Two drivers and two men opposites, united by the geographical origin and the tragic fate.

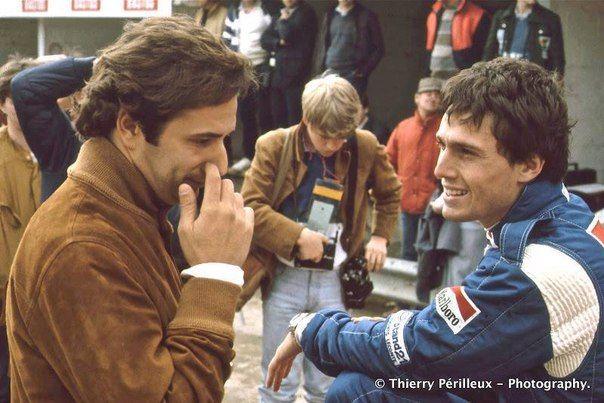

1983 San Marino. Elio De Angelis and Andrea De Cesaris.

Two free souls, two real enthusiasts who only behind the wheel made sense of their lives. They were the highlights of our childhood with their deeds and with them something in us and in our town died. A sense of “fellowship” a little stronger than with the other drivers, they were really neighbours.

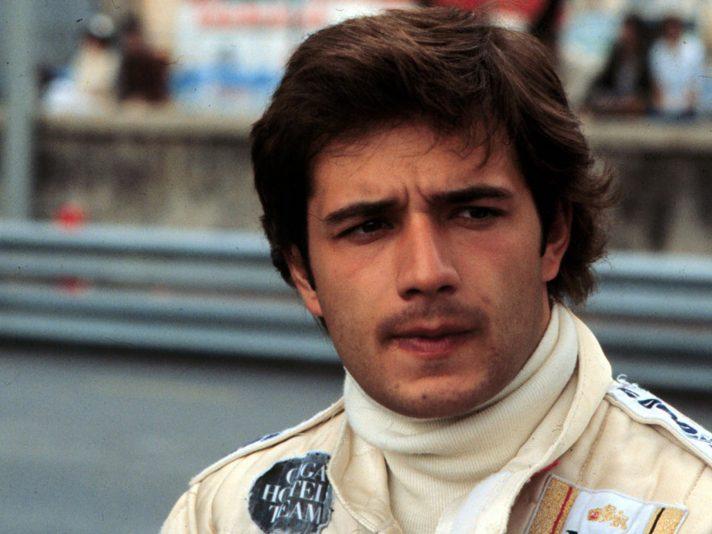

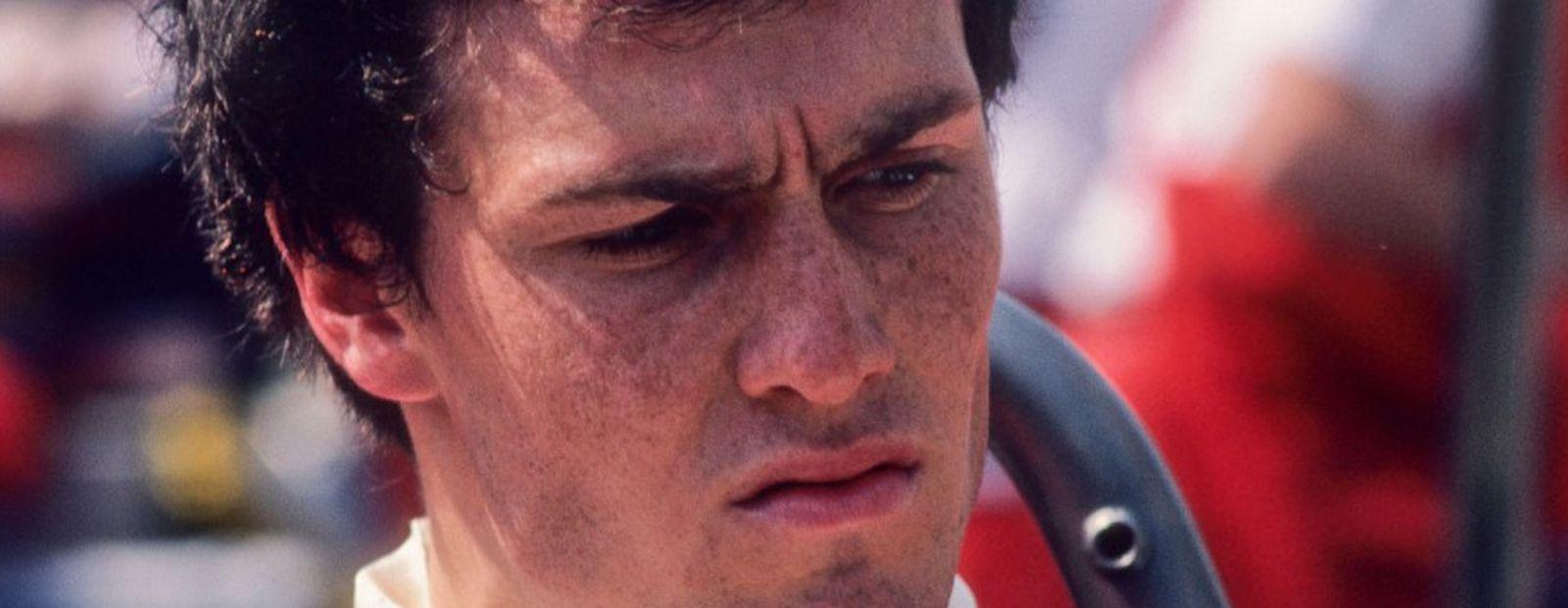

Elio De Angelis,

rich and well-educated. Gentleman driver, with fine manners.

He wanted to race and he used to do it soberly, without screaming.

Elio De Angelis, Brabham.

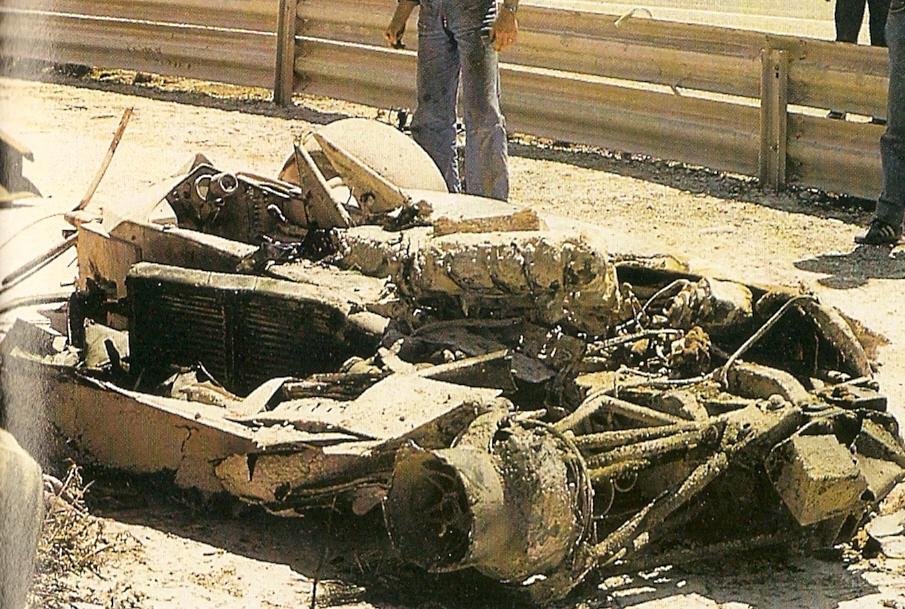

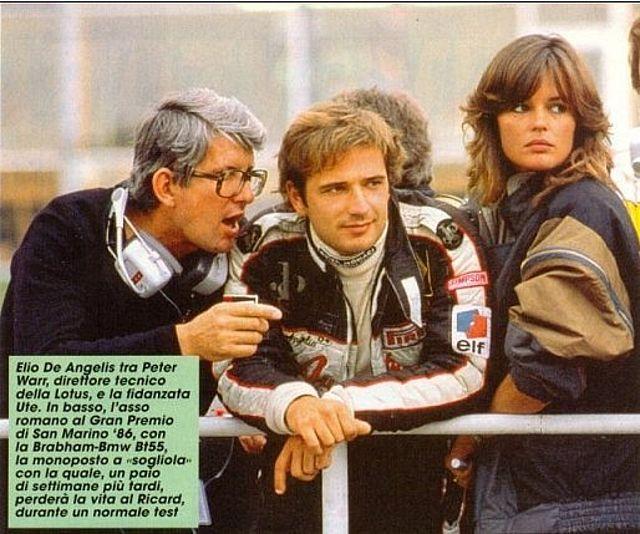

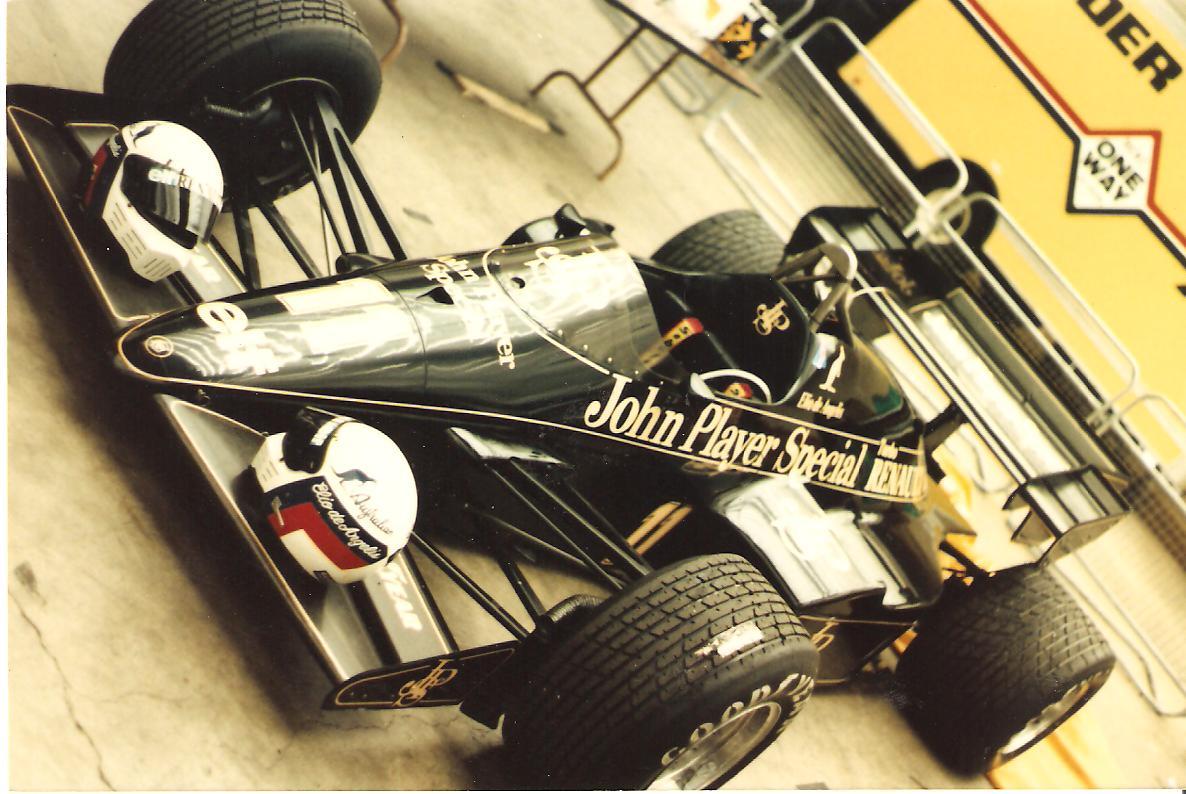

Introspective and elegant. Betrayed by team Lotus in favour of the emerging and full of sponsors Ayrton Senna, he does not accept the role of second driver and in 1986 joins team Brabham, whose car disappointing so much so that he plans to stop racing, before fate makes decisions for him. On 14 May 1986, during tests at the Paul Ricard circuit in France, a new rear wing is installed on Elio’s car, the Brabham BT55 number 8. Alan Jones in a Lola Beatrice and Philippe Streiff in a Tyrrell are testing their cars as well. At 11.30, suddenly, on the way in the “Esses de la Verriere”, at an average speed of 270 km/h, the rear wing of de Angelis's BT55 detached resulting in the car losing downforce on the rear wheels, which instigated a cartwheel over a sidetrack barrier, causing the car to catch fire. The last lap of Elio De Angelis. The car got catapulted through the air and landed approximately 200 meters further, over fences bordering the track. The impact itself did not kill de Angelis but he was unable to extract himself from the car unassisted. The situation was exacerbated by the lack of track marshals on the circuit who could have provided him with emergency assistance. Only a couple of mechanics of team Benetton witnessed what happened. The first to quickly stop are Alan Jones, Prost, Laffite, and Rosberg, who gotten out of their cars and with fire extinguishers in their hands turn them on Elio’s car in flames. De Angelis is trapped under the carcasse. Prost does not hesitate to jump in the fire trying to get him out, but there’s nothing to do.

While drivers are looking for other fire extinguishers to put out the fire, the fuel tank of the Brabham explodes starting a fire even to a pine tree bordering the track in that area. When rescue come and finally fire’s out, everyone tries to get the driver out, after having straightened out the car but it takes a long time. The doctor right away checks Elio’s pulse and says “it’s over” adding then “we will go all in”. For 15 minutes they do chest compressions and artificial respiration until heart starts beating. A 30-minute delay ensued before a helicopter arrived and de Angelis died 29 hours later, at the hospital in Marseille where he had been taken, from smoke inhalation. His actual crash impact injuries were only a broken collar bone and light burns on his back. Gordon Murray will never understand what happened, constrained by the fact that it was the first time in which a driver died in a car which he had designed. For a long time he will be about to retire. Furthermore we will never be able to understand whether the rear wing has come away because of special revolutionary design of the BT55 or not. Murray will stop working for team Brabham after the season and the history of F1 doesn’t remember his other pioneering projects. Anyway even today, the same designer reckoned himself solely responsible for Elio’s death, taking all the responsibilities to designing an extreme car.

“Elio De Angelis couldn’t help himself from being handsome and rich”, a Spanish journalist said the day the Italian driver died. Such fatalism in the sentence that for a minute you could have thought that De Angelis would have been consumed by beauty and money. The truth is that he died due to an explosive cocktail of passion for speed and a catastrophic security device at Paul Ricard. “Elio De Angelis was the archetype of the driver of a bygone era: for him elegance took precedence over the efficiency”, said of him the reporter and former driver Johnny Rives. He had great hands and his future was to become a concert pianist. But his passion was priceless.

Elio De Angelis and Nelson Piquet.

He left the sheet music and the piano for the gas, tracks and the steering wheel; he competed in a legendary period in which he raced Nelson Piquet, Keké Rosberg, Niki Lauda, Ayrton Senna, Gilles Villeneuve, Alain Prost and Nigel Mansell.

Elio De Angelis and Nigel Mansell.

“Elio from the start had decided that to be his life, he had studied to be a driver and achieved his dream. He succeeded and was happy before his fate was written,” Giovanni Malagò, the President of CONI, recalls.

He was about to drive a Ferrari, as Giancarlo Minardi says: ”Enzo Ferrari asked me if he would have been ready to drive a Ferrari and I told him he could.”

Even the former Ferrari driver Jean Alesi talks about him: ''above all I liked the person that he was. That’s why I had his patches on my helmet and now my son, who luckily is a driver, has them on his one.”

Giorgio Terruzzi says in his article of 4 August 2014: “the broken smile of a champion-born guy. An end with an absolute pain in it. A sweetest but never completely cheerful smile, as if a fold of Elio’s soul turns into an intimate and dark melancholy. Mind you, though. I’m talking about a champion, a guy in many ways lucky, born to a good family in Rome, son of a builder, Giulio, more than well-to-do, part of a family full of light, of sun. Ready soon to board races. He and Beppe Gabbiani in small Formula 3, knowing that he had the necessary talent to emerge and all of his bases were covered to obtain cars and tyres up to every aspiration. Elio won a lot and soon.

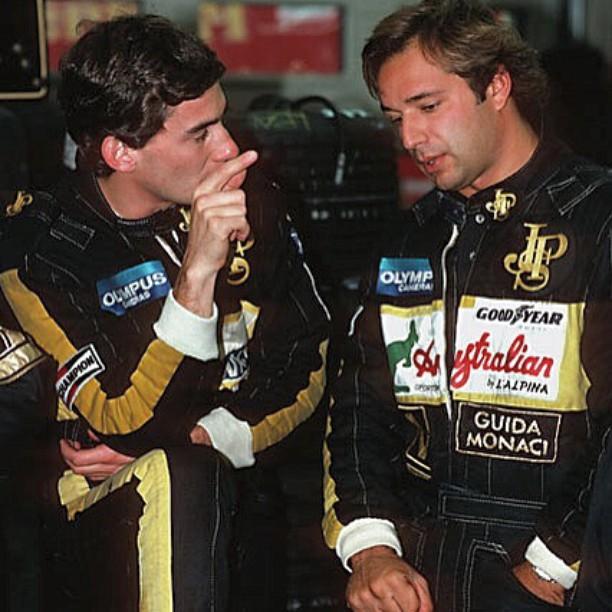

When Lotus found already another love, a young guy, ferocious, really fast, Ayton Senna. Chapman had died, at the end of that terrible and magnificent 1982. His race family had changed.

And Senna, as a team mate represented a bother almost chronic.

Brabham BT55.

He went to Brabham, with Patrese, for 1986, a critical season at the beginning, a dangerous car, lots of efforts for nothing, before ending up like that, excruciatingly. Now this summer so far from the last images of Elio who speaks with a special calm, who takes and goes, I find him playing the piano, a deep passion. His handsome face, of a decent guy, destined to race for good in a magic blaze. He was a symbol, an Italian icon in a fast-paced time and even mindless, despite the risks, the technological long shots of a Formula One in many respects still unholy. I see that white helmet with friezes that are back on track like the insignia of a champion who we too often relegated somewhere in memory. Thus surges over me a very sad wind of heat, of nuggets slipped through my fingers and irredeemably lost.”

Testimony of Ayrton Senna from the book “Senna vero” (the true Senna): “the day before Elio’s accident I made a terrible mistake. I had car troubles and before getting back to the pits I did a lap very slowly and, as I looked around me, down the track security services were practically non-existent. I saw a man with a fire extinguisher, just one, but I didn’t worry overly. I thought the one of Ricard was a very long circuit, full of wide spaces, and perhaps there was the emergency service, even though from my cockpit you couldn’t see it. When I got back to the pits I totally just forgot about the problem. Unfortunately drivers do not think a lot about the danger: we know that there is but we see it like something distant. Finished that lap I should have advised myself better of the situation, let them tell me where they were the men of fire service and sensitise the other drivers on the problem. I didn’t do it this time as well as I didn’t in the past during other sessions of free tests. And which is why I feel a share of the responsibility myself about what happened.”

The reporter Nestore Morosini, in the Corriere della Sera in 2016, says about Elio: “son of Giulio De Angelis, Motonautica champion, Elio travelled in Europe on his father’s jet, hosting on board his two great friends, Nelson Piquet and Piercarlo Ghinzani. Elio won the Lottery GP at Monza: he, a millionaire, had distributed million of the national competition. A good headline for the sports page of the “Corriere”. One day he saw me, in Germany, and told me: “you know I can’t forgive you for that title? I don’t appreciate to be called a millionaire for my father’s money and not a driver. The family fortune can even help you, but to move forward you need qualities. And everything my father gave me, I already gave him back.” He had the decency to be like all the other drivers: when he arrived in F1, in 1977, he never used the personal jet and rarely was in first class. Elio was completely happy only behind the wheel of a F1 car and when Rome football team was winning: when the team, then trained by Liedholm, won the championship, Elio celebrated on his boat in Montecarlo.

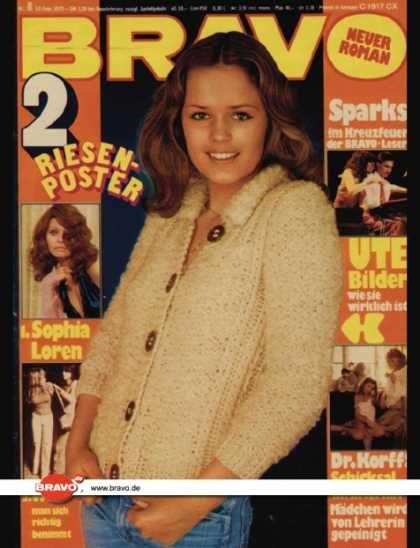

Ute Kittelberger in 1976.

Ute Kittelberger.

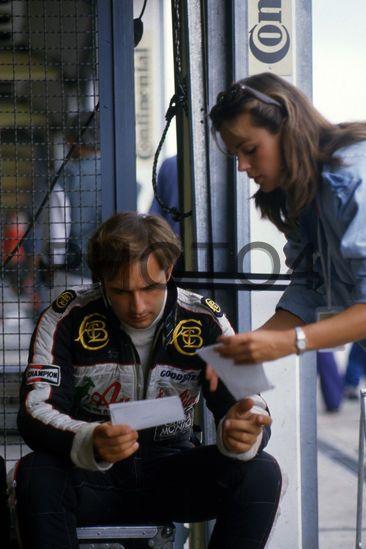

Elio and Ute.

Elio, Peter Warr and Ute.

He had a German girlfriend, beautiful, Ute Kittelberger, and a close brotherly friend, Louis Ruzzi, a young Argentinean engineer who, after Elio died, disappeared from a world that probably reminded him nothing but pain. In the years when he raced, he had only an aversion, the one to Ayrton Senna who was his teammate at Lotus, favourite of technicians and mechanics. He’s dead but has not disappeared. From our heart.”

Elio de Angelis, 26 March 1958 – 15 May 1986, participated in F1 between 1979 and 1986. He was a very competitive and highly popular presence in it, and is sometimes referred to as F1's "last gentleman player". His father Giulio was an inshore and offshore powerboat racer, who won many championships in the 1960s and 1970s. After a brief spell with karts, De Angelis went on to win the Italian F3 Championship in 1977. In 1978 he raced in F2 for Minardi and then for the ICI British F2 Team. At the end of the 1977 season, De Angelis was on Enzo Ferrari's short list to replace Niki Lauda. He successfully tested the Ferrari at the Fiorano circuit but eventually Ferrari decided to hire Gilles Villeneuve. De Angelis's debut F1 season was in 1979 with Shadow. Colin Chapman hired him to partner Mario Andretti at Lotus in 1980. His first victory came in the 1982 Austrian GP at the Österreichring, 0.05 seconds ahead of the Williams of eventual 1982 World Champion Keke Rosberg. The win was the last hailed by Colin Chapman's act of throwing his cloth cap into the air. Chapman died in December that year and Peter Warr became the new Lotus team manager.

Elio De Angelis and Nigel Mansell at Lotus 93 presentation in 1983.

Elio in 1983 with a Lotus.

Elio De Angelis, Austria 1983.

Elio De Angelis, Lotus 95T, at Detroit GP in 1984.

In 1985, De Angelis was joined at Lotus by Ayrton Senna. His second win came in the third race of the season, at the 1985 San Marino GP. Elio also claimed his last F1 pole position that year in Canada. He finished fifth in the championship, with 33 points, five points behind his teammate. However, he chose to leave Lotus at the end of the season, frustrated that the team's efforts were being focused mostly on Senna. De Angelis's drive for 1986 was with Brabham. Fellow Italian Riccardo Patrese was his teammate. The 1986 Brabham-BMW, the BT55, was the brainchild of long time Brabham designer Gordon Murray. The BT55 was a lowline car with a reduced frontal area, the idea being to have a cleaner airflow over the car to create more downforce, while at the same time reducing the car's drag. The chassis proved effective, unlike the l4 BMW turbo that had to be tilted to an angle of 72°. This caused severe oil surge and an even greater lack of throttle response than the BMW had become famous for. Although the team worked hard to overcome these problems, it was clear from early in the season that Brabham had fallen behind the leading pack. De Angelis was also a concert-standard pianist. A 300 km/h piano player.

Andrea De Cesaris,

instinctive, ungovernable, an unpredictability which bordered on insanity.

A thousand his reckless endangerment on and off the track. Constantly afflicted by nervous tics. After a looping to make your blood run cold, he described the episode in an interview talking about a spinout. He didn’t even realize of the flight.

Emanuele Pirro and Andrea de Cesaris.

Great Andrea, quick and romantic, you were racing to feel that you were something in the world. With that scrappy attitude not even your brother could have been your friend. But on track he never asked for a discount and didn’t make excuses. On a good day De Cesaris was tough. The acrobat of circuits was saved so many times from himself. He travelled the world to die in his hometown. He found peace, the one he perhaps went looking for. A man alone but a real man. Andrea De Cesaris, really fast cars destroyer. How can we remember him at best?

De Cesaris, pole position at Long Beach in 1982.

For the historical pole position in an Alfa Romeo at Long Beach in 1982?

Credit Formula Passion.

For the flight through the meadows of Zeltweg in a Ligier in 1985?

Andrea de Cesaris, Jordan 191 Ford, in 1991.

As the first Schumacher’s teammate in 1991 at Spa? Nicknamed “Mandingo” in the paddock, he was maybe penalized, instead of being helped, by the very important Marlboro sponsorship, thanks to which he was brought to F1 too early. He surely had the talent, but came to F1 too immature, when he needed to make his bones still for a couple of years in minor formulas. By the way he started immediately with high-end teams without even paying his dues a little bit in smaller ones. He would have had a great need of it. Instead, starting with McLaren and Alfa when he wasn’t ready, he totally destroyed his later career and when he reached agonistic maturity by now he was dealing with low-end teams. In these he continued to distinguish himself, in addition to accidents (you can look at the scary one in Austria), for an unjustified badness when he had to get lapped. He never allowed leaders to overtake him and indeed, sometimes, he deliberately impeded the lapping, like he was fighting for the position. For leading drivers, every time they saw him in front could be a nightmare, as there was always the risk of losing the race because of him. In short, how to remember Andrea De Cesaris? Maybe for the opinion of the circus, which at the end of his career, referred to him so: “the Italian has to be ranked among the quickest drivers never to have won a Grand Prix”. He wouldn’t have been totally happy, but would have loved it. The years of his Formula 1 are the ones of wing cars, turbocharged engines with over 1.000 horsepower, then the abolition of miniskirts, return to naturally aspirated engines, of single seaters pushed to the limit and unreliable (compared to the present ones), with engines juiced at maximum in qualifying and almost at maximum in the race, which often do not complete the mileage of a single Grand Prix. In Formula 1 Andrea didn’t have a chance to find himself in just the right team when it was time, he practically almost never had a really competitive package and equally reliable. He participated in 214 Grands Prix in 15 seasons, debuting on 28 September 1980. He achieved 5 podiums, one pole position, and scored a total of 59 championship points, the whole thing, however, flagellated by well 148 withdrawals, of which 22 consecutive, most of them due to mechanical failures. He remains the driver with the most GP starts (208) to his name without a win. He scored points for 9 out of 10 teams he raced for: McLaren, Alfa Romeo, with which he got the best results, Brabham, Rial, Tyrrell, Jordan, Ligier, Scuderia Italia and Sauber; failing to do so for Minardi only. Moreover his competitors were exceptional drivers, very quick, plenty of champions already established. His strong points were immeasurable grit, aggressive driving (which made him very fast on street circuits) and great determination to prove himself. Always pushing at maximum he also went off the track several times, ruining many chassis. At some point the English press called him “De Crasheris”. In 1981 he also caused a quite unique event and never again happened, the strike of his mechanics who had enough of having to work overtime for repairing all the time the damage he had done to his car. They reached the point where he was left on foot in a Grand Prix, by their refusing to repair the car he had damaged once again in qualifying. Andrea loved one-time Formula 1, the physical one, that without many calculations or just without calculation, the one of technical diversities, of holding your breath till the checkered flag. How can we forget his cleansing cry after being on pole position in an Alfa Romeo at Long Beach?

Andrea de Cesaris and Jacques Laffite.

In 1985, when he was racing for Ligier, his teammate was Jacques Laffite. Over the season, in qualifying he was most of the time faster than the Frenchman, but his competitors were Lotus-Renault of Ayrton Senna and Elio De Angelis, Williams-Honda of Nigel Mansell and Keke Rosberg, Michele Alboreto’s Ferrari, McLaren-Porsche of Niki Lauda and Alain Prost, Nelson Piquet’s Brabham-BMW. Among these “monsters” he manages to qualify often in the fourth row like in Portugal, in Monaco and in Great Britain.

Andrea De Cesaris, the Roman driver who made us dream like Villeneuve. Countless Grands Prix in a Formula 1 car on tracks around the world and a never-ending series of accidents didn’t scratch him. Not even a Grand Prix won but often managing to inspire a lot of fans. It’s an early October Sunday night of 2014. It’s cold in Rome. So cold, far too, having regard to the time of year. In the heart of every race fan, on that Sunday 5 October there was a cold going down the spine like an ice tongue. On Grande Raccordo Anulare freeway there is an infernal line. In proximity of the Bufalotta turn-off there is a mall. Usual shopping binges replacing summer Sundays to the sea? No. There’s an accident. Serious, very serious indeed. A Suzuki motorbike, due to unknown reasons, impacted with the guard rail on the outer lane. Who’s driving it immediately seems to be in desperate conditions. It’s Andrea De Cesaris. When arrives at the hospital “Mandingo” is already dead. One of the most important Italian F1 drivers died in a road accident. With him another piece of Formula 1 left, the F1 of the greats. A driver constantly on the edge, Andrea has always been a match for his teammate on duty in terms of sheer speed: it can be said that the only one who really overpowered him was a guy named Michael Schumacher, on his debut in Formula 1, in the only Grand Prix entered (the Belgian one) with the Jordan. An heavy foot, very heavy, and a passion for windsurfing and physical form, a Roman accent never lost, and a significant number of generations of drivers met in his career: in 1980 there was Gilles Villeneuve’s Formula 1, in 1994 Michael Schumacher’s one. In between, guys like Prost, Senna, Lauda, Piquet and Mansell. The San Roberto Bellarmino church in Piazza Ungheria, in the Parioli area, was packed for the funeral of Andrea: family, friends or simple fans. Also Niki Lauda and Eddie Jordan arrived in Rome to pay their respects. “I met him many years ago. An amazing personality, a great driver, an interesting man, I will never forget him,” Lauda said, wearing his usual red cap but with a voice broken by the commotion. “I have a lot of good memories of Andrea,” Fisichella explained. “He was a sunny person, but above all a winner. He wanted to win everywhere: playing soccer, going go-karting. A great person: his disappearance was a hard blow for us all, and the people’s love proved that.”

De Cesaris, Jordan, in 1991. By Formula Passion.

The television commentator Ezio Zermiani tells: on 6 October 2014: “today I looked at some photos. There’s a great one which is dated July 1991, Andrea is in Mexico and runs out of gas 150 meters from the finish line, I jump promptly on the track, nobody is kicking me out (this says it all about what it was safety then, especially in Mexico …) and I can interview him while he pushes the car to bring it to the line. The cool part is that he looks at me – consider that Andrea was a person with a great body, and that straight was even on a smallest hill – pauses and says wheezing in his beloved Roman dialect: “ma invece di dimme tutte ‘ste fregnacce, perché non te metti pure tu a spigne?“ (but instead of saying all this nonsense why don’t you start pushing as well)? Andrea would have come in fourth anyway in that GP, even if he wouldn’t have crossed the finish line, but he didn’t care of regulations, competition was in his blood”. And again Zermiani: “at the time, between the race of Suzuka and the Australian one, which was the last on the calendar, we all stopped for a few days in the middle with families, to blow off a little steam. That time we were in Bora Bora and, among the thousands of foolishness that people say between friends, Piquet came up with a sentence that in my mind resonates kind of like that: “Andrea, you practice like a fool, instead I eat, drink and do also something else better than you – and on this issue other immense discussions came out – and yet in the end on track I screw you how and when I want”. Andrea didn’t allow him to repeat it twice and challenged Nelson to circle the island on foot. The two left and began an unexpected off and on with the Roman forced to overtake several times Piquet who, promptly, magically came back ahead of him. Of course there was a trick, Nelson found out public transport circled the island and, despite this, Andrea almost won, even if the other guy was taking the bus. Do you understand what was he like? We laughed for two weeks by telling each other this story.”

1982 Monaco. Andrea De Cesaris, Elio De Angelis, Riccardo Patrese and Didier Pironi.

“I look back with pleasure also to what happened in the crazy race of Monaco 1982. Practice wanted the Monte Carlo winner to have the honour of starting the dance at tonight’s gala in the castle with the princess, in this case a certain Grace Kelly… Obviously tuxedo was called for, but Andrea had never seen a tuxedo. At the end of the Grand Prix I interviewed Riccardo Patrese, still unaware he was the winner at that dashing end of competition. I was the one who informed him of victory, and in that moment De Cesaris, who finished third, as in Mexico due to lack of gas in the last lap, intervened joking: “Aho, guarda che t’ho lasciato vincere! Io non ce l’ho lo smoking, che vengo a fare il ballo con la principessa con la maglietta della salute? Vacci tu, che sei il solito gasato sempre con lo smoking nella valigia“ (Ehi, I’m telling you I let you win! I have no tuxedo, what could I do, dancing with the princess wearing a sweater? Go yourself, who are the usual gassed always with tuxedo in the suitcase). He’s gone pedal to the metal, and I believe that, compared to all the other ways to die, he would have preferred it”.

Andrea de Cesaris, 31 May 1959 – 5 October 2014, never won a F1 GP, holding the record for the longest career without a race victory. A string of accidents early in his career earned him the nickname "Andrea de Crasheris" and he became known for being very fast but also wildly erratic. The nickname stuck, though he went on to become a calmer, more mature driver in his later career. A multiple karting champion, he graduated to Formula 3 in Britain, winning numerous events and finishing 2nd in the championship. From Formula 3, he graduated to Formula 2 with future McLaren boss Ron Dennis' Project 4 team.

Andrea de Cesaris, Alfa Romeo.

In 1980, De Cesaris was picked up by Alfa Romeo for the final events of the that World Championship.

De Cesaris and John Barnand at McLaren. By Formula Passion.

In 1981, largely thanks to his personal Marlboro sponsorship which also happened to be McLaren's main sponsor, De Cesaris landed a seat at McLaren. Although he was quick the season was not a success, with him crashing no less than nineteen times either in practice or the race and sometimes in both; often due to driver error. The team was so worried that he would crash the car that they withdrew his car from the Dutch GP in Zandvoort, after he qualified 13th. The Italian managed to finish only 6 of the 14 races he started. A sixth place at Imola was his best result.

Andrea de Cesaris in 1982 at Swiss Grand Prix.

Moving back to Alfa Romeo in 1982, De Cesaris took pole position at the Long Beach GP. He was nearly always seen by most in the paddock as prone to occasional brilliance but more often than not, erratic behaviour.

Andrea de Cesaris, box Alfa-Romeo. By Formula Passion.

In 1983, with his Alfa Romeo now using a turbo engine, he took two second places, one at Hockenheim in the 1983 German GP and the other one in the season-closing 1983 South African GP at Kyalami. De Cesaris moved to Ligier in 1984, where, despite the car's promising Renault turbo engine, he did not build on his earlier success. He scored only three points during the season. The 1985 season did not prove any better for Andrea. A number of strong performances including a fourth place at Monaco showed early promise but the season turned into a dismal one after he destroyed his Ligier JS25 in a quadruple-rollover at the Austrian GP, and was fired by team boss Guy Ligier as a result. His single-seater suddenly lost grip and went with wheels outside the tarmac, on the grass. Touched the lawn, it took off gone mad, digged its heels and started a series of flips. A terrifying accident, lasted endless seconds, from which Andrea saved by a miracle, without a single scratch. In the meantime, images of a lifetime bounced around his head. “When I got out of the cockpit of my Ligier, I pulled away groggy. The next minute I looked behind me to see what the car looked like and I realized the disaster was averted. In that moment it made me say “che culo che c’ho avuto” (you’re fucking lucky, man). After spending countless money repairing cars De Cesaris had crashed in his 20 months with the team, Guy Ligier stated that "I can no longer afford to employ this man" (this was despite Marlboro paying the bulk of his salary). In 1986 De Cesaris moved to Minardi. In an overweight car with the underpowered Motori Moderni engine, he was more often than not outpaced by his teammate, fellow Italian and F1 rookie Alessandro Nannini. For the first time in his career, De Cesaris went an entire season without scoring a point. In 1987 he switched to Brabham-BMW. With the Bernie Ecclestone-owned team he got back to better results, even though he mostly did not match his teammate Riccardo Patrese. At the 1987 Belgian GP at Spa, De Cesaris placed third behind Alain Prost and Stefan Johansson, his first points in nearly two years and his first podium finish since the final round of the 1983 season in South Africa. He would not finish another race that season. Although he usually qualified well the powerful BMW turbo would often end its races by exploding in flames. For 1988 Andrea found a new home at the new Rial team. The car was extremely slimline, but, with Cosworth power, he managed to qualify for all the sixteen races of the season and took fourth place in the Detroit GP. For 1989, the Italian moved to a team where he had one of his best seasons, the red and white Marlboro-sponsored Scuderia Italia squad. Early results were again promising. He finished third in Canada in a rain-soaked race. It would be the last time De Cesaris stood on the F1 podium. Scuderia Italia's promise was not repeated in 1990. De Cesaris was involved in a number of incidents during that season. He also nearly took out the Ferrari of 2nd-placed Nigel Mansell while being lapped during the race, prompting BBC commentator and 1976 World Champion James Hunt to call him an idiot on live television. He again failed to score a point all season.

Andrea de Cesaris and Alessandro Zanardi ('Pepsi' Jordan-Ford 191). Japanese GP, Suzuka, 1991.

De Cesaris was signed by Eddie Jordan in 1991 for his team's first season in F1. Jordan had already run the Italian in Formula 3. In the race in Canada he finished a strong fourth. De Cesaris then rebuffed anyone who thought this was a fluke by repeating the result next time out in Mexico. The following race in France he finished sixth. He did not score again after this midseason purple patch, but his day of days came during the 1991 Belgian GP at Spa-Franchorchamps. Despite the pressure of being outqualified by debutant teammate Michael Schumacher, De Cesaris moved through the field to take second position until his car's Ford HB V8 blew. He finished the season 9th in the standings, his best result since 1983. For the 1992 season Ken Tyrrell hired De Cesaris for his team and his faith was quickly repaid when he took a fifth in the second race of the season in Mexico. The Ilmor V-10 powered Tyrrell 020 was a decent car, and Andrea was in the points three more times during the season culminating in a fourth place in the Japanese GP. 1993 was very different. The car, featuring active suspension, was not a success. For the third time in his career, De Cesaris failed to score a point and left Tyrrell at the end of the season. In 1994, for the first time since 1980, De Cesaris started the season without a F1 drive. But for the San Marino GP, Eddie Jordan brought him back to the team where he had earned his best results back three seasons earlier. The return didn't start well when De Cesaris wrote off a chassis during testing. He crashed again during the San Marino GP at Imola due to poor fitness having not driven a race distance in six months. He bounced back in Monte Carlo, where he stayed away from trouble and away from the barriers to take fourth place. Irvine returned for the next race but Sauber had noticed the Italian's form, and signed him to replace the injured Karl Wendlinger in the Mercedes-powered machines. De Cesaris' first race for Sauber was his 200th GP, in Canada. Although there he retired after 24 laps, he was back in the points at the next event, the French GP at Magny-Cours. De Cesaris' career then ended much as it began, when he retired with throttle problems during his last race, the 1994 European GP. After retiring from motor-racing, De Cesaris became a successful currency broker in Monte Carlo.

Andrea de Cesaris windsurfing.

It has been reported that he spent six months of the year in this occupation and the remainder windsurfing around the world. Long absent from the F1 paddock, Andrea appeared at the 2005 Monaco GP, and was welcomed back with a warm hug from former Brabham team boss and F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone. A few months later it was announced he would race in the new GP Masters series for retired F1 drivers. While some drivers had spent their retirement years accumulating kilos, De Cesaris was still in top physical condition thanks to his frequent windsurfing. In October, he proved he had lost none of his speed, setting the fastest time in the first GP Masters test at the Silverstone South circuit in England. In the first race at the Kyalami circuit in South Africa, De Cesaris qualified well and raced to fourth, after a fierce battle with Derek Warwick. He was killed in a road accident at age 55. It was cold that Sunday in Rome, very cold.

Videos

Elio De Angelis

Andrea De Cesaris

Comments

Authorize to comment