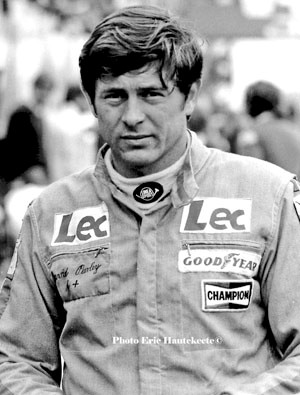

One of the most particular characters in the world of Formula 1. He witnessed one of the most terrible accidents in the history of motoring, something that, just thinking about it, makes your skin crawl even years later. He embodies the purity of an ideal. He was racing to win even at the cost of dying and the first thing mattered more than the second. Such were the drivers, it was another sport. The golden era of racing, when men were men and everything was simultaneously much more and far less tacky than it is now.

David Purley, defying death to feel alive. Bognor Regis, West Sussex, 1962. In Bognor Regis there is the sea. It is not the sea where you can get sunburnt in spring, of course, we are in the south of England; but in August the average maximum temperature exceeds twenty degrees and holiday villages have long since been built on the sandy beaches.

On that day in 1962, on the sea of Bognor Regis, a small recreational plane flies through the air. Who is piloting it is a seventeen-year-old boy who secretly took it from his father. He is called David Purley.

In an exercise in the Ardennes, the armored vehicle in which Purley and six fellow soldiers are explodes on a mine. Only one person saves himself. Needless to say, it's David.

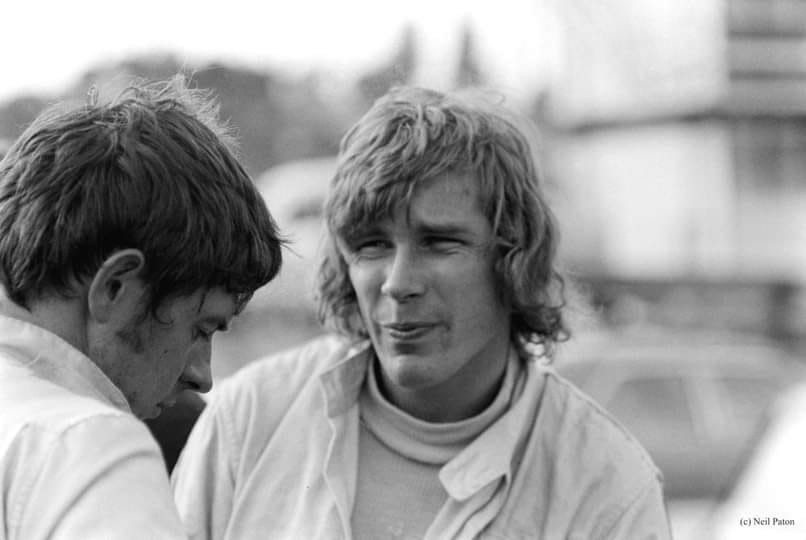

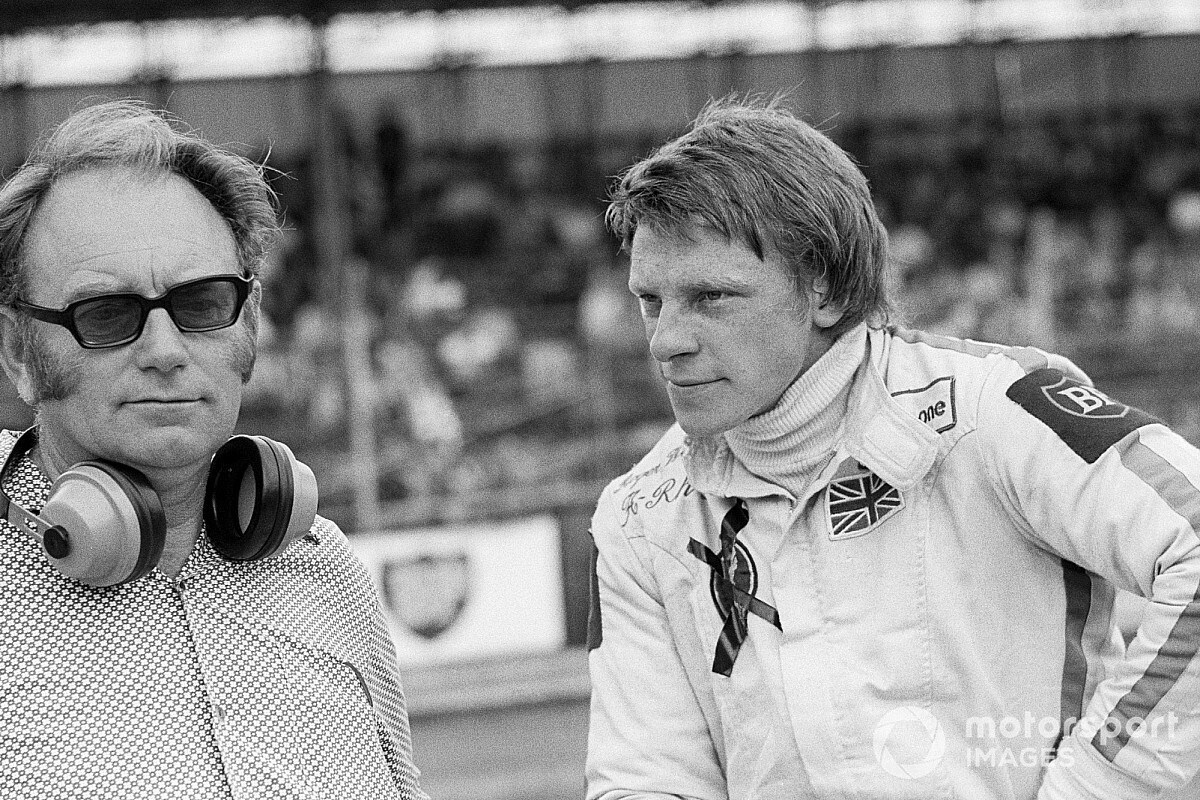

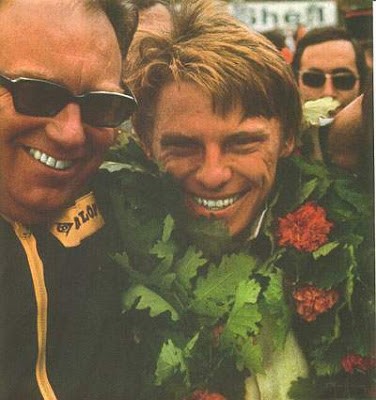

Armored by many adventures, he devotes himself to racing. He smashes many cars but also wins a lot, putting behind him future champions like James Hunt, Niki Lauda and Tony Brise, another one who had a lot of bad luck.

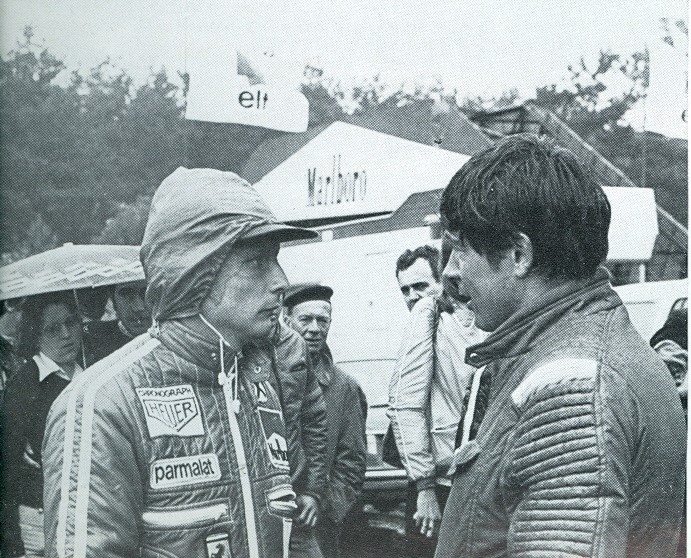

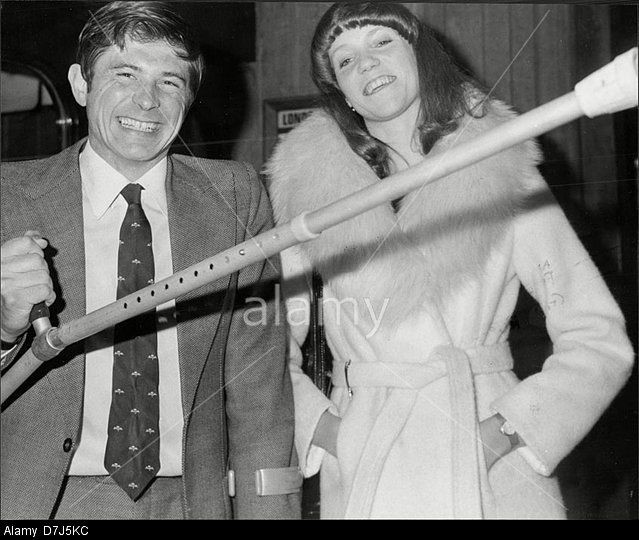

David Purley and James Hunt.

Following the death of Purley, James Hunt declared: "I think you may run out of luck, he has definitely used all his nine lives".

“There is nothing to do, the dangerous tracks give racing a wonderful extra. It's like in war. There are limits beyond which you are dead. You can never go wrong, if you do it you pay. It sounds honest to me, doesn't it? Racing should always be just that. Those who are concerned about their safety should go fishing, not racing. Endless straights, heartbreaking corners, side walls and paddock in a cow field open to all, like in Chimay: this is or should be the life of a driver. The rest, what F1 is doing is pure politics and commercialism. Puah! No, I haven't changed my mind [after Williamson's stake]. I think as before, racing must be dangerous and that's it. I always go faster in the race than in practice, because at the start I reach maximum tension, while in qualifying I don’t. In Rouen, as in Yemen, I screamed into my helmet to gain courage. I love the old Nurburgrìng, Macao, Chimay and Rouen, but beware, something different happened at Zandvoort in 1973. The bad accident can happen, but afterwards one expects that everything possible can and must be done for him. It wasn't like that there. That's all. And then the lie that Williamson was my friend: that's not true at all, I hardly knew him. I'm not a hero, I just did my duty. Like when we pulled comrades out of burning tanks in Yemen. Those who made the war know these things, acting is not poetry or altruism but only a conditioned reflex. Besides, it's not a driver's job to get off and try to save a colleague. When you go 270 kilometers per hour and stop suddenly, your head continues to go at the same speed and the world seems frighteningly slow, like in slow motion. It also happens in the pit stops, it is a very strange feeling. The truth is that, while we are racing, we do not live in the same world as you. They all treat me like a security expert now, imagine that. In fact, I'm only attracted to dangerous things. And do you know what I think for the future? I firmly believe that, if we allow F1 and racing in general to become as safe as model racing, people will get fed up and start complaining of boredom. Christ, we're paid to race. Get paid, do you understand? You will see, soon we will only see races for almost remote controlled toy cars, so no one gets hurt. No, I don't think any of us are self-harming or that the public wants to see a driver looking pretty bad, but remove completely the possibility of this happening and the punch in the stomach that racing gives you will no longer exist. Ours will no longer be an extreme sport.” David Purley

His thought belongs to another time but it is difficult to forget one like this.

Roger Williamson

Roger Williamson was born in Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire. He won the 1971 and 1972 British Formula 3 Championship titles.

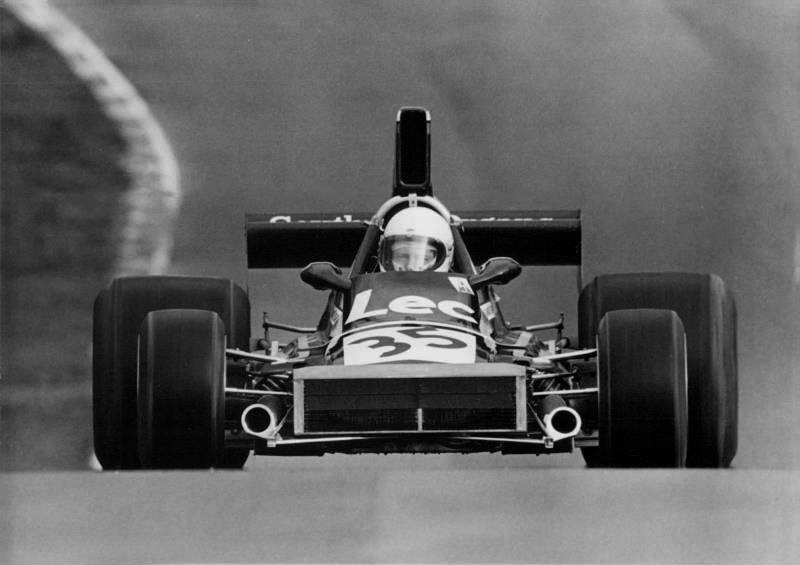

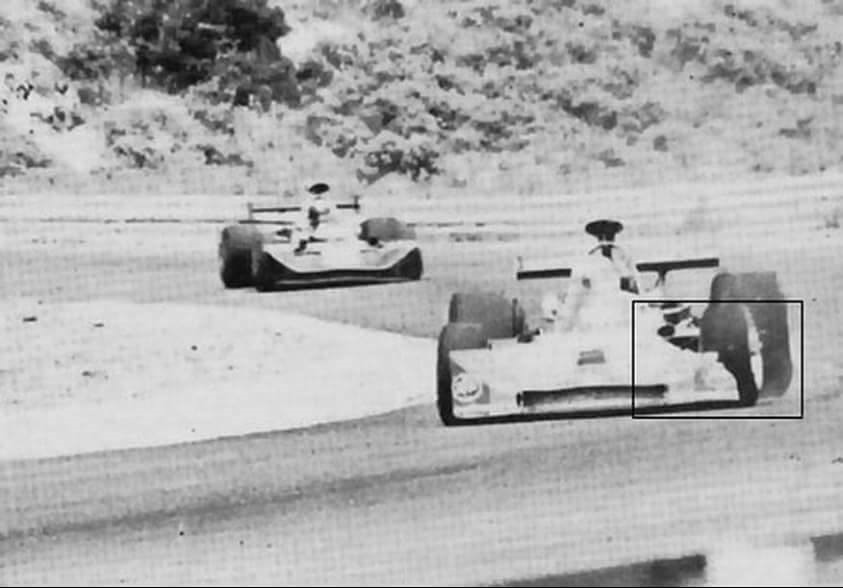

Roger Williamson, March 731.

In 1973, he was offered a drive in the March Engineering works Formula One team.

Williamson and Purley at Zolder in 1973.

Williamson and Purley at Zolder.

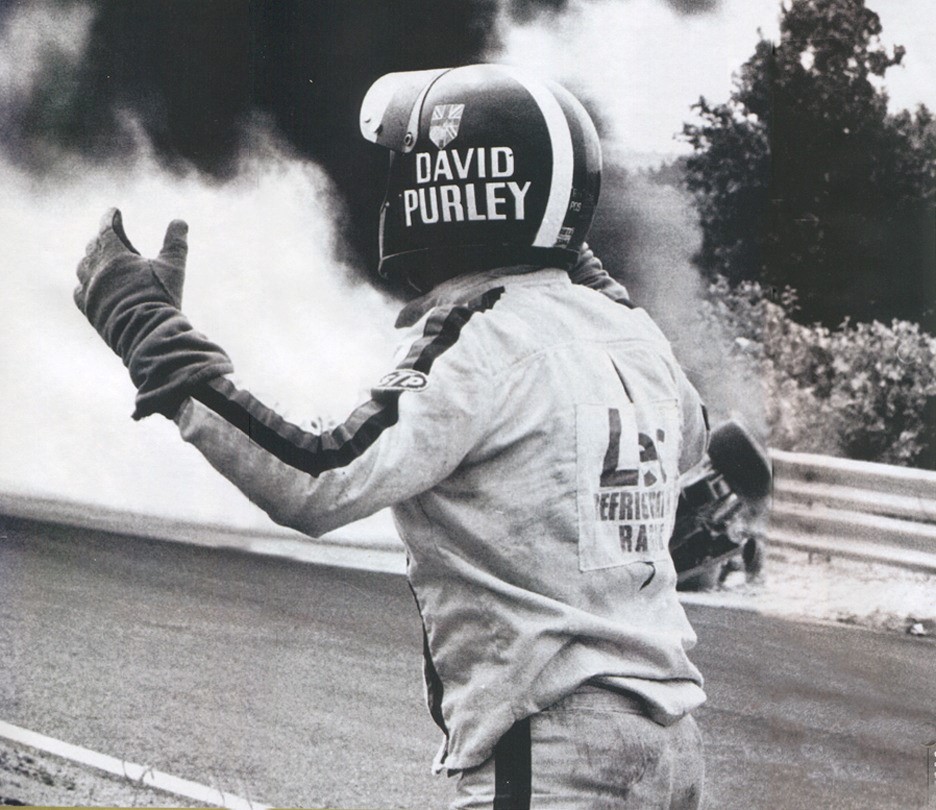

This was after testing for the BRM team and being advised not to take the drive.

After his Formula One debut at the 1973 British Grand Prix, Williamson’s second Formula One appearance was at the 1973 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort Circuit. On his eighth lap, a suspected tyre failure caused his car to flip upside down and catch fire. Williamson had not been seriously injured by the impact, but was trapped under the car which was swiftly engulfed in flame. The track marshals were both poorly trained and badly equipped and did not assist him. Another driver, David Purley, upon witnessing the crash of his friend, abandoned his own race and pulled over in a desperate and valiant attempt to rescue Williamson. He ran across the track to Williamson’s car and tried to turn it upright, before grabbing a fire extinguisher from a marshal and returning to the engulfed car. He emptied it on the car and signalled for others to help. Purley’s efforts to turn the car upright and extinguish the flames were in vain and the marshals were unable to handle the vehicle without flame retardant overalls. Purley later stated he could hear Williamson’s screams from underneath the car but, by the time the first fire engine arrived and the fire was extinguished, Roger Williamson had died of asphyxiation. As most racers mistakenly identified Purley as the driver of the crashed car and therefore thought the burning car to be empty, none of them stopped to help and the race continued, even as Purley stood on the circuit and gestured with his hands for them to stop. Furthermore, the track marshals were wearing normal blazers and not the fire-resistant overalls which the drivers wore and thus were not willing to go near the large flames.

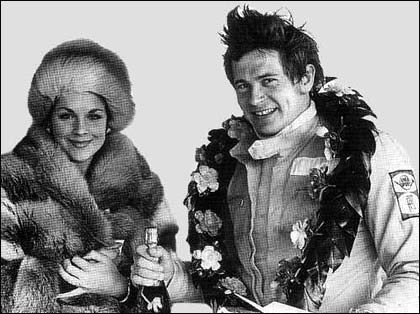

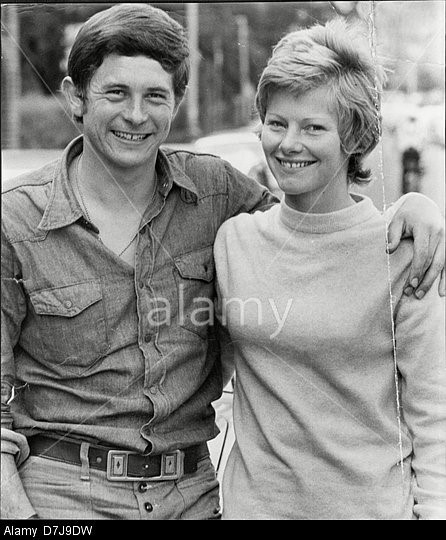

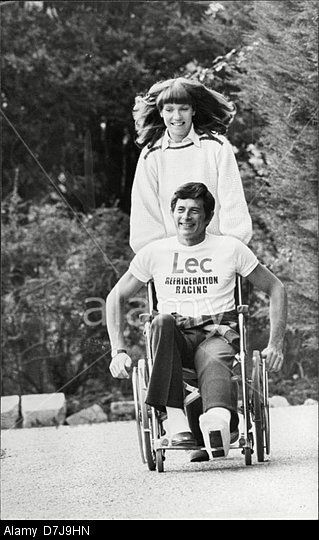

David Purley and his first wife Jane after his investiture at Buckingham Palace in London, 26th February 1974. He received the George Medal for bravery after his attempt to save fellow driver Roger Williamson.

Purley was later awarded the George Medal for the bravery he displayed in attempting to rescue Williamson. Williamson’s incinerated remains would later be cremated with his ashes being sent to an undisclosed area. In the years following the accident, fire-resistant clothing would become mandatory for all trackside marshals so that they would be able to assist in the event of a fire. The next few years also saw a noticeable increase in drivers stopping at accident sites to assist in rescue efforts, notably at the 1976 German Grand Prix.

In 2003, on the thirtieth anniversary of his fatal crash, a bronze statue of Williamson was unveiled at the Donington Park circuit in his native Leicestershire. Then-owner Tom Wheatcroft had provided financial backing to Roger Williamson and described the day Williamson died as “the saddest day of my life”.

The confrontation between Purley and Lauda at Zolder in 1977.

Run rabbit! The joy of David Purley’s first F1 finish in the new Lec car wasn’t shared by Niki Lauda. By Rob Widdows.

Martin Dixon has been working in the pitlanes of this world since he was a teenager. He retired once, but now he’s back as chief mechanic for Team Canada in the A1GP series.

In his first year as a mechanic something happened that doesn’t happen to many of these guys. He won a championship.

David Purley in 1976 on the podium in Thruxton with the winner's trophy.

Working with David Purley’s Lec team, they won the 1976 Formula 5000 series and the world, they thought, was theirs for the taking.

Formula 1 provided something of a reality check. The little team from Bognor Regis made its debut with its own car at Jarama in May 1977, where it failed to qualify (the team had run a part-season with a March 731 in 1973). Undaunted, Lec skipped the expense of Monaco, returning to fight another day at Zolder in June. But first it had to pre-qualify.

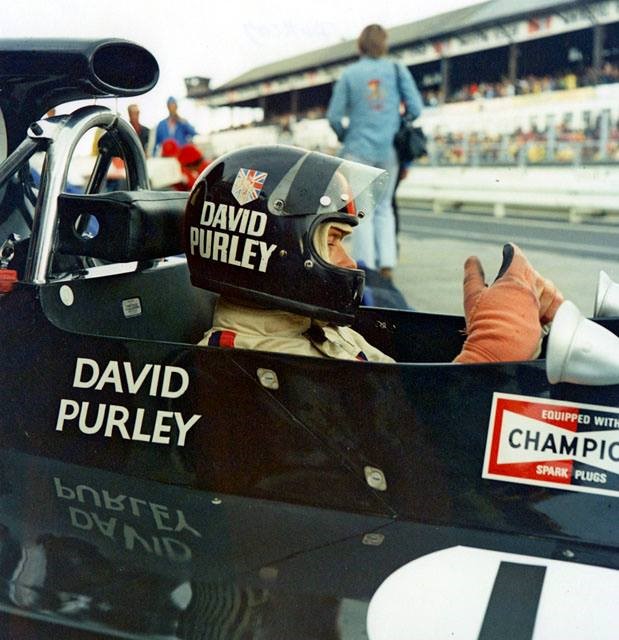

David Purley practicing in the rain at Zolder.

“It was strange, but exciting,” remembers Martin. “I’d done my apprenticeship in the truck garage at Lec Refrigeration, then joined the racing team in 1976. I was only 19 and here I was, in the pitlane at Zolder, even if we were down the far end with all the other rabbits. That’s where they put you when you had to pre-qualify, squashed up with the other privateers. We’d built the car in a real rush, there were only five of us in the team and we worked all night to get it ready. Mike Earle was our team manager and David was around, both of them pushing us on and we made it into qualifying.”

David Purley at Zolder from the rear.

Now they had to get into the race. “It was daunting,” says Martin. “There we were, sandwiched between McLaren and Ferrari in the pits. McLaren had just won the championship with James Hunt and there’s us in our Lec Refrigeration overalls and the car we’d built in a shed behind the fridge factory. We even built the engines ourselves. But we qualified for the race and most people seemed pleased for us.”

Sunday June 5 dawned cold but dry. But there was rain in the air and the weather was to play an important role.

“David made a good start from the back and he was driving really well, very fired up. Then the rain arrived and everybody started coming in for tyres. But David stayed out, the rain never bothered him and climbed through the field. Next thing, we’re leading the race. Of course, we had to stop for tyres and, when he came into the pits, he switched the engine off. I had no idea why, but we had to get the thing fired up again. The starter motor had slipped away from its bracket and was no longer connected to the flywheel. I grabbed a bloody great hammer and started bashing it back into place. It was a bit embarrassing for a young bloke like me among these big teams. David yelled to the McLaren guys – ‘hey, give us a push’ – but we got the starter motor back in place and off he went.”

What came next was to have some spectacular ramifications after the race.

“David went back out in front of Niki Lauda’s Ferrari. The track was drying fast and Lauda was back up to speed. But David wasn’t about to let him pass – I don’t think he knew who it was. It stayed like that, Lauda shaking his fist at David, until he squeezed past to take second behind Gunnar Nilsson’s Lotus. Ferrari wasn’t too happy.” Purley finished in 13th place, but the drama wasn’t over.

“There was a sudden commotion in the paddock,” Martin remembers. “We were knackered and wanted to go home. Then along came Lauda, with his entourage and he wanted to talk to David. He made some fairly derogatory remarks about rabbits and David made some references to rats and there was a bit of a shouting match. Somebody, might have been Mike, said – ‘go on, David, bite his other ear off’ – and it went on like that until Lauda just walked away. If he didn’t know who the man in the red car was at the time, David definitely knew now.”

That night, Lec mechanics Martin Dixon and Barry Pickard slept in the truck. They’d missed the ferry to Dover. Those were the not-so-glamorous days for the spanner men.

After joining Lec in 1976, Martin Dixon moved to Onyx from 1979 - 91. He then joined 3001 International, running the works Reynards in the US and ran his own American Le Mans team. A spell at Carlin running Team Lebanon’s A1GP car preceded a move to Team Canada, where he engineers Robert Wickens’ car.

Looking back on David Purley, GM. 24.09.2016.

David Purley at the 1977 British Grand Prix. Motorsport Images.

When David Purley’s Pitts Special crashed into the sea off Bognor Regis on July 2nd, motor racing lost one of its most popular drivers. The widespread shock and grief experienced by so many was not because David Purley was a great driver, he was not though he was probably a better one than his results suggest, but because David embodied so many of the qualities which we like to think our sport represents.

Some bemoan the lack of “characters” in the sport these days yet Purley was as large a character as motor racing has known. When the news of his death came, so many of us began recalling our fund of “Purley stories” – grief had not hit us at first, none of us seriously thought he’d make old bones but all of us secretly felt he was indestructible. Remembering him through many hilarious anecdotes seemed natural, he was so full of life, he lived life so much to the full, that it was natural to recall him with his ready smile and mischievous giggle. He was the sort of man that most of us would like to have been.

David was born in 1946, the only son of Charlie and Joyce Purley. Charlie is a man of little formal education who began his business career by buying and selling crates of fish which he trundled around on his bicycle. Eventually he turned a back street electrical repair shop into the giant Lec Refrigeration business of which David eventually became a director.

A wealthy father is no handicap for a racing driver yet David rebelled against what could have been an easy path through the family business he was too much a chip off the old block for that. In later years, David was to accept family help with his racing and was to join the company, but first he had to demonstrate his own independence.

When he was 16, he had his first unfortunate encounter with mechanical failure. He was at a mixed boarding school and twice his alarm clock failed to go off… When he twice was discovered where he ought not to have been, he was expelled. He was not, anyway, cut out for the academic life.

At first he went to work for Lec, as the company pilot, but a blazing row with his father saw him leave after only nine months. Always one for an exciting life and possessed with a good head for heights, he joined a demolition gang as a “top man” working on tall buildings in London, a pretty dangerous job in winter when ice covered the bricks.

Eventually his gang broke up and he left. Driving home he was passing by an Army recruiting office, thought it seemed like a good idea, went in and signed for three years with the Coldstream Guards. His mother was not amused when she found out.

Although he was keen to see action as quickly as possible, he accepted a Commission and, after two years at Sandhurst, was posted to Aden with the First Parachute Battalion. During his training, he’d survived the first of a number of close shaves when his parachute became tangled with that of his instructor. For 90 seconds he descended to earth sitting on top of his instructor’s ‘chute, holding on to the air escape hole. “It was a heavy landing,” he would say later.

Beginning to make a name for himself, Purley follows the leading the pack Ronnie Peterson, Carlos Jarque and Patrick Depailler in F2 here at Anderstorp ’74. Motorsport Images.

Service in Aden was no picnic, it might have been a small trouble spot but it was a nasty one and Purley received his full quota of mortars, grenades and machine gun fire. “Under those circumstances, you’ve got to have a certain lack of imagination. It’s no good being highly sensitive when you’re firing or being fired on. There were times when I’ve never been so frightened in my life. What happened out there, what I did and what I saw, has never worried me, but it made me hard. I won’t be pushed around by anyone.” Purley rarely spoke of his periods in action, but he was certainly at the sharp end of things. When later he was hailed as a hero for his attempt to save the life of Roger Williamson, his army days helped him keep his sense of perspective. He had his own ideas about heroism.

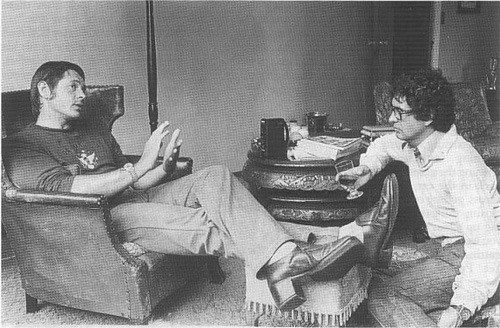

David Purley and Derek Bell.

In 1968, while still in the army, David was introduced to motor racing by his neighbour, Derek Bell. With a cousin, Derek Ridler, he shared an AC Cobra but by his own admission was a very hairy driver and he eventually wrote off the car at Brands Hatch.

Motor racing had got into his blood, however and the following year he was out with a Chevron B8. Purley was quick, but unsympathetic to his machinery and it was a year of blow-ups rather than results.

At the end of 1969, he left the army and set up his own F3 team with two mechanics.

David Purley after winning an F3 race at Chimaj in 1970, aged 25. David's helmet hair pre-empt typical British male hairstyles by about 30 years.

It was a time for learning and his results were uneven yet, starting in 1970, he scored a notable hat-trick of wins on the Chimay circuit in Belgium.

David Purley, Chevron B18, in 1971 at Silverstone.

David was not one of those drivers who are motivated by the thought of becoming World Champion, rather he sought personal challenges and responded to them and his attitude to Chimay indicates why, by comparison, he was often comparatively lacklustre on other circuits.

David Purley at Rouen in 1974.

“Chimay was a very fast, dangerous, circuit which used to get my adrenalin going. Throughout my racing career, I always drove faster when I was slightly nervous: at Chimay, the Nürburgring, at Rouen. It gave an edge to my driving. For this reason I was never particularly quick in practice unless we’d had problems and I had to screw myself up to get a time in the last few minutes of a session.”

David Purley at Oulton Park testing in 1975.

The other side of this coin came at Oulton Park on Good Friday 1972. In his F2 debut, he claimed pole position though his race lasted only 200 yards before his throttle cable broke (the race was won by Niki Lauda in heavy rain).

David Purley in a March 722.

David might have been a better F2 driver had he had problems in qualifying but, by setting pole ahead of a small and largely mediocre field, he felt he had cracked F2 on his first attempt and so the challenge was no longer there. His only creditable F2 finish that year was third place at Pau, but then that is a tricky circuit and it was raining hard. His other achievement that year was his third Chimay F3 win.

Purley’s attempt at rescuing David Williamson at Zandvoort was one demonstration of his courage, as was his drive in the following race at the Nurburgring. He was hopelessly off the pace in practice but back into his stride by the end, when he brought his March 731 home 15th. Motorsport Images.

David began the season on pole but then floundered. He was lacking direction but a chance meeting with Mike Earle, another member of the Bognor Regis motor racing tribe, led to Mike becoming David’s team manager. Mike was able to bring not only experience but also a strong personality – Purley hated sycophants – and the two men maintained not only an enduring professional relationship but also friendship.

For 1973, a March 73B was bought for an assault on the two major British Formula Atlantic Championships and a deal was made with March for an occasional rent-a-drive run in F1. Purley had a good season in Atlantic and, by the time he began to drive in the occasional GP, was leading both Championships. As it turned out, he finally finished runner-up to Colin Vandervell in the Yellow Pages series and retired while leading the final BP round, thus handing the title to John Nicholson.

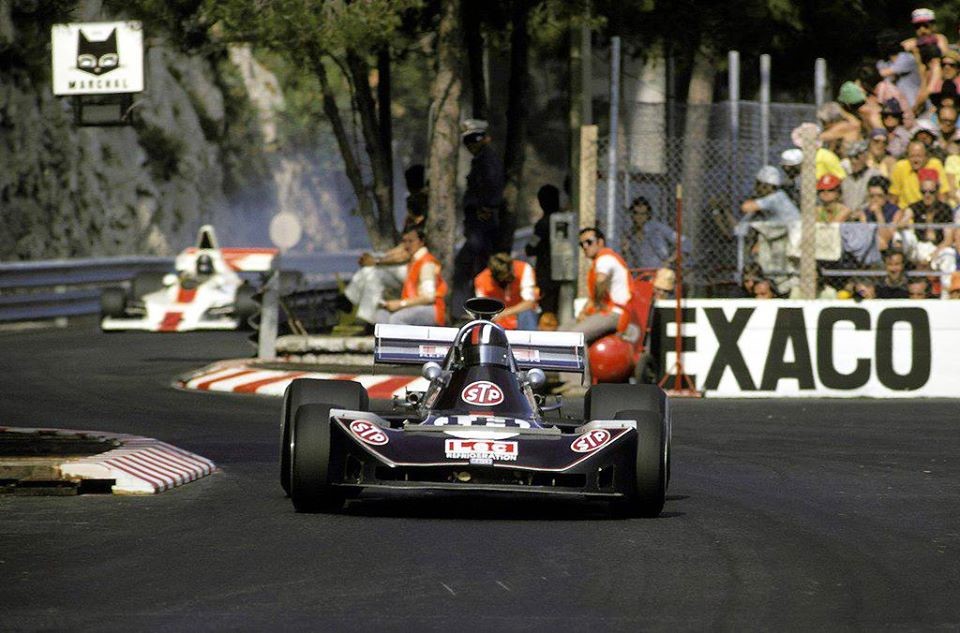

David Purley at Monaco in a March 731.

David Purley at Monaco in a March 731.

His entry into F1 was hardly sensational but he managed to qualify for Monaco and, until he crashed his car and had to scratch, was the quickest March driver, with the exception of Hunt, during practice at Silverstone. The third Grand Prix he entered was the Zandvoort race.

In 1973 two British racing drivers, Mike Hailwood and David Purley, were awarded George Medals. Hailwood had gone to the aid of Clay Regazzoni in South Africa and Purley tried vainly to save Roger Williamson trapped under his burning March. The George Medal is a rare honour and both men earned it but the difference was that Purley’s attempt was televised. Even before he received his honour David was dubbed a “hero” by the mass media, while Hailwood’s achievement received relatively little attention.

“To be honest,” Purley was to say later, ‘I think it ruined my motor racing career because afterwards I was never the racing driver but always the chap who won the George Medal. I looked on it as a great honour but, remember, I’d been in the Army and half my brother officers and the men I’d been serving with had been decorated for gallantry. I’d daily rubbed shoulders with men who had received similar awards.”

In my book David was a hero, but the depths of his courage did not emerge until later when he set himself the task of walking normally again after surviving the heaviest impact which any human being has ever survived. The incident at Zandvoort was a public example of his bravery and his instinctive caring for a fellow human being in trouble and, as such, demonstrates some of the qualities which made David Purley such an attractive personality. He showed bravery at Zandvoort but it was nothing compared with the courage he was later to demonstrate privately over a long period of time.

Purley picking up speed at the ‘Ring in 1973. Motorsport Images.

Just a week after Zandvoort came the German GP at the Nürburgring. David had to face both the pressure of publicity and coming to terms with himself as a driver. When he arrived at the circuit, the officials were at pains to drive him around to show him all the safety arrangements, particularly the fire-fighting arrangements. They meant well but had missed the point. Purley had not suddenly become a campaigner for circuit safety.

In practice for the race, Purley was extremely slow, nearly 30 sec slower than George Follmer’s Shadow which was in penultimate place. Technically he could have been excluded under the 110% rule but, unbeknown to him, all the other drivers had signed a petition which urged the organizers to allow him to start regardless of his time. Each of them knew just how much he needed the race. Grand Prix drivers are often accused of selfishness but this was an example of them recognising the personal need of a fellow professional.

David Purley at German GP in 1973.

David began the race slowly but got quicker and quicker until he was back in his rhythm. That performance was, in its own way, as equally brave as his rescue attempt at Zandvoort.

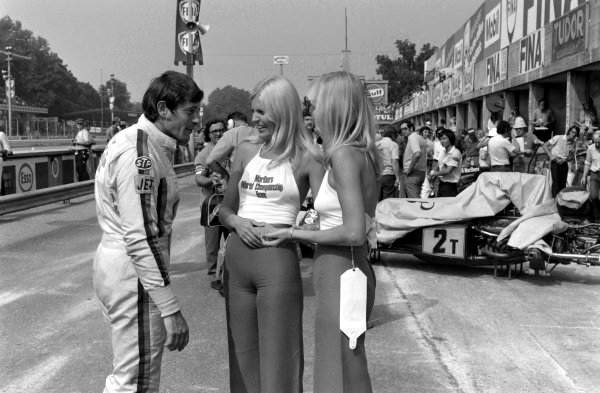

David Purley at Monza’s pit lane with Marlboro girls in 1973.

What was to be his last F1 race for the time being was at Monza where he managed to finish ninth.

Purley at Brands Hatch in 1974.

1974 saw Purley racing March and Chevron cars in F2 for Bob Harper, under the team managership of Mike Earle.

David Purley and Patrick Tambay in 1974 at Hockenheim in F2.

The European F2 Championship had a class field that year including Depailler, Jabouille, Pryce, Stuck, Laffite and Tambay and with second places at Rouen, Salzburgring and Enna, Purley claimed fifth in the series. It wasn’t a sensational season but it showed that he was on the right lines again.

David Purley in Formula 5000 at Brands Hatch in a Chevron without nosecone.

There had been some discussion about Bob Harper moving into F1 for 1975 but, when Harper decided it was not for him, Purley formed his own team to run in F5000 with a Chevron B30 powered by one of the Cosworth-developed 3.4-litre Ford V6 engines. The engine initially lacked reliability and Purley was never any great shakes as a test driver so the car remained well below its potential. David was not terribly interested in motor racing except as a personal challenge, he could never discipline himself enough to pound around a circuit systematically honing a car. That 1975 season produced two wins and fifth place in the Championship.

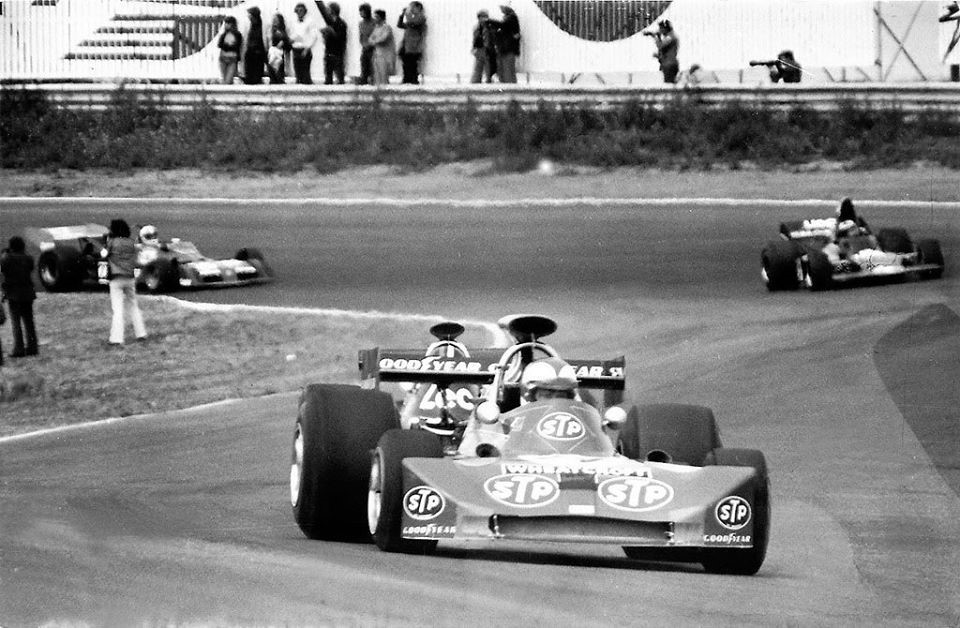

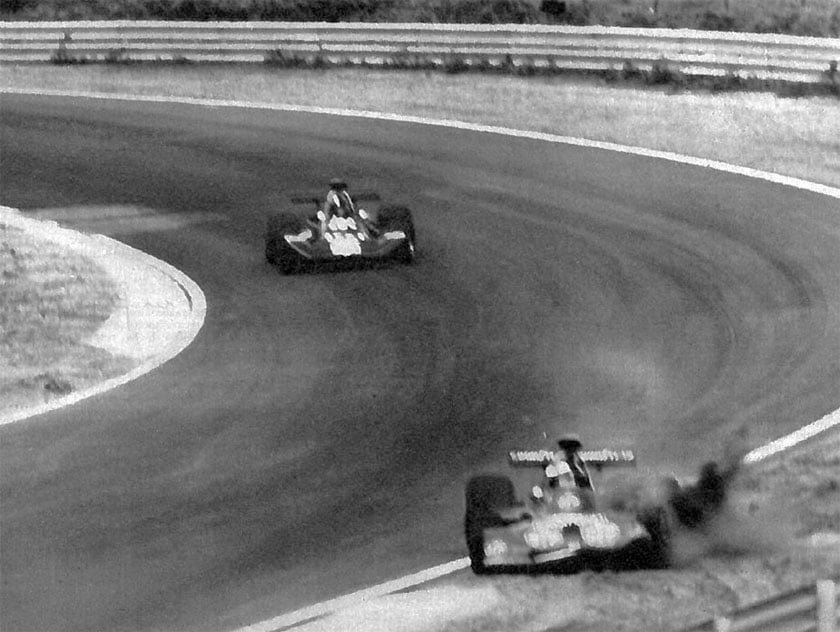

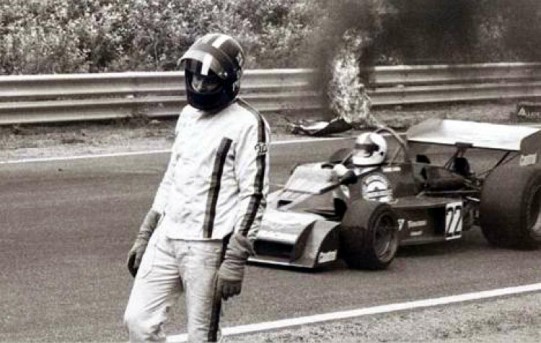

The one half lap that Purley led in a Grand Prix was at Zolder ’77. Motorsport Images.

During the winter of 1975/76, while David was in Australia, Mike Earle and the Lec team, greatly assisted by the development expertise of Derek Bell, set about transforming the Chevron. When David returned he found himself behind the wheel of a completely different motor car and proceeded to walk away with the 1976 ShellSport Gp 8 Championship taking six wins, a second, two fourths and a fifth. At last he was showing his true potential.

Midway through what was to be his last full season of racing, the decision was made to go into F1. Charlie Purley enthusiastically underwrote his son’s plans and, in return, the car was named for him as the Lec CRP 1. Building his own car was typical of David for he could equally have bought his way into one of the lesser F1 teams. He had around him, though, a team he liked and trusted, one whose strength and loyalty had been proven – it was like being back in the army and leading a platoon where every man watched out for his comrades. Former BRM designer, Mike Pilbeam, was given the task of designing “a simple, straightforward car for simple straightforward people” and it was Mike’s care ‘in stressing the car which eventually saved David’s life.

In F1 terms, the Lec team was run on a shoe-string but the car was always well presented and Purley was driving well, even if he was at the back of the grid. The early Grands Prix outside of Europe were given a miss and the team joined the F1 circus for the Spanish race for which Purley failed to qualify. He was so far off the pace that Monaco was given a miss but had, in the meantime, taken sixth in the Race of Champions. In Belgium he began to move up the grid, qualifying in 20th place and finishing 13th. In Sweden he was 19th on the grid and was classified 14th at the end. In the French GP he started in 21st slot but crashed on lap four. He had begun to find his position on the grid which all new drivers and teams have to and, if he was not giving Lotus and Ferrari sleepless nights, he was qualifying ahead of up to a dozen other runners. 1977 was a season when there was generally a surfeit of entries.

In the wet / dry race at Zolder, Purley actually led for half a lap before pitting for slick tyres and always later reckoned that he might have won had it kept raining. In truth, though, it was a freak moment of glory. Not knowing that Purley had led the race, Niki Lauda, who believed he had been impeded by him, stormed up at the end with a few choice comments about “rabbits” in F1. David’s pithy response might be translated politely as “Hie thou hither, varlet” – and Niki did.

At the next race the Lec appeared with a rabbit painted on the cockpit side.

Given Purley’s previous proven ability to qualify his car, not to mention his performance at Zolder, it was odd that he was required to take part in a pre-qualification session for the British GP at Silverstone but one supposes the reasoning was that Lec was a private team so David had first to fight for right to officially practise.

Purley leads Niki Lauda at Zolder ’77, the Austrian accused the Brit of being a ‘rabbit’ due to his driving standards. Motorsport Images.

Mike Earle: “in the first session there’d been a small electrical fire which a marshal had promptly doused. By the time we got the car back to the pits, we had 55 minutes to prepare for the second pre-qualifying run.

“Had we had a larger budget he could have switched to a second car which was sitting 95% complete in our workshop. I ordered the team to change the engine but that would have eaten into the second session and David reckoned he needed the full session to set his time. Some extinguisher foam in the throttle slides jammed them open as he approached Becketts and he went straight on and into the barrier.”

It has been calculated that Purley stopped from 110 mph in just 26 inches and suffered deceleration which briefly touched 170 g. The impact stopped his heart but prompt action by a doctor revived him. David was conscious when Mike arrived on the scene and, in shock, began to argue with his team manager about the cause of the accident and the doctor encouraged Mike to keep on arguing and therefore interested, while he was cut out of the car. The upshot of the argument was the team would have the second car ready for the next day if David was feeling up to driving but, in fact, he was not expected to survive the 20 mile drive by ambulance to Northampton General Hospital.

He did survive, though in constant all over pain for six months. During the next six months came a gradual easing of the pain and he undertook a couple of Porsche 924 races just to see if he could still do it. His performance suggested that he no longer could but that was not the way in which David Purley was prepared to leave motor racing.

In August 1979, I was privileged to be present at Goodwood when David climbed into his second Lec.

David Purley at home. He always avoided the buttoned-up blazer look associated with the ex-military, in favour of comfortable casual wear, which suited him. The shoes aren’t ‘70s glam rock platforms; after his big accident, David had one leg shorter than the other and wore big shoes to compensate. Source: asag.sk.

It was the first time he’d sat in a single-seater in over two years, his left leg was one and a half inches shorter than his right and the damage to his ankles had been such that he would never be able to run again. Had he got within five seconds of his previous best time, it would have been a marvellous achievement. As it was, within 36 laps he had bettered his previous best time. As soon as he saw the pit board he braked and called the session to a halt. The handful of us watching could not believe it, but to David it was just another challenge successfully overcome.

Purley then raced the Lec and a Shadow DN10 four times in the Aurora Championship, picking up fourth place at Snetterton. For Mike Earle that was the most satisfying result of their long association: “he came back into the pits and the crowd broke into applause. He called for me to push him round the back and help him out. He was in agony but didn’t want to show it.”

Purley pushing at Monaco in 1973. Motorsport Images.

David Purley never raced a single-seater again after the end of 1979 though, quite recently, was in negotiations to run with a team in a Gp A BMW. The family business was no longer prepared to sponsor him and who can blame it? David tried to get sponsorship but his heart was not really in it, he was too much his own man to go cap in hand for money and had no time for all the bullshit and hype.

In his latter days he did take a greater interest in motor racing as a sport rather than as a personal challenge, he would appear as a judge at meetings and Lec has supported the Racing For Britain Campaign (subscribers can buy Lec products at staff discount rates). The real point is that, when he left motor racing, he left it on his own terms.

He was not satisfied by the fact that his left leg was shorter than his right and eventually tracked down a Belgian surgeon who was prepared to undertake an operation to break his left leg, stretch it by a millimetre a day and then graft in bone to complete the operation. There were two snags, the pain would be greater than anything even Purley had known before and the operation had never been previously performed on an adult. If it failed, it would leave him a permanent invalid.

David Pudey had known the sort of pain which, mercifully, few of us ever experience and he had known it over a long period. He had also known the frustration of wheel-chairs and crutches and had become an active supporter of his local PHAB (Physically Handicapped & Able-Bodied) group. For him to coolly take the decision to spend months in hospital in agony and perhaps never walk again takes a rare brand of courage for he knew what he was letting himself in for.

Months later he was walking again and not only walking but taking part in Enduro motorcycle races and piloting his own Pitts Special bi-plane (registered G-POKE – no comment). When he bought it in early 1981 he said he hoped to make the British aerobatics team but, although he was a competent pilot capable of doing all the stunts we see at air displays and flying competitions, his routines were not tight and disciplined. “I can’t be bothered about that envelope of air you have to stay in to stand a chance in competition,” he told me. Ironically, he also maintained that aerobatics was less dangerous than motor racing.

David Purley was a man of extraordinary courage and was probably a better driver than the record book suggests. Mike Earle is of the opinion that, had he not crashed at Silverstone, he was driving so well that his Grand Prix career could have taken off and he might have become a driver in the Regazzoni mould.

Purley at the 1973 British Grand Prix. Motorsport Images.

He was also a man capable of great kindness, try to take advantage of him and he could be hard as nails but most people who met him simply liked him for his charm, his humour and thoughtfulness. When you were in his company, he made you feel like the most important person in the world.

He loved practical jokes and sometimes played them when being, say, interviewed on radio or just before going on the air in a television studio. I know, once I was in that position when presenting a radio programme, but there was never any malice behind his stunts, you laughed with him or at least tried to keep a straight face during the broadcast and then laughed afterwards.

David in 1973 with Jane, his first wife who he married in 1969. Modelling fuss-free casual outfits and disarmingly similar smiles. Note David’s massive belt buckle and very current, button flies.

David Purley and his second wife Gail Ward.

David Purley and his second wife Gail Ward.

In his final years he entered his second marriage and he and his wife Gail had a daughter. Although he had settled down and was taking his responsibilities seriously, he still enjoyed stunting his plane and was a familiar sight over the South coast. Not so long ago, he twice survived crash landings but finally his luck ran out.

As a driver, David Purley was never an “ace” nor likely to be, for he was born at the wrong time to be successful with his approach. His attitude, talent and flamboyance belonged to the Fifties. He did, however, embody so many of the qualities which are representative of motor racing at its best and, whenever great characters of the sport are remembered, one of them will surely be David Purley. -M.L.

Purley F 5000 griffin helmet.

The deceleration of David Purley. November 5th 2013. On Sunday evening, after the race, Fernando Alonso underwent physical checks by the medical center. The sensors of his F138 mistakenly detected deceleration of 25G when the Asturian passed at very high speed on a curb while overtaking Jean-Eric Vergne. 25G of strength is a lot for the body, but the mythical, legendary and romantic David Purley suffered 7 times the strength and came out alive.

This happened during the 1977 British Grand Prix. There are a lot of people enrolled in that race. So many that it is necessary, for the second time in the history of Formula 1, to resort to pre-qualifying to avoid a repetition of the events of the French Grand Prix raced a few weeks earlier where many excluded drivers, including Purley himself, threatened legal action. In those same pre-qualifying a third McLaren, with the number 40 on the nose, set significant times. A certain Gilles Villeneuve was driving it, but that's another fantastic, exciting, crazy story that Formula 1 has given us.

On the Lec number 31 of David Purley, a principle of fire develops between the engine and gearbox, but it is of contained intensity and the English marshalls have no problem taming it. The use of extinguishing material will be the key to the terrible crash. The mechanics of Lec quickly clean the extinguishing material, mistakenly believing that it has not entered the mechanical parts.

Purley launches himself on the terrible and very fast old Silverstone and the fatal fact happens. Without the mechanics having noticed it, some foam of the fire extinguisher is filtered and, in contact with the petrol, triggers a chemical reaction. This reaction causes the formation of residues with a solid consistency (very similar to the lime used in masonry) which blocks the supply valves. Bad luck would have it that the valves lock up as soon as Purley exits the Copse corner and rushes towards the Becketts.

The dynamics of the accident are devastating, Purley's Lec cuts practically straight at Becketts as if the turn of the old Silverstone had not even been there, breaks through three lines of nets placed on the track, eradicates the guard rail (incredible but true .. it was his luck!) and crashes into the embankment outside the circuit, literally destroying the wooden logs placed to contain it. The odometer of his Lec stopped at 173 kilometers per hour and the stopping distance is only 66 centimeters. According to the calculations, David Purley suffered a deceleration equal to 179.8 G. A frighteningly huge figure, no living being could withstand such a force.

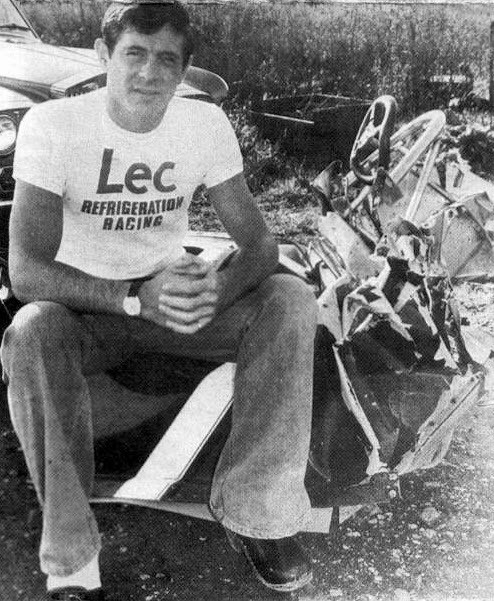

David Purley sits on the wreck of his 1977 car, after a huge crash at Silverstone. He is channeling Ronnie Peterson in his choice of outfit tight t-shirt, flares and clogs. Source motorsportretro.com.

Rescuers approach the wreck of the Lec convinced that they have to perform a macabre task, but that’s where the miracle happens. The fate that prevented him from saving Roger Williamson 4 years earlier helps him in a dramatic moment in his life. Purley has 30 leg fractures, a shattered pelvis, countless rib fractures, three sprains, head trauma and will suffer as many as 6 cardiac arrests while being transported to the hospital and subsequently before being stabilized, but he is alive. His Lec, now on display at the Donington museum run by Roger Williamson's former manager, is practically a little longer than a go-kart and it takes 15 minutes for rescuers to extract Purley from what is left of it.

For Purley begins an ordeal made up of hospitals, interventions at risk and enormous risks. After recovering his right leg is 5 centimeters shorter than his left one and the traction systems have no effect. Purley does not give up and, in Belgium, meets Professor Derweeduwen, who has already helped Jacky Ickx and is considered a luminary in childhood traumatology. The surgery that the professor has in mind for Purley has already had excellent effects on children involved in road accidents but has never been tested on an adult. It is a gamble for Purley, a "take it or leave it" that life presents to him. Purley is always him and doesn't think about it two more minutes, the choice is: to take!

David, during the 2 weeks of hospitalization, spends more time anesthetized under the knife than awake in the bed of his room in the clinic but, when he comes out, the result smacks of a miracle as the fact that he is still there to tell it. He will return to racing in Formula Aurora (English Formula 1) screaming to the world: "I'm going back to prove something to myself, it won't be racing that could knock me down", but he is no longer able to compete at high levels, the signs of the terrible crash will lead him to retire from Formula 1. During his convalescence, he comes up with a theory of life: “you are there in the winter evening and you wonder why you exist. I answer as a driver not as a philosopher. I look at my hands and say: I have always risked, I have touched death but, if I am alive now, I know why. Because in my own way I was good, I bet everything on myself and I did it".

Roger Williamson.

Formula 1 and its most disgraceful moment: when lives meant virtually nothing. Matt Hill December 9, 2010.

Formula 1 is a dangerous sport. Many people have died in Formula 1 cars and, despite the now 16-year gap since the fatality, it will happen again.

A few months ago I wrote a piece about the death of Ayrton Senna. The second half of the title for that piece was "when Formula 1 lost its remaining innocence". The key word of that is "remaining". The original innocence was taken in the incident that this piece is about.

Safety is one of the most paramount features in Formula 1 car and track design and it has to be like that. Finding the line between safety and excitement is virtually impossible. I would love to see the old Nurburgring Nordschleife on the calendar, but there is no way it will happen as it is far too dangerous.

As the decades have gone on cars have generally gotten faster and safety needs to be maintained, but sadly on occasions it has failed. For me there is one moment in Formula 1 which is possibly the most disgraceful moment in the sport's history. This moment happened in the 1973 Dutch Grand Prix.

The 1970's was the era when big business really began to get involved in Formula 1. Sponsorship money funded development and, as the development occurred, cars naturally became faster and faster. Safety was still very basic and the tracks had little to no basic medical facilities in case something did go wrong.

In other words cars were getting quicker and the tracks weren't changing to meet the needs of the cars. The cars themselves, despite getting faster, were still incredibly unsafe. They were one of the most dangerous cars of any of the main types of F1 car.

Each decade has seen a drop in the number of people killed driving Formula 1 cars. In the 1950's 15 people were killed, the 60's saw 12 deaths, the 1970's saw 10 drivers lose their lives, the 80's saw four die and the 90's two.

In the early days of Formula 1, death was simply accepted. People didn't seem to value the driver’s lives.

In America things weren't any better. In Dr. Steve Olvey's book, it spoke of an occasion when a driver was taken to hospital with suspected brain injuries. The nurse told Olvey the neurologist wasn't there and wouldn't appreciate being dragged all the way to work "for some racing driver."

To me that attitude is totally disgraceful. Just because the person was a racing driver, suddenly their life became worthless?

In 1966 Jackie Stewart at the Belgian Grand Prix had a very severe crash in his BRM and ended up pinned under the wreckage of the car with petrol pouring on to him. One spark and Jackie would have been burnt alive.

The marshals had no equipment at all to get him out and it took two fellow drivers to get Stewart out from under the wreckage. Now that story tells you how under-prepared the marshals were and you would have hoped that they would have learnt and be better prepared in the future.

That is why the story I am about to tell you seems even more disgusting than it would otherwise be.

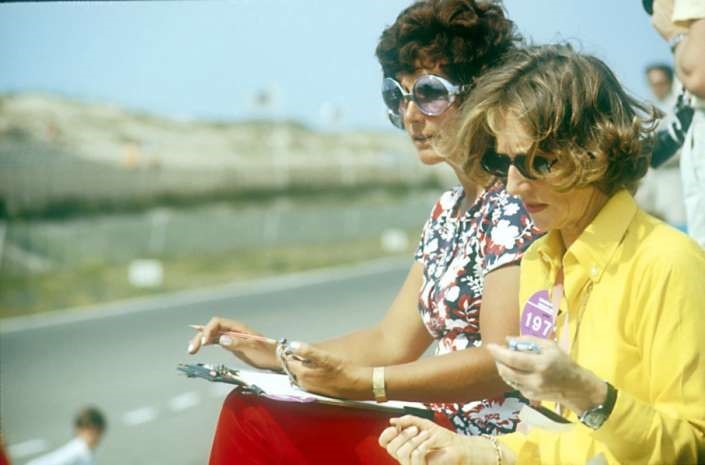

1968, Formula 1, Zandvoort, Holland. Girl timekeeping. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmich.

1970, Holland, Zandvoort, Formula 1. Bette Hill timekeeping. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmich.

Formula 1, 21.06.1970, Zandvoort, girls. Photos by Rainer Schlegelmich.

1970, Holland, Zandvoort, Formula 1. Girls. Photos by Rainer Schlegelmich.

1970, Holland, Zandvoort, Formula 1. Girls and movies. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmich.

1971, Zandvoort, Formula 1, girls. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmich.

As I said earlier, this horrific moment occurred at the 1973 Dutch Grand Prix at the Zandvoort track.

In that race, a young British driver by the name of Roger Williamson was taking part in just his second Grand Prix for the March team.

He was considered by many to be a great talent and had been particularly successful in the British club racing scene.

Roger Williamson, March 721G/731 at British GP.

In his first race at Silverstone, he got caught up in the melee caused by Jody Scheckter's crash, which took out a few drivers including Williamson.

Williamson was desperate to race in Zandvoort and somehow his car was mended and he could compete. After qualifying a very respectable 18th in his March, things looked good and he was looking forward to having a second attempt in a Formula 1 race.

After the opening few laps, he settled down into a race with fellow Brit David Purley. The two were by all accounts having a good scrap for position with Williamson having the better of it. Williamson gradually began to pull away and settle into the race.

It was Lap 8 when the tragedy occurred. Williamson got a puncture at one of the fastest parts of the track doing around 140mph and he span straight to the Armco barrier. The Armco wasn't fitted properly and acted something like a springboard, firing the March back across the track and upside down. Already a lack of adequate track preparation had made the accident worse than it should have been.

Whilst sliding across the track, Williamson's car caught fire and the burning wreckage eventually came to a standstill. Williamson was trapped under the car, fully conscious and shouting for help. David Purley stopped his car, got out and ran towards the wreckage and began to try and turn the car over.

Despite his best efforts he couldn't do it. Whilst this was going on the track marshals who did have fire extinguishers just stood and watched. Some marshals ran towards the car and decided just to stand there, not using their extinguishers. Two marshals did try briefly to help over turn the car with Purley but gave up very quickly.

The crowd seeing what was happening began to race forward and it was it this point the marshals began to act. Not to help Williamson, but to keep the crowd back.

Purley got a fire extinguisher but it wasn't quite enough to put the fire out. The fire raged on with Williamson screaming to Purley to get him out. Purley once again tried to flip the car over but he just wasn't strong enough. The marshals weren't in fire proof clothing, so they couldn't help lift the car but did nothing to put the fire out either.

After a few minutes it fell quiet from the car. Williamson had died not from burns, but from asphyxiation from the smoke.

A distraught Purley was dragged away by a marshal, who had done nothing to help and Purley reacted incredibly angrily to the person. A fire truck was just 150 yards up the road and didn't move for a good five or six minutes after the crash occurred. The fire truck was told not to drive the wrong way around the track and for good reason. But this was just yards and it wasn't even backwards, more diagonal.

The race wasn't stopped.

Some people criticized the other drivers for not stopping during the accident to help. However, they assumed it was Purley trying to right his own car. It was common then for privateers such as Purley to try and save their cars from damage and when they saw Purley they assumed he was doing it to save his car, not someone else's life.

The marshals who saw that it wasn't Purley's car had no such excuse.

Williamson should never have died in that crash, never. But, due to the ridiculously poor standard of preparation and safety, he did.

Why didn't the marshals have fire proof clothing?

Why weren't the Armco barrier fitted properly?

Why didn't the marshals use their extinguishers?

I hold this as the one of Formula 1's worst moments. It was preventable in nearly every way. But, due to mix of laziness, apathy towards safety and some would say even cowardice by some, a driver was killed.

A lot of people talk about how Formula 1 should be made more exciting and I have nothing wrong with that. But if you gave me a choice of a slightly duller yet safer race or more exciting but with a higher chance of death or injury, there is only one winner.

Formula 1 drivers are people, not robots.

The footage of this event is on YouTube. For those who think they can watch it, do so and you will have a better understanding of something that I found hard to put into words.

Purley's father was Charles Purley, the founder of LEC Refrigeration. Birth and death records show that his father's name was originally Puxley but he preferred the name Purley. His mother was Welsh, having been born in the small village of Cwmfelinfach. David went to school at Seaford College and then Dartington Hall School in Devon.

Williamson damaged nose cone in Zandvoort and Purley.

Williamson crashing in Zandvoort and Purley.

Williamson upside down crashing in Zandvoort and Purley.

A sequence of pictures taken by photographer Cor Mooij of the accident at Zandvoort won the Photo Sequences category of that year's World Press Photo. The story and film footage of the rescue attempt feature in a 2010 BBC documentary titled “Grand Prix: The Killer Years”.

Purley died on 2 July 1985, when his Pitts Special aerobatic biplane crashed into the English Channel off Bognor Regis. He is buried in the churchyard of St. Nicholas Church, West Itchenor, near Chichester.

The remains of Purley's crashed LEC CRP1 and its replacement were displayed at the Donington Grand Prix Exhibition until 2011. The second car has since been restored and now competes in historic Formula One racing, alongside a replica car built more recently.

Memorial to racing driver David Purley GM 1945-1985.

A David Purley memorial, in the form of a sculpture by the British artist Gordon Young, was erected in 2017 close to the site of the former LEC factory in Bognor Regis. It is inscribed with the words that appear on the headstone of his grave at Itchenor: "gone now your eager smile, high held head and soldier's stride, etched were skies by your elegant style and this earth enriched by your pride".

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment