Today's Formula 1 has run aground on polically correct and the too high costs of technology but if it has been the beautiful game we have loved so far, we owe it to men like him. For many years he accompanies us race after race with his technical explanations, a life on the circuits. And a lot of unknown anecdotes that make us appreciate F1 more than before. He is so passionate. It’s difficult to imagine a GP without him.

Giorgio also drove racing cars and owned a Ferrari.

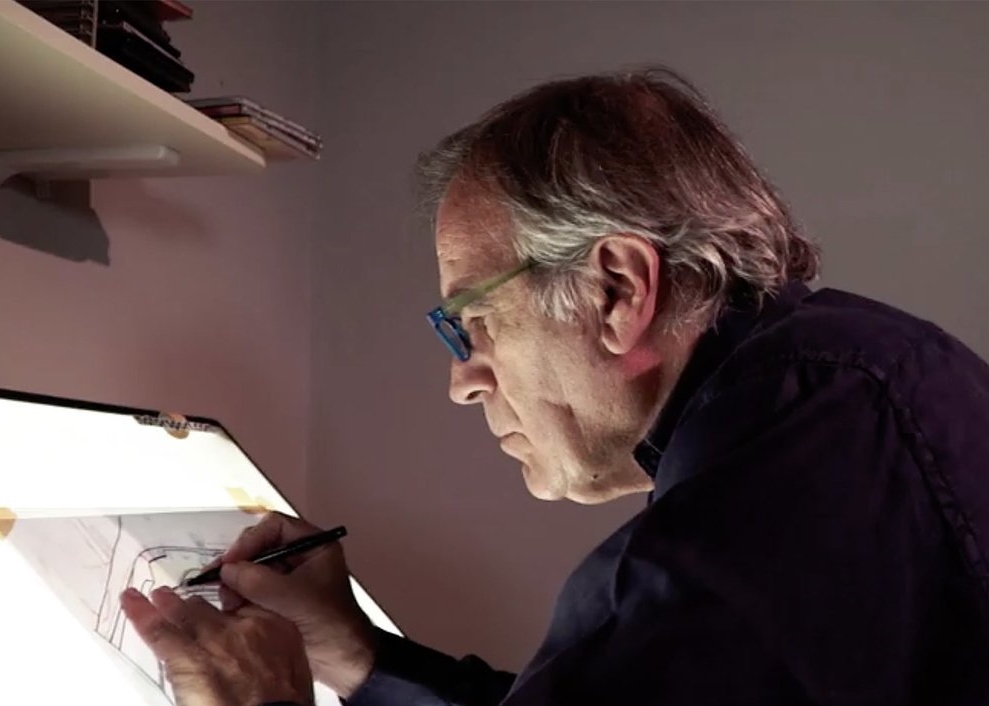

Giorgio Piola (s. 1 November 1948), the master artist of Formula 1 for over 50 years, is an Italian journalist known for his activity as an expert Formula 1 envoy.

Famous for his drawings of the technical details of the single-seaters, he boasts the largest number of Formula 1 Grand Prix followed live (811, at the 2019 Chinese GP).

He began his career in 1970 on the pages of Autosprint and then moved in 1975 first to Corriere della Sera and then to Gazzetta dello Sport where he continued to work until 2015.

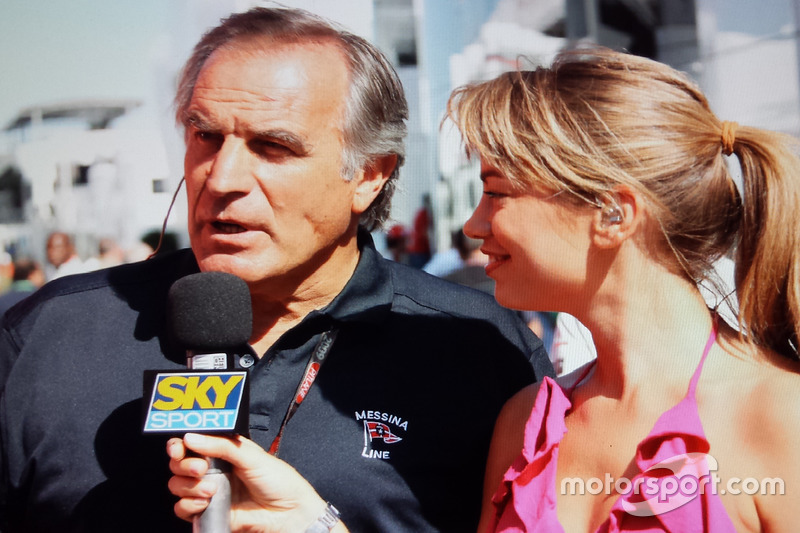

Since 1990 he has also been active as a television commentator, with the task of analyzing and presenting the aerodynamic structure and mechanical functioning of sophisticated Formula 1 cars to engine enthusiasts.

Until the end of the 90s, he collaborated with the editorial staff of the sports program dedicated to the Grand Prix engines broadcast on Italia 1, a network that in the period 1991-1996 (this last year under the exclusive regime) held the rights for free-to-air transmission and live on the Italian national territory of Formula 1 sporting events and which the following year were acquired by RAI under a monopoly regime. He later joined the RAI sports editorial team.

In the 2008 season he was part of the team of technical commentators for the satellite station Sky Italia and since 2010, after Sky's failure to renew his Formula 1 rights, he joined Mediaset. Since 2011 he collaborates with CSR and comments on the GPs. In 2013 he returned to Rai until 2017. He returned to collaborate once with RSI on the occasion of the 2018 Belgian Grand Prix and subsequently for the Italian Grand Prix.

Since 1994 he publishes annually for the Nada publishing house, an annal on Formula 1 entitled Technical Analysis which is translated and published in three languages. For years he has been technical consultant for many national and international magazines including Autosport, Gazzetta and Autosprint. Since 2016 he has collaborated exclusively with the international Motorsport.com network.

On the occasion of the 2019 Chinese Grand Prix, race number 1000 in the history of Formula 1, he is honored by Chase Carey (CEO of Liberty Media) with a celebratory coin being the character of the paddock with the highest number of grand prizes in his assets (811, debut in Monaco 1969).

Giorgio Piola: “at first “mi turbo”, then I get married”. Published on 14 June 2014.

This year Giorgio Piola, the F1 technical journalist, celebrated his forty-fifth Monaco Grand Prix. His long career began in 1969, right on the prestigious circuit of the Principality. Driven by a passion without limits, he “discovers”, designs and explains every detail of the grand prix single-seaters.

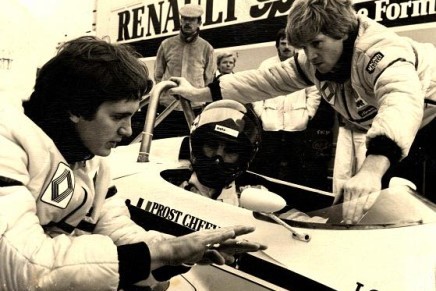

In 1982, Giorgio, originally from Santa Margherita Ligure, was already a familiar face in the racing world. At the end of the F1 championship, Renault intended to let some journalists test its single-seater, the RE30B, which had a 1500 cc. 6-cylinder engine supercharged by two turbines. This car had allowed the French manufacturer to obtain the 3rd place finish, with four wins but many retirements. Antonio Ghini, head of Renault-Italy, called Giorgio Piola asking him if he was willing to test the car at Paul Ricard on Friday 26 November. Piola had been waiting for such an opportunity for a lifetime, but there was a "small problem" to be solved: the following day, Saturday 27, would be his wedding day! Now, how can you give up the dream of driving a F1 and check for yourself those details that interest you so much? He made Ghini promise to be able to carry out the test in the morning, in order to return to Italy as soon as possible.

Then, with all the turns of words of the case, he convinced his future bride that... he would go "slow". Finally, on Thursday at 12 he left Italy, along with the trepidation that any fan would have in such a situation. When he reaches his destination, it rains heavily. There are also other journalists and drivers Eddie Cheever and Alain Prost. The test would take place on the airport runway. The next morning, there is a light, thin rain. The track is wet and full of puddles, so the "rain" tires are mounted. Eddie Cheveer gives him advice. Piola's first problems come when he tries to get into the cockpit: to get in they have to remove the seat, so he is forced to sit directly on the sheet metal. Also, his feet, size 45, have a tendency to get stuck between the pedals. The gear lever is very small and reaches a few centimeters from his hand. While the belts are tightened, the emotion rises. They start the car, he engages first gear, releases the clutch and… turns off the engine.

Cheveer had recommended that he starts moving without suddenly jumping the clutch, stepping on the gas and continuing to “sfrizionare” for a few meters, otherwise the turbo, at low revs, would have turned off. At the second attempt Giorgio remembers it, indeed Cheveer reminds him well, yelling at him. He starts again, this time well. On the track, apart from his stature problems, the Renault seems comfortable and safe to him. He matches the second, third, fourth gear, arrives at the hairpin at the end of the straight, then tackles the back straight and matches the gears again, third fourth. The power of the turbo is felt and the Renault from docile suddenly turns into a bad beast. He begins to gain some confidence. He drives a version without side skirts, already in line with the 1983 regulation. When he accelerates out of the hairpin the wheels spin.

Concentration is at its best, directed at controlling the car. He doesn't feel like taking his eyes off the asphalt even to take a look at the rev counter. He realizes that he cannot afford any distractions, just a thought to imagine the level of the drivers who drive this type of cars in the race, touching with nonchalance curbs, walls and the other cars at full speed, while realizing how difficult it is, for anyone else, to keep the car straight on the straight. The car is responsive, as it should be and he instinctively tightens strongly the steering wheel. In all, he completed five laps, for the unforgettable satisfaction of having driven a 600 horsepower Formula 1. Eddie Cheveer liquidated him like this: “ten for speed, six and a half for control, good dose of madness or courage, whichever you prefer. But I think it is much better if you do technical drawings and not the driver”. The next morning, Giorgio was already in Italy. To "relax" he did some obstacle courses with his two horses. With the wedding in the afternoon, he completed the busiest twenty-four hours of his life.

FP | Enzo Frangione@enzofrangi1.

Giorgio Piola, the artist of Formula 1. 03/06/2015.

The Italian Giorgio Piola is a unique journalist in Formula 1 and also one of the most veteran. He specialized in the design of cars, looking for a didactic approach for the general public. His drawings have appeared in the media all over the world and he has the recognition and respect of the main technicians and designers who have passed through the 'paddock'.

The Big Interview: Giorgio Piola on his F1 career. By Олег Карпов. Dec 31, 2016.

During more than 40 years of pacing the Formula 1 pitlane and garages, Giorgio Piola has become the sport's most famous technical journalist. Here he tells the story of his career, the friends he made and the scoops he uncovered.

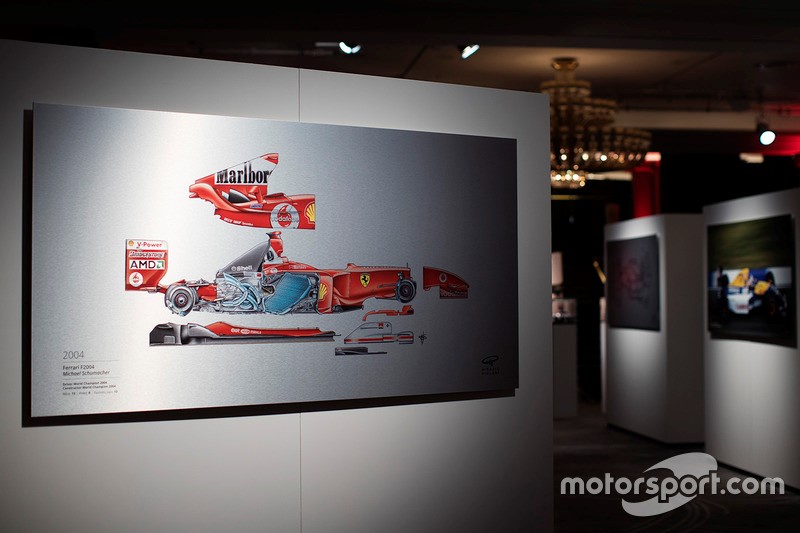

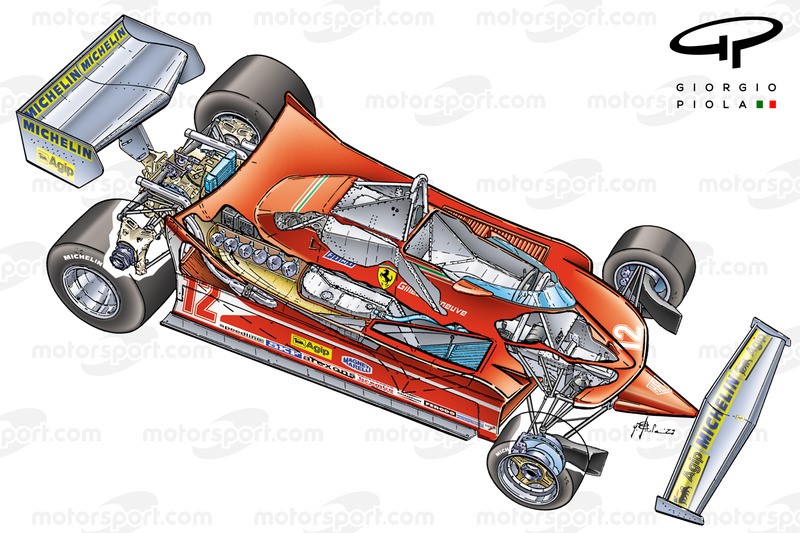

A Giorgio Piola technical drawing of Michael Schumacher's 2004 Ferrari. Photo by LAT Images.

For you, Giorgio, which became apparent first – your love for racing or your love for engineering?

“Well, I was always good at drawing. My family, we were four - three brothers and one sister - and everybody was quite good at drawing. Early on, that was my passion, drawing anything.

Around the age of 12, I started to concentrate on cars. I was buying issues of Auto Italiana, which was a very good magazine and there was the one Italian designer and journalist who I consider my teacher - Bruno Nestola. Then I was buying Road and Track and Car and Driver, who used a Swiss guy named Werner Buhrer.

I had a very strict education and I was very silent in school. I used to have always 10 out of 10 for behaviour - because I wasn't talking to anybody, but I was always doing drawings.

I'm not an engineer, so I don't understand more than others - but I believe one of my strengths is being able to see more than other people in terms of details. And that's because I trained myself – not thinking about doing it as a profession, but just by coincidence – to look at the teacher and still be able to draw.

Even in everyday life, when I'm walking down the street, I look at people and I see immediately, for example, if someone has a double arrow on their trousers. If the detail is a little bit different from normal, I notice it immediately.

It's the same with cars. I glance at a car and the differences stick out, as if there's a magnet. And this is something I believe I've built up with this training. Without knowing it, I was always training myself for my future profession.

I was always the best in drawings in my school. When the art teacher or the art history teacher was absent, I was called up to teach lessons for other students.”

How did you end up in journalism?

“It was thanks to one of my brothers, who I was very close to and who was also very good – maybe more clever than me. He had a better understanding of machinery and became an engineer.

I believe I had more talent, but he has more brain. There was always big competition between us, like "my drawings are better than yours" and so on. And one day I said: "listen, Marco, let's do it like this - we do two drawings, we send it to two magazines in Italy and we see what they answer."”

Giorgio Piola with Denny Hulme. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

How old were you?

“I was 19 and in university, because I wanted to become an engineer. In my family, everybody has a degree. Now I am the only one who doesn't.

We sent drawings and 20 days later, the letter came to me: "Mr. Piola, we like your drawing. We'd like to publish it". The letter was from Gianni Cancellieri, the chief editor of the magazine. And then he became the chief editor of the car section of La Gazzetta dello Sport.

He said then: "Mr. Piola, wouldn't you want to go to see the Monaco Grand Prix and do a technical report about Formula 1 for us?" It was 1969. And that's how I started. I won the bet with my brother.

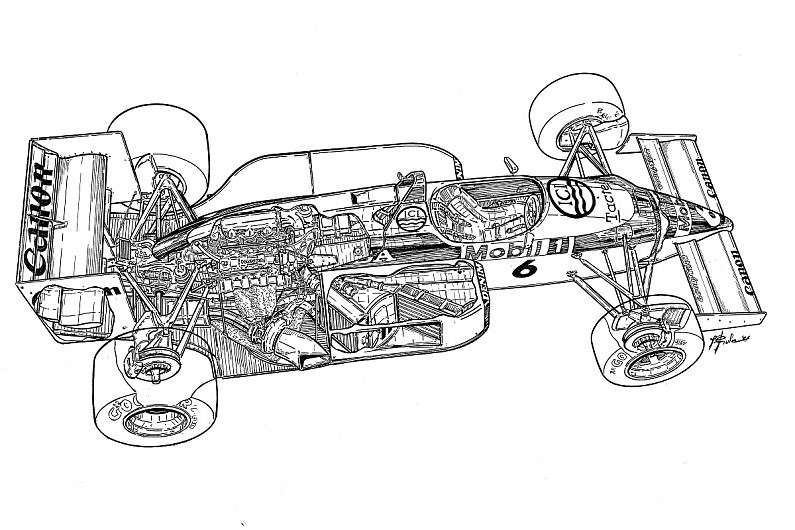

I was doing this as a joke but, in the end, it gave me my dream profession. As an industry, it didn't really exist as that point. There were technical drawings of saloon cars, jeeps, trucks – but I myself invented this profession of doing drawings of racing cars directly from race tracks.

I have to say thank God my mother was well off, as she helped me in the beginning, because nobody was paying me. But already in 1972 I had Gazzetta dello Sport, Autosprint in Italy, Autosport in England, Sport Auto in France, Rally Racing in Germany and Corsa in Argentina.

It helped that I could speak English and French quite well, so it was easy to find clients. And it was also good that there was no one else doing it and everybody wanted to have it. So I was very happy. But of course, by going to races I completely missed university. I did only three exams.”

Giorgio Piola with Alain Prost, McLaren MP4/2 car at 1984 Brazilian GP. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

So you called time on your education?

“Yes, I left university six months after I started because Formula 1 was so wonderful. It was very glamorous and we met actors and actresses - Candice Bergen, Paul Newman, a lot of people. There were wonderful parties, so it was really fascinating. But there was a part of it that was terrible.

Myself, I'm a very pessimistic person. When I was younger, my favorite film director was Ingmar Bergman, who always had big thoughts of death. The horrible part of F1 in those days was that every single year we had one or two drivers killed.

On the other hand it was fantastic world. It was completely open access to everything. I have a picture of myself inside the garage of McLaren, near the world championship-winning car, with no mechanics or anyone else around. I was taking sketches beside it and nobody was saying anything”.

You must have had an interesting relationship with technical directors?

“Right away I got on well with engineers. I believe that there are a lot of engineers that have big respect for me - and I respect them. There are thousands of wonderful anecdotes I have with Patrick Head, Gordon Murray, John Barnard, Harvey Postlethwaite, Tony Southgate, Maurice Philippe, Ralph Bellamy, Gordon Coppuck. It was always a very good relationship.

Giorgio Piola and Patrick Head.

For example, with Patrick we used to have a game. When I came to a grand prix, I was asking "Patrick, what is new in the car?" And he would say: "This time we have six new things." Later I'd go up and say "Patrick, but I saw only four" and I would hear him reply: "It doesn't matter, you have to find the other two by yourself, sire, I won't help you…."

What I also like in my work is that it's very psychological. Very often I found a new solution only from reading the behaviour of people. I'm quite an isolated person, especially when I was younger I wasn't talking to anybody, but I was always studying people.

The best example was one year in the 70's, I think it was the year Stewart won the championship, maybe. Anyway, I have the drawing. We were in Paul Ricard and it was the first time the cameraman had come to film practice. And there were two Tyrrell cars, the new one and an old one.

At one point, the cameraman wanted to film the car from the back and one mechanic went in front of him. And I asked myself: "Jeez, that's strange. There is a new car and nobody is covering it. This is an old one and they do it. Why?"

So I paid attention to it and it seemed they were testing variable camber angle. Instead of it being fixed, there was an oval that could be changed mechanically. That was something completely new and that was the reason why they were covering it. Afterwards I made the drawing, I went to that chief mechanic, that I knew very well and I said: "thank you very much, because I would never have realised this. You helped me."

Another time, more recently, when there was an innovation from Mercedes, I had information from Michael Schmidt (Auto Motor und Sport) that Mercedes was testing a new front wing, but he didn't know what exactly what they were doing. The mechanics were changing wings on both cars and when they were changing only one of them, they were making sure no one saw the bottom of the wing. I said to myself that there must be something under the wing.

So I was going up and down the pit lane. They never did make a mistake and lift it too high, but at one moment a mechanic did slide with his fingers under the wing. I assumed that was where the slot was - and I made the drawing of the normal wing, but with a slot. Then during the next race Schumacher spun and they lifted the car – and the holes were exactly in the right place.

It's the same sort of thing when they covered the steering wheel of Lewis Hamilton. I thought there is something different - and I only realised it because they were covering it and never left it anywhere lying just like that.”

Giorgio Piola, The Living Legend. Photo by XPB Images.

What are some of the things you are most proud of having uncovered?

“Back then it was very easy to do, to anticipate something new. For example, when there was the Tyrrell car with six wheels, I did a simple drawing of a car with four small wheels in the front to show the principle. It was not important to find the shape.

Now it's more difficult, because there are so many restrictions that you can't have something completely different. So you have to do the shape exactly.

I did the six-wheeled car before everybody else and also the Brabham with the flat engine. At the launch of that car, Gordon Murray said: "that should have been a complete secret, but thanks to that bastard sitting on the second row, everybody knows we have the engine mounted like this." That was funny!”

Was it ever the case that you knew something but couldn't publish it?

“We were in Monza the year before the Lotus 78, the first wing car. And there was an English journalist, who went to Colin Chapman and said: "Piola has done the drawing of your new car."

I had a very good relationship with Chapman, so he called me: "Giorgio, is that true?". I replied: "Yes, I've done the drawing, with wing and sidepods and the skirt."

He said: "if you do publish this... We have to do the launch with John Player Special and it will be a big disaster. If you do this. I'm afraid our relationship won't be as good". I told him: "listen, they will pay me this much for this drawing and I'm destroying my relationship with you now?" So I took my drawing and destroyed it in front of him.

As a result, he invited me to the assembling of the car the day before the launch. I was without a camera, but I was able to see everything. These kinds of things, that I was invited to see cars before the launch, happened quite often.

There was one time a very funny situation with Gary Anderson, who is a good friend of mine. He was the chief mechanic of Emerson Fittipaldi and then became Jordan's technical director. He is a wonderful person. He invited me to the assembling of the Jordan, and I brought my camera.

Giorgio Piola with Maurizio Arrivabene, Ferrari Team Principal. Photo by Nikolaz Godet.

The mechanics were assembling the car, but every half an hour they were stopping to go to eat or to have a break and I was waiting for those moments to do a shot. So I could have pictures of the chassis, suspension and everything. But every time the mechanics left the car, there was another guy coming up and standing beside the car, even sitting in it, so I could not do the picture. He did it once, then twice, then a third time.

Finally, I shouted at him: "hey you! What the hell are you doing? Every time you're in front of the car when I need to do the picture!"

Gary arrived immediately: "Giorgio! Giorgio! This is Rubens Barrichello. My driver". So I said sorry!

He just wanted to see his car and all the assembling, it was normal. But he was coming from another category, so I did not know him and I scared him a bit.

One big problem was that sometimes teams were asking me to give them pictures to help them out. But I never ever did this.

In the 70's and 80's, there were no electronic cameras, of course, so we had to do films and send pictures to publications and so on. One time, after I sent a picture to Autosprint for a technical feature, I was talking to Michel Tetu, an engineer from Renault, and we were discussing tech stuff. He said: "you see Giorgio, here is something." And he showed me a picture of mine.

I looked at the back of the picture and it said "Studio Piola". That meant that the journalist from Autosprint, who was a friend of Michel, gave him the picture. So I said to the magazine: "from now on I'll never send you any. I'll do the drawings and that's it, I'll never send you pictures".

And that's how you have to be, because otherwise you're done. I've been here for 47 years, I've done 767 grands prix. And if I do something like this, I'm dead.

You have to be principled. I come to the tracks very early and in the past I used to also come late after dinner, because it was open, even at 11 in the evening. I was coming to the track to see if there was anything interesting.

I remember, one time, Benetton mechanics left their car unattended - and there was something completely new in the T-tray area. It was when the sport first moved to having a step bottom, a completely new idea from Rory Byrne. And in the morning the wind took away the cover, because it was plastic. So I saw that Benetton without a cover, I made immediately an easy drawing, in 10 minutes.

Guys from Benetton, they would later send their PR to offer me money not to publish the picture. But I did. And this happens very often, they offer me money not to publish something or to give them some pictures of their rivals, but this is something you cannot do. Not even with a friend.

This is another thing that people sometimes don't understand. My work is maybe not as important as before, because with an electronic camera you can do things much better yourself, but before it was very important. If I work and have exclusivity with a magazine, if another journalist, even if he is a friend of mine, is asking about a technical scoop, I can't give him information. Because I have to respect money people pay me. Otherwise they won't pay.

Sometimes people call me arrogant and unfriendly, but it's not like that. It's just that I have to do my work and I can't give out the information. I can be your friend in the evening when we go to dinner, but if they ask me "Giorgio, what's the new secret in the Ferrari", I have to say either "I don't know" or even "I know, but I'm not telling". Because it's respecting the money people pay me.”

Giorgio Piola with Jo Ramírez, McLaren. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Your work now is different to what it was before?

“I don't like my new work as much as what I did before. In the past I would do those big drawings that took 40 days and it was incredible - and I do believe there were only three people in the world who were able to do this - with Tony Matthews for sure the best.

These days, unfortunately, you have to do everything in a hurry. The quality is not as good as before. I have two assistants, so the drawings don't belong completely to me - but it's always me who does the actual drawing part, because then it's different to everybody else. I always do the trace and then I scan.

If you see the drawings of others, they do it with a computer system and the trace is very thin. I sometimes take stills from animation, but they don't pop out of the page. That the trace has some imperfections, it makes the drawing better.

I'm very open to listening to other people, even when they don't work in this industry. When you do something for many, many years, you focus and you lose grasp of other perspectives. My first wife, she was a fashion designer and one day she saw the lines on my drawings were all the same. She said "Giorgio, why don't you do like we do, let's say, all the lines on this side are thin and all the lines here are very big, so you see important things better?"

She went out, I made a photocopy of my drawing and retraced it wider. That was in 1982 and since then my drawings are like that. You see two dimensions, the drawing pops out of the page. And it shows how important it is to listen to people. I often ask my new wife for advice and I listen.

The other thing is that you can't be arrogant and you can't be too self-confident. I remember, in Australia one year, at the last race of the season, Alan Jenkins, who was the designer at Arrows and a good friend of mine, said to me: "Giorgio, you did not come to our garage".

I said: "Listen Alan, this is the last race of the season, your car is not competitive. What is the point coming to your garage?"

He said: "You made a mistake. Because we're testing suspension for next year. " See, you can never relax, because there's always something to look out for."

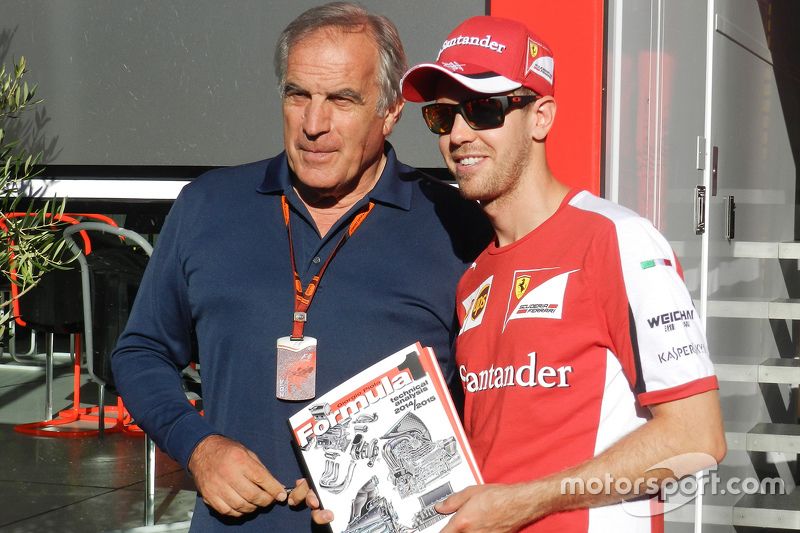

Giorgio Piola, Motorsport.com Formula 1 technical analyst, with Sebastian Vettel, Ferrari. Photo by Franco Nugnes.

What is the story of the Merzario A1 project?

“Oh, this story I don't like very much, because I hate to be doing something that I'm not able to do.

Alright, Arturo Merzario was a good friend and he asked me, because he had nothing, to do the design of a car for him. In those days, anybody could build a Formula 1 car, because the only thing needed was a certification from an engineer – no testing, just that certification – that the roll bar could resist three times the weight of the car.

Someone who sold ham could make a Formula 1 car! And it was easy. The radiator was the same for everybody, the gearbox was Hewland – everybody who used the Cosworth engine used this gearbox. So you had to do only the mounting of the suspension and the bodywork.

And unfortunately, due to the fact that he had the money and he was the boss, Arturo had a very funny idea that he wanted to have the nose very short. But it was totally wrong. Even a boy in secondary school knows that if you want to make a long object have the same amount of downforce, you need a small angle. If the object is very small, you need much more angle - because it's in relationship with the length and the moment of inertia.

So that car was completely wrong. It was a disaster. It only made it to the start in Argentina, but I already had nothing to do with it. Once he wanted to build new rear suspension and we had an engineer who made a calculation. But I think he made it very wrong and myself, with the chief mechanic, we tested it to see how flexible it is. It was too flexible for us, so we didn't mount that suspension on the car.

We went to South Africa and Merzario asked me: "why is there no rear suspension?" I told him there was a problem and so on, but he wanted to fix it. So during the night mechanics put it on the car and the first lap in the morning, at the first braking zone, the suspension collapsed.

I told him then: "Arturo, thank you very much, this is the end. Because I want to sleep well, knowing I did not kill anybody. I don't want to go to prison. This is not my job. I can't do it." But it was very useful anyway, because I learned about the system and how to do the welding. I learned a lot and I am thankful anyway to Arturo.

Another thing I learned a lot from was when Renzo Zorzi became the driver for Shadow. He wasn't able to speak English, nothing. So when he came to the pit lane, I sat beside him, he was talking to me and I was then translating to his engineer and back.

And I was allowed to stay for 15 minutes of the technical meeting, because that's how much of it the driver would do. The driver would say, "at that corner I had oversteer, coming out from there we are losing traction" and all that stuff.

Engineers were listening and then the driver was out - and they stayed to discuss. But still it was very useful, because I learned a lot.

Eventually they fired Zorzi and they replaced him with Riccardo Patrese. I made this telephone call to invite Patrese to Formula 1 and we became very good friends.”

Giorgio Piola and Renzo Zorzi, Shadow Racing Team. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Was the Merzario A1 the only car you had built?

“No. While the Merzario story I don't like, there is another thing I did that I am very proud of. In Italy in 1976, they introduced the Super Formula Ford championship with slick tyres and wings. There was this team from my hometown Genoa and the owner called me, because I was already well known as a journalist and a designer and he asked me to help them design the car.

This I did with pleasure. I have to say I made what was almost a copy of the Chevron Formula 3 with the wide nose. That year there was also the Osella car made specifically for that category, while the one we made was old Formula Ford modified to Super Ford. That meant we had a new engine cover, new bodywork and new wings, but the rest - suspension, chassis - was exactly the same.

Osella entered two official cars for Teo Fabi, a very good driver and Piero Necchi, who became also Formula 3 European champion, so again a very good driver. And in my team was Guido Pardini, who was also good. Our car won the championship in the end.

The only downside was that the guy didn't pay me, but honestly he said from the beginning: "Giorgio, I can't pay you. But if you want, you can race for free." I did eight races, I was always in the middle of the pack. I was not the slowest, I was always 10th or 12th out of 24 cars. But for sure I wasn't fast and I realized that it wasn't my thing. I know my limits.

Still, it was fun and I never hurt myself. I had only one accident - after the start at Mugello, I was third out of the first corner because I had jumped the start and nobody noticed it. So I was very excited about that – so excited that at the second corner I went onto the grass and my race was over. I didn't do any damage to the car, but I realised it wasn't for me.

I could do more racing, because I was a journalist and I could easily find sponsors, but I said no. Super Ford was a category for amateurs, there were 50-year-olds racing in that. There were some good drivers, three of four, but the rest were like me. I even found a sponsor to do F3 and I went to see the race, but after I saw the start, I said: "no, this is not possible for me."

At the end of the day, it was all good. Pardini won the championship with the car I designed. Of course, the car was very good, the team was very good, the driver was very good - and maybe the Osella wasn't very good, even if it was made specifically for that category. I was very proud of that season and I had fun racing - even if I was slow.”

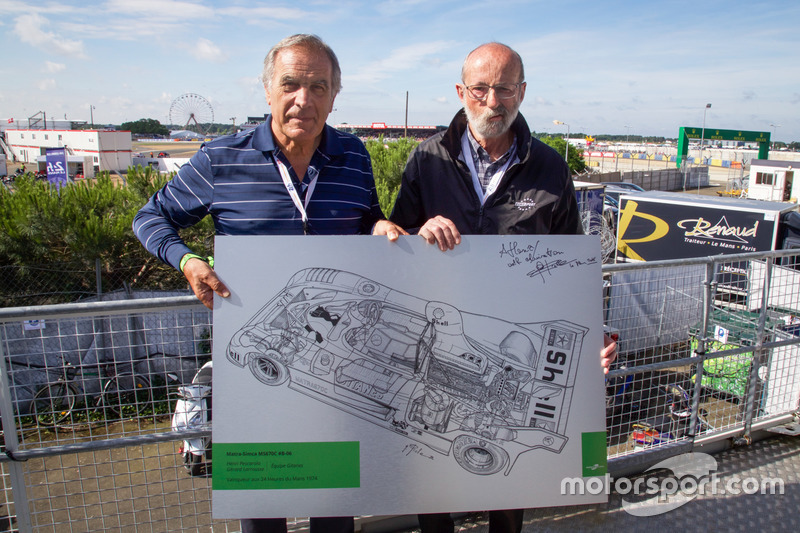

Motorsport.com technical illustrator Giorgio Piola offer his design of the 1974 Matra-Simca MS670C to Henri Pescarolo. Photo by Robert Lyon.

What is the best relationship you've had with a driver?

Giorgio Piola and Riccardo Patrese.

“Riccardo Patrese, Elio de Angelis and Nelson Piquet. There were a few of them.

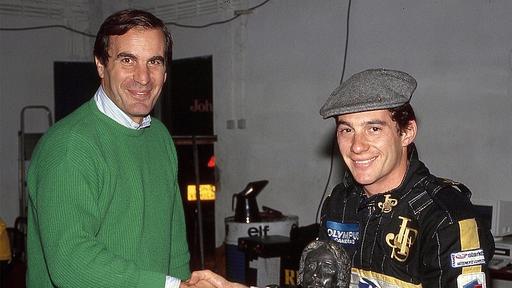

Giorgio Piola and Ayrton Senna.

Unfortunately and I'm really sorry about this, I had a very bad relationship with Ayrton Senna, because I insulted him once. He didn't want to do the press conference in Hungary and I made a mistake, calling him a liar. So the relationship was ruined.

I did get along with Gerhard Berger – and had a wonderful relationship with Alain Prost. And that was another reason why Senna didn't like me, because I was doing always interviews with Prost. I was also a journalist for Gazzetta dello Sport then, writing reports and so on. I got along well with Piquet, Lauda, Alan Jones, Carlos Reutemann, many drivers.

But again, I didn't want to become good friends with a driver because I was always afraid. When de Angelis died, to me he had been like a brother...

Jochen Rindt dying was horrible, too. I was very often in Lotus garage, first of all because I liked the Lotus cars and secondly because I was platonically in love with Nina Rindt. She was, for me, the most beautiful and charming lady. I've never seen any other woman like that in Formula 1.

So I was always there. And when Bernie Ecclestone came to the pits with the helmet of Jochen on Saturday at Monza, I just left the track. Unfortunately, I needed to write a report column for a magazine that weekend – I left the track and they fired me.

It was not very professional. But that part, the deaths, was always scary to me. I never wanted to be friends with drivers. Very often they would invite me to go to dinner or offer to give me a lift on the plane. I only accepted it once, from Piquet. But I didn't like these kinds of things because I was always scared.

When Roger Williamson died – well, I had never spoken to him and I barely knew him, so, while it affected me, it was different to when it's a driver you know. When I was working with Zorzi, I was around Tom Pryce a lot – and when he died, I was crying a lot. So just to protect myself, I decided I didn't want to be too involved in the relationships with drivers.

And then it just changed naturally. Back then we were all closer to each other, we were like this big family, always in the same hotels, restaurants, so there were a lot of stupid jokes, a lot of fun, girls and so on. Now I believe drivers want to be friends with journalists only when they can use them. And it's the other way around, too, journalists are friends with drivers because they always hope to get some news before everybody else.

But like this, it has nothing to do with friendship. It's only mutual interest and that I don't care for. Because I don't do anything for mutual interest.

So, my heroes are Patrick Head, number one, then Gordon Murray, Mauro Forghieri, John Barnard, Adrian Newey, Paddy Lowe. These people, I love them.”

LAT Images and Giorgio Piola logos. Photo by: LAT Images.

Is it true Paddy was an admirer of your work even before he made it to Formula 1?

“A lot of them told me they liked my work. Nikolas Tombazis is the same, Sergio Rinland. I'm old. And they were fascinated by my drawings.

Maybe they say it to make me feel good. But I know Paddy has a big respect for me. And Patrick Head as well – as I do for both of them. Patrick for me is untouchable. Adrian Newey is the same.

I admire these people again and again. When we talk, we talk about technical stuff, sure, but also they have a big culture.

Some drivers, they are good but they have a lot less in terms of personality. I don't want to say the name, but one driver I refused to eat with at the same table because he was eating like an animal. While when you talk with Patrick Head, he says "Giorgio, only 20 minutes" and yet we end up talking for one hour and a half. At least.

You see that they love to talk about technical stuff, but also about everything else. With Aldo Costa we talk about our dogs, we have golden retrievers and very often he shows me pictures. It's nice, you can be friends with this people. Not with the drivers, because it all goes through PR.

Before we used to do one-on-one interviews, long ones. For example, Prost, he used to organize a dinner at the first race of the season, in Brazil, with Jean-Louis Moncet, Nigel Roebuck, myself and Pino Allievi. We went to the dinner, put our recorders on the table and had an interview that was good for the whole season, because we talked about everything – set-up, rain, overtaking, how to be a good test driver. When something happened – for example, Prost wins in Imola - you could pick up from that interview exactly what you needed.

It was a similar thing with Berger. The only problem with him was that he liked to do interviews during dinner, but he never had money in his pocket. So you always had to pay for him. I once said: "listen Gerhard, I don't make as much money as you do." He laughed.

He was making these elaborate jokes and they could be harsh. Once we were in Spain and Benetton organized some corrida-like event and he and Alesi were playing toreros and I did the horse riding thing because it was a hobby of mine. I went to change, I saw he had my trousers and was going to cut them. So I convinced him to cut Jean's instead. He did it - and Alesi was very mad. Only last year did I tell Jean: "Gerhard wanted to cut mine, but I gave him yours."

Giorgio Piola with media. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

What was Alesi's response?

“To Berger? Oh, he could not do anything. If you respond to a Berger joke, he doubles up. Once he took Senna's briefcase and dropped it from the helicopter – with the passport, money and everything. All was lost. You don't joke with Gerhard.”

What was your relationship with Ferrari?

“Ferrari is very difficult. Because with Ferrari there is always pressure. When you say "McLaren tested a new wing, it didn't work, so they will race with the old one", nothing happens. But, in Italy, if you say "Ferrari tested new wing and it didn't work", it is immediately everywhere.

Let me give you an example. When Berger was testing with Ferrari for the first time in Rio, he needed knee pads. That was the first time, it never happened with any other driver. And they had to cut a little bit the frame of the dashboard - otherwise he couldn't enter the cockpit.

I made a drawing immediately for Gazzetta. It was easy. It was just a sketch. There was no other Italian journalist there because it was pre-season testing. So, one week before the grand prix, I wrote: "Berger is too tall to fit in the car, he needs knee protection and the team had to cut the frame of the dashboard."

The next day, all the other papers went with headlines like "Ferrari has a dangerous car", "The driver risks breaking his legs", all that stuff.

So my editor-in-chief got this phone call: "I'm Enzo Ferrari. Why the hell is Piola shoving his nose inside of my car and saying it's dangerous?"

My editor responded: "Piola does his job. We also have pictures and we could publish them. He made the drawing, because the explanation was better".

Enzo asked "is Piola in Rio?" I was. He said: " so can you explain to me why instead of looking at the arses of beautiful Brazilian girls, Piola is looking inside my car?

"Maybe Piola is gay? Tell him to look at the girls."

But that was light stuff compared to a pull rod suspension drawing I did before the official launch. Again, it was very simple - we had information and I made a simple drawing of the car from the front: "instead the car being like this, it will be like this."

Ferrari kicked up a fuss with the publisher of La Gazzetta. They wanted me fired. I didn't say anything – but there was no reason for this. Nobody could have copied the pull rod suspension anyway, because you would have to change the chassis. You can't do it. It's something that, until next season, nobody can copy.

So, yeah, with Ferrari it is never easy. With John Barnard it was easier, because I knew him from McLaren. We were not friends, but we had good relationship. And we got on even better when he went to Ferrari.

I wanted to do a book on his car. Every race in the evening I was going to his room and we had long interview. Then, unfortunately, my wife died and I didn't do the book, because for nearly one year I was totally out of the loop. She had battled cancer for six years and had a lot of surgery.

So I missed the timeframe to do the book, but the relationship was good. For example, two years ago an English journalist wanted an interview and I gave him John's number. When he said, "your number was given to me by Giorgio Piola", John replied "if Giorgio gave you my number, that means he trusts you, so of course we can do the interview". From the old generation of engineers, I think nobody dislikes me.”

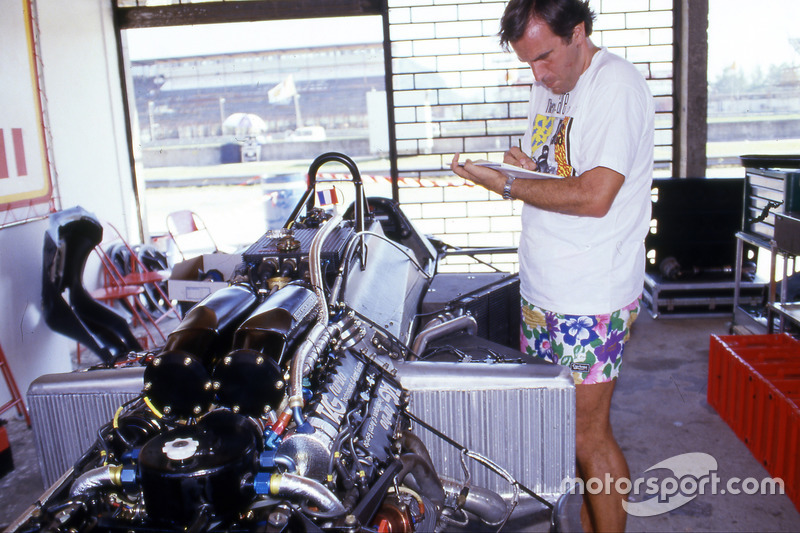

Graphic artist Giorgio Piola takes pictures of car parts. Photo by Eric Gilbert.

Colin Chapman had a reputation for making overly dangerous cars, what do you think about that?

“I think it's fair. If you see one of my best drawings, the Lotus 78, the fire extinguisher had a very thin frame. It would go off even with the smallest touch with the guardrail at 40kph – it was like there was no fire extinguisher.

For sure, Chapman cars were very often dangerous cars. Very, very often. And, for sure, Jochen Rindt died just because the car's driveshaft was hollow and it was too fragile.”

Chapman was obsessed with weight?

“Yeah and he didn't care if he needed to put something that could be explosive just behind the arse of the driver. If he needed to fit it to make the car go faster, he didn't care at all.

I tell you, in a certain way, that reminds of me Adrian Newey's Leyton House car, of Mauricio Gugelmin and Ivan Capelli. For the nose and aerodynamics, it was important to have a wide top and a narrow bottom, with exactly the dimension to fit two feet and nothing more. The driver during the race could not move his feet, so after 20 laps very often they had a cramp in their legs. If you ask Capelli and Gugelmin, they will tell you.

Then there was the steering column made in a way that meant drivers had a difficult time entering the cockpit. But I have to say, a lot of cars in those years were like this. But that car from Adrian was probably the worst one.

When Bernie says that Senna 's death was useful for Formula 1, it sounds horrible. It is cynical. But for sure, if it wasn't for Ayrton, more drivers would have been killed. I am sorry to say this, but nobody cared about Roland Ratzenberger. Nobody even mentions him much anymore. When they talk about Imola, they say it was a tragic Grand Prix only because of Senna – and not Ratzenberger.

Because of the Senna accident, they made a big step in safety. Before that the cars were dangerous. Just look at the pictures – the drivers are out completely of the cockpit, and not protected. So I have to say FIA has made big strides in protecting the drivers.

Jules Bianchi's accident was not an accident of Formula 1. It had nothing to do with Formula 1 design. The truck didn't have to be inside the track. That was the main thing. You remember with Tonio Liuzzi, at the Nurburgring in 2007, he stopped like this in front of a tractor. Another big mistake.

When people say someone's escape was a "miracle", it means another time it won't happen. It was the same with Tamburello. Berger, Patrese, Alboreto, Piquet all were hitting that same wall at Tamburello. And every time we said "miracle", "miracle", "miracle".

Senna was unlucky because of the suspension. His car was completely OK, he could have restarted the race if he wasn't hit by the suspension. He was very unlucky.

But again - if everything goes well, we say it's a "miracle", but that means it is not controlled. Senna dying nobody expected. It was a terrible shock for everybody.

Villeneuve was the previous big driver killed, but – and again it is very sad to be saying this – but every one of us, we knew that, sooner or later, in helicopter crash, or in a car accident, or on a motor boat, or even running, or riding a bicycle, he could have massive accident. Because he was crazy. People liked him, but sometimes you have to acknowledge that he was completely crazy.

Remember him running without a wheel at Zandvoort? Imagine if he spun and someone else came up, that could've been fatal. And there was one driver, I'm not giving you his name, he said to me in an interview after Gilles' death: "Giorgio, I tell you, from now on I drive safe. When I had Gilles in front of me, beside me or behind me, I was always scared I would be involved in big crash in which I'll die. From today on, I'm safe".

I didn't publish it. Our generation, we were all people passionate about Formula 1, so we had certain borders – and this was one of them. You can 't publish stuff like this, even if it would be the biggest headline of the season. If you do, the driver who said it, when he goes to Imola, he would have been killed. Because Villeneuve was beloved by everyone.

It's different with some journalists now. They come to Formula 1, good journalists, maybe from football, so they don't have a passion, they don't have any respect for Formula 1. For example, I don't understand why everyone is blaming Formula 1 for being not spectacular. For me, they are fantastic races.

The only problem for me is that I don't like some of the rules. For example, if there is an unsafe release or if the engine or gearbox expires, why do you penalise the driver? Take away points from the constructor instead. If a driver gets pole position, you see him do the best lap and then his engine is changed, why does he start from the back? This is something I don't like.

On the other hand, I have this example: the Hungarian GP was always horrible. Two or three interesting laps, one beautiful overtake, Mansell v. Senna – than we'd say "wonderful", but then we're sleeping for 70 laps. A couple of years ago, meanwhile, we had one of the best races there, fighting until the last lap. And even at the back with these power units, there are overtaking moves that you could not see before. I don't understand why people complain.

The only thing maybe that nobody cares about is Mercedes. Because if you paint Mercedes in red, people would go mad. Red Bull attracts many more people – you see Verstappen in Belgium? There were so many spectators just because of him.

If you remember Schumi in 2002 was champion in France – we had the six final races of the season with him having already become champion. But everybody was happy anyway, because it was Ferrari.

The races now are wonderful and the level of drivers is good. In Schumi's times, it was only Mika Hakkinen and then Alonso came. Now we have at least five drivers nearly at the same level, like when there were Senna, Piquet, Berger, Prost, Mansell.

If you ask me, I'll say Senna was best driver of my time in Formula 1. Not Schumi, because he was fighting only with one. Senna was fighting with four or five other people that were as good as him. Michael had a very easy life, he won so many championships, but sometimes fighting against nobody.

Barrichello was not even allowed to drink the tea same as Schumi. Rosberg and Hamilton, they had the same material at their disposal. They fought, they collided – there was big competition between the two.”

The 1979 Ferrari 312T4 of Gilles Villeneuve. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

When did you stop writing up reports and interviews?

“It would be 10 or 15 years ago. I started to do more TV commentary on tech and I stopped writing because I had no time.

Now there's the internet. Until 20 years ago, I was working 90 days a year and got four times more than I do now, working 350 days. That's what the internet forces you to do.

The best time was when there were fax machines. I couldn't do drawings with shadows, because it would come out all black - so I had only to do very simple drawings and I had 14 magazines around the world. This was very good.”

So you just needed to dial up 14 numbers?

“Not even that. Because in the press room, there was an assistant – you would give him the envelope with the drawings and the list of numbers. It was fantastic. And I had a very good quality of life, I had three horses, one Ferrari, one boat. That was good.

Now all of that is gone. I sold it. You have no time for that. Riding horses and show jumping is too dangerous if you don't do it regularly. Ferrari? You can have it. The boat I had to switch for one three times smaller.”

But you still do the job.

“I still love it. If you ask me, there's nothing that I like more than see the launch of a new car. I can't wait to see Adrian Newey's car for next year. The passion for my work is still so big. To see a new car, it's something really special, something that makes you forget about everything else.”

Giorgio Piola at work. Photo by Jean-Francois Galeron/WRI2.

Giorgio Piola’s F1 tech decades: the big bang 1980s, part one. By Giorgio Piola. Co-author Matt Somerfield. May 07, 2020.

Giorgio Piola has been at the forefront of F1’s technical coverage throughout his career, helping to make the complex sport we love a little easier to understand. In this series of articles dedicated to his illustrative genius, we’ll uncover the cars that have captured his imagination.

Here we delve into the first half of the 1980s, when ground effect was at its peak (and then banned), carbonfibre chassis became the norm, water tanks to cheat the weight rules and turbocharged engines sent power outputs through the roof.

1980

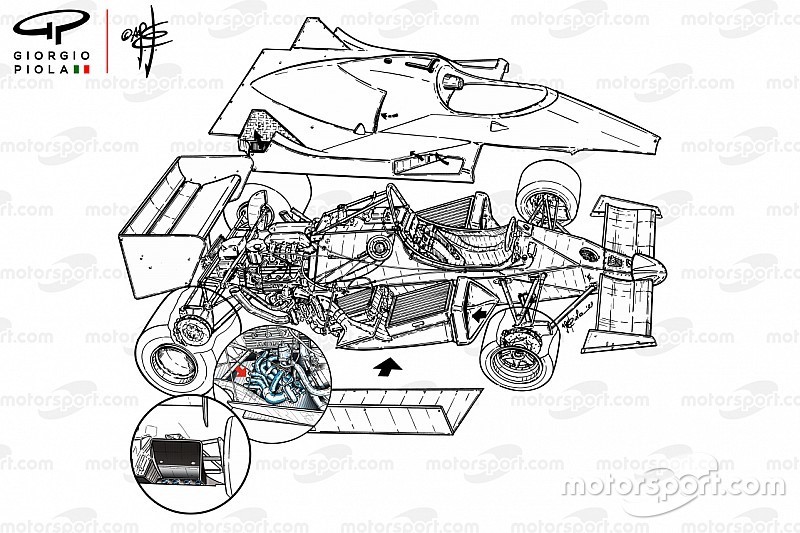

Ferrari 312T5 1980 detailed overview

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The 312T5 was an evolution of the car's championship winning predecessor, but while the flat-12 engine had been part of that success, it was clear that its layout would now start to hinder progress. With most of the teams adopting the ground-effect concept, it would limit the size and shape of Ferrari’s Venturi tunnels and so the T5 would be their flat-12 swansong.

1981

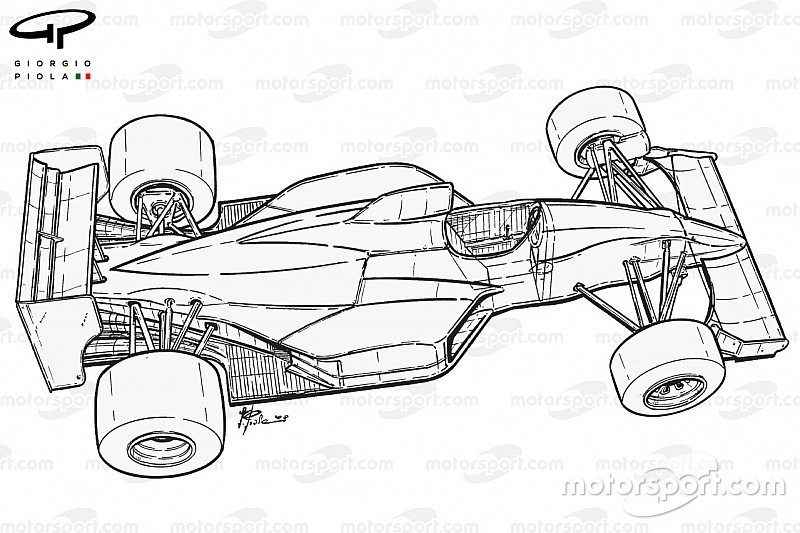

Brabham BT49C 1981

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The Brabham BT49C was a very simple, neat and elegant car that took advantage of the ground-effect concept, with a mini-skirt sealing the side of the car very well. The cutaway also gives us an impressive vista of the Cosworth DFV V8 engine that helped to power Nelson Piquet to one of his three world championships and took Brabham to second place in the constructors’ championship that year.

1982

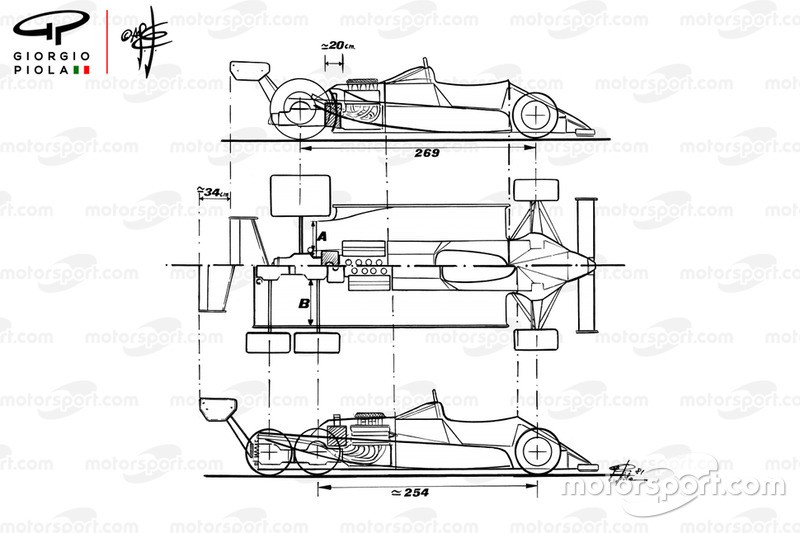

Williams FW08 1982 comparison with FW08B six wheeler

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

We covered Tyrrell’s infamous six-wheeler in the 1970s, but while it was the only one to race it wasn’t the only project in existence... Williams had been busy working on a secret 6-wheeler project, as they looked for ways to bridge the roughly 180bhp deficit from not having a turbocharged engine. Its design would use four narrower wheels at the rear, which reduced drag massively, allowed for a very long diffuser and gave much more mechanical grip from the now four driven wheels. Alas, the FIA stepped in and stopped its introduction before it was raced.

1983

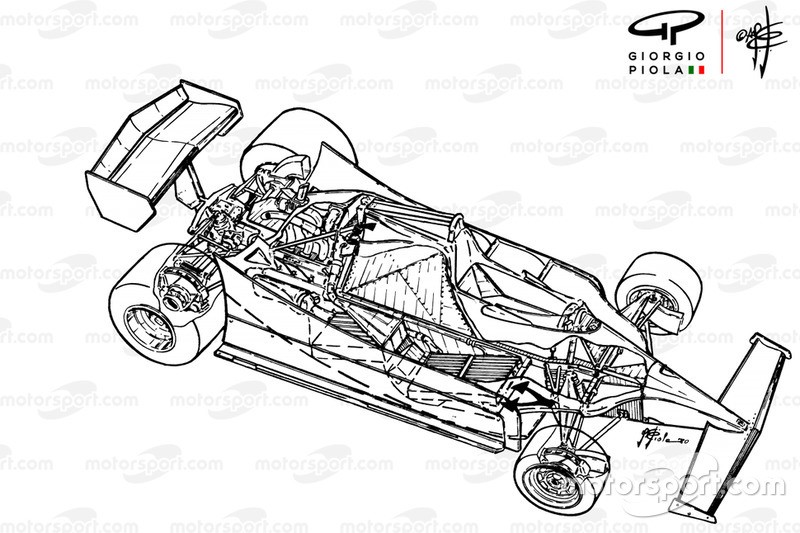

Brabham BT52 1983

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Just before the start of the 1983 season the FIA changed the regulations and banned ground effect. This was a blow to the teams as they’d all designed cars around the concept and would now have to hurriedly accommodate the changes. Gordon Murray’s BT52B was perhaps the most adapted car to line up on the grid in Brazil and featured and elegant design with many features that set it apart from the rest of the field.

1984

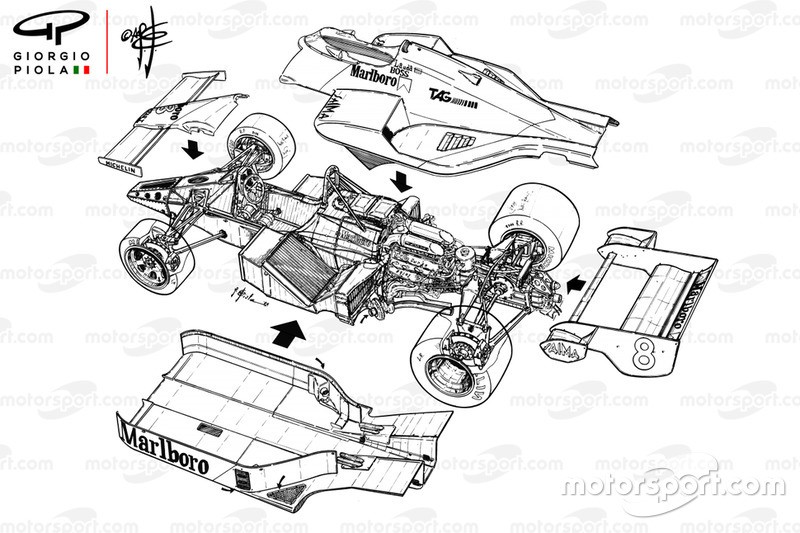

McLaren MP4-2 1984 exploded-detail overview

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The McLaren MP4/2 was an evolution of its predecessor, with the team continuing to take advantage of the lightweight and torsionally-rigid carbonfibre monocoque. The MP4/2 took further advantage of this manufacturing process though, with the lightweight bodywork being contoured in a way that was previously unachievable. This allowed John Barnard to introduce another design that’s synonymous with modern Formula 1: the coke-bottle shape, which resulted in the airflow accelerating more quickly around the car.

Giorgio Piola’s F1 tech decades: the big bang 1980s, part two. By Giorgio Piola. Co-author Matt Somerfield. May 7, 2020.

Here we delve into the second half of the 1980s, when Brabham went low-line, Honda turbos ruled the roost and hit their peak with McLaren and normally-aspirated engines reset the playing field.

1985

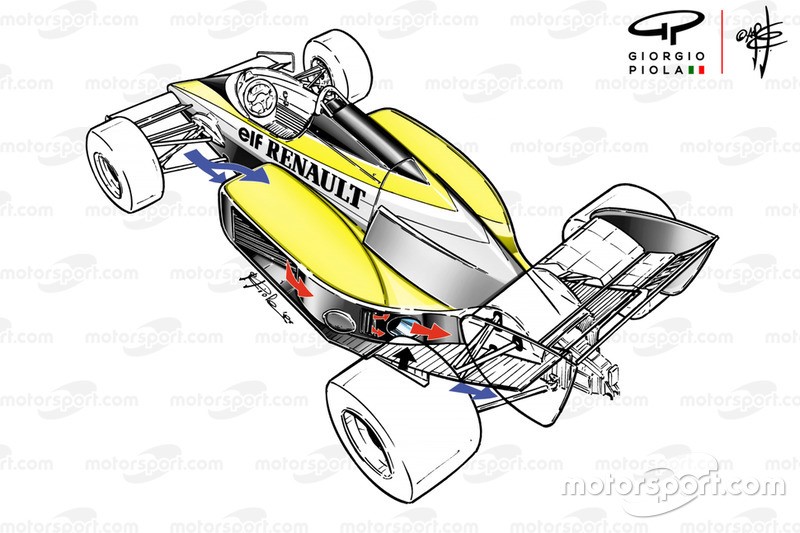

Renault R60

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Not a particularly successful car but, much like its predecessor it placed the exhaust in a position of aerodynamic prominence. But this car did not have the exhausts placed in the diffuser channel, instead they protruded from the sidepods in the coke-bottle region. Again, this may have laid the foundations in the mind of Adrian Newey, as he has pursued this kind of exhaust-blowing tactic on many different occasions.

1986

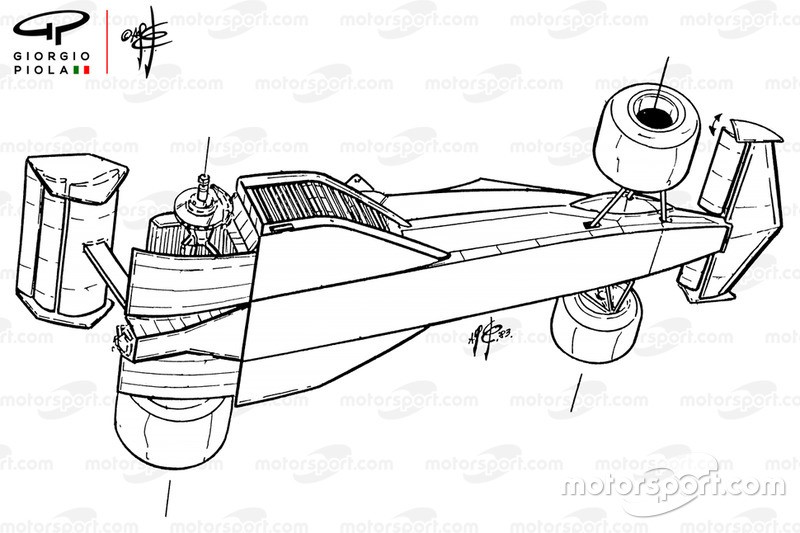

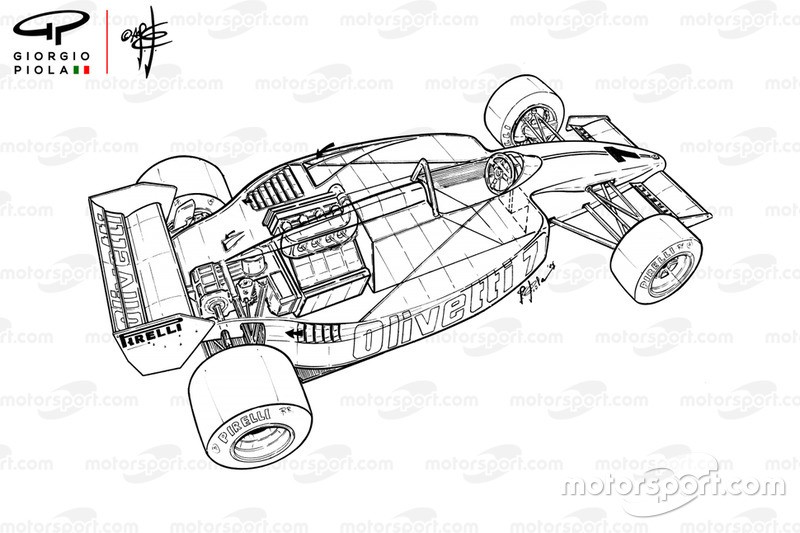

Brabham BT55 3/4 view

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

This was a sketch of the Brabham BT55 done by Piola ahead of the launch and was created to show the direction that Gordon Murray was taking. The idea was to reduce the car’s centre of gravity, which required the designer to tilt the inline-4 cylinder turbocharged BMW engine on its side. This also allowed the entire ancillary and aerodynamic package to follow suit and resulted in a very lowline silhouette.

1987

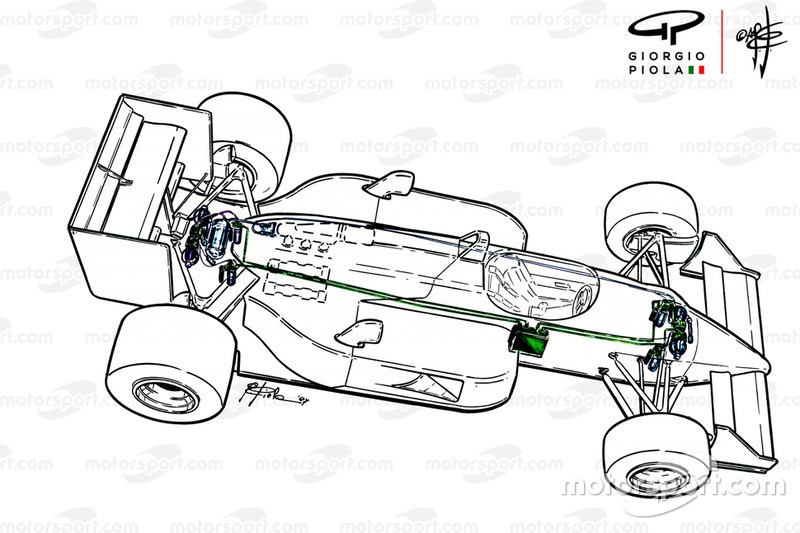

Williams FW11B 1987 active suspension schematic

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Williams once again wrapped up the constructors’ title with the updated FW11, which in 1987 ran the ‘B’ nomenclature. Piola’s illustration shows the teams electronic reactive ride technology, which improved the car's aerodynamic platform and would form the basis for the next few Williams cars. The system had an accumulator at the front and two at the rear, a distributor for each, a hydraulic cylinder to activate the suspension, a potentiometer which would control the hydraulic damper and ride height, a Moog electro valve, a control ECU and a pump which was connected to the left bank of the engine.

1988

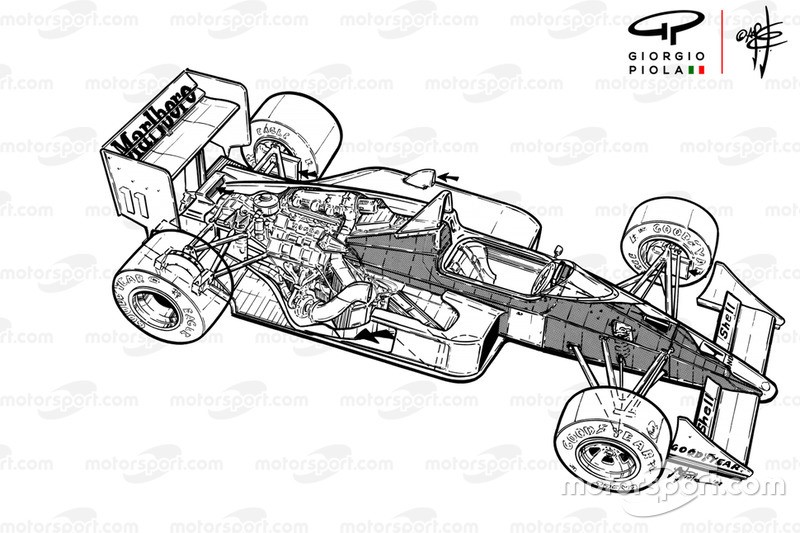

McLaren MP4-4 1988 detailed overview

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

McLaren’s MP4/4 has a cult status as it won all but one race in the 1988 season. It was a Steve Nichols car, but consulted on by Gordon Murray, who’d arrived from Brabham and had put across a convincing argument for his low-line concept. Although this was a failure on the BT55, the concept reaped significant aerodynamic rewards packaged around the turbocharged Honda engine.

1989

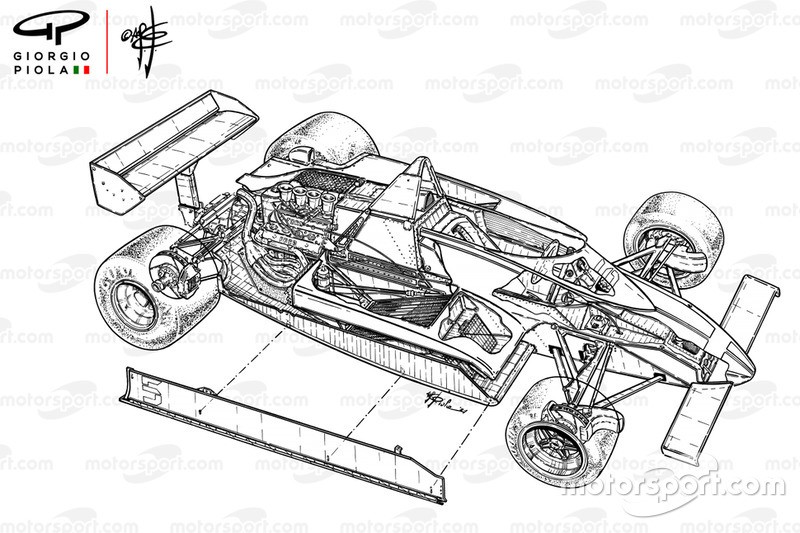

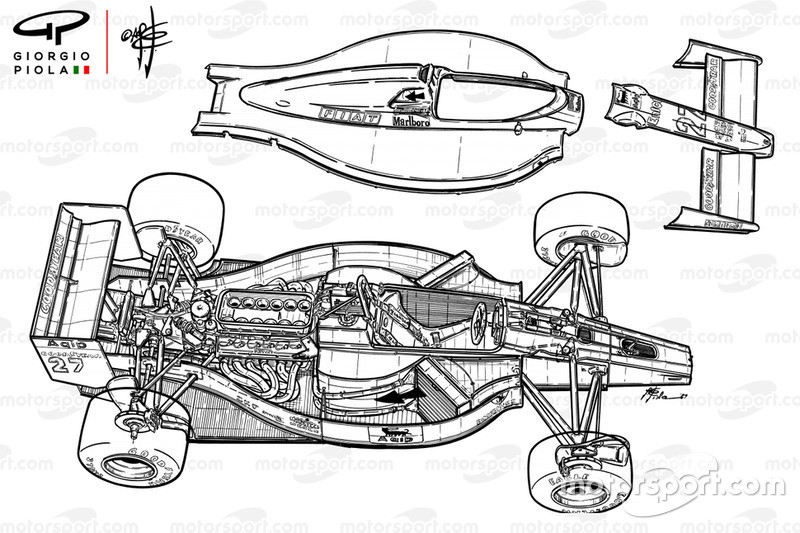

Ferrari F1-89 (640) 1989 exploded view

Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The Ferrari 640 is another car that Piola considers to be a milestone machine, given the technology housed within still forms part of what we see on the grid today. However, he also comments on how beautiful this car was compared with its predecessors, with lovely clean lines – it very clearly had all the hallmarks of a John Barnard car.

Giorgio Piola's history of F1 steering wheel evolution. By Giorgio Piola. Co-author Matthew Somerfield. Sep 9, 2020.

Formula 1 steering wheels have changed dramatically down the years, as more control has been put at the drivers’ fingertips – allowing them to make the most subtle of changes and find the edge over rivals.

The first changes were really all about ergonomics and making the drivers more comfortable with their surroundings, but as time progressed the customization level increased dramatically, with almost every driver having their own signature aspects incorporated into their wheel design.

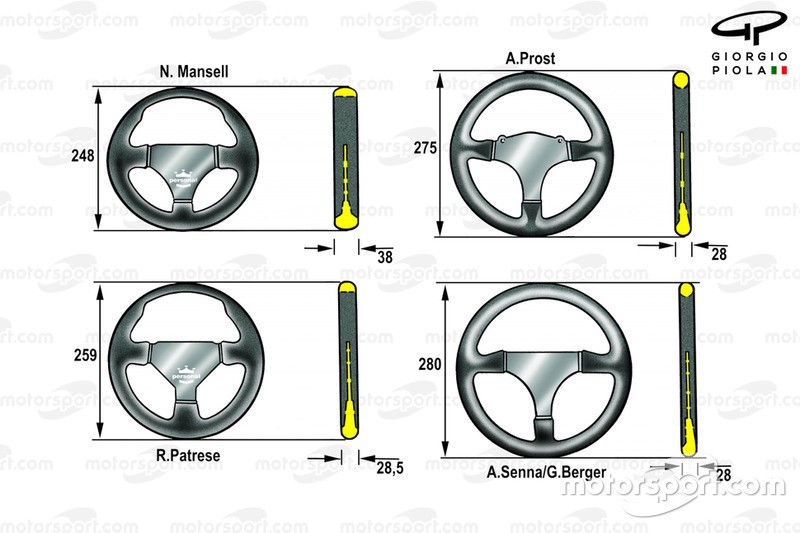

MANSELL v PROST v PATRESE v SENNA & BERGER

Steering wheel Mansell, Prost, Patrese, Senna, Berger. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

At this stage of his career, Giorgio Piola was working with Nardi and Personal on their steering wheels. And, whilst they were based in the same factory, the former (a more prestigious brand) only supplied steering wheels to McLaren.

This allowed Piola to work closely with each driver to give them the individuality in their steering wheel they desired. The wheel was not only an expression of their singularity but also gave insight into their driving style, which as we can see here from this comparative illustration resulted in some very different shapes and sizes.

For example, Mansell, who was known for wrestling with his car, opted for an extremely small diameter rim, whilst also having the thickest grip too. Even so, for two years in a row, a new wheel rim had to be supplied after the Belgian GP, as he exerted enough force on the wheel rim through Eau Rouge and Raidillon that it resulted in him physically bending it.

At the other end of the spectrum, the likes of Senna had a large diameter wheel and much thinner grip, as his driving style was more delicate and less demanding on the integrity of the wheel itself.

Nevertheless their grasp on the wheel, the freedom to use it remains imperative to performance. This small gap between the drivers and engineers choices couldn’t be clearer than when Senna moved to Williams in 1994.

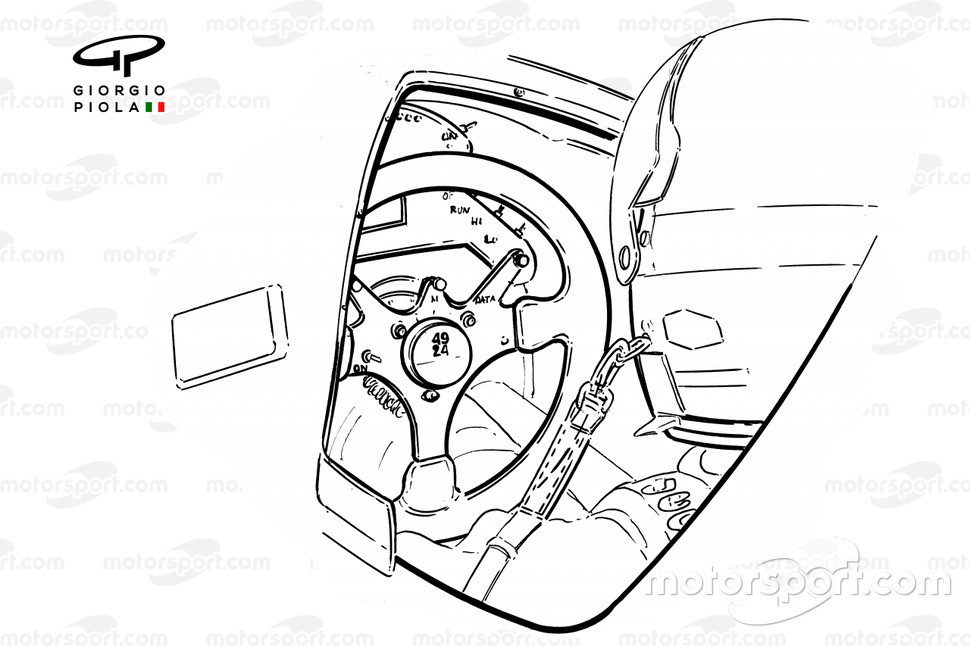

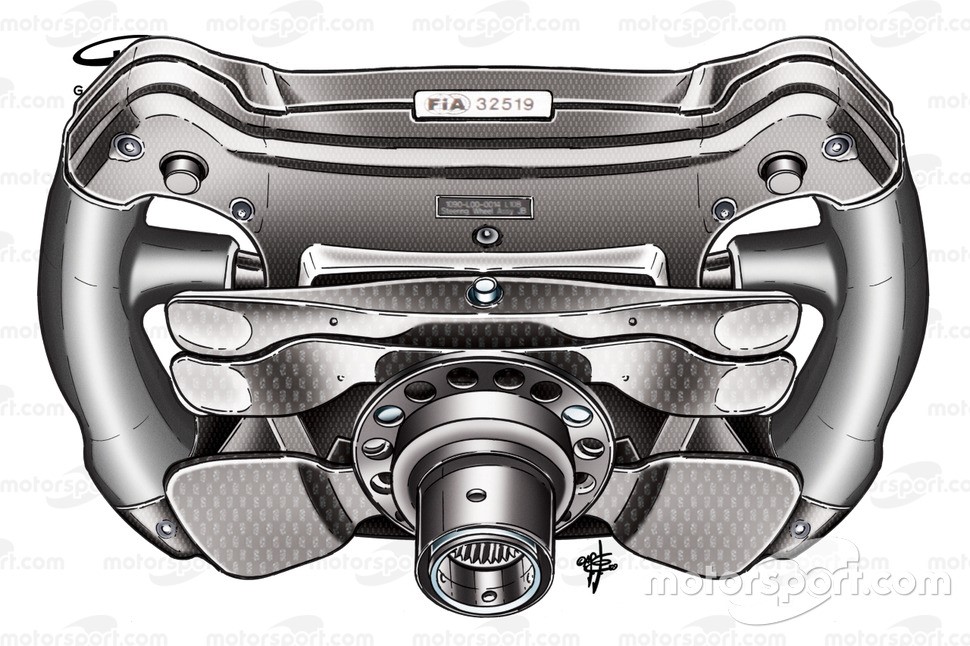

McLAREN MP4-8 v WILLIAMS FW16

Senna had become accustomed to more freedom within the cockpit during his McLaren tenure, as seen here whilst at the wheel of the MP4-8, whilst the FW16 featured what had become a trademark for Williams over the course of the previous few years – a cockpit that enveloped the steering wheel for better aerodynamic performance.

The FW16 and its forebear, the FW15C featured a tight, V-shaped cockpit entry, meaning the driver's hands ran incredibly close to the cockpit even if using a smaller diameter wheel, like Mansell, let alone the larger one used by Senna.

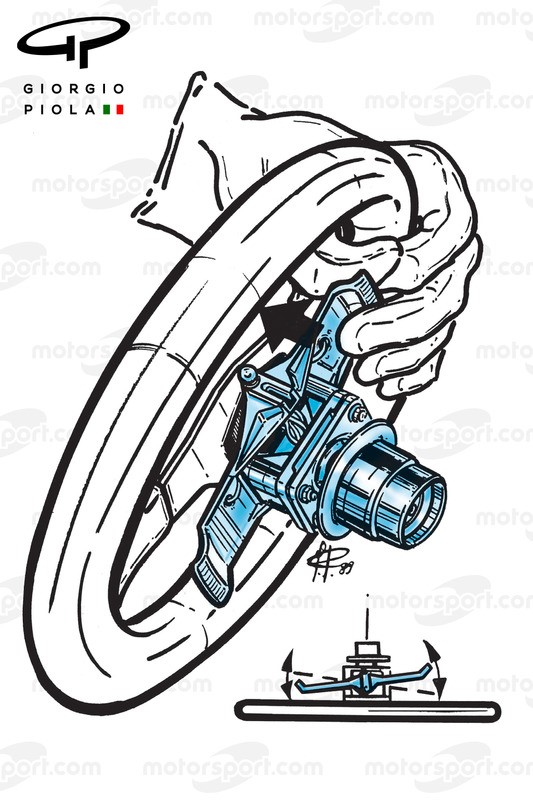

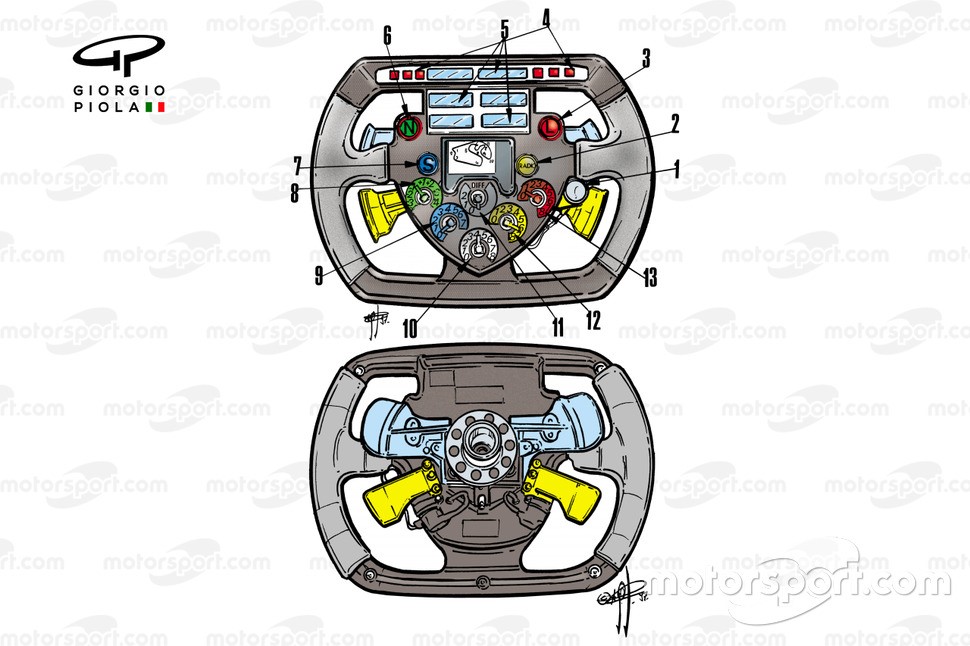

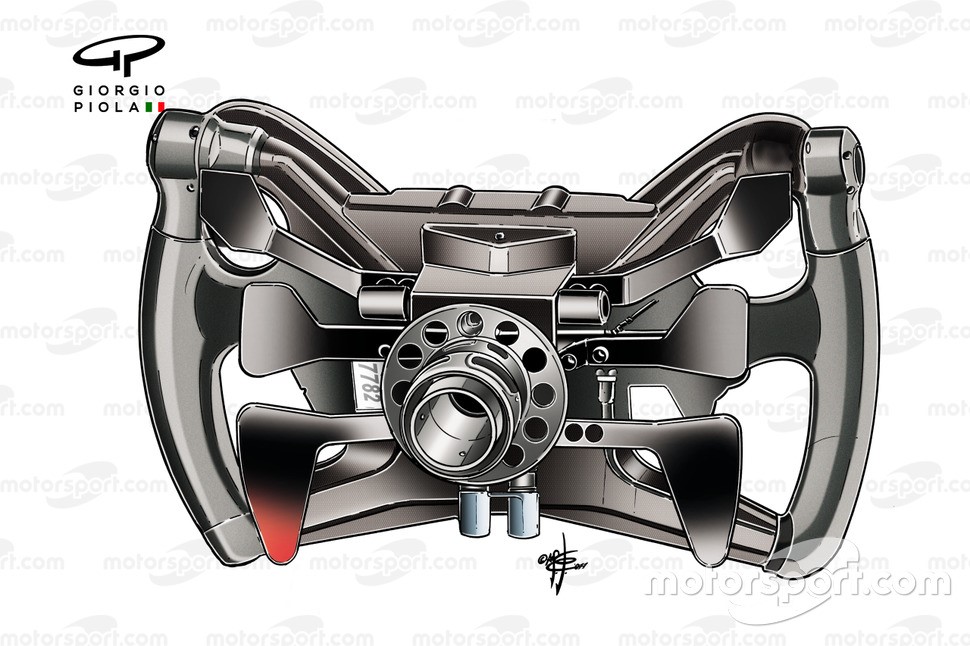

FERRARI 640

Ferrari 640 steering wheel. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

This illustration remains a favorite amongst Piola’s portfolio, as it took a relatively short time to produce but was rewarded with significant exposure.

Used by publications around the world, the illustration captured a new and innovative solution by John Barnard, as his design for the Ferrari 640 featured paddle shifters on the rear of the steering wheel, rather than the standard manual H-pattern gear lever mounted down to the driver's side.

MIKA HAKKINEN v DAVID COULTHARD AT McLAREN

McLaren took things a stage further in 1994 when it was the first to move the function of the clutch on to the rear of the steering wheel, seen here later using four paddles on the MP4-13. The two blue paddles are gear shifters, whilst the lower pair gave the drivers the option of controlling the clutch with either hand.

Hakkinen had cut his teeth on this approach but when Coulthard moved across from Williams, the Scot used longer paddles on his wheel to help with the feel. In fact, so alien did this feel to him that he retained a slim clutch pedal for those moments when he wasn't able to react quickly enough with the paddles. This became even more clear when McLaren’s brake-fiddle solution was discovered – Hakkinen had three pedals, but there were four squeezed into Coulthard’s footwell.

Also note that while Hakkinen adopted the butterfly-style wheel, Coulthard still felt the need to have a lower grip on his rim.

FERRARI F310

Ferrari steering wheel. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The complexity of the steering wheel continued to spiral upward, with more functions being transferred to the wheel and it became loaded with more and more buttons, switches and rotaries. In 1996 Ferrari was the first to incorporate a display on there too. This gave its drivers shift lights, lap times and other information that they required without needing to look through to the dashboard.

HOW KUBICA EMULATED VILLENEUVE

Steering wheel Villeneuve 1997 Kubica 2019. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Jacques Villeneuve had a unique approach to using the paddle shifters on the rear of his steering wheel. Other drivers used the left paddle for downshifts and right paddle for upshifts, but he did both from the right-hand paddle – pushing the paddle away for downshifts and pulling it toward him for upshifts. The left-hand paddle was used exclusively for the clutch, reducing the number of paddles needed on the wheel.

You can also see how, upon his return to F1, Robert Kubica used a similar arrangement of a push/pull gearshift paddle (normal layout inset), as the Polish driver customized his wheel in accordance with his injuries.

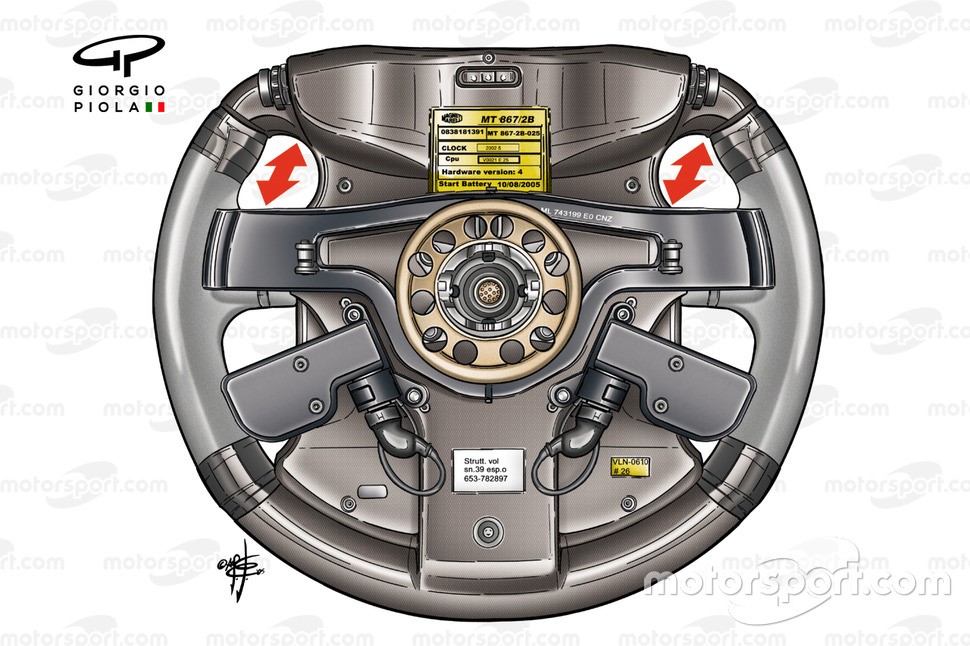

FERRARI & SCHUMACHER

Ferrari F2005 steering wheel. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Michael Schumacher made changes to his paddle arrangement, adopting an approach similar to Villeneuve's.

But, rather than have just one paddle with double the functionality, the German opted to keep both paddles, which allowed him to shift up or down the gears depending on his hand position or preference at any given moment.

FERRARI & ALONSO

Ferrari F10 steering wheel. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Fernando Alonso’s arrival at Ferrari was met with an effort to make the Spaniard more comfortable within the cockpit, shaving some of the unnecessary bulk from the upper and lower sections of the wheel, while the shape of the grips, position of the rotaries, buttons, central wheel spoke and rear paddles were all shifted to cater for his demands.

Also note the placement of the PCU-6D display at the top of the wheel. That became a common display used by all the teams and gave them all the same shift and safety lights, gear indicator and various other information, such as lap time, lap delta etc.

BRAWN GP COMPARISON

That’s not to say that this suited every driver, with Jenson Button’s wheel outfitted with a six-paddle arrangement on his championship winning Brawn GP BGP001 steering wheel, while his teammate, Rubens Barrichello preferred to use just the four paddles.

Note how close the upper paddles are mounted on Button’s wheel though, with the driver able to use them in combination with one another, should he have chosen.

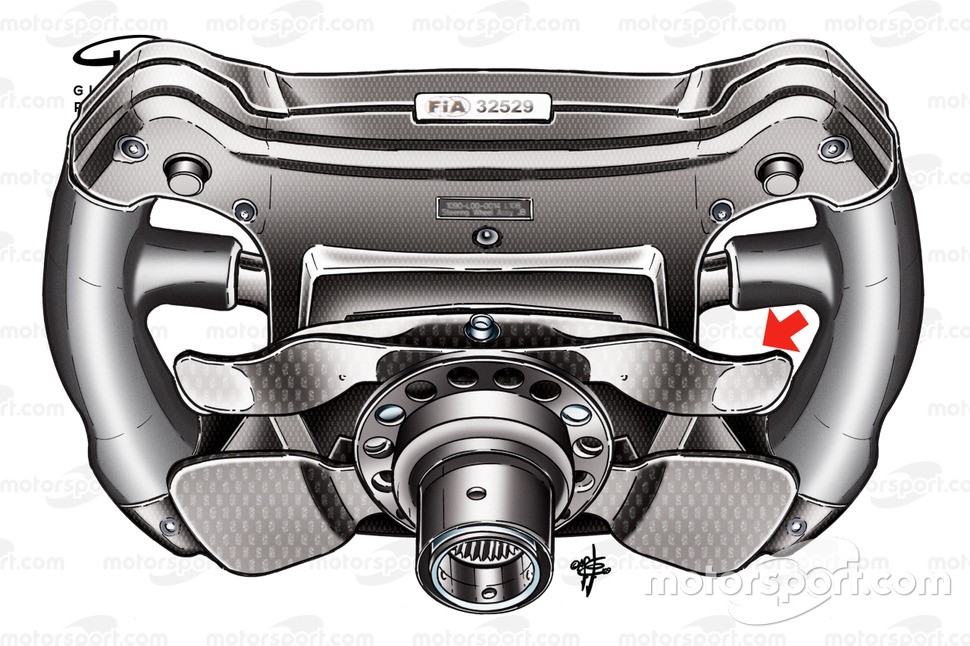

VETTEL v WEBBER AT RED BULL

Red Bull RB7 Vettel's steering wheel, rear view. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

In recent times Formula 1 teams have taken to giving their drivers the same core wheel design but there’s still subtle differences that can be made to improve each driver's use of the equipment, which can be seen here with Webber and Vettel sporting different shapes to the paddles on the rear of the RB7’s steering wheel (highlighted in red).

ALONSO v MASSA AT FERRARI

Ferrari F10 steering wheel differences (Alonso vs Massa). Photo by Giorgio Piola.

This preference can extend beyond the wheel itself too though, as seen here in this example between Fernando Alonso and Felipe Massa in 2010.

The position of the wheel from a driver’s body is often reflected by their distinct driving style, with Alonso wanting the wheel to be closer to him, in order that he had more bend in his elbows. Meanwhile, Massa preferred to have less bend in the elbow and had his wheel further away from his body.

BMW SAUBER & RENAULT

The design of the steering wheel is a constant balancing act between ergonomics and functionality, with the drivers, designers and engineers having to weigh each of their demands against one another to improve performance.

Nick Heidfeld’s steering wheel for the BMW Sauber F1.09 shows the level of complexity that can be reached when it comes to the grips, with every sinew perfectly shaped to take account for Heidfeld’s hand position on the wheel.

Meanwhile, Renault took paddle usage at the rear of the wheel to another level in 2011, as the R31’s steering wheel featured eight paddles, with two smaller paddles nested between the rim and the two lowermost paddles.

INTO THE HYBRID TURBO ERA

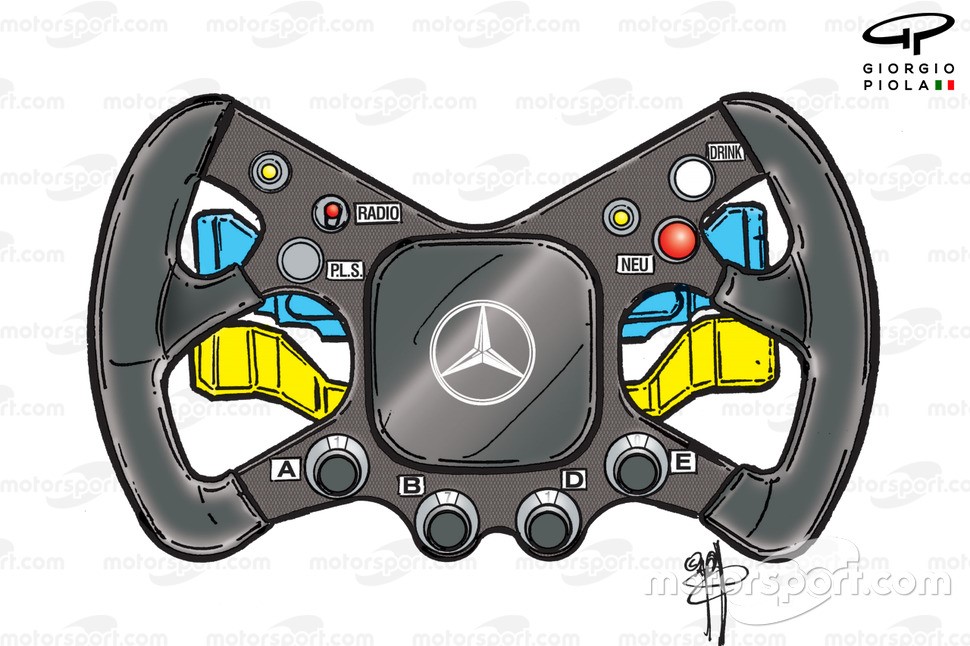

Mercedes W05, Hamilton's steering wheel, front view. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

A new screen was developed by McLaren Applied Technologies for 2014 to coincide with the switch to the hybrid power unit, offering significantly more information for the driver. But its inclusion also meant giving up important real estate on the wheel and so many teams carefully redesigned their wheels to accommodate it.

The newer PCU-8D can display 100 pages of information, all of which is customizable, giving the team and driver a wealth of information and allowing them to monitor the various aspects of the hybrid power unit and other crucial data, such as tyre temperatures.

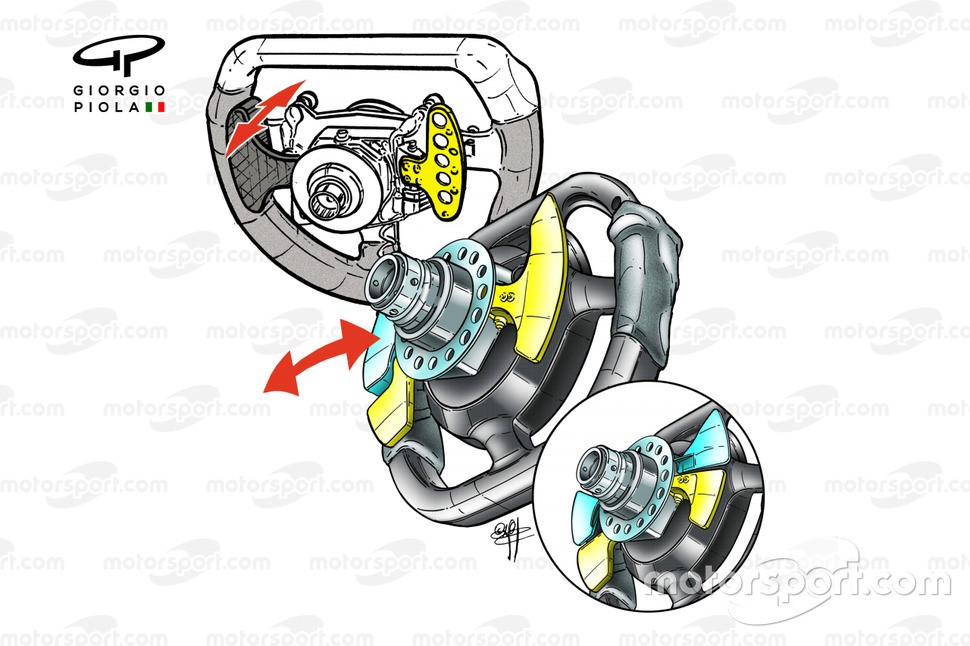

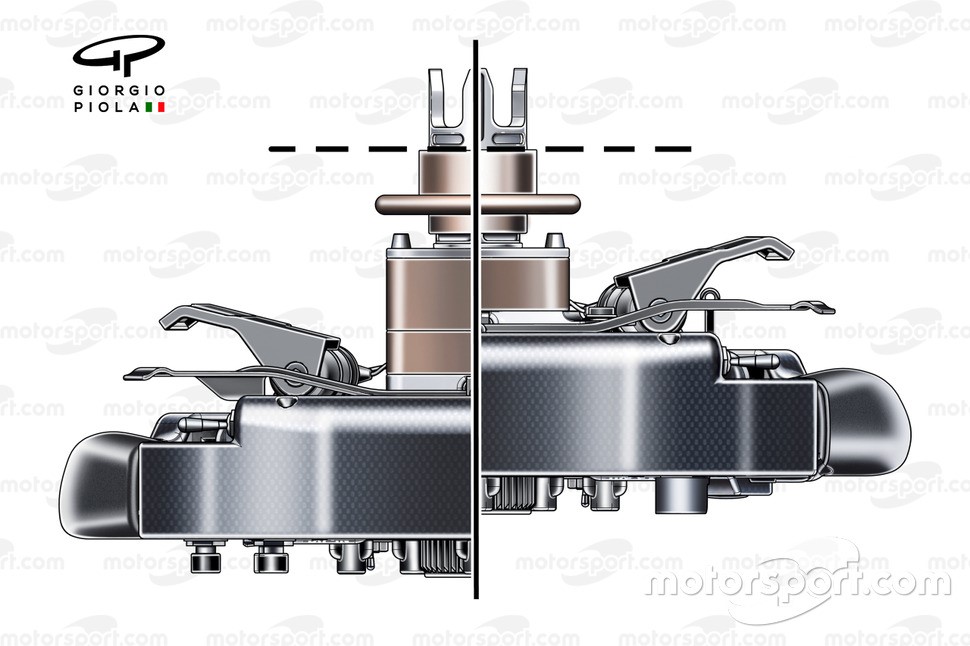

HOW THE FIA PUT MORE CONTROL BACK IN DRIVERS' HANDS

Mercedes AMG F1 W08, steering wheel Lewis Hamilton. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

In 2015 the FIA started to remove bite-finding techniques from the drivers’ arsenal, as they attempted to bring back some autonomy, rather than have an almost perfect launch from the grid each time. Instead, the drivers would have to control how much slip the clutch had.

A number of solutions grew up in response to the changes made by the FIA in the subsequent years, with Hamilton adopting a socket on his clutch paddles (red arrows above) in order that he could get more feel from his index and middle finger when modulating the clutch paddle.

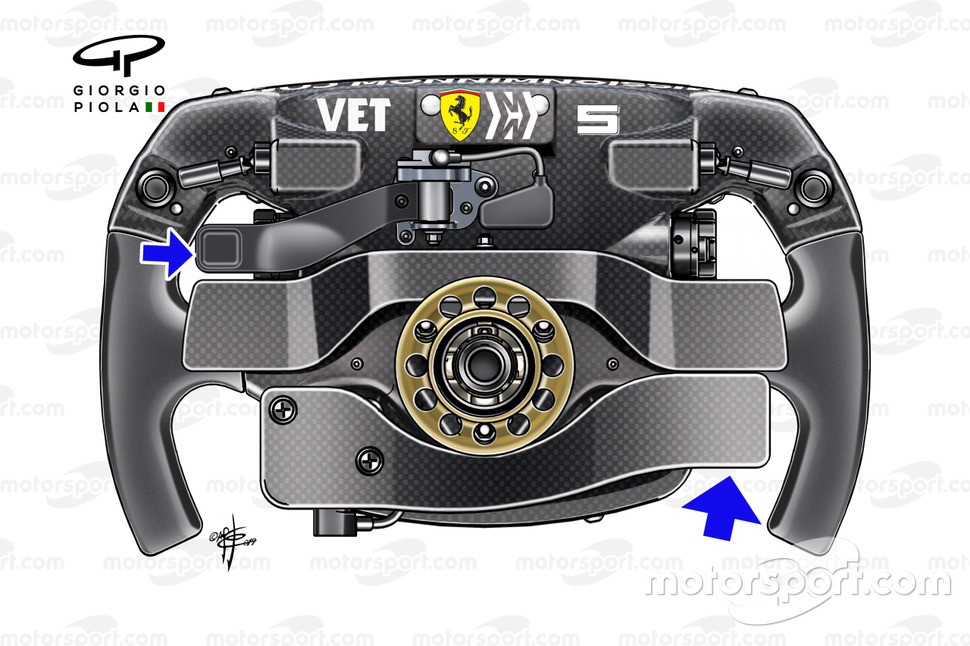

HOW FERRARI ADAPTED

Ferrari SF16-H steering wheel (shows wishbone clutch paddle arrangement). Photo by Giorgio Piola.

Ferrari had taken a different approach, opting for a single longer wishbone-style arrangement that would give its drivers more throw in which to find the bite point on the start line. And while Kimi Raikkonen persevered with this arrangement throughout, Sebastian Vettel made numerous attempts at finding his own sweet spot.

The German driver’s experiments began at the Spanish Grand Prix, as he trialled a design with a similar finger socket arrangement to the one used by his rival, Hamilton. Considering the experiment a failure, following the famed start crash at the Singapore GP in 2017, he finally reverted to the wishbone arrangement.

LECLERC v VETTEL

Interestingly Leclerc and Vettel have different preferences when it comes to their clutch too, as Vettel uses his left hand to modulate the wishbone clutch paddle and has a small finger width paddle on the right (smaller blue arrow).

Leclerc uses his right hand, as seen here in Giorgio Piola’s illustration of the Frenchman’s wheel from his maiden Ferrari victory at the Belgian GP.

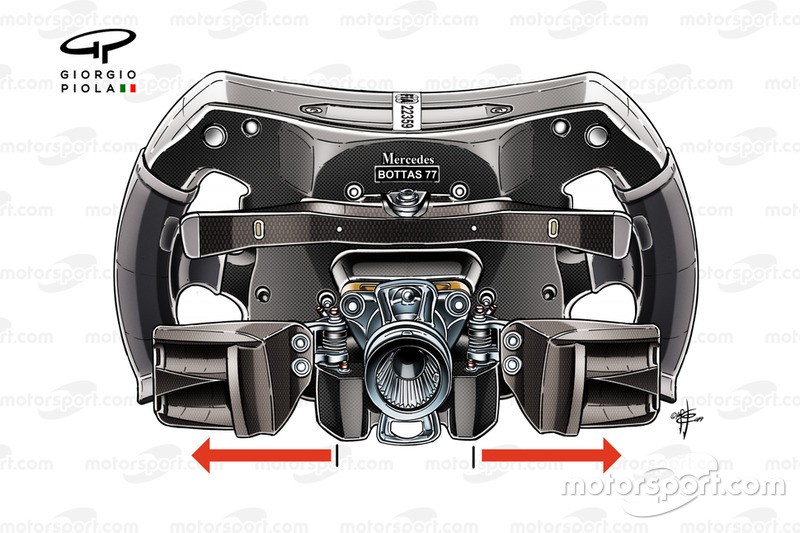

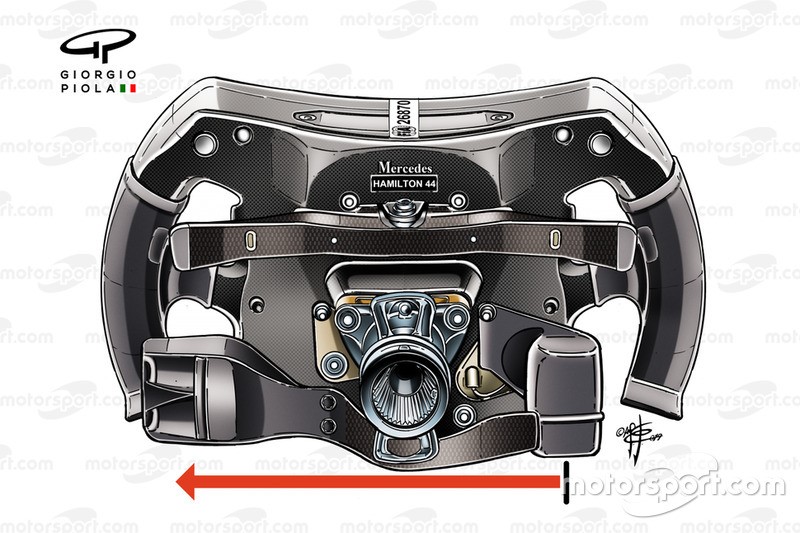

HOW BOTTAS AND HAMILTON DIFFER

The Mercedes pairing also have a decidedly different arrangement on the rear of their steering wheels too, as while Bottas joined Hamilton in his use of finger socket clutch paddle arrangement, the Brit has moved onto a more customized variant using just the right-hand paddle to modulate the clutch.

You’ll also note the design of the finger sockets are also slightly different too, which is in order for him to get the right leverage whilst he holds the upper left corner of the wheel during his start process.

MAX VERSTAPPEN'S CURRENT SETUP

Red Bull Racing RB15, steering wheel Max Verstappen. Photo by Giorgio Piola.

The rear of Max Verstappen’s steering wheel is outfitted with six paddles, as the Dutchman uses the rear space to offer more versatility in his setup.

Interestingly teammate Alexander Albon has tried several variations, including the same layout favoured by Verstappen and one run by Pierre Gasly, which features different paddle positions and a socketed clutch paddle.

Giorgio Piola's incredible career in motorsport. Published on Thursday September 24th 2020.

Giorgio Piola is a much-celebrated figure within the Formula 1 paddock, famous for his technical artworks that span over 50 years of the championship's history.

Having first attended the 1969 Monaco Grand Prix, Piola continued to document the evolution of F1 car design over the next five decades and continues to illustrate technical developments today in his own inimitable style.

"I was always passionate in making drawings of everything," remembers Piola, "but from 14 years old, I concentrated on cars, especially Formula 1 cars. I was always making drawings even at school, listening to the teacher, but making the drawing in the same time.”

"And this way, I could teach my eyes to be able to see like a wide angle view and to see in two opposite directions, so my drawing on the table and the teacher on the desk and this helped me a lot in Formula 1 because I'm able to spot any little detail, even without the people are really thinking that I'm looking at it."

Piola's formative days of drawing in school laid the foundations for a career in motorsport, producing vast, sprawling illustrations of some of the most iconic cars in F1's history. One of his most famous drawings is of the Lotus 72, one of the most technologically advanced cars of the early 1970s and still influences the design of modern F1 machinery, and the original drawing was two metres in length and took Piola 40 days to complete.

Today, Piola's work has taken on more modern techniques, but he still remains faithful to his roots and produces the original drawing by hand before making any further modifications digitally.

Another aspect of his work that Piola remembers fondly is of being able to speak openly with the engineers of the cars he drew - although relationships sometimes became strained when Piola discovered new designs and devices that the designers wished to keep secret.

He once drew the ire of Ligier designer Gerard Ducarouge, having come across a hidden valve system on the Ligier JS11 - known as the "clapet" - at Watkins Glen which stalled the ground effects to improve top speed, but Piola celebrates other feted technical personnel for being willing to talk about their innovations with him.

Today, his illustrations concentrate on the race-by-race upgrades produced by teams across the grid, bringing life to the new innovations that modern F1 teams can often develop. This eye for detail and innovation now also extends to his passion for designing high-end Swiss watches, works of art which he is proud to present to his fans and the motorsport community.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment