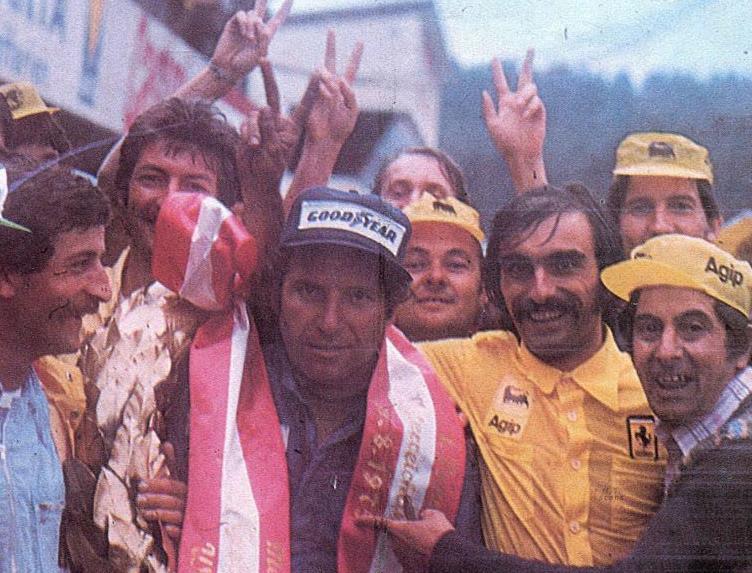

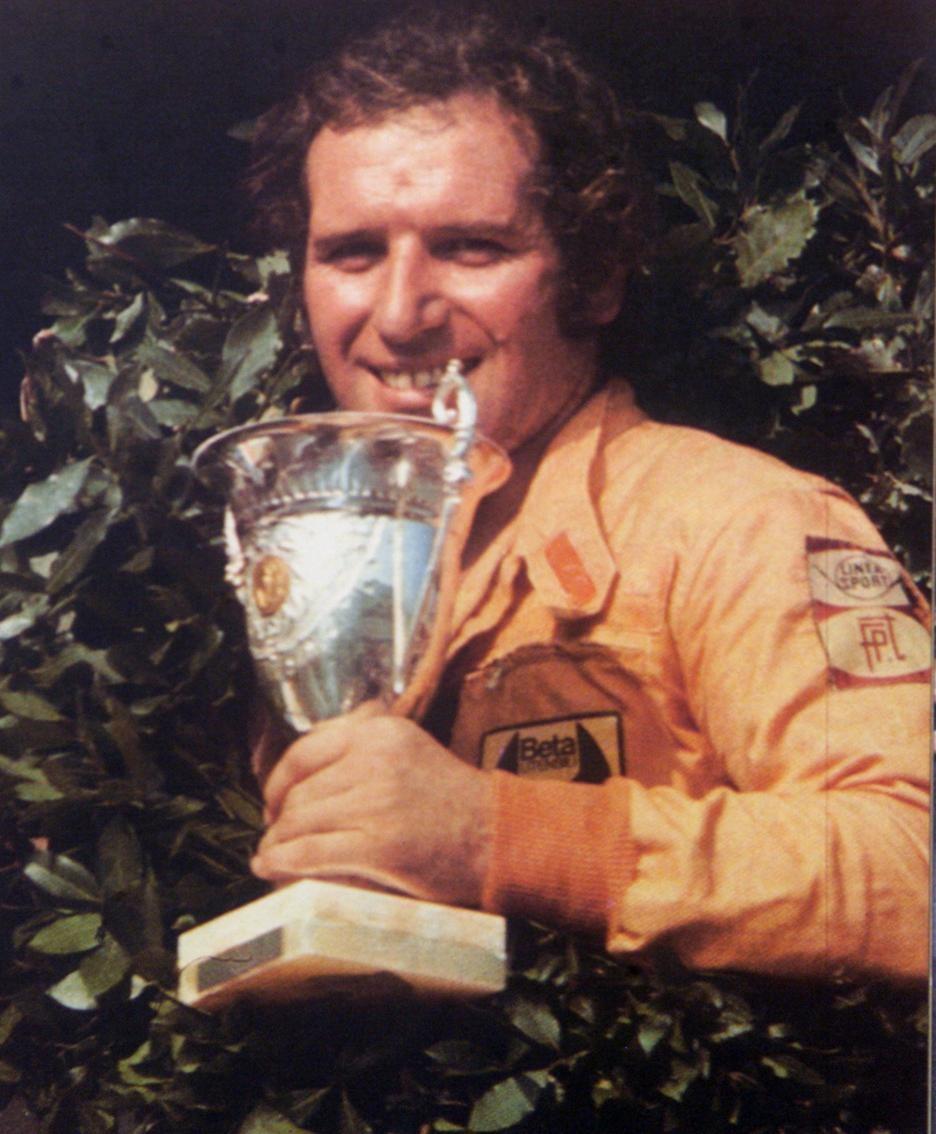

Austrian Grand Prix, 17 August 1975, first and only win of Vittorio Brambilla in Formula 1. In a superwet race he, who on water flies like no one, the first across the line, was so happy to raise his arms. He spun off, the orange nose of his March wrecked by the guard-rail. A trophy to put in his Monza’s machine shop for years. Even Ferrari mechanics celebrated him during his epic slowing down lap.

Going to the track to him was like covering the same distance needed to buy him a paper or to go shopping. In “his” Monza circuit a square was named after him. In 1973, meeting up with Enzo Ferrari talking about his possible arrival in Formula 1 for the 1974 season, Brambilla asks: “Commendatore, I’m here, you can see I’m not bad. Would you have a car for me?” Ferrari: “choosing Lauda and Regazzoni I have set a schedule that should walk me down the world title. You are good, but for the moment I don’t have a car for you”.

Very fast driver Brambilla, seized with passion, with courage. Formula One, where he would have deserved better than an only victory, was a hard-won achievement, not really lucky. 79 participations, a victory, a pole position and plenty of cars not suited to glory (March, Surtees, Alfa Romeo); and a serious accident in his home town Monza in 1978. On the other hand “il Vittorio”, as everybody just called him, has gone his whole life on track, starting with karts, racing bikes, racing all kinds of single-seater cars. Grew up in a garage, his father Carlo as his first teacher and his older brother Tino being a backup guy, partner, opponent for him. Tino and Vittorio were competing, winning, elaborating bikes and cars, riding very fast and amazing "Guzzi V7” around the city. The bar, the in-the-round place, was called “Il Bar degli Stupidi” – “Bar di Stupid” in local dialect – (the Foolish Bar). And it was a place of sensational ideas. Challenges of all kinds. A bar, because once, not that long ago indeed, half of life was spent in there and the rest out there. Residents (frequenters is reductive) of that bar knew everything about women (those of the others) and engines (from "cinquantini” (50 cubic centimeters) up, totally legit), boeri (alcohol-infused chocolates with a little cherry inside) and records. As the meaning of life, if ever there was one, was right there: challenging each other, winning, or winning ourselves, which is to set a record. Whatever it was. You could spy on them, peeping through the street. The slide that led into their nest, the blue cotton overalls bearing the imprint “Castrol” on their chest, smell of castor oil, hands stained with fat. Mechanical parts, exuberance, a memorable time. The story said that crazy bets were made: bikes hoisted up on the wall that flanked the river Lambro, first one to wipe out loses; two bikes cruised on the centreline of the road in the opposite direction, at night: whoever deviate first loses; a contest between a bicycle and a "Fiat 500 Bianchina” in reverse: result: Bianchina fried and smoking; a Formula 2 car tested on State Road, among all. There were those who won a “boero” and those who won "una boccia di rosso” (a bottle of red wine). The “Bar di Stupid” is gone. And now “il Vittorio”, one of its honorary consuls, is gone too. He went into the pits on 26 May 2001. Tino resists, he’s still a lightning of speech, of tale, now that he’s gone across the age of 80.

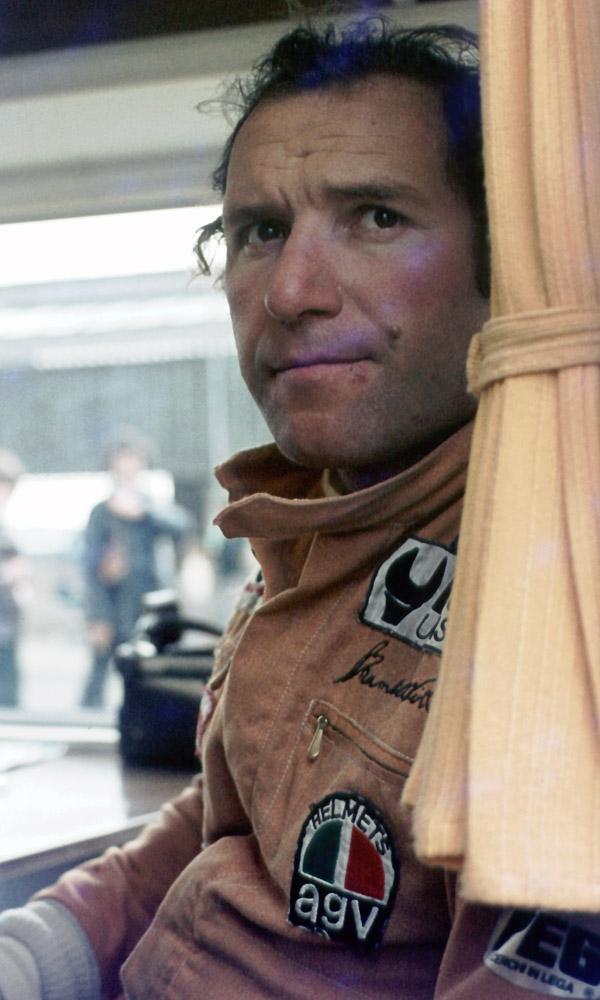

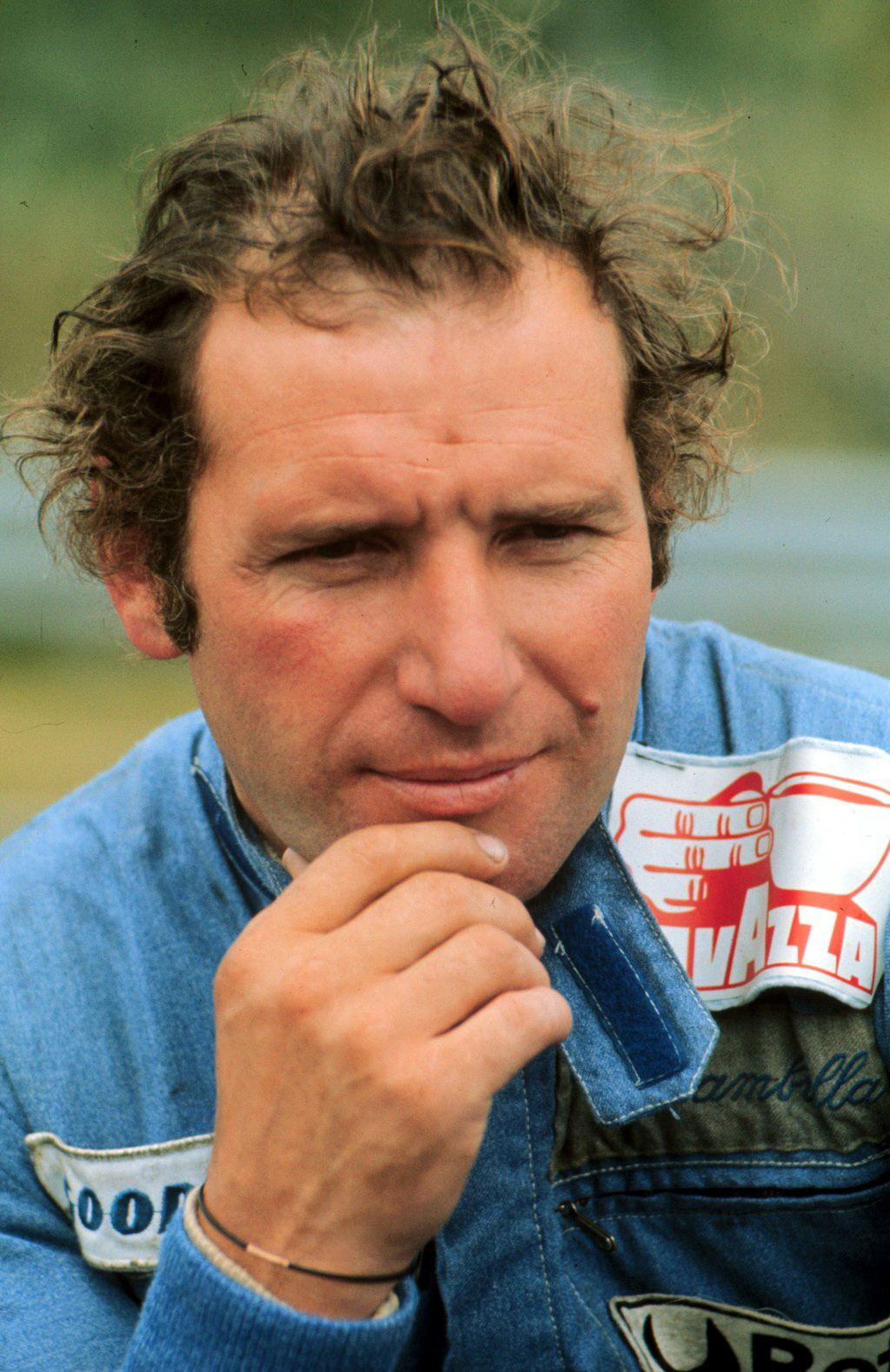

Vittorio Brambilla.

From their father Vittorio, who they lovingly call “il capo” (the boss), the children Carlo and Roberto have learned not only a profession but also the discipline, order, accuracy every time they come into contact with an engine in their garage in Vedano. Vittorio Brambilla was capable of “pastrugnare con bielle e pistoni in officina” (trafficking with rods and piston in the garage). “La passionaccia” (bad passion) for engines is the lowest common denominator of the Brambilla family. The coy driver from Monza preferred the company of his mechanics into the pits to the jet set characters that rotated around Formula 1. Raised among oil and carburetors, he said that to be happy he needed to be among cars and engines. Like a good man from Monza Vittorio, every Thursday, used to read the local newspaper: “to flip “il Cittadino” was a ritual, Roberto concludes, and I believe he’d still like to read an article about him”. There has been a grey “Topolino” mirror polished in Monza the day after he died for the parade of old vintage cars, with a big black bow. It was supposed to be driven by Vittorio: the son Roberto drove it instead, in his memory and brokenhearted. “A tireless worker”, his wife recalls, “when he wasn’t on track he was working in the garage. A humble person, simple, always willing to give a helping hand to friends stranded with a car, bike or for other reasons. He had started his new machine shop in via Lecco in Monza and was happy: every day he used to go there from here on his bike. Always. In the wintertime, even in the snow. The car? Only on Saturday mornings going to the shops. He was watching Formula 1, commenting on everything: he really liked Michael Schumacher even though, sometimes, he had also criticized him”.

Brambilla, romantic driver. A life for engines. It’s rather a passion than a job. A symbol in an adventurous epic of races, a million miles away from the world of the ones of today: a technician, a man of sport. That’s all. Prime example of a naive way to approach competitions, like they were a friendly challenge, to win at all costs. There wasn’t a bar bet in Monza in which the contact point wasn’t one of the two Brambilla: Tino the most exaggerated, Vittorio more reflective, but equally colourful, bloody, determined when it came to ride a bike and take a corner of the new Valassina flat. Or taking a friend from Monza to Vallelunga on a Guzzi V7 Sport, and come back home the same evening. Vittorio Brambilla had a wild driving, he never gave up. But at the same time a number of technical niceties made him appreciated by engineers. When “Vittorione” retired from competition he focused on his hobbies: to fix cars and bikes, helping his son (Carlo raced also in F3 but with little success), to be with family. You couldn’t see him a lot in racing circles, but it was like he would have been around in the constant reminder of all his many friends disseminated in any corner of the world. This because you couldn’t wish harm to Vittorio: you could only love him for his cleanliness, directness, genuineness.

Jo Ramirez, a retired employee of several sports car racing teams, knew him well: “in England he was called "Brambilla the gorilla", in the nicest possible way, of course. Vittorio was a bit mad, in a good way, really funny, always ready to play jokes and to participate in some shindig. He didn’t only like cars, but engineering and mechanics in general.” Another one who got a chance to have many of great moments together with the driver from Brianza was Giancarlo Minardi: “I knew Vittorio very well, in the ‘70s we used to ride together on tracks. We were often close with our motor homes and our tents, as back then you drove along circuits like that. Those were the days of races, of sports events cheerfully: a “salame” sandwich, a glass of wine with dirty hands, because in the meantime we were replacing engines and gear ratios. A piece of that which was automotive history, real sports history. Vittorio was a practical joker, he was “Brambillone” (big Brambilla), there are no other words to define him.”

Two Monza idols, of supporters, of ordinary people. Together on bikes, in karts and in Formula 3. Mechanics, capable to prep the engines, also “technicians”, when needed. Before being drivers. Competitors, and in the meantime allies, brothers Tino and Vittorio Brambilla from Monza. Capable of sacrifice themselves for success of the other. Like that day in 1969 at the Monza circuit. After a few laps on the Paton 500 with which he should have raced at Imola, Vittorio got back to the pits saying: “A go cum' è l'impresiun che risci de gripa” (I got the feeling that the engine is risking to seize). Without a word Tino, dressed in a blue cotton overall only, jumped on the bike, launched himself on track and … fell around the Curvone getting his arm broken.

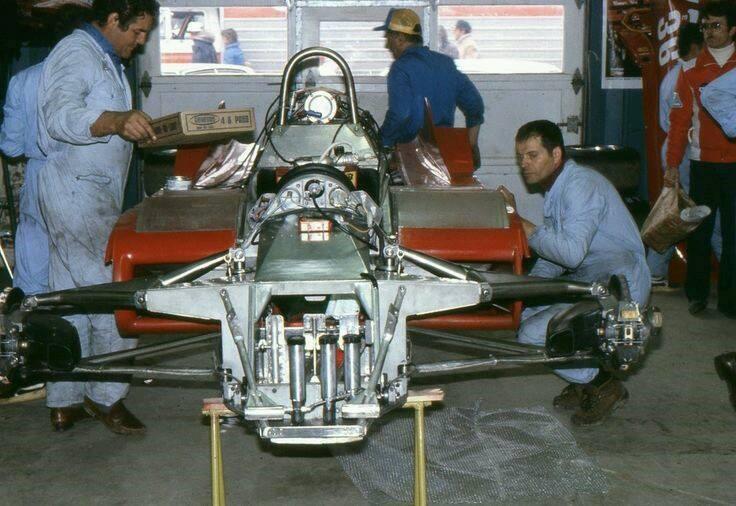

Vittorio Brambilla in his March.

In that garage at via Bellini, in front of the gate of the park of Monza, Tino and Vittorio have worked for years. At the time of bikes it was the starting point for the “zingarate” (gypsy trips) “a tutta piega” in Brianza. Among many, one entered the history: the one ended in Carnate, into the middle of a religious procession, crossed by a horde of bikers competing with one another. Moved into Formula 3, after having invented modifications, they used to test them at the Monza circuit, driving the single-seater directly on park’s roads. Rough, generous, a bit Gascons, with a little strain of crazy, but certainly quick and funny, the Brambilla brothers have brought forward by thirty years Valentino Rossi as they were showing up on track with their clan in tow. Friends willing to help out on every occasion and to always defend their idols. Vittorio was fond of saying: “at Monza I could drive with my eyes closed, the car goes on her own.”

When you get to Monza, remember Vittorio Brambilla. A big man, muscular arms, numbered smiling and hands tired by years of work in garage. A face of somebody who was working his butt off in order to get where he wanted to go; to do what he loved. Racing. Racing in any way. He had the pleasure of hosing off a young and pushy Patrese: “Riccardo, it’s ok that we’re friends, but if you make such a joke again I ….” Remember this big guy with fingers strong enough to tighten wheel nuts without any wrench. A man so frank to tell his son who wanted to race: “l’è minga el tò mistè” (it’s not your job): but who has done plenty of sacrifice to give him this chance. Remember Vittorio Brambilla and don’t forget him ever again.

Vittorio Brambilla, 1975 Austrian GP.

Vittorio Brambilla, 11 November 1937 – 26 May 2001, was particularly adept at driving in wet conditions. His nickname was "The Monza Gorilla", due to his often overly aggressive driving style and sense of machismo. He was particularly known for his 'Punch and Crunch' routine, in which, he would greet the unfortunate victim with an extremely strong handshake. He enjoyed watching the recipient wince whilst they were shaking hands only to follow this up with a rabbit punch to the back of one's neck. Brambilla began racing motorcycles in 1957 and won the Italian national 175 cc title in 1958. His older brother, Ernesto ("Tino"), was also a racing driver. He returned to racing in 1968 in Formula 3 and won the Italian championship in 1972; by the time he was already racing Formula 2, where he won several races.

In 1974, his first year of Formula One, Brambilla was as quick as his teammate Stuck, although more accident-prone. At the 1975 Swedish Grand Prix he secured pole position until a transmission failure forced him to retire after 36 laps.

Vittorio Brambilla winner of 1975 Austrian GP.

Vittorio Brambilla winner of 1975 Austrian GP.

Vittorio Brambilla, happy winner of 1975 Austrian GP.

His great day came at the Österreichring in 1975, when he won the Austrian Grand Prix. In a multiple pileup at Monza in the 1978 Italian Grand Prix, in which Ronnie Peterson died, Brambilla suffered serious head injuries when he was hit by a flying wheel during the multiple collision on the opening lap. He recovered and returned to race in the 1979 Italian Grand Prix.

Vittorio died at Lesmo, near Milan, of a heart attack at the age of 63 while gardening at his home. He reportedly collapsed while mowing the lawn. He closed his eyes manoeuvring a lawnmower. Knowing him, he had certainly rigged it ….

In piazza del Duomo (Cathedral square), to pay their last respects, the hearse waiting in the churchyard: “but who drives that "cardenzone” (contraption) there? An old frequenter of “Bar degli Stupidi” asked. “I say that as it’s a matter of respect. We’ve got to break some records going to the cemetery, it’s not like we can take il Vittorio there like any other, to a crawl“.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment