Three characters exuding charisma from all pores, that could fill a book alone. All drivers of that time were magnetic. Pieces of a Formula 1 that gave off dazzling charm. There will never be a moment like that again. Even just being able to talk about it is a privilege.

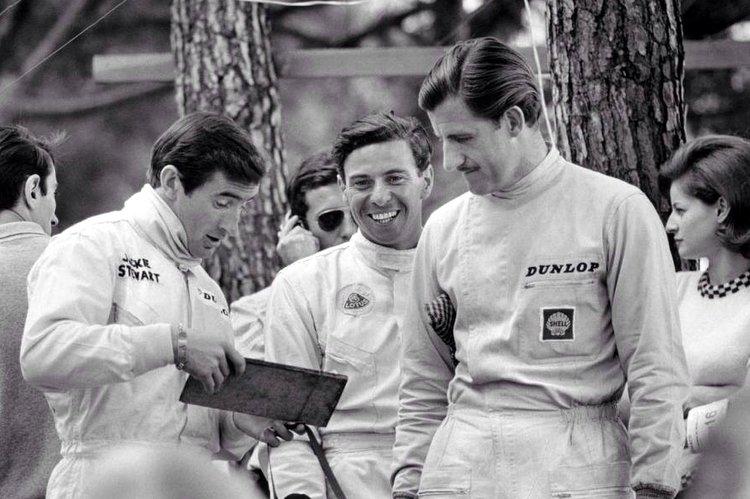

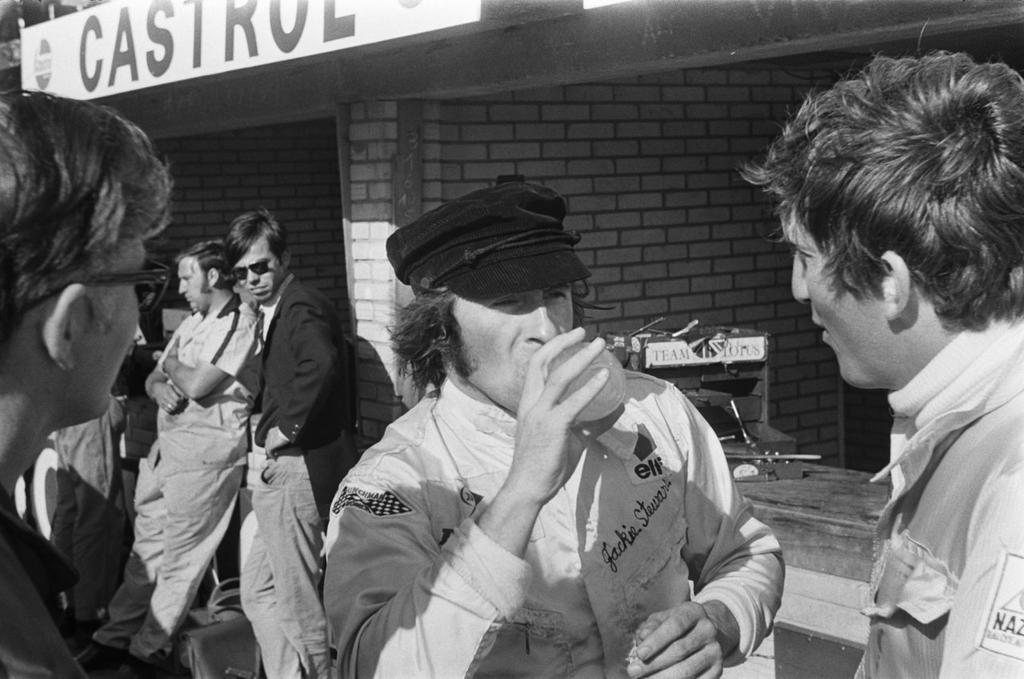

Jackie Stewart, Jim-Clark and Graham Hill were called “the three Musketeers of Formula 1”.

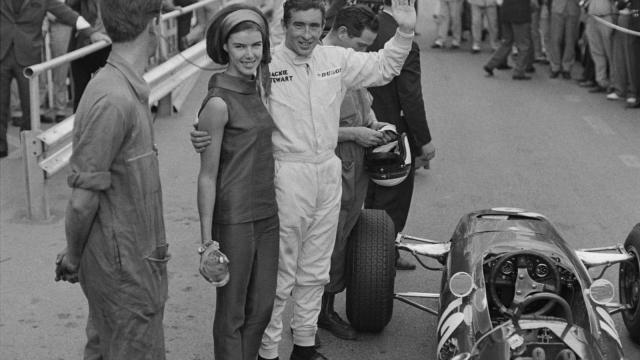

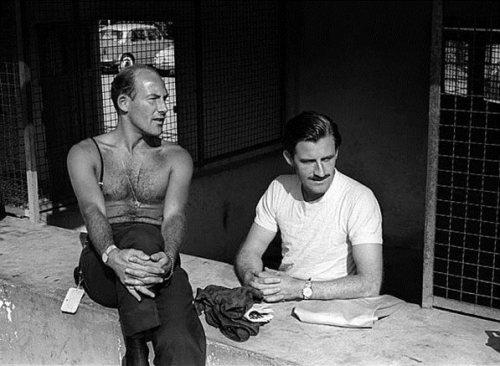

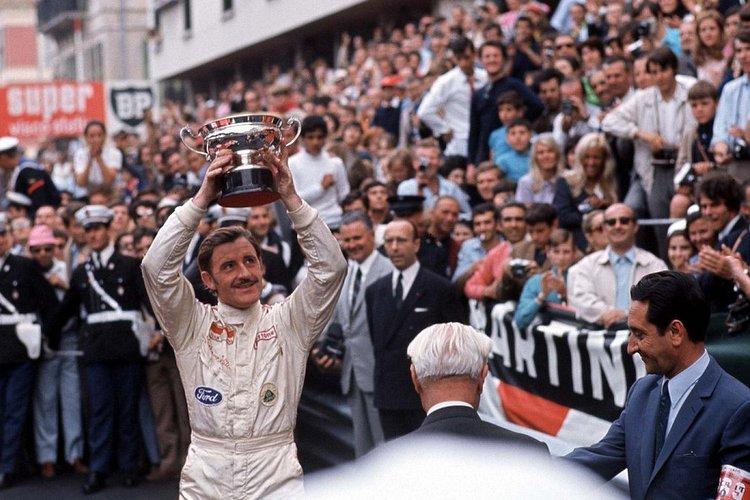

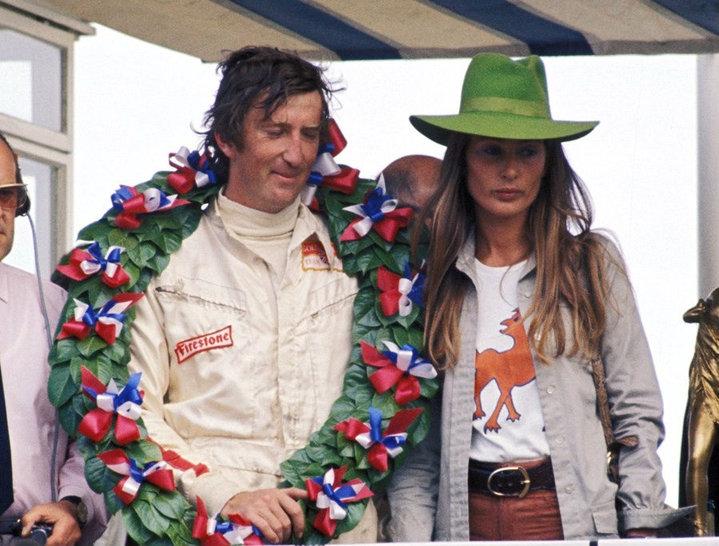

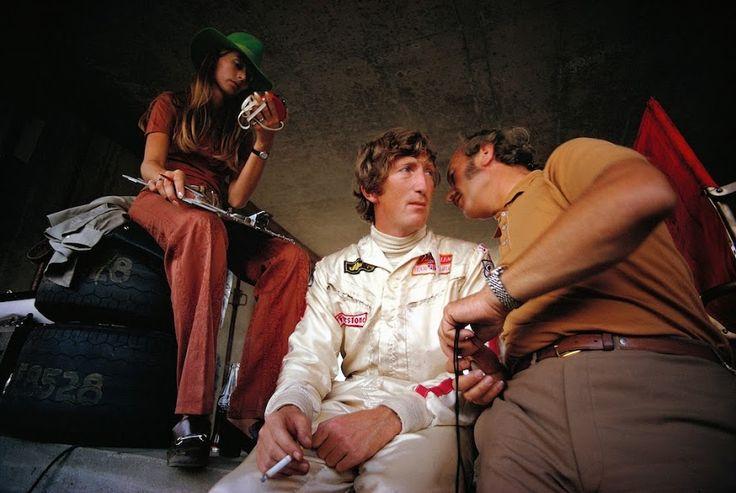

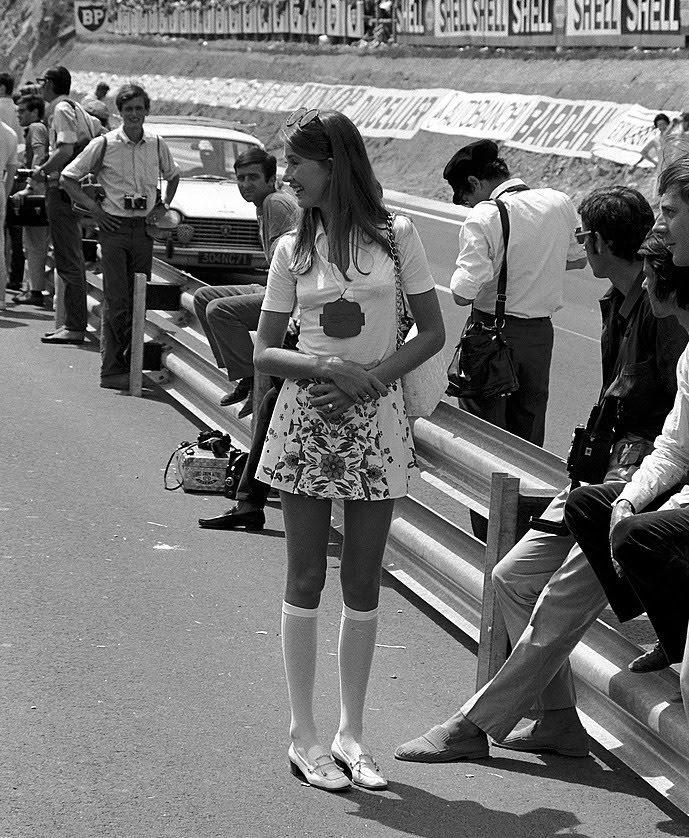

Monaco 1970.

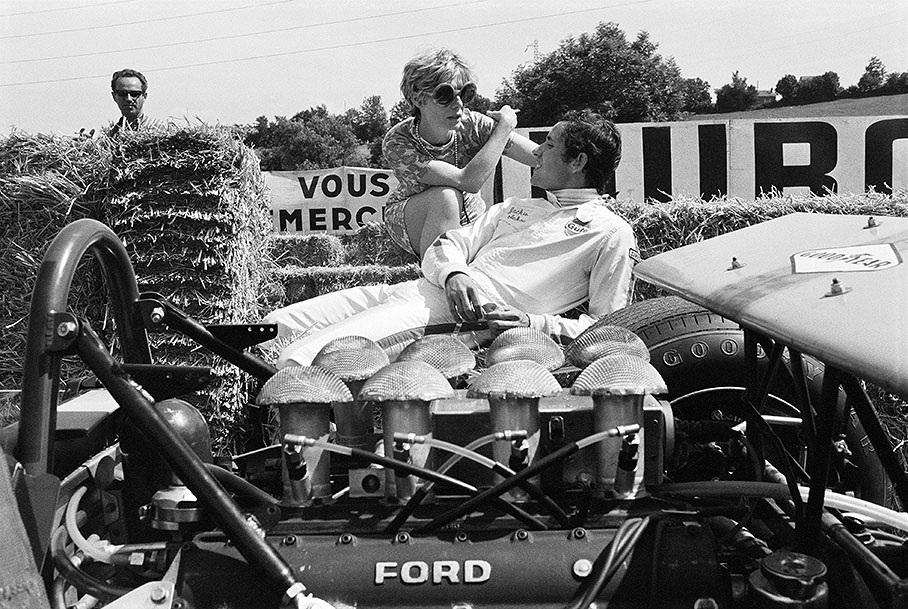

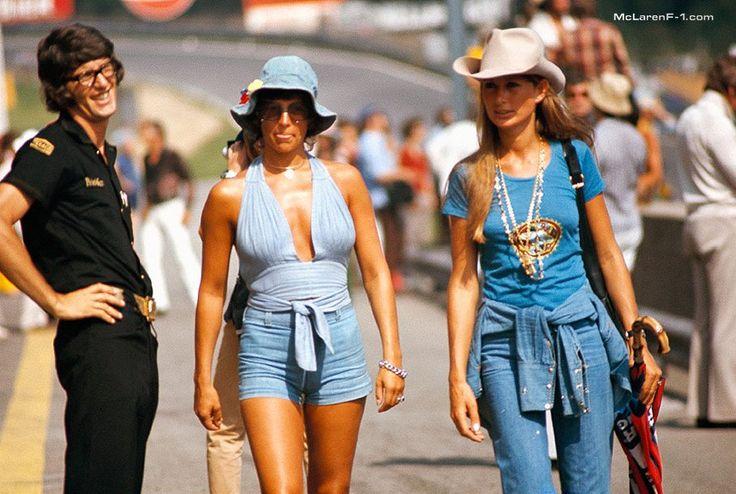

Those drivers, their very often tragic stories, those circuits, those women, that sense of life, that true friendship were amazing.

Rindt, Bruce Mclaren, Denny Hulme, John Surtees and Jacky Ickx.

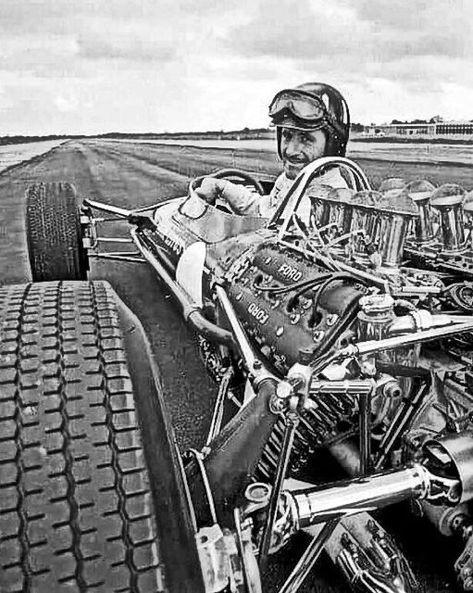

And those magnificent cars, all different and that just looking at them now in photography gives you a shiver of pleasure. Formula 1 was an enchanting, inebriating place, where you could breathe life all in one breath, where you would meet on circuits and at funerals. An earthly paradise on the edge of a ravine. It was celestial music and infinite sadness, it was life in a curve, making fun of fate.

Formula 1, as well as motor racing in general, should never be considered an exciting and competitive sport solely on the basis of the single-seater or the prototype which darts faster than the others and which first crosses the finish line winning the race. It would be simplistic and trivial if the aim would be only the goal for which you win or lose. Formula 1 sport offers much more and passion must be fomented and fueled by details, contours and stories that make beat the hearts of the fans who must treasure all those subtle, magnificent, incredible, often tragic episodies that write history of this sport. Lesser known but still fascinating anecdotes inserted in the historical context and with the social value of the time in which they occurred.

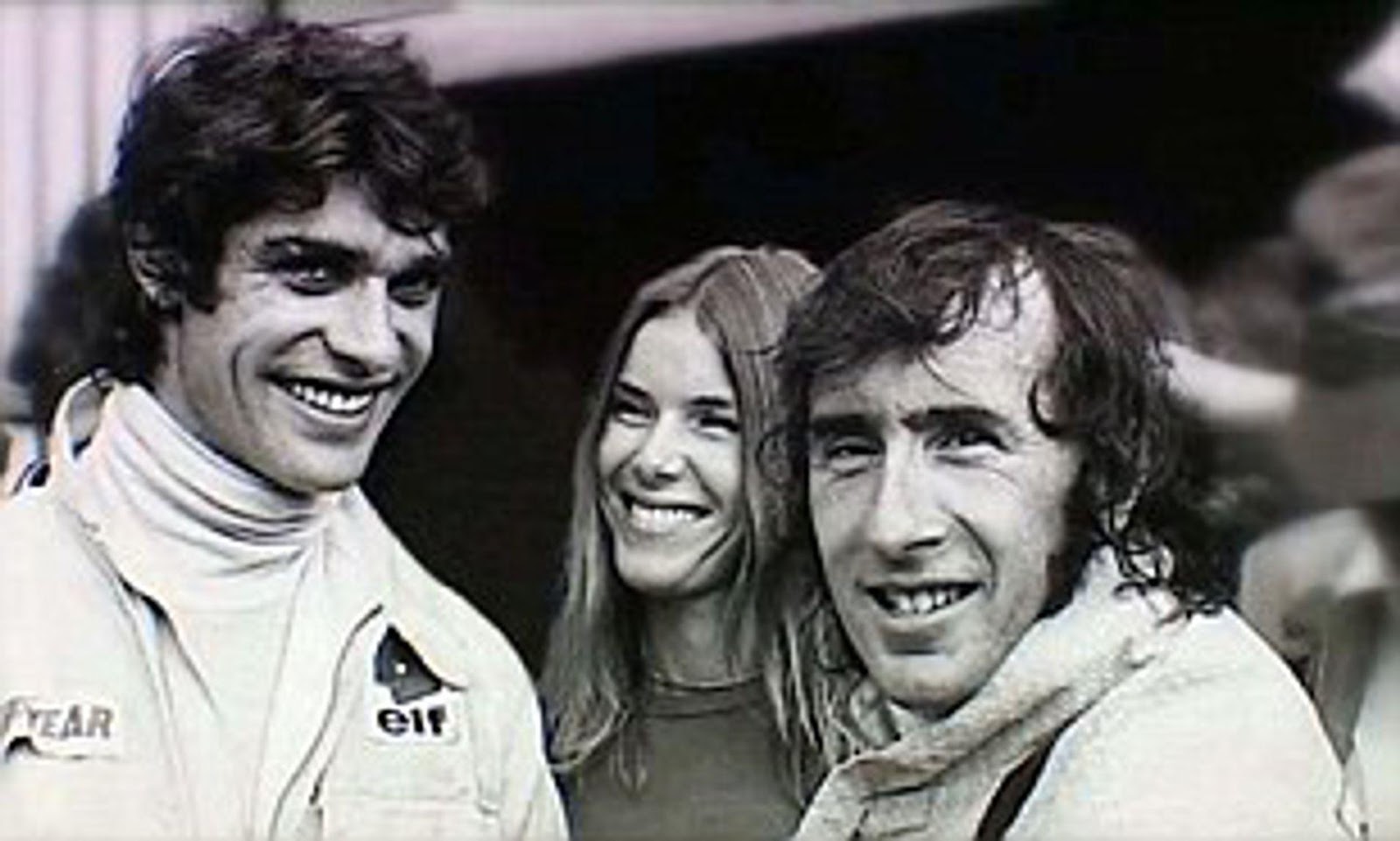

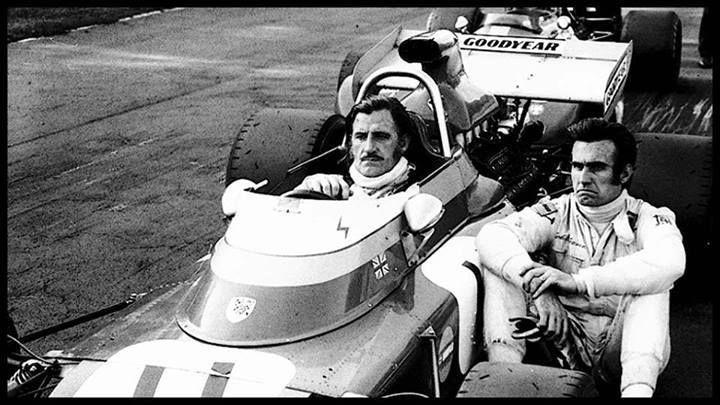

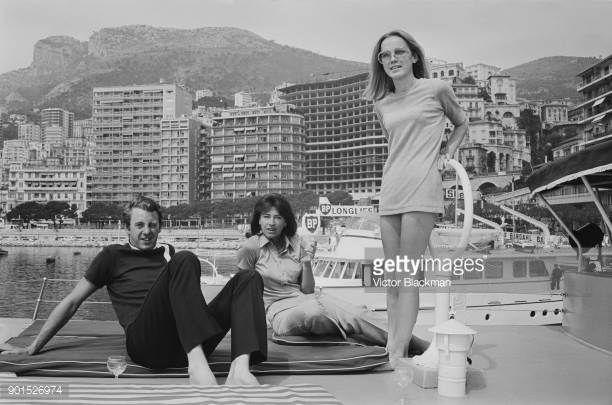

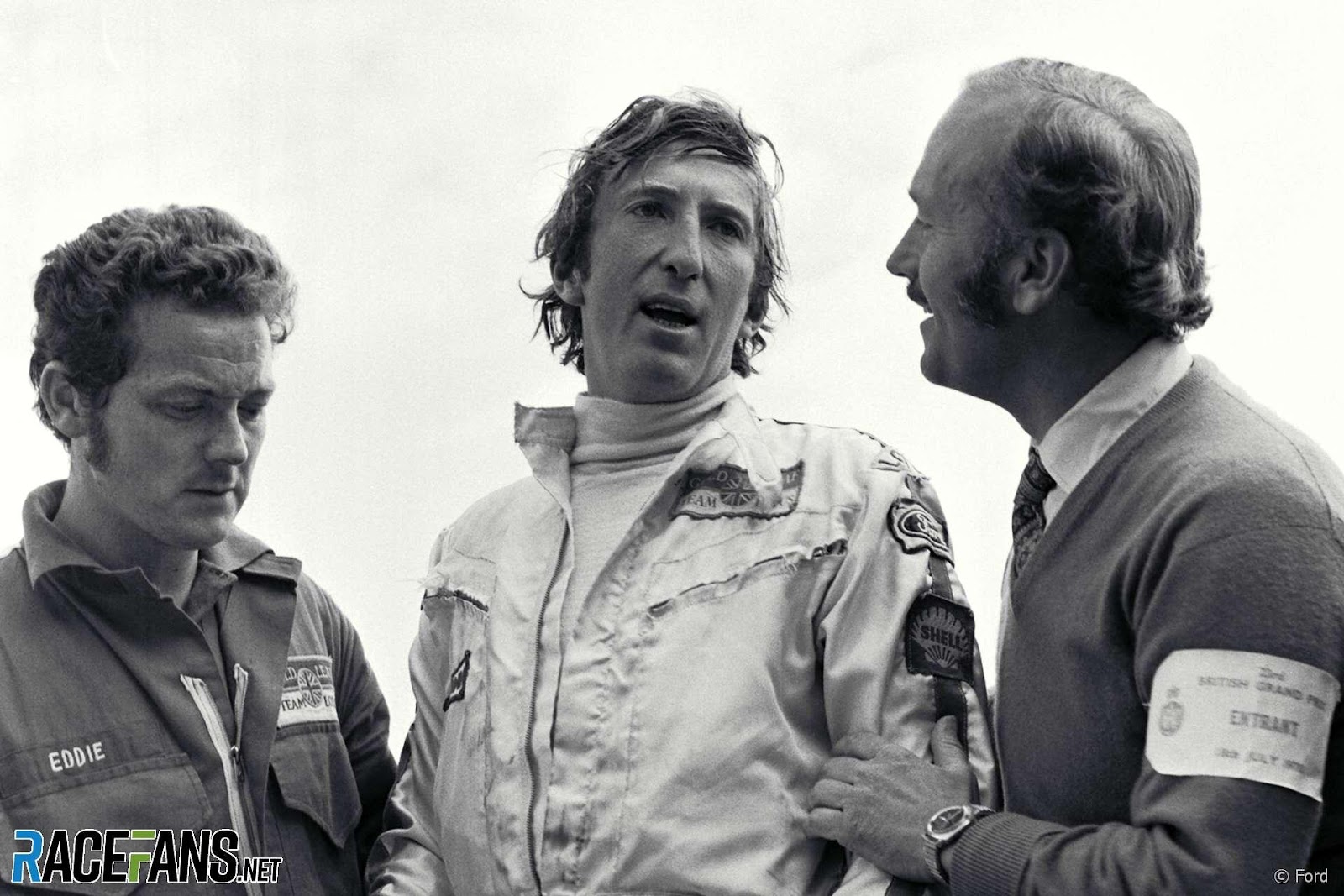

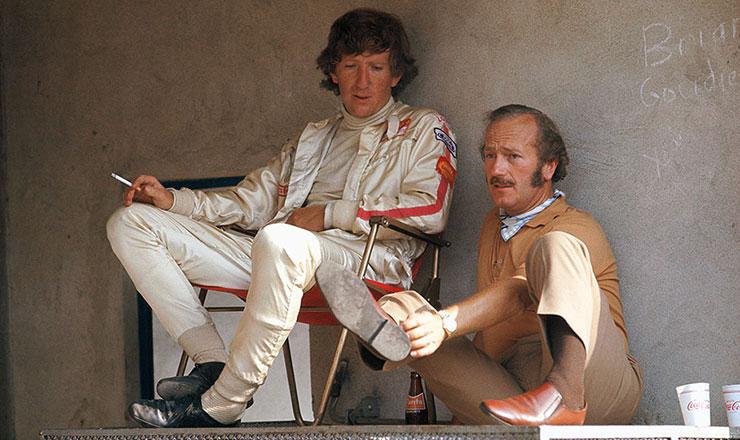

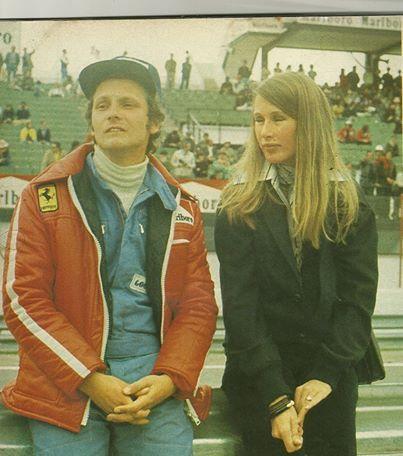

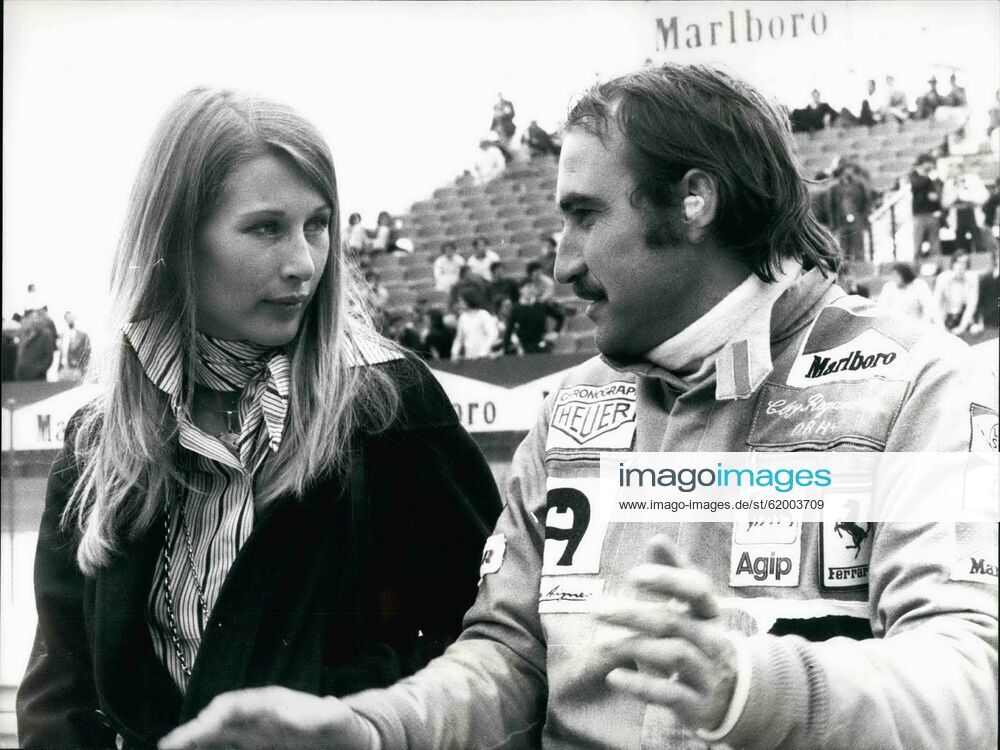

1970. Chris Amon, Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt.

What Jackie Stewart, Graham Hill and Jochen Rindt could think of today's Formula 1 and its virtual evolution could perhaps be summarized in these sentences of Clare Topic, Harvey Postlethwaite's assistant, or so we like to think. “I absolutely agree on the promotion of digital races. I actually do think it is harmful and the result of decisions taken by the promotors to promote a certain view of F1 that it’s all about crashes and smashes. I think this is the number 1 problem with F1 these days. I also think that it devalues the skills of an actual F1 driver, especially when they are racing against non drivers. I suppose the younger generation have a different view of it, but I worry that perceptions of F1 as one of the most physically and mentally demanding sports is getting lost. There are many ways to make F1 more compelling but the will from the management to listen to ideas that are not their own appears to be non existent.”

“F1 is a sensory experience that does get a bit lost on the screen. Most people however will never get to experience a live race so the screen experience has to be good. But in order for the screen experience to be good, the live experience must be much better.”

“I would vary from the view that the new technology takes the emotion out of it. I don’t think that the engineers today are any less dedicated or passionate about their work than they were in the past. I do think there needs to be more room for engineers to express themselves and that the size of teams and the anonymity of the departments detracts from it. The trend is to standardisation and to prescribed parts. It bothers me that they complain about costs and then decide that limiting the suppliers is the way to solve it. It’s the only example I can find where it is believed that less competition reduces the price. The issue is that there is no vision in the current F1, no technical aim. F1 SHOULD be the proving ground for as many new technologies as possible, but this has to be up front. It has to be open and on view. That’s one of the reasons F1 has always been exciting, because when you saw an F1 car, you saw something new, that had never been seen before. Famously, Enzo Ferrari used to literally take a hammer to his race cars after the season ended because the next car was all that was important. Harvey (Postlethwaite) thought the emergence of CAD design tools was fantastic and did not mourn for a moment the passing of drawing with pencil. There never was room for sentimentality in the design office.”

“The current management give the impression that they don’t really care that much for the engineering. Their focus is to increase revenue. They might be happier running an eSport series than a real one. The budget cap they have introduced to F1 will backfire spectacularly. It is actually the end.”

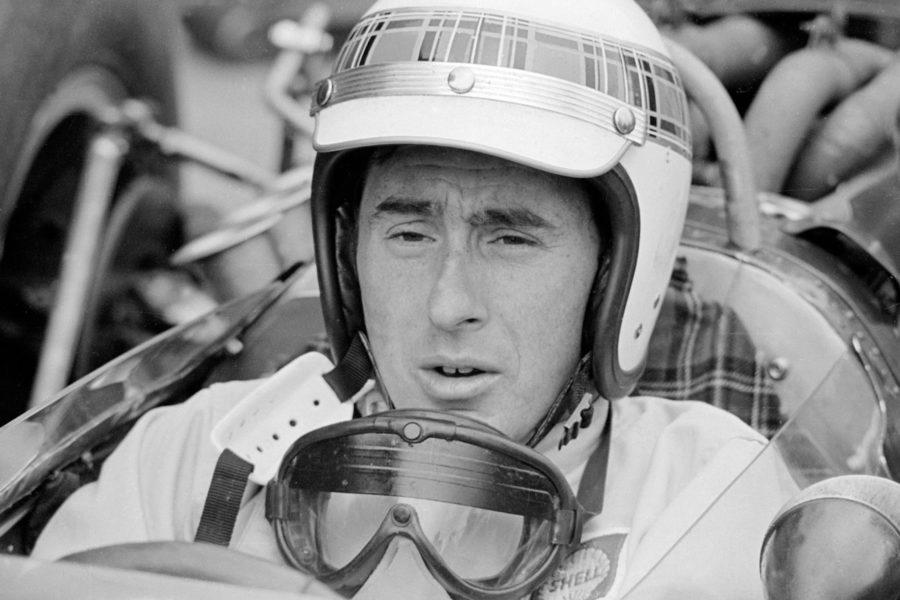

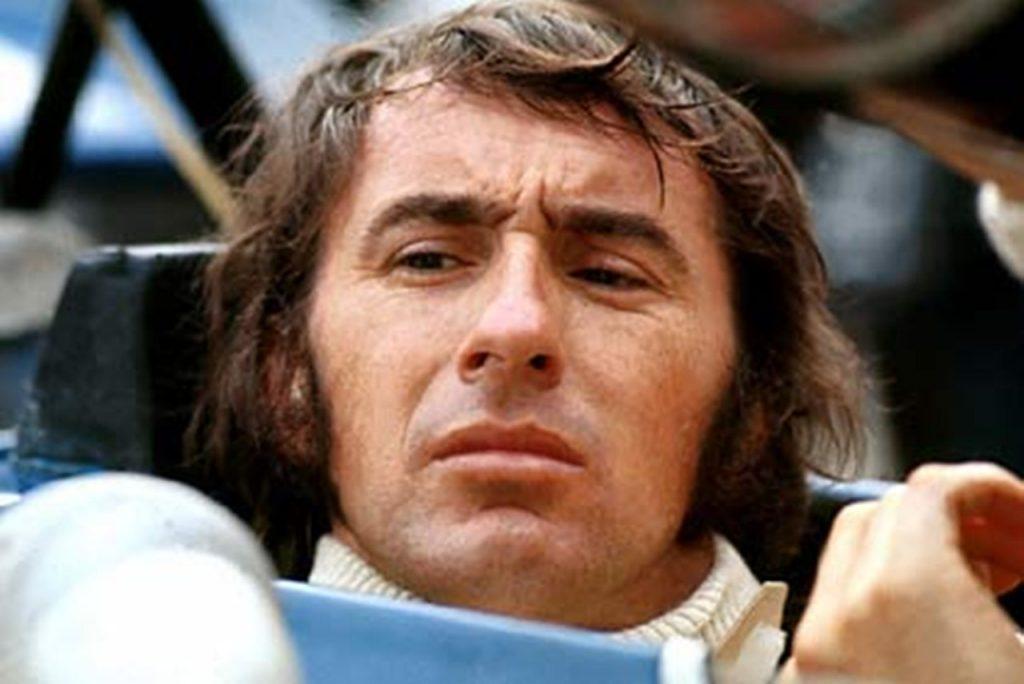

Jackie Stewart

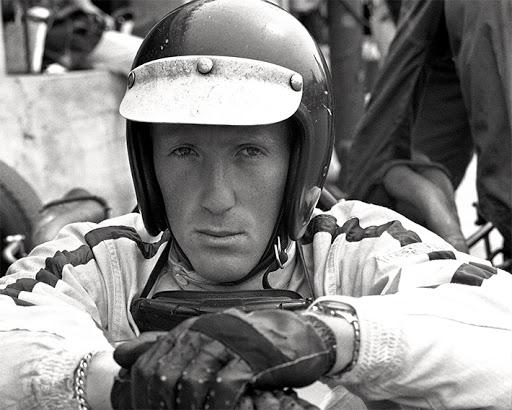

Until 1968 there was only one “flying Scotsman”, Jim Clark, then the nickname passed to Jackie Stewart.

One of the greatest, Jackie and who can tell it.

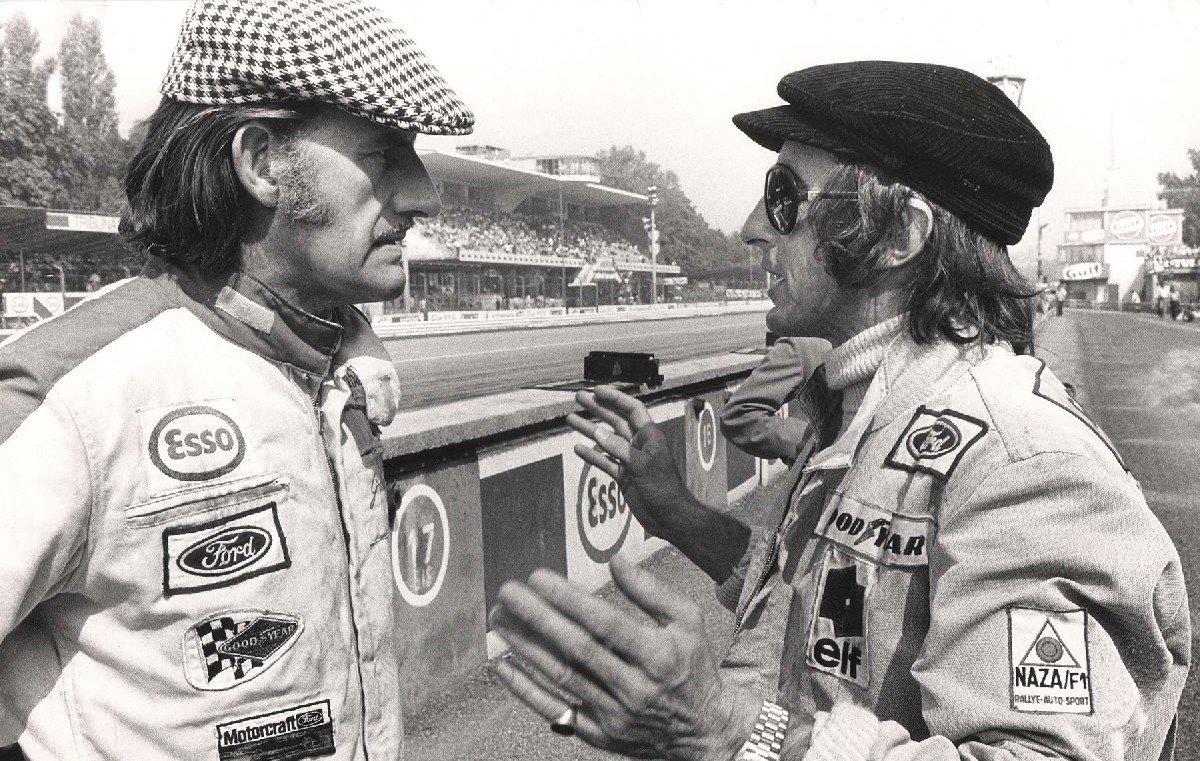

Jackie Stewart and Alain Prost.

He was a Prost-style reasoner, a championships man and was preparing the car with extreme care.

Stewart was practicing smooth driving by avoiding an orange that he had placed on the front hood of his car to drop.

Sensitive to money - as they say of the Scottish people - and for this reason he did not drive a Ferrari. He asked too much and the Drake shut the door.

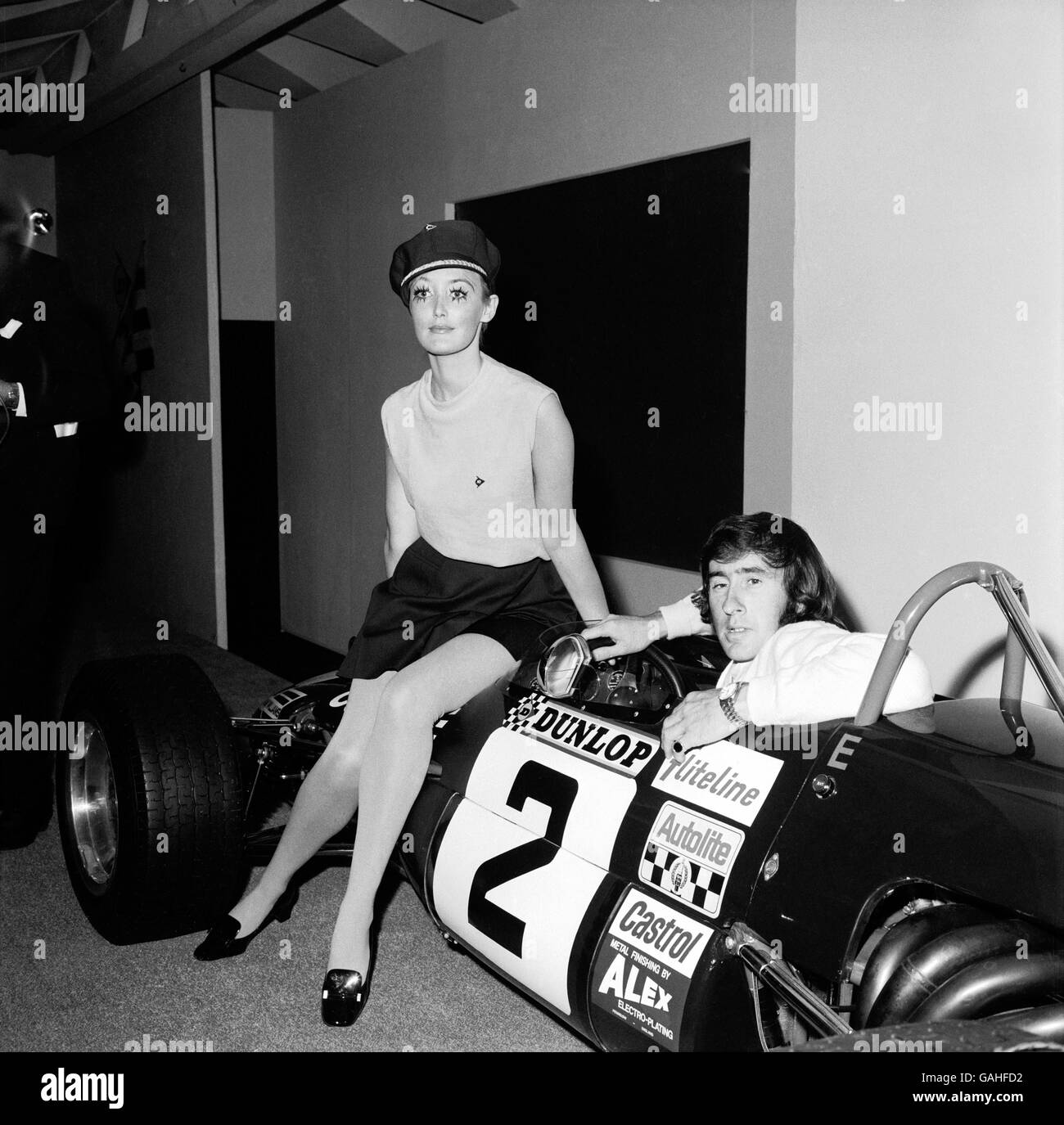

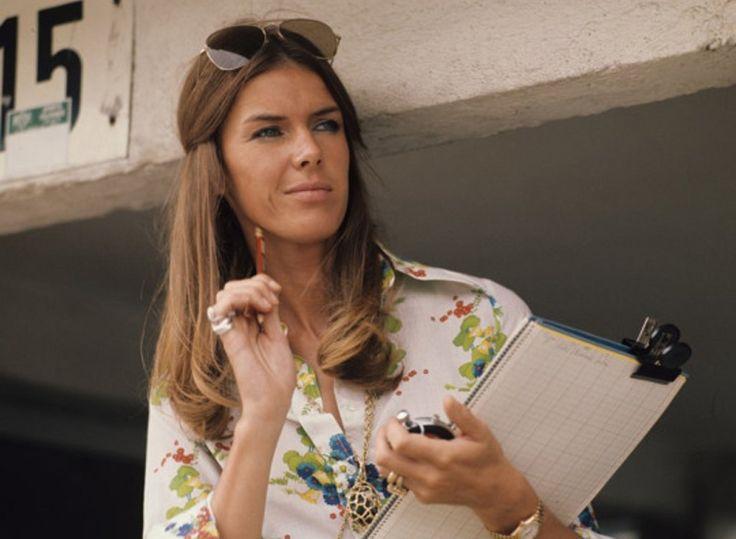

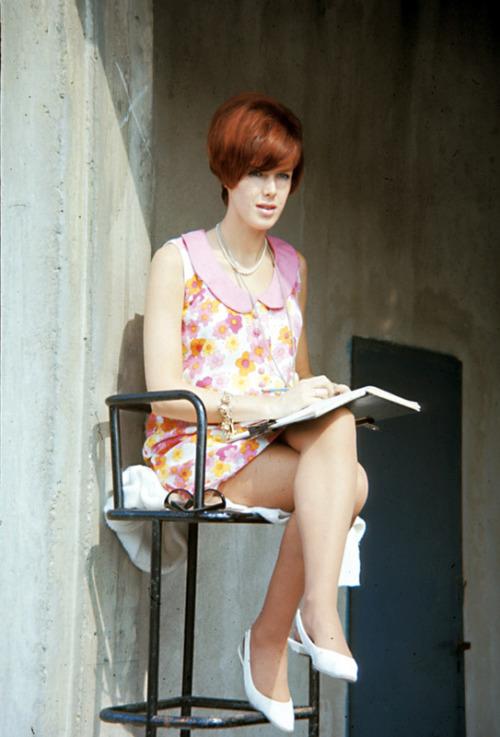

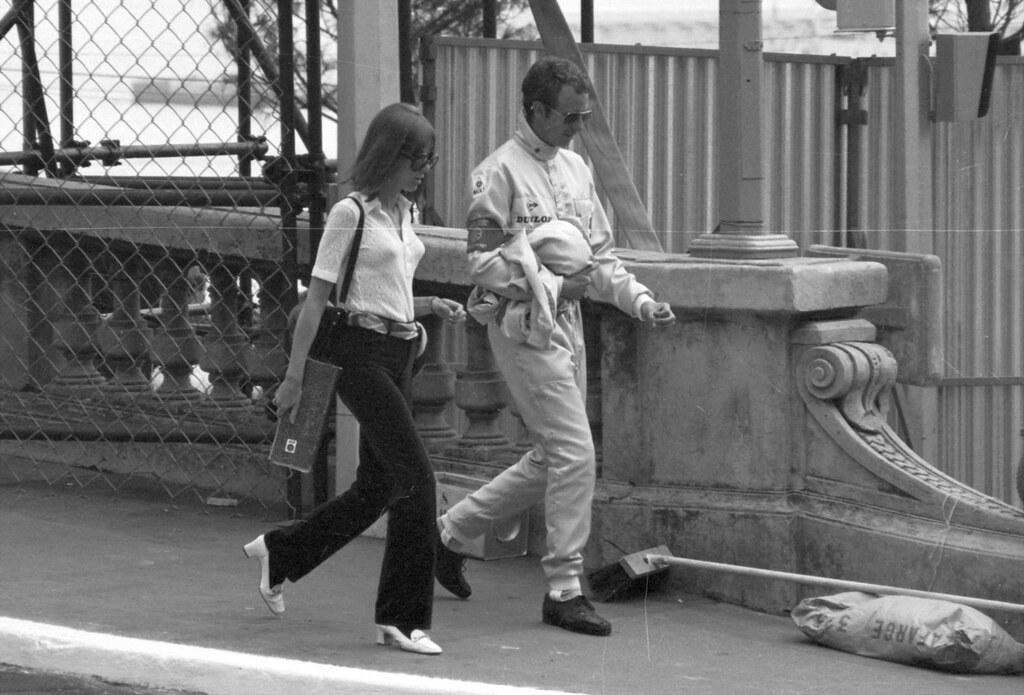

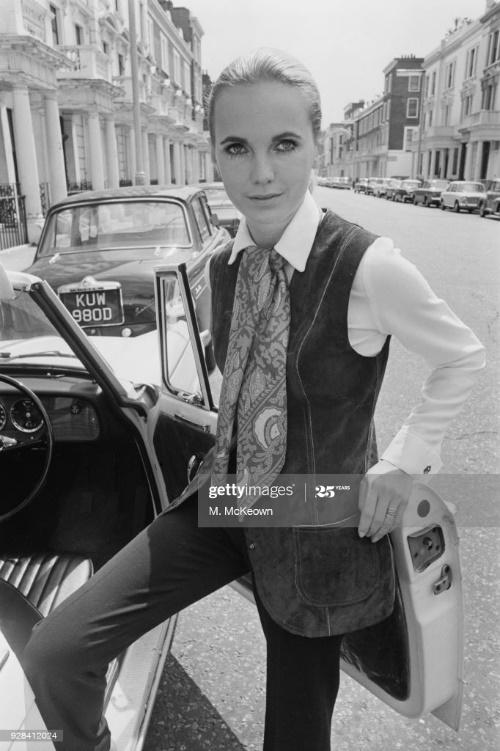

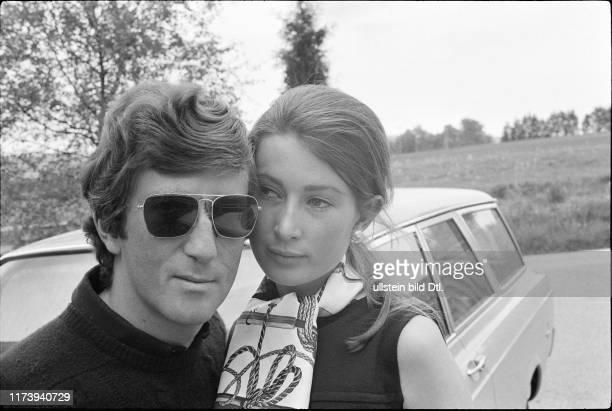

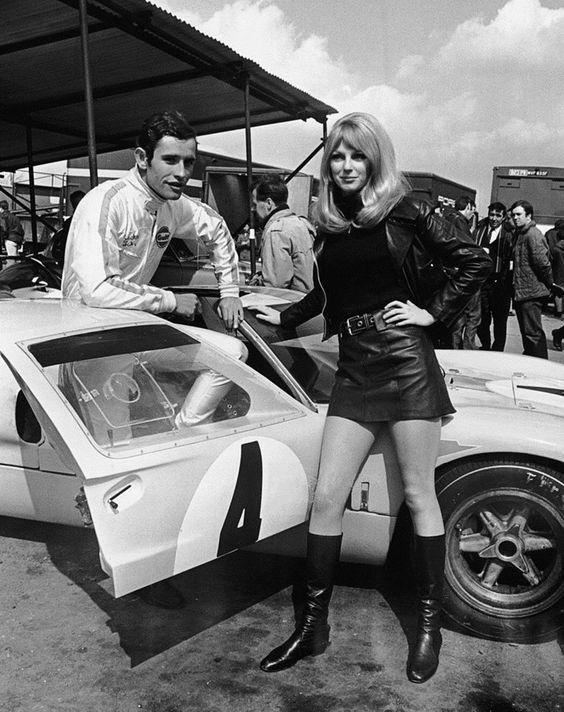

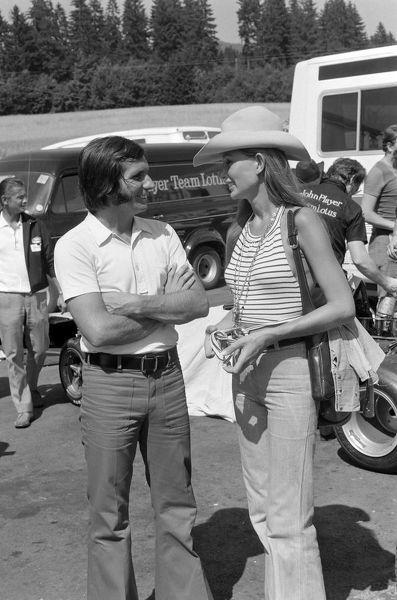

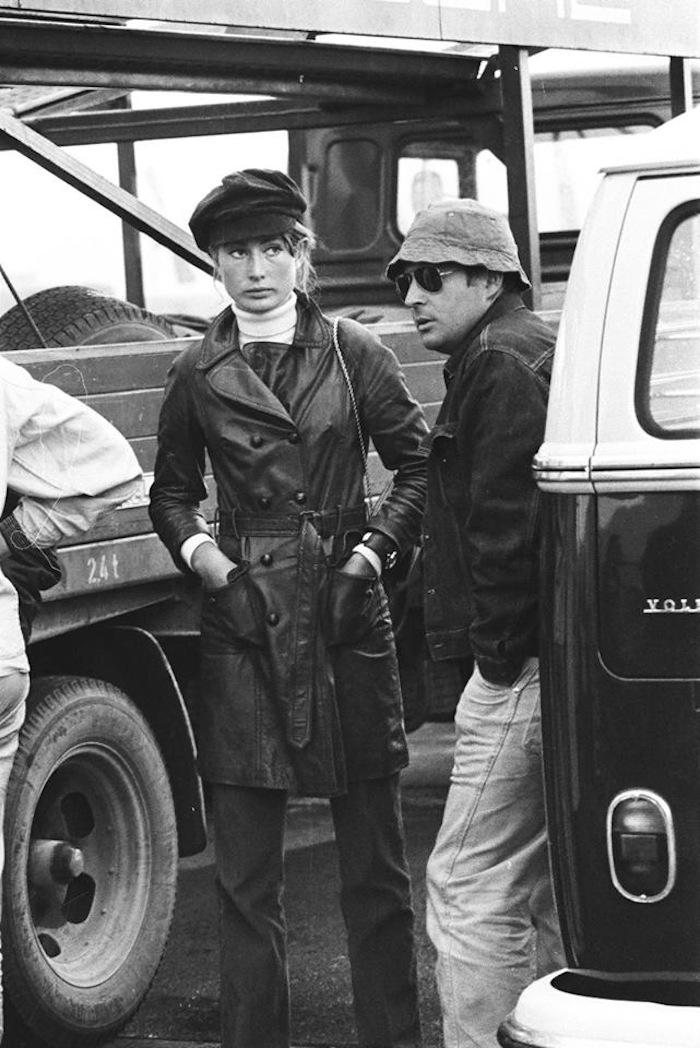

Jackie Stewart with a model.

Jackie Stewart is joined by a model to advertise Dunlop tyres in London in 1969.

Jackie Stewart is joined by a model to advertise Dunlop tyres in London in 1969.

He enjoyed the swinging 60s and 70s behind the wheel of a yellow De Tomaso Pantera, living in the beautiful Switzerland of the time with a wonderful wife who had always been by his side. As brilliant as a business man as much as he had been as a driver ("he was a great driver and, as a business man, even better," Ken Tyrrell said), Jackie Stewart inherited the leadership of Formula 1 from Jim Clark.

“Colin Chapman and Jim Clark was in history probably the best combination it has ever been.” Jackie Stewart.

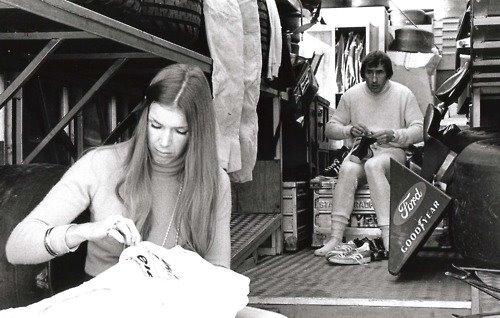

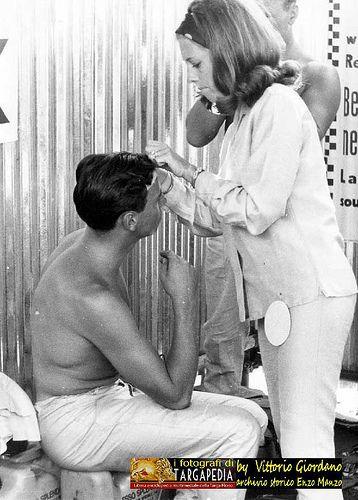

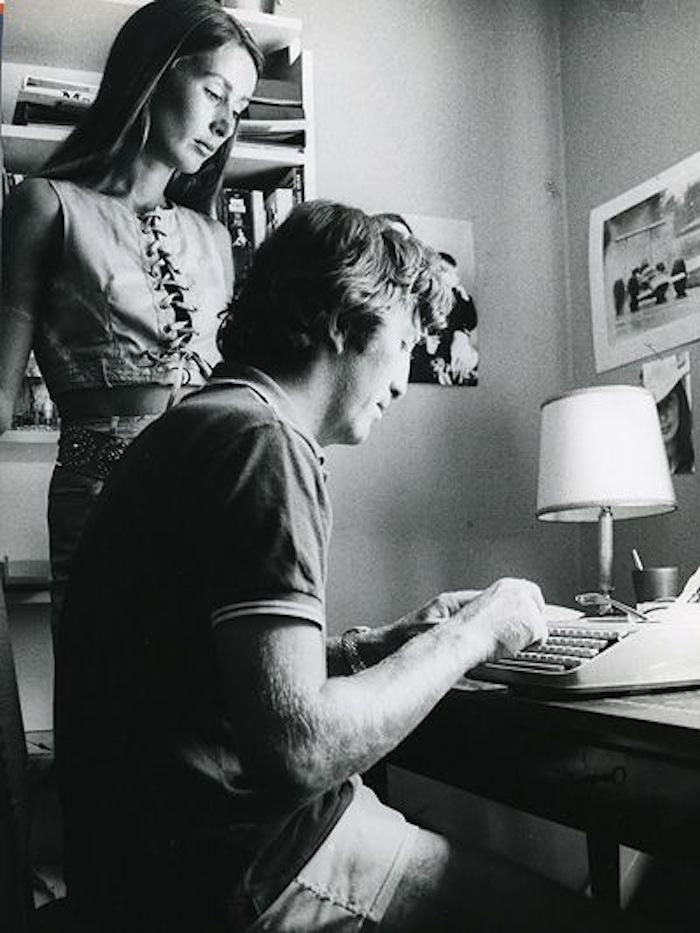

The lovely Helen Stewart sews new sponsor badges onto Jackie’s overalls, whilst Jackie fiddles about with shoelaces and models fireproof undies for us. Source: facebook.com.

“Helen never asked me to retire.” Jackie Stewart, talking about how strong his wife was, facing so many deaths in that period.

The good, the bad, the ugly: Sir Jackie Stewart. June 5, 2020.

A triple World Champ, Sir Jackie Stewart acknowledges his stand on driver safety didn’t make him the most loved champ, however his ability on the track definitely made him one of the most successful.

Zandvoort 1969.

In his nine years racing in Formula 1, Stewart won 27 Grands Prix, took 43 podiums from 99 starts and achieved three Drivers’ Championship titles.

He went out on top, winning the title in his final season in Formula 1, but never took the start grid in what would have been his very last Grand Prix.

Stewart’s team-mate, Francois Cevert, was killed in a qualifying crash at Watkins Glen, cementing Stewart’s position as an advocate for improved safety in Formula 1 racing.

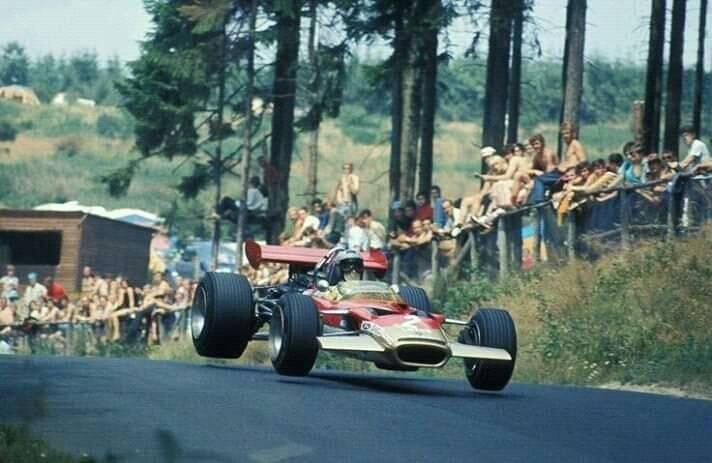

Good: 1968 German GP.

Despite sporting a painful wrist injury, the result of a broken scaphoid bone thanks to a Formula 2 practice accident at Jarama, Stewart was invisible around the Nürburgring at the 1968 German Grand Prix.

The race weekend took place in extremely wet and foggy conditions with the Ferraris of Jacky Ickx and Chris Amon qualifying 1-2.

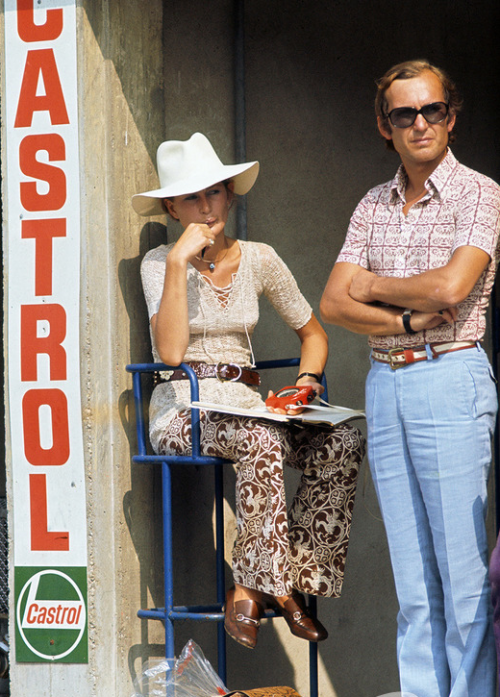

Jacky Ickx and his wife Catherine on the Monza circuit in Italy.

Jacky Ickx and Catherine.

Ickx took pole by 10 seconds while Stewart, driving the Ken Tyrrell-entered Matra-Cosworth MS1, qualified sixth.

It was, however, the Brit who emerged victorious on the Sunday.

The race start was delayed by 50 minutes but, with the conditions worsening, a decision was taken to start before it became impossible. Some would argue it already was given that the track surface was icy cold, wet and supremely treacherous.

Graham Hill shot past the Ferraris to lead the race only to be overtaken by Stewart before the end of the opening lap.

Stewart immediately set about building up a lead as his Dunlop wet tyres proved to be superior to its Firestone rivals and he stuck to the track.

Jackie Stewart at Nurburgring in 1968.

Running away from the competition, he was up to 34 seconds after lap two and, when the race was called at the end of the 14th lap, was a massive four minutes ahead of second placed Hill.

Stewart’s drive is still considered today to be one of the greatest in Formula 1’s history.

Bad: 1966 Belgian GP.

Starting third at the Belgian Grand Prix, Stewart was one of nine drivers that did not make it through the first lap.

Although the race started on a dry track, a torrential downpour hit the Spa-Francorchamps circuit halfway through the opening lap, resulting in Stewart – driving at 266 km/h – aquaplaning off the track and crashing into a telephone pole. From there he hit a farmer’s shed before eventually coming to a halt in an outbuilding.

With his steering column pinning his leg, Stewart was unable to exit the car and was being drenched in fuel as his fuel tank had ruptured.

Compounding the danger, there wasn’t a marshal in sight.

“First I hit a telegraph pole and then a woodcutter’s cottage and I finished up in the outside basement of a farm building. The car ended up shaped like a banana and I was still trapped inside it,” he told the Guardian.

“The fuel tank had totally ruptured inwardly and the monocoque literally filled up with fuel. It was sloshing around in the cockpit. The instrument panel was smashed, ripped off and found 200 metres from the car but the electric fuel pump was still working away. The steering wheel wouldn’t come off and I couldn’t get out.”

Never one to celebrate another’s crash, Stewart was blessed when two other drivers, Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant, slid off the track close to his accident site and rushed to his aid.

Hill switched off the fuel pump but they were all still in danger from the fuel covering the area.

The Brit was eventually taken by ambulance to the track’s medical centre only to be placed on the floor.

“There were no doctors,” he recalled. “I was left on a stretcher, on the floor, surrounded by cigarette ends. It was filthy.”

His ordeal was by no means over as while another ambulance came to take him to the hospital, the driver got lost on the way. He was finally flown by private jet to the UK for medical treatment.

Aside from his leg injury, Stewart suffered broken ribs and a shoulder injury.

Ugly: 1973 Watkins Glen.

Having decided he would retire at the end of the 1973 season, Stewart went out on top, claiming the Drivers’ Championship title at the Italian Grand Prix.

He wrapped up the crown, his third, with two races to spare.

With the title in the bag, he finished fifth in Canada before moving onto the United States’ Watkins Glen for what would have been his final Grand Prix. It would also have been his 100th start.

The death of Francois Cevert changed that.

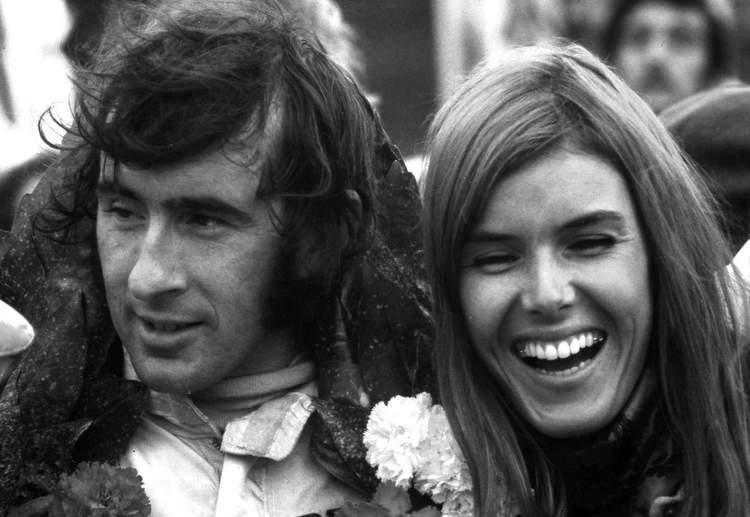

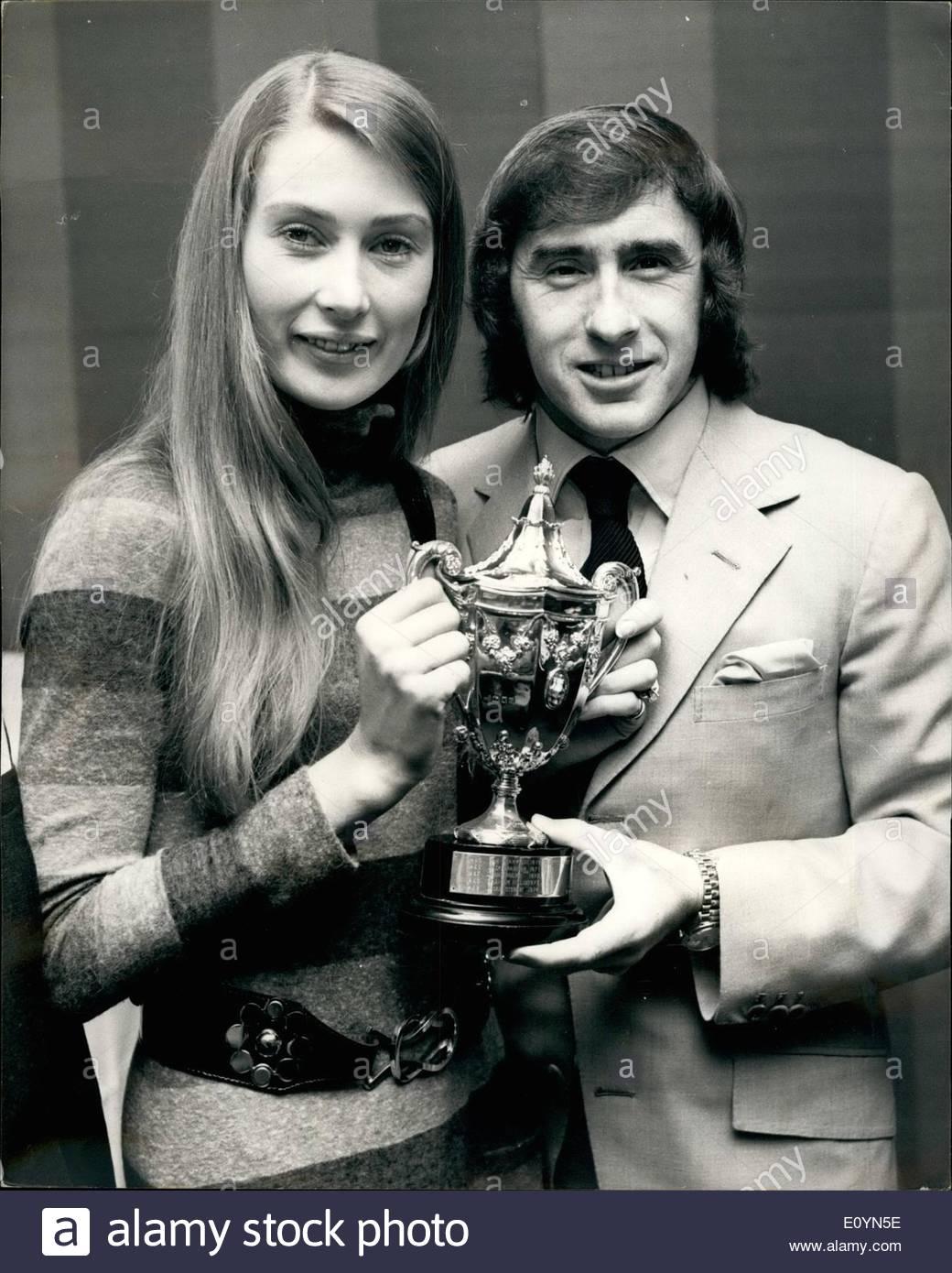

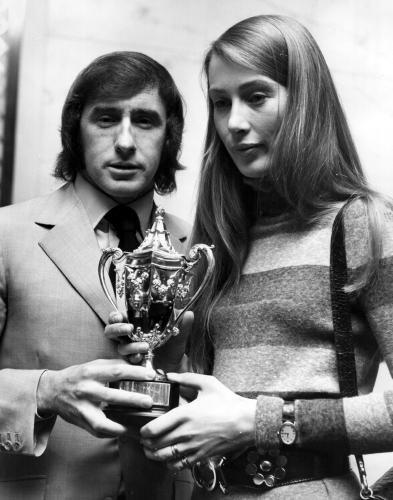

Francois Cevert, Helen and Jackie Stewart.

Helen Stewart and Francois Cevert.

Out on track in the Saturday qualifying, Stewart’s Tyrrell team-mate Cevert crashed violently when he lost control after taking too much kerb.

“On the Saturday of what would have been my 100th and final Grand Prix, my team-mate Francois Cevert was killed in front of us drivers,” Stewart recalled. “The accident occurred at a very quick part of the race track.”

“The amount of debris on the circuit was enormous. I thought, my God, what a huge accident. The yellow flags were out, all the cars had to stop because the debris was so extreme on the track.”

“Every driver had obviously got out of their car and had gone to see if they could help and I was the last to arrive. So I got out of my car and went over to where the rest of the car was.”

“It was a terrible sight and Francois was equally in terrible shape. It was obvious that he was already dead.”

Stewart returned to the pits and withdrew from the Grand Prix weekend.

He never competed again. “It was a decision I have never ever regretted. I never wanted to drive a racing car again,” he said.

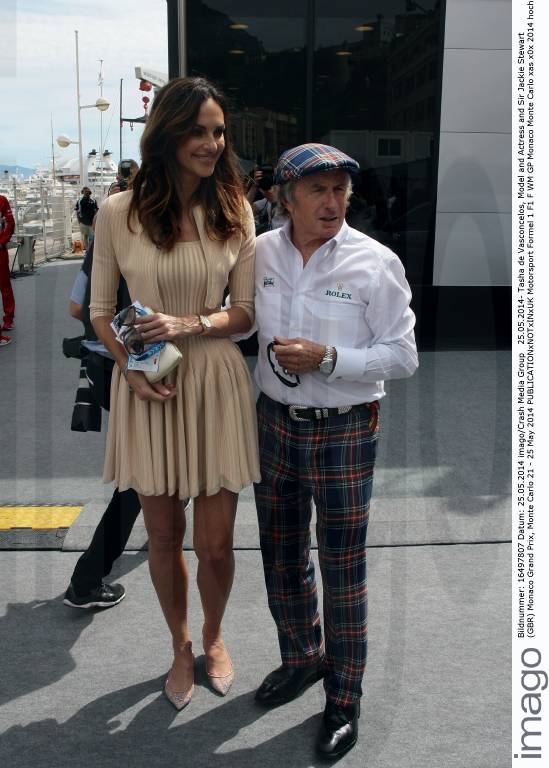

Tasha de Vasconcelos, model and actress, with Jackie Stewart at Monaco Grand Prix on Sunday 25th May 2014.

Tasha de Vasconcelos, model and actress, with Jackie Stewart at Monaco Grand Prix on Sunday 25th May 2014.

Sir Jackie Stewart with HRH The Countess of Wessex. Picture by Phil Wilkinson.

Interview: Sir Jackie Stewart: ‘there’s no difference between Stirling Moss and Lewis Hamilton.’

The motoring legends talks safety, crowds and crashing with Gentleman's Journal.

The noise is just deafening, the smell of unburnt fuel stings your nostrils and the feel of a V8 engine revving, reverberates through your rib cage and into your heart. Add to that a hefty dose of adrenaline and trepidation and you’ll be somewhere close to what F1 veteran Sir Jackie Stewart felt 50 years ago, on the start line of the 1966 Monaco Grand Prix.

Just 21 days later, after the euphoria of crossing the finish line first in Monaco harbour had subsided, there was a very different feeling in the air. On lap one of Spa-Francorchamps, during the Belgian Grand Prix, a sudden downpour resulted in Stewart’s car crashing and overturning, trapping him upside down in the car, with fuel gushing into the cockpit.

The experience and appalling response from the authorities were enough to spark his global campaign – against popular demand – to drastically improve the safety of motorsport. Half a century on, we speak to the man behind modern motorsport.

-

For you, where did your career in motorsport start? What were the main influences?

Well, my brother was a racing driver called Jimmy Stewart. He used to race for Ecurie Ecosse but he only did one F1 race in 1953 – he had an accident with five laps to go! When he was driving, I was only 14 but I still have an autograph book with all the drivers from the time’s signatures. I never thought I’d be a racing driver – I didn’t think my family had the money, especially after putting one son through it already.

So I took up shooting – clay shooting, that is – and I was quite successful at it. I represented Scotland and twice won the European Championships.

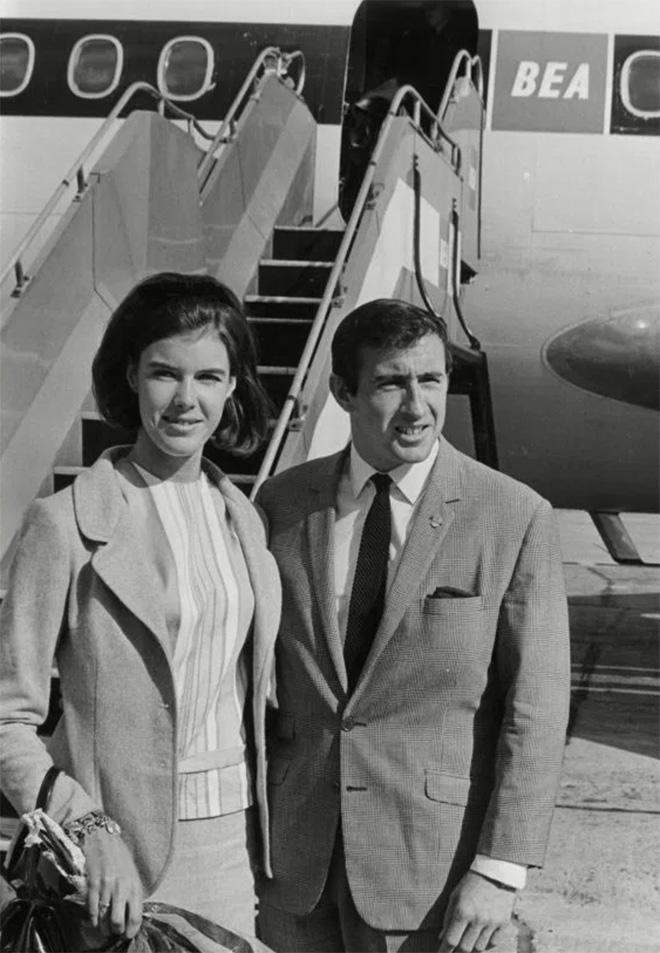

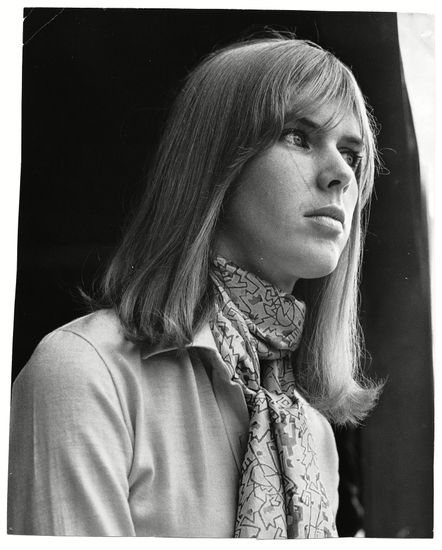

Helen and Jackie Stewart.

That was what my whole life was at that time but I stopped when I was 23, which is when I married my wife Helen. At the time, for me, motorsport was just reading “Autosport” magazine!

But my father had a small garage, with around seven employees. There was a very well off man from Glasgow – one of our clients – who had some very nice cars. But his family didn’t want him to race them as he was the only heir to the estate, so he got other people to drive them to the track and then get in and do the job! As a reward one day, in the early 1960s, he let me have a go and I came second. So he let me have another go and that time I came first. After that, I got my first contract and then came my first win in 1964 in Formula 3. I remember in one year I drove 26 different racing cars – that’s just what you did back then. My first Formula 1 race, however, came in 1965 when I signed with BRM.

-

You were instrumental in changing Formula 1 to make it safer. Why did it need to change?

There’s an ugly side to motorsport and that’s when a colleague dies. We would all go to the memorial service – our wives and our families. Our wives played a huge part in F1.

Helen Stewart la belle.

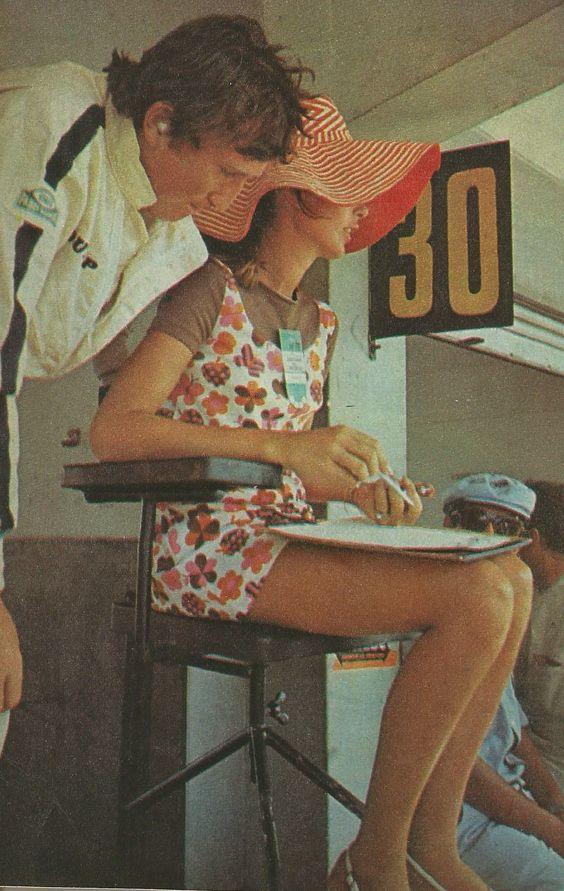

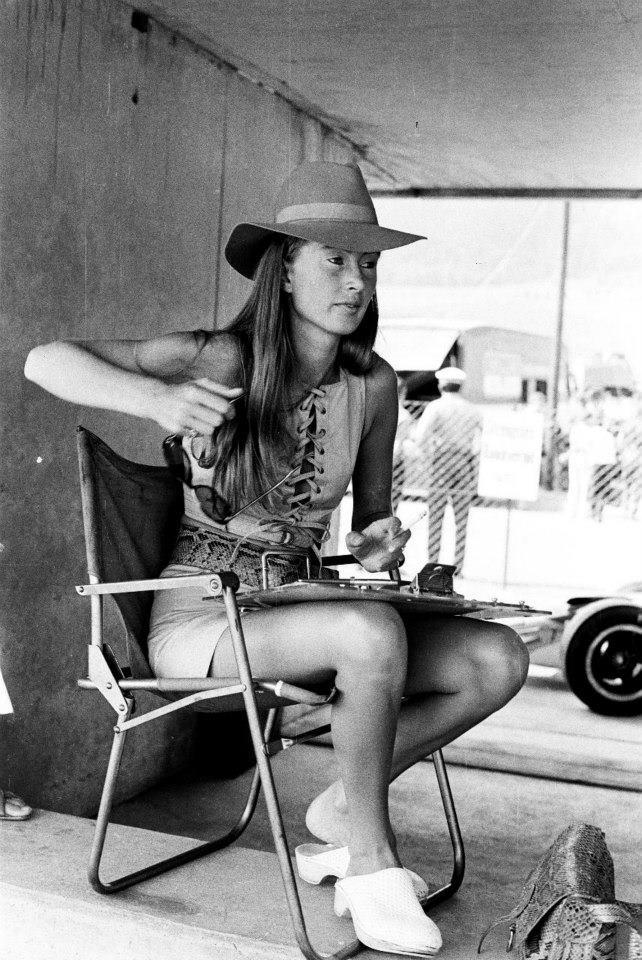

Helen would be time keeping at the side of the track but the problem was, when there was an accident, it affected everyone. We were seeing it on a regular basis.

Jackie Stewart and Jim-Clark wearing racing rain coats in 60s.

In April 1968, Jim Clark was killed. Exactly one month later, Mike Spence was killed. Another month on, almost to the day, Ludovico Scarfiotti was killed, followed by Jo Schlesser another month on from that. Four drivers had died in four months. It was ridiculous – you couldn’t afford to make mistakes. The tracks hadn’t changed but the cars most certainly had – they’d got so much faster. There was no run off areas between the track and concrete walls.

We often had to drive through the flames of crashed cars – in those days the fuel tanks were explosive – it was before the days of flame protection. But make no mistake, motor racing will never be safe – it even says it on the back of the ticket but it’s better than it’s ever been today.

-

What challenges did you come up against?

Oh, there was serious opposition and a lot of, ‘if the kitchen’s too hot, why don’t you get out.’ I was very unpopular, especially when I closed the Nürburgring! 375,000 people used to come to that area of Germany for the race – it was an essential part of the local economy. There were 187 corners per lap – it’s the greatest challenge in the world as a racing driver but that doesn’t mean it’s safe.

If we’d allowed the Nürburgring to stay open, we’d have not managed to get other tracks to change. We also closed Spa.

If there was a popularity contest, I wouldn’t have won it but I could do that because I was three times World Champion! Now F1 has no place on ‘the green hell’ – it was me who coined that phrase in 1968 when I won it in fog and rain by four minutes. You wouldn’t have even been allowed to start in conditions like that now.

-

Some refer to the period you raced in as the golden age while others say they were the killer years. Which is a more accurate description?

If you take death and serious injury into it, then you can’t say it’s the right thing. But if you examine the camaraderie and the community, then it’s nothing like it was back then. But then again, the unity was in the face of death… they’re ‘bad old days’ as far as I’m concerned. Racing drivers have the ability to blank off risk – we’d go to a funeral on Wednesday and a race on Saturday. There’s a huge relationship that existed but that’s not to say that it was better than today.

-

How was Formula 1 perceived in the 1960s?

Well, the crowds were bigger. There was TV but no satellites or cable. Everyone knew the leader of the pack in those days and that was often Jim Clark – he was unquestionably the best driver of the time until he was killed in 1968. Print was the big medium back then, not TV. Despite his fame, no one had heard Jim Clark’s voice, for example. I’d say I led the commercial side of the sport. Rolex picked me up the year before I won the championship and now I’ve been with them for 68 years. I was with Ford for 40 years and Moët & Chandon for 47 years. They’re like family to me.

-

What original parts of the sport remained from when you first started out?

It has and it hasn’t – it’s still the same animal. I don’t think there’s much difference between the drivers now – I see three standout drivers: Alonso, Vettel, and Hamilton. You see there’s no difference between Hamilton and Stirling Moss in their mindset but they’re not as rounded as they were.

I would go to Indianapolis to race in between driving in F1. Now, they just don’t do that. If anything, it’s the technology that’s really changed the sport the most. With all that’s been done for safety, for example, the driver sits in what is basically a cocoon. Back in the day, there was a two-thirds chance I would have been killed. Racing was still glamorous and exciting as it is now but the risk was much, much greater.

-

Finally, what qualities does it take to be an F1 driver?

-

Mind management – much of it is God-given, but you can develop it.

-

Natural ability is essential, but how you massage it is down to the person.

-

And, ideally, average height!

Jackie Stewart the giant. February 16, 2017.

If you write about F1, it's not nice to talk about favourite drivers, but sometimes you have to unbutton yourself. Mine - without a doubt - is Sir John Young "Jackie" Stewart.

Jackie Stewart in a Tyrrell 003 at Silverstone.

I was lucky enough to know him well thanks to Ford that, for the launch of the Sierra Cosworth, organized a long weekend in Silverstone where precisely Stewart revealed the secrets of his driving. Of how you always had to "race" going slowly, without ever stressing the car to the limit. "It is fundamental - he explained - to think of the car as it will be in 10 laps, 20, 30 and to the finish line. You don't race to find the limit but to keep the mechanics, to get in front of everyone under the checkered flag."

Of course, looking at this terrifying photo taken at the Nurburgring with the 4 wheels of his F1 fully raised under a flood, it is difficult to think that Jackie was going "slowly" there. Yet evidently he still had a margin, very small, but he had. But don't ask me how much...

And then Stewart was also unique in how he prepared the races, how he studied the atmospheric pressure, surrounded by ubiquitous barometers (he gave one to me...) because by measuring the atmospheric pressure, the humidity in the days before the race, he could predict how he would have found himself racing.

Jackie Stewart. June 11, 2019.

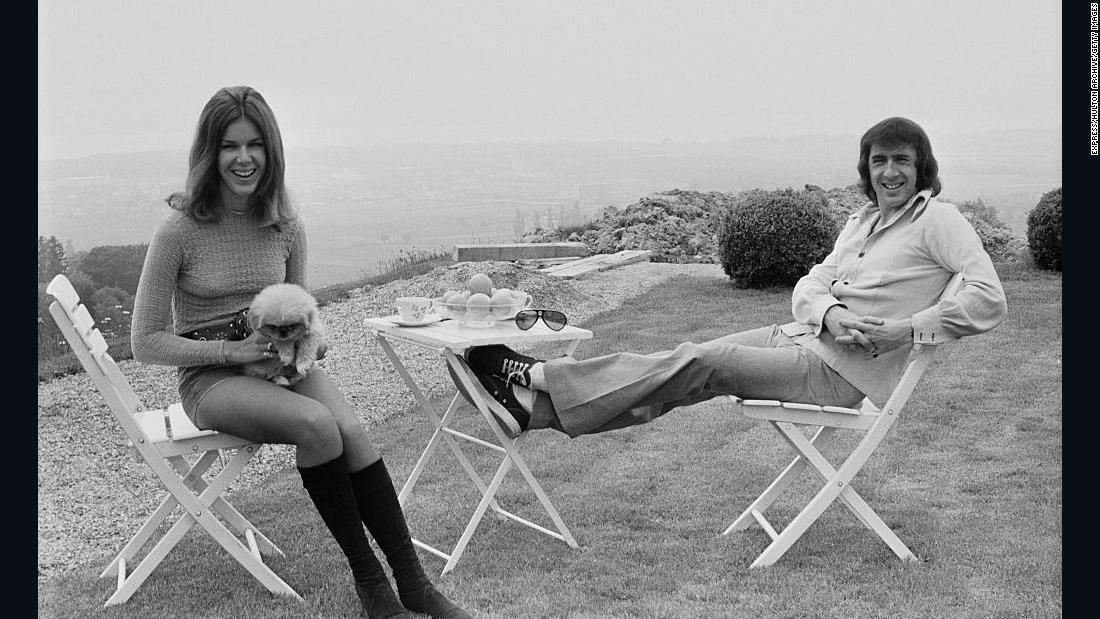

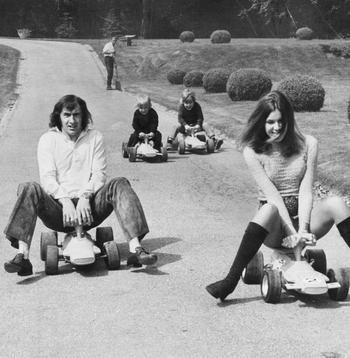

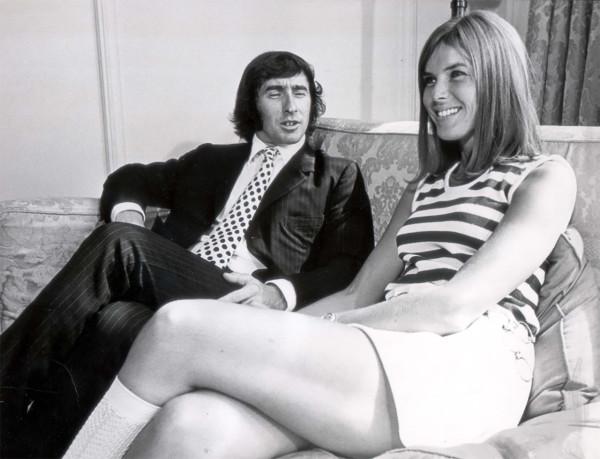

Jackie and Helen Stewart.

His outstanding track record still ranks him among the most successful champions, yet in terms of personally influencing the way Formula 1 racing developed Jackie Stewart stands alone. His one-man safety crusade made the sport much safer. His excellent communication skills helped make it more popular. He set new standards of professionalism for drivers and was also a pioneer in exploiting Formula 1 racing's commercial potential. His keen intelligence and tireless energy helped, but he would never have been able to exert such influence had he not been a truly great driver.

Nurburgring, August 1966: Jackie Stewart takes to the air in his BRM during the German Grand Prix. He would finish fifth behind team mate Graham Hill. Photo by Schlegelmilch.

Jackie and Helen Stewart.

John Young 'Jackie' Stewart was born in Dumbartonshire, Scotland, on June 11, 1939. Jackie's older brother Jimmy was the first in the family to try racing, though his mother disapproved. There were also fears about Jackie's future because he was a failure at school and left at 15. Only later was he diagnosed as suffering from severe dyslexia - which made his subsequent achievements even more remarkable. When he began racing saloons and sportscars he quickly showed outstanding talent that prompted team entrant Ken Tyrrell to hire him to contest the 1963 British Formula 3 series, in which the speedy Scot won seven races in a row.

Jackie Stewart (we think) during the 1965 Monaco Grand Prix.

In 1965 he joined the BRM Formula 1 team and stayed there for three seasons, winning two Grands Prix and firmly establishing himself as a frontrunner.

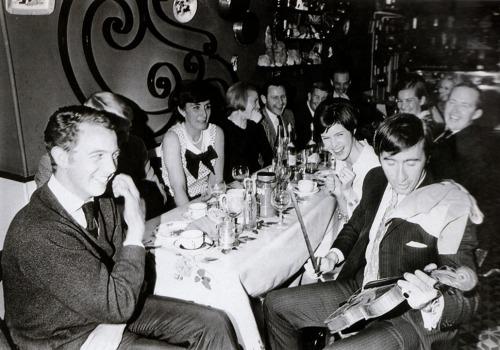

Jackie getting up to some violin antics in Monaco, 1968. No, Jackie, it doesn’t go there. Piers Courage is finding the whole thing very amusing. Note how both Jackie and Piers have managed to get their hair to stay flat for the evening.

In 1968, when Ken Tyrrell decided to go Formula 1 racing, Stewart teamed up with him to form what would become one the most productive Formula 1 partnerships.

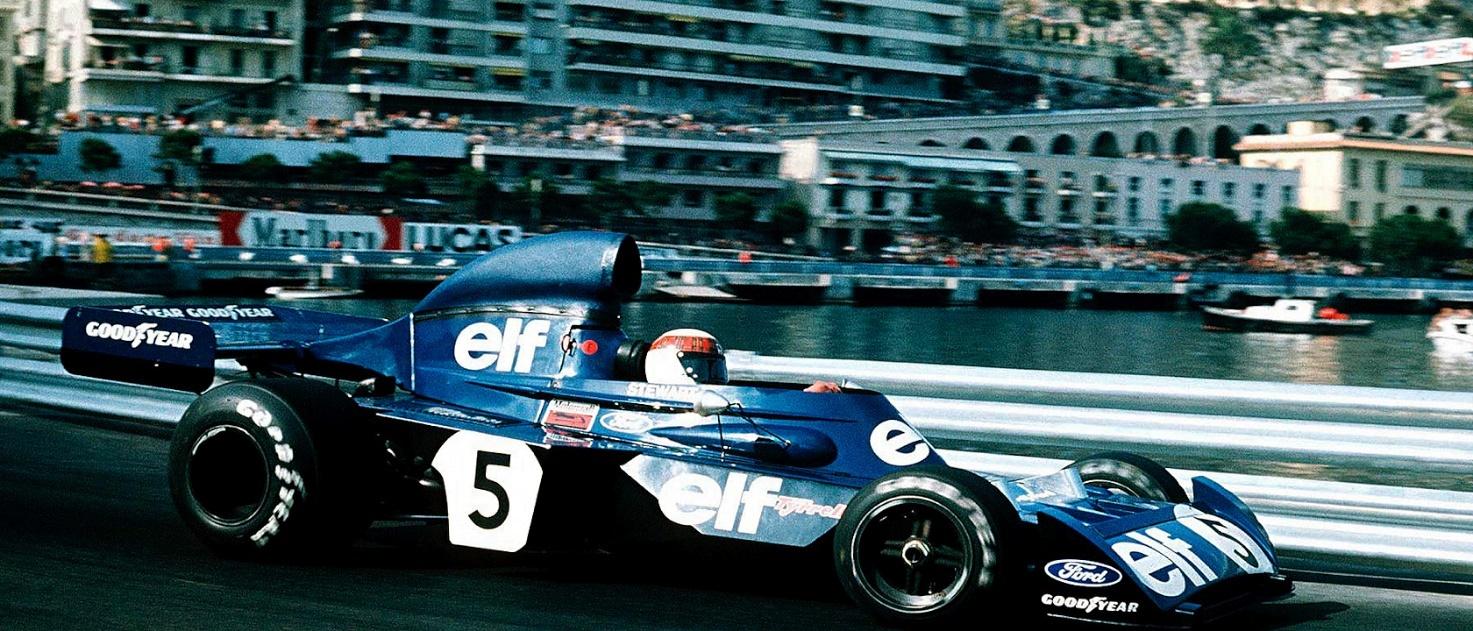

F1 Championship, 1973 Monaco Grand Prix, Jackie Stewart, Tyrrell 006 Ford.

In his six seasons with Tyrrell, Stewart was nearly always the driver to beat and remained so until he retired at the end of 1973 at the age of 34.

Stewart's own brush with death had occurred in the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix when he was trapped in a ditch in his crumpled BRM with fuel leaking all around him. "As it turned out I only had a broken collar bone," Stewart recalls, "but it was simply ridiculous. Here was a sport that had serious injury and death so closely associated with it, yet there was no infrastructure to support it and very few safety measures to prevent it. So, I felt I had to do something."

Among the things he did was to introduce full-face helmets and seatbelts for drivers and help develop the Grand Prix medical unit that began travelling to the races. He successfully campaigned for safety barriers and greater run-off areas at particularly dangerous corners, to protect spectators as well as drivers.

"But there was criticism from the media, even from some drivers," Stewart remembers. "It was said I removed the romance from the sport, that the safety measures took away the swashbuckling spectacular that had been. They said I had no guts. But not many of these critics had ever crashed at 150 miles an hour. Fortunately, I was still achieving a lot of success, winning races in hideously dangerous conditions and that gave me greater influence. For instance, I won four times at the original Nurburgring in Germany - the most dangerous circuit in the world - and yet I was always afraid of that place. In 1968 I won there by over four minutes in thick fog and rain where you could hardly see the road. That race should never have been held and having won it by such a big margin gave me more credibility when I demanded safety improvements. But I wouldn't have done what I did if I had wanted to win a popularity contest."

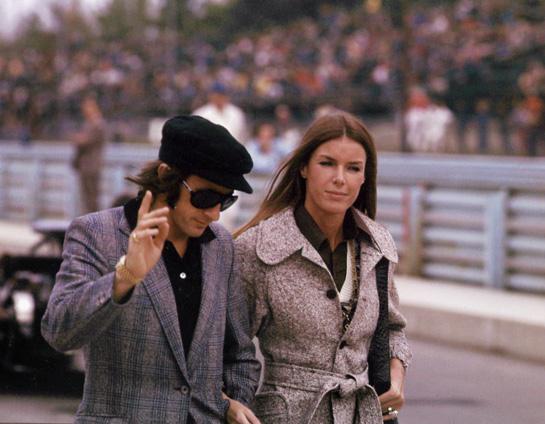

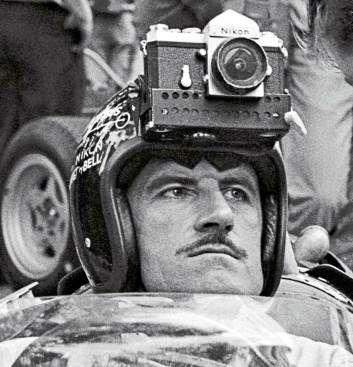

And yet the charismatic and brilliantly articulate 'Wee Scot' became hugely popular with the public. Wearing his trademark black cap and with his hair as long as a rock star, Stewart became an international celebrity - the first Formula 1 superstar.

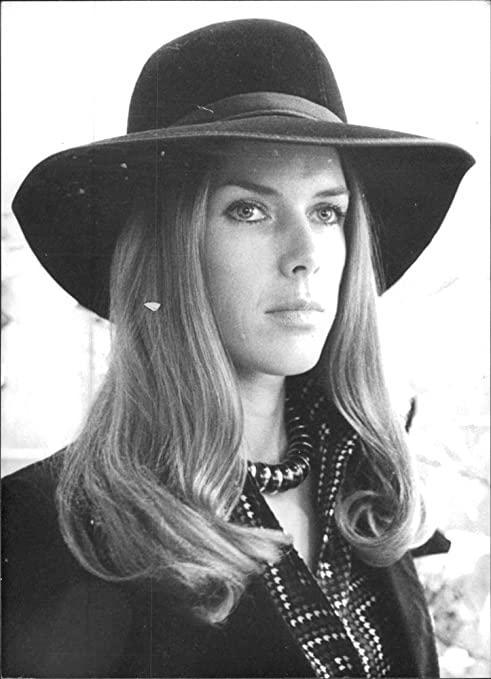

Helen Stewart, née McGregor, watching the action at Silverstone on 28 April 1967. Photo by Ronald Dumont / Daily Express / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

Helen Stewart circa 1969. Photo by Shutterstock.

Helen Stewart, Germany 1970.

Helen and Jackie Stewart.

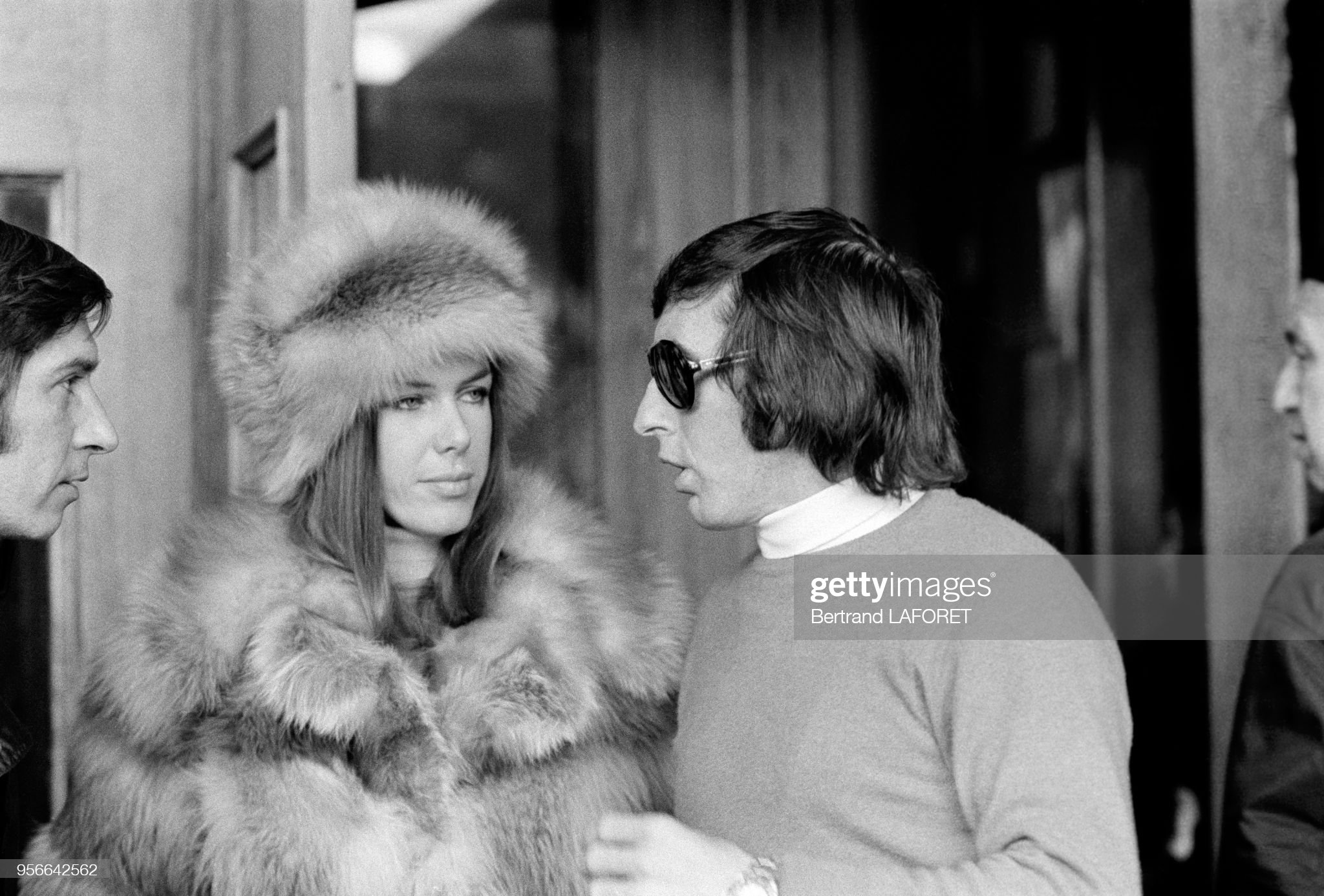

Jackie Stewart and his wife Helen in Saint-Moritz, Switzerland, in February 1971. Photo by Bertrand Laforet / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

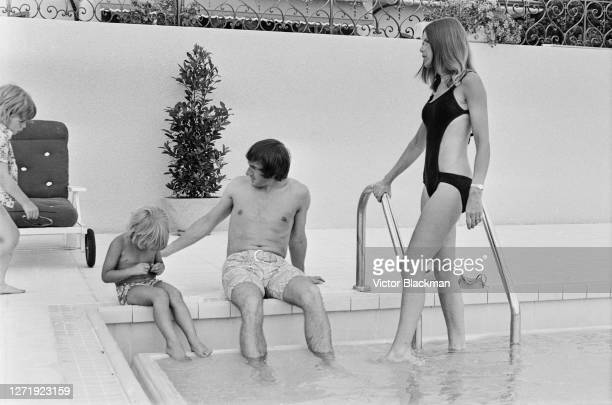

Jackie Stewart, his wife Helen and their sons Mark and Paul at their home in UK on 23rd July 1972. Photo by Victor Blackman / Express / Hulton.

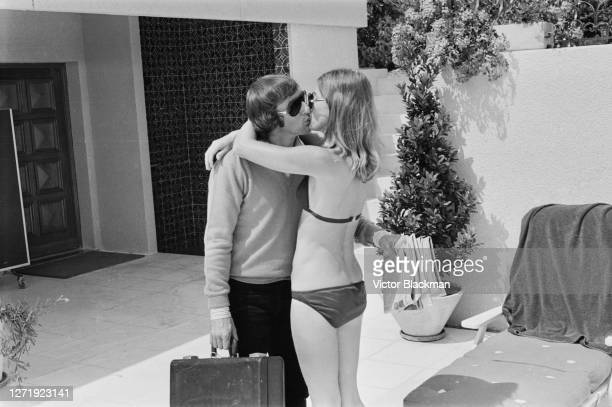

Jackie Stewart kissing his wife Helen at their home in UK on 23rd July 1972. Photo by Victor Blackman / Express / Hulton.

Though he was always a family man (deeply devoted to his wife Helen and their sons Paul and Mark) and never a playboy, he was seen as the daring racing driver with the glamourous lifestyle who consorted with royalty, prominent politicians, musicians and movie stars.

He also frequented the corporate boardrooms of big business and became a multi-millionaire long before he hung up his helmet. He starred in TV commercials and advertising campaigns, gave speeches, went on worldwide promotional tours and had offices in London, New York and Switzerland, where he lived for several years. Stewart was well-placed to cash in on the dividends provided by the arrival of major sponsors when Formula 1 racing became a global television spectacle - a phenomenon in which he also played a major role.

He became a much sought after media personality and a compelling TV commentator, explaining the intricacies of the sport and tirelessly promoting it.

He was always a winner (even his new Stewart Grand Prix team won in 1999 before he sold it to Ford, who re-branded it Jaguar, which went nowhere).

Text - Gerald Donaldson

Sir John Young "Jackie" Stewart is regarded by many as one of the greatest drivers in the history of the motorsport.

After John Surtees' death in 2017, he is the last surviving Formula One World Champion from the 1960s.

He was born in Milton, Dunbartonshire, a village fifteen miles west of Glasgow. His family were Austin and later Jaguar, car dealers and had built up a successful business. His father had been an amateur motorcycle racer.

Jackie attended Hartfield primary school in the nearby town of Dumbarton, and moved to Dumbarton Academy at the age of 12. He experienced learning difficulties owing to undiagnosed dyslexia and due to the condition not being understood or even widely known at the time, he was regularly berated and humiliated by teachers and peers alike for being "dumb" and "thick". Stewart was unable to continue his secondary education past the age of 16, and began working in his father's garage as an apprentice mechanic. He was not actually diagnosed with dyslexia until 1980, when he was 41 years old. He has said: "when you've got dyslexia and you find something you're good at, you put more into it than anyone else; you can't think the way of the clever folk, so you're always thinking out of the box."

Stewart's first car was a light green Austin A30 with "real leather [covered] seats" which he purchased shortly before his seventeenth birthday for £375, a detail he was able to recall for an interviewer sixty years later. He had saved up the purchase price from tips received from his job at the family garage.

Entering the 1973 season, the Scot had decided to retire. His last and then record-setting 27th victory came at the Nürburgring with a 1–2 for Tyrrell. "Nothing gave me more satisfaction than to win at the Nürburgring," Stewart later said. "When I left home for the German Grand Prix I always used to pause at the end of the driveway and take a long look back. I was never sure I'd come home again."

After his crash at Spa, he became an outspoken advocate for auto racing safety. Later, he explained, "if I have any legacy to leave the sport I hope it will be seen to be an area of safety because when I arrived in Grand Prix racing so-called precautions and safety measures were diabolical."

Jackie campaigned with Louis Stanley (BRM team boss) for improved emergency services and better safety barriers around race tracks. "We were racing at circuits where there were no crash barriers in front of the pits and fuel was lying about in churns in the pit lane. A car could easily crash into the pits at any time. It was ridiculous." As a stop-gap measure, Stewart hired a private doctor to be at all his races and taped a spanner to the steering shaft of his BRM in case it would be needed again. Stewart pressed for mandatory seat belt usage and full-face helmets for drivers, which have become unthinkable omissions for modern races. Likewise, he pressed track owners to modernize their tracks, including organizing driver boycotts of races at Spa-Francorchamps in 1969, the Nürburgring in 1970, being joined by his close friend Jochen Rindt and Zandvoort in 1972 until barriers, run-off areas, fire crews and medical facilities were improved.

Some drivers and press members believed the safety improvements for which Stewart advocated detracted from the sport, while track owners and race organizers balked at the extra costs. "I would have been a much more popular World Champion if I had always said what people wanted to hear. I might have been dead, but definitely more popular", Stewart later said.

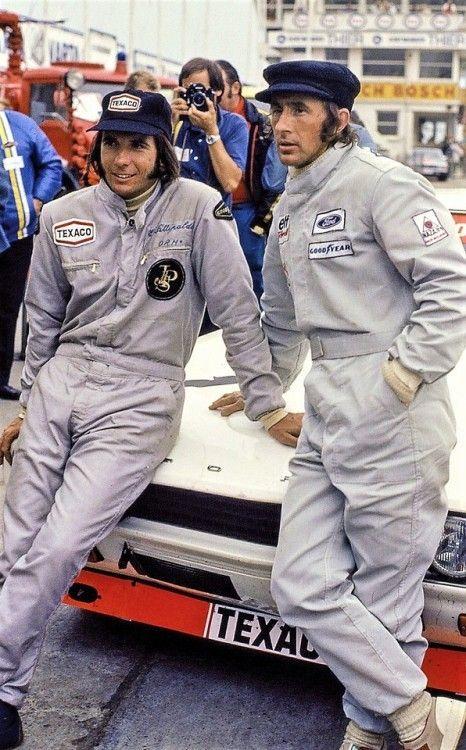

Jackie Stewart and Emerson Fittipaldi at Nürburgring in 1973.

Helena, wife of Emerson Fittipaldi, at Zeltweg in 1973. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

Monaco Grand Prix 2021. Interview with Sir Jackie Stewart by Roberto Boccafogli.

The last Grand Prix, held on the streets of Monte Carlo, was based on distance comparisons and a few overtakings made during the pit stops. Not much, really.

The most painful and significant loss of the race saw Charles Leclerc as protagonist, stopped by the transmission in the formation lap of the grid. Sainz and Ferrari number 55 took home a good second place with some regrets for having lost the chance to set a better time than the fourth, due to the red flag caused by Leclerc’s accident at the end of Q3. But, in reality: the ranking was practically frozen in the top positions, with the exception of Bottas’s unfortunate pit stop and the comeback of Sergio Perez (Red Bull) and of the recovered Sebastian Vettel with a finally competitive Aston Martin. But no overtaking. Okay, in Montecarlo it should not be scandalous: in seven decades of world championship history, only a few anthology overtakings are remembered on the sidewalks of the Principality.

Two questions: why, beyond the technical notes, overtaking has ceased to be a commodity on offer on the GP market? And why should the necessary interventions not be allowed to avoid technical problems or inconveniences, potentially dangerous if they happen on track, effectively depriving the drivers and teams of participating in the race as happened to Leclerc?

For this last aspect, it’s crazy: teams of technicians, sophisticated vehicles, sponsors who pay millions and the public who pay to see a show, find themselves without any possibility to carry out the necessary checks except with the sword of Damocles of the penalties on the grid. Just to check, Scuderia Ferrari would have had to remove some details that would have triggered the penalty. The technicians from Maranello took a risk which, this time, did not pay off. For once, you can take a risk, I mean.

Regarding single-seaters and their performance, there are different aspects that should be taken into consideration. To be able to race safely, as the cars have grown in size, the tracks should have the same development. The circuits are now almost limitless, with the judges penalizing the drivers who cross the lines painted on the asphalt. Curbs that do not limit the "cuts" and any digressions beyond the track do not involve wasting time or positions. It is no longer a question of safety. Or, at least, not only.

Beyond the technical aspects that have brought the dimensions of the current single-seaters to extreme levels, the performance of the engines is reducing the "work" of the driver, whose job is examined and studied down to the smallest detail, vivisected and discussed with an analysis so deep that it leaves no room for the simple interpretation of the driver himself. The use of new materials, increasingly extreme and reliable, has reduced any margin of "interpretation" of the driver with respect to his own vehicle.

“In our time almost everything happened under braking, Jackie Stewart sums up the day after Verstappen's triumph with his Red Bull. And it was not just a question of when to brake: back then the differences between one driver and another and between the different single-seaters, in terms of braking point, could be considerable. And that made a difference, of course. But the braking length itself was also enormously greater than today. With today's F1 cars and their super-efficient brakes, the braking point between two drivers already differs slightly. But it is the braking itself in terms of maneuver length that changes everything. Today the braking is instantaneous: a matter of a few tenths; it is almost an automatism, it does not allow you to vary anything. Fifty years ago, braking could start at 100 meters from the corner, even at 120 and you would remain with the brake pedal fully depressed for 50-60 meters. Between when you were pressing on the brake and when you were lifting your foot a very long time was passing, within which the car was still to be driven. An interval in which many things could happen, from the change of trajectory onwards. Today it is impossible. Braking is no longer an interpretable interval, except in rare cases. It doesn't allow you to invent much”.

The reasoning is flawless. And even the aerodynamics of the time, without the inhibiting effect of today's slipstream, allowed you to express yourself more if you were planning an overtake. Today, in reality, between boundless escape spaces (apart from Montecarlo, of course) and protective monocoques like an unbreakable armor, the risk for the driver is infinitely less than it once was.

“It's true, Stewart continues, we always raced with risk on our heads. The risk of penalty, in case of error or bad luck, was gigantic compared to today. And I wouldn't make it an issue between adventurous drivers and calculating drivers: Fangio was an exceptional calculator, yet he was doing very well; I also believe I have been very analytical, especially with an advanced career.

Matra Sports.

Tyrrell park. Leyland Motors (1970).

In 1969, at Silverstone, Rindt and I (driving a Lotus and a Matra respectively) have overtaken each other in the race 39 times!

And practically all the overtaking took place at the end of the Hangar Straight, heading towards the Woodcote corner which that year was made at 153 miles per hour (over 246 km/h ...). The risk was not a small thing: hitting hard, back then, or capsizing, without carbon around you, without Halo, with the risk of fire ... There was little to joke about. And the races were endless: physically tough, with fearful vibrations that worsened for the duration of the race, brakes that worked worse and worse. I have always been small, but in a GP I lost four kilos of weight. Yesterday, on the podium in Monte Carlo, none of the three showed a drop of sweat. They will also be better prepared physically, but I think their fatigue is less. Yet, I believe, the sense of risk today is different. And I don't blame technology: the level of security today is excellent and this is, undoubtedly, phenomenal progress. A conquest. But, if risk was part of the program back then and we faced it, today it may not be anymore. Or it is less. And this affects overtaking, I think”.

So, has the driver changed? Jackie's reading suggests an epochal change, a real transformation of man and therefore necessarily of sport ...

“No, I would say no. The animal is always the same. It hasn't changed. The rush to win, the adrenaline and the aggressiveness, I think are no different from my times. I wondered too, frankly, why Lewis didn't even try in Monte Carlo. Okay, the circuit is not what encourages overtaking. But with a Mercedes in the middle of the group… Well, you can see that, on a technical level, he had something wrong. But in a broader sense ... yes: the animal is always the same, I am sure of it; it’s the risk that is no longer part of the program, or is much less part of it. Today, the greatest job of a driver is to best interpret the mountain of technique that surrounds him. We wondered if our engine would hold out, if the brakes were still on our side. Today they know everything in a millisecond: their work table is the steering wheel, from which to receive any information in real time and on which to act in the most precise way. And with this, mind you, I don't want to say that managing today's crazy speeds, especially cornering, is easy. Or easier. But today, with all that technique, the driver has less power. We had more because, among our arrows, there was also what was called risk. Today, at least it seems to me, the risk factor is no longer understood”.

It is not easy to understand that Jackie wants to soften the reading, in defense of what is however his category. But, from this reading, emerges a driver perhaps pushed by the sacred fire as always, but with a different code of behavior. With different procedures to follow, to interpret.

Helen Stewart charts Jackie’s lap times at Monza in 1967. Note Helen’s early, very 1960s style, before she settled on a rather different look. Source: forum.b92.net.

“This I don't know, he continues. What I know precisely is that everything was more dramatic back then. Which in racing means: more dangerous. Towards the end of the 1960s, in the summer season, we reached a monthly average of over one death in racing. Every time we left home we asked ourselves: will it be someone's turn this weekend too? Isn't it my turn? I have seen many colleagues end badly a few meters from me. I was among those who took Rindt to the hospital in Monza and he was practically already dead. I was in the race when Piers Courage or Roger Williamson died. Terrible moments: yet I have never cried. Never.

I cried only once: when Jim Clark died in Hockenheim. And I wasn't even there: I was in Jarama, Spain, for a visit dedicated to circuit safety.

Jim Clark at 1964 Mediterranean GP. Photo by Vittorio Giordano.

I heard the news and burst into tears: Jim was a very dear friend, he had been my son Mark's godfather. It was a gigantic pain. But then, when I went back to get into a cockpit, everything was immediately as before. Back then the drama was part of the menu: today it isn't anymore”.

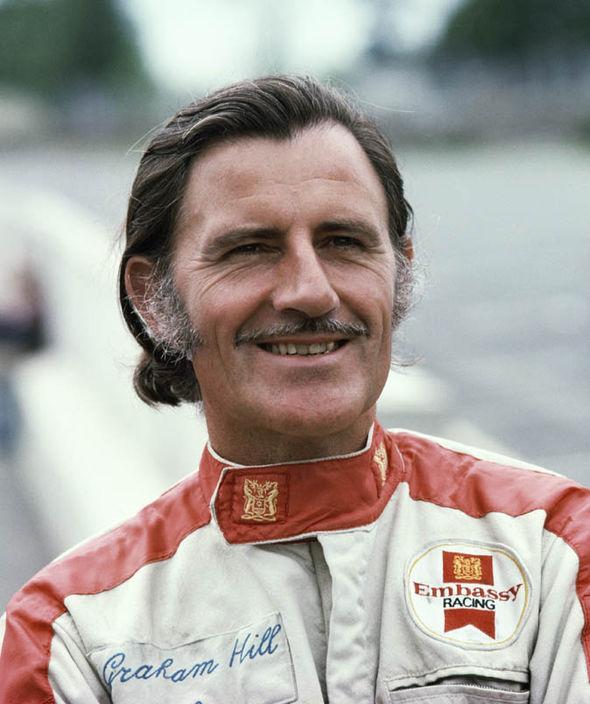

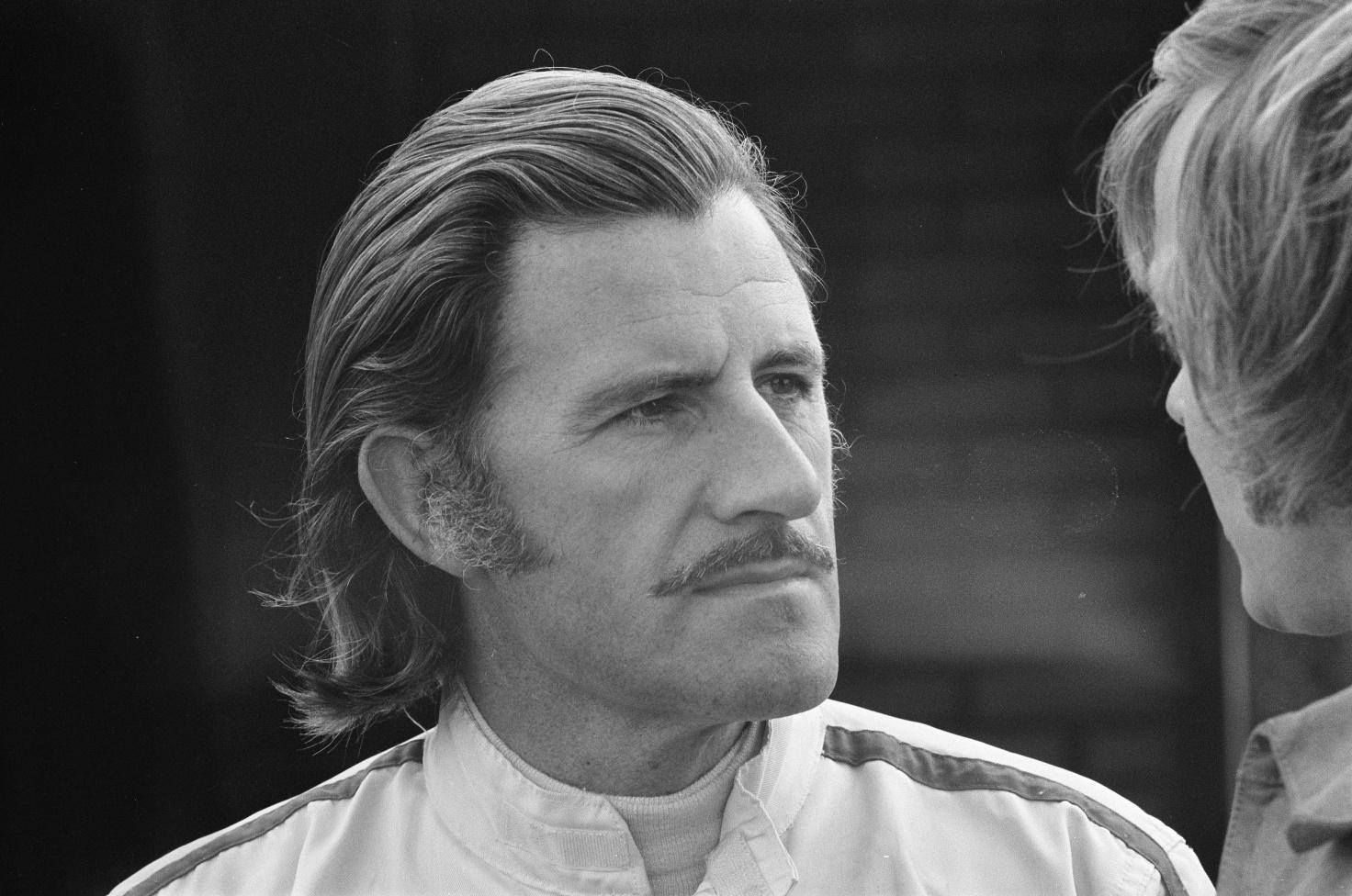

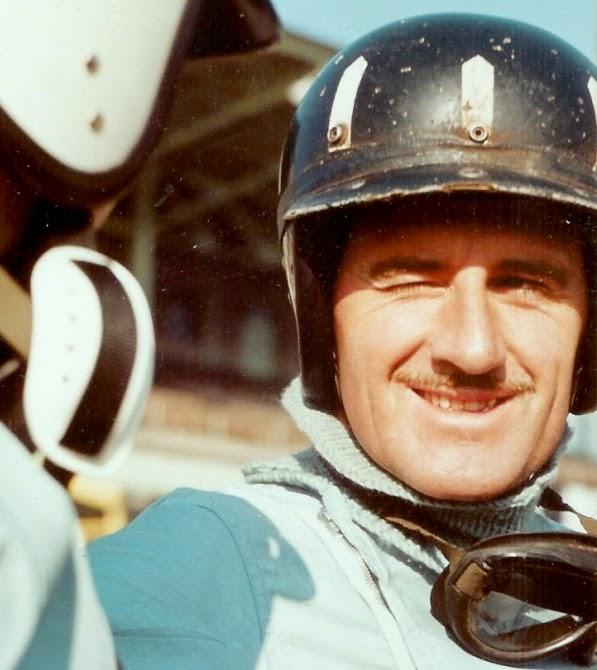

Graham Hill

The class of a lord and the face of an actor. And the skills of the great driver. Graham Hill radiated magnetism. With the racing suit he was simply flawless, perfect as if he were wearing a tuxedo. And the bearing was regal. A quintessential English man with a Mediterranean character.

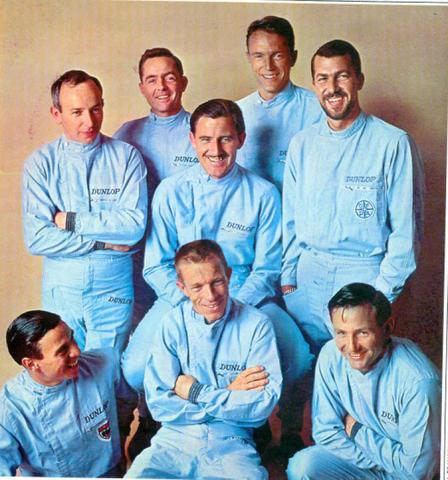

Sky blue was obviously this season's hot colour. Left to right John Surtees, Phil Hill, Graham Hill, Dan Gurney, Jo Bonnier, Front Jim Clark, Richie Ginther and Bruce McLaren.

Graham Hill with Niki Lauda, Jackie Stewart and Jacky Ickx.

A casual Graham Hill, in conversation with a suited and helmeted Dan Gurney. Source: facebook.com.

Stirling Moss with Graham Hill.

“I am an artist. The track is my canvas and the car is my brush.” Graham Hill

“Formula 1 is like keeping an egg in equilibrium on a teaspoon while riding the rapids in a canoe.” Graham Hill

“Time is of the essence... and I’m very short of essence.” Graham Hill.

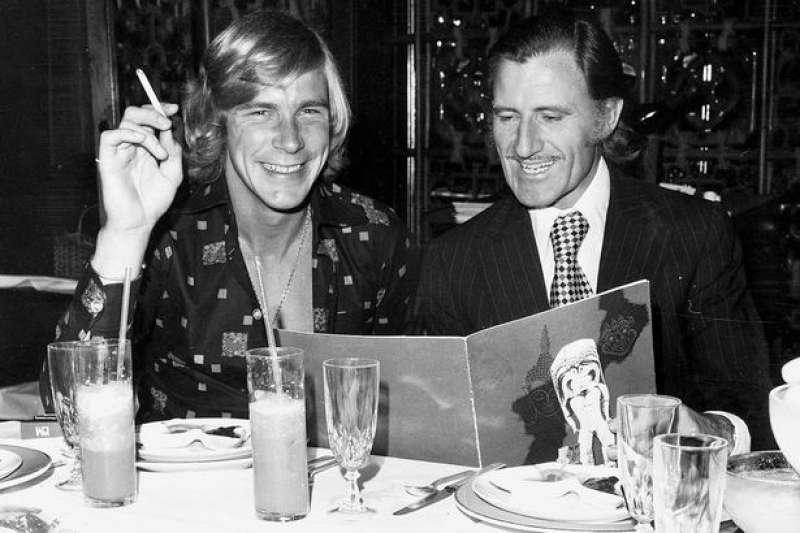

Graham Hill and James Hunt were the greatest characters in F1.

Graham Hill and James Hunt.

“He was impossible, he was never punctual, ever, ever, ever.” His wife Bette talking about him.

Hill enjoyed life. He loved parties, great parties. “I think we had some of the best parties anyone ever gave. Jimmy (Clark) was bringing a different girl every time, things like that.” Bette Hill.

“Graham did what he wanted to do, he didn’t speak to me, he told me.” Bette Hill.

“He was driving anything that anybody would offer him.” Doug Nye, motor racing historian.

Many think that Graham Hill wasn’t the most natural driver. This isn’t said to slight him or doubt his abilities but to acknowledge his approach to driving. As Jackie Stewart said, “whereas Jimmy [Clark], Stirling, to a certain extent myself, would drive around a car’s handling problem, Graham would fiddle with the car until it was right. Graham would take very different lines around a corner to others and I know because sometimes I was following him.”

“Graham Hill, fantastic. Very experienced, solid racing driver. He behaved immaculately with me. He charmed people, a great man.” Jackie Stewart.

Graham Hill: a portrait. Bas Naafs posted in “Home of F1” 3 years ago.

Few drivers in the history of motor sport can prove they’ve won the Triple Crown. Well, only one of them can actually.

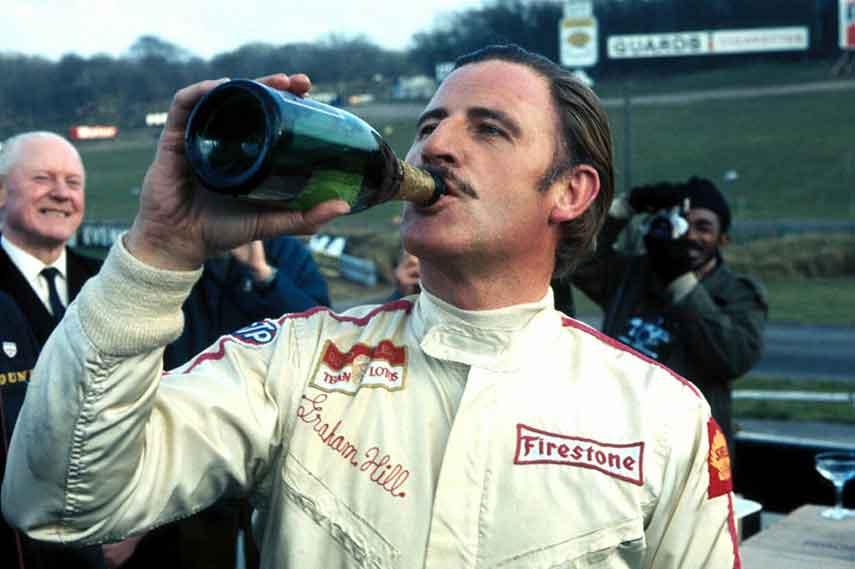

Graham Hill, F1 world champion in 1962 and 1968; winner of the 1966 Indianapolis 500; winner of the 1972 24 hours of Le Mans and five times Monaco GP winner.

Graham Hill at Monza in 1968. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

An incredible achievement that underlines the fact that Hill was one of the most complete drivers of his time.

1968, Nurburgring. Graham Hill in his Lotus.

He was fast, but not the fastest. Talented, but not the most talented. The best, but not always and everywhere.

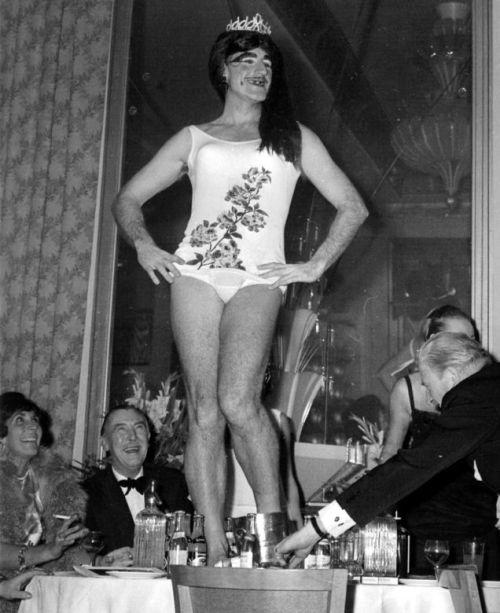

Explosive, but predictable. Professional, but with enough self-mockery to pull his pants down at dinner parties, running up and down the tables.

Graham Hill and Jo Siffert, France 1968.

Hill drove his cars throughout the most dangerous years of the sport.

Jim Clark and Graham Hill at Pergusa in 1967. Source: casten.it.

Graham Hill with Jim Clark.

Graham Hill with Jim Clark.

Calmly and reserved, while he tried to fight off virtuoso's like Clark, Rindt and Stewart. He was and to me still is the greatest British ambassador of F1.

Spanish GP 1968.

He did a grid-walk before every Grand Prix, inspecting the cars of his fellow drivers.

Graham Hill driving the Lotus 49 in 1969.

Every now and then he would pull a dramatic face when looking at a certain part of the engine or suspension and theatrically walk off to his own car, leaving his competitor in sheer anxiety re-checking every part of the car that Hill just scrutineered.

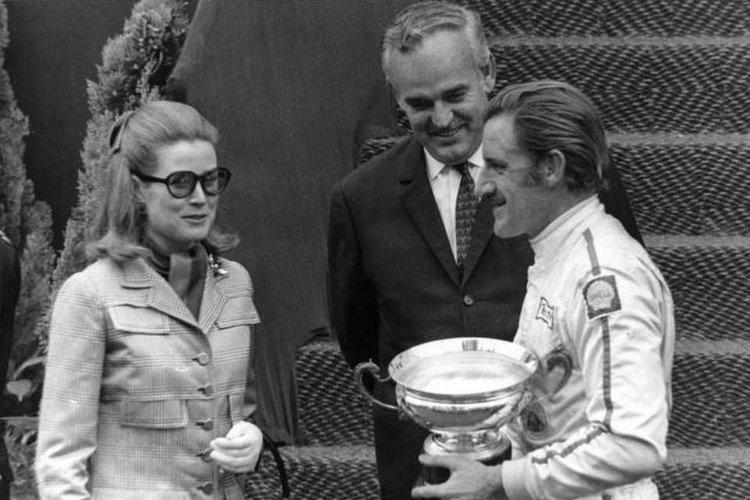

Hill's nickname was Mister Monaco.

Five times did he manage to win the race.

It was his pièce de résistance, the podium upon which he could show the world he lived in perfect harmony with the speed of his car and the parts that kept it going (which, with a Lotus, was never a guarantee).

Hill drove 179 Grands Prix, over a period of 18 (!) seasons. He overcame the bloodiest period in the sport, he was meant to be a hundred.

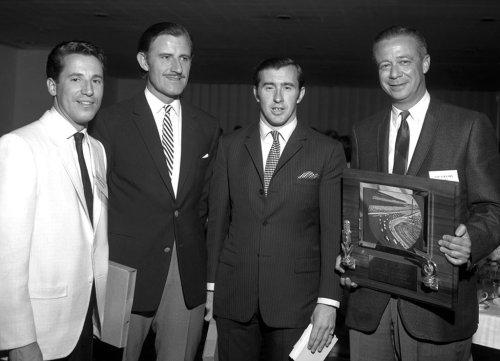

The 1967 Indianapolis Banquet. Mario Andretti is channeling the Godfather and jolly nice he looks too. Jackie Stewart is keeping it simple and Graham Hill is keeping it English in a dubious blazer and slacks. Source: f1-history.deviantart.com.

Graham Hill in 1968.

Norman Graham Hill was born in Hampstead, north London, on February 15, 1929. He attended Hendon Technical College before becoming, at 16, an apprentice instrument maker at Smiths instrument company. He was conscripted into the Royal Navy where he was stationed on the cruiser HMS Swiftsure as an Engine Room Artificer (ERA). The ERA’s were competent men, able to read and write and were to be considered experts on the entire mechanical plant of warships. They were often the senior mechanics on board. It’s not difficult to see where Hill got his mechanical skill from, which proved to be beneficial in his F1-career. In 1953, on a whim, Hill answered to an ad from a Brands Hatch race club who offered everyone a drive in a Cooper 500 F3-car for five shilling. Hill paid for four laps and was "immediately bitten by the racing bug."

Graham Hill ‘The King of Monaco’ after the first of his 5 wins in the Principality. Getty Images.

In 1958 Hill finds himself in the cockpit of a Lotus 12 at the start of the Monaco Grand Prix. In 1975, Hill remembers: ‘I was sitting there on the start line, wondering what was going to happen (…) so I just rounded up to six thousand revs per minute. I sat there looking at the start grid, he dropped the flag, I slipped my foot off the clutch and I went up the road like a rocket!’ The interviewer and the audience started laughing as Hill fiddled with his mustache. ‘But I was in the lead, wasn’t I?!’ Well he wasn’t exactly in the lead. After 75 laps he was in fourth place. Just as Hill thought, ‘this is great, Formula 1 is a piece of cake’, his halfshaft broke and he had to retire from the race. Even though Hill was now competing on the world’s highest level of motorsports, he became increasingly disgruntled over the fact that Chapman wasn’t able to build a race car that could finish a race. BRM offered Hill a drive in 1960. ‘I remember everyone saying ‘’well that’s a mistake, you’ve joined a losing team’’’. Hill teamed up with Tony Judd and started developing a new car that would eventually evolve in the 1962 championship winning P57. How ironic that Clark lost out on that title because his Lotus broke down in the last race while in leading position.

Spa Francorshamps, 1966. Heavy rains poured down on the track as the drivers made their way through the first lap. Seven out of fifteen cars that started the race made it through the first lap. Jo Bonnier slid off the track and managed to come to a standstill on the edge of a viaduct with the cockpit of his Cooper hanging in the air. The only thing keeping him from plummeting 15 feet down to the ground was his heavy Maserati V12 still parked on the track. Together with Jo Siffert and Mike Pence, who crashed their cars nearby, Bonnier sought shelter under the porch of a nearby house from where he spectated the rest of the race. Moments after, Jackie Stewart suffered the heaviest crash in his career. Moments later Graham Hill lost control of his BRM in the same corner. Hill was able to continue his race, but he noticed something below him: ‘I started looking for the gear lever and as I looked down I was like ‘bugger me, that’s Jackie down there! In a car! Good God that doesn’t look so good.’ (…) so I jumped out of the car and he was trapped.’ Bob Bondurant, also out of the race, assisted Hill in his efforts to help Stewart. In a car belonging to a spectator they managed to find a toolbox with a spanner in it. It took Graham and Bob 25 minutes to get Stewart out. By then, the high octane fuel started to irritate Stewart’s skin, so Hill insisted on him taking his clothes off. Stewart was put in a parked van (or pick-up as some sources say) naked. A group of nuns from a nearby abbey heard of the crash and made their way to the scene to see if any assistance was needed. The three nuns almost got a heart attack when they saw Hill, with his devilish mustache and perfectly combed hair looking after a naked Jackie Stewart. ’Poor, old, injured racing driver being taken advantage of’, Stewart remembers.

Hill was a ruthless driver. Not so much ruthless on the track as he was in the garage. He took notes of every test, every practice, every race and how his car handled specific track conditions and setups. He was constantly on top of his mechanics with these early versions of telemetry and his expertise on engineering meant that the difference between mechanic and driver was nothing more than a grey area. According to some of the mechanics who worked with Hill, it was sometimes impossible to please him.

By the end of his career, when he was already in his forties, Hill still was extremely competitive and refused to quit driving. He would go the extra mile to realize his dream of driving in Formula 1, even after all those years. His victory at the 1972 Le Mans showed everyone he still possessed the necessary pace to go for victories, though not a single F1-team offered him a seat.

However, Hill was still able to hide his business-face from his trolling-face.

In a time when an F1-driver was closely followed around by international media, Hill, like no other, knew how to put aside his obsessive character when the cameras started rolling.

Jackie Stewart remembers this as an almost scary trait. One moment you’d be walking through the pits with him, giggles all the way while taking time to answer questions from journalists, next moment he’ll be throwing a tantrum against his mechanics back in the garage. Do realize, behind his perfectly trimmed mustache and charming smile, a serious business man was hiding.

Racing driver Jackie Oliver and wife model Lynne Hamilton after their wedding in July 1970. Photo by Shutterstock.

Jackie and Lynne Oliver at their charmingly informal, very stylish wedding. Graham Hill was best man at the wedding.

Monaco Grand Prix 1970, Lynne Oliver representing Yardley sponsorship for B.R.M.

Graham Hill, until about 1970, maintained a fashion persona that dated from the time of the crank-started car.

Needless to say, when Hill did manage to jump in front of the camera, it was a blast.

Hill and Stewart often formed a duo on BBC-shows in which Hill blossomed as an interviewer. Hill interviewed Stewart in 1971 just after the Scot won his second title: ‘you’ve won six Grands Prix, which is hogging it slightly. Seven Grands Prix is the record [Jim Clark in 1963], where’d you think you could have done it and it didn’t happen?’ Stewart looks at the audience slightly perplexed: ‘I don’t think that’s a fair question’, the Scot replied. In 1973, Hill congratulated Stewart on his retirement. Stewart replied: ‘Graham, I only hope that the example I’m giving will allow a few more to retire.’ Obviously hinting at Hill’s age. In a different interview Hill was asked if there are any terribly personal things he does which others don't know about. Hill looks at the interviewer with a straight face: ‘what, wanking you mean? Or something like that?’ The interviewer bursts out in laughter as Hill himself cracks up as well.

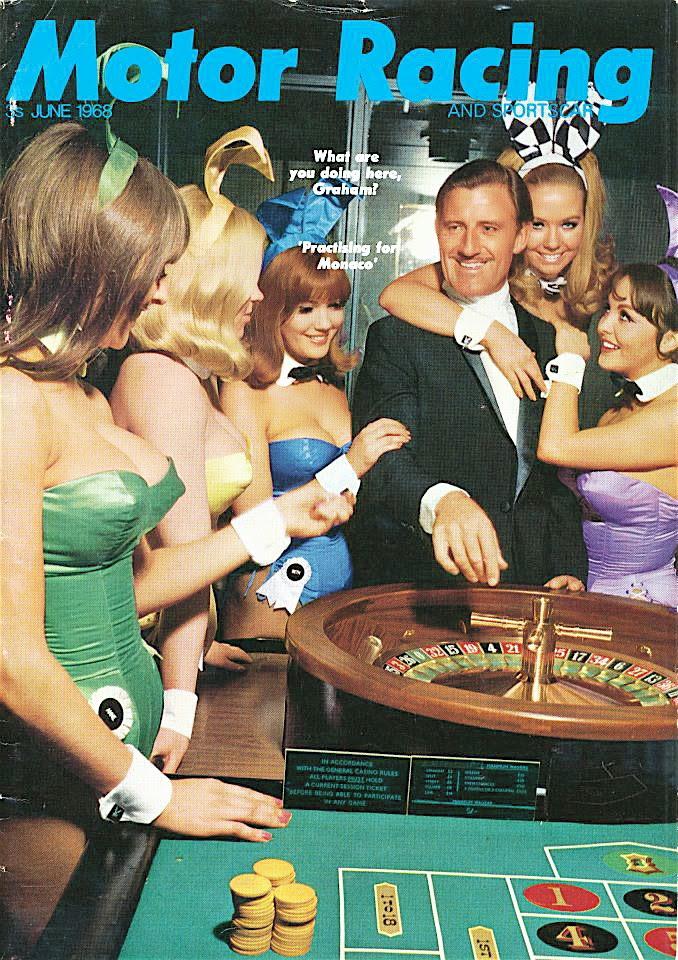

Graham, the ladies’ man, ‘practising for Monaco’ in 1968. Picture: Autoinjected.com.

Motor Racing magazine put Hill on the cover of their Monaco-special. Hill, surrounded by Playboy playmates, is ‘practicing for Monaco’.

He loved women, women loved him.

Graham Hill with a fan.

Graham Hill with a girl.

Graham Hill.

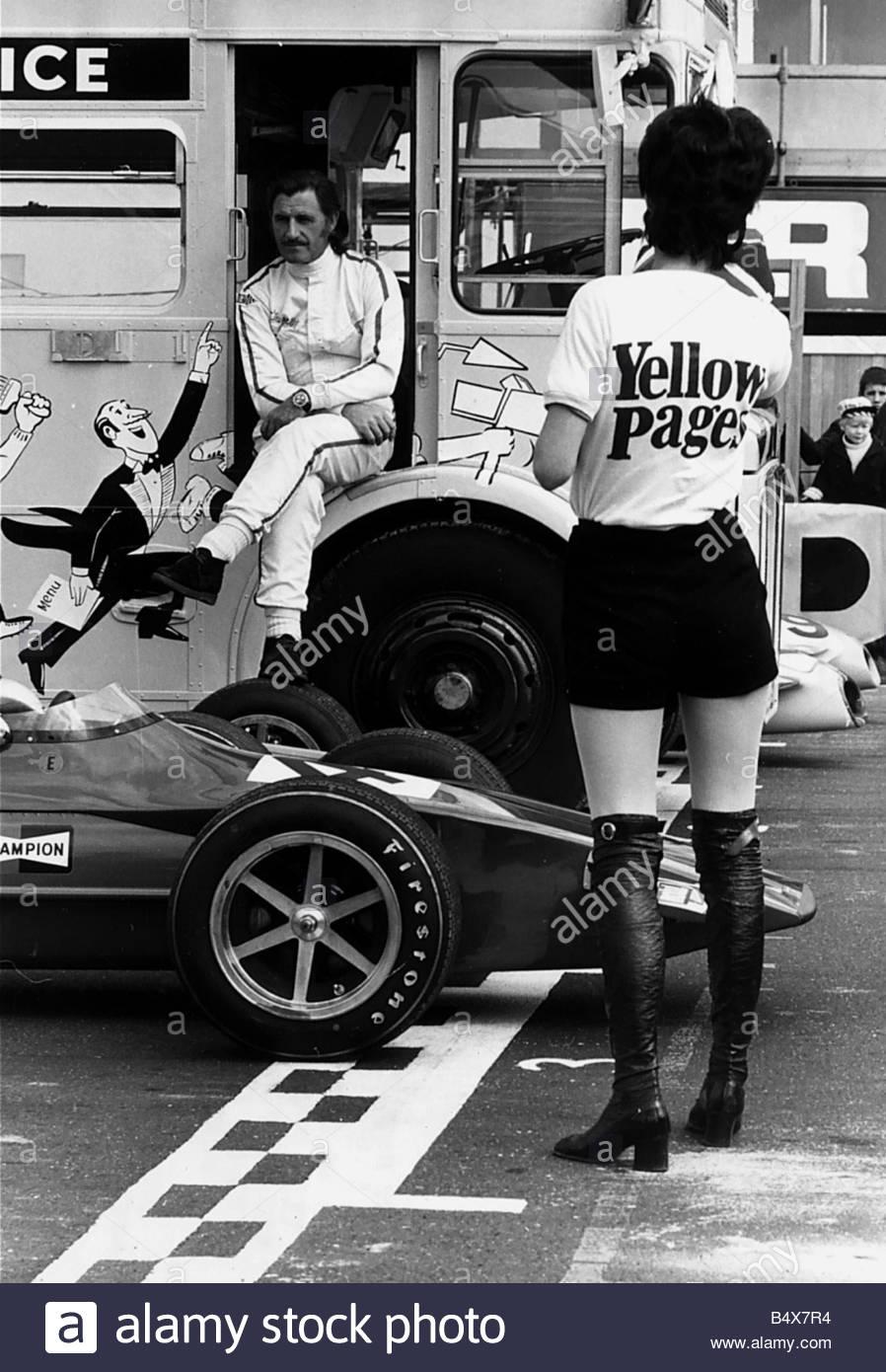

Graham Hill with a “yellow pages” girl in 1971.

Graham Hill avoids the usual female impersonator traps by leaving off the OTT frocks and hair updos, instead opting for this true-to-life beauty pageant look.

According to Damon it was the mustache, ‘my dad slotted into this image of a cad kind of British person who could be a charmer one minute and the next minute standing on the table dropping his pants.’

Graham Hill opened the gala day at Ashford airport.

Friend and artist David Wynne acknowledges that, ‘he had a keen eye for the ladies, that’s not only [a] fair [thing to say], it’s dead on the mark! He was the man.’

Graham Hill, miss motor racing Jackie Peterson and Jack Brabham in 1965.

Graham Hill never saw his son Damon win the world title and that’s a shame.

Graham Hill with little Damon.

The two generations Hill were the only father and son to have won the world title until Nico Rosberg clinched his title at the end of 2016, following his father’s footsteps as well. Graham Hill was one of the most likable figures of the F1-paddock.

-

’You say you want to live to be a hundred. Aren’t you in the wrong job for this?’

’That’s why I want to live to be a hundred.’

FOCA in 1974. Behind, from left to right: Jimmy Dilamarter (Parnelli), Heinz Hofer (Penske), Anthony Horsley (Hesketh), Ken Tyrrell (Tyrrell), Colin Chapman (Lotus), Frank Williams (Iso-Marlboro), Luca di Montezemolo (Ferrari), Bernie Ecclestone (Brabham), Graham Hill (Hill), Alan Rees (Shadow), Teddy Mayer (McLaren), Velko Miletich (Parnelli). Front, from left to right: Ray Brimble (Hill), Max Mosley (March), Peter McIntosh (secretary).

Graham Hill. August 2, 2014.

Graham Hill's iron-willed determination, fierce pride and great courage enabled him to overcome the odds against more naturally gifted drivers.

None of them was more popular with the public than the moustachioed extrovert with the quick wit, who loved the limelight, was a natural entertainer and became one of the first Formula One media stars. His fans remained loyal, even when he damaged his reputation by racing too long past his prime.

Graham Hill and Bette beside their plane.

Millions were shocked when he was killed not in a racing car but at the controls of his plane.

Graham Hill claimed he inherited his determination from his mother and his sense of humour from his father, a stock broker. Both qualities were required to endure the deprivations and dangers of life in wartime London, where Hill grew up during the Blitz. He played drums in a Boy Scout band and went to a technical school. He bought a motorcycle and on a foggy night crashed it into the back of a stopped car, suffering a broken thigh that permanently shortened his left leg.

His desire to scratch the itch was hampered by two problems: he hardly knew how to drive even a road car and could scarcely afford to fund a racing habit. He bought a rattletrap 1934 Morris, taught himself how to drive and got a license to drive on public roads. He quit his job at Smith's, collected unemployment insurance and talked his way into a job as a mechanic at a racing school, where he soon became an instructor.

Hill with Colin Chapman and Jim Clark.

He competed in a couple of races and met Colin Chapman, then in the early stages of developing his Lotus cars. After persuading Chapman to give him a part-time job (at one pound per day), Hill soon became a full time Lotus employee and was rewarded with the occasional race.

The dashing driver with the roguish moustache, naughty wink and quick wit blossomed as a media hero and greatly enjoyed his notoriety. He became famous for such antics as dancing on table tops, enlivening parties by performing bump and grind striptease acts and, once, streaking naked around a swimming pool.

Bette Hill.

He flirted outrageously with women, to the chagrin of his long-suffering wife Bette. As if the dangers of racing weren't enough Hill bought a plane and became the carefree, sometimes careless, pilot of 'Hillarious Airways.'

Graham Hill, Monaco 1968.

In 1969 he won Monaco for a record fifth time, though it was followed by a downward spiral precipitated by a huge accident in the last race of the season, the US Grand Prix. When Hill's Lotus spun and stalled, he got out, push-started it and resumed driving without fastening his seat belts. A tyre suddenly deflated, pitching the Lotus into a bank and throwing Hill out, breaking his right knee and badly dislocating the left. He recovered and continued racing but was never the same driver again.

In 1973 he set up his own Formula One team, but Embassy Hill Racing and its famous driver were embarrassingly off the pace. Finally, following the humility of failing to qualify for the 1975 Monaco GP, Hill announced he was retiring as a driver but would continue to run the team led by his highly talented discovery, Tony Brise. A few months later Hill, Brise and four other team members were dead.

Text - Gerald Donaldson

Graham Hill: English gentleman, oarsman and king of Monaco. May 9, 2014.

Graham Hill at the 1971 Dutch Grand Prix. Picture: Wikipedia.

Tim Koch writes: veteran British readers and anyone interested in motor sport will know of the English racing driver, Graham Hill. He was one of those sportsmen who were held in great affection long after their career ended, not only by fans of the sport in question but also by ‘the general public’. In the days (not so long ago) when Britain was a more deferential country, this widespread affection was gained not so much by simple sporting success – it was most assured if the athlete in question was thought of as ‘a gentleman’ who seemed to win ‘effortlessly’. It was popularly supposed that Hill was such a man. When his perceived wit, charm, charisma and his reputation as a ladies’ man par excellence was added to the mix, the legend was assured. It was a legend that rowing can take some credit for.

I have no real knowledge of motor racing and consequently am reliant on the writings of those who do claim to know something of it. There seems to be some sort of consensus among such people that Hill was not the most naturally talented of drivers but he achieved a genuinely unique success by force of will, hard work and an attention to detail. There were certainly no ‘effortless’ wins, whatever the public may have thought.

The internet has many affectionate (though rarely totally uncritical) takes on the man, his sport and his life.

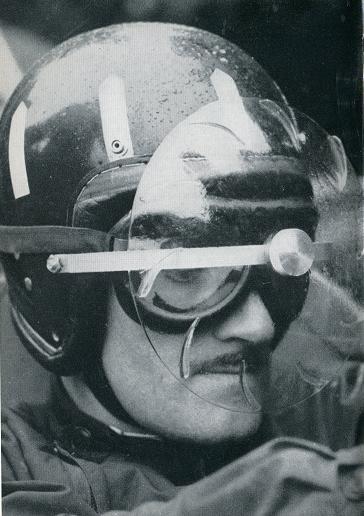

Graham Hill models an early full-face visor in 1964. It spun round, I think to keep water off it. Funnily enough, no-one uses them now. Source: forums.autosport.com.

The Slog: when Graham Hill became something of a hero for me around 1964, he already looked out of date. Despite the long hair and sideburns that later transformed him into a racing rock star as the Sixties progressed, his laconically courageous speaking style, refusal to take much beyond mechanics seriously and appalling pencil moustache made him more of an archetypal Spitfire pilot than a racing driver.

The Gentleman’s Digest: racing, in the 1950s and 1960s, was a different sport than the modern Formula 1. Drivers used to be more involved in…… the more messy tasks of the behind-the-scenes mechanics than the professional pilots of the modern circus. Often, drivers would drive their own cars to the track, towing their race cars on a trailer. Hill, like other stars of his time, was therefore much more than a pilot in the modern sense; he was also a mechanic, a technician and a developer. As an ambassador of style, Hill was famous for his iconic sideburns with the pencil thin moustache and the sleek, combed back hairstyle. Even after a full race of 60 laps under a helmet, Hill’s haircut would be perfectly put together. He would combine his signature style with the fine sense of fashion inherent to an English gentleman.

8x.forix.com: Graham Hill was the face of motor racing in Britain in the 1960s – extrovert, fun-loving, dashing, rakish, moustachioed and handsome he was the public’s idea of what a racing driver should look like…….. He might have been a throwback to the 30s when chaps went racing for fun and could afford to spend large amounts of money on their hobby. Yet he had worked his way up from nothing….., he did not have enthusiastic parents who could dispense large amounts of money……. He was a late starter too: his first sporting love was rowing……. And rowing was to be an ever-present part of his motor racing career too – the familiar dark blue and white helmet which he always wore was based on the colours of the London Rowing Club – in his autobiography he remarked that he seemed only to excel at sports which allowed him to sit down while competing and that he could even do one of them facing the wrong way.

Hill in his iconic racing helmet sporting the colours of London Rowing Club. Picture: hooniverse.com.

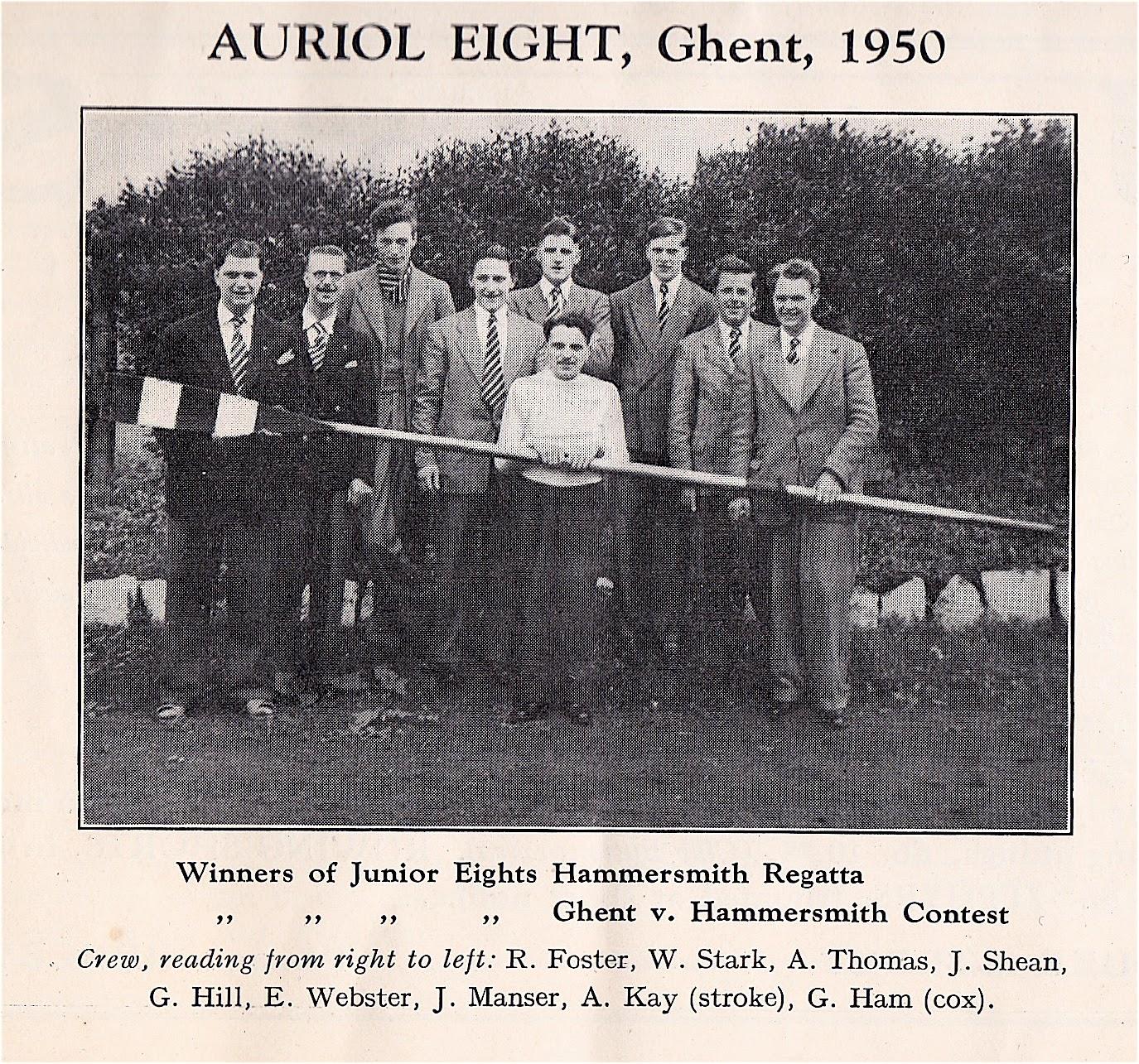

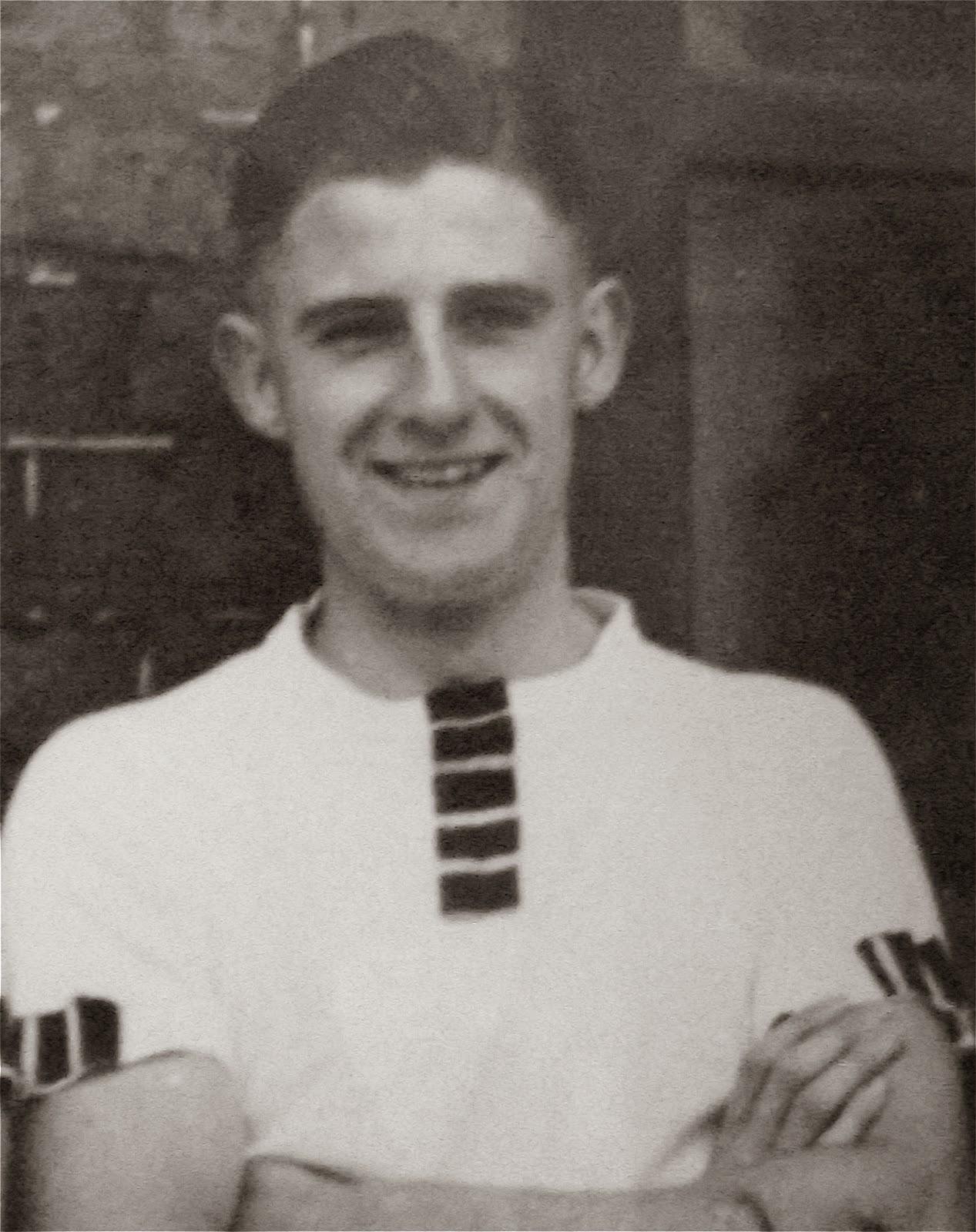

Hill’s entry into the world of competitive sport was through rowing. Some sources state that he started at London RC where he was an active member from 1952 to 1954. Some say that he first took up rowing at Southsea Rowing Club on the south coast of England while doing his National Service with the Royal Navy in Portsmouth from 1950 to 1952. The truth is that he was introduced to the sport at Auriol Rowing Club in Hammersmith, West London, by a cousin, John Ward. The club minute books record that his membership was approved at the committee meeting of 25 August 1949. The twenty year old must have been a quick learner as his first sporting success came nine months later when he rowed at ‘4’ in the crew that won Junior Eights at Hammersmith Amateur Regatta on 6 May 1950. His first taste of international competition came two weeks later when the crew raced ‘Junior International Eights’ at the 60th Terdonck Regatta, near Ghent in Belgium. It was a seven boat race which included crews from Belgium, Holland and France. Auriol led all the way but were beaten on the line by Antwerp Sculling Club who won by 1/5 of a second.

The winning crew in Junior Eights at the 1950 Hammersmith Amateur Regatta. Hill is top right. (Excuse the camera flash.)

Hill’s first trophy (albeit shared), The Hammersmith Cup for Junior Eights.

A close up of the Hammersmith Cup. It is engraved ‘N Hill’ as Hill’s first name was actually ‘Norman’.

There are few people left from Hill’s time at Auriol but Colin Cheney (who joined in 1945) remembers that at that time bad arguments were settled by impromptu boxing bouts in the clubroom and that Hill took part in at least one of these fights. Cheney also recalls that the Auriol clubroom was frequently strewn with motorcycle parts as members found it a convenient place to rebuild and maintain the only affordable form of motorised transport at the time, something that Hill would clearly have enjoyed. Speaking at the Auriol Club Dinner after winning his first major title in 1962, Hill said: “people ask me, ‘what’s the best thing about becoming World Champion?’ I say it’s that, when I visit Auriol, I am now known as ‘Graham Hill’ and not as ‘Johnny Ward’s cousin’.”

The ARC crew for Ghent pictured in Rowing Magazine n° 7, Spring 1950. It was Tony Kay, the stroke, that Hill boxed in the Auriol clubroom. History does not record what the dispute was about though I could imagine that Hill coveted the stroke seat.

Probably Auriol’s biggest contribution to Hill’s life was through the fact that it was where he met his wife, Bette, inevitably described as ‘long suffering’ due to her husband’s flirtatious character. Interviewed by Cars for the Connoisseur magazine in 2002, she recalled how she and Graham met: “in 1950 at a Boxing Day rowing regatta at Auriol Rowing Club at Hammersmith, while Graham was still in the Navy doing his National Service…. I worked with a girl who was engaged to one of his crew members and they had a Boxing Day engagement party which she took me along and things sort of clicked.”

Bette Hill, first lady of F1, died at 91.

Bette rowed for Stuart Ladies’ Rowing Club (now part of Lea RC) on the River Lea in East London and Graham coached her and her crewmates. They won the Women’s Head of the River for three consecutive years and Bette rowed for Britain in the Amsterdam International Regatta in 1952.

The 21-year-old Hill in his Auriol colours.

In 1952, even before the completion of his National Service, Hill applied to join one of the biggest and best clubs of the day, London RC. With his determination to win, he clearly did not wish to return to the small and relatively uncompetitive Auriol Rowing Club where high level success was unlikely. According to Chris Dodd’s history of LRC, Water Boiling Aft: John Pinches, the captain, thought quizzically about ‘gentlemen’ but like the cut of his jib and when Hill said that he was willing to ride his motorcycle from Chatham barracks each day for training, Pinches took him on……. From joining London until 1954 he rowed in twenty finals, usually as stroke, eight of which resulted in wins. He also stroked the Grand eight at Henley in 1953…..

Graham Hill in London RC cap and tie at Henley.

One of the major advantages of rowing at London was that it provided the impecunious young instrument maker with a bedroom in the clubhouse. In the 1954 Head of the River, Hill at 11 stone, 6 lbs / 160 lbs / 72.5 kg stroked the London boat that won the Vernon Trophy for the fastest Tideway crew. This was to be Hill’s last significant rowing achievement.

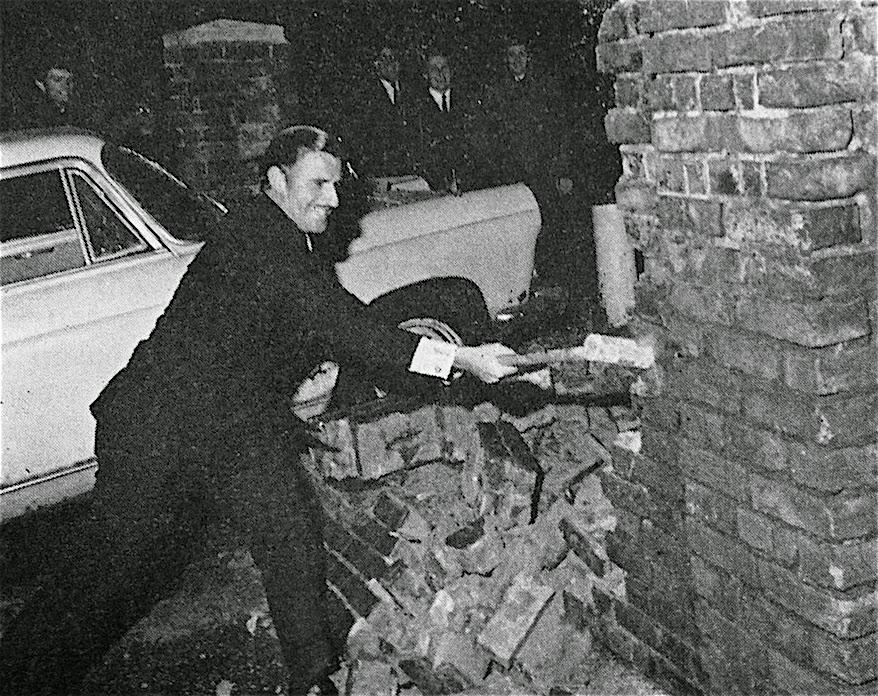

Chris Dodd: “throughout his racing career he continued to support rowing and London (and Auriol – TK), turning out to make accomplished speeches, beginning the demolition to make way for the extension to the boathouse by driving an old Morris car into the wall and opening the new Fairbairn room when the work was done. He famously adopted London’s blue-and-white colours on his racing helmet, attributing his driving success to what he learned from rowing.”

As a member of Hill’s first rowing club, now called Auriol Kensington, I may be biased, but I cannot but think that his motor racing colours should have been the dark green and light blue of Auriol.

Hill demolishing part of the London RC clubhouse in 1968. I think modern attitudes to driving a car into a brick wall for a stunt may be different.

In his autobiography, “Life at the Limit” (1969), Graham Hill wrote: “I really enjoyed my rowing. It really taught me a lot about myself and I also think it is a great character-building sport……. You have to have a lot of self-discipline and a great deal of determination. You not only get to know about yourself, but you get to know about other people – who you would like to have in a boat with you over the last quarter-mile of a race when you are all feeling absolutely finished. With seven other fellows relying on you, you can’t just give in. The self-discipline required for rowing and the ‘never say die’ attitude it bred obviously helped me through the difficult years that lay ahead …..”

Graham Hill liked painting in his spare time.

Hill did not pass his driving test until he was 24 years old and he himself described his first car as "a wreck. A budding racing driver should own such a car, as it teaches delicacy, poise and anticipation, mostly the latter I think!"

A crash at the 1969 United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen broke both his legs and interrupted his career. Typically, when asked soon after the crash if he wanted to pass on a message to his wife, Hill replied: "just tell her that I won't be dancing for two weeks."

Graham Hill, Jim Clark and …. friends.

Hill was known during the latter part of his career for his wit and became a popular personality – he was a regular guest on television and wrote a notably frank and witty autobiography, “Life at the Limit”, when recovering from his 1969 accident. A second autobiography which covered his career up until his retirement from racing, simply called “Graham”, was published posthumously in 1976.

Bette Hill and Janet Brise at Silverstone.

Hill married Bette in 1955; because he had spent all his money on his racing career, she paid for the wedding. They had two daughters, Brigitte and Samantha and a son, Damon.

The family lived in Mill Hill during the 1960s. The house now features an English Heritage blue plaque. During the early 1970s, Hill moved to Lyndhurst House in Shenley. Well known for throwing extravagant parties at his houses to which most of the GP paddock and other famous guests attended, Hill was universally popular.

Hill died on 29 November 1975 at the controls of his Piper PA-23 Aztec twin-engine light aircraft when it crashed near Arkley, Hertfordshire, while on a night approach to Elstree Airfield in thick fog. He was 46 years old. On board with him were five other members of the Embassy Hill team who all died: manager Ray Brimble, mechanics Tony Alcock and Terry Richards, driver Tony Brise and designer Andy Smallman. The party was returning from a car-testing session at the Paul Ricard Circuit in southern France.

“I saw on tv that a plane crashed and I think it’s daddy.” Damon Hill to his mother on November 29 1975.

The subsequent investigation revealed that Hill's aircraft, originally registered in the US as N6645Y, had been removed from the FAA register and at the time of the accident was "unregistered and stateless", despite still displaying its original markings. Furthermore, Hill's American FAA pilot certification had expired, as had his instrument rating. His UK IMC rating, which would have permitted him to fly in the weather conditions that prevailed at the time, was also out of date and invalid. Hill was effectively uninsured. The investigation into the crash was ultimately inconclusive, but pilot error was deemed the most likely explanation.

Sport Motor Racing. St. Albans, England. 5th December 1975. The Funeral of Grand Prix driver Graham Hill. The coffin, with helmet on top, is carried from St Albans Abbey by motor racing colleagues including Jackie Stewart (front left).

Hill's funeral was held at St Albans Abbey and he is buried at St Botolph's graveyard, Shenleybury in Shenley, Hertfordshire. The church has since been deconsecrated so the tomb now sits in a private garden.

After his death, Silverstone village, home to the track of the same name, named a road, Graham Hill, after him and there is a "Graham Hill Road" on The Shires estate in nearby Towcester. Graham Hill Bend at Brands Hatch is also named in his honour. A blue plaque commemorates Hill at 32 Parkside, in Mill Hill, London NW7. In Bourne, Lincolnshire, where Hill's former team BRM is based, a road called Graham Hill Way is named in his honour. Also a nursery school in Lusevera, Italy, was named in his honour.

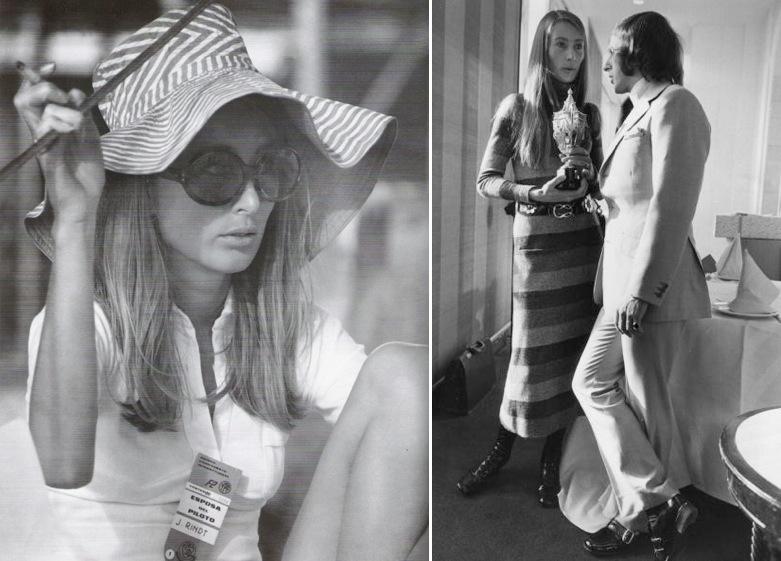

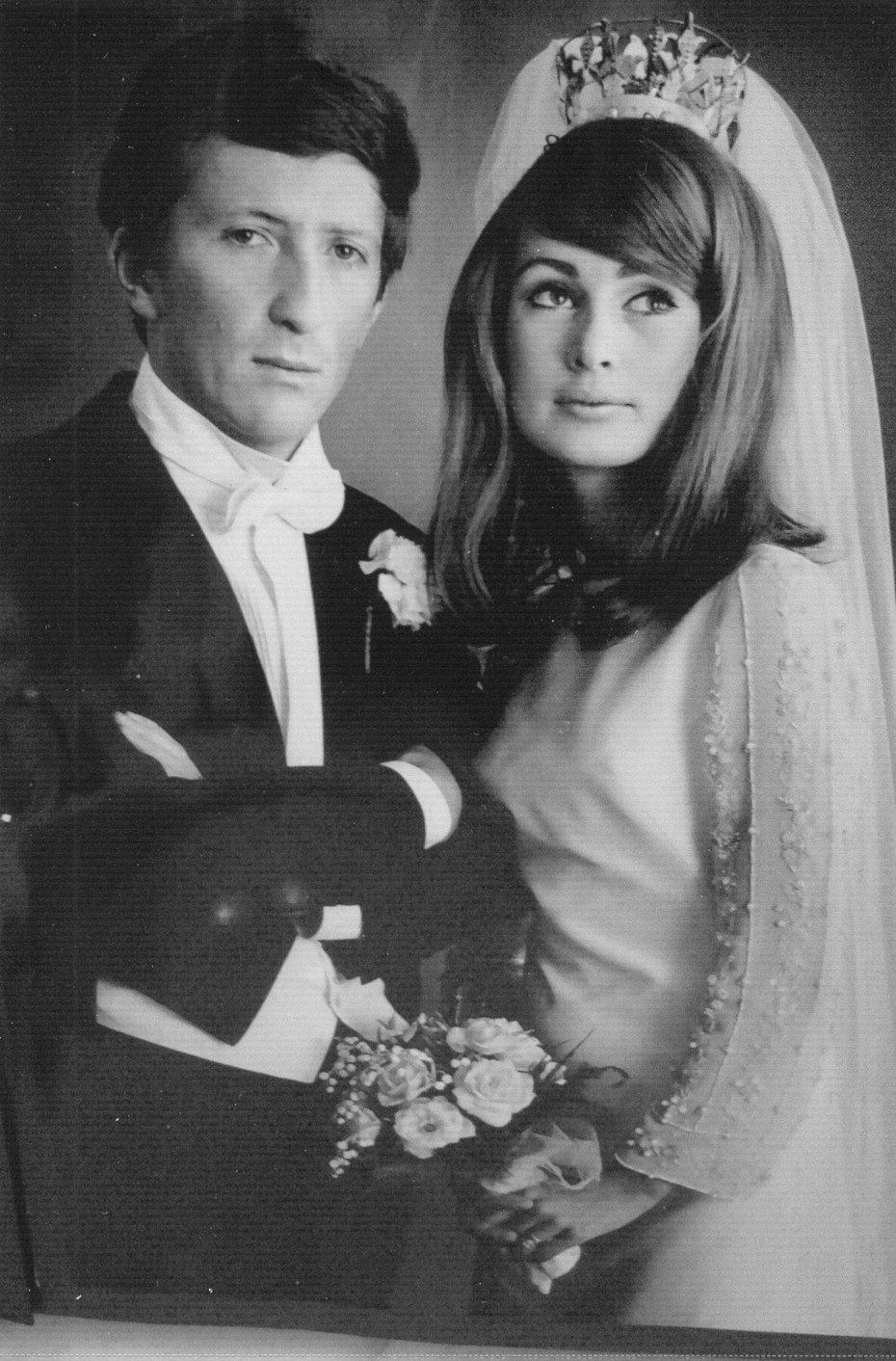

Jochen Rindt

What's the point of becoming F1 world champion if you never know it? In the answer to this question there’s the sense of incompleteness of Rindt's life.

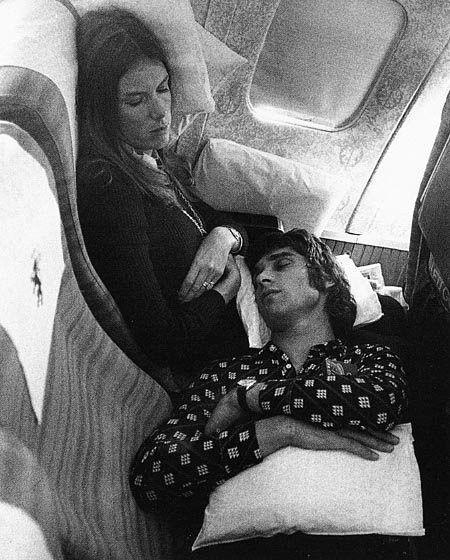

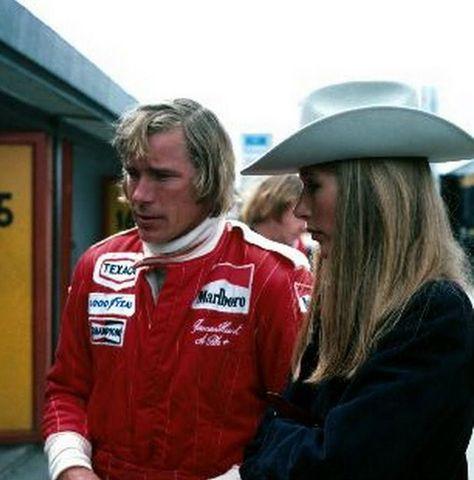

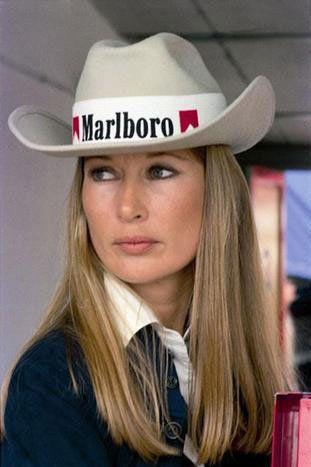

James Hunt and Nina Rindt in Spain in 1977. Photo by Sutton Motorsports.

Jochen Rindt was not as handsome and damned as James Hunt was but he had charisma.

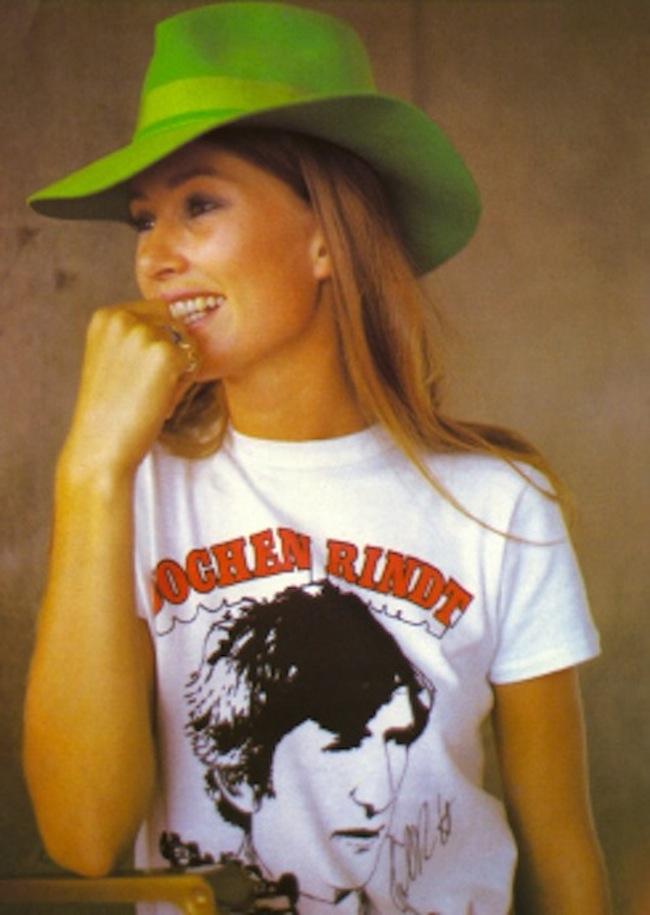

A daredevil driver with a gentle and reserved character, he married the style icon Nina Lincoln. And she said about him: “he never knew he was a world champion, he never really knew it, which was very sad.”

Nina Lincoln – Rindt.

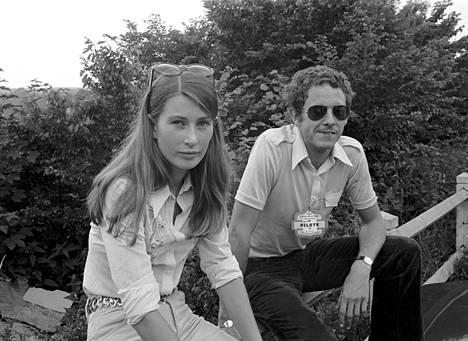

Nina and Jochen Rindt.

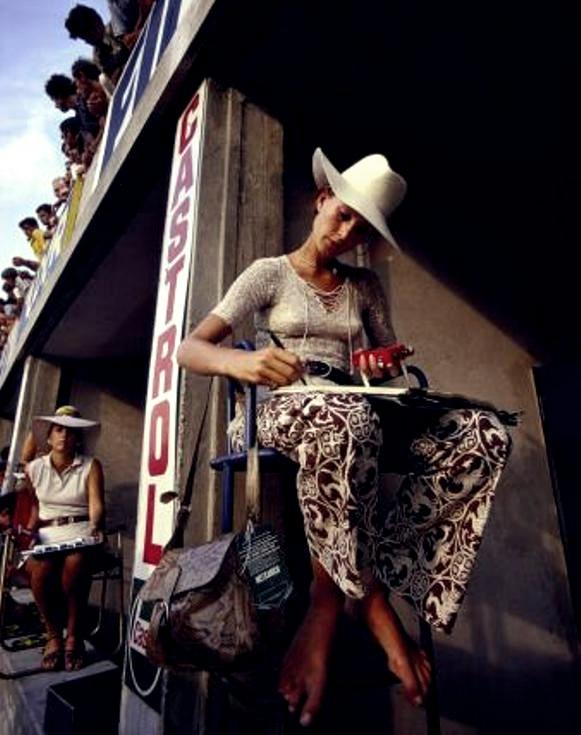

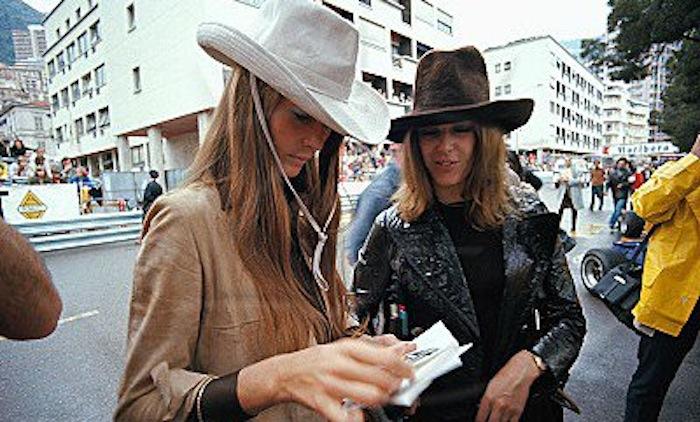

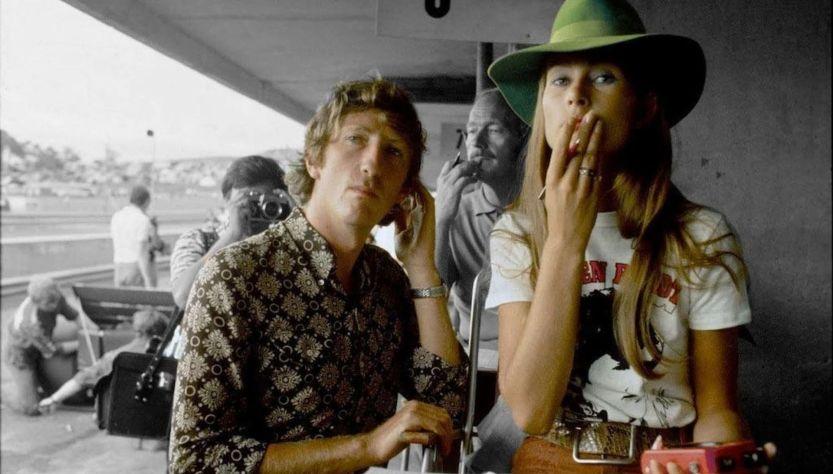

To be the girlfriends or wives of drivers like Rindt and his colleagues of the period, you needed a great fortitude. In 1970 Nina Rindt, Sally Courage, Patty McLaren, Betty Hill and Helen Stewart were meeting on the track and were smiling lightly. But serenity wouldn’t last long for all of them.

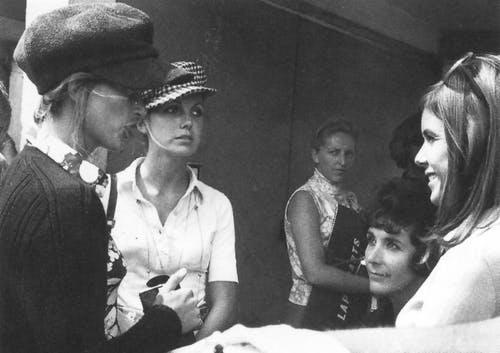

Nina Rindt, Sally Courage, Patty McLaren, Betty Hill and Helen Stewart in 1970.

Sally Courage.

Sally and Piers Courage, Monaco 1969.

Piers Courage and his wife Sally, Monaco.

Sally Courage, also known as lady Sarah Curzon, in London.

Nina Rindt, Sally Courage and Patty McLaren were sadly all widows before the year was out. Bruce McLaren died when his Can-Am car crashed on the Lavant straight, just before Woodcote corner, at Goodwood Circuit on 2 June 1970. Piers Courage died at Zandvoort circuit on 21 June 1970, after his front suspension or steering broke on the bump at Tunnel Oost causing a fatal crash. Jochen Rindt died on 5 September 1970.

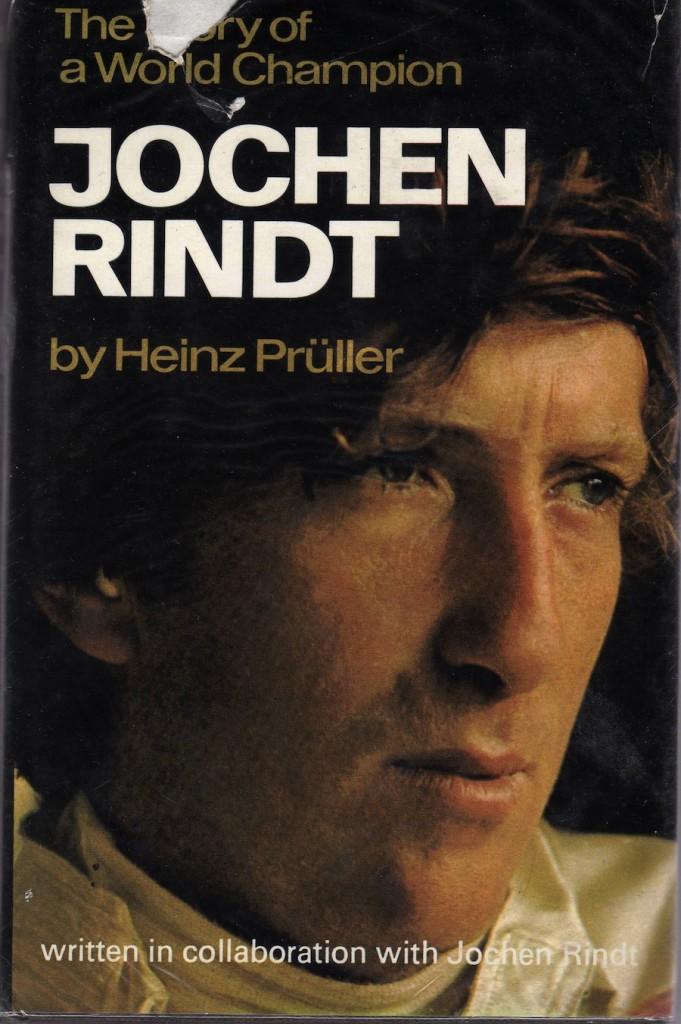

Jochen Rindt: the story of a World Champion. By Heinz Prüller, 1972.

In the Clermont-Ferrand paddock, during the French GP meeting of July 1970, Jochen Rindt sat with his fellow-Austrian journalist Heinz Prüller in the Firestone caravan. They had collaborated on a book four years earlier and now that Rindt was romping away with the World Championship, they agreed to write another. Nine weeks later, Jochen was dead. After seeking the approval of his widow Nina, Prüller went ahead with the book about her husband. Forty years on, David Tremayne’s 2010 in-depth biography of Rindt prompts one to pull Prüller’s book down from the shelf once more and see if it has stood the test of time.

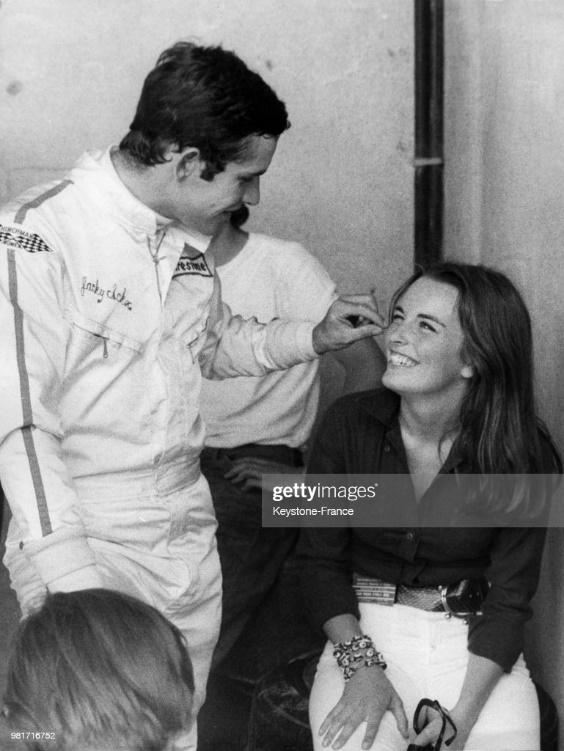

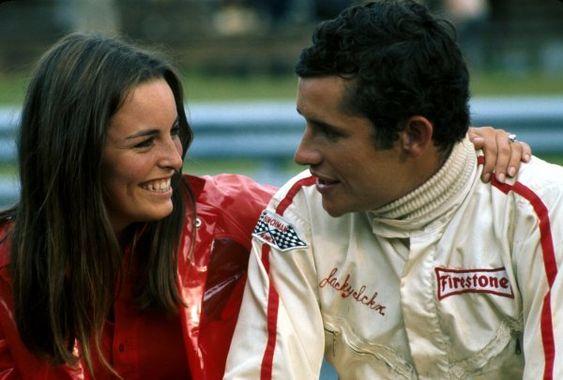

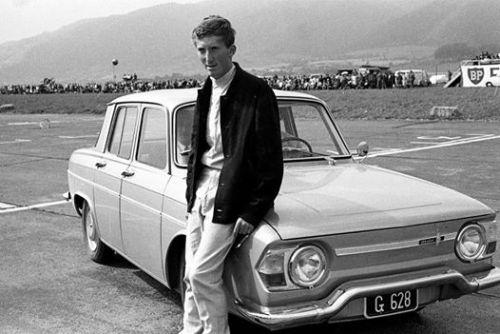

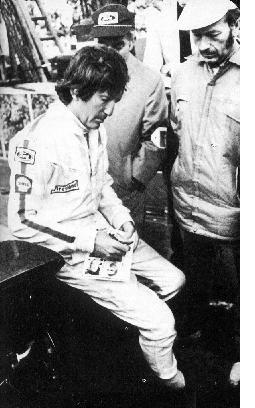

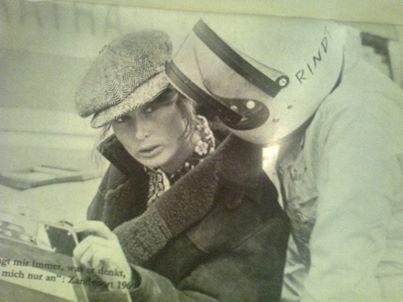

Jochen Rindt with Jackie Stewart.

It cannot have been an easy task for Prüller to write his great friend’s story when the wound was so raw, any more than it was for Jackie Stewart to provide a foreword, a role he also performed for Tremayne.

Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt.

Here, Stewart writes at length about the only driver he would place alongside Jim Clark as being “truly great.” He recalls their famous duel at Silverstone in 1969 with genuine affection and makes the telling observation that Rindt matured as a driver after his maiden GP win, at Watkins Glen the same year: “he had come away from the point of having to win races.”

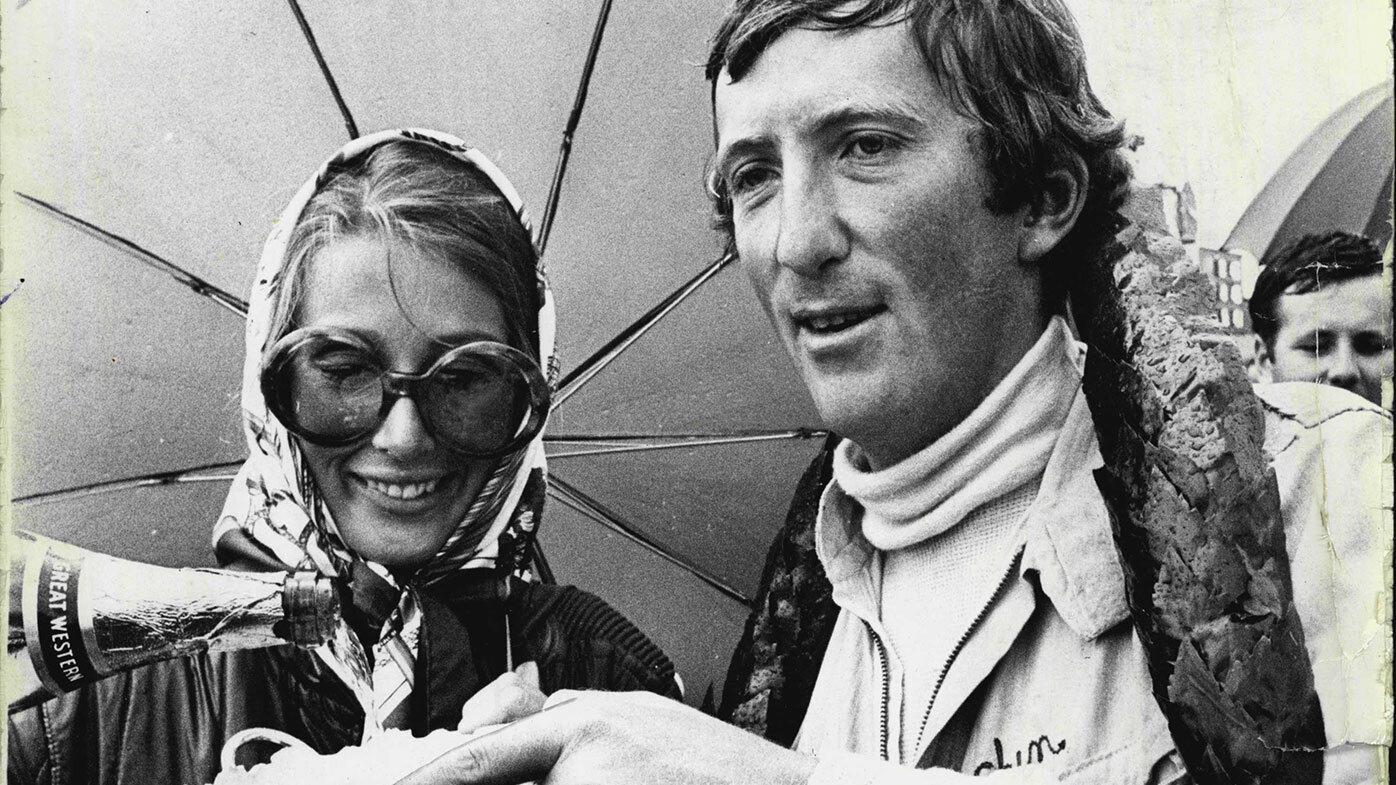

Jochen and Nina Rindt celebrating after Jochen’s win in Sydney in 1969. Photo by Fairfax Media.

Several features point to the book having been aimed at the man in the street, someone who would have been unfamiliar with Rindt until his final, dominant season, rather than the serious enthusiast.

Jochen Rindt in action.

There is no index, just a perfunctory list of World Champions and two-thirds of the text is devoted to the last two years of Rindt’s life, when he was very much the star at Lotus. This may indeed have helped the book enjoy such success; it was translated from German into both English (by Peter Easton) and French and ran to several editions.

Nina Rindt.

But the first third of the book is unappetizing, particularly when compared with the depth to which Tremayne delves into Rindt’s formative years and development as a driver.

Perhaps Prüller’s 1966 book covered Rindt’s early days in more depth, but here they are dealt with in summary fashion. His three years at Cooper are covered in fewer than 25 paragraphs. Indeed, each of his 1965 Grands Prix receive no more than a sentence. Even the first time that Rindt led a World Championship race, amid the chaos and torrential rain of Spa the following year, warrants only a paragraph.

Things get much more interesting when we meet Nina. Prüller even knows what she charged Vogue for modelling assignments.

A suitably wintry Jochen Rindt, on skis. Source memorytso.hautetfort.com.

“Jochen was quite impossible at twenty-two,” she tells him. “He tried to impress me with his money and his racing, but I made it clear I wasn’t interested in either.” A two-year estrangement ended when she was modelling in New York in January 1967 and Rindt was passing through on his way to Daytona. They married in early March, on his last race-free weekend.

Jochen Rindt with his wife Nina in 1969.

The Lotus chapters make captivating reading.

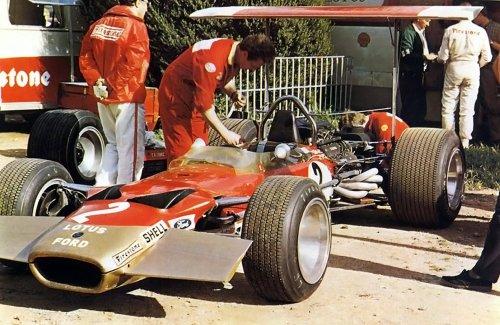

Jochen Rindt's red Lotus.

Prüller claims that Lotus chief Colin Chapman wanted Mario Andretti to lead the team in 1969 and only moved for Jochen when Mario decided to prioritize USAC. Rindt’s contract was not signed until May, having been negotiated by his manager, one Bernie Ecclestone, whose negotiating prowess even 40 years ago was second to none. Jochen tells Bernie, “if you had negotiated with Colin for another five minutes, he would probably have sold you his factory as well.”

Jochen Rindt sticks some stickers on his car. Source abcpix.net.

There is just a hint of what another latter-day giant of the sport would prove capable. Ron Dennis, or Ronald as Prüller introduces him, was chief mechanic to Rindt at Cooper and, claims the author, moved to Brabham at the behest of the driver: “Ron soon became of great help to Jack.“

Prüller has a special way with words and of recording the observations of those around him. He describes Indianapolis thus: “to the Americans, because of its startlingly high prize money, its speeds and its accident-proneness, it signifies at one and the same time a gold mine, a cathedral and a sacrificial altar.”

And this is Chapman, on how he copes with the unfortunate accident record of his cars: “when someone is killed in one of my cars, then I accept responsibility, but not blame. Unfortunately things do go wrong, not for reasons of negligence, but because of ignorance or human fallibility, both of which are virtually impossible to eliminate.”

Rindt’s sense of superiority over his fellow drivers — an essential part, surely, of a champion’s attitude — shines through. When Ecclestone tells him that the front row-sitting Matra of Johnny Servoz-Gavin will not last 80 laps around Monaco, Jochen replies, “the Matra might last but Johnny won’t last” and indeed the Frenchman clouted the chicane on the first lap and retired shortly afterwards.

Jochen Rindt in the Lotus 49 on his way to win the Monaco GP on 10 May 1970. Image credit unknown.

Nina Rindt at Zeltweg, Austria, in 1970. Photo by Rainer Schlegelmilch.

And, at the race where driver and writer agreed to collaborate on the book, Rindt won the 1970 French Grand Prix by exploiting a weakness he perceived in Chris Amon and “decided to drive in such a way as to demoralize him, psychologically speaking.”

Through that year, Rindt wrestled with conflicting emotions.

Nina Rindt and Piers Courage at Clermont Ferrand in 1969.

His former Cooper team mate, Bruce McLaren, crashed fatally and his great friend Piers Courage was killed during the Dutch Grand Prix, yet this was where the Lotus 72 first came good and Rindt won from pole. He queried why he should suddenly be the beneficiary of good fortune, most notably when he only beat Jack Brabham at Brands Hatch because the Australian ran out of fuel on the last lap. Rindt had rarely enjoyed such luck in Formula One before and now others were running out of luck altogether.