In 1982, at the Belgian GP, Sid Watkins, F1 neurosurgeon, was the first to reach the scene of Gilles Villeneuve's accident, performing emergency procedures. «There were parts of his car everywhere, he was still breathing and moved his pupils. I placed a tube into his windpipe for ventilation with his heart in normal condition.” Gilles was airlifted by helicopter to University St Raphael Hospital in Leuven, and Watkins spoke to Villeneuve's wife Joann who was in her home in Monaco when Jody Scheckter informed her of the news. Joann flew to Belgium along with Scheckter's wife Pam to speak with Watkins. Although the driver had effectively been killed on impact, Watkins and the hospital medical team kept Villeneuve alive on a respirator until his wife arrived and the doctors consulted specialists worldwide. “At Leuven hospital we realized that the fracture of the neck was fatal. I brought in the wife, I explained the situation to her, then,” Watkins reported, “we switched him off.” He died at 21:12.

Really fast over one lap, the champion of the heart and impossible overtaking. Loyalty and authenticity from another time. Not a man for world titles but for individual feats, that are recalled today maybe more than the victories of a whole championship. Villeneuve made the impossible happen. He seemed invincible, immune to accidents. His body remained intact on the outside even after the fatal flight, the last feat of Gilles. Sometimes you die as you lived and this has never been more real than with him.

Gilles Henri Villeneuve, a Canadian racing driver born in 1950, started his racing career early in snowmobile racing in his native province of Quebec. An enthusiast of cars and fast driving from an early age, he moved into single seaters, winning the US and Canadian Formula Atlantic championships in 1976, before being offered a drive in F1 with the McLaren team at the 1977 British GP.

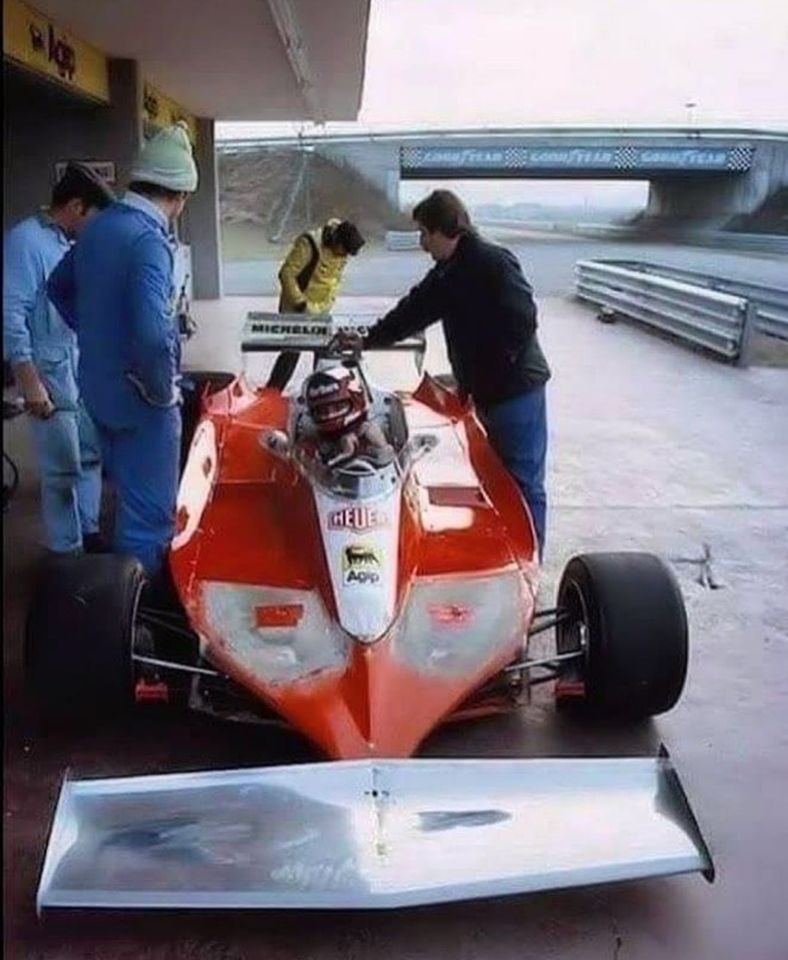

Gilles Villeneuve tests a radical evolution of the Ferrari 312 T3.

A year later he was asked to join the Ferrari team for the end of the season and, from 1978 to his death in 1982, drove for the Italian team. As he had later remarked: "if someone said to me that you can have three wishes, my first would have been to get into racing, my second to be in Formula One, my third to drive for Ferrari ..." His races promised a bright career, and he quickly became a favourite among Formula One fans. Gilles Villeneuve, a winner of only 6 Grand Prix, and without a single championship title to his name in his short career. The horrific accident that took his life has left a void in all of our hearts. His death was untimely, but his legacy lives on forever. His son Jacques became F1 world champion in 1997.

Villeneuve was born in Richelieu, a small town just outside Montreal, in the largely French-speaking province of Quebec in Canada and grew up in Berthierville. In 1970, he married Joann Barthe, with whom he had two children, Jacques and Mélanie.

During his early career Villeneuve took his family on the road with him in a motorhome during the racing season, a habit which he continued to some extent during his F1 career. He often claimed to have been born in 1952. By the time he got his break in F1, he was already 27 years old and took two years off his age to avoid being considered too old to make it at the highest level of motorsports. Villeneuve started competitive driving in local drag-racing events, entering his road car, a modified 1967 Ford Mustang.

Money was very tight in his early career. He was a professional racing driver from his late teens, with no other income. In the first few years the bulk of his income actually came from snowmobile racing, where he was extremely successful. He credited some of his success to his snowmobiling days: "every winter, you would reckon on three or four big spills — and I'm talking about being thrown on to the ice at 100 miles per hour. Those things used to slide a lot, which taught me a great deal about control. And the visibility was terrible! Unless you were leading, you could see nothing, with all the snow blowing about. Good for the reactions — and it stopped me having any worries about racing in the rain."

After Villeneuve impressed James Hunt by beating him and several other GP stars in a non-championship Formula Atlantic race at Trois-Rivières in 1976, McLaren team offered the Canadian a F1 deal for up to five races in a third car during the 1977 season. Villeneuve made his debut at the British GP and John Blunsden commented in The Times that: "anyone seeking a future World Champion need look no further than this quietly assured young man."

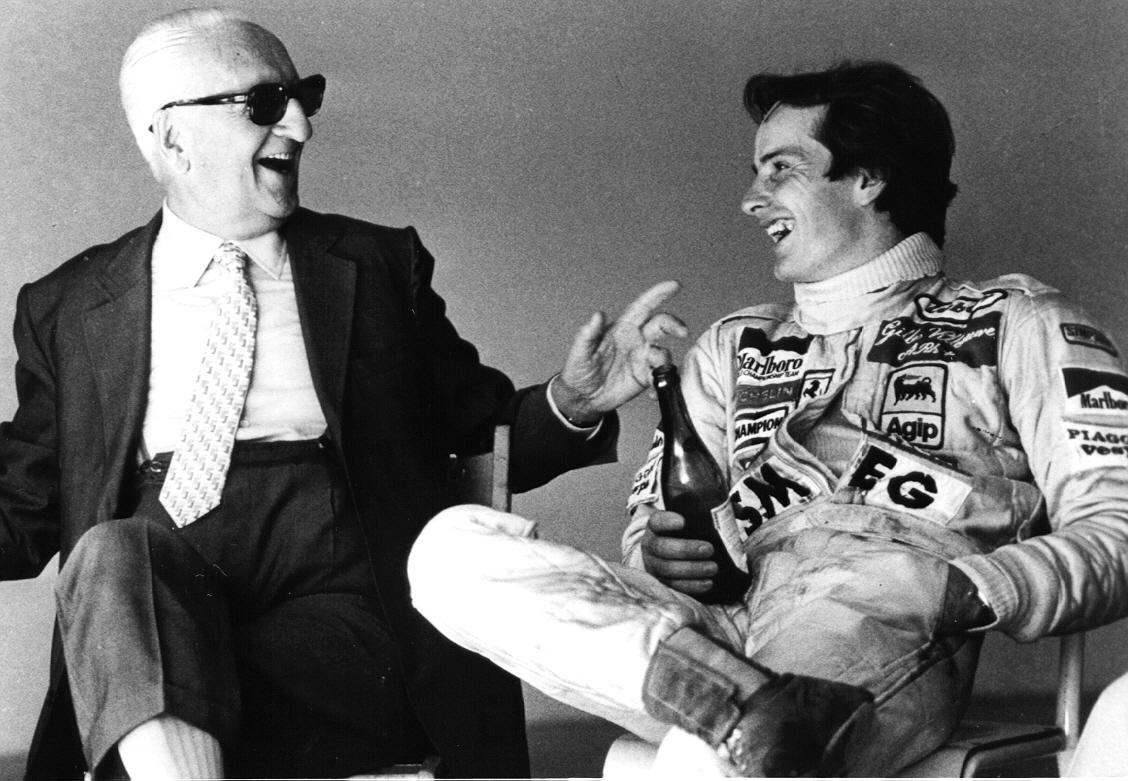

Enzo Ferrari with Gilles Villeneuve after a test session in 1980 at Imola.

In August 1977 he flew to Italy to meet Enzo Ferrari, who was immediately reminded of the pre-war European champion Tazio Nuvolari: "when they presented me with this 'piccolo Canadese' (little Canadian), this minuscule bundle of nerves, I immediately recognised in him the physique of Nuvolari and said to myself, let's give him a try."

Gilles Villeneuve at the Japanese GP in 1977.

In the last race of the 1977 season, the Japanese GP at the Fuji Speedway, Gilles retired on lap five when he tried to outbrake the Tyrrell P34 of Ronnie Peterson. The pair banged wheels causing Villeneuve's Ferrari to become airborne. It landed on a group of spectators watching the race from a prohibited area, killing one spectator and a race marshal and injuring ten people.

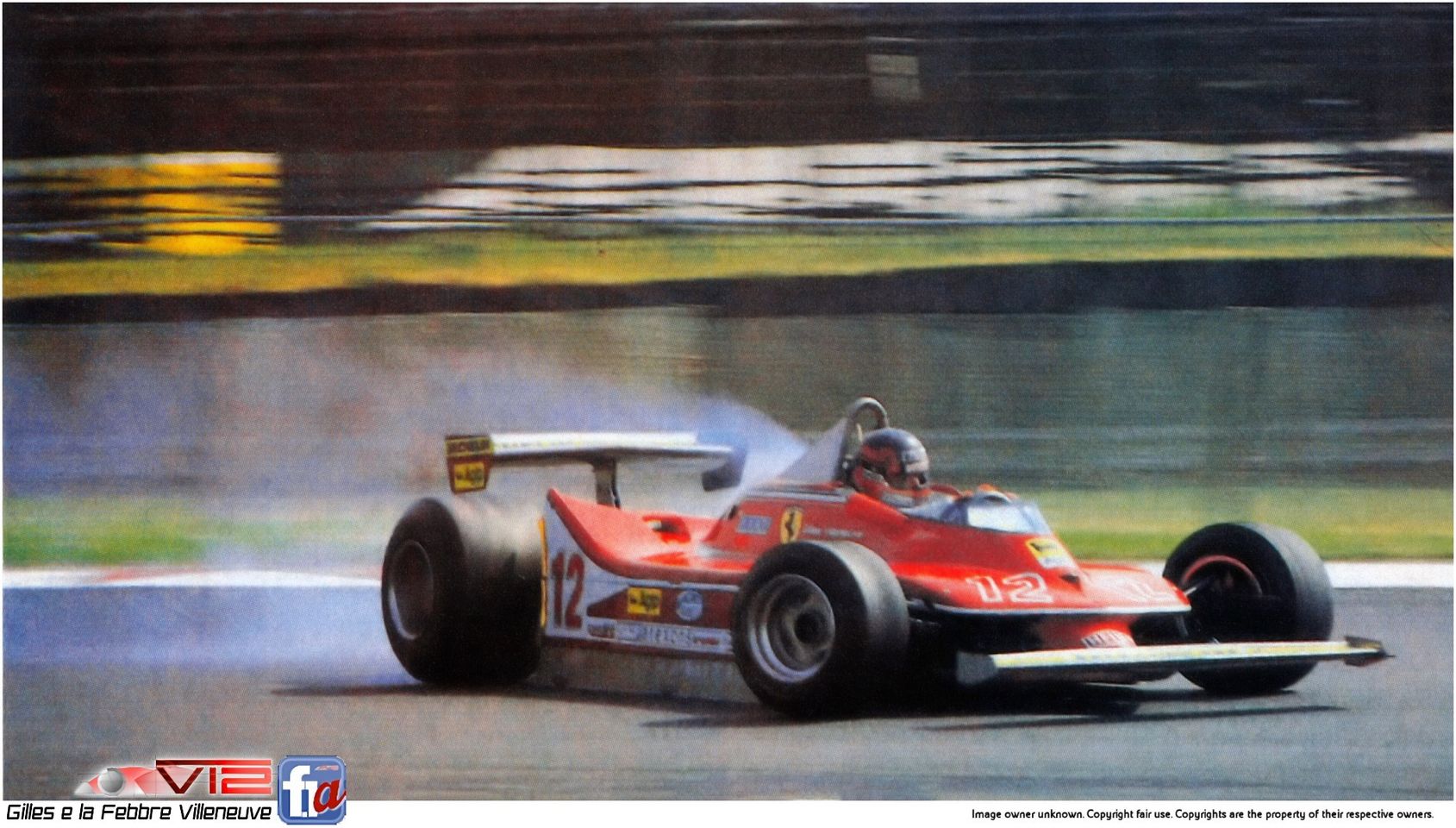

Gilles Villeneuve in 1978.

At the 1978 season-ending Canadian GP in Montreal Villeneuve scored his first GP.

Gilles was joined by Jody Scheckter in 1979 and won three races during the year and even briefly led the championship after winning back to back races in USA and South Africa.

However, the season is mostly remembered for Villeneuve's wheel-banging duel with René Arnoux in the last laps of the 1979 French GP. Villeneuve commented afterwards, "I tell you, that was really fun! I thought for sure we were going to get on our heads, you know, because when you start interlocking wheels it's very easy for one car to climb over another." At the Dutch GP a slow puncture collapsed Villeneuve's left rear tyre and put him off the track. He returned to the circuit and limped back to the pits on three wheels, losing the damaged wheel on the way. On his return to the pits Villeneuve insisted that the team replace the missing wheel, and had to be persuaded that the car was beyond repair. Villeneuve might have won the world title by ignoring team orders to beat Scheckter at the Italian GP, but chose to finish behind him. During the extremely wet Friday practice session for the season-ending US GP, Villeneuve set a time variously reported to be either 9 or 11 seconds faster than any other driver. His teammate Jody Scheckter, who was second fastest, recalled that "I scared myself rigid that day. I thought I had to be quickest. Then I saw Gilles's time and — I still don't really understand how it was possible. Eleven seconds!" The 1980 season was a complete disaster for Ferrari and Villeneuve only scored six points in the whole campaign in the 312T5 which had only partial ground effects. Scheckter scored only two points and retired at the end of the season.

Gilles Villeneuve, biplane Ferrari, at the 1982 United States Grand Prix in Long Beach.

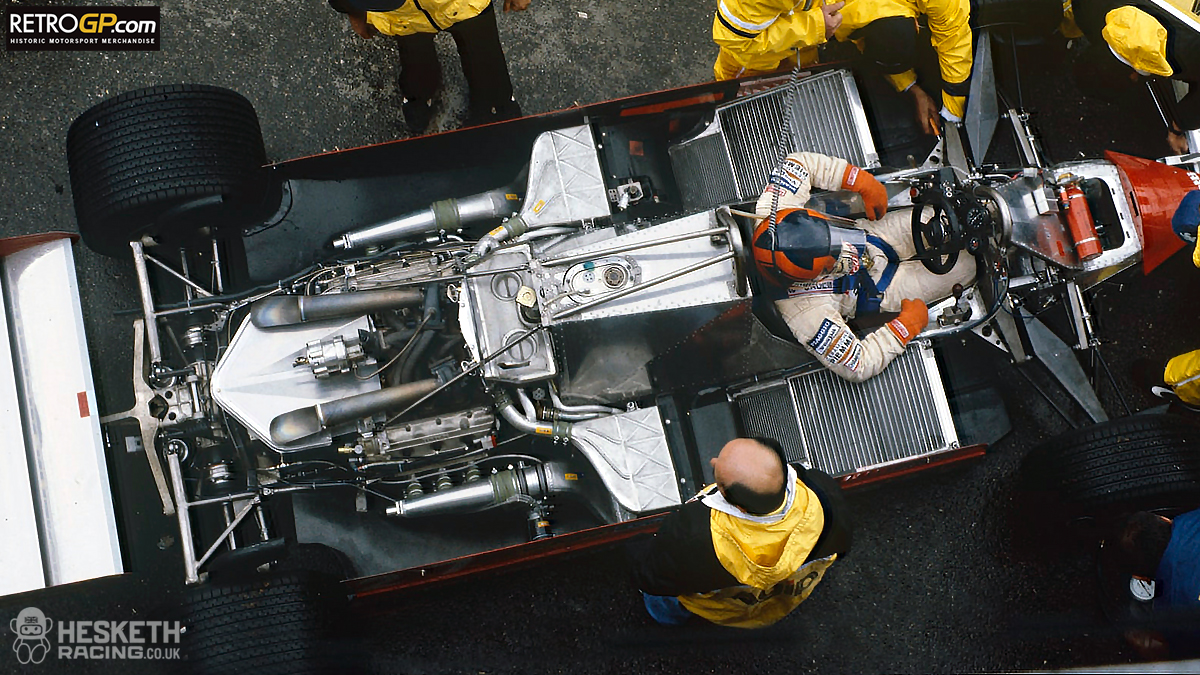

In 1981, Ferrari introduced their first turbo engined F1 car, the 126C, which produced tremendous power but was let down by its poor handling.

Gilles Villeneuve with his 650hp Ferrari 126C.

Villeneuve was partnered with Didier Pironi who noted that Villeneuve "had a little family [at Ferrari] but he made me welcome and made me feel at home overnight ... [He] treated me as an equal in every way." Villeneuve won two races during the season. At the Spanish GP the Canadian kept five quicker cars behind him for most of the race using the superior straight-line speed of his car. Harvey Postlethwaite, who was hired by Ferrari to design the follow-on and much more successful 126C2, later commented on the 126C: "that car ... had literally one quarter of the downforce that, say Williams or Brabham had. It had a power advantage over the Cosworths for sure, but it also had massive throttle lag at that time. In terms of sheer ability I think Gilles was on a different plane to the other drivers. To win those races, the 1981 GPs at Monaco and Jarama — on tight circuits — was quite out of this world. I know how bad that car was."

Gilles Villeneuve drives unsighted at the 1981 Canadian Grand Prix.

At the 1981 Canadian GP Villeneuve damaged the front wing of his Ferrari and drove for most of the race in heavy rain with the wing obscuring his view ahead. There was a risk of being black flagged but eventually the wing became detached and Villeneuve drove on to finish third with the nose section of his car missing. At the 1982 San Marino GP, in order to conserve fuel and ensure the cars finished the Ferrari team ordered both drivers to slow down. Villeneuve believed that the order also meant that the drivers were to maintain position but Pironi passed Villeneuve. A few laps later Villeneuve re-passed Pironi and slowed down again, believing that Pironi was simply trying to entertain the Italian crowd. On the last lap Pironi passed and aggressively chopped across the front of Gilles in Villeneuve corner and took the win. Villeneuve was irate as he believed that Pironi had disobeyed the order to hold position. Meanwhile, Pironi claimed that he had done nothing wrong as the team had only ordered the cars to slow down, not maintain position. Villeneuve stated after the race "I think it is well known that if I want someone to stay behind me and I am faster, then he stays behind me." Feeling betrayed and angry Villeneuve vowed never to speak to Pironi again. In 2007, former Marlboro (company which sponsored Pironi while he was at Ferrari) marketer John Hogan said: "neither of them would ever have agreed to what effectively was throwing a race. I think Gilles was stunned somebody had out-driven him and that it just caught him so much by surprise." A comparison of the lap times of the two drivers showed that Villeneuve lapped far slower when he was in the lead, suggesting that he had indeed been trying to save fuel.

Gilles Villeneuve in his Ferrari at Zolder in 1982.

On May 8, 1982, Villeneuve died after an accident during the final qualifying session at Zolder. At the time of the crash, Pironi had set a time 0.1s faster than the Canadian for sixth place. Gilles was using his final set of qualifying tyres. Ferrari race engineer Mauro Forghieri said that Villeneuve, although pressing on in his usual fashion, was returning to the pits when the accident occurred. If so, he would not have set a time on that lap.

This is the last photo taken of the Ferrari n. 27, a few hundred meters before the fateful curve where it will collide with the March of Jochen Mass.

With eight minutes of the session left, Villeneuve came over the rise after the first chicane and caught Jochen Mass travelling much more slowly through Butte, the left-handed bend before the Terlamenbocht double right-hand section. Mass saw Villeneuve approaching at high speed and moved to the right to let him through on the racing line. At the same instant Villeneuve also moved right to pass the slower car. The Ferrari hit the back of Mass' car and was launched into the air at a speed estimated at 200–225 km/h. It was airborne for more than 100 m before nosediving into the ground and disintegrating as it somersaulted along the edge of the track. Villeneuve, still strapped to his seat, but without his helmet, was thrown a further 50 m from the wreckage into the catch fencing on the outside edge of the Terlamenbocht corner. John Watson and Derek Warwick pulled Gilles, his face blue, from the fence.

At the funeral in Berthierville Jody Scheckter delivered a simple eulogy: "I will miss Gilles for two reasons. First, he was the most genuine man I have ever known. Second, he was the fastest driver in the history of motor racing. But he has not gone. The memory of what he has done, what he achieved, will always be there." At the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari a corner was named after him and a Canadian flag is painted on the third slot on the starting grid, from which he started his last race. There is also a bronze bust of him at the entrance to the Ferrari test track at Fiorano. At Zolder the corner where Villeneuve died has been turned into a chicane and named after him. The track on Notre Dame Island, Montreal, host to the F1 Canadian GP, was named Circuit Gilles Villeneuve in his honour. In Berthierville a museum was opened in 1992 and a lifelike statue stands in a nearby park which was also named in his honour. The number 27, the number of his Ferrari in 1981 and 1982, is still closely associated with him by fans.

Gilles Villeneuve pushes the Ferrari to its limits.

Niki Lauda said of him: "he was the craziest devil I ever came across in Formula 1 ... The fact that, for all this, he was a sensitive and lovable character rather than an out-and-out hell-raiser made him such a unique human being".

You left us in a day of May where you wanted to show that you were the best. It was useless Gilles, we already knew it.

Gilles Villeneuve: a few stories from his business manager, Gaston Parent. 17 July 2012.

In 2002, as I was working on a TV special on Ferrari, I probably conducted the last interview with Gaston Parent, Gilles Villeneuve's manager. The former businessman died less than 12 months after that interview.

In 1976, Gaston Parent was a prosperous and acute businessman in the fields of marketing and advertising. He got to know Gilles Villeneuve as the young driver needed money to race in Formula Atlantic.

At the time, Villeneuve badly needed $5,000 to compete in a Formula Atlantic race in Halifax to secure the Canadian title. Parent was impressed by the young charger. He decided to pay the bill.

Gaston Parent. Photo: Musée Gilles Villeneuve.

Villeneuve raced in Halifax, won the race and the title. Weeks later, Parent attended the Trois-Rivieres Atlantic race where he beat F1 World Champion James Hunt who was driving an identical car.

Early 1977, Teddy Mayer of the McLaren F1 team proposed a four-race contract to Villeneuve. “I was too busy to go in England. I told Robert St-Onge (his right-hand man) that he would go with Villeneuve to sign the contract,” Gaston Parent told us. And the two later returned to Canada with a McLaren contract in pocket.

Villeneuve raced a year-old McLaren in the British Grand Prix in Silverstone and made a strong impression.

A few weeks later, Mayer faced a dilemma. He had signed Frenchman Patrick Tambay as a teammate to James Hunt for 1978 and he needed to get rid of Villeneuve. “Negotiations began between Teddy Mayer and Ferrari. Mayer did not want Gilles to go to Wolf – the new Canadian team. He wanted him to go to Ferrari,” Parent explained.

“One day, Gilles called me. He was overly excited. He said that Ferrari had called him and offered him a contract. We needed to go in Italy. In fact, Niki Lauda had decided to quit Ferrari and the Italian team needed a replacement driver. I did not want to go in Italy. But my friend Walter Wolf - who was the owner of the new Wolf Formula 1 team – convinced me to go.”

Villeneuve was ecstatic about the idea of meeting Mr. Enzo Ferrari in person. “For me, it was totally different,” Parent told us. “I was a Canadian businessman who was going to Italy to meet an Italian businessman. Period.”

Both arrived in Milan. “A character named Mortara, close to Mr. Ferrari, drove us to Modena. We came to visit Mr. Ferrari. A barrier opened and we entered the field. We got out of the car and entered his office. It was a large room with shelves full of trophies. In the center, there was only a very ordinary table and five chairs. An electric light bulb hung over the table. It looked like we were in an old Italian movie. Enzo Ferrari then entered with his translator and accountant. We started to talk. Gilles was so obsessed with the idea of driving for Ferrari that he would have said yes to everything. I had to calm him down several times!"

During the flight between Montreal and Milan, Villeneuve had told Parent that he wanted permission to continue doing risky activities like skiing, driving his 4x4, boating and the like.

“I told Mr. Ferrari that Gilles wanted to be the owner of his body. You have to believe that I used unusual words! Because Ferrari looked at me and asked me if I was a lawyer. I told him no. Then he asked Gilles if he was a lawyer. No. Ferrari asked me to repeat my question, which I did using the same words. And he accepted. In fact, Ferrari understood, by mistake, that Gilles wanted to be the owner of his body, in fact of his racing suit! That Gilles wanted to negotiate his own personal contracts. This is not what we had in mind, but that we got by mistake! Parent exclaimed.

Interesting fact: no contract was signed. “Enzo Ferrari showed us a document which was a letter of intent which had 19 points and entitled 'by verbal agreement'. Ferrari explained to us that no one signed a contract in Italy because the tax authorities demanded that the same amount that was mentioned in the contract be put as a guarantee. This meant that, if Ferrari hired Villeneuve for a million dollars, Ferrari had to hand over another million to the tax authorities. And, of course, Ferrari would never see that amount again. But, despite the explanations, I wanted to have a contract. Enzo Ferrari then looked me in the eye and said 'when I give my word, there is no problem. We don't need a contract ...' So we left the office with this letter of intent,' said Gaston Parent.

Fiorano track. Photo by Ferrari.

The latter continues his story. “The next day, Gilles tested on the Fiorano circuit. Mauro Forghieri, the technical director, was not convinced of Gilles' development skills. On the third flying lap, Gilles lost control of the car and spun through the long grass. He quickly returned to the track and finished his lap. After about an hour of testing, he had broken the track record. Quietly, I heard Enzo Ferrari and his business partners talking to each other and saying 'il campione del mondo ... '.

Gilles Villeneuve during his first test in the Ferrari 312 T2 at Fiorano. Photo by Ferrari.

The following day, Gilles Villeneuve and Gaston Parent were able to measure the importance of the new status of the Quebecer. The two friends had to take the plane back to Montreal. “But Alitalia had been under the strike of its staff for a few days. It was total chaos at Milan airport. At the counter, we are told that there are no more seats on the next flight to Montreal. I asked to see the director of operations and we started to chat. Suddenly, he saw Gilles holding his new molded racing seat in his hand. He cried out 'Villeneuve'! He couldn't believe he had the new Ferrari driver in front of him! Everything was instantly arranged and we were able to have three seats in business class: one for Gilles, one for me and another one for Gilles' seat!" Parent exclaimed.

In Maranello, home of Ferrari, Gilles was treated like a king. “In great secrecy, Gilles attended Italian lessons at Berlitz. One day he arrived at Ferrari and spoke Italian with his mechanics and engineers. They were extremely impressed. When he was in Italy, Gilles stayed at the Fini hotel in Modena. He was the big star. He could do anything on the road: U-turns, drive in the wrong direction and on the sidewalks, everything! It was crazy! One day, he was stopped by the police for speeding. He searched in his bag and brought out six photos of him. He signed them and gave them to the police officer. He got away with it!” Gaston Parent concluded on the phenomenon Gilles Villeneuve.

Gilles Villeneuve and the Italians, a love story

Gilles Villeneuve miming taking a photo at the 1981 Canadian Grand Prix, a gesture that makes his brother Jacques laugh. Photo by Bernard Brault, archives La Presse.

To make Italians' eyes sparkle - and perhaps find the beginnings of a tear - just say one name: Gilles Villeneuve. In the land of Ferrari, the passion for the ‘Canadesino’ still makes hearts beat faster, 31 years after his death.

Updated on 06 September 2013. By Mali Ilse Paquin, LA PRESSE.

There is one object that Giorgio Meroni never parts with: a photograph taken on May 7, 1982, the last one during Gilles Villeneuve's lifetime. It shows the driver at his last supper in Zolder, the Belgian city hosting the Grand Prix, surrounded by his friends, including Giorgio Meroni, then 35 years old.

Following the accident, journalists offered him thousands of dollars for this photo. "I didn't want to know anything," Meroni remembers. "I was in shock."

Today president of a Ferrari club, Giorgio Meroni organizes two Ferrari gatherings per month in honor of his friend. Thus, on June 30, some forty gleaming racing cars formed a heart in the magnificent region of Lake Como.

"All this for Gilles, the greatest of all. He is still in the hearts of the Italians," says Meroni.

One of their own

Giorgio Meroni may not be wrong. Gilles Villeneuve is at the top of the pantheon of sports in Italy, alongside Tazio Nuvolari, the national hero of motor racing.

Gilles Villeneuve, René Arnoux and a Ferrari Mondial.

The duel in Dijon with René Arnoux, the betrayal of his teammate Didier Pironi at Imola, the Italians know the legend by heart.

"His name is immensely popular with our fans, even the young ones," confirms Renato Bisignani, Ferrari spokesman, to La Presse. “It's incredible when you know that he died without a world title to his name."

The 30th anniversary of his death was celebrated throughout 2012, notably at Ferrari's headquarters in Maranello.

A superb special issue of La Gazzetta dello Sport dedicated to the "Canadesino" (the nickname Enzo Ferrari gave Villeneuve) was reprinted three times due to high demand, for a total of 20,000 copies. On the cover, there was only one title: ‘Gilles’.

"The Italians call him by his first name as if he were one of them," explains Daniela Renosto, Quebec's delegate in Rome, who has seen people in tears at commemoration ceremonies.

She herself often notices a photo of the driver at the entrance to a restaurant or a store, instead of a frame of the Pope or Sophia Loren. "When I tell the person behind the counter that I'm also a Quebecer, I create a furor," says the woman who has lived in Italy for 20 years.

Which led Joann Villeneuve to say last year that her myth is even stronger in Italy than in Quebec.

Like James Dean

All Italians aged 40 and over will tell you where they were when Villeneuve's Ferrari flipped over at Zolder. Marco Cestari, for example, was working as a cook when a colleague told him the news. "I was unable to continue working. That night, I cried," recalls the 49-year-old, who has two portraits of his hero signed by Joann and Mélanie Villeneuve.

For Jonathan Giacobazzi, son of Gilles Villeneuve's sponsor, his death was a trauma. "I was inconsolable for months," says the most important collector of the pilot's items. "I was only 9 years old and I had been around him every day for three years. After his death, it was like learning to live without salt and pepper."

According to retired photographer Giorgio Proserpio, who played cards with Gilles after his races, the fact that he died at the height of his fame acts as fuel for the collective passion. "He's a bit like the James Dean of Formula 1," says Mr. Proserpio, who covered the Monte Carlo Grand Prix for 40 years.

Have Michael Schumacher's seven titles been forgotten? The German didn't evoke the same emotions as the little speed-crazed Quebecer, say the Ferrari fans. "Gilles did better with much inferior cars," explains Marco Cestari. "But, above all, he was a simple guy who took his family everywhere. Like us."

In the heart of Ferrari

"Among the faces of my loved ones, I see that of a great man: Gilles Villeneuve." Enzo Ferrari did not hide his affection for the Quebec driver. And it is perhaps thanks to him that the Italians also fell in love with him.

By recruiting him when he was still a complete unknown in 1977, the founder of Ferrari was playing for big money. "He wanted to show that with his cars, anyone could become a champion," Paolo Ianeri, columnist for La Gazzetta dello Sport, explained to La Presse.

But Enzo Ferrari quickly realized that Villeneuve had the mettle of Tazio Nuvolari, the Italian racing legend.

In many ways, the old man treated him like his son, not hesitating to put his hand on his arm or even kiss his hair, as at the end of a press conference in 1981.

Things had of course gone a bit wrong before the Zolder tragedy. The ‘little guy from Berthier’ had felt betrayed following the 1982 San Marino Grand Prix, during which his colleague Didier Pironi had overtaken him on the last lap, not respecting his position as second driver.

"For Enzo Ferrari, the most important thing was that a Ferrari won," says Jonathan Giacobazzi, son of Villeneuve's main sponsor.

Despite this bitter finale, Gilles Villeneuve is recognized at Ferrari as the Commendatore's favorite driver.

"A photo of him was next to Enzo Ferrari when he died," reveals the team's spokesman, Renato Bisignani. “Villeneuve will always have a place of honor in our history."

5 reasons F1 fans are still in awe of the legendary Gilles Villeneuve. Greg Stuart, 18 January 2021.

Had things panned out differently, January 18, 2021 would have marked the 71st birthday of Gilles Villeneuve. The French-Canadian driver only competed in six seasons of Formula 1 and won just six times – and yet his extrovert driving style and never-surrender attitude mean he is still sorely missed by F1 fans today.

Lap 4 of the 1981 British Grand Prix at Silverstone and Villeneuve has just clouted the fiddly chicane at Woodcote. Carnage ensues, as Villeneuve spins into the catch fencing and eventual retirement, taking Williams’ Alan Jones and Alfa Romeo’s Andrea de Cesaris – who’d both been unable to avoid the French-Canadian’s rotating Ferrari 126CK – with him. The crash was, to all intents and purposes, Villeneuve’s fault.

Watching on a television set back in Maranello, Enzo Ferrari – the hard-headed doyen of the marque and not a man known for his levity when it came to drivers crashing his precious racing cars – turned to his designer Harvey Postlethwaite and said: “too narrow, this chicane.”

F1 fans still rave about Villeneuve, nearly 40 years after his death.

Such was the leniency and affection that Enzo Ferrari – and F1 fans around the world – afforded to Gilles Villeneuve. It’s nearly 40 years since Villeneuve lost his life on a grey day in Zolder, Belgium. And yet despite his rather meagre statistics – with just two pole positions joining the six wins from his 67 Grand Prix starts – Villeneuve’s name and legend, continues to echo down the years. Why?

Here are five reasons why we’re all still in awe of Gilles Villeneuve...

1. He was one of Enzo Ferrari’s favourites

Avuncular, warm-hearted, tender, empathetic – all words which singularly fail to describe Enzo Ferrari’s habitual relationships with his drivers. It’s said that when he found out Eugenio Castellotti had fatally crashed his Lancia-Ferrari while testing at Modena in 1957, Enzo’s first question had been: “e la macchina?” – “and how’s the car?”

Meanwhile, just a few months after Villeneuve’s fatal crash at Zolder, Didier Pironi’s career-ending smash at Hockenheim is said to have evoked the following response: “addio Mondiale” – “goodbye world championship.”

Villeneuve, however, was one of a very select band of drivers who managed to earn both the respect and the love of the Signor Ferrari. Ferrari had famously been team manager for the great Tazio Nuvolari at Alfa Romeo in the 1930s and saw clear parallels between Villeneuve and The Flying Mantuan – both men who drove with an almost possessed air, as if egged on by something otherworldly that allowed them to transcend the performance of their often inferior machinery.

It's said that Villeneuve reminded Enzo Ferrari of Tazio Nuvolari.

Ferrari’s affection for Villeneuve certainly wasn’t born out of his driver’s deference either, with Harvey Postlethwaite remembering the French-Canadian telling ‘Il Commendatore’: “I’ll drive [the car] all day long, I’ll spin it, I’ll put it in the fence, I’ll do whatever you like. I’ll drive it because that’s my job and I love doing it. I’m just telling you we’re not going to be competitive.” According to Postlethwaite, “the Old Man loved him for it.”

Little wonder, then, that Enzo Ferrari was so cut up when Villeneuve lost his life at Zolder, writing an extraordinary tribute – which put Villeneuve on the same pedestal as his beloved late son Dino: “His death has deprived us of a great champion – one that I loved very much. My past is scarred with grief; parents, brother, son. My life is full of sad memories. I look back and see the faces of my loved ones and among them I see him.”

2. His car control was stunning

While all of today’s crop of F1 drivers learned their craft at the kart track, Gilles Villeneuve learned his racing snowmobiles in Quebec – and it showed. Much like racing speedway on motorbikes, snowmobile racing on ovals requires riders to pitch the front of their machines into the corner and then control the resultant slide on the throttle – and 1974 snowmobile world champion Villeneuve’s technique on the snow was little different to the one he used at the wheel of his Ferraris.

Head-tilted, on opposite lock: the ultimate Gilles Villeneuve pose.

The ‘modus operandi’ of Villeneuve, like that other great artist of the 1970s Ronnie Peterson, was to powerslide through corners with perfect control, using opposite lock to dance the car on the limit of adhesion before gunning it at the exit.

It was the antithesis of the approach preached by three-time world champion Sir Jackie Stewart – and yet even the Scot couldn’t deny his admiration for Villeneuve’s ability: “his car control was extraordinary, even compared with the many talented drivers I’ve had the opportunity to drive against over the years,” said Stewart. “[He drove a] Grand Prix car to the absolute limit of its ability.”

Photo by Richard Spruill.

Photo by Richard Spruill.

That stupendous car control – legendary F1 journo Alan Henry once described Villeneuve as “the last person who had the totally uninhibited joy of driving a racing car” – manifested itself at lower speeds too. At Monaco in 1980, Villeneuve incurred the wrath of his friend Professor Sid Watkins, after the medical car Watkins was riding in was caught up by the pack.

“All the drivers gave us a wide berth, except Gilles, who seemed to use us as his apex,” remembered Professor Watkins. “I started to give him a b******ing afterwards, about how he’d missed us by an inch or so and he simply couldn’t understand what I was talking about.‘That’s the whole point, he said.‘I missed you! And then I realised that, to him, an inch was like a yard to anyone else. He was that precise.”

Villeneuve earned the wrath of Professor Watkins at Monaco in 1980.

3. #27

F1 people can get hung up about the smallest things. There’s a famous Michael Tee photograph of Juan Manuel Fangio powersliding his Maserati 250F through the downhill curves at Rouen. Tee took a near-identical photo of Jean Behra going through the same corner in the same car – and yet the 10 or so degrees of extra slip angle that Fangio is putting through the car is enough to send F1 types into cold sweats.

So it is with the #27 affixed to a red Ferrari – a trope that will always be come back to its association with Gilles Villeneuve. Villeneuve actually only drove with the #27 for 19 Grands Prix. And yet that number on a Ferrari came to signify something magical. Ferrari’s dazzling chargers – Villeneuve, Jean Alesi (whose boyhood hero was Villeneuve), Nigel Mansell – all wore the #27, while the #28 seemed reserved for the team’s more solid, stolid runners – the likes of Didier Pironi and Gerhard Berger.

Villeneuve also drove #40 – in his first F1 outing at the 1977 British Grand Prix with McLaren – as well as #21, #12 and #2 in his career. Indeed, he took four of his six F1 wins with the #12 car. And yet, for reasons that are hard to explain, but equally hard to refute, it’s the #27 that captured fans’ imaginations.

Black and orange helmet, red Ferrari, number 27... lovely. Photo by Speedworks.nl.

4. He was at the heart of some of F1’s most iconic moments

It’s said that Villeneuve’s tenacity was the quality Enzo Ferrari most prized in the French-Canadian and it earned him the respect of his fellow racers too.

When Williams’ Alan Jones easily caught and passed Villeneuve at the 1979 Canadian Grand Prix, the Australian quickly built a lead of nearly three seconds before deciding to slacken his pace – only for Villeneuve to then begin re-attacking Jones. “Jeez,” Jones would later tell journalists, after eventually seeing off Villeneuve and claiming the win. “That guy just won’t give up…”

Villeneuve would fight hard for lesser positions too. His most famous duel was with Renault’s Rene Arnoux for second place at the 1979 French Grand Prix, Villeneuve and Arnoux bashing wheels and slewing all over the track in the race’s closing stages in a fight that still dazzles over 40 years later.

Villeneuve gave no quarter in his legendary fight for P2 with Rene Arnoux at Dijon. Photo by Motorsport Images.

Four races after Dijon, a puncture pitched Villeneuve into a spin and off the track at the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. Unperturbed, Villeneuve backed the car onto the circuit and drove a whole lap on three wheels, one hand raised in the air to warn cars behind him.

A similar stubborn refusal to throw in the towel was witnessed at the 1981 Canadian Grand Prix, when Villeneuve completed a lap with the front wing of his Ferrari practically folded up into his cockpit. He’d eventually finish the race in third.

So, was this foolhardiness, or brilliance? There’s definitely a fine line between the two. But as Jochen Mass once said: “sometimes, like at Zandvoort, he was stupid and ridiculous. But the fans loved the way he raced and that’s just the way he was. Motor racing needs drivers like this.”

Villeneuve's epic 1979 lap on three wheels at the Dutch Grand Prix.

5. His death ensured his mythic status

Without wishing to glorify it, there’s no doubt that the death of an icon while they’re still in their prime – in whatever walk of life – adds a melancholic gilt to their legend. Jimi Hendrix, James Dean, John F. Kennedy, Buddy Holly, Jim Clark, Kurt Cobain, Ayrton Senna – all are figures whose death provides a lens through which we must subsequently look at their lives.

So it is with Gilles Villeneuve. The facts are that in qualifying for the 1982 Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder, Villeneuve had gone out for his final run and come across the slow-moving March of Jochen Mass, who dived to the right to get out of Villeneuve’s way just as Villeneuve committed to the same line.

The resultant crash was enormous, sufficient to launch Villeneuve from the car and into the catch fencing. He was taken to hospital in Leuven but couldn’t survive the fracture to his neck. He died on May 08, aged just 32.

There were certainly factors behind the accident. A limit on the number of super-sticky, one-lap-only qualifying tyres in those days had led to the sessions becoming banzai affairs, forcing drivers to put it all on the line or lose their chance at a top grid slot.

Villeneuve's feud with Pironi began a race before Zolder, at the San Marino Grand Prix.

Then there was the feud with team mate Didier Pironi, ignited at the previous Grand Prix at Imola when Pironi had betrayed Ferrari team orders to win.

Several of Villeneuve’s friends, including Alain Prost and Jackie Stewart, remembered their disquiet at the simmering rage Pironi’s betrayal had set off in the normally easygoing Villeneuve – and which was still very much present when Villeneuve got to Zolder. “I have declared war,” Villeneuve told journalist Nigel Roebuck after the San Marino fiasco. “I’ll do my own thing in future. It’s war, absolutely war.”

Whatever the causes though, Villeneuve’s accident left a void in the sport, while simultaneously ensuring the French-Canadian rightly earned a mythic status among F1 fans – a status which means he’s still remembered with awe today.

August 1979: portrait of Gilles Villeneuve in his Ferrari before a Formula One race. Photo by Allsport UK /Allsport. Formula 1 fans will never forget Gilles Villeneuve.

As the famous motorsport journalist Denis Jenkinson wrote in tribute: “with the death of Gilles Villeneuve, Grand Prix racing will not be the same. It will still go on and one day another star will appear and shine brightly, but until that day something has gone out of racing that will be hard to replace.”

“To us, who had seen him walk away, unmoved, from some monumental prangs caused by tyre failures or mechanical breakages, he seemed to be indestructible. But Jim Clark always seemed indestructible and so did Mike Hailwood. We live in a wonderful world but at times it can be very cruel. Perhaps it is so to ensure that those of us who are left do not get too complacent.”

Happy birthday, Gilles Villeneuve.

Interview exclusive: ‘I was a proper fanboy’ – Jeremy Clarkson on his racing hero Gilles Villeneuve. Senior Editor Greg Stuart. 08 May 2022.

Every F1 fan has their favourite driver growing up. Sir Jackie Stewart was a Juan Manuel Fangio fanatic. Sir Lewis Hamilton revered Ayrton Senna. But for Jeremy Clarkson, star of shows including 'Top Gear', 'The Grand Tour' and, latterly, Amazon Prime’s 'Clarkson’s Farm', there was only ever one F1 driver who was worth a damn: Gilles Villeneuve. Forty years on from the Canadian’s tragic death at Zolder on May 8, 1982, Clarkson opens up to F1.com Senior Editor Greg Stuart about the roots of his deep-seated adulation for one of F1’s most unique drivers.

On paper, it seems strange that Gilles Villeneuve could hold the iconic status of a Fangio or a Senna (or a Stewart or a Hamilton for that matter). The key stats run as follows: pole positions – two. Race wins – six. Podiums – 13. Championships – zero. Hamilton trumped every one of those stats… in 2020 alone.

Yet for Clarkson, stats pale into insignificance compared to the leonine way Villeneuve comported himself on track.

“I think there were two events that cemented him in my adulation really,” Clarkson tells me, taking a break from a morning’s scriptwriting to chat racing heroes. “The first was – well, I know it was the [1981] British Grand Prix because I was there… At Woodcote, there was the most enormous crash. I can't remember who caused it [but] these were the days when they used catch-fencing. And it was complete carnage, cars everywhere, people, marshals.

“But when it all sort of settled down, you could plainly hear that one engine was still running and it was Gilles’. He set off back onto the track with really only half a car and most of the catch fencing wrapped around what was left of it. And I thought, ‘There's a man so determined to win this race, he's prepared to go, “no, no, I'm alright.”’

“He was sort of like the knight in Monty Python with no arms and legs. He's still going to carry on racing, even though he didn't really have a car any more.

“And then of course, there was the '79 French Grand Prix in Dijon. He was racing for second place with Rene Arnoux. How many times did they hit each other on that last lap, five times? They took it in turns to be knocked off and then came charging back on again… It was absolutely fantastic racing and I just thought, 'Okay, he's my favourite racing driver.' I've never really seen anyone race like him since.”

Clarkson admits unashamedly that his fandom extended to having posters of Villeneuve racing his Ferrari (he also drove one race for McLaren on his F1 debut, at the 1977 British Grand Prix) on his wall – while adding that Villeneuve’s famous race number, 27, also holds a special place in his heart.

“It's still my lucky number,” he says. “I still always choose 27 whenever I've got the opportunity – because of Gilles Villeneuve. If I see the number 27 in any context, whether I'm betting on a horse or anything, if it's 27 I will always bet 27 – because of Gilles Villeneuve.

“I definitely had pictures of his racing car on the wall. I bought a Ferrari because of Gilles Villeneuve, the 355. I loved Ferraris because of Gilles Villeneuve… And [the 355] had to be red. And I damn nearly painted 27 on the side of it…”

Villeneuve’s detractors are quick to point to a reckless streak in the French-Canadian. While that Dijon fight with Arnoux has become part of F1 lore today, at the time, many condemned the antics of the two racers as dangerous (Mario Andretti a notable exception, the 1978 champ famously telling the press the pair were “just a couple of young lions clawing each other”).

Arnoux and Villeneuve's famous fight for P2 at the 1979 French Grand Prix entranced a 19-year-old Clarkson.

Elsewhere, stories of landing helicopters in pitch black, driving his Ferrari road car at warp speed on the roads from Maranello to Monaco and iconic instances of Villeneuve racing on track minus wheels, front wings and the like, form an unignorable part of his biography.

Gilles Villeneuve with his toys at Imola in 1981.

So, I ask Clarkson meekly, did he ever feel Villeneuve’s behaviour strayed into foolhardiness?

“Yes of course! I hope so!” he replies defiantly. “That's exactly what I want from a racing driver… When the race finishes, can you imagine someone saying to Gilles Villeneuve 'you managed your tyres very well Gilles.’ He wouldn't know what you were talking about. He doesn't want to manage his tyres very well; he wants to slither about and crash into Rene Arnoux and drive with half a car.”

And what of modern Formula 1? How does Clarkson think Villeneuve’s firebrand style of driving would have suited racing in 2022?

“Well modern Formula 1 has got good now that they've worked out how to be able to drive behind another car!” replies Clarkson. “The first two races [of 2022] were fantastic, weren't they. So he probably would have approved of that, I'm sure.

“But I'm sure he'd be, like me, saying that these cars have got to be stronger – you've got to be able to biff someone and not lose an endplate and then you're five seconds a lap down and you've got no chance of winning. They would drive around problems in those days rather than say 'well that's it, I've got a problem so I can't win so there's no point even trying.' So I think that might be something that he'd find strange – if a tiny little piece of car falls off, then that's it, you're out of the running.”

Villeneuve's anger against his team mate was evident at Imola, one race before his fatal crash.

The circumstances of Villeneuve’s death, during qualifying for the 1982 Belgian Grand Prix, are dark, to say the least. Incandescent with rage following what he saw as a betrayal of a gentleman’s agreement by Ferrari team mate Didier Pironi at the previous race at Imola, a still-simmering Villeneuve – not known for his conservative driving style – launched himself out of the pits aiming for a banzai lap of Zolder.

Approaching the March of Jochen Mass, a tragic piece of incommunicado between the two drivers saw the slow-moving Mass try to jink out of Villeneuve’s way just as Villeneuve darted in the same direction. Doing an estimated 140mph, Villeneuve’s Ferrari hit the back of the March with such violence that he was ripped from the cockpit of the 126C2 and thrown into the catch fencing. A fracture of the neck would ultimately mean there was no saving him.

Did Clarkson remember the details of that day?

“I know where I was,” Clarkson replies quietly, “well, I was watching television. I can remember Gilles dying. Gilles Villeneuve, Keith Moon, I remember all of them. I know where I was when Senna died: I was at a motor show. You remember those things for sure.”

Villeneuve's exuberant style was breathtaking.

There’s a poignant quote from legendary F1 journalist Alan Henry about Gilles Villeneuve, where he calls the French-Canadian “the last person who had the totally uninhibited joy of driving a racing car”. As our conversation nears its end, I put the quote to Clarkson and ask if he shares the view.

“I don't think he was the last,” he replies after a pause. “I think Kimi Raikkonen had a joy – not in the latter stages, but he was joyful. Ferrari always does tend to pick that sort of a driver; he was a perfect Ferrari driver. Nigel Mansell was too – perfect.

“So I don't necessarily think he was the last. But he was my idea of a proper, boy's own hero – like Chuck Yeager or Francis Chichester or [Ernest] Shackleton… I was a proper fanboy.”

Patrick Tambay in 1983. Photo by Getty Images / Mike Powell.

“Gilles is a myth that resists the passage of time.” Patrick Tambay. May 08, 2022 by The Canadian.

He is a man tired by illness who nevertheless agreed to answer our questions.

Patrick Tambay has been battling Parkinson’s disease for years.

If his speech is difficult today, his memory is intact.

“It’s when there are phone calls like yours that memories come flooding back immediately”, replies the 72-year-old man, happy that his friend is remembered.

«Gilles was a handsome madman! A good living. He liked nice cars, friends and especially beautiful women, but I shouldn’t tell you that», laughs the former pilot.

«On the track, he was total. His commitment was total. For his adversaries it was a heavy presence», he adds.

“Gilles was always in the fight, 100% in the fight. He never let go. A little hotheaded even. Besides, he would have had much better results if he had been a little more patient. But Gilles and patience did not mix. He also stated that he knew he was impetuous and abrupt at times. It was his way of being. If he had hesitated to attack a turn hard, he would not have been Gilles Villeneuve.”

After the tragedy at Zolder and the disappearance of his friend Gilles, the Écurie Ferrari offered the French driver the chance to take over Gilles’ car number 27. The memory of his victory in 1983 on the Imola circuit in Italy, a year after the death of his friend, is still very present.

«I remember that at the beginning it was a bit cumbersome to take over Gilles’ car, HIS car», emphasizes the former pilot.

Gilles Villeneuve, Ferrari 126CK, Grand Prix of Monaco, 31 May 1981. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

«At the same time, I thought back to the accident. I thought the first laps were going to be difficult, but I immediately felt his presence», recalls Patrick Tambay. «There has always been this presence, Gilles was there with me. He was also in the crowd, which had unfurled banners asking me to avenge him by winning the race. I feel like he was driving with me.»

“But I can tell you one thing. It was while driving the car that I became aware of Gilles’ immense talent. I have never really been able to match its performance and yet it was the same car. It was Gilles who surpassed himself and who made the car surpass himself as well. I don’t know if you believe in paranormal phenomena, but I assure you that that day, it was not me who drove this car to bring it to victory.»

While still rummaging through his memory box, Patrick Tambay also remembers the friend who introduced him to Quebec.

“Oh yes, he made me discover Quebec», claims the Frenchman as if it were yesterday and he suddenly regained his youthful ardour.

«After the races, we were a small group of pilots and we went with him into the woods. We crossed the maple groves like crazy, to finally arrive in what you call the sugar shacks. Afterwards, we went back to fooling around in the woods», he adds with a smile that says a lot about past journeys.

The friendship between the two men will be so great that the French pilot will become the godfather of his son Jacques.

Before leaving, the septuagenarian apologized for his difficult speech due to illness, but he wanted to answer questions.

”For me, Gilles will remain a legend. Remembering him after 40 years is proof that he still has his place among the greats. Gilles is a myth that resists the passage of time.»

A time that even speed has not yet managed to catch up with.

Rediscovered: Gilles Villeneuve on life and racing — 'Maybe one day I have a big accident.'

By Andrew Marriott, May 8th 2022.

Long-lost footage of Gilles Villeneuve at the end of the 1981 F1 season reveals his fearless, fatalistic thinking seven months before his death.

Lost on the dusty tape racks of Motor Sport’s former assistant editor, Andrew Marriott, was a box that simply said: “TV Villeneuve doc”. For years it sat there, its existence entirely forgotten until a call came from the producers of a new documentary charting the friendship, turned tragic rivalry, of Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi.

In search of material that could be used in the film, Marriott uncovered 20 minutes of footage made for Canadian TV, including an interview with Villeneuve that he couldn’t remember carrying out. As his trusty tape machine replayed Villeneuve’s accented English, it offered new insight into Villeneuve’s view on racing and life, less than a year before his fatal crash at Zolder.

The 1981 season had not gone Gilles Villeneuve’s way. Despite brilliant wins in Spain – where he made the Ferrari very wide — and famously at Monaco, he was no longer in contention for the World Championship by September and the Italian Grand Prix.

But Villeneuve’s reputation wasn’t built on results and, as I said in the introduction to a 20-minute documentary that I made with him at Monza that year, “amongst the top names in racing Gilles has an unparalleled reputation as a man who will never give up even as his machinery falls apart around him.”

Villeneuve with Marriott in the 1981 interview.

Sitting in a couple of camping chairs next to his motor home, without a PR in sight, we discussed racing and life, revealing a driver who loved his racing. A man who was friendly, fearless and fatalistic. As a piece of lost history showing how Gilles was thinking just seven months before he died, it is magic.

My interview was just part of another hectic day for Gilles. The previous Sunday he had been competing in a special powerboat race for Formula 1 drivers, held on Lake Como in Monza which he won in spectacular style. On Monday he was back at home in Monaco. On Tuesday it was back to Italy for testing at Ferrari’s track in Fiorano, as the team continued to work on the troublesome turbocharged 126.

He spent Thursday flying in his helicopter to a business meeting in the Cote d’Azur and then arrived at Monza on Thursday evening where he would be staying – unlike all the other drivers who preferred hotels – in his motorhome by the paddock.

Was racing in his blood? “I guess so,” said Villeneuve. “I just like it for the sake of the racing, not for the money in it although I like it for that also. I still like racing even if I am in say 18th or 15th place but I think some other drivers don’t give everything when they are at the back of the pack. You have to like racing, it is not something you can do well if you don’t do it with your own heart. But I think everyone who is Formula 1 now likes it.

“At the beginning it just happened that it was possible that I could go snowmobile racing. Car racing was my first love but I could not afford it. The opportunity was there to go racing snowmobile and I won a few races and the ball started rolling and I got a little name with that. So I made some prize money with that so I could afford to buy a Formula Ford then on and on.”

Villeneuve scored a rare 1981 win in Jarama, against the odds.

From his Formula 1 race, in an outdated McLaren at Silverstone in 1977, Villeneuve had been hailed as a future world champion, but the 1981 title wasn’t to be. After those couple of early wins, the Ferrari was unreliable and barely competitive. “Of course you prefer when the car is competitive and you can battle it up front and even if you don’t win, if you have finished second or third you know you have had a good race,” said Villeneuve.

“But that hasn’t been the case after Spain. Actually in Spain the car wasn’t that fast. Due to a series of circumstances I was leading and I was able to keep it like that. I think it was one of my best races – it was very tough to do. But then I guess the car fell back to where it belonged; in Spain the car should have finished sixth or seventh. I am not saying I made it finish first but I had the opportunity of leading and then not fade off. Since then it has been very tough but here it has been improving quite a bit, we have done good testing two weeks ago working on the springs, dampers, bump rubbers and skirts and the car is a lot more drivable than it has been for a long time.”

I then turned to the dangers of racing, and remember I was talking to a man who was considered to have a devil-may-care attitude although he was on the GPDA (driver) Safety Committee. “We work very hard at improving the circuits and I can tell that the grand prix circuits are the safest in the world and the lesser tracks are a lot less safe than the ones we race on because we have improved those with catch fences, that kind of thing. Yes the tracks can always be made safer but it is not too bad now. Also the cars are being made safer, more strong and everything. From a personal point of view, I don’t think much of that although, of course, I don’t want to kill myself, but I guess it is part of the job and we accept it the way it is.

“I know that maybe I can have an accident tomorrow and hurt myself and maybe have to be in hospital for a couple of months but you can always come back from that, so that’s the way I see it. There are maybe a couple of times a year I can have a big accident but, of course, I don’t want to have one but maybe one day I have one.”

Villeneuve on his way to victory in the 1981 Monaco GP. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images.

After this staggeringly honest answer our conversation turned to his rivals and I asked if he had anyone he treated as a friend “yes, I do have close friends, mainly the French drivers, I don’t know why. They are not special people above the other nationalities but it just happened like that. I would say Patrick Tambay, Rene Arnoux, Alain Prost and Pironi my team-mate [whose first name wasn’t mentioned]. We are good friends but on the track we are just rivals.”

The interview had begun by my asking him how his lifestyle had changed since joining Formula 1. “Here in Monza it is very different from Canada but living in Monaco is, I guess, the closest town to what you can find in North America,” said Villeneuve in his accented English. As a Quebecois his first language was French and a couple of times he said he was out of practice speaking in English. “Life has changed a bit but we try to make it as close to how we lived in Canada. I first found it a bit tough when I moved to Europe as I think I am a typical Canadian or American, I found it very tough at first because some parts of living in Europe are very, very different. But now, after four years, we are completely used to it and I like it.

Villeneuve leased his helicopter from Walter Wolf. Photo by Grand Prix Photo.

I asked about the financial rewards racing in F1 had brought him and what he did with his money “well, some people put it in the bank to have more, but I don’t put much in the bank, I just spend it (laughs) but the helicopter that I am flying is not mine, it belongs to Walter Wolf and I lease it off him – but always the things I get, I get them quite cheaply – so I get a good deal on it. A few months ago I bought an offshore powerboat but I did a kind of deal with the guy from Italy to do PR for him so that was a special price so although I spend a bit I always try to get a good deal. I don’t really spend much on clothes or even cars. But if I feel I want to buy something, if I can afford it, I buy it, which is pretty much like any Canadian, I guess.”

I knew Gilles had started a car collection, “it is not really one, I want to build a collection of some American cars and I have always been fond of Ford products back in Canada so perhaps I will create a collection on that make. Of course I have a Ferrari for the road but I don’t see any point in collecting them, it would be just be too expensive.

Villeneuve’s path to Formula 1 was brokered by James Hunt, who also contributed to the programme and was as eloquent as ever. He said: “some people say I discovered Gilles but I didn’t really, you didn’t have to be much of a brain surgeon to spot his talents when he was driving Formula Atlantic in Canada. I went over there and raced against him at Trois Rivieres and got thrashed. But for those in Europe he was already well known because he was cleaning everything up in Atlantic. The only thing I responsible for was getting him the McLaren drive. Even before I went to Canada, I said to them he was someone to watch. Then they signed him and unfortunately let him go and Ferrari got him.”

Asked about his strong qualities, Hunt replied: “well, it is probably easier to look for his weaknesses which aren’t very many now. The year he could have won the championship – 1979 – when Ferrari had a good car and all that reliability, he rather threw it away. He made a lot of mistakes that year always from easy — from winning — situations.

“Unfortunately since that time he hasn’t been put to the test because he hasn’t been in that situation because he hasn’t had a good enough car. So that was his weakness, he is a terrific competitor, he has an abundance of natural talent that is second to nobody in the business and he is a thinker off the track. His weakness is that he didn’t think well on the track at that time.

“I think by now if you put him in a winning car, he wouldn’t be making those old mistakes. Now he is much more experienced but you would still have to test it to see – it is up to Ferrari to provide him with the car. His two wins in Spain and Monte Carlo were both a fantastic effort of qualifying a bad car well by sheer blood and thunder and then wrestling it around the track and not making any mistakes. The Spanish GP was absolutely brilliant because the car deserved to be about tenth.”

Andrew Marriott’s 1981 interview will form part of the upcoming ‘Villeneuve Pironi’ documentary. The feature film from Noah Media and Sky Studios contrasts the intertwined lives of Ferrari friends then foes Villeneuve and Pironi with the aid of their family, Ferrari team members and rivals.

The untold Gilles Villeneuve story from inside Ferrari

On the 40th anniversary of Gilles Villeneuve's death, Formula 1 remembers a legend of its history. In a freshly uncovered interview from 1996, Ferrari chief designer Harvey Postlethwaite provides insight into Villeneuve, his relationship with teammate Didier Pironi and his impact at Ferrari.

Adam Cooper, May 08, 2022. Updated May 11, 2022.

Forty years ago today, Gilles Villeneuve lost his life after colliding with Jochen Mass during qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder. Photo by Ercole Colombo.

The story of his Ferrari team’s tumultuous 1982 Formula 1 season, which also included career-ending injuries for Villeneuve’s teammate Didier Pironi, has been told many times.

However, one voice rarely quoted is that of the Maranello team’s chief designer Harvey Postlethwaite, whose 126C2 won the constructors’ championship that year – and should have won the drivers’ title.

In 1996, three years before he died, Postlethwaite told this writer about that season and the complex relationship between Villeneuve and Pironi. The interview wasn’t used at the time and for the past 26 years it’s been lost in a box of old micro cassettes.

Much like his contemporary Patrick Head, Postlethwaite was a no-nonsense racer, not given to sentimental reflection. However, it was clear that he had fond memories of Villeneuve among the many drivers he had worked with over the years.

“Gilles had this image of being completely mad,” he said. “Well mad is probably the wrong word, but of being very fast and being I suppose irresponsible, almost, in a racing car. In fact, it wasn't quite like that.

“He was a very serious driver, he took his driving very seriously. But he did like to take everything very much to the limit. And he liked every lap he drove to be as quick, or quicker, than the last lap he drove.

“Now, that was a way I suppose he probably had of pushing himself to the limit. But he was certainly rather brighter and rather less of a madman than people have made out. I mean, the image has probably grown with the passing time, but actually, I always found him very serious and really quite a bright guy.

“He was by no means a politician and he spoke very clearly and simply about the car. And I think he was greatly appreciated for that. But he was bloody quick. I mean, there's no doubt about that. He was probably one of the fastest racing drivers there's ever been.”

Enzo Ferrari with Gilles Villeneuve, considered to be one of his favourite drivers for his team, during the unveiling of Ferrari's new 312 T3 car, Maranello, Modena, Italy, 12 November 1977. Photo by Edoardo Fornaciari / Getty Images.

Postlethwaite confirmed that Enzo Ferrari had a soft spot for Villeneuve, who first raced for him at the end of 1977.

“Ferrari the racing team then was much, much less political than it is now,” reckoned Postlethwaite. “Still, there was a certain amount of not stepping on people's toes. And Gilles didn't mind whose toes he stepped on! If he thought the car was no good, he said that and that tended to upset a number of people, but he didn't mind doing that.

“And the Old Man loved him very much for it, because he thought that was exactly what he wanted to hear. He wanted to know.

“They barely had a language in common – they had some French in common. But I don't think anyone was ever really close to Enzo Ferrari. Certainly, he had a great affection for Gilles without any doubt, because Gilles did what few other people could do. He could do what Michael Schumacher is doing today, he could take a car which is probably not the best and he could make it go as quick as anybody else.

“Pironi was a different sort of guy,” Postlethwaite recalled. “I knew him less well, I didn't know him at all until I went to work for Ferrari. He wasn't such an open sort of person, so rather more difficult to get to know. But he was also pretty quick.”

Postlethwaite gave an interesting insight into the styles of the two drivers: “Gilles was quick everywhere. But particularly - and it sounds almost silly, but it's quite true - Gilles was amazing on slow corners. On twisty corners he was unbelievably quick.”

“And Pironi was quick at fast circuits. He was a very, very amazingly brave driver in fast corners. He never lifted. And in a funny way, they complemented each other.”

Villeneuve and Pironi were firm friends – until the infamous 1982 San Marino GP, a race boycotted by most of the British teams.

After the Renault challenge faded, they traded the lead several times. The Canadian believed they were putting on a show for the fans and that Pironi would comply with a pre-race agreement and let him win. It was also a tight race on fuel consumption and both drivers had to be mindful of that.

Postlethwaite felt the feud between Pironi and Villeneuve was made out to be bigger than it was. Photo by Motorsport Images.

On the last lap Pironi blasted past and took the flag, leaving Villeneuve with no time to respond. After the race he was adamant that he had been robbed and swore that he would not talk to his teammate again.

Although Villeneuve’s feelings were well known, Postlethwaite downplayed the impact in the camp. “I think the animosity that was supposed to have been between them was blown up out of proportion,” he insisted.

“There may have been a moment's animosity over the business of what happened at Imola. But even that was blown out of all proportion. Certainly, within the team, it wasn't perceived as anything particularly problematic at the time."

So had Pironi established himself in a strong enough position to get away without censure from the management?

“I didn't think his position was any stronger than Gilles' was,” said Postlethwaite. “I think rather the opposite, I would say. Don't try and simplify the internal politics of Ferrari to a thing like that, there was much more going on than that. And the Old Man was pretty much up to date with everything that was happening.”

“He had them in and gave them both a talking to. He was talking to the drivers all the time. They spent a lot of time at Maranello, the drivers, they had to be there. When the testing was on he liked to watch and he talked to the drivers all the time. I think he was very much in control of the situation.”

Villeneuve stuck to his vow not to talk to Pironi in the days after Imola and he was still fuming when he got to the next race in Zolder.

The accepted wisdom is that he was so fired up by what had happened a fortnight earlier and so keen to outpace his teammate, that the qualifying accident that claimed his life was a direct result of their feud.

Postlethwaite never believed the Imola fallout between the two Ferrari drivers contributed towards what happened at Zolder and Villeneuve's death. Photo by Rainer W. Schlegelmilch / Motorsport Images.

Postlethwaite, who was back in Maranello that weekend and thus arguably a step removed from the tension in the camp, downplayed any connection: “Gilles was always desperate to qualify ahead.”

“Gilles had a will to win which was just incredible. He would overtake anybody in anything, all the time. He didn't care. I mean, that was the way he was, he just wouldn't let people get in his way.”

“Personally, I do not think that what happened at Imola in any way contributed to what happened subsequently in Zolder. I never have believed that. It's a good story, but I don't think it had anything to do with it.”

“Gilles wanted to be the quickest all the time and if that meant overtaking people… You should see the things he got up to on the bloody road. If a car was in front of him, it was to be overtaken. It wasn't that he was sort of particularly aggressive. It was just that was the way he was, if he saw a car in front, he would overtake it. That was it. He just knew he was the quickest driver.”

After Zolder the team carried on, with Patrick Tambay stepping in and later scoring an emotional win in Germany. Pironi won in Holland and logged a string of podiums in a year when no driver or team dominated. Heading to Hockenheim in August with five rounds to go, he led the world championship by nine points.

In a wet session on Saturday morning the Frenchman was fastest when he ran into the back of Alain Prost’s Renault and his car took off. The crash was uncannily similar to Villeneuve’s, but he survived, albeit with badly broken legs. It was the end of his racing career.

“What can you do?,” said Postlethwaite. “That's motor racing, isn't it? And these sorts of things happen. The velocity of Villeneuve's accident was incredible and the severity of the other accident was incredible. The car went up in the air, God knows how fast.”

"They were two very, very severe accidents and to have them both happen in one year was an awful tragedy. And I think it was something that had a very big effect on everybody.”

“It's difficult now to remember your emotions at the time. Funnily enough, I remember the day of the Pironi accident more than the day of the Villeneuve accident, because the Pironi accident seemed so silly.”

Including Hockenheim, Pironi missed the last five races of the season – and he was still classified second in the standings, five points behind Keke Rosberg. The constructors’ title provided some consolation for Ferrari.

After injury ended his F1 career, Pironi moved into powerboat racing but died in an accident in 1987. Photo by Motorsport Images.

In 1986 Pironi did some testing with AGS and Ligier, but an F1 comeback was never on the cards. Instead, he forged a new career in offshore powerboat racing. In August 1987, just over five years after the Hockenheim crash, he was killed in an accident off the Isle of Wight.

Postlethwaite remained adamant that Villeneuve would have won in 1982 and could have gone on to achieve much more.

“Gilles would have been world champion that year I think, without any doubt,” he said. “The car was good enough, the engine was good enough and Ferrari was good enough to get him onto the podium often enough for him to have won the world championship.”

“Personally, I've always liked drivers who were quick and he was quick. It's always nice to deal with a driver like that. Gilles was a star in a period before telemetry. It's different now, it's all very much more scientific.”

“Whether somebody like him will be capable of winning those races today, I don't know, but certainly in that period he was able to win races. When you look at the bloody races with that turbo car in 1981, Monaco and Spain, it’s unbelievable what he did with that car.”

“It's really difficult to know what he would have gone on to do. We can speculate, but I'd like to believe that he would have won several world championships and that he would have been a wonderful ambassador for the sport.”

“I think the sport needs world champions with character and he was a wonderful character, a colourful character, he was a personaggio, as they say. The fans, particularly in Italy, will always love a driver who is quick. He could do things with racing cars which other drivers couldn't do.”

“He had a helicopter and he'd try and make it loop. That was the kind of guy he was. And I think people just appreciated that, certainly then. One of the sad things is probably the whole world is now much more anaesthetised to these things and perhaps that isn't quite kosher these days."

Postlethwaite was convinced Villeneuve had been destined to be F1 world champion in 1982. Photo by Motorsport Images.

There would be more race wins before Postlethwaite left Maranello in 1987, but the 1982 car remains the one that his tenure at the team is best remembered for.

“I have my own memories and my own experiences of the situation,” he said. “And I suppose it's not something one likes to go back over, because when a driver gets hurt in a car, you don't really want to go back over it.”

“There were positive things and negative things that came out of it. But I personally I don't like to see that whole thing hyped up. And I think it was hyped up.”

“There is some truth in the various rumours about what happened and the animosity that there was between the drivers, but it was blown up out of all proportion. And I think actually I'd far prefer to remember those two drivers as good friends and they were actually, off the track quite good friends, I remember.”

“They shared a language and they shared a lot of other things. I think that they were both excellent drivers and they were both very, very competitive. It was a great tragedy that both of them got killed in accidents.”

Postlethwaite remembered both Pironi and Villeneuve as great rivals and team-mates. Photo by: Ercole Colombo.

Didier Pironi and Gilles Villeneuve.

Villeneuve vs Pironi: the tragic rivalry. Much is made of the Lewis and Max rivalry, but in Formula 1 little compares to the enmity between 1982 Ferrari team-mates Gilles and Didier. Maurice Hamilton and Nigel Roebuck look back at the treachery and tragic events that unfolded. By Motorsport in June 2022.

1982 San Marino Grand Prix with Pironi, n.28, leading.

Forty years. Who knows where the time goes? In the midst of one of Grand Prix racing’s most unpredictable seasons, a friendship pivoted in one controversial afternoon into a deadly rivalry between two of Formula 1’s fastest-ever drivers and, in a matter of weeks, ended all too abruptly in a pall of tragedy for both.

Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi couldn’t have been more different as men, yet as fire and ice team-mates at a turbulent Ferrari they still formed a firm bond based on mutual respect and trust, until one betrayed the other in an act of on-track treachery that triggered a devastating spiral. Alain Prost vs Ayrton Senna, Michael Schumacher vs Mika Häkkinen, Lewis Hamilton vs Max Verstappen… all keynote F1 rivalries. But none is more troubling than Villeneuve vs Pironi, the duel that descended so rapidly into a bitterly intense yet all too brief cold war.

Today, F1 people should know better than to add firewood when rivalries smoulder. They should remember Villeneuve vs Pironi, the high stakes in play and what can be lost when it all becomes too personal. The trouble is, with each passing year there are fewer people in the paddock who stretch back that far, who can remember, who truly understand that F1 now, as it most certainly was then, can still be a matter of life or death.

So we’ve turned to Nigel Roebuck and Maurice Hamilton, old friends and distinguished voices, who remember those days all too clearly – because they were there through it all. They knew and dealt regularly with Villeneuve and Pironi, as highly regarded journalists telling the tale from the coalface, Nigel experiencing a level of genuine friendship with Gilles that a latter-day F1 reporter simply can’t imagine forging with the stars of today. Forty years on, ‘Motor Sport’ invited Nigel and Maurice to the cosy Greets Inn in Warnham, West Sussex, to time-warp back to a rivalry that would change F1 forever. It remains an astonishing tale.

Gilles Villeneuve made his F1 debut at the British Grand Prix in 1977 driving for McLaren. He finished 11th but should have been placed higher.

Interview by Damien Smith

“When did you become aware of Gilles?”

Nigel Roebuck: “I was aware of Gilles long before I saw him because of the weekly conversations I had with Gordon Kirby, Autosport’s American correspondent. He kept raving on about this kid in Formula Atlantic, how he couldn’t believe how quick he was, that he was something special. Then I became very aware of him because of something James Hunt said after he went over and did a Formula Atlantic race at Trois-Rivières in September 1976. There were several F1 drivers in that race and they were paid quite a lot of start money – and Gilles blew them all away. James came back and said to McLaren, ‘I’m telling you, you need to sign this guy. He is special.’ That led, of course, to the one-off drive at the British GP in 1977, when Gilles drove a third McLaren alongside James and Jochen Mass.”

"It was a landmark debut. What are your memories of Gilles at Silverstone ’77?"

NR: “I went up to Silverstone on the Wednesday, which was a test day and not for the normal stars, but for the backmarkers and newcomers. And that was the day nobody knows how many times he spun, but didn’t hit anything. It was his first day in an F1 car and the first time he’d seen Silverstone. He had a very short time to find the limit and that was Gilles’ way: to go over it and slightly come back from it. He drove a great race [Villeneuve ran as high as seventh in the early stages], then had a completely unnecessary pitstop because he thought he had an oil pressure problem.”

Maurice Hamilton: “yes, the gauge was faulty.”

NR: “that’s right. But even so it was a strong debut and made a big impression.”

Nigel Roebuck, who was at Silverstone for Gilles’ first F1 drive.

“Maurice, do you remember that day?”

MH: “very well. Like Nigel, I’d read the reports, then noted James’s quotes. That 1977 season was my first as a freelance professional writer and one of my first jobs was to ghost the James Hunt magazine. During the course of that James was talking in the Texaco truck about this guy Villeneuve and kept going on about him. So, when we got to Silverstone, I thought I’ve got to see who this guy is, so I was up there on the Wednesday too. He was spinning like a top! But there was something about him… it was like watching Jochen Rindt, so sideways and not afraid of the car at all. Just powering through Maggotts and Becketts, tail out, finding the limit. It was very exciting.”

“Do you remember first meeting him?”

NR: “it was at one of the end-of-season races that year. I didn’t go to Canada, but I did go to Watkins Glen and Gilles was there but wasn’t driving. He made his Ferrari debut at Mosport the following weekend. It was almost certainly Gordon Kirby who introduced us. It was bitterly cold and I just remember this tiny little bloke wearing this huge chequered lumberjack-style jacket and he was very friendly. We just hit it off. He had time on his hands, so we chatted for about half an hour and it was the start of what was always a really good relationship. He was just so excited to be coming into F1 and with Ferrari.”

MH: “the first time I spoke to him was the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch in 1979, when he won it in a 1978 Ferrari 312T3. I thought, ‘I’ve really got to get an interview with this guy’ and this was a good place to do it, without the pressure of a Grand Prix. I found him at the back of the pits sitting in a Fiat 128 with his wife Joann. In those days tape recorders were a big lump of a thing. I felt a bit awkward and tapped on the window, which he wound down and I asked, ‘do you mind if we do an interview?’ He said, ‘we can do it now, if you like.’ I looked across at Joann, who nodded, so we did our interview with him sitting in the car and me leaning with my tape recorder balancing on the window. I was terribly embarrassed to start with because of the situation, but he wasn’t and neither was Joann. It was brilliant, a lovely interview. The thing that struck me most, because he had a reputation for incidents, was how he shrugged it off: if you race Skidoos you hurt yourself all the time. And it was normal.”