Also Formula 1 had its “roaring twenties”, those of 1000 horsepower. There were 1000 horsepower twice, in the late 1980s (1986, 1987) with the 1500 cubic centimeters supercharged engines, and in the early 2000s with the 3000 cubic centimeters V10 ones. Two types of very different cars, undriveable and brutal the first ones, on the tracks second ones, assisted by power delivery and aerodynamics which allowed crazy lap times. Neither easy to drive, although the most modern ones offered far more benefits. Today 1000 horsepower would not be a problem at all, given the very safe circuits with wide run-off areas and the progress in chassis, aerodynamics and passive safety. Of course the risk for drivers would increase a bit but racing has always been man stuff. 1986, unknown for most people and unpopular in the International Federation, always concentrating on security and far away from the true spirit of this discipline, was the highlight of the age of turbo, the year of monsters. It was the magic year of monstrous turbo charged engines with more than 1300 horsepower, the most powerful F1 cars of all time. Technology wasn’t today’s one but those cars were real four-wheel monsters and driving them was a powerful emotion.

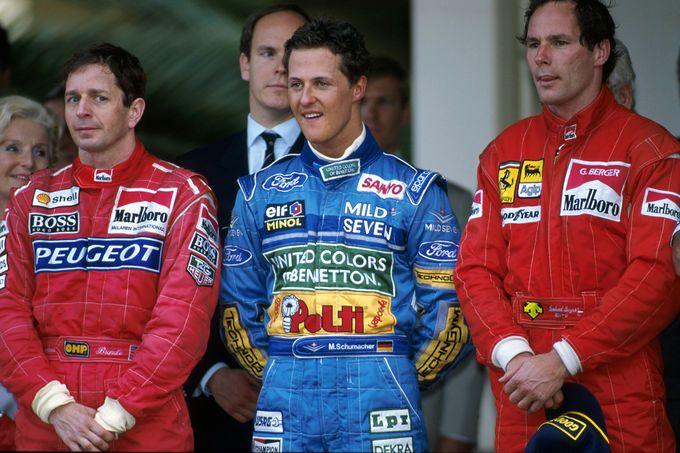

Martin Brundle, Michael Schumacher and Gerhard Berger at Monaco GP.

Martin Brundle, a driver at the time, reminds them: “as usual, when I find myself in driving a current car, I’m impressed by cornering speeds, grip and breaks, but the engine doesn’t provide you the same sensations, and the 2.4 V8 are all like that. Totally disappointing and not at level of a three-litre V10 which, of course, in turn paled in comparison to a turbo one. Sometimes you have a chance to talk about the turbo time with someone like Gerhard (Berger) or Derek (Warwick) and, honestly, it’s like talking to someone who knows something that no one in the world knows. It’s about an absolutely terrifying experience, in particular with the qualifying tyres and on circuits where barriers were very close to the track. Experiences that really open up your eyes, such as the one of Monaco GP, when, at the qualifying session, you started to make the hill with an extra power of about 400 horsepower compared to the ones that we had in previous years.” According to Alain Prost the best time in this regard was the one just following the mid-1980s: “and then they spoiled the things cutting power and the amount of fuel we were allowed to use during the race.” “Yes undoubtedly 1986 was the best year”, Berger confirmed: “when powers were still free. The cool part is that not everybody could manage so many horsepower, especially in qualifying. Top of the line were Monaco’s hill and Casinò square, where you had a lot of wheelspin even in the highest gears and in dry conditions. At that time I wasn’t in control of many things, all I kept thinking was my driving, because I used to like to have 5,5 bar of pressure which were pushing behind my back. I was really disappointed when they banned turbos as for the rest of my career I couldn’t drive them anymore. To handle one of those cars was very difficult, because you had to optimize the delay in the throttle response, keeping a good engine speed without getting the power down and of course you had to ensure that wheels weren’t spinning too much … and naturally you had this enormous forward thrust. When I came straight out of F3 to one of these things, it seemed like the world went crazy. I loved those cars. Some say that the only thing we weren’t happy about was the lack of an immediate response by the engine”, Berger continues, “but I liked this characteristic very much! I appreciated the fact that, when you approached corners and as soon as you could feel the power, you splattered quickly 50 meters forward. This was something that you know …. required you to have a certain amount of balls to be able to go always full throttle. Therefore, if the power came on too early, you were really risking to run off the track. It was fun, to calculate the right way you had to push the accelerator pedal, hoping to have done it properly. And then anything else would have proved a disappointment. Isn’t it?” In the 2000s the FIA saw that the power of the 3000 cubic centimeters V10 engines was through the roof and imposed their retirement in favour of the 2400 cubic centimeters V8 ones. One last figure which is sort of funny on the first age of turbo, comes from a comment of Patrick Head concerning the 1986 season: “in fact Honda couldn’t tell us how much power we had, because they didn’t really understand it either! The test bench could keep records up to 1000 horsepower at 9300 engine revolutions per minute, but we were at 13500 revolutions or so …” The’80s were the era of the pure pleasure for speed fans; there were no drivers in F1, but crazy people with significant propensity for suicide. Those powers were madness, that’s why you are always fascinated when reading or listening to stories of the age of turbo. Over 1000 horsepower with 5,5 bar of pressure in 1986, sixteen mythical Grands Prix; the year before they wouldn’t reach them and the year after powers would have been cut. 1988 is the last year of turbocharged engines, the pressure is limited with a pop-off valve preventing overboost, that excess of pressure which, in previous years, had allowed BMW Turbo engine of Nelson Piquet’s Brabham to reach the unbelievable limit of 1430 horsepower. Turbo engines in the mid’80s had amazing powers in qualifying, thing that you can surely get today thanks to the electronics and evolved material, but that many years ago represented a true challenge, both in research and application. Drivers who drove those monsters remember unreal powers, precarious grip and reduced safety, the last Knights of risk, a dying breed. Those powers with 1500 cubic centimeters engines, Bmw ones even with four-cylinder and single turbine, and with manual gear box and clutch ….; only to start you had to be perfect, otherwise you spun already in the pit lane … Cars with those engines (including the gear box) and today’s aerodynamic, electronics and brakes would be thrills. What a foot they had to have to drive such beasts in a street circuit, wet track and with no traction control! Berger is right to say that it took some balls. There were no buttons to push or a calming voice from the pits. No run-off areas or simulators, just by looking at a camera car you understand the differences with modern cars. And who cares that they were slower on curves! To take those cars to the edge distinguished a driver from a champion. With limited aerodynamics and those sidereal powers F1 was “power and talent“. With no “tracks”, pay-drivers and minors couldn’t race and F1 was what we all wish it to be, a category for absolute stars. Purely mechanical, everything in the hands of the driver, and all power … Races were not an overtake after another, what you like today at any cost, by creating DRS and mandatory pit stops to mix the classification up, but just to see drivers racing, knowing what they had to do to stay on the track. It was a thrill …, today you see remote-controlled toy cars one after another…. There weren’t plenty of overtaking as the driver was always trying to shave the edge between accelerating and being kicked out of the track. At each braking, each turn, the question was the same, can he do it? Watch Senna magic in Monte Carlo to keep the car on track to believe. Him but also the rest of them. That’s what was so fun, to see continuous magic tricks to keep on track cars that didn’t want to be kept on it! Today you race on “tracks”, no oversteer but on rare occasions, no going around corners flopping about, contact strictly forbidden … And there was the risk, the real one, which is the spice of drivers life. When everything is simple it’s the time of mediocrity. It’s the timid today who write down the regulations, presuming to protect us from everything and everyone. Berger, Piquet, Mansell, Prost, Lauda, Nannini didn’t need it. In mechanical Formula One you won and died. Electronics saves drivers but kills races. In those years you could choose to die for racing, today not anymore. If you lived that time, it’s difficult to have the TV on watching a GP ...; there’s nothing left, it’s all over … cars, drivers, circuits, tyres. The 1300 horse power – monsters won’t be back. To those who remember with big tears when “il Peterson” was coming out of the second Lesmo corner on opposite lock … not like now that everyone makes it flat out, is difficult to provide an answer. If you know what kind of man Berger is, if someone like him tells you that he was afraid of driving those beasts, that he was just having a great time driving them, that he still regrets them, you can possibly see how it’s useless to compare the modern–day driver to Senna, Prost, Alesi, Gilles Villeneuve, Schumacher, without disturbing the Fangio, Nuvolari, Farina, simply because they were into another sport. In the 1980s the circuits were full of spectators from Friday to Sunday. How many spectators are there today for the qualifying events? Today’s young people don’t have the same interests of the ones of old, otherwise everybody would still be on the circuit the way we were and would dream of a bike and not of an I-Phone. Once you were going to Monza to see touring car racing and you were seeing the Alfa 75 turbo with 400 horse power, the Sierra Cosworth with 500 horse power …., a few years later Tarquini, Modena, etc, … with front-wheel drive cars with not even 300 horse power ... Once Giuseppe Gabbiani said that the Lancia turbo (the one of the prototypes world championship) was so brutal that sometimes the rims could even slip inside the tyres …. There is no emotional comparison between the current F1 and the one from the ‘80s, speaking as a viewer who looks with the eyes, but especially with the heart. Technical developments have gradually lost real emotions. Men and engines from that era were talking to the heart of supporters, now they are silent, them and their cars! Today, perhaps, Senna would turn off the television too.

Robert Kubica, today Williams F1 third driver, regarding F1 cars and races in 2018: “the first thing you notice is the weight, cars are at least 60 Kg too heavy. In the slow turns, the car is like a bus, whereas in faster changes of directions it lacks manoeuvrability. That’s why today you drive by adopting some different trajectories. The race is calculated in advance. You have to follow this guideline. At most there may be some changes when tyres wear faster than expected. From outside it looks like drivers race solo: everyone tries to keep a distance so that tyres don’t overheat.”

The glorious Formula 1 of the age of monsters had players with high-sounding names, men who won everything and left a mark on that era. They won even for their strong egoism and their luck / ability to be driving a winning car. The following three men, however, even though winning very little or nothing, have been a part of it in their own right. Talented and selfless drivers, very quick, intelligent, loyal and sincerely enthusiasts, true knights of risk and heroes of that time. Their words on those years reinforce the conviction that they were better tempered, on a whole other level. Not only as drivers but as people. Infinite respect, chapeau.

Gerhard Berger, not a top driver but with utmost character and as brave as can be. Wealthy long before racing in F1, he loves women and jokes.

Gerhard Berger with Ayrton Senna.

Proverbial the one on Senna in an Australian hotel, when he filled the bed in the Brazilian’s room with animals. Ayrton name-called furious the mate, saying: “I spent the last hour to capture 12 frogs in my room!” Berger replied: “did you find the snake?” A nice man, smart and intelligent, Gerhard said concerning the old F1: “Forget anything after, the 1986 Turbo cars really were rockets, and to handle them I really think you had to be a man,”. And again the Austrian: “the biggest difference between the old F1 cars and the new ones mainly concerns constituent materials. In the ‘70s there were aluminium chassis, while in the ‘80s arrived those all-composite. That saved our life: in the ‘70s, each year were losing their lives one or two drivers; thanks to new materials plenty of us survived. I was born with Formula 1 in the ‘80s but I think that the apex was reached at the confluence of the ‘60s and ‘70s: that one to me is the golden age, as cars were spectacular and fast. But it was the driver to make a difference. In contemporary Formula One it’s technology to make a difference.”

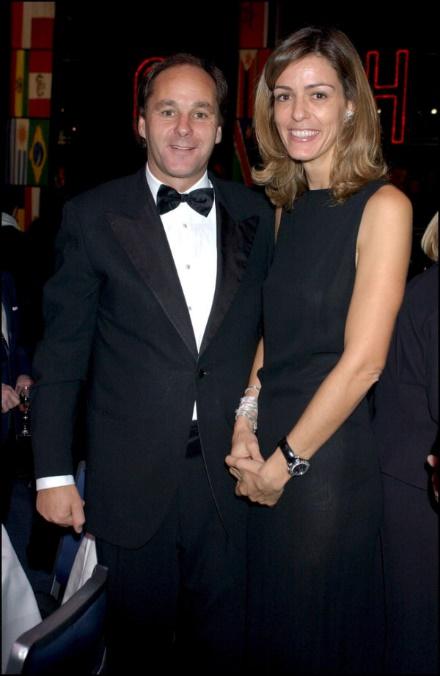

Gerhard Berger with his girlfriend Helene.

If we needed to talk about Berger’s Latin lover career, a book wouldn’t be enough.

To a boyfriend cheated on, that he invited for a drink, Gerhard once said: “if she betrays you, she doesn’t deserve you. I did you a favour, buy me a drink.”

Berger, Ferrari 412 T2, in 1995.

The Austrian recalls his accident at Imola in 1989, admitting to have seen his whole life walking by him, convinced as he was that he was not going to live through it. When his Ferrari ran off the track at the Tamburello curve, hiting barriers going 256 kilometers an hour, the impact destroyed the car which crawled 100 meters before catching fire. “As soon as I hit barriers I thought ‘man, Gerhard you won’t make it, you won’t survive’. Thus I put my arms across my chest and I prepared to impact.” Berger fainted when Sid Watkins showed up: “the first thing I saw when I woke up was that there was professor Watkins sitting, who was trying to stuck a tube down my throat. I was injured, so I realized that I was still alive. I had a broken rib, chemical burns on the body as a result of the fuel leaked and a second-degree hand injury.”

Gerhard Berger with Michael Schumacher.

Talking about Schumacher and Senna, his very good friend, Berger sees lots of connotations in Michael that belonged to the Brazilian. “Ayrton and Michael are very similar in the way they meet the competitive challenges that come at them. When I talk to Michael I always think about Ayrton, he reminds me many competitive aspects of him, the way in which he analyzes events, and the openness he has of everything. I don’t see anyone else in Formula One at the moment, capable of being compared with Michael. I had a great sensitivity for the technical aspects, about what you needed to change in the car to make it faster, but they have always had something extra, and I don’t see others who are focusing their attention on certain points like them. I was trying ten different things at the same time, they tried two, and they always managed to get 100 percent from their performances. You can try to solve and fix ten problems together, one by one and go faster, but what it really makes the difference is to identify two or three of them, and when you solve them, they prove of being those that make you make a real difference. Michael has this ability, and Ayrton had the same quality. The car has to be understood in all its aspects, understeer, bumps, or whatever, and both were understanding immediately where they had to act, what was the key factor to act on to narrow the gap from the best. Very many drivers don’t have this talent.” After the Brazilian’s accident Berger says: “Sid Watkins was at the hospital with Ayrton, and told me that his condition was very bad. Very. There was no hope of saving him. They accompanied me to his room and that was the last time I found myself before him. I spent a few minutes with him within those four walls, and I couldn’t do anything. I found myself suddenly with the truth of reality. In the driving life, in a way, you always feel a little bit ready about dying, and in fact during my career I lost a lot of adventuring companions and friends like Alboreto, De Angelis, Winkelhock, Gartner. However the relationship that bound me to Ayrton was stronger than it was with the other mentioned. He was a dear friend of mine, and although you would have been prepared for that, given the hazardous nature of our profession, it was a severe blow anyway. It hurt so much.” Berger believes Senna’d be the best: “Ayrton was a special man. He had a way of standing before people, maybe someone was unhappy with his character, but he had a good heart and he knew how to choose the people around him. He loved his country, he was Brazilian one hundred percent with a Latin character. You can always say in your life to have someone special as a point of reference. Enzo Ferrari has been it, but I speak not only in motoring, he could be a president, a leader, or just normal people with special qualities. A person is like that not because of the office he holds that gives him authority, but on the contrary you must have the authority, the charisma yourself. Ayrton is one of these people definitely. Professionally speaking, Schumacher is as good as Ayrton was, as I said before, but with Ayrton’s character there is one in a million. I miss him as a colleague, but even more so as a friend, a great friend, and I won’t never be able to forget about him.”

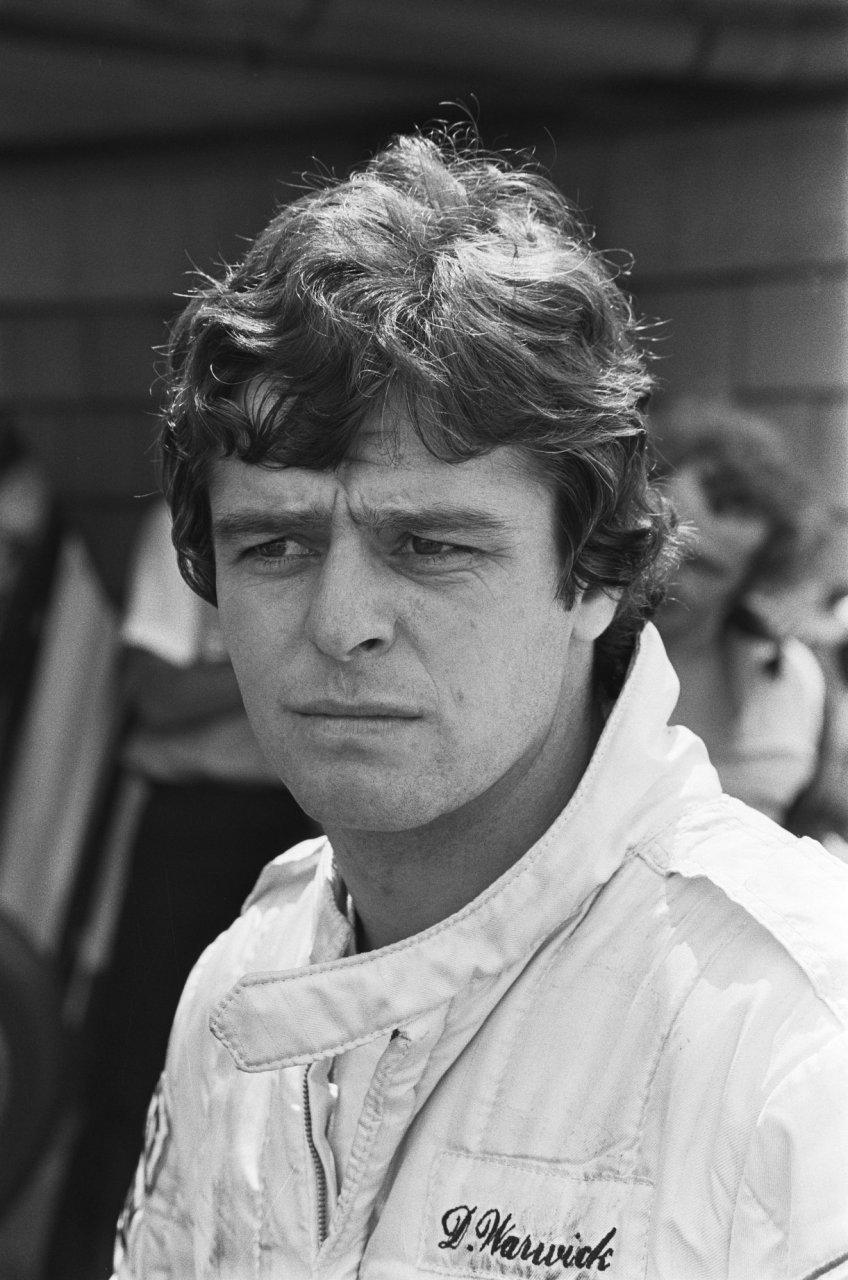

Martin Brundle, Belgium 1988.

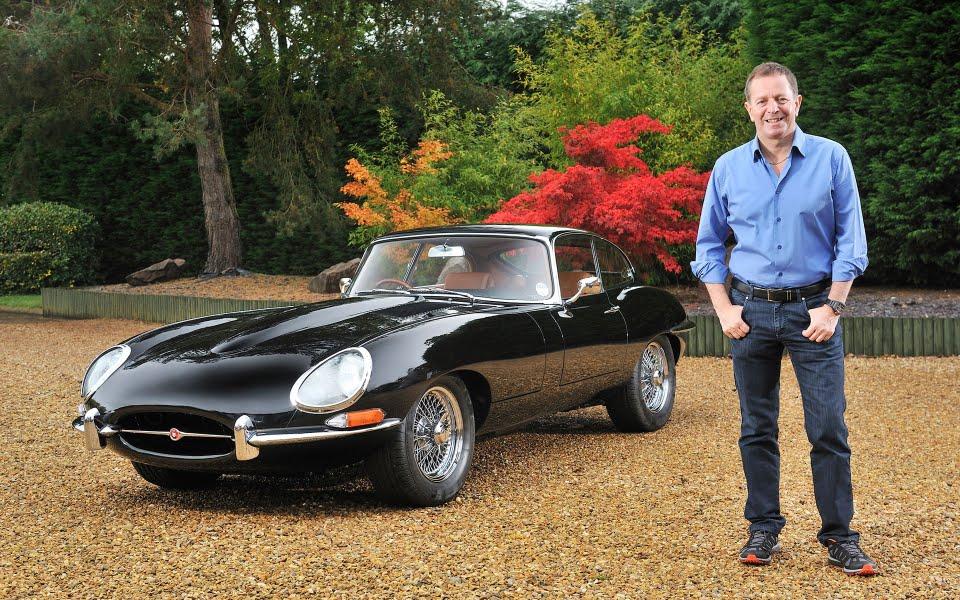

Martin Brundle, brave and fast. Good judge of cars, at the end of his career he got his dream E-Type Jaguar made by Eagle, ‘Elvis’, as it’s known in his family.

Brundle’s Jaguar E-type s1 42 by Eagle.

This extraordinary car was delivered to Martin in time for his road trip to the Spa GP in 2012 for Sky F1. So impressed was he that, instead of returning home, he drove his E-Type onto Monza for the Italian GP and then took the long way home through the Alps. “As a former Formula One driver, I have earned the right to have an opinion about the sport, and probably know as much about it as anybody else. I have attended approaching 400 Grands Prix, 158 as a driver. I have spilt blood, broken bones, shed tears, generated tanker loads of sweat, tasted the champagne glories and plumbed the depths of misery. I have never been more passionate about F1,” he said. "I worked like a dog as a driver and never had the recognition I do now. I left F1 with enormous frustration and I still feel I had an awful lot more to give. Oh yes, I could unquestionably have been world champion. I had the ingredients but I didn't put them together. In a sportscar I was invincible. In F1 I allowed other things to distract me from the goal. I should have been world champion. But of course all drivers think that."

1992 Italian GP. Brundle, Senna and Schumacher.

On his relationship with Schumacher, notoriously not good, Brundle says: "it's not true that Michael won't speak to me. But it is true he speaks to me reluctantly.

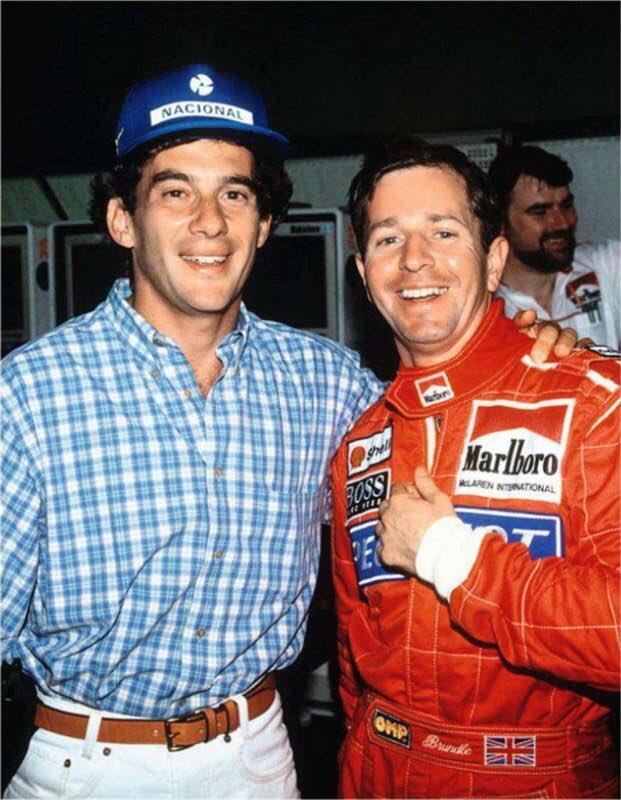

Ayrton Senna with Martin Brundle.

We used to be good mates but he's like Senna - he reads his press. I criticised his willingness to run people off the road. I meant it and I stand by it. It's pretty weak on his part not to accept that."He also said on his present job: "the only thing that gets me going remotely in the same way as a qualifying lap round Monaco or those seconds on the grid waiting for a race to start - the nervousness, determination, fear of failure - is live TV. But even that is only about a third as much of a thrill." 2017 F1 cars will be "brutal," says Martin. “It’s certainly going to be different; the cars are going to be brutal. In theory, I think we’ve gone the wrong way in terms of making the racing better. You hear some stories that some corners will be reclassified as straights. With the amount of power and torque the (current) cars have got - although they don’t sound very good - I’ve driven the Mercedes, Force India and Ferrari now. They are amazing engines to drive, endless amounts of power - even though they sound (like) rubbish. Put that into a car with a lot more downforce and 25 percent bigger tires - the whole thing is 11 percent wider - it is going to be a monster to drive. Whether it makes better racing or not, we’ll find out. The braking distances will be shorter, too. More grip means they might be braking four or five meters later. That means you have less opportunity to overtake." Brundle is married to Liz and they have a daughter and a son.

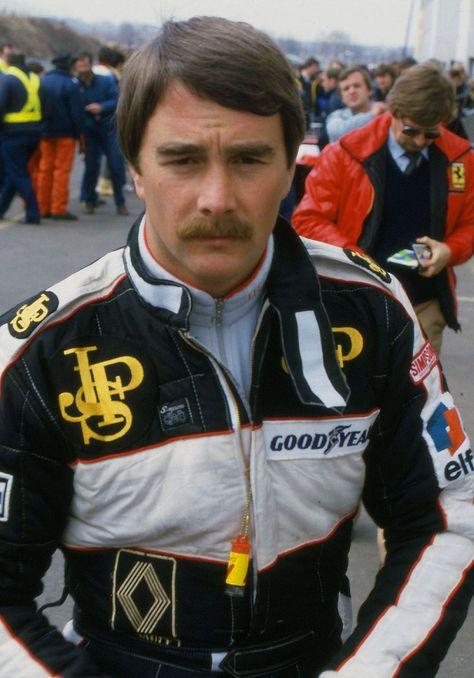

Former GP driver Briton Derek Warwick is yet another voice has been added to concerns that Formula 1 must change. He says rules like those mandating long-life gearboxes and engines are “killing the sport for TV and spectators. Most of them [the drivers] are only doing 10 laps in practice because they are saving something — whether it be engine, power unit, gearboxes.” So they [the rules] are kind of backfiring a little bit, the principle is right but something needs to change to make F1 exciting, to make the drivers look like gladiators.” Instead, Warwick argues, the cars allow teenagers like Max Verstappen to leap almost straight from karting to F1 points. In contrast, the cars of old were animals, Warwick said, “we had 1600 horse power and downforce that made your eyes pop out. [Today] you see them doing a test and within ten laps they are two tenths off the lead driver. That didn’t happen in my day, therefore these cars must be easier to drive. We just need to take a step back, have a good look at ourselves before it is too late.” Brave and humanly of substance like an English gentleman has to be, Derek came to be known on tracks when he was racing at Toleman, Renault, Brabham and Arrows in Formula 1. Always nice, open, funny, proud that he was paid to drive a Formula 1 car and not vice versa: ‘people forget that even someone like Senna, arguably one of the greatest racing drivers ever, came with a pot of gold behind him. These guys drove the best cars with the best budgets – that’s why they won Formula One championships.’ Ayrton Senna's refusal to let Derek join him as teammate at Lotus left Warwick without a team for the 1986 season. ‘Senna screwed with my career. I returned to F1, but raced with lower-grade teams, whereas I do believe I could have won Grands Prix and been world champion.’ Following the death of Elio de Angelis in a testing accident, however, Warwick was invited to take his place at Brabham. "I got a phone call from Bernie, who said that he really appreciated the fact that I didn't call him five minutes after Elio had died and would like me to drive for him”. And, on Gilles’ death: ‘I cradled Gilles Villeneuve in 1982 at Zolder in Belgium,’ recalls Derek. ‘I was in the hotel room with my wife, Rhonda, when Gilles’ death was announced. We went to bed that night crying. I woke up the next morning, showered, started to get ready and Rhonda asked me, “what are you doing?” I replied, “it’s race day”. That’s how black and white it had to be to race. During the ten years or so that I was in Formula One, 12 racing drivers competing in top-level motorsport died, including my little brother. But I think because I was around in the tough times in Formula 1 when a lot of people were being killed, I think you developed an ability to cut things out. Right from the early days, I built a safe in my brain for when people were injured or killed. I was the first there when Gilles Villeneuve was killed in Zolder. I was there when Patrick Depailler was killed at Hockenheim. I’m really a softie. How I can be so hard on the other side, I don’t know. But I had this ability and I used to unlock the safe, (Derek indicates the side of his head at this point) put them in, lock it up. I would not see them for the rest of the weekend until Sunday night. Then the Sunday night, all the emotion would flow out. So when Paul (his brother) died, I didn’t know whether I’d race or not.”

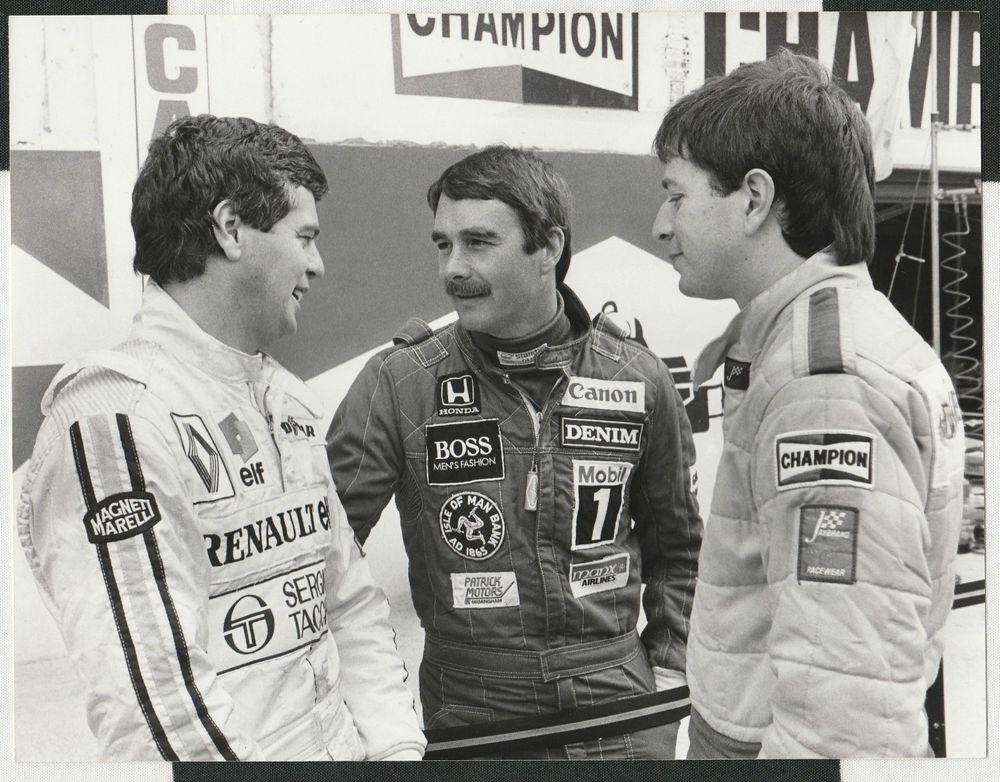

Derek Warwick, Nigel Mansell and Martin Brundle.

And recalling again his time in F1: “I often think about the guys driving today versus my old time in F1. I think I’ve picked the perfect time to be a racing driver. It was dangerous, it was fast, we had enormous power, we had enormous downforce, the skirted cars, we had one lap qualifyings, we had access to all areas. Now I think with social media, with cameras with more angles, with data, with engine recovery, I feel sorry for today’s racing drivers, I really do. I think we had more pure, raw racing cars and even though I never really drove good cars I don’t even regret one second of my F1 career.” ‘I had the best life in the world,’ he says. ‘I was a Grand Prix driver in the Eighties and early Nineties, when you could have fun. You were a superstar and everything was at your beck and call. If you wanted to be a little prima donna you could be, but it never occurred to me to be that way because I’ve got a great family who used to keep my feet planted firmly on the ground.’ It was this humble approach to life in the fast lane that helped him to win many friends during a career in which he started 147 F1 GP, achieved four F1 podium finishes and triumphed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans race and the World Sportscar Championship. Some consider Warwick to be the best F1 driver never to win a single race. About his battle to overcome bowel cancer he said: ‘that really knocked the wind out of my sails and I wanted a bit more “me time”. He has been married to Rhonda for more than 40 years and the couple has two daughters.

Nigel Ernest James Mansell (GBR) (John Player Special Team Lotus), Lotus 95T - Renault Gordini EF4 1.5 V6 (t/c) (finished 3rd) 1984 Dutch Grand Prix.

Of the turbo era Nigel Mansell said on his 68th birthday: "today’s drivers will never know what it means to drive a real F1. The Circus will never return to the turbo era cars of the 1980s. Driving those cars was the most exhilarating and scary thing I've done in my life. In qualifying you had up to 1500 horsepower available. At every single corner the car was literally trying to kill you".

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment