Patrick Depailler, the-coolest and bravest driver of his era, died with a steering wheel in his hands, as he had chosen to do from the first corner in a racing car. Hard to believe that this time next year he'll have gone gone 40 years. He was a F1 driver in the historical and heroic period of the 1970s. He is the example, like few others, of the pure spirit of the pilot who gives his life to being the fastest on the track. Any other activity becomes secondary or even an obstacle. For a driver like Patrick the future is not expected. You race today, with any car, in any weather and in any physical condition. There are no other questions to ask. Every single curve is a fierce challenge. A challenge lost at the start. Because it is not possible to challenge fate many times. So, one dies tragically and becomes a legend in the hearts of enthusiasts. But you race for yourself, for this irrepressible desire for freedom and solitude. It is not possible to rationally explain such a choice even for the most ardent of enthusiasts. It is simply a necessity no one can escape. You can live to race but to race you have to live. Depailler was himself the antithesis of the modern F1 driver. He drank, he smoked, he spoke his mind and he was a huge fan of dangerous sports. The legendary Jo Ramirez called him "the symbol of the fearless driver." He was a provincial boy who, in the 70s, won the hearts of thousands of racing fans. A real fighter who never backed out and always took up the challenge when it came to dominating a piece of metal, whether it was a F1 single-seater, a motocross bike, a hang glider or the bars of a hospital bed. He embodied the spirit of his old mentor, Jean Behra. He was like that Patrick, indomitable, fearless and even a little philosopher. For him life had to be lived always to the fullest. He looked at everything that a human being would have repudiated with terror and challenged it. Head up and Gauloises in the mouth. His daily ration was 20 cigarettes, a massive dose of nicotine that today would be unthinkable for a modern sportsman, but not for a time when pilots could lose their lives every Sunday.

Patrick Depailler at Nurburgring in 1976. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

Patrick Andrè Eugene Joseph Depailler was born on August 1st of 1944 in Clermond-Ferrand, Central France, in a relatively well-off family. His father, an architect, wanted to see his son in his footsteps. But, as it often happens, he had other plans for his future. Although he had finished his studies, young Patrick was already under the influence of the motorsport virus. He had started racing, both on motorbikes and in cars. The transition to cars was encouraged by another former centaur, Jean Pierre Beltoise who, after having broken his bones for the umpteenth time on two wheels, had thought of getting on a racing car. Eventually Depailler would win back his father’s favours who will support him financially through his early career. For a good reason: Patrick was a very talented driver, in 1971 he was winning the French F3 Championship and in 1973 he won the European F2 Championship. From here on the natural progression was racing in Formula 1 and he quickly found a place within the Tyrrell team. Racing with them from 1972 to 1978, he competed purely for the thrill of racing and his passion was the driving force behind his career.

Patrick Depailler at Hockenheim in 1977. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

We remember him in the six-wheeled Project 34 Tyrrell, for his approach to it summed up the character of the man to perfection. While team-mate Jody Scheckter was utterly dismissive of this highly experimental car, Depailler loved it and was instrumental in convincing Tyrrell that it should be raced. He scored five podiums in it too, as did Scheckter including victory at Anderstorp, so it couldn’t have been as rubbish as all that.

Patrick Depailler (Tyrrell) second, race winner James Hunt (McLaren), John Watson (Penske) third, in the French Grand Prix at Paul Ricard, France, on 04 July 1976. Photo by David Phipps / Sutton Images.

He finished the 1976 season 4th overall, even if he didn’t score any victory.

Patrick Depailler (Tyrrell) third, Mario Andretti (Lotus) winner, Niki Lauda (Brabham) second, at the Argentinean Grand Prix in Buenos Aires on 15 January 1978. Photo by David Phipps / Sutton Images.

Carlos Reutemann celebrates victory on the podium with Mario Andretti, 2nd position and Patrick Depailler, 3rd position, at Long Beach on 02 April 1978. Photo by David Phipps / Sutton Images.

Carlos Reutemann celebrates victory on the podium with Mario Andretti, 2nd position and Patrick Depailler, 3rd position, at Long Beach on 02 April 1978. Photo by David Phipps / Sutton Images.

When his first win finally arrived in 1978, in a “normal” 4 wheel Tyrrell, everybody in the paddocks was happy for him, as this victory had been a long time in the making (he will score a total of 19 podiums in his F1 career). He lived for racing but also loved living outside the race track, enjoying a glass of red wine with a Gauloise in his hand, driving fast cars and taking to what we would call today extreme sports. He was naturally a likeable character, the grown up reckless boy you couldn’t get mad at, as his boss Ken Tyrrell recalls. Sure they don’t make them like that anymore and maybe for a good reason: on or off the track, most of the time he was dancing on a thin red line. His wife Michelle, the love of his life born on the same day of the same year he was born, divorced him. He had married her in 1967, at the age of 23, his first and only girl until then. She became too scared of what he was doing.

Jacques Laffite celebrates victory on the podium with teammate Patrick Depailler, 2nd position. Didier Pironi stands on the podium in 3rd, despite Carlos Reutemann crossing the line in 3rd position. It was believed he had been disqualified for receiving a push start, promoting Pironi to 3rd. Reutemann would later be reinstated to 3rd position after the Brazilian Grand Prix at Autódromo José Carlos Pace on 04 February 1979. Photo by David Phipps / Sutton Images.

Ever a contender and only seldom a victor, Patrick was looking for more for the 1979 season, so he signed with Ligier. They gave him a winning car alright: by mid-season he was leading the Championship, sharing the top position with Villeneuve, perhaps his nearest kindred soul in the sport. And then things took a turn for the worse: easily the biggest accident of his life until his last came when he crashed his paraglider in the mountains near his home in France, breaking both his legs. For a while it looked like he might spend the rest of his days in a wheelchair and the racing community was keen to write off this two-time GP winner. They were wrong: he came back, better than ever and, had the Alfa-Romeo been more reliable, would have scored many strong finishes. In the months spent in the hospital all he could think of was returning to the circuits. Even facing amputation, his biggest fear was that he will not be able to race anymore. For him being alive really meant being able to race. After multiple interventions he was discarded from the hospital only to discover that Ligier had signed Jacky Ickx. Patrick couldn’t accept he was to be the second driver within the team, so he made the decision to go with one of the oldest names in motorsport, but basically the youngest team in this brave new ground effect era: the storied Alfa Romeo, led by Carlo Chiti. The opening of the 1980 competitional season saw him still not completely recovered from his injuries but, despite walking around with crutches and being barely able to hit the ground without feeling a terrible pain, Depailler qualified at the back of the grid of the first two races before putting the Alfa seventh on the grid in Kyalami and then third at Long Beach. He also managed to stay in the leading group in Monaco until a mechanical failure (of which this car had many) concluded his run. The team was in an upward path and so was his humour, as he was slowly and surely getting back to his former best, or even better with the help of physiotherapy. After what was to be his last race, the British GP of Brands Hatch, he left for a summer holiday together with the boss of Elf Motorsport division, the man that had also supported Patrick in his early career, Francois Guiter. He was with Valerie, a new girl he loved and it seemed as if all things will work out well, just as he always made others believe. Before leaving for the holiday Depailler had canceled his life insurance policy, a gesture that could seem risky, but it fully encompassed the nature of this brave and unlucky man. Unfortunately, he left the holidays early to begin testing on the Alfa Romeo 179, 10 days before the German GP. Back then the old Hockeinheim race track was made up of endless straights and corners to be taken at full speed, with little safety measures taken into considered, no run off areas, no tyre barriers. That was the norm back in the day. To test that day there were both Depailler and Giacomelli ("Jack O’Malley"), Patrick's young team mate. Patrick did some laps then stopped in the pits. He approached Giacomelli and exclaimed "there is something wrong, Bruno try it yourself". Giacomelli put on his helmet, fastened the fireproof and slipped into the cockpit of the Alfa 179. Depailler lit a Gauloises and sat on a pile of tires, waiting. Giacomelli did two laps at a moderate pace then returned. Everything seemed fine. New tires were mounted on the Alfa, in the meantime Depailler put on his gloves, pulled up the zip of the suit and threw the umpteenth Gauloises of the day on the ground. Unaware that it was the last one. The Alfa passed the finish line once to finish the warm-up lap, then it didn't pass anymore. The appointment with destiny came in a flash, as cynical as the character of the French pilot. The Formula One driver, by definition, represents the man who fears nothing. Dangers normally perceivable slowly diminish, while you run at more than 270 km/h on tracks designed to challenge every human limit. Hunting for a state of mind for which there must be no place for fear of risking your life, because adrenaline takes over. Once, two, five, ten, a thousand, until you understand that, thanks to that control, you can dominate the asphalt, in the company of talented adversaries.

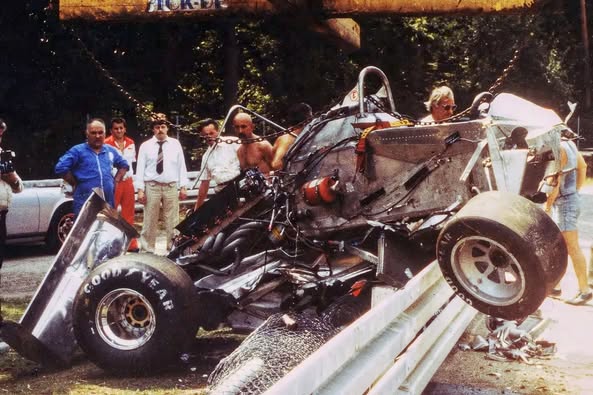

The crash of Patrick Depailler at Hockenheim in 1980.

The crash of Patrick Depailler at Hockenheim in 1980.

It was on the Ostkurve, where the premature epilogue occurred, that the suspension of his car apparently broke, sending him flat out at 280 km/h into the Armco barrier. He didn’t stand a chance and died right on impact, paying the ultimate sacrifice. Depailler eight days later would have turned thirty-six. The Alfa Romeo 179 with its Autodelta V12 proved to be a fast and powerful beast, although not reliable. A few months later, Bruno Giacomelli scored a pole position on the last GP of the season in the very car that the Frenchman had spent so much time providing developing work. After the race, which he failed to finish, Giacomelli, gave the nicest tribute to his former teammate: “unlike me, Patrick would have won with this car.” What remains today of Depailler, in addition to his exploits? His courage, his desire to always try and the will to dominate the mechanical means whatever its nature, remain etched in the minds of the enthusiasts. A man who had great faith in his own means, combined with the intimate awareness that the game with life never depended on fate, but on his courage to challenge fate. Remains the portrait of a reckless man, whose tenacity and perseverance warm the heart more than cold statistics. Remains a trace of braking, the last desperate attempt of Patrick.

|

|

|

|

Going through some old tapes recently, I came across an interview with James Hunt in the early '80s. It was typical James, forthright but well-reasoned and I smiled often as I listened again to that mahogany voice. Although Hunt was sometimes spiky and disagreeable during his racing career, once he had given up driving, only the better parts of his complex personality remained. On the tape, as always, he took relish in saying exactly what he thought. "Patrick Depailler ... well, I've no doubt that he had a death wish. Very pleasant bloke but I always thought he was barking mad... Why? Look at the way he lived his life," James said. "Riding motorbikes without a helmet, that sort of thing. Depailler seemed to need to find risk in everything." It was true that Patrick was never a man to give a thought to safety in motor racing, but still I couldn't agree with Hunt's contention that he had a death wish and neither did Nick Britian, his manager for many years. "No, no, not at all. Patrick loved life more than most people but he accepted the inevitability of death." Depailler's life ended in August 1980, in a testing accident. There was only the scream of a single Alfa Romeo V12 to be heard at Hockenheim that Friday, which is how they knew the disaster had happened. Immediately they rushed out into the forest, but their haste was in vain. The Ostkurve was then a top-gear corner, taken flat, and the Alfa never started into it, striking a guardrail head on, then vaulting over. Photographs of the accident were more than usually poignant and wretched: bits of shattered car lying across catch fencing folded up behind the guard rail, ready for the GP a week hence. For mere testing no one had thought to install it. But if I disagreed with Hunt's contention that Depailler had had a death wish, still I always doubted that he'd retire. Brittan concurred: "he knew he floated right out to the fine edge he was powerful quick and I think he knew it would happen one day. There was never any question of retirement in his mind. Patrick was almost like a professional soldier a combat soldier. He absolutely loved what he was doing there was nothing better in the world than being a bloody good race driver. He was the nearest thing to a sort of automotive SAS man and people like that are aware there's a good chance one day you're not going to pack your kit bag. But that is not the same as having a death wish, far from it." Most of Depailler's F1 career was with Tyrrell and Ken always speaks of him with great affection: "Patrick was very French — never without a Gauloise, loved red wine. In a lot of ways he was a little boy all his life, always wanting to go skiing or motorcycling. And he had this trusting belief that everything would be all right in the end. He lived for the present. I gave Patrick his first F1 drive, at Clermont-Ferrand in 1972, and then offered him a third car for the North American races in ‘73. A big chance for him — and ten days before he breaks his leg falling off a motorbike! Later, when he was driving full-time for me, I had it written into his contract that he kept away from dangerous toys." When Depailler's Tyrrell won at Monaco in 1978, it was one of the days everyone in the paddock was happy. So many times before his fingertips had been on the hem of victory, but always it had slipped away. At the end of that season he left for Ligier, and with sorrow, for Tyrrell was truly like family by now. But the Ligier proved more competitive. After winning at Jarama, the fifth round, Patrick shared the Championship lead with Villeneuve. Ligier's JS11 was the fastest car of the moment, but Depailler's rivalry with his team mate Jacques Laffite, was very definitely that: a rivalry. There were no team orders and at Zolder the two of them ran away from the rest — and into tyre troubles. Jody Scheckter's Ferrari won and Guy Ligier was furious. Patrick was bemused. "If you are a racing driver," he shrugged, "surely you race..." If Ligier was angry in Belgium, a few weeks later he was apoplectic. Unlike Tyrrell, he'd not precluded 'dangerous toys' from Depailler's contract. After the Monaco GP, Patrick went hang-gliding, and severely injured his legs. The general reaction to Patrick's accident was chillingly hard-nosed. In commercial terms, perhaps it was inevitable, but I found disturbing the lack of sympathy for a man perhaps staring at life in a wheelchair. When I spoke to him, he said that the worst thing was not knowing if he would recover properly. "For a time there was the chance of amputation and I was very frightened. Not for five months was I sure to drive again." Without that, Patrick seemed to be saying, life would be insupportable; in his terms, being alive meant being a racing driver. I was very fond of Depailler, not least because his attitude to life and work was refreshingly haphazard in a world where dour automatons increasingly peopled professional sport. That said, working with him must have been sometimes maddening. Nick Brittan laughed at the memory. "Well, you never knew what was coming next. I remember one day there was a knock on my door and there stood this strange man. 'Patrick sent me', he said. 'I 'ave ze packet ...' He opens his hand — and there's this packet of uncut diamonds! 'You're to pay me £35,000', he says. Hang on, I said; tried all Patrick's numbers; finally I got hold of him: `Ah dites-donc! Forgot to tell you, sorry!' It was a rip-off, frankly, but the guy came back next day, got his money and at the next race I gave Patrick the diamonds. That was him — spontaneous decisions, quite often wrong. You or I would be appalled at being ripped off on that scale, but it didn't bother him: 'I am hopeless, you know, with the business matters...' Racing had a narcotic hold on Depailler. I remember his speaking sadly of the end of his marriage: 'she is scared of what I do — how can I blame her for that? But how can I stop this? First of all, it is necessary to be honest with yourself.'" After the hang-gliding accident, he thought only about coming back to F1. They say no driver is ever the same again after dreadful leg injuries, but Patrick was the exception. He may have hobbled unsteadily, but on the track he was unimpaired. His hobbies were such as scubadiving, skiing, sailing — and the hang-gliding. He would look askance at colleagues carrying tennis racquets. "Le sport dur!" he would say. That was the appeal. Patrick had only two heroes: Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Mercicx, both five-time winners of the Tour de France. Francois Guiter, Elf's competitions boss for so long, had a special affection for him. After the British GP they holidayed together in the Azores. "I never knew him happier than then," Guiter said. "He was with a girl he loved, completely relaxed and at peace. And then, of course, he went back early to do the test at Hockenheim." Nick Brittan recalls a dinner with Patrick at Zandvoort: "we were in a little restaurant, talking about getting his finances into shape. 'Patrick,' I said, 'we really ought to think about the future.' And I remember he smiled at that, 'no, no', he said, 'the future is for other people ...'"

|

|

|

|

Lafitte on Depailler. After three years of being the sole driver at Ligier, Laffite was suddenly faced with an equally fast Frenchman. Rob Widdows said in his article: “my God, I had so many! Which one will I choose, huh?” Jacques Laffite is talking about his myriad team-mates, recalling a long racing career that brought him many accolades as well as painfully broken legs in a crash at the British GP which ended it all. Now he hobbles around the F1 paddocks as a commentator for French television. A keen fisherman and golfer, Jacques is one of the good blokes of GP racing. “Patrick Depailler was my friend and also my enemy. He was very quick, you know,” he says forcefully. “He came to Ligier when I was used to being on my own there, so I was not so happy at the start. But he was a very quick driver.” We are going back to 1979. Jacques had been with Ligier since 1976, the French team running a single car until Depailler joined from Tyrrell during the winter of ’78. Guy Ligier, encouraged by Bernie Ecclestone to field two cars as FOCA began to develop the show that has become the F1 we know today, had found the money and wanted another French driver. “He was one of the fastest drivers in France at that time and so it was more interesting for the team to take someone like that. And anyway, Pironi wasn’t available and Jabouille was with Renault. I had been on my own at Ligier since the start but I knew Patrick very well and it was interesting for me. We had travelled together a lot when he was driving with Tyrrell so we were familiar and I think Guy thought it would be a good comparison to have another driver. I mean, he knew I was quick, but we never had any comparison with another man in the same car and the money was now there to do that.” It was difficult for Jacques to adjust and to accept that the team no longer revolved around him. He’d had plenty of team-mates at Williams but the Ligier team had become his own. “It was not because it was my team so much, it was more that I was worried we did not have enough money to run two cars, so I said to Guy, ‘we’ve made a mistake, not because we take Depailler, but because there is not enough money to make it work.’ We had so many new things: more mechanics, a T-car which we never had before and it was very different with three cars and so many more people. But we took the JS11 to Ricard in the winter of ’78 and straightaway it was bloody quick; the second lap through Signes I was flat, so I felt better after that. The ground effects were working well and I could see why the Lotus had been so fast during the previous season.” But now, with a good car, he had to form a working relationship with Depailler, wanting to make sure they worked as a team, especially as he knew that the other Frenchman would be right on top of the game. “I said to Patrick, ‘we are not here to fight, we are here to work. The car already seems really good and we will have success as long as we develop the car together, as a team.’ I told him, I don’t care who wins, you or me and he said ‘OK’ and we started the season with a very quick car. But we were not totally prepared; we didn’t really have enough people for two cars. But we started fantastically – I won the first two races and Patrick was not happy at all because he felt his car was not so good as mine, did not have so much downforce, even though he was qualifying at the front with me,” Jacques recalls. “But I told him it was not so simple, there were so many variables with the skirts and the downforce and that he would win some races. We had a chat about it and I told him to concentrate on the car and not to blame me, or the team. Like all drivers coming into an established team, like Alonso at McLaren, he wanted to prove that he was the quickest.” By the end of April, at the start of the European season, Depailler had got himself organised and won the Spanish GP at Jarama, starting alongside Laffite on the front row and leading all the way. Things were looking good for the Ligier team, with Depailler and Laffite now fighting Gilles Villeneuve for the world championship. But Jacques thought he should have won at Jarama. “I made a bad start from pole and Patrick got away in the lead,” says Jacques, “but we were a second a lap faster than anyone else. We were leading the championship and I thought the team would let me pass. It was crazy, we were racing each other, but the order never came. So I thought, OK, I will try to pass him and it all went wrong. I made the move on the inside of a corner – I should have waited until the exit – and the g-forces in the cockpit caused me to make a mistake in the gearchange, I went to third instead of fifth, and WOOP the engine blew up. I thought, shit, I am stupid and I just wanted to pack up and go home. But I wanted to be there for Patrick’s victory – it was difficult, he was my team-mate but we were very competitive also.” Jacques pauses for thought, then goes back a step. “When Patrick was with Tyrrell we spent a lot of time together, with my wife, with his girlfriend and we were good friends. But when he came to Ligier the relationship was different. We were still friends, but it’s strange because on the track I wanted to beat him, to get the better of him and then when we had dinner later it was another kind of friendship. He was very nice with me but he wanted to prove that he was quick. Maybe it was a little strange after the race at Jarama and I told him it was not necessary always to fight with each other, that we had to try and win the championship for the team as well as for ourselves. Then later we had problems with the car and we were not winning anymore.” A couple of days after the Monaco GP at the end of May, where Depailler finished fifth, he went home to Clermont-Ferrand. There was a month’s break before the next race in France and he wanted to practice his new-found passion for hang-gliding. Circling in the valleys of the Puy de Dome, he crashed into the side of the mountain and broke both his legs and his ankles. His 1979 season at Ligier was over; even his career looked in jeopardy. Little support was forthcoming from Guy Ligier, who claimed that the hang-gliding was a breach of contract. Depailler loved the adrenalin of danger. He’d already had a huge accident while riding a motorcycle and there were those who questioned his commitment to racing. But he was sorely missed by Ligier which took on Jacky Ickx, by now at the end of his powers, to see out the season with Laffite. “Maybe I did not need such a quick driver as Patrick as my team-mate; maybe I thought I should have been team leader and I know I was good enough to win the Championship that year,” says Jacques. “But Ligier and Gitanes did not see it that way and they wanted Patrick. I will not change my mind on that: I was confident I could do the job. But, yes, we did miss Patrick in the team after Monaco. He was always pushing, always trying to be quicker – like Hamilton with Alonso – but Ickx did not know the car so well and he was a very different style of driver. So really, after Patrick’s accident, I was left alone in the team. Unfortunately, it would have been better to have had Patrick still in the team, rather than Jacky, but there it was…” So how was their friendship at this time? How had they worked each other out as team-mates? “It was OK. Patrick was an intelligent man and we had a good relationship. No, it was not so bad, it was still a friendship,” smiles Jacques. “We had been cycling together, travelling together. But he was very motivated, always quick. We had the same approach to driving, the way we used the brakes, how we made the entry into the corner and my style was not so far from his, so we could work together. Not like with Keke Rosberg at Williams. That was difficult because Keke always loved the car to oversteer while I hated that and with Pironi it was always very hard, he was so political. But with me and Patrick we had very few problems like that, and we could communicate. I was never political, that was the difference between me and most of the others at that time. Patrick was a little bit political with the team and with the sponsors, but not in such a bad way.” The two Frenchmen were never to be re-united as team-mates. While Jacques stayed with Ligier for the 1980 season, Depailler went to Alfa Romeo where he struggled with an uncompetitive car until he lost his life in a horrible accident at Hockenheim. Too many lost their mates in this way.

|

|

|

|

The wonders of the internet brought me the in-car footage of Depailler driving a Tyrrell around a flooded Montreal race track. As examples of car control go, not to mention what F1 has lost in the last 40-odd years, there are few better. That guys balls must have needed their own seat. No ABS, no TCS, no sequential shifting gearboxes, no gear indicators, next to no cockpit safety, raced under even worse weather conditions. Dancing in the rain. The good old days when racing car drivers actually drove the car. Once upon a time the Formula One, best moment ever. This is perfect. Everything Patrick does is perfect. Awesome car control and lovely engine sound. F1 today pales in comparison. The legend says that the weight of the drivers balls was also taken into account by the engineers when designing the car. Depailler was an old school pilot of immense talent ....... in the pinnacle of F1..... before technology relegated the driver to "passenger in charge". Hearing the motor spooling up in every gear is freaking cool!

|

|

|

|

The video of Patrick Depailler at Long Beach in Tyrrell 008 is still one of my favourite on-board F1 video ever! Screaming Cosworths, fat slicks and buckets of oversteer - this is the F1 that I grew with. That was the days .. untouchable skills. His throttle-control and feeling for the limit was/is legendary. Depailler was one heck of a smooth driver, fluid and direct. Love F1 even today, but this is it, a proper manual gearbox like it always should be, where you are in total control of the car, no silly flappy-paddle gearboxes and, most important, no traction control. It is amazing to see the skills it takes to control a car with so much power going to the back wheels and in every corner a crash waiting to happen only avoided by the talent of this guy. Brilliant driving by a master. His work on the steering wheel in order to keep the car on the track is incredible! And he must at the same time change gears, manually! It was pure artisan work! One of the last years the F1 cars could oversteer in such a way. It's more than talent ... It's having the balls to put your very life on the line every time you go out on track. Nowhere is it more apparent than the F1 drivers from this era. Very few, if any, of us will ever be as good at anything as these guys were at driving .. They all did! Big brass ones! These were the real drivers! Lap of the Gods, terrific footage, pure aggression and touch throughout the laps. Definitely an era where car control actually accounted for something in Grand Prix racing.

|

|

|

|

Patrick Depailler fight with Ronnie Peterson in end of South African GP 1978 has little to envy to that of Dijon between Villeneuve and Arnoux. And within two years, both would be gone. Nice to see real racing drivers leaving space to each other, nowadays racing drivers try to push the other driver off the track. One of the all-time greats. Traction control under the right foot, the dance of the feet between left on the brake alternated with the "tip-heel” of the right, the rhythm of the delicate but peremptory counter-steering. They are different ages, of course, but here there is poetry, there is romance in dealing with a racing car, there is the essence of risk riders, the real ones, not those with the cap with the personal sponsor and the claims to choose their squire at the beginning of the season. Here was the struggle, fair but fierce struggle. The rest is “fuffa” (fluff), as the Italian journalist Giorgio Terruzzi would say.

|

|

I do not allow myself to try to understand the figure of a person who, by the way, has spent his life to be elusive. I am, we are, continually fascinated by this type of characters, now historical, as they depict that part of us that not everyone has the chance to express 100%. In 'The champions of Formula 1' of 1988, one of the best books on top-flight pilots, the author Keith Botsford says of Depailler: “the charming Patrick Depailler who was looking for death at any cost ... a pilot who defied death. The choice of Jody (Scheckter), young, fast, eager to learn, was the most intelligent; he could be hired at a relatively low price because he was impatient, aggressive and hopelessly ambitious. The same, but with something more, it could be said of his new team-mate Patrick Depailler... He had charm in abundance, a ready smile and a remarkable ability to attract women, even too much. He was a free spirit and also a good and reckless pilot. That extra something he owned was the desire to die. It is a feature that I noticed in other drivers, especially in Villeneuve, but Depailler was one of the few who openly declared it to me: 'if I thought to live too long, to be able to survive until after the next race, only until tomorrow, I don't know what I could decide to do.' Patrick had tried to die many times and finally managed to get what he wanted by showing up at the tests on the Hockenheim circuit exhausted and with red eyes." Those who lived those years often had the feeling of pilots daring a little further and the F1 at the time was really dangerous. They were real champions. Of those who finished an 80-lap race and lit a nice cigarette as if they had just finished making love: like Jochen, Hunt, Rosberg. At the time there wasn’t the physical preparation of today, yet they drove to the limit with very heavy cars that were difficult to drive. What times ... what heroes ... the real heroes of F1. For them driving was like making love ..., the athletic training was done by running with whatever had wheels on the weekends and doing tests during the week (third drivers and testers were still yet to be invented ...). The fatal accident was always lurking and they took things as if it were always the last day! Depailler certainly didn't spare himself and got a lot less than what he gave. When you identify some 'phenomenon' of the steering wheel, such as "ah but I don't fear anyone under water" or "the fast is my daily bread", here, remind them that Patrick Depailler has existed.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment