These are 5 of Ayrton Senna's best laps. No driver in the modern era could quite 'get in the zone' like him. On occasion, Senna spoke of his 'tunnel.' It was a trance-like state wherein he could out-drive not only the likes of Mansell, Prost, and Piquet, but his own limitations. That was part of Senna's mystique. In those instances when he'd find the tunnel, he was absolutely untouchable. This isn't a definitive list of the three-time F1 Champion's greatest laps. Rather, it's 1- and 2-minute-long exhibitions of Senna's hyper-state, that hypnosis he sometimes talked about finding behind the wheel.

"Crash" (1988 Monte Carlo Grand Prix) How great can a lap be when the driver crashes midway through it? Senna describes his pseudo-religious moment lapping the grid at Monaco. Wrecking was a watershed moment for the Brazilian, who bounced back to win his first Driver's Championship.

"Eighth to Third" (1993 Canadian Grand Prix) Qualifying order held Senna up behind both drivers from Williams, Benetton, and Ferrari, as well as Brundle's Ligier-Renault, on the grid. In an inferior McLaren, Senna simply willed himself up four spots in the opening lap and into third place within just 2 minutes, 30 seconds.

The Grand Prix in Monaco, 1937.

"The Hold" (1992 Monte Carlo Grand Prix) Thrilling as he was dissecting traffic, Senna could just as easily get in the zone while defending. Having run the entire race on a single set of slicks, Senna fended off a much faster Nigel Mansell (who was on fresh tires) for several minutes, culminating in a thrilling final lap where the duo was separated by just 0.2 seconds.

"The Wet Lap" (1993 European Grand Prix) When it rained, Senna shined. In fifth place entering Redgate at a rain-soaked Donington Circuit, he passed Schumacher, Wendlinger, Hill, and Prost — a group representing 12 collective driver's titles — on the first lap alone. Senna went on to easily win the race.

"Perfection" (1989 Japanese Grand Prix) Qualifying before Suzuka, Senna handily out-drove his teammate, securing pole position with a record time of 1 minute, 38 seconds (some 1.7 seconds faster than the Frenchman). The closest thing to a genuinely perfect lap we've ever seen.

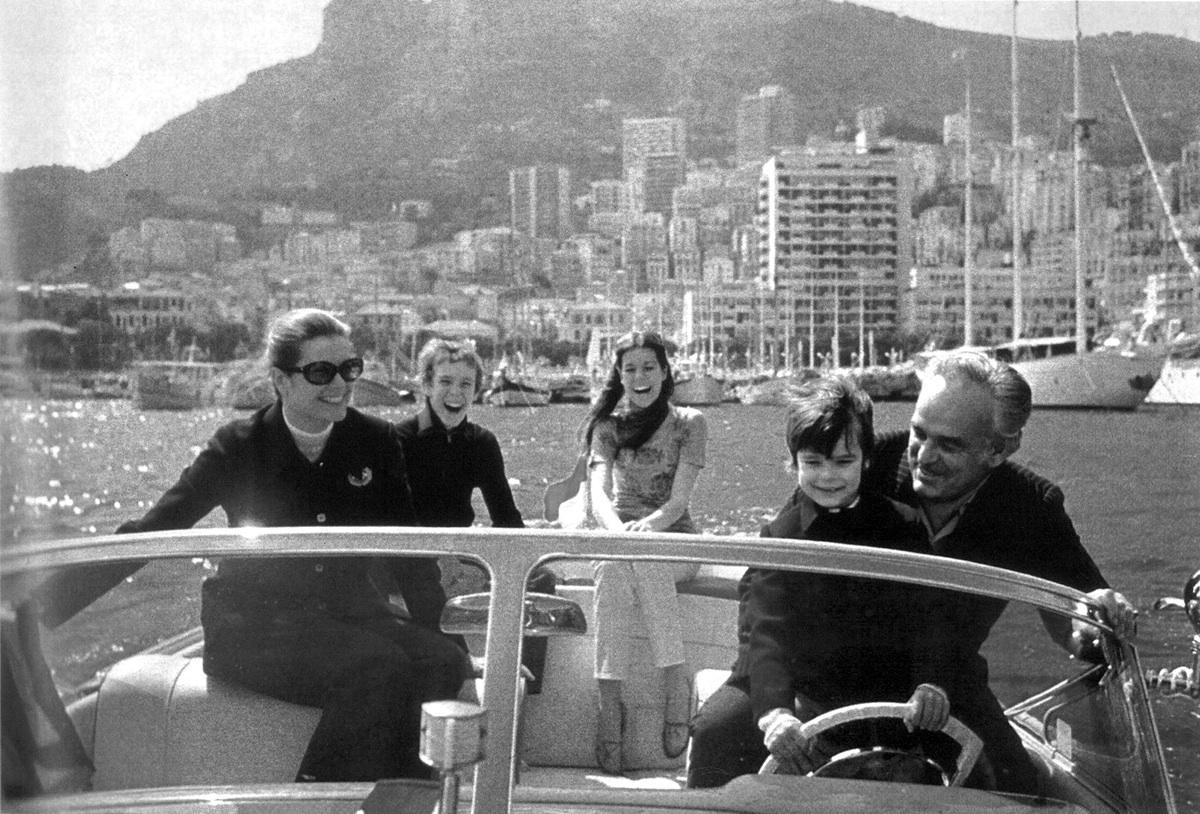

Prince Ranieri of Monaco and his family.

Senna chose his legendary Monaco 88 qualifying lap himself as the greatest ever.

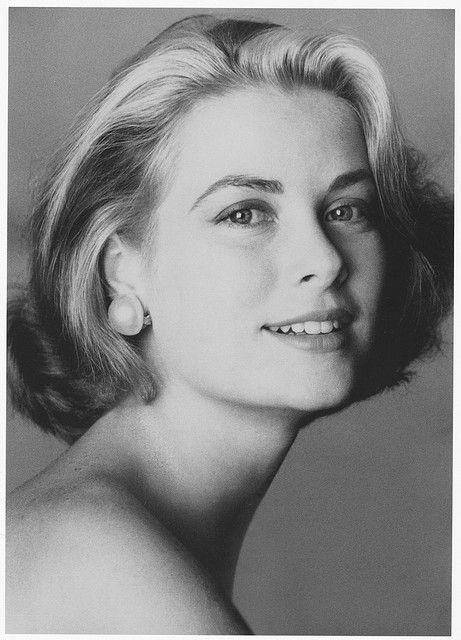

Grace Kelly in 1954. By Irving Penn.

Almost unbelievably, the lap was never actually caught on camera. It's widely regarded as one of the greatest laps ever seen in the history of F1. Senna himself said: "that was the maximum for me; no room for anything more. I never really reached that feeling again." He went out-of-body.

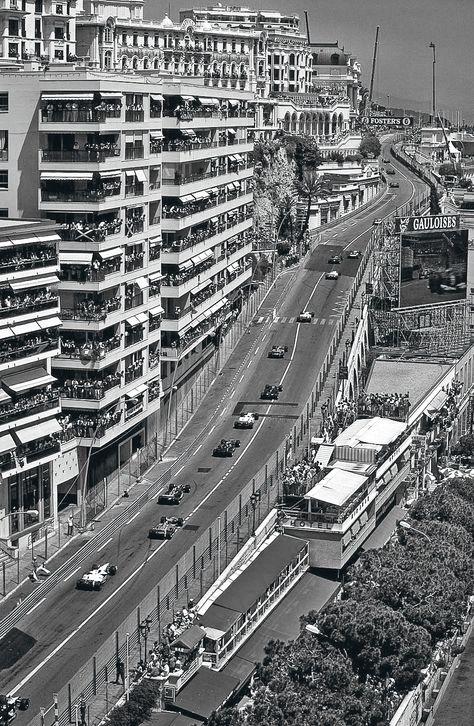

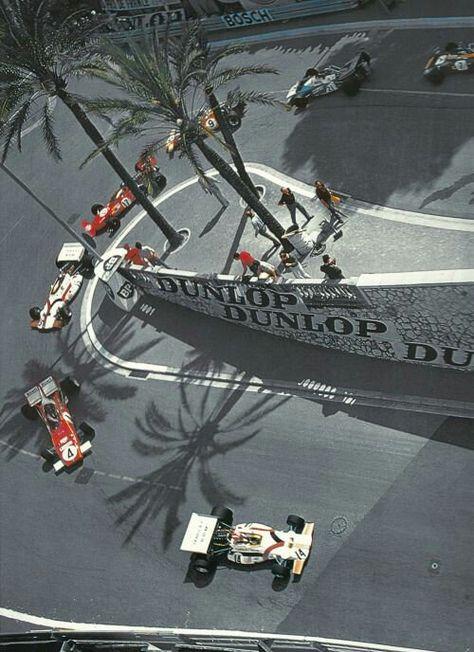

It’s May 1988 in Monte-Carlo and, as qualifying for tomorrow’s Monaco GP draws to a close, every last spectator is transfixed by Ayrton Senna, who’seking every last ounce of performance from his McLaren-Honda and, miraculously, continuing to go faster and faster…

It’s fair to say that the Brazilian always commands the bated attention of the crowds as he leaves the pits for a shot at pole position.

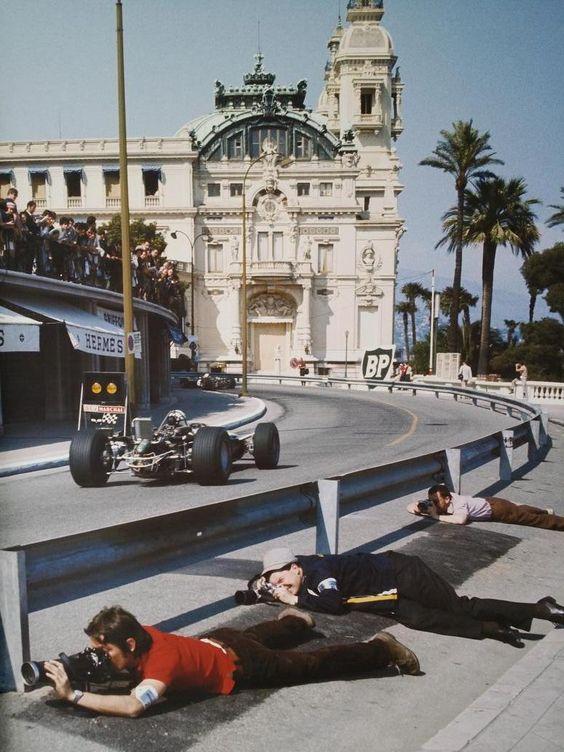

Mario Andretti, Monaco GP. By Philip Hunter.

But here, at Monaco, there isn’t a hand of cards, magnum of Champagne, or scantily dressed sunbather that can distract race-goers from witnessing Ayrton on the limit around the principality’s desperately narrow street.

Patrick Depailler (Tyrrell Ford 007) and Carlos Pace (Brabham Ford BT44b) at 1975 Monaco GP.

Monaco GP in 2018.

He is truly in a league of his own during the final qualifying session and just keeps lapping faster and faster, in spite of the fact he’s long surpassed his teammate Alain Prost — much to the dismay of team principal Ron Dennis. Senna’s throttle-stabbing, wheel-yanking, seat-of-the-pants driving style seems to suit this ultra-technical street circuit down to a tee. While his competitors have struggled to dip beneath 1:28 in today’s session, Senna has posted a 1:25.6, a 1:24.4, and, in emphatic style, a 1:23.998 — an incomprehensible 1.427 seconds quicker than his teammate in 2nd and 2.6 seconds quicker than Berger in 3rd. That’s bonkers!

Ayrton Senna 1988 Monaco GP.

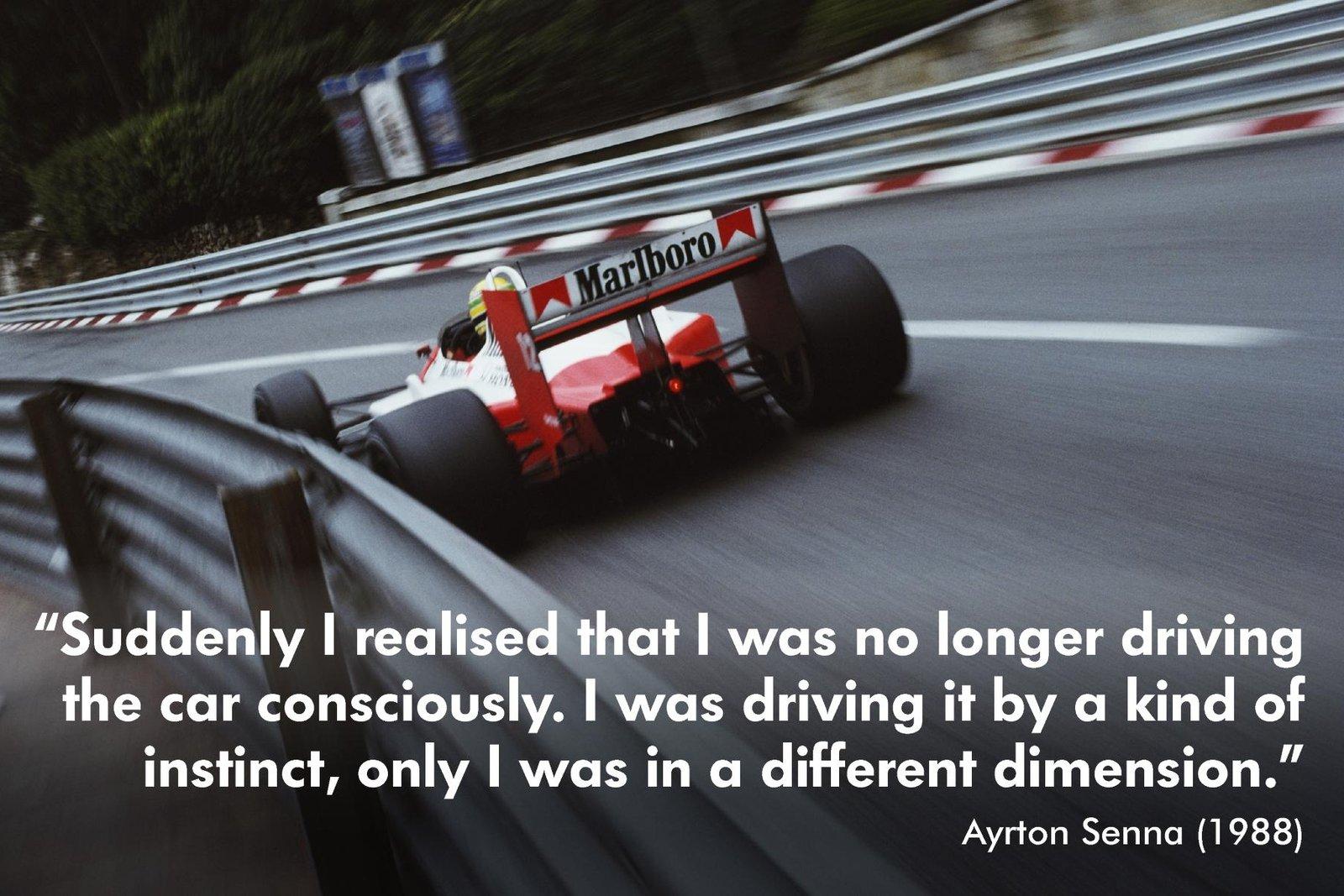

After the session, Ayrton will describe the pole-position lap as a sub-conscious experience — that he was “driving the car by a kind of instinct, only in a different dimension…well beyond my conscious understanding.” This will be held as one of, if not the greatest single laps in F1 history. It’s his otherworldly flair through the infamous swimming pool complex, his steely commitment into Sainte Devote, and the relentless pursuit of perfection that, this time, he almost certainly reached. “When I race against the clock and against other drivers this gives me a sense of expectancy, of giving my best and be the greatest, an energy that at certain times, when I’m driving, detachs myself completely from everything else. And that’s exactly what happened in Monte Carlo.”

By Getty Images.

Ayrton throws himself in qualifications with racing tyres, “so that I can do many laps.” A few minutes from the end of the qualifying session Senna ends his lap in front of everyone but decides to stay out and trying a very last lap to better himself. The result is amazing, an impeccable lap to which each driver aspires. Senna foisted a gigantic gap on Prost in the same car, 1″427 seconds; the Frenchman is speechless: “fantastic! It cannot be described in any other way! In these circumstances you take a risk, something that then later does not repeat.” Prost, annihilated, lost like he had never felt before during his whole great career. Alain Prost, one of the greatest of this sport, reduced to anybody, less than a sparring partner, by his teammate in the same car. Ayrton said: “sometimes I think I know some of the reasons why I do my job ….. Montecarlo ’88, qualifying session, Saturday afternoon: I was on pole position already, at first half a second, then a second and I went, I went, I went faster and faster. In a short time I was 2 seconds quicker than anyone else. It was like I was in a tunnel, not only in a tunnel under the Hotel, but the same track was a tunnel to me, and I was passing through it touching on the sides. I simply drove and kept on driving faster, faster and faster. I was way over the limit and I surely could cross it again. Suddenly something hit me, I woke up and I took my foot off the gas. My instant reaction was to give that up and limiting speed. I slowly got back to the pits getting a strong feeling to have reached my limits and the ones of the car as never before and that day I didn’t want to go out anymore, scared, knowing to be incredibly vulnerable. It rarely happens, but I have those experiences clearly aware and they keep me alive, as they’re important for self-esteem. Danger to be injured or to meet death is there, each driver lives eternally with that risk. That’s important to know what fear is, because it keeps you awake, it makes you watch out. That often makes your limits solids.”

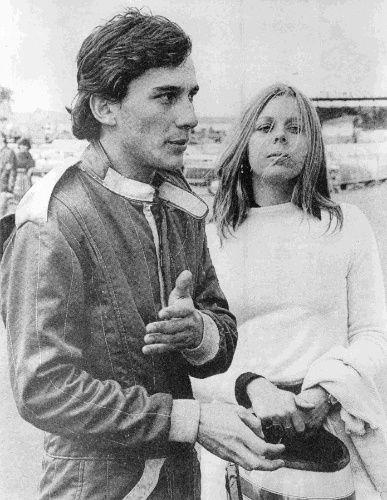

England 1981. Ayrton Senna with his first wife Lilian de Vasconcellos.

What happened that day was not followed live by many among the present passionate about Formula 1, but continues to live through memory. The memory of an event capable of penetrating in our souls and shake them up with basic phrases which, spoken in any language, with any intonation, give you goose bumps. Usually this particular anecdote is summed up in a couple of drab sentences of the biographies of Ayrton, as if you wanted to compress the immensity of what happened that day, probably for the absence of the right words to describe it. 1:23.998. 30 years ago Senna was magic: the physical therapist Leberer remembers: “he was in a trance. He got the feeling to be able to look at him from outside the cockpit.” They called it the fastest lap of all time. And Lewis Hamilton grew up watching on YouTube the video of his idol Ayrton Senna in Monaco. Josef Leberer, who used to live in symbiosis with the Brazilian, remembers that day like it’s today. “I went to check on his times and my jaw was on the ground. I knew straight that Ayrton had done something special and that maybe such a performance wouldn’t have seen again. On certain days he took any defence away from opponents, because he made them feel like he was invincible.” Prost was stunned: “I remember he had the ghost’s face, reported Neil Oatley, the McLaren engineer. “He couldn’t understand what or where that Senna’s lap came up.” Magic really did have something divine when driving. “Maybe it is,” Leberer continues. “Pole position to him was the pursuit of perfection. Think about what was to be driving a F1 in Monte Carlo, with the manual gearshift lever and the quite bad wobbles of cars at the time. It was a fight. And drivers came out exhausted.” In the race Senna was leading Prost by 49 seconds, when he crashed into Portier turn. Paradoxically that was the only dropping out, in between a series of six triumphs in the Principality from 1987 until 1993. “For two years I followed at McLaren both Ayrton and Alain. Until the relations between them deteriorated. I was between two fires. But I was able to establish a trust with the two. To have lived that era it’s a privilege.” And again talking about Ayrton: “he was someone who was thinking all the time. Sometimes I could feel this concern, through the vibrations of his body, and then I just told him to hold off on that and clear his head.” The Austrian physical therapist has decided to respect the confidentiality about the private and family life of the Brazilian. “He didn’t trust other people easily. I was the first one to see him when he woke up and the last one to leave him before bed, because the physio in his room was a rite which helped him to close the day blowing off steam. After all these years, we were in complete confidence. Therefore I’ll keep his secrets.”

A reporter tells in an article in the Italian newspaper “Repubblica”: “here’s what, talking with Stefano Stefanini – detective who has done the investigation of that accident, a very serious and prepared man, who in twenty years never gave any interview – I felt like it was the key video of this story or, at least, of the final chapter. This is the graphical revision on the computer of the last lap of Ayrton Senna, saw from the on-board camera. A spectacular job done by engineers of the Cineca centre of supercomputing in Bologna. Using as reference points the edge of the Williams cockpit and the yellow switch on the steering wheel we can clearly see how Senna’s wheel suddenly gave way. Because of the steering column that had been modified, it looks like, in order to install a bigger steering wheel (Senna loved it so) in the extremely tapered car designed byAdrian Newey. I was telling you about Stefanini. In the following, the article I wrote on that meeting.” “The whole world will never forget what happened that Sunday from twenty years ago at the Tamburello curve. He, instead, will never forget what happened the next day. There was a terrifying silence, at Imola. The public came home, the medevac helicopter got back to the hangar, reporters and photographers sieged their victims in Bologna and in San Paolo. That day, Stefano Stefanini, then 30 years old traffic police inspector from Bologna section, arrived at the Tamburello curve to do surveys, as with a routine accident. “Near here” he explains today and still gets excited “the Santerno river flows and in May the air fills with wool of the poplars. I entered the track from over there” he indicates. “On the ground there were tracks of Ayrton’s braking. And, where they finished, a coloured carpet of flowers, letters and various mementos which enthusiasts had left overnight started. It was four in the afternoon. You could hear flies flying. And I was making my way toward the wall moving these flowers.” It was the first investigative act. One of the most painful. “While I made that gesture, I measured with my defiler embarrassment the love that the whole world used to have for that man.” Love that Stefanini could have measured a thousand times again in the following months: “everywhere in Italy we found availability and cooperation. As soon as we said that it was for Senna’s investigation everyone was trying to be of use.” And it is perhaps also why today, after twenty years without ever giving an interview, he can boast of having conducted a perfect investigation, if there is a perfect investigation, and of having reconstructed with reasonable certainty the truth of the matter: Ayrton Senna went off the road and hit the wall of reinforced concrete at a speed of 198 kilometres per hour and at an angle of 22 degrees. The concussive force moved the wall 11 millimeters. The wheel is fixed to a F1 car through five little arms which end in a ring called uniball. In the impact one of these uniball exploded, and a deformed fragment, a blade about 6-7 centimeters long drilled the helmet, right where the visor starts. Like a bullet. Right temporal arch. The car continued, for inertia, its path for another 135 meters. The investigation of Stefanini and of the prosecutor of Bologna, Maurizio Passarini, “an exceptional man, to work with him to me it was lucky,” will prove that Senna had lost control of his Williams due to the breaking of the steering column, a part which had suffered “changes badly designed and badly built” for which was convicted of manslaughter Patrick Head (crime then time-barred), technical director of Williams. “It was a complex investigation. Because many of the inquiries needed to be conducted in England. There the criminal negligence doesn’t exist. They didn’t understand what we were doing. At every letters rogatory, it was like they’d tell us: “he raced in F1, he had considered it, it was an accident, why are you investigating?” A rationale that I accept, however Italian law forced us to know exactly what had happened.” That’s why there is a note of regret in Stefanini’s voice when considering the two grey areas still residual: Senna’s camera car, and the telemetrics disappeared. “The sentence makes no mention of red herrings, so there haven’t been any to me. However, when they have delivered us the images from the camera car, we saw that these stopped just two seconds before impact. They were on Katayama. Why? They said Senna was leading at that moment and there was nothing to see … As for the telemetrics, the same evening Williams asked to the federation to be able to download the data of the control units, to ensure the safety of the other driver, Damon Hill. It is logic, for heaven’s sake. But then data have been lost. If we would have had them it would have been much simpler.” F1, you know, assisted its way the investigation, with moderate enthusiasm: for his interrogation, Briatore invited the investigators (who refused) in Monte Carlo on his yacht, Ecclestone didn’t show up for the trial, the rest of the people said and didn’t say. The truth anyway, according to Stefanini, came out equally, in the end. “Also with the help that gave us Michele Alboreto. He was friends with Ayrton, he wanted to help. Today I can say that if we understood how did it go is thanks to him as well.” The problem, if anything, is to answer the question the British were asking, to figure out what was the point of investigating, seing all that. “The truth always serves, I like to think that if today in Formula 1 there are fewer accidents it’s also because of our investigation. But above all I love to think that Ayrton Senna would agree with me.”Among the things written or read on Senna, this one was very interesting for me. It’s the foreword by Felipe Massa to the book of Leo Turrini (it already sold a bunch of copies). “When Ayrton is gone, in Brazil we all felt orphan. I was a kid, I had just turned thirteen years of age when the news of the tragedy of Imola came. It was a collective mourning. We all cried, we hugged in the streets, shocked by a void we knew would never have been filled. We didn’t lose only a great champion of motoring. With Senna, took leave a wonderful symbol of our huge country. Ayrton has been, in the history of my nation, just as important as the legendary Pelè, who, with the ball between his feet, has celebrated the passion of a population for football, for the goal, for emotions daughters of a stadium. Yes, Ayrton wasn’t just a genius for driving. His sensitivity towards the problems of Brazil was something amazing. He really committed, without searching for free publicity, in favour of the most vulnerable population groups, starting with children. He was a real man and people understood this. About the driver, I can safely say that he was the best we’ve seen so far. He had an extraordinary natural aptitude for speed. I don’t like comparisons between protagonists from different ages, but I have never seen, in Formula One, a champion with his instinct over one lap, with his ability to put the mechanical mean on edge, without ever lose control of it. He was animated by an overpowering willingness of victory: in Brazil they loved him also for this, but I believe he was admired also in every other corner of the planet. In my small way, I’m proud to have driven for years the Ferrari, the car with which he would have certainly ended his career if the fate hadn’t decided differently. And it moves me the idea of being now behind the wheel of the Williams, the one that had been his last team. Ayrton Senna is in my heart. And would be there forever.”

Videos

Comments

Authorize to comment