Since 1950, a lot of characters have appeared in F1, as once it was easier: you set up a chassis and bought an engine (half the time the legendary 3 litre Ford-Cosworth) and it was done.

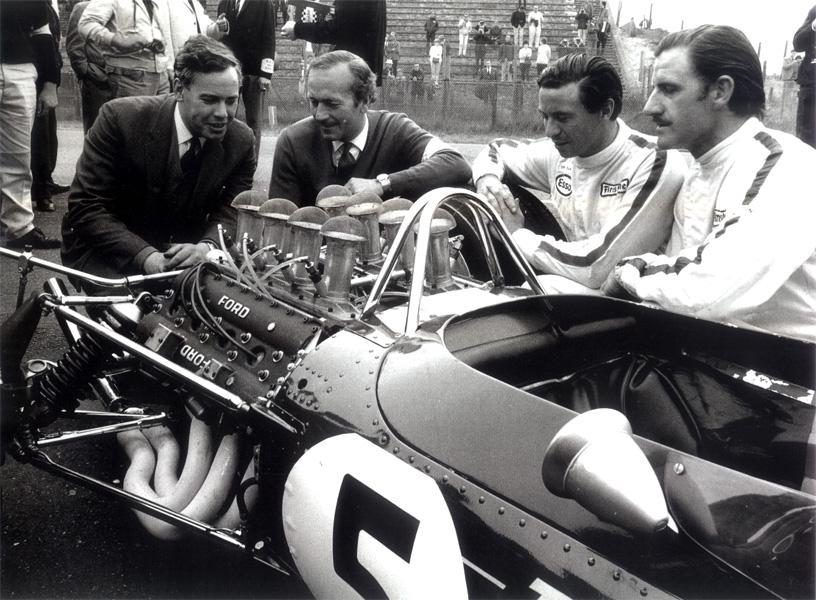

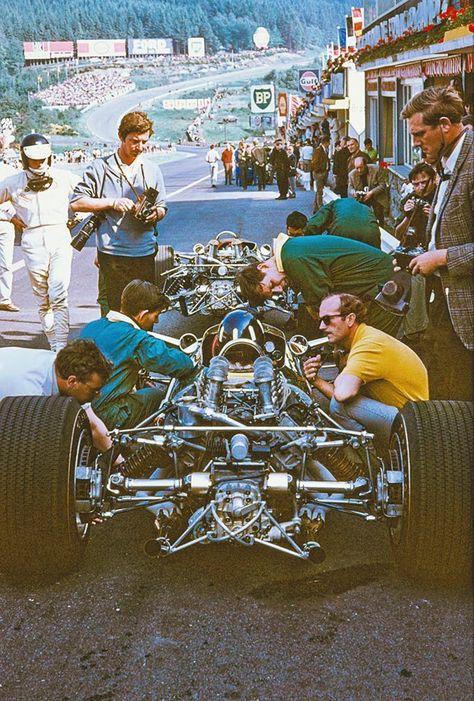

1967. At the Dutch Grand Prix, Lotus christened the Ford Cosworth F1 engine, which would dominate the highest formula for more than a decade. In this image Colin Chapman is with Keith Duckworth who, together with Mike Costin, would create Cosworth by joining their surnames Cos-Worth.

Enzo Ferrari has labeled the new independent “designers garagistes”, the men who cannot build engines. Those garagistes caused him a lot of pain indeed.

As Chapman’s Lotus that won 7 world championships. The English “garagiste” has designed the most beautiful, elegant, refined, glamorous F1 cars ever. So light and fragile they were the purest ode to speed. Sublime inventor, made historic innovations that have reverted car’s world. Constantly ahead of his time, designed and developed personally his inventions.

You could say that he was the inventor of the modern Formula 1.

Unsurpassed genius, his prestige was lower only than the one of Enzo Ferrari, who described him as “brilliant in his cutting-edge insight”.

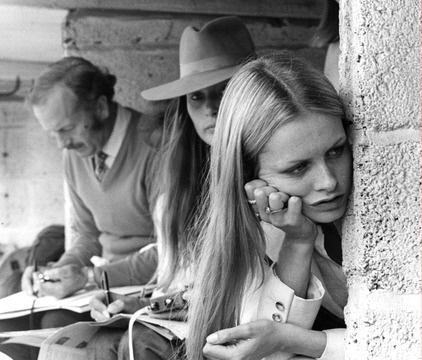

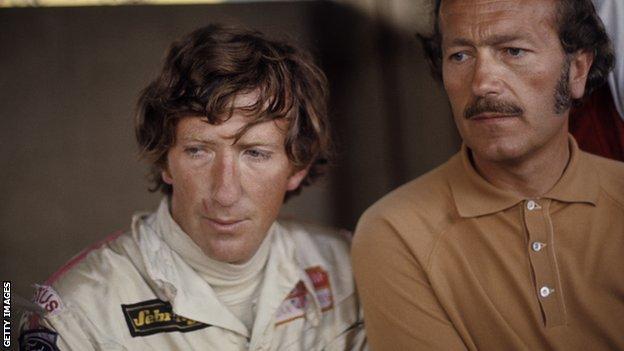

Colin Chapman and Barbro Peterson.

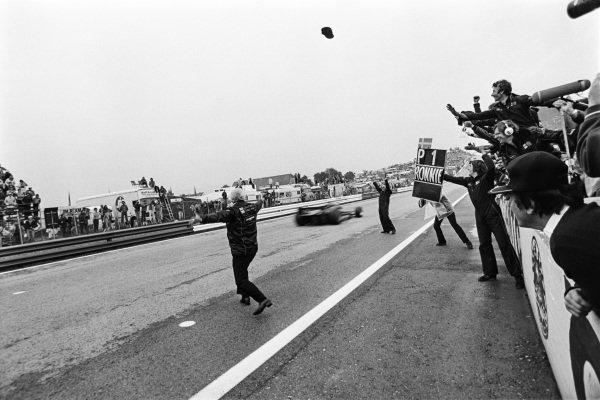

When he died, Chapman rapidly left a world that got used to see him tossing his black beret with every victory of his creatures.

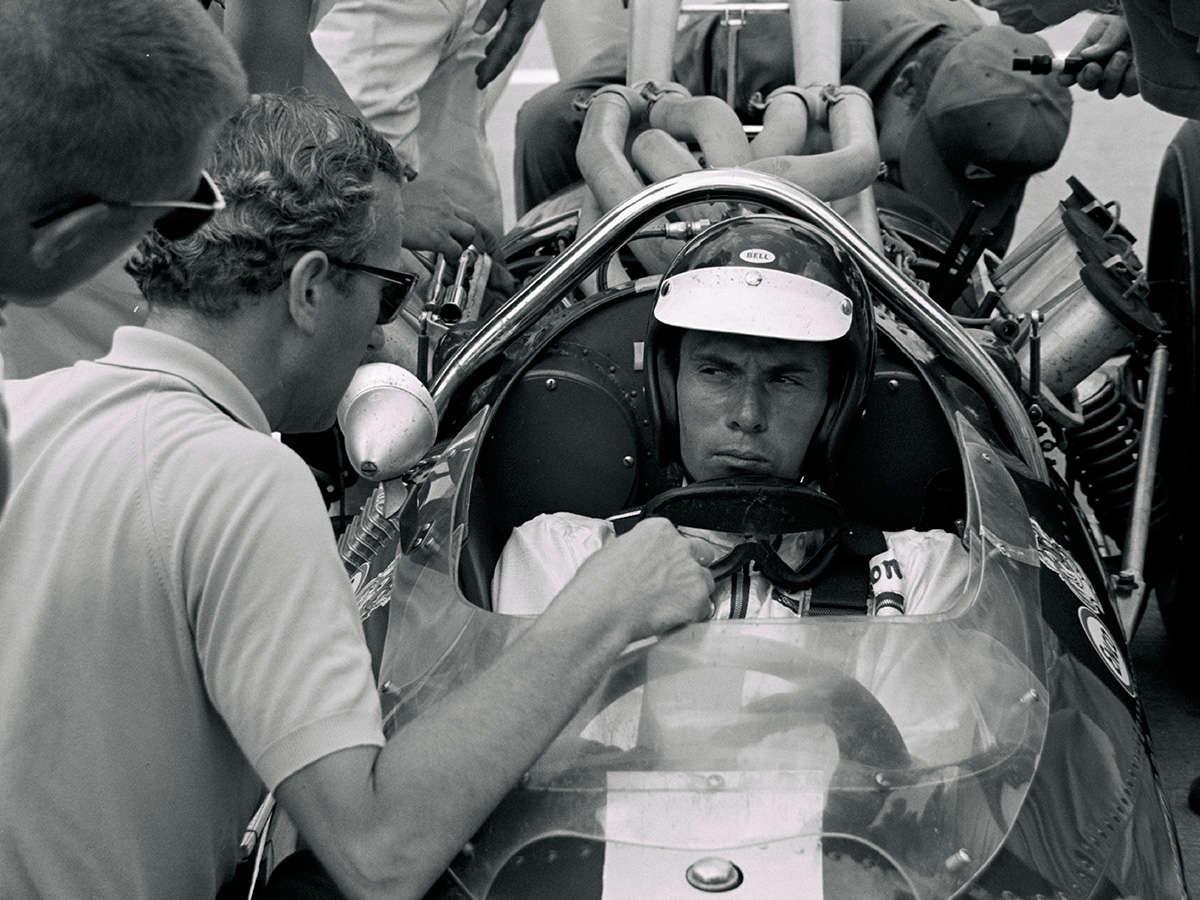

A young Colin Chapman.

If ever an automotive magnate combined the attributes of genius and cowboy it was Colin Chapman. A dazzlingly original thinker, he completely changed the rules for road cars and racing cars with his Lotus brand, following an ethos of "simplify, then add lightness" and demonstrating one stunning innovation after another. Chapman's insatiable quest for light weight, innovation and victory and, at times, money to continue racing, meant he produced some appallingly under-engineered and/or frail racing cars. These often broke, sometimes tragically. He’s mostly remembered as the man who brought unprecedented flair to British motor racing through Lotus, the company he founded in a workshop attached to his father's pub. He had the most amazing, restless mind and he turned it to all sorts of problems. There was nothing that he felt was beyond him. According to Mike Lawrence's 2002 biography, Chapman's huge energy was enhanced by generous handfuls of amphetamines and barbiturates. That, and the stress of the net tightening around the bankrupted DeLorean company, may have contributed to his death at just 54. Son of a hotel manager, Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman (19 May 1928 – 16 December 1982) was an influential English design engineer, inventor and builder in the automotive industry.

In 1952 he founded the sports car company Lotus Cars witch he initially ran in his spare time, assisted by a group of enthusiasts. His knowledge of the latest aeronautical engineering techniques would prove vital towards achieving the major automotive technical advances he is remembered for. His design philosophy focused on cars with light weight and fine handling instead of bulking up on horsepower and spring rates, which he famously summarised as "adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere".

Under his direction, Team Lotus won seven Formula One Constructors' titles, six Drivers' Championships and the Indianapolis 500 in the United States, between 1962 and 1978.

Colin Chapman on 20 July, 1965. Photo by Evers, Joost/Anefo.

The production side of Lotus Cars has built tens of thousands of relatively affordable, cutting edge sports cars.

Lotus is one of but a handful of English performance car builders still in business after the industrial decline of the 1970s. Besides his engineering work, he also piloted a Vanwall F1-car in 1956 but crashed into his teammate Mike Hawthorn during practice for the French Grand Prix at Reims, ending his career as a race driver and focusing him on the technical side. Along with John Cooper, he revolutionised the premier motor sport. Their small, lightweight mid-engined vehicles gave away much in terms of power, but superior handling meant their competing cars often beat the all-conquering front engined Ferraris and Maseratis. Eventually, with driver Jim Clark at the wheel of his race cars, Team Lotus appeared as though they could win whenever they pleased. Clark and Colin became particularly close and Clark's death in 1968 devastated Chapman, who publicly stated that he had lost his best friend. Among a number of automotive figures who have been Lotus employees over the years were Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth, founders of Cosworth. Graham Hill worked at Lotus as a mechanic as a means of earning drives. Chapman, whose father was a successful publican, was also a businessman who introduced major advertising sponsorship into auto racing; beginning the process which transformed Formula One from a pastime of rich gentlemen to a multi-million pound high technology enterprise. It was Chapman who in 1966 persuaded the Ford Motor Company to sponsor Cosworth's development of what would become the DFV race engine.

Lotus founder Colin Chapman and his wife Hazel during practice for the Monaco Grand Prix in 1964.

Many of Chapman's ideas can still be seen in Formula One and other top-level motor sport (such as Indy Cars) today. He pioneered the use of struts as a rear suspension device. Chapman's next major innovation was popularising monocoque chassis construction within automobile racing, with the revolutionary 1962 Lotus 25 Formula One car.

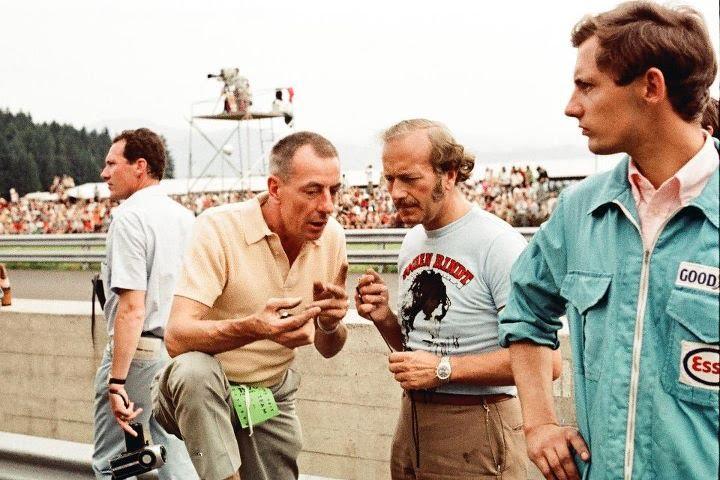

Ron Tauranac, Colin Chapman and a young Ron Dennis.

The technique resulted in a body that was both lighter and stronger, and also provided better driver protection in the event of a crash. This design concept fairly quickly replaced what had been for many decades the standard design formula in racing-cars, the tube-frame chassis. Although the material has changed from sheet aluminium to carbon fibre, this remains today the standard technique for building top-level racing cars.

Colin Chapman with Ronnie Peterson, March.

Inspired by Jim Hall, Chapman was among those who helped introduce aerodynamics into Formula One car design. Chapman also originated the movement of radiators away from the front of the car to the sides, to decrease frontal area (lowering aerodynamic drag) and centralising weight distribution.

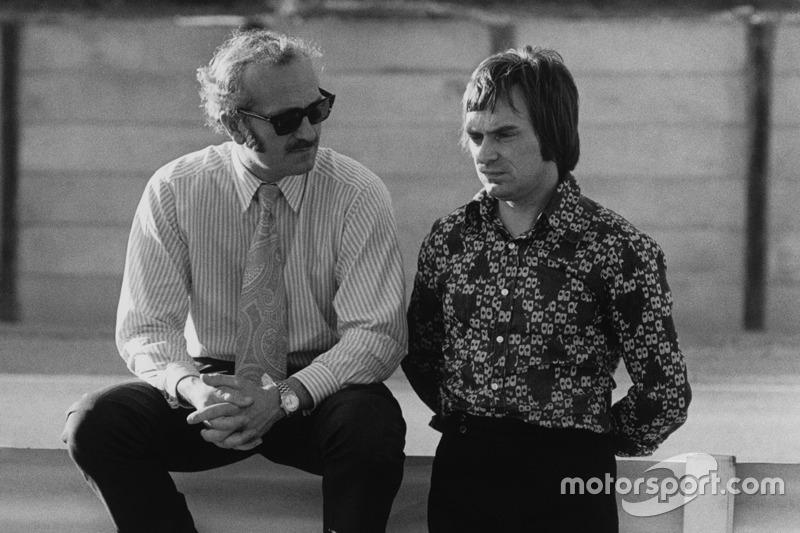

Colin Chapman and Emerson Fittipaldi in 1972.

“I learned a lot from Colin Chapman, especially from the technical aspect. He taught me what a car is like, what are the physical laws that act on a car. Colin was a genius. It happened that on Fridays the car was undriveable, a real rubbish. Colin would take me to dinner, let me tell him in the smallest detail what happened during a lap, then, at night, he went back to the garage. He got to work with the mechanics and the next day the car flew. He had an almost mystical mechanical sensitivity. As a team manager, however, he was totally disorganized. He didn't have the slightest strategy, he didn't plan anything, he lived for the day. Chapman woke up, ate lunch and ate cars, in his mind there was always and only the technical aspect. He had a perpetual appetite for suspensions and aerodynamics. Sometimes I thought that he was even making love with cars. It was an unbridled passion that bordered on mania. Yes, his love for cars was manic.” Emerson Fittipaldi

These concepts remain features of virtually all high performance racing cars today. Chapman was also an innovator in the business end of racing.

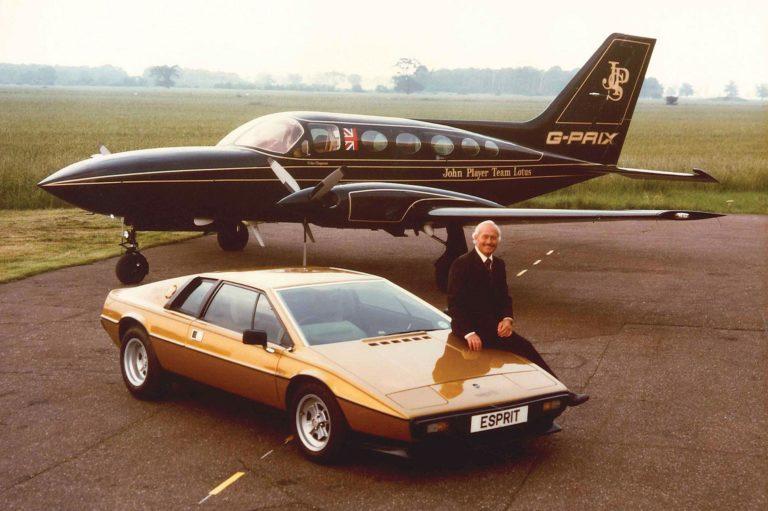

Lotus Founder and designer Colin Chapman with his Lotus Esprit and liveried personal plane. r/formula1

He was among the first entrants in Formula One to turn their cars into rolling billboards for non-automotive products, initially with the cigarette brands Gold Leaf and, most famously, John Player Special. Chapman, working with Tony Rudd and Peter Wright, pioneered the first Formula One use of "ground effect", where a low pressure was created under the car by use of Venturis, generating suction (downforce) which held it securely to the road whilst cornering. Early designs utilized sliding "skirts" which made contact with the ground to keep the area of low pressure isolated. Chapman's next planned a car that generated all of its downforce through ground effect, eliminating the need for wings and the resulting drag that reduces a car's speed.

"My Williams FW06 had two problems, one with driveability, the other was Colin Chapman's Lotus 'Wing Car'." Patrick Head

The culmination of his efforts, the Lotus 79, dominated the 1978 championship. However, skirts were eventually banned, because the skirt could be damaged, for example, from driving over a kerb, and downforce would be lost and the car could then become unstable.

Colin Chapman with Nigel Mansell. Getty Images.

1983 John Player Special Lotus 93T. In the car Elio De Angelis with n.2 driver Nigel Mansell, Hazel Chapman and 2 daughters and son.

Hazel Chapman. Without her there would be no Lotus.

The FIA made moves to eliminate ground effect in Formula One, by requiring flat bottom cars from 1983 and raising the minimum ride height of the cars from 1981.

Car designers have managed to get back much of that downforce through other means, aided by extensive wind tunnel testing. One of his last major technical innovations was a dual-chassis Formula One car, the Lotus 88 in 1981. Although the car passed scrutineering at a couple of races, other teams protested, and it was never allowed to race. The car was never developed further. The Genius of Colin Chapman: "simplify, then add lightness”. His nickname might have been ‘Chunky’ (only ever behind his back, mind…) but there was nothing overweight about Chapman’s Lotus racing cars... The Londoner is probably best known for what many consider to be the world’s first ever stressed monocoque racing car, the Lotus 25. The simplicity of the classic, cigar-shaped racing car is staggering and the principle (now in carbonfibre, rather than aluminium) is still used today. Chapman’s mid-engined single-seaters (after fellow British garagiste John Cooper had led the way) transformed Grand Prix racing at the turn of the decade from the 50s to the 60s. Fast but fragile cars. Big accidents suffered by Stirling Moss, Alan Stacey and Mike Taylor showed the other side of Chapman’s ‘as-long-as-it-crosses-the-line’ philosophy. The immediate predecessors to the Type 25 were tubular framed, with heavily braced joints and separate bodywork attached by Dzus fasteners and pins. Gradually, as aluminium sheet was used more and more to reinforce the chassis, and pinning the bodywork to the chassis was found to enhance its stiffness yet further, Chapman came to the conclusion that an entire chassis/body structure in aluminium sheet would allow the tubular chassis and most of the bodywork to be done away with altogether. The monocoque was born. In addition, Chapman introduced big money sponsorship to the sport. Not only did the cars look like ‘cigar tubes’, they were painted like them, too.

Colin Chapman. Photograph by Mike Flynn.

Chapman grew up in Hornsey and studied mechanical engineering at University College, London. He was an enthusiastic member of the University Air Squadron and learned to fly while still a student. He then did his national service as a Royal Air Force pilot in 1948. After he left the RAF Chapman bought and sold second hand cars while becoming a member of the 750 Motor Club, which was the nursery for many of the top F1 engineers of the 1960s and 1970s. In 1952 his girlfriend Hazel Williams lent him 25 pounds to establish the Lotus Engineering Company with Michael Allen, with the aim of building copies of his racing machines. In 1953 Frank Costin joined the company from De Havilland and the Lotus Mk 8 enjoyed some success. This enabled Chapman to quit BAC and concentrate full-time on Lotus, producing racing cars and road going machines in workshops which had been set up in old stables behind the Railway Hotel in Hornsey, where his father was the manager. Having achieved little in 1958 and 1959 Chapman switched to rear-engined cars in 1960 with the Lotus 18. By then the company had expanded to such an extent that it had to move to new premises in Cheshunt. The first victory in a Lotus car came at Monaco in 1960 when Stirling Moss beat the dominant Ferrari team in his Rob Walker Lotus. For the new 3-liter Formula 1 in 1966 Chapman chose BRM engines (a mistake) but the arrival of the Cosworth DFV in 1967 returned the team to winning ways. The company had moved from Cheshunt to Ketteringham Hall in Norfolk in 1966 and continued to do well financially as the demand for sports cars in the 1960s seemed to be endless. Many of Chapman's successes came from innovation. The Lotus 25 was the first monocoque chassis in F1, the 49 was the first car of note to use the engine as a stressed member and the 72 broke new ground in aerodynamics.

Colin Chapman with Mario Andretti, random punter, Ronnie Peterson and interesting belt.

Colin Chapman with Mario Andretti.

Colin Chapman and Mario Andretti.

Colin Chapman inspects the back of Andretti’s Lotus 79/R3 Ford Cosworth DFV.

Chapman was also an innovator as a team boss and it was Team Lotus which first introduced commercial sponsorship to F1 at Monaco in 1968.

Ronnie Peterson and Lotus in 1978.

In the mid-1970s, however, Lotus engineers began to investigate aerodynamic ground-effect and the Lotus 79 of 1978 was extraordinarily successful with Mario Andretti winning the World Championship.

Colin Chapman, Formula 1 Lotus day, 1981.

There had been a feeling within the team that boats and planes were sidetracking a Chapman disaffected by the interminable shenanigans of F1. In April 1981, he released the following press statement: “I shall seriously reconsider… whether Grand Prix racing is still what it purports to be: the pinnacle of sport and technological achievement. Unfortunately, this appears to be no longer the case and, if one does not clean it up, Formula 1 shall end up in a quagmire of plagiarism, chicanery and petty rule interpretation forced by lobbies manipulated by people for whom the sport has no meaning.” He looked older. The toll exacted by a hectic life of all-nighters and no tea breaks insidiously ran deeper than his receding line of ghostly hair. In 1982 Colin was beginning work on an active-suspension development program. The night before he died, Chapman was watching a performance by his long-time friend and Lotus customer Chris Barber, the noted jazz trombonist and his band. On 16 December 1982, Team Lotus were testing the first Formula One car with active suspension, which eventually made its début with the Lotus 99T in 1987. Chapman suffered a fatal heart attack on the same day at his home in Norwich and died aged 54.

Hazel Chapman, widow of Lotus car chief Colin Chapman, carrying a single red rose at his funeral. Shutterstock.

It was probably fortunate that he died when he did and thus avoided the scandal which was later revealed about Lotus's involvement with the DeLorean car company. A judge later remarked that if Chapman had been alive he would have been sent to jail for 10 years for an "outrageous and massive fraud". The glory years of Team Lotus were over. In any case, the technical rules were now becoming so tight that the age of true innovation was ending.

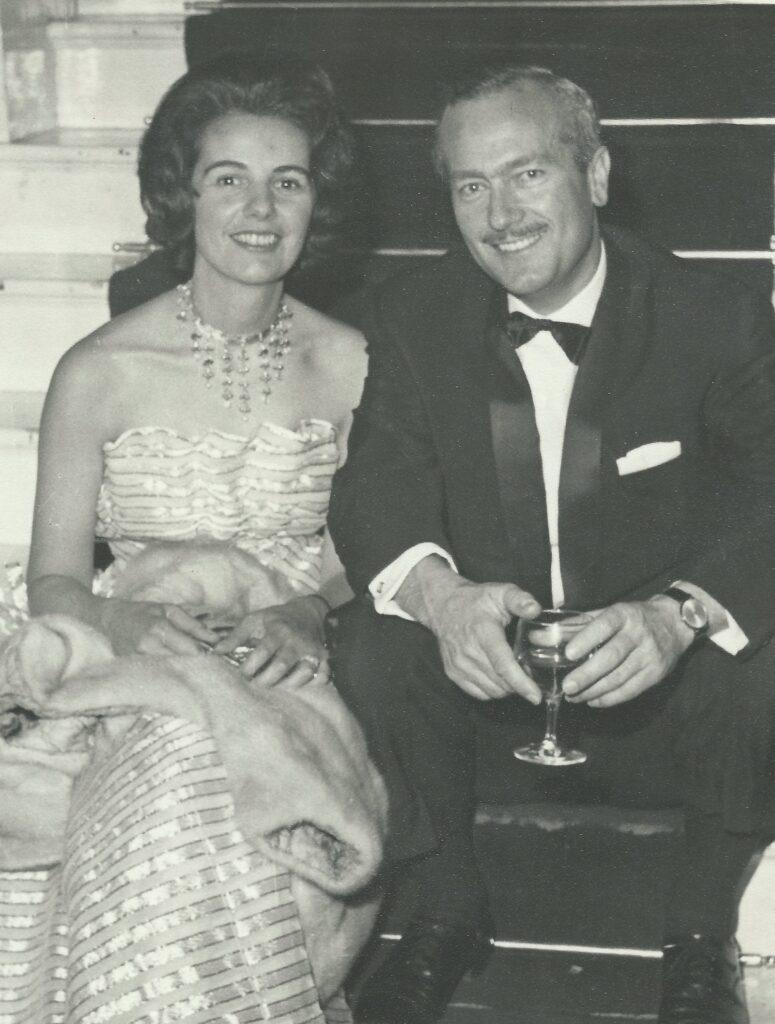

Colin Chapman and wife. Shutterstock.

Hazel Chapman with Colin Chapman. Copyright: The Colin Chapman Foundation.

July 07, 1965. Colin Chapman flies home.

Chapman was married to Hazel. He has two daughters and one son.

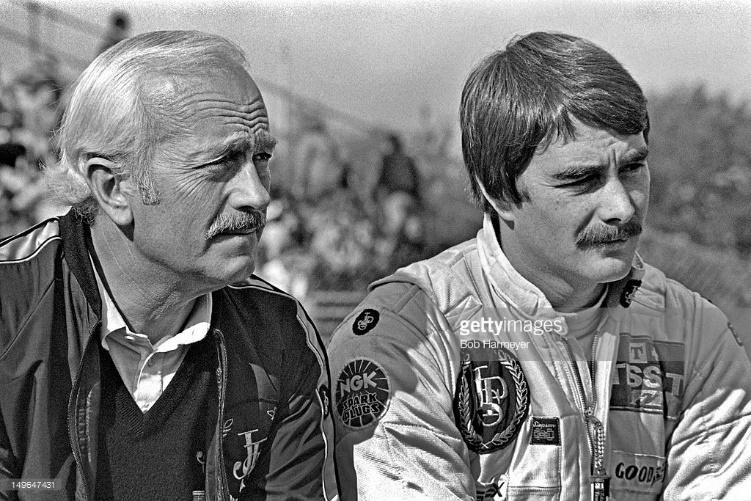

F1 South African Grand Prix 1972. Colin Chapman with Bernie Ecclestone, Brabham.

Q: Who else in F1 has had a larger than life personality like Bernie that you’ve worked with?

Mario Andretti: Enzo Ferrari. Colin Chapman. These are individuals that were bigger than life, then and now.

Q: Tell me about Colin Chapman.

MA: Colin had the reputation he had because he wanted to give the driver every possible advantage, and he knew that weight was the issue. He was adamant about weight. Many times it crossed over and it cost the drivers, and I knew that. But I was not shy about making certain demands, I had an incredibly good relationship with his mechanics. Like Bob Dance. I said to Bob, if you see anything in your own mind that Colin is trying to do that is just a little too radical, or a little too over the limit, please let me know. I told him I like to be reasonable, so I felt like I had a security blanket in that area away from some of Colin’s more out-there ideas. But I was always looking at Colin, there was a confidence aspect that he was doing everything possible to get you a winning car. He was a maverick for sure, but that’s what drove him. He was never one to sit on his laurels, he would get bored with the status quo. He was very creative, very moody. You had to be with him at just the right time, which I was, because he had peaks and valleys in his own career because he was always trying to play outside the box, which sometimes didn’t work because he was too radical. But when he was right on, he was right on. And I enjoyed that part of it obviously, and took advantage of that by bringing home a world championship for Lotus.

Jim Clark and Colin Chapman had a language all their own. Together, they changed racing forever.

Colin Chapman and Jim Clark.

Jim Clark watching Graham Hill, on Lotus 49, consulting Colin Chapman.

Jim Clark was a natural, perhaps the finest pure driver to ever grace F1. There's no way of knowing where his skill came from; strangely for a racer, he rarely drove at the limit, always holding something in reserve. His style was pre-polished, almost, and evolved into the same mirror-shine as the aluminium skin of his racing machines. After bringing Clark on board, Chapman stopped racing. Maybe he realized that he'd finally found a talent worth building cars around. Even when the cars weren't right, Clark's abilities let him make up for deficiencies. It was all a dance of wrists and elbows, grace under pressure. The few times he really pushed hard, it was because he thought he'd made an error; Colin Chapman would say of James Clark, after his untimely death: “He will always be the best. I’m sure in time someone else will come along and everyone’ll hail him as the greatest ever. But not me. For me, there will never be another in Jimmy’s class.” The design genius behind Lotus, Colin Chapman was a man obsessed with making his cars ever faster and lighter.

Colin Chapman and his Lotus 1.

Graham Hill, pictured in the centre, with Colin Chapman, c1967-c1970. Stock Photo, Picture And Rights Managed Image.

His innovations often brought glory on the track – with legendary drivers including Graham Hill, Jim Clark and Mario Andretti securing World Championships in a Lotus. A man obsessed with making his cars ever faster and lighter. But this relentless pursuit of speed also proved deadly, with many criticising the cars as unstable.

Colin Chapman wrote: 1. A racing car has only ONE objective: to WIN motor races. If it does not do this it is nothing but a waste of time, money, and effort.

This may sound obvious but remember it does not matter how clever it is, or how inexpensive, or how easy to maintain, or even how safe, if it does not consistently win it is NOTHING!

2. Having established this what do we have to do to make it win:

(i) Simply stated it must firstly be capable of lapping a racing circuit quicker than any other car, with the least possible skill from the driver, and doing it long enough to finish the race.

(ii) After this, and only after this, and with absolutely no compromising of objective (2)(i) one has to consider how expensive it is, how simple, how safe, & how easy to maintain, etc. NONE of these aspects must detract one iota from (2)(i). “Good enough” is just NOT good enough to win and keep winning.

Rindt, pictured at Monza the day before his death, with Lotus owner Colin Chapman.

Six years before he wrote this, Chapman received a letter from his driver Jochen Rindt after a wing failure caused Rindt’s Lotus 49 to crash heavily in Barcelona: “honestly your cars are so quick that we would still be competitive with a few extra pounds used to make the weakest parts stronger … I can only drive a car in which I have some confidence, and I feel the point of no confidence is quite near”. Rindt remained with the team in what turned out to be a Faustian bargain. The car he got from Chapman for the 1970 season had nothing about simplicity, ease of maintenance or safety to detract one iota from objective (2)(i). It gave Rindt the world championship and it took away his life.

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment