(When sex was safe and racing was dangerous)

Formula One (also Formula 1 or F1 and officially the FIA Formula One World Championship) is the highest class of single–seat auto racing. The F1 season consists of a series of races, known as Grands Prix (from French, meaning grand prizes), held worldwide on purpose-built F1 circuits and public roads. Formula One cars are the fastest road course racing cars in the world.

Although the basic formula remained unchanged, in 1958, races were shortened from around 500 km/300miles to 300 km/200 miles.

The first Formula One World Championship race is held at Silverstone, England, in 1950. The cars were designed purely for speed, with front engines and drum brakes - a fascinating experience without medical back-up or any form of safety net.

In the 50s there wasn't a safety culture. It was just after the Second World War - people were used to the idea that people could die and people found it almost acceptable. Being a professional racing driver was unbelievably dangerous. Even seatbelts were not made mandatory until 1972.

1960 was a season which highlighted the dangerous nature of Grand Prix racing in the early years. Two drivers died during the Belgian Grand Prix in Spa and two more were seriously injured. The highly talented Chris Bristow lost control of his Cooper and did not survive the subsequent terrible cartwheeling. The second tragedy was the death of Alan Stacey. The Lotus driver left the track because a bird flew into his face at top speed - full-visor helmets did not come into use until eight years later...

Counting up how many Formula 1 drivers were killed, you get high numbers - 29 deaths in the 1960s and 18 in the 1970s.

Racing legend Sir Jackie Stewart has said that during the years that represented the peak of his career in the late 1960s and early 70s, anyone continuously racing had a two-out-of-three chance of dying.

Tracks could be up 15 miles long. The Nurburgring was that sort of length, and getting safety cars to support the drivers in the event of an accident…was almost impossible. So, road circuits of that type gradually disappeared. The last time that the Nurburgring was used was that 1976 race where Niki Lauda was so badly injured, pulled from his burning car.

Conditions for today's Formula 1 drivers are, thankfully, much safer. But a question arises:

Are modern Formula 1 cars cool? Well, they might be cool in terms of their cutting-edge technology and exotic materials, but how many people look at a current F1 car and dream about it? Not many in my experiences. I think most people (regardless of age) will agree the Formula 1 cars of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s had a personality that today’s machines just don’t have.

Not only were the iconic F1 cars of the past raw and mechanical in a way that today’s computer-laden machines aren’t, but style and character helped set each car apart on the grid. There’s a reason that even younger people born well after the ‘glory’ years of F1 still love the classics. It’s not just nostalgia.

"Ah, when sex was safe and racing was dangerous!"

Grand Prix racing is a roll call of the quick and the dead. Yes, racing is dangerous, it has always been dangerous, and it will always carry a certain amount of danger—but there used to be a time when our only response to such heightened levels of danger was a well-meaning shrug and a moment of silence. Not coincidentally, this is also the period in racing that we celebrate the most.

Sir Jackie Stewart was the most prominent figure to speak up about driver safety, and he was mocked for it. "Leave motor racing to the men," they told him: the same sort of people who today grin when they tell you about the time when sex was safe told him to go home, stop racing. If you can't stand the heat, to trot out another cliche, stay out of the kitchen.

But "to be a racing driver between 1963 and 1973 was to accept not the possibility, but the probability of death," he wrote, starkly, for Britain's Telegraph, an excerpt from his 2007 autobiography: "I somehow taught myself to compartmentalise my emotions, to lock them in a box and put them away… then I would be able to climb back into my car and go racing again."

The three-time World Drivers Champion spoke from personal experience. He had to. You have to, when 57 of your close friends die on the track. Most people can't even point out having 57 friends, much less dead ones. “Why did I look in my rear-view mirror every time I left home to race and wonder whether I would see it again?”

Formula 1 was one of the world's most dangerous and exciting forms of sport. Its golden age, the 60s and 70s, was also its deadliest, when drivers lost their lives at frightening rates. The killer years: when F1 was sexy and dangerous.

So F1 fans chin up! Here is a quick trip back to the golden early days of Formula One in the 60s and 70s. In some ways it is a bitter sweet journey for many of the stars of these images met awful premature deaths.

Heaven knows what kind of impact these deaths must have had on the other drivers. And spurred on by a public, who were now getting sick of seeing images of grieving girlfriends with tear-filled eyes tucked behind their shades and the staff of constructors teams with ever more furrowed brows, Jackie Stewart and other drivers embarked on a long journey to make the sport a safe one.

In spite of the tragedies though, there is something incredibly glamorous about F1 in the 60s and 70s. Maybe it is clothes, the hair (or the sideburns as a certain person got bang on here), the curved shape of the cars or the stunning backdrops of circuits like Monaco (when they weren’t only a quick and cheap Easyjet flight away), but it just seemed way more sophisticated, elegant and classy back then.

Let’s celebrate the all too brief lives of some of F1’s true giants. Formula 1 these days is nothing more than a sponsored procession. Back in the sixties however every corner was a thrilling, terrifying dice with death as cars were made 'lighter, then lighter still'.

I do try and try to watch a Grand Prix every now and then but soon after switching on, I switch off. Was it always so boring? Were the cars always so spread out? Did they always all look the same?

No. Once upon a time it was not boring at all. Once upon a time, it was frightening as hell.

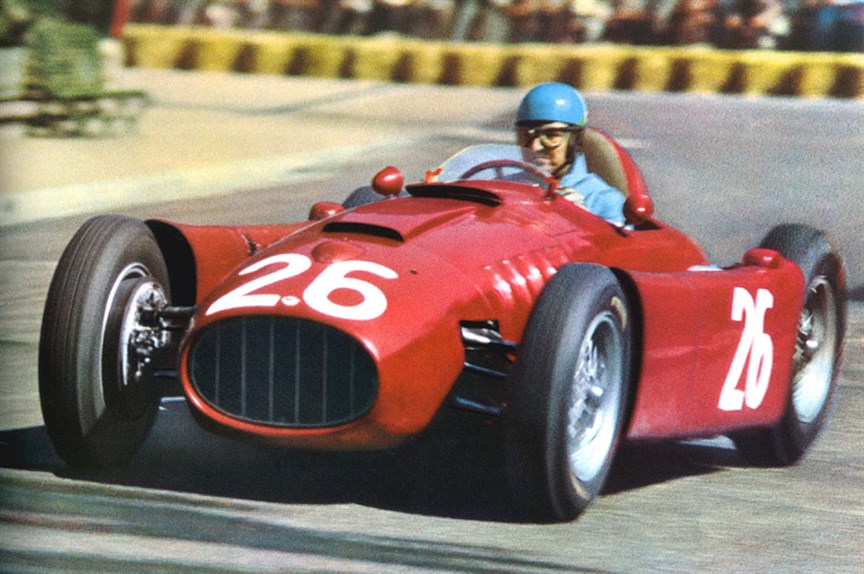

Nowadays all the Grand Prix cars front and back wings look like they were bought from ‘Grand Prix wings dot com’. It’s because they are designed by computers and the same designers keep switching from team to team, lured by more money. But rewind to the 60’s and a car could look like a fine cigar. When interviewing John Surtees OBE for my film ‘The Killer Years’ I was lucky enough to see his red Ferrari 158, in which he won the 1964 World Championship, being delivered for his annual spin around Goodwood. This car is beautiful to look at. John struggled to get into it – not because of his advanced years, but because it was bloody awkward, windscreens being too fragile, the gear stick being in a silly place, steering wheel fixed firm. Getting in and out was not a priority. Looking fantastic was.

Two large chromed exhaust pipes strut out from the back of chromed suspension parts and a hand crafted curvaceous blood red body. ‘Why does this car look so good John?’ I asked. ‘it is beautiful because it was designed by an artist - Mauro Forghieri’. Mauro did not get his inspiration from fine Italian leather shoes however. He had studied the work of maverick designer Colin Chapman’s racing cars. Chapman, the dynamic son of a publican, went on to design what must be the most beautiful car ever made – the Lotus 49. With its fat tyres on massive alloy wheels, the low profile shark like nose and chromed engine parts, this car oozed sex. It had all the machismo of a hot rod, only it was the fastest racing car of its day, leaving everything in its dust.

On a long straight in the woods, Jim lost control of his Lotus, hit the trees, and was killed on impact.

Sadly, what made it look so sexy also made it totally lethal. ‘Make it lighter and make it lighter still’ was Chapman’s philosophy according to officionado David Tremayne, ‘And when it breaks, make it even lighter’. According to Chapman, the perfect racing car would win a race and then fall apart on the finishing line. Sometimes they fell apart a bit too early. Sadly, the last thing on Chapman and any other race car designers mind at the time was the safety of the driver. The idea of a tub that can look after a driver in a 200 mile per hour smash would take decades of fear to evolve.

So one misty April morning in 1968 at Hockenheim, Germany, the mechanic of the most famous racing driver of all time, sheep farmer Jim Clark, checked the wheels and gave the world’s most beautiful car a last quick polish with an oily rag. ‘It will stay with me forever... to me he is immortal’. Mechanic Beaky Sims would be the last person to speak to Jim Clark. On a long straight in the woods, Jim lost control of his Lotus, hit the trees, and was killed on impact. David Sims [inconceivably today he was the only man to work on Jim’s Grand Prix car] has spent the rest of his life wondering if it was something that he did or did not do that was the cause of the death of the best and most humble racing driver that ever lived. ‘I was only a kid, I was only in my twenties’ says Beaky. He has been scarred by this tragedy as it was all too obvious his death was not necessary. Sir Jackie Stewart is still livid to this day. ‘Jim Clark died in a forest, hitting young and old trees alike. He did not have a chance’.

Here was the problem. These gorgeous cars were attracting young people to the sport, to watch and to take part, only for some of them to be smashed to pieces in them or even worse, burnt alive. The wreck of Jim Clark’s Lotus 49, bent amongst the branches, was adorned with the ‘Gold Leaf tobaccologo. When I see this image today it looks so weird, someone’s death endorsed.

‘Jackie Stewart: I and my wife Helen counted one night over fifty drivers that had been killed racing. Fifty! We were not at war, we were taking part in a sport, a pastime for public enjoyment!’

The Killer Years is about a time when racing was exciting but when racing could also be pure hell. As writer Vicky Parrot put it when I showed her the film ‘When you see Bandini on fire in his Ferrari, it really is sickening. I used to think the good old days were the best but having seen your film John, I will never ever say that again. I cried out loud’.

Drivers were friends, a solid group. When they were leaving home in the morning, they didn’t know whether they would be returning at night.

A generation of charismatic men that, searching for glory, risked their lives in the bloody period of this sport. Legends, such as Mario Andretti, James Hunt, Niki Lauda, and Jackie Stewart, live on.

And Michael Schumacher: a supporter: “2002 was my first year and although it is considered a boring year by many, it remains one of my personal favourites. But what I miss dearly is the scream of a V10 going past… I would turn the volume up so loud my hairs would stand on end and tears would form in my eyes, and I was only 8 years old. Now revisiting videos where I can hear that sound makes me sad when I think of the horrible monotonous low-revving drone of the severely rev limited V8s of today”.

Drivers who risked and lost their lives changed one of the most exciting sports forever. Formula 1 races have never been for weak-hearted, but men are always looking for the next limit. In the 60s racing car engines started to double their power and reach incredible speeds.

With a new television audience, the arrival of money and sponsorships, pilots started to become real superstars - modern gladiators thrown in the spectacular arena of Formula 1, and key players in the period of the birth of the most incredible and adrenaline-infused sport in the world.

Jackie Stewart: “Many drivers were convinced that it was always someone else to whom it could have happened. Never thought that the accident could have happened to them ... the truth is that we all are, always, on a thin line between life and death."

Survivors of the most heroic years of F1 remember the speed, the glamor, the danger of their era. From sixties and seventies - the power increasing exasperatedly; the discovery of aerodynamics and ailerons. The ones of Jochen Rindt, François Cevert and guardrails, Niki Lauda, Ronnie Peterson and the fire. That, in short, was where you could never take it for granted to bring home the skin.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment