 1 team. After a decade of work, the result was two world championships in 1982 and 1983.

But also a period of innovation. He was the first to use a brake system with carbon shoes. The first to use carbon fiber panels. The first to use the wind tunnel (and the first to complain about the obsession with him). He devised the hydropneumatic suspension that allowed the car to duck more at high speed and generate a more significant ground effect. He was also the first to add a useless valve to the body, to prevent the competition from discovering the trick. In 1982 he changed the way the gas tank was filled, which allowed him to take advantage at the beginning of the races taking advantage of a lighter car. It also improved the change of tires by adding vertigo to pit stops.

In an interview for the book ‘Motor Sports Greats: in Conversation,’ the author took a peek of Murray’s notes while working on the McLaren F1. The writer describes them as too perfect to be on the fly, but they were. We are used to seeing the creativity associated with chaotic personality and not with neatness. Murray has kept all those old notebooks since he was a student. One day, Murray has told, he attended a one-day mechanical engineering course and, by the end, he had to design a three-horsepower stationary engine. The son of a mechanic drew an engine that only had three moving parts that were not used for car racing but would be perfect for third world countries. He would like to make his prototype someday. Perhaps his next challenge is to create an engine that changes the lives of millions of people.

Who is Gordon Murray? About the man behind the GMA T.50. By Chris Thompson, 06 August 2020.

The designer’s career highlights are more than just the McLaren F1.

"I would have left it with the F1. But now there’s a point to be proven," Gordon Murray said in a Goodwood interview in 2014, well before the Gordon Murray Automotive (GMA) T.50 was public knowledge.

Now, Murray’s point, that “you can still do a great driver’s car with an internal combustion engine and pure engineering,” is about to be proven, or so we expect from the man who created the car often considered to be the greatest supercar of all time.

But the McLaren F1 isn’t the only thing on Gordon Murray’s resume, even if it may be the biggest highlight.

The South African-born Ian Gordon Murray is a British citizen, having lived in England for most of his life and now resides in Surrey, not far from his current Gordon Murray Design and GMA workplace.

But, even before his move to the UK, Murray had gone on to build a race car, his IGM Ford.

The car was a 1-litre Anglia engine-powered bespoke car, though it used some body parts from a Lotus 7, meaning it looks somewhat like a Caterham kit car. Murray even raced it himself in South Africa’s National Class in 1967 and 68.

Did you know the McLaren F1 also had small aero fans?

The next year, 1969, Murray was at Brabham, where he would go on to create (under Bernie Ecclestone’s management from 1973) a legacy carries through to the T.50: his use of fans.

The Brabham BT46B was reportedly described by then Brabham driver Niki Lauda as uncomfortable to drive due to its incredibly high cornering speeds, achieved by a large rear-mounted fan drawing out air from underneath the car.

Lauda would go on to race only once with the ‘fan car’ winning the 1978 Swedish Grand Prix upon its debut before the car was banned. This win is just one of 50 Grands Prix that ended with a Murray-designed car crossing the finish line first.

A couple of years after the fan car, Murray’s time at Brabham resulted in two F1 drivers’ championships for the team in 1981 and 1983 with the BT49 and BT52 respectively, both with Nelson Piquet taking out the title.

The most dominant F1 cars.

The team’s fall from dominance coincided with its move away from Ford engines, with Murray’s yet-to-be-realised future further proof that his designs weren’t the cause of Brabham’s decline.

At McLaren (from 1987) Murray would thrive both as technical director of the F1 team and as the man behind McLaren’s road car brand from 1991.

Murray’s work as the technical director for the race team under chief designer Steve Nichols allowed McLaren to secure three consecutive championships in 1988, 1989 and 1990, as well as providing the first drivers’ championship for Ayrton Senna in a McLaren MP4/4.

After his time in Formula 1, Murray turned to road cars, taking much of his learnings from the track and a philosophy for lightweight, engaging sports cars. This, of course, resulted in the sometimes confusingly named McLaren F1.

The McLaren F1 (1992-1998) still retains the title of ‘the greatest sports car built’ among many, with its kerb weight similar to a modern Mazda MX-5 and its power outputs from a BMW-derived atmo V12 in the same region as a new McLaren 600LT. It was faster than the Jaguar XJ220, stealing the record for fastest production car by more almost 40km/h at 386km/h.

Of course, racing versions known as F1 GTRs were also incredibly dominant, achieving many victories including upon its Le Mans 24 Hour debut in 1995.

How to service a McLaren F1.

Murray also worked closely on the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, but it’s the work he’s done since then that he hopes will change the way cars are designed and built.

Since 2007, Gordon Murray Design has been developing what seem to be revolutionary ways to simplify and improve car manufacturing. Called iStream, the system intends to create cars that are lighter and more environmentally friendly without sacrificing safety or comfort.

Given the T.50 is about the size of a Porsche Cayman, fits a 4.0-litre V12 and has three seats, there’s no doubt Murray is onto something.

Here it is: The GMA T.50 revealed

Murray also has a small truck, using iStream tech, in mind for Africa to help transport food, water, medicine and other goods. Called the OX, it’s intended to be more affordable and its lower weight will allow it to be more efficient transport.

“It could change the lives of tens of thousands of people,” he said in an interview published in MOTOR’s March 2020 issue.

“Creatively, I think I’m in the best period of my life. With iStream, I can take all my learnings from Formula 1 and try to give it back to the everyday motorist, with all the safety and lightweight benefits it offers."

Personally, Murray’s love for lightweight is evident in his garage. His daily driver is a new Alpine A110, calling it the best ride and handling compromise he says he has experienced since the Lotus Evora though he wishes the A110 was manual and N/A, while his favourite sports car is his 1970 Lotus Elan.

Of his 45 cars, 35 weigh less than 800kg. If that doesn’t say something about Murray, the fact he’s come back to supercar design with the sub-1000kg T.50 “to prove a point” should.

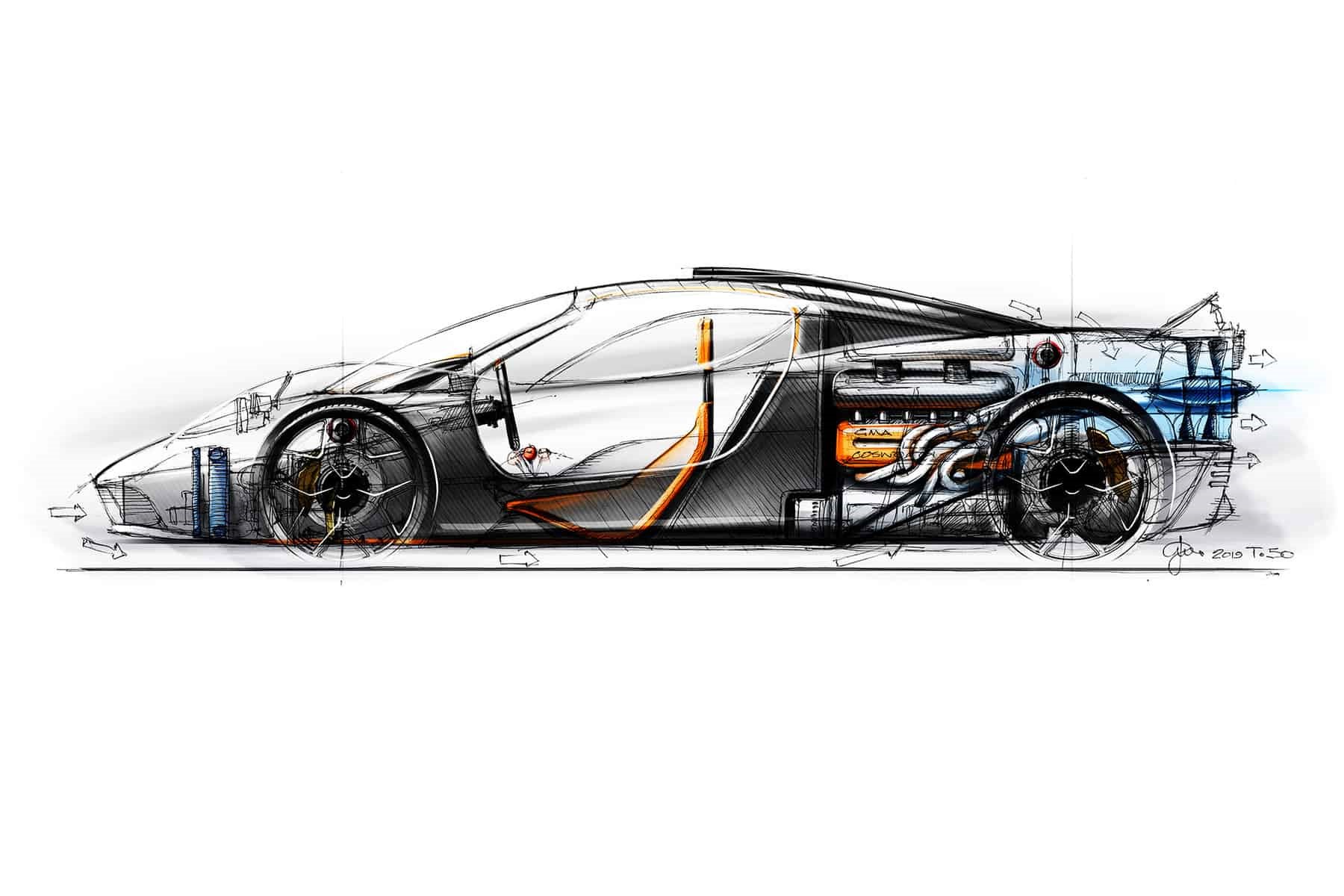

The Gordon Murray Automotive T.50. Another game-changer from the professor? By Wouter Melissen.

In early August, Professor Gordon Murray revealed his fiftieth car design to the world. Appropriately dubbed the Gordon Murray Automotive T.50, it embodies all the lessons he learned creating road and racing cars during the last fifty years.

As a road-legal supercar, it can naturally be considered the spiritual replacement to the legendary McLaren F1. The T.50, however, also incorporates some features found on the racing cars the South African has designed. Perhaps the most visible of these is the big fan on the tail of the car, which harkens back to the Brabham BT46B Formula 1 car of 1978.

Introduced at the Swedish Grand Prix, the BT46B actually was the third version of the BT46 developed by Brabham. These were the result of Murray struggling to compensate for the bulk of the flat-12 Alfa Romeo engine the Bernie Ecclestone-owned team had to committed to from the start of the 1976 season. The 12-cylinder unit was similar in design to the successful Ferrari engines, but undoubtedly more important to Ecclestone was that he had secured the supply free of charge. The choice of engine also pleased the team’s Italian backers Martini and later Parmalat. While it proved very powerful, it was also less reliable, heavier and less fuel-efficient than the Ford Cosworth DFV used by most rivals.

With the original BT46, Murray tried to compensate for the excessive weight of the Alfa Romeo engine. Instead of using conventional water and oil radiators, the body of the BT46 was covered with flat panel heat exchangers. An added benefit of this solution was increased aerodynamic efficiency, as there no longer was a need to disturb the airflow with radiators. As it turned out, the surface area available for the heat exchangers was insufficient to cool the car properly. During testing the car suffered from massive overheating issues. The concept was abandoned and the BT46 made a belated debut in round three of the World Championship with conventional radiators mounted in the nose.

The sole surviving BT46B sucking up the dust at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

John Watson finished third at the BT46’s debut at Murray’s home Grand Prix. The winner of the race was Ronnie Peterson, who drove the revolutionary Lotus 79 Cosworth. It was a carefully guarded secret at the time but the Type 79 and the Type 78 before it used wing-shaped tunnels under the car to generate “ground effect” aerodynamics. By raising the floor in the tunnels and giving it the shape of the top surface of an airplane’s wing, a negative pressure was created. The car was effectively sucked to the ground without the need for drag-inducing wings. Lotus had introduced ground effect in 1977 but it really started to make a difference when Lexan skirts were added in 1978 to better seal off the area underneath the car.

Murray was one of the first to fully understand what Lotus was doing, but he could not respond instantly due to the flat layout of the Alfa Romeo engine. Originally, this had been one of the great attributes of the engine, as it resulted in a lower center of gravity, but now it prevented the ground effect tunnels to run on either side of the engine. This prompted Murray to look at a different approach to create a low-pressure area underneath the car. He needed to look no further than the 1970 Chaparral 2J Can-Am car. This used a snowmobile-engine driven fan to suck the air from underneath the car. The very fast 2J was eventually outlawed, as it fell victim to the ban on moveable aerodynamic devices.

With no conventional radiators to disturb the airflow, the BT46B was a very clean design.

Also still looking for a different approach for the BT46 cooling architecture, Murray, along with consultant engineer David Cox, came to a solution that solved both problems. A system was devised that incorporated a tail-mounted fan that would suck air from underneath the car just as on the Chaparral. Crucially, the fan drew air through the radiators that were now mounted on top of the engine. The fact that the fan was primarily used for cooling is what made it legal. Gordon Murray explained this in his book, “One Formula, 50 Years of Design”.

“I read the regulations again and Article 3.7 on aerodynamic devices said, ‘anything that’s primary function is to have an aerodynamic influence on the car must always remain stationary and be fixed relative to the sprung mass of the car.’ I spoke to a lawyer friend and said, ‘what does primary function mean?’ And he said, ‘well, how many functions are there?’ I said, ‘two.’ So he said, ‘the primary function is the one that has more than half the influence.’”

The water and oil radiators were mounted on top of the flat-12 Alfa Romeo engine.

The main weakness of the Chaparral 2J was the reliability of the auxiliary engine. As soon as it failed – and it did so regularly – the car was effectively undriveable. In the Brabham design, the fan was simply driven off the engine, which meant that the higher the engine revved, the greater suction effect. The car was also fitted with skirts to seal off the area underneath the car. This proved to be the most delicate part of the design as using skirts that were too long made these prone to damage, while running skirts that were too short saw them simply sucked to the underside of the car. Regardless of the length, damage incurred during driving remained a very dangerous problem. The sudden loss of low pressure had dramatic effects on the cornering speeds.

As he describes in his book, Murray found a creative solution: “so, David [Cox] went down to a scrapyard and got an altimeter out of an old airplane. We had a pitot tube on the front, which you can see in all the photographs, which measured the static pressure. All an altimeter does to read the altitude is measure static pressure and local pressure and it uses the pressure differential to calculate the height. So that’s what we did. We had this altimeter tie-wrapped in the cockpit, right in front of the driver, with a green zone and a red zone. We said, ‘forget the numbers; that’s nothing to do with it. If you’re coming into a corner, the needle has to be in the green zone. If it’s in the red zone, you’ve lost suction. Slow down.'”

A graphic impression of the airflow over, underneath and through the T.50.

Even though it was the third version of the BT46, the Brabham “fan car” was dubbed the BT46B. It was ready in time for the Swedish Grand Prix, the eighth round of the World Championship. Not surprisingly, the new Brabham attracted a lot of attention. With the ban on moveable aerodynamic devices, it was subject of a lot of debate. Murray had explained to the governing body exactly what the primary function of the fan was and during the weekend a scrutineer duly arrived to measure the airflow. He found that Murray was absolutely correct and that, indeed, around 55 percent of the airflow ran through the radiator.

The 45 percent that remained was more than enough to give the BT46B a considerable edge over the rivals. In an attempt not to incense the competition any further, Ecclestone instructed drivers Niki Lauda and John Watson to qualify their BT46Bs with full tanks. Nevertheless, they were third and second respectively. Watson retired from the race but Niki Lauda claimed a convincing debut victory with the Brabham fan car. Its benefits were illustrated best late in the race when an oil spill had made the track surface slippery. Where others had to slow down, Lauda’s Brabham was seemingly unaffected.

The rear-end of the T.50 is dominated by the large fan.

Even though the BT46B had been declared legal, ahead of the 1979 season it was announced that the loophole in the regulations that had allowed it would be closed. Ecclestone also already had his eye on the bigger picture and decided not to race the fan car again. At the time it was widely reported that the BT46B had been banned but that was not the case. Brabham did not win a race again with the Alfa Romeo engine, but for Ecclestone parking the dominant machines turned out to be instrumental for him to become the most powerful man in the sport. Before that happened, Brabham would go on to win two more World Championships with Murray-designed machines that were powered by the Cosworth DFV V8 and BMW turbo “four” respectively.

The clean lines of the T.50 are clearly inspired by the McLaren F1.

For the T.50, Murray did not have to look at any rule book and, as a result, the tail-mounted fan’s primary function is indeed to create a low-pressure area on the car. Interestingly, he had already used a similar system in the McLaren F1 but, with the fans hidden away in the wheel well, it was not nearly as obvious. On the T.50, the fan is part of a fully active underbody aerodynamics package. Murray explains: “through the application of two automatic and four driver-selected aero modes, the T.50 is capable of increasing downforce by 50 percent; reducing drag by 12.5 percent; adding around 50PS to the car’s output in combination with ram-air induction; and cutting braking distance by 10 m from 150 mph.”

The fan on the T.50 helps to manipulate the airflow around the car and improve the performance.

Together with the extraordinary low weight of 986 kilograms, the high-revving Cosworth V12 engine, manual six-speed gearbox and the three-seater layout, the T.50 promises to be another game-changer like so many of Murray’s designs. Like the BT46B, it looks set to be leaps and bounds ahead of its rivals. This time, however, Murray has not been forced to conform to any sporting regulation or take into account the feelings of any of his rivals.

Gordon Murray T50 is V12-powered McLaren F1 successor. By Steve Cropley. 4 August 2020.

“Purest, lightest supercar ever built” has a 650bhp atmospheric V12 and a three-seat carbonfibre cabin.

Gordon Murray’s new V12-engined T50 supercar, the “logical successor” to his seminal McLaren F1 of 1992, has been unveiled at the Surrey factory where manufacturing will start late next year. Deliveries are due to begin early in 2022.

The new car, which Murray calls “the purest, lightest, most driver-focused supercar ever built”, is an ultra-light, mid-engined, all-carbonfibre three-seater, dubbed the T50 because it’s Murray’s 50th car design in a career spanning more than half a century.

It uses a refined version of the ground-effect ‘fan car’ technology its designer first introduced to grand prix racing with the Brabham BT46B for the 1978 Formula 1 season.

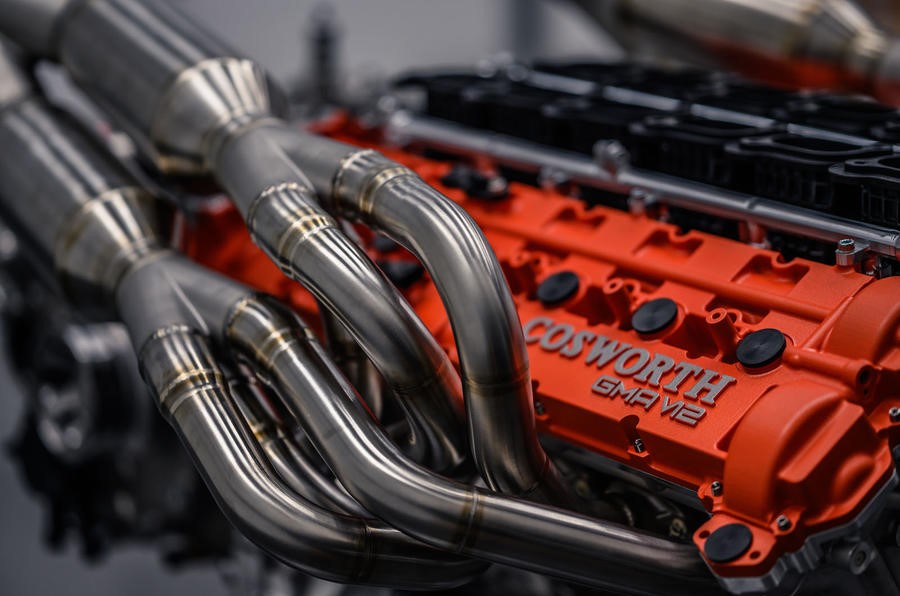

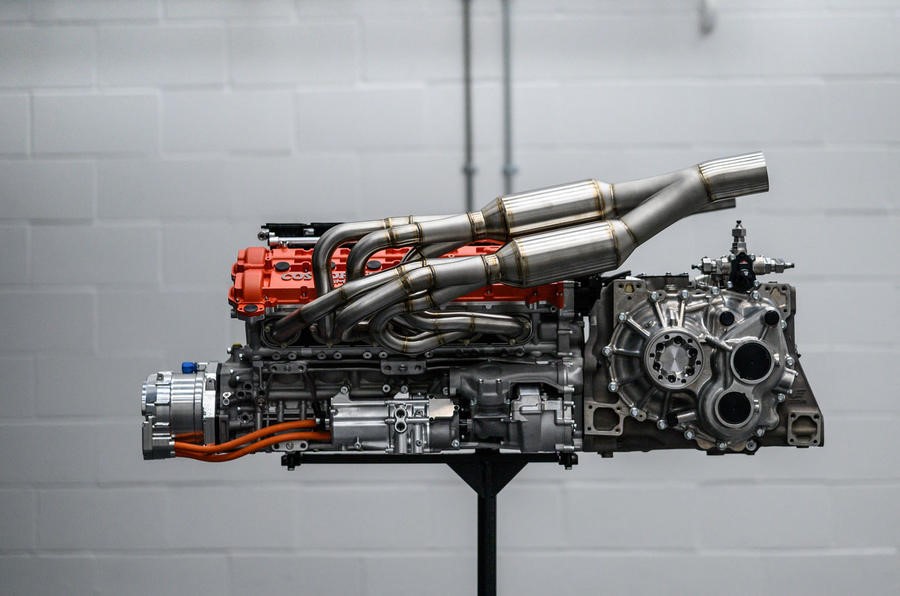

Powered by a new 650bhp naturally aspirated 4.0-litre Cosworth V12 with a 12,100rpm redline, the T50 will be built entirely by Gordon Murray Automotive, the bespoke company Murray launched to stand beside his existing design business when he revealed his plans for this car back in 2017.

Just 100 road-going T50s will be built, each at a cost of £2.36 million before local taxes – so about £2.8m in the UK. Most have already been snapped up by global car connoisseurs, notably in the US and Japan, each of whom has paid a £600,000 deposit for the privilege. A further £750,000 is due when their car is specified in detail, with the balance settled upon delivery.

The first T50 is scheduled to reach its owner in January 2022 and the entire batch will be completed within the same year. After road car production ends, there will be a run of 25 hardcore, track-only editions. Murray says he would love to see the car race but is reluctant to commit to a programme at present, because he wants to concentrate on the road-going version and because sports car and GT race regulations beyond 2022 are still far from certain.

Like its revered McLaren predecessor, the rear-wheel drive T50 places its driver centrally in the cabin, as in a jet fighter.

Its footprint is similar to that of the Mini Countryman (it’s smaller than the Porsche 911 and lighter than the Alpine 110) and it forgoes door mirrors for cameras to avoid adding to its 1.85m body width, so it should feel highly manoeuvrable in tight going.

The T50 was styled entirely in-house, with Murray himself the leader of the tiny design team. There are obvious references in its shape to the F1 — such as the compact size, the arrowhead front panel, the roof-mounted air scoop, the dihedral doors and the use of ‘ticket windows’ in the side glass — but strenuous efforts were made to make it look even more petite than its forebear.

There’s a major contrast between the graceful front end of the T50 and the extreme functionality of its rear end, which features large exhausts, business-like mesh for engine bay cooling, a giant underbody diffuser and a 400mm fan. The fan is driven by a 48V electrical system and its job is to develop downforce by rapidly accelerating the flow of air under the car. Murray says this “rewrites the rule book for road car aerodynamics”.

The fan, the diffuser and a pair of dynamic aerofoils on the body’s upper trailing edge combine to develop far more downforce than any natural system could and therefore develop levels of cornering grip hitherto unknown in supercars. There are six aerodynamic modes. Two of them, Auto and Braking, work automatically, depending on the car’s speed and the driver’s input. The others — High Downforce, Vmax, Streamline and Test — are selectable from the cockpit.

High Downforce is self-explanatory, while Streamline and Vmax are similar in that the former configures the aerodynamics with a “virtual long tail” by running the fan at full speed and retracting the active flaps on the top and bottom surfaces. Vmax runs the V12’s crank-mounted 30bhp integrated starter-generator flat out to contribute extra power in three-minute bursts. At speeds of above 150mph, the roof-mounted induction air scoop boosts maximum engine output to around 700bhp.

Impressive interior space is another theme of the T50. Its cabin is even roomier than that of the F1 (not to mention all modern rivals) and access to the centre seat is easier, because the floor is now flat.

The analogue switchgear and instrumentation – very much designed in jet fighter style – are relatively simple but crafted to Swiss watch quality.

The two side-mounted luggage compartments are as roomy as those of the F1 but can now also be top-loaded. Murray may be selling a £2m-plus collector’s car, but he’s determined that it will be usable day to day.

“The T50 is entirely road-focused,” he said, “which is why it sets new standards for packaging and luggage space. It betters the F1 in every way: ingress and egress, luggage capacity, serviceability, maintenance and suspension set-up. Also, driver-selectable engine maps ensure a driving mode to suit every situation.”

Murray said the supercar his team benchmarked against most often during the T50’s development was actually the 28-year-old F1. That was because no one has since attempted to build a car with the same credentials: an ultra-light, centre-seat supercar with a turbo-free V12 and a manual gearbox.

The T50 is said to weigh just 986kg at the kerb – about two-thirds of the weight of what Murray insists on calling “an average supercar”.

Keeping control of weight isn’t just about using exotic materials, he said; it’s a state of mind. The design team held weekly meetings about it. The T50’s carbonfibre tub chassis weighs less than 150kg with all panels. Every individual nut, bolt, bracket and fastener — about 900 of them — was individually assessed for weight-saving.

The transversely mounted six-speed manual gearbox, supplied by Xtrac and designed with a new thin-wall casting technique, is 10kg lighter than the already-featherweight ’box used by the F1.

The Cosworth V12, meanwhile, saves another 60kg over the F1’s BMW-derived engine and much more compared with that of a Ferrari.

Even the carbonfibre driver’s seat weighs only 7kg and it’s 3kg for each passenger seat.

Why take such trouble? “Because a heavy car can never deliver the benefits of a light one”, said Murray. The lightness and the 650bhp potential of the new V12 give the T50 a power-to-weight ratio that most conventional supercars could only match with a power output of close to 950bhp. Originally claimed to be 3890cc, the engine is now confirmed to be 3994cc in capacity.

Despite the figures, Murray won’t be aiming to break Nürburgring lap records or set blistering acceleration times. “I have absolutely no interest in that,” he said. “Our focus is on delivering the most rewarding driving experience of any supercar ever built. But rest assured, we will be quick.”