David Sedgwick wrote in his article of 26 August 2014: as the scarlet racing car hurtled through the air on a dark, soulless morning, its driver startled to glimpse the tops of pine trees which abounded around the race track, knew in an instant that he was in very grave danger.

Those few seconds would be etched deep into the pilot’s mind for the rest of his days. A red missile, the car speared into the skies at over 170 mph. The pilot closed his eyes and waited for the end.

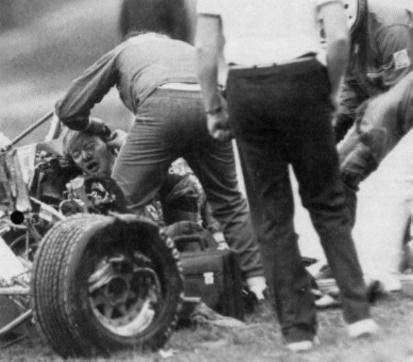

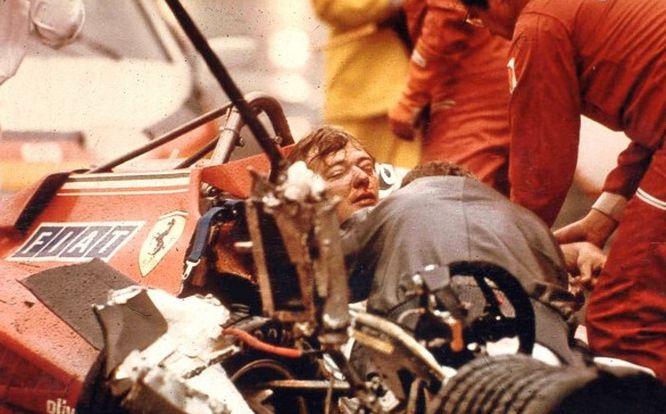

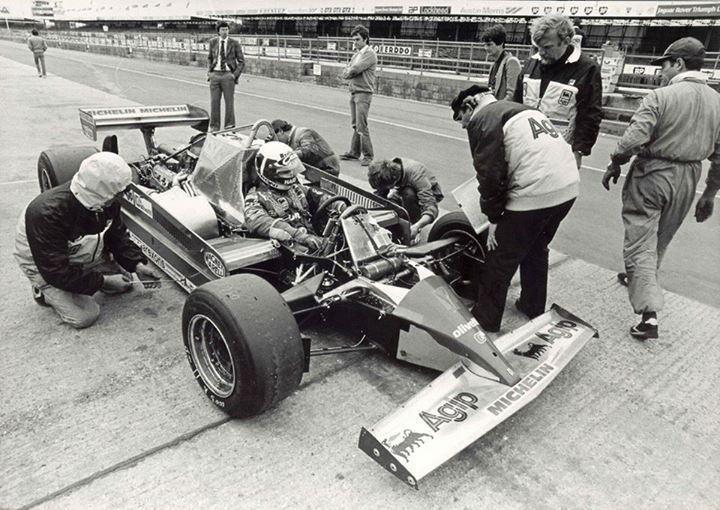

Didier Pironi at Hockenheim in 1982.

August 1982 and F1 World Championship leader Didier Pironi was putting his Ferrari through its paces on a grim German morning, one of only a few cars to venture out of the pits that morning. Most drivers had taken one look at the circuit and scurried off to the sanctuary of garages and team motor homes. Not so Pironi. The Ferrari pilot steered his mount out onto the treacherous circuit without so much as a moment’s hesitation. The skies around Hockenheim darkened. The car felt good on the slippery circuit, very good. Soon the Ferrari was four, five seconds faster than anyone else. The wet Goodyear tyres bonded the car to the track. Didier opened the throttle. The whine of the Ferrari’s 650 bhp V6 turbocharged engine reverberated around the circuit, breaking through the eerie stillness of the morning. The French driver was revelling in the feedback from the Harvey Postlethwaite-designed 126C2 as he skimmed around the sodden German circuit. Didier felt good, invincible almost. The Ferrari, now invisible amid a thick curtain of spray, headed confidently out into Hockenheim’s forest section, a fast, sweeping, ghostly couple of miles which snake away through dense pine forests. Didier flicked the car into the south straight. Ahead was a huge ball of spray containing the Williams car driven by Derek Daly. Approaching 170 mph Pironi was instantly upon the Wiliams, its Irish driver duly moving off the racing line to allow the Ferrari past. At least that’s how the situation looked from inside the Ferrari cockpit. But there was another car out there hidden in that ball of spray, unseen by Didier. Directly in front of Daly’s car was the Renault of Alain Prost. The Williams moved off the racing line. Trusting in himself and his God and without even the slightest lift off the throttle, Didier disappeared into the spray…

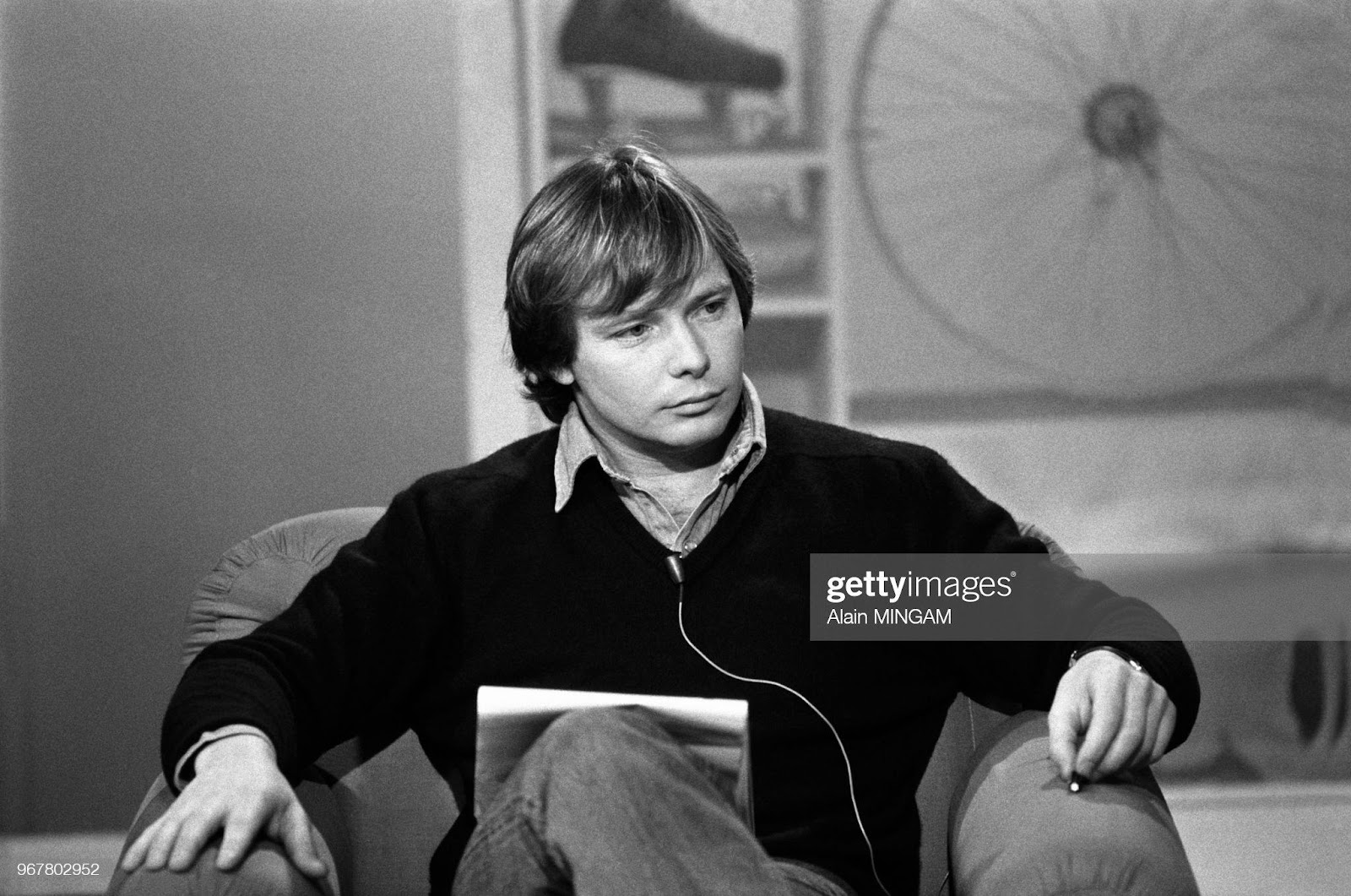

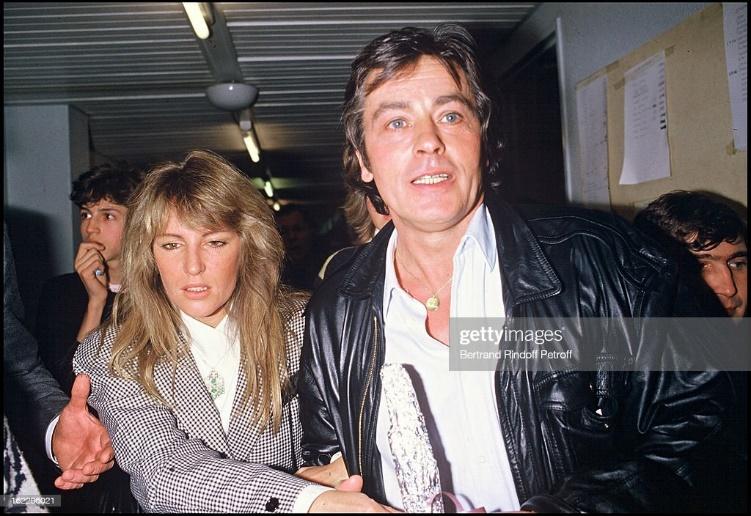

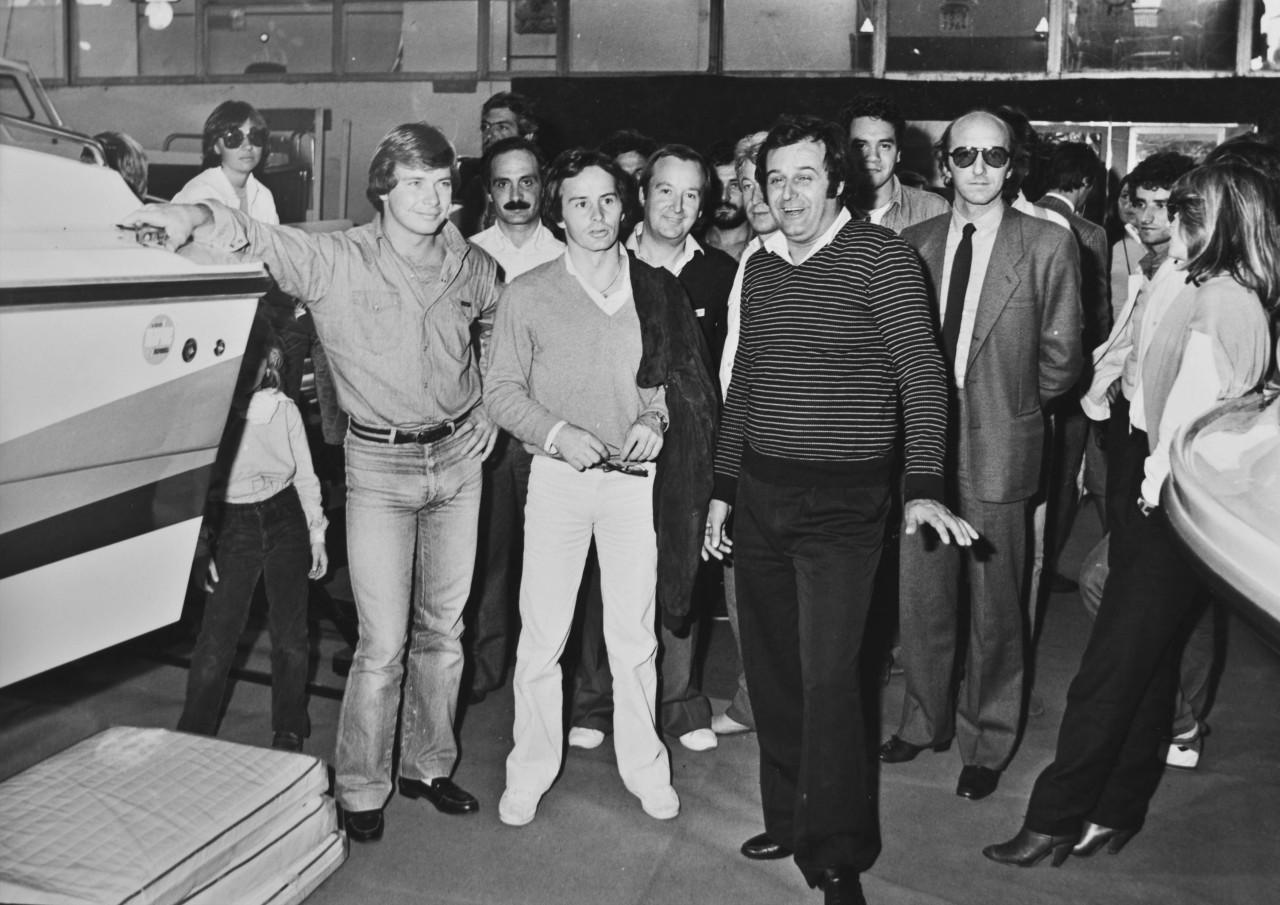

Didier Pironi on the set of an Antenne 2 program in Paris on January 30, 1982. Photo by Alain MINGAMGamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

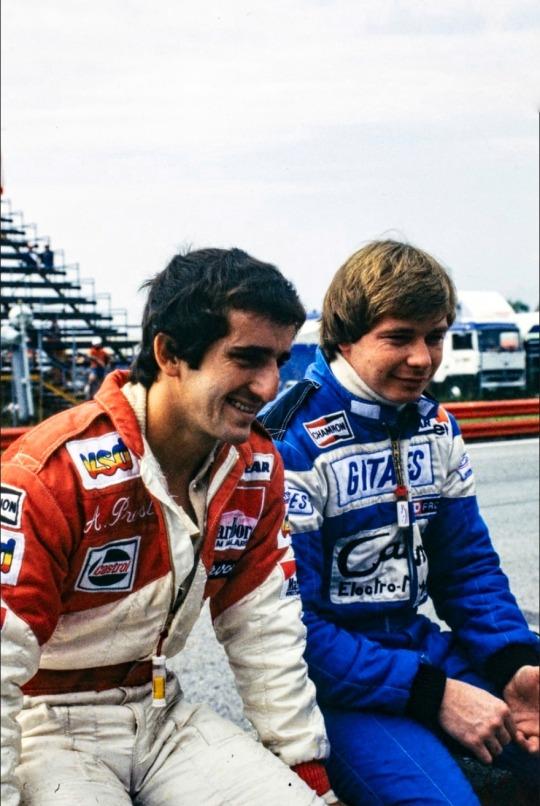

Summer 1982 and everything was coming together for Didier, professionally at least. The angelic looking Frenchman was riding a crest of a wave having recently assumed leadership of both the Ferrari team and the world championship. Didier’s ambition to become France’s first F1 World Champion was tantalisingly within reach. Yes, conditions out on the Hockenheim track were atrocious – rain in this part of the world can reach biblical proportions; and yes, Didier had taken pole position the previous day with a scorching lap of 1’47.947 - almost a second faster than his nearest challenger. The race victory seemed a formality. Why take such risks? Pironi they muttered, was crazy, one or two even suggested he had a death wish. Indeed colleagues and people who knew the French driver would readily attest to a level of bravery which bordered on the abnormal. “Didier had very big… huge balls,” said former team-mate Jacques Laffite choosing his words very carefully. “He was a very good guy.” The impact was as sudden as it was violent. In the cockpit of his yellow and black Renault Alain Prost, caught between concern for his colleague and the desire for self-preservation, watched in horror as the Ferrari catapulted over his own cockpit. “Pironi’s car went straight on into the air, almost thirty metres up. I prayed I would stop, because I had no brakes,” recalled Prost, who had been tiptoeing around the circuit minding his own business when the Ferrari had ploughed into the back of his car. The events of that day would haunt Alain throughout his career. “Every time I drive on a wet track, I look in my rear view mirror and see the Ferrari of Didier flying.” “All you could see of cars ahead were great balls of spray,” said a shaken Derek Daly later. It had all been a tragic misunderstanding, an accident waiting to happen. Hidden within that ball of spray, Prost’s Renault had materialised out of nowhere like a ghostly spectre. Didier had not stood a chance. Like a tumbling Olympic gymnast, the Ferrari flipped over several times, leaving a trail of mechanical debris in its wake. The car finally came to rest two hundred metres down the road with one final, sickening smash onto its nose cone. The front end disintegrated on impact. It could have been made of paper machier for the protection it afforded the luckless Pironi. “An electric chair,” said Nelson Piquet in a less than subtle reference to the 126C2’s structural frailties. Ferrari didn’t like that. But Nelson had been the first on the scene, leaping out from the cockpit of his Brabham to go to the aid of his stricken colleague. Far from the ice cold machine perpetuated by certain factions of the media, other people would remember Didier as a softly spoken young man of impeccable manners and behaviour.

Didier Pironi reads "Sport-Auto " magazine by the swimming pool at his home in Saint Tropez. Photo by James Andanson/Sygma via Getty Images.

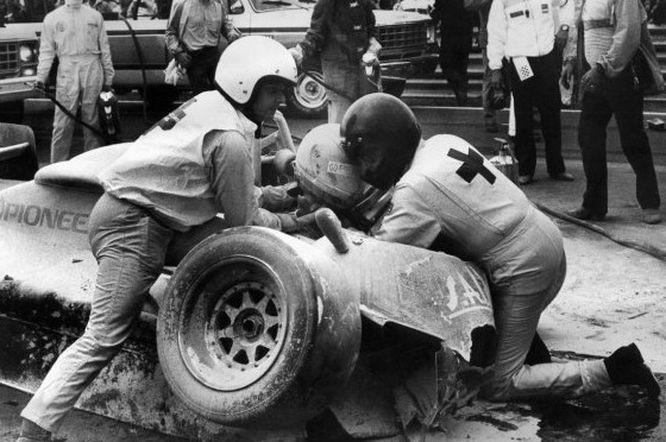

Yes, there was family money and Didier carried with him an almost palpable air of Parisien sophistication and style, but those who knew him well would talk fondly of a shy, sensitive man. His personal life would also provide endless speculation for the gossip columns right until the very end. “Get me out of here! Get me out!” Aghast Nelson Piquet surveyed the carnage before him. “Get me out!” Didier’s shrill cries pierced the gloom. Where to even begin? On removing Didier’s helmet the reigning world champion almost passed out. The Frenchman’s face was unrecognisable, bloodied and contorted with agony. On seeing the state of his shattered legs the Brazilian promptly vomited and had to be escorted away by track marshalls. Even the elements themselves seemed indifferent to the Frenchman’s plight, whose life now lay dangling by a thread. The rain intensified, bucketing down from a steely grey sky. Don’t let them take my legs! Pironi's plea to Professor Sid Watkins following crash. Thankfully the emergency services were quickly on the scene. “Don’t let them take my legs off!” screamed Didier to F1 doctor Professor Sid Watkins as he drifted in and out of consciousness. At this stage there was a real risk of amputation. Didier’s legs had both been broken, smashed to pieces, his arm was broken and his ankle was as good as crushed. “I give you my word, they won’t touch your legs,” shouted the professor having stabilised the hysterical driver. While sedating Pironi, Watkins quickly surveyed the damage. It didn’t look good. But true to his word, the Prof. ensured the circuit doctors did not carry out their threat of immediate amputation. It would take thirty agonising minutes to free the driver. Didier would later relive every second of the horrific crash over and over again. He would remember launching over the Renault, remember the pine trees and the foreboding sense of death. He would remember too how his legs started to “seriously” hurt once in the emergency helicopter en route to hospital in nearby Heidelberg. It just so happened the hospital was Germany’s leading centre for road traffic accidents. It was a small piece of fortune on an otherwise hellish day. They were a nightmarish two weeks, a never-ending cycle of anaesthetics, operations and assessments. The Heidelberg medical team performed miracles, painstakingly rebuilding his shattered legs in a series of epic operations that would last for as much as six hours at a time. Eventually Didier would be transferred to Paris under the care of Dr Letournel, the same surgeon who had dealt with the aftermath of the Jabouille and Depaillier accidents, both of whom had suffered serious leg injuries.

Alain Prost, Didier Pironi, René Arnoux and Patrick Tambay.

Over the years another forty operations would follow. There would be long, seemingly endless weeks, months spent lying in his hospital bed. Sometimes he would dream of returning to Grand Prix racing. Enzo Ferrari’s promise that a Ferrari berth would be his upon his return would cheer him up during intense periods of despair.

Didier Pironi, Enzo Ferrari and Gilles Villeneuve.

Every day he would wake to see a small trophy on his bedside table, a small token which had been sent by Mr Ferrari himself. “Didier Pironi – the true 1982 World Champion,” read the inscription. One year after his accident he re-appeared, hobbling unsteadily on crutches, 12 months of agony were deeply etched into his face despite his efforts to play down his suffering. The circuit he chose to make his return as an F1 spectator? Hockenheim… Away from prying eyes, behind the Ferrari garage doors, he lowered himself inside Arnoux's Ferrari cockpit, pressed the pedals and dreamed of the day he would return. But that's all it was — a dream as frail as his right tibia, even after 33 operations. His right ankle could not possibly withstand the rigours of a two hour Grand Prix race. Besides, his insurance policy had paid out a lot of money which would have to be re-imbursed for the sake of an attempted return he knew was doomed. And over time he gradually came to accept that perhaps his F1 career – at least as a frontrunner - was over. The Ligier test at Dijon extinguished the last lingering hopes. As a teenager he had roared around the southern Paris suburbs risking life and limb on a series of motorbikes and then cars. His brief stint in F1 had provided even greater thrills as well as fame and fortune. Didier looked around for a new way to get his kicks.

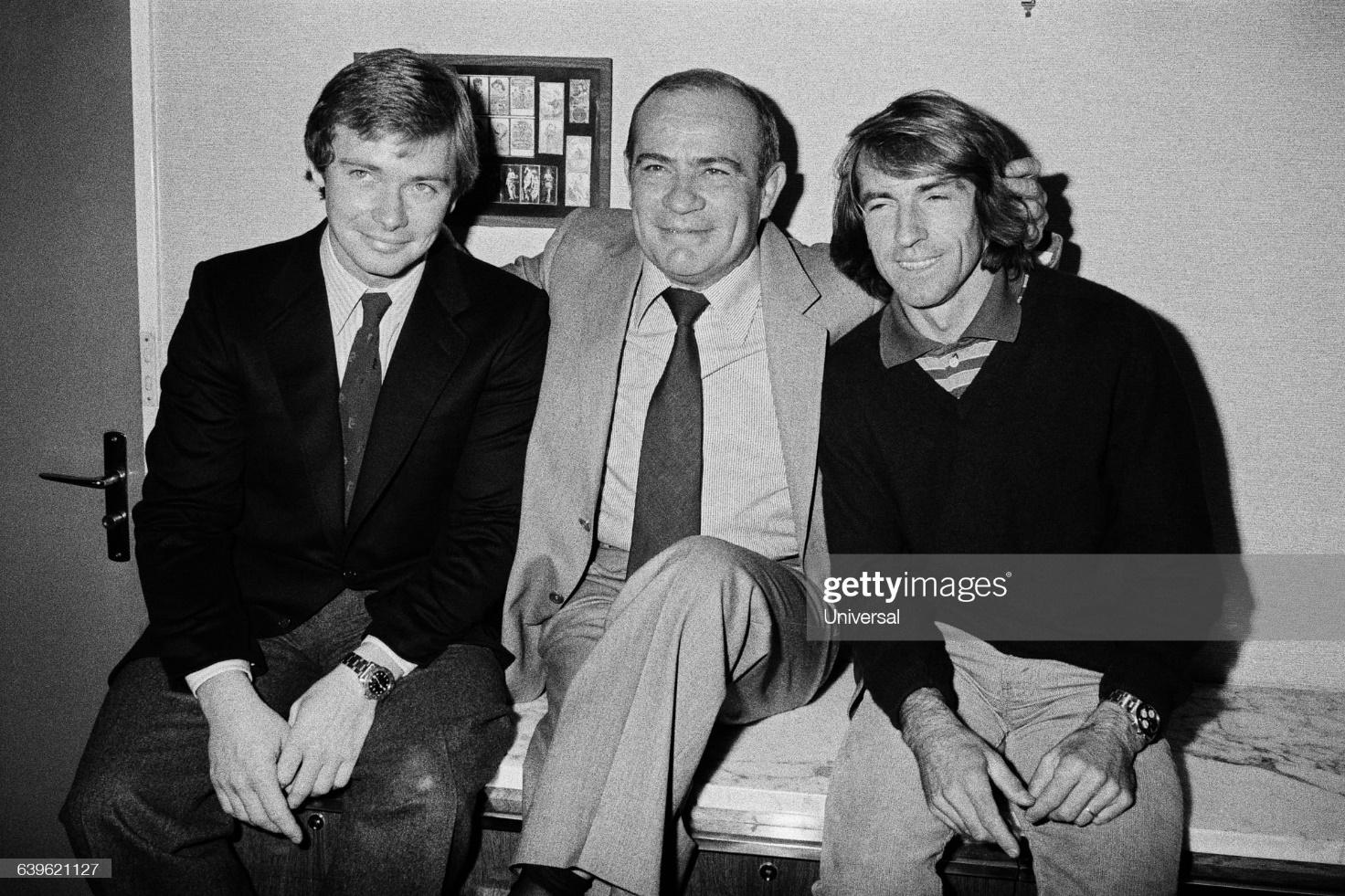

Presentation of the official Ligier Formula One team, (L-R) Didier Pironi, Guy Ligier and Jacques Laffite. Photo by UniversalCorbisVCG via Getty Images.

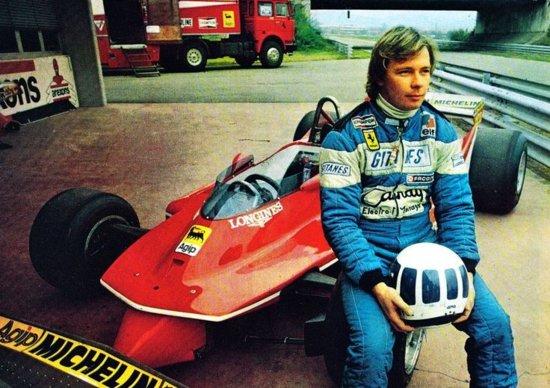

And then Colibri came into his life. “He was a very talented driver with lots of ambition. I think he felt after the Hockenheim accident powerboating was the next best thing,” said Guy Ligier, founder of the team that bore his name.

Didier Pironi in a speedboat off the coast of Saint Tropez. Photo by James Andanson/Sygma via Getty Images.

Boats had always been a part of Didier’s life and therefore it was perhaps inevitable that his attention would turn to the physically less demanding, though just as thrilling and potentially even more dangerous sport of powerboat racing.

French socialite Jacqueline Veyssière, queen of the nights of Saint-Tropez, with friends aboard a Cigarette, a boat manufactured by Leader Racing, founded by former racing driver Didier Pironi. Photo by James Andanson.

“Didier loved the atmosphere, the environment, the thrill, the excitement,” remembered friend and former Ferrari team-mate Patrick Tambay. “He loved the danger, the stress, the feeling of being able to control the anxieties that come with high-level competition.”

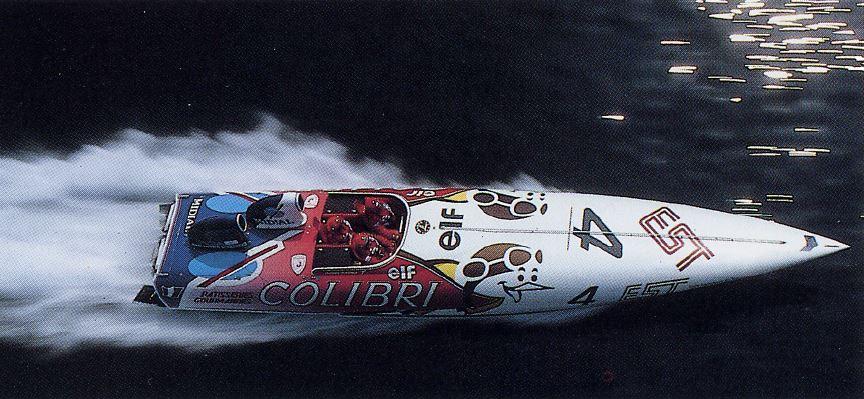

Colibri or ‘Humming bird’ was a 40 foot beast of a boat. A ground-breaking carbon fibre vessel designed for an assault on the 1987 Offshore World Powerboat Championship. Four cracked ribs from an accident in Spain though would testify to Didier just how dangerous this new sport could be. Nevertheless, along with his two man crew – Claude Guenard and Bernard Giroux, Didier took victory in Norway and was genuinely touched to receive a congratulatory message from his old boss Enzo Ferrari. He hadn’t been totally forgotten by F1. Thus he headed towards the next round at The Isle of Wight in the UK brimming with confidence. There had been occasional forays back into an F1 cockpit.

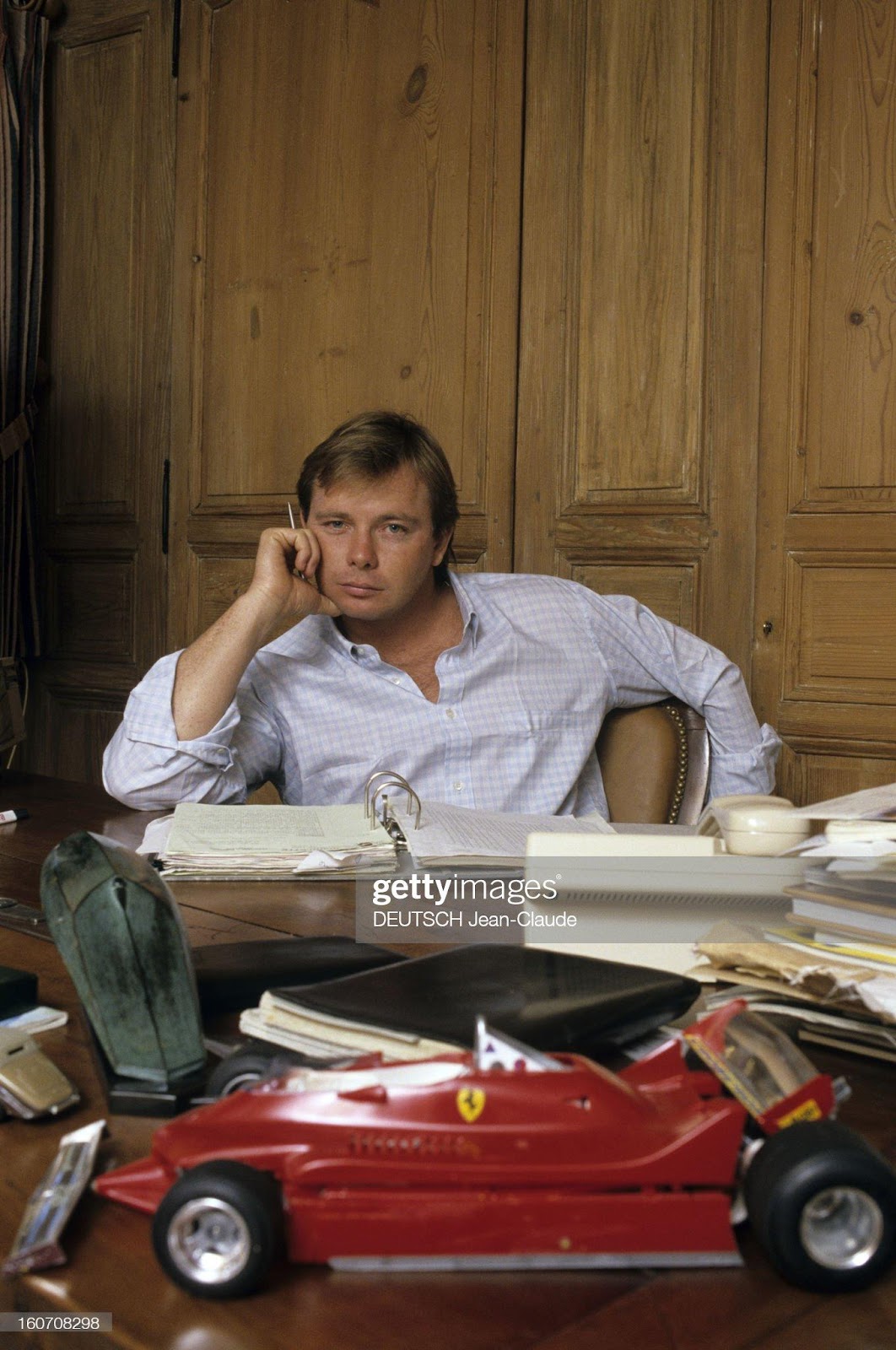

Didier Pironi at home, sitting at his desk, a miniature Ferrari car in the foreground. Photo by Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match via Getty Images.

During 1986, with the strength returning to his lower body, Didier had undertaken a serious of ‘secret’ tests for the AGS team and for his old friends at Ligier, where he had got close to Rene Arnoux’s benchmark times.

Alain Prost with Didier Pironi.

There was also an intriguing though distant prospect of a seat at Mclaren in 1987 alongside Prost. His fellow countryman though was rumoured not to be keen on the idea… As Didier prepared for the Isle of Wight race on yet another gloomy August weekend, he had in fact been about to finalise a deal for an F1 return in 1988 with the Larousse team run by his old friend ex-Renault chief Gerard Larousse. And with his partner Catherine pregnant with twins, there was plenty for Didier to look forward to that summer and beyond. A tragic end to a tragic story. Sunday 23rd August was a dull, lifeless day on the English Channel. Like that fateful day at Hockenheim five years earlier the skies were overcast. And like ’82, summer seemed to have deserted. Preparing for the race at Poole harbour Bernard Guenard had felt uneasy. Although he couldn’t explain why, the ex-Ligier mechanic didn’t feel right about the race and told friends as much. There was something in the air, something ominous. But the show had to go on. Tico Martini knew those who co-drove with Didier. "They told me they were really frightened," he says, "he just wouldn't back off, even over big waves. He would argue with his throttle guy, shouting to him 'don't shut off'.” Two laps into the 178 mile race around the island, Colibri was challenging the Italian boat for the lead. It just so happened that making its way from Southampton to Belfast that afternoon was a 100 metre long oil tanker, the Esso Avon. Fate had decreed that the tanker would be in the English Channel that particular day at that precise hour. Two hundred yards off the Needles Lighthouse, while challenging for the lead at a turning point, Colibri initially skated over the wash sent out from the nearby tanker. Didier’s fellow crew members swallowed hard. Colibri was travelling at around 100mph and, what is more, Didier showed no sign of throttling back as the boat was faced with yet more wash from the tanker. Witnesses said the boat corkscrewed high into the air, slamming upside down into the icy waters which would have effectively acted like concrete at such high speeds. RAF rescue teams were immediately despatched from the mainland, but in truth, nobody held out much hope for the occupants of the boat such had been the violence of the crash. “It comes down to luck,” said a Solent coastguard, “the others in the race got across the wake, but Didier’s boat hit it square on.” The three men were mercifully killed instantly. Didier’s cause of death was officially recorded as ‘drowning following a serious head injury.’ France wept for a sporting hero.

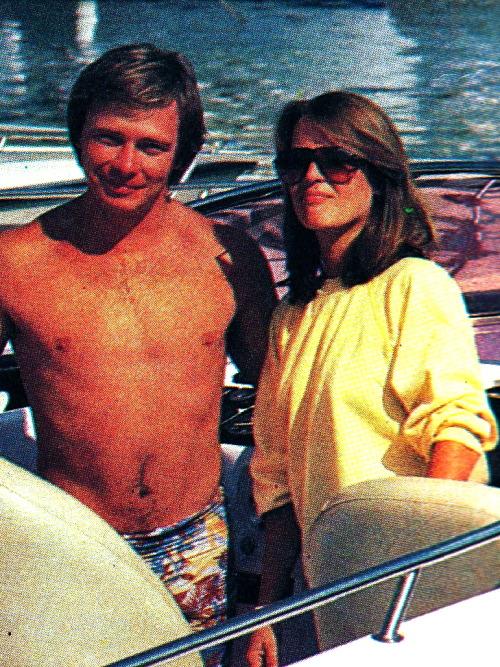

Didier and Catherine Pironi pose on a speedboat in 1981.

The former Ferrari driver left a garage full of pictures of himself and Villeneuve together and Catherine Goux, his girlfriend.

Didier Pironi with Gilles Villeneuve.

Only days before the tragedy at The Isle of Wight, Catherine had informed Didier that after three years of trying and failure upon failure of IVF treatment, he was finally going to become a father. Didier was delighted. He would rest his head upon Catherine’s stomach and addressing the unborn twins, whisper gently “how are my babies today?”

Catherine has given birth to twins in vitro. Photo by Jack Garofalo/Paris Match via Getty Images.

Twin boys would enter the world just months after their father’s untimely exit. Didier Pironi’s life had been brief yet intense.

Catherine Pironi with her children in her property of Souvigny, France, on September 12, 1988, on the occasion of the release of a book on her deceased husband. Photo by Benjamin Auger/Paris Match via Getty Images.

Old age it seemed had never had the slightest intention of adding him to its ranks. August, the holiday month, a time for enjoyment, relaxation and rejuvenation, a time for picnics on beaches and a time for new plans. Not so for Didier, for whom August truly was the cruellest of months.

Didier Pironi at Ferrari’s Fiorano test track in 1982.

The few heroes I have in motorsport, two are French, Cevert and Depaillier. But the incredible, tragic story of Didier Pironi, the F1 World champion that could have been, also deserves consideration. Pironi was an extremely pleasant, low-key, well-educated gentleman with the spirit of a tiger. An often complex, always political, character. He was a real nice guy - as they all were these days. His successful career is often forgotten. From the outside he was a man touched by the ice god, displaying cool, measured detachment which sent a shiver through those who didn't know him. But that was merely the lid over a spitting cauldron of desire so intense that in the end it devoured him. As a racing driver nature had equipped him adequately, but without the special blessings it grants the favoured few. The shortfall made little difference to a man driven by such intense ambition, directed by that icy logic. No physical barrier was going to come between him and his goal. He habitually ventured into realms of risk unusual even by the standards of a racing driver, but in a spookily deliberate and measured way. "He pushed himself harder than anyone I've ever seen," says his former team-mate Jacques Laffite. This chilling intensity, the refusal to acknowledge the limits of possibilities pre-dated Senna and the 1982 World Championship that he seemed to be heading towards could have been the first of many. But before that came to be, the laws of karma caught up with him and ended his driving career. Intelligence and drive were traits inherited from his father, a successful businessman with a construction company employing several hundred. He also inherited from him the same Parisian outlook on women both led mind-bogglingly complicated love lives. His father, though, had no interest in motorsport. That came from Didier's half-brother (on his father's side), Jose Dolhem. Eight years older than Didier, Dolhem attended the Winfield Racing School winning the Volant Shell award in 1969 and Pironi came to watch. Three years later, at 18, Pironi entered the same competition now backed by Elf and also won, guaranteeing himself a Formula Renault prize drive for 1973. Danny Hindenhoch, a former Ligier team manager, knew both brothers. "Part of Didier was very much influenced by Jose, who was a crazy guy. The pair of them ran out of fuel flying from America to Europe once and had to land in Greenland. Jose was attracted to risk and challenge and, at that young age, Didier was impressed by that." But there was a distinction between them. "Dolhem was very quick," recalls Winfield's Mike Knight, "but we were always concerned about wealthy guys like him and whether they were going to make a go of it. He was the classic lad-about-town, in too much of a hurry and not really committed. Naturally, when Didier came along we had similar concerns, but he was different. He really buckled down to it and later we came to see that this was very much in character; he'd decide to do something and that would be it. He had phenomenal grit." "He could have been President of France if he'd decided he wanted to be," adds Knight's partner Simon de la Tour. Gerard Bade was one of the finalists in the competition alongside Pironi in 72 and recalls, "he had a baby face and was from a wealthy family, so the first impression was that he wasn't to be taken too seriously. But he soon asserted himself in the car. He wasn't head and shoulders above the rest of us in the selection programme but when we went to the final phase, on the full Grand Prix track at Ricard, he coped much better than us with the stress. He was by far the most serene and mature, even though he was just 18 and most of us were in our mid-20s. He totally dominated himself and the event." Success brought yet further commitment from Pironi, never one to be without a plan. He later said: "I started with a single objective to push myself to the limit of my abilities. If, when I raced in Formula Renault, I had thought myself without the necessary qualities to be a professional driver, I would have stopped there. And no regrets." Arnoux comments: "when he decided to do something, he would progress very quickly, in a straight line. He would always find a solution."

Didier Pironi in 1978.

As a fledgling F1 driver Didier had spectacularly announced himself as a man with a future, following a heroic victory in the 1978 Le Mans 24 hour-race. It had been boys’ own stuff. He’d almost won the race single-handedly when his co-driver - veteran Jean-Pierre Jassaud - suffering from exhaustion and dehydration, had been unable to take over the car for the final stint. Didier, also suffering from exhaustion, had been obliged to soldier on, in effect putting in a double shift while fending off determined attacks from the mighty Porsche team. Exhausted and dehydrated, at race end Pironi had to be lifted from the cockpit of the triumphant Renault Alpine by a couple of gendarmes. There then followed some anxious minutes as the medical team administered oxygen. Didier eventually stumbled onto the victory podium. Huge crowds lined the Champs Elysees as the victors returned back to Paris. His attentions now turned to the F1 world crown. After his prize drive season, Pironi moved to Magny-Cours, because that was where Formula Renault constructor Martini was based. Their assistance evolved into a full partnership and Pironi won the 74 French title. He moved on to the more powerful Super Renault class, dominating the '76 season, after which Martini took him into its F2 team as number two to Arnoux. He finished third in the European championship - Arnoux won it – but, more importantly, Didier won the Monaco F3 race with a one-off appearance.

Formula 1 French Grand Prix, Paul Ricard, July 2nd, 1978. Didier Pironi and girlfriend in the pit lane, at the Tyrrell box. Photo by Hoch ZweiCorbis via Getty Images.

The move was classic Pironi evaluating what was necessary then going all-out to achieve it and it catapulted him straight into F1 with Tyrrell for 1978. Tico Martini has fond memories of the man not everyone warmed to. "Unlike some French drivers, he didn't talk a lot. But he was a very nice boy very honest and straight." Ken Tyrrell too remembers him as "a nice guy. As a driver he used to put an enormous amount of effort in. Whenever he got out the car he would be soaked in sweat. I don't think it was completely natural for him." Nice guy or not, there was some friction between driver and boss when, after he had won Le Mans with Renault, the French manufacturer tried to sign him for its '79 F1 team but Tyrrell refused to release him. "There was a period of unease," Tyrrell admits, "but when he realised it wasn't going to happen, he got stuck in again." In his first F1 season, as well as crashing a lot, he usually lagged well behind experienced team-leader Patrick Depailler. The following year's Tyrrell 009 was no great shakes but Pironi looked far more convincing in it and his form led to an invitation to join Ligier. With Gerard Ducarouge's superb JS11/15 beneath him, Pironi, confidence sky-high and with a point to prove, was awesome in 1980. He instantly out-paced team-mate Laffite and had he suffered fewer mechanical niggles, his tally would have included far more than just his start-to-finish demonstration in Belgium. "He was the toughest team-mate I ever had," said Laffite. "Better even than Keke [Rosberg], I think."

Didier Pironi, Ligier-Ford JS11/15, Grand Prix of Italy, Imola, Italy, September 14, 1980. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images.

The blue and white Ligier car was charging through the field at Brands Hatch, smashing the lap record over and over again. From behind a trademark pair of black sunglasses, the old man snorted his approval. Here was a driver with panache, a driver with swagger and an air of self-assurance that reminded the old man of champions past.

Didier Pironi, Ligier Ford JS11/15, at Grand Prix of Belgium at Zolder.

Didier Pironi, Ligier-Ford JS11/15, 1980 Belgian GP, Zolder. Source: en.espnf1.com.

Didier Pironi celebrates victory in the Belgian Grand Prix in Zolder with Guy Ligier (striped tie) and Jacques Laffite (right) with mechanics from the Ligier team. Getty Images.

Enzo Ferrari was watching the 1980 F1 season as usual on the small portable television in his office. He turned to his assistants: “I want Pironi!” And what Mr Ferrari wanted he invariably got. Within a matter of weeks Pironi had signed a two-year Ferrari deal.

Didier Pironi and Gilles Villeneuve in their Ferraris at the 1981 San Marino Grand Prix. Getty Images.

This was truly stepping into the lion's den, not only because of the usual Ferrari pressures, but because the incumbent driver, Gilles Villeneuve, was reckoned the fastest in the business.

In '81 the pair drove Mauro Forghieri's first attempt at a turbo car, the powerful but agricultural 126C and, while Villeneuve was dazzling in his virtuosity, Pironi struggled badly. It was the first real check in his career path. While Gilles Villeneuve started like a rocket playing with the brake and accelerator pedal, Pironi was often engulfed at the start.

Turbo lag led Gilles to play with the left foot on the brake and with the right one on the accelerator, Pironi drove in a traditional manner and the engine response delay was paid in terms of lap time. Gilles understood the difficulties of his colleague, who he considered a friend and opened up to him.

Pironi gave him some tips on trim setting. The pair seemed to be working well but, while Villeneuve won in Montecarlo in an incredible manner and in Spain in an authoritarian manner, Pironi was struggling.

Marco Piccinini was Ferrari's sporting director then and remembers the contrast in the two styles: "Gilles was maybe the biggest talent around and he would just invent a way of driving a corner — very spontaneous, very creative. Didier, though, would assess the risk in a very cool manner, build himself up and start the lap with the sure intention of staying flat through a corner." Off-circuit the two got on famously, though their games together sometimes had a worrying edge. One they played on the “autostrada”, for instance, saw them driving flat-out for as long as possible while the other had to sit impassive in the passenger seat, regardless of looming trucks and hard-shoulder passing manoeuvres. Of course, neither one of them ever allowed a furrow of concern to cross their brow. Though Villeneuve liked his new play-mate, his wife Joann was not so sure, wondering if he might not have a hidden agenda. Certainly, he was going out of his way to forge close alliances in the team, even away from the track.

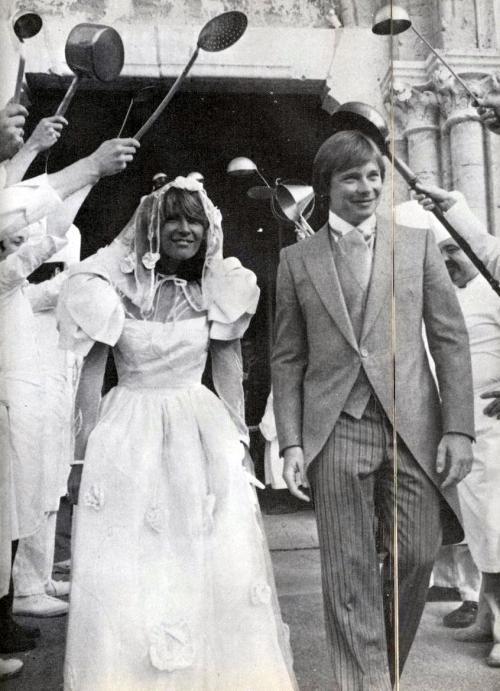

Didier and Catherine Pironi, wedding in 1982. Source: pironi.fr.

Gilles' close friend Patrick Tambay, who even then had known Pironi for a long time, comments: "it was just part of how Didier operated — he was very smart. Gilles, on the other hand, just did his stuff. Unlike Pironi, he didn't go on holiday with Piccinini or ask him to be god-father to his children or be best man at his wedding. He wasn't a political animal like Didier."

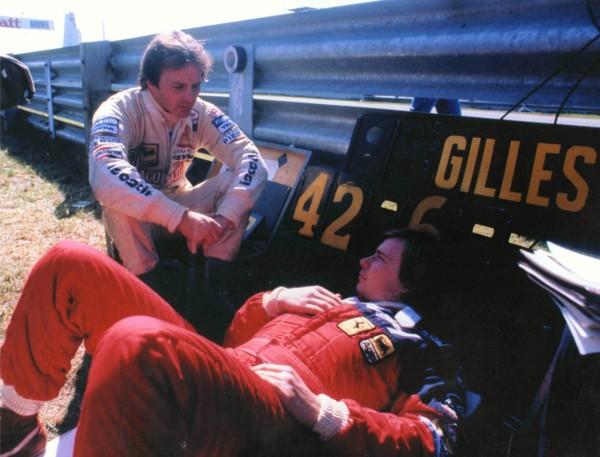

Didier Pironi and Gilles Villeneuve.

A similar picture emerges as Piccinini himself hints at Pironi's relationship with Old Man Ferrari. "Although Mr Ferrari was very close to Gilles, in some ways Didier actually had a better communication with him." Pironi himself later commented: "I'm deeply interested in politics. It's not a particularly noble area of life but it's the only thing that makes things actually happen, in motorsport as elsewhere." It all passed Gilles by. Until, of course, the infamous afternoon at Imola in '82.

Gilles Villeneuve, Didier Pironi, Ferrari 126C2, Grand Prix of Belgium, Zolder, 08 May 1982. Photo by Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images.

Didier Pironi, Ferrari, at Zolder in 1982.

For the 1982 season Ferrari took the road to return to the top and the technical staff prepared the 126 C2, the evolution of the 126, with a revised aerodynamics, efficient miniskirts and Venturi ducts, an even more powerful engine.

Didier Pironi, Ferrari 126 C2, at the 1982 Monaco GP.

1982 was announced as the year of return of Ferrari to the victory of the world title.

Didier Pironi understood that something had changed and had no desire to be a gregarious, how it happened to him in spite of himself in ’81 season.

Didier Pironi and Patrick Tambay, Ferrari 126C2, Grand Prix of France, Circuit Paul Ricard, July 25, 1982. Pironi and Tambay receiving a prize. Photo by Bernard CahierGetty Images.

Didier Pironi at the Hungarian Grand Prix in 1982.

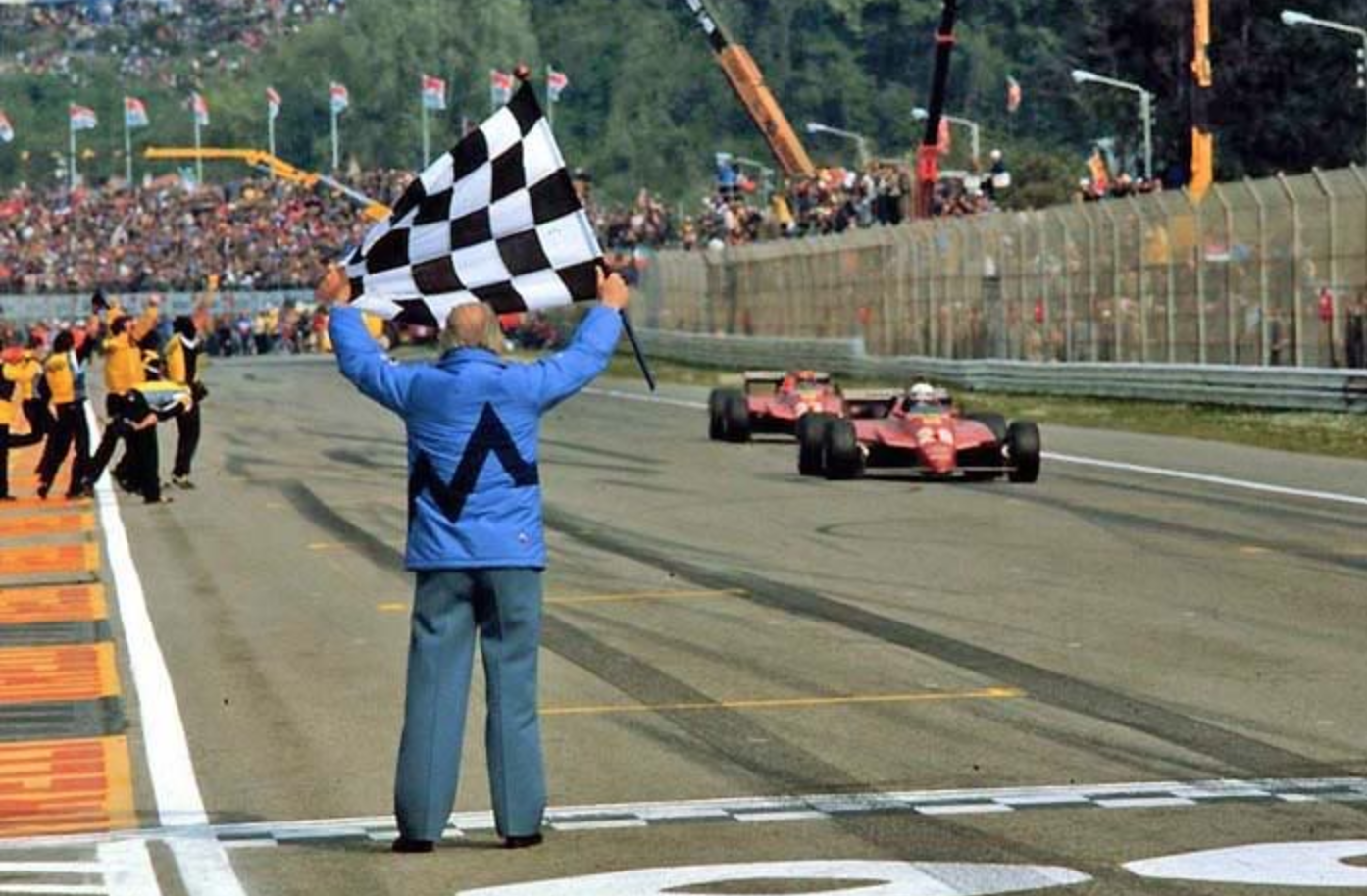

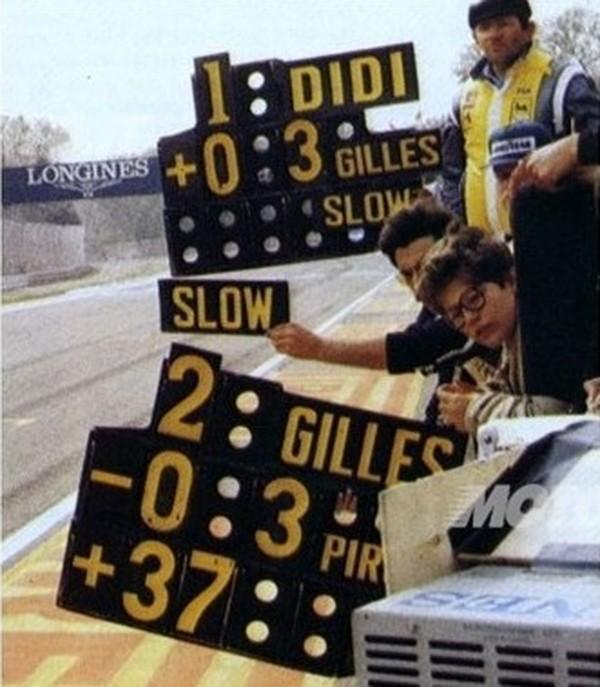

In 1982 Imola GP, the two Ferraris of Villeneuve and Pironi remained in the lead. From the pits the "slow" sign was displayed, as if to say that it is not worth taking the risk of withdrawing due to mechanical failures.

1982 Imola GP, Pironi overtakes Villeneuve.

Villeneuve obeyed, Pironi instead continued with the skirmishes: he overtook the Canadian in the Tosa curve, Gilles thought about the show and resumed the position.

Instead it was a real duel and Villeneuve understood it in the final laps, when Pironi closed the door in all the curves and prevented him from passing. Gilles understood that if he’d force his hand, the two Ferraris would have risked going off the track. What was a friend, a workmate, suddenly became a traitor to the Canadian.

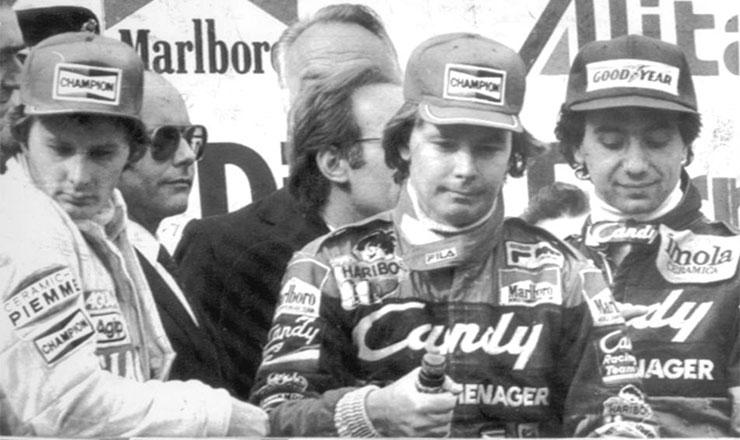

The podium of the 1982 Imola Grand Prix.

Ferrari made a double, Alboreto got on the podium, but Gilles' face did not bode well. All evidence suggested that fate tempted Pironi that day with a short-cut to his goal, but with the price tag of his integrity. Didier didn't have much time to make up his mind either — just eight laps between the Ferrari team hanging out the 'slow' sign and the end of the race. Villeneuve - ahead when the sign was shown — interpreted it as 'hold position' and assumed his victory was safe.

Pironi chose to put a different slant on the request and stole the win on the final lap from a man who, perhaps naively, wasn't even defending.

It appeared that team orders were publicly declared when the "slow" board was shown to the drivers after Arnoux had retired (on lap 45 of 60.) At that point, Villeneuve was leading from Pironi. After the race, there was initially an official comment from the team that there were no team orders, which was followed by a comment from Enzo Ferrari indicating that Pironi had misunderstood the situation.

Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi.

The incident triggered an anger in Villeneuve that was to prove fatal. He came to believe that Joann had been right all along. Gilles' last days were tormented. As well as feeling tricked, he was paranoid that Pironi was trying to take over control of the team. Two weeks later, in Belgium, the Canadian died during qualifying. Ironically, Pironi was one of the first on the scene of Villeneuve's accident. He was led away, distraught. A few days later, he was told he would not be welcome at the funeral. Ferrari withdrew Pironi's single-seater which was back in the Monte Carlo race. Didier was driven to destruction, blamed for an act of treachery that eventually led Gilles Villeneuve to crash to his death. It was said that Gilles died for wanting to make up and prove "too much". On pelouse fans were divided and to those who applauded the French driver who entered the pits, others whistled. Pironi? A cold fish! A calculating, unemotional man they said, determined to do whatever it took to become world champion, even cheat his own team-mate of a race victory. At least that’s how the largely pro-Villeneuve press lead by the French Canadian’s cheerleader Nigel Roebuck had reported events at the San Marino Grand Prix back in April. Not since Judas Iscariot had a man been so vilified. Didier shrugged off the criticism. As far as he was concerned he’d been in a race. Yet the press, with Roebuck at their helm, were baying for blood. Significantly, in the aftermath of the affair and with huge pressure to cast Didier out, Ferrari management remained equivocal. Villeneuve meanwhile raged and ranted. Enzo Ferrari himself - though ostensibly sympathising with Gilles, pointedly refused to castigate his French team-mate. But the damage had been done. Didier became public enemy number one. The minute he stole the San Marino Grand Prix from Villeneuve, his life was never the same. Partly by his own actions, Pironi had brought enormous turbulence to his life at this time. Aside from Gilles' death, there was the matter of his new bride Catherine Bleynie.

Didier Pironi and Veronique Jannot. Photo by Patrick Jarnoux / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Within weeks of his marriage he'd left her after falling in love with TV presenter Veronique Jannot.

Riccardo Paletti, Osella, at Montreal in 1982.

Then at Montreal, just three races after Zolder, Riccardo Paletti was killed after ploughing into the back of Pironi's stationary car which had stalled at the lights.

Didier Pironi, Ferrari 126C2, in 1982.

Yet, armed with Harvey Postlethwaite’s 126 C2 chassis and with the colossus of Villeneuve no longer around, his professional life was coming into full bloom.

July 3, 1982. In the Dutch GP Didier Pironi takes the 3rd and final F1 win of his career in the 126C2.

Pironi celebrating at the 1982 Dutch Grand Prix.

As well as the Imola win, he dominated the Dutch GP, scored well everywhere and was handsomely leading the championship by the time of the German GP. The late Postlethwaite later said that a strange aura had enveloped Pironi by this time — sadness but an arrogance about his forthcoming success too. "He didn't seem a very happy soul," adds Professor Sid Watkins, a man whose services he would soon need. Didier’s once promising career ended at Imola and then in the mangled remains of his Ferrari on that hateful August day.

A beautiful story if Gilles' death were not involved, because Didier Pironi was more than he seemed. He was not a bit player either as a person or as a pilot. In Formula 1 where one died he was right there. He drove a Ferrari and had a tragic fate, as befits those knights of risk. But he deserved more if only for his courage. Had seen the grass on the side of the roots Didier and was an enigma, often wearing a smile that many thought was slightly mocking. He was a relatively shy and distant person to unknown and some took this for gaelic arrogance. He very rarely showed emotion, only the colour of his skin and the amounts of sweat he worked up were a sign of the effort he put in. He was very committed. Pironi was born in 1952 in Villecresnes, a small town in the Marne valley, by Italian parents from Friuli Venezia Giulia and emigrated to France for work. When we talk about him, someone is not fond of his way of doing, he had everything, at the beginning, to get into the heart of Ferraristi, then he lost that something healthy and untouchable because the death of Villeneuve was a consequence of his way of conceiving racing. And even his subsequent accidents, three months later, seemed almost a sign of destiny. He seemed a predestined, a boy touched by good luck, he was already the pilot chosen for the Ferrari of the future and this had changed something, setting ambition above all other feelings. Authorized to do so by those who then moved around Enzo Ferrari, Marco Piccinini in the first place. Beyond the risk for the French there was life. A misunderstood and incomprehensible character. He was 35 years old. He was rich, handsome, blond, of those made to measure for the limelight, tending to fat, dissatisfied, swollen. Strong, fast. Knotted to a tragic destiny and for this reason remembered by long-time enthusiasts or only vaguely known to those born after the curtain. Intoxicated by fifty total anesthesia. Put back in place, so to speak, by thirty-four operations. Put back on his feet by a laborious restoration work he had undergone for four hours a day. He had remained with a shorter leg, but he didn't care. If there was a tennis performance to be played against Noah, he was going. Clinging to crutches. No one could understand how and why. It seemed weird that an handsome boy of good reading, an art lover (in his house many paintings, many porcelains) insisted on wanting to race, unhappy to live. Especially after Hockenheim '82.

That day Nelson Piquet stopped in front of a destroyed Ferrari on the lawn. "Pironi spoke in French, he was conscious. He asked me, in English, to get him out of the car. I tried, but he was heavy. I looked below, a gruesome scene: the legs were turned backwards, the right one at the bottom looked like mush". Pironi was "almost dead". Three months ago another boy had gone: Gilles Villeneuve. Not a bourgeois like Pironi, but a Canadian proletarian who had made his way racing with snowmobiles. Pironi had a shy smile, he got his flying licence at 17, he moved with a personal jet and as a boy he was a swimming university champion. The type of champion that goes well in the movies where you don't sweat, you don't fight and where, when you go home, there's the butler who opens the door.

Didier Pironi in a Ligier. Photo by Getty Images.

He had started racing with his own money (his father had enriched himself with constructions) and with his entourage in the Renault formula, in 1978 he had made his F1 debut with Tyrrell, in 1980 he had moved to Ligier and the following year to Ferrari. As always happens in these cases, it was thought that Didier was too "soft" to continue.

Didier Pironi and Niki Lauda.

Accidents like his and Lauda's break out but also "inside". They make you want to forget, to close with a world that by now considers you a survivor, one that will no longer be good for the track. But Pironi showed himself different. The more he suffered, the closer he got to Formula One. The more Professor Letournel tried to give him a minimum of mobility and the more he dreamed of pushing hard his right foot down the pedal. Whoever went to see him in the hospital found the Ferrari horse on his bedside table.

Catherine Pironi with Alain Delon.

His (beautiful) wife left him for a story with Alain Delon. No one had his patience and stubbornness: he didn't want to go back to live but to race. Earlier, passing near the Paul Ricard circuit, he had stopped. Not out of nostalgia but to test. Together with his cousin Josè Dohlem, he had rented two Formula 1 from a Belgian company and "did laps" on the track until exhaustion. On track he was a bad guy despite his angel face. But not an unsportsmanlike, he liked to play on the surprise effect. He didn't want glory, he wanted to win. France now remembers him as "our first driver to go close to the world title". When the rain stopped him at Hockenheim he was leading the standings with nine points ahead of Watson. Then the death in the sea of the Isle of Wight. A sort of already marked road that made that 1982 a unique year in the world scene, a year that should be told in a film worthy of Rush. So the balance contains many sadness, a weight that Pironi carried on to the end. His marriage had gone up in smoke, also shaken by gossips resulting from that accident in Germany. Catherine, his partner, gave birth to twins and thought of calling them by the names of his father and his last teammate, that Gilles Villeneuve with whom he had never had the opportunity to make peace after the "rudeness" at the Grand Prix of San Marino 1982.

Gilles and Didier, in memory of a lost friendship, of a regret to sweeten.

Pironi, Ferrari, Monaco 1981.

Pironi, Ferrari, Monaco 1981.

At the time, you could have a little doubt in your mind that Pironi would beat Villeneuve in the championship - he had the same pace and was much smarter.

Gilles Villeneuve, Ferrari 126CK, with Didier Pironi during the Spanish GP at Jarama on June 21, 1981. Photo by Ercole Colombo.

People look at 1981, when Didier was new to the team and driving that monster of a car, which was Villeneuve's "child", developed by him during 1980. With Pironi's input, they built a much better car for '82 and probably Didier realised it was a waste of time to risk his neck in the '81 car. Mind you, he was still on the pace with him in many races, even if not that spectacular as Gilles. Villeneuve was driving for the grandstand and for that he is still revered today, while Pironi drove for results.

If they had both survived 1982, there would likely be no question today as to which of the two of them were ultimately better equipped with 'the right stuff' to respond to the intensifying challenges and opportunities they each faced for the title that year.

The tragedies of that season denied us enjoying what would surely have been a sensational contest, as each one would likely have had to raise their game throughout the year. About Villeneuve this is what one of his fans said of him: “I was at the "heel of the Boot" for the first session on Friday. It had stopped raining shortly before the start of the session (as I remember). The first car on track pops over the crest of the hill and is later on the brakes than I could ever imagine. (This after seeing Gilles at Road Atlanta in his Atlantic days.) He finally found the brake pedal and the car just danced on the edge of adhesion for just a second or two before the throttle seems to go to the limits of its travel, the tail comes around and in a 45 degree power slide off Gilles goes up the hill. I stood there with my mouth agape until my attention was brought back with the sound of the next car.” I guess it is just a matter of opinion. Pironi had previously shown in the Ligier and Tyrell that he was the equal of anyone, but somewhat slightly less insane than Gilles. He also won le Mans with Jaussaud by being gentle with the fragile A442T, overwhelming the 936's through a well-run tactical race. Going 110% gets you nowhere.

Didier Pironi, 70 races in F1, 3 victories, 4 poles and a nuanced world title in the most incredible season of modern times, is the subject of a new biography by David Sedgwick, 'Pironi: the champion that never was'.

"Undoubtedly, Didier was the biggest F1 puzzle. His life was an extraordinary journey, a rollercoaster ride of triumph and tragedy," says Sedgwick. "When I started this project three years ago I had no idea how dramatic his life had been. And certainly I had no idea how much the role of destiny and coincidence had played in his life." On the day of the death of the Villecresnes champion it seemed almost as if fate had been fulfilled. Pironi has suffered the same fate of Villeneuve. But twice, at Hockenheim and at the Isle of Wight. Didier simply wanted to have back what races owed him.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment