Sid Watkins, historical doctor of Grands Prix, the surgeon who has seen death in Formula One. He’s the man who saw Senna’s “spirit departed” before his eyes and who turned off Villeneuve’s respirator in a cold Belgian hospital, the kind shaman who resurrected Gerhard Berger and Mika Hakkinen. After having agreed to Ecclestone’s proposal, Watkins found himself stuffed inside a rudimentary «medical car» without the rear seats, wearing a fireproof suit provided by Jody Scheckter and the anaesthetist lying on the ground. Without Watkins, who in 1985 cured him of Bell’s Palsy syndrome that had paralized half his face, Ayrton Senna was never going to be a racing myth. The two became like father and son and, when Eric Comas had an accident at Spa in 1991, it was Ayrton who Sid found on the scene of the drama. “He was holding the neck of Comas in a perfect position. “I tried to do what you do Prof”, he told me.”

Sid Watkins, F1's former medical delegate, died of heart attack on 12 September 2012 at the King Edward VII Hospital in London, aged 84. His family was at his bedside. An infectious character who would prescribe a “stiff whisky and aspirin” to all but the most serious injuries. The man who transformed F1 from the lethal sport of yesteryear, when driver fatalities were a routine occurrence, to the relatively safe one that it is today. F1’s medical delegate from 1978 until 2004, and a part of the furniture for even longer, he was an unstoppable force in terms of driving up safety standards. From introducing correct extraction techniques for getting drivers out of cockpits after accidents, to initiating moves to improve crash structures and other safety measures, Watkins helped save the lives of many well-known drivers. He also had a brilliant career as one of the world’s foremost neurosurgeons, practising in the UK and the US. Rubens Barrichello said: “it was Sid Watkins that saved my life in Imola 94. Great guy to be with, always happy ... Thanks for everything you have done for us drivers.”

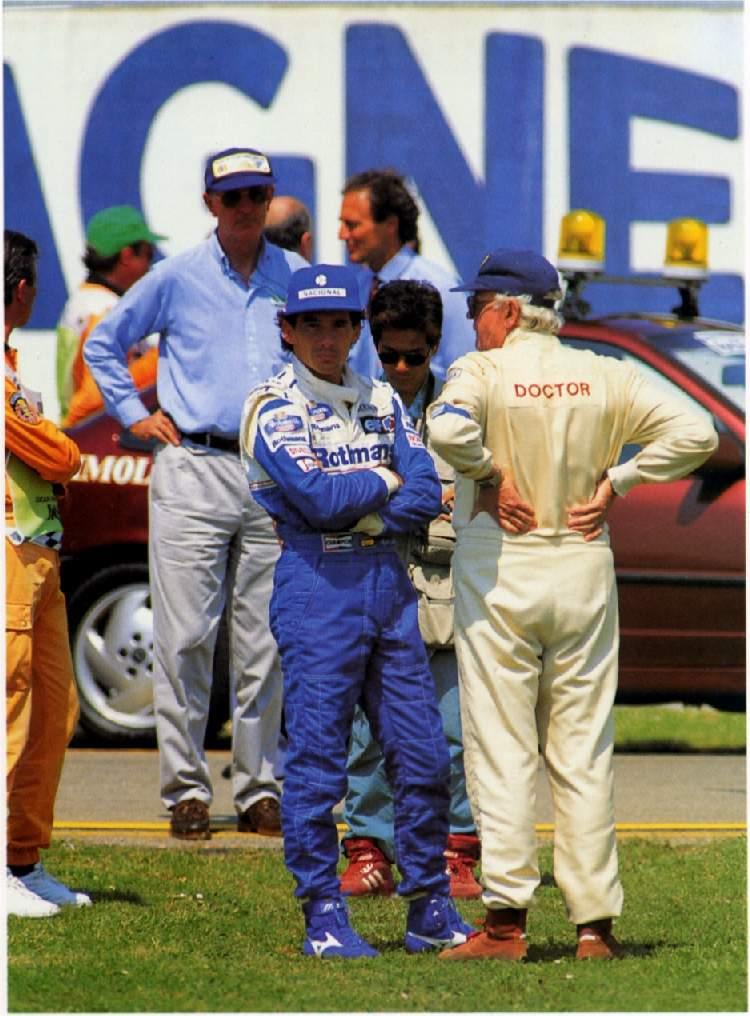

Ayrton Senna and Sid Watkins.

Ayrton Senna and Sid Watkins. Photo by Ercole Colombo.

Ayrton Senna and Sid Watkins.

A close friend of Ayrton Senna, Watkins is particularly remembered for his role that fateful weekend at Imola in 1994. A distraught Senna had sought him out at the medical centre and wept on his shoulder.

Sid Watkins and Ayrton Senna, Williams.

Watkins advised him to quit the sport “what else do you need to do? You’ve been world champion three times. You are obviously the quickest driver. Give it up and let’s go fishing”. Senna replied: “Sid, there are certain things over which we have no control. I cannot quit, I have to go on.” They were the last words he spoke to the Englishman. The following day he crashed his car into a concrete barrier. Watkins, who performed an on-site tracheotomy on the Brazilian who apparently drew his last breath, later reported: “he looked serene. I raised his eyelids and it was clear from his pupils that he had a massive brain injury. We lifted him from the cockpit and laid him on the ground. As we did, he sighed and, although I am not religious, I felt his spirit depart at that moment.”

Sid Watkins and James Hunt.

McLaren executive chairman Ron Dennis said: “the world of motor racing lost one of its true greats. No, he wasn’t a driver. No, he wasn’t an engineer. No, he wasn’t a designer. He was a doctor and it’s probably fair to say he did more than anyone, over many years, to make Formula One as safe as it is today. Many drivers and ex-drivers owe their lives to his careful and expert work, which resulted in the massive advances in safety levels that today’s drivers possibly take for granted.” Sir Frank Williams said he was more than just a doctor to F1’s drivers: “he was in all respects a very special human being.” Former F1 driver Martin Brundle described Watkins as a “visionary” who once saved his left foot from being amputated. “Sid Watkins would often prescribe ’a stiff whisky and aspirin’ unless your leg was hanging off,” Brundle recalled. “His way of saying ’just put up and get on with it.” David Coulthard added: “Sid Watkins was one of the best men I have met in my life, totally selfless. The world has lost a great.” Professor Watkins transformed safety standards in F1 by improving medical facilities and equipment at Grands Prix around the world. He was also a distinguished brain surgeon, pioneering new procedures in neurosurgery and leading research into Parkinson’s disease, movement disorders, intractable pain and cerebral palsy. In the course of 26 seasons as F1’s doctor, universally known as “Prof” by drivers and officials and “Sid” by his friends, Watkins revolutionised the principles and practice of driver safety. After a series of fatal crashes in 1994, including the one that killed Senna, Watkins was appointed by FIA, the governing body for world motorsport, to head a group of experts to advise on car and cockpit design, helmets, crash barriers and circuit configurations in order to improve safety standards.

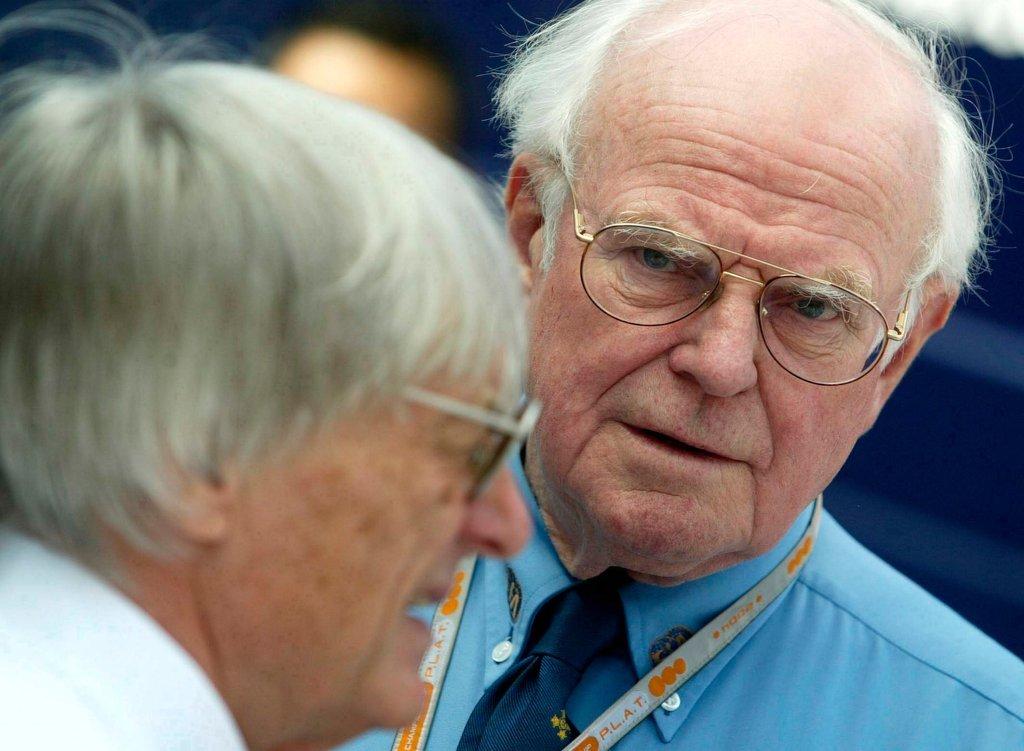

Sid Watkins and Bernie Ecclestone.

He had first been recruited to the sport in the late 1970s by the head of F1, Bernie Ecclestone, who believed existing medical facilities were inadequate and varied widely from circuit to circuit. Ecclestone wanted the same level of medical competence at each track, and hired Watkins to organise it. Some circuit owners were reluctant to spend money on more staff and better facilities and, at Hockenheim, the organisers of the GP refused Watkins entry into the race control room. The medical centre at the track was an old converted bus, and put Watkins in mind of a primitive hut he had seen at Silverstone staffed by the Red Cross. Ecclestone threatened to stand in front of the grid and order the drivers out of their cars unless he could see Watkins giving him the thumbs-up from the control room window. The organisers immediately relented. The following year Watkins returned to Hockenheim to find a brand new, well-equipped medical centre as well as a helicopter ambulance on standby for the whole weekend. By 1981 Watkins had devised a protocol defining standards for medical centres at F1 venues and emergency procedures at every circuit. Gilles Villeneuve joked: “I hope I never need you, Prof”. Watkins was in action when the Austrian Gerhard Berger crashed in flames at Imola in 1989; and also in 1990 when the Northern Irish driver Martin Donnelly was nearly killed at Jerez, only to make a complete recovery under Watkins’s care.

Niki Lauda and Sid Watkins.

Eric Sidney Watkins was born in Liverpool on September 6 1928 to Wallace and Jessica Watkins. Wallace was originally a coal miner from Gloucestershire, but had moved to Liverpool during the Great Depression of the 1930s, where he started a small business initially repairing bicycles before progressing to motor vehicle repairs. Watkins worked for his father at the garage until he was 25. He had two brothers and a sister.

He told his father that he wanted to become a doctor, an idea of which his father disapproved, refusing to pay “a single penny”. Sid won a scholarship to Liverpool University to read Medicine. Qualifying as a doctor in 1952, he researched heat exhaustion at a physiological unit in West Africa, returning to England six stone lighter, and after working in general surgery. In 1962 he was appointed professor of neurosurgery at the University of New York in Syracuse. Already bitten by the motor racing bug, he became one of the circuit doctors for the American GP. Finding the facilities at the medical centre limited: “the first job before practice was to sweep out the dead flies that had accumulated since the last meeting”. Returning to England in 1969, he became professor of neurosurgery at the London Hospital, now the Royal London.

Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn and Sid Watkins in 2009.

Then, in 1978, came the call from Ecclestone to overhaul Formula 1’s medical facilities, and to attend all GP around the world. Bernie offered Watkins $35,000 a year for the entire season. Watkins had to pay airfares, hotel bills, rental cars and all incidental expenses. Sidney accepted, and attended his first race at the 1978 Swedish GP. The existing state of affairs was often a shambles. When Ronnie Peterson died in hospital after crashing at Monza in September of the same year, Watkins blamed his death on the delay in getting an ambulance to the scene. Within a fortnight, Ecclestone had provided him with a specially-equipped car in which Watkins and an anaesthetist tailed the field on the first lap of the US GP. This procedure remains standard practice in F1 and Watkins commanded universal admiration. At the Canadian GP later that year, Watkins had to deal with the fatal accident of Riccardo Paletti on the first lap of the race. Watkins got to Paletti's car 16 seconds after impact and opened the visor of the helmet to see his blown pupils. Then, before any medical attention could be received, Paletti's car caught fire. Sid had suitable clothing to prevent him from suffering serious burns but his hands were affected. After he extinguished the fire, he took off his gloves to put an airway into Paletti's throat but Watkins' boots had melted in the fire. At the British GP in 1985, during the drivers briefing, he received a silver trophy that read:"to the Prof, our thanks for your invaluable contribution to Formula 1. Nice to know you're there".In 1986, Watkins had the responsibility for caring for Frank Williams who sustained spinal cord injuries in a car crash on a public road.

Nelson Piquet with Sid Watkins.

In 1987, Nelson Piquet crashed during practice at the San Marino GP, and was declared unfit to race by Watkins. Nelson tried to persuade officials to allow him to compete. In response, Watkins threatened to resign if overruled. The officials opted to support Watkins, and Piquet sat out the race, later admitting that it was the correct decision. At the 1995 Australian GP, Mika Häkkinen crashed heavily during the Friday qualifying session at the Brewery Bend; he was immediately rendered unconscious but did not hit his head against the surrounding wall or cockpit. Two volunteer doctors arrived at the scene in 15 seconds with Watkins arriving last and taking the action of restarting Häkkinen's heart twice and performing a cricothyroidotomy at the side of the track which he later described as his most satisfying experience during his time in the sport.

As well as his motor-racing memoirs “Life at the limit” and “Beyond the limit” (2001), he published two neurosurgical studies of stereotaxic anatomy in 1969 and 1976. He was appointed OBE in 2002. Watkins was married to Susan, a historian and biographer with whom he had six children; four sons and two daughters.

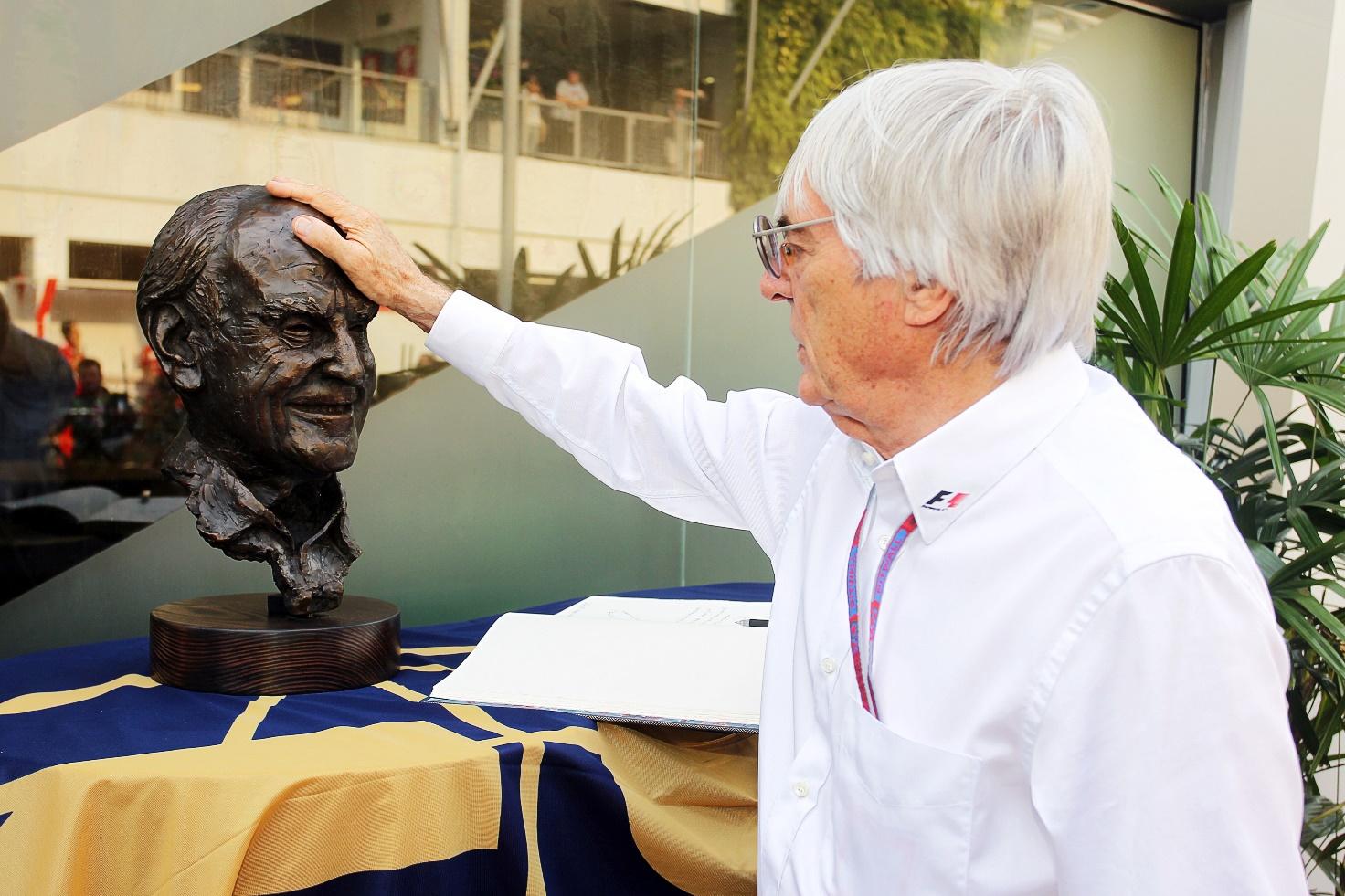

Bernie Ecclestone pays tribute to Sid Watkins in 2012.

A jovial figure with a love of smoking cigars, drinking whisky and fishing, Watkins was buried in a private ceremony near the border of Scotland on 18 September. The journalist Richard Hammond said: "he was a legend throughout motorsport, and he's still saving lives now he's gone".

Thanks so much Sid.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment