The race of races. A thrilling competition, a very hard test, a madness. Many kilometers at very high averages during the day and at night, gruesome accidents. Fighting with the circuit, the weather, the car but, above all, with yourself. Because in Le Mans if you have bad luck you die. In the 1960s, at Le Mans you were racing at 230 miles per hour. And with the brakes of the time ..., what kind of men could have wanted to drive like this? A lot of traffic of very fast cars fighting with the chronometer, an explosive cocktail, but this is precisely the charm of this unique race. Winning at Le Mans is one of the goals of every driver, even of those of Formula 1. A romantic race, full of history and fascinating anecdotes. A test for real drivers and real men. 24 hours that are worth a lifetime.

Ferrari enters the Le Mans Hypercar era. Maranello, 24 February 2021. Ferrari announces the start of the Le Mans Hypercar (LMH) programme that, from the 2023, will see the manufacturer enter the new top class of the FIA World Endurance Championship.

Fifty years after its last official participation in the premier class of the World Sports Car Championship in 1973, Ferrari will take to the track in the Hypercar class of the FIA World Endurance Championship, which it proactively helped to establish. It has a respectable record in closed-wheel competition with 24 world titles (most recently in 2017) and 36 victories in the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Following a period of study and analysis, Ferrari has kicked off the development of the new LMH car to include in recent weeks the design and simulation phases. The track testing programme, the name of the car and the drivers who will make up the official crews, will be part of future announcements.

Ferrari President John Elkann commented: “in over 70 years of racing, on tracks all over the world, we led our closed-wheel cars to victory by exploring cutting-edge technological solutions: innovations that arise from the track and make every road car produced in Maranello extraordinary. With the new Le Mans Hypercar programme, Ferrari once again asserts its sporting commitment and determination to be a protagonist in the major global motorsport events”.

24 Hours of Le Mans, the most beautiful in the world. What is the best sporting event in the world? According to National Geographic, the 24 of Le Mans wins. In the book “The 10 Best of Everything”, published by the magazine, in the top ten dedicated to sports events at number one there is the French car race.

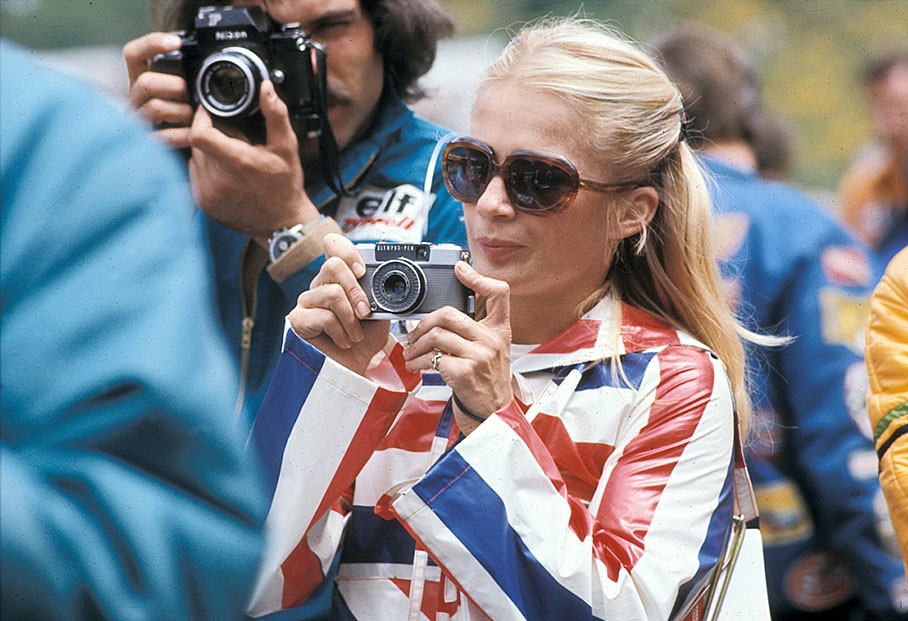

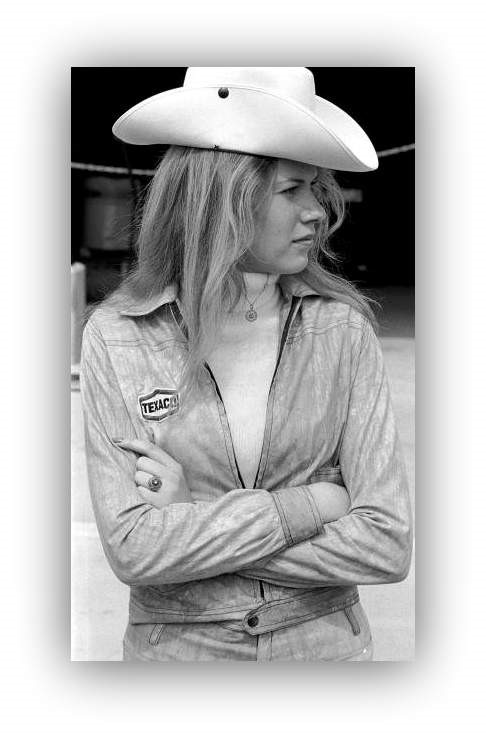

Clermont Ferrand, 1972.

Vintage grid girls, Nivelles-1972.

Considered the most important race within the FIA Endurance World Championship, National Geographic has crowned it queen because of the three "S" that it contains: Speed, Skill and Stamina, or speed, skill and endurance. And also because, with cars of various types competing together, the mix that is created is particularly compelling for the public. In second place are the Olympics. Third is the World Cup, followed by the Super Bowl (American football). Fifth place for the NBA in basketball. Sixth place for the American golf tournament “The Masters”, while in the seventh we find the Argentine polo championship. Only eighth is the famous Anglo-Saxon “Wimbledon”, dedicated to tennis. The American World Series close the ranking in ninth place (baseball) and the tenth place is taken by “The Grand National”, the English event dedicated to horses.

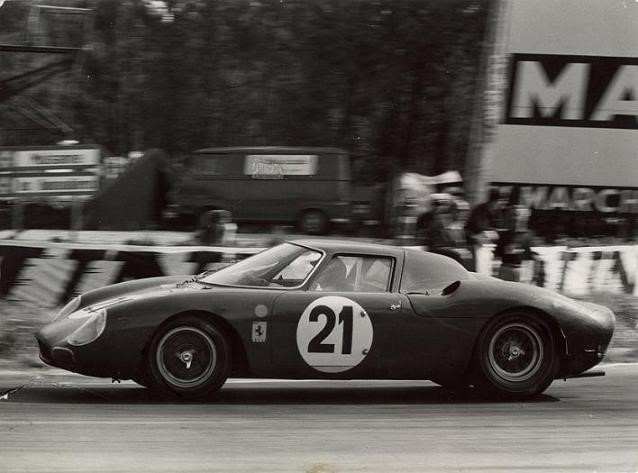

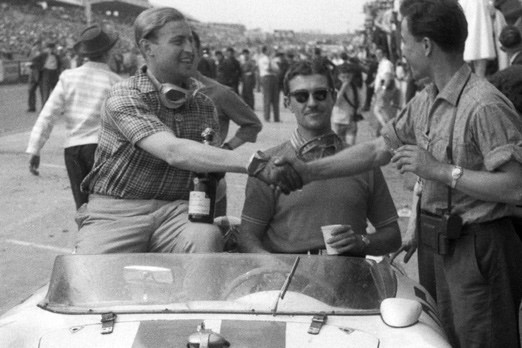

Mauro Forghieri and a Ferrari 250LM at 24 Hours of Le Mans testing.

The unconfirmed true story of Ferrari’s last Le Mans win. By Yoav Gilad. May 19, 2014.

According to historical records, what you’re about to read “never happened”.

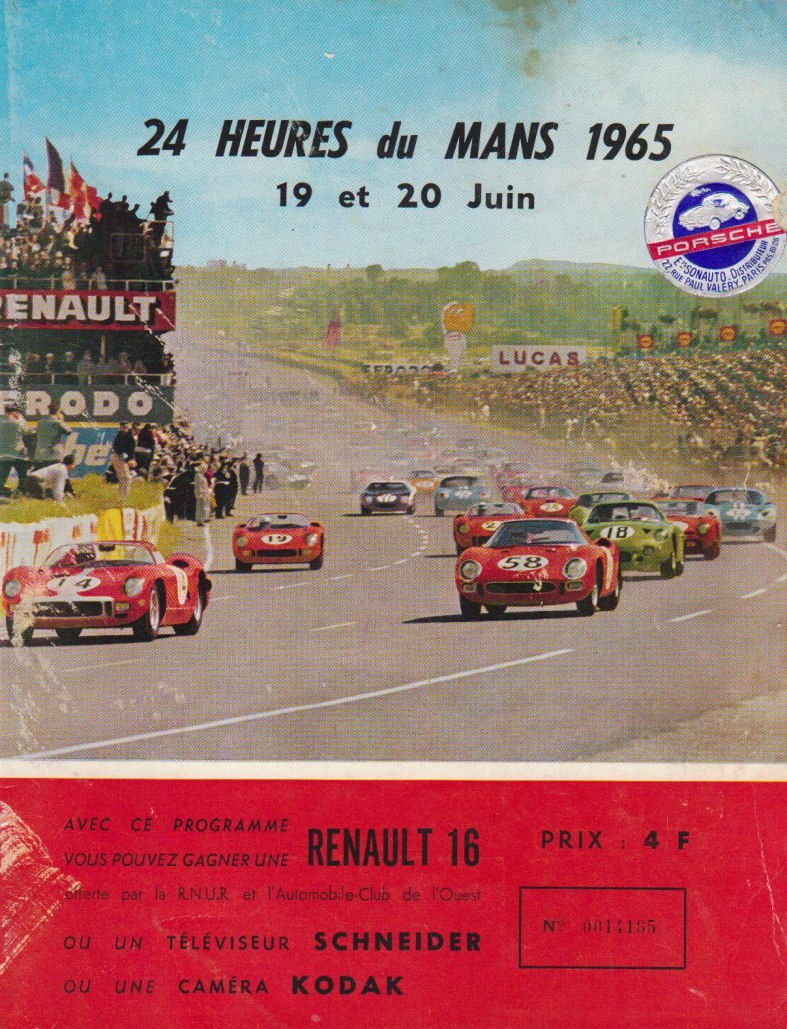

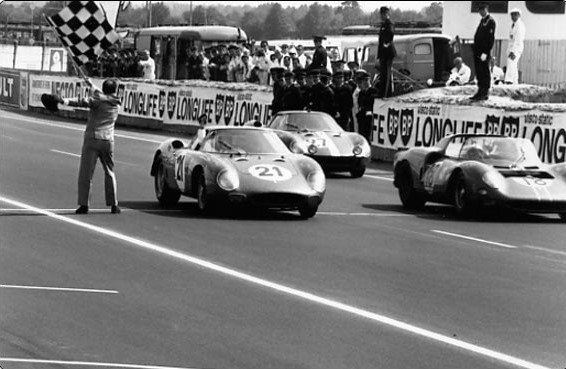

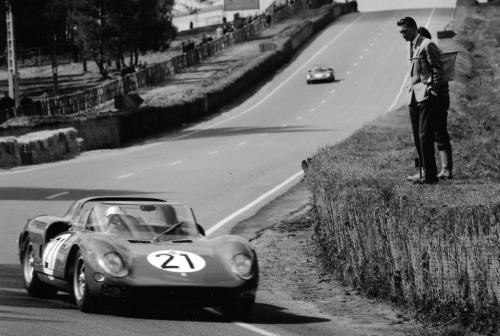

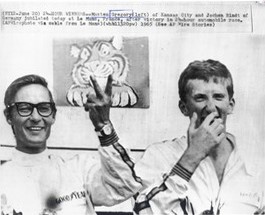

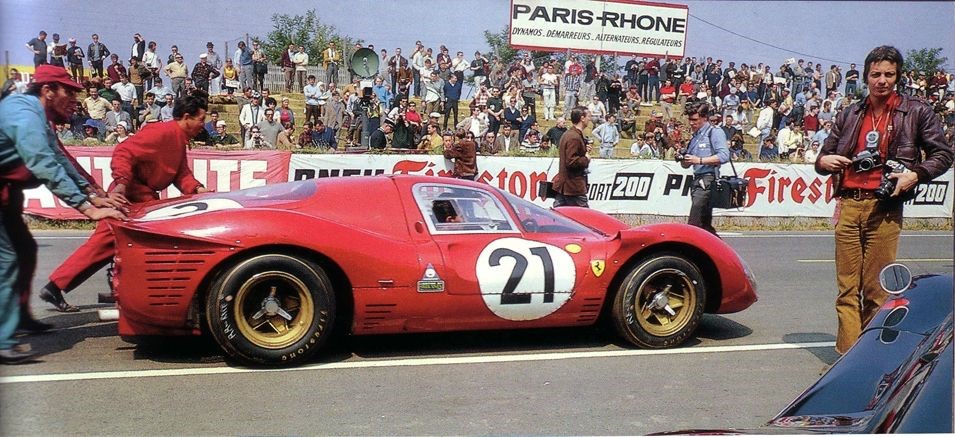

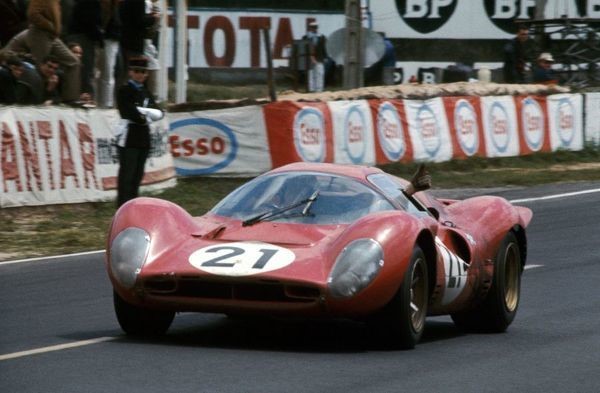

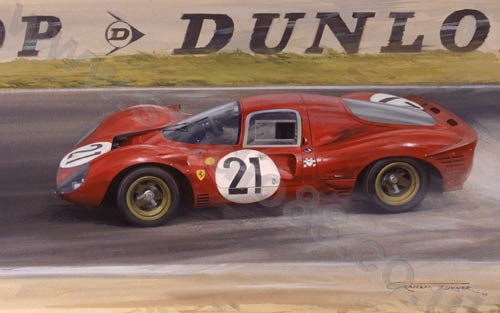

In June of 1965, the 33rd Grand Prix of Endurance, the 24 Hours of Le Mans, was held, as usual, at the Circuit de La Sarthe and was ultimately won by the North American Racing Team’s #21 Ferrari 250LM. It beat out various other Ferraris as well as the arguably favored Ford GT40s and was piloted by Masten Gregory and Jochen Rindt. But some reports indicate that a third, unregistered driver did a stint behind the wheel.

By midnight, all of the Fords had retired for one reason or another leaving the Ferraris to fight it out. As the night air cooled, fog descended shrouding the circuit in gauzy darkness. Masten was on the track and the 250LM was running well, having overcome an ignition issue. It wasn’t leading, but it was in contention when Masten pitted, likely due to issues stemming from his vision.

Surprisingly for a racer, Masten had notoriously nearsighted vision and wore very thick glasses (Carroll Shelby called them “Coke bottles”). As his own brother, Riddelle, commented, “once we were driving down to Texas and Masten had me do the night driving through Oklahoma because he couldn’t see very well at night.”

Masten screeched to a halt in the lonely pits during the small hours and a frantic search began for Jochen. Unfortunately, he was nowhere to be found. And why wouldn’t Jochen be around? Well, it seems that he arrived at Le Mans rather late with some sources indicating that he only arrived in time for the last practice period (due to contractual conflicts) and didn’t seem to think the Ferrari would be competitive. Some anecdotes even claim that he had made dinner plans in Paris for that evening! And others claim that he drove the car hard, hoping that something would break.

Regardless, Gregory jumped out and Ed Hugus jumped in. “Wait, who?” You might be wondering who Hugus is and I don’t blame you, as he was never listed as a Le Mans winner nor was he even mentioned as a driver of the #21 NART Ferrari. But he was very competitive in top-tier sports car racing (finishing, nearly always in the top ten, at Sebring, Le Mans and many others) and was the first Shelby dealer.

Being a Shelby dealer or even a racer obviously doesn’t mean he could’ve driven the car though. But, Hugus was at Le Mans and he was actually a NART driver. In fact, originally he was supposed to drive a different car that wasn’t completed in time for the race. But apparently, if you believe the story, he was in the pits, jumped into the 250LM’s cockpit and drove the car while Gregory rested and Rindt was located. He had the experience to drive too, as this would have been his tenth consecutive year behind the wheel at Le Mans.

So he strapped in and headed into the dark, pea-soupy night in the wailing three-point-three liter Ferrari. His drive was solid and the Ferrari gained several seconds on the leader with each lap, allowing them to make some of the time lost struggling with the aforementioned ignition problem. Around the time the sun began peeking over the horizon and the groggy track, Masten jumped back in.

Ultimately, the Pierre Dumay Ferrari 250LM leading the race suffered a tire deflation that also damaged some of the Belgian-yellow bodywork allowing the NART Ferrari to make up the one minute difference and finally win the endurance race.

But here’s the problem: “officially none of this ever happened!” The race results show Gregory and Rindt as the winning drivers. There is no mention of Hugus even being an entrant in the race. And photos of the podium celebration only show Gregory and Rindt. So how could this French suburban-legend spring up?

The one point that reconciles the claims and circumstantial evidence is that, according to historian Dr. János Wimpffen, Hugus was listed as a reserve driver, as Wimpffen himself saw the “demande d’application”. The issue is that the Le Mans rules at the time stated that if a reserve driver drove the car, the driver who was replaced couldn’t get back in the car. So if any ACO officials had seen and recorded both Ed climbing into the car for either Gregory or Rindt and one them returning to the car later, the team would have been disqualified.

So what actually happened? Well, the #21 NART Ferrari 250LM won and was definitely driven by Masten Gregory and Jochen Rindt. The evidence supporting Ed Hugus’s drive seems to have been downplayed in the time following the race as no one on the NART team wanted to risk a disqualification. And to this day, the official records make no mention of him and all of the people involved have sadly passed away.

I’d like to believe that Ed did drive that car. That fifty years ago, with most of the press and officials either drunk, asleep or both, with most of the pits vacant and memories blurred by the shadowy gloom, things were overlooked perhaps by accident or out of convenience. Either way, it was the last 24 Hours of Le Mans that a Ferrari would ever win. Who drove the car to victory? That you’ll have to decide for yourself.

Image Sources: 24h-lemans.com, maranello-literature.com, stuttcars.com, elrincondecartero.blogspot.com, kwa-kwa.pl.

After 46 years, Ford returns to Le Mans. By Tracy Samilton, Jun 12, 2015.

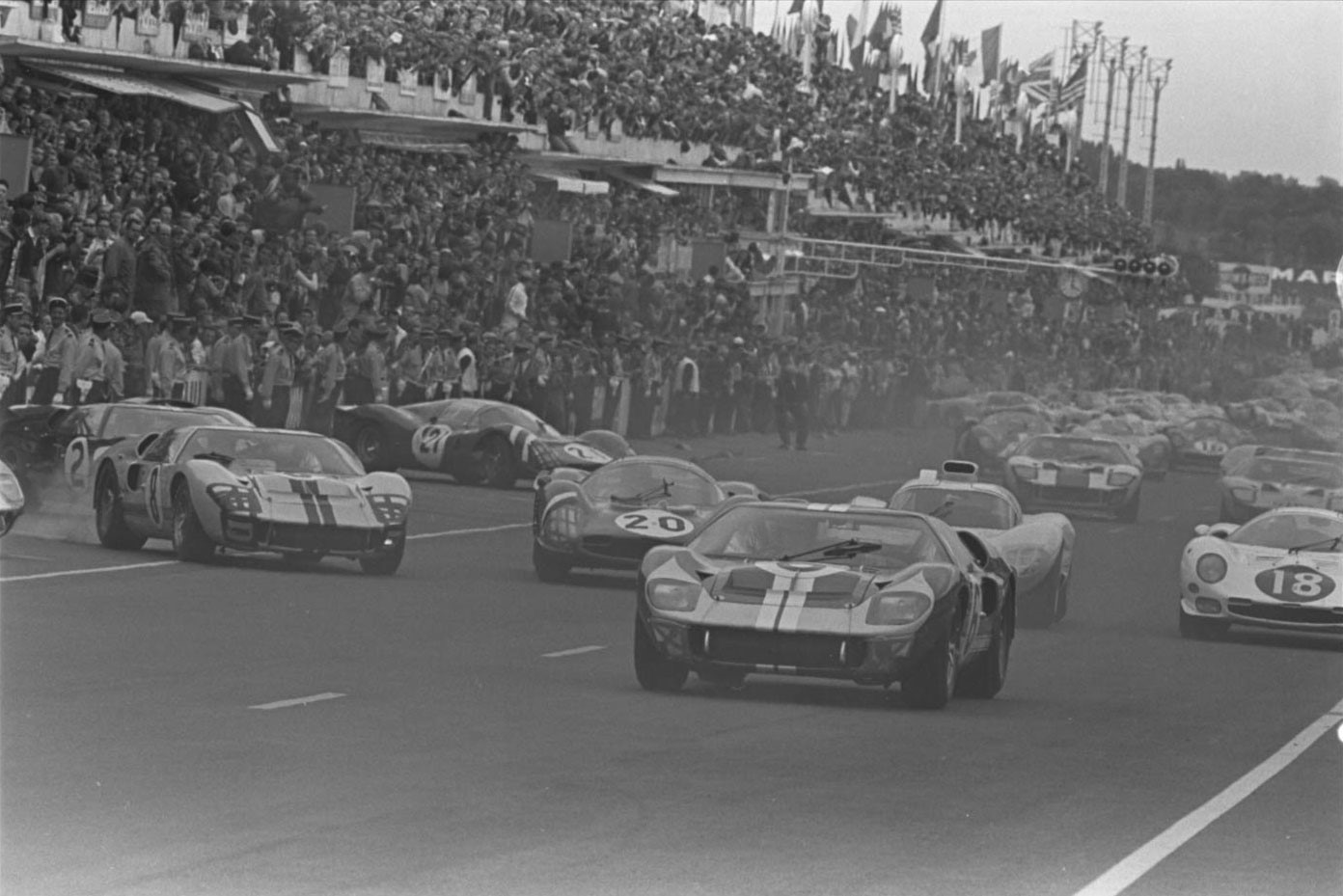

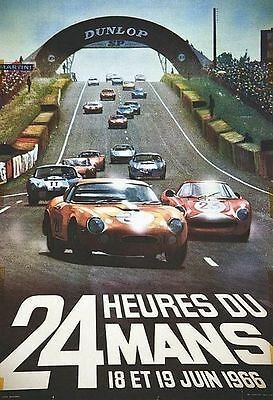

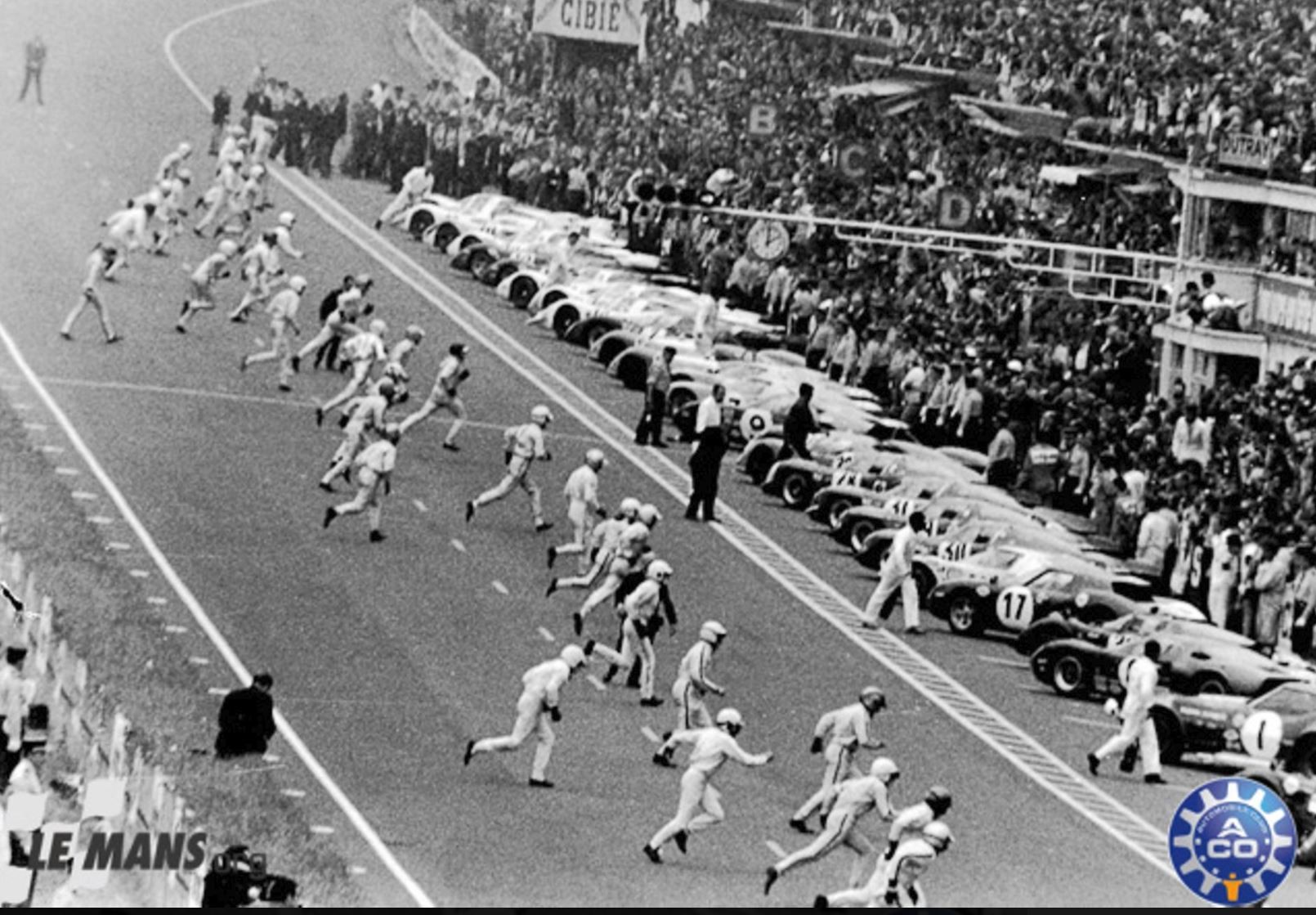

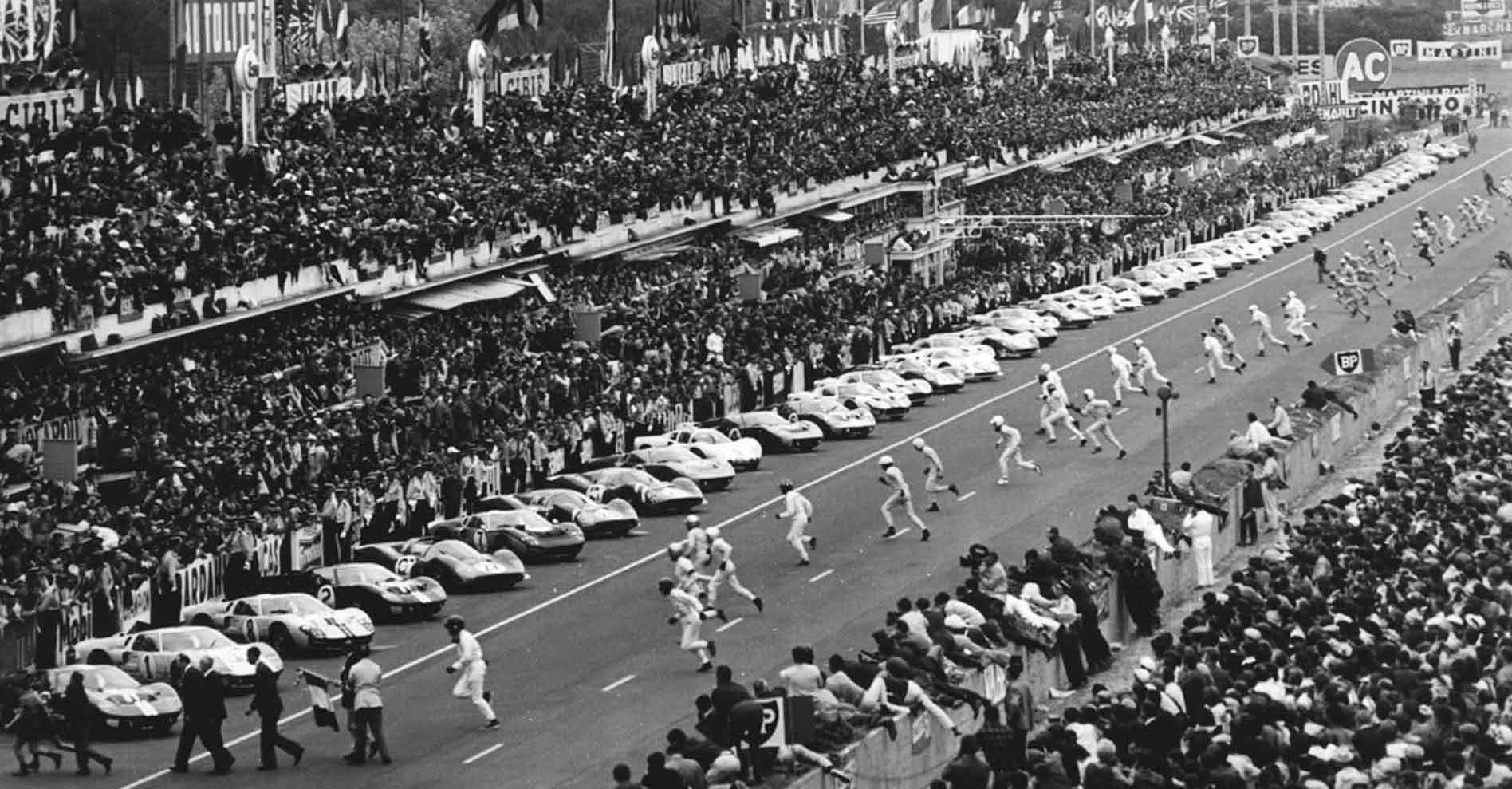

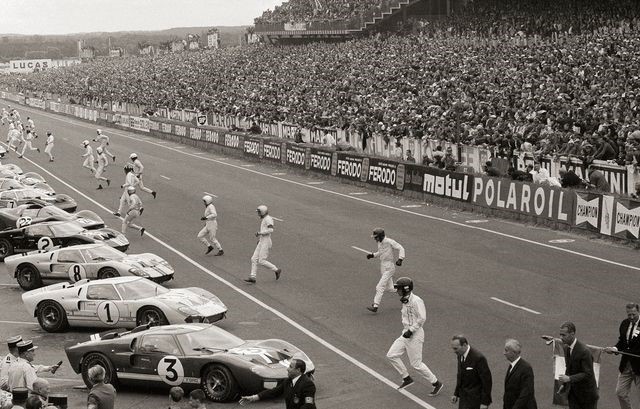

Le Mans start in 1966. Drivers had a standing start in the early days of the French race. Credit Wikipedia / public domain.

Le Mans start in 1966.

Ford Motor Company will return to Le Mans racing after a hiatus of 46 years.

Ford pays homage to Le Mans with celebration liveries.

The Dearborn automaker will enter a racing version of its new GT Supercar in the grueling endurance race.

"This vehicle, really from the very beginning, was born to race," said Ford Executive Chairman Bill Ford at a press conference held on the grounds of the famous circuit in France.

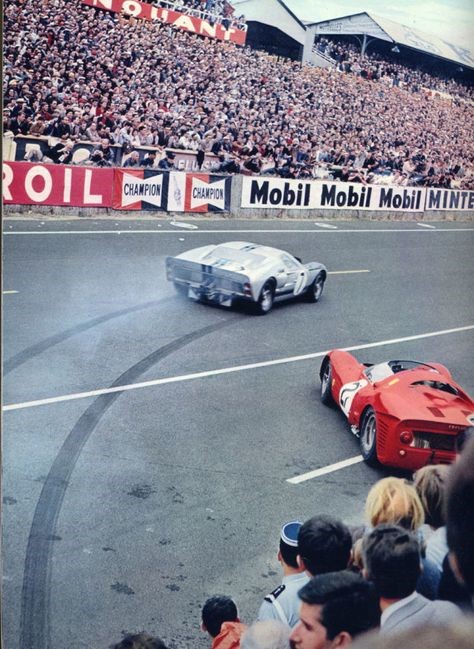

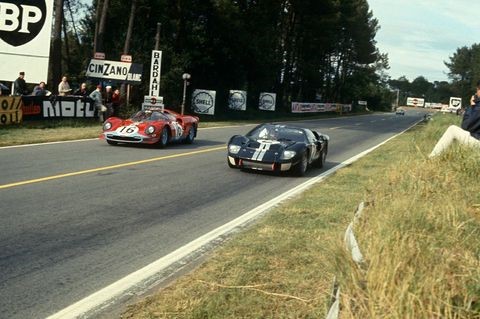

June 18, 1966. Ford and Ferrari jockey for position during the typically chaotic Le Mans start.

Ford, the great-grandson of Henry Ford, said “watching the 1966 Le Mans - when Ford cars placed first, second and third - was one of the most exciting memories he has from childhood”.

The news has implications beyond racing, according to Henry Ford III.

He's the great, great-grandson of Henry Ford.

The younger Ford says the GT uses ground-breaking technologies and materials, from extensive use of carbon fiber and aluminum to a high-performance Ecoboost engine.

"What we've learned in pulling this car together - and what we will continue to learn by racing it on racetracks like Le Mans - we can then implement across our entire vehicle lineup," Ford told Michigan Radio.

The automaker hasn't yet chosen its drivers for the 2016 Le Mans, but says applicants are lining up already.

Ford Motor Company's founder, Henry Ford (the first), was able to acquire the financial backing he needed to start the company by winning a race in 1901.

A Ferrari at 24 Hours Le Mans exhibit.

The only Ferrari to win twice at Le Mans: 1963 Ferrari 275 P set for RM Sothebys’s Monterey private sale. Posted on 16 August 2018.

A 1963 Ferrari 275 P that took first place at the 1963 and 1964 24 Hours of Le Mans will be presented on RM Sotheby’s Private Sales stand at the forthcoming Monterey auction on 22nd to 25th August. The rare 275 P, chassis n. 0816, is regarded as one of the most historically important Scuderia Ferrari sports racing cars, with this as the only Ferrari to have won the legendary 24 Hours of Le Mans twice.

Ferrari 275 P-5.

Two–time endurance champion

The 275 P saw incredible success for the Ferrari factory team. The race car took its first victory at the 1963 Le Mans, driven by Michael Parkes and Umberto Maglioli. However, 0816 was never originally scheduled to compete in 1963. Ferrari Classiche has confirmed that the original entrant – 0814 – was severely damaged in practice at the Nürburgring and was still being repaired as the race approached. Therefore, Scuderia Ferrari made the decision to send 0816 to the challenging endurance race, under 0814’s identity.

The 275 P entered two race outings in 1964. Taking victory once more at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, under Jean Guichet and Nino Vaccarella, the car also entered the 12 Hours of Sebring, driven by Michael Parkes and Umberto Maglioli.

Decades of salubrious ownership

Following its Scuderia Ferrari racing career, the Ferrari was sold to Luigi Chinetti’s famed North American Racing Team (N.A.R.T.), who campaigned the car a handful of times in the United States, including twice more at the 12 Hours of Sebring. In 1970, the 275 P was sold to renowned collector Pierre Bardinon’s world-famous Mas du Clos Collection in France, where it has remained for the last 48 years.

Seldom-seen publicly over the course of the Bardinon family’s ownership, Chassis n. 0816 is presented via RM Sotheby’s Private Sales division in highly original, never fully restored condition, retaining its matching-numbers engine, gearbox and body. The Ferrari joins a wealth of exclusive cars on RM Sotheby’s stand at Monterey, including a 1966 Ferrari 275 GTB Alloy by Scaglietti and a 1976 Lamborghini Countach LP400 ‘Periscopio’ by Bertone.

“This 275 P is without question the most historically important sports racing Ferrari campaigned by the Works team and we are tremendously honoured to offer the car for private sale on behalf of the Bardinon family. As the pinnacle of the Scuderia works cars, the 275 P offers the perfect juxtaposition to the 250 GTO on offer in our Monterey auction — which represents the pinnacle of Ferrari’s privateer GT cars. The other three 1963 Scuderia cars remain in long-held, significant private collections and this is certainly the most important of the four built, making RM Sotheby’s presentation of the 275 P truly a once-in-a-generation opportunity.” Augustin Sabatié-Garat, European Auction Manager & Car Specialist, RM Sotheby’s.

This story was written by automotive PR specialists Torque Agency Group.

The toughest rivalry in Le Mans - Ford VS Ferrari. How a cancelled deal sparked one of the biggest rivalries in racing history. Jeremy Ethan Ibrahim. Posted in “Speed Machines” 2 years ago.

The Ford GT, next to its arch nemesis, the Ferrari 330 P4.

Introduction

In the early 1960s, Henry Ford II wanted the world to know what his company was capable of in the realm of motorsport. In order to make a grand opening, they decided to compete at the most grueling, intense and competitive race ever known to man, the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Ford had big, big plans ahead of him, along with ambitious dreams to be realized ahead of him. At the time, the Europeans were dominating the racetrack, with prominent names such as Porsche, Alfa Romeo and Ferrari. Ford planned to purchase one of these marques in order to give a massive boost their racing program.

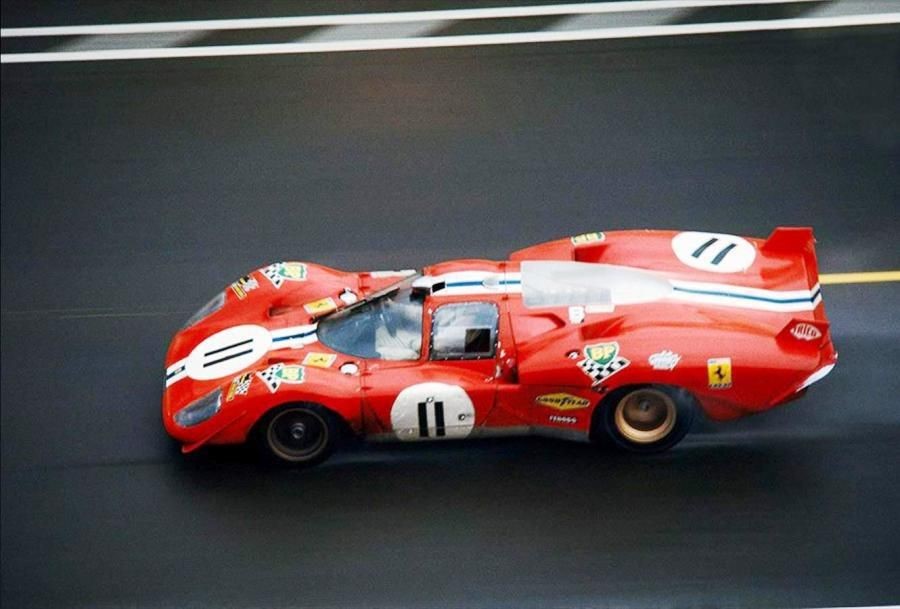

At the time, Ferrari was the prominent name at Le Mans, with their striking Ferrari 330 winning titles for them. It immediately drew the attention of the crowd every time it drove past the paddocks, as it was regarded as one of the most beautiful cars of all time. Ford decided to buy Ferrari because of their prominence and their success at Le Mans. Ferrari's CEO, Enzo Ferrari had also shared keen interest in the deal. Henry Ford II traveled to Italy and spent around several million dollars conducting an audit of Ferrari.

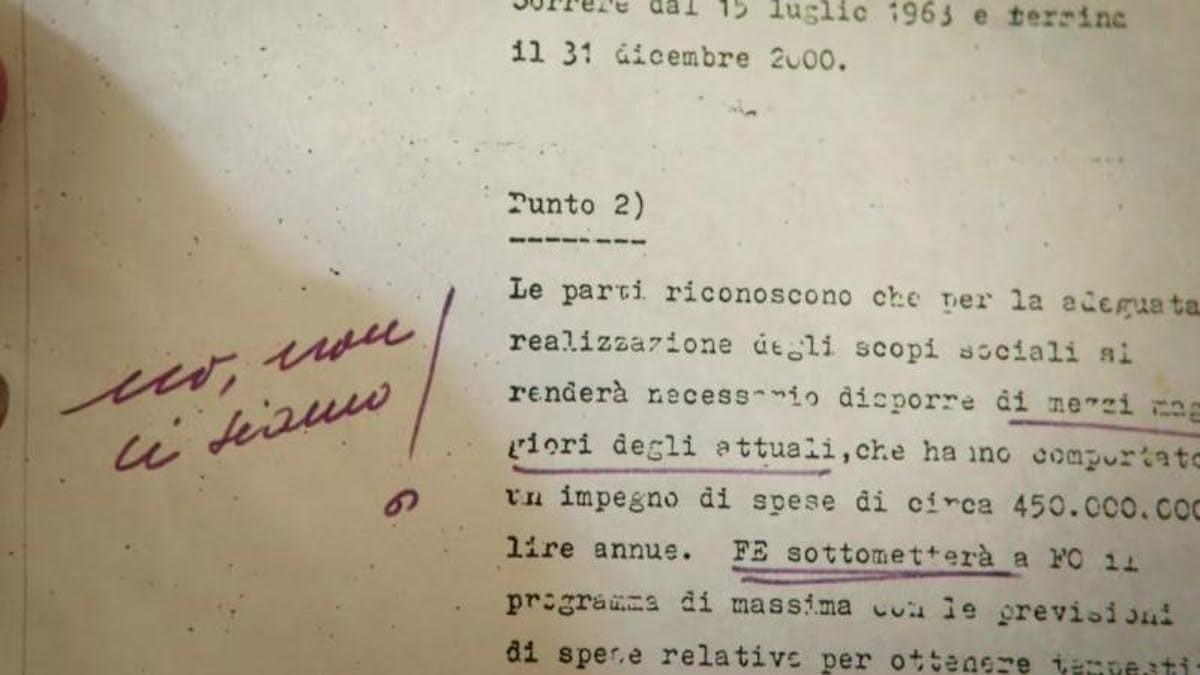

Enzo Ferrari's strong response to the deal written on the contract.

When Enzo Ferrari read through the contract, he noticed a small detail that he did not expect which would affect his company in a big way. The contract stated that Ford will take over both Ferrari's racing and automotive division. Enzo Ferrari did not like it one bit. He underlined them with purple ink and next to it, wrote "unacceptable" before throwing a string of insults at Ford executives that Ferrari's secretary who was with him at the time, Franco Gozzi, described it as "'words you would not find in any dictionary."

Ferrari, Gozzi and other Ferrari executives stormed out of the conference room, leaving Henry Ford II and his team baffled and confused. After that failed deal, Ford tried to negotiate with other teams such as Lotus, Lola and Cooper. All three companies were concluded as not eligible to boost Ford's presence in motorsport. Because no options were available, Ford returned to the US empty handed.

Henry Ford II was fuming with anger. He gathered Ford's top executives into a conference room and said this sentence that would become the beginning of the one of the most intense, tough and biggest rivalries in the history of Le Mans. Henry Ford II had given a very clear and direct order to Ford's chief engineer, Don Frey, with one goal in mind.

"Go to Le Mans and beat Ferrari's ass."

Ferrari's Success

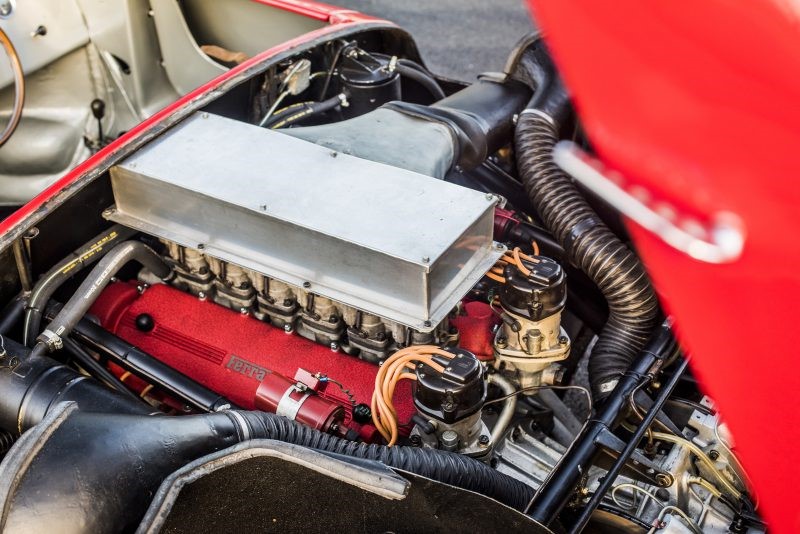

The successful Ferrari 250 P racer.

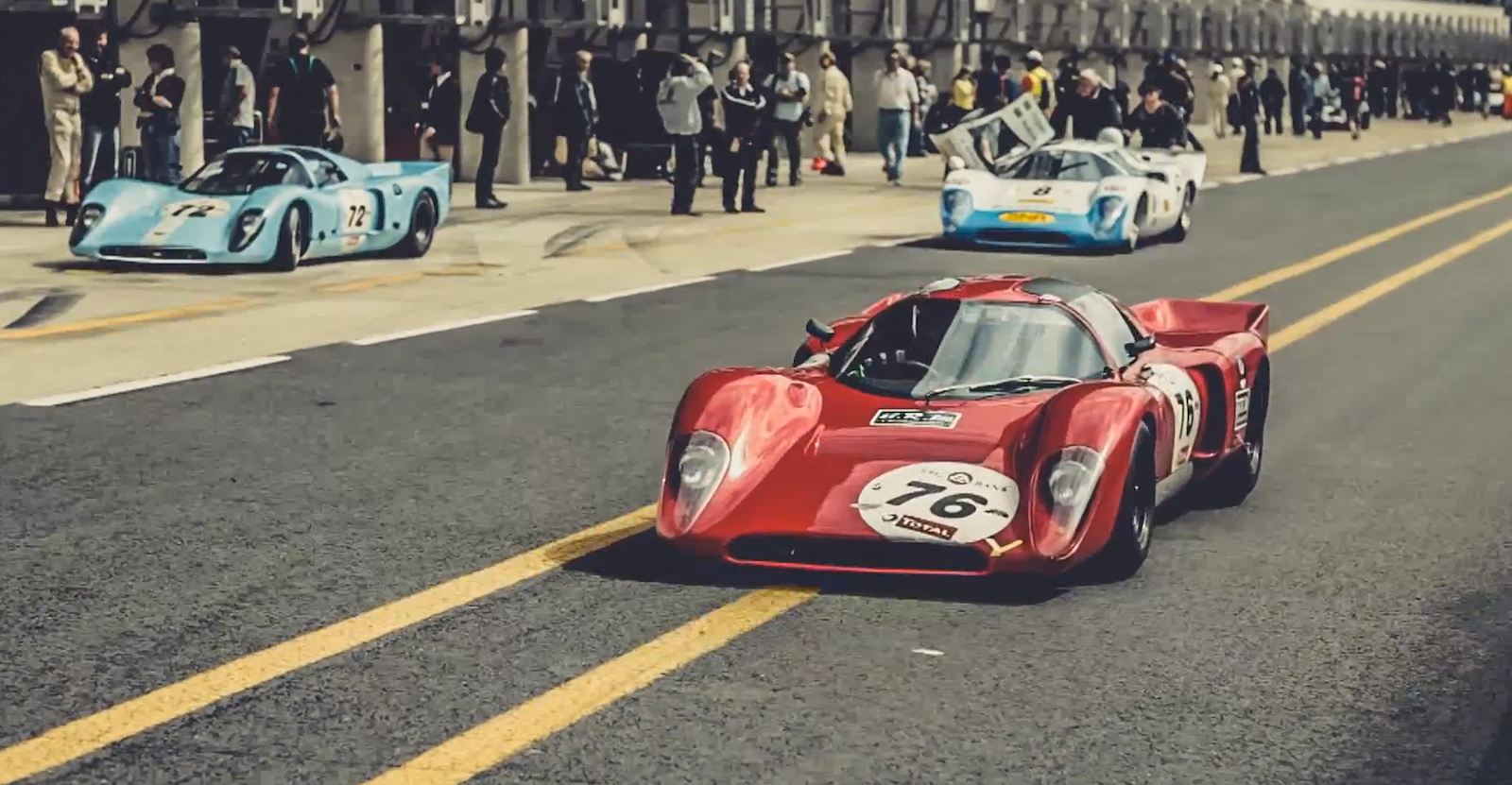

Ferrari was the biggest name in Le Mans at the time, with their newest race car at the time, the Ferrari 330, coming from a long line of a series of cars Ferrari made for one specific purpose, endurance racing. Ferrari's P series were dominant on the racetrack, from the 250 P to all the way to the 275 P. They all shared the same championship winning DNA from the World Sports Car Championship in 1963, all the way to Le Mans.

1966 Le Mans 24 Hour, Ludovico Scarfiotti in a Ferrari 330 P3.

Ferrari's 330 P3 was the newest and the shiniest star of the brand, a powerful, V12 powered, beautifully designed, aerodynamic and innovative racing prototype, implementing technologies such as fuel injection and a custom made gearbox in to maintain its ongoing dominance at Le Mans. It had loads and loads of potential and was just waiting to be unleashed onto the track. Ferrari's P series had secured Ferrari six wins by the end of 1963, the most wins achieved by an auto manufacturer at the time.

However, Ferrari's glory would not last long, as the Americans were cooking up something that is really worthy of a competitor to the 330 P3.

Development of Ford's Ferrari killer

The Lola Mark 6.

Meanwhile across the pond, Ford were still developing their first car to race at Le Mans. Luckily, Ford had an existing partner which had experience racing at Le Mans, Lola Racing, as they had sourced their engines from Ford. Their car, the Lola Mark 6, was known to be one of the most advanced racing cars of all time and had proven what it could do in 1963. Unfortunately, they were marked as DNF, when the car broke down at the Mulsanne Straight due to low gearing and low revs.

Lola's boss Eric Broadley had agreed to a personal contribution to help Ford build their Ferrari 330 killer. He would collaborate with Ford for a year, with the sale of two Lola Mark 6 cars for Ford's research and development. Ford had also hired Aston Martin's ex-team manager John Wyer. Chief engineer Roy Lunn was also put in charge, as he was the designer of the mid-engined Mustang I concept car. He was the only engineer in the workforce to have experience with a mid-engined car.

The team moved to London and had established a new company to develop their Ferrari 330 killer, called Ford Advanced Vehicles, overseen by John Wyer. Now based in England, they were closer to their rival, Ferrari.

The Ford GT40

An early prototype of the Ford GT.

On the first of April 1964, in England, Ford's Ferrari killer was unveiled to the world. Known as the Ford GT40, the GT in its name stands for Grand Touring and the number 40 stands for the overall height of the car, 40 inches. The car was powered by the 4.7-liter Fairlane engine with a Colotti transaxle, a similar powertrain to the cars it was based on, the Lola GT and the Lotus 29. Other modifications included Gurney-Weslake cyliner heads and an increase of 0.2-liters in displacement. Ford was truly proud of what they had achieved.

Earlier cars were named either the Ford GT, or the Ford GT40. The first 12 prototype vehicles were built soon after, with serial numbers GT-101 to GT-112. It might not have been designed as beautifully as its competitor, the 330 P3, but it was definitly designed to win against Ferrari at Le Mans, in revenge of the deal that Enzo had cancelled four years before. All it had to do is prove itself on the track to earn Ford's seal of approval.

Problems and Doubt

The Ford GT40 during the 1000 km of Nurburgring.

The GT40 was plagued with many, many technical problems. In May 164, during the 1000 kilometers of Nurburgring endurance race, the car jumped to second place during the early stages of the race. It looked like all the effort Ford's development team had put into had finally paid off. Unfortunately, it had experienced a suspension failure, forcing the car to be pulled off the track early.

The GT40 entered its first race at Le Mans on the same year, which is also the car's first time competing against its arch nemesis and sole rival, Ferrari. Of course, the crowds were gunning for Ferrari, as they had won many races before with their powerful, beautiful and elegant looking P series cars. No one was going to gun for a boxy, truck-engine powered Ford who had just joined their first race at Le Mans.

1964 had become a huge embarrassment to Ford, retiring all three cars after just two laps around the circuit. Meanwhile, Ferrari had taken the title for championship at Le Mans with their Ferrari 275P. Henry Ford II's dream of destroying Ferrari had crumbled in front of his own eyes. Doubts were increasing whether the project would be a success, as Ford had invested a lot of money into the project. However, there is a silver lining to every dark cloud, as one man would give the entire project a new light and his name was Caroll Shelby.

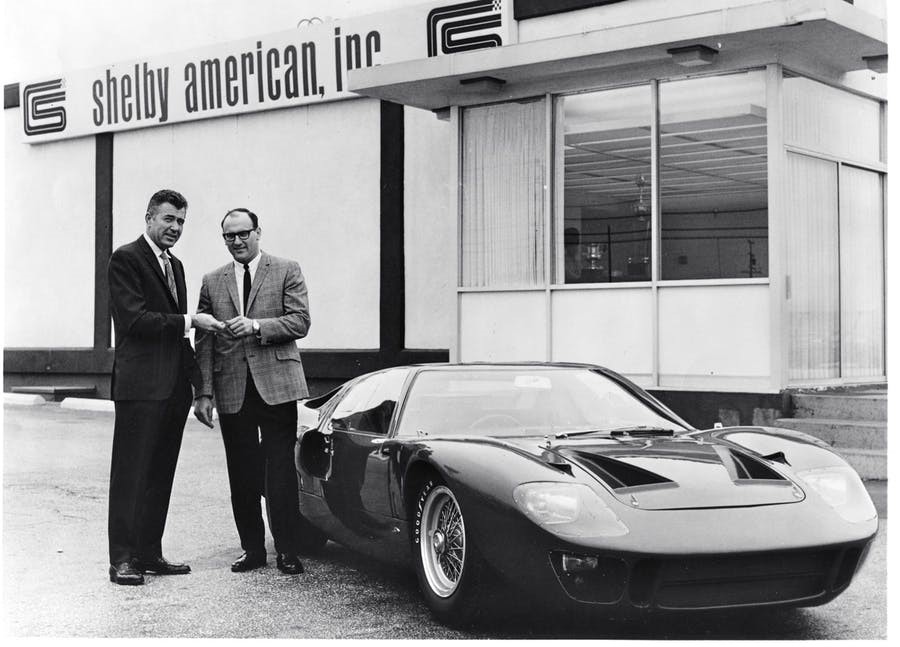

Under Caroll Shelby's Leadership

Caroll Shelby and the Ford GT40 Mark II.

After those abysmal results at Le Mans, American motorsport and auto performance legend Caroll Shelby took over. Caroll Shelby was the Ford GT40's saving grace, as he was known to be an innovator in the auto industry. After what he had done with Britain's AC Motors, along with having his brainchild, the Shelby Daytona Coupe win in its class at the same time the Fords broke down behind, Ford knew that they could only win through him.

Shelby had uncovered many, many problems with the GT40. Due to really bad aerodynamics, the car was losing at least 75 horsepower. If it sounds like a lot of horsepower lost today, well back then it was monumental. Shelby had also complained that the cars were poorly maintained, along with being way under powered compared to competition. If Ford wanted to beat Ferrari, they have got the right man to do it.

The Ford team went back to the drawing board and redesigned the car's inlets and exhausts to reduce the car's already massive drag coefficient down to around 0.37. Caroll Shelby had performed his magic on the car's V8 engine, increasing power from 350 horsepower to around 450 horsepower. Ford was back in the game, more powerful than ever, thanks to Caroll Shelby. They now had an even higher chance of beating Ferrari once and for all.

Ford's Comeback

The Ford GT40 at Daytona.

Ford made a comeback to endurance racing one more time, this time under the watchful eye of Caroll Shelby, during the Daytona 2000 in February of 1965. With their new GT40, now bigger, faster, stronger and more aerodynamic, it was more ready to take on the best giants could offer than ever. Ford had prepped their best drivers, Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby, to race for two thousand kilometers around Daytona non-stop, in their pursuit of beating their arch nemesis, Ferrari.

Ford had won the Daytona 2000, which was a huge turnaround for the program as previous results have been appalling. One month later, Ken Miles, along with Kiwi racing driver Bruce McLaren, secured second place overall, just shy of the race winning Chaparral in the sports class. Despite that, Ford had won first place in the prototype class. However, the rest of the season was a disappointment, with Ferrari winning once more in the year 1965 at Le Mans.

The Ferrari 330 P4

The beautiful Ferrari 330 P4.

Meanwhile, Ferrari continued their dominance over Le Mans, adding two more wins to their trophy rack after beating Ford twice in 1964 and 1965. Their biggest rival seemed to not catch up with them, after losing two races straight with disastrous results and unlucky circumstances. It looked like their rival did not know how to build an endurance racing car after witnessing their embarrassing breakdowns. However, Ferrari knew not to underestimate their opponents and developed an entirely new car to maintain the throne at Le Mans.

In 1966, Ferrari had developed the 330 P4, a heavy step above the car it was based on, the P3. Enzo Ferrari had developed an entirely new V12 engine for the car, with cylinder heads modeled after those of Italian Grand Prix winning Formula One race cars. The P4, along with its predecessor, the P3, had proven itself at the 1000 kilometers of Monza, crossing the finish line in first place. Ferrari had a competitive edge over the competition thanks to their new car.

The 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans

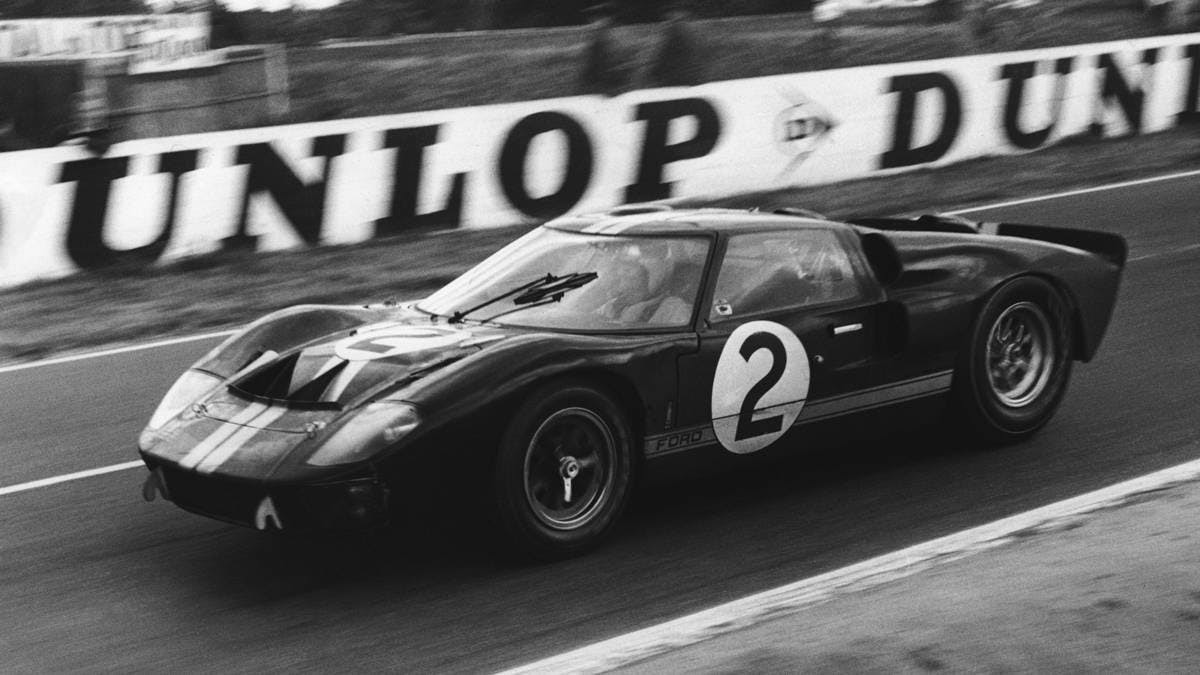

The Ford GT40's iconic 1-2-3 photo finish.

During the 1966 World Endurance Championship, Ford and Ferrari's competition grew tougher and tougher by the hours. Ford had won the first race on the calendar, the 24 hours of Daytona with a photo finish. Ford had also made another photo finish during the 1966 12 hours of Sebring, also finishing first, second and third. Ferrari was also no slouch during the championship either, winning the 1000 kilometers of Monza, along with Targa Florio, the Nurburgring and Spa.

1966 24 Hours of Le Mans. Photo by Henry Ford.

However, the big race had arrived, the 24 hours of Le Mans, the race that Ford had dreamt of beating Ferrari in. Ford's biggest chance of redemption had come, after years of humiliation by Ferrari, along with their biggest opportunity to put their name on the realm of racing, letting the world know that Ford is truly capable of motorsport. Henry Ford II's dreams of dethroning Ferrari had become more close to reality than ever, after seeing what their newest car could do on the racetrack, under the wing of American racing legend Caroll Shelby, with Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon behind the wheel ...

At exactly 12:00 PM, the race was on. Ford and Ferrari raced towards victory with a fierce competition between them, with the leading car fluctuating between either the Ford GT40, or the Ferrari 330 P4. At the end of the first hour, however, Ford had dominated the race, leading in positions 1-2-3 by a massive 24 seconds. During nightfall, Ferrari took the lead, with Ford fiercely catching up behind. However, due to massive rainfall, two Ferrari 330s that were behind had spun and crashed, leaving only the leading 330 left ...

After sunrise, Ferrari had maintained lead position throughout the race. One of the Ford GT40s had crashed as a result of slipping due to spilled petrol. The leading Ferrari kept on leading the 24 Hours of Le Mans until one moment that would turn the tables on the entire race. The leading 330 P3 had burst a tire, making the entire Ferrari team marked as DNF. That gave Ford such a big opportunity to win. Finally, after trailing behind the Ferrari for so long, the GT40 had overtaken it and lead the race till the end.

The Ford GT40 had won a photo finish at Le Mans, with first, second and third place. Ford had beaten Ferrari in the biggest way possible, as they took the top three positions at Le Mans, while none of the Ferraris had even finished the race. All that hard work Ford's racing development team had put into the project had finally paid off. Most importantly, Ford had finally realized their dream of beating Ferrari ...

After 1966

The Number 2 Ford GT, the winner of the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans.

After 1966, Ford continued to beat Ferrari in not only Le Mans but throughout the entire International Prototype Sports Cars from 1966 to 1968. They kept on winning in races such as Daytona, Sebring, and Spa, winning the champion manufacturer title three times. Ford continued to maintain its title as champion and dominated Le Mans from 1966 to 1969, winning four times in the process.

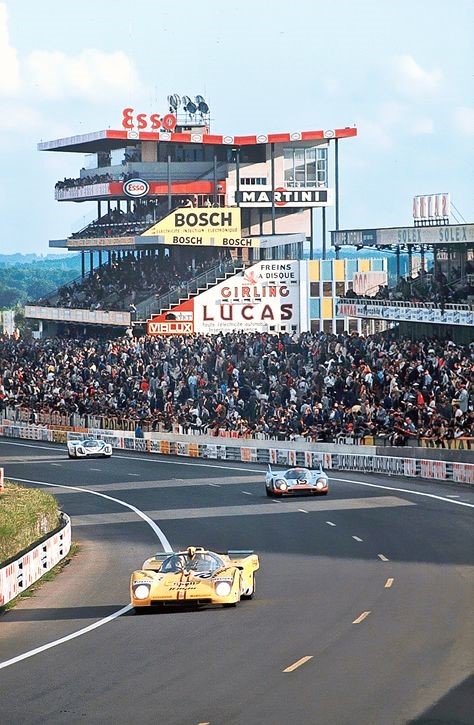

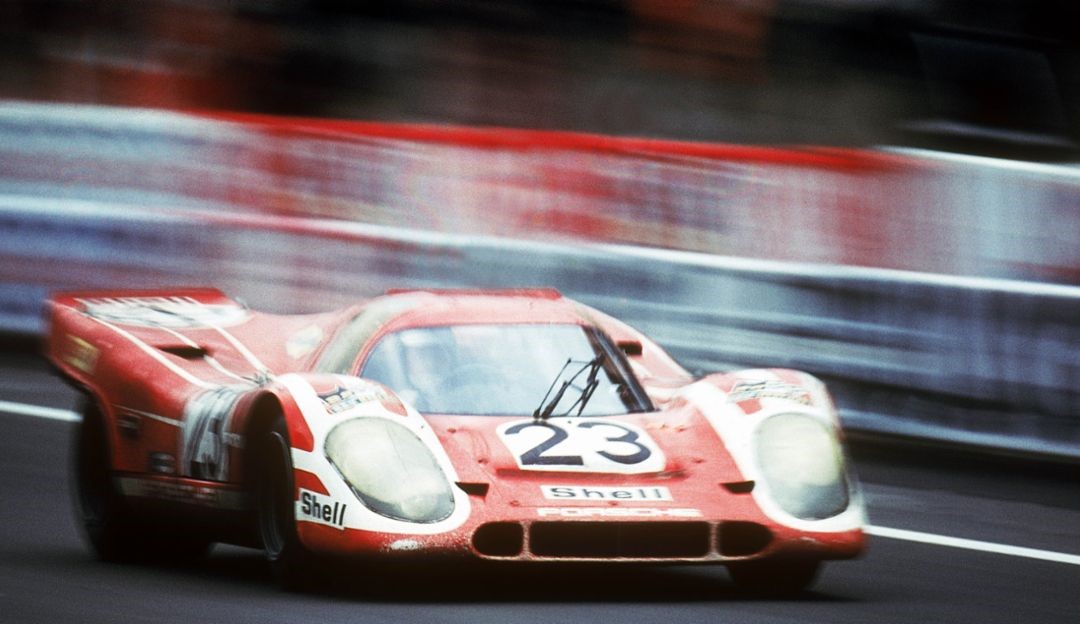

1971 Porsche 917, Siffert-Bell. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

It wasn't until the year 1970 when Ford was finally beaten by Porsche at Le Mans.

Le Mans. The Ferrari 512 of Jose María Juncadella followed by a Porsche 917.

Ferrari had not won a single race at Le Mans since 1966, soon withdrawing from the competition in 1973 so they can solely focus on winning in Formula 1. The last time they had won a title at the World Sports Car Championship was in 1972, winning 10 out of 11 races.

Ford and Ferrari Today

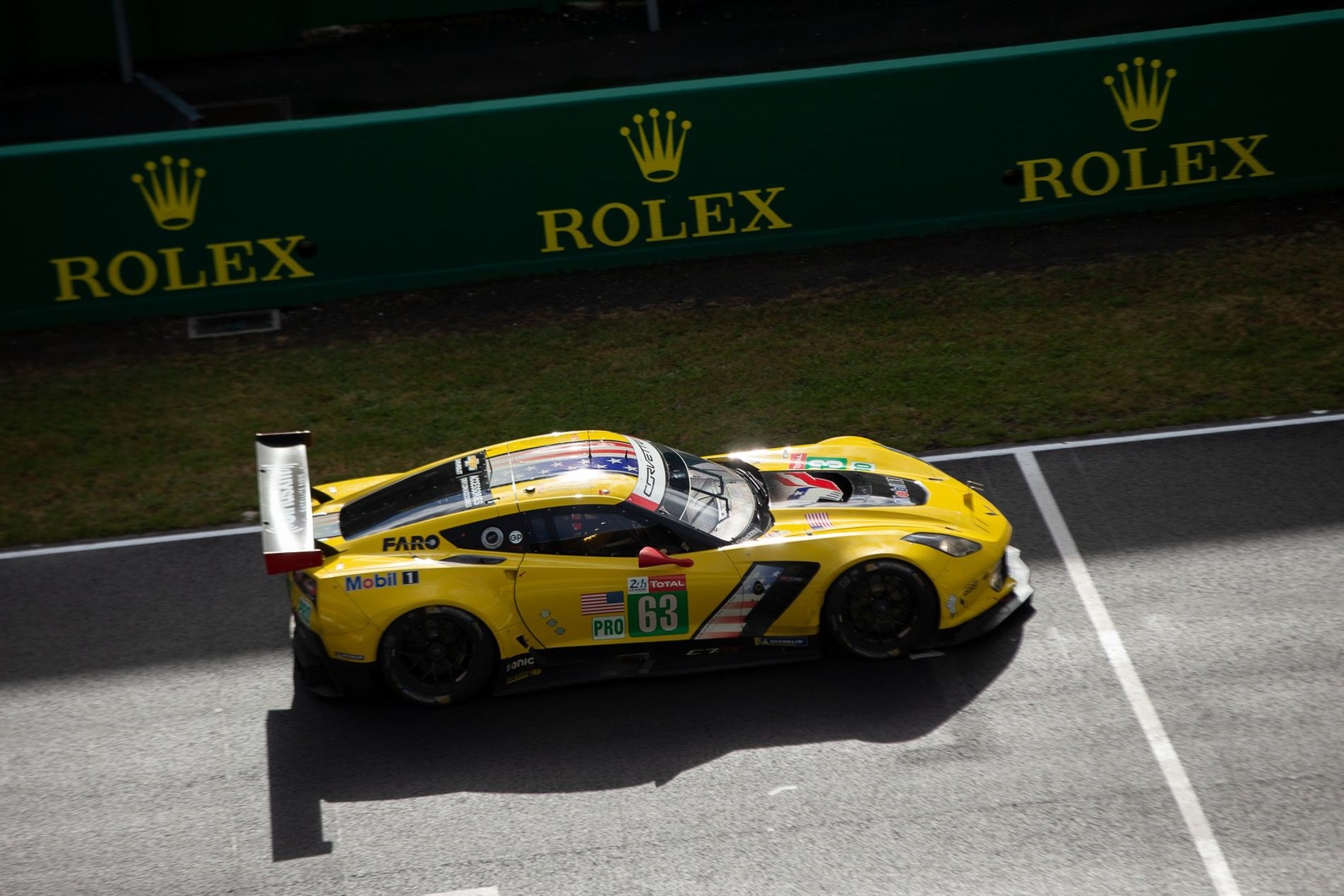

The Ford GTLM race car ahead of the 488 LM GTE at the 2016 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The Ford vs Ferrari rivalry continued to be remembered throughout time, with several books, documentaries and even a movie produced based on it. The book "Go Like Hell", written by A.J. Baime, along with the documentary film directed by Nate Adams called "The 24 Hour War" were based on it. A movie is currently under production called "Ford vs Ferrari", starring Tracy Letts as Henry Ford II, Matt Damon as Caroll Shelby and Remo Girone as Enzo Ferrari, expected to make its debut mid-2019.

In 2005, Ford had released the Ford GT, an homage to the original Ford GT40 that had won Le Mans. The car's design was reminiscent of the original, still powered by Ford V8, only supercharged. The car would accelerate from 0-100 kph in under 3.8 seconds, reaching a top speed of 328 kph, or 205 mph. Around 4,000 of them were built and sold worldwide. In 2015, Ford had released a second generation Ford GT, marking 50 years since the GT had won at Le Mans. Now powered by a twin-turbo Ecoboost V6 engine making 647 horsepower, it went from 0-100 kph in 2.8 seconds, reaching a top speed of 345 kph, or 216 mph.

Both Ferrari and Ford still race at Le Mans, this time racing in the GTLM Pro class. Ferrari with their 488 LM GTE, along with Ford with their GTLM race car. Ever since Ford's return to endurance racing in 2016, 50 years after their first victory against Ferrari in 1966, the rivalry lives on.

Motorsport TV.

The 24-Hours of Le Mans follow a simple rule: the car that covers the greatest distance in 24 hours is the winner. It is the ultimate endurance test for man and machine. Each year, more than 250,000 enthusiastic spectators flock to 24 Hours of Le Mans. Former Le Mans champion Yannick Dalmas reveals why people are so fascinated by the motorsports Super Bowl. 22 May 2019.

Originally developed to test the durability of materials and showcase innovative techniques, 24-hour races such as Le Mans or the Nürburgring Nordschleife are now highlights in the motorsports calendar.

To be a winner here, you need more than just a powerful car and superior driver. According to racing legend Yannick Dalmas, “to get to the top, drivers, mechanics and crew have to start working together closely months before the race. Racing situations have to be simulated in the factory and the entire team needs to develop a really good feeling.” In 1999, Dalmas drove the legendary BMW V12 LMR with 635 hp of the winning team. “Right from the start, you need to have the same objective: victory!”

4,967.991 km in 24 hours

So does this mean Yannick Dalmas drove non-stop at full speed for 24 hours? No, even the best-trained athlete could not manage that. In a 24-hour race a team is always made up of several drivers.

Back then, Dalmas together with two teammates, the Italian driver Pierluigi Martini and the German Joachim Winkelhock, covered an incredible 4,967.991 kilometres; including pit stops, this is an average speed of 207 km/h. “We had a great strategy, a reliable car and three drivers whose concentration was maximum at all times,” Dalmas recalls.

“In Le Mans you have to be humble”! Yannick Dalmas

Circuit de la Sarthe: 85 % at full speed

Circuit de la Sarthe.

When it comes to concentration, the Circuit de la Sarthe pushes drivers to the limit. “Le Mans is incredible! You have to be humble,” says Dalmas. The 13.626-kilometre route includes nine kilometres on public roads and 4.5 kilometres of asphalt track on the Bugatti circuit.

And this is almost always at full throttle! For 85% of the route, the drivers accelerate fully. “On every lap, you take over 300 km/h four or five times. During the day and during the night. And this in extreme heavy traffic that forces you to constantly judge and find the best racing line,” Dalmas explains. To give you an idea of what this means: in 2018 there were 60 cars in total on the circuit.

“The slightest mistake and you lose the car”. Yannick Dalmas

Spectacular key points

The six-kilometre Mulsanne Straight is particularly important – this almost straight stretch of road is interrupted by two chicanes. The highest speed ever driven here is 405 km/h. “At such high speeds, choosing the right moment to brake is the real challenge.”

But the Le Mans circuit is not only known for its high-speed stretches. “All drivers are very excited at the Porsche curves and the Ford chicanes,” Dalmas admits. About driving through these technically complex sections at high speed, Dalmas adds, "the slightest mistake and you lose the car. I like those spots very much."

Everything you need to know about the 24 Hours of Le Mans race. By Rich Ceppos. June 6, 2019.

Breaking down the historic Le Mans 24-hour endurance-racing classic, a brutal test of driver and machine.

Getty Images.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans is auto racing's Boston Marathon, a brutal test of endurance where competitors race stunningly fast cars for 24 straight hours at speeds that can exceed 200 mph on the fastest section of the incredibly long 8.5-mile Circuit de la Sarthe road course. The race is a punishing test that pushes driver and machine to their limits — and sometimes beyond.

History, hellish events and high speeds are the key ingredients that make the 24 Hours of Le Mans the world's greatest sports-car race. It is both famous and infamous for the triumphs and tragedies that have occurred there. Started in 1923 as a showcase for car manufacturers to prove the durability of their vehicles in competition, it has evolved into a high-speed chess match among top professional racing teams where strategy, teamwork and great driving skill are as important as a car's reliability and technological edge.

The race is staged annually in mid-June by the French sanctioning organization Automobile Club de l'Ouest. Four classes of cars compete side by side, which can make the racing confusing, but a team of knowledgeable TV commentators keeps the action sorted out for you. Le Mans is part of the FIA World Endurance Championship, which includes long-distance races in nine countries. Through the years, automobile manufacturers including Porsche, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, Ford, Toyota, Ferrari, Aston Martin, Jaguar and Chevrolet have invested tens of millions in their race teams with the hope of taking the winner's laurels and basking in the marketing glory a win confers.

The top two classes, LMP1 and LMP2, are made up of purpose-built race cars that can cost millions and are supported by large crews of engineers and technicians. The cars look like four-wheeled fighter jets and employ advanced aerodynamics to suck them to the track, which enables astounding speed in the corners. The current rules encourage teams to race gasoline-electric hybrids and last year's winning car, Toyota's TS050 LMP1, utilized that technology to make a claimed 986 horsepower. LMP2 cars are similar but less complex, are powered by conventional gasoline engines and are not quite as fast as the LMP1s.

About two-thirds of the field is composed of the other two classes competing in the race, the GT, or grand touring, cars: GTE-Pro and GTE-Am. These classes are based on highly modified versions of production-line sports cars with recognizable names and shapes from makers such as Ferrari, Porsche, Chevrolet, Ford and Audi. They have about 500 horsepower and the infighting is fierce as these cars battle for position and class wins while trying to stay out of the way of the flying prototypes. As their names imply, GTE-Pro is for full-time professional drivers and manufacturer teams, while GTE-Am is for amateur drivers and private teams. All teams must rotate three drivers through the car during the race, with no one driver behind the wheel for more than a total of 14 hours. Driver changes happen in conjunction with pit stops for fuel and fresh tires.

History runs deep at the Circuit de la Sarthe, the name of the 8.5-mile temporary course that roars to life in the sleepy French countryside every June. The original race was run entirely on local roads, but for reasons of safety it now combines sections of public road knitted together with stretches of purpose-built racetrack. The famous Mulsanne straight, part of the original track, is still in use. One of the world's longest racing straightaways at 3.7 miles, it's actually a public road, French route départementale D338, except for those few days each year when it is closed down for the 24-hour event. Another tradition: the race cars undergo one of their several technical inspections in the Le Mans town square, where they can be viewed up close by the general public.

1967 Le Mans. Credit Cyndee Gardner.

Le Mans 1967, Ferrari 330 P4.

Le Mans 24 Hours race. Ludovico Scarfiotti with Mike Parkes, Ferrari 330 P4 Coupe #0858 n. 21, finished the race in second position on 11 June 1967.

And the spraying of champagne after a race win? That was started at Le Mans as well, by American Dan Gurney after winning the 1967 race.

Racing dynasties have flourished and faded across the 86 years the event has run—it was canceled for 10 years during World War II and in 1936 because of strikes across France. Bentley and Alfa Romeo both made their early reputations with four consecutive wins each in the 1930s. Jaguar and Ferrari dominated the 1950s and 1960s. Henry Ford II's personal rivalry with Enzo Ferrari resulted in his company deciding to build the Ford GT40, which defeated Ferrari in four straight Le Mans races from 1966 through 1969. Porsche was the dominant force in the 1980s and Audi prototypes notched an amazing 13 wins between 2000 and 2014.

Along with racing triumphs, the race has been the scene of tragedies.

The worst of them occurred during the 1955 event, when a Mercedes 300SLR race car crashed at high speed on the front straight, launching flaming parts into the crowd and killing 83 spectators. It remains the worst auto-racing accident in history. As a result, automobile racing was temporarily banned in several European countries. Major safety improvements were made to the Circuit de la Sarthe in the wake of the 1955 event; numerous safety upgrades for both spectators and the racers have been implemented in the decades since. Race cars were already reaching speeds in excess of 225 mph on the Mulsanne by the early 1970s, so a pair of tight zigzag chicanes were added partway down the straight to bring speeds down. Despite the changes, the fastest of today's race cars will still top 200 mph on the Mulsanne. And that can still mean trouble, as when driver Peter Dumbreck's Mercedes race car flipped into the trees in 1999; he somehow escaped without major injury.

Late night driven at Le Mans in the early 70's. François Cevert in the #14 Matra 670B.

François Cevert.

Beginner’s guide to the Le Mans 24 Hour. By Glenn Butler, 14 Jun 2019 Car News.

It’s the most coveted endurance road race in the world and car companies spend hundreds of millions of dollars trying to win it, yet the cars bear no resemblance to actual road cars. So why is the Le Mans 24 Hour race such a big deal?

This weekend France hosts the 87th running of the world’s most famous 24-hour race, the 24 Heures du Mans. This is the road race that makes our esteemed Bathurst 1000 look like a quick afternoon sprint.

Porsche garage in Le Mans.

Car companies like Toyota, Audi, Porsche, BMW and others have spent millions of dollars building wild prototype cars and assembling huge teams of up to 300 people as they strive to win this round-the-clock race of attrition between man and machine.

And yet, it’s probably most famous with Australians for being the race in which Mark Webber spectacularly flipped not one but two Mercedes-Benz race cars, back in 1999.

The 24 Heures du Mans is run every June at the Circuit de la Sarthe, just outside of Le Mans in northern France. Each year more than 250,000 spectators descend on the track to watch the world’s best drivers compete for victory – drivers from Formula One and IndyCar racing wheel to wheel with Hollywood stars and celebrities.

It’s that kind of event.

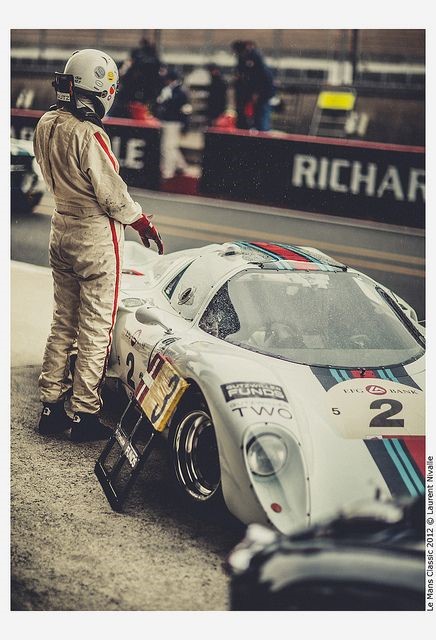

Foto di Laurent Nivalle.

Vintage Lamborghini at Le Mans. Photography by Laurent Nivalle.

It is the world’s oldest active sports car race. It’s been the site of many titanic battles between carmakers over the years and in modern times has seen a string of dominations, none more impressive than Audi’s 13 wins from 15 attempts between 2000 and 2014.

This year, WhichCar has embedded with the Toyota WEC Team (World Endurance Racing) as they attempt to go back to back. It’s been a long, hard road for Toyota which is now competing in its eighth WEC season, but the Japanese brand is an almost unbackable favourite to take out this year’s race.

In fact, many believe the only thing that can beat Toyota is Toyota.

Here are a few interesting facts about the Le Mans 24 Hour race.

Beer is cheaper than water in many campgrounds (we checked)

Luigi Chinetti and Peter Michael Thomson won the 1949 race, but it was Chinetti who did all but 20 minutes behind the wheel

The last Australian to win was David Brabham in 2009, driving a Peugeot

His brother Geoff Brabham won in 1993, also driving a Peugeot

Two other Australians have won Le Mans: Vern Schuppan in 1983 and Bernard Rubin back in 1928

Peter Brock and Larry Perkins had a go in 1984, in a Porsche 956 and were doing okay until the car crashed out with six hours left to run. Rumour has it Perkins was 4sec a lap quicker than Brock

Porsche.

New Zealander Earl Bamber won the premier LMP1 category with Porsche in 2015 and 2017

Aussie whizz kid Matt Campbell won the GTE AM race in 2018 with a Porsche 911 RSR

Le Mans still holds the dubious record of the world’s deadliest motorsport incident, when a Mercedes flipped into the crowd in 1955 and caught fire, killing 84 people and injuring another 120.

The last driver to die at Le Mans was Dane Allan Simonsen, in 2013. The Bathurst 12-Hour qualifying trophy is named after him

Today, the Le Mans 24 Hour has four main car categories ranging from wild Le Mans Prototypes (LMP) machines to more conventional road cars.

There are two LMP categories – LMP1 and LMP2 – for purpose-built race cars that bear absolutely no resemblance to road cars.

LMP1 cars are all-wheel drive, weigh around 870 kg (including driver) and can produce up to 745kW (1000hp) of power from their petrol or hybrid engines. The teams are free to evolve or modify their chassis and bodywork to achieve the highest performance, which saw some crazy body styles in the 1990s and 2000s. Today, the rules stipulate that the cockpit must be enclosed. Oh and they have limits on how much fuel they can burn and electricity they can expend per hour. They are the Formula 1 cars of the endurance world.

LMP2 cars look just as wild, but are slightly less frightening. Teams have four different chassis/bodies to choose from, each weighing around 930 kg and are not allowed to mess with them in any way or shape. The engine, too, is a regulated component - a 4.2-litre Gibson (Nissan) V8 producing around 450 kW. Oh and the cars are only rear wheel drive. Put that all together and LMP2 cars are around 10 seconds a lap slower that the brutal LMP1 cars at Le Mans.

The other two categories are GT Endurance Pro and GT Endurance AM. These cars have a lot in common with conventional road cars such as the Porsche 911, Chevrolet Corvette, Ford GT, Ferrari 488 and Aston Martin Vantage.

But the differences can be substantial. For example, the road-going Porsche 911 is called a rear-engine car because the engine hangs out over the rear axle. But the 911 GTE car has the engine practically inside the cabin behind the driver – a change Porsche made to make the car more competitive.

Generally, the biggest difference between GTE Pro and GTE AM is that GTE AM teams must have at least one amateur driver (AM = amateur). GTE AM cars must also be at least a year old to keep the cost of competing down.

The Toyota TS050

Toyota first entered its current Le Mans Prototype in the 2016 event. This state of the art carbon fibre race car is built for speed and downforce. It’s powered by a high tech petrol-electric drivetrain which combines a potent twin-turbo 2.4-litre V6 petrol engine with two electric motors to deliver a combined output of 1,000hp.

Add that to the LMP1’s standard all-wheel drive system and you get a car that New Zealand's Le Mans winner and former F1 driver Brendan Hartley says “accelerates out of corners harder than any machine I’ve ever driven”.

Circuit de la Sarthe

For years Australians considered Bathurst to be the world’s second longest racetrack after the Nurburgring, even though the Le Mans track is a whopping 13.6km in length, which more than doubles Bathurst.

Perhaps it’s because the Le Mans track is not a permanent track – two-thirds of its length consists of real-world roads. But then Bathurst is not a permanent track either.

The Circuit de la Sarthe used to have a 6 km main straight – Mulsanne Straight – on which cars would hit more than 400km/h, before two chicanes were put in back in 1990, effectively splitting it into three shorter straights.

Now, the fastest cars will be lucky to top 350km/h. Last year’s race-winning Toyota TS050 peaked at 336km/h, but still managed to average 251km/h per lap.

44 Pictures of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, from film stars to tragic crashes. By Natasha Ishak. Published November 10, 2019.

Discover the complete history of France's 24 Hours of Le Mans, an endurance race that has been the world's most iconic grand prix since its founding.

There's no competition in the world like the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world's most illustrious and oldest active automobile endurance racing competition, where the best drivers compete against each other for 24 hours straight.

The Le Mans race has evolved a lot over its almost century-old history, setting the stage for world records, groundbreaking engineering and even terrible human tragedy. But no matter what, the essence of the race — a show of innovation and endurance — remains the same.

History of the 24 Hours of Le Mans race

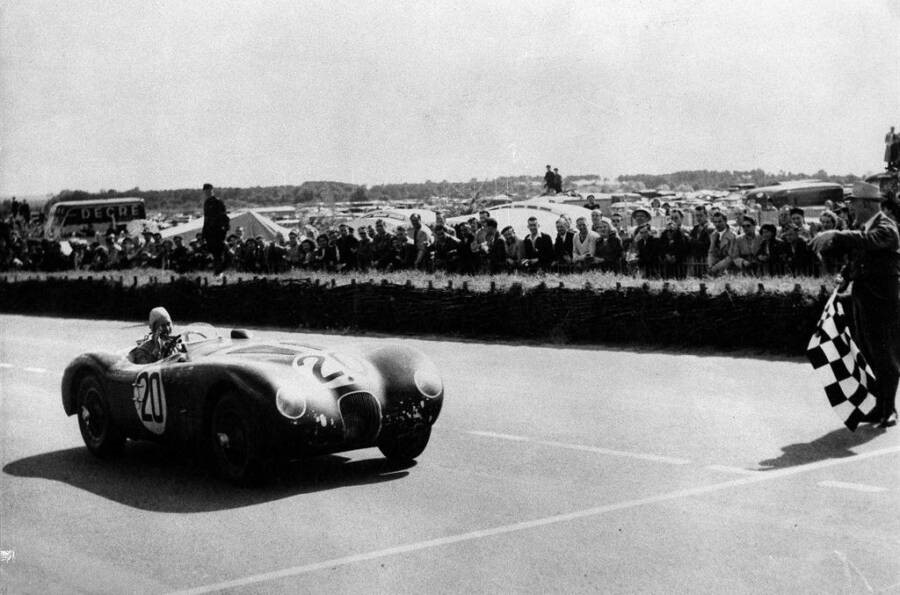

Driver Peter Whitehead finished first place at the 1951 24 Hours of Le Mans race, aboard the Jaguar C-type car. Wikimedia Commons.

As the world entered the 1920s, a new era of economic prosperity took over North America and Europe, sparking the label "Roaring Twenties." Innovative industry powered economic growth and a taste for automobiles began to emerge, especially among the French.

Watching the Grand Prix motor racing was a popular past-time, but European car fans soon yearned for more difficult challenges to test the cars and their racers.

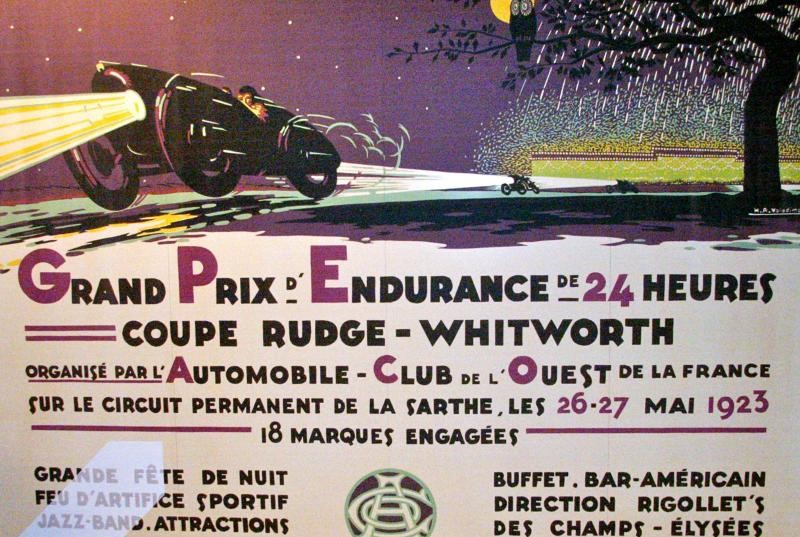

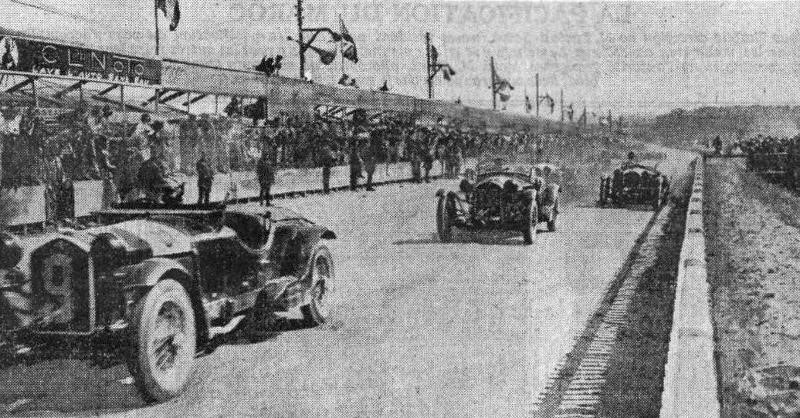

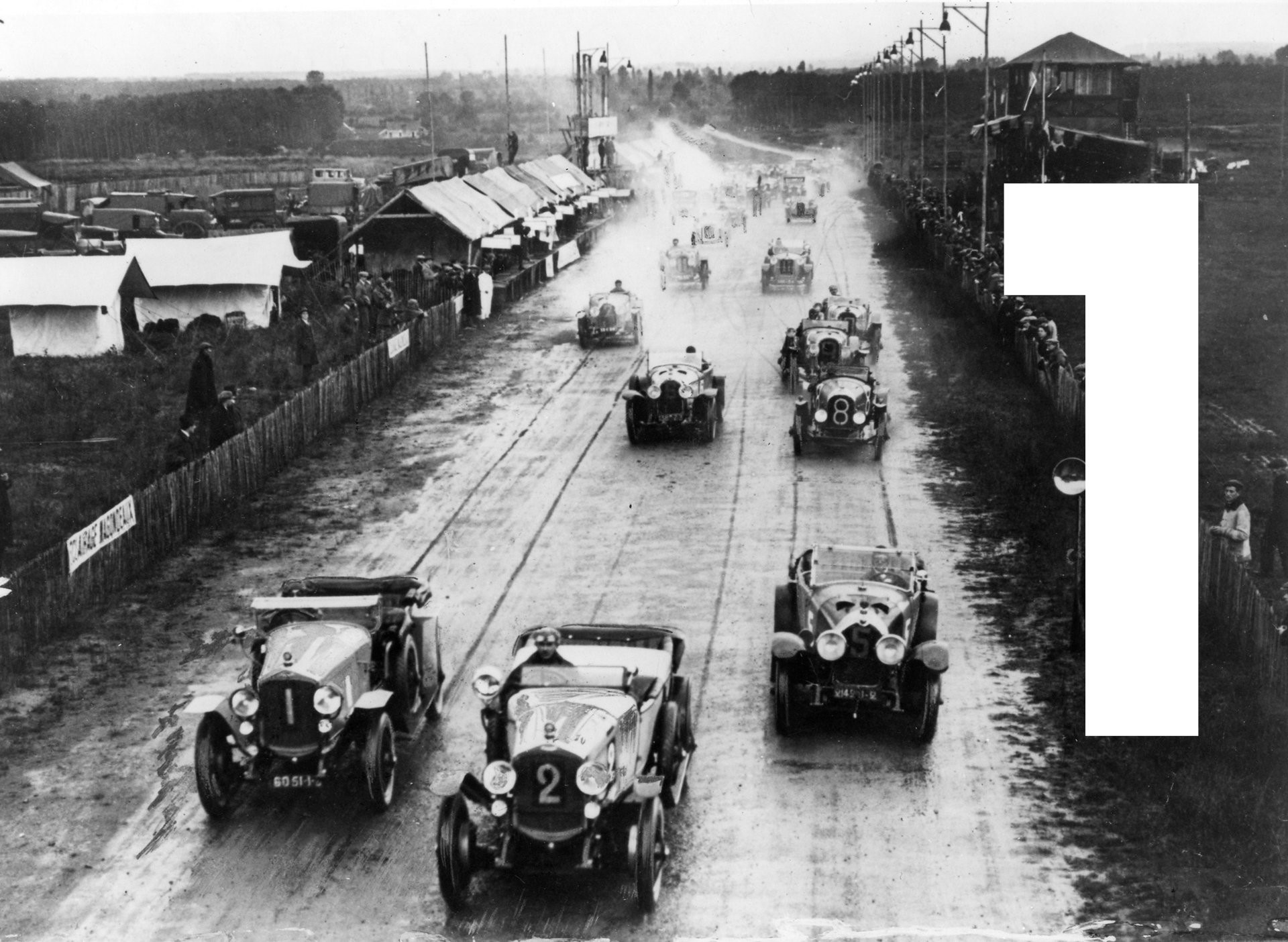

In 1923, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) organized the first-ever 24 Hours of Le Mans (or “24 Heures du Mans”) race which ran a 10.7-mile course through the public streets of the Northwestern French village of Le Mans — a challenge never before seen in Grand Prix sports racing. The race track of Le Mans was dubbed Circuit de la Sarthe after the river that flows through the village.

The first Le Mans race was held between May 26 and 27, 1923 and rules were simple: whoever clocked the most miles during the 24-hour period won. The high-stakes endurance-testing competition quickly became a yearly race and a prestigious affair for automobile companies to show off their latest innovations.

"The race is legendary, it fascinated me and there I was about to take the start, as had drivers I considered heroes ... The circuit was unlike any other. You approached such high speeds in the Mulsanne Straight before the chicanes. For a driver it was exhilarating." Ford driver Mario Andretti on his 1966 race at Le Mans.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans pushed car makers to design better cars that were faster and more durable, enough to leave the rest of the competitors in the dust. Claiming the title of Le Mans was a coveted honor for car brands since it gave their products uncontested credibility and often translated to higher car sales.

The earlier years of the 24 Hours of Le Mans competition were dominated by the French. Wikimedia Commons.

Winner of the first 24 Hours of Le Mans race was the French driving team of Andre Lagache and Rene Leonard, who competed against 33 other teams inside their 3-liter Chenard and Walcker vehicle. The pair traveled a total of 1,372.94 miles to win the inaugural 24-hour race.

After the Second World War broke out, the competition was forced to stop its activities and did so for ten years. The once full arenas and race circuits were destroyed by the travesties of the war.

After the war, the Le Mans race resumed and attracted even more interest from the public than before. It grew so popular that four years after it started up again it had evolved to become part of the World Sportscar Championship, a collection of the most significant sportscar events in the world to which the 24-hour car race became part and parcel.

Notable years of Le Mans

After the end of the Second World War, Le Mans broke its hiatus to renewed interest from sport racing fans and major car makers. National Motor Museum / Heritage Images/Getty Images.

By the 1950s, the 24 Hours of Le Mans race began attracting major car companies like Ferrari, Mercedes-Benz, Aston Martin and Jaguar who competed to place multiple cars in the popular race, effectively spending millions of dollars to perfect their teams and take home the crown.

Le Mans was a hotbed for famous personalities, including A-list Hollywood actors. Some had been life-long fans while others took to the wheel after portraying drivers on film, celebrities like Paul Newman and James Garner.

The race also attracted other influential figures, such as Mark Thatcher, the son of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. It seems even the rich and famous were not immune to the addictive euphoria sparked by the illustrious Le Mans race.

"You see it with the Oscars. People vote, they say him or her. In this, you either cross the finish line first and it's either him or her," Paul Newman explained of his love for the sport. Newman competed in the 1979 Le Mans in a Porsche 935 and continued to race later on in his 70s.

Henry Ford II poses with Ford drivers Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon, after their historic victory at the 1966 Le Mans. Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Some of the Le Mans races throughout the years bore unforgettable marks in the competition's storied history. The 1953 race, for example, was the year when the now-legendary Ferrari racing team won at Le Mans for the first time.

In 1966, American automobile maker Ford made its historic run at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Ford's American engine was considered an underdog of the race, particularly against the revving powers of the Italian Ferrari. The famous rivalry between Enzo Ferrari and Henry Ford II heightened the stakes that year, making the competition all the more exciting for sports racing fans.

Ford took home victory in 1966 — the first overall win for the Ford GT40 and the first win for an American car manufacturer at Le Mans. Unbeknownst to the public, it would be the first of many more wins by the Ford racing team with the car maker winning the title for four straight years after that.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans competition, like any other extreme endurance sport, has seen its fair share of gruesome accidents. At Le Mans 1955, 83 race fans were killed after debris from the highly-flammable magnesium-alloy bodied Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR went flying into the bleachers after it crashed on the track.

The grisly accident was reported in the June 27, 1955, issue of “LIFE Magazine” in terrible detail: “hitting the Healey, the Mercedes took off like a rocket, struck the embankment beside the track, hurtled end over end and then disintegrated over the crowd. The hood decapitated tightly jammed spectators like a guillotine. The engine and front axle cut a swath like an artillery barrage. And the car's magnesium body burst into flames like a torch, burning others to death”.

Mercedes driver Pierre Bouillin, racing under the name Pierre Levegh, was instantly killed while 180 more spectators were injured. The 1955 Le Mans disaster remains the most horrifying tragedy to have occurred in motorsports history. The severity of the accident led to an immediate temporary ban on sports racing across Europe until safety standards of the race could be improved.

24 Hours of Le Mans today

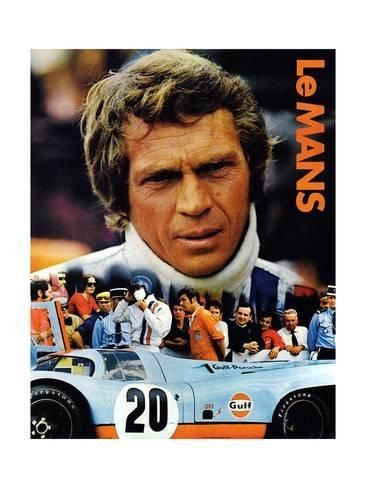

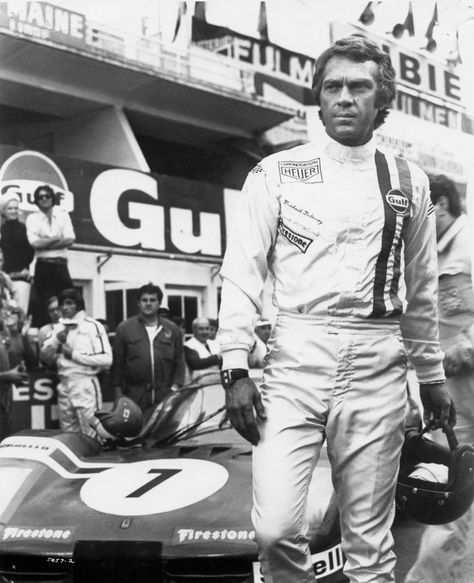

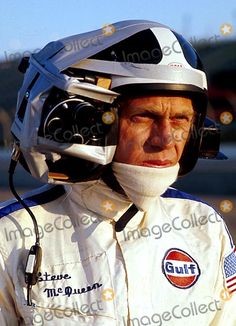

The blood, sweat and tears it takes for racing teams to conquer the challenging terrain of the Le Mans race has been heavily captured on film. Actor Steve McQueen, who later competed in sports racing off screen -- though never at Le Mans himself -- portrayed a tenacious driver competing at Le Mans in the 1971 film “Le Mans”.

The legendary rivalry between Enzo Ferrari and Henry Ford II — the grandson of Henry Ford who is known as "Hank the Deuce" — has also been the subject of fascination for filmmakers.

The 2016 documentary “The 24 Hour War” centered on the feud between Ferrari and Ford and its unfolding behind-the-scenes at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The film received high approval ratings from both critics and regular audiences.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans is still the most elite sports racing competition in the world. United Autosports / Flickr.

The same rivalry is also portrayed in “Ford vs Ferrari” starring actors Christian Bale and Matt Damon. In the dramatized version of the rivalry, Bale and Damon play the two figures crucial to Ford's upset win against Ferrari in 1966 — British driver Ken Miles (Bale) and American car designer Carroll Shelby (Damon), who were said to be the masterminds behind Ford's revolutionary race car, the Ford GT40.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans still runs today as part of the competitive FIA World Endurance Championship — a cross-track, cross-continental competition which takes place over the course of several months. The Le Mans race is now the last leg or "Super Finale" of the extravagant car racing competition, pitting drivers from around the world against each other in the ultimate test of endurance.

1966 24 Hours of Le Mans start.

"Le Mans 1966": cult movie about the most famous race ever. By Vincenzo Borgomeo. November 13, 2019.

Enzo Ferrari's slap in the face of Ford, the rematch at the 24 hours of Le Mans and a legendary story. Told in the cinema.

Let's say it straight away: no "spoiler alert" because if you don't know that Ford beat Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966, the new film "Le Mans '66 - The great challenge" makes no sense. The one told in the film on November 14th is in fact a fictional reconstruction of the legendary duel between Ford and Ferrari. Born from an affront (one of many ...) that the Drake made in his life. In this case to the Detroit giant when he blocked the sale of Ferrari to Ford in the final phase of the negotiation. But let's go step by step.

It all began on May 23, 1960, when Ferrari was transformed into a joint stock company, passing from the official name (which lasted since October 16, 1957) of Auto Costruzioni Ferrari, to that of Società Esercizio Fabbriche Automobili e Corse - SEFAC Spa. The big step was taken to bring fresh money into the coffers of the company, always in need of large sums to be able to invest in development and research, two fundamental sectors for success in racing. Ferrari had opposed this strange revolution but, after hours of counseling with his administrators, he had to yield.

At the end of the 1960s, however, in order to continue to compete at the highest levels in F1 and to have the necessary know-how in the areas of design and development of production GT, it was necessary to have an automotive giant behind. The decision was serious because to do this it was necessary to sell a substantial package of shares. Which - among other things - would also have made it possible to collect money and further relaunch the company.

Ferrari didn’t like all this. Imagine. For him it was not just about selling a piece of his company, but a piece of his life.

Ford, for his part, - after years of absence from competitions - wanted to re-enter the world of racing through the front door: to acquire 50% of the shares of Ferrari. For the US giant it would have been a "bang", but also for Ferrari: Ford ensured not only a large amount of capital, but also infinite technological support. A new world was opening up in the search for sophisticated materials, in the study of unprecedented technical solutions and in the design of ever faster cars.

The deal seemed to be made. But it was precisely in the final stages that the Commendatore turned everything upside down: Ford also claimed to "govern" the racing department, taking away total autonomy from the founder of the brand. With a quick change of course, the Maranello-based manufacturer therefore signed a similar agreement with Fiat, which however left Enzo Ferrari absolute command of racing and of the company.

At Ford's headquarters, they went on a rampage: the board of directors was about to leave for Modena (no possibility of moving Ferrari, who hated traveling) and the news had just arrived that Ferrari no longer wanted to sell. Indeed, that Ferrari had already sold to Fiat.

There was an extraordinary meeting of the company's top management and right there it was decided to have an official Ford car racing at the famous 24 Hours of Le Mans, discarding the idea of competing in Formula One (where, moreover, Ford was already present with the 8 cylinder V-engines) because the category of endurance racing seemed more useful for promoting normal production cars.

Then began a no-holds-barred battle between Ford and Ferrari. Which the film tells only in part. Yes, because before the 1966 triumph Ford had to swallow several toads. When in 1964 the Ford project took shape, baptized "GT40", directed by Eric Broadley, coming from Lola and John Wyer, already at Aston-Martin, it was a bit of a disaster: Ford wasn't as refined as Ferrari when it came to racing cars. It was lacking in aerodynamics and racing setups.

So it relied on the recipe of those years that was used for American "muscle cars": a huge engine and that's it. But if it worked on American roads (without curves) for the various Mustangs and Corvettes, it turned out to be a real disaster on the track. The GT40 did not hold the road not even if you kicked it. And at high speeds it "floated", as drivers say, that is it tended to raise its nose and lose grip with the front wheels. Plus, the mighty Ford V8 crumbled, as if nothing were, the gearbox.

So the first Ford-Ferrari match ended with the usual Ferrari excessive power that dominated with its 275P, an almost classic car as it continued the long "P series" (started with the 250 P of the previous year). As usual, the abbreviation referred to the unit displacement and the letter P meant prototype. The total displacement of the 12-cylinder V was therefore 3285.72 cc, with a maximum power of 320 hp.

Then, in 1965, Enzo Ferrari understands that Ford is serious and launches the 275 P2 for Le Mans. That is the first evolution of the P-category Sports. The car joins the 330 P2 which has a smaller displacement: a 12V of 3300 cc with 270 HP and is not intended for gentlemen drivers, but only for the official drivers who had the thankless task to beat the competition. Which they managed to do, however, taking the 275 P2 even to first place in Monza with Parkes and Guichet in front of the larger and more powerful 330 P2 driven by Surtees and Scarfiotti. But Ferrari at Le Mans suffered from the same problems as Ford: the 1965 duel ended with the breakdown of all the official Ferraris and Fords. However, the victory went to the NART Ferrari (Luigi Chinetti's private team) and to his 250 LM.

In short, Ferrari seemed unbeatable but the giant Ford, with infinite economic resources, did not give up. It continued the "all engine" policy but refined aerodynamics and set-ups, giving life to the second edition by proposing the GT40 Mk II, a completely new car, powered by a gigantic V8 7000 with almost 500 horsepower. Ferrari sent on the track the 330P3, which had a smaller V12 4000 of around 420 hp. And, in order not to risk, the Maranello firm entrusted the 365P2 model to various private teams: 4.4 liters for almost 400 HP. But there was nothing to be done against the monstrous power of the GT40 MKII which beat Ferrari's competition with the New Zealand duo Chris Amon / Bruce McLaren, thanks also to the Goodyear tires designed specifically for the race, beating the great rival Firestone, at the time of the so-called tire war.

Then Ford dominated in the next four editions, even if the Maranello factory took several revenges on other tracks and in other competitions.

In short, movie stuff. And it is no coincidence that, before the film "Le Mans '66 - The great challenge", there were in 1970 "Le Mans, Shortcut to hell" (directed by Richard Kean, with Maurizio Bonuglia and Edwige Fenech) and in 1971 "Le Mans" (directed by Lee H. Katzin, with Steve McQueen).

Now it's up to Matt Damon and Christian Bale, both Oscar winners, to talk about this spectacular challenge. With the certainty that the "good stories" never die. And they are meant to be handed down indefinitely. Just like with legends. Because - you know - some races are pure legend ...

Le Mans start in 1966. Getty Images.

The feud that created America's greatest race car. The true story behind 'Ford vs Ferrari' and the 1966 Le Mans. By Ezra Dyer. November 15, 2019.

It all started with a business deal gone bad. In 1963, Henry Ford II, "the Deuce," decided he wanted Ford Motor Company to go racing. The only problem: Ford didn't have a sports car in its portfolio.

The quickest way to acquire a sports car, the Deuce thought, was to buy Ferrari, then a race car company that only sold street-legal machines to fund its track exploits.

Ford sent an envoy to Modena, Italy, to hash out a deal with Enzo Ferrari. The Americans offered $10 million, but as the negotiations neared their conclusion, Ferrari balked at a clause in the contract that said Ford would control the budget (and thus the decisions) for his race team. Ferrari, known otherwise as “Il Commendatore,” couldn’t stomach the surrender of autonomy, so he bailed, sending Henry Ford II a message the Deuce didn’t often hear: there was something his money couldn’t buy.

In lieu of the sale, Ford decided to direct his company’s cash and engineering toward petty revenge. He decreed Ford would start its own race team, with the singular goal of beating Ferrari in the world’s most prestigious race, the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

“These two guys were larger than life,” says A.J. Baime, author of “Go like hell: Ford, Ferrari, and their battle for speed and glory at Le Mans”. “Here you have arguably the most famous and powerful CEO in America, Henry Ford II, up against Enzo Ferrari — the most narcissistic man to walk the earth, but deservedly so, because he was a genius. You couldn’t write it better.”

The clash of these titanic egos would propel Ford to design America’s greatest race car: the GT40. An unstable engineering mashup of California hot-rod ethos and high-speed NASCAR expertise, the GT40 failed to finish Le Mans in 1964 and 1965, but bold testing innovations and a never-before-seen brake strategy had them primed for 1966. Weeks before the start at Le Mans, Henry Ford II handed race program boss Leo Beebe a handwritten note: “you better win.”

The 1966 Superperformance GT40 Mark II. Hayden Stinebaugh.

The 1966 GT40 Mark II is more comfortable than you might expect. Designed for long-distance driving, the seat is soft and ventilated. Forward visibility is excellent. Somehow there’s plenty of interior room, considering the tiny exterior dimensions. If Le Mans circa 1966 amounted to a frantic 3,000-mile road trip, this seems like the car you’d want to do it in. But the moment you fire up the mid-mounted 427-cubic-inch V-8, you’re reminded this is a race car, capable of modern race-car speed — more than 200 mph — in 1960s analog form. No power steering. No power brakes. No electronic safety systems. A hundred miles per hour in third gear feels like you’re in a sidecar strapped to the Space Shuttle and you’re not even halfway to top speed. The guys who ran these things down the Mulsanne Straight at 210 mph, at night, on 1966-spec tires, after driving for four hours straight, must’ve been brave. Or crazy. Or a heady mixture of both.

This car, a Superformance GT40 Mark II, is a “continuation car,” a street-legal re-creation of the winning 1966 Le Mans car. In fact, this particular GT40 Mk II was used in the new film “Ford vs Ferrari”, based on the legendary story. It’s magnificent. And, like both the 2005–2006 Ford GT and the current GT model released in 2017, the Superformance owes its existence to that long-ago battle of egos between two stubborn industrialists. The 1966 GT40 Mk II feels like such a fully realized race machine, it’s hard to believe it started out as a half-baked effort that was not only uncompetitive, but dangerous.

It might seem like a foregone conclusion that Ford, an international car-building colossus at the height of its powers in the 1960s, could crush a small independent company like Ferrari on the race track, but that was far from a given. As countless car companies have learned, money doesn’t directly translate to victory.

“They spent a lot of money, but that was no guarantee you’d win a race,” says Preston Lerner, author of “Ford GT: how Ford silenced the critics, humbled Ferrari and conquered Le Mans”. “[Ford] also had to bring in the right people to win. They had to have the mechanics, the race organization people, the drivers. It could’ve been a glorious failure.”

And in 1964 and 1965, it was. Ford’s new race car was fast, but they couldn’t figure out how to make it last for 24 hours. Gearboxes broke. Head gaskets blew. The aerodynamics were a mess, too, with cars developing so much lift they’d see wheelspin at 200 mph. After two aerodynamically unstable GT40s crashed during testing in 1964, one test driver, Roy Salvadori, quit. “I opted out of that program to save my life,” he said.

And the brakes were a constant problem. Ford engineers calculated that when a driver hit the brakes at the end of Le Mans’ Mulsanne Straight, the front brake rotors would spike to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit within just a few seconds, causing the rotor to fail. Trying to slow a 3,000-pound car from 210 mph, every three-and-a-half minutes, for 24 hours was a new problem in racing. “Dan Gurney told me that everything he did driving that car was about saving the brakes,” Lerner says. “At the end of the Mulsanne, he’d back off well before the brake zone and coast down so he wasn’t scrubbing 180 mph all at once.” Carroll Shelby told Baime: “we won [Le Mans] on brakes.”

Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon’s #2 Ford Mk II opposite Richard Attwood and David Piper’s #16 Ferrari 365 P2 Spyder at the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans. Getty Images.

That’s because Phil Remington, an engineer on the Ford team, devised a quick-change brake system that allowed the mechanics to swap in new pads and rotors during a driver change, meaning drivers didn’t have to worry about making the brakes last beyond their stint. Other teams cried foul about the GT40’s pit-stop advantage, to no avail. “They complained that it was breaking the rules,” says Baime. “But there were no rules.” And that wasn’t the only area where Ford was pushing boundaries.

To ensure their engines could survive Le Mans, Ford ran them on a dynamometer operated by a program that simulated performance and durability. They logged the RPM and shift points of a lap around Le Mans and then had computer-controlled servo actuators “drive” a test engine in exactly the same way in a lab, even simulating pit stops with periodic shutdowns. The engineers would run an engine until it exploded, examine what went wrong and fix the next iteration. Eventually, when the engineers could make a 427-cubic-inch V-8 last for almost two back-to-back Le Mans simulations, they decided their design was hearty enough.

And in 1966, it actually was, with Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon’s #2 car leading a dramatic 1-2-3 Ford victory at Le Mans. The next year, Ford returned to France and won again.

Le Mans start in 1968.

With repeat wins in hand and the Deuce’s ego assuaged, they withdrew official Le Mans factory support after the 1967 race — but still won in ’68 and ’69, with privately owned GT40s claiming victory each year.

Henry Ford. Getty Images.

Over the span of a few years, Ford had unveiled the Mustang, won at Le Mans and vanquished its fuddy-duddy image. Some of the GT40’s engineering lessons might have translated to Ford’s street cars, particularly the computer-driven durability testing, but Ford considered the Le Mans program a marketing exercise rather than a quest for innovation.

Enzo Ferrari. Getty Images.

Manufacturers are still willing to spend big on internal race programs. During Audi's recent reign of dominance at Le Mans, the company spent about $250 million per year on its race team and Ferrari reportedly spends $500 million each year on its Formula One program. It's hard to say if those massive budgets translate to car sales, but most Audi customers probably haven’t heard of the R18 e-tron quattro, the last Audi to win Le Mans. Racing is still integral to brands like Ferrari, but mainstream companies like Audi and Toyota struggle to justify the high price tag.

It’s estimated Ford spent $25 million or more on their way to victory at Le Mans. They even burned $1 million in 1968 before withdrawing financial support from the race program. The GT40 itself was obsolete by 1970 (Ford hasn’t had an overall victory at Le Mans since 1969), but the car’s story continued.

In 2005, Ford released a modern reincarnation of the GT40, the Ford GT, a retro-styled homage to the greatest American endurance racer ever built. It was (and is) so popular that the model, built for only two years, can now be sold for more than double its original MSRP. In 2017, Ford went even bigger, unveiling the current-generation Ford GT. Priced at about $500,000, it’s a sheer bedroom-poster fantasy car, a machine that looks like it drove straight out of the winner’s circle at the Circuit de la Sarthe. In 2016, 50 years after its first win, Ford won the GT class at Le Mans with the new car, beating — who else? — Ferrari, by a mere 10 seconds.

“The Ford GT40 story encompasses all of these larger-than-life characters: Enzo, Lee Iacocca, Shelby, Henry Ford II,” says Baime. “But the car is a character too and it’s larger than life. That’s why we’re still talking about it 53 years later.”

24 Hours of Le Mans. An overview of the world's oldest sports car endurance race. September 21, 2020.

Considered to be one of the most prestigious automobile races in the world, the 24 Hours of Le Mans pushes manufacturers to build cars that combine speed with reliability. As a result, racing teams must balance the demands of speed with the cars' ability to run for 24 hours without mechanical failure.

Official Logo. Wikimedia Commons | View Original.

Race History

The 24 Hours of Le Mans is held in France just outside of a small town called Le Mans, from which the race draws its name.

Location of Le Mans, France

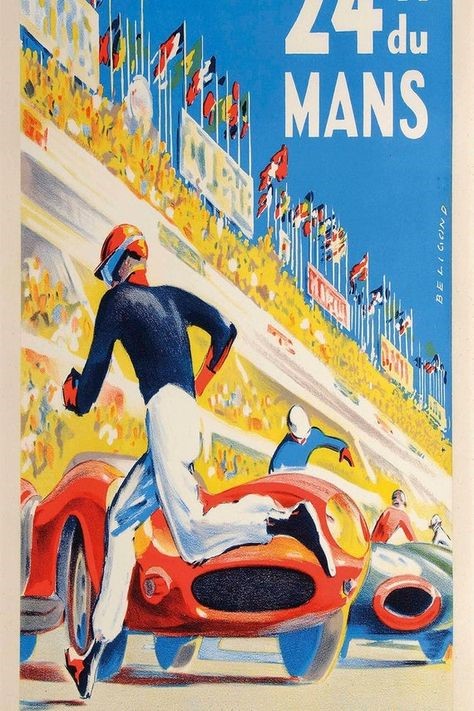

First event poster, 1923.

When it began, the original plan was for the race to be a three-year event that would culminate with one winner who drove the furthest distance over three 24-hour periods. However, this plan was abandoned in 1928 and individual winners for each year became the standard. Early years of the race saw brands like Bugatti, Bentley and Alfa Romeo have success and win a number of championships.

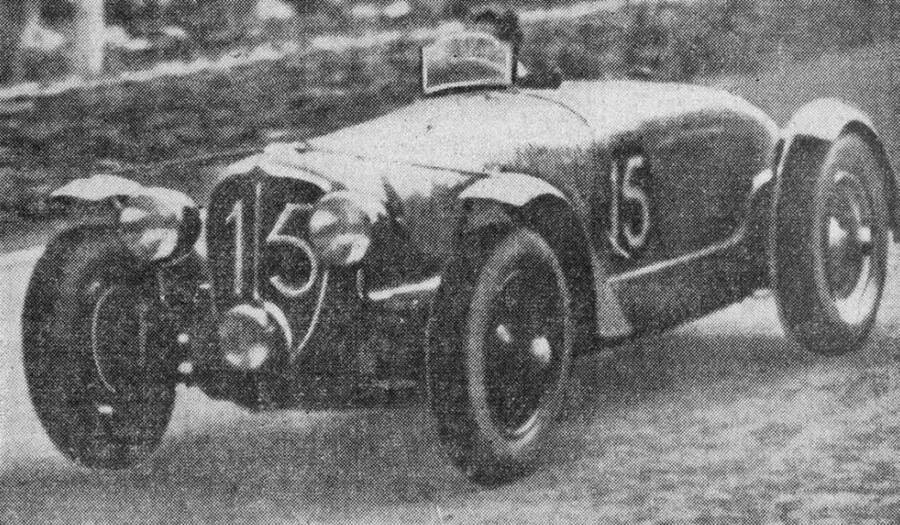

Racing, 1932. Wikimedia Commons | View Original.

After World War II, the circuit was redesigned and new manufacturers took interest in the race. Ferrari, Jaguar and Aston-Martin became competitive with one another and each brand's goal was to amass the most victories. Racing speeds increased and fatal crashes occurred, resulting in an overhaul of safety standards as well as an entire rebuild of the pit straight complex following the 1955 Le Mans disaster.

Nighttime Scene, 2016. | CC-BY-SA 2.0 | View Original.

Despite the advances in engine performance and car design throughout the 1960's, 1970's and 1980's, many major automobile manufacturers withdrew from sports car racing after 1999 due to its high cost. Brands that continue to win at Le Mans are Porsche, Audi and, most recently, Toyota with consecutive victories in 2018 and 2019.

Ford #2 Car, 1966. | CC-BY-SA 2.0 | View Original.

Circuit de la Sarthe

The racing circuit used in the 24 Hours of Le Mans is named “Circuit de la Sarthe”. Since 1923 the track has been extensively modified, mostly for safety reasons and is currently 13.63 kilometres (8.47 miles) in length.

The circuit has a number of defining features that make it a unique one for both racers and spectators alike.

Full Circuit

The full circuit is a loop that begins in the pit straight, then east towards Tertre Rouge, south to Mulsanne and west towards Arnage before returning north to the pit straight.

Top Winners

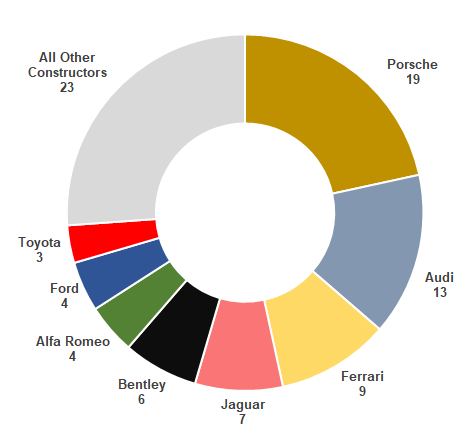

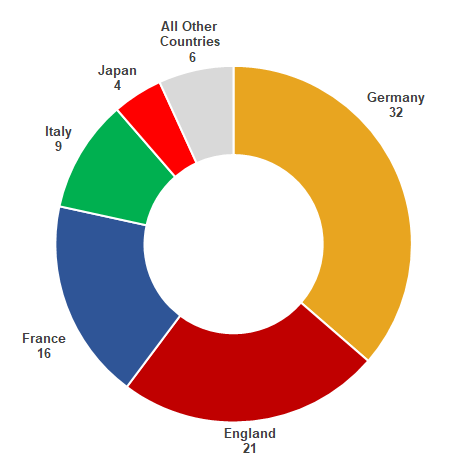

Since 1923, there have been 87 editions of the 24 Hours of Le Mans race. The following charts summarize the winning race car constructors, tire manufacturers and the countries of where each racing team hailed from.

Race Car Constructors

While Dunlop still holds the most wins all-time, every 24 Hours of Le Mans win since 1998 has been by a race car outfitted with Michelin tires.

Racing Teams by Country

Largely helped by the success of Porsche and Audi, it is no surprise that German racing teams have a healthy lead on the number of wins when compared to other countries. With three of their four wins coming in the last three years, Japan has emerged as a new force to be reckoned with.

Hawaiian Tropic is an American brand of suntan lotion, sold around the world but more widely available in the United States.

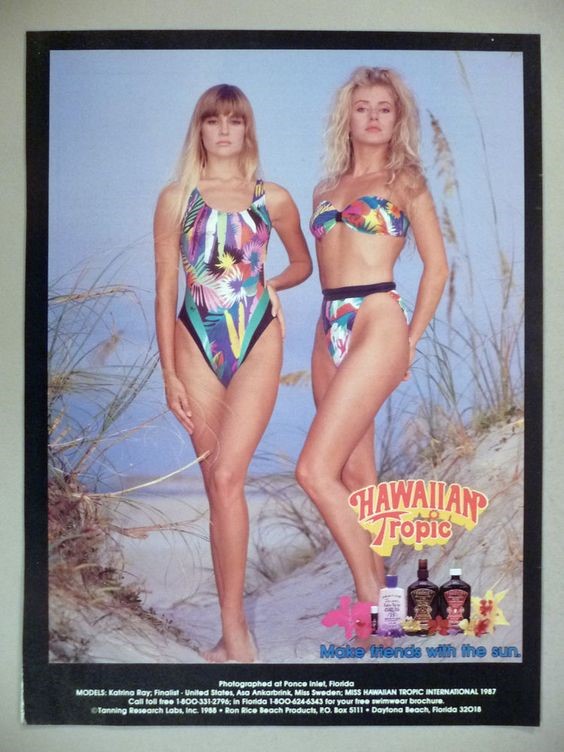

Hawaiian Tropic 1983 advertising.

Hawaiian Tropic 1988 advertising.

The company sponsored bikini competitions to seek women to serve as spokesmodels for their products.

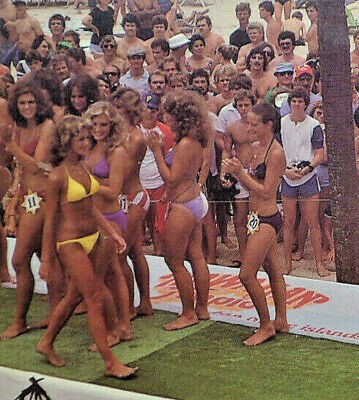

Vintage Myrtle Beach S.C. Tan Bikini Girl Hawaiian Tropic Contest.

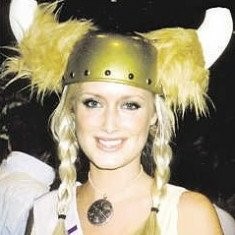

Cecilia Hörberg, Miss Hawaiian Tropic International 1984.

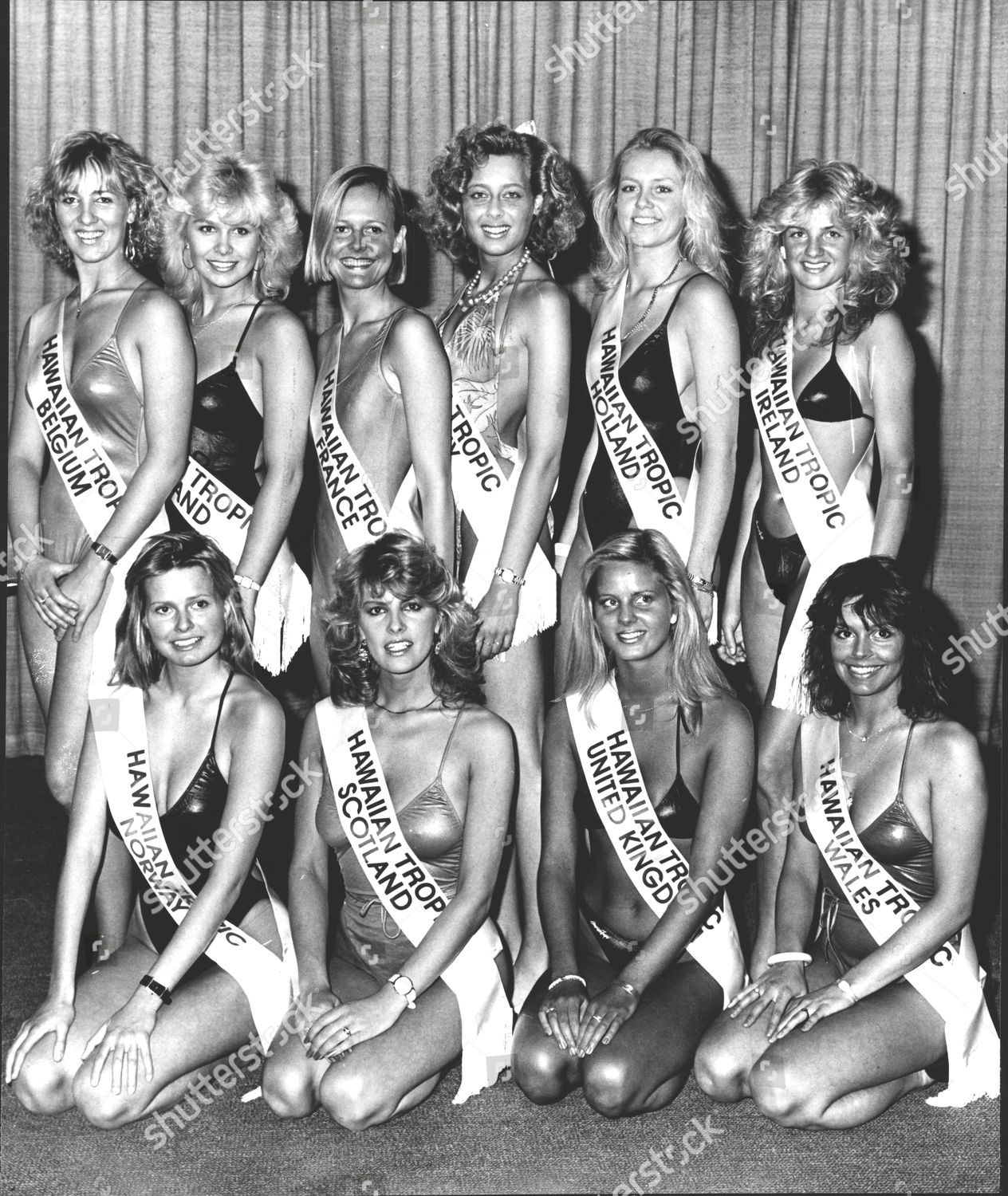

The Miss Hawaiian Tropic International Beauty Contest. European contestants leaving Heathrow Airport. Back row (l-r) Els Pieters, Maria Rice, Mundy Virgine Soubiran, Stefanie Bour, Ilse Weller and Karen McGrillen. Front row (l-r) Anne Sofie Falkenaas, Lorraine Davidson, Sharon Gleed and Kaeren Watson. April 9, 1985. Stock image. Editorial credit ANL/Shutterstock.

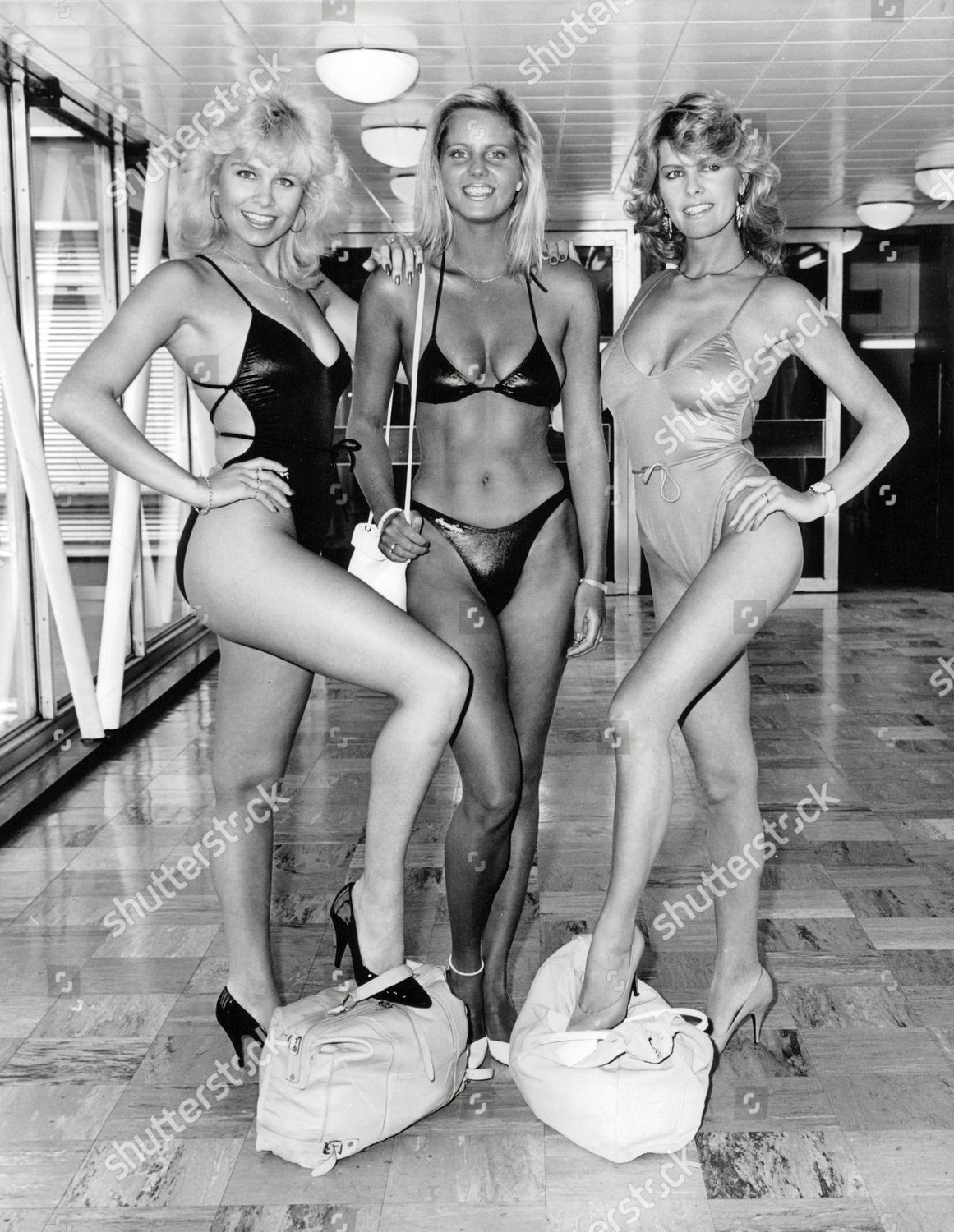

(L-r): beauty contestants Maria Rice-Mundy, Sharon Gleed and Lorraine Davidson at Heathrow Airport. Stock image, April 09, 1985. Editorial credit ANL/Shutterstock.

Erika Johnson, Miss Hawaiian Tropic International 2001.

Many winners appeared later in advertising campaigns, swimwear, erotic magazines and lingerie catalogs.

The Hawaiian Tropic Girls were a tradition at 24 Hours of Le Mans.

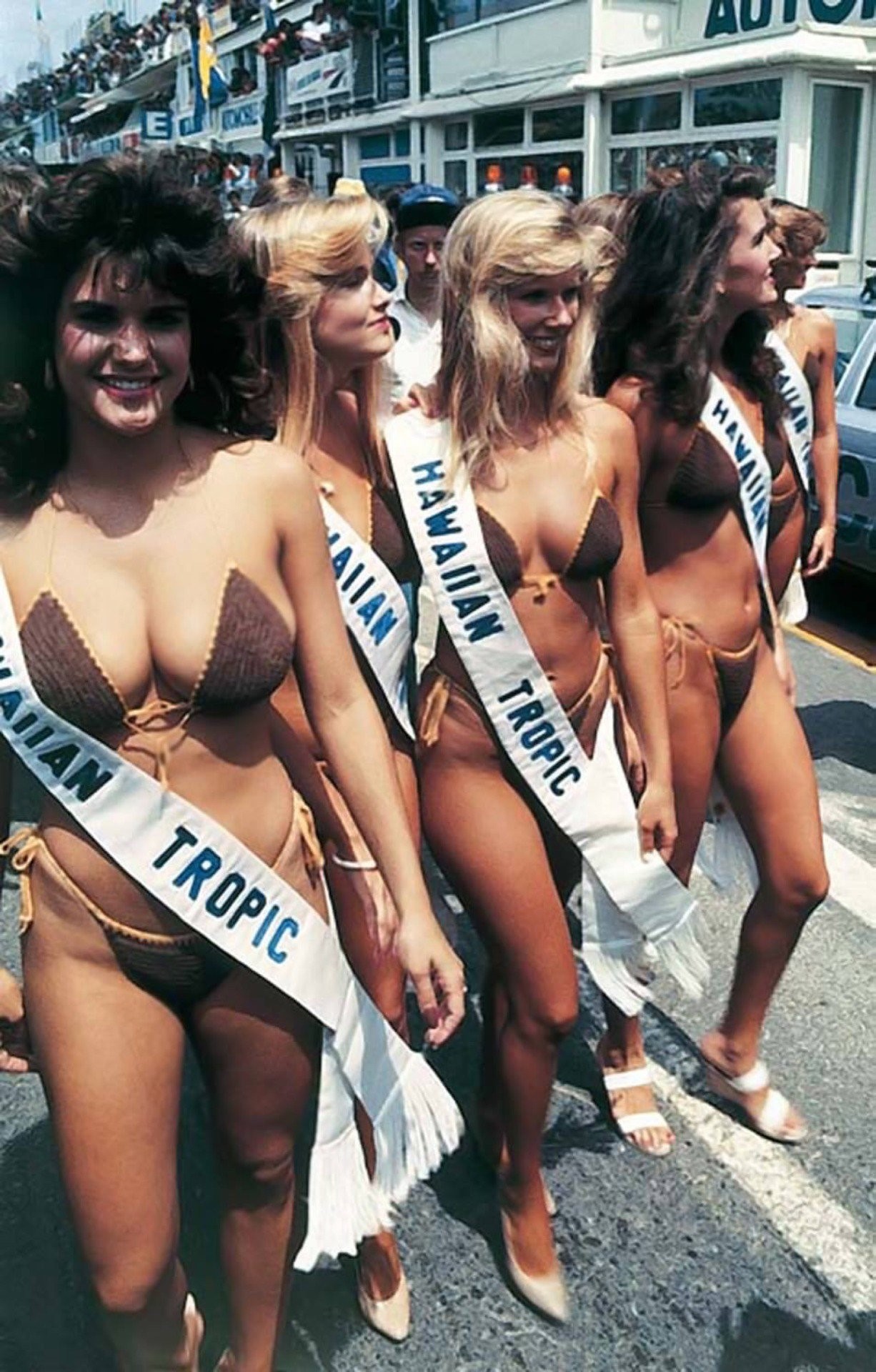

The Hawaiian Tropic girls strut their stuff at Le Mans in 1981.

Miss Hawaiian Tropic contestants in 1983.

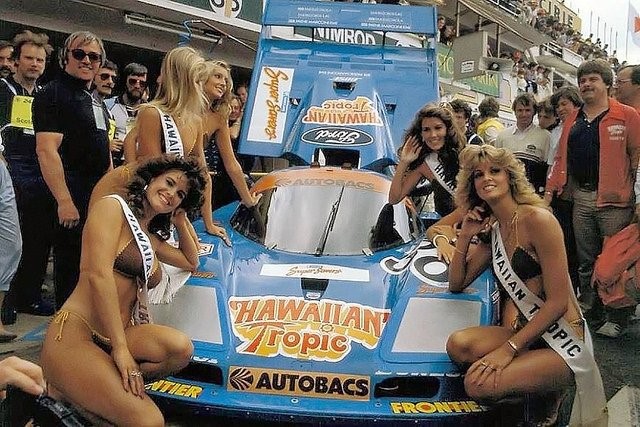

Le Mans 24 hours, 18-19 June 1983. Derek Bell (Porsche 956), 2nd position, with the Hawaiian Tropic girls in the paddock. World Copyright LAT Photographic.

Le Mans 1991.

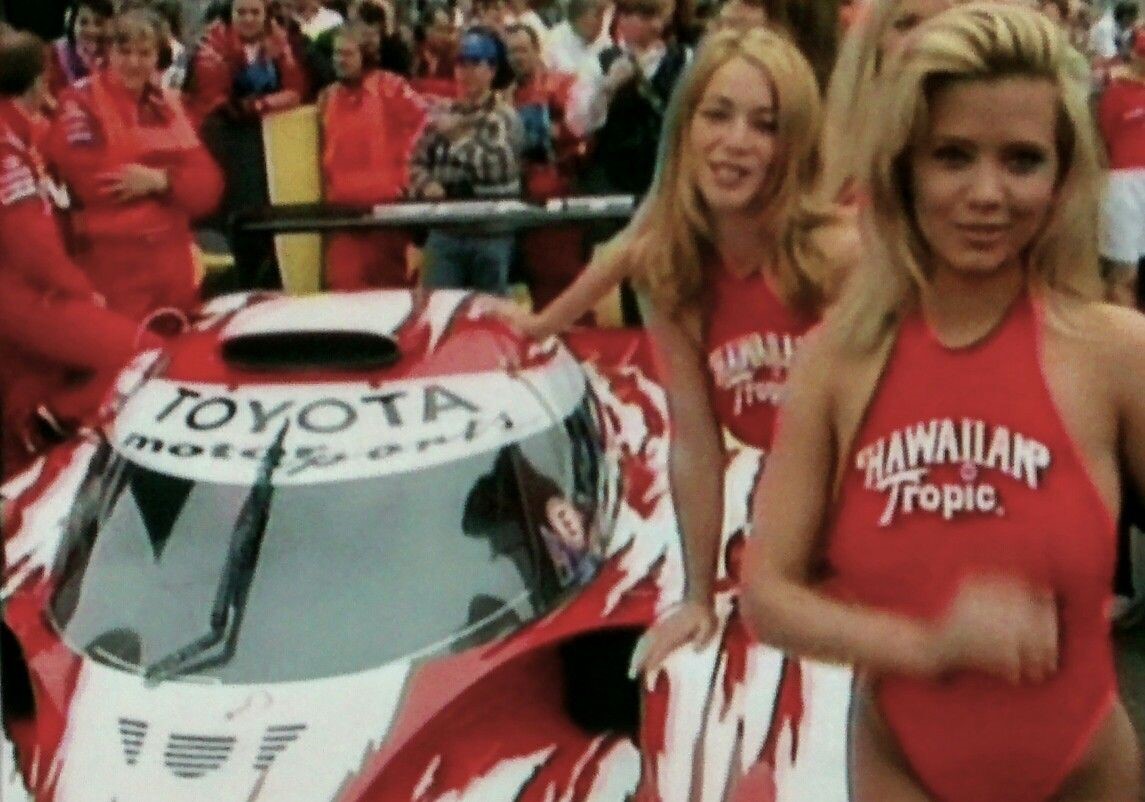

Hawaiian Tropic girls at Le Mans 24 hours race in 1998.

Pit babes Hawaiian Tropic girls were present as usual. Le Mans 24 Hours, 14-15 June 2003. Image credit Imago Motorsport Images.

Le Mans traditions. Hawaiian Tropic girls and photographers on 09.06.2012. By John Brooks.

Traditional values. John Brooks, January 2012.

As I sit in my office trying to dream up ways of avoiding doing the jobs that are urgent, my mind wanders. Today it struck me that the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, normally great custodians of tradition, have casually let go one of the most popular elements of the great race over the past 30 years. I refer of course to the Hawaiian Tropic Girls.

Back in the mists of time when I first was granted a press pass for Les Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans, one of the assignments that I had from the agency was to make sure I got some frames of the girls. Well, as those of you who know me will attest, I am diligent on such matters. The 1984 crop was a vintage one and very well recorded for posterity.

Fast forward to 2008. I got a request from Stuart Radnofsky to go down into the pitlane and shoot some girls around a car. Of course it being Stuart I knew that it was the HT crew.

Oddly enough I had plenty of volunteers to assist me with this arduous task and I could have done with a squad of the SAS to keep the mobs at bay. Nevertheless, with the cooperation of the Team Bruichladdich, I managed to get material for the client.

I am normally ambivalent when it comes to grid girls at the races. Sure they are for the most part easier on the eye than the mechanics and drivers …… and let’s not mention the media …… but the spectacle of middle aged guys drooling over pretty girls half their age is repellent and pathetic in equal measure ……. you know who you are, so stop it now!

But the Hawaiian Tropic Girls were different, here was a tradition that stretched back into the last century, they should be returned to La Sarthe in time for this year’s contest. And yes, I did get paid to shoot the girls …. Living The Dream? Oh Yesssss.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans (French: 24 Heures du Mans) is the world's oldest active sports car race in endurance racing.

It is considered one of the most prestigious automobile races in the world and has been called the "Grand Prix of Endurance and Efficiency". The event represents one leg of the Triple Crown of Motorsport, with the other events being the Indianapolis 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix.