I spent Sunday afternoon watching the farce that was the Belgian “Grand Prix” unfold; this article isn’t about that.

Lando Norris at the 2021 Spa GP.

In fact, I have concluded that the less said about it, the better. The undoubted highlight of the grand prix weekend was, once again, the qualifying performance of George Russell in the Williams.

George Russell.

There is always a discussion about how much is the car and how much is the driver. George shows us week in, week out, that a brilliant driver can produce results in an under-performing car; his qualifying and race craft show up Nicholas Latifi’s shortcomings every week. Make no mistake, to be able to drive an F1 car at all and to have won the races he has in the lower formulas, Latifi has shown he is a competent, even good, racing driver. George Russell’s talent, however, has always shone through. Throughout his junior career he was always competitive and running at the front.

As the rain fell and the commentators and public alike contemplated how unfortunate it was for George that he wasn’t going to get the chance to capitalise on his wonderful qualifying and achieve a genuinely good result, the words of a former champion about another talented driver, who drove for Ferrari, but never won a World Championship Grand Prix, ran through my mind. Mario Andretti once said of Chris Amon’s famous bad luck: “if he became an undertaker, people would stop dying.”

So who was this talented, respected driver who never quite made it to the top?

Chris Amon.

A native New Zealander, Chris Amon came to the attention of the motorsport world competing in the 1962-63 Tasman series, which in those days was a sort of winter F1 series taking place across Australia and New Zealand. Reg Parnell invited him to Europe to compete in Formula One.

His first race in Europe was at Goodwood in the Glover Trophy followed by the Aintree 200. Amon was ready to make his Formula One championship debut. He did so at the 1963 Belgian Grand Prix where he retired early on with an oil fire. Mechanical failure dogged his season, however, with retirements at the Dutch, German and Mexican grands prix. Then an accident in qualifying for the Italian Grand Prix left him with broken ribs, leading him to miss both the Italian and USA rounds of the Championship. The paddock was impressed with the young Kiwi, who was still only 19 years old.

Chris Amon in the BRM powered Lotus 25 entered by Reg Parnell, Grand Prix of Germany, Nurburgring, 02 August 1964. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

He raced for the Parnell team the following season, with the team being taken over by Tim Parnell, after his father, Reg passed away from peritonitis. Despite his on-going mechanical issues, Amon achieved his first points, a 5th place at the Dutch Grand Prix.

Off the track, Amon was enjoying life, sharing a flat with fellow racers, Peter Revson, Mike Hailwood and Tony Maggs.

In 1965, Parnell reluctantly split with Amon, after BRM insisted on Richard Attwood as their regular driver in return for their engines. Fellow New Zealander and ambitious new team owner, Bruce McLaren signed Amon up for his eponymous team, but was unable to produce a second car, leaving Amon to go sports car racing. He also won the Formula 2 race in Stuttgart and stood in for the injured Ashwood at the French Grand Prix and competed as the second Parnell driver in the German Grand Prix, retiring early with mechanical failure.

Chris Amon in a McLaren.

In 1966 Amon continued to drive in Can-Am for McLaren. His forays into Formula One kept being thwarted. McLaren never managed to produce his second car.

Chris Amon, Roy Salvadori, Jochen Rindt, Cooper-Maserati T81, Grand Prix of France, Reims-Gueux, 03 July 1966. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

A chance arose to drive for Cooper F1. Amon drove in the French Grand Prix but lost out to the full time drive to the newly available John Surtees. He entered the Italian Grand Prix as Chris Amon Racing but failed to qualify his Brabham BT11.

New Zealand racing drivers Bruce McLaren (left) and Chris Amon (right) with Ford CEO Henry Ford II (centre) on the podium after winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the 34th Grand Prix of Endurance in Le Mans, France, 19th June 1966. Photo by Reg Lancaster/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

On the Sports Car scene, however, 1966 gave Amon the biggest moment of his career. If you have not seen the movie “Le Mans 66” (Ford vs Ferrari) you really should. [SPOILER ALERT] It was at that race that Ford had their famous victory, forever controversial for the team orders that made Ken Miles slow down for a staged finish across the line. The other Ford, driven by Bruce McLaren was adjudged the winner in the photo finish. McLaren’s team mate in that race was Chris Amon. (Ken Miles’ team mate was the other great New Zealand racing driver and future F1 Champion, Denny Hulme).

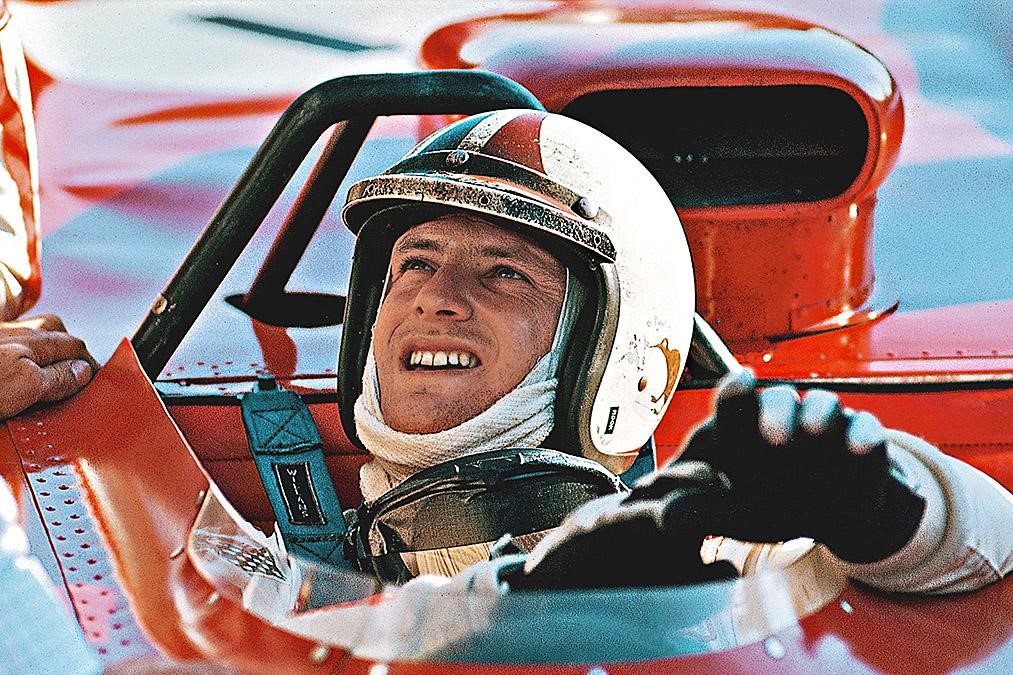

Chris Amon in a Ferrari.

As a result of his drive at Le Mans, Amon was summoned to Maranello to meet with Enzo Ferrari. This resulted in a contract to drive for Ferrari in 1967. There was a difficult start to the season with Amon being injured in a road accident on the way to Brand Hatch and subsequently had to withdraw from the pre-season Race of Champions at Brands Hatch. Then things got worse for the Scuderia Ferrari team with Lorenzo Bandini losing his life after a crash at the Monaco Grand Prix. Mike Parkes broke his legs at the Belgian Grand Prix, which resulted in the fourth Ferrari driver Ludovico Scarfiotti deciding to retire. This left Amon as the sole Ferrari driver for the rest of the season (until he was joined by Jonathan Williams for the final race of the season in Mexico). Despite this, Amon had his most successful season in Formula One, with four third place finishes and fifth in the Drivers’ Championship.

Driving for Ferrari in Sports Cars, Amon won the Daytona 24 Hours and 1000KM Monza race. Partnered in the BOAC 500 with Jackie Stewart, Chris Amon took Ferrari to the Sports Car Manufacturers championship.

The 1968 Formula One season was marked by brilliant speed, with three pole positions and a thrilling duel to the line with Jo Siffert at the British Grand Prix. The results didn’t come through and, dogged by reliability issues, Amon only managed to finish 5 races, scoring a total of 10 World Championship points. The highlight was the second place in Great Britain.

Amon in a Ferrari at Monza in 1969. He did not win a grand prix in 96 attempts. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

In 1969 it wasn’t much better. Ferrari suffered from engine reliability problems all season and Amon’s best result was P3 at the Dutch Grand Prix.

Then, with the turn of events and sheer bad luck that dogged his whole career, Amon decided to leave Ferrari and their unreliable V12s for a Cosworth powered team. As it happened, with newly secured backing from Fiat, the Ferrari V12 turned out to be one of the best Formula One engines of the 1970s. Amon ended his Ferrari career finishing runner up in the 1000 KM Monza race.

Chris Amon, STP March 701, 1970 British Grand Prix, Brands Hatch.

Moving into the 1970s, Amon signed for the newly formed March team, gaining the team’s first world championship points at the Belgian Grand Prix. Despite his speed and good qualifying, he left at the end of the season with a handful of points and possible victory at Watkins Glen denied him by a puncture. Furthermore he had fallen out with Max Mosely over money. He moved onto the newly formed Matra F1 team. Despite a podium finish in Spain and a pole position at the Italian Grand Prix, his bad luck continued as he was thwarted by a detached helmet visor in Italy and a bad accident at the Nürburgring, causing him to miss the Austrian Grand Prix. In 1972 the theme continued as he scored a handful of points for Matra. The highlight of the season was the French Grand Prix where Amon achieved pole position. Of course, he got a puncture whilst leading but re-joined the race to finish third (breaking the lap record in the process).

Having ventured into supplying Formula 2 engines as Amon Racing Engines in 1972, that he eventually sold to March at a loss, he had a disappointing season with the Tecno team. In 1974, having turned down the opportunity to join the Brabham team, Amon revived Chris Amon Racing but without any success to speak of.

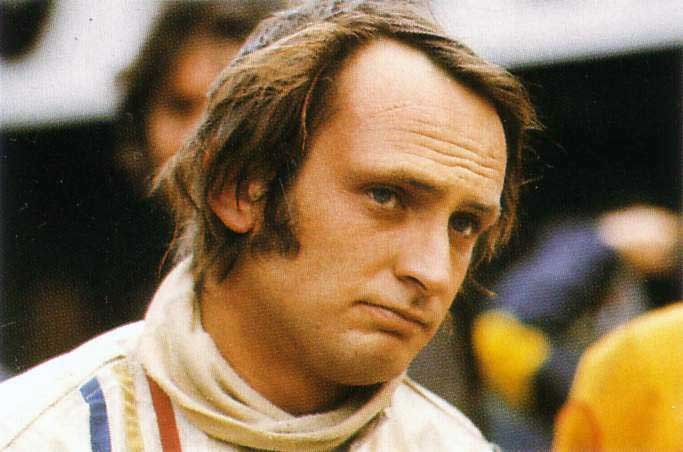

June 1976, portrait of Ensign driver Chris Amon. Credit: Tony Duffy/Allsport.

In 1976, he secured a drive with the Ensign team. Despite early promise in terms of speed, Amon only managed a handful of points, whilst being lucky to escape serious injury in the Belgium Grand Prix where he lost a wheel. His suspension failed as he closed in on a podium finish in Sweden. The end came in the infamous 1976 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring. After Lauda’s crash on lap 2, Amon refused to return to the grid for the restart and was promptly fired by the team.

Amon announced his retirement and returned to New Zealand. He was persuaded to join the Wolf-Williams team for the North American races towards the end of the season and although he did post some promising times in practice for the Canadian Grand Prix, another heavy crash caused him to walk away. He drove one race for Wolf’s Can-Am team in 1977 before walking away again. He no longer enjoyed being a racing driver. He did, however, recommend his successor in the team, the then unknown Gilles Villeneuve, to Enzo Ferrari. He then returned to New Zealand and retired for good. In his retirement he encouraged and supported the New Zealand motorsport industry. He passed away in 2016.

Chris Amon (right) with Jim Clark at Indianapolis in 1967. Photo courtesy Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

In his time, Chris Amon was known as a sublimely talented racing driver. He had the speed and talent to mix it with the all-time greats of John Surtees, Jackie Steward, Jim Clarke, Jack Brabham, Denny Hulme and Graham Hill. It’s not hard to imagine that if he had managed to find himself in a different car and a different team, his name could have been amongst those as a world champion but he never won a World Championship Formula One Grand Prix. The margins between racing success and failure are often imperceptibly thin and can turn on one bad race or one bad choice.

Chris Amon.

Is it the driver or the car that bring success? Chris Amon’s career shows you that it is a subtle combination of both. It’s about a driver being in the right car at the right time. For whatever reason, it just never worked out for Chris Amon.

By Clare Topic

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment