Gilles Villeneuve, between candor and determination. Radio-Canada. Posted on July 10, 2020.

Gilles Villeneuve became legendary following his tragic death on May 08, 1982 at the Zolder circuit in Belgium. Photo: Radio-Canada.

Even though he never became world champion due to the tragic accident that claimed his life in 1982, Formula 1 driver Gilles Villeneuve has gone down in legend and in the hearts of Quebecers forever. Through great interviews and portraits taken from our archives, you can discover this lover of speed with a personality that is at once candid, funny and determined.

From snowmobiling to Formula Atlantic

There are times when it is very difficult and these are the times when you really shouldn't let it go.

Gilles Villeneuve is the first driver from Quebec to reach Formula 1.

Born in a small town where Formula 1 goes unnoticed, Gilles Villeneuve has nothing to make it to the great circus of F1, apart from his immense talent. With a little luck and a lot of determination, he will climb the ranks, stand out and be hired by the most prestigious of teams: Ferrari.

His spectacular driving, his daring and his memorable overtakings will make him one of the most appreciated drivers of the great family of F1.

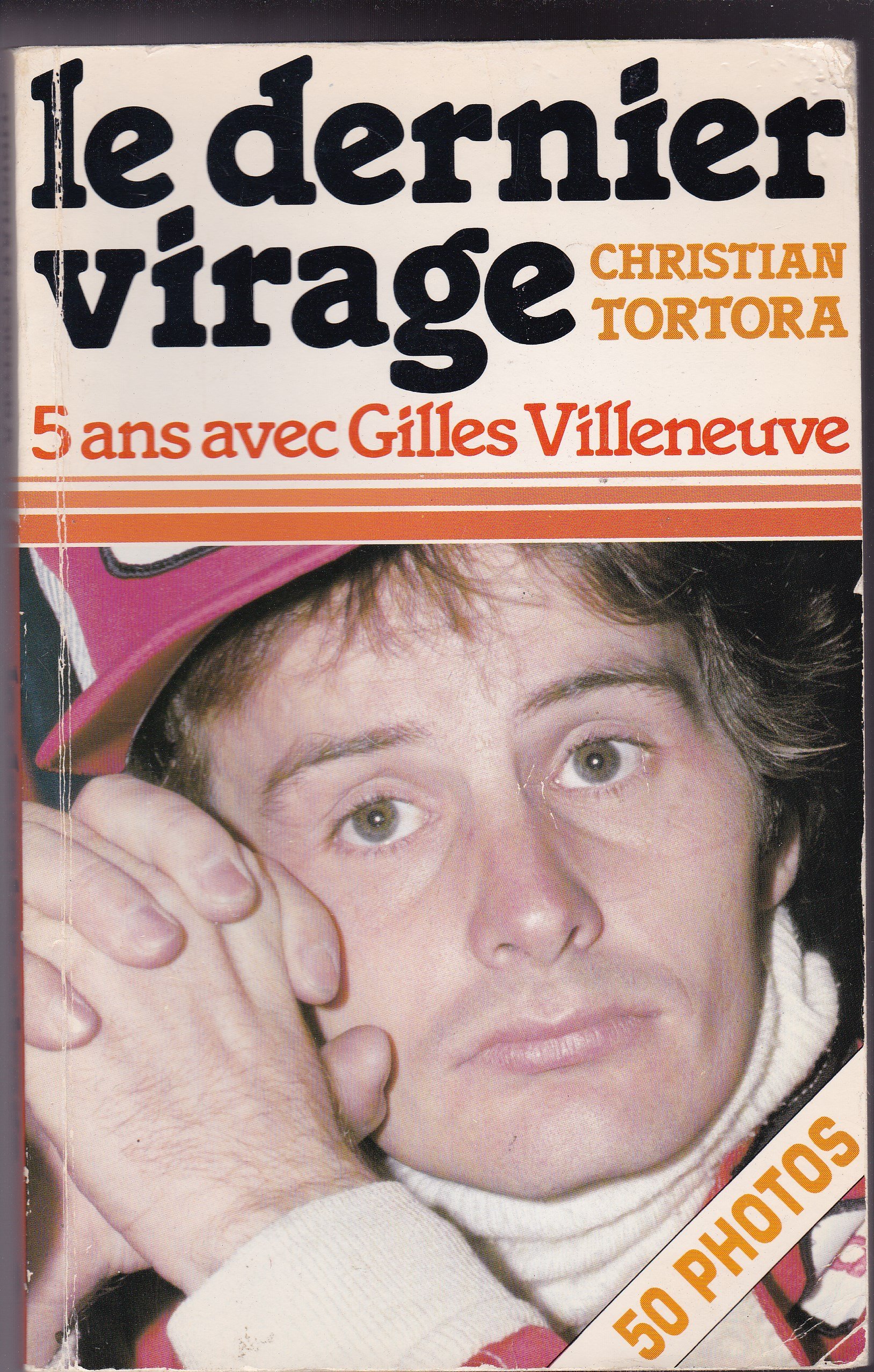

This portrait, released a year after his death, simply titled “Gilles Villeneuve”, traces his career and his most memorable races.

Gilles Villeneuve, June 07, 1983.

Gilles Villeneuve was born in Chambly on January 18, 1950. His family moved to Berthierville when he was only eight years old.

In addition to instilling in them a sense of perfection and of a job well done, his father Seville passed on to his two sons a taste for speed.

“My dad loved speed. He's had his fair share of fines. I always told him "faster, pass this gentleman!"

The driver tells Jean Pagé about himself in the program “Hors-jeu” in 1978. An interview carried out shortly before Gilles Villeneuve joined the Ferrari team.

The pilot from Berthier married at the age of 19 with Joann Barthe, with whom he had two children, Jacques and Mélanie. To support his family, he started snowmobile races in 1969, a field in which he excelled and accumulated titles.

Gilles Villeneuve is also passionate about mechanics. As he explains to Jean Pagé, he designs from A to Z a modified snowmobile where the pilot is in the front and where the engine is installed at the rear of the vehicle equipped with two smaller track-layings than the ones of a traditional snowmobile.

The snowmobile will be for him a springboard towards car racing.

In 1974, after success in Formula Ford, he signs a contract for Formula Atlantic. He must find $ 20,000 to start the season. Determined but broke, he decides to sell his mobile home so that he can race.

His strength of character and his innate driving skills quickly lift him to the top of Formula Atlantic, so much so that in 1976 he obtains nine wins in ten races.

During this interview with journalist Jean Pagé, it was said that it is also a question of mental preparation before the race. Gilles Villeneuve admits to continually thinking about his career. Precision is essential and drivers are not allowed to make mistakes.

It’s so precise, if the braking point is 300 feet before the curve it’s not 298 feet, it’s 300 feet.

At the Trois-Rivières Grand Prix in 1976, he achieved the feat of dominating the race in front of seasoned drivers. One of them, the Briton James Hunt, would notice and recommend him to his employer, McLaren.

On July 16, 1977, at Silverstone, at the British Grand Prix, Villeneuve reveals his immense talent to the world. Driving a one-year-old McLaren M23, he finishes in ninth place in qualifying, ahead of the team's number two driver, German Jochen Mass.

Impressed by the enthusiasm and talent of the young driver, Enzo Ferrari invites him to join his team.

Welcome to Ferrari.

In this reportage from the program “Telemag” of October 25, 1977, the journalist François Perreault speaks with the driver who has just joined the Ferrari team.

Telemag, October 25, 1977.

He begins the 1978 season with Carlos Reutemann as his team mate. A difficult season for the driver from Berthier.

In the first race of the season, in Argentina, he secures an interesting eighth place, despite a bad tire choice. Accidents with Ronnie Peterson in Brazil and Clay Regazzoni in Long Beach, USA, while he leads halfway through, force him to retire. In Monaco, he hits a wall after losing control due to a mechanical breakdown.

Quietly, he is taken by doubts, both in Quebec and in Italy. The Italian press will not be kind to him.

He scores his first championship points in Zolder, Belgium, when he is the only one to stand up to Mario Andretti. He finishes the race in fourth place despite a lap in slow motion and a puncture.

From that moment the tide turns for him. Villeneuve, who has only completed two of the first seven Grands Prix, finishes nine of the last eleven races of the season.

He concludes his season with panache with a victory at the Canadian Grand Prix in Montreal on October 8, 1978.

The victory is welcome for Villeneuve, who had had a difficult season, with several damaged cars and mechanical problems.

The victories will continue to accumulate in 1979. That year, the driver climbs on the podiums of the Grands Prix of South Africa, Long Beach and Watkins.

In 1981, further wins are added to the palmarès of Gilles Villeneuve in Monaco and Jarama in Spain.

Téléjournal, October 6, 1978.

On the Téléjournal of October 6, 1978, Gilles Villeneuve answers questions from journalist Marie-Hélène Poirier.

He talks about his family, adapting to European life, his career as a driver in F1 and the dangers of his profession.

At the end of the 1977 season, Gilles Villeneuve and his family have to leave the village of Berthierville to settle not far from the Ferrari factories.

Villeneuve earns enough money to buy a beautiful villa not far from Cannes, in the south of France, but the family continues to live in a large motorhome. Gilles Villeneuve brings his family wherever he races. He says that he misses American food, that despite the 100 km speed limit on our highways, he prefers to live in Quebec.

He tells about the advantages of living on the circuit.

For the other drivers it is different, they often have a maid at home who takes care of their children, for us it is absolutely not conceivable.

The race of April 25, 1982 in Imola will be his last.

Always the favorite of the crowd, Gilles grabs the first place after the abandonment of the two Renault. But his teammate, Didier Pironi, doesn’t respect the instruction to let the number one driver win and steals the victory. Villeneuve feels betrayed, he who has always respected this tradition when he was the second driver of the Scuderia.

Ferrari is bathed in a terrible atmosphere of unease. Gilles is in conflict with members of Ferrari and is considering leaving the team. It is therefore with a lot of bitterness and anger that he shows up at Zolder.

On the first day of testing, Villeneuve finishes fifth ahead of Pironi. The second day of testing will be fatal.

Téléjournal, 08 May 1982.

On May 8, 1982 on Téléjournal, the host Louise Arcand announces the tragic death of the driver from Quebec with these words: “a death which puts an abrupt end to a brilliant career crowned by solid international fame.”

The journalist Paul-André Comeau recounts the accident in his reportage of Louvain, Belgium.

During the last classification test in anticipation of the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder, Villeneuve's Ferrari splits in two on the circuit after a collision with the car of the driver Jochen Mass. The body of Berthier's pilot is thrown with incredible violence and falls against the fence.

If the accident takes place at 1:52 p.m., the death is not confirmed until 9:12 p.m. The medical records of the Saint-Raphaël University hospital in Louvain show that the impact was so powerful that it nearly beheaded him. Villeneuve suffered several fractures of his cervical vertebrae and his spinal cord was severed. It is his wife, Joann, who accepts that the devices keeping him artificially alive are disconnected.

Gilles Villeneuve's remains are repatriated to Berthierville the next day. To this end, a Boeing 707 was dispatched by the Canadian military. Villeneuve's body is on display at the Berthierville cultural center. Nearly 5,000 admirers come to pay him a last tribute.

The funeral occurs on Wednesday, May 12, at the Sainte-Geneviève-de-Berthier church. The funeral is worthy of that of a head of state. Personalities, such as Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Cardinal Léger and René Lévesque, came to show their affection.

Gilles Villeneuve was a real hero in Italy too. In Maranello, where the Ferrari factory is located, a bronze statue is erected in his honor. The road which connects Fiorano to Maranello is called today the avenue Gilles-Villeneuve.

I just cried and cried and cried. Mr. Mehes Karoly.

Derek Warwick, currently president of the British Racing Drivers' Club, was a young fellow driver of Gilles Villeneuve in 1981/82. He was the first to arrive on the scene of Gilles accident in Zolder. Also he was the first to try to help him.

Before you entered Formula 1 in 1981 you watched the races on TV. How did you see Villeneuve and what he gave to the fans on the track?

“He was somebody who had such imagination, such style, such great determination at all costs. He was idolized for his passion. He was loved by so many people and he made a big impression on a lot of drivers of his era.”

Was he a hero figure to you?

“If you ask this question when I started Formula 1, I would say he probably was a kind of hero because he was somebody you looked up to. If you asked this question today then I may have changed my mind slightly. I think some of the things he did were outrageously dangerous. In hindsight I’d have to say he pushed the boundaries of safety too far sometimes.”

In Imola 1981 you had your Formula 1 debut with Toleman. Gilles was on pole and also led the race. How do you remember this weekend?

“I don’t remember much of the race because we didn’t qualify and we went home early. For us it was a non-event. It was our first Grand Prix though and very special for us. I do remember watching the Ferrari and Gilles preparing for the race and wishing I could be like him one day. I also remember clearly when he arrived on Thursday in his helicopter. He did things with it most people would not imagine doing. He almost looped the helicopter. I thought this man may be a little bit crazy and bit of a daredevil. I thought if he wasn’t more careful, one day he would hurt himself very seriously.”

Did you have any personal contact with him once you had arrived in Formula 1?

“I had little contact with him other than in South Africa in 1982 when we had the drivers’ strike. What surprised me I was a nobody, a new boy to F1, my car was not competitive so I was not competition for him, but I remember him sitting down with me on the mattress in the middle of the floor where we were striking. He was talking to me like I was just like another racing driver. What sticks with me is his humanity. He was a very human person. He never thought of himself as a superstar. He just came across as a nice, humble person.”

At Imola in 1982 the race had only 14 due to some of the teams boycotting the event. What memories do you have of that event?

“I just remember the controversy over Pironi’s win. You have to believe Gilles thought that there was an agreement between him and Didier. If anybody knew Gilles they would know he was a very honest man and he felt very hurt by what happened. Of course most people blamed Pironi for what followed later in Belgium. Gilles was so upset with the way Pironi apparently reneged on their deal. Since then one can read so many things about this incident and it’s not as simple as everybody thinks. There are also people who say Pironi had every right to win the race but Villeneuve for sure never thought that way.”

As a race steward of the FIA, you sometimes have to deal with team orders. Was it different in the 1980s?

“I think there were always agreements within the teams between drivers. The most important was you can race but don’t take each other out and end the team’s race. There are certain times when you are asked as a driver to hold position. That was in the 1980s, in the 1990s and also today. In Bahrain this year the duel between Hamilton and Rosberg was too dangerous. It showed a sign of stupidity because if both drivers were out of the race it might look good for the television audience, but at the end of the day you have to show more responsibility to the team and the sponsors. Mercedes was very lucky.”

In Zolder when Gilles had his accident you were the first car on the scene. What did you find?

“I remember coming through the chicane and seeing the mess. There was a car severely damaged in the middle of the track in front of me. I stopped my car on the side and ran to the Ferrari to help Gilles. It looked really quite horrific, but I found out he was not with the car. That surprised and frightened me. I turned around and saw Gilles crumpled in the catch fencing, his helmet was off. I crossed the road to the catch fence and I tried my best to get him out of the fencing before the medics arrived. For me… he looked dead. I mean, he was blue and he wasn’t breathing. Then the medics arrived I just let them through. I remember walking back to my car and getting in and driving back to the paddock. I then went into our team motorhome and just cried and cried and cried. I knew that Gilles wouldn’t make it.”

How did this effected your career?

“That was the first time I had held another driver in my arms after a bad accident. It had a very strange effect on me. There were many times you lose a fellow driver, but normally it is not that close to you physically. This was different. I was right there with him. During my career I have lost some 13 drivers in different formulas, including my little brother. I can’t say we get used to people dying because you never get used to it, but you get used to handling the emotions of somebody dying. I remember we went back to the hotel in the evening that day in Zolder. My wife was with me and I was still very upset and crying. We heard the news that Gilles had passed away – but the next morning I woke up, had a shower and got ready to go to the track to race. My wife just could not understand how we could go back to the track where somebody had just lost his life. The incident is still so vivid in my mind. It was that day when I learned how to completely lock away any bad thoughts, bad memories and bad pictures. I found a way of creating a little safe in my brain where I would lock things like this away until the end of the race. Then and only then would I allow the emotions to come through.”

Lessons from the life and death of Gilles Villeneuve. Gilles Villeneuve was born 66 years ago this week. The Canadian died at 32, but in the years that followed became F1's greatest cult icon. By Jim Weeks. January 21, 2016.

More than three decades after his death, Gilles Villeneuve remains a totemic figure in motorsport. Arguably F1's greatest cult icon, he is often acknowledged as the most gifted driver not to win a world title. His home circuit in Montreal is named in his honour, he is still adored by Ferrari's Tifosi, and his son Jacques carried the family name to great success during the nineties.

As a universal favourite for fans and competitors alike his story has been told many times, so only the essentials are needed here. Villeneuve spent the vast majority of his career driving for Ferrari, won six grands prix and lost his life pursuing pole position at the 1982 Belgian Grand Prix. Despite of those wins – including Monaco in 1981 – he is most famous for two enduring events: his brilliant battle with Rene Arnoux for second place at the 1979 French Grand Prix; and the bitter feud with his teammate, Didier Pironi, which Gilles carried to his grave.

Villeneuve certainly had the respect of his contemporaries. Jackie Stewart called him "phenomenal", Niki Lauda described the Canadian as "a perfect racing driver", while to Keke Rosberg he was "the hardest bastard I ever raced against, but completely fair." Fans loved him, as did the press of the day. His death hit the sport hard; his veteran team boss Enzo Ferrari, who had seen many drivers die in his cars, was unusually affected.

His legend lives on with a strength that only a fallen icon can achieve. He certainly enjoys greater popularity than more successful drivers who have lived into old age. Death allowed Villeneuve to transcend his own era and become a hero to generations of fans who were not even on this planet at the same time as him.

In some ways this is obvious enough. Villeneuve went out at the height of his abilities. He did not grow old and continue racing when his skills had faded (something his son has been more guilty of than most). He did not become an out of touch old man trying to remain relevant in a fast-moving sport; he did not sign endorsements with questionable regimes or defend the indefensible because a sponsorship deal required it. In other words, he remained pure.

For want of a better phrase, there is also the romance of a man who died pursuing his passion. For those who did not see Villeneuve race, his death is part of a linear narrative, offering brutal confirmation of his total commitment to the sport. Once you have watched the highlight reel of his incredible scrap with Arnoux and his superhuman efforts to drag a crippled Ferrari back to the pits that same year at Zandvoort, it makes sense that he would lose his life at the age of 32. Of course a man as committed and brave as Gilles Villeneuve was destined to die at the wheel. And of course he should do it pursuing pole position.

But I'm not sure that those of us who didn't see Villeneuve race can make any real judgements on him in this regard, because death completely distorts the story. The battle with Arnoux and the shredded tyre carcass at Zandvoort achieve greater significance because Villeneuve died. His past actions are informed by the end result. Whereas for those who were there they exist as separate events, to us they are extra detail added to an almost mythical driver who we already knew lost his life.

What Villeneuve does represent is a wholly different approach to making it in motorsport. Today's future racers know at the age of 10 that they want to reach F1. They're already racing karts with paid-up mechanics and pitching up in motorhomes and wearing custom-painted crash helmets. The sport has been professionalised right down to the lowest rung. And I don't know that this is a good thing. The Villeneuve-era amateurism – amateurism in its best sense, racing first and foremost for the love of it – feels like a far more conducive environment to develop men and women of his abilities.

Villeneuve cut his teeth driving far too fast on the roads of his native Berthierville. After a few too many crashes, he graduated to drag racing events. He tinkered with his own cars, pushed them beyond their limits, then fixed what he'd broken. He did not fully understand that you could make a living in motor racing until his late teens and certainly had no path plotted out towards F1.

He later raced snowmobiles professionally, winning the World Championship Snowmobile Derby in 1974 (it was here that he honed his sense of control and balance to perfection). He won Formula Atlantic titles in 1976. Of course there came a point when F1 became his goal, but that certainly hadn't occurred by the age of 10, or even 20. And he certainly wasn't part of a professional culture that develops homogenous young racing drivers. Fast and well-mannered and in some ways smart, yes, but with many of the kinks that engender genius ironed out.

Would it do a young driver today any harm to contest a snowmobile championship, assuming they didn't break any major bones (I think a few small bones can be broken, if needs be, in the pursuit of development)? No. Did it hurt Gilles Villeneuve to begin his racing career in his late teens? Clearly it did not.

This variety of experiences helped to develop the Gilles Villeneuve who arrived in Formula One at the tail end of the 1977 season. They helped to develop, or at least enhance, the strength of character that said, "I'm going to get this ruined grand prix car back to the pits and keep fighting." In some ways racing at the lower levels is more competitive now than ever, yet it has been homogenised to the point that it teaches young drivers less about the wider world and their sport. Given that many of them won't make it as professionals, they may as well pick up something worthwhile along the way, just as Villeneuve probably learned a lot searching for a new deal with a snowmobile manufacturer in 1971.

Of course, Villeneuve also highlights the terrible waste of life witnessed in F1. He raced in the sport's bloodiest era, becoming the eighth man in less than a decade to perish in a grand prix Formula One car (and the first of two in four races in '82).

And in this sense things have changed for the better. The sport will never be perfect, because strapping human beings into carbon fibre projectiles and asking them to race will always be dangerous. Nevertheless, the statistics are better. Whereas nine drivers died between the 1973 and 1982 seasons, four lost their lives between 1983 and 2015, two of those in the same horrible weekend. Death is no longer an occupational hazard of the sport, not something every driver must stare in the eyes on a fortnightly basis. It is still there, but a lot of hard work and lessons learned have dramatically improved the sport.

Then again, the daredevil nature of the 1970s was what made men like Villeneuve so immensely popular. It was the knowledge that they could die the next time they stepped into the car that gave them that otherworldly quality and it is this that ensures they hold such allure with today's fans. You can't have it both ways.

Which leads to the final lesson we can learn from Gilles Villeneuve's life and death: that there will probably never be another like Gilles Villeneuve.

Gilles Villeneuve: "you know how my father died, so explain it to me." Louis Butcher. Published on 7 May 2020.

Friday will mark the sad anniversary of the tragic death of Gilles Villeneuve at the Zolder circuit in Belgium. Canada lost his greatest ambassador on the planet 38 years ago.

Where were you on May 8, 1982? You don't have to be a F1 fan to remember that fateful date. Because the Quebecois driver, by his exploits on the track and his charisma too, had exceeded the limits of his sport.

Villeneuve has become the idol of a people. His exceptional talent made him an exceptional driver. As we still rarely see today.

One would think him invincible, the one who was affectionately called the "Little Prince". Until that fateful final lap of qualifying in his Ferrari as he tried to get ahead of his teammate and now worst enemy, Didier Pironi on the starting grid.

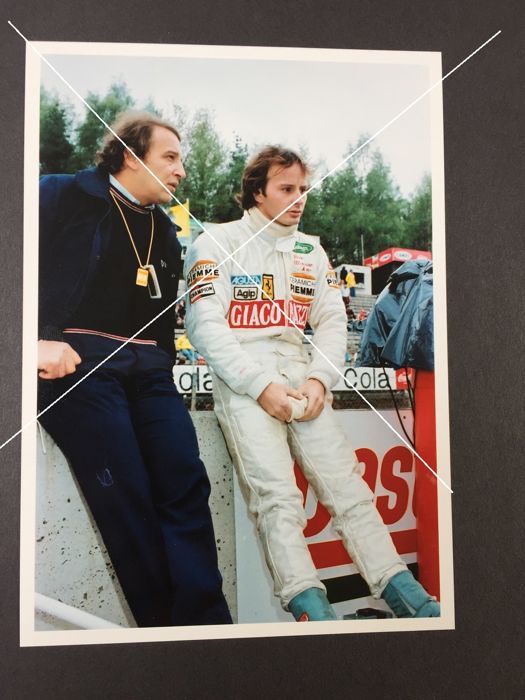

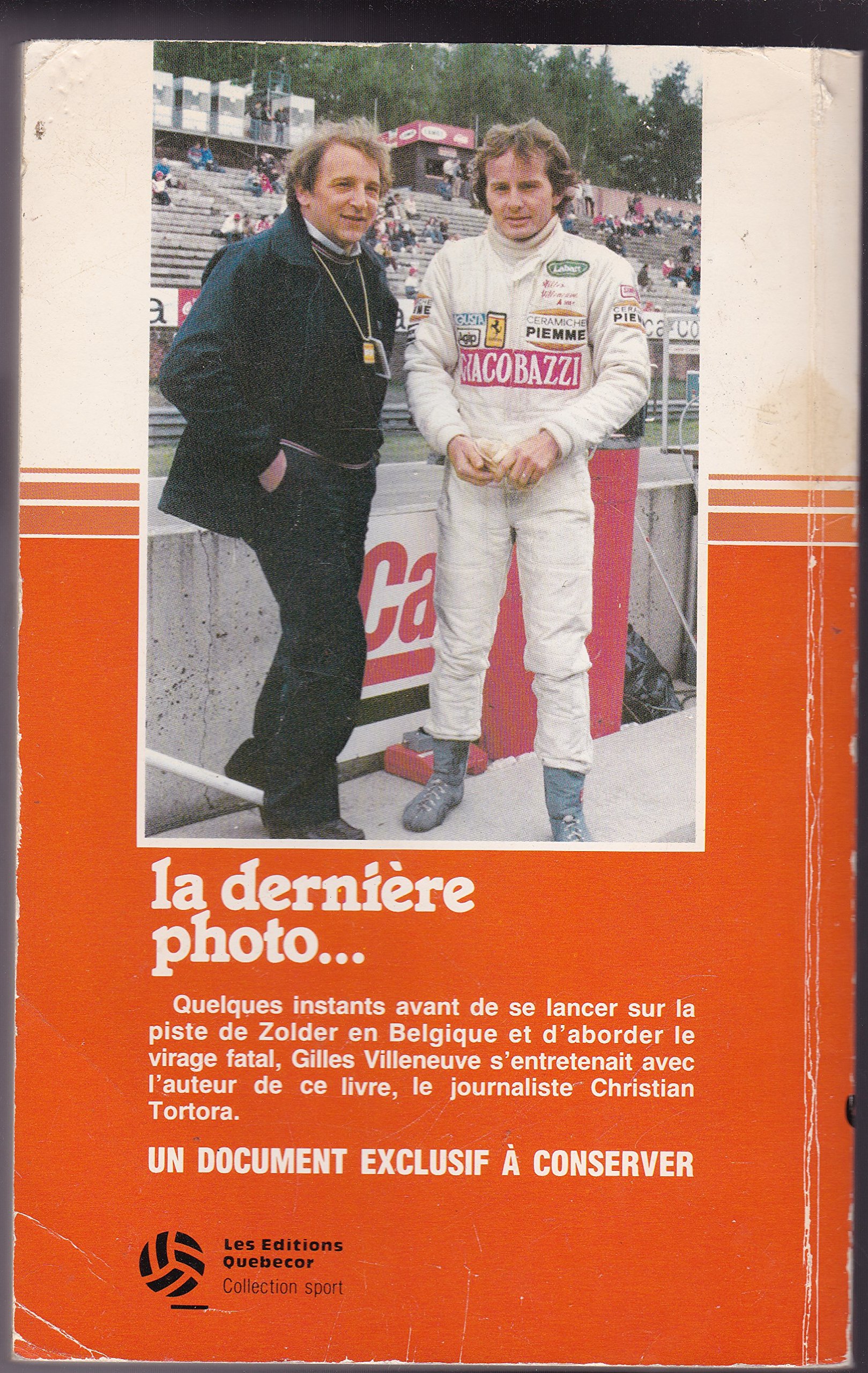

To our question, Christian Tortora replies that he was there. He was in fact one of only two Quebecois media representatives, along with Guy Robillard of the Canadian Press, to have made the trip to Belgium. To experience this tragedy live and, a few hours later, to announce the death of the 32-year-old driver born in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

In Europe, most of the biggest television stations had started their newscast by talking about this fatal swerve. In Quebec, while networks specializing in continuous information did not exist at the time, Télé-Métropole (formerly TVA) had interrupted its regular programming to devote a special program to the sudden departure of Villeneuve.

"I will tell you, in all honesty, that 38 years later, this unfortunate memory is still there in my memory and will remain so all my life," Tortora told in an interview with the "Journal de Montréal". “Gilles was somebody special.”

Two weeks earlier at the San Marino Grand Prix in Imola, Pironi had not respected the team instructions imposed by Ferrari at the end of the race.

A few bends from the finish, the Frenchman decides to overtake him, to the astonishment of the Canadian. Relationships between the two have never been the same. On the contrary, they got worse. On the podium, Villeneuve made no secret of his frustration as Pironi celebrated his controversial victory.

"Screw you."

A great rivalry was emerging between these partners to determine who would become world champion. Because it was written in the sky that 1982 was Ferrari's year. Pironi was also the victim of a serious accident, in the rain in Germany a few months later, which ended his F1 career.

“After Imola,” Tortora continued, “Gilles decided he wasn't talking to him anymore. I found myself in front of Pironi and played back the interview I had with Villeneuve after the race. He realized how furious he was. So pissed off that he told all the people at Ferrari 'fuck you'”, the friend Tortora continued. “Villeneuve felt betrayed."

Photo credit: Getty Images.

In 1979, in his second full season in F1, Villeneuve could have probably won the title, but he just followed the instructions of the Ferrari team. Rather, it was the South African Jody Scheckter who was crowned world champion ahead of the Canadian.

"It's true," Tortora replies. “Villeneuve was loyal to his team and to his teammate.”

"Villeneuve rose to legend because he passed away," Tortora said. “We agree on that. But it's not just that. From the moment he got into his car, he had an unusual resentment and determination that reminds me of Lewis Hamilton. They are exceptional drivers."

Two weeks after the stormy episode that marked the end of the Grand Prix in San Marino, Tortora came to Villeneuve.

"He told me when I arrived in Zolder that he didn't want to know anything about Pironi anymore," Tortora said.

The terrifying accident happened at the end of qualifying.

"It's a misunderstanding between Villeneuve and poor Jochen Mass," Tortora recalls. “At the wrong time, in the wrong place. To let him pass, the German lines up on the right, the same trajectory that Villeneuve had unfortunately chosen."

The driver, without a helmet and still strapped to his seat, is ejected from his car. There was nothing more that could be done to save him.

Christian Tortora was in discussions with a European colleague in the paddock of the Zolder circuit on that Saturday afternoon of May 8, when everything suddenly stopped.

"I heard sirens," said the veteran journalist in an interview with the Journal de Montreal, "and the F1 cars were all going into the pits. I realized that something abnormal had just happened. To see, going back to the press room, that Gilles Villeneuve had been the victim of a serious accident.”

"The atmosphere was so heavy," he continues. “I went to see the boss of Ferrari who then told me that it was very serious. My colleague Guy Robillard, who also covered the Belgian Grand Prix, was to be pitied. He was shaking.”

“My first instinct was to call Gilles's parents in Berthierville, Seville and Georgette, to inform them of the situation. Before they learned of their son's death hours later."

At the time, it should be remembered, the qualifications were not presented live in Quebec.

Tortora, the journalist, had volunteered to support the family and help them with their dealings following news of Villeneuve's death.

“I did something,” he said, “that I wouldn't be able to do cold today. That of managing an exceptional situation. It must be remembered that Joann, Gilles’s wife, was not present in Zolder when the fatal accident occurred. Rather, she was held in Monaco for the first communion of her daughter Mélanie.”

“The Canadian Armed Forces made a plane available to the family to repatriate Gilles' body. This plane, leaving from a military base in Germany, Tortora explains, then made a stopover in Belgium to allow Joann and his two children to return to Montreal.”

"It was unbelievably sad," Tortora said. However, I retain a striking image of the departure from Belgium to Quebec. There was Gilles’s coffin, wrapped in a Canadian flag, being directed towards the cargo hold and three soldiers on each side.”

"I'm telling you about it 38 years later and I still have chills. The people on the tarmac all started to cry.

“On board the plane, during the flight to Montreal, I was seated opposite Jacques, Gilles' son. I will always remember his words: "you know how my father died, so explain it to me"..."

Christian Tortora.

Villeneuve has been a prominent figure in F1 history, despite his far too short career. And that's not just Tortora repeating it, but most of his colleagues who, like him, have nearly 600 Grands Prix behind their back.

F1 Canadian GP 2018. Joanne Villeneuve, Christian Tortora and Melanie Villeneuve.

“They all admired Villeneuve,” Tortora says. We still talk today about his memorable duel with René Arnoux, at the Dijon-Prenois circuit, in France, in 1979. Of his victory in Montreal in 1978 and his other anthology races including that in Jarama, Spain, where in 1981 he won when only 1.2 seconds separated the top five at the finish.”

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment