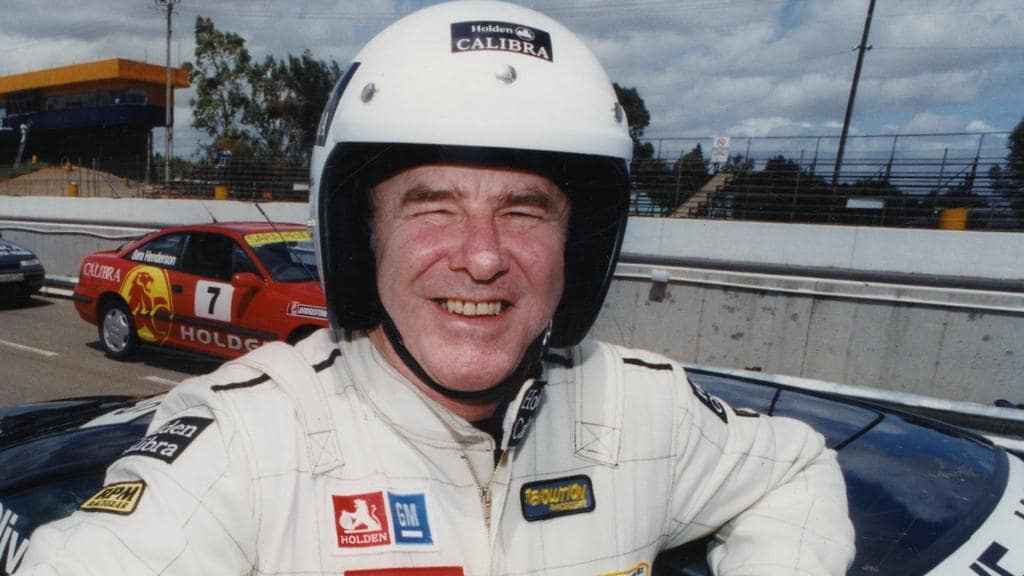

Clive James, possibly Formula One's most sarcastic of BBC commentators. A legend of letters who charmed generations.

Author, poet, TV host, critic, lyricist and occasional toady, expat legend Clive James had so much to be immodest about, writes James Campbell.

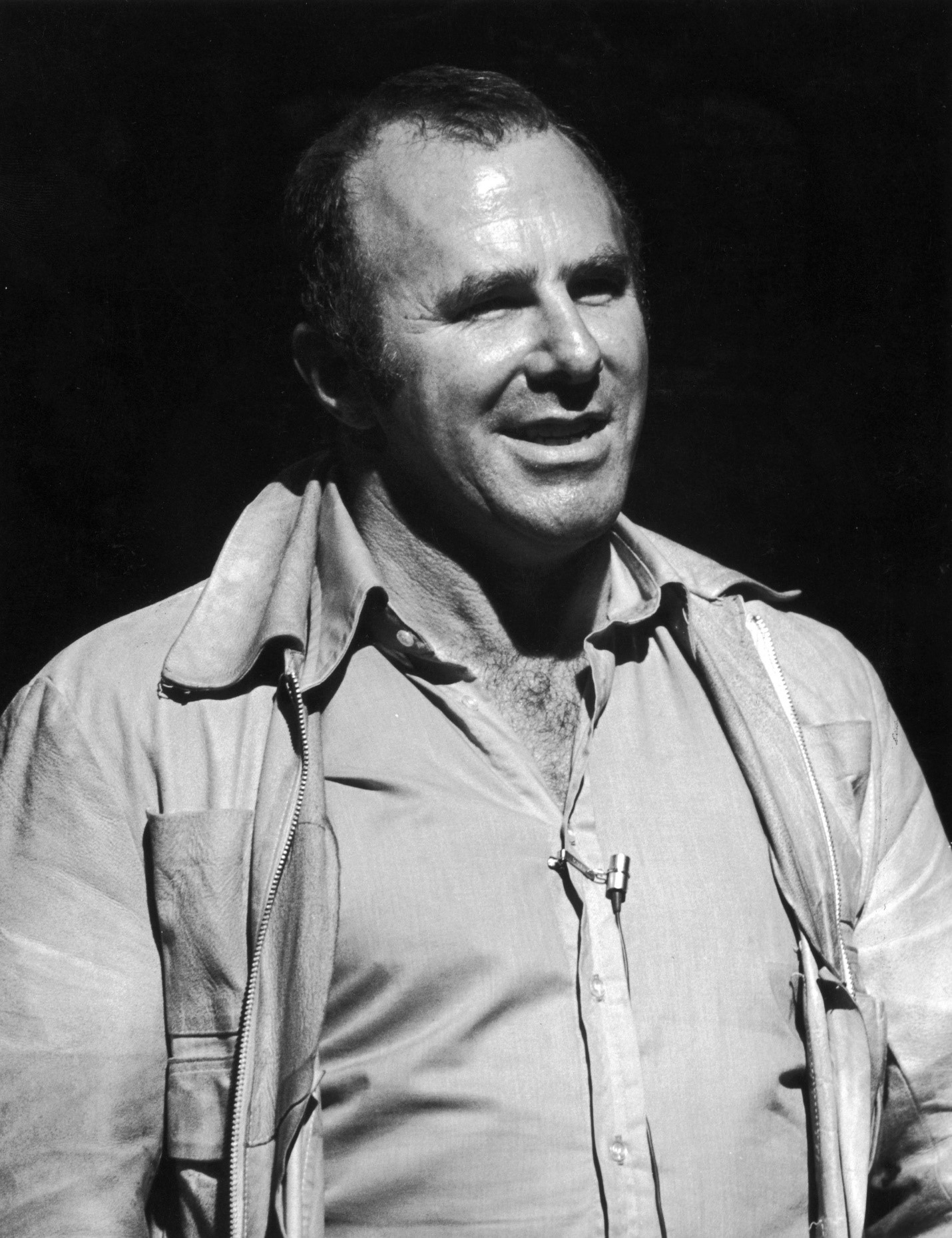

Clive James, 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019, was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster and writer who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019. He began his career specialising in literary criticism before becoming television critic for The Observer in 1972, where he made his name for his wry, deadpan humour.

During this period, he earned an independent reputation as a poet and satirist. He achieved mainstream success in the UK first as a writer for television and eventually as the lead in his own programmes, including... on Television.

James was born Vivian Leopold James in Kogarah, a southern suburb of Sydney. He was allowed to change his name as a child because "after Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O'Hara, the name became irrevocably a girl's name no matter how you spelled it". He chose "Clive", the name of Tyrone Power's character in the 1942 film This Above All.

James's father, Albert Arthur James, was taken prisoner by the Japanese during World War II. Although he survived the prisoner-of-war camp, he died when the American B-24 carrying him and other freed allied POWs ran into the tail of a typhoon en route from Okinawa to Manila and crashed into the mountains of southeastern Taiwan. He was buried at Sai Wan War Cemetery in Hong Kong. James would later state that his life's works originated in his father's death.

James, an only child, was brought up by his mother (Minora May, née Darke), a factory worker, in the Sydney suburbs of Kogarah and Jannali, living some years with his English maternal grandfather.

He was educated at Sydney Technical High School (despite winning a bursary award to Sydney Boys High School) and the University of Sydney, where he studied English and psychology from 1957 to 1960 and became associated with the Sydney Push, a libertarian intellectual subculture. At the university, he contributed to the student newspaper, Honi Soit, and directed the annual students' union revue. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in English in 1961. After graduating, James worked for a year as an assistant editor for the magazine page at The Sydney Morning Herald.

In 1962, James moved to England, which became his home for the rest of his life. During his first three years in London, he shared a flat with the Australian film director Bruce Beresford (disguised as "Dave Dalziel" in the first three volumes of James's memoirs), was a neighbour of Australian artist Brett Whiteley, became acquainted with Barry Humphries (disguised as "Bruce Jennings") and had a variety of occasionally disastrous short-term jobs – sheet metal worker, library assistant, photo archivist and market researcher.

James gained a place at Pembroke College, Cambridge, to read English literature. While there, he contributed to all the undergraduate periodicals, was a member and later President of the Cambridge Footlights and appeared on University Challenge as captain of the Pembroke team, beating St Hilda's, Oxford, but losing to Balliol on the last question in a tied game.

During one summer vacation, he worked as a circus roustabout to save enough money to travel to Italy. His contemporaries at Cambridge included Germaine Greer (known as "Romaine Rand" in the first three volumes of his memoirs), Simon Schama and Eric Idle. Having, he claimed, scrupulously avoided reading any of the course material (but having read widely otherwise in English and foreign literature), James graduated with a 2:1—better than he had expected—and began a PhD thesis on Percy Bysshe Shelley.

James became the television critic for The Observer in 1972, remaining in the role until 1982. Mark Lawson described a James review as "so funny it was dangerous to read while holding a hot drink". He was at times merciless. Selections from the column were published in three books – Visions Before Midnight, The Crystal Bucket and Glued to the Box – and finally in a compendium, On Television. He wrote literary criticism for newspapers, magazines and periodicals in Britain, Australia and the United States, including, among many others, the Australian Book Review, The Monthly, The Atlantic, The New York Review of Books, The Liberal and The Times Literary Supplement. John Gross included James's essay "A Blizzard of Tiny Kisses" in the Oxford Book of Essays (1992, 1999).

The Metropolitan Critic (1974), his first collection of literary criticism, was followed by At the Pillars of Hercules (1979), From the Land of Shadows (1982), Snakecharmers in Texas (1988), The Dreaming Swimmer (1992), Even As We Speak (2004), The Meaning of Recognition (2005) and Cultural Amnesia (2007), a collection of miniature intellectual biographies of over 100 significant figures in modern culture, history and politics. A defence of humanism, liberal democracy and literary clarity, the book was listed among the best of 2007 by The Village Voice. Another volume of essays, The Revolt of the Pendulum, was published in June 2009.

He also published Flying Visits, a collection of travel writing for The Observer. For many years, until mid-2014, he wrote the weekly television critique page in the "Review" section of the Saturday edition of The Daily Telegraph.

James published several books of poetry, including Poem of the Year (1983), a verse-diary; Other Passports: Poems 1958–1985, a first collection; and The Book of My Enemy (2003), a volume that takes its title from his poem "The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered".

He published four mock-heroic poems – The Fate of Felicity Fark in the Land of the Media: a moral poem (1975), Peregrine Prykke's Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World (1976), Britannia Bright's Bewilderment in the Wilderness of Westminster (1976) and Charles Charming's Challenges on the Pathway to the Throne (1981) – and one long autobiographical epic, The River in the Sky (2018).

During the 1970s he also collaborated on six albums of songs with Pete Atkin.

Atkin and James toured together to promote both the final album – a "contractual obligation" collection consisting of parodies and humour numbers written over the years - and James's own Felicity Fark epic poem. James wrote the album sleeve notes, which mostly linked the songs with thinly disguised jibes at popular artists and trends. On stage James both read from his poem and introduced the album songs. Despite the success of the tour, there were no more recordings by Atkin, who pursued other opportunities and eventually became a BBC radio producer.

A revival of interest in the songs in the late 1990s, triggered largely by the creation by Steve Birkill of an Internet mailing list "Midnight Voices" in 1997, led to the reissue of the six albums on CD between 1997 and 2001, as well as live performances by the pair. A double album of previously unrecorded songs written in the seventies and entitled The Lakeside Sessions: Volumes 1 and 2 was released in 2002 and Winter Spring, an album of new material written by James and Atkin was released in 2003. This was followed by Midnight Voices, an album of remakes of the best Atkin/James songs from the early albums and, in 2015, by The Colours of the Night, which included several newly completed songs.

James acknowledged the importance of the Midnight Voices group in bringing to wider attention the lyric-writing aspect of his career. He wrote in November 1997, "that one of the midnight voices of my own fate should be the music of Pete Atkin continues to rank high among the blessings of my life".

In 2013, he issued his translation of Dante's Divine Comedy. The work, adopting quatrains to translate the original's terza rima, was well received by Australian critics. Writing for The New York Times, Joseph Luzzi thought it often failed to capture the more dramatic moments of the Inferno, but that it was more successful where Dante slows down, in the more theological and deliberative cantos of the Purgatorio and Paradiso.

In 1980 James published his first book of autobiography, Unreliable Memoirs, which recounted his early life in Australia and extended to over 100 reprintings. It was followed by four other volumes of autobiography: Falling Towards England (1985), which covered his London years; May Week Was in June (1990), which dealt with his time at Cambridge; North Face of Soho (2006); and The Blaze of Obscurity (2009), concerning his subsequent career as a television presenter. An omnibus edition of the first three volumes was published under the generic title of Always Unreliable. James also wrote four novels: Brilliant Creatures (1983); The Remake (1987); Brrm! Brrm! (1991), published in the United States as The Man from Japan; and The Silver Castle (1996).

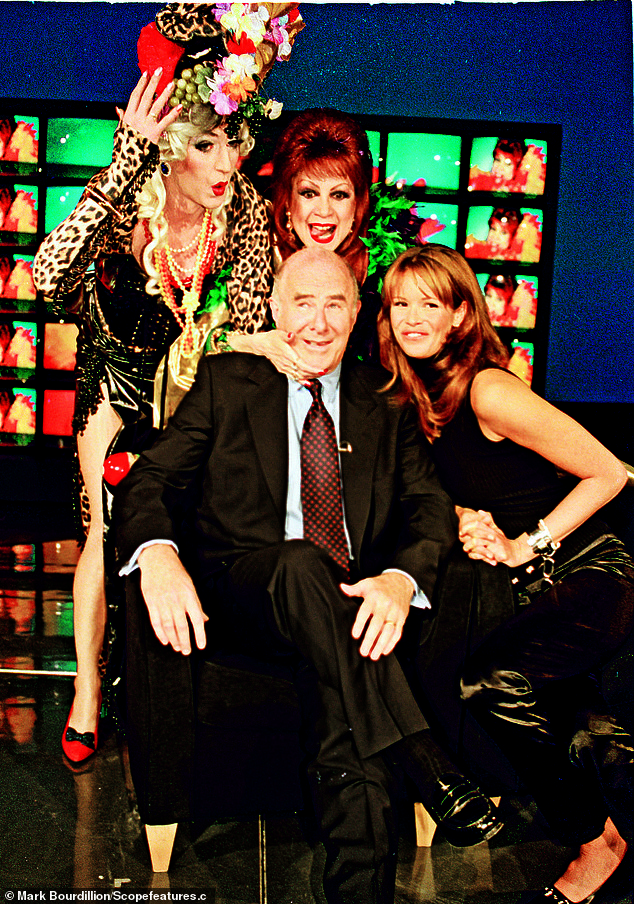

Clive James in 1996 with Australian supermodel Elle Macpherson, right, drag queen Paul O'Grady as Lily Savage and Margarita Pracatan.

In 1999, John Gross included an excerpt from Unreliable Memoirs in The New Oxford Book of English Prose. John Carey chose Unreliable Memoirs as one of the 50 most enjoyable books of the 20th century in his book Pure Pleasure (2000).

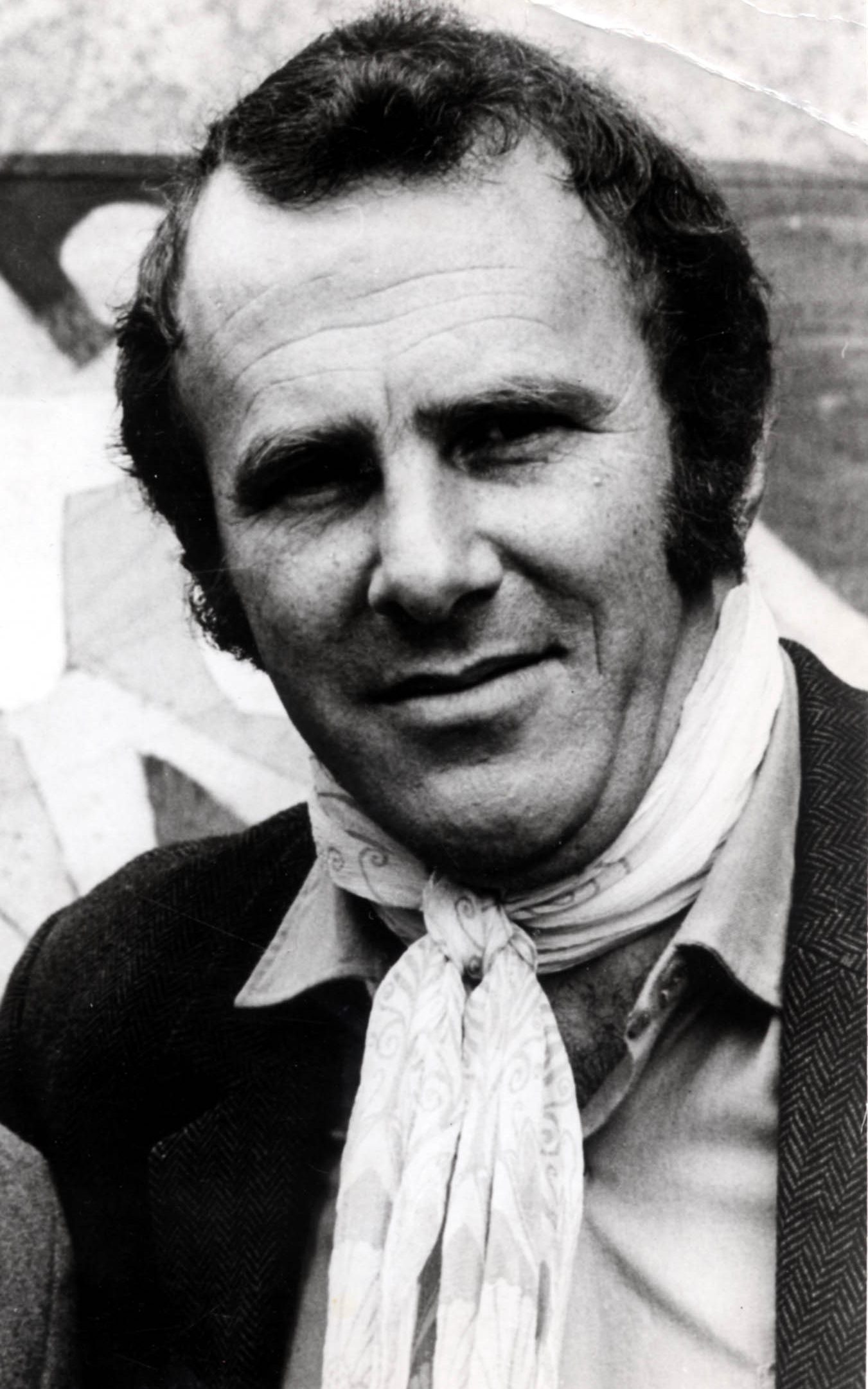

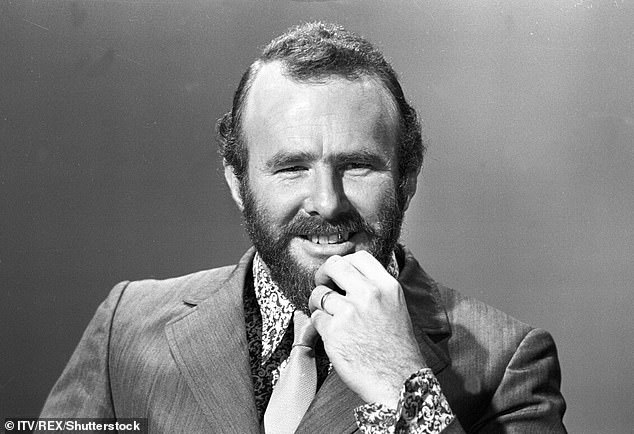

Clive in 1976 on the Granada pop music show 'So It Goes'. Credit Getty Images.

James developed his television career as a guest commentator on various shows, including as an occasional co-presenter with Tony Wilson on the first series of So It Goes, the Granada Television pop music show. On the show when the Sex Pistols made their TV debut, James commented: "during the recording, the task of keeping the little bastards under control was given to me. With the aid of a radio microphone, I was able to shout them down, but it was a near thing... they attacked everything around them and had difficulty in being polite even to each other".

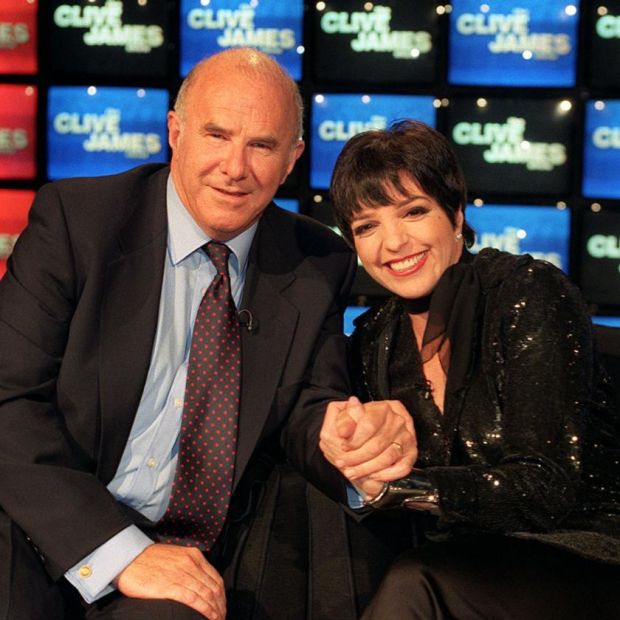

Photo dated 21.06.1996 of Liza Minnelli with interviewer Clive James for the recording of the Clive James Show.

In 1995 he set up Watchmaker Productions to produce The Clive James Show for ITV and a subsequent series launched the British career of singer and comedian Margarita Pracatan. James hosted one of the early chat shows on Channel 4 and fronted the BBC's Review of the Year programmes in the late 1980s (Clive James on the '80s) and 1990s (Clive James on the '90s), which formed part of the channel's New Year's Eve celebrations.

In the mid-1980s, James featured in a travel programme called Clive James in... (beginning with Clive James Live in Las Vegas) for LWT (now ITV) and later switched to BBC, where he continued producing travel programmes, this time called Clive James's Postcard from... (beginning with Clive James's Postcard from Miami) – these also eventually transferred to ITV. He was also one of the original team of presenters of the BBC's The Late Show, hosting a round-table discussion on Friday nights.

Clive James and Emma Thompson at the launch BBC1's line up of programmes. Image PA Wire.

His major documentary series Fame in the 20th Century (1993) was broadcast in the United Kingdom by the BBC, in Australia by the ABC and in the United States by the PBS network. This series dealt with the concept of "fame" in the 20th century, following over a course of eight episodes (each one chronologically and roughly devoted to one decade of the century, from the 1900s to the 1980s) discussions about world-famous people of the 20th century. Through the use of film footage, James presented a history of "fame" which explored its growth to today's global proportions. In his closing monologue he remarked, "achievement without fame can be a rewarding life, while fame without achievement is no life at all."

Clive also participated as a contestant on the 42nd episode of Japanese game show Takeshi's Castle and made a short documentary about it.

A well known fan of motor racing, James presented the 1982, 1984 and 1986 official Formula One season review videos produced by the Formula One Constructors Association, more commonly known as FOCA. James, who attended most F1 races during the 1980s and was a friend of former FOCA boss Bernie Ecclestone, added his own humour to the reviews which became popular with fans of the sport. He also presented The Clive James Formula 1 Show for ITV to coincide with their Formula One coverage in 1997.

He summed up the medium in the introduction to Glued to the Box: "anyone afraid of what he thinks television does to the world is probably just afraid of the world."

In 2007, James started presenting the BBC Radio 4 series A Point of View, with transcripts appearing in the "Magazine" section of BBC News Online. In this programme James discussed various issues with a slightly humorous slant.

In October 2009, James read a radio version of his book The Blaze of Obscurity on BBC Radio 4's Book of the Week programme. In December 2009, James talked about the P-51 Mustang and other American fighter aircraft of World War II in The Museum of Curiosity on BBC Radio 4.

In May 2011, the BBC published a new podcast, A Point of View: Clive James, which features all sixty A Point of View programmes presented by James between 2007 and 2009.

He posted vlog conversations from his internet show Talking in the Library, including conversations with Ian McEwan, Cate Blanchett, Julian Barnes, Jonathan Miller and Terry Gilliam. In addition to the poetry and prose of James himself, the site featured the works of other literary figures such as Les Murray and Michael Frayn, as well as the works of painters, sculptors and photographers such as John Olsen and Jeffrey Smart.

In 2008 James performed in two eponymous shows at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe: Clive James in Conversation and Clive James in the Evening. He took the latter show on a limited tour of the UK in 2009.

He famously described Arnold Schwarzenegger, in his bodybuilding days, as looking like "a brown condom full of walnuts".

He described the romantic novelist Barbara Cartland as having "twin miracles of mascara, her eyes looked like the corpses of two small crows that had crashed into the white cliffs of Dover." He also used to call the Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat by the female name "Yasmin Arafat".

The origins of his famous remark "whoever called snooker 'chess with balls' was rude but right" are set out by Edward Winter in his article "Clive James and Chess".

Clive James with Jerry Hall at the BAFTA Awards, 1990.

In 1992, James was made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM). This was enhanced to Officer level (AO) in the 2013 Australia Day Honours. James was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2012 New Year Honours for services to literature and the media. In 2003 he was awarded the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal for Literature. He received honorary doctorates from the Universities of Sydney and East Anglia. In April 2008, James was awarded a Special Award for Writing and Broadcasting by the judges of the Orwell Prize.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2010. He was an Honorary Fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge (his alma mater). In the 2015 BAFTAs, James received a special award honouring his 50-year career. In 2014, he was awarded the President's Medal by the British Academy.

James is celebrated with a plaque on the Sydney Writers Walk on Circular Quay. It includes an excerpt on Sydney Harbour from Unreliable Memoirs.

Describing religions as "advertising agencies for a product that doesn't exist", James was an atheist and saw it as the default and obvious position.

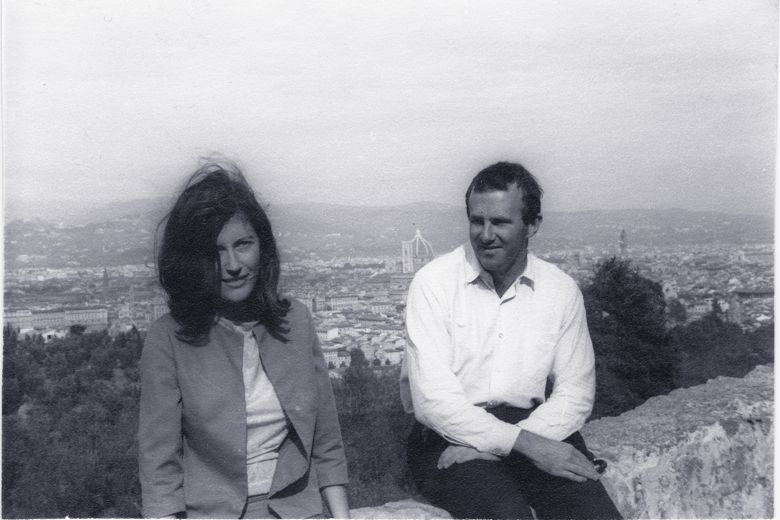

Prue Shaw and Clive James in Florence 1966.

In 1968, at Cambridge, James married Prudence A. "Prue" Shaw, an emeritus reader in Italian studies at University College London and the author of Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity. James and Shaw had two daughters, one the artist Claerwen James. In April 2012, the Australian Channel Nine programme A Current Affair ran an item in which the former model Leanne Edelsten admitted to an eight-year affair with James beginning in 2004. Shaw evicted her husband from the family home following the revelation. Prior to this, for most of his working life, James divided his time between a converted warehouse flat in London and the family home in Cambridge.

After the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, James wrote a piece for The New Yorker entitled "Requiem", recording his overwhelming grief. From then he mainly declined to comment about their friendship, apart from some remarks in his fifth volume of memoirs, Blaze of Obscurity.

James was able to read, with varying fluency, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Russian and Japanese. A tango enthusiast, he travelled to Buenos Aires for dance lessons and had a dance floor in his house.

James was a lifelong fan of the St George Dragons and wrote admiringly of Rugby League Immortal Reg Gasnier who was a schoolmate at Sydney Technical High School. He guest presented one episode of The Footy Show in 2005.

For much of his early life, James was a heavy drinker and smoker. He recorded in May Week Was in June his habit of filling a hubcap ashtray daily. At various times he wrote of attempts – intermittently successful – to give up drinking and smoking. He smoked 80 cigarettes a day for a number of years before giving up in 2005. He had also given up, for 13 years, from his early 30s.

In April 2011, after media speculation that he had suffered kidney failure, James confirmed in June 2012 that B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia "had beaten him" and that he was "near the end". He said that he was also diagnosed with emphysema and kidney failure in early 2010.

On 3 September 2013, an interview with journalist Kerry O'Brien, Clive James: The Kid from Kogarah, was broadcast by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. The interview was filmed in the library of his old college at Cambridge University. In the extended interview, James discussed his illness and confronting mortality. James wrote the poem "Japanese Maple" which was published in The New Yorker in 2014 and described as his "farewell poem". The New York Times called it "a poignant meditation on his impending death".

In a BBC interview with Charlie Stayt, broadcast on 31 March 2015, James described himself as "near to death but thankful for life". In October 2015, he admitted to feeling "embarrassment" at still being alive thanks to experimental drug treatment.

Until June 2017, he wrote a weekly column for The Guardian entitled "Reports of My Death...".

James died on 24 November 2019 at his home in Cambridge.

Clive James. At the Austrian grand prix on Sunday, the leader, Rubens Barrichello, was ordered to pull over to let his team-mate, Michael Schumacher, win the race. Ferrari said it was to guarantee them the championship, but the fans booed in disgust and the German looked embarrassed. Here, a lifelong enthusiast of formula one explains why he won't be watching any more. Tue 14 May 2002.

If the wheels can come off an empire, they came off Bernie Ecclestone's formula-one empire in Austria on Sunday, when Rubens Barrichello, under team orders from Ferrari, slowed down to let Michael Schumacher take the win. A zillion petrol-heads all over the world were thus given an unmistakable television signal that they might as well have been reading the business section of their local newspaper. The fix was in.

The bottom line and the finishing line had revealed themselves as being identical. The chequered flag was a cheque book. As a writer by profession, I resorted naturally to word-associations for the expression of my outrage. Elsewhere in the audience, there was probably a circus performer in Singapore who threw knives at his wife, a removal man in Auckland who heaved a chest of drawers out of his attic window. How apt, I exclaimed to one of my study walls full of strangely noncommittal books, that the stitch-up should have taken place on a circuit called the Spielberg. Ideally, a racing circuit should be called the Hitchcock, to convey suspense. But when they're racing on the Spielberg, a blockbuster production devotes a mountainous investment to a predictable materialistic outcome with a spiritual quotient the size of mouse. My metaphors became ever more mixed, the books ever more aloof, scared by the spectacle of homicidal fervour from a man who had previously confined his passion to fingering their spines. Far away in Vancouver or perhaps Valletta, a dog breeder was filling a bucket of water in his bathroom.

For many years now, the circus performer, the removal man, the dog breeder and I have all been united by our propensity to rearrange any schedule so that we can be seated before the television set to watch the latest grand prix. All of us might have been racing drivers in a different life. Circumstances having dictated otherwise, we are willing to let other men do the driving for us. Admittedly, they have unfair advantages, these others: they are younger than us, better looking and they combine a flat stomach, sensitive fingers, unflinching valour and an enormous salary into a sexual signal that few fashion models can resist. The injustice cries to heaven, which gives no answer. But we are content to let it happen. Let these gifted children race for us: as long as they race.

Most of the time they do and there is none of them who is not admirable for his bravery alone, quite apart from his skill. Mainly owing to the tireless efforts of Jackie Stewart, grand prix racing has become much safer than it was when I started following it, but it is still a lot more dangerous than writing. Takuma Sato could easily have been killed last Sunday when he was side-swiped and Juan Pablo Montoya was only a split second from being decapitated in the same accident. The cars are very strong in the cockpit area nowadays, but a high-speed impact against the wall can still do to a driver what it would do to an egg in a steel box, no matter how tightly the box fitted. Ayrton Senna was killed that way, Mika Hakkinen almost was and the carbon-fibre front end was only a partial protection for Schumacher's legs when he sailed across the gravel trap and smacked the tyre wall at Silverstone. It was probably the fresh memory of that incident which helped to persuade the Ferrari management that they should stack up the championship points for him while they could, even at the expense of disappointing the watching world and painfully reminding Barrichello that his newly extended contract carried a price in enforced humility. Schumacher has a big say in what the Ferrari team does. He ought to: if they are on top now, it is because he put them there and he did it with his practical wisdom as well as with his supernatural flair. If he shared in the Spielberg decision through patching into a conference call from the radio in his car, he, too, was probably remembering Silverstone. Brave by nature, as they all are, he would have been more likely to recall what happened to his season than what happened to his leg. I would have remembered the leg. Johnny Herbert had his career ruined by smashed legs; Jacques Laffite had his career ended by them; and Alessandro Zanardi actually lost them. I, however, am not Michael Schumacher.

No, you're not, says the devil in my ear and it's because you're a human being. But the devil is a casuist as always. Admittedly, Michael Schumacher is an easy man to dislike. It was especially unfortunate for him that the driver he stole the victory from on Sunday was the hardest man to dislike in formula one. Rubens Barrichello, a cuddly toy already nicely padded under his padded suit, is the top half of Kelsey Grammer with a nervous smile to match. Nobody so quick was ever so cute. But Schumacher gives the air of having arrived at ordinary affability only by hard study and the mask - modelled in rubberised plaster by Arno Breker as an archetype of Aryan manhood in a rare benevolent mood - is always apt to slip. He is a natural sporting hero, but sportsmanship is not his natural mode. Let us not, however, distract ourselves with a glib antipathy. Sportsmanship is not the natural mode of formula one.

It might be, if it was just the drivers racing each other. But the manufacturers are racing each other too and there's the rub. Whatever way the formula is readjusted, a few manufacturers will each produce a car decisively faster than the rest of the pack, even if their respective cars are only fractionally faster or slower than each other. But the cost of producing a competitive car is so enormous that none of the top manufacturers can protect its investment for long unless it has a champion, or at least a championship contender. The best drivers are attracted to the best teams. So instead of the contenders being spread evenly through the field - as they might be through an equivalent of the draft-pick system in American football - they are quite likely to end up two to a team. Theoretically, the sharpest competitive edge in F1 racing is between the two team members; and indeed this might be so; but only if the team allows them to race each other. Unfortunately, it is in the team's interest to allow only the opposite, so that the prospective champion is placed out of danger from his closest rival.

Effectively, this has been true of modern grand prix racing since the beginning. When Mercedes-Benz made its postwar comeback, it had a car that nothing else could touch. Juan-Manuel Fangio was signed to come first, Stirling Moss to come second; and that's the way the game played out, even if Fangio loftily ceded Moss the British grand prix as a consolation prize. (To prove it was a gesture, Fangio trailed Moss over the finish line by only a few inches. To prove he was accepting a poisoned chalice, Barrichello, poor mite, did the same at Spielberg.) If they had really been racing, Moss might have given Fangio a proper fight in every race on the calendar. But it never happened except in our dreams. Team orders prevailed. As Richard Williams pointed out in the Guardian yesterday, team orders prevailed again in 1958, when Phil Hill handed Mike Hawthorn the last race of the season and the championship along with it. When Mario Andretti and Ronnie Peterson were both driving for Lotus, the fix was blatant. Peterson was at least as fast as Andretti and sometimes needed all his skill to come second: he was treading on the brakes while Andretti was treading on the accelerator. In a later period at Lotus, Ayrton Senna, then clearly on his way to supremacy, refused to have Derek Warwick as second driver because Warwick might have been a contender and Senna thought the team lacked the wherewithal to support two contenders. Senna was probably right, but I remember the way Warwick's wife said Senna's name at a restaurant near Monza on the evening before Warwick went out to race in the slower car to which Senna's realism had condemned him.

Before his untimely death canonised him, Senna's realism was commonly called ruthlessness by everyone in the sport. To a certain extent it was: when he figured out that he would become champion if Prost could be removed from the track, he accomplished this by driving into Prost, thereby removing himself as well, but with the championship in the bag. He engineered the impact straight after doing the sums in his head, thus setting a bad precedent. Such behavior brought formula one close to being a demolition derby, but it was a natural consequence of a team's readiness to back up its top man, even if his conscience-free behavior was at the expense of its second man. More recently, tighter rules have made the deliberate shunt harder to pull off, but as with the professional foul in football, the spirit of the thing is hard to quench.

This depressing realpolitik comes with the financial commitment of the top marques: they can't afford anything less. Unfortunately, we petrol-heads are on their side. We don't want an Americanised version of the sport. In American motor racing, all the cars are effectively the same and thus run beside each other, to the delight of the American audience, which, although not dumb, as it is often painted, certainly likes things simple. But out here in the undeveloped world - ie everywhere except America - we like the complications of formula one and so do bright new-world refugees such as Juan Pablo Montoya. Montoya follows in the tradition of Mario Andretti and Jacques Villeneuve: charioteers in standardised cars who had fun racing wheel to wheel in America, but came over to formula one because it was more interesting. And indeed the interest of formula one is enormous: the leading manufacturers, interpreting the formula to its optimum, come up with machines so precisely attuned to the task that the full distance is as far as they can run before they fall apart while being measured by the scrutineers. Petrol-heads all over the planet bore their friends and families helpless with details of the technology before being left alone in front of the piece of technology that eventually generates the cashflow for the whole adventure: the television set.

Rarely does it provide a thrilling spectacle. Apart from the occasional shunt, it mainly shows you a procession. But to the fan, the questions are endless, convoluted and enthralling. Can the driver of the car that is a second slower make up the difference? Montoya almost can, but Schumacher either knows how to get another second of supremacy out of the Ferrari engineers or else he is driving faster than ever. It is all, inherently, fascinating. Unfortunately, it is also all as boring as hell. Schumacher and Montoya won't be racing wheel to wheel unless their cars are identical in performance and at the moment Montoya's Williams is a second down. The only people racing wheel to wheel will be the two drivers of the quickest marque, because their cars are identical in all respects. And if the championship is at stake, the fix will go in.

As things stand, Ferrari, Schumacher and Barrichello will go before motor racing's governing body, the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile, on June 26, for the Spielberg production to be investigated and solemnly ruled upon. It will be a date in the annals of fatuity. First of all, there can be no doubt about what happened. Second, formula one is ruled by Bernie Ecclestone. He invented it and it's all his. On the whole he has done a brilliant job. He rules a community richer than most small countries; nobody gets hurt except volunteers and he diverts hundreds of millions of people across the globe, thus fully justifying the hundreds of millions of pounds he diverts into his own pocket. There is nothing Bernie can't arrange. It was a wonder that he confined himself to slipping the Labour party a mere million. Nobody who has ever met him would have been surprised if Cherie Blair had started smoking two packs of Silk Cut Extra Mild every day in public. But now he has to arrange something more challenging and pronto. Formula one is in the toilet and looks even more obscene because the toilet is made of gold. The only cure is to outlaw team orders. The circus performer, the removal man, the dog breeder and I can all just about stand watching two cars the same colour coming first and second. It's the reward for technical achievement. But if their drivers aren't racing each other, there is no reason to watch at all. For the next grand prix, the huge worldwide television audience will be down by at least one name I can vouch for. Anyone who feels like joining me can register his protest the same way I will. It can be done at the touch of a button. You can bet that the man in question will get the message. It's a boycott, Bernie: either the racers race, or I read my books instead of shouting at them.

My 8-year affair with TV host Clive James by ex-model. He called her Little Red Riding Hood, she called him Big Bad Wolf. And that was just one of the secrets a blonde ex-model revealed yesterday about her alleged affair with 73-year-old TV presenter Clive James. By Padraic Flanagan. Published: Tue, Apr 24, 2012.

Ex-model Leanne Edelsten in a shot from the TV show as she confronts Clive James in London.

Australian socialite Leanne Edelsten, 25 years younger than Mr James, claimed the pair had been having a relationship for eight years.

“I’ve been in love for a very long time,” she said during an interview in a prime-time show on Australia’s Channel 9. “We had an instant attraction. It was our secret.”

The alleged affair helped bring an end to Mr James’s 44-year marriage, it was claimed, after his wife learned of his adultery when she came across suggestive emails and photos the lovers had exchanged.

The writer and critic – who became a household name in the 1980s by poking fun at foreign TV shows – was said to have been shunted from his marital home in Cambridge to a dingy basement apartment in the city.

Footage aired during the TV interview showed Miss Edelsten confronting Mr James in a London street, showing him a number of sexy photographs she had sent to him.

During the ambush by the camera crew, which left Mr James rattled and confused, she asked how the raconteur’s wife, academic Prue Shaw, had got hold of the pictures.

Miss Edelsten expressed no remorse for her actions and even suggested she would continue the affair.

She said romance blossomed between the unlikely couple when they met in a Sydney restaurant in 2004 at a point when she was involved in a break-up with her second husband, a barrister with whom she had two daughters.

She told viewers: “I said ‘I’m getting divorced’ and he said ‘Excellent’. He then proceeded to get up from the table and literally ravish me.”

Miss Edelsten said that moment led to the couple communicating with each other by their pet names – she referred to Mr James as Mr Wolf because of the way he ravaged her.

She said that he had seduced her by reciting Shakespeare and they had bedroom rituals of consuming tea and a Cherry Ripe, an Australian chocolate bar.

“I don’t know whether it’s got to do with experience, intelligence,” said Miss Edelsten, 48. “But he’d leave men half his age for dead.”

“If there’s a poster boy for seniors’ week, he’s it. The guy’s a legend. He’s a prime example of ‘use it or lose it’ in every sense of the word.”

The couple kept in touch through emails, which included her sending him sexy photos of herself, she said.

They would meet every time he visited Australia. When he went back to the UK she sent him the photos, which he wanted, she said “because he was missing me”.

The model’s first husband, multi-millionaire Dr Geoffrey Edelsten, who was divorced from her in 1988, said he only heard of the alleged affair hours before the TV show. “It doesn’t surprise me,’’ said Dr Edelsten, 68, owner of Sydney Swans Australian rules football club, whose string of medical clinics collapsed when he went to jail for allegedly hiring a hit man to “deal with” a threatening client.

“Leanne proved to be an immoral, lying individual. I don’t think wrecking a marriage is something you should be celebrating on television.”

“People might say you made a bad choice (marrying her) then, but she was a different person. She’s changed enormously from the sweet young lady she was in the Eighties.”

The TV interview brought complaints in Australia that it should not have been screened because it showed Mr James as a confused old man.

Mr James, who has two grown-up daughters, was diagnosed with leukaemia two years ago. His agent declined to comment last night.

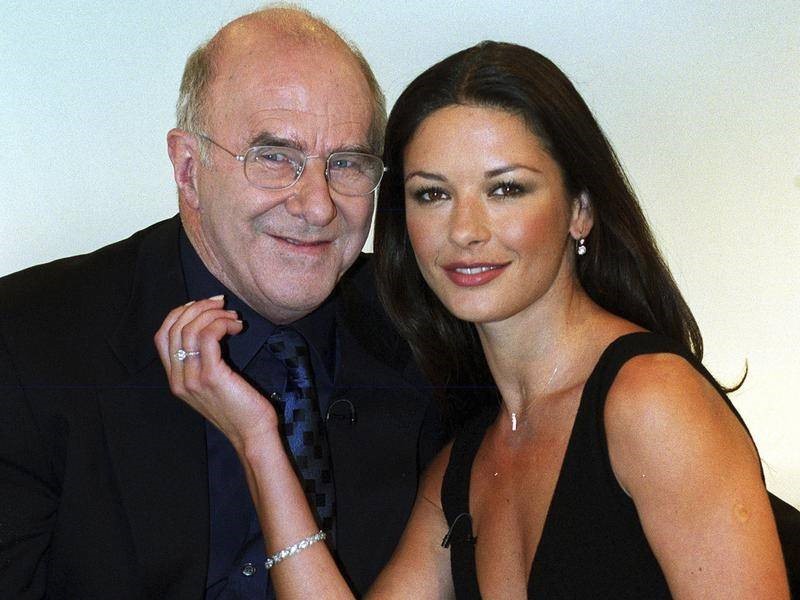

Clive James poses for a photo with actress Catherine Zeta-Jones in 1999.

Clive James: ‘my new wheelchair is a thing of beauty and precision.’ Saturday, 27 May 2017.

‘My wheelchair looked like a Ferrari from the heyday of the Mille Miglia.’ Photograph: Getty Images.

Some secret meeting of the women in my family must have concluded that the old man would not be doing much walking anymore, because early this week a wheelchair turned up at my house. It arrived in a big cardboard box. A mass of brown paper had to be removed. This once done, however, the contraption, even in disassembled form, was revealed as a thing of beauty and precision.

Once put together, it looked even better than that. It looked like a Ferrari from the heyday of the Mille Miglia. The deep crimson enamel of the tubular bodywork competed with the glittering silver of the spokes to dazzle the eye. It was a gorgeous beast. You could practically hear it growl and throb. Actually, it won’t be doing any of that, because it hasn’t got an engine, but the same people who had conspired to order it were already competing to get first push.

Perhaps they had spotted the implications of my geographical location. My back gate opens out on to the only real hill in Cambridge. My sector of the hill is only about 6ft high, but there is a distinct incline all the way to the river, into which I will plunge like a shot-up torpedo bomber unless firm control is maintained by my crew.

Clive James: ‘the Death Star is threatening me with a lethal dose of boredom.’

When my mechanics return from searching the shops for the proper black-and-yellow decals of a prancing horse, they can decide among themselves as to who gets first push. At the moment, my wife is ahead, because there is an appointment for a reception that we have been asked to attend together. The site of the venue is flat, so there is no danger of arriving at 80mph. On the other hand, steering the thing is no cinch. Yesterday, I was practising in the hallway and came to a doorway so narrow that I had to take my hands off the wheel rims. I did that too slowly, which is why I am now typing this with chopsticks held in my teeth.

Though my particular super-duper semi-Ferrari wheelchair would be hard to envision without modern materials, I imagine the actual concept of a self-propelled vehicle goes back to Leonardo da Vinci at least. Engineering, in many respects, is like art: an original concept hangs around for centuries while human ingenuity elaborates it out of recognition. Hence, some would say, poetry is still there even after it becomes so advanced that you can’t read it. In Australia, a professor of poetry has just told the world that questions of comprehensibility seem very minor when “seen in the perspective of the possibilities contained in poetry as it is and has been practised on the planet”. Well, I don’t suppose they practise it much on the moon.

Clive James on Formula 1 — a few highlights. Article 27 November 2019.

There are lots of things you could say about Clive James, whose death has been announced today. I remember seeing his TV shows as a child in the 1990s. Beyond that, Clive James was a prolific writer, poet and critic. I am qualified to comment on little of this.

But I was, of course, particularly drawn to his work in Formula 1. This makes up so little of his contribution to the world that most obituaries will probably not mention it. So here are a few of my favourite moments of his F1 commentary.

In the earliest days of Bernie Ecclestone’s Foca empire in the 1980s, Clive James narrated the official season review videos. His commentary was so acerbic, you can hardly believe it was official.

Here is his review of the 1982 Italian Grand Prix, in which he is rude about almost everyone involved, including Ferrari, Bernie Ecclestone and the then-Fisa president Jean-Marie Balestre.

Another notable moment is his description of the physical scuffle between Nelson Piquet and Eliseo Salazar at the 1984 German Grand Prix: “this could be the high point of Salazar’s career, so let’s see it again.”

Then there is the Clive James Formula 1 Show, shown by ITV ahead of their first race broadcast in 1997.

Here he interviews a wide selection of drivers from up and down the grid. His direct questions were often hilarious, but also telling: “Ukyo [Katayama], in your first Formula 1 season you had three shunts. In your second you had four. In your third, six; and in your fourth, seven. What are your plans for this season?”

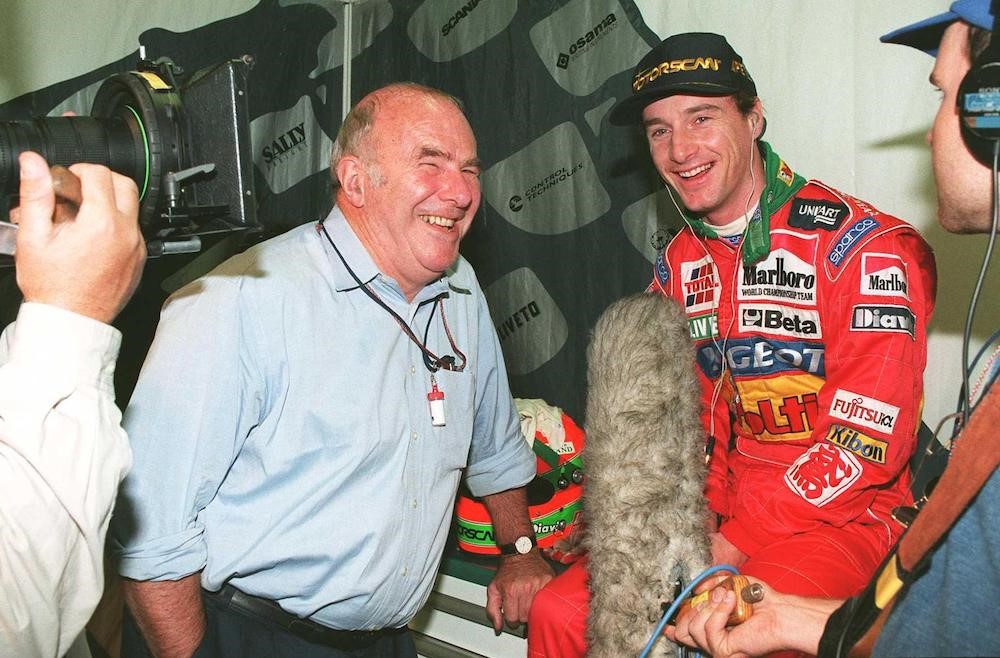

Clive James’ F1 show in Adelaide in 1995. By adelaidegp. November 28, 2019.

Writer and broadcaster Clive James was one of Australia’s most acclaimed exports, born in Sydney but living in the United Kingdom from 1961 until his passing in 2019 aged 80.

“The ‘Kid from Kogarah’, a prolific wordsmith with an acerbic intellect, colossal vocabulary and passion for poetry, always retained a fondness for his Australian heritage, despite five decades of British residency,” wrote the ABC.

James was a well-known motorsport fan, presenting and narrating the 1982, 1984 and 1986 official Formula 1 season review videos in addition to a number of documentaries and specials around the sport.

This included ‘The Clive James Grand Prix Show’, a behind-the-scenes documentary of the final Adelaide Grand Prix in 1995 that aired in 1996.

It provides a fascinating snapshot of the event, including a tense joint interview with rivals Michael Schumacher and Damon Hill, the paddock reaction to Mika Häkkinen’s near-fatal accident and a driver’s view of the weekend with Eddie Irvine (pictured above).

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment