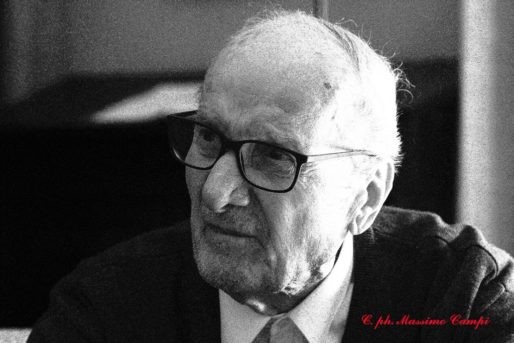

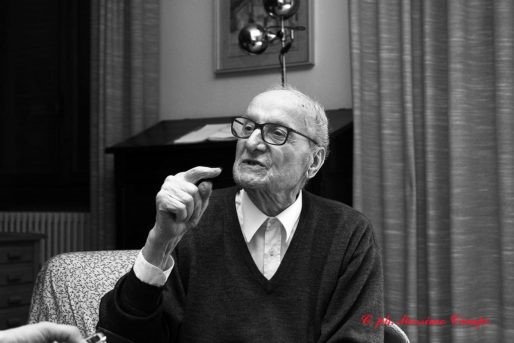

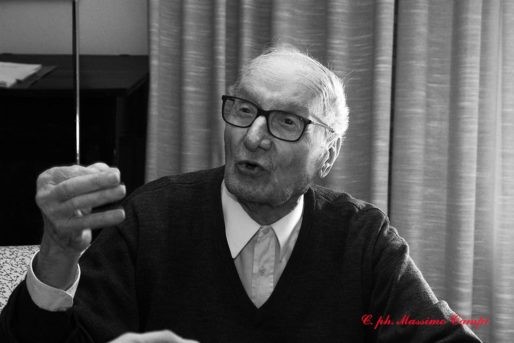

Romolo Tavoni died. He was Ferrari’s great sporting director at the time of Enzo. 21 December 2020, Milan.

One of Enzo Ferrari's closest collaborators and pillar of the Scuderia between 1950 and 1961 passed away at the age of 94.

Romolo Tavoni.

A piece of Enzo's great Ferrari goes away: Romolo Tavoni, one of the leading men of the legend of the Cavallino, right-hand man of Enzo Ferrari with different roles within the Maranello team from 1950 onwards, passed away.

Modenese from Casinalbo, fraction of Formigine, Tavoni was born in 1926.

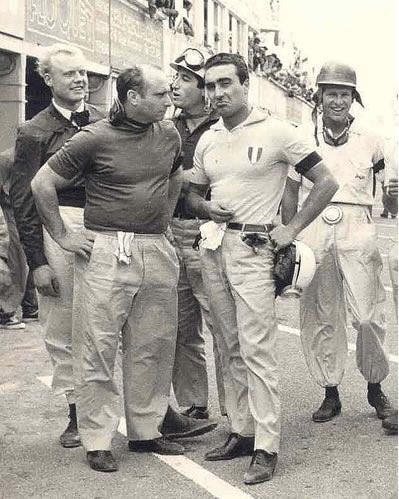

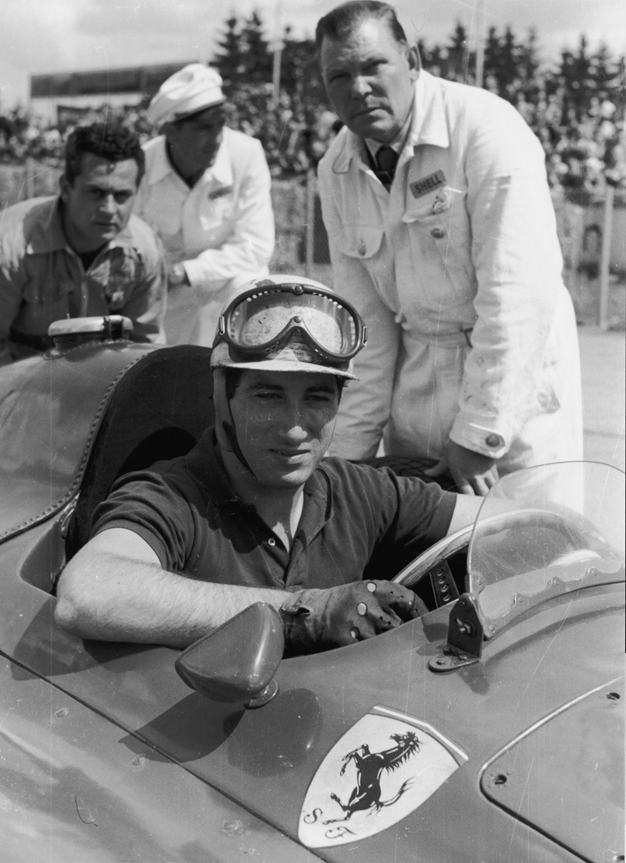

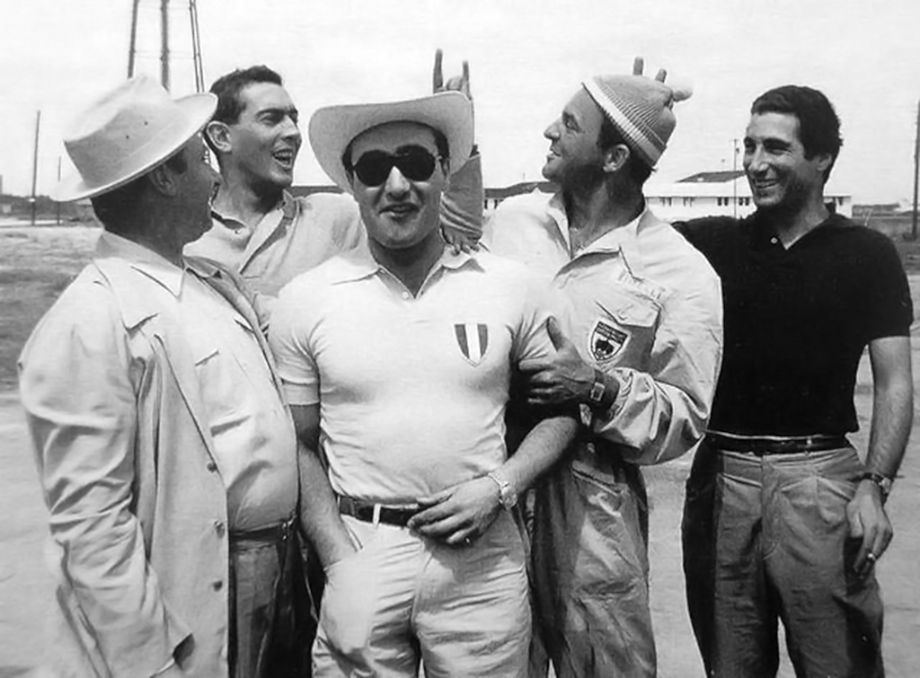

Juan Manuel Fangio, Mike Hawthorne, Alfonso de Portago, Eugenio Castellotti and Peter Collins.

These were the years in which Ferrari was laying the foundations of its sporting legend with world championship victories, from Alberto Ascari to Phil Hill passing through Juan Manuel Fangio and Mike Hawthorn.

Fangio, Peter Collins, Alfonso de Portago and Luigi Musso.

When the Cavallino garnered acclaim and glory in a pioneering era of racing, amid a nascent enthusiasm and sports dramas.

Tavoni, passionate about engines since birth and very close, even humanly, to Enzo Ferrari, continued to remain fond of the Cavallino even after leaving Maranello in the early 1960s: his frank and authentic character required direct choices and few compromises. His rich experience also includes the role of director of the Monza racetrack. In order not to lose the link with his beloved races.

Ferrari, goodbye to Romolo Tavoni: a piece of Ferrari that no longer exists. By Carlo Filippo Vardelli. 12 December 2020.

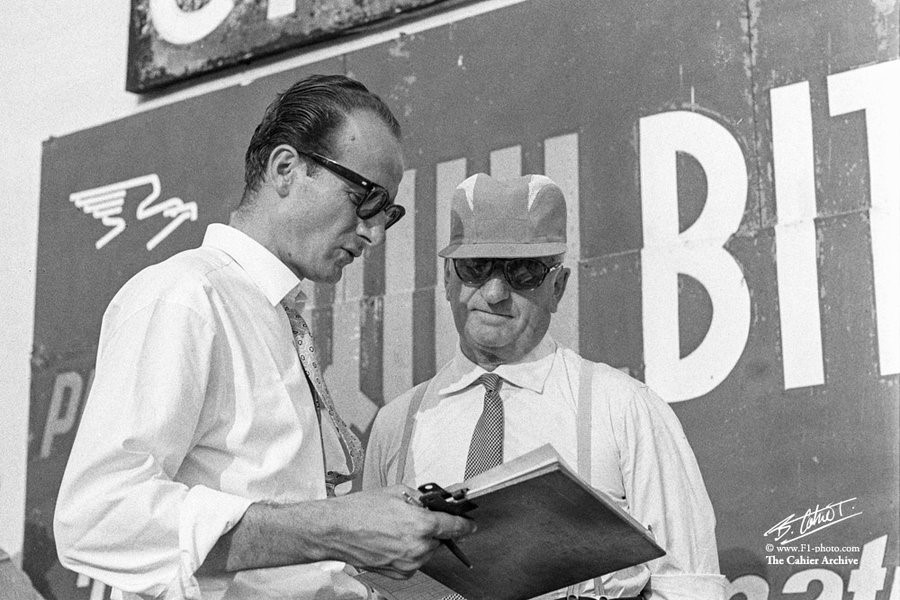

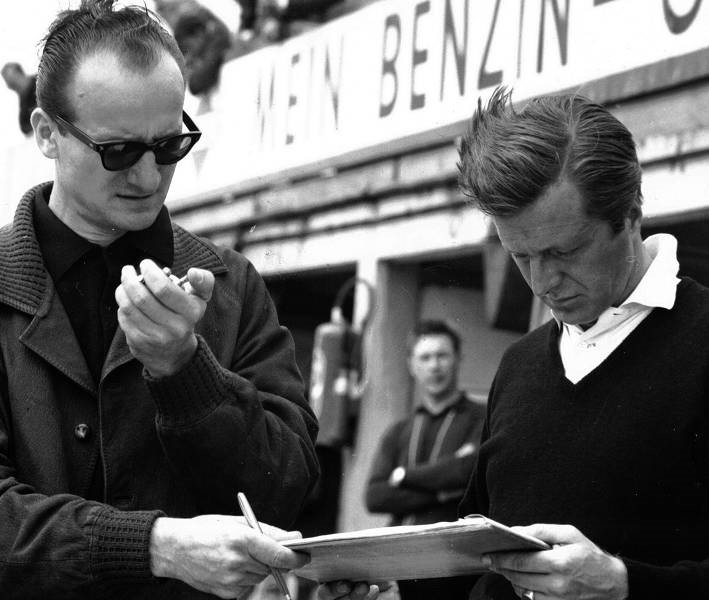

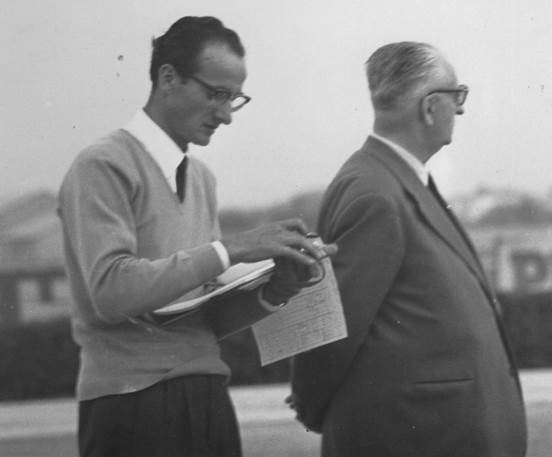

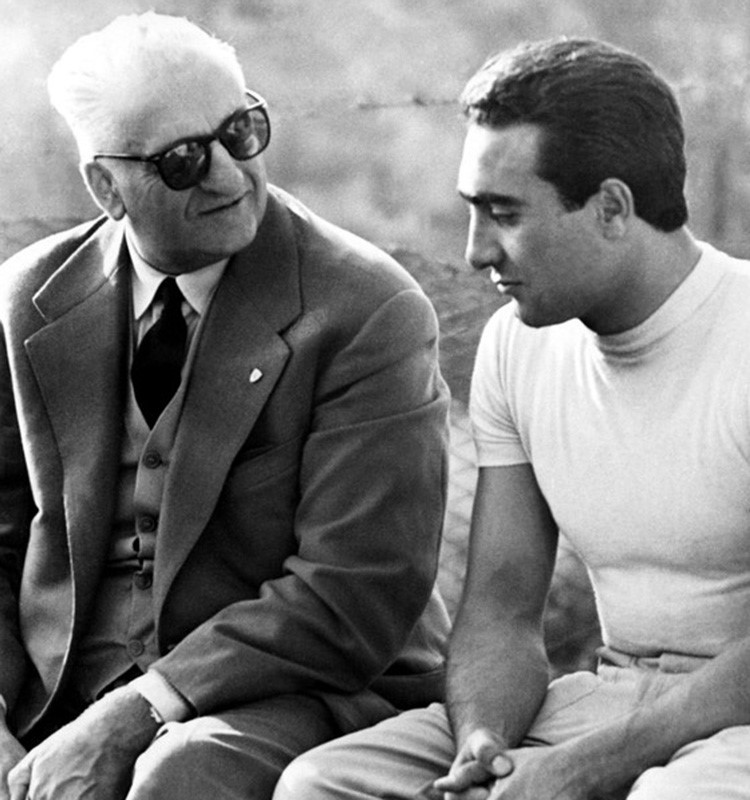

Romolo Tavoni together with Enzo Ferrari, right arm of the Drake in the 1950s. Credit Getty Images.

A key figure for Enzo Ferrari and a pillar of sporting activity in Italy: this was Romolo Tavoni, a key figure in the automotive world of our country. Right from the start he had entered into symbiosis with the area, developing a passion for engines. After an experience in Maserati, where he had been for seven years, in the 1950s he joined Ferrari earning the trust of Enzo who made him his secretary and, since 1957, also the sporting director. Then, in 1961, the quarrel and the subsequent expulsion from the Cavallino. This is how Enzo Ferrari spoke about it. "I lost my generals because they behaved like corporals and I can't keep corporals in the role of generals."

The story with Enzo Ferrari explained to Motorsport.

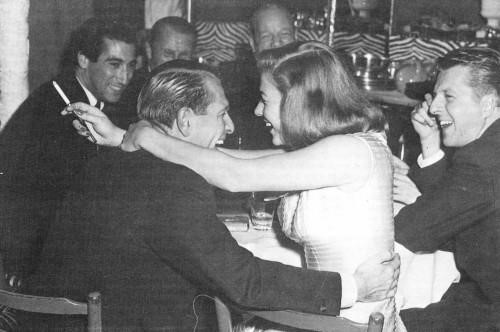

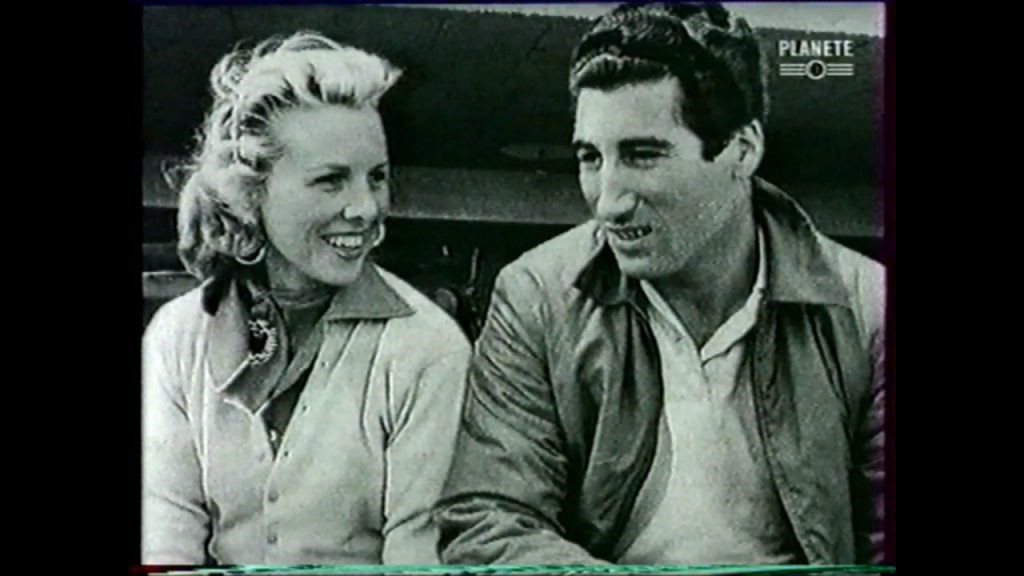

Romolo Tavoni and Laura Garello.

"Ferrari's wife wasn’t well already, yet she had made up her mind to follow the races in first person and the Commendatore had let her do it, but he couldn’t imagine how much trouble she would have created for the team due to her sudden illness and certain extravagant behaviors".

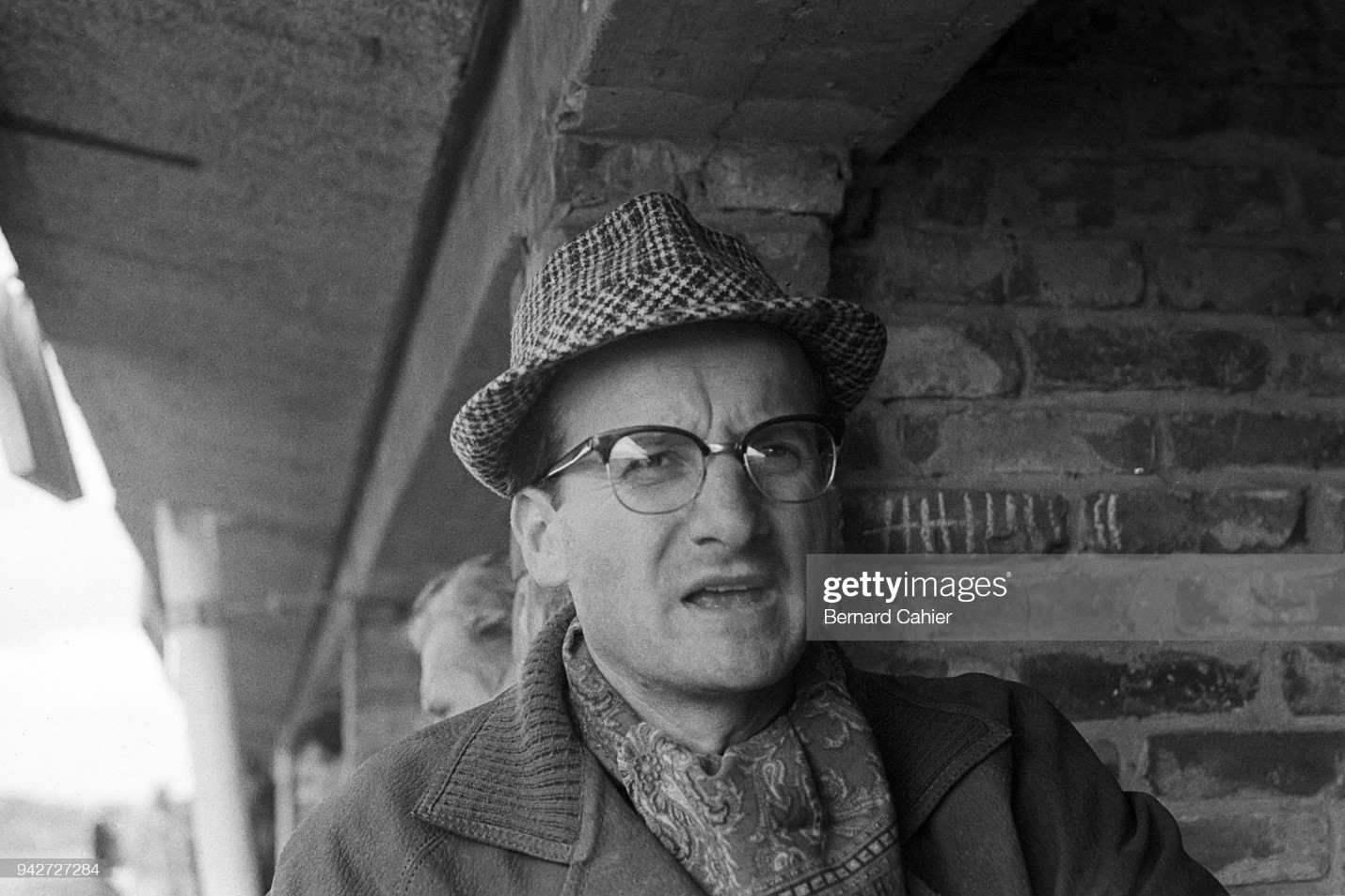

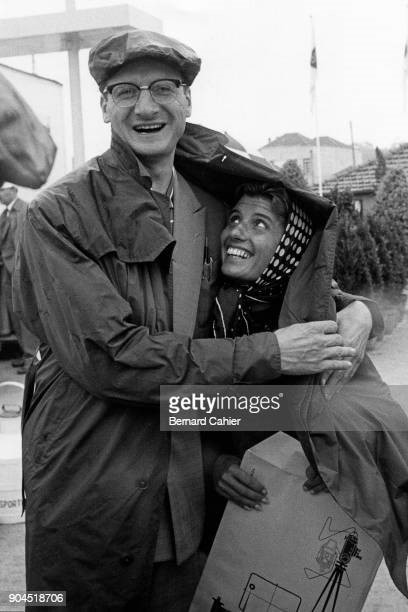

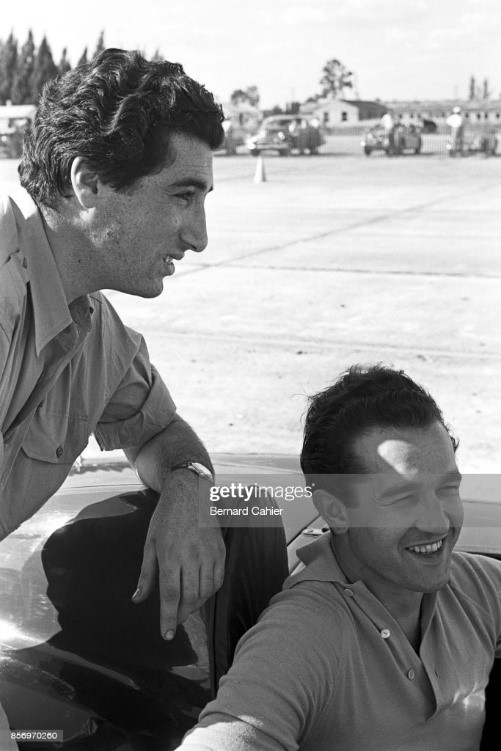

Romolo Tavoni passed away. The end of an epoch. I have fond memories of him, as I would see him every year in Monza on the occasion of the Grand Prix. A very nice man. Photo by Bernard Cahier / The Cahier Archive.

One of the eight managers received a slap in the face from Laura Garello in the Racing Department and the gesture did not go unnoticed. The eight wrote and signed a letter to Ferrari asking, at the end of the 1961 championship, that the lady no longer interferes in the activities of the Racing Department, because there had been episodes that had put the team leaders in a bad light with respect to employees.

Motorsport greets and remembers Romolo Tavoni. F1world@f1world.it.

"For three weeks, at the Tuesday meetings, Ferrari had turned up with his agenda and with our open letter in it. He had made it clear that he was aware of our intentions, but he never spoke about the subject. We were amazed. But, the following Tuesday, there was the big surprise: Valerio Stradi, who was my deputy, arrived and invited all eight of us to take the severance and leave Ferrari by noon. I asked the Commendatore to speak to him and he gave me a minute: I said that he had hired me as a second level type B worker and I had become a manager, but I was ready to go back to being a worker. Ferrari greatly appreciated the gesture, but did not change his mind".

Some "rebels" returned to Ferrari after a period of purge, not Tavoni: "13 years after that event, he asked me why I had not addressed that sensitive topic in person. Then I realized that we had made a big mistake, to save our face in front of the mechanics we had put at risk the charisma of the Chief in the Racing Department. And, in the end, he was right. Maybe the Scuderia would have won a few more races in that 1962, but we would have undermined the birth of a legend".

Time for a final farewell to Romolo Tavoni, a man who contributed a lot to the early days of the Scuderia.

After his expulsion from Maranello, Tavoni landed at the Monza racetrack as manager and director of sporting activities. He created a training category for young drivers and Monza was to become the permanent training ground not only for the drivers but for the whole world that gravitated around racing: builders, trainers, mechanics but also race judges, marshals and so on. The Trofeo Cadetti was born in 1965 with the F.875, derived from the Fiat 500 engine. In the 1970s, Formula Monza saw over 100 cars on the track. And, in those single-seaters, talents such as Alboreto and Ivan Capelli were formed.

Romolo Tavoni, a chat while walking through time. Published by Auto Motor Fargio on September 9, 2015.

You should never forget your friends, especially if you have little opportunity to see them.

And, if to define you "friend" is not just any guy but a piece of racing history, the word has an even more important value.

Romolo Tavoni is, above all, a man with whom it is always a pleasure to have a good chat. Especially after my experience in Le Mans as a tire control inspector in the pits.

Romolo Tavoni during the years of his activity in Ferrari. Copyright unknown.

So Romolo, how are you? We haven't heard from each other for a long time!

"Hi Claudio, don't worry, you will always remain a friend and that's no problem! I'm pretty well”.

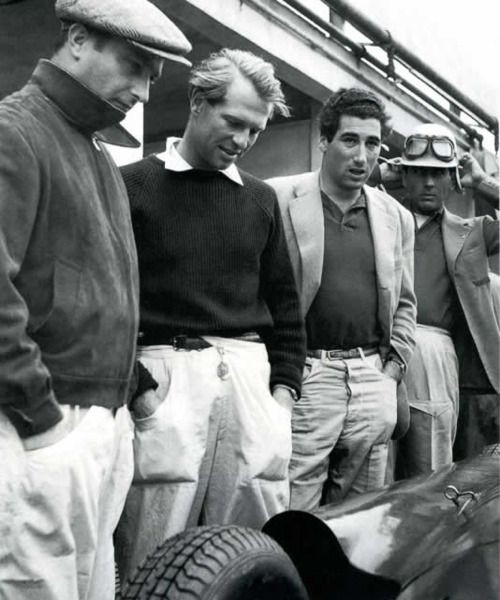

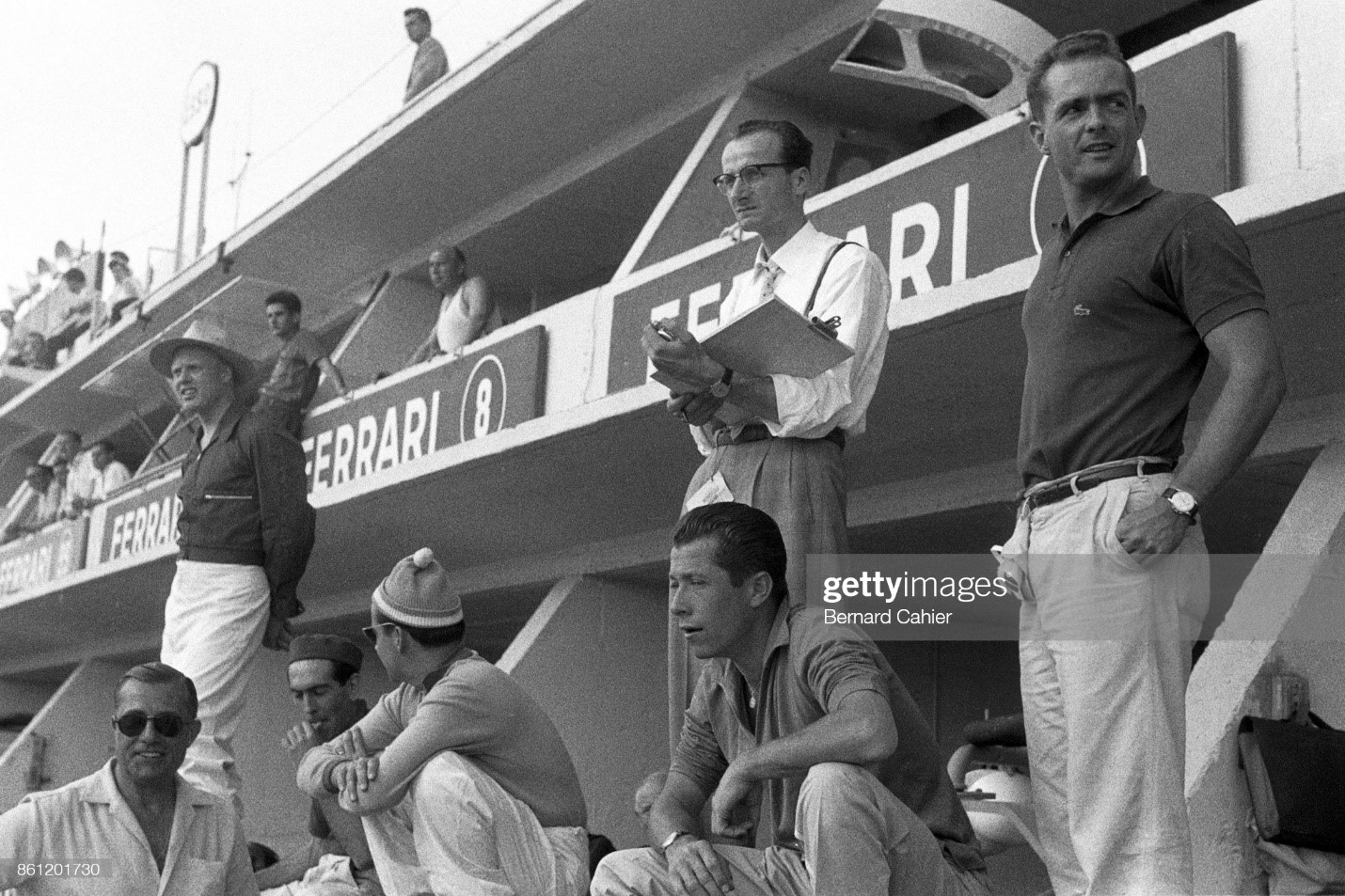

Phil Hill, Romolo Tavoni, Olivier Gendebien, 24 Hours of Le Mans, Le Mans, 23 June 1957. Phil Hill with Ferrari team manager Romolo Tavoni and teammate Olivier Gendebien. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

You’ve been to Le Mans? Good boy! Great competition, what a tradition and what an organization! They are really good and you did well to have this experience, it is very formative for you!

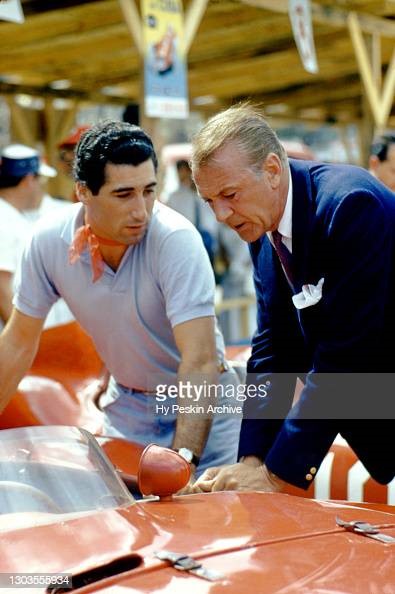

Romolo Tavoni with Phil Hill at the 24 Hours of Le Mans on 21 June 1959.

Le Mans also gave birth to other historic races, starting with the 1000 km of Monza just in preparation for the French classic. In 1965, in the first year, we paid 1000 dollars for each official participating car but, from the second year, it was the firms that asked us to participate and the public beat that of the Italian Formula 1 Grand Prix!

Romolo Tavoni and Phil Hill in Monza in 1958.

Phil Hill, Romolo Tavoni and Denise McLuggage, an American auto racing driver, in Monza in 1958.

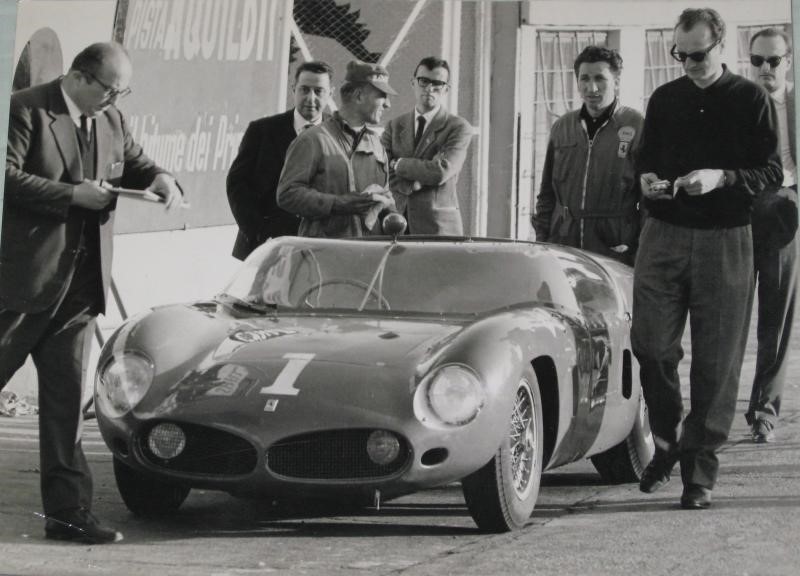

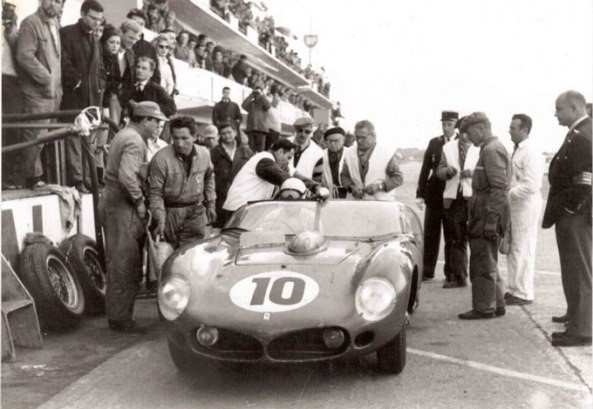

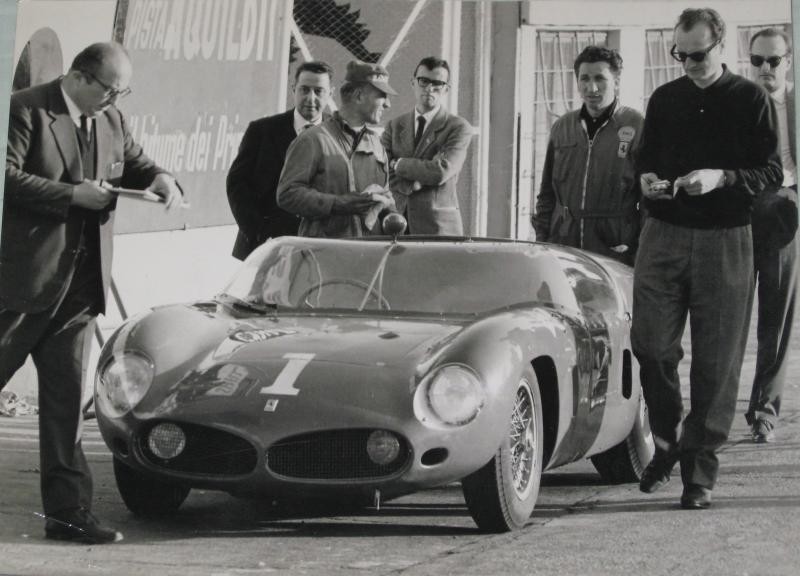

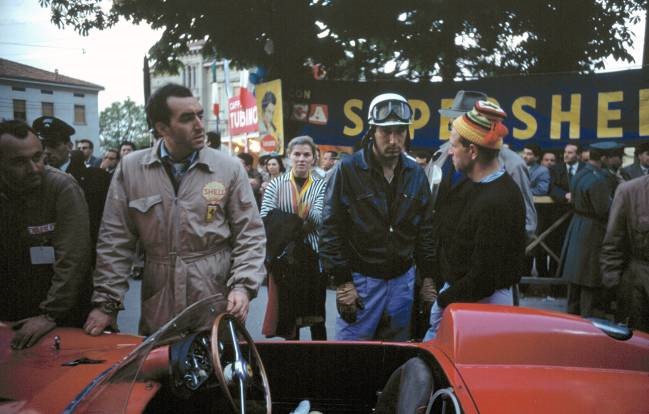

Testing Ferrari 246 at Monza in 1961, possibly 14 March, when it was tested with Richie Ginther (he may not be in this picture). It is the 1961 Ferrari 246/196 SP s/n 0790. People are from left: Carlo Chiti (with papers), Adelmo Marchetti (engineering hat), Ener Vecchi (if he is here, it may be the one with Shell mark on his working habit), Romolo Tavoni (dark sweater, glasses, radio to the right in front).

1961 Italian Grand Prix, Romolo Tavoni and Richie Ginther's Ferrari.

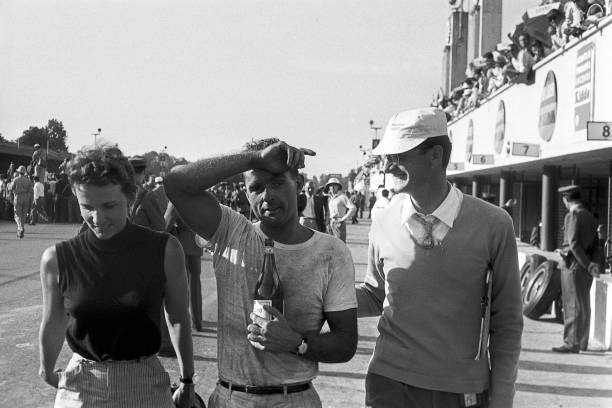

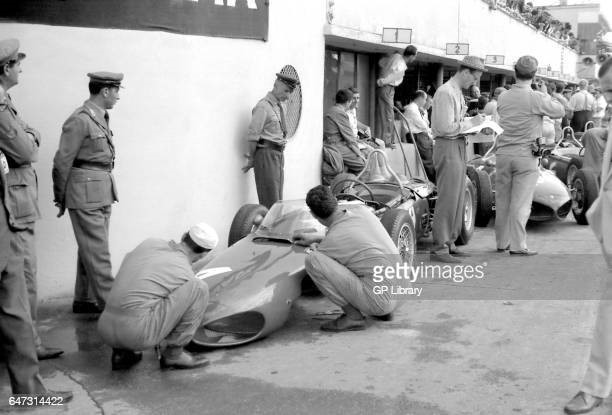

Romolo Tavoni in the crowded Ferrari pits at the Italian Grand Prix, 1961. Photo by GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Monza was an important test bench: by adding a high-speed ring to the road, conditions similar to those found on the Hunaudières straight were proposed and it was a remarkable test. Then other races of similar lengths were born on the major European circuits."

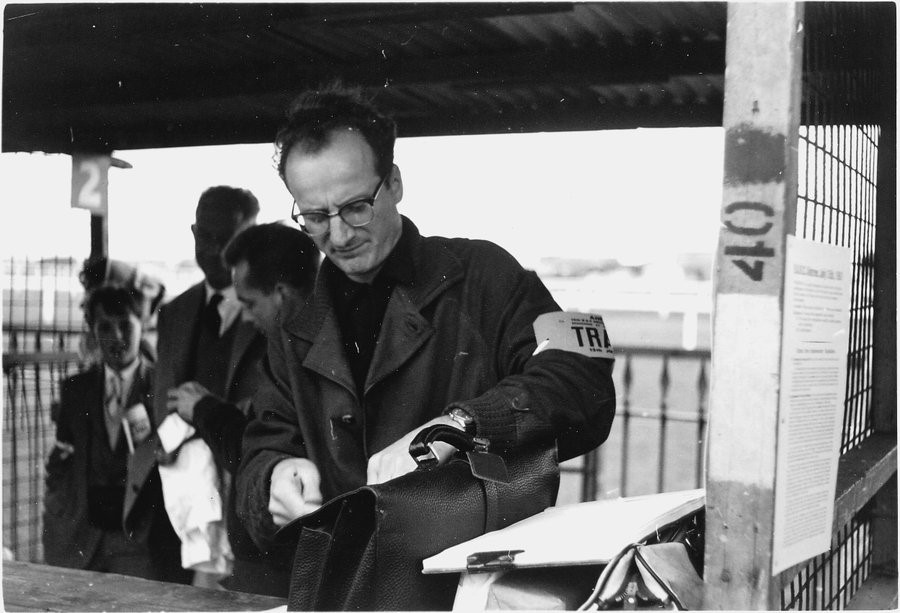

Romolo Tavoni at 1961 Grand Prix of The Netherlands in Zandvoort.

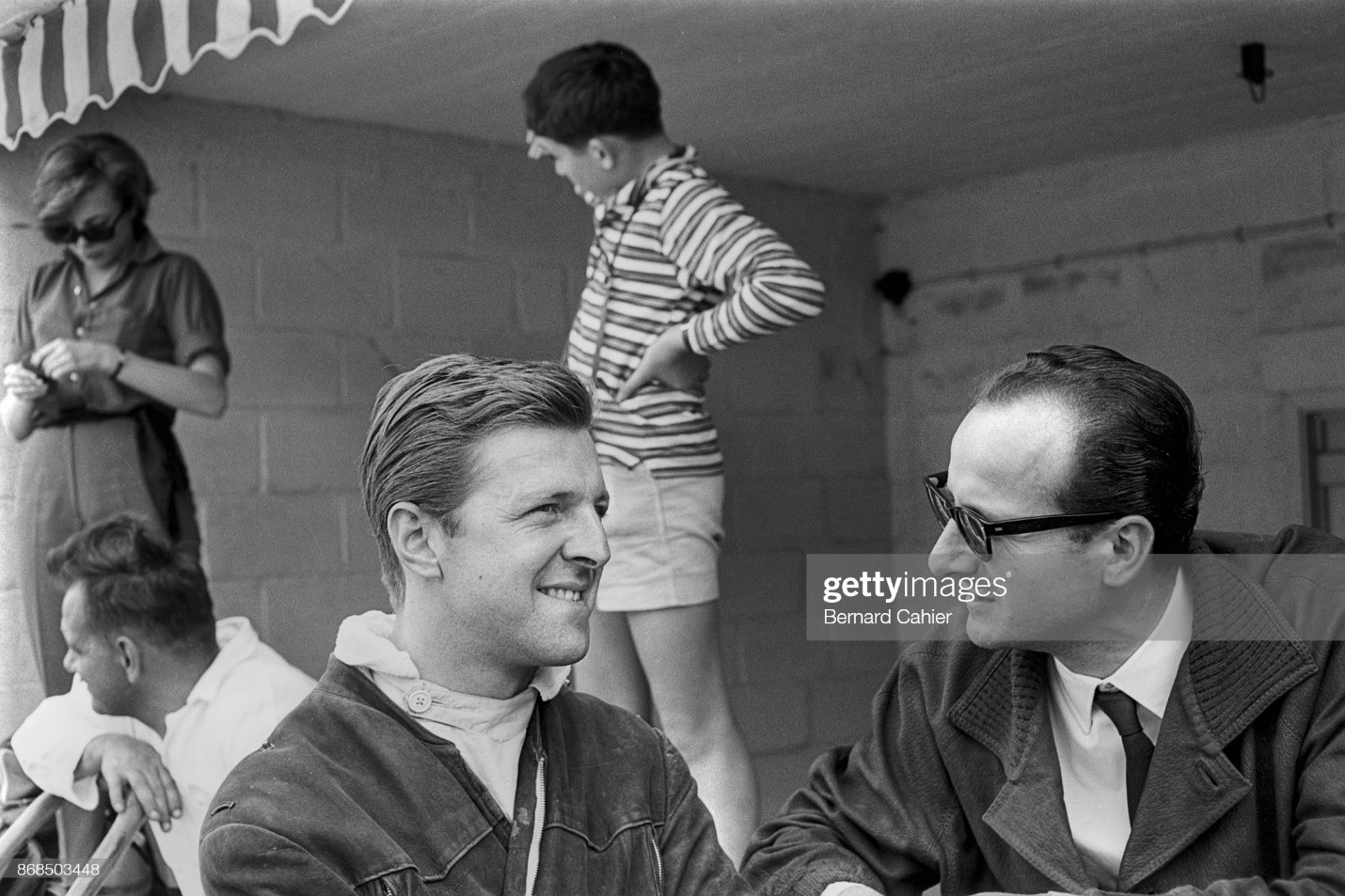

Romolo Tavoni with Wolfgang von Trips, Ferrari 156 Sharknose, Grand Prix of Belgium 1961.

Count von Trips and Romolo Tavoni at the 1961 French Grand Prix.

Tavoni with von Trips at the 1961 German Grand Prix.

The 156 F1 Ferraris in the pits, in the triumphant vintage year of 1961.

I had other questions in mind but it's a pleasure to let Romolo tell and, letting myself be carried away, I decide to indulge him ...

«You know Claudio, for us Le Mans was a very important race, Ferrari built its legend there when, in the early 1950s, sports customers bought the cars to show up for the 24 Hours and the company provided support and assistance. Then, as a team, we began to show up with contingents limited to twelve mechanics (three per car) who worked almost non-stop for tests and races, while I counted the laps with someone to replace me for when there was an urgent physiological need. Our tests were then limited to two days on the Monza circuit to simulate the conditions of high speed, leaving the gearbox without replacing the oil and then checking the parts in Maranello after the tests. And then we left."

Did you only have 12 mechanics?

"Yes. And we chose them carefully. At least 70% of the racing team members applied for Le Mans but we only chose those who showed more physical resistance, sacrificing other very good guys. But resistance was essential. Then, as soon as Le Mans was over, the following week the Belgian Grand Prix was waiting for us in Spa, so some mechanics with me went directly to the Ardennes while others went up from Maranello with the truck that brought the cars for the race. Then they were extraordinary in the 24-hours: they even went so far as to manufacture made-to-measure tools to carry out repairs during stops in the shortest possible time".

A Ferrari 246 SP stopped in the pits during the 1961 24 Hours of Le Mans. Copyright unknown.

And the drivers?

"At the time there were only two of them per car, it was really demanding for them. They worked several shifts and, when they weren't driving, they rested on a cot in the pits with earplugs, now they have plenty of physiotherapists to follow them. But they were very good at managing themselves and, knowing their characteristics and limits, they agreed on how to manage the race. For instance, Paul Frère asked Gendebien to do more consecutive night shifts because he knew that his vision at night was not perfect and then relieve him at dawn when he would have raced rested and with the help of a pair of dark glasses so as not to be dazzled by the rising sun".

And so they won the 24 hours in 1960… And what can you tell me about logistics?

"I made an agreement with the hotel that hosted us: they brought everyone on the track a meal for dinner and lunch and coffee to keep us awake".

Well, certainly a big difference with today's hospitality ...

"Certain constructions that are also seen in Formula 1, which need five or six trucks to transport them for the use and consumption of guests and sponsors, are only exaggerations and waste!"

Absolutely okay but, at Le Mans, the official teams also build real buildings in the back of the pits, with rooms for the technicians and rooms reserved for rest and massages for the drivers ...

«This is a great thing, also for safety, because a rested driver runs less risk. In addition to the fact that there are now three pilots, in two it’s really exhausting."

However, I must say that, living it in the pits, I found the same sensations that you transmit to me when I see the faces of the tired and sleepy mechanics and technicians ...

"I'm glad you were able to experience all this Claudio, it's very nice that the spirit of the race remains and you lived it in the right way."

I also found the spirit you are telling me about your Ferrari team among the men of AF Corse who, with great organization and inventiveness, won last year in the GTs, touching an encore this year clashing with more financially gifted giants. And I was also able to appreciate the professional, organizational and sporting skills of the German teams …

"I am very happy with the AF Corse victories! And then the Germans, ... well, they have always been a model of organization and resources available. Porsche has never participated in Le Mans for an extra role. To tell you how much they cared about the organization, our mechanics showed up for tests with their overalls, which were washed and returned on Saturday morning. And those remained. The Germans showed up every morning with new overalls … And they are very sporty. They never denied us help when we lacked something material to put us in a position to compete, even if we were rivals on the track. They made it a point of honor. True gentlemen!"

Well, you can't buy sportsmanship and refinement … And did the Commendator Ferrari like Le Mans?

«Sure and a lot. He knew that for his company a victory in the 24-hour of Le Mans was very important."

After my experience, I can say that I have found a lot of what you are telling me also in the current race, especially in the last two years, in which it has been uncertain and fought like a true endurance. But tell me Romolo, do you like the new technical regulation that sees the hybrid protagonist also in the WEC?

«Yes, very much, I think the right direction has been taken. In Formula 1, for example, a regulation has been made that the manufacturers have chosen but I do not understand the reactions of Montezemolo last year with the entry into force of these rules. If he really didn't like the regulation, why didn't he really threaten to quit Formula 1 and move the Gestione Sportiva to the Le Mans project instead of publicly criticizing it? Ferrari would have done so ... "

Romolo, as always a chat with you would be endless and it brought me too many ideas! I'll ask you one last question: do you think we can still tell something new about the Ferrari character?

"Yes, Enzo Ferrari is a character that is perpetuated and renewed over time."

So would you like to have a chat on this topic soon?

"Willingly! For me it is a pleasure to be able to talk about these things, it always makes me feel young!"

But personally I don't think there is a need for this, a friend like Romolo, who has so much to convey and communicate, never gets old. See you soon!

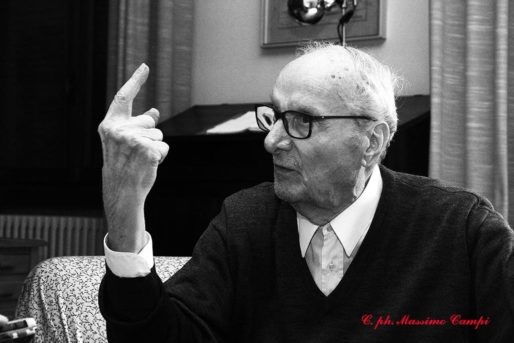

An always combative Romolo Tavoni. Copyright unknown.

Enzo's right-hand man. By Chris Nixon. July 7th 2014.

In the mid-1950s, Romolo Tavoni was faced with a choice: he could work alongside a tyrannical Enzo Ferrari… or get the sack. Fifty years on, he tells Chris Nixon he made the right decision.

In January 1950, a young employee was called in to see the manager of the Credito Italiano bank in Modena. The bank had a new client and, keen to help out in any way, had offered the man’s services to the firm for the first two months of the relationship. The client’s name was Enzo Ferrari and the manager had just given him a loan to build a new factory in a small town in northern Italy: Maranello. During the drive to Ferrari’s existing factory at via Trento e Trieste in Modena, the bank’s employee thought nervously about the job ahead. “I did not want to work for him,” he admits nearly 50 years on. “I’d heard that he had a new secretary every two or three months and worked from eight in the morning until ten at night. We went into his office and he asked where I worked before joining the bank.

“I told him I had worked as a bookkeeper for Maserati, hoping that he would say ‘go away!’, because in Modena if you worked for Maserati you never worked for Ferrari. But he said, ‘fine, I think you are the secretary for me, but why only two months — why not 10 years?’ That was my introduction to Mr. Ferrari.”

We are sitting in Romolo Tavoni’s office at the Monza Autodromo, where he has worked since 1972. A big man, well over six feet tall, he has a deep, basso profundo voice and a laugh that is seldom more than a sentence away.

“A week after our meeting I joined him as his secretary, first at Auto Avio Costruzioni, because he was then building machine tools and then at Scuderia Ferrari. The first day I was at the Modena office he gave me some letters to type and asked, ‘when do you take your lunch?’

‘Twelve o’clock, Mr. Ferrari.’

‘No, no, half-past one! I work until one o’clock and then I go to Maranello and sometimes you will come with me and sometimes you will work here.’

“At five o’clock most people left for the day, but Mr. Ferrari told me he would phone me before I could leave: at seven he phoned to say he would be in Modena at eight and I was to wait. When he arrived, he asked me to type and post some letters. When I got home, my father, mother and sister were waiting up for me and said, ‘why are you home at 11 o’clock?’ I told them I was working for Mr. Ferrari, but they didn’t believe me!

“At Maranello Ferrari talked with everyone – not just the department heads, with whom he was very tough. But I soon learned that he was not dangerous when he was talking tough, it was just his way of expressing himself. When he sat round the table with them he talked very softly and it was in these moments that I realised he made his decisions.

“When he posed a question he wanted a reply very quickly and he started with the little man, not the big chief of department and that was a problem. Although Ferrari regarded them highly he always told them, ‘if the people in your department don’t work properly it is your fault.’ He always took the side of the workers and so they worked for him with a grande passione. When he stopped making machine tools to concentrate on cars the factory was deeply in debt to the banks, but his workers were paid every month without fail. Perhaps not the suppliers, but the workers always…”

Generous to a fault with his blue-collar staff, Ferrari, it seems was less charitable when it came to the young Tavoni’s own job prospects. “My two months went very fast and at the end he asked, ‘have you received your money?’ I said, `yes…’ and was about to thank him when he said, ‘stop! I am speaking, you listen. I have spoken with the bank manager and told him you are right for me and I have asked him not to take you back.” Bravely, Tavoni told Ferrari that he was keen to return to his old job. “He was astounded. ‘Why? Ferrari is not as good as the bank?’ I told him that I was tired of staying until ten at night. At the bank I started at nine, at eleven took a cappuccino, at twelve had lunch and at six it was time to go home. ‘Are you stupid?’, said Mr. Ferrari.”

Tavoni roars with laughter at the memory of his boss’s incredulity. ‘Maybe you get a job in a bar or a restaurant? At Ferrari this is work. If you’d like to stay you can, otherwise I will see to it that there is no place for you at the bank.’ He paid me the same money as I was getting at the bank, but I stayed and I am glad, because it was fantastic.”

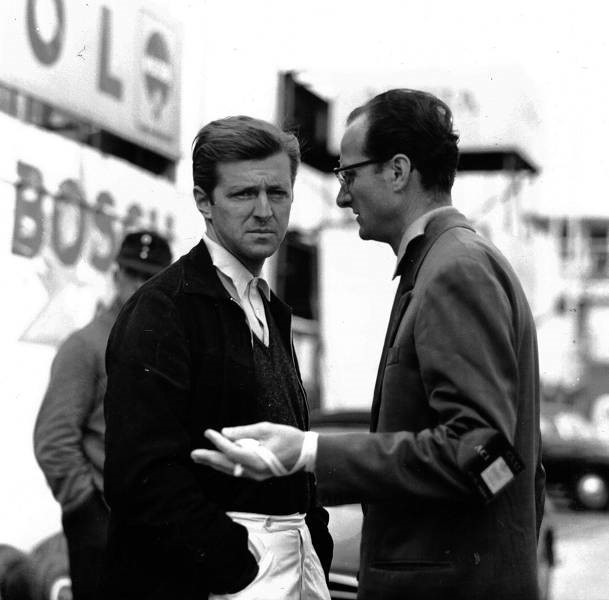

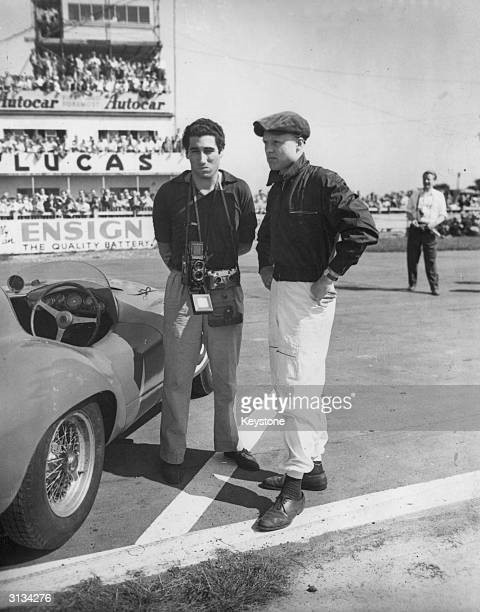

Mike Hawthorn and Romolo Tavoni in Silverstone.

Tavoni recalls how, as the racing side of the empire grew, Mike Hawthorn soon came to Ferrari’s attention. “In 1952 he wrote to Tony Vandervell, asking him to sell some of his sportscars in England. Mr. Vandervell told him, ‘I race the Thinwall Special Ferrari, I don’t sell cars. But I have a driver for you who is very fast, young and intelligent.”

Hawthorn was to become Tavoni’s favourite driver of all. “He was a great driver, very intelligent and a gentleman. Also very direct. Mr. Ferrari once said to him, ‘why you have difficulty in this race?’ Mike said, ‘the gearbox is bad, it was impossible for me to change gear properly.’

“Ferrari was furious. ‘You say my gearbox is no good? My gearbox is the best and if you say it is no good a second time you can leave!’

“‘Goodbye!’ said Mike and he left. Ferrari quickly called him back. He liked a driver who spoke for himself. If a driver just complained about his car he got nowhere with Ferrari, but after a race Mike would say, Romolo, the brakes were no good’ and when we were back at Maranello he would tell Ferrari, ‘the car was fantastic, but we had some difficulties with the brakes. Maybe we should do some testing.’ Ferrari liked this and he would stay night and day in the Competitions Department to try and put things right. He always built the best car possible and the drivers admired him because first he was a driver himself, then a manager and then the owner. He was a fantastic man.”

By the mid-1950s financial troubles forced Gianni Lancia to sell his company and abandon racing. In a remarkable deal all the Grand Prix cars, the spares and designer Vittorio Jano were handed over to Scuderia Ferrari, which had been having a terrible season with Aurelio Lampredi’s Super Squalos.

Lampredi’s days at the Scuderia were already numbered, for his promised two-cylinder GP engine was showing no promise at all. Now, with the Lancias and their designer under his roof, Ferrari had no further need of Lampredi, so he fired him. He did need Juan Manuel Fangio, however. At the end of 1955 Mercedes-Benz withdrew from racing, leaving their double World Champion without a drive. He joined Ferrari for 1956 and, although he was to retain his championship with the Lancia-Ferraris, it was not a happy association.

As far as Juan Manuel was concerned, the reason was that Ferrari refused to nominate him as his number one driver, despite the fact that he was now three-times World Champion. From Enzo Ferrari’s point of view, however, the problem with Fangio was one of money.

“Usually, Mr. Ferrari split the prize money 50-50 with his drivers. At Mercedes Fangio had been given 50 per cent and a big salary and he demanded the same at Ferrari. Mr. Ferrari liked Fangio the driver, but not Fangio the man, saying, ‘I provide the cars, you provide the driving skills, so I think 50-50 is correct.’ When Fangio insisted on a salary also, Ferrari felt that he was breaking with tradition.

“He won the title for Ferrari and then moved to Maserati for ’57 where Mr. Orsi was happy to pay his demands. He won again, but Ferrari retorted, ‘fine, Orsi has won the Championship, but I have money in my pocket.”

All this time Nello Ugolini had been the Scuderia’s team manager but, at the end of 1956, he caused a sensation in Modena by leaving Ferrari… for Maserati. This was to bring about a great change in Romolo Tavoni’s life.

Ugolini was replaced by Eraldo Sculati, but very soon a failure to inform Ferrari – who hadn’t attended a race since 1934 – of the result of the 1957 Argentinian GP was to cost him his job.

“On the Sunday we waited in his office till 11 pm for the phone call from Mr. Sculati, but it never came. We went to the Real Fini restaurant in Modena and quietly Ferrari murmured, ‘I have to change.’

“When Sculati came back, Mr. Ferrari was very nice to him but didn’t ask about the race. He simply took him to a restaurant for lunch and told him he was fired! A few weeks later Ferrari called me: `Mr. Amarotti, my friend and race technician, needs you as team manager. You have all the contact with the race organisers and drivers and I know you will do your best for me.”

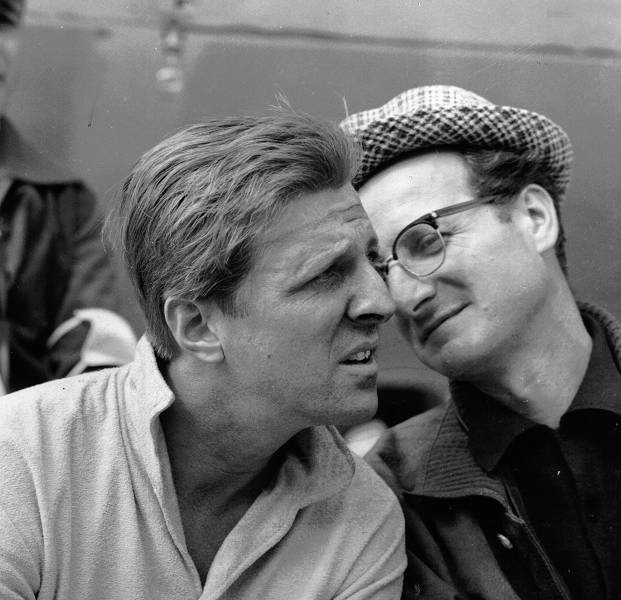

Brooks and Tavoni.

Tavoni had a brutal introduction to his new job. Before he had even been to a race Eugenio Castellotti died while testing at Modena Autodromo and then Fon de Portago and several spectators were killed in the Mille Miglia. Badly shaken by these tragedies, Romolo asked if he could return to his old job in the factory, but Ferrari insisted that he stay on. All went well until the French GP at Reims in 1958, where Hawthorn won but Luigi Musso was killed.

Romolo Tavoni with Maria Teresa de Filippis at the 1958 Belgium Grand Prix.

Maria Teresa de Filippis played three Formula 1 GP's.

“The magazine “La Civilta’ Cattolica” criticised publications which wrote about the Ferrari victory,” recalls Tavoni, “saying that the factory was nothing because it was built on dead men. That was terrible for Mr. Ferrari and he didn’t know whether to continue racing. He talked with a priest, who told him, ‘God gives each of us a way – sometimes it is difficult, sometimes it is easy. You have chosen the difficult way – you must have the courage to follow it.’

“A few weeks later we lost Peter Collins at the Nurburgring. Mr. Ferrari was very fond of Peter because in 1956 he was a good friend to his dying son, Dino. After Peter was killed Ferrari said, ‘we must stop Grand Prix racing now. We will continue with GT and think about the future.’

“But Mike Hawthorn told Mr. Ferrari, ‘I am responsible for myself and I know the risks. If I don’t have a Ferrari I will race another car, but I want to race a Ferrari for the rest of the season.’

So the team carried on, Hawthorn finishing second in Portugal, at Monza and in Casablanca and in doing so taking the championship. Ferrari won the drivers’ title again in 1961, with the beautiful sharknose 156 cars.

Romolo Tavoni, Wolfgang von Trips, Richie Ginther and Giotto Bizzarrini.

As usual Ferrari refused to nominate a number one driver and so team-mates Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips fought for the title until the Italian GP, where tragedy struck once again.

Wolfgang von Trips and Romolo Tavoni.

On the second lap von Trips tangled with the Lotus of Jim Clark and both cars crashed out of the race, but it was the Ferrari that careered into some spectators lining the track. Eleven died, as did von Trips. Phil Hill won the championship, but in the most appalling circumstances.

Count von Trips and Romolo Tavoni.

Tavoni liked von Trips enormously and was understandably upset when Ferrari ordered him not to attend the German’s funeral. “He insisted that I stay in Modena and he sent his wife Laura and Franco Gozzi. I was very unhappy about this and uncertain about my position as team manager.”

The decision was made for him a month later when, in an extraordinary turn of events, it was announced that eight Ferrari executives – including Tavoni – had walked out. No reason was given then or since, but there were rumours that it was all due to interference in company affairs by Ferrari’s wife. For the first time Tavoni now confirms this. Laura Ferrari had long been a major shareholder in Ferrari Automobili. In 1960, she began going to races with the Scuderia and, it seems, interfering with the work of Ferrari’s executives.

“She was criticising us to Mr. Ferrari,” says Tavoni “and, in October, we had big difficulty after her return from the funeral in Germany. We had a big discussion and we were all so unhappy that we wrote a letter to Mr. Ferrari asking that Mrs. Ferrari should stay out of the factory. He was very offended and at our weekly meeting he said; `if this is how you feel, there is the door, here is your money – OUT!’ It was typical Ferrari, who found it impossible to admit that we were right.”

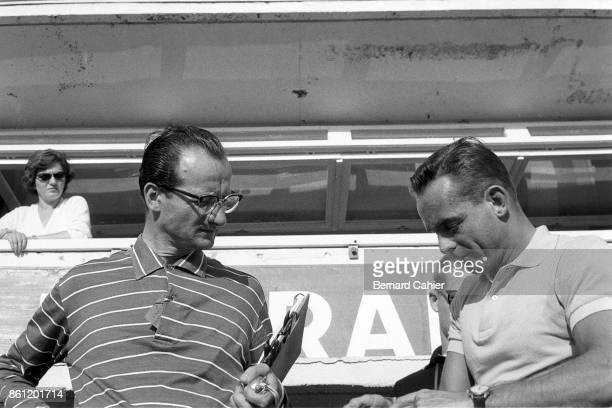

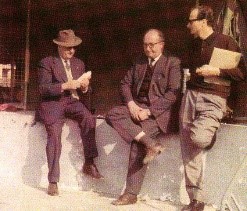

Enzo Ferrari, Carlo Chiti and Romolo Tavoni in Monza in 1961.

Carlo Chiti and Romolo Tavoni.

Romolo Tavoni and Carlo Chiti.

Carlo Chiti and Romolo Tavoni.

Carlo Chiti and Romolo Tavoni.

Tavoni and Chiti were quickly snapped up by a consortium of Italian businessmen who formed the ATS F1 team. This was a disaster and fell apart in September, 1963. The next year Tavoni was asked to set up a 1000 Km sportscar race at Monza and return international endurance racing to Italy, following the demise of the Mille Miglia.

Romolo Tavoni around the age of 35 with Enzo Ferrari and his notebook at the ready. Photo by Graham Gauld.

In the next few years Enzo Ferrari twice asked Romolo to return to Maranello as team manager, but he declined. Despite their unhappy parting in 1961 the two remained good friends and would have lunch whenever Tavoni was in Modena, until Ferrari’s death in 1988. Since then, many harsh words have been written about Enzo Ferrari, but Tavoni holds him in the highest regard.

“For me, Ferrari was the owner, the boss and a fantastic man in the sport and around the factory. He was also a teacher and a very strong father figure. When my first daughter was born he gave me three times my monthly salary for her. At other times he could be infuriating because he was so changeable.

“When he asked me to ‘rejoin the family’ it was tempting, but I had a very good job at Monza.

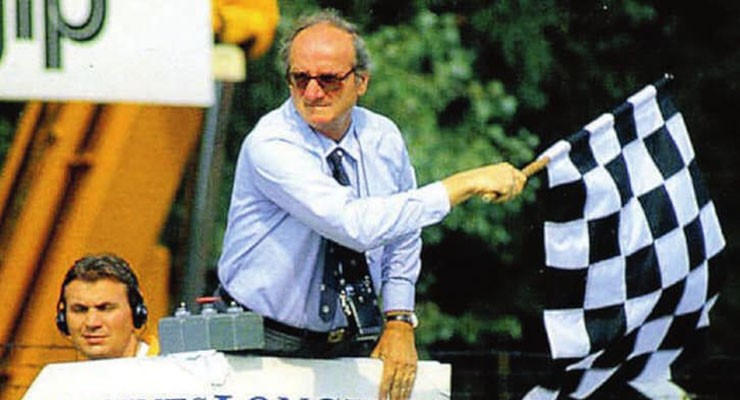

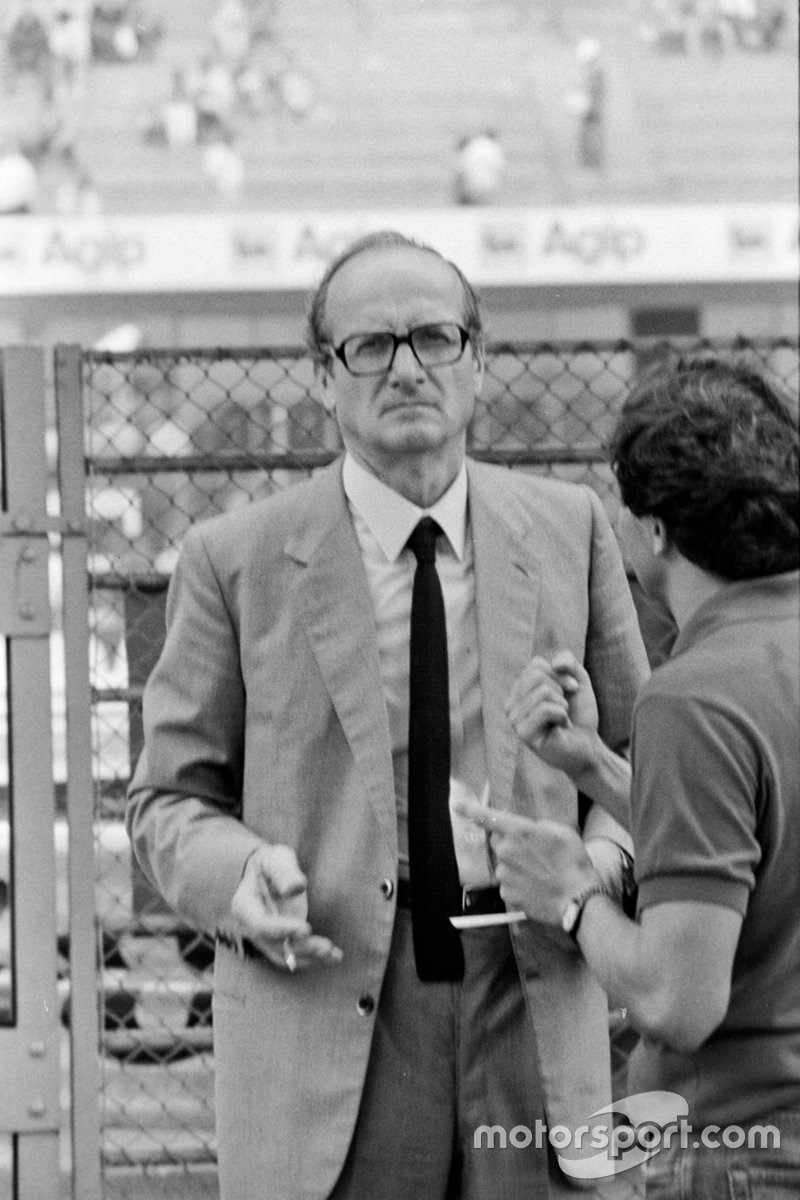

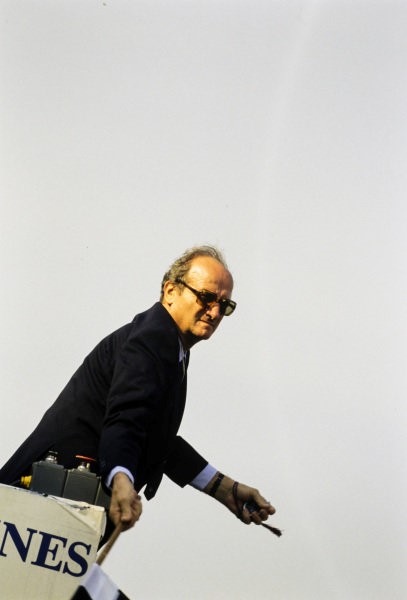

Romolo Tavoni at the 1990 Italian GP.

In 1982 I took charge of all activity at the track, the Italian GP, everything.

It was a very important job and very satisfying for me.” Romolo Tavoni is now 71 and in robust health and humour. He retired in 1992 and is happy to spend time with his grandchildren. “I have three daughters and three granddaughters. With my mother, my sister and her daughter I am surrounded by nine women – is terrible!”

Museo Nicolis, Mostra Ascari, Romolo Tavoni and Mauro Forghieri. Photo A. Rosa.

He roars with laughter again. But he cannot resist the lure of Monza and, since 1993, he has been assistant manager of the Autodromo, working two days a week there. The Manager is one Enrico Ferrari and so, by a nice twist of fate, Tavoni’s career has come full circle, ending as it began, working for Mr. Ferrari.

Romolo Tavoni and de Portago's tea. Published on May 11th, 2017 by Massimo Campi.

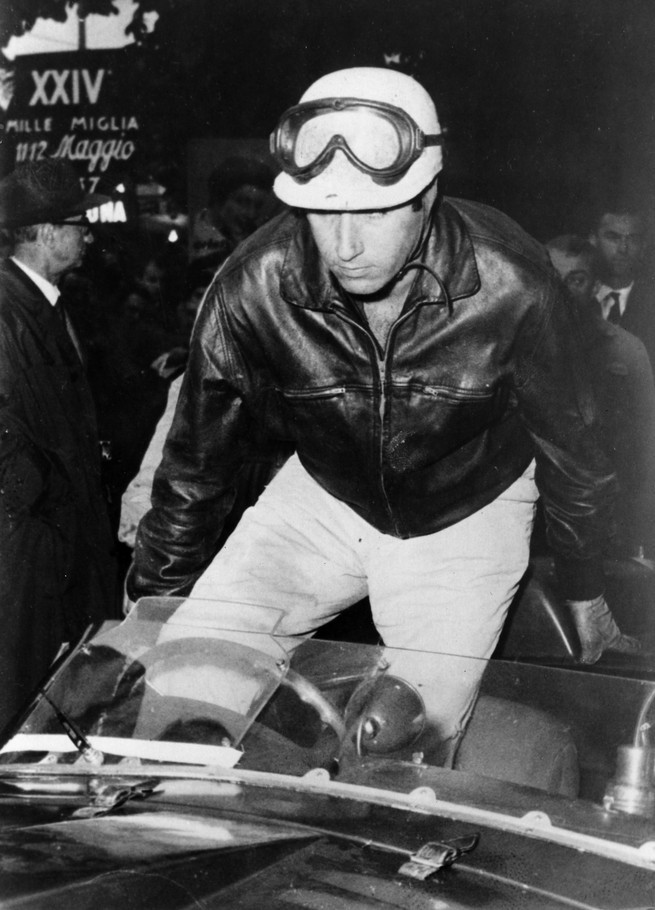

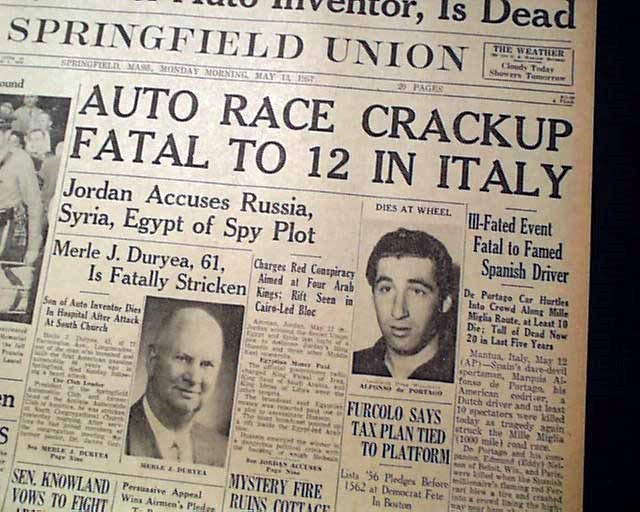

May 12, 1957 is the great day of the Mille Miglia, but the drama of Alfonso de Portago will put an end to the most famous road marathon.

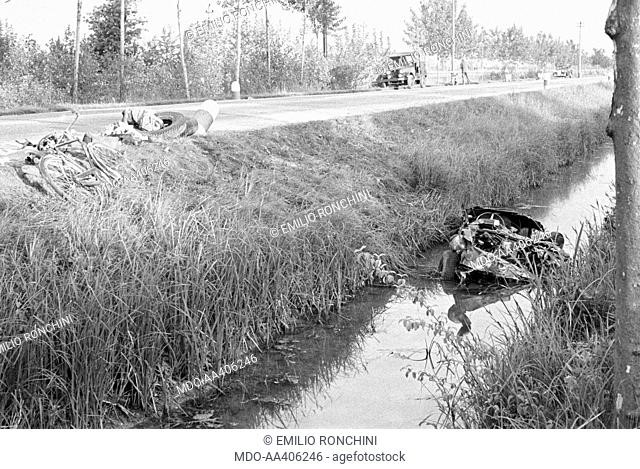

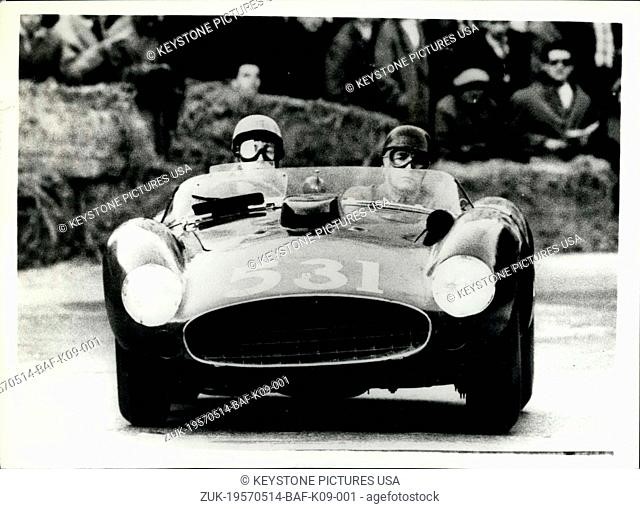

Mille Miglia, a race that has always aroused the popular imagination, a race that has also experienced great dramas and it was a drama that decreed its end. On May 12, 1957, sixty springs ago, de Portago's Ferrari 335S n° 531 went off the road, sowing death among the spectators. Everything happened in view of the town of Guidizzolo, in Corte Colomba (municipality of Cavriana), when the sudden burst of a tire caused the car of Alfonso de Portago and Edmund Nelson to skid. The car, having ended up in the ditch on the right, came out of it jumping the entire carriageway and crashing on the left edge where many spectators were thronged.

The accident resulted in the death of the occupants of the car and nine spectators, including five children, as well as numerous injuries. It was the last portion of the race, that led to the Brescia finish line and the cars in the race reached speeds of over 250 km/h in that point.

Romolo Tavoni was Ferrari's Sporting Director, let's relive the drama through his words from an interview made a few years ago.

“The marquis de Portago was the victim of a real accident, an accident “accident”. On the Futa he had hit the rear of his Ferrari, in Bologna we had checked his car and there was nothing touching the wheel and we changed his tires, so he left Bologna with new tires. He arrives in Guidizzolo, enters the bend, first passes over the cat's eyes broken by a carriage and the tire gets damaged, causing the car to go off the road. There is also another hypothesis, that on the long Po straights, due to the high speeds, the bodywork damaged by the accident on the Futa has moved slightly, causing interference with the burst tire. These are all hypotheses, but none of them have ever been proven with certainty.

The de Portago accident was a big problem, even on a social level. He was a Grandee of Spain, his wife ran his banks in America, his mother lived between Deauville, Florida and Paris. After the drama his mother wrote a letter to Ferrari and no one has ever been able to find her again. It was a great international uproar. Alfonso “Fon” de Portago, a great Spanish nobleman, had interests all over the world and was a man of the world. He was always on the go but never carried any luggage with him. In the cities where he did his business, he always had a suite booked in some five-star hotel. The hotel porter made him find new underwear every morning, a pair of trousers and a black T-shirt, all new. If it was necessary he would buy a suit or a tuxedo, then he left everything as a gift to the concierge. His wife spent her time, with her two children, in one of her residences or in some fashionable location. "Fon" was a handsome man full of women, at that time he was also in a relationship with actress Linda Christian. I was with him in Brescia on the morning of the start of his last race. We ate breakfast together to decide on the latest competition strategies. He was cheerful, he wanted to participate in this adventure, the race with an official Ferrari galvanized him. He got up from the table, a girl asked him for an autograph, in turning around he inadvertently bumped into a waiter who spilled the tray with tea and milk on him. I looked de Portago in the face, I saw him suddenly petrified and pale, his gaze had changed, it was as if he were afraid. After all, nothing serious had happened I thought, what could he be worried about? De Portago looked at me, "Tavoni, in my country pouring milk and tea is bad, it is synonymous with bad luck, today will be a bad day!" He was very superstitious and very upset about the little accident that had happened, a fact of no importance but, for him, a kind of premonitory symptom. The marquis is not at all convinced of racing, so much so that, in Maranello, in the Ferrari workshops, on Friday 10 May 1957, he offers his teammate Luigi Musso the opportunity to take his place. But the Roman driver, still recovering from the disease, declines the offer. I almost immediately forgot the tray that fell and the words of de Portago, words that rang in my mind like boulders when I arrived urgently at the site of the tragedy.

There was great sympathy between Enzo Ferrari and Alfonso de Portago. The Spanish nobleman routinely raced in endurance races with cars owned by him. For the Mille Miglia in '57 Ferrari wanted to give one of his official cars to the Spaniard, who wanted to compete in the Italian race at all costs. De Portago, as co-pilot, chose Edmund Nelson, a friend of his, English journalist and former RAF aviator.

The car, in going off the road, overturned and hit the crowd on the side of the road. When I arrived in Guidizzolo, on the site of the tragedy, I went to the mortuary of the cemetery. I saw the remains of de Portago and Nelson alongside those of the other victims. I was shocked, there was very little left, de Portago was in two pieces, legs on one side and torso on the other, while Nelson had half his head off, the car had overturned and his helmet had crawled on the ground for many meters, horrible stuff. All around there were the remains of the bodies of the spectators. Ferrari sent Giberti to help me to negotiate with the Police and Carabinieri. I was really sick, for a period of time I had nightmares, screamed at night.

It was a bad job mine, having to inform Ferrari and relatives after a tragedy and I had to welcome de Portago's wife. “My husband was a very free man, he loved adventure and racing, I could expect him to end like this”, were the words of his wife when she arrived from Evian where she was on vacation. She placed a rose on the body, it was her last goodbye to him. Ferrari was indicted, his license was suspended, he was accused of having used tires not adequate for power. Ferrari reacted very badly to the tragedy, for a week he did not show up, remaining isolated in his pain. There was a moment when I saw him cry, alone, in the courtyard. We tried to stay close to him, Amorotti told him “these are races, if he would have continued to make machine tools he wouldn’t have had these risks, they are part of the job, like joys for victories."

Enzo Ferrari, accused of manslaughter and personal injury, will be acquitted on July 26, 1961 for not having committed the crime. The consequence of the tragedy and of the media storm is the definitive end of the race. The Mille Miglia is too dangerous, enough with road racing, it will be reborn after 20 years, in 1977, as a simple historical re-enactment.

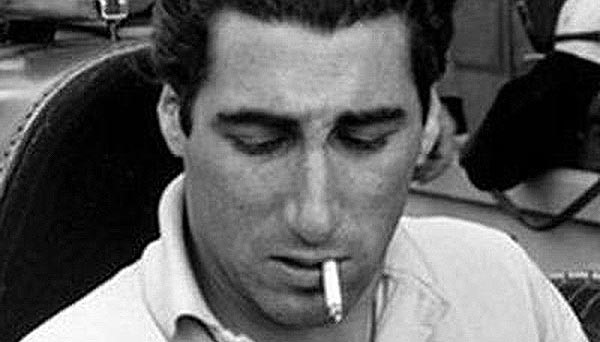

Ferrari's fastest playboy: Alfonso de Portago. Few playboys lived as hard as Spanish marquis `Fon' de Portago — or drove as fast. Doug Nye on how Ferrari's most dashing driver earned Enzo's respect.

Alfonso de Portago arrived in motor racing as an aristocratic amateur, but eventually established himself as a serious contender. Bettman / Getty Images.

For any who admire the days when drivers were fat and tyres were skinny, the name ‘Fon’ de Portago will have particular resonance. Not because he was tubby – another Fangio or Gonzalez; far from it but because his name stands tall among those who burnished that special charisma which is Ferrari’s.

He was educated in Britain, France, Spain and the USA but hated academia and loved sport.

He played a ferocious game of Jai-Alai (pelota), swam competitively, won a tennis title and took up top-level polo, yachting and shooting. He was a tremendous, fearless, horseman, winning three successive French amateur titles. He rode twice in the Grand National, in 1950 and ’52, but spun off both times. He lived at a frantic pace, rode in as many as 150 races a year and in one week at Pau was said to have saddled 32 winners from 36 rides.

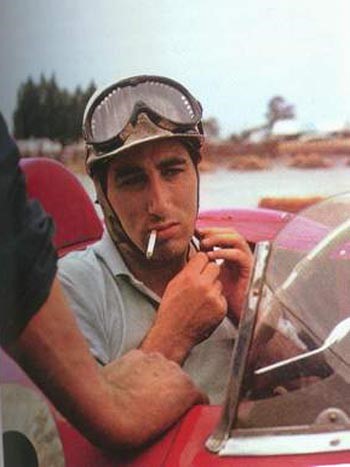

A born gambler, he was renowned at roulette playing several tables at once. Like James Hunt later, he flouted all dress codes. Where Hunt preferred T-shirt and jeans, ‘Fon’ was seldom without his favourite grubby leather jacket, thick black hair habitually uncut, dark-shaven, a cigarette pasted to his lower lip.

Driving his Ferrari / Lancia D50 at the 1957 Argentine GP.

Raffish, insouciant wealth was underlined by his home address in ‘Millionaire’s Row’: 40 Avenue Foch, Paris. Yet he was also virtually teetotal and would obsessively play pinball in a favourite cafe, his ambition to win free games and play all day, buckshee.

Some friends maintain he also sharpened his reflexes by having them throw knives at him. He’d catch them all by the handle. Don’t try this at home kiddies; de Portago was formidably well coordinated. One party piece was to juggle raw eggs, another was sleight-of-hand.

One former girl-friend frankly described to me his spectacular sex life as “fully acrobatic”. It was certainly very complicated.

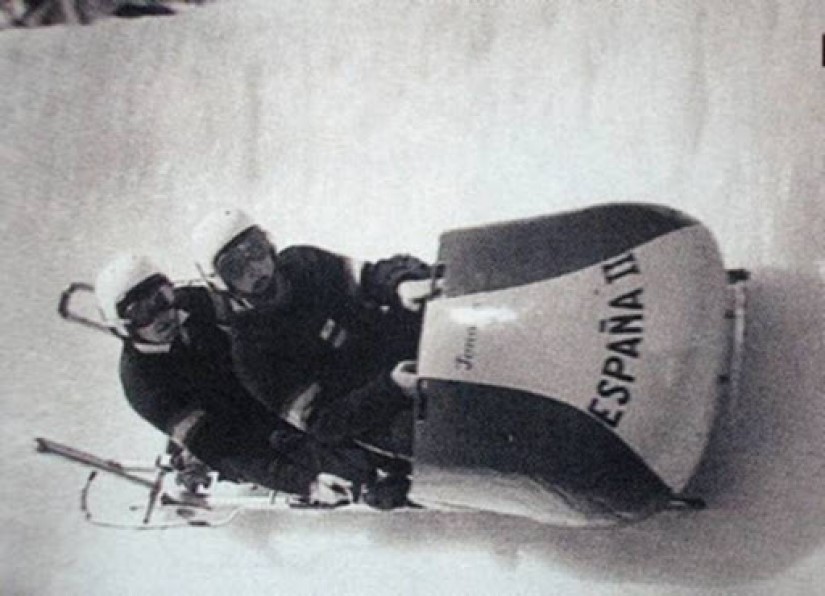

Winter sports became a particular forte.

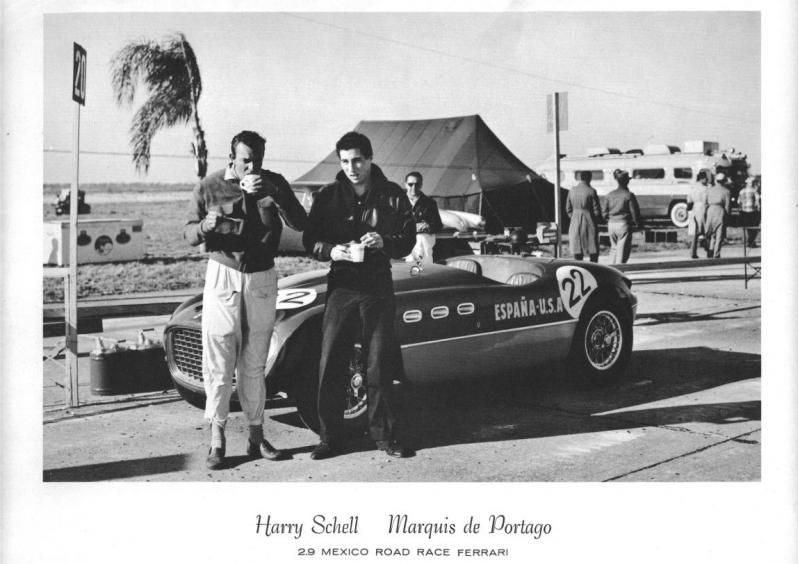

The Cresta Run at St Moritz led to strong friendship with established ‘bobber’ Edmund Gurner Nelson a quiet American from Honolulu, 12 years his senior. I’m told “they hunted as a pair”. As ‘Fon’ grew too heavy for the turf, Nelson suggested dirt-track racing amongst the peasantry, in Paris, Strasbourg and Metz. ‘Fon’ shone, loved it and moved up-market, into road racing.

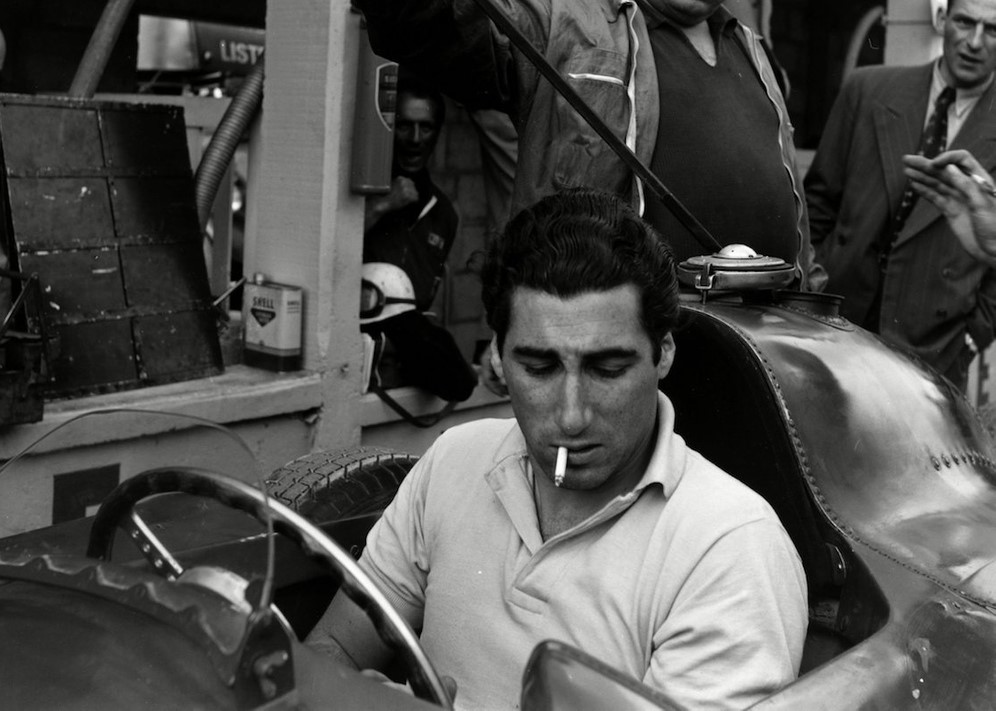

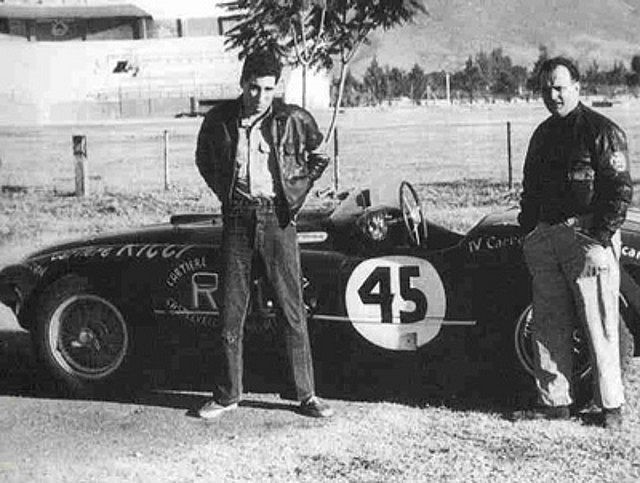

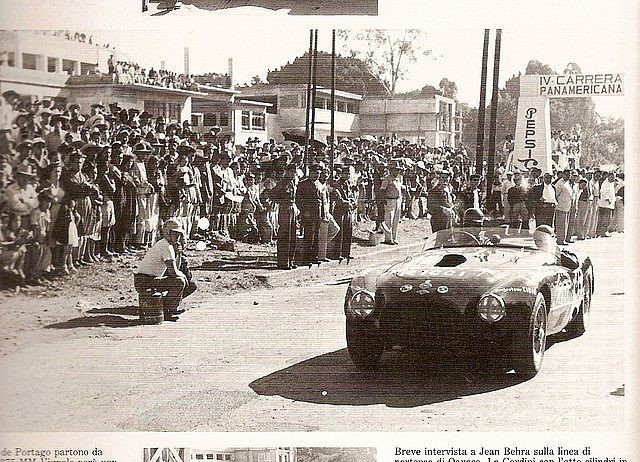

At the 1953 New York Motor Show, Ferrari importer Luigi Chinetti invited him to the Mexican Carrera Panamericana. ‘Fon’ recalled: “that involved sitting next to him while he drove I was terrified!” Their Ferrari 340MM failed on day two but de Portago was utterly hooked.

Established Franco-American driver Harry Schell latched on. ‘Fon’ bought a second-hand Ferrari 250MM which they co-drove in the ’54 Buenos Aires 1000km and Sebring 12-Hours. A new Maserati A6GCS/53 followed and factory tester Guerrino Bertocchi spent time tutoring ‘Fon’ on how to drive it. He was enthralled, privy now to the art of heel-and-toe. At Le Mans he led the 2-litre class before retirement and then scored his first road-racing win at Metz.

His mother subsequently bought him a sports OSCA which he took to the German GP meeting at Nürburgring, where in practice Maserati’s driver Onofre Marimon crashed fatally. De Portago had counted him as a friend. Badly shaken, ‘Fon’ still raced next day but crashed and was scooped into an ambulance. ‘Fon’ objected, thumped the driver, dumped him in the back and drove back to the paddock with the seat hanging out of his trousers. His crash? ‘The Porsches were bumping me in the corners. Of course I bumped them back. It worked very well until I got behind Herrmann the leader … that’s how I went off.” Typically, that night found him in the casino at Bad Neuenahr, his bruises developing nicely. He won $10,000 which he invested in a new sports-racing Ferrari Monza, which was promptly shipped to Mexico for the Carrera.

There, bad fuel burned pistons.

Spain's marquis de Portago (right) concentrates on the engine of his sleek Ferrari as mechanics Giannino Parravicini and Enzo Monari, both of Italy, make final repairs following a recent overhaul. Portago registered the fastest clocked time during warm ups for the Nassau road race, with 2:20 on the 3,1/2 mile runway course at Windsor Airfield.

At Nassau, in the Bahamas Speed Week, he then won two races and placed second in a third. Enzo Ferrari paid extra attention – this client could drive. He was duly “permitted” to order a Ferrari 625A F1 car for the 1955 season and earned a quasi-works drive at Sebring. But in wet practice for the Silverstone May meeting, the 625A understeered into the bank and he broke a leg. That sidelined him until September when he co-drove a Monza with Mike Hawthorn in the Goodwood 9-Hours. It was a chastening experience: “Hawthorn is five seconds a lap faster!” But Mike liked him, coached him and drank and womanized with him. ‘Fon’s lap times improved.

Getting his Ferrari / Lancia over the line at Silverstone in ’56.

At Caracas, Venezuela, he was second behind Fangio. And then, back at Nassau, he won again by way of introducing the first Ferrari 250GT Berlinetta, solidly founding that fantastic bloodline.

He missed the Argentine races in ’56 but was given works-backed drives at Sebring and in Germany, France, Sweden and Italy. Mid-season, Enzo Ferrari offered him a works F1 ride to keep the team’s spare Lancia-Ferrari D50A in the hunt during the French GP at Reims.

In the British GP he was called in to hand over to Peter Collins, then limped Castellotti’s ruined D50A to the finish. In Germany he was again called in, but didn’t object: “one day someone will be asked to hand over to me”. Ferrari valued the gentlemanly side of ‘Fon’ “which always managed to emerge from the crude appearance he cultivated”.

But he really shone in his 250GT, winning at Oporto and Castelfusano (Rome), then winning the Tour de France, where, navigated by Nelson, he was able to beat Stirling Moss/Houel’s Mercedes SL `Gullwing’ and earn the Ferrari its ‘Tour de France’ title. He won in it again at Montlhery, where two friends, the Swiss Benoit Musy and French veteran Louis Rosier, both crashed fatally. Rosier had asked ‘Fon’ to drive his car, but changed his mind at the last moment. The Marquis took Musy’s Spanish wife to the hospital and what he saw horrified him. He emerged harder, matured, tempered: “every driver believes it can’t happen to him. Inside I just know that it won’t happen to me.”

His third visit to Nassau then added a second and third to his record, but no victory, then it was back to the Alps for the winter sports season. On the Cresta Run the record from The Stream to the finish had stood for 25 years. ‘Fon’ broke it, then went to Argentina where, with Gonzalez, he shared fifth in the Grand Prix and, with Collins and Castellotti, third in the 1000km.

In February at Havana, Cuba, he led Fangio fair and square in his 860 Monza until a fuel line failed. He hurt himself at St Moritz before the Bobsleigh World Championships, but recovered to share seventh at Sebring with Luigi Musso.

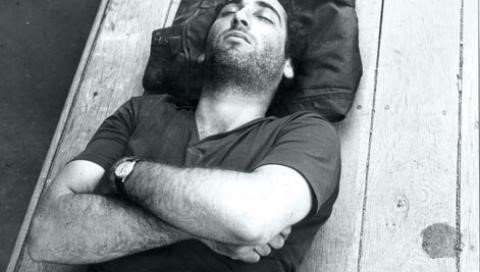

Fon's specialty was endurance tests, although he didn't disdain a nap whenever there was a chance.

By this time he was an international celebrity, plastered as much across the social columns and tabloid front pages as he was in the sports sections. His marriage failing, he was linked with movie actress Linda Christian. He revelled in his lurid image, declaring: “if I’d lived 600 years ago I’d have been killing dragons or helping maidens in distress, but nowadays the only man who can help a maiden in distress is a doctor.”

He was 28. ‘Ed’ Nelson was 40 and they now prepared to run the trusty 250GT in their first Mille Miglia. But ‘Fon’ bent it in reconnaissance. Ferrari then called him into his office and entrusted him with the most powerful works car he’d ever driven – a 4.1-litre four-cam V12-engined 335S.

He drove it well. He lay fourth at the Rome control, then inherited third. Enzo Ferrari was at the Bologna depot to see his boys blast through: veteran Piero Taruffi (who would win), Wolfgang von Trips second, de Portago/Nelson third, Olivier Gendebien/Jacques Wascher fourth in their special 250GT. Ferrari recalled: “the difficult parts were over, the game was played.”

But ‘Fon’ and his soulmate did not finish. The paparazzi rushed to the scene and let rip.

Next day ‘Fon’ de Portago was interred at San Isidoro, Madrid, in the vault of the related Linares family. The vault of the adventurous de Portagos was full.

'The kiss of death' led to the tragic end of the predecessor of Alonso and Sainz in F1 and in Ferrari. 15.05.2020.

Alfonso de Portago in his Ferrari.

Alfonso de Portago, the Spanish 'James Dean', had a passionate life despite dying at 28: he was a multi-sport player with successes in different sports and a busy love life.

"If I die tomorrow I will have lived 28 wonderful years," Fon de Portago said in an interview at the beginning of May 1957. On the 12th of that same month he lost his life in the XXIV edition of the Mille Miglia, in Guidizzolo, 40 kilometers from the finish line.

Alfonso de Portago's car after his fatal accident at the Mille Miglia in 1957. Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images.

Shutterstock editorial.

Alfonso de Portago's Ferrari 335 remains in the ditch where the car ended, after killing 10.

The remains of the Ferrari destroyed during the Mille Miglia Automobile Race. Guidizzolo, May 1957. Photo by Emilio Ronchini/Mondadori via Getty Images.

The remains of Alfonso de Portago's accident.

Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Ángel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton (XI Marquis de Portago, XIII Count of Mejorada and Grande de España) was born in London on October 11, 1928 in the bosom of a family of the highest lineage and the most prestigious in Spain: he was a descendant of Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, discoverer of Florida; godfathered at baptism by King Alfonso XIII; grandson of Vicente Cabeza de Vaca, mayor of Madrid; and son of Olga Leighton, Irish and one of the richest women in North America, since she had inherited an immense fortune after being widowed by her previous husband, one of the founders of HSBC (The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation); and Antonio Cabeza de Vaca, film actor and hero decorated by the pro-Franco party after the Civil War.

Alfonso De Portago and Peter Collins. Klemantaski Collection, Getty Images.

Nothing in Alfonso's childhood was comparable to his contemporaries in his country, including the freedom that always surrounded him, largely due to the lack of his father, who died of a cardiac arrest in the shower when Fon was twelve years old. He lived with all kinds of luxuries among the properties that his family had in Spain, France, Italy, Great Britain and the United States ...

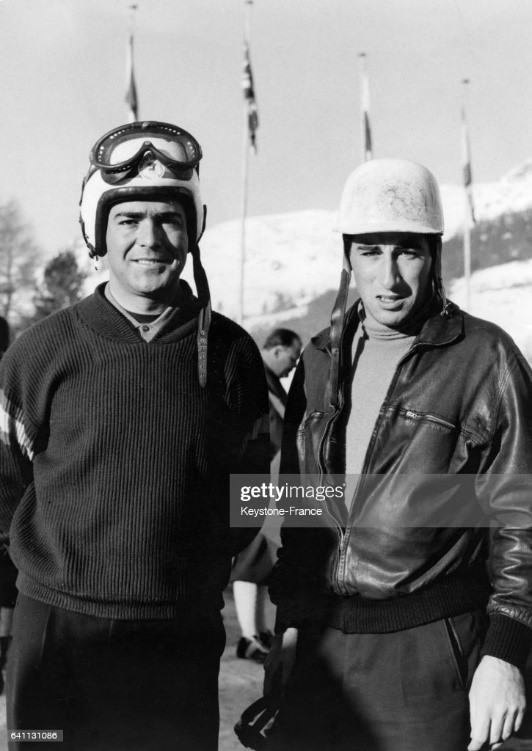

Luis Munoz and Alfonso de Portago at the Bobsleigh World Championships in St. Moritz, Switzerland, on February 3, 1957. Photo by Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

He was a great tennis player, golf player, polo player, an expert swimmer and skier, a fantastic horse rider, which led him to participate in two editions of the 'Grand National' and win more than one hundred races ... and rank fourth in the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina d'Ampezzo in the two-man bobsleigh with Luis Muñoz Cabrero.

Alfonso de Portago at the 1956 Winter Olympics. George Silk, The Life Picture Collection.

Fourteen hundredths separated them from the bronze, that went to the US team. And, with the addition of his cousin Vicente Sartorius and Gonzalo Taboada and Martínez de Irujo, they finished ninth in the four-man bobsleigh. Sports gestures that he linked to crazy things, always related to women or to risk, as when he won $ 5,000 in a bet after passing with a plane under the London Bridge at the age of 17 in a reckless action.

Cesare Perdisa, Alfonso de Portago, Peter Collins, Stirling Moss, Grand Prix of Great Britain, Silverstone Circuit, 14 July 1956. Drivers breefing before the start of the 1956 British Grand Prix. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

Here is one of those frenetic Ferrari pit stops. This is at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone on July 14, 1956. The car is a Lancia-Ferrari, actually one of the 1955 Lancia D50 Grand Prix cars which were turned over to Ferrari in the summer of that year when Lancia was no longer able.

Alfonso de Portago in a Ferrari D50 at Silverstone, England, in 1956.

Alfonso de Portago, in a Lancia Ferrari, in the pits at the 1956 British Grand Prix. Photo by GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Recognized as a 'playboy' of the time, he triumphed in motorsports to the point of being an official Ferrari driver (where he earned $ 40,000 per year at the time) and achieved the first F1 podium for a driver of Spanish nationality (before de la Rosa, Alonso and Sainz), by being second in the 1956 British GP, alongside Peter Collins ... and being surpassed only by Juan Manuel Fangio. “There comes a time when money bores you and even women don't satisfy you anymore. At that moment you discover a drug that becomes everything for you, that drug is called risk”, he said as one of his phrases that have survived him. However, precisely his feminine conquests were one of his great weaknesses and the black legend of his fatal accident considers it the main cause of the sad end.

“Making love is the most important thing I do every day.” Alfonso de Portago.

Two or three days old beard, 180 centimeters tall and an athletic physique, long hair for the time, a cigarette stuck to his lips and a leather jacket were the hallmarks of a man of few words and exquisite manners who could stay in the best hotel in town or lie down to sleep on a bench in any park. Or decide to paint a Ferrari 750 MM black ... with a wall paint brush. A somewhat crazy driver, but with great technical qualities and courage, with his performance he convinced Enzo Ferrari, who was the one who directly trusted him after having received the demonstration of his skills as a 'gentleman driver' and as an official 'sports car' driver.

Mexican actress Linda Christian, Alfonso de Portago's girlfriend, in Cuba in 1957. Hy Peskin Archive (Getty Images).

His death, after which he received the nickname of the Spanish 'James Dean', brought together all the dramatic overtones that the best Hollywood screenwriter could have imagined. In 1957 he had a consolidated relationship with Mexican artist Linda Christian, ex-wife of actor Tyron Power, first Bond girl ('Casino Royale') and mother of Italian singer Romina Power.

Portago was recruited by Ferrari to race the Mille Miglia, a race on the open road, without excessive safety, that was done non-stop on the Brescia-Roma-Brescia route.

Alfonso de Portago and Edmund Nelson at the Mille Miglia in which they lost their lives. Klemantaski Collection (Getty Images).

The aristocrat would drive a Ferrari 335S, with Nelson as co-driver and number 531 (his departure time). And the night before he had written a letter to his beloved, which said: “as you know, my love, I didn't want to race, but Enzo Ferrari made me do it. Hopefully I'm wrong, but maybe it's going to an early death. I don’t like the Mille Miglia, no matter how much one trains and memorizes the route, it is almost impossible to remember each of the curves of the route and a minimum error of the driver can kill fifty people, since it cannot be avoided that the spectators crowd the streets." Alfonso de Portago.

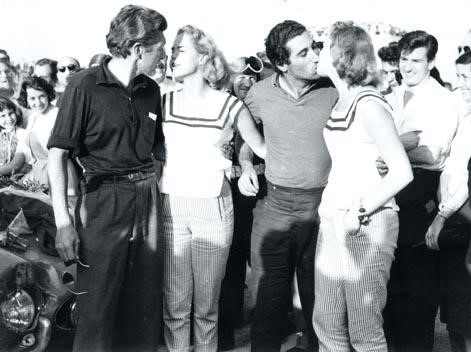

Linda Christian and the marquis de Portago kiss at the 1957 Mille Miglia. Bettmann (Bettmann Archive).

Precisely, according to legend, Portago and Christian decided to express their love when the driver arrived at a confluence of streets in Rome, in full competition. Alfonso braked the car and they both merged in a long goodbye kiss ..., which the transalpine press baptized, after the fatality, as the 'kiss of death'. After accelerating again, the vehicle seemed to have touched a curb with the front wheel and slightly bent one of the suspension arms. In one of the last stops, he was warned of this circumstance by a mechanic, but the Spaniard decided to continue.

Alfonso de Portago at the 1954 24 Hours of Le Mans. Bernard Cahier (Getty Images).

At the entrance to Guidizzolo, at 250km/h, the front tire blew up unbalancing the Ferrari and causing it to skid. It went off the road, took off and flew into a wooded area where many spectators were sheltering from the sun and watching the race. Portago died instantly at the age of 28, as did his co-driver Nelson, 42 and a dozen fans including five young children. The tragedy, which also left 30 injured of varying degrees, led the Italian Government to cancel forever the most important road race in the world as it was disputed.

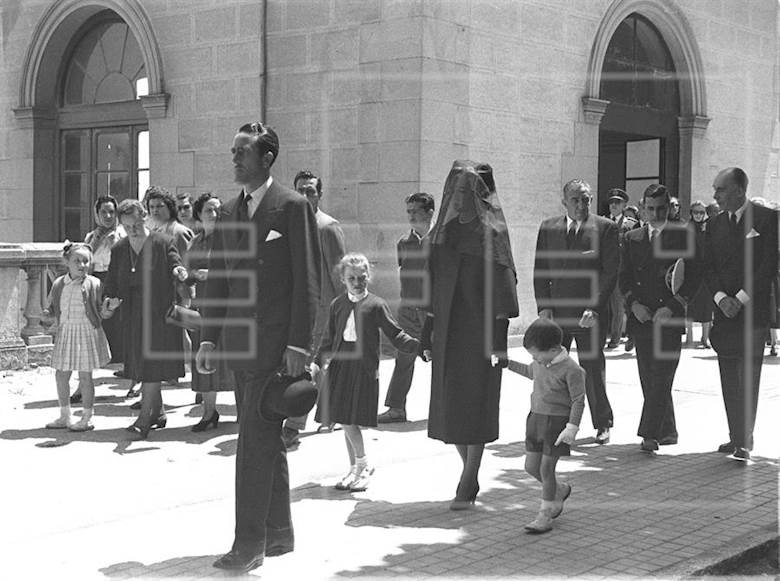

Funeral of marquis Alfonso de Portago and the victims of his accident at the Thousand Miles race. His bereaved wife, Carroll McDaniel, from New York and the driver's mother. Photo by Francois Pages / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Carroll McDaniel and her two children.

The Marquis de Portago died at the wheel of his Ferrari, during the last stage of the Mille Miglia race, on the famous Mantua-Brescia section, on May 12, 1957, in an accident which also caused the death of his co-pilot and nine spectators: the families of the victims gather near the coffins displayed in the church. Photo by Francois Pages / Paris Match via Getty Images.

May 18, 1957, Linda Christian at the Funeral Mass for the marquis de Portago. Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency/Keystone USA via Zumapress.com.

Enzo Ferrari at de Portago’s funeral.

Italian race car driver and businessman Enzo Ferrari attends the funeral of Spanish racing driver Alfonso de Portago, 14th May 1957.

Juan Manuel Fangio carrying the coffin.

Funeral of marquis de Portago and the victims of his accident at the Thousand Miles race. Guidizzolo, Italy, May 14, 1957. Many people came to pay their last respects to the victims. Photo by Francois Pages / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Portago was the first Spaniard in a F1 Ferrari, then Marg Gené and Pedro de la Rosa arrived as testers and Fernando Alonso as official driver. The Asturian far surpassed the successes of the pioneer. In 2021 it will be the turn of Carlos Sainz, a more than worthy heir of the talent and courage of one of the non-biological children that Enzo Ferrari took in to give glory and luster to the mythical 'Scuderia'.

The marquis Alfonso de Portago, his life for racing, up to an unjust epilogue! By Massimiliano Amato. April 28, 2020.

Nicknamed the Fon by his friends, the marquis lives with his family in Biarritz and, since he was a child, he practices many sports. A passion inherited from his father, who is one of the best golfers in Spain.

Alfonso likes the life of an aristocrat, but this does not prevent him from feeling the need to always face new challenges: it will be precisely by driving for a bet the helicopter of a friend who is still a minor that he will discover the passion for speed.

This need is perfectly linked to another of Alfonso's interests, which is to travel the world.

In fact, in October 1953, the marquis decided to leave for Paris to visit the car show.

Just as he wanders around the stands the irony of fate, or destiny, leads him to meet Luigi Chinetti, who, in addition to being a driver, has also recently become the official importer of Ferrari in the United States.

The feeling immediately springs up between the two and, when Chinetti offers him to become his co-driver, the Fon accepts.

A month later, Alfonso is Chinetti's navigator during a stage of the Carrera Panamericana championship.

This race will become an important stage in the life of the marquis de Portago.

In fact, during this experience, despite being unable to reach the finish line together with Chinetti, Alfonso finds the answers to that restlessness that had accompanied his youth and that had always pushed him to test himself.

Harry Schell and Alfonso de Portago, Ferrari 250 MM Vignale Spyder.

On 24 January 1954, with a Ferrari 250 MM Vignale Spyder he owned, the Spanish marquis made his debut as a driver, participating in the race called Buenos Aires 1000, paired with Harry Schell.

Alfonso immediately proves to be talented, as both will finish second at the finish.

In the second half of 1954, de Portago moved to Europe, accepting the Maserati offer.

The adventure with the Italian team doesn’t start well, as the Spanish driver is forced to retire at the 12 Hours of Sebring, at Aintree International, at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and on the Circuit de Bressuire.

Fon’s redemption arrives, however, on the Circuit de Metz, where he earns his first career victory.

Alfonso de Portago in an Osca MT4 1500 at the 1954 Tour de France.

In subsequent events, however, including the 12 Hours of Reims, the race held on the Nurburgring circuit and the Tour de France, where however he will race with a Osca, he doesn’t reach the finish line again.

Alfonso de Portago in his Ferrari 750 Monza.

At the end of November, 1954, the Spaniard returned to drive the Ferrari 750 Monza in the Carrera Panamericana, but an oil leak forced him to retire one more time.

The first victory with the Maranello cars came a few days later at the Nassau Trophy Road Races, where he also obtained two second places.

Even in 1955, due to his very aggressive driving style, the marquis was unable to find continuity of results.

Alfonso de Portago and Umberto Maglioli, Ferrari 750 Monza, 12 Hours of Sebring, Sebring, 13 March 1955. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

At the 12 hours of Sebring, the Spaniard is forced to retire and, even to his debut at the Mille Miglia, the result does not know a different epilogue.

De Portago's only good placement is at the Coupes de Paris where, starting from second place on the grid, he finished fourth at the finish.

The Maserati’s of n.14 Behra, n.16 Roberto Mieres and n.18 Luigi Musso are in line astern in the Pau paddock on 10.04.1955. By Jesse Alexander.

De Portago in his Ferrari at 1955 Pau Grand Prix. By Jesse Alexander.

But the marquis is not satisfied with this result and wants to test a Formula One car.

For this reason, the Spanish driver buys a Ferrari, which he takes to the track at the International Trophy in Silverstone. But the desire to test himself, always looking for new challenges and risks, costs him dearly: on the British circuit, not only does he destroy his Ferrari ending up off the track at over 200 kilometers per hour, but he also breaks his leg.

This incident will force him to stop for three months.

20th August 1955. Mike Hawthorn with his co-driver, the marquis de Portago, at Goodwood racing track. Photo by Keystone/Getty Images.

Upon his return, aboard a Ferrari 750 Monza, the marquis seems determined to cancel his early season performances, taking pole at the 9 Hours of Goodwood but, in the race, a collision forces him to retire.

The same situation is repeated at the Aintree International: Alfonso is fourth in qualifying but then an accident does not allow him to see the checkered flag.

It goes worse at the Tourist Trophy, where he doesn't even manage to line up on the grid.

In the last months of 1955, Fon changes gears: in Venezuela he is third in qualifying and second in the race while, a month later, he wins the Governor's Trophy and the Nassau Ferrari Race and, again in Nassau on the occasion of the Production Race, scores a great fourth place finish.

Fangio, Musso, Castellotti, Shell and de Portago, Sebring, 1956.

The beginning of 1956 seems to be able to give continuity to the positive streak of the last months of the previous year but, once again, at the 7 Hours of Sebring, due to a problem with a valve of his Ferrari 857S, the marquis doesn’t see the chequered flag.

At the 1000 km of the Nurburgring, after having obtained a good third time during the qualifying tests with a Ferrari 290 MM, he manages to get on the third step of the podium.

In addition, he also obtained a good fifth place at the 1000 kilometers of Paris while, in Oporto, he conquests his first victory of the season.

Alfonso’s excellent form continues at the Super Cortemaggiore, where he improves the fifth position of qualifying, finishing fourth.

The good results in the first part of 1956 allow Fon to realize his dream: to become a Formula One driver.

In fact, for a long time now Enzo Ferrari had been struck by that genius and reckless driver and so decided to add him to the team together with Juan Manuel Fangio, Peter Collins, Eugenio Castellotti, Luigi Musso, Oliver Gendebien, Paul Frère and Andrè Pilette.

The Drake, in the book he himself wrote about the Scuderia Ferrari drivers, described the marquis de Portago as follows: “a man of extreme physical courage but also an unusual man, always pursued by the fame of a ladies’ man. A magnificent tramp for his unkempt behavior, long beard, very long hair, the immortal leather jacket and the slouching step".

1956 French GP at Reims, Ferrari D50 Streamliner of Alfonso de Portago.

De Portago's debut in Formula One takes place on 1 July 1956 at the Reims circuit, which hosts the French Grand Prix.

During qualifying, while the Ferraris score a hat-trick with Fangio on pole, Castellotti second and Collins third, the Spaniard is ninth, with a gap of seven seconds and six tenths from the Argentine.

De Portago's first Formula One race, however, will only last a few kilometers.

In fact, on the ninth lap, a gearbox problem will force him to park the D50 along the track, while Collins and Castellotti complete the one-two of the Prancing Horse, with Fangio fourth.

What is positive, however, is that the marquis is quick to take the measurements of the new car and, in Great Britain, he repays the trust of the Drake. In qualifying, while reducing the gap from the leaders, he is only twelfth, six seconds behind Moss' Maserati.

The next day, paired with Collins, he is the protagonist of a great comeback which ends in second place, one lap behind Juan Manuel Fangio.

For de Portago this will be the first and only podium in Formula 1.

A few weeks later, the marquis will arrive in Germany with the aim of fighting for victory.

Instead, in qualifying he still struggles and is only tenth while in the race, again paired with Collins, in an attempt to recover he is the protagonist of an accident during the tenth lap, allowing the only Ferrari to reach the finish line, that of Fangio, to become the world leader.

Alfonso de Portago, Grand Prix of Italy, Autodromo Nazionale Monza, 02 September 1956. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images.

Alfonso de Portago at the 1956 Italian Grand Prix in Monza.

The last race of the championship takes place in Monza: de Portago doesn’t go beyond the ninth time in qualifying and, on the ninth lap, a problem with the tires forces him to retire for the third time in four races, ending the season in fifteenth place in the drivers' standings with only three points, while Fangio graduates, for the fourth time, world champion.

But if with the single-seaters the satisfactions for the marquis are few, the same cannot be said for the covered-wheel races.

In fact, throughout 1956, de Portago is divided between Formula One and touring car races: at the Sverige Grand Prix he is third, at Kanonplet he is second, while he scores a splendid double by winning the Tour de France and the Coupes de Salon.

The series of four consecutive podiums is interrupted only at the Rome Grand Prix, in which he finishes fourth. Subsequently, in Venezuela, he is forced to retire but redeems himself at the Governor's, where he scores another second position.

The only disappointing result that the marquis collects is seventh place in the Preliminary Nassau but, twenty-four hours later, on the day of the Immaculate Conception, he is second in the Nassau Ferrari and, with third places in the Nassau Trophy and in Caracas, he closes his 1956 with three consecutive podiums.

Alfonso de Portago with Gary Cooper in Cuba in February 1957. Getty images.

Alfonso de Portago talks with actor Gary Cooper, as they look at the n.12 Ferrari 860S Monza before the Grand Prix of Cuba race on February 24, 1957 in Havana, Cuba. Photo by Hy Peskin/Getty Images.

Despite its sculptured Scaglietti flanks, never has an 860 Monza looked quite so good … Actress Linda Christian adorns ‘Fon’ de Portagos’ Ferrari. The marquis Alfonso De Portago, Spanish nobleman and journey-man driver, was accompanied by Linda Christian at the 1957 Cuban Grand Prix, an event for Sports Cars.

In 1957, de Portago's racing season begins concurrently with the first race of the Formula One world championship, which takes place in Buenos Aires on January 13th. Paired with Gonzalez, the Spaniard closes in fifth position.

This umpteenth disappointing result closes his adventure in the top flight.

In fact, at the following Monaco Grand Prix, which usually takes place in May, the Spaniard will not be present in the grid.

As in the previous year, while waiting to return to drive the 801, the marquis is dedicated to touring car racing.

Alfonso de Portago, Sebring, 1957. Riverside was a jazz label in the 50s but its founder, Bill Grauer, was a racing fan who produced this description of de Portago: “of all the drivers at Sebring, the marquis de Portago has the least experience being limited by only two years in racing cars. Ferrari's confidence in him may well be justified however because of his wide success in other dangerous sports: he has distinguished himself on an Olympic bobsled team, in polo and as a steeplechase jockey. He is a swashbuckling young man with streaming black hair almost to his shoulders. It would be difficult to predict what his future will be in cars, driving is an art which requires great concentration and a spirit of dedication, the marquis, undoubtedly conscious of his notoriety as Spain's ranking nobleman, seems uncertain which sport will demand his greatest attention and, since he is a connoisseur of all the arts of good living as well, it is problematical is he will ever achieve the fame his very obvious talents might lead him to."

Also in Buenos Aires, together with Castellotti and Collins, Alfonso climbs on the third step of the podium, obtaining the same result driving a Ferrari 857 M in Cuba while, paired with Musso, he finishes seventh in the 24 Hours of Sebring.

The marquis gets the last victory of his career in the Coupes de Vitesse, a race in which he returns to the wheel of the Ferrari 250 GT.

After retiring in the race held in Hawaii, the Spaniard should have taken a break to concentrate in view of the second race of the Formula 1 world championship, in Monte Carlo, scheduled for 10 May 1957.

Enzo Ferrari and Alfonso de Portago.

However, Enzo Ferrari, having become aware of Musso's forfeit at the Mille Miglia, immediately thinks he can replace the Italian driver with de Portago.

The Commendatore asks his sports director Tavoni to call him to communicate the choice directly in his office.

A meeting, the latter, told by the Drake himself:

Enzo Ferrari: "do you know why I made you call?"

Alfonso de Portago: "no. Tavoni didn't tell me anything".

Enzo Ferrari: "to give you that opportunity. Do you want to do a race for me, Alfonso?"

Alfonso de Portago: "of course I want it".

Enzo Ferrari: "then listen to me, you have to race on the road".

Alfonso de Portago: "on the road?"

Enzo Ferrari: "yes, because on the road you learn to improvise, to react to unexpected events and to control the shivers of fear. On the road you become great drivers, Alfonso. And, if you finish in a position worthy of the Scuderia Ferrari, you can continue to drive a Formula One, but in the official team".

Alfonso de Portago: "so, which race are you thinking about?"

Enzo Ferrari: "the Mille Miglia, of course".

Alfonso de Portago: "why the Mille Miglia?"

Enzo Ferrari: "because it is the race that forced the automotive industry to study cars suitable for such a demanding test. Because it is the most difficult. Because it is the most beautiful of all".

Alfonso de Portago: "what car do you want to give me, the Berlinetta?"

Enzo Ferrari: "I want to give you the Sport".

Alfonso de Portago: "then I'll be at the start, Mr. Ferrari".

Enzo Ferrari: "find a co-driver".

Alfonso de Portago: "I already have one, it will be Edmund Nelson, an American journalist friend, so he can write a good story".

Alfonso de Portago, while betting with Gendebien on which one of them would have reached the finish line first, is nervous: in fact, the Spanish driver is forced to participate in the Italian race with a car he has never driven, the 335 S.

Indeed, Alfonso even sent a letter to a New York magazine, on the eve of the Mille Miglia, in which he wrote: "losing control of the car and knowing that for me there is absolutely nothing to do, stay there, frozen in terror and waiting for things to take their course: this is the thought that scares me more than any other. But racing is a vice; precisely because it is a vice it’s almost impossible to give it up. All racers swear that at a certain age they will no longer race, but very few are capable of doing it seriously. They have the temperament of hardened players and, like such, always postpone the time to get away from the game table. Sometimes, when a driver learns that a colleague of his has been killed on the road, he vows not to race anymore. But then he thinks: it will never happen to me. And, on the third day after the tragedy that struck his friend, he returns to prepare himself for another race".

Alfonso de Portago getting into his Ferrari 335S to race the 1000 Miglia in 1957. Credit Getty Images.

De Portago smokes his last cigarette before leaving and confesses to his mechanics: "I will do a prudent race, never forcing, with the sole purpose of becoming familiar with the road and the characteristics of the race; in other words, I have no ambition to win, but I only intend to train on the course and then try to win next year". He had said the same words to actress Linda Christian, whom the marquis wanted to keep away from the race: he gives her an appointment in Milan for Sunday evening assuring her that, at least for that time, there was absolutely no reason to fear anything given that, more than a race, his participation in the Mille Miglia would have been a simple and peaceful training.

Then, soon they would get married.

Nonetheless, for Ferrari the race seems to be going well.

At the moment of refueling in Bologna, Collins is leading the race, followed by Taruffi and von Trips.

The photo shows the marquis de Portago and his co-driver in their Ferrari car at Peschiera during the race, shortly before their tragic crash.

De Portago, instead, is in the back and is attempting a desperate comeback.

Alfonso de Portago, during the Mille Miglia in 1957.

On passing through Mantua, the marquis, while handing his book to be stamped, inquires whether a telegram from Rome had arrived for him; the Spaniard is interested in knowing if there are any communications from Linda, but they say no.

1957 Mille Miglia. 531 Ferrari 335S MM de Portago – Nelson, 532 Ferrari 335S MM Wolfgang von Trips …

There are no communications since the actress, from Rome, is flying to Milan.

Then, de Portago takes two sips of mineral water and sets off quickly to the point that Gurner, who is greeting the crowd, hits his chest against the windshield.

This is one of the last photos taken of Alfonso De Portago in his Ferrari at the 1957 Mille Miglia. This photograph is eerily quiet, despite all the people and activity in the image. The naive madness of this type of road racing is made so clear. The impending tragedy is almost palpable, the photographer crouching right on the edge of the wall, flirting with disaster.

After a few kilometers from the restart, Collins has a technical problem. Ferrari, present on the spot, asks the driver to retire in order not to risk accidents and, in order not to take further risks, asks von Trips to escort Taruffi, at his last race, with Gendebien completing the Prancing Horse hat-trick.

To spoil the Ferrari party, however, is a tragic accident involving de Portago.

While Collins is forced to retire, the marquis is between Cerlongo and Guidizzolo and is pushing hard the accelerator, contrary to the initial idea of simply getting familiar with the track, because there are a few kilometers to go and he is convinced that he still has chance to overtake Gendebien, thus winning his personal bet.

The Spaniard drives with his usual aggressiveness but, at 16:03 on May 12, 1957, near Corte Colombra di Cavriana, the left front tire gives out.

As usual, the municipal roads used for racing are surrounded by numerous spectators, therefore de Portago tries a correction to avoid injuring the people crowded along the route, but the Ferrari n. 531, which until a few moments before was traveling at a speed estimated between 250 and 280 km/h, is now out of his control.

The marquis desperately tries to regain control, bending over the steering wheel to withstand the effort required but, after just 130 meters, the tire detaches from the rim overcoming the driver's resistance.

The rim will act as a pivot for the car, which swerves to the left, slips between two curbstones raising a cloud of dust and, with the rear right part, touches a curbstone breaking it. As a result, the car is straightened and thrown thirty meters off the road.

Meanwhile, the Spanish driver's car mows down the group of spectators present, dragging them into the channel below. The flight is interrupted by a light pole, cut at a height of one meter and twenty centimeters above the ground.

Gaetano Beghelli, a farmer who is on the right of the road, dressed up and with his hat high on his head because it is already hot, has his hand in his pocket and smokes when, in the distance, he sees the car approaching. When this is almost in front of him, even louder than the noise of the engine he hears the burst of the tire: "for about forty meters the car zigzagged along the road, then leaned to the left and slipped between two curbstones. It was already on the edge of the ditch when it hit a curbstone with his right side and eradicated it. For the backlash the car was straightened and moved about fifteen meters off the road in a parallel direction. And it was on this stretch that it mowed down nine people. Then it aimed with the hood in the ditch and finally, like a bullet, jumped all the way down the road and ran into the ditch on the other side. In this leap it cut a light pole one meter and twenty centimeters off the ground.

The second driver, Edmund Nelson Gurner, is thrown to the left side of the road.

After, the silence.

Not even the wounded scream.

The pause will last a few seconds, then the screams will rise from all sides.

Gaetano Beghelli and other people who remained unharmed will take care to clear the road in just four minutes, before other cars arrive. Elda Pilon, resident of Volta Mantovana, who is on the right side of the road, will say: "I held the two children Daniele and Fausto, aged five and eleven, close to me. My husband Mario, who was injured, was on the opposite side with his friends. I remember seeing the car arrive because I too was curious to see."

"I was afraid, but I looked curious. I saw the car skid, I saw it arrive on the group that was in front of me. In fright I closed my eyes. When I opened them again there was a fuss covering everything. I didn’t hear anything. I took the children and threw them on the lawn, then I crossed the road and ran there, into the tangle."

"My husband was in the mud: my Mario had his head covered in blood".

"We pulled my husband onto the road and, when I spotted an 1100, I loaded him onto it and had him taken to the hospital. Ah, what a stuff. If he can save himself, then we won't see any more of a race."

Linda Christian, 1966 at Rotterdam.

As soon as she got off at Linate Linda, who was waiting for the Spaniard, asks if you already knew the classification of the Mille Miglia: "what about de Portago? Hasn’t he arrived?" She asks disappointed, before the chilling response tells her what had happened.

As of the following hours, controversies break out.

Enzo Ferrari, still shaken by the disappearance of Eugenio Castellotti during a test in Modena, is targeted by the media pillory of Italian journalists.

As if that were not enough, Maurice Trintignant insinuates that some of the Ferrari mechanics, at the last stop, would have told the Spaniard that between him and Gendebien there was only a minute of distance, when in reality the gap was over seven minutes, pushing the Spaniard not to change the tires.

Enzo Ferrari will be put on trial.

According to the indictment, the Engleber tires fitted in de Portago's Ferrari number 531 were not suitable for racing in the Mille Miglia.

Ferrari will live badly the following months and will delegate to his collaborators the task of making sure that the relatives of the victims are compensated. Precisely for this reason, when the Modenese manufacturer will come to know that the insurance companies will try to resist, he will be very angry.

But this is nothing, compared to when he will get out of his acquittal, which will come only four years later, on July 26, 1961: "the accusation is manifestly unfounded and is based exclusively on the statements of the first experts hired by the Public Prosecutor: but already some logical considerations, obviously arising from the contradictions and inaccuracies of the experts themselves, had immediately invalidated the new conclusions".