In the 1960s and 1970s, even more than now, the car was a socio-economic status but also represented a whole vision of life of those who owned it. To the car were linked the most eminent personalities of that era. Reading the story of these men, of these giants of whom the mold has been lost, you have the idea of what is meant by Italian inventiveness. Meaning and trajectories of life of these enthusiasts workers make us proud and sad at the same time. Where are today such men? And what inhuman effort Ferrari had to make to become the best with such antagonists. And to beat the British, equally hardworking and brilliant. The works of these incomparable artisans ooze the charism of the history of these lives, generously sacrificed on the altar of passion for cars, for beauty. This is indubitably the Italian miracle. The gallery of characters that will be treated in this article represents the spine of the Italian automotive industry of golden years, the unrepeteable ones. Each of them, at different levels, has made a contribution to the building of this fantastic world we all love so much. For each of them a book would be needed. They were using a different vocabulary than ours as different was for them the meaning of the words work, determination, patience, abnegation, sacrifice, pain, joy, love, sadness, responsibility, loyalty, friendship, simplicity, happiness, modesty. Or just life.

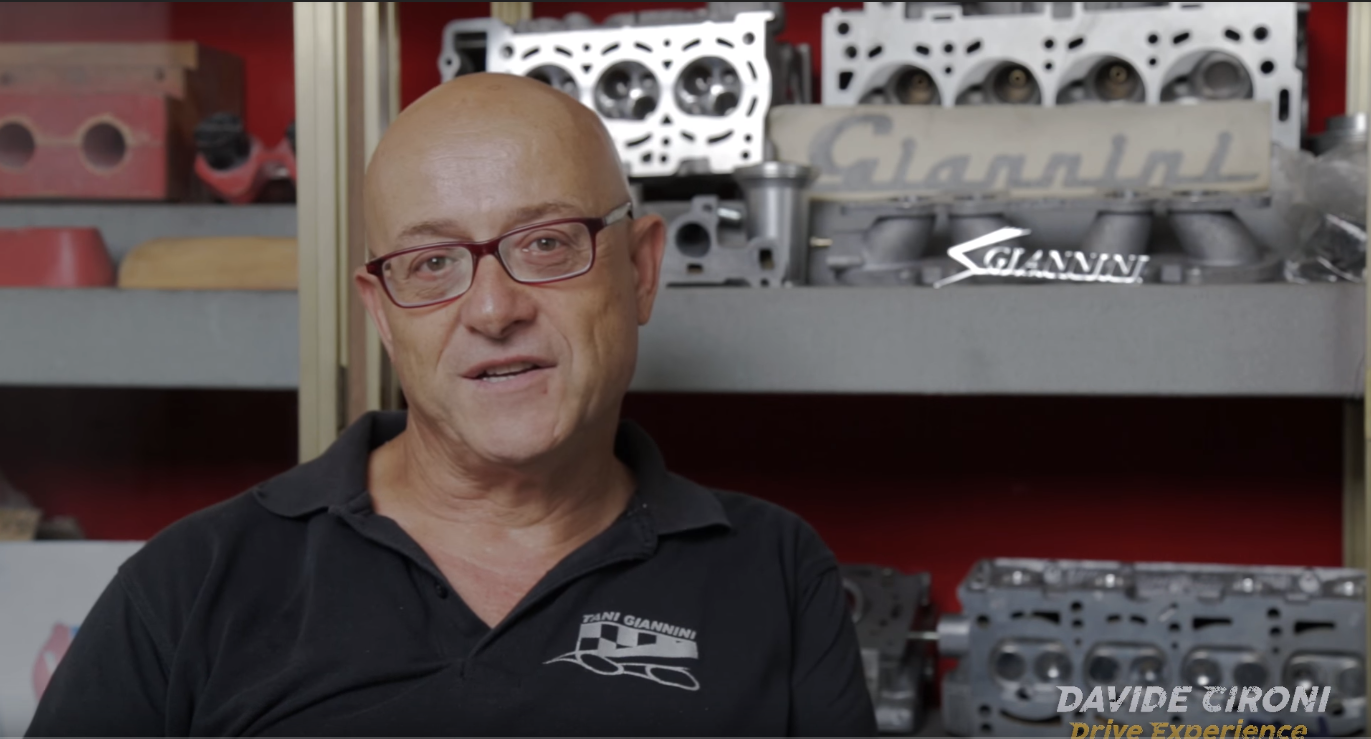

On the learning journey into this ancient world it has been with us again Davide Cironi, whose portrait is so described by a journalist: “an old Porsche 930 turbo, black as pitch, slips at a steady pace along a lunar landscape. With an animalistic woof the car climbs towards narrow streets and hairpin bends, terrorizing all animal life for a few kilometres. In the background sharp ridges, interspersed with tracts of brown land and rocks. All the evidence would suggest an 80s American movie that celebrates the extreme freedom of life on the road, maybe set among the Rocky Mountains. You’d expect that who drives that menacing coupe is a big boy, a bit of a thug, with relative leather jacket and dark Ray-Ban. Instead, to get out of the car is a figure that has nothing yankee. The sunglasses are there, but for the rest Davide Cironi – tall, thin body, curly hair – could be your friend from the secondary school. Also the landscape is not that of Colorado but belongs to the stunning backdrop of the Gran Sasso. The scene, then, is not from a movie, but from one of the videos of Drive Experience, the most famous and popular among fans of sports cars You Tube channel in Italian, of which Davide is the founder. The success of his formula cannot be explained by the volatile logics of social phenomena, that is at the same time tangible and hard to define. With his romantic, involving, totally visceral way to tell motor racing, more than just a simple tester, Cironi is an art critic of uncompromising tastes and of trenchant opinions, who looks down on everything but what is source of pure driving emotion. Through his video-tests he manages to give back the smell of leather seats, the moment of panic of when you believe to have taken a curve too fast, the fulfillment of doing a successful over-steer.”

«When I realized that a lot of people liked my point of view and my way of telling motorsport, I made a fine trade of it. What I care about is to enrich other people from the cultural point of view with our contents, to give justice to historical figures who haven’t had it, to make known our national motoring culture more deeply, to let fall in love with the cars that I love who doesn’t know them». Davide Cironi

«I like the idea to put myself at the service of real world rediscovery. I like to go get these people in the very place that I hate the most, Internet, the kingdom of the intangible, and to bring them back in the real world. Books, live events, Academy, real sharing (not only social), everything is aimed at achieving the return of a world that one can touch and experience firsthand. Even when we don’t take directly the people to be reunited with the real world through “live” initiatives, we do it making somebody be willing to buy a nice car, or simply to lift the portcullis and go driving the one they already have. It sounds pretty thin, but it’s a lot.» Davide Cironi

Attilio Giannini

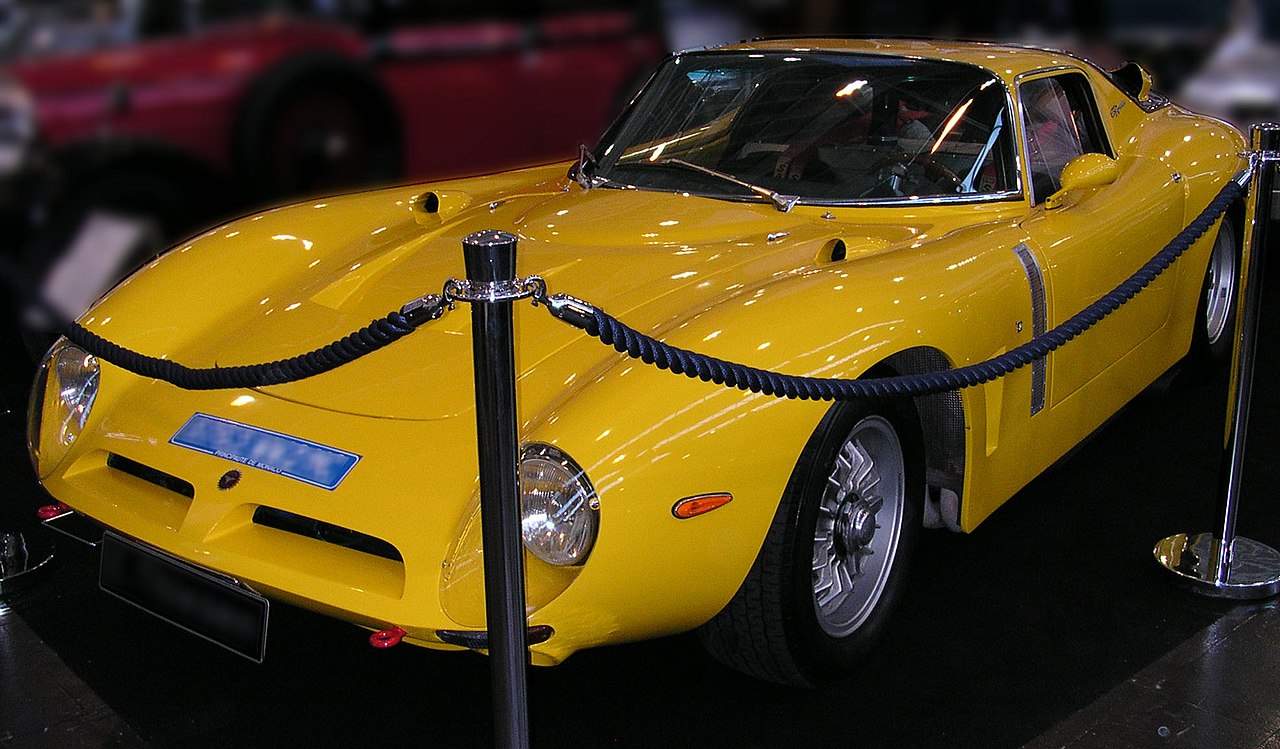

Giannini Automobili S.p.A. is a Rome-based Italian automotive company, founded in 1920 by the brothers Attilio and Domenico Giannini. Born as mechanical-repair specialized workshop, during the thirties the Giannini is challenging itself with the elaboration of low-powered cars, in particular of the models Fiat Balilla and Topolino, not by just modifying the engine, but also set-up and brakes. After the second world war the Giannini brothers begin their own production of engines.

In 1948, abandoned the motor transport sector, they test themselves in the field that works best for them, that of races. During the decade the company conducts various trade policies, including the opening of dealerships with attacked workshops, sales on behalf of a third party, sales for the account of the same Fiat. In 1953, a motorbike parenthesis sees the Giannini committed to make the racing prototype Moto Guzzi 4, better know as "La Romana". For various reasons, however and despite the good commercial results, the firm finds itself in very serious economic difficulties that lead it in 1961 to the closure. The two brothers and their respective children find themselves in such disagreement that they will create two new separate companies. Thus were born the Costruzioni Meccaniche Giannini S.p.A. of Attilio Giannini and the Giannini Automobili S.p.A. of Domenico Giannini.

Costruzioni Meccaniche Giannini S.p.A.

The Costruzioni Meccaniche Giannini S.p.A., with head office in via Tiburtina, continues in the field of the elaborations, engine and prototypes design, completely renouncing to less valuable assistance and maintenance services. This choice, despite the many good works done, will prove to be fatal for its future. The Costruzioni Meccaniche Giannini S.p.A. will definitly close its doors in 1971. The old sheds located at Setteville di Guidonia in via Vittorio Alfieri, now owned by the municipality, are still existent but in a state of complete abandonment.

Giannini Automobili S.p.A.

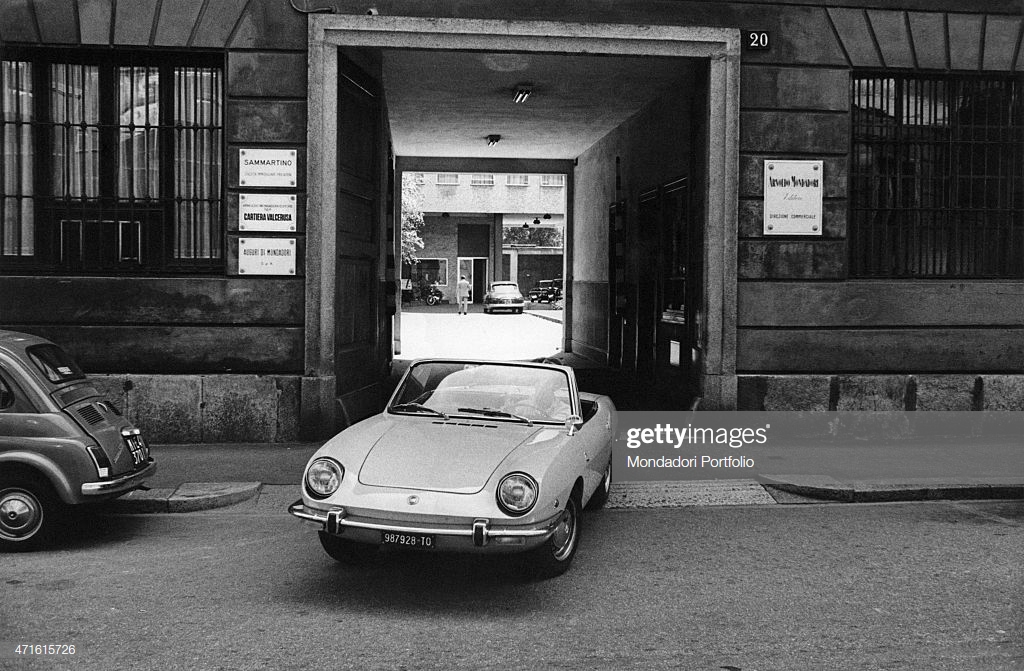

The Giannini Automobili S.p.A. initially strenghtens the commercial network and the repair and maintenance workshops, while customizations are reduced drastically to small interventions. Later, from 1963, the elaborations of standard cars and the sale of conversion kits begin again: in that year is presented the elaborated versions of the little Fiat 500, the Fiat 590 Gt and the 500 TV. Together with these, other models are produced, mainly of the Turin company.

The Sixties are excellent, between elaborations and participations in competitions, even though on 16 March 1967 Domenico Giannini dies for a heart attack. After his death a new period opens for the company, which will be found to deal with big problems of conduction and organization, that would lead administrators of the time to call an outside source to recover full functionality. It’s called to this delicate task the lawyer Volfango Polverelli who, not only restores the company but also becomes its partner and, in 1973, its sole owner. The new management brings big changes including a new location and the entry in the management structure of the sons of Polverelli; Gabriele, Gaetano, and Giacomo, each one responsible for his own sector.

The new tunings report to the engineer Armando Palanca, known both in the automotive sector and in the aeronautical one. They’re the early 1980s. The advent of Palanca gives a new input to the Giannini, new models are taken into account and elaborated like 126, Ritmo and Panda and, in parallel, direct and indirect participations to sporting events increase. The world of elaboration, that so many companies had undertaken, was however destined to descend into an irreversible crisis. The main reasons were ever-increasing costs and the fact that the largest car manufacturers began to create models in various versions themselves. This crisis is amplified by the death of Volfango Polverelli on 13 July 1984. Following the continuing crisis, in 1985 it is decided to completely abandon tuning to switch to the field of bodywork; so new look customisations of different cars such as Uno, Tipo and Panda start. The changes largely concern tapestries, saddleries, accessories, but also paintings, bumpers and ailerons.

Giannini is also a custom body shop which collaborates with FIAT, authorities and institutions, operating on specialised vehicles, vintage cars and last models of FCA group, also obtaining historical assistance orders by Guardia di Finanza and Ministero dell'Interno. At the end of October 2016 Polverelli family, owner of the brand, opened the Giannini Museum at the operations centre of via delle Idrovore della Magliana in Rome; present in the structure models such as the 590 Corsa Replica, the 650NP, the Giaur 750, the Punto Drago, the Uno Turbo Torino. Giannini’s tuned cars have characterized in the 60s, 70s and also 80s the races reserved to elaborated cars. In the sixties was typical the rivalry between the many elaborated versions of Giannini 500 and Abarth cars. From 1983 to 1984 the Giannini also formally won two world sport titles in the C-Junior category.

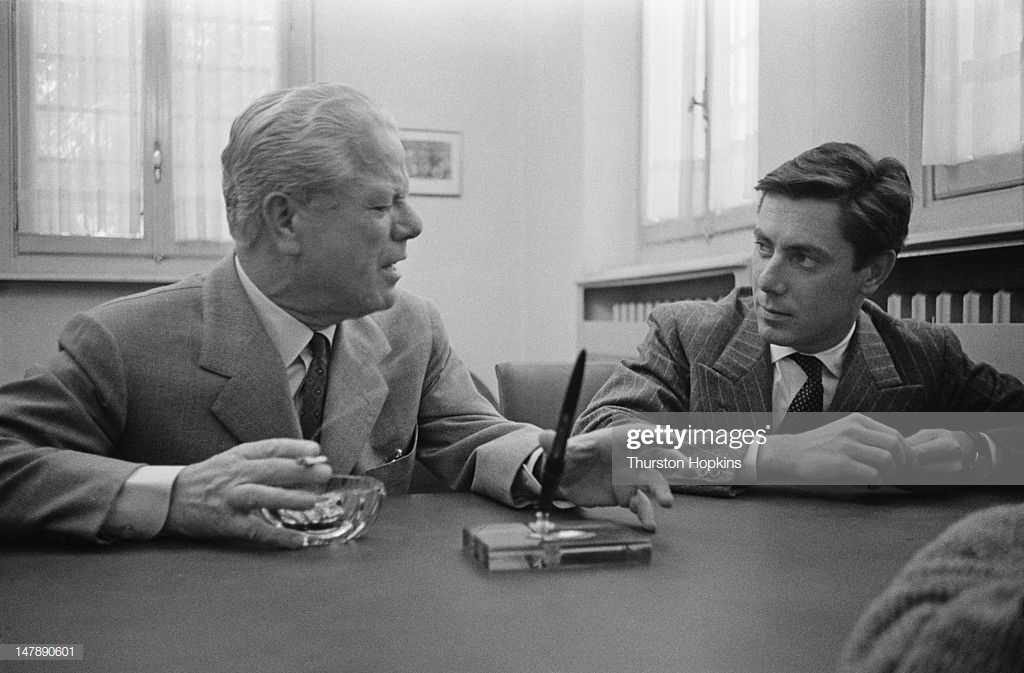

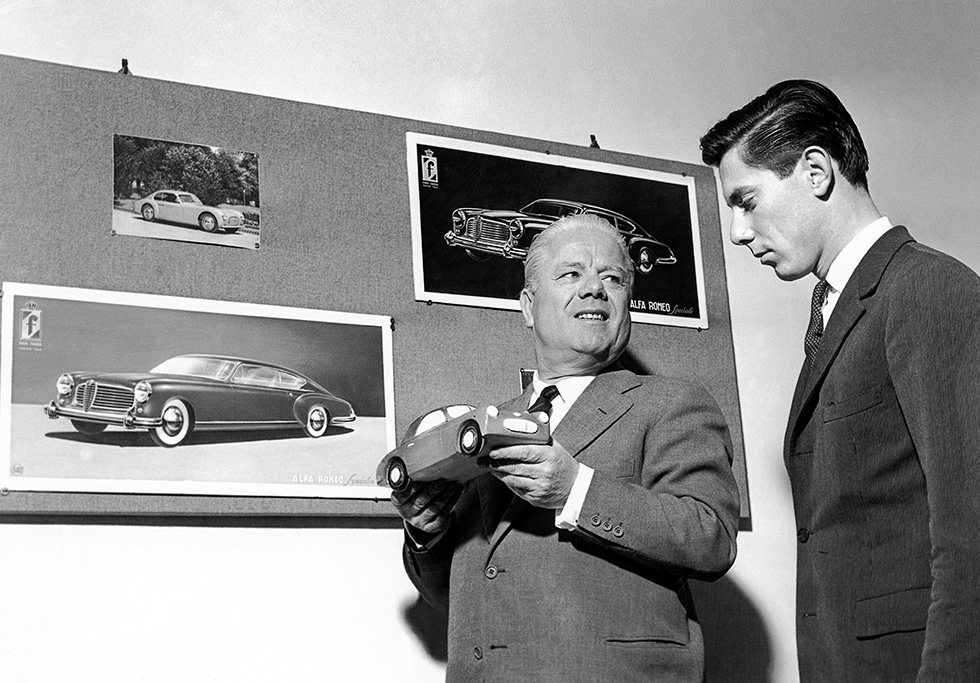

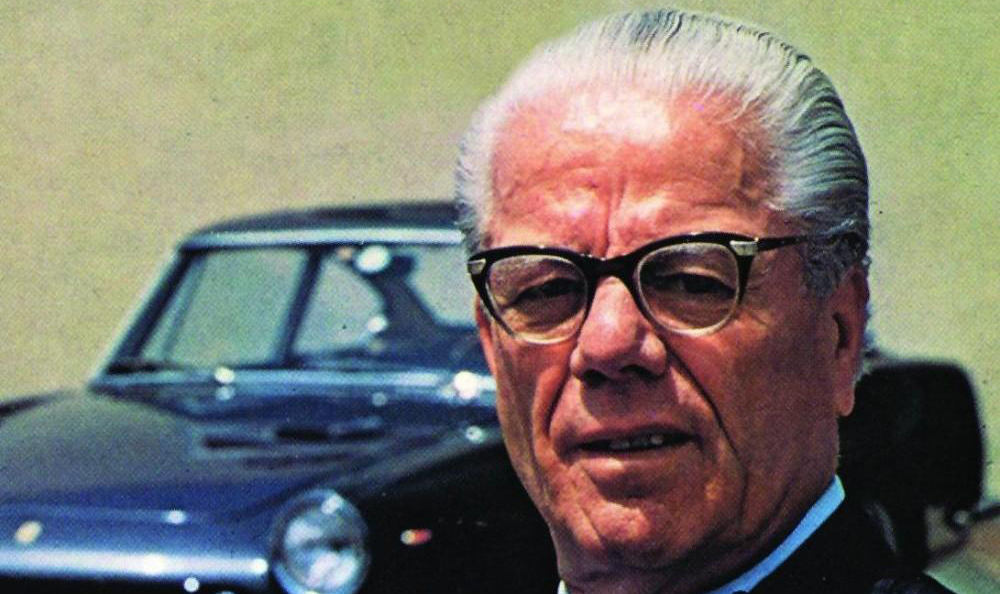

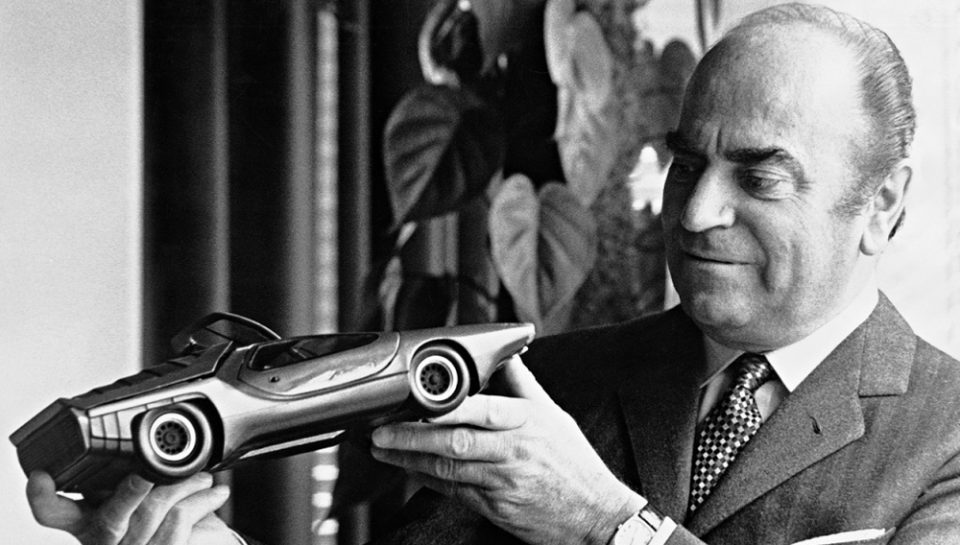

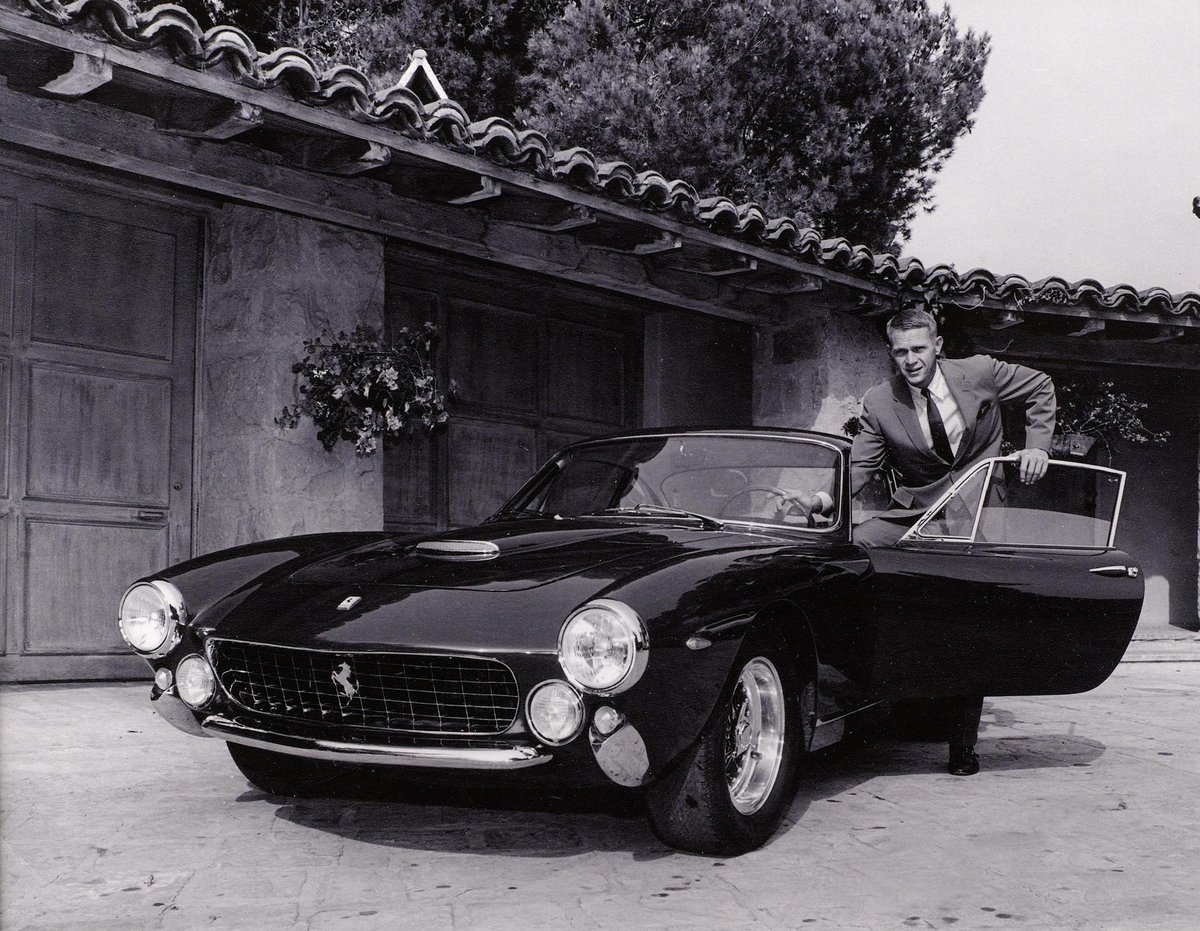

Battista (Pinin) and Sergio Farina

Battista "Pinin" Farina (later Battista Pininfarina; 2 November 1893, Cortanza d’Asti, Italy – 3 April 1966, Lausanne, Switzerland) was an automobile designer and the founder of the Carrozzeria Pininfarina coachbuilding company, a name associated with many of the best-known postwar sports cars.

Battista, designer of some of the most beautiful cars ever made, was the tenth of eleven children and his nickname, "Pinin" (the youngest / smallest (brother), in Piedmontese dialect) was referred to his being the baby of the family. He started working in his brother Giovanni's body shop at the age of 12 and it was there that his interest in cars was born.

He stayed at Giovanni's Stabilimenti Industriali Farina for decades, learning bodywork and beginning to design his own cars. He formed Carrozzeria Pinin Farina in 1930 to focus on design and construction of new car bodies and quickly gained prominence. Only Carrozzeria Touring was more sought-after in the 1930s.

At Pininfarina sheer passion has always held sway over reason. In its heyday the company’s skill in blending engineering and beauty was unmatched. Carrozzeria Pininfarina swiftly prospered as a body manufacturer and was noted for its adherence and understanding of aerodynamics, an emerging science in the 1930s, which lent its cars a swooping futuristic flamboyance that was also highly functional.

|

|

Having started his own car company in 1947, Enzo Ferrari had flirted with most of Italy’s design houses but decided that Pininfarina was the one he really wanted to work with. This gave rise to one of the car business’s most celebrated anecdotes. Mr Farina was too proud to travel to Mr Ferrari’s home in Modena and Mr Ferrari, in turn, was too stubborn to meet Mr Farina in Turin.

So these two soon-to-be giants of Italian design and engineering agreed to meet in the middle, in a restaurant in Tortona. Fortunately for car lovers the world over the meeting was a success. Starting with the 212 Inter in 1952, Pininfarina went on to design hundreds of Ferraris over the next 60 years.

His work for Ferrari would become his most famous, though much of it was managed by his son Sergio, who ran the firm until shortly before his death in Turin, on 3 July 2012 aged 85. Sergio Pininfarina, born Sergio Farina, (8 September 1926 – 3 July 2012) was born in Turin.

After joining his father at Carrozzeria Pininfarina he quickly became integral to the company and, during his career, oversaw many of the designs (particularly Ferraris) for which the company is famous. In 1961, by decree of the Italian president, his family surname was changed from Farina to Pininfarina to match that of the company.

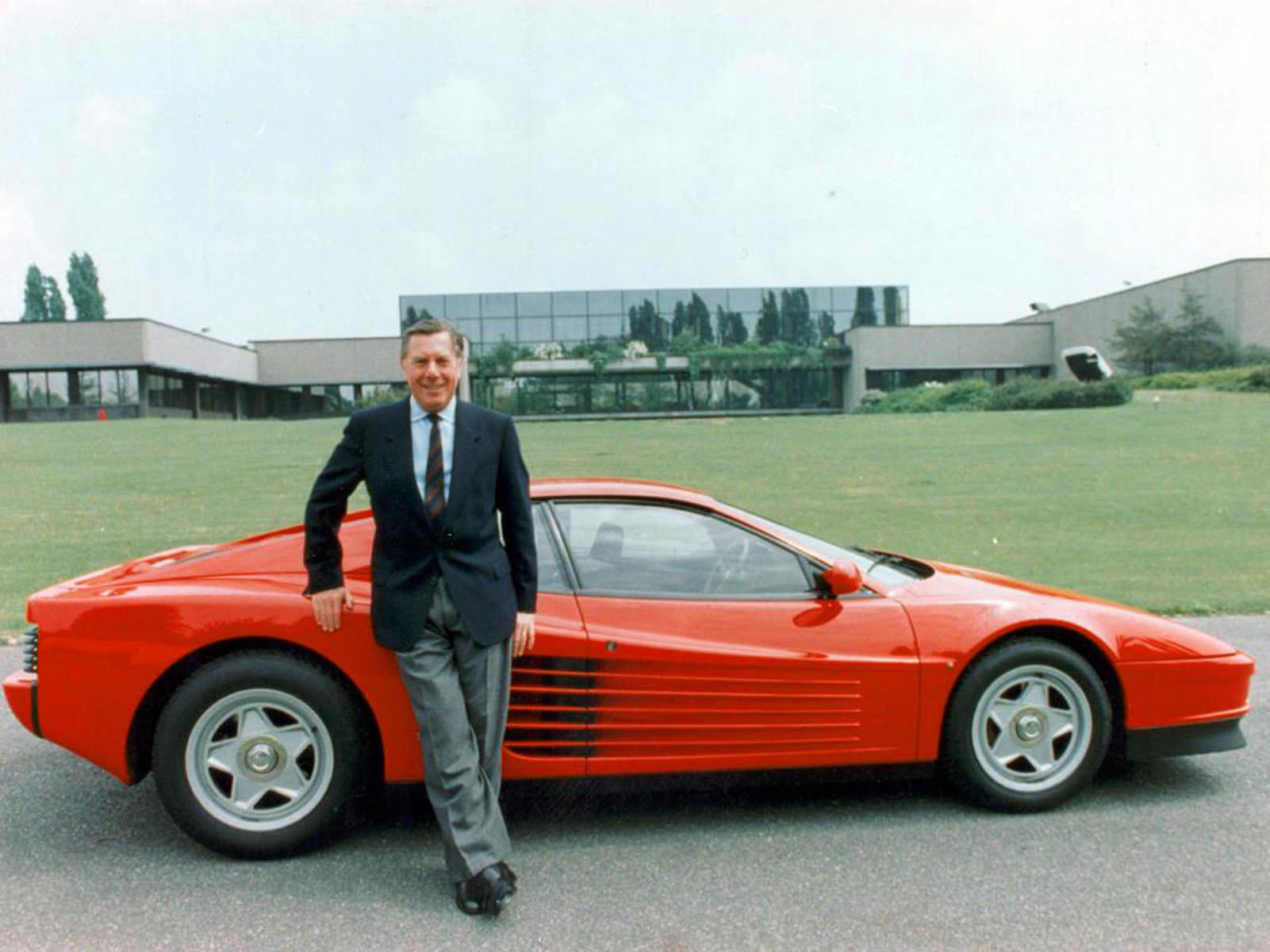

![]()

In 1965 it was Sergio Pininfarina who personally persuaded Enzo Ferrari to adopt a "mid-engined" configuration for a new line of road cars, with the engine positioned behind the driver but ahead of the rear wheels.

The resulting Ferrari Dino Berlinetta Speciale was presented at the Paris Motor Show in October. Some time in the early 1950s, Stabilimenti Farina was absorbed into the by now much larger Carrozzeria Pininfarina. The last design personally attributed to Battista was the 1600 Duetto for Alfa Romeo in 1966.

He officially changed his name to "Battista Pininfarina" in 1961, authorized by the President of the Italian Republic. His nephew, Nino Farina, was the first F1 world champion. Battista was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2004.

It’s only in the past five years that the company has set up its own centro stile (design house), presided over by Mr Flavio Manzoni, although officially the partnership continues.

Pininfarina clothed Ferrari’s magnificent chassis and power trains in a series of breathtaking bodies, most of which were fabricated by the gifted Modenese artisan Mr Sergio Scaglietti. For students of design the 1950s and 1960s represent the car industry’s most fertile period.

It was an era in which designers were unencumbered by legislative demands and safety considerations. Bertone, Fantuzzi, Ghia and Vignale all worked wonders, yet Pininfarina was undoubtedly king.

|

|

Alfa Romeo’s gorgeous Giulietta Spider, Lancia’s Aurelia B24 Spider and Flaminia Coupé, Maserati’s A6 GCS and Ferrari’s 250 PF Cabriolet and 375 MM – to name but two Prancing Horse models – are regarded as some of the most sublime motor cars ever made.

|

|

Pininfarina exported a winning dose of “la dolce vita” to less-than-glamorous French and British provincial towns. Even now, on the 50th anniversary of his passing, Battista Farina is cited as the single most influential car designer of all time. To put it another way, if the car was the defining invention of the 20th century then Mr Battista Pininfarina was its Picasso.

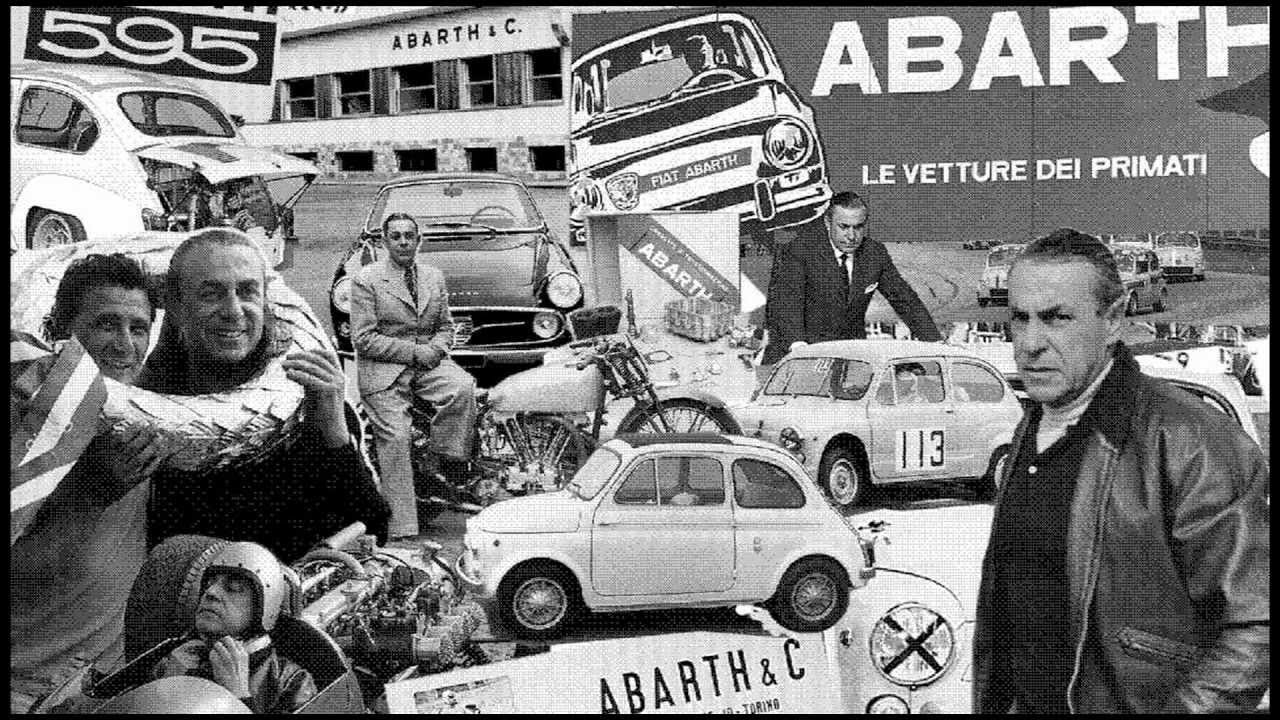

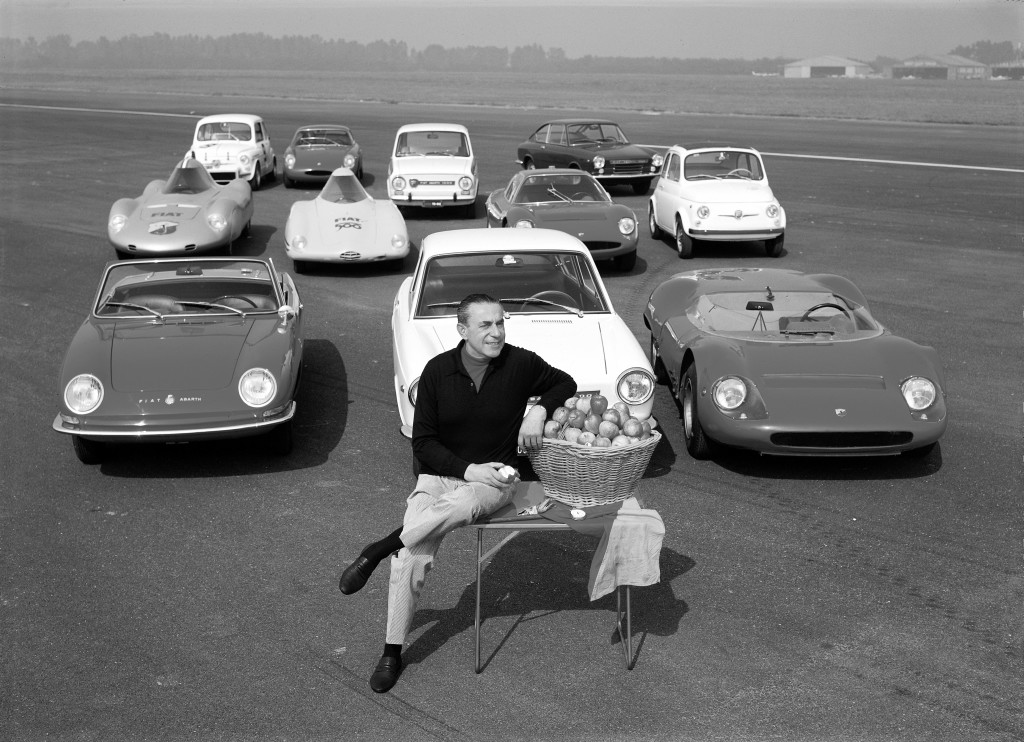

Carlo Abarth

Carlo Abarth (15 November 1908 – 24 October 1979), born Karl Albert Abarth, was an automobile designer born in Austria but later naturalized as an Italian citizen; and at this time his first name Karl was changed to its Italian equivalent of Carlo.

Abarth was born in Vienna, during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As a teenager he worked for Castagna in Italy (1925–27), designing motorbike and bicycle chassis.

Back in Austria, he worked for Motor Thun and Joseph Opawsky (1927–34) and raced motorbikes, winning his first race on a James Cycle in Salzburg on 29 July 1928. He would be European champion five times, along with continuing his engineering.

After a serious accident in Linz he abandoned motorbike racing and designed a sidecar (1933), with which he managed to beat the Orient Express railway on the 1,300-kilometre (810 mi) stretch from Vienna to Ostend (1934).

He moved permanently to Italy in 1934, where he met Ferdinand Porsche's son-in-law Anton Piëch and married his secretary.

In 1939 Abarth was long hospitalized and had his racing career end, due to a racing accident in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. He remained in that country (with some visits in Austria and Italy) until the war was over. Following this he moved to Merano, from where his ancestors originated.

Abarth got to know both Tazio Nuvolari and the family-friend Ferry Porsche and, together with engineer Rudolf Hruska and Piero Dusio, he established the Compagnia Industriale Sportiva Italia (CIS Italia, later becoming Cisitalia), having the Italian Porsche Konstruktionen agency (1943–48).

The CIS Italia project ended when Dusio moved to Argentina (1949). Abarth then founded the Abarth & C. company with Cisitalia racing driver Guido Scagliarini in Bologna (31 March 1949), using his astrological sign, the scorpion, as the company logo.

The same year, Abarth & Co moved to Turin. Financed by Scagliarini's father Armando Scagliarini, the company made racing cars and became a major supplier of high-performance exhaust pipes that still are in production as Abarth.

On 20 October 1965, Abarth personally set various speed records at the Autodromo Nazionale Monza. He sold the company on 31 July 1971 to Fiat, although he continued to manage it as a CEO for a period.

Later he moved back to Vienna, where he died in 1979. Carlo was married three times. His first wife was the secretary of Anton Piëch in Vienna. He married his second wife, Nadina Abarth-Žerjav, in 1949. They lived together in northern Italy until 1966 and divorced in 1979.

The same year, about six weeks before his death, Abarth married his third wife, Anneliese, who continues to head the Carlo Abarth Foundation and wrote one of his biographies in 2010.

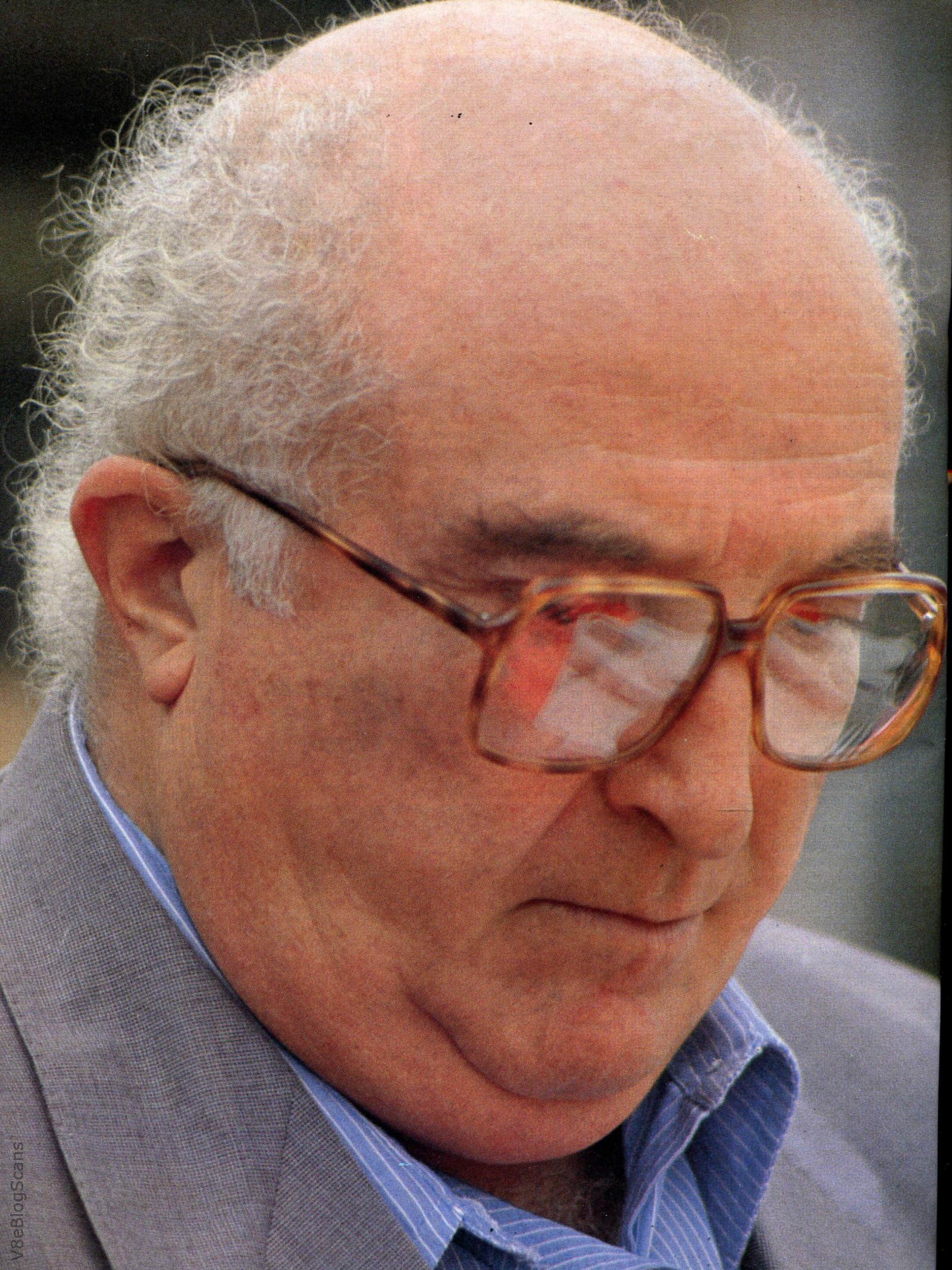

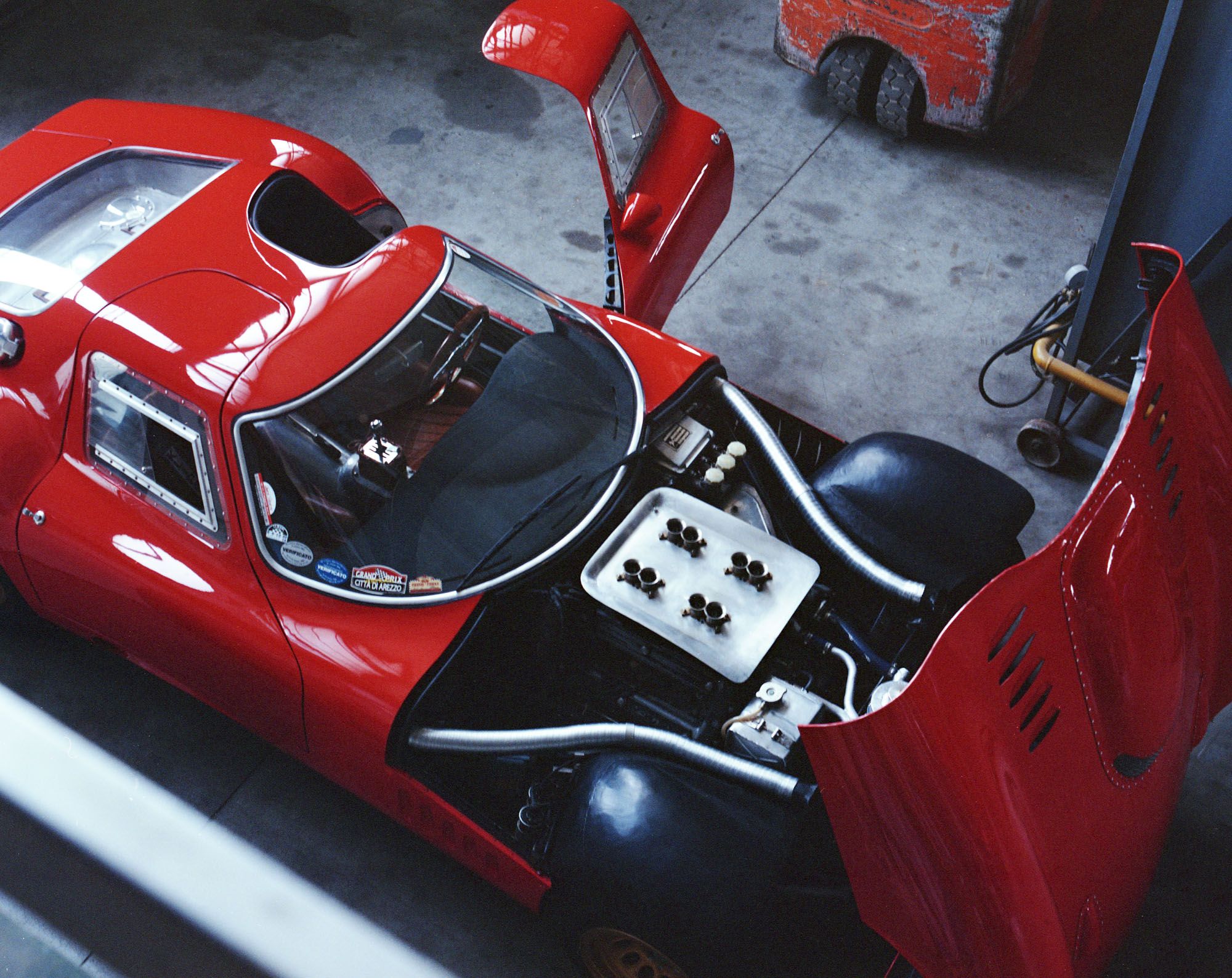

Carlo Chiti

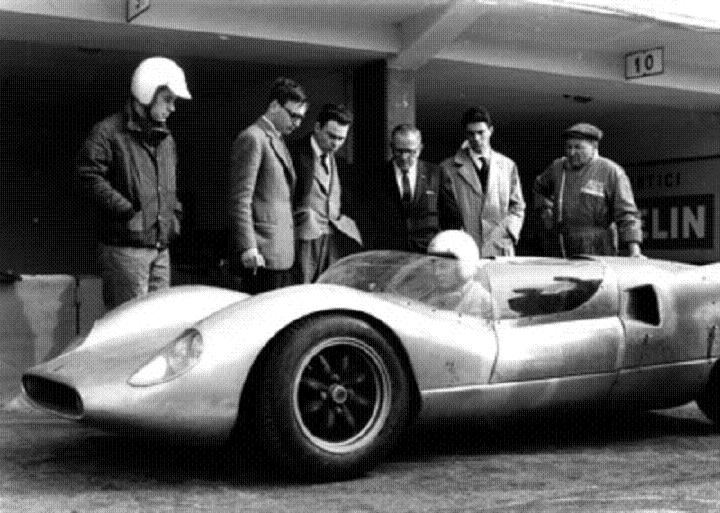

Carlo Chiti (19 December 1924 – 7 July 1994) was one of the great post-war Italian racing car and engine designers, best known for his long association with Alfa Romeo's racing department. He was one of the most important names in Italian automobile racing, revolutionary engine designer and aerodynamic he has made the history of motorsport and not only that over the sixties and seventies. Known for his genius, for his charge of sympathy, for his humanity and also for his size which was close to 2 meters and above and beyond 100 kilos, he was at Ferrari only four years but contributed to technical revolution. A humorous person, “toscanaccio” (from Tuscany) deep down inside, always quick-witted with a joke, Chiti was born in Pistoia and graduated with a degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Pisa in 1953. He joined Alfa Romeo in 1952 and designed the Alfa Romeo 3000 CM sports car. When Alfa Romeo's competition department was closed down in the late 1950s, Chiti was invited to join Scuderia Ferrari. At Ferrari Chiti was involved, together with Vittorio Jano, with the design of the 1958 championship winning 246 F1 and the 156 Sharknose, with which Phil Hill won the 1961 championship.

During his stay at Maranello, his continual desire to experiment found fertile ground; the racing department took care of everything, from F1 to touring cars and Carlo left an indelible mark in Ferrari technology. “Chiti was an innovator genius”, these are the words of Romolo Tavoni, then Ferrari personal secretary and sporting director, “he had two qualities: great humanity and great integrity but, like all geniuses, he was extremely disordered, having 50 ideas per minute and not always being able to realize all of them.” In those years Ferrari was coming out of a technical stalemate, it had to fight against the English “garagistes” who however were conquering world victories with their light rear-engined single-seaters. In prototypes the battle was against the Aston Martins and Jaguars and with touring cars you had to win to sell cars. He remained at Ferrari until he was kicked out, together with seven more executives who rebelled against excesses of lady Laura, Drake’s wife, to whom was entrusted the task of following the team on race tracks, paying particular attention to the costs control. And, in fact, a substantial part of the engineer Chiti’s wages consisted of food supplies. Fruit and vegetable, in particular.

The great innovations which Chiti introduced in Ferrari technology were initially independent back suspensions mounted on the Testarossa and on the F.1 246, the one that won the world championship with Hawthorn. In the 1958 Italian F.1 Grand Prix make their debut, always on the 246, disk brakes already introduced by Dunlop on English cars such as the D-Type Jaguar. Chiti was also a big expert in aerodynamics and made a number of studies on single-seaters and sport cars profiles to improve the penetration and the road holding. On the 256 Sport he introduced spoilers (he called them “iposostentatori”) to increase aerodynamic charge and Richie Ghinter, then engaged with these cars, after testing the new solutions promoted in full Chiti’s ideas. Thanks to the encounter with Mauro Forghieri he will give life to the first great project of his career, his masterpiece at Ferrari: the 156 F1, called “Shark Nose” for that famous nose shaped like a shark, which was fitted with a 1.5-liter V6 engine and was characterised by an important innovation, it’s the first rear-engined Ferrari in the history. But the road of the 156 wasn’t easy: Chiti in fact had to overcome opposition of Enzo Ferrari, according to whom “the oxen must be in front of the cart”. Thanks to the tubular chassis, the lower engine position, the new V of 120° design of it and the more forward-positioned gear box this car, characterized by two giant holes in the front, will say that Chiti won’t just be a great engine engineer but even an excellent aerodynamic.

Here’s how Giancarlo Baghetti, the first to lead it to victory, described it: “I found myself sat, actually half sprawled, on the track itself. You were driving with your arms outstreched and the steering wheel was smaller diameter and lighter in comparison with that of the front-engined 3 liters. The car was much more nervous of everything I had been driving until then and the compact 1500 cubic centimetres 6V cylinders engine was even more so: it shot out all its 185 HP quite suddenly, close to the top speed of 9,200 rpm. I was instantly aware that the sharp and nervous car’s set up required close attention in the gear changes, at each of which the car tended to sway on the track. The gear lever had sharp and hard insertions and caused us blisters and callosities on hands anyway. The steering wheel required no particular efforts but had violent reactions and it was needed to control it gripping it strongly: it was difficult because it had a thin rim, so that Phil Hill and me remedied getting the handle bigger with a garden hose suitably cut. In the cockpit it was of course hotter than hell as radiators were in front and water and oil pipes ran alongside the chassis.

Head and shoulders however were buffeted by the wind of the race quite freely: if then you straighten the bust for a moment to stretch yourself you were risking the strangulation, because the helmet was literally torn upwards. Furthermore the protective roll-bar was fake, it would have bent over at the first impact and, on the other hand, safety belts were not used: the only hope in case of overturning was to be thrown out before. The 120° 156 was modified in many particulars. It was a better-balanced car, with a lower centre of gravity. On such a fast track like Monza there were aerodynamic problems. On the straight you felt the steering wheel lightening itself or suddenly hardening itself depending on the longitudinal trim of the car on jolts.” The single-seater won the Drivers’ and the Constructors’ World Championship title but the party was tainted by the tragedy of Monza, in which lost his life his teammate Von Trips who, at parabolica, came out of the barriers of protection, punctured the nets and killed 13 spectators. Despite this though Chiti and Forghieri will win, bringing to an end their great innovation and the Tuscan engineer will be also considered for his great skills in aerodynamics.

In fact will be his the paternity of the first spoiler mounted on a race car, the 246 SP; for all the mechanics and technicians however the order was clear, that fin had another purpose: “it is for avoiding that the fuel spatters, while refuelling, end up on the exhaust pipes of the car triggering a fire.” That’s how Chiti’s astuteness made possible to hide the real usefulness of an appendix that later will be crucial. In addition to results in F1 Chiti will provide Ferrari with three sport prototype world championships, in 1958, 1960 and 1961. The history of scuderia Ferrari of those years is blessed with success and desire to do and it’s not only wins, rankings, powers, engines, chassis and bodies but also an interweaving of characters, human lives, dramas and revenges which make become that time full of meanings. Carlo Chiti, then technical director, worked with people like Luigi Bazzi, Romolo Tavoni, Vittorio Jano (who was still a consultant for Enzo Ferrari), then there were young technicians like Giotto Bizzarrini, who developed the 250 SWB and the 250 GTO and very young engineers Giampaolo Dallara and Mauro Forghieri were also growing. And finally drivers of the Scuderia, the knights of risk, wealthy, unattainable, hard and romantic, ready for everything and many died “in battle”: Peter Collins, Luigi Musso, Mike Hawthorn, Wolfgang Von Trips, Alfonso De Portago, Willy Mairesse, Tony Brooks, Jean Berha, Dan Gurney, Richie Ghinter, Olivier Gendebien, Phil Hill. Chiti’s corpulent figure was due to food, he ate very much and was known for his dinners at the restaurant in company: he sat maybe at nine in the evening and rose from the table at two in the morning, without ceasing to eat.

As a good “toscanaccio” he was decisive and argumentative. Strong character, when he was right it was difficult to oppose him, but his nature was that of a good father. “He hated violence in any form” they’re again Romolo Tavoni’s words “he often wondered why a person on the street ended up living like a tramp or a thief. He loved animals, stray dogs and cats often took refuge with him. He didn’t tolerate abuses and was expelled from Ferrari together with us just in the spirit of solidarity, because he had also supported our protest without having been party to the dispute of the issues had with Mrs Laura.” When executives were thrown out, Enzo Ferrari dedicated to them a popular and lapidary phrase: “time has taken charge of defining the individual skills of all of these people.” In the case of engineer Chiti however time has been a gentleman: ATS, Autodelta, Motori Moderni, world sportscar championships won and the return of Alfa Romeo to big competitions, a sport career with results that have defined the great value of “Chitone” (big Chiti) as he was often called for his figure! In 1962 Chiti walked out to join the breakaway ATS F1 team formed by a number of disaffected ex-Ferrari personnel. The ATS project was not successful and did not last long and in 1963 Chiti re-entered competitive motor racing through a new project, Autodelta, which enabled him to rekindle his association with Alfa Romeo, for whom he designed a V8 and then a flat-12 engine for their Tipo 33 sportscars. These were eventually successful, winning the 1975 World Championship for Makes and 1977 World Championship for Sports Cars.

The Autodelta was everything to "Chitone": a highly qualified workshop, a sort of a second home, a place of entertainment. Chiti was a great lover and protector of animals. He collected sick dogs everywhere, cured and took them to Autodelta where they often just sat in adoration of the owner on the desk, on the chairs, on the armchairs of his office. “Have a seat – Chiti told his guests – ma un mi tocchi la c'anina (but don’t touch the dog)". Another time he kept a couple of journalists who listened a lively discussion in his office waiting outside the closed door. Then, suddenly, a gunshot rumbled. The two reporters opened the door and found Chiti and his interlocutor who, laughing, were looking at the hole in the ceiling. It was like that the Great Chiti, he took everything in joy. At this time, Carlo became involved in F1 again through the Brabham team (Bernie Ecclestone was one of his greatest friends and admirers) that signed an agreement with Alfa Romeo to use Chiti's engines.

The result was the BT46, the “fan car”, as it mounted a showy fan behind the rear wing. There was some success, the car was surprising, especially for its being capable of sucking the air. Niki Lauda won two races in a Brabham BT46 with the Alfa engine in the 1978 F1 season. Brabham designer Gordon Murray persuaded Chiti to produce a V12 engine to allow ground effect to be exploited by the team. But the solution was considered irregular and the single-seater was excluded by the world championship. Curious will be the story of Lauda’s master mechanic about what the British designer had told him: «before the qualifyings Gordon Murray comes to me and asks to take on board a full tank of gas and “wooden” tires. Did I get wrong? I ask him to repeat. ”I want a full tank of gas. We are too strong. We have to bluff, to go slower, otherwise they’ll disqualify us”. Said and done. With 210 litres of gasoline we are second and third on the grid. […] In the race no contest: Lauda wins big.»

However, during the 1979 F1 season, Brabham's owner Bernie Ecclestone announced that the team would switch to Ford for the next season, prompting Chiti to seek permission from Alfa Romeo to start developing a F1 car on their behalf. The partnership with Brabham finished before the end of the season. The Alfa F1 project started with some promise but was never truly successful. The team achieved two pole positions. Tragedy also occurred when Patrick Depailler was killed, testing for the 1980 German GP at the Hockenheimring. The team's best season was 1983, when Chiti designed a turbocharged 890T V8 engine and Alfa Romeo achieved 6th place in the constructors' championship, largely thanks to two second-place finishes for Andrea de Cesaris. In 1984 Chiti left Alfa Romeo to set up another company, Motori Moderni, which concentrated on producing engines for F1. Initially the company produced a V6 turbo design, used briefly by the small Italian Minardi team. When the banning of turbos from F1 was announced, Chiti designed a new 3.5 litre atmospheric flat-12 engine. This was eventually taken up by Subaru, who badged it for use in their brief and completely unsuccessful entry into F1 with the tiny Coloni team in the 1990 season.

Chiti continued to work until the last minute. Tireless, passionate, he could have never done without his work, his engines. "When you come to Milan – he used to say by phone – let me know, si va a desinare insieme... (let’s get dinner)". He loved good tables in happiness. He was maybe the first to carry with him his own foods on circuits, disgusted by the brutality of hot dogs that then, together with bananas, were the only edible products of F1. And it was in these circumstances that he opened very willingly the books of his encyclopedic memory to tell a life in races. Anecdotes about everything and everyone, episodes still today officially unknown of this or that race, teasings, resentments, loves, hates. Human stories of mechanics, vip, drivers, women, adventurers. Technical stories of real and fake inventions, of little scams, of subterfuges, of big achievements. Our beloved "Chitone", the last gentleman officer of this world of motor sports more and more frowny, devoid of sense of humour as much as it’s full of money, died in 1994 in Milan leaving us when he was 70, after having signed several successful projects including the Ferrari 250 GTO, the 8 million euro car.

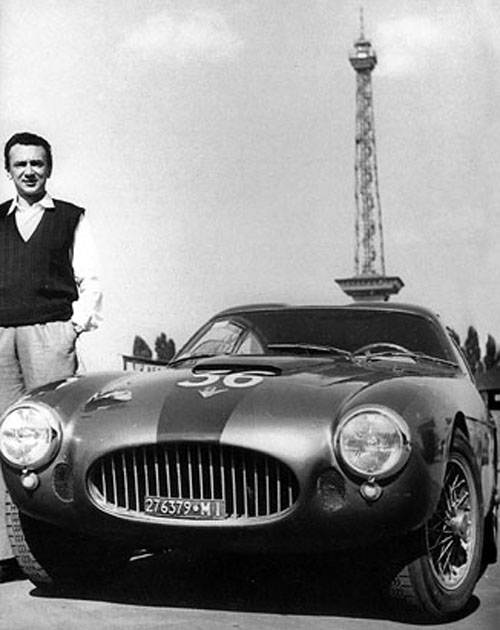

Elio Zagato

Ugo Zagato (25 June 1890 Gavello –31 October 1968 Rho) was an Italian automobile designer, known for establishing and running the Zagato coachbuilder, famous for its lightweight designs. He had five brothers and lost his father (1905), forcing him to emigrate to Germany and metalworks employment in Köln (1905). He returned to serve in the military (1909) and joined car coachbuilder Carrozzeria Varesina in Varese, while studying at the Santa Maria design school. During World War I he moved to Torino and joined the Pomilio aircraft manufacturer, learning lightweight bodycrafting (1915–1919). To build aircraft-inspired bodywork for sports cars that focused on lightness and good aerodynamics he established Carrozzeria Ugo Zagato & Co., a workshop in Milano (1919), where he built close ties with Alfa Romeo. His workshop was destroyed and rebuilt as La Zagato outside Milano after World War II, joined by his sons Elio Zagato (27 February 1921 – 14 September 2009) in 1946, and Gianni Zagato (born 1929). The two brothers, upon the father's death in 1968, took over its management. Elio Zagato embodied the Dolce Vita spirit as a GT driver and designer. He was one of the founders of Scuderia Ambrosiana of Milan. Races he won include Targa Florio and five GT series, as well as Coppa Inter-Europa, the Dolomites Gold Cup Race and the Berlin Avus Cup in 1955. He was one of the leading figures of Italian Gran Turismo (GT) racing and car-body design. In the 1950s, driving a Zagato-bodied Fiat 8V, Elio emerged as the consummate gentleman racer in Italian GT championship events.

Zagato, his father's firm, provided the lithe, lightweight aluminium bodies for many of the Lancias, Alfa Romeos, Abarths and Maseratis that dominated these meetings. Elio won 82 races out of the 150 he entered and won four of the five championships he entered. When his racing career ended after a bad road accident, he took on an increasingly important role in the family business. He had trained as an accountant and confessed later that he initially had little interest in cars. Yet, after competing in his first event in 1947 in a Zagato-bodied Fiat 1100 Spider his father had given him as a graduation present, his future was decided. The 50s and early 60s were the most industrious years for Zagato; labour was relatively cheap and Italian design was at the spearhead of automotive creativity. Elio, alongside his younger brother, Gianni, made Zagato a much less craft-based enterprise as he took over the running of the factory from his ailing father. Machine-pressed alloy body panels began to take the place of one-off pieces, though Zagato would never catch up with its bigger rivals in terms of mass-produced bodywork. Working with the chief stylist Ercole Spada, Zagato produced some of the most beautiful GT designs of the era; spare and muscular cars such as the Aston Martin DB4 GTZ, the Alfa Romeo Junior TZ and SZ and the Lancia Flaminia Sport. These were minimalist shapes bereft of superfluous trim that introduced phrases such as "double bubble" roof to the car body design language: twin shallow domes, devised by Elio, to give extra head room and strengthen the roof. For lightness, Zagato pioneered the use of Perspex and of aerodynamics, with trademark forms such as the split or stub tail. Indeed, Elio would take prototypes out on the autostrada covered in wool tufts in order to test air flow over the body.

Apart from a few show cars, makers such as Ferrari, Maserati and Lamborghini feature little in the Zagato story but Lancia proved more fruitful and the Fulvia Sport, a bullish coupé, was the firm's most successful design in terms of numbers built – 7,102 cars. After Ugo's death and the loss of Spada later that year to Ghia, a rival styling house, Zagato appeared to lose direction. With a capacity to build 3.000 cars a year, it was left particularly exposed when the fuel crisis hit in 1973 and buyers began turning to a cheaper breed of mass-produced GT car such as the Ford Capri. By the mid-70s, Zagato was producing armour-plated Alfa Romeos for the Italian government and, by the early 80s, it maintained a presence at motor shows with one-offs. The firm built a station wagon based on the Lancia Thema for Fiat boss Gianni Agnelli, which he kept at his St Moritz home. An order for 25 Maserati Biturbo Spiders a week kept the firm afloat in the late 80s but labour costs were rising and profits were hard to come by. In 1984, with the value of classic Zagato cars such as the Aston DB4 GTZ spiralling upwards, Aston Martin and Zagato felt compelled to revisit their relationship and created an instant collector's item, the Aston Martin V8 Zagato. So fragile were Zagato's finances that Aston boss Victor Gauntlett took a 50% stake in the firm just to get the promised 50 cars to their owners. Gauntlett later sold his stake to Nissan but plans for a retro double-bubble car, the Stelvio, were thwarted by the Japanese stockmarket crash of 1990. Elio and Gianni Zagato, subsequently, bought back their independence as a deal with Alfa Romeo took shape to build a V6 coupé called SZ ES30.

This was hugely over-subscribed and represented Zagato's last hurrah as a volume producer. Its success should have been followed up by the Lancia Hyena but the project stalled when Lancia refused to supply parts. In 1993 Elio and Gianni retired, having laid off 120 workers. Since then Zagato has been a design house building prototypes. Recent work includes one-off Ferrari and Maserati cars for private clients and the Milan Euro Tram. In retirement Elio, a down-to-earth but rather shy man, would cheerfully submit to interviews but was more interested in reminiscing about his motorsport glory than his designs. Elio married Laura in 1954; they were later divorced. His son Andrea is as of 2009 in charge of the family business, jointly with his wife Marella Rivolta-Zagato, daughter to Piero Rivolta of the carmaker Iso Automoveicoli S.p.A.. Elio Zagato’s autobiography “Storie di corse e non solo” was published in 2002.

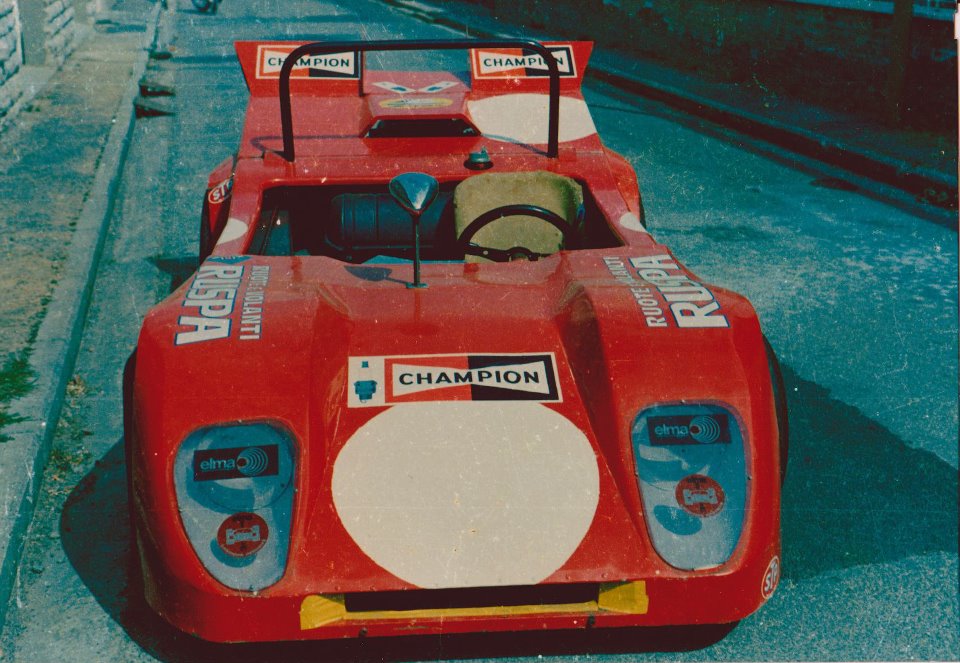

Enzo Osella

Vincenzo "Enzo" Osella is the son of a garage owner from Volpiano, a small town near Turin - Italy. Osella is a racing car manufacturer and former F1 team. They participated in 132 GP between 1980 and 1990, achieving two points finishes and scored 5 championship points. Named after its founder Vincenzo Osella, the team began life by racing Abarth sports cars in local and national races in Italy in the mid-1960s. Enzo joined Carlo Abarth's company to also help prepare engines for the firm's competition activities, notably in touring car racing. In 1965 Osella left Abarth and moved to his own premises and began work on building his first prototype chassis.

This proved to be quite successful in races and hillclimb events in Italy and, when Abarth sold his business to Fiat in 1971, Osella took over the Abarth racing department and, working with Antonio Tomaini, produced the Abarth-Osella SE021 which won the European 2 Litre Sportscar Championship in 1972. This was followed by the first Osella, known as the PA1, but this was not a success and it was not until the end of the year that the heavily-modified car was competitive. This was followed by the PA2, with bodywork designed by Pininfarina. Osella and Tomaini wanted to make an impression in single-seater racing and soon began building cars for Formula 2, the first being run in 1974 for Giorgio Francia. The chassis was developed the following year and driven by Francia and Diulio Truffo. Francia scored one fourth place in the 1975 European Championship. Osella then produced a Formula 3 car (the FA3) but it was not very competitive and the company's main income remained from sportscar racing.

An engine deal with BMW improved performance and, in 1976, Osella won the Targa Florio with drivers "Amphicar" and Armando Floridia. The following year Francia, Lella Lombardi and "Pal Joey" (Gianfranco Palazzoli - who later become Osella team manager) gave Osella second place in the World Sportscar Championship. In 1979 Osella's new designer Giorgio Stirano - Tomaini having gone to Ferrari - reworked the FA2 and Osella returned to F2 with sponsorship from Beta tools and a young driver called Eddie Cheever. In 1979 the American won three races and finished fourth in the European F2 Championship. Osella's ambition was F1 and in 1980, with backing from Denim and the state tobacco company MS, Osella built the FA1/A. Palazzoli managed the team with Cheever drove.

The car was not a great success and the FA1/B appeared before the end of the season, the original car having been reworked by Osella and Giorio Valentini. In the years that followed Osella was a regular on the F1 scene with backing from Denim and later Kelemata and ultimately Fondmetal. Results were few and far between and on there were major setbacks along the way, notably the death in Canada in 1982 of youngster Riccardo Paletti. In 1983 the team hired Tony Southgate to design the FA1E and used old Alfa Romeo V12 engines. The link with Alfa Romeo continued in 1984 with one of the company's 1983 cars being given to Osella. It was modified and raced by Jean-Pierre Jarier but it was destroyed soon afterwards in a huge accident at Kyalami. Against the bigger factory-backed teams Osella struggled to survive the turbo era. By the end of 1988 the team was faced with a problem.

It could no longer modifiy the old cars and use Alfa Romeo engines because of the change in the F1 regulations. New investment was needed. Osella offered shares in the team to Fondmetal wheel magnate Gabriele Rumi. Tomaini returned from Ferrari and designed a new DFV-engined FA1M which showed well on occasion in the hands of Nicola Larini but the cars were not reliable and the lack of results meant that the team had to pre-qualify in 1990. It was the beginning of the end. Pre-qualifying was so competitive that often cars which escaped from the session scored points in the races. Osella struggled and at the end of 1990 Enzo was forced out of his own team.

It was transformed into the Fondmetal F1 team and moved to new premises at Palosco. Enzo Osella overcame the setbacks and went back into the sportscars business, building a new PA16 chassis for the Italian national racing scene. This was developed into the PA18 and then the PA20 and success enabled the team to moved into a new factory at Atella. This featured its own windtunnel. The grounds around the old factory at Volpiano were transformed into a short test track and, by 1995, Osella was completely dominant in Italian hillclimbing with driver Pasquale Irlando. That success continues today.

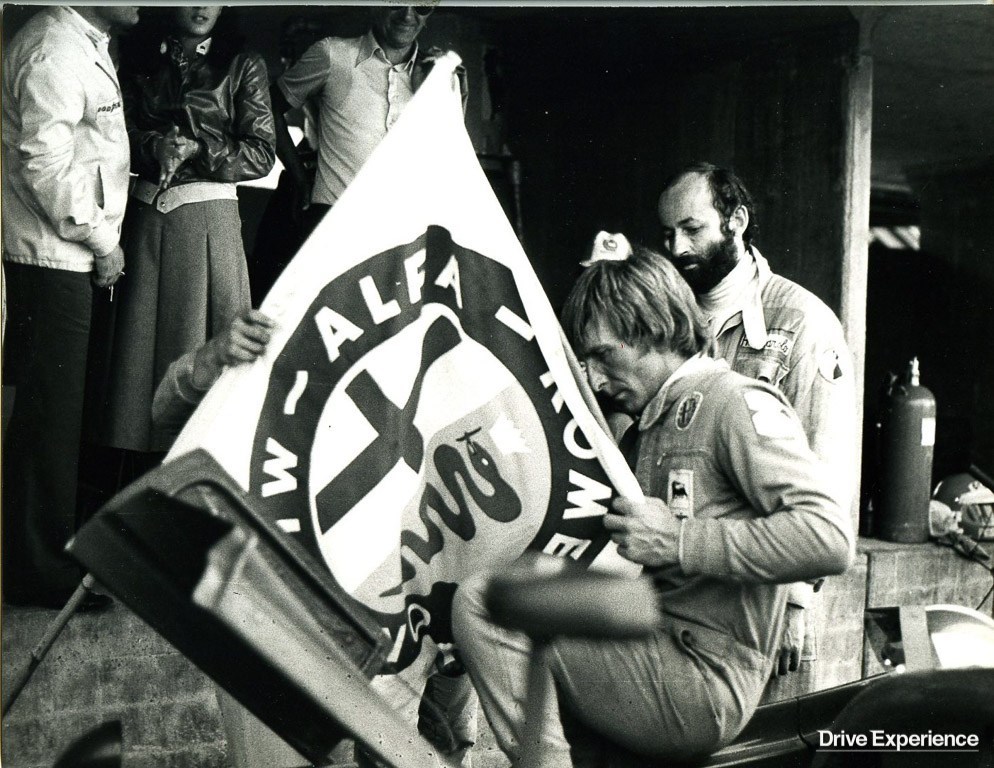

Gian Luigi Picchi

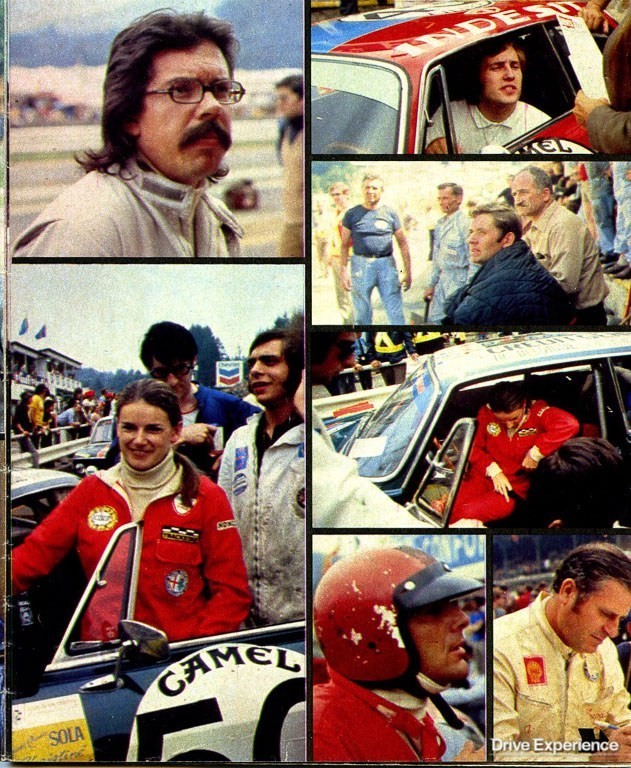

Gian Luigi Picchi (born in Tivoli on 28 October 1946) arrives young into the world of motor sport, coming from karts. Already acknowledged as a special talent (he’s Italian team national champion with Arcionia Karting in 1963 and European team champion with the national team in 1965), he makes his first appearance in the minor categories of single-seaters (K250 Tecno) becoming Italian vice champion in 1966 to move to F850, where he makes his debut with the Lucky-Genovese in 1967 immediately winning two races. In 1968 he’s official driver for the De Sanctis F850 and becomes Italian champion of the speciality winning four races (he’s the first driver coming from kart to win a car championship in Italy). In 1968 he starts racing in Formula 3 and in 1969 becomes the Italian champion as the Tecno official driver. Towards the end of the 1969 season he was invited by the Alfa Romeo Autodelta works team to a selection of drivers, where he appears to be the fastest of the 25 called.

The start of the 1970 season sees him still winning two F3 races but he’s then hired as the official driver of Autodelta for the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) where, during the season, he wins two races (Nürburgring and Zandvoort) and becomes vice-European-champion in division 2. For the 1971 season the CSAI entrusts him with the Formula 2 car as an emerging driver but, after only four races studded with mechanical failures, Picchi leaves the championship. Always in 1971 Autodelta assigns to Picchi the GTA Junior 1300 with which he wins the European Touring Car Championship, winning six of the nine races run (Monza, Salzburgring, Brno, Zandvoort, Paul Ricard, Jarama). In 1972 he still wins three races of the ETCC and thus contributes in a decisive way to the conquest of the European Marques Championship for Alfa Romeo.

In this year he participates in the tests of Alfa Romeo 33/3000TT and is inserted as official driver for the World Brands Championship but, for the protest of Alfa Romeo against the regulation adopted, Autodelta abandons the 1973 season. That same year, when the first of his three sons is born, Picchi decides to abandon the activity of professional driver and retires from the competitions. In 1988 he was called to compete in classic races, where he wins twice with the Alfa Romeo 2600 and the Ferrari 250 GTO. In 1990 he participates in the Italian Touring Car N2 Championship with the Vaccari Motori, where he wins at Magione and was leading the championship till the accident at Imola, which deprives him of the car. In 2004 he participates with Maurizio Flammini in the Superstars series, where he wins at Mugello in the opening race in the BMW M5 of Vaccari Motori.

During his racing career he participates in three years in 115 races, winning 44 of them. Despite the apparent fame, the story of Gian Luigi Picchi, miracle driver of Italian motoring, remained a kind of mystery. In the context the car had already lost its value as economic status and had become the disengagement and the adventure, the way of living a fascinating sport and, to all appearances, less elitist than in the past. When, near the end of the 60’s, the very young driver from Tivoli presented his credentials as a new driver chosen by Alfa Romeo for the commitment in ETCC races, Picchi was already a rising star of the national Motorsport.

He was the first driver who had been formed in the karting world and who, arrived then to the competitive spirit of minor formulas, won every national title including the Italian F3 Championship. Reading today the flatteries of the specialised press of the day which turned on spotlights on his dazzling success, it seemed like Picchi’s career turned to the big formula but were the headquarters of Autodelta and Carlo Chiti himself, whose fascination it was not easy to resist, to dictate the future of the driver. Touring races of the seventies became legendary precisely for their charm, born from the unrepeteable mix of difficulty of circuits at the time and of cars apparently similar to ours used on a daily basis.

The leading European automobile manufacturers hired the best drivers of the formulas to compete in the legendary European ETCC Championship, consisting of a dozen races run on the tracks spread around all the Old Continent. Although tempted by F2, which would have been the natural progression for a driver of his talent, Picchi accepted the offer and the rest is chronicle of a continuous success, short lasting but of an unusual intensity. As a racer he has proved to be a rigorous and sober young man, down to earth. He had his own ideas about life, about racing and about people and expressed them with disarming lucidity. His intellectual depth and rational intelligence gave him a near-natural superiority position. He was calm till looking detached, not very expansive and with exceptional self-control.

He showed a curiosity and diversified interests, not just the passion to drive a racing car and his arguments appeared always fruit of reflection and well built and stood out into the world of touring car drivers, made by likeable individuals with their play-boy charm all smiles and pats on the back and always looking for that little bit of celebrity that the specialized press could offer to their exploits.

Among these passionates connoisseurs, often rich “gentleman drivers”, progress had cancelled forever the image of the driver with goggles, bow tie on the impeccable shirt and headscarf and now they all looked alike with their full-face helmets and dark visors but Gian Luigi Picchi, professional driver dedicated with his young age and his polite way of being present but not intrusive, was definitely out of tune in that colourful circus gathered around the tracks. You can remember a champion in many ways. You can reconstruct his races, because reliving them is not possible and try to decipher the technical-sporting aspect. But you can also try to understand his complex nature through something emotional, personal, through the daily adventure between rationality and passion without devoting yourself to one or the other only.

Thus, their story takes the form of virtual counterpoint of the documentary facts and our imaginary indissoluble from the role that the chronicle or even more the common belief have woven around them. Gian Luigi Picchi racer had opened all the doors that gave access to the throne room with an apparent disarming easiness but then, with a calm declaration without explanation, has announced the abandonment of the racing world, at the time when his driver career clearly indicated the ways with no obstacles. Thus he set the precedent, unique even in that incredible and weird universe which is motor racing. His decision seemed to be even more incomprehensible since in motor sport was already established a new profile of the professional driver grew up in the various categories, that in the competitiveness little or nothing left to chance or improvisation.

With the fast development of advanced mechanical means, a great change was prefigurated which favoured the exaltation of champions such as Picchi. Motor racing had changed but has preserved an ancient rituality which never saw changing the essence of Ludi and Munera Gladiatoria. They had remained faithful to the great kermesse of public, passion and supreme commitment. For Picchi, as for the other drivers, the race was lived as the archetype of danger intended as the extreme challenge where the stakes limit was driver’s life itself.

The audience asked its favorites the curiosity to open the forbidden door, to touch the limit going into the unknown. What could hurt irresistibly attracts. To spend yourself in an absolute act identifies victory with passion. Spectator and driver identify themselves in what is challenge to time, challenge to death and that’s where beauty originates. Victory is just the realization of an ancestral rite. The driver competes to show his superiority but also to win against himself moving higher the limit already reached, thus becoming a knight of the impossible, repeating his own rite of precision, often not empirically verifiable.

The race then asked the pilot to develop an intimate relationship with the track, it required determination, courage and impeccable analysis because only so it was possible to emerge from the saraband on the edge of extreme speed. At the end, in such a game, this was understandable because all the agonistic parenthesis resulted only a building of intuitions. When drivers were taking the start on the grid transformed themselves, in search of that extra wriggle which made them participants of a mythical party, protagonists of an authentic dream that has something magical. Subjected by emotional tension, own and also that of the crowd at the edge of the track, the driver acquired a strange sensation of superhuman power, he believed himself capable of accomplishing everything and subverting with his own ability even the most unfavorable situation.

If then this miracle did not happen, you didn’t care much, indeed paradoxically the link between driver and his own fan came out of it strengthened. To know how to absorb defeat, being sure that in the next race you could and should start all over again with humility and passion, exalted the myth of the hero and led him to touch the apogee. The truth is that, in every game, it’s always nice to win. It is this will to win that distinguishes the star driver and it requires adequate psychological preparation to run. You cannot win a race if you are not completely determined to win it. In such a special universe and governed by particular rules, some constants among those listed converged in a natural way in Gian Luigi Picchi’s driving. The analysis of his way of driving reveals the extreme precision and the extraordinary ability to keep the car in equilibrium in every situation, without evident effort.

There’s no memory, no photo of Picchi driving acrobatic or outside the laws of physics. His use of the track is rational and his car never appears unbalanced. Given the same evident confidence in himself during the race and almost superhuman reaction times, Picchi’s precision, compared to that of other drivers, derived from the perfect self-control and from the inner order that allowed him the maximum tranquillity, often demonstrated in extreme conditions. He was an extraordinary champion, not only for his ability to drive a race car but also thanks to his intellectual capacity and skill to expand the control of his reactions in every extreme situation. At that time it was hard to find such a driver.

He passed indifferently from open-wheels of a single-seater to closed bodies of cars which came from series production. A demonstration of this incredible sense he had remain the victories achieved in extreme conditions with the single-seaters, with the tourism cars and then, decades later, with the legendary Ferrari GTO in the sport category or with the very powerful BMW M5. However his brief parenthesis of professional driver is often identified with the presence among the elected of Autodelta, Alfa Romeo’s racing arm, around the time that the "Casa del Biscione” dictated the laws in ETCC championship. The name Alfa Romeo has always been synonymous with sports car, associated to the world of racing and his history indissolubly linked to the amazing victories.

At the beginning of 1970s, Alfa Romeo had the merit of having produced the magnificent GTA Junior, powerful car with unquestionable charm destined to dominate the Tourism category and Gian Luigi Picchi has certainly the merit of having brought it to the maximum triumph, giving it charism with aura of invincibility. Driving his GTA Junior “Muso Giallo” (yellow nose), he impressed you for his skill to turn always at the very limit without ever making driving mistakes, coming out punctually quicker than others. The precision with which he governed the car in racing derived from his driving experience with open wheels. He used brakes, engine and gearbox with respect for the vehicle and also the tires of his car were less deteriorated at the end of the race, while in the race he was tenacious but extremely loyal and sincere. His common sense and intelligence in driving have often determined the result of the race.

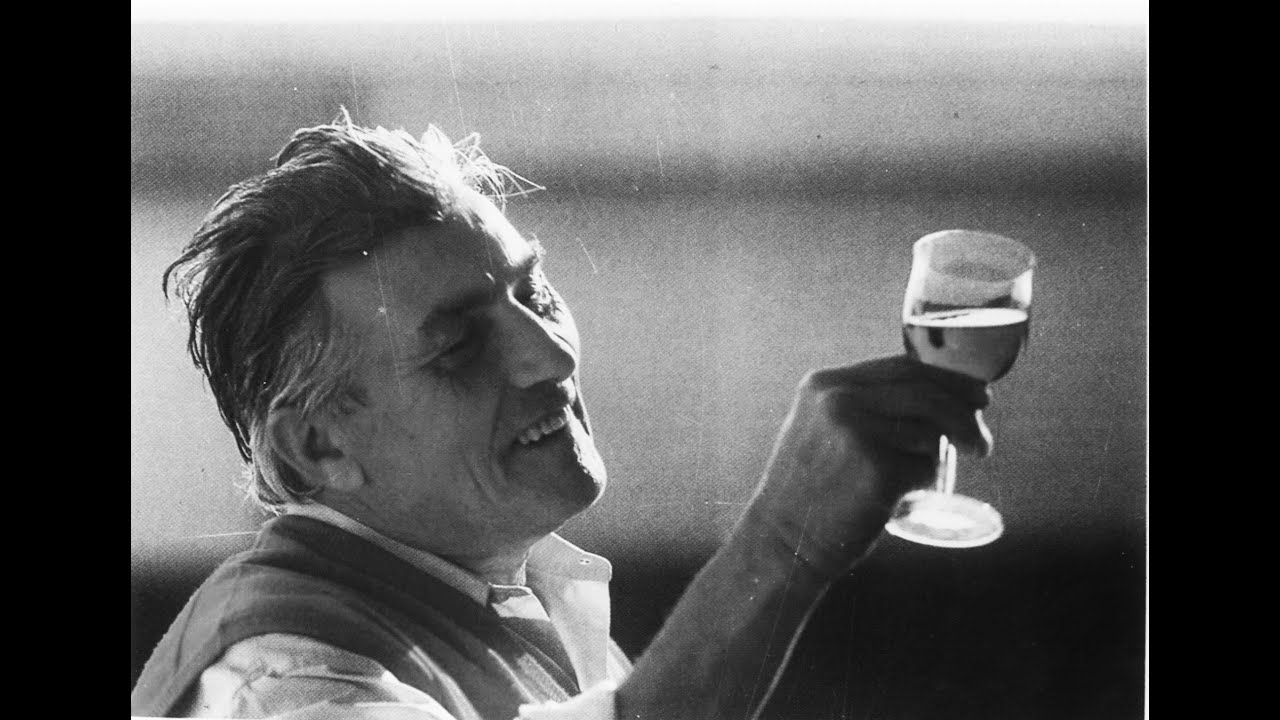

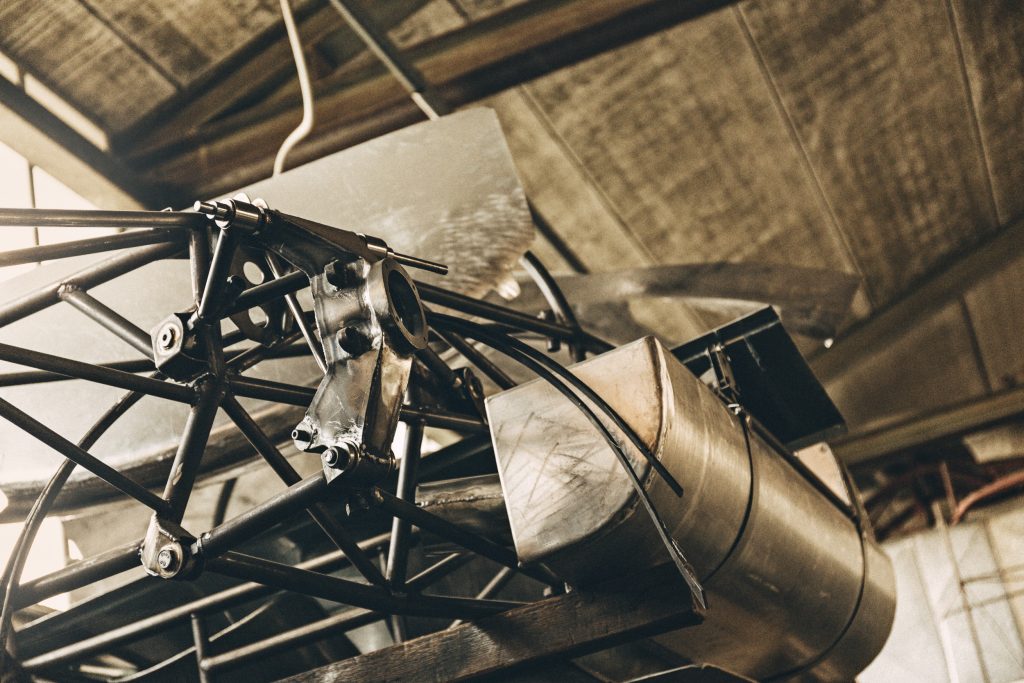

Gian Paolo Dallara

Gian Paolo Dallara (born 16 November 1936) is an Italian businessman and motorsports engineer. The owner of Dallara Motorsports, a company that develops racing cars, he graduated from Politecnico di Milano university at 23 years (first record in his career still unbeaten), majoring in aeronautical engineering.

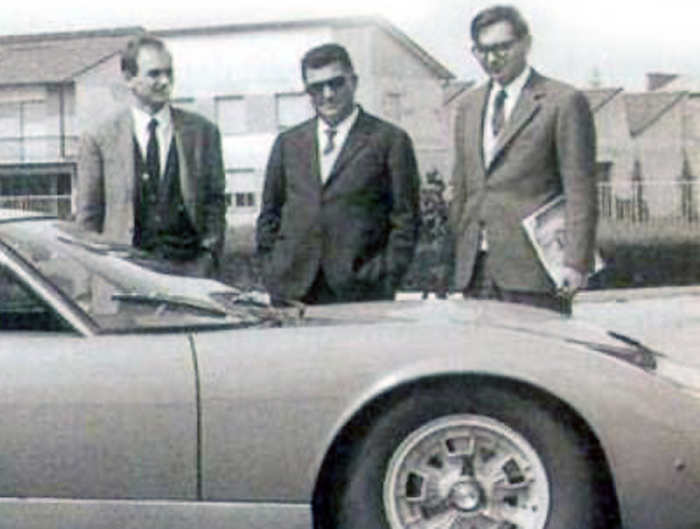

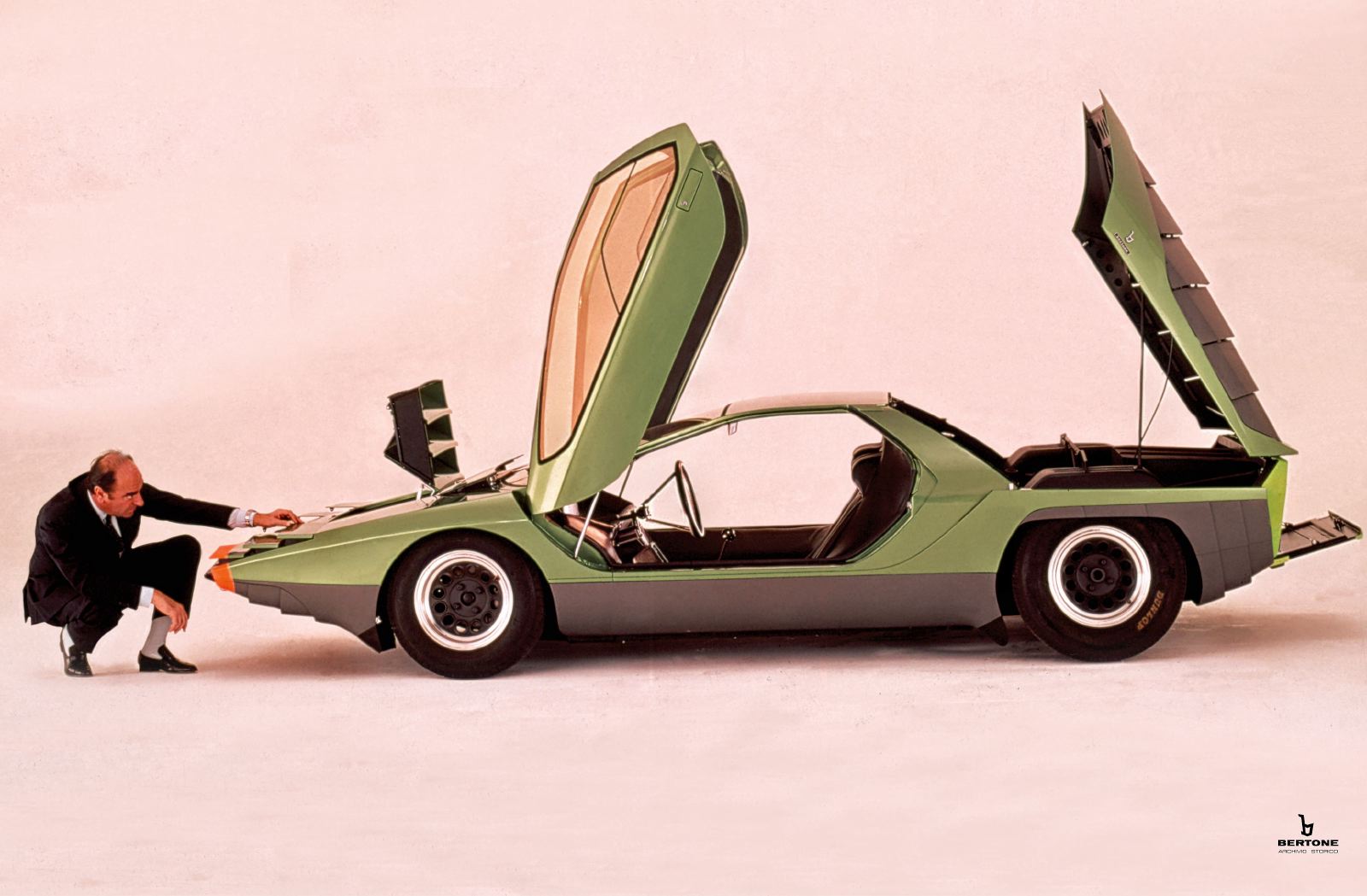

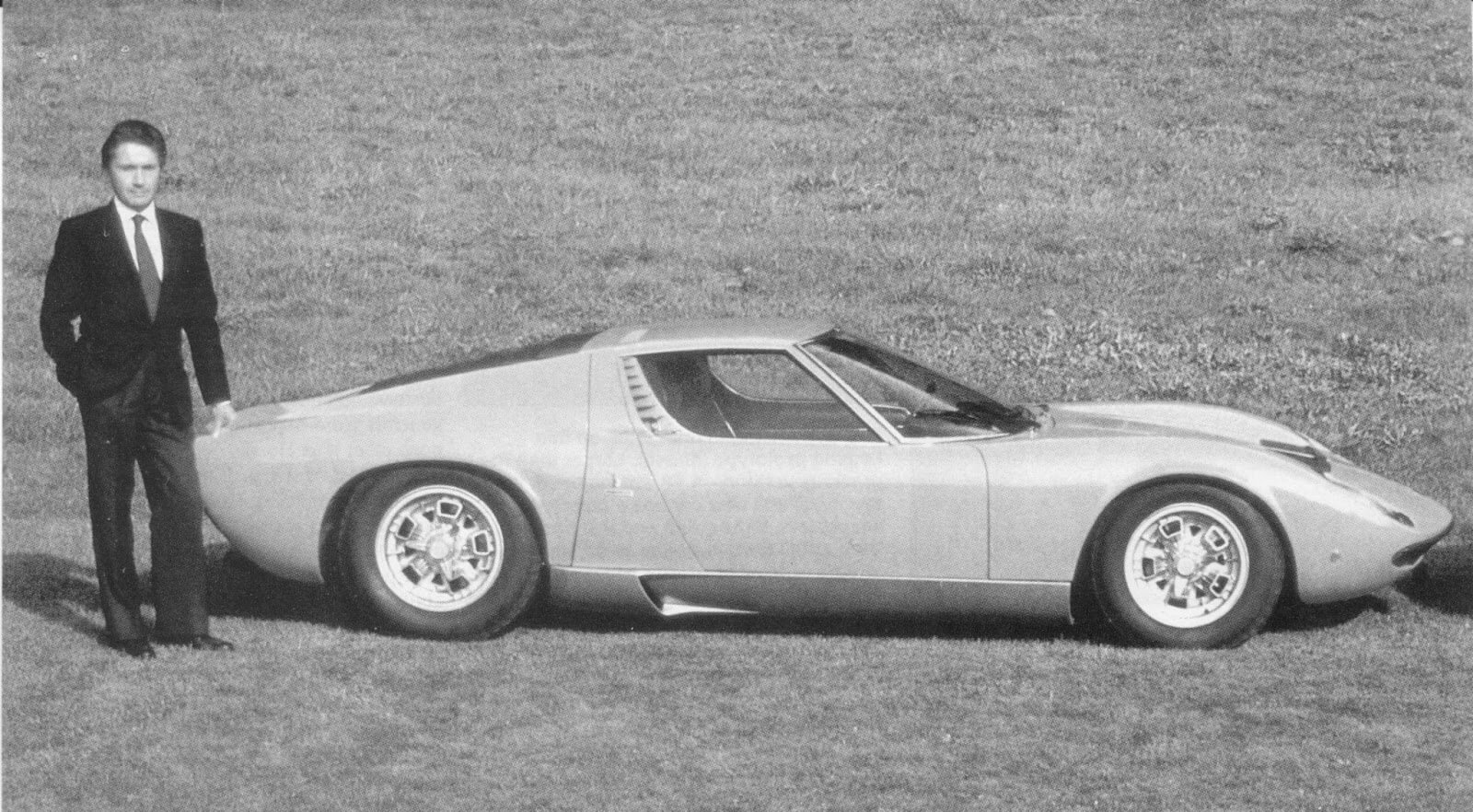

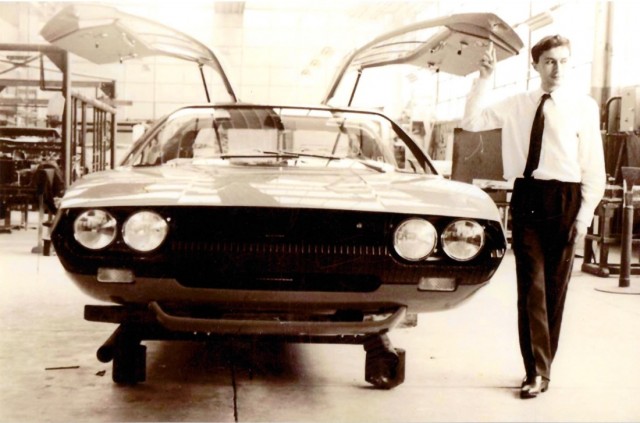

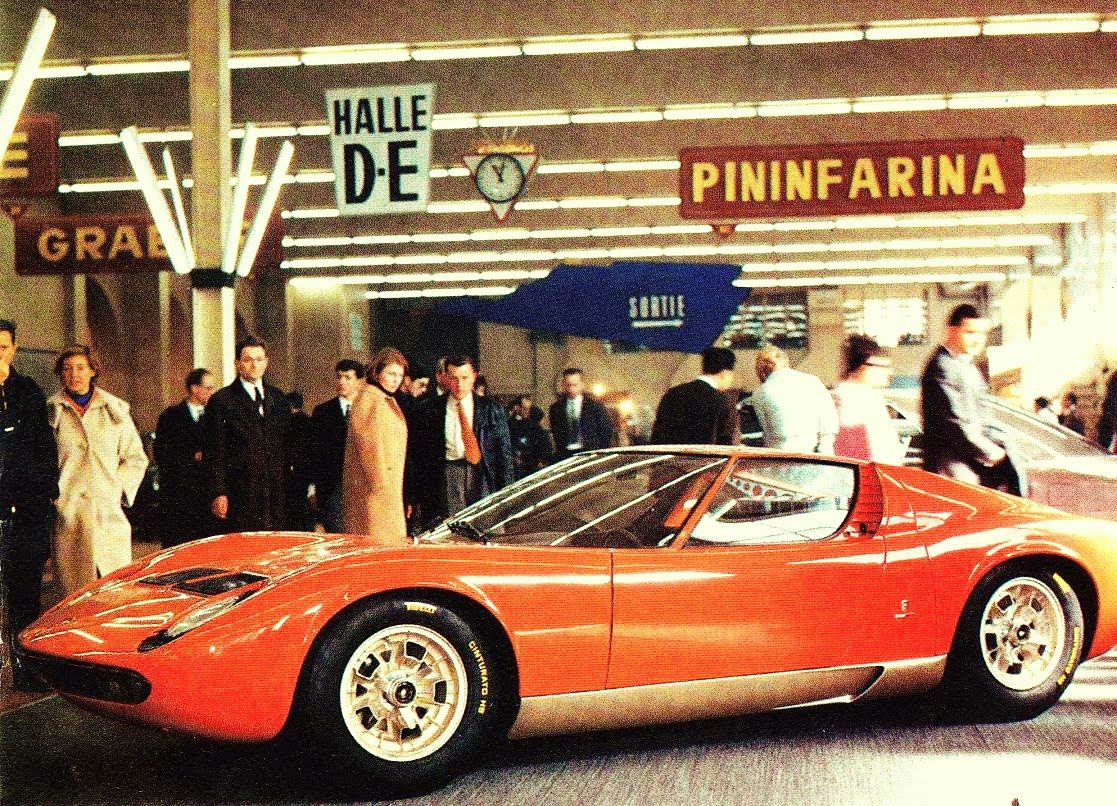

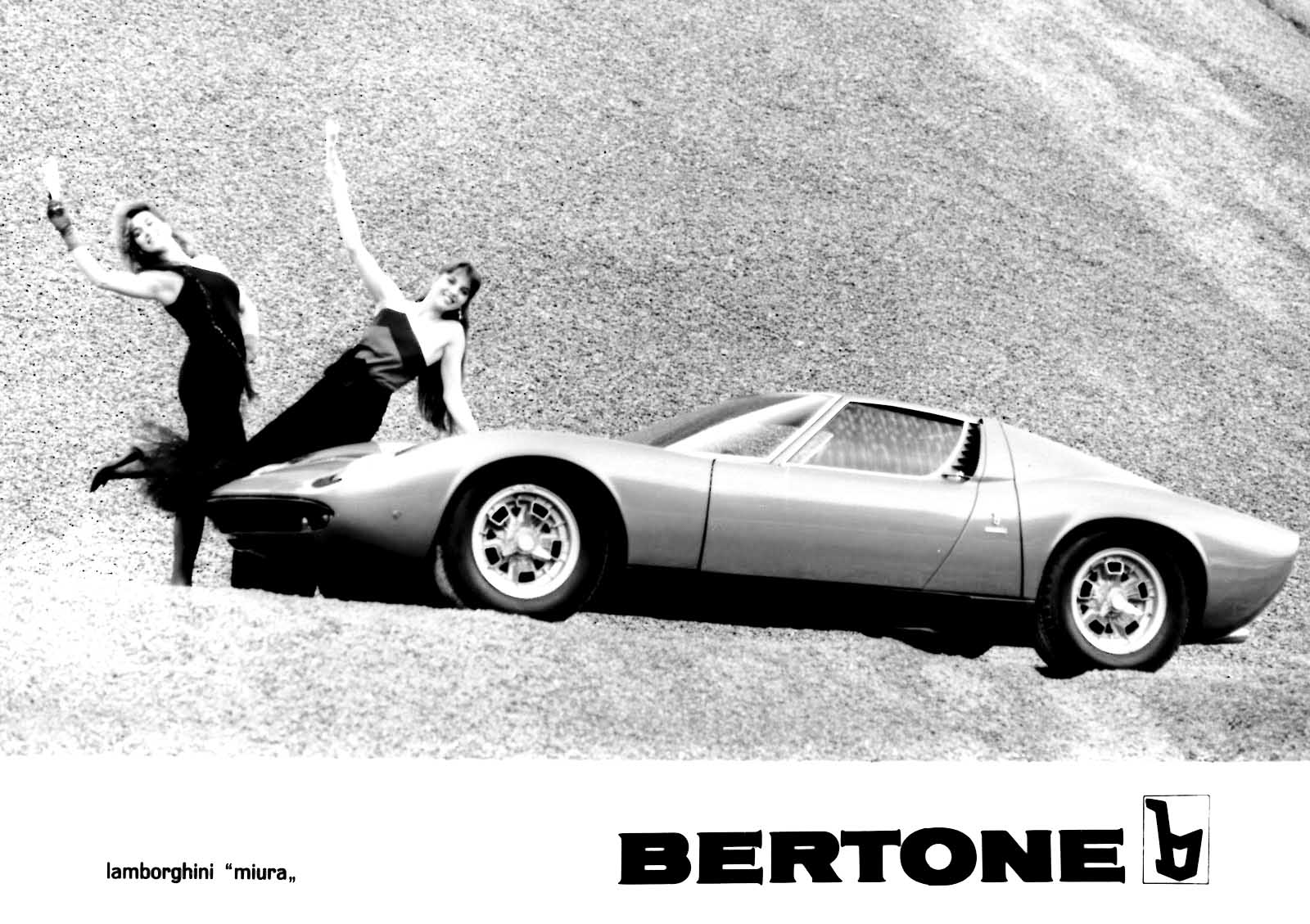

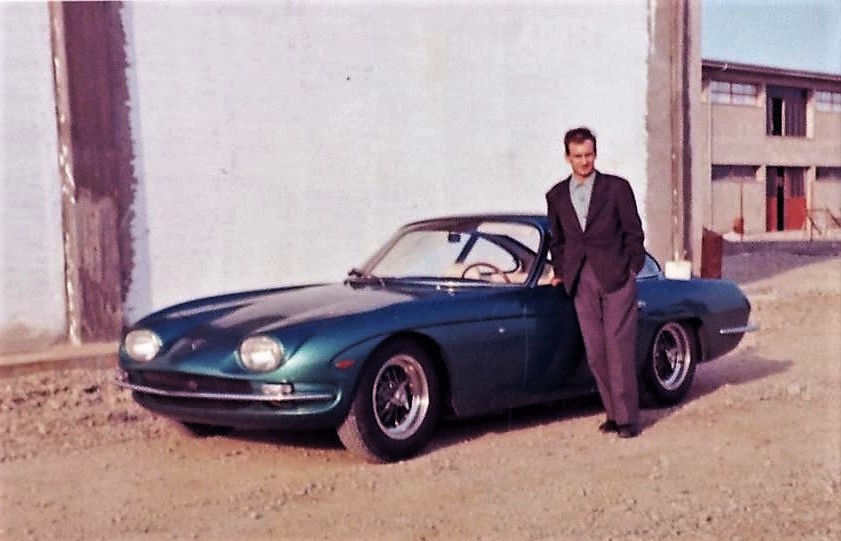

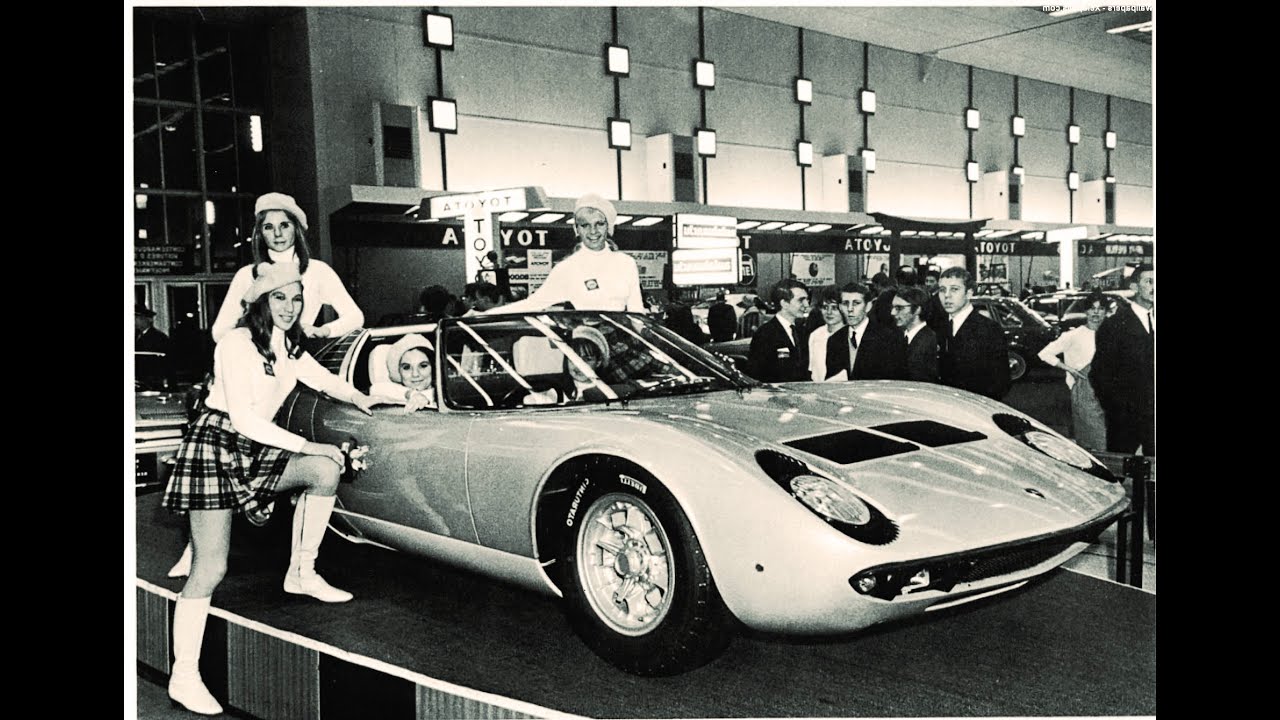

He joined Ferrari in 1960 to work on aerodynamics and build the first wind tunnel of Cavallino. A fascinating task but his dreams are track, racing cars. Next year he moved to Maserati and, in 1963, was hired by Lamborghini as chief designer; at Lamborghini he, along with Paolo Stanzani and Bob Wallace, designed the chassis of Espada and Miura.

In 1969 he started to design race cars for Frank Williams. In 1972 he founded and established Dallara Automobili in Parma, Italy. Starting from 1974, he and his company started designing a F1 car, the Iso-Marlboro IR, for the Williams Team. Another project included designing a race car to Formula 3 standards.

This resulted in victories in Italy, France, England, Switzerland, Germany, Japan, US, Russia and Austria. In 1997 Dallara and his company expanded into IndyCar racing, with many victories from 1998 until 2003.

Beginning in 2007, Dallara has been the single chassis supplier for IndyCar. Dallara later branched out into F1 in the mid-1990s but, by the end of 1998 Honda, coming to the new project as full constructor, called on the Italian firm to design the new F1 chassis for BAR-Honda, a plan later cancelled.

Begin in 2000 Dallara and his team were to build a race car for French team Oreca in Le Mans series and, in the August 2004, it was announced that they were signed by Alex Shnaider to build a chassis for the erstwhile Jordan team Midland. Later, Dallara brought along Gary Anderson to handle this project but, by mid-2005, he pulled out from it. In 2009, Dallara and his team began a project building a F1 chassis for team Campos, known later as Hispania.

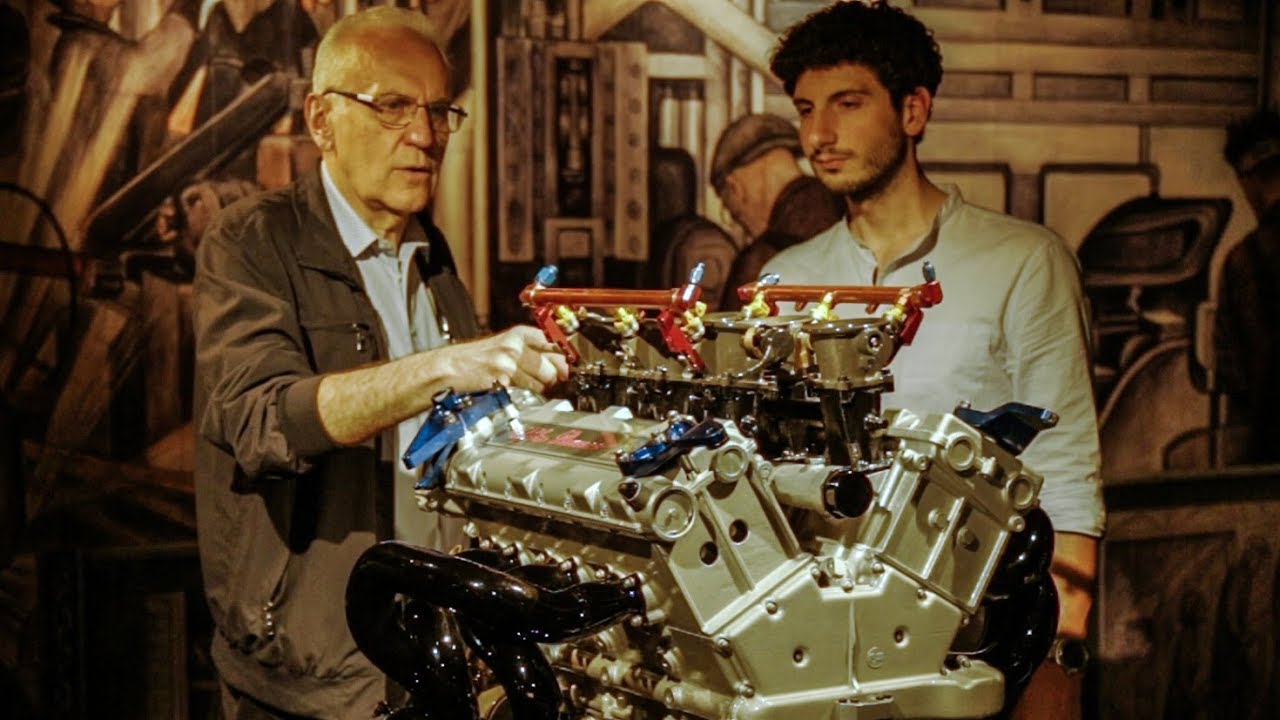

The presentation of Dallara Stradale was an opportunity to discover closely the secrets of the growth of a reality that has become the pivot of the Emilian Motor Valley, together with Ferrari, Ducati, Lamborghini, Maserati.

A source of innovation where engineers, designers, planners research and develop chassis and models for the most important car manufacturers. Every weekend about 300 cars made in Varano race on circuits all over the world and in various formulas and championships from IndyCar to Imsa.

The average age of the 620 employees is 34 years. Research and development are the gas that makes this all work, carbon fiber like cement for construction companies or silicon for smartphone makers. The history of engineer Dallara is that of an automobile myth: after several attempts with Maserati, Lamborghini and De Tomaso, here is the decision to found his own reality: in 1972, where the Dallara Stradale is assembled today, the Dallara Automobili da Competizione is born. In 1988 the debut in F1 with Alex Caffi driving.

The collaboration with Maranello restarts: Ferrari 333 is still the most successful in the ratio races – trophies won. The company, with a 90 million turnover, has invested 43 million euros in research over the past three years: “in competition you win or learn. Our maximum skills are design using carbon fiber composite materials, vehicle dynamics and aerodynamics” Pontremoli reminds. The turnover grows by 20% a year, 96% comes from abroad.

The testing of the Stradale was entrusted to drivers Marco Apicella and Loris Bicocchi. Eighty-one years and a long-awaited gift for the engineer Dallara: "we had been thinking about this project for some time but there was always some customer to satisfy. As I approached the eighties, I decided to make a change to make it happen. There is everything we have learned from racing and collaborations. I am convinced that those who will use this car will be able to experience the taste of traveling for the journey, the desire to get into the car to take a nice drive, the pleasure of driving. It is not a supercar, it is a simple car with no frills. I admit it: I'm very proud".

Giampaolo Dallara continues to live in his hometown of Varano de’ Melegari. He had two daughters, Angelica and Caterina. Both of them went on to work for the family company. Sadly, his youngest daughter Caterina died prematurely. She left an incredible legacy at Dallara, as she managed the company’s development in the American market, which led to the first Indy 500 victory in 1998.

One of Giampaolo’s greatest passions is soccer; he’s been a lifelong supporter of Parma FC. He also loves opera, particularly his fellow-citizen Giuseppe Verdi’s repertoire. When he has a spare evening, you’ll probably find him playing cards with his good childhood friends in Varano’s local bar.

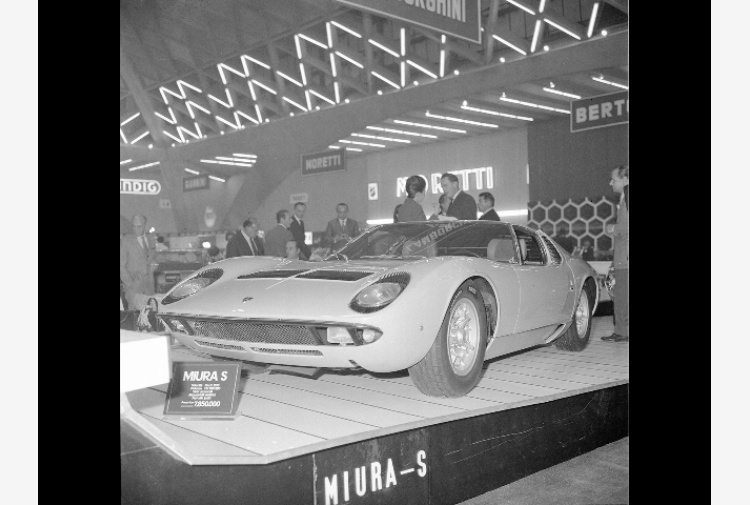

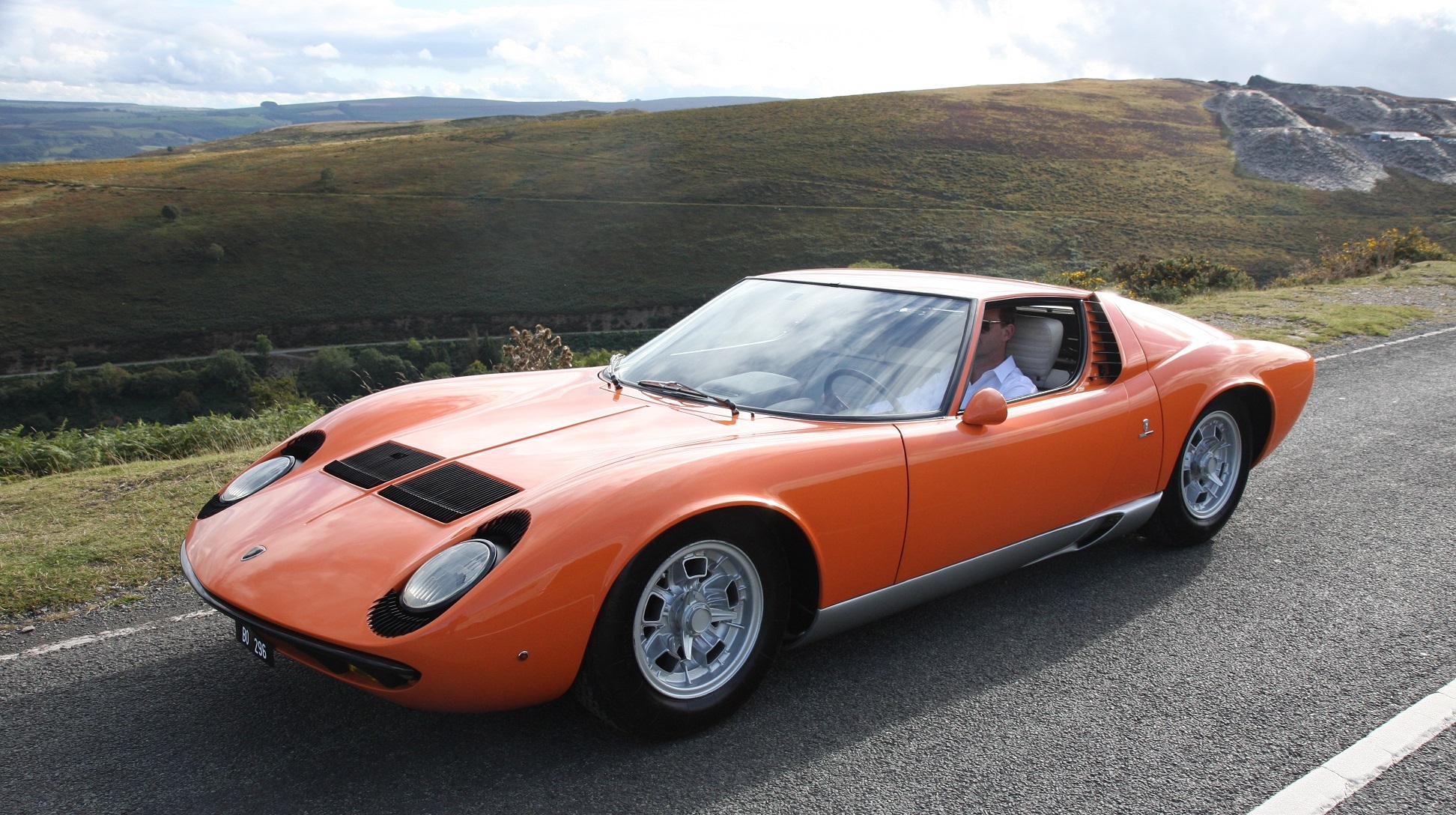

In history of made in Italy sports car a special chapter is dedicated to the Miura, the supercar of the 60s / 70s that Ferruccio Lamborghini wouldn’t have wanted to build but then was convinced by the designers Paolo Stanzani and Gian Paolo Dallara.

The latter, always considered together with Stanzani and Gandini one of the fathers of the Miura from the technical development point of view, was the most obstinate in supporting the goodness of that revolutionary project.

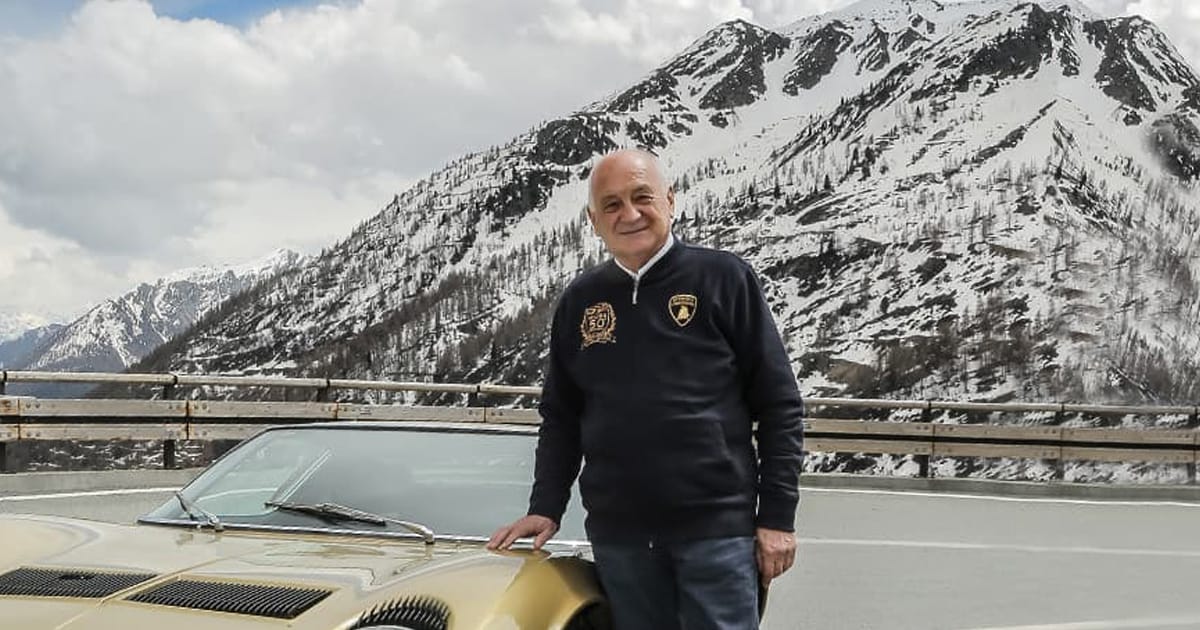

Dallara became so fond of that project to keep for himself a first generation specimen, to be precise the one with the chassis number 3165, bodywork 68 and engine 1400: an important "piece of history" returned these days to the headlines for having participated, in the United Kingdom, at the Salon Privé Chubb Insurance Concours d'Élégance, where it won first place in the category "evolution of the supercar pin-ups" (the event, among the most prestigious in the world, included seven categories with over 60 participating cars).

Giampaolo Dallara reminds Sergio Marchionne: "if in Italy there is still a car industry, it is to his merit."

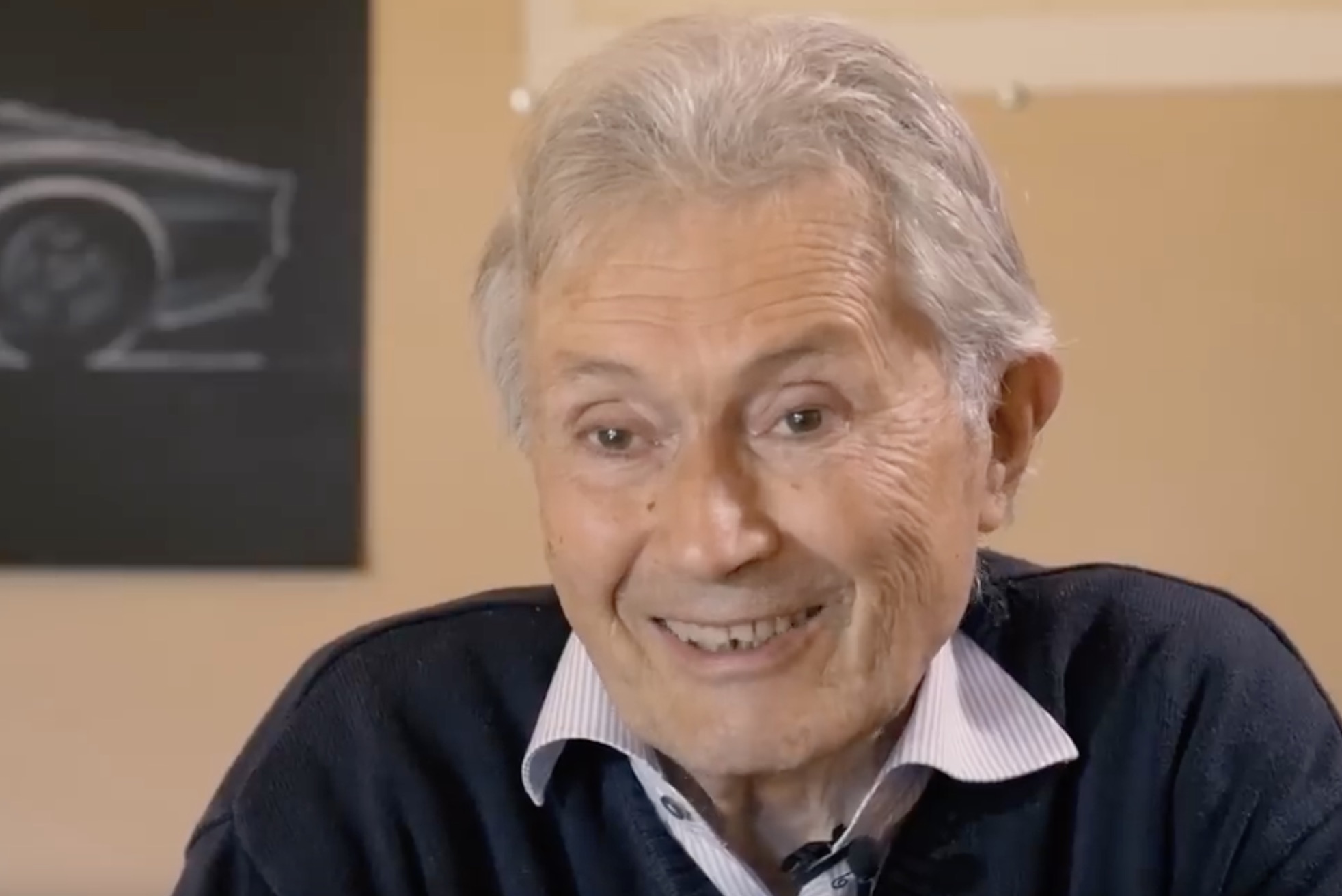

Giorgetto Giugiaro

“It wasn’t an architect or a designer who invented objects but an artisan.” Giorgetto Giugiaro

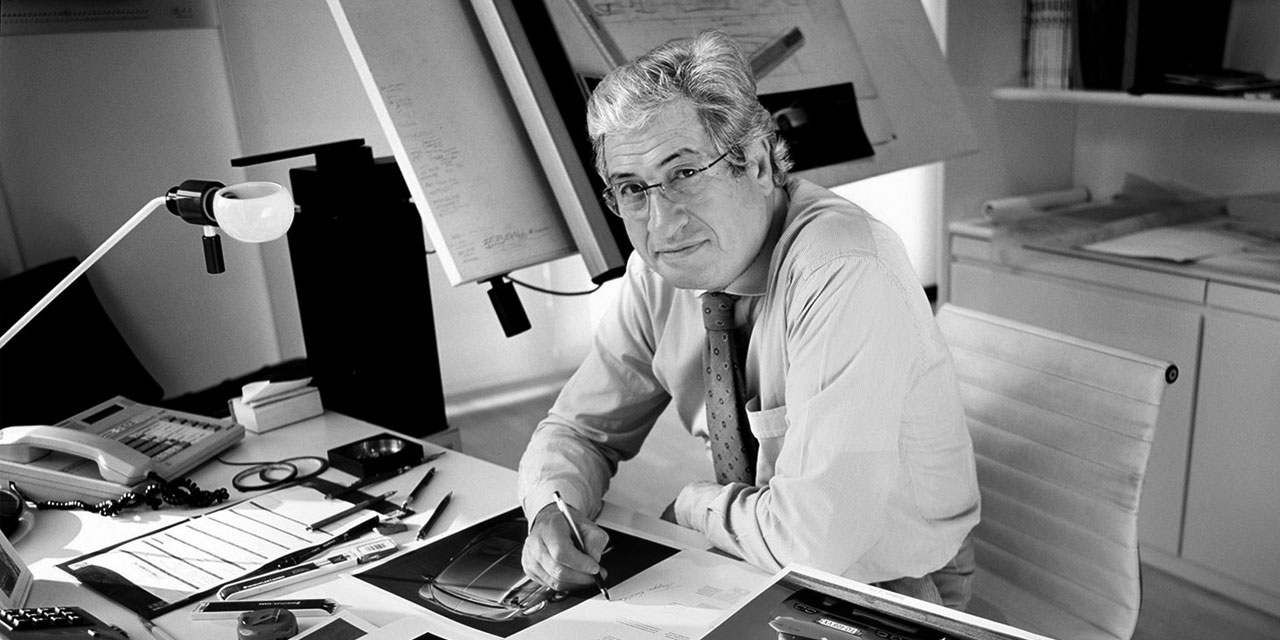

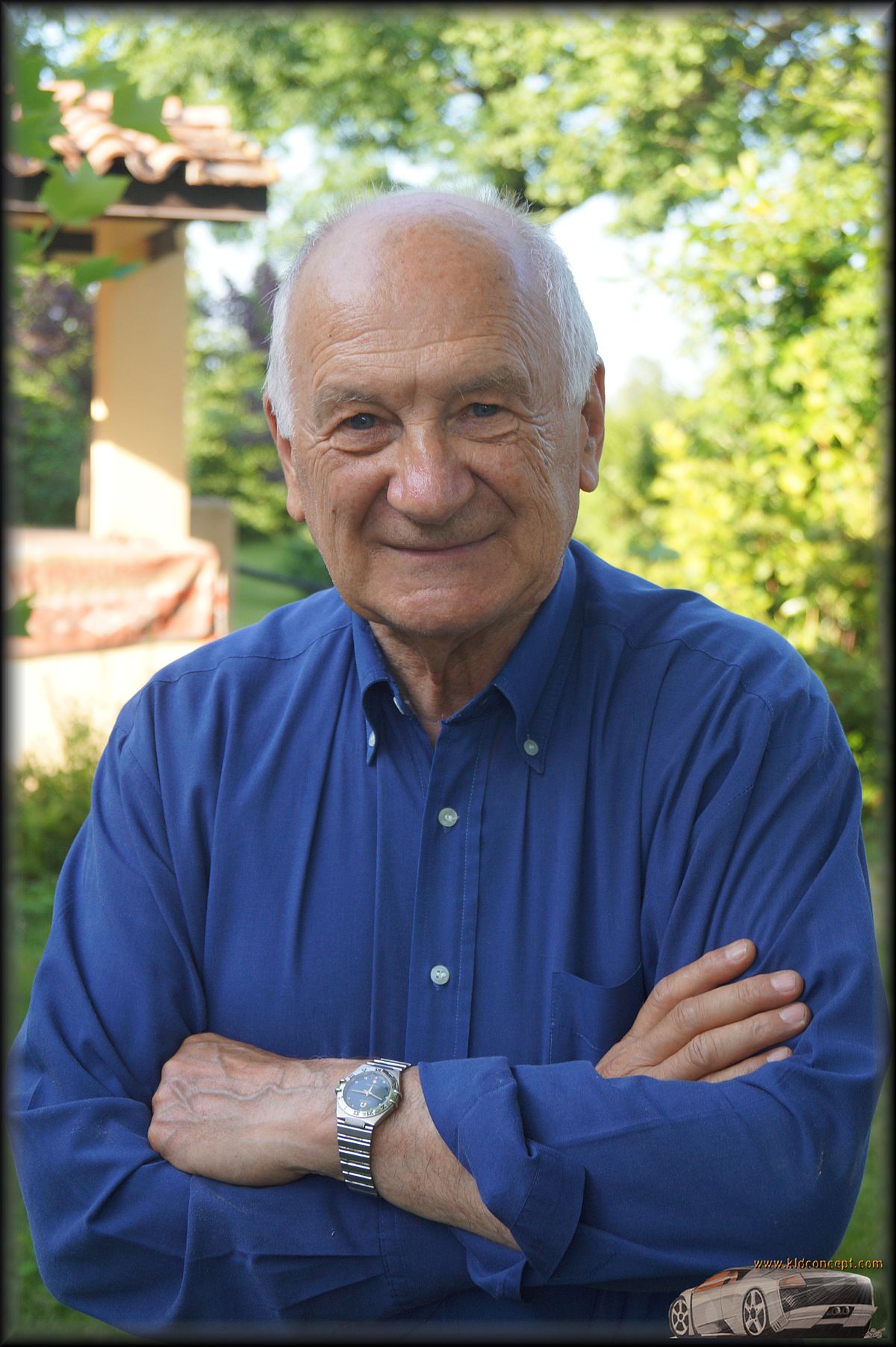

Giorgetto Giugiaro - born 7 August 1938 in Garessio, Cuneo, Piedmont - is an automobile designer who has worked on supercars and popular everyday vehicles.

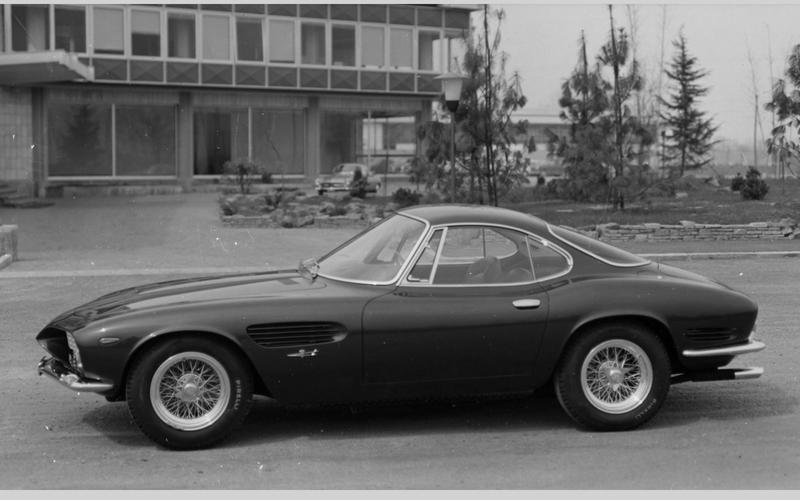

|

|

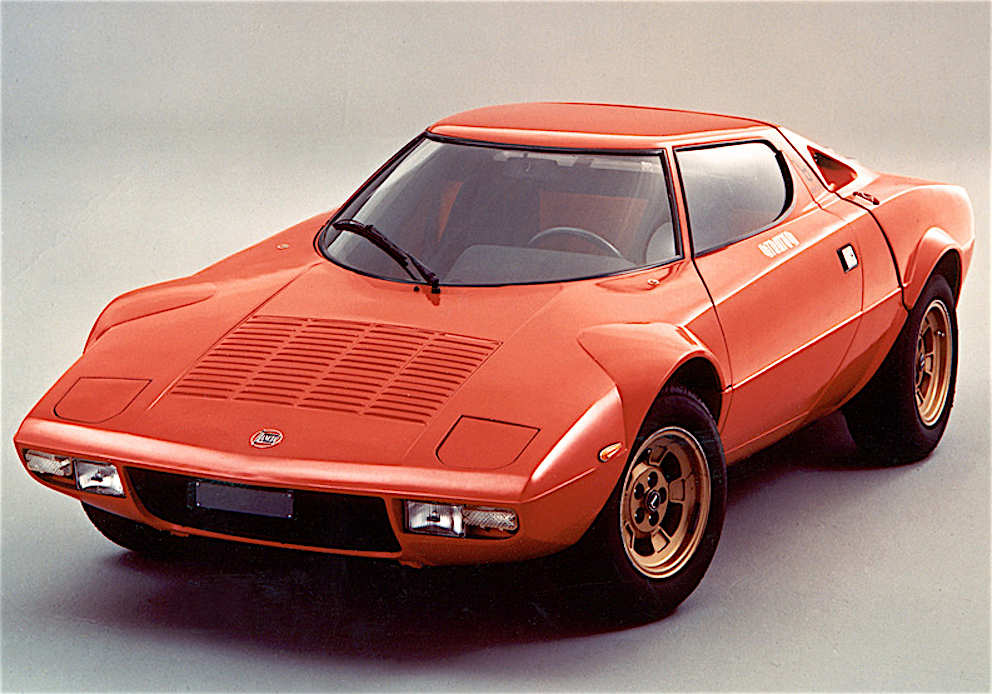

He was named Car Designer of the Century in 1999 and inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2002. Giugiaro's earliest cars, like the Alfa Romeo 105/115 Series Coupés, often featured tastefully arched and curving shapes, such as the De Tomaso Mangusta, Iso Grifo and Maserati Ghibli.

|

|

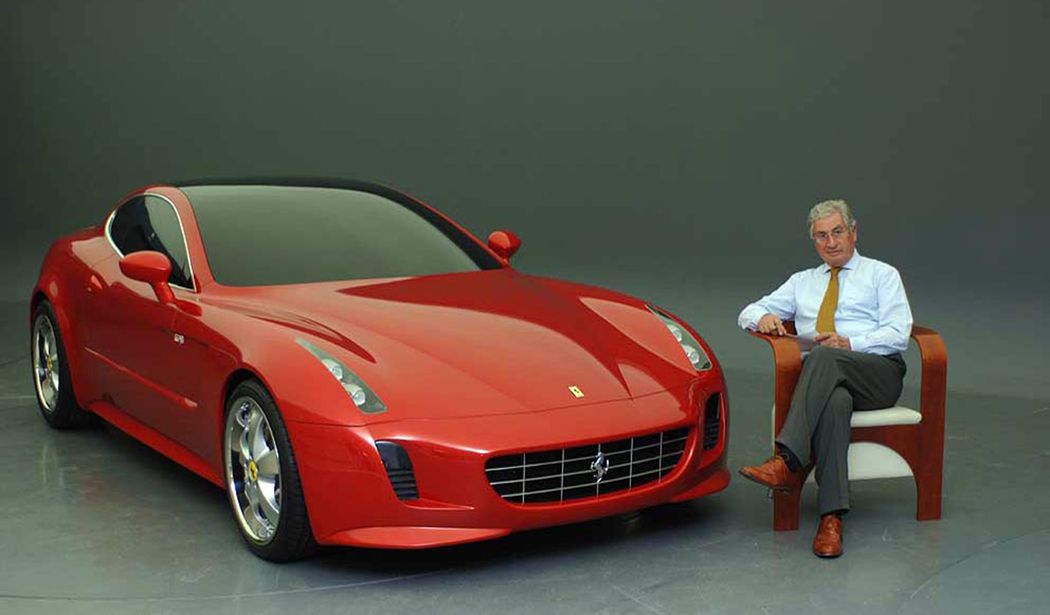

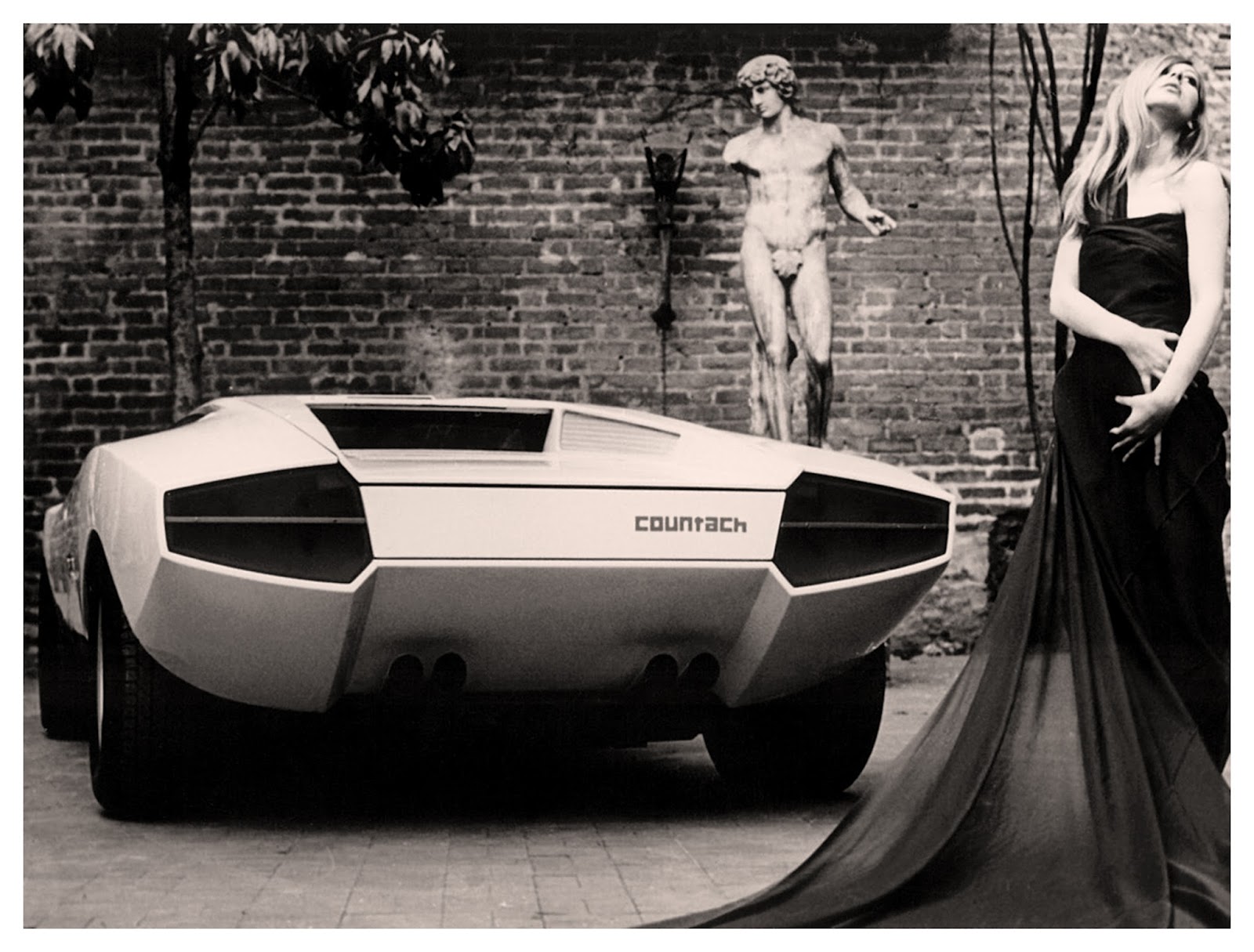

However, as the 1970s approached, Giugiaro's designs became increasingly angular, culminating in the "folded paper" era of the 1970s. Straight-lined designs, such as the BMW M1, Lotus Esprit S1 and Maserati Bora, followed before a softer approach returned in the Maserati Merak, Lamborghini Calà, Maserati Spyder and Ferrari GG50.

|

|

Giugiaro is widely known for the DMC DeLorean, featured prominently in the Hollywood blockbuster series Back to the Future. His most commercially successful design was the Volkswagen Golf Mk1.

|

|

Giorgetto Giugiaro, the most influential automobile designer of the 20th century, is referred to as the designer who had the greatest influence on the modern automotive industry and a variety of different vehicles – from ordinary hatchbacks to exclusive supercars – were produced according to his visions.

|

|

It is estimated that, in the nearly 50 years that Giugiaro headed Italdesign, the company developed more than 100 concept cars and 300 production cars of which more than 60 million units were sold. “When it comes to criteria for fine design, the proportions top the list. It is always somewhat of a mathematical game,” the design genius said.

|

|

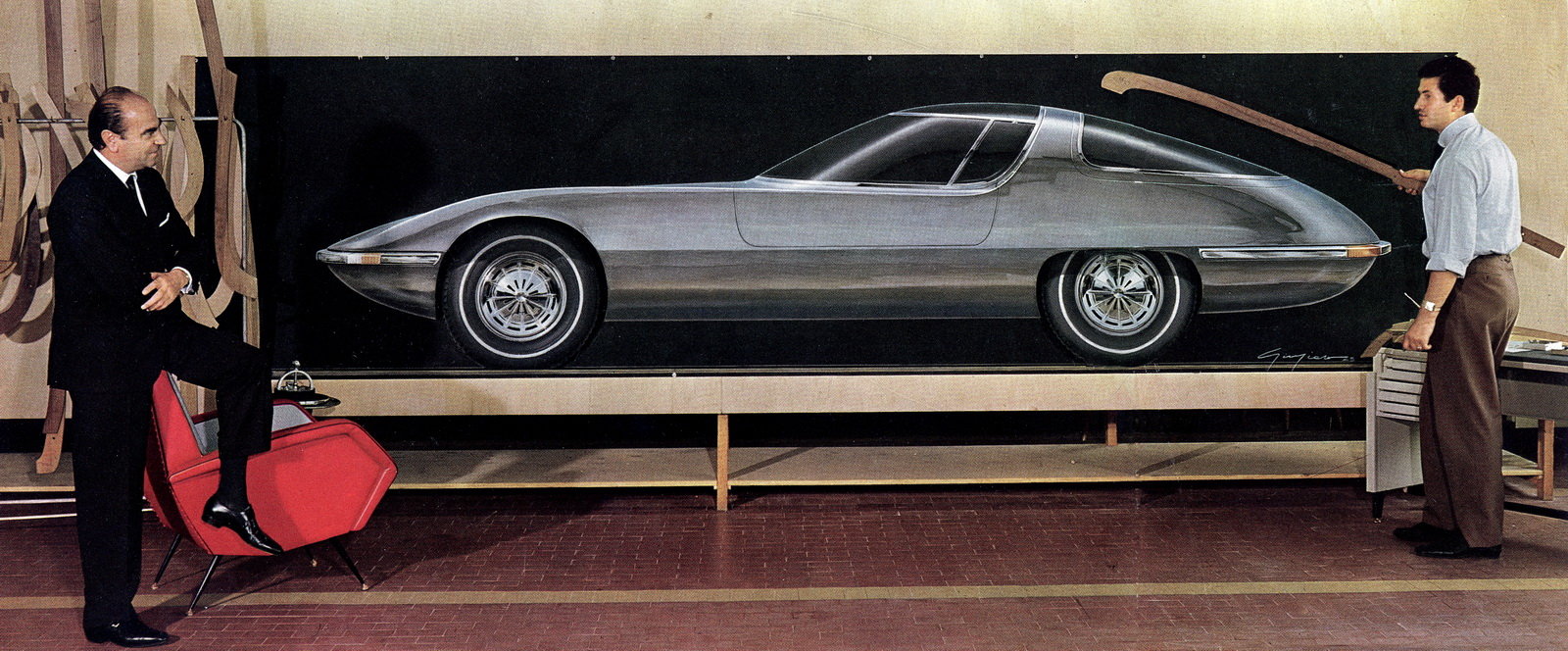

He began his acquaintance with the automobile industry at the age of 17, when he was invited to join Centro Stile Fiat. Until then he had no interest in cars and wanted to follow his father’s footsteps and become an artist.

|

|

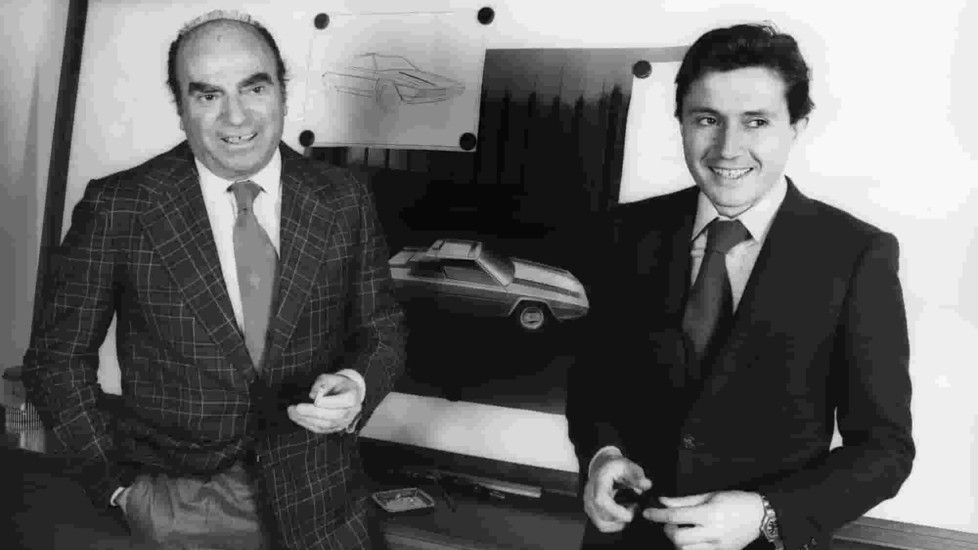

As a part of a large team, he quickly gained experience but not one of his proposals was approved. Everything turned upside down in 1958 at the Turin Motor Show, where Nuccio Bertone saw his sketches and decided to lure in the talented young man.

|

|

And that’s how Giugiaro, at the age of 22, became the chief designer at one of Italy’s premiere design studios. Giugiaro moved to Ghia in 1965. Immediately after, its management was taken over by Alejandro de Tomaso, head of De Tomaso Automobili.

|

|

Even though the two men didn't get along all that well, they still managed to design a few impressive models for that time: the De Tomaso Mangusta and the Maserati Ghibli that were born at the Ghia studio – both of which were characterized by a shark-shaped nose, a sloping roof line and a rather aggressive design – were unveiled in 1966.

|

|

However, Giugiaro didn't stay long there either – he left Ghia in 1967. One year later he decided to found his own company, Italdesign, in Turin; over time, this company began producing more than just cars, adding product and appliance design in the form of Ducati motorcycles, razors, furniture, hair dryers, bathroom equipment, watches, weapons, cameras and so on.

Italdesign stood out from its competitors for the fact that it created both design and prototypes and also provided engineering and testing services, so all the automakers had to do was take care of production.

Giugiaro’s work methods were unconventional. His unique trait was that he could come up with a basic idea very quickly.

In addition, he didn’t have to transfer the designs he came up with into clay models – he called this process a waste of time unless wind tunnel tests needed to be performed. 1:1 scale models were made by covering a wood frame with plaster. Furthermore, his company made prototypes from steel unless the customers paid for a carbon fibre body.

In 2010, Volkswagen subsidiary Audi acquired 90,1 per cent of Italdesign’s shares and it was announced in mid-2015 that Giugiaro would be leaving the company he founded to dedicate more time to his personal interests, so he and his son Fabrizio sold the remaining 9.1 per cent to the Germans.

Giorgio Langella

“At Alfa they can do gloves to flies.” Enzo Ferrari

Testing pills. After the chapter in which maestro Giorgio Langella, a former historical test driver of the Alfa Romeo brand, indicated the bottom, intended as sense of touch, as a tool to perceive every reaction of the vehicle, in this treatment Langella explains how the use of the accelerator is equally important. An element all too often underestimated. To think only ever loosely that it’s enough to always be with the foot down, using the command like it was a switch, has little to do with the canons of good driving. Using the accelerator correctly can even make a significant difference independently of the vehicle's qualities. “Also this sentence was offered us new Testers the day we first boarded a car, alongside a Master Tester, starting the adventure of this wonderful work.” “You drive the car with the accelerator.” It would seem a foregone phrase but its not. Just imagine to round a curve and figure out whether you can accelerate or not and, if so, when and how much to accelerate.

This was explained first in a theoretical way and preceded by explanations, demonstrations of how to sit in the driver's seat of a car, how to adjust the driver's seat, the backrest for an ideal and correct driving position. Then the correct position of the legs and of the hands on the steering wheel. It was explained that "you drive the car with the bottom" and also what is the left "footrest footboard". The story of the car you drive with the accelerator is immediately related to how to approach a curve on the road or on the track, what is the understeer and what is the oversteer. In practice they told us that, if you are careful and use the accelerator at the right time to approach and exit a curve, you won’t have to worry too much about understeer and oversteer because, by controlling the accelerator, you will be able to keep them always under your control in driving. And that anyway the oversteer, which you'll have to deal with when you come out of a curve, will happen because, after all, you will have wanted it. Provoked it. While you can control understeer by releasing the accelerator (a practically instinctive maneuver) because, they said, when you accelerate facing a curve the "centrifugal force" leads you to go straight even with steered wheels, when instead you release the accelerator this force is annulled and the steered wheels bring the car back to the desired trajectory, provided you have not exceeded all limits of course. Naturally, the higher the speed of the car with respect to the curve, the greater the effort to face it because greater will be the centrifugal force and the understeer.

Masters Testers were also saying that, in facing a curve, if you accelerate too much and too soon you will have to deal with understeer and if you accelerate too soon at the exit of the curve you will have to deal with oversteer, which in this case is called oversteer of power, therefore practically wanted. Also in this case the oversteer will be greater the greater the acceleration will be. They concluded by adding that there is an "imaginary line" taking a curve, which indicates when is the "right moment" to accelerate and it is when you perceive that the "nose" of the car points to the next section, which is the straight. The fact then that the front-wheel drive gives the impression, naturally perceived, of being more influenced by the understeer is given by the fact that, accelerating in power and in the wrong moment (that is to say too soon) facing a curve, the acceleration response in a front-wheel drive will be more immediate than the rear-wheel drive (under the same engine power for instance) even if it’s only a few tenths of a second because, while the front-wheel drive "pulls from the front" and therefore immediate acceleration, the rear-wheel drive must "push from behind". Here is a different feeling that can be perceived. So, in conclusion, both front-wheel drive and rear-wheel drive are always subject to understeer both on entry and along the curve but we can say that both behaviors are influenced more by acceleration, acceleration always "wanted". So, in practice and simplifying, "power” understeer and oversteer.

Giorgio Langella: heart of an Alfista. By Petrolicious Productions December 18, 2012. You’d be hard-pressed to find a truer Alfista than Giorgio Langella. Following his father’s footsteps, Giorgio went to work for Alfa Romeo at the young age of 14. Now retired, Giorgio takes great pleasure in sharing tales of his time at Alfa Romeo to a fellow Alfista. A charming and welcoming man, Giorgio’s voice and his words take on a mix of pride and nostalgia as he recounts his story.

Q: When did you start working at Alfa Romeo?

A: The 16th of January, 1957. I was 14. [The date comes off of Giorgio’s lips without missing a beat, as if forever imprinted in his memory as a significant milestone]

Q: What was your first job at that time?

A: I started out as a car electrician, then moved on to production.

Q: What other jobs did you have there?

A: I also worked at Autodelta for one year as a mechanic and electrician and then, in 1968, I settled back in Alfa Romeo as one of their official test drivers.

Q: What was it like working at Alfa Romeo and Autodelta back then?

A: There was a lot of respect for those who were our seniors and had been there for some time. They were considered the Maestros. We could assist them but, before we could put our hands on a motor, transmission, or any other part, we had to earn their trust. And it wasn’t easy, especially at Autodelta where they took great pride in their products and scrutinized every little intervention. At that time, the head of Autodelta was Carlo Chiti, a real tough guy. But it was beautiful working in those conditions, because you truly learned.

Q: What cars did you work on then?

A: In those years, I worked on the 2000 Touring and the 2600 Touring at Alfa Romeo and in Autodelta I worked on the Tipo 33 Stradale and the GTA. Every time the GTAs raced, they would finish in the top three.

Q: After Autodelta?

A: I went back to Alfa Romeo and became a test driver. Every car that would leave the assembly line would be test-driven around an internal track and the test drivers would then report any issues.

Q: As a test driver you also spent some time abroad, right?

A: Yes, I did a lot of testing in Finland in the cold as well as in the US.

Q: What was your experience like in the US?

A: Between 1988 and 1990 I spent a lot of time in the US to adapt and test drive the Alfa Romeo 75 [aka Milano in the US] and the 164 for the American market. They had different regulations than in Europe, so modifications to suspension, tires, catalytic converters and others had to be made. And we had to test in the cold and hot environments of the US. I have to say that, right from the beginning, I was always made to feel very welcome by Americans, perhaps because I’m Italian and was driving an Alfa!

Q: What was it like driving in the US?

A: Whenever I drove on public roads in my Alfa, someone in an American muscle car would always challenge me to a race. I would always win, of course! I had to uphold the Alfa Romeo image, after all. At the end of each race, they would ask to see the Alfa up close. They were very fascinated by the Alfa.

Q: What was your favorite Alfa Romeo of all time?

A: My favorite was without a doubt the Alfa Romeo 75. It was a perfect driver’s car. With a 52/48 weight distribution and a very potent engine, you could make it do whatever you wanted. When I test drove it for the first time, the master test drivers told me “this is a car that you drive by the seat of your pants.” Because your butt and your back act like an antenna when you drive and they pick up every little movement of the car. In fact, car seat design takes this into consideration in addition to just comfort. And having test driven so many cars, I can tell you that the Alfa Romeo ES30 Zagato and the 75 were practically perfect.

Q: What’s your sweetest memory from working at Alfa Romeo?

A: I’ve now been retired for 19 years and I still dream about being called into work to go testing on the Balocco test track. Being an Alfa test driver was the best time of my life. It was a very prestigious career and it wasn’t for everyone. I had the honor and fortune to be able to test drive all the prototypes and to be able to develop them and this is a thing of excellence. The love for that work can only be compared to the love that I have for my wife. It’ll never end and I swear to you that, whenever I speak with my ex-colleagues, it’s a sentiment that we all share. I often look at the photos of those times and even listen to a recording I have of the engine of the 75 going around the Balocco test track and I remember every single turn and every single sensation.

Giotto Bizzarrini

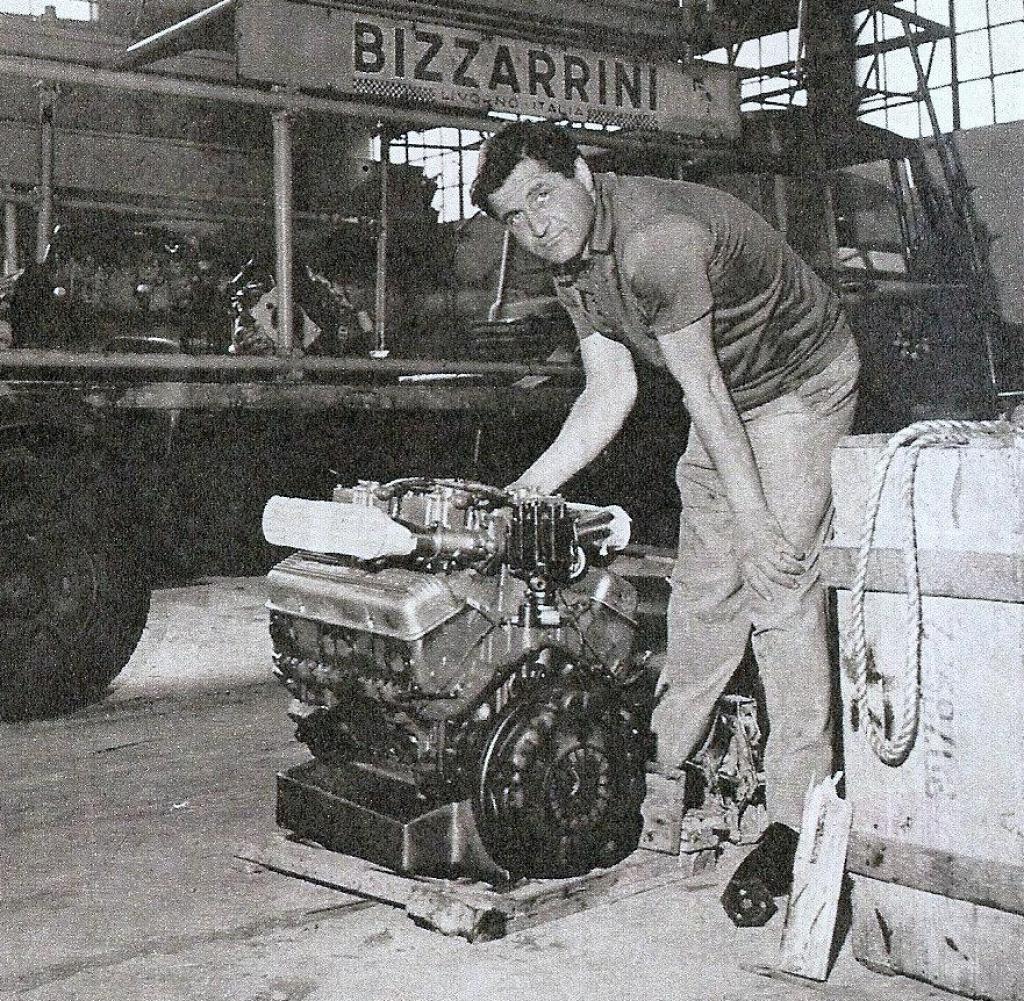

The story of Giotto Bizzarrini, the wild genius, seems to be that of the protagonist of a fairy tale set in the motor world. One might think he had an important design studio; no, it was a simple workshop and he had it in Rosignano Solvay, near Livorno, where he still built Bizzarrinis, those made by him with his own hands.

Even if they could not be called this way, with his name, due to the numerous economic adversities of which his life is full of. But he closed down "because of having reached the age limit", he told us years ago. His dream is to be a designer ... or rather a test mechanic, as he likes to call himself, or a pilot engineer, a role he perhaps prefers.

He was about to step into the role of builder on his own, with those beautiful for everyone but only for him failed (from an economic point of view) GT Strada - “If I can make cars by myself, why do I have to build them for others?” – all made in Livorno, except the engine.

His is an adventure which will end badly under the entrepreneurial aspect but magnificently for the international success that his berlinette will have. An adventure of the many like when, during the war while American bombings rained down on Livorno, he dived to collect fishes that were killed by the bombs that ended up in the sea.

“They never hit the bridge ... but the fried food was assured!” The people of Livorno are a bit crazy, extrovert, cheerful, brave, different from the other Tuscans because Livorno has a particular, fascinating history. Here Bizzarrini is famous but in America, when they invited him for the events related to his cars, they rolled out the red carpet.

Because like another famous Tuscan, the immense artist of Vicchio del Mugello, he is the author of the second Giotto O, the Ferrari GTO. He received an order from Enzo Ferrari: “Bizzarrini, you have to make me a car that is fast but fast enough to be the fastest Granturismo of all time.” And the myth was born, the most famous car in the world.

«I didn't do much; Ferrari gave me an old berlinetta to modify and locked me in a small space located in the factory, in Maranello, far from prying eyes. No one, I mean nobody not even design office, had to know what I was doing. Every day he came to see what I was doing and finally I told him: engineer, look, don’t deceive yourself because some time is needed! But I was also surprised when the car, the "Duck", was ready. It ended up I have been quick, I almost didn't believe it but I didn't perform any miracle, the car was already there! The body? I used a willing coachbuilder nearby who modeled aluminum; nothing special. The real GTO, the standard one - so to speak -, came later but mine also was fast, of course it was fast!» His skills in elaborating a car and making it go fast were proverbial.

But he is modest, he is from Livorno: «the Livornians are concrete, the merits must be earned; only when we have reached them you can we speak". Giotto is not one to incense himself and the episode of the round trip to Maranello in 1957, in a few hours with the famous modified Topolino, which he likes to tell is significant.

When, after some time, he asked Enzo Ferrari why someone like him, accustomed to choosing only technicians of great value, had immediately hired him, the Drake replied: "that you were not very intelligent I had noticed but you had the courage of a lion!"

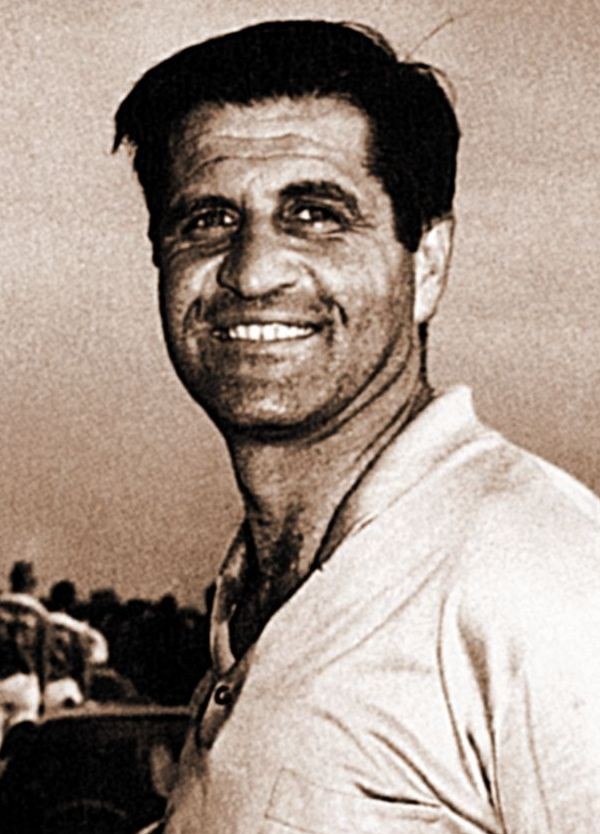

Giotto Bizzarrini (born 6 June 1926 in Quercianella, Livorno Province, Italy), car enthusiast and creator of some of the most important cars in the history of motor racing, is an automobile engineer active from the 1950s through the 1970s. He was the son of a rich landowner from Livorno.

His grandfather, also named Giotto Bizzarrini, was a biologist who had worked with Guglielmo Marconi on his inventions, especially the radio, following which one of the Livorno Library sections was named The Bizzarrini Library.

He lost his father at a young age and grew up with his mother and aunts, who allowed him plenty of freedom. He loved hunting and would spend long, solitary days enjoying his favorite pursuits in the fields of Tuscany.

“I grew up wild,” he would later admit “and in that period of growth and development when a young man should be learning how to interact with others I was alone.” As a flip side to Giotto Bizzarini’s personality as a strong and rather hard young man with a measure of difficulty interacting with others, there was the early evidence that he was also something of a genius.

He received an engineering degree from the University of Pisa in 1953 at a very young age. His design thesis in his senior year was a complete redesign of a used Fiat Topolino, in which he modified the engine for increased power and relocated it in the chassis for improved handling.

After graduation, he taught briefly before joining Alfa Romeo. In the middle of the 1950s Alfa Romeo was, technologically speaking, one of the most renowned, interesting and appealing Italian car makers and the cars manufactured in Milan at that time are still considered a reference point for the whole industry.

Giotto was assigned to the development of the Giulietta chassis, which was disappointing as he aspired to become a powerplant engineer. He was later able to move to the Experimental Department under Ing. Nicolis in August 1954, receiving on-the-job training to become a test driver: "I became a test driver, who coincidentally was also an engineer with mathematical principles. I always needed to know why something fails, so I can invent a solution."