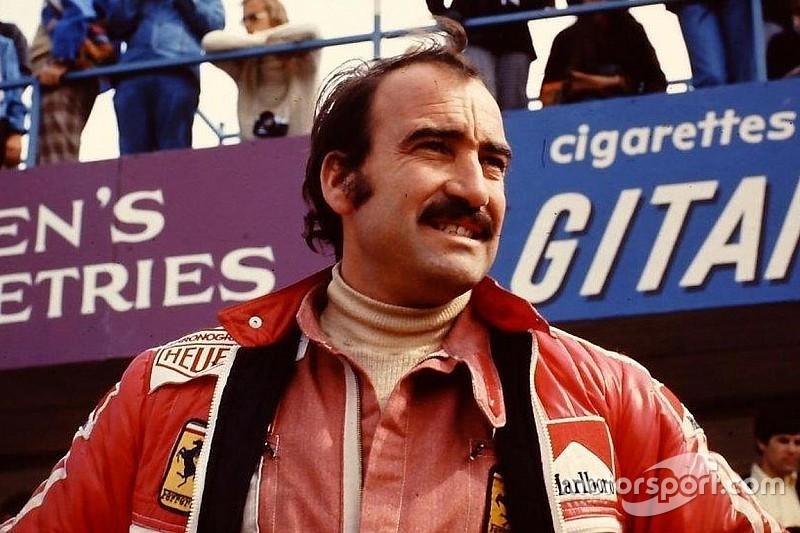

With those existentialist mustaches of his, that Gascon smile and that disarming bluntness, Clay Regazzoni was an unique and charismatic character. At Ferrari he was known as the last romantic. A giant of passion, speed a fatal attraction. There are those who tell of having gotten in the car with him only once and to have never repeated that mistake. Recklessness is part of his character as well as the series of accidents, two of which fatal. He may have never won a championship title in F1, but he is still considered one of the legends of the sport.

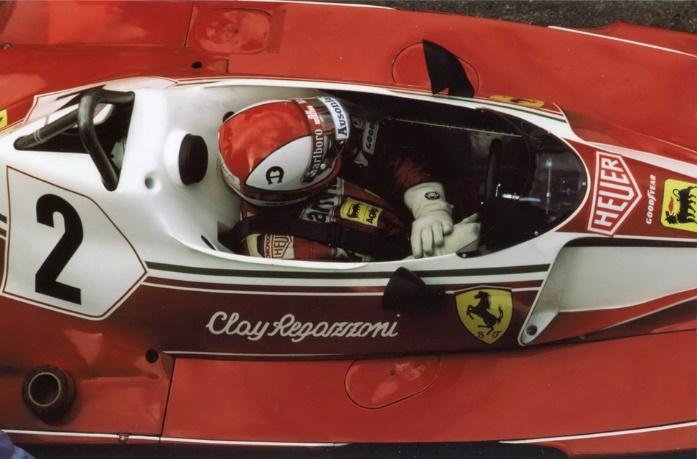

Gianclaudio Giuseppe Regazzoni (5 September 1939 – 15 December 2006), better known as Clay, competed in F1 races from 1970 to 1980, winning five GP, four of which with Ferrari (1970 Italian GP, 1974 German GP on the mythical circuit of old Nurburgring, 1975 Italian GP, 1976 US GP) and one with Williams. He has raced in a total of 132 F1 Grand Prix. He was born in Mendrisio, in Ticino Canton, part of the Italian speaking region of Switzerland, just a few days after the start of World War II. With a family originally from Bergamo, he was the son of Bruna and Pio.

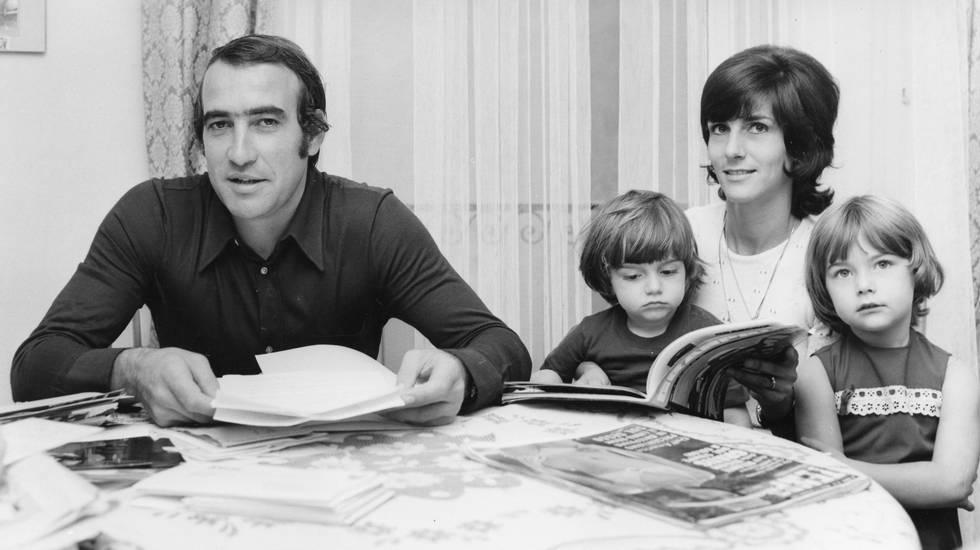

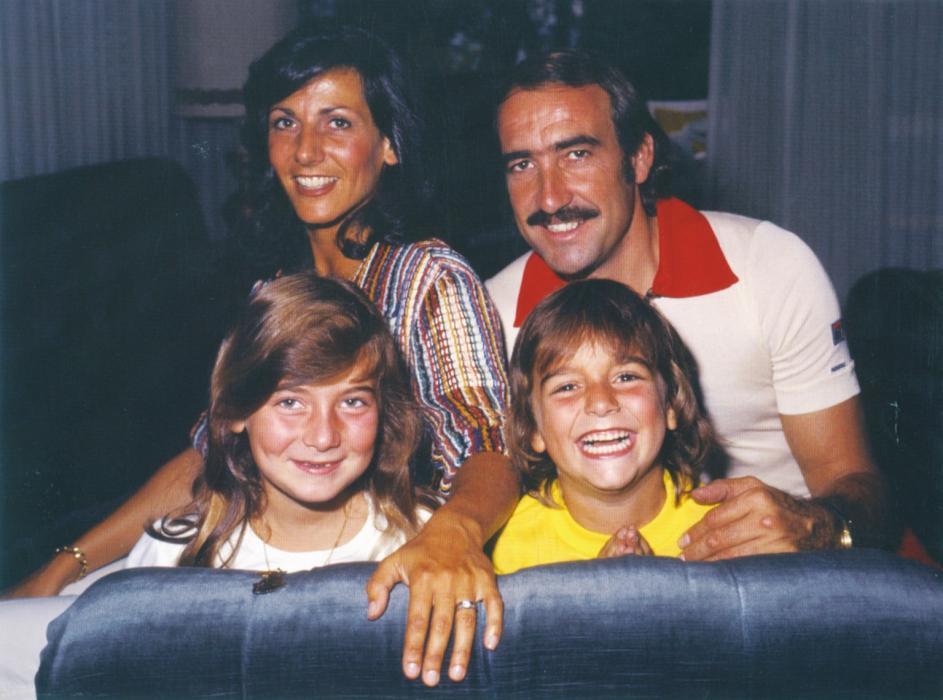

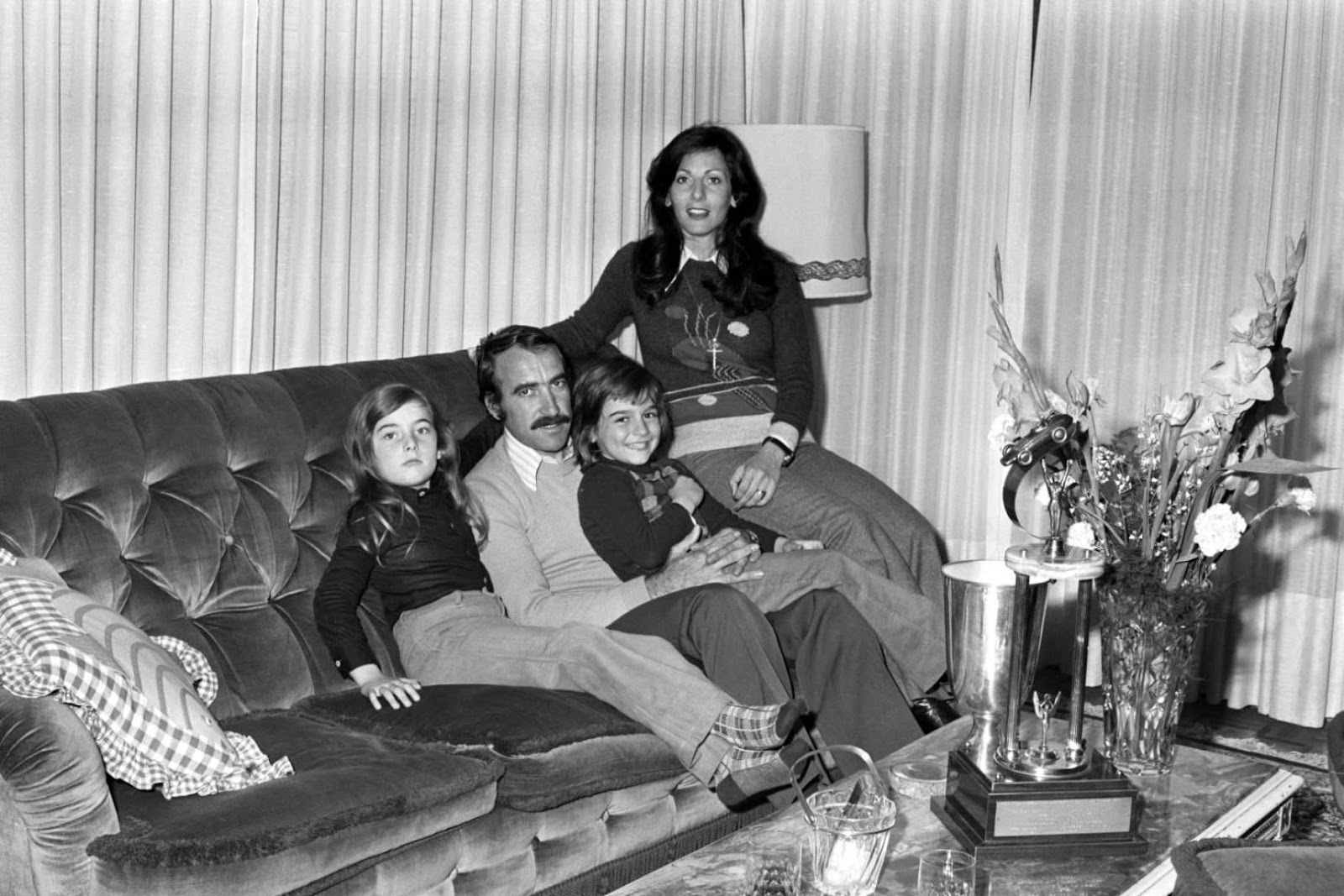

He grew up in Porza and was married to Maria Pia, with whom he had two children: Alessia and Gian Maria.

He first started competing in car races in 1963, at the comparatively late age of 24. Many of his early motorsport experiences were across the border in Italy, Switzerland having banned motor racing following the horrific accident at the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans race. He was driving in Formula 3 events during 1968 and, not for the last time, was lucky to survive a major accident. Exiting the chicane during the Monaco GP, he lost control of his car and collided heavily with the crash barrier. The diminutive size of the Formula 3 machine allowed it to pass under the rail, the sharp metal edge of the Armco slicing across the top of the open cockpit. He managed to duck down low enough in the driving seat for the rail to pass above him, missing his head by a tiny margin. The car eventually came to a halt when the roll hoop, behind his head and significantly lower than the top of his helmet, wedged itself underneath the barrier.

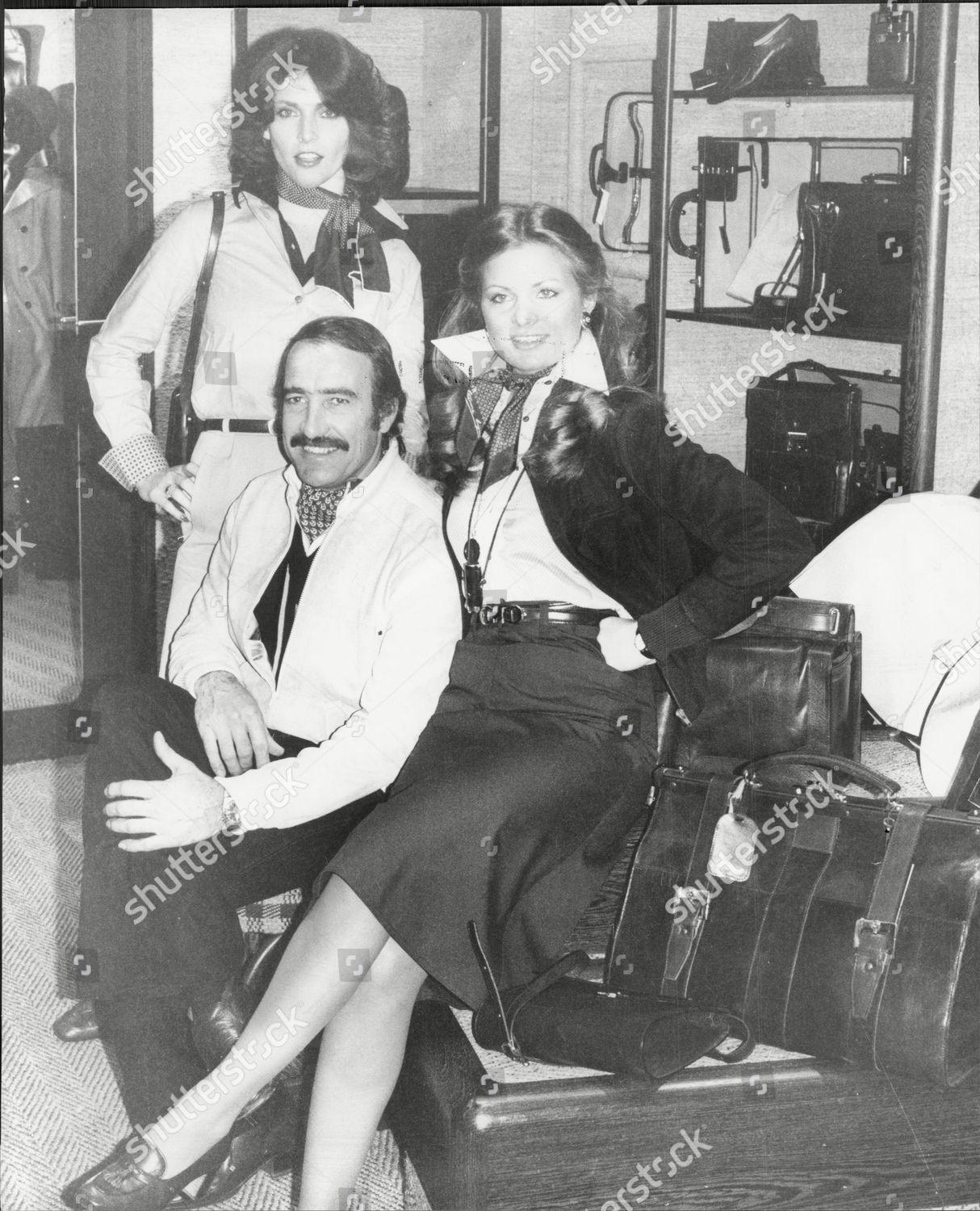

Clay Regazzoni with Arturo Merzario. Photo by Shutterstock.

As well as single seater racing, Regazzoni participated in sports car racing, including the 1970 “24 Hours of Le Mans” where he and Arturo Merzario raced a Ferrari 512S. However, the pair retired after completing only 38 laps. In his last year in Formula 2, he won the championship with Tecno and moved up to Formula 1.

Clay Regazzoni at Nurburgring in 1974.

Clay Regazzoni, Ferrari, at the 1974 United States Grand Prix.

Two 3 years stints at Ferrari (1970 – 1972 and 1974 – 1976), and scoring Williams's maiden GP victory are the clear highlights of his 10-year F1 career.

The relationship with the Prancing Horse (“compared to other F1 teams, Lauda said, Ferrari factory seemed like NASA, with that amazing track inch by inch monitored by closed-circuit TV, which allowed Enzo Ferrari (thanks to 10 fixed video systems) to observe, record and review a thousand times driver’s and car’s behavior in every metre of the circuit sitting comfortably in your armchair”) got off to a dream start when the Swiss driver took fourth on his debut in Holland, while there's nowhere better to take your maiden win in one of the red cars than Monza, which Regazzoni managed later that same year. He finished third in the overall standings in his debut season.

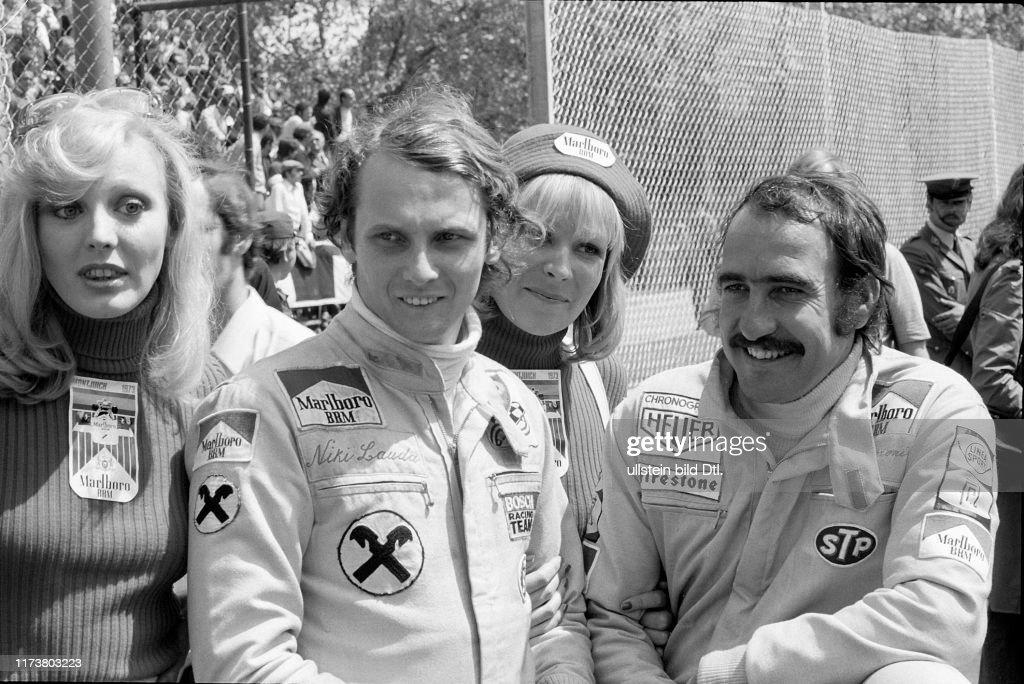

Niki Lauda and Clay Regazzoni, BRM, with ladies at the 1973 Spanish Grand Prix. Photo by Getty Images.

In 1973, he opted to leave Scuderia and moved to BRM where he joined the youngster Niki Lauda. Miraculously, he survived a huge crash once again, this time in South Africa, where he was pulled out of the blazing wreckage by Mike Hailwood.

After a disappointing season with BRM, Regazzoni returned to Ferrari in 1974 playing the role of number two to Niki Lauda. At the start of that year, Ferrari had a big personnel shake-up, after Luca Cordero di Montezemolo was hired to run the Italian team. Entering the last race of the season, in the USA Regazzoni was well in contention for the title, and only needed to finish ahead of rival, Emerson Fittipaldi, to take the crown. He suffered handling problems during the race due to a defective shock absorber and could finish only 11th after two pit stops. He finished second in the Drivers' Championship, his career best, just three points behind Fittipaldi, making seven podium appearances.

Clay Regazzoni in his Ferrari 312 T2 at the Spanish Grand Prix in Jarama on May 02, 1976.

The next two seasons were not too good for the Swiss racer who, in the meantime, became very popular, and surprised the F1 world when he decided to join the small Ensign team for the 1977 season. He opted for the small outfit in preference to an offer from Bernie Ecclestone to drive for Brabham, as he preferred "to race with nice people." 1978 proved to be another poor season, this time with the Shadow team, but his performance improved over the next season.

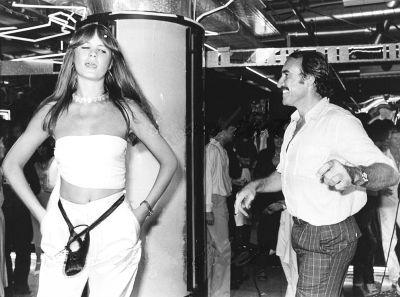

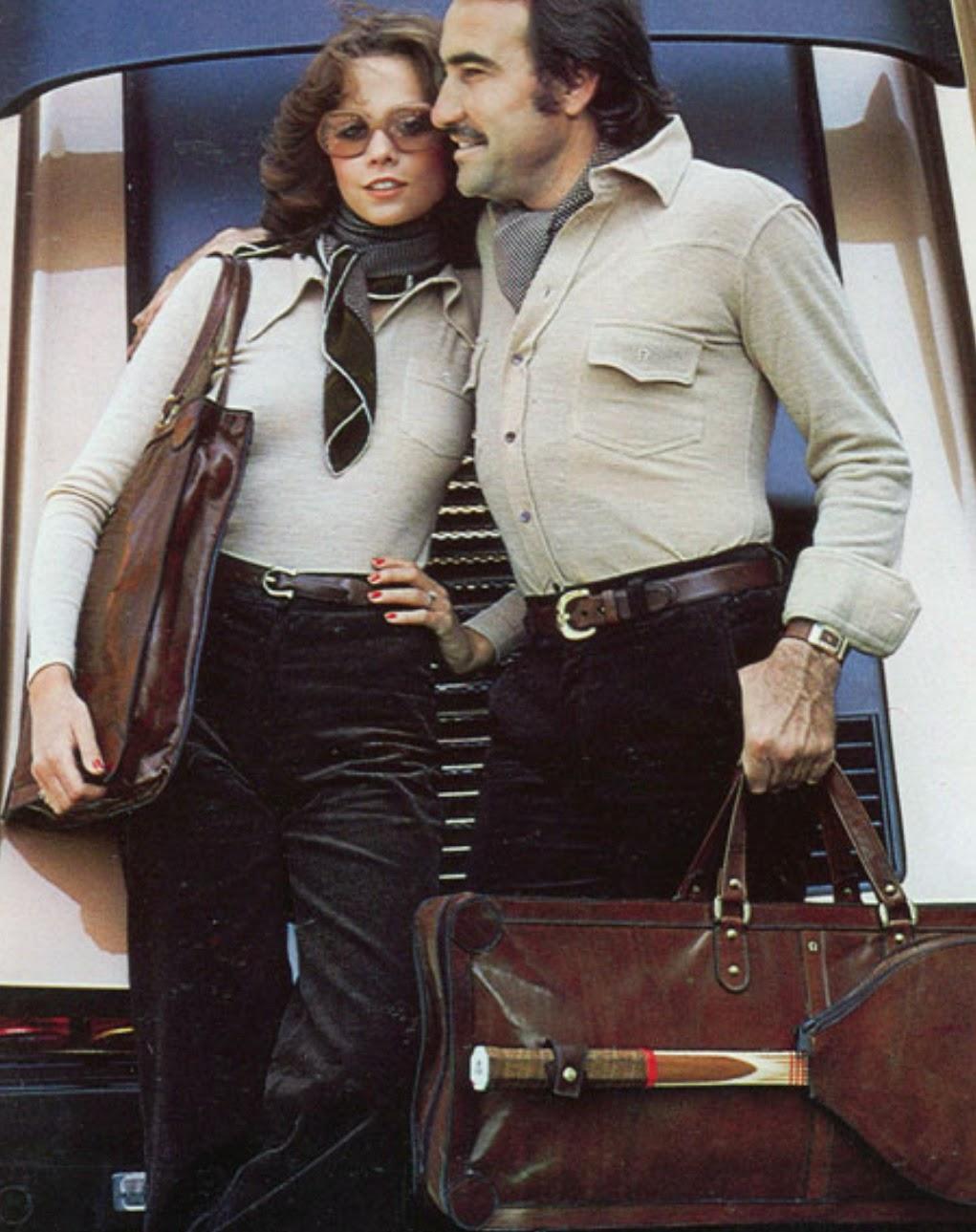

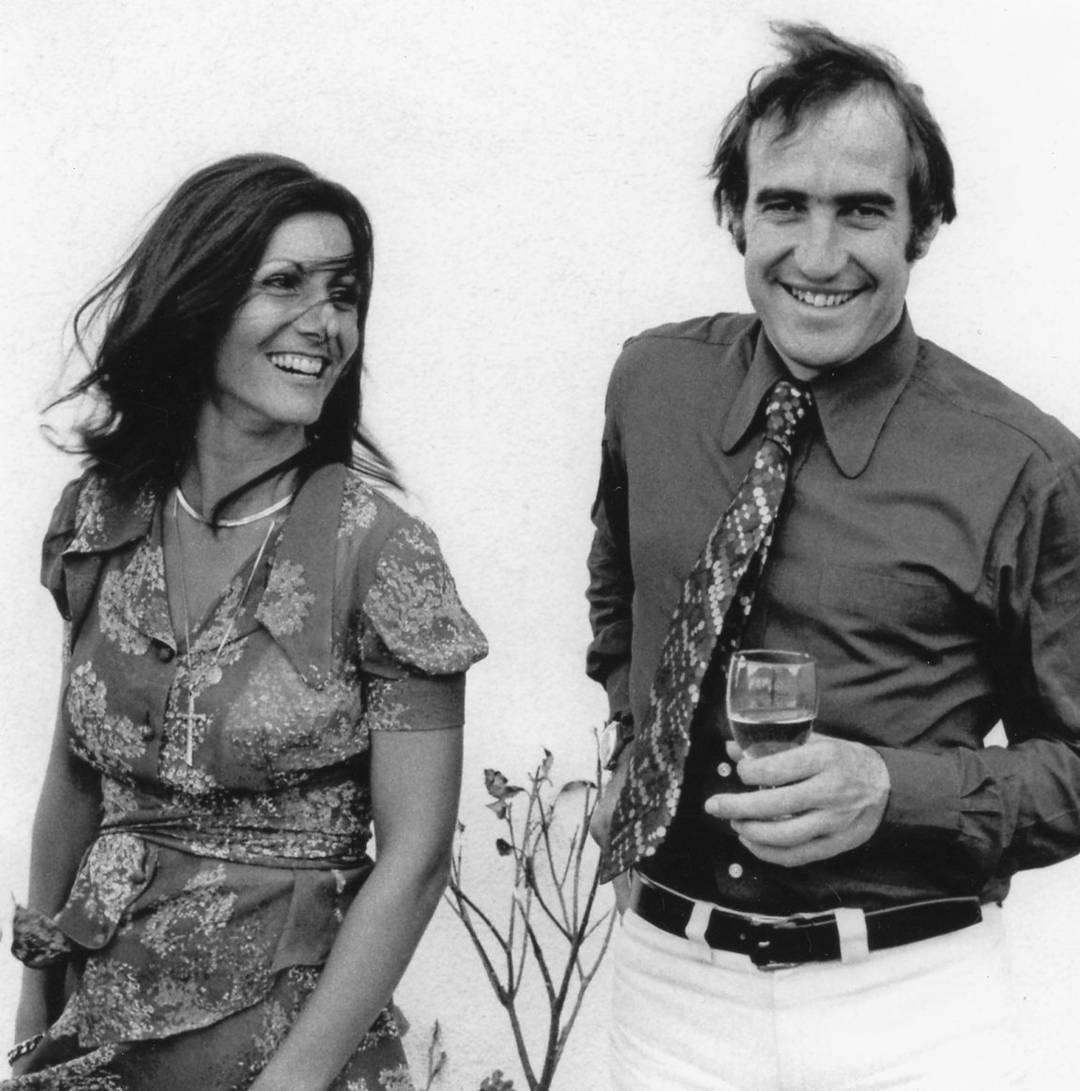

Clay Regazzoni, Doria Grey, in 1979.

Regazzoni was offered a seat in Williams in 1979, playing the number two role again, this time to Alan Jones, and he proved worthy of the faith of the team’s boss Frank Williams by winning the race at Silverstone, inheriting the lead when Jones retired.

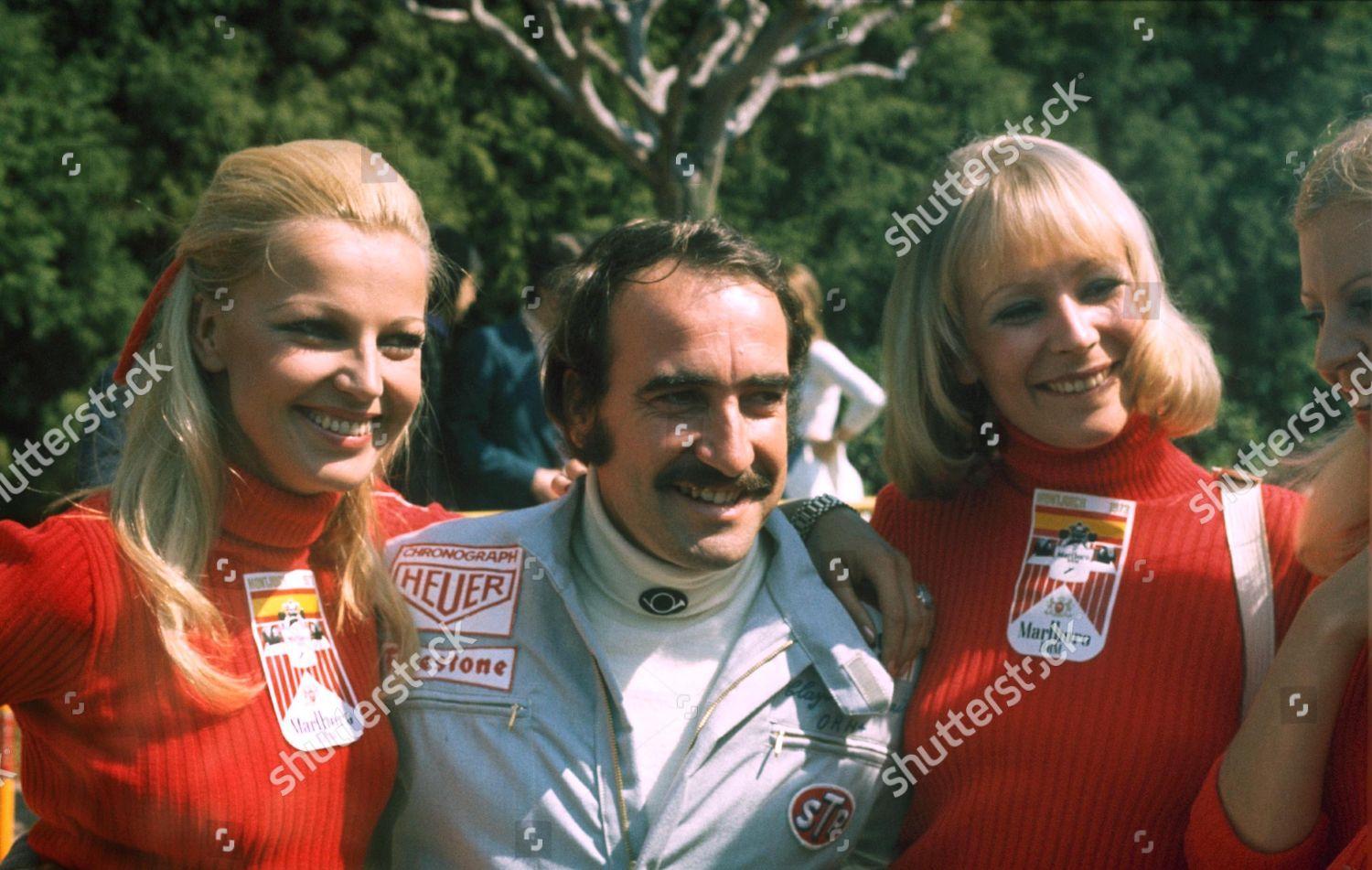

Clay Regazzoni and girls.

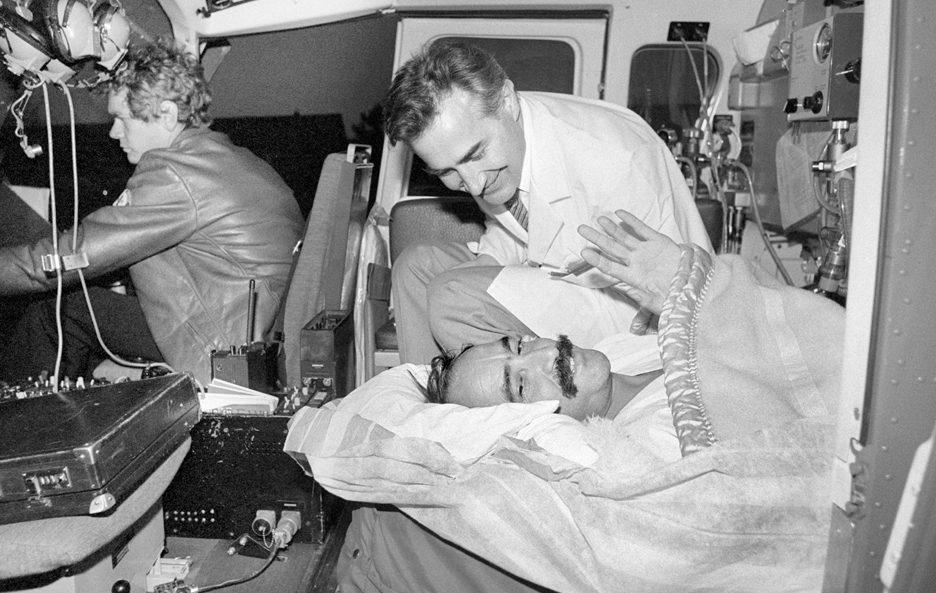

It was the British team's first ever GP victory and the start of a successful era for Williams. The 1980 season was the last Regazzoni's year in Formula 1. Already a veteran, he re-joined outsiders Ensign and had another crash, this time at Long Beach. The brake pedal of his Ensign failed at the end of a high-speed straight travelling at approximately 280 km/h. Ricardo Zunino's retired Brabham was parked in the escape road. Clay later recalled, "I hit Zunino's car, then bounced into the barrier. For about 10 minutes I lost consciousness. Then I remember terrible pain in my hips...".

After the crash, the Swiss was paralyzed from the waist down and that was the end of his career in F1.

He did not stop racing, however; he competed in the Paris-Dakar rally and Sebring 12 hours using a hand controlled car during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1996, he became a commentator for Italian TV. He once commented to Niki Lauda, his ten years younger teammate: "if you block cars and drive like a woman, you will never become great." He was known as an hard charging racer; Jody Scheckter stated that if "he'd been a cowboy he'd have been the one in the black hat."

On 15 December 2006, Regazzoni was killed when the Chrysler Voyager he was driving hit the rear of a lorry on the Italian A1 motorway, near Parma. Crash investigators estimate that he was travelling at approximately 100 km/h at the time and, despite early speculation, an autopsy specifically excluded a heart attack from being responsible for his loss of control. It seemed that third parts responsibility in the accident was to be excluded. The speed of the truck hit in the back by Regazzoni’s car would have been regular and the vehicle wouldn’t have done any sudden manoeuvre. Clay's funeral was held on 23rd of December, in Lugano, and was attended by Jackie Stewart, Emerson Fittipaldi, his close friend Niki and many other legends from the F1 world.

Clay Regazzoni.

Drunk of life, stronger than the pain. Popular and well-loved by anyone. A mastiff who understood cars. Agonistic longevity of Clay Regazzoni showed that he knew not only how to drive a car but also how to develop it. He understood mechanics as his father owned an auto body shop in Mendrisio. Clay had an instinctive and aggressive but not unfair driving style. He didn’t mistreat cars. In the early years he was known to be particularly tough in hand-to-hand combat. Before racing in F1 he has been a protagonist of spectacular accidents. Symbol of Ferrari in the ‘70s, he was engaged until the end in defending his values and his concept of life. Free from awe and stereotypes, inimitable and indescribable in honesty and genuineness. Fearless man, huge enthusiast, often mistreated and not highly thought by Ferrari, team notoriously full of politics (“ambiguity belongs to Ferrari like the twelve-cylinder engine, Lauda said in this regard), in favor of the younger Austrian. This last not disloyal but much smarter (“a corner belongs to whoever accesses it first”, Niki said. And again Lauda: “when you make it they are all with you, when you lose you’ve all against you. In between there’s nothing”) of pure Clay who, other than occasional rants, always reacted lordly. In his way of expressing himself there was great honesty, total absence of politics. It might be possible to disagree with him but the whole thing was resolved bluntly and with no reciprocal grudges. Regazzoni was a what you see is what you get man, a very rare gift. He was always very good for a laugh, for being ironic, for coming running to his friends. Cordial, nice, funny, coming to the crux of the matter not getting around it.

Clay Regazzoni. Photo by Shutterstock.

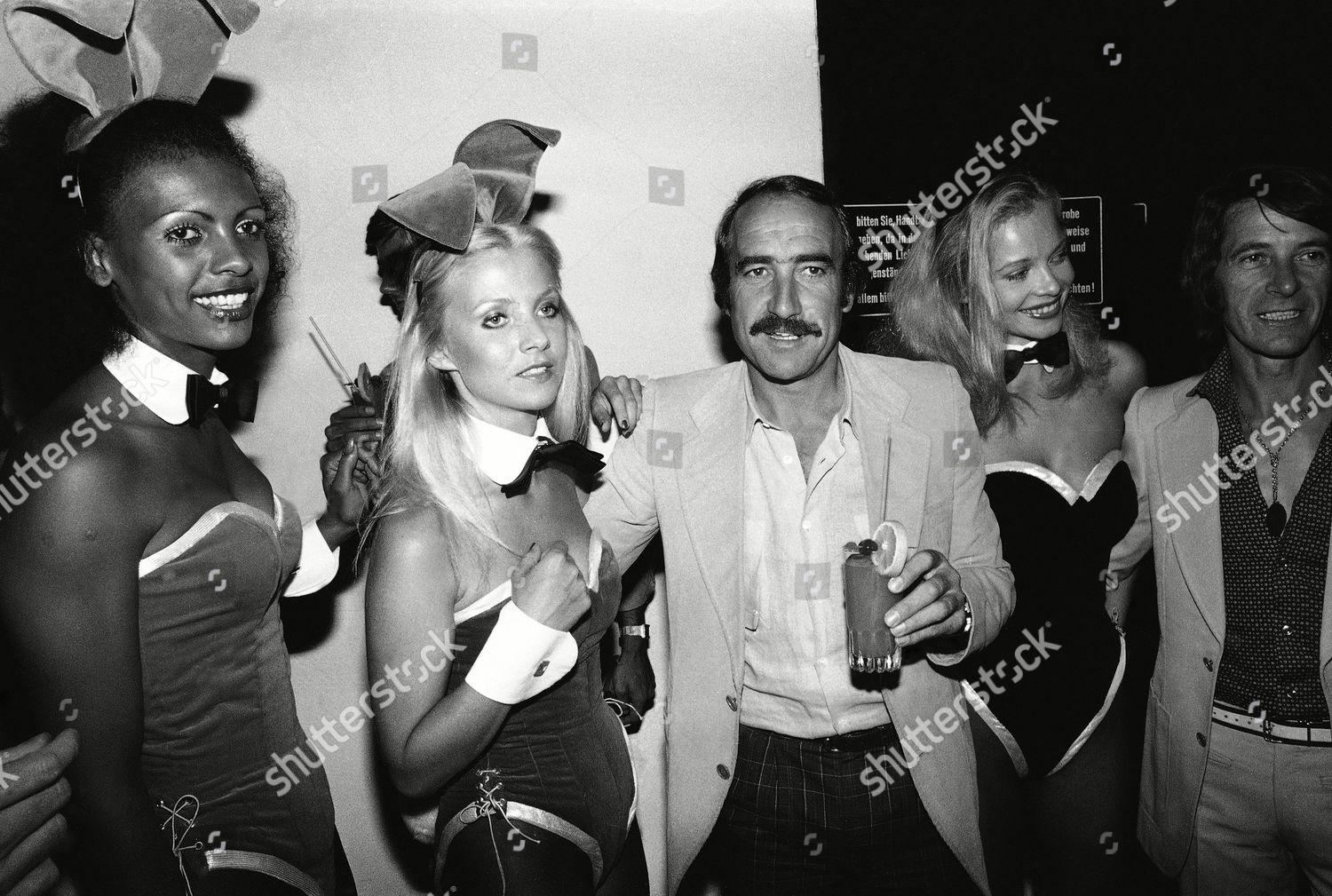

The “Commendatore” used to love him but he was able to promptly drive him out of his mind due to his social lifestyle: he was constantly surrounded by beautiful women and dedicated to nightlife.

“Viveur, danseur, football and tennis player and, in his spare time, pilot: that’s what I called Clay Regazzoni, the brilliant, timeless Clay, ideal guest of honour for widely differing kinds of fashion events, great resource of the female tabloids. I have contacted him since 1969 [...]. The year after he won a memorable Italian Gran Prix at Monza. Then he refined himself as for style and temper, which was among the bravest, until he became an excellent professional. Adversaries have always respected him.” Enzo Ferrari

Clay Regazzoni, Niki Lauda and Enzo Ferrari.

In the scrapbook of 1970 Italian GP there’s also the photo of Regazzoni’s Ferrari 312 B n°4 which goes round the parabolic curve of Monza. He was wearing a Jet helmet and moto goggles. The Swiss, at thirty-one, was racing in his fifth Grand Prix … There were 150.000 fans that day at the circuit, many of them perched on the billboards, a lot of Swiss cheering on their favorites (Regazzoni and Siffert), plenty of crashers. Lotus team had left as the day before, on that asphalt, it had lost for good Jochen Rind, its great driver. Regazzoni was third in qualifying, behind Pedro Rodriguez (BRM) and Jacky Ickx (Ferrari) and in front of Jackie Stewart (reigning world champion, in a March). On lap thirty-two, about the middle of the race, Regazzoni in his Ferrari streaked into the lead. Stewart was following him like a shadow. A duel started between them full of brave brakings, amazing trajectories, controlled accelerations, gears shifted by ear, the whole thing included in a game of trails and paths which only Monza, the speed temple, could offer. Regazzoni impressed, he didn’t let the Scottish champion go. After a series of laps with shortness of breath, on lap fifty five there was the twist: the French Beltoise, with a braking on the limit in the banking, helped by trails of cars ahead of him, was able to put the front of his Matra in front of everyone: the crowd was suddenly quiet but on the next lap waved with a great shout at Regazzoni’s red Ferrari which was passing in front of the pit lane in the head again. This time, for not being catched, Clay was driving down the straight only inches away from the pit wall. Thus, with the accidental contribution of the “intruder” Beltoise, he could stop Stewart’s game of trajectories and got away from the two. Wafted by an unbelievable cheering, Clay kept the lead till the end of the race, without ever making the slightest mistake and outdistanced his pursuers of about six seconds. When the checkered flag dropped, the public invaded the track and, spelling his name out, carried him in triumph until the podium. With that victory, the Swiss driver definitively went into the hearts of all the fans because he was a special guy, affable. He was loved because he enjoyed direct contact with people, without ever disappointing their expectations. “Other times” Clay would comment with his typically-Swiss Italian. Yes, other times. The racing world of the 1970s was very different than contemporary one: there were champions but above all men. His name will always remain linked to Monza circuit, his favorite track, where he will win one more Grand Prix in 1975, again in a Ferrari.

Defined the most representative jock from Canton Ticino of all time, Regazzoni showed right away a strong affection for his homeland, Switzerland, with a Swiss cross drawn in the central part of his helmet and colors white and red. But at home he was less loved than in Italy, at some point in his career he was even forced to expatriate being hunted by the IRS, which demanded a triple payment compared to what was the regular one, and by the police that was tired of all his raids through the streets of the city and was bombarding him with fines. This was because Clay was an Italian in attitudes, language and origin. He didn’t embody the stereotype of perfect and formal Swiss, the opposite. He was really reckless, not much a by-the-book kind of person, a whoop-de-doo making guy always the last to get his foot off the throttle pedal and always the first to let off steam. A practical joker who had fun all the time, but innocently. He changed numbers on the doors of hotels to throw off his colleagues who were staying there on race weekends, roamed around the bad neighborhoods (like late-‘70s Harlem) at night to see the face of the “wild beasts”, signed on invoices counterfeiting Lauda’s signature, took in the car technicians (e.g. Antonio Tomaini) and journalists (Pino Allievi et al.) who screamed dumbfounded invoking him to get them out of the car or drove cars made in England in the continent to overtake on the left at the invitation of the passenger whithout seeing if the road was clear, simply on trust. “Dad, what does that sign mean?” Obvious question typical of children who were carried around on your own time, unexpected was the reply of Clay who looked up and saw a 60 kph speed limit and said: “it indicates the speed limit to be respected by each occupant of the car, if we are four and you see written there 60 it means that we can go 240 kilometers an hour.” A man of many passions, especially tennis but also golf, football, fashion and then women, inevitable, always running after him. Was a show man Regazzoni, Gascon but never arrogant, always grounded, idolized by the public with whom he was always available and smiling. He was not really a genius and dissipation Hunt type, but he got close to it. Clay’s sports characteristic was generosity. A fighter who never gave up not even when he was phisically maimed. He proved it in the 1971 1.000 kilometers race at Brands Hatch, which he finished Rocky Balboa style. Forced to raise his visor that was fogged up due to the pouring rain, he drove with air and rain in his face without caring much of gravel which went in his eye. At the end of the race he showed up in boxer conditions, having a swollen eye. However he finished second despite a 10 laps initial handicap suffered because of Ickx driving off the road. Another quality was the lead foot. Great race starter, famous his flying starts off the starting grid, but even more so very good braker, one of the best in breaking a few metres after adversaries. His approach to the race could only be aggressive, for the happiness of fans and the wrath of the team. A concept of driving which meant plenty of accidents, even fatal, which caused him a number of charges. A limit this, the unreliability, which costed him the role of first guide in major teams with its related consequences in terms of treatment. A lover of the good life, for preliminary questions, he didn’t have a particularly empathic exchange with team principals who couldn’t forgive him for tennis and football injuries or for some of his extroverts vip attitudes. He was invited to all the major society parties and never lost an opportunity to go, with an exception: when he won his first Formula 1 Grand Prix, he refused the invitation of “Domenica sportiva” to celebrate in private with his mechanics. Cheerful and friendly, he was however hot in the short term even though he was respecting team orders not having anger or revenge feelings. In 1966, at Monza, Regazzoni had an accident in which he injured his tongue and needed five stitches. Back to the pits he started talking about what happened until he busted his stitches and had to come back to the hospital. In his first year in F2 at Zandvoort he tried to overtake Chris Lambert’s Brabham causing a collision which would have been fatal for the Englishman. Lambert’s father will be sueing Clay who will be acquitted. However the event worsened prejudices about the Swiss driving. At Reims, Regazzoni braked so late to be able to overtake in one shot Jochen Rindt and Jackie Stewart. The overtaking was so clear that one had almost the feeling that Regazzoni might have broken his brakes and was about to go straight. He, instead, managed to turn and made the curve. Stewart accused him of dangerous manoeuvring. Among the many critics there was however one who fell in love with this driver, who didn’t win much but was a matter of public debate, none other than Enzo Ferrari, who hired him. At Ferrari Regazzoni impressed everyone, won confrontation with Giunti and was even almost as fast as his squad leader Ickx. In Austria he finished second, very close to the Belgian: “I could have attacked him and maybe overtake him as somewhere I was quicker, but I didn’t feel right about it.” This greatest-respect attitude to team leaders will be a limit of the Swiss who already showed himself to be a top driver but didn’t have that irreverence which should characterise a challenger for the title, something that instead Niki Lauda had towards him. Enzo Ferrari was happy, he had discovered a potential champion from nothing and was very satisfied, especially in the newspaper business: “so, what did I tell you?” And everyone quiet, not much to tell having regard to the track results. In 1971 Monza GP Regazzoni started in eighth position but made a bet with a friend sitting in front of the Lesmo corner: “do you want to bet that I’ll be the first into Lesmo turn?” Cars lined up at the start, but didn’t wait for the traffic light as at Monza you started with the starter. That time the starter was someone called Restelli who, maybe scared by some problems he had had two GP ago at Silverstone where he had been fined for some uncertainties costed a few pileups at the start, didn’t wait for the last two cars to stop in their own places of the starting grid and lowered the flag too early. Regazzoni, who was really hoping in that event, was therefore able to have a launched start. He quickly overtook Ronnie Peterson, François Cevert, Howden Ganley, Jacky Ickx, Chris Amon and, braking just before Lesmo turn, Jo Siffert’s Brm. First as promised, good bet. He held the lead for three laps, then was overtaken by Peterson and Stewart. He followed them for thirteen laps, until he had a mechanical failure. If it’s meant to be it’ll keep, Enzo Ferrari thought in Fiorano when he let his pupil back on the team in public skepticism and after a year of purgatory. There was only the second driver to choose… ”Regazzoni, who would you see best?” Clay remembered his young team mate at Brm and suggested the Scuderia to pick him up. This driver was the one who will let him lose the world title and, unintentionally, his job at Ferrari: Niki Lauda. Regazzoni immediately understood that the Austrian was anything but a second driver.

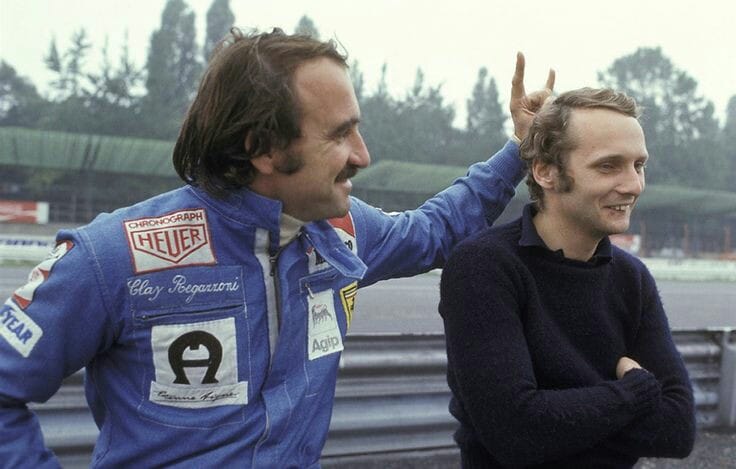

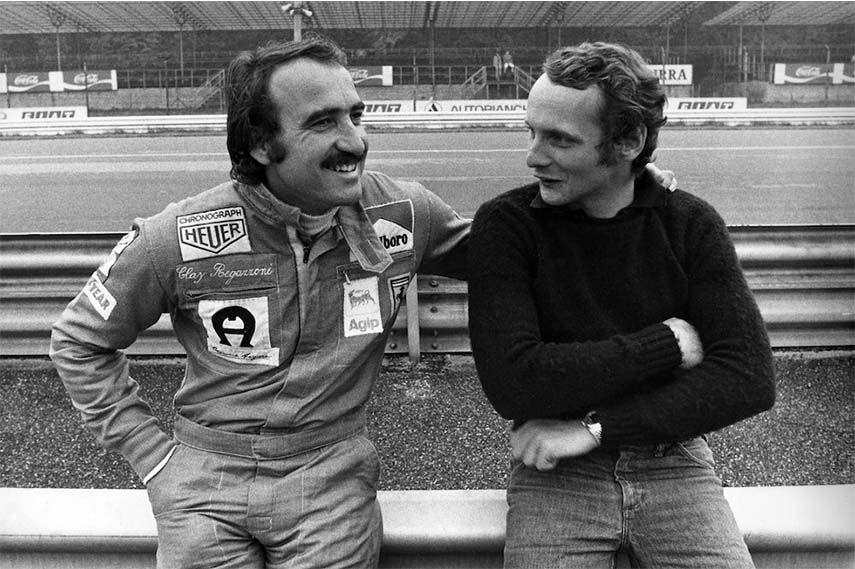

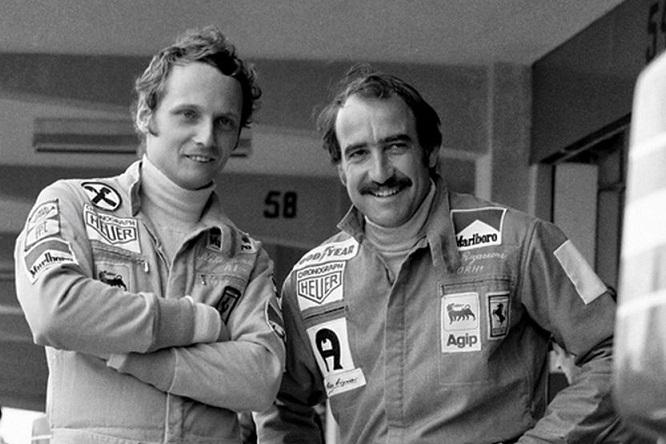

Clay Regazzoni and Niki Lauda.

Niki hammered him with a peremptory 13 – 2 in the qualifiers. The Swiss however was quicker in the race. The speed of the young second driver impressed Montezemolo who tried to convince Regazzoni to be his hen and not to fight for the championship. But Clay wanted the world title which seemed to wait for him, almost slipping throught other suitors fingers, even though, from the beginning, he and his entourage did all kinds of things to let it go. In effect the title will be lost due to a long series of circumstances such as the scant team support, bad luck and the presence of a team mate who never helped him. In Austria, despite Ferrari, even without saying this openly, put all its eggs in Lauda’s basket, Clay had had a chance to make the squad rethink about him. After thirty seven laps the three challengers for the title were out and Regazzoni could make up points. He had an issue with tires and passed in front of the finish line indicating them with a finger, keeping the fist closed. Forghieri saw him but misread his gesture: “Clay has engine trouble.” As soon as the Swiss got back to the pits, mechanics raised the carina and went to check engine. Regazzoni got upset, was screaming but his voice was covered by the roar of his Ferrari. Only after a few seconds they realized his rear tire was flat. So they started to change it but they didn’t make it on time as Regazzoni had already left. He had misread the signal of the mechanic who had to let him restart, so he had to get back to the pits again, losing two minutes. At the end he was fifth. On his autobiography he will write about the squad: “I would have killed all of them!” At Watkins Glen, without the help of Lauda, now cut off from the championship fight, Clay lost the title by three points. Seven years, six of which in Formula 1, this was the time when Clay Regazzoni stayed in Maranello. He was the longest serving Ferrari driver, before Michael Schumacher came to stay for eleven seasons. And he would have stayed even longer whitout the accident of Nurburgring which devastated Lauda’s face. The recovery of the Austrian, initially presumed to be about to die then no longer in a position to race, pushed Ferrari to sacrifice Regazzoni for Carlos Reutemann, originally hired in view of the replacement of Niki Lauda. Clay was fired on wrongful charges of having raced for himself.

Seven years to be translated in 74 world races starts, 4 wins, 11 seconds, 8 thirds for a total of 23 podiums, 15 fast laps and 4 pole positions. Out of the Ferrari he will collect few other satisfactions, a pole at Brm, a win and 4 more podiums at Williams. The last two years in Maranello saw him shadowy. Montezemolo reduced him to a second driver. In qualifiers Lauda embarrassingly won: 14 to 0 in 1975, 13 to 1 in 1976, even though, unlike Niki, the Swiss was given less performing tires and with a bit longer periods of time into the pits than his team mate. The world championship became frustrating for him, who was suffering the Austrian, always having to make up ground from the back, sometimes with testing engines unable to resist on a long run. The 1976 was along the same lines. A win at Long Beach, for the amusement of some journalists who wrote “Regazzoni, by accident, must have raced in Lauda’s car”, and a final ranking which emulated the one of 1975: fifth, with episodes like that of Brands Hatch, where he tried to overtake Lauda at the start passing him at the internal side of turn 1 being then cut off by the Austrian, that made the team very angry. People started talking about a change, but Lauda was involved in Nurburgring burning. At Zandvoort Regazzoni contended the win with James Hunt but was hindered at the hottest moment by lapped Alan Jones in a Williams. He will be second. In the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, historically in the Swiss favour, Lauda returned. In qualifiers Regazzoni was given used tires as Carlos Reutemann was also in the team and so materials were in short supply. “I have been provided with scandalous assistance”, his comprehensible outburst, “from second I became third driver.” Ninth at the start, but with a cool race, Clay finished second beating his two team mates. Bernie Ecclestone, Brabham team principal, became aware of his problems and offered Regazzoni to replace the same Reutemann in 1977. The Swiss, instead of figuring out the way the wind was blowing, was persuaded by assurances from Montezemolo who promised to keep him the job in store for the next season. It will be a crucial error. In the Japanese Grand Prix at Fuji, the last race of the year, Lauda made a lap and pulled out of the race. Regazzoni criticized him: “if you’re scared you go slow, you don’t pull out of the race!” For Clay it was time to say goodbye on suspicion of, mockery of mockeries, not having been a good wingman. But he was the one robbed in 1974 by who should have helped him. At the age of 40 he was offered a last chance by Frank Williams. At Silverstone he came back to win by twenty eight seconds on Arnoux and a lap on Jarier’s Tyrrel and Scheckter’s Ferrari. All happy, including Ferrari fans… No, not at all. Frank Williams couldn't be found. He was not in the front line to enjoy his first win, on top of that in his home GP, and was late in showing himself. Alan Jones as well didn’t show up, it was almost as if a driver of a different team had won. When Regazzoni finally saw Frank Williams he walked toward him and, instead of shaking his hand, made fun of him with a “sorry”. In his career the Swiss had plenty of crashes, sometimes horrible, without feeling them too much emotionally speaking. Described by some doctors as “the man with no nerves”, it was difficult to see him shocked or scared and not because he was a good actor. Pulsations of his heart were always regular. Among his most significant accidents, in addition to those mentioned above, you could mention four of them. Early in his career, during an “Hill Climb Meeting”, he went over a cliff, the car passing from tree to tree to stop at the end with its driver unhurt.

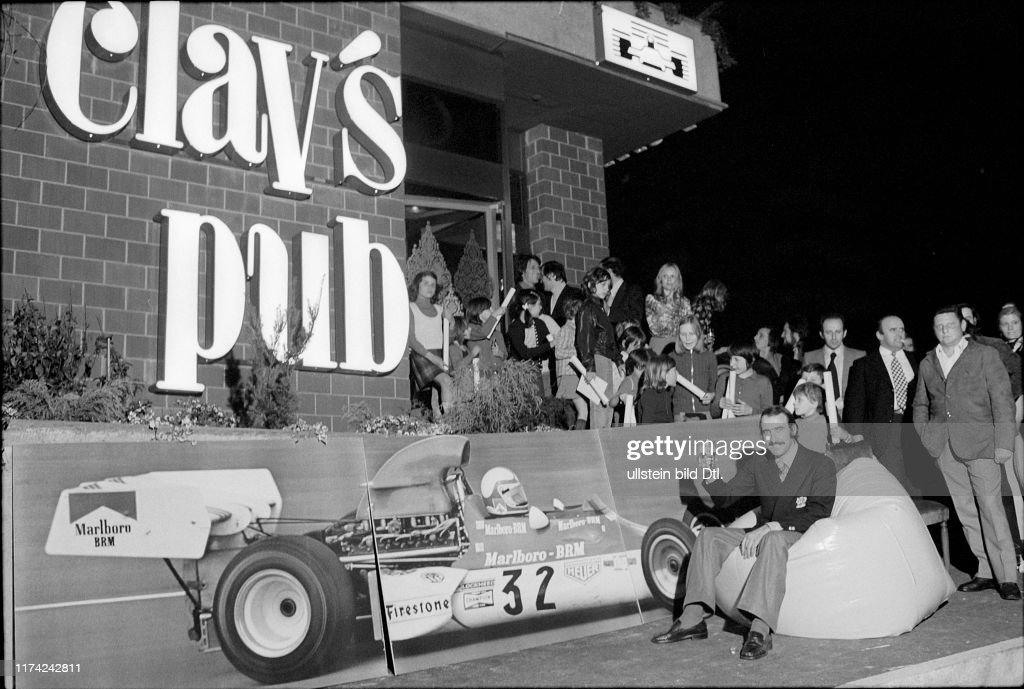

Opening of Clay’s pub in Lugano in 1973. Photo by Getty Images.

In 1973, in an Alfa 33 during “Targa Florio” practices, he drove off the road and took off over a flock of sheep, landing upside down but unharmed. In 1977, during “Indianapolis 500” practices, his McLaren at 300 km/h did three loop the loops before stopping. Unscathed again and blocked by doctors for a preliminary check, his pulse was lower than the one of the follow-up to authorize him to compete. “Excuse me, didn’t you just have an accident?” Clay nodded and explained them that he still had time to qualify, got in his spare car and qualified, finishing the race 30th. In 1978 at Long Beach he saw Gilles Villeneuve’Ferrari flying only centimeters from his helmet. He didn’t see the coming of the Canadian, who was about to lap him, and closed the trajectory. Like nothing happened he continued and finished tenth. If there was a way to make Enzo Ferrari mad, that was to invade his privacy. The Commendatore was austere and brilliant, but also very closed and private. In him everything pointed to this conclusion. An almost monastic temper, the strong defense of his brand, of his cars (more important than drivers health) and even of his private Fiorano circuit, that no one could access without his consent. Privacy, order and discipline his three principal commands. Now imagine an outgoing, not too rules-based person and put him in Maranello courtyard. What could happen then if the mythical prancing horse, a gift from Francesco Baracca’s mother, ended up stenciled on the back jeans pockets or if, entering the Fiorano Circuit, the great Enzo saw damsels in skimpy outfits and with uncovered breasts posing in a Ferrari 312 B3 with all the mechanics looking at them with their tongues hanging out? The whole thing in addition to have lost the F1 world drivers and constructors championships in 1974. Legend had it that the screams were heard until Milan, what the hell we’re not at Hesketh here!

Clay Regazzoni at the 1976 Dutch Grand Prix.

“The last 40 years of life out of 60, more or less, I spent in all kind of cars, on circuits and roads from all over the world. People recall above all Formula 1, particularly the years at Ferrari, but those years, perhaps the most fascinating, are only part of my long career.” Clay Regazzoni

“Nel dubbio io tengo giù (when in doubt I keep my foot down).” Clay Regazzoni

Clay Regazzoni with Niki Lauda.

“I was just racing day by day. With Niki [Lauda], every race was to be on the top. He programmed his life to be champion. I enjoyed life. That was the maximum for me.” Clay Regazzoni

“Today everyone can brake at 100 metres, what do you need the courage for, what do you steal to the other? Eighty centimeters!” Clay Regazzoni

“Now they only talk about technology even thought drivers won’t have anecdotes to tell in 50 years when they retire or they will find each other in clubs. What stories they tell?” Clay Regazzoni

“With him disappeared a driver and a brave and generous man who has always interpreted life like this,” Luca Cordero di Montezemolo said after his death; “I remember him not only as my driver in unforgettable years, but also as a keen fan of Ferrari. For him races were bravery and challenge to address on the edge, from first to last lap. With him and Niki Lauda I celebrated my first world championship at Ferrari, in 1975, and I can’t forget about his great successes in our F1 and Sport cars. It’s a time for me of great sadness also because his “Swiss-Neapolitan” character made him unique even outside the races and there are lots of memories which come to my mind.”

Clay Regazzoni and Niki Lauda.

Niki Lauda said to journalists about his friend’s accident: “it was you, practically, to inform me. It was shocking for me, I never expected that. Even more being killed in a road accident. For someone like Clay it seems like a joke of destiny. The taste of life I have really learned by Clay, and after my accident his teaching was even more valuable. Because if there was a skill of Clay above everyone else this was his think positive. At Ferrari we have also had some issues, as Montezemolo called me and said clearly I was number one. Clay didn’t like it but he told me directly, he always talked to me right in the face. He was very straight, we even had quarrels, but I’ve always lived it like an act of great loyalty. Even today he was full of life. The last time we met was last year in Montecarlo, at the Grand Prix. Once again I was struck by his positive thinking, his incredible will to live. He loved smiling, and on that day we spent a few hours together having fun like old times.” From Regazzoni Lauda added to have learned the taste of the joke, but also the one of the risk at the gaming tables, or the one of beautiful women. “We used to hang out often when we were racing at Ferrari, but I was shy. He was the one who taught me what is it. He never missed a party, this was out of the question. At that time many women were interested in drivers and fascinated by racing circles. In drivers area the mood was always funny, diversions were a lot and I’m not going to specify what they were. Clay of course was a man of the world for all intents and purposes and knew very well the risks he took. Not to mention that at the time you were living differently than at present, the ‘70s were different to be fair. Obvious that for pilots the perspective was even different as they were risking their lives. Clay was a playboy driver of the old guard and I had a feeling that to beat him I had to go to bed before him.”

Frank Williams: “Clay won the first Grand Prix for Williams in 1979 at Silverstone. That event was probably the most important for our team in Formula 1. He was always a gentleman and it always gave me great pleasure to have him on our team. Me, Patrick Head and every member of the squad will always remember him.”

Michele Castelletti thought to ask Gianfranco Palazzoli, a friend of Clay Regazzoni, some questions about the champion. How did you meet Clay Regazzoni? “Until the 1980s motor racing was very different from today: I like to call it a group of friends travelling Europe (and the world) to race cars, our great shared passion. But rivalries were only on the track: as soon as we got out of the car we were all friends. I have thus got to know Clay. Due to the fact I lived in Varese and Clay in Lugano we became friends: then, thanks to the similarity of our dialects – of Varese and of Ticino, – we had a chance to often send us our opinions and impressions precisely in dialect.”What kind of person was Clay Regazzoni? “Clay was capable of dragging public and enthusiasts as he was the typical driver “from that era”. A driver, therefore, who transmitted exactly his passion for that sport and even “that dash of madness” that was needed to be quicker than the others. He was a colorful character. Amongst other things he played tennis very well. This, let’s call it “exuberance”, he demonstrated in a lot of situations: if you had the opportunity to speak with some people of the border patrol then they could tell you some adventures happened in customs, or even managers of municipalities in the surrounding area could remember fights with him for the speed at which he was crossing population centres in the car. In those days you raced most of the time in Europe and so you made three or four cars and travelled all together. Or, for overseas races, you travelled by plane and then rented a car out of the airport. They came up to the point that to some people hiring cars was refused: it was always a competition from the airport to the circuit. Not to mention then when you went to Germany, where there were no speed limits on the highway… Now everything has changed and even in Formula 1 environment is more “in plaster”, human relations are less important compared to those times. Clay brought enthusiasm and interest not only in Italian fans but also in Swiss ones. He, from Ticino, in fact was also well-loved by more “German” Swiss for his way of living and expressing himself, for the ability to be open and, not least, feisty on track. Unfortunately his style also led him to sad consequences. I’m referring to Long Beach Grand Prix in 1980. After the crash I went straight to the clinic where he was hospitalized: he was really in critical condition. Then, with a lot of grit, he recovered. Obviously he had to go around in a wheelchair. But, thanks to his strength, he regained independence: he drove easily and moved on his own. And then that day when he had the accident on our highway… It is still unknown what happened exactly… it was a bad thing… He had an amazing spirit and didn’t absolutely want to give up. He reacted at the difficulties beautifully.” What was his best race?“Many fans will remember his first win in a Ferrari at Monza in the 1970 Italian Grand Prix and the greatest races of his career were surely the ones at Ferrari. Now to win in Formula 1 you need a great car, the appropriate mentality and the right staff. Things were different then. Regazzoni’s driving skills were fantastic in terms of speed. But sometimes he has gone too far and has lost races that he shouldn’t have lost. He was world famous for his way of driving: he made some manoeuvres to leave you with bated breath as long as you would see him surviving unscathed, and you were very happy of this. His great qualities of ace pilot were also confirmed by the fact that he was the one who suggested Enzo Ferrari to hire Niki Lauda. Clay really helped Niki, who, thanks to his talents and the ability to use his head when he drove, took his place. This proves that he had it right.” How was his relationship with the “Grande Vecchio”? “Ferrari liked Regazzoni very much. On the other hand Enzo Ferrari also raced when he was young and was a motoring enthusiast and had transformed his passion in a job. He absolutely loved these drivers who put something of them and often went beyond the limits. Ferrari liked Clay a lot, perhaps also for their coincidence of view. You’d then have to say that the Commendatore always had a fondness for this kind of drivers: after he wanted Gilles Villeneuve, basically a complete stranger in Formula 1 back then. At Silverstone, in his rookie race, Villeneuve in a McLaren at the first corner went already straight and Ferrari liked drivers who dared. But in the end it should be recalled that he, after all, also had a business to run and if within the seasons the results didn’t come, of necessity, he was forced to change.” Have you ever raced against Regazzoni? “Not against but with Clay. If Regazzoni lived right now he would race in Formula 1 only. Whereas in those days they divided themselves between races into Formulas and prototypes. There was also Formula 2 in which all the greats have raced and some of them, such as Jim Clark, have lost their lives. Therefore these competitions had much more appeal for spectators and raised even more their enthusiasm because you could appreciate driver’s abilities while he was racing in Formula 1, Formula 2 or Prototypes. In addition they saw also the driver devoting personal attention to his car, along with the three or four mechanics who were following him, and in some cases even working on it. It was completely different from today, when the pilot gets out of the cockpit of the car and looks at the monitor, engineers are not asking him anything and the driver himself doesn’t talk much for fear of looking bad finding that not good performances might be caused by his fault, revealed by the telemetry and images.” What’s your fondest memory of Clay? “In the back of my mind I wouldn’t know how to define a specific moment. To be out with “il Clay” was always something special. So they were all good moments. I recall that there was a time when he owned a right-hand-drive Lancia Aurelia Coupé and it was fun to go running around with him, as he was wondering if he could overtake or not, due to the fact you can’t see when to pass in a right-hand-drive car if you’re behind another vehicle. When I was sitting next to him, and so being on the left I could see, he trusted me asking in perfect dialect from Ticino: «Pala, l’è bona? (Palazzoli, can I go?)» And, as soon as the road was clear, I would tell him «fora! (out!)» And he went out cheerfully passing other vehicles. There were a lot of ups and a lot of downs. He was a great person. You could always count on him.”

To the journalist Pino Allievi who, in a car with Clay driving in the fog desperately asked him to slow down, Regazzoni replied: “in the fog, the less you’re in the better…” And Pino Allievi said about Regazzoni’s time: “it was a funnest Formula 1, in which there were so many girls hanging around, plenty of models and drivers were the players. Simplifying, the modern-day drivers are extras. Drivers from back then were handsome men, fascinating, who were using their brain, had a culture, had a savoir-faire and clearly, clearly fished very much from women environment.

Clay Regazzoni and Maria Pia.

And about Clay’s wife Maria Pia: “he lived quite heavily the removal from his wife. I think he always loved her, in a different way, then life kept them apart.”

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment